Abstract

The epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) family comprises four distinct members with similar framework characteristics: EGFR (HER1/ErbB1), ErbB2 (HER2/neu), ErbB3 (HER3), and ErbB4 (HER4). EGFR plays a pivotal role in cellular signaling pathways that regulate key pathological processes, including apoptosis, uncontrolled cell proliferation, metastasis, and angiogenesis. However, clinically used EGFRs such as apatinib, selumetinib, gefitinib, vandetanib, and erlotinib are not selective, thereby resulting in troublesome side effects. Drug obstruction, alteration, and specificity represent a few of the primary obstacles in the development of unique key compounds as EGFR inhibitors, stimulating medicinal chemists to discover innovative chemotypes. The development of drugs that block specific stages of cancerous cells, such as EGFR, is one of the main goals of many cancer treatments, including breast and lung tumors. Thus, the current study endeavored to summarize the numerous recent advancements (2016–2024) in the research and development of diverse epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitors, focusing on pyrrole, indole, pyrimidine, oxadiazole, isoxazole, and other structural classes. Preclinical, clinical, structure–activity relationships (SAR) with mechanism-based and in silico research, and other relevant data are compiled to offer directions for the scientific discovery of novel EGFR inhibitors with conceivable uses in therapy. The research trajectory of this entire field will provide incessant opportunities for the discovery of novel drug molecules with improved efficacy and selectivity.

The study summarizes the findings from the last eight years of research on heterocyclic core-based epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors. This provides an invaluable tool for oncology drug discovery.

1. Introduction

Cancer is the second leading cause of death in the U.S. and a global health problem.1,2 According to a recent survey, the American Cancer Society has predicted 611 720 cancer deaths to date, and 2 001 140 new cases are predicted to emerge by the end of 2024.3 Among the 234 580 new cases and 125 070 deaths expected, lung cancer remains the leading cause of deaths.4–7 The main cause of cancer fatalities is metastasis, the fast multiplication of aberrant cells that invade other organs.8–11 However, current medications are associated with many side effects and resistance, and thus, there is an urgent need to develop novel therapies with fewer side effects and improved efficacy.12–14

Cancer cells contain aberrant growth factors such as HER-2, EGFR, and VEGFR, which provide vital signals for cell proliferation and differentiation. These ligand-sensory receptors on the surface of malignant cells affect cellular activity and encourage irregular cell development.15–19 Epidermal growth factor activates EGFR (epidermal growth factor receptor), which codes for a transmembrane tyrosine kinase and is essential for tissue function. Mutations in growth factors often lead to carcinogenic activity. Exon 19 deletions and exon 21 L858R replacement are the main changes most commonly observed in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), and this mutation rate is highest in women, East Asians, and non-smokers. EGFR, which has tyrosine kinase activity, was discovered by Stanley Cohen in 1968. EGFR contains 1186 amino acid residues and extracellular ligand-binding, intracellular tyrosine kinase, and hydrophobic regions.20,21 ATP binding requires the hinge region, hydrophobic pockets 1 and 2, ribose pocket, and phosphate-binding pocket (P-loop) of the EGFR-TK cavity. The hinge region stabilizes ATP by hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic pockets secure the adenine ring, the ribose pocket holds the sugar, and the phosphate pocket binds the phosphate groups, allowing ATP interaction and kinase activity (Fig. 1).22–26

Fig. 1. Five key components involved in ATP binding within the EGFR-TK cavity.

2. EGFR receptor activation and cellular signaling pathways

An important member of the ErbB family, the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), uses ligand-binding and tyrosine kinase activation to control vital cellular processes including growth and differentiation.27–30 Gene expression and cell survival are impacted by activation, which sets off downstream signaling pathways such PI3K–AKT and Ras–MAPK.27,31–40 The epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) on the cell surface is ligand-dependent, and this contact causes the internal structure of the receptor to change and potentially increase the catalytic activity of the intrinsic tyrosine kinase, which is essential for cellular responses. Different ligands, including transforming growth factor-α and epidermal growth factor (EGF), activate EGFR, causing the receptor to dimerize, and then internalize when it binds. Subsequently, the intracellular tyrosine kinase domains of EGFR are autophosphorylated as a result.15,41–45 Following the recruitment of signal transducers such as Ras by activated EGFR, intracellular signaling pathways including the Akt and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and Ras–Raf mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways are triggered. These pathways control basic physiological processes that are essential for the development of malignancy, including gene expression, cell division, angiogenesis, and apoptosis inhibition. The activation of EGFR kinase results in the phosphorylation of the tyrosine residues such as RAS GTPase-activating protein (GAP), phospholipase C-y (PLC-y), mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) present on the cellular substrate. The overexpression of EGFR pathway-related genes leads to the motility, adhesion, and metastasis of tumor cells.46–50 This overexpression also helps to distinguish tumor cells from normal cells and makes them more susceptible to EGFR inhibitor drugs, which inhibit the growth and spread of tumor cells.51–60 The degradation of the triggered receptor/ligand combination takes place by lysosomal endocytosis or restoration back to the plasma membrane. These processes further regulate the various functions of EGFR such as angiogenesis, metastasis, apoptosis, and cell division.61–68 Furthermore, positive and negative feedback mechanisms impact downstream regulation, guaranteeing appropriate control of EGFR signaling (Fig. 2). Several medications are available in market, including almonertinib, brigatinib, neratinib, pyrotinib, and olmutinib are known to inhibit EGFR. Nevertheless, these medications are linked to both immediate and long-term adverse reactions, for example, diarrhea, dermatitis, xerosis (dry skin), onychomycosis (infection of fingernails or toenails), stomatitis (inflammation of the mouth) and anorexia.15

Fig. 2. Pathophysiology of EGFR activation.

3. Marketed drugs and heterocyclic molecules as EGFR inhibitors

First-generation EGFR inhibitors such as gefitinib and erlotinib target the ATP-binding site in NSCLC with specific mutations.5,10 T790M mutations enable resistance to their cell proliferation-blocking effects. Afatinib, canertinib, pelitinib, dacomitinib, and neratinib are durable second-generation EGFR inhibitors that target additional EGFR mutations and HER family members. Further, afatinib and dacomitinib are utilized to the treat first-generation inhibitor resistance in NSCLC and neratinib in HER2-positive breast cancer. Avitinib, olmutinib, and nazartinib are third-generation EGFR inhibitors that overcome resistance including the T790M mutation and improve NSCLC therapy.69–75 With ongoing safety and effectiveness research, these inhibitors show promise for treating cancer patients with EGFR mutations by selectively targeting sensitizing mutations and the T790M resistance mutation.76–82 Furthermore, the fourth-generation EGFR inhibitor BLU-945 targets resistance such as C797S mutation, bringing hope to patients who have advanced on earlier regimens (Fig. 3). Another novel chemical being researched owing to its safety and efficacy is TBQ-3804, which targets EGFR mutations resistant to current therapies. EGFR-targeted therapy such as DDC4002 may overcome resistance mechanisms and extend therapeutic options for EGFR-mutant cancers. The new compounds EA1045 and EA1001 address complex resistance mechanisms and provide more comprehensive EGFR-mutant cancer therapies, demonstrating targeted cancer medication evolution.10,83–87

Fig. 3. Various clinically available EGFR inhibitors containing different heterocyclic moieties.

In the past decade, several reviews based on heterocyclic compounds and medicinal chemistry opinions have been published. In 2021, Sharma et al. examined the various heterocyclic substances reported from 2016 to 2021 and their structure–activity relationship (SAR) as EGFR inhibitors.15 Compounds derived from natural sources or synthesized for medicinal purposes may exhibit anticancer properties by targeting EGFR.17,18,88 Structure–activity relationship studies on heterocyclic compounds are carried out by researchers to understand how specific structural elements contribute to their interaction with EGFR.89,90 This information is crucial for the rational design of new compounds with enhanced EGFR inhibitory properties. SAR research aids in the optimization of the chemical structure of heterocyclic compounds to realize improved efficacy and reduced side effects.91 Furan, pyrrole, oxadiazole, indole, thiophene, isoxazole, pyridine, and pyrimidine are heterocyclic compounds that have been studied in medicinal chemistry for their potential as EGFR inhibitors. These compounds can disrupt the EGFR signaling pathway, which is frequently dysregulated in cancer.92–101 Furan-based compounds have shown promise as EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors, while pyrrole derivatives also inhibit EGFR tyrosine kinase.92,102–104 Pyrimidine derivatives are critical in the development of EGFR inhibitors for use in cancer treatment.100 The role and impact of pyridine and isoxazole in EGFR inhibitors can differ depending on their molecular structure, substituents, and specific interactions with the EGFR protein.99–101 In medicinal chemistry, these heterocyclic rings are commonly used to fine-tune the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of drug candidates, aiming to improve their efficacy, selectivity, and bioavailability.90,91 To understand how these components contribute to the overall pharmacological profile of EGFR inhibitors, a detailed analysis of their structure–activity relationship (SAR) is required.102 Heterocyclic compounds possess anti-HIV, anti-diabetic, herbicidal activity, anti-cancer activity, insecticidal agents, anti-inflammatory, anti-bacterial, anti-oxidant, anti-convulsant, anti-allergic, and enzyme inhibitor properties.92,95–104 In addition to medications on the market, scientific endeavors worldwide have led to the development and expansion of new frameworks based on heterocyclic cores, which are now undergoing clinical studies (Table 1).105–115 A phase 1/2 (recruiting) study examined the efficacy of vebreltinib (also known as bozitinib, a pyridazine derivative) and PLB1004 in patients with locally progressed or metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and MET gene overexpression or amplification after EGFR-TKI failure. Nintedanib, an indole derivative, is in a non-recruiting phase 1/2 study with EGFR-TKI (gefitinib, erlotinib, and afatinib) for advanced NSCLC patients who have established resistance. EGF816 (3rd generation) and trametinib (MEK inhibitor) have completed a phase 1 trial in NSCLC patients with EGFR p.T790M mutations resistant to 1st or 2nd generation EGFR TKI treatment. JIN-A02, an oral fourth-generation EGFR-TKI medication, has been evaluated in advanced or metastatic (NSCLC) patients with EGFR mutation-positive (C797S or T790M) in a phase 1/2 (recruiting) open-label, multicenter study for safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and antitumor effect. The irreversible blocker osimertinib, an analog of aniline pyridine, functions by generating a covalent connection with C797. Treatment of advanced EGFR-mutant lung cancer with osimertinib (Tagrisso) as first-line therapy is being investigated in a phase II study (recruiting). This drug is now under phase 2 (active, non-recruiting) studies in subjects with EGFR-mutated NSCLC patients who have brain or leptomeningeal metastases. A phase 2 trial study (active, not recruiting) of osimertinib plus abemaciclib for NSCLC patients with EGFR activating mutations (Exon 21 L858R, Exon 19 deletion, Exon 18 G719X, and Exon 21 L861Q) and osimertinib resistance. The effectiveness of combining VIC-1911 (AKIs) with osimertinib for the treatment of advanced NSCLC in patients with EGFR mutation is being assessed in a phase I clinical study (recruiting). Phase 2 studies (not yet recruiting) of osimertinib and aspirin neoadjuvant therapy for resectable, EGFR-mutated NSCLC is underway. Primary IIA–IIIA EGFR-sensitive mutation patients receiving osimertinib neoadjuvant therapy have been targeted. The third-generation EGFR TK inhibitor furmonertinib inhibits ABCB1 and ABCG2 in cancer cells, overcoming multidrug resistance. It is presently being studied in a phase 2 study (which is not yet enrolling patients) for NSCLC patients with EGFR expression and prospective. Advanced NSCLC patients with EGFR mutation are being recruited for a phase 1/2 clinical study to evaluate the safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and antitumor efficacy of IN10018 in combination with the third-generation EGFR-TKI (furmonertinib). In phase 2 (recruiting) investigations, furmonertinib in combination with radiotherapy is now being studied for NSCLC with oligoprogression after first-line EGFR-TKI. Adults with glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) expressing EGFR alterations (phase 1 only) or advanced/metastatic NSCLC with non-classical or inherited EGFR resistance (EGFR C797S) mutations and/or without CNS disease are enrolled in the BDTX-1535 drug study (recruiting). Another irreversible EGFR-TKI (lazertinib) has nanomolar biological activity and authorized for 2nd-line T790M mutation-positive NSCLC that failed 1st or 2nd generation EGFR TKI with a pyrimidine scaffold. The recommended dosage is 240 mg. Based on the promising results of this trial with an increased dose; a study evaluated the safety and effectiveness of 160 mg lazertinib. A phase 2 study (not yet recruiting) using 160 mg lazertinib daily in EGFR T790M mutant NSCLC patients is ongoing. Trials in combination with platinum-based chemotherapy as the second-line treatment for patients with locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC with an EGFR mutation (T790M) were completed. Phase 2 (recruiting) trials are presently being conducted to evaluate the safety and efficacy of bevacizumab with ametinib as the first line of therapy for non-oligometastatic advanced NSCLC with EGFR mutations.115

