Abstract

Background

Right ventricular (RV) maladaptation to elevated pulmonary afterload is the primary determinant of outcomes in pulmonary artery (PA) hypertension; however, the pathobiological mechanisms underlying RV decompensation remain poorly understood.

Methods

We performed global untargeted metabolomics on plasma from 55 patients who underwent gold‐standard RV‐PA coupling measurements using multibeat pressure volume loop assessment in a single‐center cohort and from 1027 patients with coupling surrogate measurements in a larger multicenter cohort, the PVDOMICS (Pulmonary Vascular Disease Phenomics) study. Age and sex‐adjusted linear regression was performed to identify associations between metabolites and coupling metrics. Additionally, we performed a metabolic flux analysis using gene expression data from RV tissue in an independent cohort of 32 patients. Partial least squares–discriminant analysis was used to identify metabolites and reactions characteristic of the decompensated RV.

Results

RV‐PA coupling was negatively associated with tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle intermediate levels. Specifically, plasma α‐ketoglutarate and fumarate were significantly associated with all coupling metrics in both cohorts. Metabolic flux analysis indicated that decompensated RVs exhibited aberrant TCA cycle activity, including reduced acetyl coenzyme A entry and increased lactate elimination, suggesting a shift from the TCA cycle toward glycolysis at the RV tissue level.

Conclusions

We identify an association between circulating TCA cycle intermediate levels and RV‐PA uncoupling in 2 independent cohorts, and dysregulated TCA cycle metabolism in decompensated PA hypertension RVs, suggesting that aberrant TCA cycle metabolism could represent a hallmark of RV maladaptation in PA hypertension. Further study of this pathway is warranted to develop novel biomarkers of RV function or RV‐targeted therapies.

Keywords: global untargeted metabolomics, right ventricular maladaptation, right ventricular–pulmonary artery coupling, tricarboxylic acid cycle

Subject Categories: Metabolism, Pulmonary Hypertension, Computational Biology

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- aKG

α‐ketoglutarate

- PAH

pulmonary artery hypertension

- PASP

pulmonary artery systolic pressure

- PDH

pyruvate dehydrogenase

- PH

pulmonary hypertension

- PLS‐DA

partial least squares discriminant analysis

- PV

pressure volume

- PVDOMICS

Pulmonary Vascular Disease Phenomics

- RHC

right heart catheterization

- TAPSE

tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion

- TCA

tricarboxylic acid

Research Perspective.

What Is New?

Leveraging global untargeted metabolomics and multibeat pressure volume loop assessment, this study identified that elevated plasma tricarboxylic acid cycle intermediates are associated with right ventricular–pulmonary artery uncoupling.

These findings, in combination with an analysis of inferred metabolic flux in the human right ventricle, advance our understanding of the pathobiologic changes that contribute to right ventricular maladaptation, highlighting tricarboxylic acid cycle dysregulation as a metabolic hallmark of disease.

What Questions Should Be Addressed Next?

Future studies should directly measure right ventricular myocardial metabolite concentrations and investigate the temporal relationship and mechanisms underlying tricarboxylic acid cycle dysregulation in right ventricular dysfunction.

Pulmonary artery hypertension (PAH) is a progressive and life‐limiting condition characterized by increased pulmonary vascular resistance ultimately leading to right ventricular (RV) failure. 1 , 2 While the right ventricle's ability to adapt to these elevated pulmonary artery (PA) pressures represents the primary determinant of PAH outcomes, the pathobiologic changes that contribute to RV maladaptation have yet to be fully elucidated. 2 , 3 As a result, there are no high‐fidelity biomarkers specific to RV dysfunction. Additionally, while there are multiple therapies that target the pulmonary vasculature, no existing therapies target the pathobiology responsible for RV maladaptation in PAH.

The degree to which the right ventricle can adapt, by increasing contractility to compensate for elevated afterload, is described by a metric called RV‐PA coupling. 4 , 5 , 6 Gold standard measurement of RV‐PA coupling, which is performed using multibeat pressure volume (PV) loop assessment, has been found to be an earlier and more sensitive predictor of clinical worsening than other markers of disease severity such as cardiac index, pulmonary vascular resistance, and RV ejection fraction. 5 , 7 , 8 , 9

While RV‐PA coupling offers a hemodynamic assessment of the right ventricle's adaptive response, there are no known serum markers of RV maladaptation. However, increasing evidence suggests that PAH is characterized by dysregulated metabolism in the pulmonary vasculature, lung parenchyma, and right ventricle. 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 While the myocardium relies on fatty acid oxidation as its primary energy source in healthy individuals, 16 , 17 , 18 alterations in cardiomyocyte fatty acid oxidation, intracellular lipid accumulation, and a shift from oxidative phosphorylation to glycolysis have all been described in the RV myocardium in PAH. 11 , 13 , 14 Our group has previously demonstrated that higher plasma levels of fatty acids and their metabolic intermediates are associated with worse RV ejection fraction and transplant‐free survival in PAH, 19 suggesting that circulating metabolites could serve as biomarkers reflective of the RV maladaptive response driving disease outcomes.

To identify metabolic signatures of RV maladaptation, we performed untargeted metabolomics in serum samples collected from patients undergoing gold‐standard measurements of RV‐PA coupling with multibeat RV PV loops. 5 , 7 We compared metabolites associated with direct measurement of RV‐PA coupling in our single‐center cohort with metabolites associated with noninvasive surrogates of RV‐PA coupling in the multicenter PVDOMICS (Pulmonary Vascular Disease Phenomics) cohort, who underwent comprehensive cardiopulmonary testing, including right heart catheterization (RHC), cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, and transthoracic echocardiogram. 20 To compare the circulating metabolites identified with metabolic shifts in the right ventricle, we then leveraged a metabolite flux analysis of gene expression data from RV bulk RNA sequencing in an independent cohort of patients with PAH and controls. We hypothesized that changes in gene expression in decompensated right ventricles would correspond with observed alterations in circulating metabolites associated with RV‐PA uncoupling.

Methods

The data corresponding to the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The studies including the discovery cohort and validation cohort were approved by the Johns Hopkins Medicine Institutional Review Board, and all subjects provided informed consent before study participation.

Study Design for Single‐Center Discovery Cohort

For our discovery cohort, participants were prospectively enrolled in a single‐center National Institutes of Health/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute–sponsored study (NCT04610788) at Johns Hopkins Hospital between 2013 and 2022 after referral for suspected PAH. After providing informed consent, subjects underwent RHC at rest and exercise, including contemporaneous RV PV loop assessment. The Valsalva maneuver was used to reduce preload and construct a family of PV loops as previously described, 4 , 5 allowing for measurement of the ratio of multibeat end‐systolic elastance to effective arterial elastance, the gold standard measurement for RV‐PA coupling. 4 , 7 , 8

Global untargeted metabolomics were performed using ultra‐performance liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry on patient plasma samples obtained from the mixed venous circulation during RHC under fasting conditions. Sample processing, preparation, quality control, and compound identification was performed by Metabolon, Inc. (Durham, NC). 21 All samples were maintained at −80 °C until processed. After initial processing, sample extract was divided into multiple fractions for 2 positive ion mode electrospray ionization and 2 negative ion mode electrospray ionization techniques. Quality control standards were selected for monitoring of instrument performance and to aid in chromatographic alignment. An ACQUITY ultra‐performance liquid chromatography (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA) and a Q‐Exactive high resolution/accurate mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) was operated with a heated electrospray ionization source and Orbitrap mass analyzer operated at 35 000 mass resolution. 22 , 23 Peaks were quantified using area under the curve, and postprocessing was performed to account for batch correction or interday variation. The minimum observed value for each metabolite was used for imputation of missing values.

