Abstract

Zinc is a nontoxic and readily available metal whose complexes have been extensively studied as catalysts for the ring‐opening polymerization of lactide to poly(lactic acid). When employed in polymerization of racemic lactide, zinc‐based catalysts are typically found to be nonstereoselective and the desired isoselective catalysts are particularly scarce. Herein, a new family of sequential pyridine‐imine/amine‐phenolate tetradentate‐monoanionic {ONNN}‐type ligands which leads to well‐defined {ONNN}Zn—Et complexes is studied. The relative location of the internal imine and amine donors affects their wrapping tendencies around the zinc. Upon activation with benzyl alcohol, active catalysts for the ring‐opening polymerization of racemic lactide are formed. The activities and stereoselectivities of the catalysts are strongly affected by the ligand substitution pattern and in particular by the relative location of the imine and amine donors. Thus, pyridine‐amine‐imine‐phenolate zinc complexes are isoselective and polymerize racemic lactide to give isotactic multiblock poly(lactic acid), whereas the isomeric pyridine‐imine‐amine‐phenolate zinc complex is essentially nonstereoselective. A rare combination of very high activity and very high isoselectivity reaching a P m = 0.90 at room temperature is achieved with selected members of this catalyst family.

Keywords: isoselective catalysis, poly(caprolactone), poly(lactic acid), ring‐opening polymerizations, zinc catalysts

Zinc complexes of a new family of sequential {ONNN} ligands are introduced and employed for the ring‐opening polymerization of rac‐lactide. The pyridine‐amine‐imine‐phenolate complexes lead to a rare combination of very high activities and isoselectivities yielding stereomultiblock poly(lactic acid) while their isomers are less active and essentially nonstereoselective.

1. Introduction

Among the biopolymers that may serve as sustainable alternatives to the petroleum‐based plastics, poly(lactic acid) (PLA) is the leading contestant, as it is produced on the largest scale, and its market share grows steadily.[ 1 , 2 , 3 ] The properties of PLA make it suitable for applications such as food packaging, 3D printing, fibers, etc., and its biodegradability makes it useful for biomedical applications.[ 4 , 5 , 6 ] PLA combines several environmentally attractive advantages, namely, it is derived from annually renewable resources, such as corn, sugar beets or sugar cane, or possibly even from municipal waste, and it can be composted postconsumption back to innocuous materials. More recently, recycling of PLA to monomer or upcycling of PLA to green solvents is being explored.[ 7 , 8 , 9 ] Of the different approaches for production of PLA, the one which is most explored and industrially practiced is the metal complex‐catalyzed ring‐opening polymerization (ROP) of lactide, the dilactone of lactic acid.[ 10 , 11 , 12 ] The stereoregularity of the PLA obtained by the ROP of lactide depends on the constitution of the monomer and the stereoselectivity of the employed catalyst.[ 5 , 13 ] Polymerization of rac‐Lactide, the equimolar mixture of L‐ and D‐lactide, may give rise to PLAs of several possible stereoregularities (in addition to stereoirregular PLA), stemming from the type of the stereoselectivity of the catalyst, homochiral‐ or heterochiral‐selective, the specific stereocontrol mechanism, enantiomorphic site control[ 14 , 15 ] or chain end control, and[ 16 , 17 ] the possible exchange of growing polymeryl chains between catalyst enantiomers.[ 18 , 19 , 20 ] The thermal and mechanical properties of the PLA are strongly affected by its stereoregularity: while homochiral isotactic PLAs (PLLA or PDLA) have a melting temperature of 180 °C, isotactic PLAs which are produced from both enantiomers of lactide in the forms of either PLLA/PDLA mixtures or as isotactic‐diblock copolymers (PLLA‐b‐PDLA) or isotactic‐multiblock copolymers ((‐PLLA‐b‐PDLA‐)n) tend to crystallize in a stereocomplex crystalline phase whose melting temperature may be higher by as much as 50 °C.[ 21 , 22 ] In contrast, heterotactic‐PLA and atactic‐PLA are amorphous.[ 23 ] The importance of introducing catalysts that would lead to sustainable PLA‐based materials of favorable properties, and in particular catalysts that would afford one of the forms of isotactic PLAs from rac‐lactide, is thus obvious.[ 13 ] Preferably, such catalysts should rely on abundant nontoxic metals.[ 11 , 12 ]

The ROP catalysts that exhibit the highest degrees of isoselectivity in polymerization of rac‐lactide are aluminum based and may operate by either the enantiomorphic‐site control or the chain‐end control mechanisms.[ 14 , 15 , 16 ] However, aluminum‐based ROP catalysts are notoriously sluggish.[ 15 ] Scarce examples of isoselective catalysts of other metals have been described in the past two decades, but their stereoselectivities are typically lower than those of aluminum catalysts.[ 11 , 13 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 ] The relative abundance of zinc and its lack of toxicity make it a perfect platform for the construction of ROP catalysts.[ 12 ] Indeed, in the past two decades, numerous zinc‐based catalysts have been introduced featuring a broad variety of structures and exhibiting a broad variety of activities, ranging from high activities at ambient temperatures to robustness at high temperatures.[ 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 ] However, in terms of stereoselectivity, zinc catalysts typically promote nonselective polymerizations,[ 40 ] while highly isoselective zinc‐based catalysts are scarce, with notable exceptions described by Du,[ 49 ] Ma,[ 50 , 51 , 52 ] and Cui.[ 53 ] Isoselective zinc‐based catalysts that exhibit high activities are even more scarce.

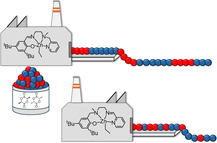

The design of the tetradentate‐monoanionic ligands introduced herein evolved stepwise from the tridentate‐monoanionic diamine‐monophenolate ligand described by Tolman, Hillmyer, and co‐workers (Scheme 1 ).[ 54 ] The {ONN}Zn—Et zinc complex of that ligand led to a highly active catalyst of rac‐lactide polymerization at room temperature; however, the PLA obtained was atactic. More recent zinc complexes of related tridentate‐monoanionic ligands such as pyridyl‐imine‐phenolate were also found to be nonstereoselective.[ 55 ] Attempting to induce tacticity,[ 56 , 57 ] we recently introduced sequential tetradentate‐monoanionic {ONNN} ligands that include a pyridyl end donor (previously introduced by Storr and co‐workers for iron chemistry)[ 58 ] to the zinc realm. {ONNN}Zn—Et‐type complexes of those ligands were indeed found to exhibit isoselectivity inclination in rac‐lactide polymerization; however, the highest PLA isotacticity attained was mild (P m = 0.80).[ 56 ] Herein, we introduce tetradentate‐monoanionic ligands, wherein one of the internal amine donors was replaced with an imine donor. Depending on the sequence of the donors and the substitution pattern, specific {ONNN}Zn—Et‐type complexes of this new ligand family were found to combine very high isoselectivities and activities.