Table 1. Novel experimental heterocyclic drugs in clinical researcha.

| Study title | Interventions/phase | Conditions/molecular alterations | Structures | NCT identifier | Sponsor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A phase Ib/II study of vebreltinib plus PLB1004 in EGFR-mutated, advanced NSCLC with MET amplification or MET overexpression following EGFR-TKI | Vebreltinib + PLB1004 (phase 1/2) | Non-small cell lung cancer (EGFR-mutated + MET overexpression) |

|

NCT06343064 | Avistone Biotechnology Co., Ltd. |

| A phase I/phase II study of nintedanib plus EGFR TKI in EGFR-mutated non-small cell lung cancer patients | Nintedanib + gefitinib + erlotinib + afatinib (phase 1/2) | Non-small cell lung cancer (EGFR gene mutation + EGFR-TKI-resistant mutation) |

|

NCT06071013 | China Medical University Hospital |

| EGF816 and trametinib in patients with non-small cell lung cancer harboring activating EGFR mutations (EATON) | EGF816 + Trametinib (phase 1) | Non-small cell lung cancer (bronchial neoplasms + harboring activating EGFR mutations) |

|

NCT03516214 | University of Cologne |

| A phase 1/2 study to evaluate the safety, tolerability and PK of JIN-A02 in patients with EGFR mutant advanced NSCLC | JIN-A02 (phase 1/2) | Non-small cell lung cancer (harboring EGFR-mutation of C797S or T790M) | — | NCT05394831 | J Ints Bio |

| Osimertinib and abemaciclib in EGFR mutant non-small cell lung cancer after osimertinib resistance | Abemaciclib + osimertinib (phase 2) | Non-small cell lung cancer (EGFR activating mutations + osimertinib resistance) |

|

NCT04545710 | University of California, San Diego |

| IN10018 combination therapy in advanced EGFR mutation-positive NSCLC | IN10018 + furmonertinib (phase 1/2) | Advanced EGFR mutation-positive NSCLC |

|

NCT05994131 | InxMed (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. |

| Phase 1/2 study of BDTX-1535 in patients with glioblastoma or non-small cell lung cancer with EGFR mutations | BDTX-1535 (phase 1/2) | Glioblastoma or non-small cell lung cancer (EGFR mutations) |

|

NCT05256290 | Black Diamond Therapeutics, Inc. |

| Lazertinib 160 mg in EGFR T790M NSCLC | Lazertinib (phase 2) | EGFR T790M mutant non-small cell lung cancer |

|

NCT05701384 | Samsung Medical Center |

| Osimertinib combined with aspirin neoadjuvant therapy for resectable EGFR mutated NSCLC patients | Osimertinib + aspirin (phase 2) | Non-small cell lung cancer (EGFR gene mutation) |

|

NCT06018688 | Daping Hospital and the Research Institute of Surgery of the Third Military Medical University |

| Study of osimertinib in patients with a lung cancer with brain or leptomeningeal metastases with EGFR mutation (ORBITAL) | Osimertinib (phase 2) | Non-small cell lung cancer (EGFR-mutated with brain or leptomeningeal metastases) |

|

NCT04233021 | Intergroupe Francophone de Cancerologie Thoracique |

| Study of furmonertinib as neoadjuvant therapy for resectable stage II–IIIB EGFR sensitive mutant NSCLC | Furmonertinib (phase 2) | Non-small cell lung cancer (stage II–IIIB EGFR sensitive mutant) |

|

NCT05987826 | Shanghai Zhongshan Hospital |

| Retrospective, external comparator study of lazertinib as the 2nd-line treatment in patients with EGFR mutation + NSCLC | Lazertinib + platinum-based chemotherapy | EGFR mutation + locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC |

|

NCT05862194 | Yuhan Corporation |

| Osimertinib in EGFR mutant lung cancer | Osimertinib (phase 2) | Advanced EGFR mutant lung cancer |

|

NCT03586453 | Dana-Farber Cancer Institute |

| A study of furmonertinib combined with radiotherapy for non-small cell lung cancer with oligoprogression | Furmonertinib (phase 2) | Non-small cell lung cancer with oligoprogression (after first-line EGFR-TKI therapy) |

|

NCT04970693 | Sun Yat-sen University |

| VIC-1911 combined with osimertinib for EGFR-mutant non-small cell lung cancer (VIC-1911) | VIC-1911 + osimertinib mesylate (phase 1) | Advanced non-small cell lung cancer (EGRF-mutation) |

|

NCT05489731 | Jiesi Yingda Pharmaceutical Technology (Suzhou) Co., Ltd. |

| Clinical study of ametinib combined with bevacizumab in first-line treatment of advanced NSCLC with EGFR-mutations | Ametinib + bevacizumab (phase 2) | Non-oligometastatic advanced NSCLC (EGFR-mutations) | — | NCT05754736 | The Second Affiliated Hospital of Shandong First Medical University |

Source: https://clinicaltrials.gov./.

Recently, some researchers have attempted to highlight the signaling pathway or mechanism and related EGFR blockers that are undergoing clinical trials or have been identified based on in silico mechanisms.15 Together with the earlier research, we attempt to characterize the impact of different heterocyclic congeners on EGFR signaling in cancer. In addition, we cover in depth the SAR of different scaffolds with anticancer activities and their in silico investigations. In this review, we compile the progress in the last nine years in heterocyclic scaffolds as EGFR inhibitors (2016–2024). This review focuses on four major aspects, as follows: 1) latest cancer statistics, 2) EGFR mutations, different generations of EGFR inhibitors, and their limitations on various mutations, 3) the basic pharmacophore of EGFR inhibitors and the development strategies used by various researchers, and 4) elaborate discussion of heterocyclic scaffolds as EGFR inhibitors, their biological activity, designing strategies, and structure–activity relationship. We expect that this brief review will be useful to medicinal or organic scientists discovering medications and their development, as well as oncologists studying them as valuable resources.

4. Advancements in the field of medicinal chemistry pertaining to EGFR inhibitors

4.1. Pyrrole-based EGFR inhibitors

Pyrrole contains a five-membered ring made up of nitrogen atoms, which has been employed as a building block to create chemicals that target EGFR. Zhou et al. designed a variety of osimertinib analogs (1, Fig. 4) for the human lung cancer cell lines NCI-H19751 (L858R/T790M EGFR) and A431 (WT-EGFR). The IC50 values for compounds 1p, 1a, 1m, 1d, 1j, and 1g and the standard osimertinib were 13.2 nM, 15.1 nM, 19.5 nM, 22.3 nM, 44.1 nM, 73.5 nM, and 14.3 nM, respectively (WT/mutant). Congeners 1m and 1d showed selective action in NCI-H1975-resistant cells, and also exhibited greater kinase and cellular inhibitory action towards L858R/T790M EGFR then WT-EGFR. Furthermore, congener 1p, similar to osimertinib, selectively suppressed mutant EFGR phosphorylation and downstream signaling. Finally, the structure–activity relationship studies revealed that the congener containing the pyrrole–pyridine moieties exhibited excellent activity.116

Fig. 4. Design and SAR of pyrimidine-attached pyrrole–pyridine and other heterocyclic rings as EGFR inhibitors.

Thiriveedhi et al. explored a series of fused pyrrole analogues (2, Fig. 5) as major anti-proliferative agents in a murine melanoma cell line (B16F10) and breast cancer cell line (MCF-7) via the MTT assay. The anti-cancer potency of congeners 2f (IC50 values of 13.97 μM and 18.92 μM) and 2m (IC50 values of 13.25 μM and 18.37 μM) was highest for both cell lines, while 2c (IC50 values of 19.65 μM and 23.69 μM) was the second best, respectively. Furthermore, the cytotoxicity of the triazole series of congeners (2a, 2c, 2e, 2f, 2h, 2i, and 2m) was found to be promising with an IC50 value of 120.1 μM, 159.8 μM, 145.9 μM, 106.0 μM, 110.2 μM, 147.7 μM, and 152.9 μM, respectively, for a normal cell line. Moreover, molecular docking investigations also revealed a binding relationship between pyrimidine and pyrrole nuclei. Finally, structural studies demonstrated that substituting an electron-withdrawing group and a polar group on a triazole with a heterocyclic ring strengthened its anti-cancer activity.117

Fig. 5. Design and SAR of pyrrole clubbed pyrimidine derivatives bearing a triazole ring towards EGFR.

