Abstract

KIN17 may impact epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT) of cancer cells. However, whether KIN17 impacts EMT in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) remains unknown, which was explored in this study. Bioinformatics analyses were conducted to investigate KIN17’s expression pattern, prognostic value in patients of NSCLC and its related genes. The expression of KIN17 was down-regulated in H1299 NSCLC cells and the invasion, proliferation, and migration upon KIN17 knockdown was examined. In addition, the expression of marker proteins of EMT and the Wingless/int1 (WNT1) signaling pathway upon KIN17 knockdown were examined in vitro and in vivo. mRNA and/or protein expression of KIN17 was higher in multiple cancer tissues, especially in NSCLC tissues. Patients of NSCLC with increased KIN17 expression had lowest disease free survival (DFS). The co-expression network of KIN17 enriched pathways revealed links to tumorigenesis and development. KIN17 knockdown in H1299 cells greatly decreased cell invasion, proliferation, and migration. In addition, KIN17 knockdown increased expression of E-cadherin and reduced expression of Vimentin and N-cadherin, which are all markers of EMT. Moreover, KIN17 knockdown in H1299 cells down-regulated the WNT signaling pathway, an inducer of EMT, as evidenced by reduced expression of WNT1 and β-catenin proteins. Finally, KIN17 knockdown significantly reduced tumor growth and down-regulated EMT and the expression of WNT1 and β-catenin proteins in NSCLC xenograft mice. Collectively, KIN17 knockdown suppressed the progression of NSCLC, potentially involving down-regulation of EMT and the WNT/β-catenin pathway.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-08723-7.

Keywords: KIN17, NSCLC, EMT, WNT/β-catenin

Subject terms: Cancer, Computational biology and bioinformatics, Molecular biology

Introduction

With over 2.2 million new cases and over 1.8 million cancer-related deaths globally in 2020, lung cancer is the most common cause of cancer death both in China and worldwide1. According to the statistics of the National Cancer Center of China, the incidence rate and mortality of lung cancer both rank first among malignant tumors in China in 2023, including 781, 000 new cases and 626, 000 deaths2. More specifically, almost 85% of lung cancers are non-small cell lung cancers (NSCLC)3. The prognosis of NSCLC patients remains poor in the absence of effective treatment targets, despite the application of numerous therapeutic procedures, including immunotherapy, surgery, and targeted therapy4. The current standard of therapy for NSCLC patients following complete tumor resection increases five-year survival in about 5% of patients5.The identification and application of numerous biomarkers may help to evaluate the clinical outcomes of various treatment of NSCLC patients. Therefore, it is warranted to identify more reliable biomarkers for improving prognosis in NSCLC.

KIN17 (Kin17) is a DNA/RNA-binding protein that is typically expressed at low levels in human organs and tissues6. Previous studies show that KIN17 is implicated in DNA replication, DNA damage response, and cell cycle progression7,8. Recent studies have shown that the expression of KIN17 is elevated in certain cancers, such as breast cancer9 hepatocellular carcinoma10 and NSCLC11. Particularly, KIN17 knockdown in the NSCLC cell line A549 inhibits cell motility and invasion11. Likewise, KIN17 serves as an essential regulator of the cell migration and invasion involving the NF-κB-Snail pathway in cervical cancer12. Together, these studies suggest that KIN17 may play a role in the metastatic spread of cancer cells. However, the underlying mechanism remains poorly understood.

It is known that epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT) is a crucial process for metastasis in numerous cancers13. There are evidences that KIN17 may impact EMT of cancer cells. For instances, silencing of KIN17 increases the expression of EMT-associated E-cadherin and decreases the expression of EMT-associated N-cadherin in thyroid cancer cells 8505 C and SW57914; knockdown of KIN17 decreases EMT-associated β-catenin, Vimentin, and claudin-1 in luminal-A breast cancer cells MCF-715. However, so far, whether KIN17 impacts EMT in NSCLC remains unknown.

In this study, we conducted bioinformatic analysis to explore the survival analysis of KIN17 expression in patients of NSCLC, the dysregulation of KIN17 expression in Pan-Cancer and the KIN17-interacted molecule network. Moreover, we examined the expression of marker proteins in EMT and pathways of Wingless/int1 (WNT)/-catenin, an inducer of EMT16upon KIN17 knockdown in the NSCLC cell line H1299. Finally, we explored the effects of KIN17 knockdown on NSCLC tumorgenesis in vivo.

Methods

Identification of KIN17 expression and survival prognosis analysis based on bioinformatics databases

A query was conducted in Tumor Immune Estimation Resource (TIMER) to compare the mRNA expression of KIN17 in normal and tumor tissues17. KIN17’s protein expression in lung cancers was examined through the Clinical Proteomic Tumor Analysis Consortium (CPTAC)18. Z-values for lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) and lung squamous cell carcinoma (LUSC), two common subtypes of NSCLC, denoted SD from the median for all samples, respectively. After standardization within each sample profile, the log2 spectral count ratio values from CPTAC were then normalized across samples. Besides, KIN17’s prognostic values for LUAD and LUSC patients, such as disease free survival (DFS) was examined in The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA)19 the Kaplan–Meier plotter20 and GEPIA2 database18.

