Abstract

Type 2 diabetes (T2D) is easy to trigger many organ or system lesions, which can lead to various metabolic diseases, such as diabetic kidney disease (DKD), diabetic liver disease, diabetic cardiovascular disease, diabetic foot, etc. Due to the easy availability of stool and blood samples from patients, the study of gut microbes and their metabolites are progressing rapidly. The relationship between pathophysiological alterations of metabolic disorders and gut microbiota composition provides new approaches to precisely identify disease dynamics and refine disease treatment strategies. The aim of this review is to investigate the association between T2D with its complications and gut microbiota. Gut microbial metabolites are a new class of signaling molecules, and the mechanisms and pathways of their signal transduction have also been extensively studied. As a result, we will focus on the characteristics of gut microbiota and its metabolites in metabolic diseases as well as the relationship between gut barrier theory and the circulation of gut microbiota-derived metabolites in vivo. In addition, we elucidate the potential applicability of these characterizations and molecular mechanisms in clinical and pharmacological environment, analyzing their feasibility as predictive molecules for health management and clinically accurate predictions in daily life.

Keywords: Gut microbiota, Metabolic disorder, T2D, Health management, Gut microbiota metabolites, Gut barrier

Introduction

With rising living standards and changing lifestyles, the prevalence of diabetes has risen dramatically in both developed and developing countries, making diabetes a global health priority. Diabetes is a complicated metabolic condition brought on by a number of variables, including age, dietary habit, gender, lifestyle, genetics and epigenetics [1–5]. About 537 million adults worldwide have diabetes, most of T2D, and that number is expected to rise to 783 million by 2045 [6]. Globally, the proportion of people living with undiagnosed diabetes is about 45%, while the figure ranges from 54% in Africa to 24% in North America and the Caribbean [6]. Meanwhile, about 352 million people have impaired fasting glucose, or impaired glucose tolerance [7], which can lead to T2D at a proportion of 5–10% of people within this population each year [8]. Chronic inflammation state exists throughout the progression of diabetes, therebefore, people with diabetes also suffer from a number of complications that are sometimes already present when the disease is diagnosed, and these complications involve dysfunctions in many vital organs all over the body [9], which there are mainly kidney, cardiovascular system, retina, and the nervous system [10–13]. Fibrosis of the liver and the lungs as well as cognitive dysfunction are also emerging as novel pathologies that develop secondary to diabetes [14, 15].

The gut microbiota plays a crucial role in maintaining the physiological functions of the host, when the gut microbiota is disrupted, it can trigger various metabolic diseases, such as obesity, T2D, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), and cardiometabolic diseases [16]. Chronic metabolic diseases display distinct pathophysiological features from healthy individuals, yet are all closely linked to gut microbiota composition (Fig. 1) [17–20]. Through the recent decoding of gut microbial genes, it is found that the detection of relevant microbial targets may be able to identify and predict the occurrence and progression of metabolic diseases, as well as broaden our new perspective on metabolic diseases under the intervention of human gut microbial [21–23]. We focus on the recently discovered potential role of gut microbiota and its metabolites as messengers between the gut microbiota and host metabolism in diabetes and its complications, what’s more, we propose the gut barrier theory for the first time to elucidate the correlation and differences between diabetes and its complications at the level of gut microbiota and metabolites, aiming to provide a new perspective for seeking new biomarkers to prevent the development of diabetes complications.

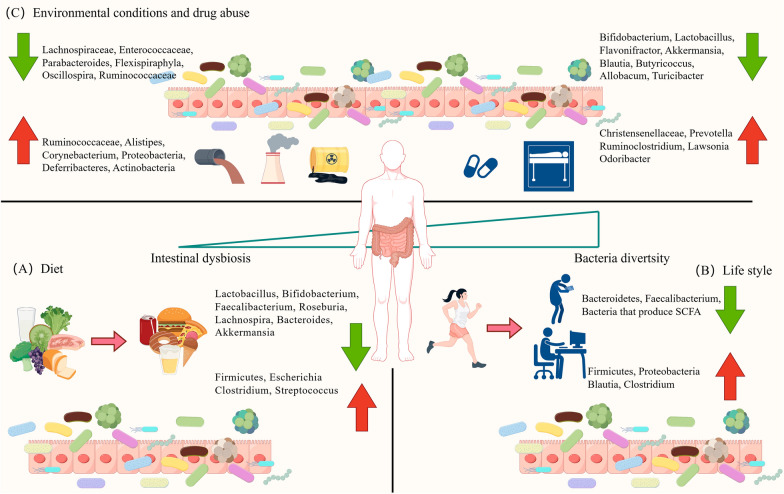

Fig. 1.

Factors affecting gut microbiota architecture in healthy people. A Diet: incorrect diet can change the microbiome architecture. B Life style: bad habits such as sitting for long periods of time and focusing on electronic devices can change the microbiome of healthy people. C Environmental conditions and drug abuse: environmental pollution and the overuse of drugs such as antibiotics disrupt the microbiome of healthy people

Gut microbiota disorder in T2D

Early researches have reported that T2D was closely related to gut microbiota. Actually, a number of clinical researches have demonstrated the anatomical features of the gut microbiota in both healthy individuals and diabetics [24]. In addition, basic research has demonstrated the effects of microbiota on glucose metabolism in both healthy animals and preclinical animal models of diabetes [25, 26].

It was initially discovered in 2010 that the gut microbiota of diabetics is different from health individuals [27]. The research found that compared with the healthy individuals, the relative abundance of Firmicutes and numbers of Bifidobacterium, Clostridium, Firmicutes phylum in diabetics was significantly decreased, while the proportion of Bacteroidetes and Bifidobacteria and numbers of Bacteroidetes and β-Proteus was significantly increased, which was also confirmed in subsequent research reports in other articles [28–31]. The ratios of Bacteroidetes/Firmicutes phylum and Firmicutes phylum/Clostridium were positively correlated with blood [32]. Obesity is a major risk factor for T2D. A number of early classical fecal transplantation experiments have demonstrated that the gut microbiota plays an important role in energy acquisition, adipose tissue accumulation, and insulin resistance [33]. Scientific and effective weight loss can help to reduce the progression of obesity to T2D. However, given the prevalence of the overweight population, bariatric surgery may be a necessary intervention in certain cases. Clinical evidence has shown that a reduction in the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio is common after bariatric surgery, suggesting that in addition to weight loss, mechanisms that ameliorate metabolic diseases such as obesity and dyslipidemia may include favorable alterations in the gut microbiome [34]. For example, the microbiome may also affect bile acid metabolism, which in turn restores dyslipidemia and reduces inflammation [35]. At the functional potential level, the gut microbiota of T2D patients has multiple enrichment patterns which important have sulfate reduction to lower insulin sensitivity, insulin resistance induction through outward transport of branched-chain amino acids, methane metabolism linked to an anaerobe gut environment, and enrichment of membrane transport pathways associated with sugar [17]. Due to drug abuse, the analysis of gut microbiota in T2D patients is confusing. Metformin as a widely used hypoglycemic agent, has the greatest impact on gut microbiota, not only impacting the relative abundance of Enterobacter, Eschella and many other genus and species, but also enhancing the functional potential of several microbiota, such as the production of propionic acid and butyrate, which induce gut gluconeogenesis [36–38].