Study Design for Multicenter Validation Cohort

Our multicenter validation cohort included patients from the PVDOMICS study group who underwent metabolomic profiling and comprehensive cardiopulmonary testing. PVDOMICS is a multicenter prospective cohort study with comprehensive hemodynamic, imaging, and clinical data from patients with various subtypes of pulmonary vascular disease, allowing for deep phenotyping and expert adjudication of diagnoses. The cohort also enrolled subjects without PH, either as healthy controls or disease comparators with similar comorbidities to corresponding patients with PH. Healthy controls were excluded to facilitate comparability with the Johns Hopkins cohort, which contained patients with suspected PAH. Procedures for patient enrollment, clinical testing, diagnostic adjudication, and data coordination have been previously published. 20 , 24 Because patients enrolled in PVDOMICS did not undergo PV loop assessment, RV‐PA coupling was estimated from RV stroke volume over end‐systolic volume and tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE) over PA systolic pressure (PASP), which have been previously validated as surrogates of RV‐PA coupling given their association with clinical outcomes in PAH and ability to describe RV contractile function in response to afterload. 25 , 26 , 27 Time‐to‐event analysis was performed starting from participant enrollment, which occurred between November 2016 and October 2019. Transplant‐free survival was determined by time to death or lung or heart transplantation. After enrollment, outcome ascertainment was performed at least annually by clinic visit, telephone calls, or national death registry search, and outcome data was administratively censored in April 2024.

Plasma metabolomic peripheral venous samples were drawn from patients during RHC in a fasting state, and samples were sent to the Data Coordinating Center biorepository for storage. Global untargeted metabolomics were performed with ultra‐performance liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry using Metabolon's HD4 panel, the same platform that was used for the discovery cohort, as previously described. 19 , 21

Acquisition of RV Bulk RNA Sequencing Data

Transcriptomic profiling data were obtained from a publicly available database (GEO Accession Number GSE198618) from which processed normalized gene count files were available for download. The transcriptomics data were obtained from human RV tissue in non‐PAH controls with healthy RV tissue (n=14), patients with PAH with compensated RV function (n=11) defined by tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE) ≥1.7 cm or cardiac index >2.2 L/min per m2, and end‐stage PAH patients with decompensated right ventricles (n=7). 28

Statistical Analysis

Metabolomics Data

For both the discovery and validation cohorts, postprocessed metabolite abundances were log‐transformed and auto‐scaled to a median of 0 and SD of 1 within each cohort. Unknown metabolites and xenobiotics such as drugs, foods, plants, and their metabolites were removed before analysis. Associations with metabolites and RV‐PA coupling were assessed using age‐ and sex‐adjusted linear regression models. Correction for multiple comparisons was made using a Benjamini–Hochberg correction to control the false discovery rate. 29 Cox proportional hazard modeling was performed to determine whether metabolite abundances were associated with risk of death or lung transplant in the validation cohort. We tested whether the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle metabolites individually predicted transplant‐free survival after adjustment for age and sex and performed backwards stepwise selection to generate a model including age, sex, and a sparse list of TCA cycle intermediates.

In addition to generating our main results, we performed 3 sensitivity analyses to test the robustness of our findings to varying conditions. To test whether associations with metabolites of interest were robust to confounding, we performed adjustment with multiple potential confounders including left ventricular function, renal function, hypoxemia defined by arterial blood gas saturation <90% or need for supplemental oxygen at rest, World Symposium on PH group, body mass index, PH medication use, cardiac medication use, diagnosis of diabetes, and diagnosis of hypertension. Metabolic associations initially detected in the validation cohort were reanalyzed using mixed venous samples (available for n=553 subjects in PVDOMICS) to allow for comparability of our findings between discovery and validation cohort, in which samples were collected from the mixed venous compartment. Finally, in addition to modeling coupling as a continuous variable, we modeled associations between TCA cycle metabolites and RV decompensation defined by cardiac index<2.2 L/min per m2 or TAPSE <1.7 cm, which were the criteria for RV decompensation in the transcriptomic data set.

Gene Expression Data

Normalized gene counts from bulk RNA sequencing were analyzed with a metabolic flux graph neural network algorithm, which was implemented to generate inferred metabolite balance and flux from the gene expression data. 30 After metabolic modeling of RV transcriptomic data, metabolite balance and flux output were appropriately transformed then analyzed with partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS‐DA) between decompensated, compensated, and healthy control right ventricles. 31 Variable importance in projection coefficients were generated for the metabolic features driving class separation between labeled clinical phenotypes. 32 The P value for permutation tests was calculated for class prediction accuracy and the Q2 statistic was calculated to assess predictive performance of PLS‐DA models. Statistical analysis was performed using the MetaboAnalyst package in R version 4.1.2 (R Core Team 2021) and Stata statistical software version 17 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). 33 Graph neural network analysis of bulk RNA sequencing data was performed with the single‐cell Flux Estimation Analysis package from Python version 3.12.3 (Python Software Foundation, Wilmington, DE). 30

Results

Patient Characteristics

Eighty‐seven subjects in the discovery cohort were eligible for potential inclusion, of which 55 who underwent metabolomic profiling and PV loop assessment were studied. Of 1112 eligible subjects in the validation cohort, 1027 patients with PH and comparators who underwent metabolomic profiling were studied. Demographics and baseline hemodynamics for these patients can be found in Table 1. The majority of patients in the discovery cohort had PAH, while the validation cohort had 40% patients with PAH and an increased proportion of comparators. Patients in both cohorts had predominantly World Health Organization Functional Class II and III symptoms. Both cohorts primarily feature patients who are White women in their fifth to seventh decade of life. Patients in the validation cohort had a median follow‐up time of 60 (interquartile range, 41–72) months.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics and Hemodynamics From the Discovery and Validation Cohorts

| Patient characteristics | Discovery cohort | Validation cohort |

|---|---|---|

| No. | 55 | 1027 |

| Age, y | 57 (45–68) | 61 (50–70) |

| Sex, female, n (%) | 46 (85.2) | 634 (61.9) |

| Race or ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| White | 39 (72.2) | 820 (80.1) |