Fawzy et al. reported the synthesis of pyrrole-based scaffolds (3, Fig. 6) and assessed their activity as EGFR kinase inhibitors. The performances of these scaffolds were measured using the MTT assay on three different human cancer cells including pancreatic cancer cells (Panc-1), breast cancer cells (MCF-7), and colon cancer cells. All the synthetic congeners showed a cell viability score of more than an 85% and no cytotoxicity. Additionally, congeners 3a, 3b, and 3c displayed IC50 values of 20 μM, 23 μM, and 23 μM against the MCF-7 cell line, respectively. Doxorubicin was used as a reference drug (IC50 value: 13 μM). Moreover, congener 3a resulted in cell cycle arrest in the pre-G1 and G2/M phases. The apoptotic cell percentage in the pre-G1 phase increased by up to 1.93% with reference to doxorubicin, which causes cell cycle arrest at the G0/G1 phase. Based on the molecular docking analysis, congeners 3a, 3b, and 3c displayed binding energy scores of −8.06 kcal mol−1, −7.96 kcal mol−1, and −6.09 kcal mol−1, respectively, compared to their positive control doxorubicin, whose binding energy score was −6.63 kcal mol−1.118

Fig. 6. Design and SAR of pyrrole derivatives containing a chromone ring as EGFR inhibitors.

Kurup et al. carried out a study on 7H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidin-4-amines (4, Fig. 7) as dual Aurora kinase A and EGFR kinase inhibitors against the FADU, BHY, SAS, and CAL cell lines. Hybrids 4a, 4b, 4c, 4d, and 4e showed single-digit nanomolar EGFR inhibition, whereas compounds 4a, 4d, and 4e showed 140-times more effective inhibition than the reference staurosporin (IC50 values of 3.76 ± 0.12 nM, 3.63 ± 0.43 nM, 6.63 ± 0.98 nM, and 430.57 ± 25.44 nM), respectively. During cell cycle analysis, it was found that hybrid 4b provided a route to cycle arrest in the G2/M phase, resulting in cell death. Moreover, hybrid 4b signified the most exclusive EGFR and AURKA inhibition performance together with anti-proliferative effects and enzyme inhibition assays, in contrast to the four SCCHN cell lines. Further, the congener containing a 4-anilino ring with an electron-removing group showed higher inhibition than the other substituents. Furthermore, the docking analysis of the hybrids revealed that this motif assisted both inhibitors but improved the ATP-binding interaction.119

Fig. 7. Design and SAR of recently proposed pyrrole-pyrimidine analogs as significant EGFR inhibitors.

Belal et al. developed a series of fused 1-hydroxypyrroles[3,2-d]pyrrolo[3,2-e] and pyrimidines[1,4]diazepine congeners (5, Fig. 8) as strong inhibitors of EGFR and CDK2. In this series, all the tested analogs showed potent anti-proliferative activity (IC50 range: 0.009–2.195 mM) against three cancer cell lines; notably, analog 5ab exhibited the highest cytotoxic activity with IC50 values of 0.011 mM (HCT116), 0.043 mM (MCF-7), and 0.049 mM (Hep3B). Analog 5ab displayed superior CDK2 inhibition (15%) but lower EGFR inhibition (70%) compared to imatinib (2%). Additionally, the kinase profile assessment of analog 5ab demonstrated its inhibitory efficacy against three different types of kinases, GSK3 alpha, DYRK3, and CDK2/CyclinA1. Further, analog 5ab occupied the active sites and interacted with important amino acids according to the docking evaluation between DYRK3/GSK3 and analog 5ab (binding energy: 24.54 kcal mol−1 for DYRK3 and 16.85 kcal mol−1 for GSK3). The co-crystallized ligands with binding free energies of 16.41 kcal mol−1 and 20.80 kcal mol−1 were DYRK3: HRM and GSK3: 65A, respectively. In the SAR studies, substitution with a 2-(piperidine-1yl)acetamido moiety (analog 5aa–c) enhanced the cytotoxicity, with 5ab being the most active against the three cell lines. Among pyrrolo[3,2-d]pyrimidine 5ba–c, 5bc was found to be the most active against HCT116. Also, this study highlighted the significance of a single methyl group in the most active analogs 5ab and 5bc.120

Fig. 8. Design and SAR of newly introduced pyrrole–pyrimidine analogs as significant EGFR inhibitors.

In the study by Abdelbaset et al., they reported that pyrrol-2(3H)-one congeners (6, Fig. 9) showed the maximum anti-proliferative activity compared to the pyridazone congener against 8 human cancer types, including leukemia, non-small lung cancer, colon cancer, CNS cancer, melanoma cancer, ovarian cancer, renal and breast cancer cell lines. Congeners 6a and 6b showed excellent activity against EGFR, BRAF and tubulin inhibition (IC50 value of 12.5 ± 1.9 μM, 10.6 ± 1.8 μM, and 3.4 ± 2.0 μM and 1.9 ± 0.7 μM, 1635 ± 2488 μM, and 988 ± 160 μM) compared to erlotinib (BRAF and EGFR) with IC50 values 0.05 ± 0.03 μM and 0.06 ± 0.03 μM, and docetaxel and vincristine for tubulin effect exhibited IC50 values of 805 ± 227 μM and 4625 ± 290 μM as the standard drugs, respectively. According to results of the cell cycle arrest studies, the most active compounds induced cell cycle arrest in the G2/M phase and apoptosis in the Pre-G1 phase in the PaCa2 and HT-29 cell lines. Moreover, the molecular docking studies revealed that congener 6b was involved in H-bond interaction with CASN101 and carbonyl with another H-bond. Congener 6a formed π–σ interaction, π–sulfur interaction, and other hydrophobic interactions. Finally, the structural analysis depicted that the introduction of a 2-methylthio or 2-methoxy motif with quinoline enhanced the activity, whereas the introduction of the 2-hydroxy motif decreased the activity. Substitution of pyridazinones and quinolinyl-pyrrolones exerted exclusive BRAF inhibition instead of EGFR inhibition.121

Fig. 9. Design and SAR of recently reported pyrrolone/pyridazinone with an attached quinolinyl ring as potential EGFR inhibitors.

Two years later, the same authors reported the development of pyrrolone derivatives (7, Fig. 10) as potential anti-proliferative agents against 60 different subpanel cancer cell lines. Among them, compounds 7a, 7b, and 7c displayed a wide percentage growth inhibitory activity range, among which compound 7c exerted potent anti-tumor action against 9 subpanels with GI50 levels of 0.21 μM and 3.77 μM (selectivity ratio). Additionally, the cell viability study showed that compounds 7a, 7b and 7c exhibited greater than 87% viability according to the MTT assay at 50 μM with no cytotoxic effect. Moreover, the results from the EGFR-TK assay demonstrated that compounds 7a, 7b and 7c exerted low BRAFV600E and tubulin polymerization inhibition with IC50 values for EGFR of 9.4 ± 3.1 μM, 7.4 ± 1.2 μM, and 9.2 ± 3.5 μM, respectively, and BRAFV600E of 12.6 μM, which resulted in cell aggregation and cell arrest at the G2/M phase and pre-G1 apoptosis. Furthermore, the docking analysis highlighted higher binding affinities of the congeners (ΔGb = −12.49 to −12.99 kcal mol−1) towards tubulin CA-4 (8.87 kcal mol−1). The binding modes occur mainly through hydrophobic interaction. Interestingly, the structural activity revealed that the compounds containing N-phenethyl-1H-pyrrol-2(3H)-one were more potent than that bearing N-benzyl-1H-pyrrol-2(3H)-one.122

Fig. 10. Design and SAR of newly developed pyrrolone compounds carrying different heterocyclic rings as potent EGFR inhibitors.

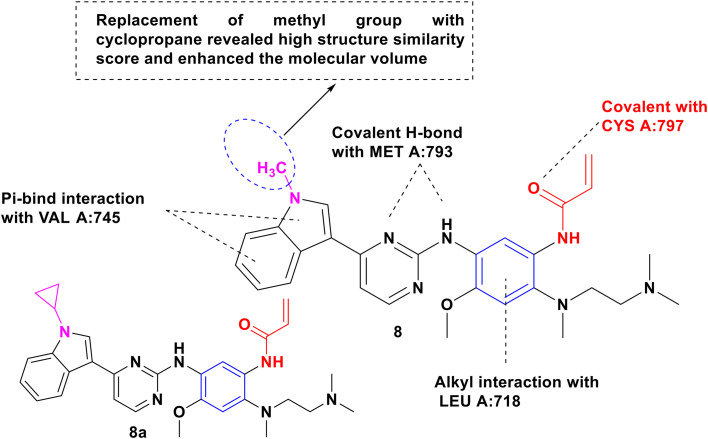

In a combinatorial study of 2D similarity, potential binding, affinities, modes, and interactions in EGFR, Almalki et al. compared the activity of pyrrole-based almonertinib with icotinib and olmutinib (8, Fig. 11). The EGFR mutants (NSCLC) L858R, L861Q, and T790M were more susceptible to icotinib, resulting in 91%, 99%, 96%, 61%, and 61% growth inhibition, respectively. Almonertinib treatment was aggressive against EGFR-T790M, T790M/L858R, T790M/Del19, and EGFR-WT mutant-positive NSCLC with IC50 values of 0.37 nM, 0.29 nM, 0.21 nM, and 3.39 nM, whereas olmutinib was reported against EGFR T790M/L858R with an IC50 value of 0.01 μM. The 2D similarity search among three revealed the highest scores (MCS Tanimoto) for icotinib (0.9333), osimertinib (0.8421), and almonertinib (0.9487) with WZ4003 against a database of 154 EGFR derived from PDB. Further, the docking results among them indicated that the binding free energy (ΔGb = −703 to −8.07 kcal mol−1) of up to 10 times was superimposed on the ligand and possessed equivalent interaction. Furthermore, the structural analysis highlighted that the β-carbon in the Michael acceptor site and the distance between the thiol groups in Cys797 in EGFR were resolved in olmutinib and almonertinib (4.087 and 4.765, respectively).123

Fig. 11. Design and SAR of recently proposed pyrrole-based almonertinib with icotinib and olmutinib as potent EGFR inhibitors.

Reiersolmoen et al. synthesized a library of 5-aryl-7H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine-4-amine analogs (9, Fig. 12). The synthesized scaffolds were investigated for EGFR kinase inhibition at a test concentration of 100 nM. The scaffolds containing the phenyl-substituted parent compound displayed 75% inhibition towards EGFR kinase. All the 5-aryl substituted analogs showed 89–93% inhibition and the maximum activity was depicted by the (S)-phenyl glycinol analogs (9a, 9b, 9c and 9d). As a result of its anti-proliferative activity, congener 9b (3-hydroxy derivative) was more influential than the commercial drug erlotinib with an IC50 value 0.9 nM and 0.5 nM, respectively. Moreover, 9b and 9c with IC50 values 112 nM and 104 nM, respectively, were more active than the standard (IC50 value of 95 nM) and hybrid 9d was also showed high cell viability.124

Fig. 12. Design and SAR of the newest pyrrole–pyrimidine derivatives towards EGFR.