In order to better understand the relationship between the gut microbiota and T2D, recent epidemiological studies have concentrated on prediabetes. These drug-naive prediabetic patients had altered gut microbiota composition, with fewer butyrate-producing taxa and less Akkermansia muciniphila [26]in the gut microbiota. In addition to this, increasing in the number of microbes that may cause inflammation [20, 24]. Of its effect on host glucose metabolism itself also confirmed that was reported in animal models [25, 39]. Consistent with animal studies, a negative correlation between bacterial abundance and T2D has been reported in human studies [29, 39]. It seems that many studies have found that the association between gut microbiota and diabetes focuses on the activation of inflammatory factors and the damage of glucose tolerance caused by insulin disorders [40, 41]. This proven relationship and previous research confirm my views that modulating the gut microbiota may be a promising strategy for the management of diabetes and related complications, and gut microbiota play different roles in various organs that are independence or connection from each other.

Gut microbiota disorder in liver disease

NAFLD is typically characterized by lipid metabolism disorders and endotoxemia, which are closely related to some gut microbes and their metabolites. Clinical researches have shown that diabetics are prone to NAFLD [42]. Scholars agree that T2D patients with intestinal epithelial barrier is damaged, usually associated with NAFLD [43]. The intestinal and liver are very important metabolic organs of the human body, which coordinate the great responsibility of human metabolism [44] and communicate extensively through the biliary tract, portal vein and systemic circulation which bidirectional crosstalk is called the gut–liver axis [45]. The progression of NAFLD can be prevented by intervening in the gut microbiota [46–48], as a result, gut microbiota play an important role in regulating the balance between gastrointestinal health and disease [45, 49, 50]. For example, in T2D and NAFLD, leaky intestines with translocation of immunocompetent mediators have been described [50, 51], suggesting that multiple host intrinsic and extrinsic signals ultimately lead to impaired gut barrier function. Early studies, concentrations of endotoxin were found to continue to rise in NAFLD. Pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), which are effector molecules of potentially hazardous bacteria, can only enter the liver through damage to the gut barrier. Endotoxin is a typical PAMP and is part of the Gram-negative wall of the symbiotic bacteria. Thus, endotoxins reflect a key gut-derived mediator that is always present in gut–liver communication. Except for endotoxins, many other PAMPs such as lipid cholic acid, lipid and peptidoglycans, lipid peptides, or viral and bacterial DNA can enter the portal vein and reach the liver and even gall bladder [52]. Generally, only a few clinical studies have investigated portal blood, bacteria, and derived metabolites in metabolic liver disease [53]. Koh reports a good example that the concentration of imidazole propionic acid, a bacterial metabolite, in the portal blood of patients with T2D affects insulin signaling [54]. Particularly, imidazole propionate taints insulin signaling by phosphorylating p62 and activating p38 MAPK, which increases the activity of mTOR. McDonald found D-lactic acid that is mediated by commensal-derived D-lactate that was transported to the liver via the portal vein and that is harmed by antibiotic treatment. In addition, he also found D-lactic acid helps liver Kupfer cells clear infections [55]. Therefore, the source of gut microbiota metabolites can control immune liver inflammation. A multi-strain probiotic can alleviate liver steatosis in ob/ob mice, according to a groundbreaking study by Anna Mae Diehl’s lab. This finding suggests that the microbe component plays a role in hepatic steatosis [56]. Cani, P.D. used the same animal model, which validated changes in the gut microbiota to control metabolic endotoxemia, inflammation, and related diseases through a mechanism that can increase gut permeability [57].

Over the past decade, many clinical studies have convincingly demonstrated that patients with NAFLD exhibit gut microbiota disturbances characterized by reduced bacterial diversity, increased abundance of Proteus and Escherichia coli, and declines in Firmicute and F. prausnitzii. It is unclear how these alterations in microbiota characterization leading to NAFLD. Based on the above studies, we can see the relationship between the gut–liver axis and gut microbiota disturbance, and explore the mechanism of intestinal dysfunction affecting liver metabolism and promoting the gut–liver axis through PAMP. In fact, researchers have begun to use strategies to intervene in the gut through fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) for microbial regulation of complex metabolic disorders, such as classical FMT, fecal viral transfer (FVT) and probiotics (i.e., Lactobacillus and bifidobacterium), prebiotics [i.e., fiber and polyphenols) and next-generation probiotics (i.e., Myxophilus, Bacteroides, and bacteroides). Faecalibacterium prausnitzi, Ruminococcus bromii and Roseburia] [58]. The development and function of the gut microbiota can be directly or indirectly altered by these microbiome-based treatment approaches, which can generate advantageous microbial metabolites.

Gut microbiota disorder in kidney diseases

DKD remain the most common cause of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) worldwide. According to clinical data, about 40% [59] of diabetics are DKD due to poor self-management of diabetes, and 20% [60] are hemodialysis patients, these factors in turn lead to ESRD as well as cardiovascular disease(CVD) [61]. Although the pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy is not fully understood. Recently, researchers found that disruption of the gut microbiota can influence the pathological process of DKD [62]. Patients with DKD often have gut microbiota ecological imbalance, accumulation of metabolites in gut microbiota, gut barrier function failure [63, 64]. Metabolites of the gut microbiota have been repeatedly shown to influence the progression of DKD [65], and gut microbial dysbiosis can lead to the evolution of DKD to renal failure [66].

Diabetes can cause renal insufficiency in individuals through a number of mechanisms, such as hyperglycemia, glomerular hemodynamic alterations, and pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic [67–70]. These abnormal functions often lead to glomerular hyperfiltration associated with glomerular hypertrophy. There is increasing evidence supporting bidirectional microbiome–kidney axis, which is particularly evident during the development of kidney dysfunction. Actually, the destruction of the healthy microbiome structure in chronic kidney disease (CKD) results in the large-scale production of uremic solutes by the gut microbes that damages the kidneys. Conversely, the uremic state that caused by decreased renal clearance, causes alterations in the composition and metabolism of microbes, which sets up a vicious cycle of ecological dysregulation and progressive decline in renal function. The most typical sign of diabetic nephropathy progressing to ESRD is uremia. The largest amount of uremic toxins, including p-cresol sulfate (PCS) and indole sulfate (IS), have been widely researched. In the presence of renal insufficiency, toxin retention promotes harmful effects on pathogens [71]. Except for toxin retention, patients with CKD have increased gut permeability, allowing more of these toxins to be reabsorbed. Using non-targeted metabolomic mass spectrometry, Wikoff [72] discovered that the existence of gut microbiota is necessary for the presence of certain protein-bound uremic toxins, including phenylacetic acid, hippuric acid, and IS. Aronov [73] analyzed and compared plasma samples from hemodialysis patients with and without colons and demonstrated that in subjects without colons, many solutes were absent or present only in low concentrations, indicating the colonic origin of these molecules. To support the mandatory role of gut microbiota in uremic toxin production, animal studies treated with germ-free mice or antibiotics have demonstrated that Trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO), IS, and PCS cannot be detected in plasma when gut microbiota ecosystems are dysfunctional. PCS, IS and TMAO are typical microbiome-derived uremic toxins [19]. There is substantial evidence that when kidney function declines, these microbial metabolites accumulate in circulation to toxic levels. Vaziri [74] and colleagues observed significant differences in the abundance of 190 bacterial operational taxonomic units (OTUs) between the ESKD and control groups, thus demonstrating substantial changes in the microbiota composition in DKD. Similar to human, diabetic rodent models have shown signs of dysbiosis linked to DKD. At the expense of the relative loss of Bacteroides (B. accifaciens species), Rikenella, and Ruminococcus—the species that make short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs)—and Firmicutes and actinomycetes, respectively, α diversity declined [75]. While the human disease cannot be precisely replicated in animal models, these findings strengthen the validity of experimental models to study the gut–kidney axis in DKD. Instead of conventional but harmful treatments such as drug control, kidney dialysis, and surgery, researchers now prefer to focus on intervention diets and prebiotics to regulate the gut microbiota and its metabolites [76, 77]. In addition, stool samples from healthy individuals or patients with DKD can be transferred to mice that receive or do not receive experimental models of DKD to study the physiology during DKD [78].