Scheme 1.

Evolution of the current ligands: from tridentate ligands to sequential tetradentate pyridine‐diamine‐phenolate ligands to the sequential isomeric tetradentate pyridine‐amine/imine‐phenolate ligands.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Ligand Design and Synthesis

Inspired by the structural relationship between the sequential tetradentate‐dianionic ligands salan[ 59 ] and salalen,[ 60 , 61 ] namely, diamine‐diphenolates and amine‐imine‐diphenolates, we envisaged a similar relationship between the sequential tetradentate‐monoanionic ligands pyridine‐diamine‐phenolates[ 56 ] and the corresponding pyridine‐amine/imine‐phenolates.

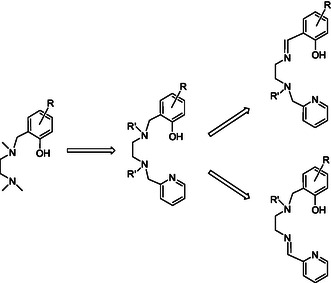

Two positional isomers may be envisioned for the latter ligands, namely, one where the internal amine donor is proximal to the peripheral pyridine group and the internal imine donor is proximal to the peripheral phenolate group (pyridine‐amine‐imine‐phenolate) and one where the internal donors are reversely located (pyridine‐imine‐amine‐phenolate) (Scheme 1). Multidentate ligands that include an internal imine donor typically exhibit a structural tendency wherein the two donors proximal to this imine donor are trans to one another due to the planarity of the sp2‐hybridized imine. For example, for octahedral complexes of salalen ligands, the sp2‐imine donor and its two neighboring donors occupy a meridional array of donors, while the sp3‐amine donor and its two neighboring donors occupy a facial array of donors completing an altogether mer‐fac geometry.[ 60 ] Trying to address a broad range of structural variations we targeted six ligands for this preliminary exploratory study, as outlined in Figure 1 . Lig1H—Lig5H are pyridine‐amine‐imine‐phenolate‐type ligands. Lig1H includes tert‐butyl phenolate substituents and an N‐Me donor group. Lig2H includes the same phenolate substituents and an N‐Et donor group. Lig3H and Lig4H both include an N‐Me group and ortho‐phenolate substituents which are either bulkier (adamantyl) or smaller (methyl), respectively. Lig5H is based on the chiral aminomethylpyrrolidine motif[ 60 ] and includes the same phenolate substitution pattern as that of Lig1H. Finally, Lig6H is the positional isomer of Lig1H, namely, the corresponding pyridine‐imine‐amine‐phenolate ligand.

Figure 1.

Pyridine‐amine‐imine‐phenolate ligands and pyridine‐imine‐amine‐phenolate ligand described in this work.

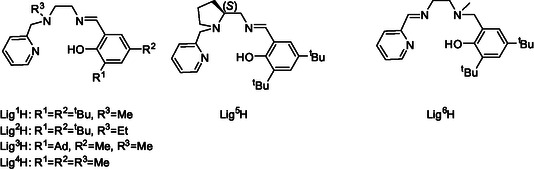

Lig1–5H were synthesized in a two‐step process. First, the corresponding diamine was condensed with the suitable substituted salicylaldehyde to produce the respective imine as intermediate. This intermediate was reacted with bromomethylpyridine in a substitution reaction on the secondary amine group to yield the final tetradentate ligands, as illustrated in Scheme 2 . The ligands were obtained in high yields and were purified by column chromatography (see Supporting Information). Preliminary attempts to produce Lig6H by condensation of monomethyl diaminoethane with pyridine caboxaldehyde as a first step led to formation of the cyclic aminal instead of the desired imine. We therefore chose the reverse reaction sequence, starting with the substitution reaction of 2‐bromomethyl‐di‐tert‐butylphenol which occurred preferentially on the secondary amine of monomethyl diaminoethane, followed by condensation with pyridine caboxaldehyde, to give Lig6H obtained in a moderate yield after purification.

Scheme 2.

Synthetic schemes including condensation followed by substitution for the pyridine‐amine‐imine phenolate ligands and substitution followed by condensation for the pyridine‐imine‐amine phenolate ligand.

2.2. Synthesis and Characterization of the Zinc Complexes

The six ligands Lig1–6H were reacted with ZnEt2 to give the corresponding Lig1–6Zn—Et complexes in high yields. 1H NMR characterization supported the formation of mononuclear rigid zinc complexes which were formed as single stereoisomers. Lig5H which is constructed around the chiral aminomethyl‐pyrrolidine formed as a single diastereomer, consistent with chiral induction from the ligand backbone to the ligand wrapping around the zinc center (see Figure S28, Supporting Information). Notably, the formation of a single five‐coordinate diastereomer was previously noted for the dianionic salalen {ONNO}‐type ligand assembled around the same chiral motif, when wrapping around aluminum.[ 61 ] Changes in the chemical shifts of all protons upon coordination supported the binding of these tetradentate ligands to the zinc via all their donors. Most notably, an essentially identical strong downfield shift of the proton ortho to the pyridine N‐donor was observed upon coordination of the pyridine‐amine‐imine‐phenolate ligands, from ≈8.47 ppm in Lig1–5H to ≈9.20 ppm in Lig1–5Zn—Et (compare, e.g., Figure S7,S8,S12 and S13, Supporting Information), consistent with a uniform binding of these ligands. In contrast, a more subtle downfield shift of this ortho proton in the “reverse” pyridine‐imine‐amine‐phenolate ligand, from 8.47 ppm in Lig6H to 8.65 ppm in Lig6ZnEt, may signify a different type of binding (Figure S34 and S35, Supporting Information).