Enrichment analysis of KIN-related genes

The interacting proteins of KIN17 were explored through the STRING (search tool for recurring instances of neighbouring genes) website using the default setting21. The KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) enrichment analysis of KIN17 interaction with other proteins was conducted through the ClusterProfiler R package using the default setting.

Cell lines and culture

One human non-tumorigenic lung epithelial cell line (BEAS-2B) and two human NSCLC cell lines (A549 and H1299) were purchased from the Cell Bank of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). All the cells were maintained and grown in DMEM (Gibco, China) which contained 1% antibiotics (penicillin–streptomycin) and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco, China). The cells were grown at 37℃ in a CO2 incubator.

shRNA-mediated KIN17 knockdown in H1299 cell

pLV.i lentiviral constructs encoding control sh-NC and three distinct shRNAs targeting human KIN17 (sh-KIN17-a, sh-KIN17-b, and sh-KIN17-c, sequences were listed in Table S1) were created by Guangzhou Boyao Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Guangzhou, China). HEK-293T cells were transfected with the lentivirus helper plasmids and the constructs using the polyethylenimine (pei) method22. The successfully produced lentiviral particles were added to H1299 cells with 5 µg/mL polybrene, and stable clones were selected by replacing the culture medium with that containing puromycin (2 µg/mL), respectively. Stable cells were used in the following analysis.

Cell proliferation assay

The CCK-8 assay was employed to investigate the rate of cell proliferation. 96-well plates were used, and 5 × 103 cells in total were seeded into each well before being cultured in a cell incubator. CCK-8 solution (10 µL, Abcam, UK) was added to each well at 0, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h, respectively, incubated with the grown cells in the incubator for two more hours, and the absorbances (450 nm) were examined through a microplate reader (Thomas Scientific, NJ, USA).

Cell migration and invasion assays

Cells were grown in six-well plates in the migration assay (6 × 104 cells/well) with 100% confluent. A 200-µL pipette tip was utilized to make a linear scratch in the cell monolayer. The wound width was determined using the Image J software (version 1.8.0, National Institutes of Health). The wounds were photographed under a light microscope after 24 h (Nikon Corporation; magnification x100). The migration distance was determined by subtracting the scratch’s width at 0 h from its width at 24 h. By normalizing the control group, the relative migration rate was calculated.

The cells (4 × 105) were plated in the top chamber in the invasion assay with a membrane coated with Matrigel (Corning Incorporated, U.S.A). Conditioned medium was filled in the bottom chambers. Following a 48-hour incubation, the cells were fixed for 0.5 h at room temperature with 4% paraformaldehyde, and then stained for 30 min at 37 °C with 0.1% crystal violet. In three random fields, the number of cells moving through the membrane was observed and photographed using a 100x magnification light microscope (Nikon Corporation).

Apoptosis assay and cell cycle analysis

Annexin V (Annexin V-FITC-PI kit; Beyotime, Shanghai, China) and propidium iodide (PI) were used to stain cells in accordance with the instructions of the manufacturer. The stained cells were subjected to analysis in a BD FACSVerse™ cell analyzer (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, U.S.A).

Cells (1 × 107) were collected, PBS-washed, and fixed in ethanol (70%) for 2 h at 4 °C for the cell cycle analysis. Following a PBS wash, the cells were incubated with RNase A (10 mg/L) for 30 min at 37 °C followed by incubation in PI (10 g/mL) for 30 min at 4 °C. The distribution of cell cycle was examined in the BD FACSVerse™ cell analyzer. NovoExpress software (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) was used to analyze the data.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)

TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) was employed to extract total cellular RNA in accordance with the recommendations of the manufacturer and 1 µg of RNA was reverse-transcribed into cDNA using oligo (dT) primers. qRT-PCR was performed using SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix (Roche, Shanghai, China) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The initial denaturation at 95 °C for 10 min was followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 45 s for the amplification. The reactions were carried out in triplicate, and the comparative CT (2−△△CT) method was used for relative quantification. The particular primers used for the amplification of β-actin and Kin17 were listed in Table S2.

Western blot (WB)

RIPA lysis buffer (Beyotime Biotech. Inc., China) was used to extract the total protein from cells. Protease inhibitors (Beyotime Biotech. Inc., China) were incorporated (1:100) to the lysis buffer. The lysates were centrifuged for 15 min at 4˚C, 850 x g. The proteins (30 µg/lane) were separated using SDS-PAGE (15%), and the total protein was quantified using a BCA kit (Beyotime Biotech. Inc., China). The isolated proteins were then transferred to PVDF membranes (EMD Millipore) and blocked for 2 h at room temperature with 5% BSA (Beyotime Biotech. Inc., China). The following primary antibodies were applied to the membranes and incubated overnight at 4℃: anti-β-catenin (A302-010 A-T), anti-WNT1 (MA5-15544), anti-E-cadherin (PA5-32178), anti-Vimentin (PA5-27231), anti-KIN (PA5-40419), anti-β-actin (PA1-988), and anti-N-cadherin (PA5-19486), respectively. All of these antibodies were purchased from Thermofisher Scientific, USA. The membranes were then rinsed with TBS that contain 0.1% Tween-20 and incubated for 1.5 h at room temperature with either a donkey anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (BA1055, Boster, China) or a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (BA105,Boster, China) after primary incubation. Using Image-Pro Plus version 6, the protein bands were measured and visualized through the Odyssey Western Blot Analysis system (Tanon, China).