Gut microbiota disorder in cardiovascular diseases

CVD mainly include atherosclerosis (AS), ischemic heart disease, heart failure (HF), coronary artery heart disease (CHD) and stroke [79]. To date, cardiovascular disease risk remains an urgent problem for countries around the world due to its high morbidity and mortality [80]. Researchers generally believe that, at a mechanistic level, the effect of the gut microbiota on cardiovascular disease works through a metabolically dependent pathway. TMAO is recognized as a metabolite molecule of the gut microbiota known to increase the risk of cardiovascular disease [81]. TMAO [19, 82, 83] was one of the first gut microbiota metabolites to reveal a potential causal relationship between the gut microbiota and cardiovascular disease, and after consuming dietary components that are plentiful in the Western diet, such as choline, lecithin, carnitine, and l-carnitine, it is a post-organismic metabolite that is generated. Subsequent clinical studies have also found that gut microbiota imbalance is closely related to the occurrence and development of CVD, such as hypertension [84], AS [85], myocardial infarction [86], atrial fibrillation [87] and HF [88]. With the exception of individual literature, most research on CVD have found a decrease in the quantity of gut microbiota and the formation of butyrate, along with a relative rise in the abundance of other oral taxa, such as proteus, opportunistic pathogens, and streptococcus [89]. Coronary atherosclerosis is one of the important turning points in the development of cardiovascular disease. The formation and increase of plaque further aggravate the risk of cardiovascular disease. Still lack of limited evidence that living microbes themselves directly cause plaque formation [90, 91]. In previous research, bacterial DNA with signatures matching the microbiota classified as associated with the disease state was found in atherosclerotic plaques. Moreover, alterations in the microbial composition were verified in patients with multiple cardiovascular disease risk factors, such as insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and other metabolic phenotypes [92]. Apart from changes in the makeup of the gut microbiota, metabolic imbalances within the gut microbiota have also been linked to the onset of CVD. Specifically, TMAO, the liver oxidation product of the microbial metabolite trimethylamine, has attracted much attention as a possible promoter of cardiometabolic disorders and atherosclerosis [93]. Kidney function is especially significant when examining TMAO levels in the systemic circulation as kidney is the primary organs responsible for removing TMAO from circulation. Determining whether microbial changes drive or are driven by disease states is challenging, because changes in microbiota composition, diversity, and abundance are linked [94]. In AS, gut microbiota plays an important role in the dynamic process from plaque formation to unstable fragmentation. The earliest studies date back to the late 1980s [95], the Helsinki heart study revealed a correlation between chlamydia pneumoniae serology and acute myocardial infarction and coronary artery disease [96]. The gut microbiota is a pertinent focus for CVD research, as evidenced by a recent study that discovered similar taxa in gut and atherosclerotic lesions [97]. The association between the gut microbiota and AS was investigated in a large cohort using 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequencing [98, 99] or shotgun sequencing [100, 101]. Based on multi-omics analyses of patients and healthy people, we not only found that the composition of the gut microbiota and metabolites varied significantly with the severity of arterial plaque breakage, but also researchers built a disease classifier based on different levels of microbes and metabolites to distinguish cases from controls, and even to accurately distinguish between stable coronary artery disease and acute coronary syndromes.

Hypertension is the most common modifiable risk factor for cardiovascular disease, but few studies have linked gut microbiota characteristics to human hypertension. Using Dahl rats, Mell [102] compared salt-sensitive and salt-tolerant strains and found significant differences in cecal microbiota. According to studies using germ-free mice given angiotensin II injections, they find the gut microbiota plays a role in angiotensin II-induced vascular dysfunction and hypertension. Because of a rise in the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio and a decrease in microbial richness, diversity, and uniformity, he noticed a substantial ecological imbalance in hypertensive animals whose suggests a connection between coronary AS and the long-term effects of high blood pressure on the vascular system and cardiovascular outcomes [103]. Experimental models of hypertension have shown a direct link among changes in the abundance of gut microbiota, metabolites of gut microbiota, blood pressure levels and blood components [104]. It should be pay more attention to note that individuals with early stage hypertension had gut microbiota compositions that were comparable to untreated hypertensive patients in terms of bacterial richness and diversity [105, 106], but FMT caused hypertension in germ-free mice [107]. These data suggest a strong correlation between dysregulation of gut microbes and hypertension pathology.

In addition to TMAO, lipopolysaccharides (LPS) [108] and bile acids (BA) are also among the major pathogenic metabolites in cardiovascular diseases. Gram-negative bacteria in the gut produce LPS, which can enter the bloodstream and result in low-grade, non-septic endotoxemia. Many studies have demonstrated a correlation between the severity of HF symptoms and a worse prognosis for individuals with compromised gut integrity and elevated blood levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines [109]. LPS is mostly identified by the toll-like receptor [110] (TLR) on the surface of immune cells and can enter the host blood when the gut barrier is compromised. TLR signaling triggers the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines that synchronize the host’s pro-inflammatory state upon attachment to a bacterial ligand. Furthermore, systemic monitoring of LPS concentrations was observed to predict severe cardiac adverse events in patients with atrial fibrillation in a recent observationally research, indicating that endotoxin translocations impact CVD problems [108, 111]. Meanwhile, systemic BA concentrations also predict the development of human coronary artery disease [112]. The metabolism of BA is comparatively intricate. Currently, the consensus is that gut microbiota produces secondary BAs (many of which have hormone-like properties) by hydrolyzing bile saline and dehydroxylating BA 7α. Some secondary BAs also interact with various host nuclear receptors. For instance, host physiology is impacted by interactions between Farnesoid X receptor (FXR), liver X receptor (LXR), pregnant X receptor (PXR), and particular g protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) [113, 114]. At the same time, perturbations in intake from dietary sources, dynamic interactions between gut microbiota and specific BAs may also contribute to cardiometabolic phenotypes and CVD susceptibility [115]. The above discussion highlights that the integration of sterile mouse model development and comprehensive multi-omics studies has provided robust evidence linking the gut microbiota to cardiometabolic and vascular phenotypes in the host.

Interaction of gut microbiota with diabetic complications

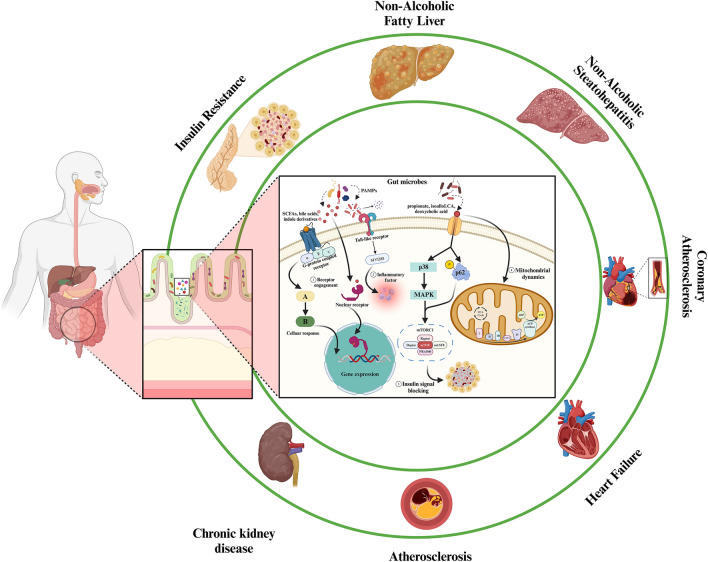

According to above researches and discussion, we can clearly realize that gut microbiota has a profound impact on human body health, which metabolic diseases are particularly at the forefront. The metabolites of gut microbiota source metabolic mechanism cover many organs, that’s mean metabolites can affect the pathophysiological homeostasis of other organs through pathways such as systemic circulation when lesions begin to appear in one organ. We mainly discussed how diabetes caused by abnormal insulin secretion spreads to all organs of the body and then leads to chronic metabolic diseases, such as AS, CHD, NAFLD and DKD (Fig. 2). The focus is to pay more attention to the messenger role of the gut microbiota, analyze the metabolites of the gut microbiota, how these small molecules participate in the metabolic disease process, and clarify whether the gut microbiota and its metabolite small molecules can exist in multidirectional tandem between various organs.