Pentacoordinate complexes composed of a sequential tetradentate ligand and a monodentate ligand may adopt any geometry between perfect trigonal bipyramidal (τ 5 = 1) and square pyramidal (τ 5 = 0).[ 62 ] Crystallization attempts of all complexes were carried out by dissolving them in ether and cooling them down to −35 °C in the glovebox. Complexes Lig1Zn—Et, Lig3Zn—Et, and Lig5Zn—Et yielded single crystals suitable for X‐ray diffraction studies and their structures were solved. The structures exhibited similar coordination patterns: In all structures, all donors were bound to the metal, and the geometry was closer to square pyramidal than to trigonal bipyramidal with τ 5 = 0.16–0.35. Most notably, in all three structures the pyridine donor was found to occupy the apical position in the square pyramid, and the labile ethyl group was trans to the imine donor and cis to the phenolate oxygen. Relatively uniform bond lengths were found for these three complexes with the pyridine and imine donors binding tightly to the zinc, 2.13–2.17 and 2.06–2.07 Å, respectively, while the amine donor was bound much more loosely, 2.49–2.53 Å. Repeated crystallization attempts of Lig6Zn—Et did not yield well‐diffracting single crystals; however, the bis(trimethylsilyl)amido zinc complex Lig6Zn‐HMDS (hexamethyldosilazide) which was prepared from Lig6H and Zn(HMDS)2 afforded suitable single crystals from benzene and its structure was solved. Again, all donors were bound to the metal and the overall geometry was close to square pyramidal with τ 5 = 0.24. As expected, the change in the relative locations of the imine and the amine donors led to a different wrapping of the {ONNN} ligand, and the apical position (that cannot be occupied by the pyridine which is now proximal to the imine donor) is occupied by the phenolate oxygen (see Figure 2 ). Some differences in Zn—N bond lengths are found between the complexes above and Lig6Zn‐HMDS with the pyridine and imine donors now binding significantly looser (2.35 and 2.13 Å, respectively) and the amine donor binding significantly tighter (2.30 Å). The phenolate oxygen was also found to bind tighter in Lig6Zn‐HMDS (1.93 Å) relative to Lig1,3,5Zn‐Et (2.03–2.08 Å). We attribute these changes to the change in the {ONNN} ligand skeleton rather than to the change of the labile group from ethyl to HMDS.

Figure 2.

Selected crystallographic structures and molecular representations emphasizing the distinct {ONNN} ligand‐wrapping modes. H atoms omitted for clarity. Top: Lig1Zn—Et. Selected bond lengths (Å) and angles (°): N(pyridine)—Zn, 2.163(2); N(amine)—Zn, 2.489(2); N(imine)—Zn, 2.072(2); N(phenolate)—Zn, 2.048(2). O(phenolate)—Zn—N(amine), 155.91(8); C(ethyl)—Zn—N(imine), 146.02(10). Bottom: Lig6Zn—HMDS. Selected bond lengths (Å) and angles (°): N(pyridine)—Zn, 2.3545(18); N(amine)—Zn, 2.2995(18); N(imine)—Zn, 2.1330(18); N(phenolate)—Zn, 1.9318(15). N(amine)—Zn—N(pyridine), 146.85(7); N(HMDS)—Zn—N(imine), 132.28(8).

2.3. Ring‐Opening Polymerization Catalysis of rac‐Lactide

We investigated the activities and possible stereoselectivity preferences of complexes Lig1–6Zn—Et in the ROP of rac‐lactide. The active catalysts are required to include a labile monodentate alkoxo group, which is typically a benzyloxy group. Monitoring the exchange reactions by 1H NMR spectroscopy, we found that the reactions of the ethyl complexes with benzyl alcohol required between 2 and 7 h for attaining full conversion and that the tetradentate ligands did not detach from the zinc. The spectra were consistent with mononuclear complexes of the form LigZn‐OBn (see Figure S10, Supporting Information), yet the benzyloxy complexes were less defined than their parent ethyl complexes, possibly due to fluxionality. A similar behavior was previously found for the pyridine‐diamine‐phenolate complexes.[ 56 ] Polymerization reactions were run in toluene by adding an equimolar quantity of BnOH to the specific ethylzinc complex and stirring at room temperature (RT) until full exchange was reached. Then, 300 equiv of rac‐lactide were added, and the reaction was stirred at RT for a given time, after which the polymerization was stopped by exposure to air and the solvent was removed under vacuum. The polymer samples were analyzed by size exclusion chromatography (SEC) for determination of number‐average molecular weight (M n) and dispersity (Ð) and by homonuclear decoupled 1H NMR spectroscopy to determine their tacticities.

The polymerization results are summarized in Table 1 . We found that, for most catalysts, very short polymerization times were required for attaining almost quantitative conversions. Thus, the parent complex Lig1Zn—Et as well as the complex Lig3Zn—Et featuring adamantyl‐phenolate substituents led to 97% conversions after 5 min, while Lig4Zn—Et which bears the smaller methyl‐phenolate substituents led to slightly reduced conversion of 95%. Lig5Zn—Et which includes the chiral aminomethyl‐pyrrolidine ligand backbone led to the highest conversion, 98% after 5 min. Complex Lig2Zn—Et which bears an N‐ethyl internal donor led to a lower conversion of 83% after the same time, possibly caused by protrusion of the ethyl group into the active pocket. Finally, Lig6Zn—Et, the complex of the ligand with the opposite skeleton, was the least active of all and led to 80% conversion after 10 min. In contrast, attempting to polymerize 300 equiv of rac‐lactide with Lig1Zn—Et without adding an alcohol did not lead to any polymerization after 2 h, reflecting the inability of lactide to insert into a zinc‐carbon bond. The dispersities of the obtained PLA samples were narrow, between 1.08 and 1.22, consistent with well‐behaved polymerizations. The number‐average molecular weights of the polymers were consistent with their calculated values, except for Lig6Zn—Et for which the molecular weight was substantially lower than calculated. Of course, the most intriguing aspect of these polymerizations is the stereoselectivity of these catalysts. We found that complexes Lig1–5Zn—Et that include the pyridine‐amine‐imine‐phenolate ligands all led to isotactic PLA, which is uncommon for zinc‐based catalysts. The degree of the isotacticity was found to depend on the ligand skeleton and the substitution pattern. Thus, Lig1Zn—Et which is based on the diaminoethane skeleton and bears tert‐butyl phenolate substituents and an N‐Me donor gave rise to a very high degree of isotacticity of P m = 0.90 which is amongst the highest ever described for zinc catalysts at RT,[ 49 ] and Lig5Zn—Et which is based on the chiral aminomethyl‐pyrrolidine skeleton and bears the same tert‐butyl phenolate substituents gave rise to an almost identical degree of isotacticity of P m = 0.88. All deviations from this substitution pattern led to substantial decrease in isoselectivity: replacing the N—Me substituent with an N—Et substituent (Lig2Zn—Et) resulted in P m = 0.82; increasing the bulk of the phenolate ortho‐substituent to an adamantyl group (Lig3Zn‐Et) led to an even lower isotacticity of P m = 0.76; and decreasing the bulk of the phenolate ortho‐substituent to a methyl group (Lig4Zn‐Et) also led to a lower isotacticity of P m = 0.80. Yet the most pronounced deviation from isotacticity was witnessed with the complex of the reversed ligand Lig6Zn—Et that gave an only slightly inclined isotactic PLA of P m = 0.60. The stark difference in isotacticity attained with the complexes of the isomeric ligands Lig1 and Lig6 can be appreciated when comparing the homo‐decoupled 1H NMR spectra of the corresponding polymers in Figure 3 . Obviously, the design of a ligand that would lead to desired activities and stereoselectivities has to take in consideration not only the number of donors and their character, but also their exact location and the wrapping tendency of the entire ligand which would dictate the stereochemical relationships in the complex.