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining

Tissue samples were embedded in paraffin, cut into sections of 4 μm thickness, deparaffinized in xylene, rehydrated using graded ethanols, and blocked in 3% hydrogen peroxide for 10 min at 25℃. Specific primary antibodies against N-cadherin (PA5-19486), E-cadherin (PA5-32178), and Vimentin (PA5-27231) were incubated with tumor sections for 12 h at 4℃, respectively. The secondary antibody (Alexa Fluor 488) was then incubated with the tumor tissues at 25℃ for 2 h. All the antibodies were purchased from Abcam in Cambridge, MA, USA. The slides were photographed using Olympus IX73 microscope (Tokyo, Japan).

Nude mice xenograft experiments

The adult male nude mice (BALB/c, 4 weeks old) were purchased from Guangzhou Forevergen Biosciences, China. To ensure a comfortable environment, each cage housed four mice. H1299 cells stably transfected with the constructs sh-NC and sh-KIN17 were subcutaneously administered into the right and left sides of eight four-week-old nude mice (1 × 107 cells per mouse) for inducing tumors, respectively. During the following 30 days, the mice were observed daily to track the development of tumors. The tumor’s length (L) and width (W) were measured, and the tumor’s volume (V) was computed using the formula V(mm3) = 0.5 × (W)2 × (L). The tumors from each mouse were weighed and subjected to IHC staining at the end of the analysis. If xenografts reached a size of 20 mm in any one dimension or clinical signs of morbidity (e.g. body weight loss > 20%, inactivity, dyspnea) were observed, it would be considered to be humane endpoints. Mice were observed daily for the above humane endpoints. None of the mice were found to have reached the above humane endpoints or died during the experiment of 30 days. Mice were sacrificed at the end of the experiment via a deep sodium pentobarbital anesthesia (60 mg/kg, intraperitoneal). All animal experiments and procedures followed the guidelines of the Laboratory Animal Centre of the Second People’s Hospital of Guangdong Province. The protocols regarding animals were approved by the Second People’s Hospital of Guangdong Province Ethics Committee (ethical approval number: GD2H-KY IRB-AF-SC.07-01.1). All studies reported herein were performed in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines (https://arriveguidelines.org).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using the R (v.4.2.2) software, GraphPad Prism 8 and SPSS 22.0. The number of stars in TIMER2 indicated the statistical significance determined by the Wilcoxon test. The Kaplan-Meier technique was used to determine the relationship between patient prognosis and KIN17 expression levels. P < 0.05 was deemed statistically significant.

Results

Expression of KIN17 in Pan-Cancer and survival analysis of KIN17 expression in NSCLC