Fig. 2.

Gut microbiota regulates major targets/mechanisms in the human body through signaling metabolites under metabolic disorders. ➀ Membrane anchored receptors, mainly GPCR, detect the vast majority of microbial metabolites (e.g., SCFAs, bile acids, and indole derivatives) and initiate signal transduction and cellular responses. ➁ Endotoxins, lipid cholic acids and peptidoglycans activate TLR through pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) to induce inflammation. ➂ Imidazole propionate is a propionate that impacts insulin signaling by activating p38 MAPK and phosphorylation of p62, resulting in increased mTOR activity. ➃ Certain metabolites, including as propionate, isoalloLCA, and deoxycholic acid, have the ability to alter the dynamic or energetic metabolism of the mitochondria. Created with BioRender.com

From the above discussion, it is evident that structural changes and shifts in the microbiota are closely associated with the occurrence and progression of metabolic diseases, such as T2D and its complications. The relationship between differential metabolites and disease can be twofold: (1) diseases induce alterations in gut microbiome metabolites, which can serve as potential biomarkers for disease diagnosis and (2) gut microbes contribute to disease development through their metabolites, thereby acting as risk factors for certain diseases. In summary, microbiota primarily influences the production of metabolites either directly or indirectly, thereby modulating disease-related molecular indicators and signaling pathways.

Since the gut microbiota has been extensively studied, small-molecule communication mediated by gut microbiota metabolites across organ axes has been a hot topic, emphasizing the important role of small molecules in gut microbiota metabolism mediated organ crosstalk. In addition, the concept also focuses on transporter-centered transport and signaling systems, or the associations between other systems (nervous system, endocrine system). We propose a new opinion about how the gut microbiota and its metabolism mediate this multi-span (organ system, molecular signaling system) organ axis to provide a new direction of exploration. In the next chapter, we will focus on the small molecules of gut origin, and analyze their communication in the multi-scale of gut–liver–kidney–heart.

Reading the research about gut microbiota in recent years, we can find that bidirectional or even multi-directional tandem organ axes such as gut–liver [116], gut–kidney, gut–heart [117], and gut–brain [118] have aroused a lot of attention and reports. However, the correlation about them have not been thoroughly studied. Next, we will elaborate from the above three points: key gut microbial metabolites, gut barrier theory and evidences in the development process of clinical research.

Gut microbiota metabolites

Gut microbial metabolites include BAs, SCFAs, branched-chain amino acids, TMAO, tryptophan, indole derivatives, LPS and imidazole propionate [119]. Among them, SCFAs, LPS and TMAO have been widely studied. These small metabolic molecules serve as a medium of crosstalk between different organs and intestinal. At the same time, after a lot of summary and screening, metabolites themselves also act as signaling molecules in various organs to regulate the homeostasis of the host environment. Table 1 summarizes the changes and roles of small molecules in gut microbiota metabolism in metabolic diseases (Table 1 summarizes changes in gut microbiota in metabolic diseases).

Table 1.

Changes in gut microbiota and its metabolites in metabolic diseases and examples of their role in disease

| Disease | Microbiota | Metabolites | Level in patients | Biologic function | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Up-regulated | Down-regulated | ||||

| T2D | Escherichia col | Eubacterium | Imidazole | Decrease [138] | Insulin resistance [139] |

|

Clostridium Bacteroides Eggerthella [120] |

Clostridiales SS3/4 Faecalibacterium |

Butyrate SCFAs |

Pancreatic β-cell dysfunction Inducing inflammation [50] |

||

| AS |

Chryseomona Proteobacteria Klebsiella spp. Ruminococcus |

F. prausnitzi R. intestinalis Prevotella copri |

TMA/TMAO | Increase [109] |

Increased blood press and vasoconstriction [140] |

| Streptococcus spp. [123] | Alistipes shahi [124] | SCFAs | Decrease [141] |

Blocking cholesterol synthesis [142] Reducing vascular inflammation [143] |

|

| NAFLD |

Klebsiella pneumoniae Proteobacteria Enterobacteriaceae [125] |

Roseburia F. prausnitzii Rikenellaceae |

SCFAs LPS |

Increase [45] |

Gut permea [144] Inducing inflammation [145] |

| CKD |

Clostridium Roseburia F. prausnitzii Proteobacteria [128] |

Ruminococcus spp. Alistipes spp. Fusobacterium spp. [129] |

Indoxyl P-Cresol BA |

Increase [138] |

Oxidative stress [146] Mitochondrial damage [147] |

| Obesity |

Lactobacillus Fusobacterium F. prausnitzi [130] |

Faecalibacterium Akkermansia Alistipes [131, 132] | SCFAs | Decrease [148] | Exacerbating obesity manifestations [149] |

| Hypertension |

Klebsiella Clostridium |

Bacteroides Roseburia |

TMA/TMAO | Increase [140] |

Increased blood press and vasoconstriction [140] |

|

Streptococcus Dysgonomonas Eggerthella Salmonella [133] |

Faecalibacterium [134] |

SCFAs BA |

Decrease [84] |

Lower blood press Vasodilation and anti-inflammatory [150] |

|

| HF |

Bacteroides Prevotellain Eubacterium rectale |

Ruminococcaceae Coriobacteriaceae [137] |

TMA/TMAO | Increase [151] | Increased risk of thrombosis, AS, stroke, myocardial infarction [152] |

| F. prausnitzii [135, 136] | SCFAs | Decrease [153] | Maintain gut barrier, anti-inflammatory roperties [154] | ||

From Table 1, we can find that the same metabolite may be involved in one or more diseases through different pathways. We focus on SCFAs, which have been several reports on the beneficial effects of SCFAs in NAFLD, AS, hypertension and other diseases [155]. SCFAs act as a signaling molecule on gut cells and other tissue cells which can bind to four receptors to trigger intracellular signaling cascade. They are free fatty acid Receptor 3 (FFAR3), free fatty acid receptor 2 (FFAR2), G protein-coupled receptor 109a (GPR109a) [156] and G protein-coupled receptor 42 (GPR42) [157]. Furthermore, SCFAs activate specific targets through blood circulation, systemic circulation and other pathways, such as AMP-activated protein kinases in the liver (and maybe the heart), which promotes lipid oxidation and enhances glucose homeostasis in mice [158].