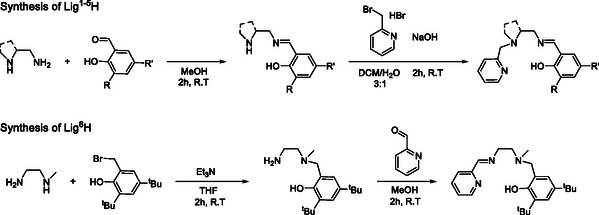

Table 1.

Polymerizations of rac‐lactide.

| Entrya) | Cat. | Time [min] | Conv.b) | Activityc) | M n d) calc. | M n e) | Ð f) | P m g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lig1ZnEt | 5 | 0.97 | 3500 | 41,200 | 39,900 | 1.22 | 0.90 |

| 2 | Lig2ZnEt | 5 | 0.83 | 3000 | 35,800 | 39,000 | 1.18 | 0.82 |

| 3 | Lig3ZnEt | 5 | 0.97 | 3500 | 41,200 | 39,400 | 1.10 | 0.76 |

| 4 | Lig4ZnEt | 5 | 0.95 | 3400 | 40,400 | 39,300 | 1.20 | 0.80 |

| 5 | Lig5ZnEt | 5 | 0.98 | 3500 | 41,600 | 39,900 | 1.10 | 0.88 |

| 6 | Lig6ZnEt | 10 | 0.80 | 1400 | 34,000 | 14,800 | 1.08 | 0.60 |

| 7h) | Lig1ZnEt | 10 | 0.89 | 5300 | 12,800 | 12,100 | 1.24 | 0.88 |

| 8i) | Lig1ZnEt | 3 | 0.99 | 19,800 | 14,400 | 13,800 | 1.20 | – |

| 9i) | Lig5ZnEt | 3 | 0.98 | 39,200 | 28,200 | 26,900 | 1.20 | – |

| 10k) | Lig1ZnEt | 10 | 0.83 | 4900 | 12,000 | 11,900 | 1.31 | 0.50 |

Polymerizations were run in toluene at RT after activation of the LigZn—Et complexes with 1 equiv of benzyl alcohol in a 1:300 catalyst to rac‐lactide ratio.

Conversion assessed by 1H NMR.

Mol monomer consumed × mol catalyst employed−1 × h−1.

Calculated from monomer conversion assuming full benzyl alcohol participation.

Calculated from SEC; a correction factor of 0.58 employed for calculating M n relative to polystyrene standards.

Calculated from SEC

P m is the probability of forming a meso dyad, determined by homodecoupled 1H{1H} NMR spectroscopy.

Lig1ZnEt/benzyl alcohol/rac‐lactide ratio of 1:10:1000.

L‐lactide as monomer; Lig1ZnEt/benzyl alcohol/L‐lactide ratio of 1:10:1000.

L‐lactide as monomer; Lig5ZnEt/benzyl alcohol/L‐lactide ratio of 1:10:2000.

Lig1ZnEt/benzyl alcohol/rac‐lactide ratio of 1:10:1000; polymerization at 150 °C.

Figure 3.

Homo‐decoupled 1H NMR spectra of PLA obtained from polymerization of rac‐lactide with the isomeric complexes Lig1Zn—Et (left, highly isotactic) and Lig6Zn—Et (right, essentially atactic).

Isoselective catalysts which follow the enantiomorphic‐site control mechanism polymerize rac‐lactide to give isotactic PLA having isolated stereochemical errors, whereas isoselective catalysts which follow the chain‐end control mechanism give isotactic PLA having propagating stereochemical errors or in other words, an isotactic stereo‐multiblock microstructure.[ 13 ] These microstructures may be distinguished by the tetrad distribution in the 1H NMR spectra. For enantiomorphic‐site control, a typical RR‐RR‐SS‐RR‐RR sequence of lactidyl units would give an mmmrmrmmm sequence of relationships between neighboring stereocenters (m=meso, r=racemo) and a tetrad distribution of mmr:mrm:rmr:rmm of 1:2:1:1 in addition to the dominant mmm tetrad. For chain‐end control, a typical RR‐RR‐RR‐SS‐SS‐SS sequence of lactidyl units would give an mmmmmrmmmmm sequence of relationships between neighboring stereocenters, and a Bernoullian statistics of tetrad distribution wherein the rmr tetrad is diminished relative to the others, and approaches zero for very high isotacticities. The HD 1H NMR of the highly isotactic PLA obtained with Lig1Zn—Et reveals a tetrad pattern which is consistent with a chain‐end control mechanism. Yet, one cannot exclude a mechanism which involves an enantiomorphic‐site control combined with a polymeryl exchange between two catalyst enantiomers following an occasional opposite lactide misinsertion. To address this possibility, the tetrad pattern in the isotactic PLA obtained with Lig5Zn—Et was examined. Significantly, Lig5H was employed in its enantiomerically pure (S)‐form, and Lig5Zn—Et was obtained as a single diastereomer, so polymeryl exchange events, if those take place, should be degenerate. As the tetrad pattern in the HD 1H NMR of the polymer attained with Lig5Zn—Et is essentially identical to that attained with Lig1Zn—Et (compare Figure S39 and S44, Supporting Information), we conclude that polymeryl exchange events are not significant, and that the stereocontrol mechanism in these zinc complexes is pure chain‐end control.