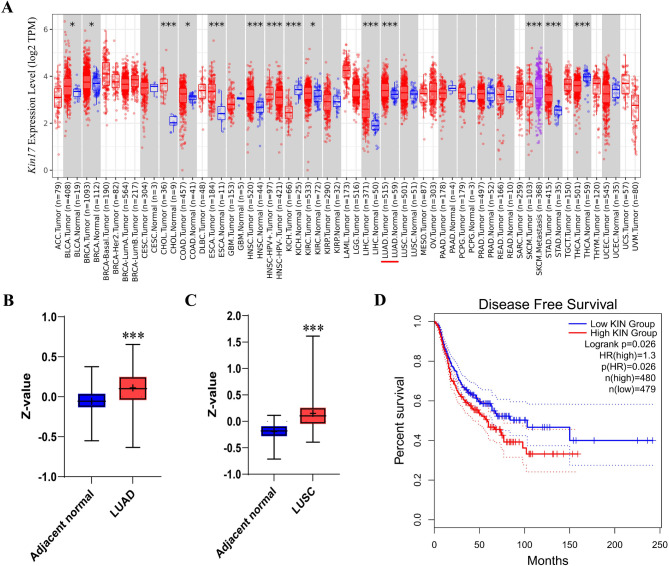

The mRNA expression of KIN17 was examined in the TIMER database. Ten cancer tissues, including breast invasive carcinoma (BRCA), bladder urothelial carcinoma (BLCA), colon adenocarcinoma (COAD), cholangiocarcinoma (CHOL), head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSC), esophageal carcinoma (ESCA), liver hepatocellular carcinoma (LIHC), kidney renal clear cell carcinoma (KIRC), stomach adenocarcinoma (STAD), and LUAD showed considerably up-regulated KIN17 expression. In addition, the expression of Kin17 gene tended to increase in LUSC, although the increase was statistically insignificant. Conversely, KIN17 expression was markedly down-regulated in three cancers, including thyroid carcinoma (THCA), kidney chromophobe (KICH), and skin cutaneous melanoma (SKCM) (Fig. 1A). In the large-scale proteome data from the National Cancer Institute, the KIN17 protein level between normal samples and LUAD or LUSC was further evaluated. KIN17 total protein expression was considerably higher in LUAD (P < 0.001, Fig. 1B) and LUSC (P < 0.001, Fig. 1C). The analysis in GEPIA2 showed that increased expression of KIN17 was linked to a poor prognosis in the patients of LUAD and LUSC (P < 0.05, Fig. 1D).

Fig. 1.

Aberrant expression of KIN17 in pan-cancer. (A) Kin17 gene expression examined through the TIMER2 database. (B) KIN17 protein expression in normal tissue and LUAD performed by CPTAC. (C) KIN17 protein expression in normal tissue and LUSC performed by CPTAC. (D) Survival analysis of KIN17 expression in LUAD and LUSC patients performed in GEPIA2. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 as tumor samples compared to adjacent nontumor samples.

Interacting proteins of KIN17 and enrichment pathway analysis

To explore the molecular mechanism of KIN17 in carcinogenesis, we analyzed the interacting proteins of KIN17 using STRING. Ten putative KIN17-binding proteins were predicted (Fig. 2A), including seven lysine specific methyltransferases belong to the Methyltransferase Family 1623, VCPKMT, FAM86A, METTL20, METTL21A, METTL21C, METTL22 and METTL23, RECQL524, the sole member of the RECQ family of helicases associated with RNA polymerase II (RNAPII), SF3A2, a splicing factor25 and ZNF277, a transcription factor26. Moreover, as shown in Fig. 2B, KIN17 might be involved in tight junction, WNT signaling pathway, regulation of actin cytoskeleton, and focal adhesion.

Fig. 2.

Co-expression network and KEGG enrichment analysis of co-expressed genes with KIN17. (A) Interaction of KIN17 co-expressed genes by using the online STRING tool. (B) Co-expressed gene KEGG enrichment pathways.

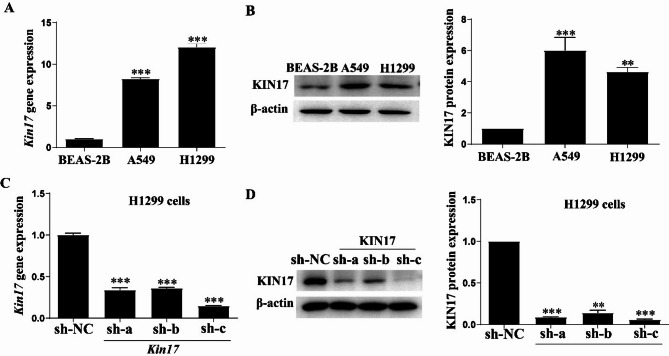

KIN17 expression in lung cancer cells

The gene and protein expression of KIN17 in one human bronchial epithelial cell line (BEAS-2B) and two NSCLC cell lines (H1299 and A549) was examined. We found that KIN17 expression was higher in both H1299 and A549 cells (Fig. 3A and B). Although the gene expression of Kin17 was higher in H1299 than in A549 cells (Fig. 3A), the protein expression of KIN17 was higher in A549 than in H1299 cells (Fig. 3B). However, as the p53 gene is frequently mutated in NSCLC27 the H1299 cell line which has the null p53 gene instead of the A549 cell line which has the wild type one28 was chosen and stably transfected with sh-KIN17 or sh-NC. As anticipated, stable transfection with sh-KIN17-c decreased KIN17 expression considerably in the H1299 cells (P < 0.001, Fig. 3C and D). Therefore, the sh-KIN17-c was chosen in subsequent study.

Fig. 3.

Knockdown of KIN17 in H1299 cells. (A, B) Relative KIN17 levels in NSCLC cell lines and nontumorigenic lung epithelial cells by qRT-PCR and WB. (C, D) KIN17 knockdown efficiency was verified using qRT-PCR and WB.