LPS is widely circulated through the portal vein circulation, blood circulation and other pathways. In the disease state, the level of LPS increase and translocation occurs, and it can alter gut permeability in various circulatory processes, and even the ability of cell membranes or biological barriers such as entero-liver, heart–kidney to allow small molecules to pass through [159]. Tryptophan, a class of aromatic receptor complex, is a precursor to several important metabolites, including tryptophan, which is converted into indole derivatives by gut microbes. According to recent clinical studies, the ability of the microbiome to metabolize tryptophan into aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) agonists is reduced in metabolic disorders. In addition, defective activation of the AhR pathway results in reduced production of glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and interleukin-22 (IL-22) [160], which in turn causes gut permeability and lipopolysaccharide translocation, ultimately causing inflammation, insulin resistance, and hepatic steatosis. Then, we elaborate on BAs and LPS to analyze the interaction between metabolites to influence the development of the disease. Colonic bacteria can metabolize apocholic acids (such as chenodeoxycholic acid and cholic acid) to produce secondary BAs (mainly stone cholic acid and ursodeoxycholic acid), which are the most abundant metabolites in the gut microbiota. Through a number of receptors, the most significant of which is the FXR, secondary BAs regulate inflammation and metabolism in addition to playing a critical function in stabilizing lipids to improve gut absorption. Regulation of the gut microbiota–BAs–FXR axis is associated with insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis induced by obesity in mice [161]. What’s more significant, disruption in the microbiota observed in cases of cardiac insufficiency leading to changes in the ratio of these two BAs [162]. FXR agonists reduce inflammation by inhibiting the nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) light chain enhancer that activates the B-cell nuclear receptor, and the role of NF-κB in regulating inflammation is independent of other cardiac hypertrophy factors. To further limit the spread of LPS in the host body circulation, ursodeoxycholic acid has the ability to produce micelles that bind to the particle. Through the above research results, we found that the bear to oxygen cholic acid is expected to be developed as a potential metabolite for the treatment of HF [163].

Through the above analysis, it can be clearly found that different metabolites have a certain correlation, they may combine with each other to play a new role, or they may directly or indirectly regulate each other to play the activation or inhibition function. In the next section, we will discuss the potential ways in which metabolites of the gut microbiota are regulated in human living organisms and how they reach the various organs of the body to perform their functions, and discuss whether there are limitations and new metabolic ways to further modify them to allow them to pass through barriers.

Gut barrier theory

All the organic organisms have many natural barriers to protect the balance of material exchange in their bodies and in their bodies. For example, plants have cell walls and gut microbiota have their own biological barriers, while mammals are more complex and form many defense mechanisms and barriers through the connectivity of organs and systems, such as blood–brain barrier and immune barrier. The gut act as a bridge between humans and the external environment, it is particularly important to maintain the ecological stability of the gut microbiota.

Virtually all of our body parts are colonized by a variety of microbes, suggesting a different type of crosstalk between microbes and microbial metabolites and our organs. In recent years, researches in metabolic diseases and gut microbiota have made it clear that gut bacterial communities play an important role in the regulation of multiple aspects of metabolic disorders [164]. This regulation depends on the microbiome producing multiple metabolites and their interactions with host cell receptors that can activate or inhibit signaling pathways, both beneficial and harmful to the health of the host. With the development and replacement of molecular technological tools (metagenomes, metabolomes, lipids, transcriptomes), the complex interactions that occur between hosts and different microorganisms and their metabolites are gradually being deciphered. Widely studied metabolites such as TMAO and SCFAs just have only analysis their molecular participants and their specific receptors, but the way in which they exist in various organs and circulate through various systems has not been specifically explained. At present, T2D is mostly due to improper management and control of diet and weight. Excessive intake of diets high in fat and sugar, or the Western diet prevalent in today’s society, are independent factors of daily lifestyle habits prone to metabolic diseases. Therefore, metabolic diseases are the ecological imbalance between the external environment and the gut microbiota, and then destroy the first protective barrier of the gut environmental homeostasis. Various metabolites of the gut microbiota flow into the blood circulation and are transported to various organs. Patients with NAFLD, AS, HF and CKD often have high levels of inflammatory factors detected [165]. As mentioned above, LPS changes gut permeability and floods into the host circulation in the disease state, and their next target is immune cells. TLR receptor is widely found in immune cells, and it is also one of the important binding ligands of LPS. Overactivation of TLR can cause immunological homeostasis to be disrupted, and persistent release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines can raise the risk of inflammatory and autoimmune illnesses, as a results, the inflammatory response is required to eradicate infection. The accumulation of metabolic endotoxemia is attributed to increased gut permeability resulting from a high-fat diet and weight gain, which in turn elevates the levels of circulating plasma LPS throughout the body [166]. This is the second defense barrier of gut homeostasis. At present, more and more clinical studies have shown that kidney diseases led by CKD can aggravate the accumulation of urinary toxins into the host heart through systemic circulation to form cardiac toxins [167]. In patients with ER or renal failure after kidney transplantation, uremic toxin levels were significantly reduced compared with hemodialysis [168], and it also effectively reversed cardiac fibrosis, arterial stiffness [169], improved remodeling and cardiovascular reserve, and greatly reduced the risk of CVD. This suggests that the metabolism of the kidney is closely related to the heart. Uremic toxins are one of the most readily accumulated metabolic endotoxins, which are often categorized as free water-soluble low-molecular-weight solutes, protein-bound (PB) uremic toxins, or intermediate compounds based on physicochemical properties that dictate their response to standard hemodialysis. Some of these metabolites are uremic toxins that are detected by clinical indicators, such as PB uremic toxins [170] indolyl sulfate (IxS), indolyl acetic acid (IAA), pCS, p-formylglucuronic acid (pCG), and TMAO. TMAO that another uremic toxin associated with cardiovascular disease in the general population, whose levels are also found to be elevated in patients with CKD [82]. Daily diet and gut microbial metabolism are the source of these urinary toxins [171]. When renal function is abnormal, the accumulation of tryptophan metabolites (IxS, IAA, pCS) is due to gut dysbiosis, altered enzyme activity, and low excretion efficiency of the kidney leading to the metabolism and accumulation of tryptophan in the intestine. Therefore, the activation of Ahr in diabetic nephropathy [172] patients will be impaired due to the accumulation of tryptophan metabolites that cannot be metabolized by gut microbiota into Ahr agonists, and further lead to inflammation caused by LPS translocation, hepatic steatosis, etc. As mentioned above, tryptophan metabolism is related to the activation mechanism of Ahr. These will contribute to the disturbance of gut homeostasis, damage to the gut barrier, and further lead to the flow of urine toxins into the heart. Although there is some phenotypic overlap in the CVD spectrum between the general population and patients with CKD, there are significant differences due to the specific cardiac and vascular toxicity of TMAO [173], IxS [174], IAA [175], pCS and pCG. By analyzing the selective metabolism of metabolites of gut microflora in the gut–heart–kidney axis, specific molecules are produced, and each molecule flows into different organs according to the hierarchy to regulate or bind to corresponding receptors to play a role, we can find that the third barrier is a molecular barrier with high selectivity and specificity. Because of this characteristic, it provides more theoretical support for my conjecture that there are certain predictable biomarkers in the progression of diabetes to complications. Actually, not only are there specific differences in CVD between CKD patients and healthy people or patients with other metabolic diseases, we can also see similar conclusions in liver disease. Low systemic inflammation [176] is considered to be the main inducible factor of CKD and NAFLD, but there are many reasons for promoting low inflammation, such as the integrity of gut microbiota and gut homeostasis mentioned above, chronic low systemic inflammation induced by diabetes or other metabolic diseases, and even multiple factors. Remarkably, systemic levels of enteric-derived uremic toxins are significantly influenced by the liver. The hepatocyte cytochrome P450 enzyme was expressed more when exposed to IxS, indicating that enteric uremic toxins control liver metabolism [177]. In addition, as we mentioned above, liver diseases such as fatty liver, NAFLD and NASH are associated with dysregulation of SCFAs metabolism in the gut microbiota. By sequencing 16S ribosomal RNA gene in V3–V4 region and analyzing SCFA levels in feces of 32 patients with NAFLD/NASH [178], high SCFA levels and SCFA-producing bacteria were found in feces. In these patients, the modifications associated favorably with the advancement of their diseases. Similar to tryptophan, sodium butyrate [179] also disrupts the integrity of the gut barrier by activating the Ahr pathway, but it can also indirectly affect the integrity of the barrier by regulating Ahr-dependent gene expression. The breakdown of epithelial tight junctions is induced by CKD-associated uremia, and gut permeability and bacterial translocation are increased by urinary toxins, which results in gut barrier dysfunction, and alterations in the composition and function of the gut microbiota can impact gut barrier function, resulting in endotoxin or bacterial DNA leakage into the bloodstream. This is comparable to the entero–cardio-renal axis-described flow of urine toxins.