Trying to gain further perception on the activity of these catalysts, we ran several additional polymerization runs with Lig1Zn—Et. First, we polymerized 1000 equiv of rac‐lactide in the presence of 10 equiv of benzyl alcohol (Table 1, entry 7). We found that after a 10 min polymerization run, 89% of the monomer were consumed consistent with a very high activity. The polymer obtained was of the expected molecular weight and its dispersity was only slightly broader than that of the polymer obtained with a single equiv of benzyl alcohol, namely, these catalysts are able to produce more than a single polymeric chain by exchange of metal‐bound polymeryl group with hydroxyl‐terminated polymer chains. Significantly, the obtained polymer exhibited a degree of isotacticity which was only marginally lower than that obtained in the original polymerization run (P m = 0.88). One should consider that the activity of ROP catalysts toward rac‐lactide relative to homochiral lactide diminishes as their degree of isoselectivity increases (and for the opposite preference, heteroselective ROP catalysts are more active toward rac‐lactide relative to homochiral lactide).[ 63 ] To obtain an estimate of the activity of these catalysts without the interference of stereoselectivity issues, we polymerized 1000 equiv of L‐lacide with Lig1Zn—Et in the presence of 10 equiv of benzyl alcohol. We found that after 3 min, essentially full monomer conversion was attained, corresponding to a very high activity for zinc catalysts, exceeding that of the original Tolman/Hillmyer zinc catalyst (Table 1, entry 8). Along the same lines, 98% of 2000 of L‐lacide were polymerized with Lig5Zn‐Et in the presence of 10 equiv of benzyl alcohol after 3 min signifying an even higher activity (Table 1, entry 9). These catalysts are thus among the most active zinc catalysts at room temperature ever described.[ 41 ] We also attempted the polymerization of neat rac‐lactide with Lig1Zn—Et at 150 °C and found that the catalyst was active at this elevated temperature as well (Table 1, entry 10). Not surprisingly, the PLA obtained under these conditions was atactic. Characterization of a PLA sample prepared from rac‐lactide with Lig2Zn—Et and featuring a degree of isotacticity of P m = 0.82 by wide‐angle X‐ray diffraction (WAXD) revealed a crystallinity which results from a stereocomplex form of PLA, while its characterization by differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) showed melting temperature and enthalpy values comparable to those previously observed in samples of similar P m (see Figure S48, S49, Supporting Information).[ 64 ] As expected, the atactic sample prepared at 150 °C was found to be noncrystalline. Finally, we attempted the polymerization of caprolactone with Lig1Zn—Et and found that 300 equiv were fully consumed within 5 min, yielding a polymer with the expected molecular weight having a relatively narrow dispersity of Ð = 1.30.

3. Conclusions

The development of catalysts for ROP of lactide and related lactones should take in consideration the availability and lack of toxicity of the metal on which they are based. From this perspective, zinc is a prime candidate. Yet, although investigated for more than two decades, except for few exceptions, zinc‐based catalysts are typically not highly isoselective. The new family of ligands introduced herein, tetradentate monoanionic {ONNN}‐type ligands readily synthesized by a combination of condensation and substitution steps, leads to zinc complexes that exhibit unusually high isoselectivities in rac‐lactide solution polymerization at room temperature. Moreover, these complexes polymerize rac‐lactide and even more so, L‐lactide, with exceptionally high activities. Structural parameters, and in particular the relative location of the internal donors, are found to play a major role on the stereoselectivity of these catalysts as well as their activities, demonstrating that valuable ligands are more than the sum of their donors. We are currently developing related ligands with the goal of introducing novel catalysts that would lead to sustainable polymers and copolymers of desired properties.

4. Experimental Section

4.1.

4.1.1.

General Information

The experiments that required inert atmosphere were performed in a glovebox under dry nitrogen. Diethyl ether and tetrahydrofuran (THF) were distilled under argon from Na/benzophenone. Dichloromethane (DCM) was distilled under argon from CaH2. Toluene was distilled under argon over sodium. Pentane was washed with HNO3/H2SO4 and distilled under argon from Na/benzophenone/tetraglyme.

The following starting materials were purchased and used without any purification: N‐methylethylenediamine and 3,5‐di‐tert‐butylsalicylaldehyde were purchased from Alfa Aeser. Picolinaldehyde and 2‐bromomethylpyridine were purchased from Acros Organics. 3,5‐dimethylsalycilaldehyde was purchased from Merck. (S)‐2‐pyrrolidinemethaneamine was purchased from Angene Chemicals. N‐Ethylethylenediamine was purchased from Fluka Chemicals. 2‐(Bromomethyl)‐4,6‐di‐tert‐butylphenol[ 56 ] and 3‐adamantan‐1‐yl‐2‐hydroxy‐5‐methylbenzaldehyde[ 65 ] were synthesized based on previously published procedures. Rac‐lactide was prepared by mixing equal amounts of L‐ and D‐lactide that were obtained from Musashino. The purification included recrystallization in toluene followed by sublimation.

The 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra were obtained using a Bruker Avance III 400 or 500 MHz spectrometers. When using CDCl3 as a solvent, TMS was used as an internal standard (chemical shift of δ 0.00 for 1H NMR and 13C NMR). When using C6D6 as a solvent, the residual C6D5H signal was used as an internal standard (chemical shift of δ 7.16 for 1H NMR and δ 128.70 for 13C NMR). Mass spectra were obtained using a SYNAPT‐High Definition Mass Spectrometer. PLA molecular weights and dispersities were measured by SEC using TSKgel GMHHR‐M and TSKgel G 3000 HHR columns set on a Jasco high pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) instrument equipped with a refractive index detector using THF (HPLC grade) as the eluting solvent. The PLA molecular weights were determined relative to polystyrene standards by multiplication by a correction factor of 0.58.

Synthesis of Selected Ligands and Complexes: Lig1H

To a solution of N‐methylethylenediamine (0.300 g, 4.11 mmol) in 15 mL of MeOH, 3,5‐di‐tert‐butylsalicylaldehyde (0.961 g, 4.11 mmol) was added. The reaction mixture was stirred at RT for 2 h and the solvent was removed under vacuum. The intermediate imine 2,4‐di‐tert‐butyl‐6‐(((2‐(methylamino)ethyl)imino)methyl)phenol) was obtained in quantitative yield and no further purification was required. The imine (1.131 g, 3.90 mmol) was dissolved in 20 mL of DCM/H2O (3:1) mixture. NaOH (0.468 g, 11.70 mmol) and 2‐(bromomethyl)pyridine hydrobromide (0.982 g, 3.90 mmol) were added and the reaction was stirred vigorously at RT for 2 h. The organic phase was washed with brine (3 × 30 mL) and was dried over MgSO4. The solvent was removed under vacuum, and the crude product was purified by flash column chromatography over silica gel (DCM/MeOH 9:1) and obtained as an orange oil in 75% yield.