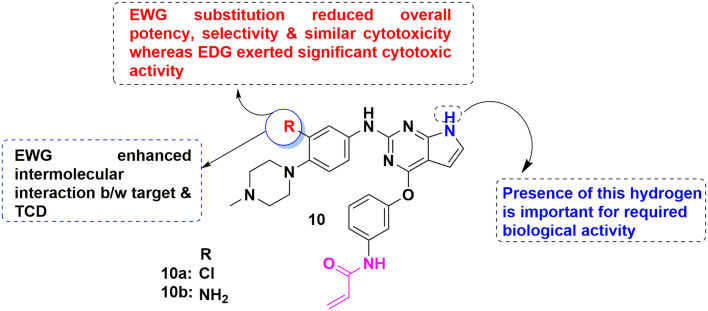

Xia et al. discussed a series of pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine congeners (10, Fig. 13). The in vitro cytotoxic study using the CCK8 method against NSCLC model cell lines including lung adenocarcinoma cell line (LUAD), with exclusive EGFR: NCI-H460 bearing EGFRWT, NCI-H1975 with EGFRL858R/T790M, HCC827 bearing EGFRdel E746-A750 mutations, one large cell lung cancer (LCLC) cell line and A549 harboring EGFRWT cell line revealed that congener 10b was more efficient (IC50 value of 0.046 μM) towards HCC827 and 10a had greater activity towards A549 and H1975 (IC50 value of 1.68 and 1.67 μM), respectively. Additionally, the cellular and proliferative activity highlighted that congener 10b showed strong kinase inhibitory activity against EGFRT790 and EGFRdel E746-A750 with IC50 values of 0.21 nM and 2.2 nM, respectively. Further, the cell cycle studies highlighted that apoptosis occurred in the NSCLC cell lines and blockade in the G0/G1 phase. Furthermore, docking simulation showed that molecular orientation and critical intermolecular interaction. Finally, structural scrutiny of anti-NSCLC TCD signified that the protection group (POM) reduced the overall activity, whereas amino groups at R1 enhanced the anti-proliferative activity.125

Fig. 13. Design and SAR of recently reported pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine congeners against EGFR.

Han et al. reported their efforts in investigating 6-aryl-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine-4-amine as an EGFR inhibitor (11, Fig. 14) against the PC-9, A-549, AU-565, C-33A, CAL-27, FaDu, K-562, and BxPC3 cancer cell lines. Analog 11a showed high activity against these cell lines (PC-9, A-549, AU-565, C-33A, CAL-27, FaDu, K-562, and BxPC3) with IC50 values of <0.1, >100, 2.5 ± 0.4, 0.7 ± 0.0, 2.7 ± 0.6, >33, 15 ± 2, and 15 ± 1 μM compared to erlotinib (IC50 value <0.1, >100, 3.3 ± 0.6, 0.9 ± 0.0, 1.3 ± 0.6, >11, 55 ± 9, and 1.9 ± 0.2 μM), respectively. Additionally, the cell proliferation study using F3/Ba-EGFRL8F8R stable cells and A-431 and PC9 cells showed that analog 11a had higher potential in diseases related to EGFR. Further, the docking study indicated that the binding affinity of the hydrophilic molecule to the Gln791, Thr 790 and Thr854 amino acid residues is to pyrrole and pyrimidine N-1. Final analysis of the structure–activity relationship demonstrated that the attachment of 6-aryl at position 4 of fragment B increased the potency as an EGFR inhibitor and the introduction of hydroxylethyl and methyl in fragment B resulted in higher activity.126

Fig. 14. Design and SAR of 6-aryl-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine-4-amine against EGFR.

4.2. Indole-based EGFR inhibitors

Indole, also known as benzo[b]pyrrole, is established by the fusion of six-membered benzene with five-membered pyrrole moiety. A library of 2,3-dihydropyrazino[1,2-a]indole-1,4-dione series was synthesized by Wahaibi et al. The developed hybrids (12, Fig. 15) were assessed for their anti-proliferative activity towards pancreas (Panc-1), breast cancer (MCF-7), colon cancer (HT-29) and epithelial cancer (A-549) cell lines. Among the series, congener 12d was found to be the most remarkable with the mean GI50 value of 1.07 μM towards all four cell lines compared to the standard doxorubicin (GI50 = 1.13 μM). Also, congeners 12a–i displayed promising anti-proliferative activity with IC50 values in the range of 0.08–0.46 μM. These hybrids were further tested for their EGFR and BRAFV600E kinase activity, among which congener 12d and 12i exhibited equal potency with IC50 values of 0.08 μM, 0.09 μM and 0.1 μM, 0.29 μM, respectively. Additionally, the results of the cell cycle and apoptosis study displayed that hybrids 12d and 12i caused apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in both the Pre-G1 and G2/M phases against the MCF-7 cell line. Furthermore, the molecular docking score highlighted that congener 12d revealed the highest binding free energy of −11.57 kcal mol−1 with a similar hydrophobic interaction and hydrogen bonding interaction with Cys532 and Met796 in BRAFV600E and EGFR. Finally, according to the SAR, it was concluded that substitution with an electron-withdrawing group at position 8 of the congeners decreased the potency (1.7 fold) and swapping of the phenethyl tail at the para position enhanced their anti-proliferative activity.127

Fig. 15. Design and SAR of innovative 2,3-dihydropyrazino[1,2-a]indole-1,4-dione series as EGFR inhibitors.

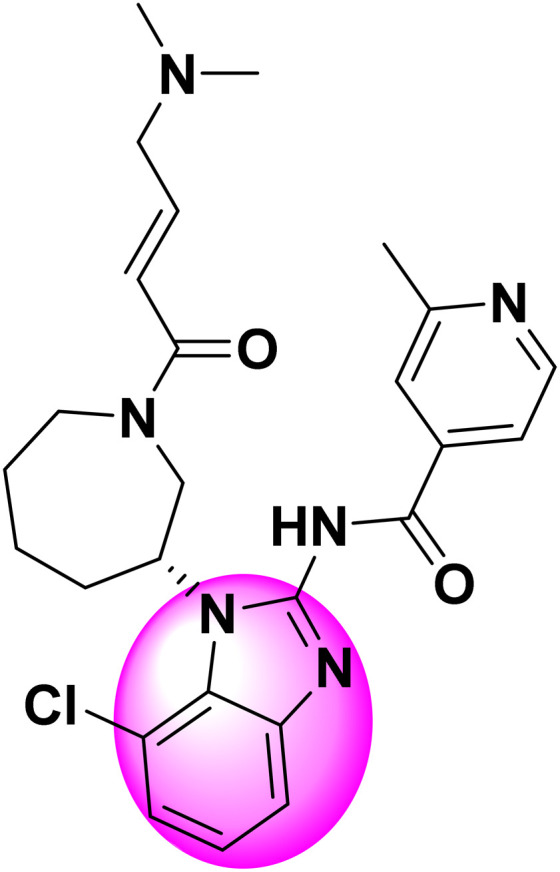

Singh et al. reported the synthesis of a series of indole-based hybrids (13, Fig. 16) and assessed their activity as dual EGFR (T790M) and c-Met inhibitors. Hybrids 13a, 13b and 13c exerted excellent inhibitory activity against EGFR (T790M) and EGFR (L858R) and c-Met kinase with IC50 values of 0.913 μM and 0.094 μM, 0.097 μM and 0.099 μM, 0.595 μM and 0.518 μM, respectively. Further, the simulation study revealed that all the hybrids exhibited a hydrophobic interaction in the hinge region amino acids. Additionally, the docking study results depicted that all the hybrids exerted an excellent docking score in the range of −8.22 to −6.98 kcal mol−1 with EGFR and −7.42 to −4.59 kcal mol−1 with c-Met in a period of 30 ns. Furthermore, the binding energy of the molecules was found to be in the range of −75.706 to −49.003 in EGFR (T790M) and the addition of bromine with a side chain maximized the van der Waals and hydrophobic interactions. Finally, the structure–activity relationship disclosed that ethyl and isopropyl substitution at the para-position enhanced the activity towards EGFR and 3-chloro substitution enhanced the activity towards c-Met.128

Fig. 16. Design and SAR of a series of indole-based hybrids as dual EGFR and c-Met inhibitors.

Indole Schiff base analogs (14, Fig. 17) were designed by Trivedi et al. The anticipated analogs were assessed for their in vitro cytotoxic activity against the A549 (human lung cancer) cell line using the MTT assay. Analogs 14a–f were assessed, among which 14b showed promising inhibitory activity compared to osimertinib. Further, docking analysis of all the anticipated analogs divulged that analogs 14a, 14c, and 14b showed tremendous binding affinities to EGFR-TK with docking scores of −5.98, −5.82 and −5.46, respectively. Furthermore, the binding interaction of analogs 14a and 14c was shown to be a protein–ligand interaction with Met-793 by the formation of a hydrogen bond, which was similar to osimertinib (formed 1H-bond with Asn842 and 2H-bond with Met-793). Moreover, the 2D and 3D representations of analogs 14d showed its interaction with Glu762 and Lys728 by H-bonds. Finally, the structure–activity analysis highlighted that substitution with a heterocyclic R group resulted in the maximum activity compared to non-heterocyclic and substitution at position 3 of indole produced the most potent analog of the Schiff base derivatives.129

Fig. 17. Design and SAR of recently proposed indole Schiff base analogs as EGFR-TK inhibitors.

Eight series of quinazoline-fused 2,3-dihydroindole congeners (15, Fig. 18) were synthesized as anti-proliferative agents by Yang et al., among which congener 15c showed the highest anti-proliferative and cytotoxic activity against the PC-3, MCF-7 and A549 cell lines with IC50 values of 1.23 ± 0.09 μM, 1.34 ± 0.13 μM and 1.09 ± 0.04 μM compared to the EGFR inhibitor afatinib (IC50 value of 2.5 ± 0.18 μM, 0.93 ± 0.09 μM, and 0.71 ± 0.05 μM), respectively. Additionally, congeners 15a, 15b, and 15c showed activity as EGFR kinase inhibitors against EGFRWT and EGFRT790 with IC50 values of 3 nm, 4 nm, and 5 nm and 34 nm, 21 nm and 26 nm compared to afatinib (IC50 values of 5 nm and 7 nm), respectively. Compounds 15a and 15b also showed EGFR (WT and T790M) inhibitor activity with IC50 values of 3 nM and 4 nM and 34 nM and 21, nM respectively. Further, the apoptosis analysis demonstrated that congener 15c was more active than afatinib, inducing apoptosis in the A549 cells. Furthermore, the docking analysis depicted that congener 15c formed H-bond interaction with the LYS-949 and LEU-861 residues on the target site of EGFR. Finally, the structural analysis highlighted that the congener containing a secondary amine exerted favorable anti-proliferative activity.130

Fig. 18. Design and SAR of quinazoline-fused 2,3-dihydroindole congeners as EGFR inhibitors.