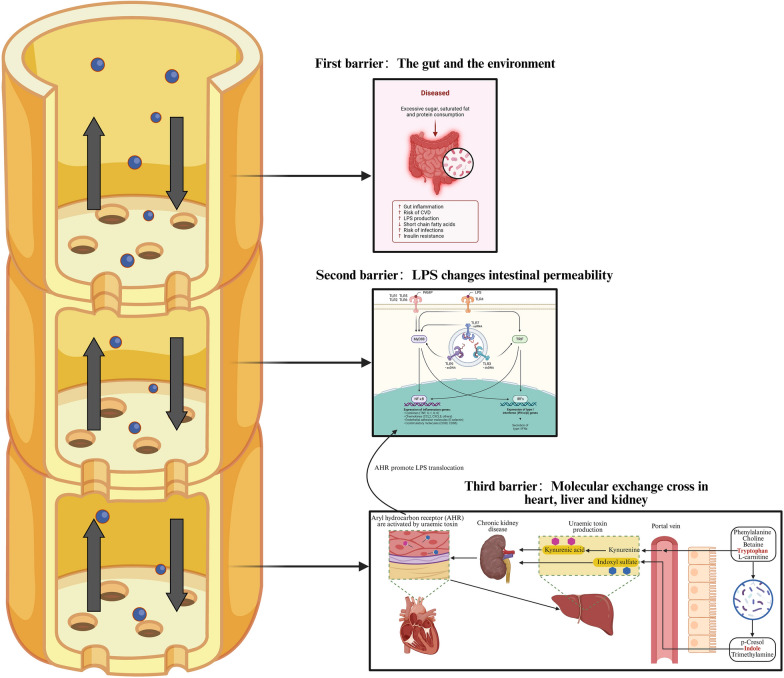

Through the analysis of two organ axes in different directions, we can find that the gut microbiota has an inter-related role in a variety of metabolic diseases, but also plays a “protagonist” in a specific disease. What plays a role is the various barrier levels in the human body, which regulate the metabolism of the gut microbiota through the surface receptors or signaling pathways, filtering metabolites at different stages layer by layer until they are expressed in the corresponding organs under specific pathological conditions (Fig. 3). Our aim is to establish a clear definition of the complications related to metabolic diseases, including diabetes, by analyzing the differences and screening specific and unique targeted metabolite molecules as detection indicators, so as to facilitate the management of diabetes patients and make early warning reports and preventive measures.

Fig. 3.

Importance of the three key barriers in maintaining the ecological balance of the intestine for the flow of metabolite signaling molecules and the regulation of the body

The metabolites produced by the gut microbiota flow to the various organs of the body as signaling molecules, just as a plant undergoes photosynthesis or gets nutrients from the soil, and are then sifted through layers of special organ “vessel” in the rhizomes to carry the nutrients to the various organs. First barrier: As an organ in direct contact with external sources such as food, the gut itself is a natural barrier. It can effectively prevent most harmful substances from flowing into the body. Second barrier: when the human body takes in too much lipids and sugar, it will often promote the occurrence of metabolic disorders, resulting in gut inflammation, increased risk of CVD, insulin resistance and the accumulation of harmful substances such as LPS. Then, due to the buildup of LPS, the harmful bacteria begin to activate effector molecules, known as PAMP. At this time, LPS will bind extensively to various TLR receptor phenotypes to initiate signaling, such as classical inflammatory pathways such as NF-кB and IRFs to activate IFN interferon expression; Third barrier: Dietary breakdown products such as phenylalanine, choline, tryptophan, and levocarnitine are metabolized by gut microbiota into well-known uremic cardiotoxins/nephrotoxins (p-cresol, indole, and trimethylamine) and uremic toxins such as indoleacetic acid precursors. Indole is converted to indole solutes in the liver, such as indole sulfate. The liver can also metabolize tryptophan that enters through the portal vein to create kynurenine. Kynurenine and indoxyl sulfate are regarded as uremic poisons. Although the kidneys normally eliminate them, those with CKD retain them. Patients with CKD have elevated levels of these uremic toxins, which activate aromatics receptors (AHR) and allow the toxic uremic toxins to enter the heart and cause myocarditis, HF, and an increased risk of cardiovascular disease. In addition, these uremic toxins can be re-injected back into the liver through the portal vein circulation. Created with BioRender.com.

Relevance of precision prevention of diabetic complications

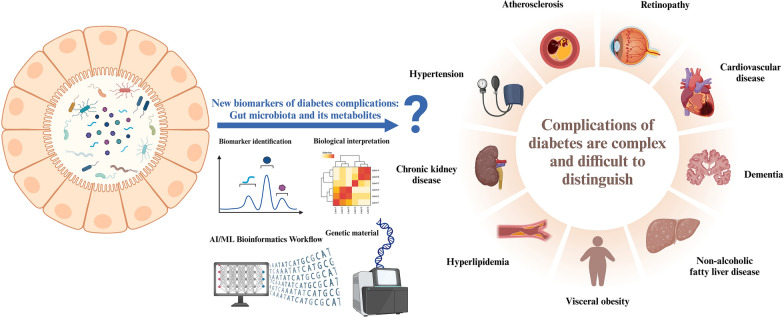

The current global mismanagement of diabetes and its complications remain a serious health challenge. As for the central problem that prediabetes is easily induced into complications of other metabolic diseases, the current common detection methods are not targeted to predict the key problem. In this review, we have repeatedly emphasized that metabolic diseases affect and promote each other, which makes them difficult to be detected and ignored in the early stage. As the current diabetes epidemiology [180] is calling for, diabetes itself is not terrible, but the terrible thing is that people often do not pay attention to it, resulting in improper self-management of diabetes, such as CVD, diabetes nephropathy and other subsequent serious and difficult to control the mixture of multiple diseases of metabolic diseases. Therefore, the search for new biomarkers and the development of new assays are top priority responses (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Characterization of gut microbiota and its metabolites as novel biomolecules

Self-management of diabetes and its complications is an increasingly serious public health problem. At present, there are no accurate biomarkers that can be used as early warning signal molecules for diabetes complications, and there are no effective diagnostic means. Gut microbiota and metabolites are a hot topic in the biomolecular community in the twenty-first century, but whether they can be used as new biomarkers for diabetic complications remains to be deciphered by many scholars. Created with BioRender.com.