1H NMR (400 MHz in CDCl3): δ 8.54 (ddd, 1H, J = 4.9, 1.7, 0.8 Hz, PyH), 8.37 (s, 1H, NCH), 7.61 (td, 1H, J = 7.6, 1. 8 Hz, PyH), 7.46 (d, 1H, J = 7.8 Hz, PyH), 7.39 (d, 1H, J = 2.4 Hz, ArH), 7.16 (ddd, 1H, J = 6.3, 5.0, 1.1 Hz, PyH), 7.09 (d, 1H, J = 2.4 Hz, ArH), 3.77‐3.73 (m, 4 H, CH 2), 2.80 (t, 2H, J = 6.4 Hz, CH 2), 2.39 (s, 3H, CH 3), 1.47 (s, 9H, C(CH 3)3), 1.33 (s, 9H, C(CH 3)3). 13C NMR (100 MHz in CDCl3): δ 166.8 (C), 159.6 (NCH), 158.5 (COH), 149.3 (CH), 140.1 (C), 136.9 (CH), 136.7 (C), 127.0 (CH), 126.1 (CH), 123.3 (CH), 122.2 (CH), 118.2 (C), 64.4 (CH2), 58.1 (CH2), 57.5 (CH2), 43.1 (CH3), 35.3 (C(CH3)3), 34.4 (C(CH3)3), 31.8 (C(CH3)3), 29.7 (C(CH3)3). HRMS (ESI): Calc for C24H36N3O: 382.2858, found: 382.2864 (MH+).

Synthesis of Selected Ligands and Complexes: Lig6H

Step 1: N‐methylethane‐1,2‐diamine (0.294 g, 3.97 mmol) was dissolved in THF (20 mL) and Et3N (1.202 g, 11.91 mmol) was added. The reaction mixture was cooled to 0 °C degrees and 2‐(bromomethyl)‐4,6‐di‐tert‐butylphenol (1.192 g, 3.98 mmol) mixture in THF was added slowly, and the reaction mixture was stirred for 2 h at RT. The solution was filtered and the solvent was removed under reduced pressure. The crude product was purified by column chromatography over silica gel (DCM/MeOH 9:1) and obtained as an orange oil in 24% yield.

1H NMR (400 MHz in CDCl3): δ 7.20 (d, 1H, J = 2.4 Hz, ArH), 6.82 (d, 1H, J = 2.3 Hz, ArH), 3.70 (s, 2H, CH 2), 2.87 (t, 2H, J = 6.2 Hz, CH 2), 2.53 (t, 2H, J = 6.2 Hz, CH 2), 2.32 (s, 3H, CH 3), 1.40 (s, 9H, C(CH 3)3), 1.27 (s, 9H, C(CH 3)3). 13C NMR (100 MHz in CDCl3): δ 153.9 (COH), 140.5 (C), 135.4 (C), 123.2 (CH), 122.7 (CH), 121.2 (C), 62.4 (CH2), 59.3 (CH2), 41.4 (CH3), 39.1 (CH2), 34.7 (C(CH3)3), 34.0 (C(CH3)3), 31.6 (C(CH3)3), 29.5 (C(CH3)3). MS(APPI): Calc for : 292.3, found: 292.4.

Step 2: 2‐(((2‐aminoethyl)(methyl)amino)methyl)‐4,6‐di‐tert‐butylphenol (0.150 g, 0.51 mmol) was dissolved in MeOH and picolinaldehyde (0.956 g, 8.93 mmol) was added. The reaction mixture was stirred at RT for 2 h, and the solvent was removed under vacuum. The crude product was purified by column chromatography over silica gel (DCM/MeOH 9:1) and was obtained as an orange oil in 80% yield.

1H NMR (400 MHz in CDCl3): δ 8.63 (ddd, 1H, J = 4.8, 2.6, 0.70 Hz, PyH), 8.43 (s, 1H, NCH), 8.11 (d, 1H, J = 7.9 Hz, PyH), 7.74 (td, 1H, J = 7.71,1.7 Hz, PyH), 7.30 (ddd, 1H, J = 7.5, 4.9, 1.3 Hz, PyH), 7.19 (d, 1H, J = 2.4 Hz, ArH), 6.82 (d, 1H, J = 2.4 Hz, ArH), 3.86 (t, 2H, J = 6.1 Hz, CH 2), 3.76 (s, 2H, CH 2), 2.90 (t, 2H, J = 6.1, CH 2), 2.36 (s, 3H, CH 3), 1.40 (s, 9H, C(CH 3)3), 1.29 (s, 9H, C(CH 3)3). 13C NMR (100 MHz in CDCl3): δ 163.1 (C), 154.3 (NCH), 154.2 (COH), 149.2 (CH), 140.1 (C), 136.5 (CH), 135.4 (C), 124.7 (CH), 123.2 (CH), 122.7 (CH), 121.6 (CH), 121.1 (C), 62.2 (CH2), 58.3 (CH2), 56.8 (CH2), 41.0 (CH3), 34.7 (C(CH3)3), 34.0 (C(CH3)3), 31.7 (C(CH3)3), 29.4 (C(CH3)3). HRMS (ESI): Calc for C24H36N3O: 382.2858, found: 382.2864 (MH+).

Synthesis of Selected Ligands and Complexes: Lig1ZnEt

Lig1H (108 mg, 0.28 mmol) was dissolved in 2 mL of toluene and 0.29 mL of diethyl zinc solution (1 M in hexane) was added. The reaction mixture was stirred at RT for 2 h. The solvent was removed under vacuum leaving a yellow oil. The crude complex was washed with 2 mL of pentane, resulting in a yellow solid in quantitative yield. Single crystals of the complex were grown from diethyl ether at −35 °C

1H NMR (400 MHz in C6D6): δ 9.20 (ddd, 1H, J = 5.3, 2.3, 0.8 Hz, PyH), 7.71 (d, 1H, J = 2.6 Hz, ArH), 7.64 (s, 1H, NCH), 6.90 (d, 1H, J = 2.9 Hz, ArH), 6.75 (td, 1H, J = 7.7, 2.2 Hz, PyH), 6.45 (ddd, 1H, J = 7.2, 5.2, 1.1 Hz, PyH), 6.27 (d, 1H, J = 7.7 Hz, PyH), 3.13 (brs, 2H, CH 2), 2.80 (brs, 2H, CH 2), 2.12 (s, 3H, CH 3), 1.95 (s, 9H, C(CH 3)3), 1.87 (t, 3H, J = 8.1, ZnCH2CH 3), 1.75 (t, 2H, J = 5.2, CH 2), 1.45 (s, 9H, C(CH 3)3), 0.67 (q, 2H, J = 8.1, ZnCH 2CH 3). 13C NMR (100 MHz in C6D6): δ 171.2 (C), 169.6 (NCH), 156.3 (COH), 150.8 (CH), 141.6 (C), 137.6 (CH), 132.4 (C), 129.6 (CH), 128.8 (CH), 123.2 (CH), 122.8 (CH), 118.3 (C), 61.5 (CH2), 57.4 (CH2), 55.7 (CH2), 41.9 (CH3), 36.1 (C(CH3)3), 34.0 (C(CH3)3), 32.0 (C(CH3)3), 30.4 (C(CH3)3), 14.8 (ZnCH2 CH3), −1.2 (ZnCH2CH3).