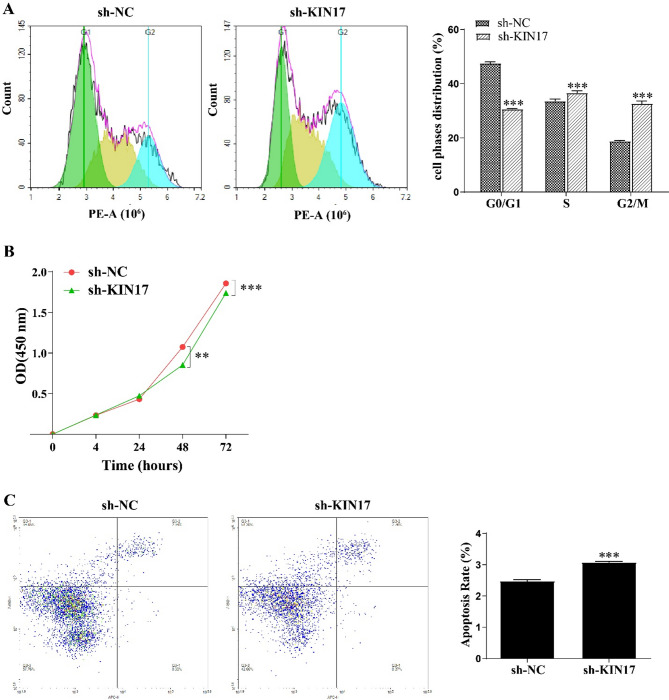

Knockdown of KIN17 arrested cell cycle and induced apoptosis in H1299 cells

We found that KIN17 knockdown prevented H1299 cells from entering the G2/M phase, as shown by flow cytometry analysis (P < 0.001, Fig. 4A). In addition, we found that KIN17 knockdown dramatically reduced H1299 cell proliferation for 48 h through the CCK-8 assay (P < 0.01, Fig. 4B). Finally, we found that knockdown of KIN17 increased the apoptosis of H1299 cells moderately (P < 0.001, Fig. 4C). These results indicated that KIN17 knockdown decreased proliferation of H1299 cells and enhanced apoptosis.

Fig. 4.

Knockdown of KIN17 arrested cell cycle and induced apoptosis in H1299 cells. (A) KIN17 knockdown arrested G2/M phase in H1299 cells determined by flow cytometry analysis. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001, compared with sh-NC. (B) CCK-8 assay to assess the proliferation rate of H1299 cells. (C) KIN17 knockdown induced apoptosis of H1299 cells. All experiments were repeated three times.

Knockdown of KIN17 decreased cell migration and invasion

We found that cells with KIN17-knockdown migrated more slowly than cells transfected with sh-NC after 24 h through a scratch wound healing assay (P < 0.001, Fig. 5A). Furthermore, the transwell assay revealed that KIN17 knockdown dramatically reduced invasive cell number (P < 0.001, Fig. 5B). These results suggested that KIN17 knockdown decreased invasion and migration of H1299 cells.

Fig. 5.

Knockdown of KIN17 decreased migration and invasion of H1299 cells. (A) Scratch wound healing assay to evaluate the migration ability of H1299 cells. (B) Transwell assays were performed to assess the invasive capacity of H1299 cells. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001, compared with sh-NC. All experiments were repeated three times.

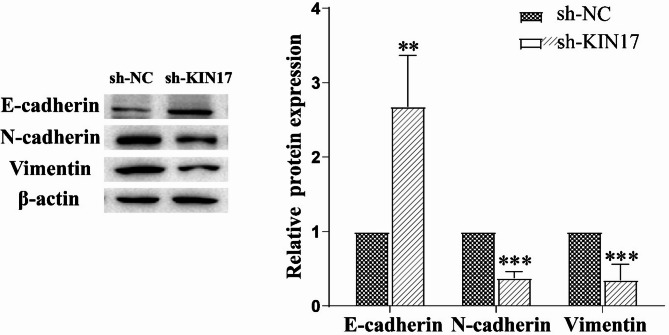

Knockdown of KIN17 impacted expression of the EMT markers

EMT is an important process in cancer metastasis13. The hallmark of EMT is the upregulation of N-cadherin followed by the downregulation of E-cadherin29. Vimentin is another key biomarker in EMT whose dynamic structural changes and spatial reorganization in response to extracellular stimuli assists in coordinating various signaling pathways to promote metastasis30. Immunoblotting analysis showed that knockdown of KIN17 reduced the protein expression of N-cadherin and vimentin (Fig. 6, P < 0.001) while increased the expression of E-cadherin (Fig. 6, P < 0.001). These results suggested that EMT of H1299 cells may be downregulated upon KIN17 knockdown.

Fig. 6.

Knockdown of KIN17 decreased the expression of EMT marker proteins. EMTassociated protein expression detected by western blotting (left); quantification of Western blot analysis (right). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001, compared with sh-NC. All experiments were repeated three times.

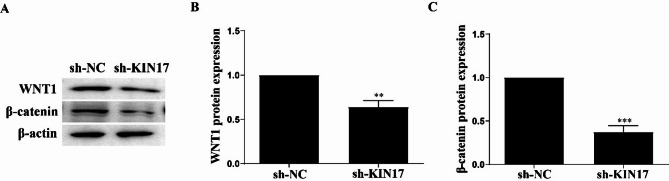

Knockdown of KIN17 decreased the expression of WNT1 and β-catenin proteins

As revealed above, bioinformatics analysis showed that KIN17 might be involved in WNT signaling pathway which can induce EMT16 and are implicated in the pathogenesis of NSCLC31. This result prompted us to investigate whether KIN17 also impacts the WNT signaling pathway simutaneously. Wnt proteins are secreted glycoproteins and the ligands of the Wnt signaling pathway32. As shown in Fig. 7A & B, the expression of WNT1 was decreased (P < 0.01) upon KIN17 knockdown in the H1299 cells compared to the control. Wnt signaling is transduced through the transcription factor β-catenin32. As shown in Fig. 7A & C, the expression of the β-catenin protein was also decreased upon KIN17 knockdown in the H1299 cells compared to the control (P < 0.001).