Youssif et al. reported a novel series of indole-2-carboximide and pyrazino[1,2-α]indole-1(2H)-ones as anti-cancer congeners (16, Fig. 19) and applied them as EGFR inhibitors and anti-proliferative agents against human cancer cell lines including MCF-7, A-547, PC-3, HT-29 and PaCa-2 using the MTT assay. Among them, congener 16c displayed the highest activity against the above-mentioned cell lines with IC50 values of 0.1 ± 0.08 μM, 0.9 ± 0.2 μM, 0.8 ± 0.5 μM, 0.6 ± 0.2 μM and 0.3 ± 0.2 μM compared to the standard erlotinib (IC50 values of 0.03 ± 0.01 μM, 0.04 ± 0.01 μM, 0.03 ± 0.01 μM, 0.02 ± 0.01 μM and 0.03 ± 0.02 μM), respectively. Additionally, the cell viability test indicated that all the congeners exerted 87% cell viability at 50 μM concentration. Further, the EGFR and BRAF study revealed that congeners 16a, 16b, and 16c acted as EGFR inhibitors with IC50 value in the range of 0.5–3.9 μM and that of BRAF-based congener 16c was 0.1 to 4.8 μM. Furthermore, the structure–activity analysis highlighted that substitution with trifluoromethyl on the phenyl ring resulted in the highest inhibitory action and substitution with methyl on the pyrrole ring and chloro on the aromatic group resulted in highly prominent anti-proliferative activity.131

Fig. 19. Design and SAR of recently introduced nindole-2-carboximide and pyrazino[1,2-α]indole-1(2H)-ones as EGFR inhibitors.

Sweidan et al. identified an array of new indole-2-carboximide analogues (17, Fig. 20) by computer-aided design. The identified analogues were screened on a panel of different cancer cell lines including breast cancer (MDA31), human colon carcinoma (HCT-116) and leukemia (K562) cell lines. In the above-mentioned array, screening of the analogues disclosed that synthetic 17 was the most activity EGFR inhibitor with IC50 values of 15 ± 1 μM, 19 ± 1 μM, and >100 μM, respectively. Secondary amines showed the highest anti-proliferative activity. The molecular docking results highlighted that the identified analogues perfectly fit the EGFR and PI3Kα kinase domain and favored the formation of an H-bond with the key binding residues. Moreover, a comparable binding affinity was found against protein kinase (HCT116 and MDA231). However, none of the congeners showed inhibitory action against K562. Finally, SAR defined that the combination of a hydroxyethyl motif with a phenyl motif at position 3 of the aromatic ring resulted in the compound with the highest activity.132

Fig. 20. Design and SAR of new indole-2-carboximide analogues as EGFR inhibitors.

Zhao et al. reported the synthesis and biological activity of AZD9291 congeners (18, Fig. 21) as selective and potent EGFRL858R/T790M inhibitors. According to the fluorescence staining experiments and cell cycle progression of congener 18c, it constrained H1975 cell proliferation at a concentration of 0.25 μM in a dose-dependent manner via apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in the G2/M phase. The selectivity and kinase inhibitory activity highlighted that among the designed congeners, 18a, 18b, and 18c showed the highest selectivity and significant inhibition against the EGFRL858R/T790M double mutant with the IC50 values for WT : TL of 65 μM : 6 μM, 387 μM : 16 μM, and 1531 μM : 8 μM in the H1975, A549, and HepG2 cell lines according to ELISA-based EGFR-TK compared to AZD9291 with an IC50 value for WT : TL of 16 μM : 8 μM, respectively. According to the inhibition and selectivity effect, congener 18c was found to be most active compound. Further investigation and the docking study displayed that the binding mode of 18b and 18c was along the 3H-bond and hinge Met-793 residue with the H-bond length of 2.5 and 2 Å, respectively. Finally, based on the SAR, it was concluded that substitution of EDG at the pyrimidine moiety increased the electron cloud density on it. Hence, the insertion of halogens at the ortho-position of acrylamide increased the activity, while the selectivity moderately decreased.133

Fig. 21. Design and SAR of AZD9291 congeners as selective and potent EGFRL858R/T790M inhibitors.

A library of EGFR L858R/T790M inhibitors (19, Fig. 22) was synthesized and designed by Zhang et al. based on modeling the binding mode of the commercial drug AZD9291 with mutant EGFR T790M. Among them, the most prominent inhibitor candidate 19a was found to be the most selective and efficient towards WT-EGFR, double L858R/T790M and single L858R with IC50 values of 21.6 nM, 2.6 nM and 6.0 nM compared to AZD9291 with IC50 values of 19.7 nM, 2.1 nM and 6.0 nM according to a FRET-based enzymatic inhibitory activity assay, respectively. Additionally, candidate 19a exhibited excellent pharmacokinetic activity of 52.4% bioavailability. Further, the anti-tumor efficacy of candidate 19a was investigated using a specific type of NSCLC xenograft model, which displayed excellent tumor growth inhibition at an oral dose of 20 mg kg−1 per day. Furthermore, the binding affinities towards the hERG ion channel were lower than that of AZD9291, which highlighted that candidate 19a may have less risk of causing cardio-related side effects. Finally, according to the SAR results, it was concluded that substitution at the para-position of the amino pyrimidine ring is a new strategy for achieving high EGFR T790M inhibition and selectivity.134

Fig. 22. Design and SAR of pyrimidine-based congeners with indole ring as selective and potent EGFR inhibitors.

Sever et al. described the anti-cancer in silico and in vitro analysis of indole-based 1,3,4-oxadiazole congeners (20, Fig. 23) as inhibitors of EGFR and COX-2. Evaluation of the in vitro cytotoxic effect of the congeners on the A375, NSCLC, A549, HCT116 and CRC cell lines revealed that candidate 20a demonstrated most prominent activity towards Jurkat cells and PBMCS with IC50 values of 6.45 ± 1.62 μM and 300 μM and selectivity index of >46.51 with reference to erlotinib with IC50 values of 9.47 ± 2.15 μM and 45.71 ± 8.88 μM and S.I of 14.83, respectively. Additionally, it induced apoptosis in the HCT116 cell line at a concentration of 10 μM. Moreover, the kinase study and COX-2 inhibition highlighted that candidate 20a exhibited high activity with IC50 values of 2.80 ± 0.52 μM, 73.5 ± 2.12 μM and 37.5 ± 3.5 μM. Further, candidate 20a is engaged in binding at the allosteric pocket in the active site of EGFR according to the molecular docking study and the simulation revealed that candidate 20a has a weak inhibitory effect on COX-2 and higher effect on EGFR. Finally, according to the SAR, it was concluded that the substitution of acetamide on 6-ethoxy benzothiazol-2-yl resulted in more relevant and efficient activity than erlotinib.135

Fig. 23. Design and SAR of recently introduced indole-based 1,3,4-oxadiazole congeners as dual inhibitors of EGFR and COX-2.

A novel series of fifteen 5-chloro-3-hydroxymethyl-indole-2-carboximide analogs (21, Fig. 24) was designed and synthesized as apoptotic and anti-proliferative agents by Mohamed et al. The biological evaluation via cell viability revealed that the maximum number of viable cells was recorded to be 86% at 50 μM in the MCF-7 cell line. Moreover, candidates 21a, 21b, 21c, and 21d were identified to be highly promising agents against four human cancer cell lines including Panc-1, MCF-7, A-549, and HT-29 (IC50 values of 0.18 ± 0.2 μM, 0.27 ± 0.10 μM, 0.12 ± 0.2 μM, and 0.22 ± 0.2 μM) compared to erlotinib with an IC50 value of 0.08 ± 0.04 μM, respectively. Additionally, the proteolytic caspase cascade activation studies demonstrated that congeners 21a and 21c markedly enhanced the levels of active caspase-8, caspase-9, and caspase-3, which activated both the extrinsic and intrinsic apoptosis pathways. Further, candidate 21c resulted in an increase and decrease in cells in the G2/M phase and G0/G phase, respectively, and induced apoptosis in the S-phase. Furthermore, a docking analysis was performed to assess their affinities and binding modes of interaction with EGFR. Finally, the structural analysis highlighted that the para-substituted phenethyl exerted more prominent anti-proliferative activity than the meta-substituted phenethyl.136

Fig. 24. Design and SAR studies of 5-chloro-3-hydroxymethyl-indole-2-carboximide analogs as inhibitors of EGFR.

A series of indole-based tyrphostin hybrids and their complexes (22, Fig. 25) were synthesized by Oberhuber et al. as anti-cancer agents. Hybrids 22a, 22b, and 22c in the series were found to be active against the HCT-116 (p53-negative), HCT-116wt, and MCF-7 cell lines, with IC50 values of 0.9 ± 0.2 μM, 3.0 ± 0.2 μM, 1.7 ± 0.2 μM, and 0.6 ± 0.1 μM, 0.4 ± 0.1 μM, and 2.6 ± 0.6 μM, respectively. Additionally, the biological evaluation of the anti-proliferative activity of hybrids 22a, 22b, and 22c was investigated in the EaHy.926 (endothelial/lung carcinoma), MCF-7Topo (breast carcinoma), 518A2 (melanoma), Huh-7 (hepatocellular carcinoma), FLO-1, and SK-GT-4 (esophageal adenocarcinoma cells) cancer cell lines with IC50 values of 1.3 ± 0.2, 0.18 ± 0.09, 1.4 ± 0.6, 0.04 ± 0.01, 1.2 ± 0.2, and >40 and 0.9 ± 0.1, 1.5 ± 0.1, 2.8 ± 0.3, 0, >40, and >40 μM and 1.9 ± 0.2, 0.10 ± 0.02, 0.6 ± 0.1, 0.01 ± 0.001, 2.5 ± 0.3, and >40 μM compared to sorafenib and gefitinib with IC50 values of 12.8 ± 0.2, 7.4 ± 0.4, 9.7 ± 2.1, and 0.9 ± 0.08 and 9.9 ± 2.9, 27.6 ± 2.4, 27.5 ± 1.6, and >50 μM, respectively. Moreover, the docking analysis highlighted that the favorable binding energy and distinct binding mode of hybrids 22a and 22b in EGFR and VEGFR-2 were −8.2, −7.7, and −9.5 kcal mol−1 with the amino acids MET769, GLU738, and ASP831, and ILE913, GLU915, and GLU915, respectively. Finally, the structure analysis of the hybrids revealed that swapping propyl and propargyl on the C3 position reduced the activity of the indole nitrogen; only an alkyl group on C1 and C2 exerted a positive effect. In comparison with the metal-free complexes, hybrid 22c enhanced the activity of the ligands.137

Fig. 25. Design and SAR of proposed indole-based tyrphostin hybrids and their complexes as inhibitors of EGFR.