Synthesis of Selected Ligands and Complexes: Lig6Zn‐Et

The preparation procedure was the same as that described above for Lig1ZnEt using Lig6H (0.029 g, 0.08 mmol) and 0.08 mL of diethyl zinc solution 1M in hexane as reactants. The final product was obtained in quantitative yield. Single crystals of the complex were grown from diethyl ether at −35 C.

1H NMR (400 MHz in C6D6): δ 8.65 (d, 1H, J = 4.6 Hz, PyH), 7.60 (d, 1H, J = 2.7 Hz, ArH), 7.26 (t, 1H, J = 1.65 Hz, NCH), 7.08 (d, 1H, J = 7.7 Hz, PyH), 7.02 (d, 1H, J = 2.2 Hz, ArH), 7.00 (dd, 1H, J = 7.6, J = 1.7 Hz, PyH), 6.58 (ddd, 1H, J = 6.1, 4.7, 1.1 Hz, PyH), 3.63 (d, 1H, J = 11.4 Hz, CH), 3.24 (d, 1H, J = 11.4 Hz, CH), 2.83–2.74 (m, 2H, H 2), 2.26–2.22 (m, 1H, CH), 2.05 (s, 3H, CH 3), 2.04–2.00 (m, 1H, CH), 1.74 (s, 9H, C(CH 3)3), 1.49 (s, 9H, C(CH 3)3), 1.41 (t, 3H, J = 8.05 Hz, ZnCH2CH 3), 0.62–0.45 (m, 1H, ZnCH 2CH3), 0.41–0.35 (m, 1H, ZnCH 2CH3). 13C NMR (100 MHz in C6D6): δ 165.0 (C), 161.7 (NCH), 149.9 (COH), 149.4 (CH), 137.9 (C), 136.7 (CH), 133.4 (C), 126.1 (CH), 125.6 (CH), 124.6 (CH), 123.6 (C), 122.6 (CH), 60.8 (CH2), 54.5 (CH2), 52.7 (CH2), 43.4 (C(CH3)3), 35.5 (C(CH3)3), 33.9 (NCH3), 32.3 (C(CH3)3), 30.1 (C(CH3)3), 14.1 (ZnCH2 CH3), −2.3 (ZnCH2CH3).

Synthesis of Selected Ligands and Complexes: Lig6Zn‐HMDS

Lig6H (0.024 g, 0.06 mmol) was dissolved in 2 mL of toluene and added to a solution of Zn(HMDS)2 (0.025 g, 0.06 mmol) in 2 mL of toluene. The reaction mixture was stirred at RT for 2 h. The solvent was removed under vacuum and the oily product was washed with pentane until it became a white solid. The final product was obtained in quantitative yield. Single crystals of the complex were grown from benzene at RT.

Crystallography

Crystals suitable for X‐ray diffraction analysis were grown either from ether solutions cooled to −35 °C (Lig1Zn—Et, Lig3Zn—Et, and Lig5Zn—Et) or from a benzene solution at RT (Lig6Zn‐HMDS). The crystals were mounted on a glass needle with paratone oil, and all data were collected at 110(2)K. Single‐crystal X‐ray diffraction data were collected on a Bruker KAPPA APEX Duo diffractometer equipped with an APEX II CCD (charge coupled device) detector using a MoKα ImuS microfocus X‐ray source (α = 0.71073 Å). Unit cell determination, refinement, and data collection were done using the Bruker APEX3 SHELXTL Software Package, data reduction and integration were performed using SAINT v8.34A (Bruker), and absorption corrections and scaling were done using SADABS‐2014/5 (Bruker). All the crystal structures were solved through the ShelXle package using SHELXT and the structures were refined using SHELXL.[ 66 , 67 ] All nonhydrogen atoms were refined anisotropically. All the figures were generated using Mercury 3.0. Deposition Numbers 2421393 (for Lig1Zn—Et), 2421378 (for Lig3Zn—Et), 2424495 (for Lig5Zn—Et), and 2424492 (for Lig6Zn—HMDS) contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data were provided free of charge from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre.

Typical Polymerization Procedure

A solution of the catalyst (5 μmol) in toluene (5 mL) was prepared, and one equiv of benzyl alcohol was added. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for the required duration. Rac‐lactide (216 mg, 300 equiv) was added, and stirring was continued at room temperature until the solution has cleared. The reaction was then terminated by exposure to air, and the volatile components were removed under vacuum. The conversion was determined by 1H NMR of the polymerization mixture, and the remaining monomer was removed by washings with methanol. P m, the probability of forming a meso dyad, was determined by homodecoupled 1H{1H} NMR spectroscopy (CDCl3, 400 MHz).[ 68 ] Polymerizations employing higher monomer and benzyl alcohol ratios to catalyst, as well as polymerizations of L‐lactide and caprolactone, were performed similarly.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Professor Vincenzo Venditto and Dr. Raffaella Rescigno from the Department of Chemistry and Biology and A. Zambelli of the University of Salerno, Italy, for measurement of the wide‐angle X‐ray diffraction and the differential scanning calorimetry of the PLA samples. The authors thank Professor Moshe Portnoy and Dr. Tomer Rosen (TAU) for helpful discussions. The authors acknowledge financial support by grant no. 1776/22 of the Israel Science Foundation, grant no. 2711/17 of the Israel Science Foundation and the University Grant Commission of India, and grant no. 86599 of the Israel Ministry of Science Technology and Space.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the supplementary material of this article.