| Black | 10 (18.5) | 123 (12.0) |

| Hispanic | 3 (5.6) | 88 (8.8) |

| Asian | 2 (3.7) | 24 (2.3) |

| Primary WSPH diagnosis, n (%) | ||

| Group 1 | 34 (61.8) | 339 (33.0) |

| Group 2 | 3 (5.5) | 126 (12.3) |

| Group 3 | 6 (10.9) | 162 (15.8) |

| Group 4 | 0 (0) | 55 (5.4) |

| Group 5 | 0 (0) | 29 (2.8) |

| Exercise | 2 (3.6) | 0 (0) |

| Unclassified PH | 2 (3.6) | 0 (0) |

| No PH | 8 (14.5) | 316 (30.8) |

| WHO‐FC, n (%) | ||

| I | 6 (10.9) | 61 (6.2) |

| II | 30 (54.5) | 354 (36.2) |

| III | 19 (34.5) | 514 (52.5) |

| IV | 0 (0) | 50 (5.1) |

| On PH medications, n (%) | ||

| On ERA | 17 (30.9) | 231 (22.6) |

| PDE5i | 20 (36.4) | 322 (31.6) |

| Prostaglandins | 0 (0) | 175 (17.2) |

| CCB | 14 (25.5) | 20 (2.0) |

| Distance, m | 404 (310–480) | 353 (256–436) |

| NT‐proBNP, pg/mL | 204 (110–526) | 238 (86–985) |

| RAP, mm Hg | 5 (3–8) | 7 (4–10) |

| RVSP, mm Hg | 43 (36–75) | 51 (36–72) |

| Mean PAP, mm Hg | 28 (23–40) | 32 (23–44) |

| PAWP mean, mm Hg | 10 (7–13) | 11 (8–16) |

| CO, L/min | 4.6 (3.9–5.5) | 4.9 (3.9–5.9) |

| PVR, WU | 4.2 (2.2–6.6) | 3.4 (2.0–6.3) |

| RVEF, % | 51 (41–57) | 45 (35–54) |

| E es/E a | 1.0 (0.6–1.6) | |

| SV/ESV | 0.82 (0.54–1.15) | |

| TAPSE/PASP, mm/mm Hg | 0.40 (0.24–0.55) | |

Continuous variables represented as median (interquartile range) and categorical variables as n (%). CCB indicates calcium channel blocker; CO, cardiac output; E es/E a, end‐systolic elastance/arterial elastance; ERA, endothelin receptor antagonist; mean NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide; PAP, pulmonary artery pressure; PAWP, pulmonary artery wedge pressure; PDE5i, phosphodiesterase‐5 inhibitor; PH, pulmonary hypertension; PVR, pulmonary vascular resistance; RAP, right atrial pressure; RVEF, right ventricular ejection fraction; RVSP, right ventricular systolic pressure; SV/ESV, stroke volume/end‐systolic volume; TAPSE/PASP, tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion/pulmonary artery systolic pressure; WHO‐FC, World Health Organization Functional Class; and WSPH, World Symposium on Pulmonary Hypertension.

Metabolite Associations With RV‐PA Coupling

After quality control, 1442 individual metabolites were identified in the discovery cohort. After removal of unknown compounds, partially characterized molecules, and xenobiotics, 890 features were analyzed. In linear regression, 69 metabolites were nominally associated (P<0.05) with RV‐PA coupling as measured by multibeat end‐systolic elastance over arterial elastance (Figure 1 and Table S1). Metabolites with the most significant associations with coupling included the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle intermediates α‐ketoglutarate (aKG) (P<0.001), succinate (P<0.01), and fumarate (P<0.01), all of which were negatively associated with end‐systolic elastance over arterial elastance (Table 2). Of these metabolites, aKG (q=0.09) met our predefined false discovery rate threshold with a q value <0.2.

Figure 1. Results from age‐ and sex‐ adjusted linear regression between metabolites and multibeat E es/E a in the discovery cohort.

A, β‐coefficients with 95% CI for metabolites with P value <0.05. B, Manhattan plot illustrating –log (P value) for metabolites separated by metabolic pathway. E es/E a indicates end‐systolic elastance/arterial elastance; and TCA, tricarboxylic acid.

Table 2.

Regression Results Between TCA Intermediates and Coupling Metrics (E es/E a, SV/ESV, and TAPSE/PASP)

| TCA cycle intermediates | E es/E a β (95% CI) | SV/ESV β (95% CI) | TAPSE/PASP β (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2‐methylcitrate/homocitrate | 0.08 (−0.22 to 0.38) | −0.09 (−0.18 to −0.01) | −0.11 (−0.18 to −0.03)* |

| Aconitate | −0.02 (−0.38 to 0.34) | −0.27 (−0.36 to −0.18)* | −0.25 (−0.33 to −0.18)* |

| α‐Ketoglutarate | −0.57 (−0.85 to −0.3)* | −0.25 (−0.33 to −0.17)* | −0.26 (−0.33 to −0.19)* |

| Citraconate/glutaconate | −0.04 (−0.33 to 0.24) | −0.01 (−0.1 to 0.07) | −0.02 (−0.09 to 0.05) |

| Citrate | −0.17 (−0.6 to 0.27) | −0.16 (−0.24 to −0.08)* | −0.18 (−0.25 to −0.11)* |

| Fumarate | −0.39 (−0.69 to −0.1)* | −0.32 (−0.41 to −0.24)* | −0.27 (−0.35 to −0.2)* |

| Isocitrate | 0.13 (−0.16 to 0.43) | – | – |

| Malate | −0.16 (−0.44 to 0.13) | −0.37 (−0.45 to −0.28)* | −0.27 (−0.34 to −0.2)* |

| Succinate | −0.41 (−0.71 to −0.11)* | −0.08 (−0.16 to 0) | −0.06 (−0.12 to 0.01) |

| Succinylcarnitine (C4‐DC) | −0.16 (−0.44 to 0.12) | −0.08 (−0.16 to 0) | −0.12 (−0.19 to −0.04)* |

All linear regression models are age and sex adjusted. E es/E a indicates end‐systolic elastance over arterial elastance; SV/ESV, stroke volume/end‐systolic volume; TAPSE/PASP, tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion/pulmonary artery systolic pressure; and TCA, tricarboxylic acid.

Significance by P<0.05 in the discovery cohort and q<0.05 in the validation cohort.

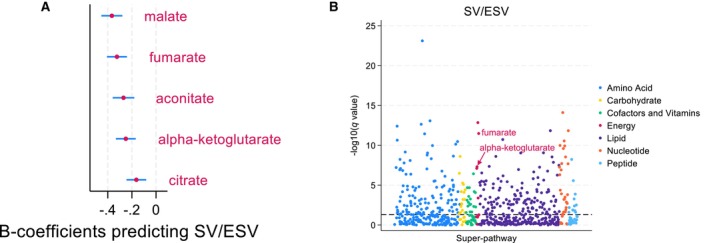

In the validation cohort, 974 individual metabolites were identified, of which 656 remained after filtering out unknowns, xenobiotics, and partially characterized molecules. We initially examined associations between RV‐PA coupling and TCA metabolites in our validation cohort because of the findings in our discovery cohort. We identified that malate (β‐coefficient, −0.37; P=1.4e‐13), fumarate (β‐coefficient, −0.32; P=3.2e‐12), aKG (β‐coefficient, −0.25; P=4.9e‐8), aconitate (β‐coefficient, −0.27; P=7.8e‐8), and citrate (β‐coefficient, −0.16; P=4.0e‐4) were all negatively associated with stroke volume/end‐systolic volume, the cardiac magnetic resonance imaging–derived surrogate of RV‐PA coupling (Table 2 and Figure 2). Fumarate (β‐coefficient, −0.27; P=5.4e‐12), aKG (β‐coefficient, −0.26; P=7.3 e‐12), malate (β‐coefficient, −0.27; P=3.1e‐11), aconitate (β‐coefficient, −0.25; P=2.8e‐9), citrate (β‐coefficient, −0.18; P=1.1e‐5), succinylcarnitine (β‐coefficient, −0.12; P=4.8e‐3), and methylcitrate (β‐coefficient, −0.11; P=1.0e‐2) were significantly associated with TAPSE/PASP, the echocardiogram‐derived surrogate of RV‐PA coupling (Table 2 and Figure 3). Distributions for log‐transformed TCA cycle metabolite abundances for coupled versus decoupled RV‐PA units can be found in Figures S1 and S2.