Up to now, many studies have demonstrated that the gut microbiota plays a crucial role in maintaining host physiological functions with the help of metabolomics. In addition, a combination of metagenomics and metabolomics [181, 182] has been used to elucidate the link between gut microbiota imbalances and metabolic disorders. Since the research is still in the initial stage, it might be challenging to identify which metabolites are only produced by the microbiome or whether other factors, such as the host's diet or environment, are also involved. However, it is undeniable that metabolites derived from the gut microbiota play a central role in the physiology and pathology of metabolic diseases. The following is a summary of past studies, hoping to provide constructive help for the search for biomarkers for the type management of diabetes complications and the development of novel therapeutic tools for metabolic disorders.

Evidence from clinical data analysis

In the current available studies, we can find that changes in the composition of the gut microbiota and its source metabolites are associated with various features observed in metabolic disorders. Despite some contradictory results, all current researchers in this field agree that metabolic disorders begin with a reduction in the ratio of Bacteroidetes to Firmicutes. However, the mechanism of metabolite regulation is relatively complex, and it is a dynamic process. With the development of diseases, the gut microbiota will be affected, thus affecting the regulation process of metabolites. Postprandial endotoxemia has been linked to the development of T2D as early as 2019, according to studies conducted by Postprandial triglyceridemia-associated endotoxemia may occur several years before the diagnosis of diabetes, according to the Coronary Diet Intervention with Olive Oil and Cardiovascular Prevention study (CORDIOPREV), which also examined whether longitudinal fasting and postprandial measurements of LPS and LPS-binding protein (LBP) can improve the prediction of T2D incidence [183]. The underlying mechanism may be related to the transcellular mechanism, a systemic circulatory pathway of LPS, which involves the internalization of LPS by intestinal epithelial cells (IEC) through the apical surface and the transport of LPS to the Golgi apparatus for further incorporation into chylomicrons, the formation of which promotes gut absorption of LPS [184]. In the beginning, it was believed that high amounts of LBP inhibited cell absorption of LPS, whereas low concentrations enhanced it. Expansion of LBP appears to be linked to a higher risk of bacterial infection as well as immunological and hemodynamic abnormalities, according to additional research [185], i.e., changes in the gut barrier prior to the development of T2D, possibly due to changes in the gut microbiota, as demonstrated by LBP plasma levels, which increase gut absorption of LPS, followed by increased plasma levels of TNF-a. The CORDIOPREV trial also performed a secondary correction analysis in a subgroup of patients with acute myocardial infarction who did not have T2D at baseline. The findings of this study confirmed the previous finding that in patients with acute myocardial infarction, dietary endotoxemia is elevated prior to the onset of T2D.

Increasing evidence demonstrates that higher TMAO levels have been reported in people with diabetes [186] and obesity [187], as well as in people with CKD or kidney failure. TMAO is an independent risk factor for confirmed cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in patients with established IHD [188] or CKD [189] with accumulating evidence suggesting direct causal relationship [190]. Andrikopoulos et al. examined TMAO in MetaCardis [191] study participants and concluded that, regardless of disease stage, reduced glomerular filtration rate (GFR) is the primary regulator of circulating TMAO. It then further negatively affects kidney function by promoting renal fibrosis in combination with established pathophysiology (i.e., induced by metabolic diseases, such as diabetes or cardiovascular disease). In addition, their preclinical work also found that TMAO initiated the conversion of kidney fibroblasts into myofibroblasts and led to renal fibrosis, which was unrelated to the underlying cause that significantly contributed to eGFR decline [192]. However, pro-fibrotic signaling in the form of TGF-β1 activation is a previously identified pathological condition that must work in concert with TMAO damage in order to convert kidney fibroblasts into myofibroblasts. Some studies have discovered that IxS activates the tubule TGF-β1 production by activating p53, which in turn activates Smad3, a key regulator of the TGF-β/Smad3 signaling pathway in kidney fibrosis (suppressor of mothers against decapentaplegic [193]. Therefore, when the pathological elevation of TMAO is detected in diabetic state, we can combine the classical detection indicators corresponding to CKD, AS and other diseases to predict or confirm the type of diabetes. It is worth noting that in metabolic diseases, various organs and endocrine systems interfere with each other, so the selection of subsequent detection indicators is extremely important after the abnormal increase or decrease of metabolite levels caused by gut microbiota metabolic disorders are detected in the early stage.

In recently clinical studies, Guo [194] et al. first discovered that while three CPGS in HIF3A's intron 1 (CpG 6, CpG 7, and CpG 11) were substantially methylated in diabetic cardiomyopathy (DCM) patients, there were reductions in plasma butyric acid levels and HIF3A mRNA expression in these patients. As an inhibitor of histone deacetylase (HDACi), butyric acid is essential for controlling gene expression and DNA methylation. The “microbe–myocardium” axis and host–microbial interactions may have a role in the pathophysiology of DCM, as suggested by the recent correlation found between plasma butyric acid levels and intron 1 methylation of HIF3A at CpG 6. The microbe–myocardium axis was proposed and summarized in detail by Bastin [158] as early as 2020, and the organ concatenation theory has been described previously (such as gut–liver concatenation, heart–kidney concatenation, etc.). This provides a reference for us to find the next follow-up detection indicators. For example, as screening tools and combination biomarkers, doctors might use plasma butyric acid levels and intron 1 methylation of HIF3A at CpG 6 to potentially separate individuals with DCM from those with T2D. A better indicator of tryptophan catabolism than kynurenine concentration alone is the tryptophan ratio. In addition to being recognized as an endothellar-derived vasodilator [195], kynurenic acid and xanthuric acid, two of its downstream intermediates, have also been linked in animal models to the etiology of T2D. In addition, several plasma metabolites of the kynurenine pathway [196] are associated with insulin resistance. In a large prospective cohort study of patients with suspected or CVD [197], researchers found that KTR was a strong predictor of T2D. In another cross-sectional study, plasma KTR was elevated in patients with T2D and higher in patients with DKD compared to healthy individuals. From the physiological mechanism level, as described above in the association of nephrotoxins and cardiac toxins, the increased excretion of renal kynurenine may have adverse effects on kidney and systemic vascular function. This may partly explain the strong prognostic information [198] associated with urinary KTR and T2D as well as CVD in the current study. Increasingly, intestinal microbes and their metabolites are being explored for their therapeutic potential through the study of the gut microbiome and host health. In this context, investigators collected stool samples from T2D patients across two independent centers and observed a significantly reduced abundance of B. intestinihominis. Utilizing 16S rRNA gene sequencing and metagenomic sequencing analyses, researchers compared the gut microbiota composition between healthy individuals and T2D patients. In addition, metabolomics, transcriptomics, and other technologies were employed to elucidate the mechanisms underlying the therapeutic effects of B. intestinihominis (referred to as LBI in some contexts). This study highlights the potential of B. intestinihominis as a promising probiotic candidate [199]. It is widely recognized in drug research that certain medications are only effective in a subset of patients, often resulting in suboptimal clinical outcomes. Recent studies on gut microbiota have revealed that these microbes can interact with drugs. Specifically, alterations in gut microbial composition and the metabolic activities of intestinal microbes can modulate drug activity, thereby influencing the ultimate therapeutic efficacy [200]. For example, TMAO, as described above, is a risk metabolite for cardiovascular disease and thus holds therapeutic significance [201]. The gut microbial genus Bilophila has been shown to metabolize trimethylamine (TMA), leading to a reduction in TMAO levels. This suggests that variations in TMA-metabolizing gut bacteria among individuals can result in different therapeutic outcomes, and that replacing these specific bacteria may mitigate TMAO-related risks. In addition to targeting gut microbes directly, another potential strategy is to target metabolites that influence drug efficacy. For example, metformin is the primary medication used to treat T2DM. However, in some patients, the reduction in blood glucose levels is not significant. Studies have demonstrated that these patients often exhibit high levels of the gut microbiota metabolite imidazole propionate. Mouse models have further shown that imidazole propionate produced by gut microbes can impair the glucose-lowering effects of metformin [202]. Recently, the study of physiological activity of inulin propionate by Chambers et al. showed that supplementation with 20 g/day prebiotics significantly improved insulin sensitivity and systemic inflammatory markers compared with a control group supplemented with cellulose. Interestingly, this effect was associated with elevated fecal propionate concentrations, further highlighting the important role of SCFA in mediating the insulinosensitizing effects of prebiotics [203].