References

- 1. Naser A. Z., Deiaba I., Darras B. M., RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 17151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Shi C., Quinn E. C., Diment W. T., Chen E. Y.‐X., Chem. Rev. 2024, 124, 4393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Abdelshafy A., Hermann A., Herres‐Pawlis S., Walther G., Global Challenges 2023, 7, 2200218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Farah S., Anderson D. G., Langer R., Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2016, 107, 367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hu Y., Zhang Y., Pang X., Chen X. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, 2412185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mohan S., Panneerselvam K., Mater. Today: Proc. 2022, 56, 3241. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Payne J., Jones M. D., ChemSusChem 2021, 14, 4041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kumar R., Sadeghi K., Jang J., Seo J., Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 882, 163446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. McGuire T. M., Buchard A., Williams C., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 19840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zhang X., Fevre M., Jones G. O., Waymouth R. M., Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mankaev B. N., Karlov S. S., Materials 2023, 16, 6682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yadav N., Chundawat T. S., ChemistrySelect 2024, 9, e202401619. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tschan M. J.‐L., Gauvin R. M., Thomas C. M., Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 13587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Spassky N., Wisniewski M., Pluta C., Le Borgne A., Macromol. Chem. Phys. 1996, 197, 2627. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pang X., Duan R., Li X., Hu C., Wang X., Chen X., Macromolecules 2018, 51, 906. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nomura N., Ishii R., Yamamoto Y., Kondo T., Chem. Eur. J. 2007, 13, 4433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Moccia S., D’Alterio M. C., Romano E., De Rosa C., Talarico G., Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2025, 46, 2400733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ovitt T. M., Coates G. W., J. Polym. Sci., Part A: Polym. Chem. 2000, 38, 4686. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ovitt T. M., Coates G. W., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hador R., Botta A., Venditto V., Lipstman S., Goldberg I., Kol M., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 14679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ikada Y., Jamshidi K., Tsuji H., Hyon S. H., Macromolecules 1987, 20, 904. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rosen T., Goldberg I., Venditto V., Kol M., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 12041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Romain C., Heinrich B., Laponnaz S. B., Dagorne S., Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 2213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Li X., Jia Z., Pan X., Wu J., Chem. Asian J. 2019, 14, 662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fernández‐Millán M., Ortega P., Cuenca T., Cano J., Mosquera M. E. G., Organometallics 2020, 39, 2278. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hu J., Kan C., Wang H., Ma H., Macromolecules 2018, 51, 5304. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rosen T., Rajpurohit J., Lipstman S., Venditto V., Kol M., Chem. Eur. J. 2020, 26, 17183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bhattacharjee J., Harinath A., Nayek H. P., Sarkar A., Panda T. K., Chem. Eur. J. 2017, 23, 9319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kirk S. M., Kociok‐Köhn G., Jones M. D., Organometallics 2016, 35, 3837. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Stopper A., Rosen T., Venditto V., Goldberg I., Kol M., Chem. Eur. J. 2017, 23, 11540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Myers D., White A. J. P., Forsyth C. M., Bown M., Williams C. K.. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 5277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yuntawattana N., McGuire T. M., Durr C. B., Buchard A., Williams C. K., Catal. Sci. Technol. 2020, 10, 7226. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Specklin D., Fliedel C., Hild F., Mameri S., Karmazin L., Baillyc C., Dagorne S., Dalton Trans. 2017, 46, 12824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Dąbrowska A. M., Hurko A., Durka K., Dranka M., Horeglad P., Macromolecules 2018, 51, 906. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Driscoll O. J., Leung C. K. C., Mahon M. F., McKeown P., Jones M. D., Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 2018, 5129. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Stewart J. A., McKeown P., Driscoll O. J., Mahon M. F., Ward B. D., Jones M. D., Macromolecules 2019, 52, 5977. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Marin P., Tschan M. J.‐L., Isnard F., Robert C., Haquette P., Trivelli X., Chamoreau L.‐M., Guérineau V., del Rosal I., Maron L., Venditto V., Thomas C. M., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 12585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Xu T., Yang G., Liu C., Lu X., Macromolecules 2017, 50, 515. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fortun S., Daneshmand P., Schaper F., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 13669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Cheng M., Attygalle A. B., Lobkovsky E. B., Coates G. W., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 11583. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Thevenon A., Romain C., Bennington M. S., White A. J. P., Davidson H. J., Brooker S., Williams C. K., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 8680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Santulli F., Pappalardo D., Lamberti M., Amendola A., Barba C., Sessa A., Tepedino G., Mazzeo M., ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 15699. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Santulli F., Bruno F., Mazzeo M., Lamberti M., ChemCatChem 2023, 15, e202300498. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hermann A., Hill S., Metz A., Heck J., Hoffmann A., Hartmann L., Herres‐Pawlis S., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 21778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Fuchs M., Schäfer P. M., Wagner W., Krumm I., Walbeck M., Dietrich R., Hoffmann A., Herres‐Pawlis S., ChemSusChem 2023, 16, e202300192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. McKeown P., Román‐Ramírez L. A., Bates S., Wood J., Jones M. D., ChemSusChem 2019, 12, 5233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. D’Auria I., Ferrara V., Tedesco C., Kretschmer W., Kempe R., Pellecchia C., ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2021, 3, 4035. [Google Scholar]

- 48. D’Alterio M. C., D’Auria I., Gaeta L., Tedesco C., Brenna S., Pellecchia C., Macromolecules 2022, 55, 5115. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Abbina S., Du G., ACS Macro Lett. 2014, 3, 689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kan C., Hu J., Huang Y., Wang H., Ma H., Macromolecules 2017, 50, 7911. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Gong Y., Ma H., Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 10112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wang H., Ma H., Macromolecules 2024, 57, 6156. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Mou Z., Liu B., Wang M., Xie H., Li P., Li L., Li S., Cui D., Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 11411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Williams C. K., Breyfogle L. E., Choi S. K., Nam W., Young V. G., Hillmyer M. A., Tolman W. B., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 11350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Santulli F., Lamberti M., Mazzeo M., ChemSusChem 2021, 14, 5470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Rosen T., Popowski Y., Goldberg I., Kol M., Chem. Eur. J. 2016, 22, 11533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Stasiw D. E., Luke A. M., Rosen T., League A. B., Mandal M., Neisen B. D., Cramer C. J., Kol M., Tolman W. B., Inorg. Chem. 2017, 56, 14366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Chiang L., Savard D., Shimazaki Y., Thomas F., Storr T., Inorg. Chem. 2014, 53, 5810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Hormnirun P., Marshall E. L., Gibson V. C., White A. J. P., Williams D. J., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 2688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Yeori A., Gendler S., Groysman S., Goldberg I., Kol M., Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2004, 7, 280. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Pilone A., Press K., Goldberg I., Kol M., Mazzeo M., Lamberti M., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 2940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Addison A. W., Rao T. N., Reedijk J., van Rijn J., Verschoor G. C., J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 1984, 1349. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Chmura A. J., Davidson M. G., Frankis C. J., Jones M. D., Lunn M. D., Chem. Commun. 2008, 1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Hador R., Lipstman S., Rescigno R., Venditto V., Kol M., Chem. Commun. 2020, 56, 13528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Dossetter A. G., Jamison T. F., Jacobsen E. N., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1999, 38, 2398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Hübschle C. B., Sheldrick G. M., Dittrich B., J. Appl. Cryst. 2011, 44, 1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.a) Sheldrick G. M., Acta Cryst. 2015, A71, 3; [Google Scholar]; b) Sheldrick G. M., Acta Cryst. 2015, C71, 3. [Google Scholar]

- 68. Chamberlain B. M., Cheng M., Moore D. R., Ovitt T. M., Lobkovsky E. B., Coates G. W., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 3229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the supplementary material of this article.