Figure 2. Results from age‐ and sex‐adjusted linear regression between metabolites and SV/ESV in the validation cohort.

A, β‐coefficients with 95% CI for TCA cycle metabolites with q value <0.05. B, Manhattan plot illustrating –log (q value) separated by metabolic pathway, with TCA cycle metabolites in red. SV/ESV indicates stroke volume/end‐systolic volume; and TCA, tricarboxylic acid.

Figure 3. Results from age‐ and sex‐adjusted linear regression between metabolites and TAPSE/PASP in validation cohort.

A, β‐coefficients with 95% CI for TCA cycle metabolites with q value <0.05. B, Manhattan plot illustrating –log (q value) separated by metabolic pathway, with TCA cycle metabolites in red. TAPSE/PASP indicates tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion/pulmonary artery systolic pressure; and TCA, tricarboxylic acid.

We then performed an unbiased assessment to more comprehensively assess associations with coupling surrogates, identifying 325 compounds that were significantly associated with stroke volume/end‐systolic volume (Table S2) and 358 compounds, which were associated with TAPSE/PASP (Table S3), based on a q value <0.05. Across cohorts, 15 metabolites were significantly associated with all 3 measures of RV‐PA coupling (Figure 4). These metabolites included the TCA cycle intermediates aKG and fumarate, as well as other metabolites previously reported to be associated with RV function such as arginine, arachidonic acid, and kynurenine pathway intermediates.

Figure 4. Venn diagram illustrating overlap in metabolites associated with E es/E a, SV/ESV, and TAPSE/PASP in linear regression.

Fifteen metabolites significantly associated with all 3 coupling metrics are listed. E es/E a indicates end‐systolic elastance/arterial elastance; SV/ESV, stroke volume/end‐systolic volume; and TAPSE/PASP, tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion/pulmonary artery systolic pressure.

To understand the specificity of these markers for RV‐PA coupling versus other hemodynamic metrics, we analyzed metabolic associations between TCA cycle metabolites and RHC‐derived measures of cardiac filling, load, and output. We found TCA cycle metabolites were most strongly associated with load (pulmonary vascular resistance) and RV‐PA coupling (Figure S3). We also assessed associations between TCA cycle metabolites and functional outcomes, analyzing World Health Organization Functional Class with multinomial logistic regression and 6‐minute walk distance with linear regression (Tables S4 and S5).

In time‐to‐event analysis, there were 343 participants who either died or were transplanted during follow‐up. In Cox regression, all tested TCA cycle metabolites other than succinylcarnitine and citrate were individually associated with transplant‐free survival (Figure S4). After backwards stepwise selection of features, a sparse model included aconitate with a hazard ratio (HR) of 1.31 (95% CI, 1.08–1.59; P<0.01), aKG with an HR of 1.17 (95% CI, 1.00–1.37; P=0.05), citraconate with an HR of 1.25 (95% CI, 1.13–1.38; P<0.001), citrate with an HR of 0.72 (95% CI, 0.62–0.85; P<0.001), and malate with an HR of 1.29 (95% CI, 1.08–1.55; P<0.01) (Table 3).

Table 3.

TCA Cycle Intermediates Predict Transplant‐Free Survival in Cox Proportional Hazard Model in the Validation Cohort

| Variables in Cox model | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.01 (1.00–1.02) | 0.051 |

| Sex | 0.64 (0.51–0.79) | <0.001 |

| Aconitate | 1.31 (1.08–1.59) | 0.007 |

| α‐Ketoglutarate | 1.17 (1.00–1.37) | 0.050 |

| Citraconate | 1.25 (1.13–1.38) | <0.001 |

| Citrate | 0.72 (0.62–0.85) | <0.001 |

| Malate | 1.29 (1.08–1.55) | 0.005 |

The model included age, sex, and a sparse list of TCA cycle intermediates obtained by backwards stepwise selection. TCA indicates tricarboxylic acid.

Sensitivity Analyses

When adjusting for potential confounding of the relationships between TCA cycle metabolites and RV‐PA coupling by differences in left ventricular function, renal function, oxygen saturation, and cardiovascular comorbidities, the relationship between succinylcarnitine and TAPSE/PASP was no longer significant with adjustment for left ventricular function and renal function. Otherwise, all associations between TCA cycle metabolites and coupling remained significant after adjustment (Figures S5 and S6).

TCA cycle metabolite associations using mixed venous samples were similar to peripheral venous samples, with significant associations between coupling surrogates and aconitate, aKG, malate, and fumarate, and succinylcarnitine (Figures S7 and S8). When applying the TAPSE and cardiac index–derived definition of RV decompensation used in the RV transcriptomics data set, TCA cycle intermediates associated with RV decompensation were similar to those associated with RV‐PA coupling and coupling surrogates in our primary analysis (Figures S9 and S10).

Metabolic Flux Analysis From RV Bulk RNA Sequencing Data

The single‐cell Flux Estimation Analysis computations produced inferred metabolite balance and flux data for 70 metabolites and 168 metabolic reactions for each RV sample. Class separation from PLS‐DA on the metabolite flux and balance data as well as model features that explain a significant proportion of the variance between predefined labels of RV function are shown in Figures 5 and 6. The most predictive features of metabolic flux demonstrate that decompensated RVs were characterized by increased lactate elimination and decreased acetyl coenzyme A entry into the TCA cycle. Additionally, decreased cell entry of propionyl coenzyme A and production of acetyl coenzyme A from β‐alanine, which represent inputs into the TCA cycle, were among the most important features. Top features of metabolite balance similarly implicate lactate, TCA cycle intermediates including citrate, oxaloacetate, and succinate, as well as arginine metabolism. Permutation testing yielded a P value <0.001 for both metabolite flux and balance, suggesting a low likelihood the models could achieve this degree of class separation with random class labels. Graphical overviews of permutation and performance testing can be found in Figures S11 and S12.

Figure 5. Results from PLS‐DA of inferred metabolic flux from RV transcriptomics (N=34).