Fig. 7.

Knockdown of KIN17 decreased the expression of WNT1 and β-catenin proteins in H1299 cells. (A) Representative blots of Wnt/β-catenin pathway proteins (WNT1 and β-catenin). (B) Quantitative analysis of WNT1. (C) Quantitative analysis of β-catenin. Data are represented by the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001, compared with sh-NC. All experiments were repeated three times.

Knockdown of KIN17 alleviated NSCLC tumor growth and downregulated EMT markers and WNT/β-catenin signaling in vivo

As shown in Fig. 8, mice that received administration of H1299 cells stably transfected with shNC developed tumors quickly and the tumor volume increased progressively. Nevertheless, the tumor volume was consistently and considerably lower in the sh-KIN17 groups than in the sh-NC group (Fig. 8A and B). In addition, the tumor weight in the sh-KIN17 groups was considerably lower than that of the sh-NC group (P < 0.001, Fig. 8C). Immunohistochemistry staining revealed that KIN17 knockdown reduced the expression of vimentin and N-cadherin while the E-cadherin expression was enhanced (Fig. 8D). Finally, we found that the expression of the proteins KIN17, WNT1 and β-catenin were all lower in the sh-KIN17 group than that in the sh-NC group (Fig. 8E-H). Together, these results suggested again that KIN17 knockdown may down-regulate the WNT/β-catenin signaling pathway and impair EMT in tumor tissues of NSCLC.

Fig. 8.

Knockdown of KIN17 inhibited NSCLC tumor growth and metastasis in vivo. (A) Xenografts produced by H1299-sh-KIN17 (indicated by a green arrow) and H1299-sh-NC cells (indicated by a red arrow) from individual groups. (B) Quantification of the tumor volumes produced by H1299-sh-KIN17 (indicated by a green arrow) and H1299-sh-NC cells (indicated by a red arrow) from individual groups at the indicated time points. (C) Quantification of the tumor weight from individual groups at Day 30. (D) Representative IHC staining images of E-cadherin, N-cadherin and Vimentin in each group. (E-H) Representative blots of the KIN17 protein and Wnt/β-catenin pathway proteins (WNT1 and β-catenin) and Quantitative analysis of KIN17, WNT1 and β-catenin in each group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001, compared with sh-NC.

Discussion

The prognosis for NSCLC is poor due to high metastasis and the difficulty of early diagnosis4. Much effort has been made to identify new biomarkers of NSCLC for diagnosis or potential gene targets for therapy. Several investigations have demonstrated that Kin17, a highly conserved gene among species6is strongly linked to the repair and replication of DNA in mammalian cells7,8. In human cells, KIN17 is a crucial component for DNA replication8. Inhibiting KIN17 expression dramatically reduces the effectiveness of DNA replication in cells and even interferes with the normal cell cycle7. Although KIN17 and cell proliferation are closely associated7,8,33 its function in cancer cells, particularly in NSCLC, is still poorly understood. In this report, we showed that KIN17 knockdown reduced cell cycle and proliferation while promoted apoptosis in NSCLC cells. These results were consistent with the studies of KIN17 in other cancers. For instances, Kou et al. showed KIN17 up-regulation in hepatocellular carcinoma tissue, and ectopic KIN17 up-regulation promoted hepatocellular carcinoma cell growth both in vitro and in vivo10; it was found that KIN17 expression is elevated in triple-negative breast cancer cells, and in vitro silencing of KIN17 repressed breast cancer cell proliferation and accelerated apoptosis9. Moreover, we found that KIN17 expression was higher in LUAD and tended to be higher in LUSC, the two most prevalent subtypes of NSCLC and high expression of KIN17 was linked to a poor prognosis in LUAD and LUSC patients. Together, these results suggest that KIN17 might serve as a prognostic indicator of NSCLC treatment which awaits future verification in epidemiological and mechanistic studies.