Gomaa et al. developed a series of 2,3-dihydropyrazino[1,2-a]indole-1,4-dione congeners (23, Fig. 26) with potent antioxidant and anti-proliferative activity as dual inhibitors of EGFR and BRAFV600E against the HT-29 (colon cancer), Panc-1 (pancreas cancer), A549 (epithelial cancer), and MCF-7 (breast cancer) cancer cell lines. Among them, hybrid 23a displayed the highest efficacy, which was comparable to erlotinib (GI50 value of 33 nM) with a value of 35 nM against four cell lines. Additionally, the EGFR-TK test and BRAFV600E activity demonstrated that hybrids 23c, 23a, and 23b exhibited stronger inhibition towards BRAFV600E with IC50 values of 55 nM, 45 nM, and 51 nM compared to erlotinib (IC50 value of 80 nM), with hybrid 23a exerting 2.5-fold higher inhibition with an IC50 value of 32 nM in EGFR. Moreover, treatment with hybrid 23a caused MCF-7 cells to undergo enhanced programmed cell death and cell cycle arrest in the G2/M phase. Furthermore, the structure–activity data revealed that the hybrid with a flexible phenethyl side chain at position C2 and a ketonic group at position C4 performed the best. Finally, the docking study depicted the interaction of hybrid 23a with the ATP binding site of EGFR and mutant BRAFV600E, generating unique interactions with the amino acids.138

Fig. 26. Design and SAR of 2,3-dihydropyrazino[1,2-a]indole-1,4-dione congeners as dual inhibitors of EGFR and BRAFV600E.

4.3. Furan-based EGFR inhibitors

Furan is a captivating ring that has a distinctive backbone structure consisting of five-membered rings containing four carbons and one oxygen atom. Altowyan et al. used the [3 + 2] cycloaddition reaction to create a new series of congeners containing spirooxindoles derived from ethylene congeners combined with furan aryl components (24, Fig. 27). The biological test showed that the new chalcones with congener 24b showed high activity against MCF7 and HepG2 cells, with IC50 values of 4.1 ± 0.1 μM mL−1 and 3.5 ± 0.07 μM mL−1, respectively. These values were 2.92- and 4.3-times that of staurosporine. The developed congeners 24aa, 24ab, and 24ac showed effective antiproliferative activity with IC50 values of 4.30 ± 18, 10.7 ± 0.38, and 4.7 ± 0.18 μM mL−1, respectively. Additionally, the molecular docking study highlighted that the chemotherapeutic drug exhibited binding mechanisms and ligand–receptor interactions with congener 24b in EGFR and CDK proteins. Additionally, congener 24b possessed a monoclinic, supramolecular structure according to the crystal structure description and Hirshfeld calculation, showing a variety of intermolecular arrangements. Finally, the structure–activity relationship showed that the ethylene hybrids substituted with a furan motif had higher surface activity than the amino acids and substituted isatins.139

Fig. 27. Design and SAR studies of spirooxindoles derived from ethylene congeners combined with a furan ring as potent EGFR inhibitors.

Han et al. reported the synthesis of dual EGFR and CSFIR inhibitors of fused chiral 6-aryl-furo[2,3-d]pyridine-4 amine hybrids (25, Fig. 28). The cellular study of congeners 25a and 25b highlighted their target efficiency in a Ba/F3 cell line expressing EGFR with IC50 values of 196 nm and 217 nm compared to erlotinib (IC50 value of 87 nm) using the XTT assay. The kinase study of congeners 25a and 25b exhibited their off-target efficiency towards LYNB, CSF1R, YES, FGR, and ABL and lower activity towards HER4 and HER compared to erlotinib. Additionally, the molecular dynamics study demonstrated that hybrid 25a exhibited a higher docking score with N′,N′-dimethylethane-1,2-diamine (IC50 value of 0.4 nM) due to H-bonding and congener 25b exhibited binding with piperidine and morpholine with IC50 values of 0.6 nM and 1.1 nM, respectively. Finally, the SAR indicated that substitution at the amine part of fragment A and changing the 6-aryl group in fragment B influenced the potency of the congener. The ortho- and para-positions of the phenolic and furan congeners also displayed potential inhibitory activity.140

Fig. 28. Design and SAR of 6-aryl-furo[2,3-d]pyridine-4 amine hybrids as dual EGFR and CSFIR inhibitors.

Mphahlele et al. developed a library of benzo[c]furan-chalcone congeners (26, Fig. 29) and demonstrated their activity as anti-proliferative agents in a human breast cancer cell line (MCF-7). Among the congeners, 26a, 26b, and 26c showed higher cytotoxicity compared to the reference actinomycin D with IC50 values of 0.55, 22.78, 0.5 μM, and 37.2 μM, respectively. Additionally, the EGFR-TK phosphorylation study displayed that congener 26a exhibited the highest potency and inhibitory action towards EGFR, with an IC50 value of 50.17 μM. Further, the study of tubulin polymerization displayed the increased effect of congener 26d (IC50 = 101.885 μM). Furthermore, cell death evaluation by the annexin V-Cy3 SYTOX staining assay displayed a prominent collection of apoptotic cells after exposure to 1 μM congener 26a for 48 h, and exclusively cytotoxic congener 26a was found to induce apoptosis in MCF-7 cells. Moreover, the percentage cell viability for congeners 26a and 26d was 23% and 32.2%, respectively, and the docking study revealed that congeners 26d and 26e interact with the protein residues in the hydrophobic pocket, such as Arg 17, Val 702, Leu 694, and Leu 820, at the EGFR ATP binding site. Finally, it was concluded that substitution of 2 phenyl rings on 4-fluorophenyl, 4-trifluoromethoxyphenyl, and the benzofuran motif of the chalcone arm increased the toxicity to MCF-7 cells.141

Fig. 29. Design and SAR of a library of benzo[c]furan-chalcone congeners as EGFR inhibitors.

A collection of bromobenzofuran-oxadiazole analogs (27, Fig. 30) was designed to achieve and increase the synthesis of BTEAC as a phase transfer catalyst by Irfan et al. Analogs 27a–c was evaluated against the HepG2 cell line for six different cancer targets including EGFR, PI3K, mTOR, GSK-3β, AKT, and tubulin polymerization enzymes. Among the analogs, 27a, 27b, and 27c resulted in the lowest cell viability percentage of 12.72% ± 2.23%, 10.41% ± 0.66%, and 1.08% ± 1.08%, respectively. Additionally, the docking studies of congeners 27a, 27b, and 27c focused on the receptor targets of EGFR, mTOR, GSK-3β, AKT, and tubulin polymerization enzymes. Among them, congener 27b exhibited the highest efficiency against EGFR in vitro with the binding affinity of −15.17 kcal mol−1, and numerous interaction sites found such as ASP831, LEU694, PHE732, VAL702, LYS721, LEU820, ASP831, PHE832, CYS751, and C–H bond with CYS751 and PHE832 towards the active residue site. Moreover, the simulation findings revealed the binding free energies of 27b and 27a to MMGBSA and MPBSA, respectively. Finally, the structure–activity relationship study of the analogs demonstrated that substitution with electron-withdrawing groups (fluoro and chloro) on positions 4, 5, and 6 in the anilide ring of the phenyl group increased the cytotoxicity.142

Fig. 30. Design and SAR of a collection of bromobenzofuran-oxadiazole analogs as EGFR inhibitors.

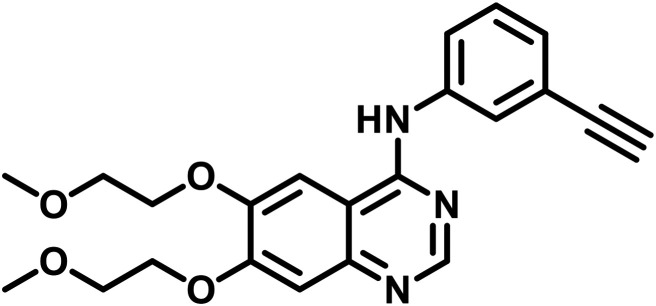

Lin et al. discovered pyrimidine-base furan scaffolds (28, Fig. 31) targeting EGFR with activity against NSCLC for anti-proliferative activity. The biological evaluation of EGFR and HER2 displayed that scaffold 28a showed higher activity towards EGFRA763/Y764 in FHEA, EGFRD770/N771 in NPG, and EGFRD770GY with IC50 values of 0.043, 0.133, and 0.033 nM compared to poziotinib (IC50 values of 0.0789, 0.082, and 0.218 nM), respectively. Additionally, studies of X-ray co-crystals revealed that EGFR crystals were present in analog 28a, resulting in the establishment of a covalent bond to the ATP binding site of Cys797 and contact with Leu844 and Val726 to create an H-bond with HRD, and DFG formed a hoop with EGFR. Further, the pharmacokinetic activity study of scaffold 28a showed its greater oral bioavailability (41.5%) and AUC (4-fold) than afatinib. Furthermore, the Western blotting analysis revealed that the dose-dependent minimization of phosphorylated EGFR in H1975 cells was consistent with the inhibition data. Moreover, scaffold 28a exhibited powerful inhibition against the mutant and WT-EGFR, as well as kinase with cysteine 797. The structure–activity relationship indicated that the introduction of acrylamide in the phenyl group of meta-position 5 of furanopyrimidine led to the formation of a scaffold with higher activity, as demonstrated by its cellular and enzymatic activity.143

Fig. 31. Design and SAR of recently developed pyrimidine-base furan scaffolds as EGFR inhibitors.

Hossam et al. described anilino-furo[2,3-d]pyrimidine hybrids (29, Fig. 32) as potent cancer agents against the A549 and MCF cell lines. Candidate 29a and its acidic derivative 29b exhibited high activity with IC50 values of 0.5 μM and 21.4 μM, with the EGFR inhibition activity of 18% and 100%, respectively. Additionally, the ADME results highlighted that a solvent with high polarity resulted in higher side chain enzyme inhibition. Moreover, the apoptotic activity demonstrated that synthetic hybrids 29a and 29b increased the number of annexin V-FITC-positive apoptotic cells for both late and early apoptosis in A549 cells. Further, the molecular modeling analysis showed that hybrids 29a and 29b induced crucial inhibitory activity via H-bonding with Thr854 and showed extra interaction with Phe856. Furthermore, the structure–activity analysis indicated that the introduction of a side chain in position 5 using acid scaffolds such as chloro and bromo aniline resulted in high EGFR inhibition activity.144

Fig. 32. Design and SAR of anilino-furo[2,3-d]pyrimidine hybrids as EGFR inhibitors.