A, Model discrimination of clinically defined RV functional states. Colored point clouds represent different RV functional states. B, VIP plot illustrating relative importance of each metabolic reaction contributing to class separation by component 1, with higher values reflecting greater contribution. Colored boxes to the right represent the relative metabolic flux of each reaction across the 3 RV functional states. PLS‐DA indicates partial least squares discriminant analysis; RV, right ventricle; and VIP, variable importance in projection.

Figure 6. Results from PLS‐DA of inferred metabolite balance from RV transcriptomics (N=34).

A, Model discrimination of clinically defined RV functional states. Colored point clouds represent different RV functional states. B, VIP plot illustrating relative importance of each metabolite contributing to class separation by component 1, with higher values reflecting greater contribution. Colored boxes to the right represent the relative balance of each metabolite across the 3 RV functional states. PLS‐DA indicates partial least squares discriminant analysis; RV, right ventricular; and VIP, variable importance in projection.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that plasma TCA cycle metabolite concentrations are associated with RV‐PA uncoupling, which was a consistent finding across multiple TCA cycle intermediates, diverse measurements of RV‐PV function, and in 2 highly phenotyped cohorts. Further, our bioinformatic analysis of RV RNA sequencing data suggests metabolic flux in the maladapted right ventricle is characterized by aberrant TCA cycle metabolism.

While increased circulating TCA cycle metabolite levels have been noted in patients with PAH compared with healthy controls, few studies have assessed the association between TCA cycle metabolites across markers of disease severity. 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 One study noted that TCA cycle intermediates, including malate and succinate, were associated with basic hemodynamic parameters; however, only 1 recent study has investigated relationships between circulating metabolites and RV‐specific metrics. 37 , 38 Although this study identified that TCA cycle metabolites were associated with RV dilation, there was no evaluation of associations between metabolites and RV function or RV‐PA coupling. Our findings demonstrate that, across the disease spectrum, progressive RV dysfunction is characterized by higher plasma TCA cycle intermediate concentrations. Other metabolites significantly associated with RV‐PA coupling metrics in our 3 linear regression models have previously been described, including metabolites involved in arginine, kynurenine, and arachidonic acid metabolism. 39 , 40 Additionally, N2,N2‐dimethylguanosine has been noted to be elevated in patients with PAH compared with controls, although we are unaware of direct associations with RV‐PV function. 41

While previous studies have examined RV lipid abundance in PAH, we are unaware of any human studies that have directly assessed metabolic derangements broadly within the PAH RV. 11 To our knowledge, our computational approach represents the first analysis of inferred RV metabolism in PAH. Our findings suggest that aberrant TCA cycle flux and metabolite balance exist at the RV tissue level in decompensated PAH. It is provocative to speculate that circulating TCA cycle metabolite concentrations are reflective of TCA cycle dysfunction in the right ventricle; however, our study does not directly address this, and circulating metabolic shifts could simply reflect changes in other tissues due to systemic complications of poor RV function. Notably, our transcriptional results are consistent with prior human RV gene expression data identifying reduced expression of IDH1 and SUCLA2, genes encoding TCA cycle enzymes, in PAH RVs compared with controls. 42 Additionally, prior metabolite profiling in failing rat right ventricles has implicated aberrant TCA cycle metabolism, identifying decreased propagation of downstream intermediates from citrate. 43

Further suggesting a metabolic shift away from the TCA cycle, lactate elimination was a highly predictive feature of RV decompensation in our analysis. Increased lactate elimination was inferred from upregulation of genes encoding monocarboxylate transporters SLC16A1, SLC16A3, and SLC16A4. In addition to facilitating lactate transport across the cardiomyocyte cell membrane, SLC16A1 plays a significant role in allowing cardiomyocyte entry of ketone bodies and has been found to be upregulated in myocardial cells in preclinical models of ischemic heart failure with reduced ejection fraction in the setting of increased reliance on ketone bodies for energy consumption. 44 , 45 Taken all together, this suggests our metabolic flux analysis may indicate increased ketone body transport in combination with increased lactate elimination.

The TCA cycle is a central pathway of aerobic respiration housed within the mitochondria, generating ATP as well as electron donors, which then allow for further energy production in the electron transport chain. The primary input for the TCA cycle is acetyl coenzyme A, which can be produced from lipid, carbohydrate, and protein catabolism as the result of fatty acid β‐oxidation, pyruvate decarboxylation after generation by glycolysis, and amino acid oxidation, respectively. 46 However, other entry points into the TCA cycle include glutaminolysis, which leads to formation of aKG, propionyl coenzyme A generation of succinate, and metabolism of other amino acids leading to fumarate, malate, or oxaloacetate formation. To maintain a constant balance of TCA cycle intermediates, the reactions involving substrate entry into the TCA cycle, collectively called anaplerosis, must balance the cataplerotic reactions leading to removal of intermediates, which can alternatively be used for biosynthesis or cellular signaling. 46

Our results for inferred metabolic flux in RV cardiomyocytes suggests reduced anaplerosis, with downregulated production of citrate from acetyl coenzyme A, downregulated propionyl coenzyme A metabolism, as well as elevated lactate elimination, collectively suggesting a shift to a glycolytic state. While the right ventricle is primarily dependent on β‐oxidation in healthy patients, the right ventricle in patients with PAH experiences reduced β‐oxidation coupled with increased reliance on glycolysis for energy production. 10 , 16 , 17 These changes are additionally associated with inhibition of pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) by PDH kinase, leading to reduced acetyl coenzyme A formation and TCA cycle metabolism. In rodent models, PDH kinase–mediated glycolytic shift is associated with decreased RV contractile function, which improves with reversal of PDH activity, suggesting this metabolic shift may be directly tied to maladaptive changes leading to RV dysfunction. 10 , 47 In 1 study, administration of dichloroacetate, which inhibits PDH kinase, was shown to improve hemodynamics and functional capacity in patients with idiopathic PAH already on pulmonary vasodilators. 48 While treatment effects were heterogeneous and more pronounced in genetically susceptible individuals, the findings suggest targeting metabolic pathways may improve PAH outcomes beyond traditional vasodilator therapy. Our metabolic flux analysis is notable for both reduced TCA activity and elevated myocardial lactate formation, which would be consistent with a PDH kinase–mediated metabolic shift. This suggests that dichloroacetate could be a plausible candidate for reversing metabolic derangements associated with RV maladaptation, and consideration could be given to translational studies testing its effects on RV cells and tissues in preclinical models.

Our study has several limitations. Because the patients in our single‐center cohort all underwent gold‐standard RV‐PA coupling measurements with PV loop assessment, this discovery cohort was modest in size. To test our findings in a larger cohort, we used coupling surrogates, rather than gold‐standard measurements, in validation. However, our consistent findings across coupling surrogates demonstrate the robustness of these findings as well as the validity of using accessible surrogates of RV‐PA coupling in future studies performing metabolic profiling of RV‐PV function. Our analysis of RV metabolism is inferred from public gene expression data rather than directly measured. Subjects who contributed RV tissue were not as comprehensively phenotyped as subjects who provided serum for direct metabolic measurements. However, our sensitivity analysis demonstrated that measured metabolic associations with TCA cycle intermediates remained significant when applying the definition of RV decompensation used in our inferred metabolomic analysis, supporting comparability across these methodologies. It is also important to consider that circulating TCA metabolites may reflect the activity of tissue sources other than the myocardium, as global TCA cycle regulation varies by tissue, with prior studies observing increased expression of TCA cycle enzymes in PAH lungs. 34 , 35 While our inferred RV metabolomic analysis highlights various implicated reactions, we did not explore the direct mechanisms underlying aberrant TCA cycle metabolism in the current study. Additionally, this study did not determine the temporal association between TCA cycle dysregulation and RV dysfunction. Understanding whether TCA cycle dysregulation is a cause or consequence of RV dysfunction will be an important future step in research.