EMT of cells further promotes tumor cell migration and invasion, and is crucial for the development of many different tumors, particularly in the metastasis stage13. Previous studies showed that KIN17 dysregulation impacts EMT in certain cancer cells. For instances, KIN17 knockdown prevents cervical cancer Siha and Hela cells and luminal-A breast cancer MCF-7 cells from invading and migrating and down-regulates the EMT marker proteins like β-catenin, Vimentin and Snail12,15. Similarly, we found that KIN17 knockdown in NSCLC reduced the expression of EMT marker proteins Vimentin and N-cadherin while increased the expression of another marker protein E-cadherin, which was consistent with these studies. However, so far, how KIN17 regulates EMT in cancer cells has been rarely investigated. EMT can be induced by a number of pathways, such as the WNT/β-catenin, TGF-β and Notch pathways34. Among them, it has been established that the WNT/β-catenin pathway involved in a number of biological processes, such as cell cycle regulation, tumor cell proliferation and apoptosis32is crucial in the EMT of numerous tumors16. Through the activation of the β-catenin/T-cell factor (TCF) complex and subsequent regulation of target genes (Twist, Snail, and MMPs) with TCF-binding elements, aberrant activation of WNT/β-catenin signaling plays a critical role in cancer progression and metastasis16. In this study, in vitro and in vivo results showed that the expression of WNT1 and β-catenin proteins were both decreased upon knockdown of KIN17. Together, these results suggested that down-regulation of EMT and WNT/β-catenin signaling may together contribute to reduced proliferation, invasion and migration upon KIN17 knockdown in NSCLC cells.

Notably, seven of the ten interacting proteins predicted by STRING belong to the Methyltransferase Family 16 which encompasses lysine specific methyltransferases23. Intriguingly, it has been found that METTL22, one of these seven methyltransferases, interacted to methylate KIN17 on lysine 135 and affects its association with chromatin35. This report may validate to some extent of this prediction although there have been no reports showing interactions between KIN17 and the other nine proteins in the list including the other six methyltransferases. Moreover, as disassociation between KIN17 and chromatin may compromise KIN17 functions in global genome repair, DNA replication and DNA transcription and consequent involvement in tumorigenesis7,8 interaction between KIN17 and METTL22 or potentially other lysine specific methyltransferases may serve as an negative mechanism to regulate the involvement of KIN17 in tumorigenesis35. In addition to the seven lysine specific methyltransferases, RECQL5, a DNA helicase24 SF3A2, a splicing factor25 and ZNF277, a transcription factor26 were the three remaining proteins in the list. As mentioned above, previous studies have indicated that KIN17 is involved in DNA repair replication and transcription. Therefore, the predicted interactions between KIN17 and these three proteins seemed to be consistent with the known functions of KIN17 and await future verification.

Conclusions

In vitro and in vivo evidence showed that KIN17 knockdown suppressed the progression of NSCLC, potentially involving down-regulation of EMT and the WNT/β-catenin pathway.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

HC and JL contributed to the concept of the study, analyzed and interpreted the data, and took the lead in writing the manuscript. PL contributed to the concept of the study, collection of the data, and interpretation of the results. XL and ZS contributed to collection of the data. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Guangzhou Municipal Science and Technology Project (Grant No. 202102080131).

Data availability

The datasets used or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

The original online version of this Article was revised: In the original version of this Article, Figure 1A was truncated. In addition, the Funding section was omitted. Full information regarding the corrections made can be found in the correction for this Article.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

9/24/2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1038/s41598-025-20241-0

Contributor Information

Hao Chen, Email: chenh@gzsport.edu.cn.

Junhong Lv, Email: junhonglv@163.com.