Zhang et al. discovered indole-based furan hybrids (30, Fig. 33), specifically N-(furan-2-ylmethyl)-1H-indole-3-carboxamide derivatives 30, which are EGFR inhibitors that can be used to treat cancer. The in vitro cytotoxic activity of the derivatives was tested in five different cell lines including the Henrietta Lacks strain of cancer cells (HeLa), human lung adenocarcinoma cell line (A549), human liver normal cell line (HL7702), human colorectal cancer cell line (SW480), and human liver cancer cell line (HepG2). The MTT assay was used to determine the activity. Derivative 30a exhibited high activity with IC50 values of 5.33, 5.61, >100, 10.77, and >100 μM L, respectively. According to the molecular docking and binding study, derivative 30a forms H-bonds with GLY697, THR830, LEU768, GLN767, and ASP831, as well as hydrophobic interactions with ALA719, THR766, LYS721, VAL702, and LEU694. These results were used to design EGFR inhibitors. Finally, the structure–activity analysis highlighted that the substitution of 1-ethyl-N-(furan-2-ylmethyl)-5-{2-[2-(2-methoxyphenoxy)ethyl]amino}-2-oxoethoxy with {2-[2-(2-methoxyphenoxy)ethyl]-amino}-2-oxoethoxy in the C-5 position reduced the significant anti-cancer activity.145

Fig. 33. Design and SAR of recently proposed indole-based furan hybrids as EGFR inhibitors.

Zhang et al. integrated and innovated a sequence of quinazoline-based furan hybrids (31, Fig. 34) as antiproliferative agents against WT-EGFR with NCI-H1975, A549, A431 and SW480 cell lines in comparison to gefitinib (IC50 values of 12.70 ± 2.98 μM, 21.17 ± 0.47 μM, 4.45 ± 0.25 μM, and 12.50 ± 0.28 μM, respectively). Hybrids 31a, 31b, and 31c showed the highest activity with IC50 values of 3.01 ± 1.07 μM, 7.35 ± 1.42 μM, 3.64 ± 0.51 μM, and 5.58 ± 1.43 μM; 6.78 ± 1.98 μM, 5.49 ± 1.54 μM, 8.33 ± 1.29 μM; and 5.18 ± 0.99 μM, and 4.05 ± 0.67 μM, 1.28 ± 0.04 μM, 5.40 ± 0.08 μM, 14.97 ± 3.61 μM, respectively. Among them, hybrid 31a showed the greatest inhibitory activity. Additionally, the Western blotting study revealed that 31a inhibits EGFR, Erk1/2, and Akt at desirable concentrations. Moreover, the docking study indicated that hybrid 31a exhibited an indistinguishable mode of binding with minor variations in H-bond length, which defined its inhibitory action on EGFR.146

Fig. 34. Design and SAR studies of a sequence of quinazoline-based furan hybrids as EGFR inhibitors.

4.4. Oxadiazole-based EGFR inhibitors

Oxadiazoles, a class of organic compounds with a five-membered ring composed of one oxygen and two nitrogen atoms, show efficient binding interactions with the active site of EGFR. Unadkat et al. synthesized a novel series of 1,2,4-oxadiazole congeners (32, Fig. 35) and tested their activity against the HCT-116, MCF-7, HepG2, and A549 human cancer cell lines. Among the congeners, candidates 32a and 32b possessed the maximum inhibition activity against EGFR in the above-mentioned cell lines with IC50 in the range of 2–10 μM. Additionally, the docking simulation focused on the stable structure of the crystals with small deviations detected in the binding site. The protein was closely packed and stable at 30 ns. Moreover, the cytotoxicity studies demonstrated that the tested congeners showed <50% cell viability at a concentration of 10 μM on all the above-mentioned cell lines. Further, the molecular docking highlighted that congeners 32a and 32b showed stable interaction and formed a protein–ligand complex with docking scores of −15.09 and −16.05, respectively.147

Fig. 35. Design and SAR of a newly proposed sequence of 1,2,4-oxadiazoles synthetics as EGFR inhibitors.

Boraei et al. synthesized phthalazine-based derivatives with/without 1,3,4-oxadiazole (33, Fig. 36) and tested their in vivo and in vitro anti-proliferative activity against the HepG2 cell line. The in vitro analysis of derivatives 33a, 33b, 33c and 33d evinced their high activity with IC50 values of 15.8 μg mL−1, 13.6 μg mL−1, 7.09 μg mL−1, and 5.7 μg mL−1, and the in vivo analysis of derivatives 33b and 33c showed IC50 values of 7.25 μg mL−1 and 7.5 μg mL−1 with reference to doxorubicin (IC50 value of 4.0 μg mL−1) and cisplatin (IC50 value of 9.0 μg mL−1), respectively. Additionally, the molecular docking study highlighted that the most agile hybrids formed poor interaction with the active binding site via H-bonding specifically with Arg841. Moreover, the binding affinity of derivatives 33a, 33b, 33c and 33d was found to be −9.6, −8.6, −10.8 and −9.3 kcal mol−1. Finally, the structure–activity findings highlighted that the hybrid with substitution on the side chain suppressing bifurcated or bulky rings displayed a decrease in activity because of the steric effect on the residue within the cleft region, while a chain-length of 5–6 H-donor/acceptor atoms was optimal for efficient binding in the cleft region.148

Fig. 36. Design and SAR of emerged phthalazine-based derivatives with/without 1,3,4-oxadiazole as EGFR inhibitors.

El-Sayed et al. synthesized 1,3,4-oxadiazoles congeners (34, Fig. 37) as COX-2 and EGFR dual inhibitors and evaluated their activity as anticancer agents via an in silico cytotoxic and kinase study. The advanced selectivity delineated by congeners 34a, 34b, and 34c resulted in high cytotoxicity against the UO-31 renal cancer cell line with IC50 values of 5.75 nM, 8.6 nM, and 13.5 nM, respectively, with reference to doxorubicin (IC50 = 7.45 nM). Additionally, kinase inhibition emphasized that congener 34b (IC50 value of 500.275 nM) showed double the activity of the standard erlotinib (IC50 value of 500.4178 nM). Congeners 34a and 34c showed lower activity with IC50 values of 8.6 nM and 13.56 nM, respectively. Moreover, the docking simulation study indicated the different binding poses for congeners 34b, 34c, and 34a and their flipped orientation. Further, the pharmacokinetic study indicated that congeners 34a, 34b and 34c are prominent cytotoxic agents based on their drug-like properties. Furthermore, the SAR study highlighted that substitution with a pyridine ring at position 5 of 1,3,4-oxadiazoles boosted the anti-proliferative activity.149

Fig. 37. Design and SAR of explored 1,3,4-oxadiazole congeners as COX-2 and EGFR dual inhibitors.

Omar et al. established benzoxazole-based 1,3,4-oxadiazoleand triazolothiadiazine scaffolds (35, Fig. 38) and evaluated their anti-proliferative activity against the MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 human cancer cell lines. Hybrids 35a and 35b exhibited most the prominent activity against both cell lines with IC50 values of 1.76 ± 0.08 μM and 0.59 ± 0.02 μM and 0.21 ± 0.02 μM and 214.45 ± 8.61 μM, respectively. Additionally, the EGFR inhibitory assay of hybrids 35a and 35b showed IC50 values of 129.77 ± 2.7 μM and 236.49 ± 4.02 μM, respectively, indicating that they were more selective EGFR inhibitors compared to erlotinib (IC50 value of 111.15 ± 1.61 μM). Further study of hybrids 35a and 35b showed that they showed caspase-9 activation and high annexin-V binding affinity and the cell cycle analysis demonstrated increased apoptosis in the Pre-G1 phase and cell cycle arrest in the G2/M phase. Furthermore, the docking analysis divulged that hybrids 35a and 35b interacted with the inactive EGFR in a specific orientation in the DFG-Asp motif in and out of the αC-helix. Hybrid 35b interacted and activated the ARO enzyme and superimposed with the ASD-ARO co-crystallized ligand. Finally, the structural examination revealed that hybrids 35a and 35b shared a common pharmacophore containing a sulfonyl group with the 1,3,4-oxadiazole moiety substituted with a benzoxazole ring and combined with a diatomic spacer showed the most promising activity.150

Fig. 38. Design and SAR of benzoxazole-based 1,3,4-oxadiazoleand triazolothiadiazine scaffolds as EGFR inhibitors.

Strzelecka et al. reported the synthesis and investigation of the antitumor potential of innovative N-Mannich bases of 1,3,4-oxadiazole employing 4,6-dimethyl pyridine frameworks (36, Fig. 39). The cytotoxic study of the scaffolds on human cancer cell lines including C32 normal cells, human keratinocytes (HaCaT), breast adenocarcinoma (MCF-7/WT), melanotic (A375), glioblastoma (SNB-19) and drug-resistant breast adenocarcinoma (MCF-7/DX) unveiled that scaffolds 36a and 36b showed the maximum anti-cancer potential with IC50 values of 170.28 ± 10.22 μM, 115.12 ± 6.91 μM, 119.29 ± 7.16 μM, 80.79 ± 4.85 μM, 126.02 ± 7.56 μM, and 137.31 ± 8.24 μM and 304.39 ± 15.21 μM, 270.32 ± 13.25 μM, 261.40 ± 13.07 μM, 202.47 ± 10.12 μM, 295.81 ± 14.71 μM, and 295.81 ± 14.92 μM, respectively, and scaffold 36b demonstrated a significant cytotoxic effect against A375 cells (IC50 value of 8.79 μM). Additionally, hybrids 36a and 36b at a concentration in the range of 100–200 μM resulted in a substantial alteration in the cytoskeleton organization in all the cell lines. Moreover, hybrid 36b caused cell death and DNA damage due to early apoptosis in A375 cells and late apoptosis at an increased concentration in C32 cells. Further, the docking results revealed 4 different receptors such as c-Met, EGFR, HER2, and hTrkA, which disclosed that hybrid 36c had the maximum binding affinity with EGFR (−12.9 kcal mol−1), followed by the binding affinity of hybrid 36b (−12.9 kcal mol−1). Furthermore, the structure–activity study highlighted that an electron-withdrawing group such as NO2 in hybrid 36c enhanced its activity against EGFR.151

Fig. 39. Design and SAR of 1,3,4-oxadiazole-based 4,6-dimethyl pyridine frameworks as EGFR inhibitors.