Additionally, our study has multiple strengths, and to our knowledge, this is the first study to examine circulating global untargeted metabolomic associations with gold‐standard measurements of RV‐PA coupling. While other studies have demonstrated the presence of TCA cycle dysregulation in patients with PAH compared with controls, 34 , 35 we have yet to find a human study associating metabolite concentration with meticulously measured RV function and adaptation metrics. Moreover, validation in a multicenter cohort with granular phenotyping as well as incorporation of tissue specific analysis lends further strength to our findings.

Conclusions

Further understanding of the metabolic derangements associated with RV maladaptation is critical, as RV function is the primary determinant of outcomes in PAH. To our knowledge, this is the first study analyzing RV‐specific metabolic derangements in PH across plasma and tissue compartments, paving the way for a deeper understanding of the metabolic pathways underpinning RV maladaptation. We identify that plasma TCA cycle metabolite concentrations are inversely associated with measurements of RV‐PA coupling function in 2 highly phenotyped cohorts. Additionally, metabolic flux analysis within the right ventricle suggests that TCA cycle dysregulation is a metabolic hallmark of the decompensated right ventricle. Future study is needed to directly measure RV myocardial metabolite concentrations across the spectrum of RV maladaptation. Results could lead to discovery of RV‐specific biomarkers and identification of RV‐directed therapeutic targets.

Appendix

PVDOMICS Study Group Authors

Chair, Steering Committee: Tufts Medical Center: Hill N; NHLBI: Xiao L, Fessel J, Fu Y‐P, Postow L, Schmetter B, Sutliff R, Tian X; Pulmonary Hypertension Association: Gray M, Joseloff E. Wong B; Clinical Centers—Brigham and Women's Hospital: Leopold J (principal investigator), Waxman A (PI), Lawler L, Maron B, Systrom D; Columbia University: Rosenzweig EB (principal investigator), Brady D, Chung W, Grunig G, Haythe J, Krishnan U, Payne D; Weill Cornell Medicine: Horn E (principal investigator), Bergman G, Bastert K, Devereux R, Karas M, Kim J, Krishnan U, Lohman J, Racanelli A, Ricketts M, Sobol I, Singh H, Weinsaft J; Johns Hopkins University: Hassoun P (principal investigator), Mathai S (principal investigator), Balasubramanian A, Carey K, Damico R, Enobun B, Gao L, Halushka M, Hsu S, Kass D, Kolb T, Lin T, Mukherjee M, Roth J, Sanni Y, Simpson C, Weiss R, Zimmerman S; Mayo Clinic: Frantz R (principal investigator), Behfar A, Borlaug B, Du Brock H, Durst L, Head D, Foley T, Gochanour B, Halbach H, Kane G, Krowka M, Menon D, Park G, Redfield M, Rohwer K, Sands T, Scott C, Terzic A, Williamson E; The University of Arizona: Rischard F (principal investigator), Garcia J (principal investigator), Vanderpool R, Yuan J, Lim C, Abidov A, Desai A, Erickson H, Hansen L; Vanderbilt University: Hemnes A (principal investigator), Newman J (principal investigator), Brittain E, Cunningham J, Pugh M, Robbins I; Data Coordinating Center and Cores—Cleveland Clinic: Beck G (principal investigator), Erzurum S (principal investigator), Aldred M, Asosingh K, Aylor J, Barnard J, Beck B, Borowski A, Collart C, Cheng F, Comhair S, Di Filippo F, Drinko J, Farha S, Finet J, Flinn A, Geraci M, Hu B, Jaber W, Jacob M, Jellis C, Kanta A, Kwon D, Larive B, Lempel J, Li M, Martin M, MacKrell J, McCarthy K, Mehra R, Neumann D, Nawabit R, Odabashian J, Olman M, Park M, Radeva M, Ramos J, Renapurkar R, Sharp J, Sherer S, Tang WHW, Thomas J, Wadih K, Wells S, Wiggins K, Wilcox J, Willard B, Yu S; Observational Study Monitoring Board: Rounds S (chair), Benza R, Bull T, Cadigan J, Fang J, Gomberg‐Maitland M (ended September 2022).

Sources of Funding

This study was supported by the following National Institutes of Health grants: K23HL153781 (C.E.S.), F32HL176077 (D.T.R.), K23HL146889 (S.H.), R01HL114910 (P.M.H.), U01HL125175‐03S1 (P.M.H., S.C.M.).

Disclosures

Dr Tedford is Deputy Editor for the Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation. He reports general disclosures to include consulting relationships with and receiving honorarium from Abbott, Acorai, Adona, Aria CV Inc., Acceleron/Merck, Alleviant, Boston Scientific, Cytokinetics, Edwards LifeSciences, Gradient, Medtronic, Morphic Therapeutics, Restore Medical, Tempus AI, and United Therapeutics. Dr Tedford serves on the steering committee for Abbott, Edwards, Endotronix, and Merck as well as a research advisory board for Abiomed. He also does hemodynamic core lab work for Merck. Dr Hassoun serves on an advisory steering committee for Merck and the scientific advisory board for Aria CV. The remaining authors have no disclosures to report.

Supporting information

Tables S1–S5

Figures S1–S12

This manuscript was sent to June‐Wha Rhee, MD, Associate Editor, for review by expert referees, editorial decision, and final disposition.

Supplemental Material is available at https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/suppl/10.1161/JAHA.124.041127

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 11 .

Contributor Information

Catherine E. Simpson, Email: catherine.simpson@jhmi.edu.

the PVDOMICS Study Group:

N Hill, L Xiao, J Fessel, Y‐P Fu, L Postow, B Schmetter, R Sutliff, X Tian, M Gray, E. Joseloff, B Wong, J Leopold, A Waxman, L Lawler, B Maron, D Systrom, D Brady, W Chung, G Grunig, J Haythe, U Krishnan, D Payne, E Horn, G Bergman, K Bastert, R Devereux, M Karas, J Kim, U Krishnan, J Lohman, A Racanelli, M Ricketts, I Sobol, H Singh, J Weinsaft, P Hassoun, S Mathai, A Balasubramanian, K Carey, R Damico, B Enobun, L Gao, M Halushka, S Hsu, D Kass, T Kolb, T Lin, M Mukherjee, J Roth, Y Sanni, C Simpson, R Weiss, S Zimmerman, R Frantz, A Behfar, B Borlaug, H Du Brock, L Durst, D Head, T Foley, B Gochanour, H Halbach, G Kane, M Krowka, D Menon, G Park, M Redfield, K Rohwer, T Sands, C Scott, A Terzic, E Williamson, F Rischard, J Garcia, R Vanderpool, J Yuan, C Lim, A Abidov, A Desai, H Erickson, L Hansen, A Hemnes, J Newman, E Brittain, J Cunningham, M Pugh, I Robbins, G Beck, S Erzurum, M Aldred, K Asosingh, J Aylor, J Barnard, B Beck, A Borowski, C Collart, F Cheng, S Comhair, F Di Filippo, J Drinko, S Farha, J Finet, A Flinn, M Geraci, B Hu, W Jaber, M Jacob, C Jellis, A Kanta, D Kwon, B Larive, J Lempel, M Li, M Martin, J MacKrell, K McCarthy, R Mehra, D Neumann, R Nawabit, J Odabashian, M Olman, M Park, M Radeva, J Ramos, R Renapurkar, J Sharp, S Sherer, Tang WHW, J Thomas, K Wadih, S Wells, K Wiggins, J Wilcox, B Willard, S Yu, S Rounds, R Benza, T Bull, J Cadigan, J Fang, and M Gomberg‐Maitland