References

- 1.Sung, H. et al. Global Cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. Cancer J. Clin.71, 209–249. 10.3322/caac.21660 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oncology Society of Chinese Medical, A. &. [Chinese Medical Association guideline for clinical diagnosis and treatment of lung cancer (2023 edition)]. Zhonghua yi xue za zhi. 103, 2037–2074. 10.3760/cma.j.cn112137-20230510-00767 (2023). Chinese Medical Association Publishing. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Nasim, F., Sabath, B. F. & Eapen, G. A. Lung Cancer. Med. Clin. North. Am.103, 463–473. 10.1016/j.mcna.2018.12.006 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herbst, R. S., Morgensztern, D. & Boshoff, C. The biology and management of non-small cell lung cancer. Nature553, 446–454. 10.1038/nature25183 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schussler, O. et al. Twenty-Year survival of patients operated on for Non-Small-Cell lung cancer: the impact of tumor stage and Patient-Related parameters. Cancers (Basel). 14. 10.3390/cancers14040874 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Kannouche, P. et al. Molecular cloning and characterization of the human KIN17 cDNA encoding a component of the UVC response that is conserved among metazoans. Carcinogenesis21, 1701–1710. 10.1093/carcin/21.9.1701 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miccoli, L. et al. Selective interactions of human kin17 and RPA proteins with chromatin and the nuclear matrix in a DNA damage- and cell cycle-regulated manner. Nucleic Acids Res.31, 4162–4175. 10.1093/nar/gkg459 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Masson, C. et al. Global genome repair is required to activate KIN17, a UVC-responsive gene involved in DNA replication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.100, 616–621. 10.1073/pnas.0236176100 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gao, X. et al. Knockdown of DNA/RNA-binding protein KIN17 promotes apoptosis of triple-negative breast cancer cells. Oncol. Lett.17, 288–293. 10.3892/ol.2018.9597 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kou, W. Z. et al. Expression of Kin17 promotes the proliferation of hepatocellular carcinoma cells in vitro and in vivo. Oncol. Lett.8, 1190–1194. 10.3892/ol.2014.2244 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang, Y. et al. Upregulation of KIN17 is associated with non-small cell lung cancer invasiveness. Oncol. Lett.13, 2274–2280. 10.3892/ol.2017.5707 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhong, M. et al. Kin17 knockdown suppresses the migration and invasion of cervical cancer cells through NF-κB-Snail pathway. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol.13, 607–615 (2020). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hu, J. L. et al. CAFs secreted exosomes promote metastasis and chemotherapy resistance by enhancing cell stemness and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in colorectal cancer. Mol. Cancer. 18, 91. 10.1186/s12943-019-1019-x (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang, Q. G., Xiong, C. F. & Lv, Y. X. Kin17 facilitates thyroid cancer cell proliferation, migration, and invasion by activating p38 MAPK signaling pathway. Mol. Cell. Biochem.476, 727–739. 10.1007/s11010-020-03939-9 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang, Q. et al. KIN17 promotes tumor metastasis by activating EMT signaling in luminal-A breast cancer. Thorac. cancer. 12, 2013–2023. 10.1111/1759-7714.14004 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xue, W. et al. Wnt/beta-catenin-driven EMT regulation in human cancers. Cell. Mol. Life Sci.81, 79. 10.1007/s00018-023-05099-7 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li, T. et al. TIMER2.0 for analysis of tumor-infiltrating immune cells. Nucleic Acids Res.48, W509–W514. 10.1093/nar/gkaa407 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tang, Z., Kang, B., Li, C., Chen, T. & Zhang, Z. GEPIA2: an enhanced web server for large-scale expression profiling and interactive analysis. Nucleic Acids Res.47, W556–W560. 10.1093/nar/gkz430 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang, Z., Jensen, M. A. & Zenklusen, J. C. A practical guide to the Cancer genome atlas (TCGA). Methods Mol. Biol.1418, 111–141. 10.1007/978-1-4939-3578-9_6 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hou, G. X., Liu, P., Yang, J. & Wen, S. Mining expression and prognosis of topoisomerase isoforms in non-small-cell lung cancer by using Oncomine and Kaplan-Meier plotter. PloS One. 12, e0174515. 10.1371/journal.pone.0174515 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Franceschini, A. et al. STRING v9.1: protein-protein interaction networks, with increased coverage and integration. Nucleic Acids Res.41, D808–815. 10.1093/nar/gks1094 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dautzenberg, I. J. C., Rabelink, M. & Hoeben, R. C. The stability of envelope-pseudotyped lentiviral vectors. Gene Ther.28, 89–104. 10.1038/s41434-020-00193-y (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kernstock, S. et al. Lysine methylation of VCP by a member of a novel human protein methyltransferase family. Nat. Commun.3, 1038. 10.1038/ncomms2041 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saponaro, M. et al. RECQL5 controls transcript elongation and suppresses genome instability associated with transcription stress. Cell157, 1037–1049. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.048 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pellacani, C. et al. Splicing factors Sf3A2 and Prp31 have direct roles in mitotic chromosome segregation. eLife710.7554/eLife.40325 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Liu, Z., Xu, Z., Tian, Y., Yan, H. & Lou, Y. ZNF277 regulates ovarian cancer cell proliferation and invasion through Inhibition of PTEN. OncoTargets Therapy. 12, 3031–3042. 10.2147/OTT.S192553 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takahashi, T. et al. p53: a frequent target for genetic abnormalities in lung cancer. Science246, 491–494. 10.1126/science.2554494 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pustovalova, M. et al. The p53-53BP1-Related survival of A549 and H1299 human lung Cancer cells after multifractionated radiotherapy demonstrated different response to additional acute X-ray exposure. Int. J. Mol. Sci.2110.3390/ijms21093342 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Thiery, J. P., Acloque, H., Huang, R. Y. & Nieto, M. A. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in development and disease. Cell139, 871–890. 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.007 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Usman, S. et al. Vimentin is at the heart of epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT) mediated metastasis. Cancers1310.3390/cancers13194985 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Stewart, D. J. Wnt signaling pathway in non-small cell lung cancer. J. Natl Cancer Inst.106, djt356. 10.1093/jnci/djt356 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nusse, R. & Clevers, H. Wnt/beta-Catenin signaling, disease, and emerging therapeutic modalities. Cell169, 985–999. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.016 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zeng, T. et al. Up-regulation of kin17 is essential for proliferation of breast cancer. PloS One. 6, e25343. 10.1371/journal.pone.0025343 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Deshmukh, A. P. et al. Identification of EMT signaling cross-talk and gene regulatory networks by single-cell RNA sequencing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.11810.1073/pnas.2102050118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Cloutier, P., Lavallee-Adam, M., Faubert, D., Blanchette, M. & Coulombe, B. Methylation of the DNA/RNA-binding protein Kin17 by METTL22 affects its association with chromatin. J. Proteom.100, 115–124. 10.1016/j.jprot.2013.10.008 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.