Akhtar et al. performed a comprehensive study of QSAR and docking of fused benzimidazole and oxadiazole (37, Fig. 40) as cytotoxic agents against the MCF-7 (breast), HaCaT (human skin), MDA-MB231 (breast) HepG2 (liver) and A549 (lungs) cancer cell lines. Among the analogs, 37a and 37b showed strong inhibition towards the MCF-7 and MDA-MB231 cancer cell lines with IC50 values of 5.0 μM and 2.55 μM and 0.131 μM and 14.5 μM, respectively. The inhibition of EGFR and erbB2 receptor by analog 37a was observed with IC50 values of 0.081 μM and 0.098 μM, respectively. Additionally, the cell cycle and cell apoptosis results for 37a indicated that 33.6% cell cycle inhibition occurred in the G2/M phase and it induced apoptosis in the MCF-7 cells in the early/primary phase. Further, the docking analysis disclosed that hybrids 37a and 37b bind to the active site of EGFR, which highlighted their H-bonding interaction with Asp831. Furthermore, the 3D analysis highlighted that the hydrogen bond donor, electron-withdrawing group, and hydrophobic activity of substituted phenyl and unsubstituted benzimidazole were essential for the observed activity.152

Fig. 40. Design and SAR of fused benzimidazole and oxadiazole frameworks as EGFR inhibitors.

Hagar et al. derived chalcone- and benzimidazole-based 1,3,4-oxadiazole analogues (38, Fig. 41) as dual EGFR and BRAFV600E inhibitors. The anti-proliferative activity disclosed that analogues 38a, 38b and 38c had showed highest inhibition towards four different cancer cell lines including Panc-1, HT-29, MCF-7, and A-549 with IC50 values in the range of 0.9–12.5 μM compared to doxorubicin with IC50 values in the range of 0.9–1.41 μM. Additionally, analogues 38a and 38b showed strong inhibition towards BRAFV600E and EGFR with IC50 values of 1.70 μM and 1.90 μM and 0.55 μM and 0.80 μM respectively. Further, the evaluated analogues 38a, 38b and 38c were found to show remarkable activity in inducing the expression of BAX and Bcl-2 protein, activation of caspase-3 and inhibition of EGFR and BRAFV600E. Furthermore, the molecular docking simulation exhibited promising binding modes (10.6, 10.7, and 10.4) and binding scores (−9.8, −9.9, and −9.8) and stability of analogues 38a, 38b and 38c in the innermost kinase domain of EGFR and BRAFV600E with the co-crystallized ligand, respectively. Finally, the SAR analysis indicated that the substitution of the phenyl ring with a para-methoxy group and para-chloro atom resulted in elevated activity.153

Fig. 41. Design and SAR of explored chalcone- and benzimidazole-based 1,3,4-oxadiazole analogues as dual EGFR and BRAFV600E inhibitors.

El Mansouri et al. designed a library of homonucleoside 1,3,4-oxadiazoles congeners (39, Fig. 42) and evaluated their anti-tumour and in vitro cytotoxic activity against leukemia (HL60) and breast (SKBR3 and MCF7) cancer cell lines. Congeners 39a, 39b and 39c showed promising activity towards both cell lines. Additionally, the antiviral study demonstrated that congener 39b showed the most prominent activity against the human TK Varicella zoster virus compared to acyclovir. Moreover, the docking simulation indicated that congeners 39c and 39b acted as dual EGFR/HER2 inhibitors with low Ki constants in the range of 1.25–3.18 μM and interacted via C-H bond, π-anion, π-sulphur, π-sigma, alkyl, and π-alkyl interactions. Finally, the structure–activity relationship suggested that the introduction of the nucleobase theobromine enhanced the EGFR inhibition activity.154

Fig. 42. Design and SAR of a library of homonucleoside 1,3,4-oxadiazoles congeners as EGFR inhibitors.

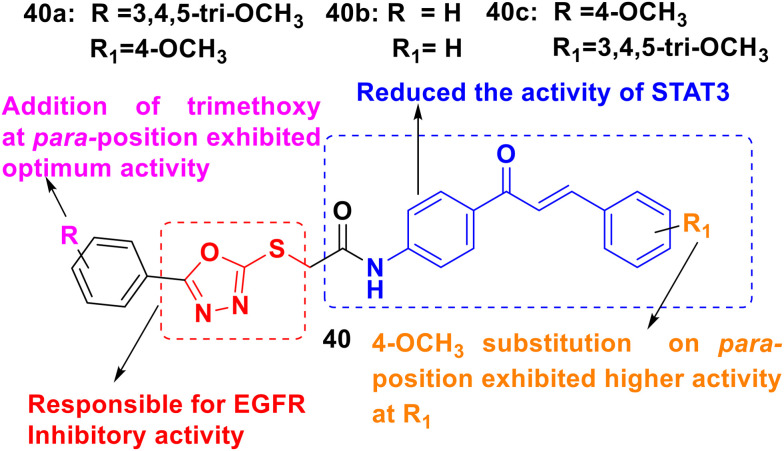

A series of chalcone/1,3,4-oxadiazole derivatives (40, Fig. 43) were explored by Fathi et al. as anti-cancer agents against 60 different cancer cell lines and 9 sub panels. The kinase study of EGFR and Src kinase revealed that the derivatives 40a, 40b and 40c (IC50 = 0.24, 1.23, and 2.35 μM, respectively) were potent EGFR and Src kinase inhibitors. Additionally, the anti-proliferative study disclosed that derivative 40a had powerful cytotoxic activity against the K-562 (IC50 = 1.95 μM) and KG-1a (IC50 = 3.45 μM) leukemia cell lines and Jurkat cells (IC50 = 2.36 μM). Moreover, the highly active derivative 40a was also an inhibitor of STAT3. Finally, to attain high anti-cancer activity, the SAR indicated that the phenyl ring should be substituted with a para-methoxy group and the other ring should have a 3,4,5-trimethoxy group.155

Fig. 43. Design and SAR of latest library of chalcone/1,3,4-oxadiazole derivatives as EGFR inhibitors.

Dokla et al. designed a library of congeners (41, Fig. 44) and evaluated their activity as successful inhibitors of EGFR and c-Met, among which hybrid congener 41a showed superior activity against five different NSCLC cell lines and EGFR mutations including H1975 (L858R + T790M), PC9 (DelE746-A750), A549 (wild type), CL97 (G719A + T790M) and CL68 (DelE746-A750 + T790M) with IC50 values of 0.3 μM, 0.6 μM, 0.3 μM, 0.6 μM and 0.5 μM, respectively. Additionally, Western blotting analysis and RT-PCR revealed the high activity of congener 41a in the range of 0.2–0.6 μM, inhibiting c-Met and m-RNA level EGFR expression in the A549 and H1975 cell lines. Further, the cell cycle analysis highlighted the antiproliferative response mediated at the protein level, resulting in cell cycle arrest in the G2/M phase and some apoptosis. Furthermore, congener 41a showed tumor-suppressive activity in TKI-resistant H1975 xenograft tumors and sensitized them to gefitinib.156

Fig. 44. Design and SAR of a library of 1,2,4-oxadiazole offshoots as EGFR inhibitors.

Ahsan et al. designed a series of congeners of oxadiazole and quinazoline (42, Fig. 45) and evaluated their anti-proliferative activity against nine different cell lines and 60 subpanels (NCI-60) according to the National Institute of Cancer (NCI-US) protocol at a concentration of 10 μM. The quinazoline congeners were tested against the melanoma MDA-MB-435 and human cervix (HeLa) cancer cell lines and their LC50, TGI, and GI50 values calculated. Among the oxadiazole congeners, congener 42b exhibited the highest activity towards UO31, CCRF-CEM, HOP-92 (non-small cell lung cancer), A498, PC-3, and T-47D, and with percent GI of 19.53%, 24.42%, 35.29%, 19.53%, 22.27%, 22.00%, and 23.38%, respectively. Additionally, among the examined quinazoline congeners, congener 42a showed the highest activity with GI50 = 31.5 μM, TGI = 63.19 μM and LC50 = 91.33 μM against the human cervix cancer cell line (HeLa) and GI50 = 60.4 μM, TGI > 100 μM and LC50 > 100 μM against melanoma MDA-MB-435. Further, the molecular docking study highlighted that the oxadiazole derivatives had systematic binding potential to the active site of EGFR-TK. Finally, the structure–activity relationship revealed that the methoxyphenyl substituent resulted in higher activity than the chloro and fluoro phenyl substituents on position 5 of the oxadiazole ring and substitution of pyrimidine-2-amine resulted in efficient binding interaction with EGFR-TK.157a

Fig. 45. Design and SAR of recently presented series of congeners of oxadiazole and quinazoline as EGFR inhibitors.

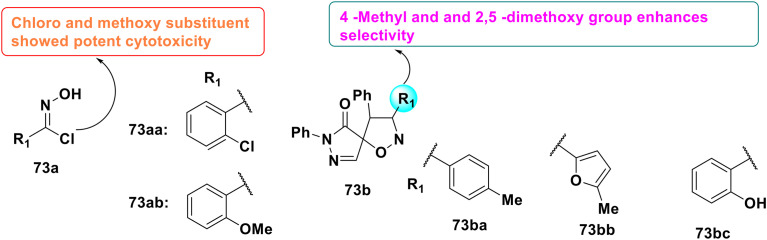

Dubba et al. reported the synthesis of new indole-oxadiazole coupled isoxazole hybrids, as shown in Fig. 46, as potential EGFR-targeting anticancer drugs. The molecules were produced via the Cu(i)-catalyzed 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition of nitrile oxides with 3-(3,5-dichloro-4-methoxyphenyl)-5-(1-(prop-2-yn-1-yl)-1H-indol-3-yl)-1,2,4-oxadiazole. The cytotoxicity assessment of compounds 6g (IC50 = 3.21 ± 0.48 μM) and 6m (IC50 = 2.16 ± 0.52 μM) against the MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell lines showed their enhanced efficacy relative to erlotinib (IC50 = 4.28 ± 0.11 μM). The in vitro studies for EGFR inhibition demonstrated that 6m (IC50 = 0.203 ± 0.03 μM) and 6g (IC50 = 0.311 ± 0.05 μM) had much more potency than erlotinib (IC50 = 0.421 ± 0.03 μM). The SAR analyses demonstrated that EWG (Cl, F, CN) on the isoxazole ring increased the potency. The molecular docking study validated the robust binding interactions inside the EGFR active site, endorsing their potential as lead compounds for further anticancer therapy development.157b

Fig. 46. Design and SAR of new indole-oxadiazole coupled isoxazole hybrids as potential EGFR-targeting anticancer drugs.

4.5. Thiophene-based EGFR inhibitors

Thiophene is a simple, five-membered heterocyclic aromatic ring with two endocyclic double bonds and one sulfur atom in its ring. The synthesis and biological activities of various thiophene derivatives as EGFR inhibitors have been extensively studied over the years.