References

- 1. Hassoun PM. Pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2361–2376. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra2000348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Houston BA, Brittain EL, Tedford RJ. Right ventricular failure. N Engl J Med. 2023;388:1111–1125. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra2207410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Vonk Noordegraaf A, Chin KM, Haddad F, Hassoun PM, Hemnes AR, Hopkins SR, Kawut SM, Langleben D, Lumens J, Naeije R. Pathophysiology of the right ventricle and of the pulmonary circulation in pulmonary hypertension: an update. Eur Respir J. 2019;53. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01900-2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brener MI, Masoumi A, Ng VG, Tello K, Bastos MB, Cornwell WK, Hsu S, Tedford RJ, Lurz P, Rommel K‐P, et al. Invasive right ventricular pressure‐volume analysis: basic principles, clinical applications, and practical recommendations. Circ Heart Fail. 2022;15. doi: 10.1161/circheartfailure.121.009101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tedford RJ, Mudd JO, Girgis RE, Mathai SC, Zaiman AL, Housten‐Harris T, Boyce D, Kelemen BW, Bacher AC, Shah AA, et al. Right ventricular dysfunction in systemic sclerosis‐associated pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6:953–963. doi: 10.1161/circheartfailure.112.000008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hsu S. Coupling right ventricular‐pulmonary arterial research to the pulmonary hypertension patient bedside. Circ Heart Fail. 2019;12:e005715. doi: 10.1161/circheartfailure.118.005715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hsu S, Simpson CE, Houston BA, Wand A, Sato T, Kolb TM, Mathai SC, Kass DA, Hassoun PM, Damico RL, et al. Multi‐beat right ventricular‐arterial coupling predicts clinical worsening in pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9:e016031. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.016031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Richter MJ, Peters D, Ghofrani HA, Naeije R, Roller F, Sommer N, Gall H, Grimminger F, Seeger W, Tello K. Evaluation and prognostic relevance of right ventricular‐arterial coupling in pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201:116–119. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201906-1195LE [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tello K, Dalmer A, Axmann J, Vanderpool R, Ghofrani HA, Naeije R, Roller F, Seeger W, Sommer N, Wilhelm J, et al. Reserve of right ventricular‐arterial coupling in the setting of chronic overload. Circ Heart Fail. 2019;12. doi: 10.1161/circheartfailure.118.005512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Archer SL, Fang YH, Ryan JJ, Piao L. Metabolism and bioenergetics in the right ventricle and pulmonary vasculature in pulmonary hypertension. Pulmonary Circ. 2013;3:144–152. doi: 10.4103/2045-8932.109960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Brittain EL, Talati M, Fessel JP, Zhu H, Penner N, Calcutt MW, West JD, Funke M, Lewis GD, Gerszten RE, et al. Fatty acid metabolic defects and right ventricular lipotoxicity in human pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circulation. 2016;133:1936–1944. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.115.019351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fessel JP, Hamid R, Wittmann BM, Robinson LJ, Blackwell T, Tada Y, Tanabe N, Tatsumi K, Hemnes AR, West JD. Metabolomic analysis of bone morphogenetic protein receptor type 2 mutations in human pulmonary endothelium reveals widespread metabolic reprogramming. Pulmonary Circ. 2012;2:201–213. doi: 10.4103/2045-8932.97606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hemnes AR, Luther JM, Rhodes CJ, Burgess JP, Carlson J, Fan R, Fessel JP, Fortune N, Gerszten RE, Halliday SJ, et al. Human PAH is characterized by a pattern of lipid‐related insulin resistance. JCI . Insight. 2019;4. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.123611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Xu W, Janocha AJ, Erzurum SC. Metabolism in pulmonary hypertension. Annu Rev Physiol. 2021;83:551–576. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-031620-123956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chan SY, Rubin LJ. Metabolic dysfunction in pulmonary hypertension: from basic science to clinical practice. Eur Respir Rev. 2017;26:170094. doi: 10.1183/16000617.0094-2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Stanley W. Regulation of myocardial carbohydrate metabolism under normal and ischaemic conditions potential for pharmacological interventions. Cardiovasc Res. 1997;33:243–257. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(96)00245-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Oikawa M, Kagaya Y, Otani H, Sakuma M, Demachi J, Suzuki J, Takahashi T, Nawata J, Ido T, Watanabe J, et al. Increased [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose accumulation in right ventricular free wall in patients with pulmonary hypertension and the effect of epoprostenol. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:1849–1855. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.02.065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Agrawal V, Hemnes AR, Shelburne NJ, Fortune N, Fuentes JL, Colvin D, Calcutt MW, Talati M, Poovey E, West JD, et al. L‐carnitine therapy improves right heart dysfunction through Cpt1‐dependent fatty acid oxidation. Pulm Circ. 2022;12:e12107. doi: 10.1002/pul2.12107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Simpson CE, Hemnes AR, Griffiths M, Grunig G, Tang WHW, Garcia JGN, Barnard J, Comhair SA, Damico RL, Mathai SC, et al. Metabolomic differences in connective tissue disease‐associated versus idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension in the PVDOMICS cohort. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2023;75:2240–2251. doi: 10.1002/art.42632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hemnes AR, Beck GJ, Newman JH, Abidov A, Aldred MA, Barnard J, Berman Rosenzweig E, Borlaug BA, Chung WK, Comhair SAA, et al. PVDOMICS: a multi‐center study to improve understanding of pulmonary vascular disease through Phenomics. Circ Res. 2017;121:1136–1139. doi: 10.1161/circresaha.117.311737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Heresi GA, Mey JT, Bartholomew JR, Haddadin IS, Tonelli AR, Dweik RA, Kirwan JP, Kalhan SC. Plasma metabolomic profile in chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Pulmonary Circ. 2020;10:1–11. doi: 10.1177/2045894019890553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Evans AM, Bridgewater BR, Liu Q, Mitchell MW, Robinson RJ, Dai H, Stewart SJ, DeHaven CD, Miller LA. High resolution mass spectrometry improves data quantity and quality as compared to unit mass resolution mass spectrometry in high‐throughput profiling metabolomics. Metabolomics. 2014;4. doi: 10.4172/2153-0769.1000132 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ford L, Kennedy AD, Goodman KD, Pappan KL, Evans AM, Miller LAD, Wulff JE, Wiggs BR, Lennon JJ, Elsea S, et al. Precision of a clinical metabolomics profiling platform for use in the identification of inborn errors of metabolism. J Appl Lab Med. 2020;5:342–356. doi: 10.1093/jalm/jfz026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tang WHW, Wilcox JD, Jacob MS, Rosenzweig EB, Borlaug BA, Frantz RP, Hassoun PM, Hemnes AR, Hill NS, Horn EM, et al. Comprehensive diagnostic evaluation of cardiovascular physiology in patients with pulmonary vascular disease. Circ Heart Fail. 2020;13. doi: 10.1161/circheartfailure.119.006363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Vanderpool RR, Pinsky MR, Naeije R, Deible C, Kosaraju V, Bunner C, Mathier MA, Lacomis J, Champion HC, Simon MA. RV‐pulmonary arterial coupling predicts outcome in patients referred for pulmonary hypertension. Heart. 2015;101:37–43. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2014-306142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Brewis MJ, Bellofiore A, Vanderpool RR, Chesler NC, Johnson MK, Naeije R, Peacock AJ. Imaging right ventricular function to predict outcome in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Int J Cardiol. 2016;218:206–211. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.05.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tello K, Axmann J, Ghofrani HA, Naeije R, Narcin N, Rieth A, Seeger W, Gall H, Richter MJ. Relevance of the TAPSE/PASP ratio in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Int J Cardiol. 2018;266:229–235. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.01.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Boucherat O, Yokokawa T, Krishna V, Kalyana‐Sundaram S, Martineau S, Breuils‐Bonnet S, Azhar N, Bonilla F, Gutstein D, Potus F, et al. Identification of LTBP‐2 as a plasma biomarker for right ventricular dysfunction in human pulmonary arterial hypertension. Nat Cardiovasc Res. 2022;1:1–13. doi: 10.1038/s44161-022-00113-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J Roy Stat Soc: Series B (Methodological). 1995;57:289–300. doi: 10.1111/j.2517-6161.1995.tb02031.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Alghamdi N, Chang W, Dang P, Lu X, Wan C, Gampala S, Huang Z, Wang J, Ma Q, Zang Y, et al. A graph neural network model to estimate cell‐wise metabolic flux using single‐cell RNA‐seq data. Genome Res. 2021;31:1867–1884. doi: 10.1101/gr.271205.120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Barker M, Rayens W. Partial least squares for discrimination. J Chemom. 2003;17:166–173. doi: 10.1002/cem.785 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wold S, Sjöström M, Eriksson L. Partial Least Squares Projections to Latent Structures (PLS) in Chemistry. John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Xia J, Psychogios N, Young N, Wishart DS. MetaboAnalyst: a web server for metabolomic data analysis and interpretation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:W652–W660. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zhao Y, Peng J, Lu C, Hsin M, Mura M, Wu L, Chu L, Zamel R, Machuca T, Waddell T, et al. Metabolomic heterogeneity of pulmonary arterial hypertension. PLoS One. 2014;9:e88727. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Xu W, Comhair SAA, Chen R, Hu B, Hou Y, Zhou Y, Mavrakis LA, Janocha AJ, Li L, Zhang D, et al. Integrative proteomics and phosphoproteomics in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Sci Rep. 2019;9. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-55053-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bulló M, Papandreou C, García‐Gavilán J, Ruiz‐Canela M, Li J, Guasch‐Ferré M, Toledo E, Clish C, Corella D, Estruch R, et al. Tricarboxylic acid cycle related‐metabolites and risk of atrial fibrillation and heart failure. Metabolism. 2021;125:154915. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2021.154915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pi H, Xia L, Ralph DD, Rayner SG, Shojaie A, Leary PJ, Gharib SA. Metabolomic signatures associated with pulmonary arterial hypertension outcomes. Circ Res. 2023;132:254–266. doi: 10.1161/circresaha.122.321923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lewis GD, Ngo D, Hemnes AR, Farrell L, Domos C, Pappagianopoulos PP, Dhakal BP, Souza A, Shi X, Pugh ME, et al. Metabolic profiling of right ventricular‐pulmonary vascular function reveals circulating biomarkers of pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67:174–189. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.10.072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Simpson CE, Coursen J, Hsu S, Gough EK, Harlan R, Roux A, Aja S, Graham D, Kauffman M, Suresh K, et al. Metabolic profiling of in vivo right ventricular function and exercise performance in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2023;324:L836–L848. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00003.2023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Coursen JC, Tuhy T, Naranjo M, Woods A, Hummers LK, Shah AA, Suresh K, Visovatti SH, Mathai SC, Hassoun PM, et al. Aberrant long‐chain fatty acid metabolism associated with evolving systemic sclerosis‐associated pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2024;327:L54–l64. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00057.2024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rhodes CJ, Ghataorhe P, Wharton J, Rue‐Albrecht KC, Hadinnapola C, Watson G, Bleda M, Haimel M, Coghlan G, Corris PA, et al. Plasma metabolomics implicates modified transfer RNAs and altered bioenergetics in the outcomes of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circulation. 2017;135:460–475. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.116.024602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hemnes AR, Brittain EL, Trammell AW, Fessel JP, Austin ED, Penner N, Maynard KB, Gleaves L, Talati M, Absi T, et al. Evidence for right ventricular lipotoxicity in heritable pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189:325–334. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201306-1086oc [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hemnes A, Fortune N, Simon K, Trenary IA, Shay S, Austin E, Young JD, Britain E, West J, Talati M. A multimodal approach identifies lactate as a central feature of right ventricular failure that is detectable in human plasma. Front Med (Lausanne). 2024;11:1387195. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2024.1387195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lopaschuk GD, Karwi QG, Tian R, Wende AR, Abel ED. Cardiac energy metabolism in heart failure. Circ Res. 2021;128:1487–1513. doi: 10.1161/circresaha.121.318241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Aubert G, Martin OJ, Horton JL, Lai L, Vega RB, Leone TC, Koves T, Gardell SJ, Krüger M, Hoppel CL, et al. The failing heart relies on ketone bodies as a fuel. Circulation. 2016;133:698–705. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.115.017355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Owen OE, Kalhan SC, Hanson RW. The key role of Anaplerosis and cataplerosis for citric acid cycle function. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:30409–30412. doi: 10.1074/jbc.r200006200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ryan JJ, Archer SL. The right ventricle in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circ Res. 2014;115:176–188. doi: 10.1161/circresaha.113.301129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Michelakis ED, Gurtu V, Webster L, Barnes G, Watson G, Howard L, Cupitt J, Paterson I, Thompson RB, Chow K, et al. Inhibition of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase improves pulmonary arterial hypertension in genetically susceptible patients. Sci Transl Med. 2017;9:eaao4583. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aao4583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Tables S1–S5

Figures S1–S12