Systems biology: artificial intelligence assisted multi-omics data integration

The generation and integration of functional omics readings derived from meta-omic and metabolomics analyses enable a detailed functional assessment of the human gut microbiome and its metabolites. Compared to the information content of 16S rRNA, metagenomics, and transcriptomics, functional genomics shows greater variability and sensitivity to perturbation. Therefore, functional genomics is anticipated to more accurately delineate health and disease states [204–206]. Despite the rapid advancement of omics technologies offering valuable insights, several limitations remain, primarily categorized into three aspects:

Limitations of omics in microbiome research

Functional redundancy within the healthy human microbiome Functional redundancy can confer resilience and stabilize ecosystem function during perturbations, which is generally associated with stability and health in the human microbiome [207]. However, unlike other microbial ecosystems, the relationship between functional redundancy and stability remains unexplored in the human gut microbiome [208].

Unknown taxa and functions A major challenge in microbiome research is the presence of unknown taxa and functions. The ill-defined anatomical origin of the microbiome (e.g., gut contents, feces, oral cavity, skin) can introduce significant random variation. In many recent studies, genes from uncultured taxa or with no known function were omitted during metagenomic data analysis due to reliance on annotated reference genomes. These approaches are inefficient, may introduce bias, and fail to account for horizontally transferred functions and strain-specific functional gene complements that constitute the taxonomy-specific pangenome [209]. Similarly, collections of orthologous groups and protein families with no known function have been established to facilitate cross-sample comparisons [210], aiding in the identification of biologically meaningful entities.

Dynamics of community function Another critical question is whether ecosystem functioning, independent of or in addition to specific microbial functions, contributes to human health and whether generalizable patterns can be discerned from multi-omics data [211].

Potential of AI-based omics integration

Artificial intelligence (AI)-based omics integration represents a transformative advance that can significantly enhance our ability to analyze and interpret complex biological data. Advanced computational and statistical methods, particularly interpretable machine learning, can help identify key microbial and metabolic signatures associated with clinical phenotypes while addressing the limitations described above.

Pattern recognition and prediction: Autonomous machine learning and deep learning capabilities enable AI to identify specific patterns in multidimensional data, allowing prediction of therapeutic responses or disease progression based on historical data. For example, one study constructed a noninvasive microbiome-based diagnostic model for active Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis using random forest classifiers across eight different populations. Meanwhile, AI has been successfully applied in clinical trials for endoscopy in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), including computer-aided detection (e.g., polyp detection), diagnosis (e.g., polyp classification), and improvement (e.g., scoring bowel preparation) [212].

Data management and analysis: Machine learning can address the inherent missing structure in microbiome data sets, improving research efficiency and reducing uncertainty. For example, recent studies have demonstrated the need for supervised machine learning methods to detect relevant patterns in samples due to the lack of strong internal organization in microbiome data [213]. Another study showed how interpretable machine learning can identify bacterial taxa most associated with T2DM, bridging the gap between statistical modeling and biological insight [214].

Conclusion and future perspective

Although various current research results and evidence have shown that various metabolic diseases, including diabetes, are closely related to gut microbiota and its metabolites, the in-depth mechanism has not yet been fully explained. For example, as proposed in this paper, whether the metabolites of gut microbiota can connect the upstream and downstream signaling molecules affected or regulated by it, target proteins and receptors are emerging methods of diabetes diagnosis and classification management.

(1) Key findings on microbiota’s role in T2D and related complications: in summary, we describe in detail the important role of the gut microbiota and its metabolites in T2D and its complications also summarize some important and widely studied potential molecular mechanisms of metabolites in the host. Meanwhile, we have also compiled articles on indicator observations in clinical studies, which also means that metabolites as targeted predictors are on the agenda. At the same time, the search and detection of metabolites may benefit from the increasingly intelligent and efficient methods of metabolomic database identification of metabolites, such as the global network optimization method NetID [215]. The diversity in metabolic output within a class or within a single metabolite group is a challenging issue in the study of host–microbe interactions, particularly in the human body. (2) Current deficiencies: the development of host sensors and receptors for gut microbial metabolites is still in its infancy, with significant gaps remaining before translation to clinical treatment and prediction can be achieved. This is particularly evident given our limited understanding of the interactions between signaling metabolite-targeting groups and host pathology. Meanwhile, the thousands of metabolites produced by the gut microbiota naturally regulate the body's sensors and targets. (3) Future research and clinical implementation: future research may concentrate more on metabolite composition and proportions in clinical patients, since microbial metabolites affect signal transduction in a coordinated manner, which is the organ crosstalk theory reviewed in this paper. We believe that the study of the impact of metabolites on patients also needs to monitor metabolites in different tissues, which will be an important perspective of metabolomics research. Therefore, we propose that it is not only possible to detect the change of a single metabolite concentration index and the commonly monitored indicator data, such as total cholesterol, LDL, HDL, triglycerides, HbA1c, serum creatinine, urine creatinine, urine albumin to make diagnosis, which will enable more precise management of diabetes complications.

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to our colleagues and mentors, past and present, for continuous discussions. Figures were created with BioRender.com, so we are grateful for the site.

Abbreviations

- T2D

T2D

- DKD

Diabetic kidney disease

- NAFLD

Non-alcoholic liver disease

- PAMPs

Pathogen-associated molecular patterns

- FMT

Fecal microbiota transplantation

- FVT

Fecal viral transfer

- ESRD

End-stage renal disease

- CVD

Cardiovascular disease

- CKD

Chronic kidney disease

- PCS

P-cresol sulfate

- IS

Indole sulfate

- TMAO

Trimethylamine N-oxide

- OTUs

Operational taxonomic units

- SCFAs

Short-chain fatty acids

- AS

Atherosclerosis

- HF

Heart failure

- CHD

Coronary artery heart disease

- LPS

Lipopolysaccharides

- BA

Bile acids

- TLR

The toll-like receptor

- FXR

Farnesoid X receptor

- LXR

Liver X receptor

- PXR

Pregnant X receptor

- GPCR

G protein-coupled receptor

- FFAR3

Free fatty acid Receptor 3

- FFAR2

Free fatty acid receptor 2

- GPR109a

G protein-coupled receptor 109a

- GPR42

G protein-coupled receptor 42

- Ahr

Aryl hydrocarbon receptor

- GLP-1

Glucagon-like peptide-1

- IL-22

Interleukin-22

- NF-κB

Nuclear factor-κB NF-κB

- PB

Protein-bound

- IxS

Indolyl sulfate

- IAA

Indolyl acetic acid

- PCG

P-formylglucuronic acid

- AHR

Activate aromatics receptors

- CORDIOPREV

Cardiovascular Prevention study

- LBP

LPS-binding protein

- IEC

Intestinal epithelial cells

- GFR

Glomerular filtration rate

- DCM

Diabetic cardiomyopathy

- HDACi

Inhibitor of histone deacetylase

- AI

Artificial intelligence

Author contributions

KLW: Methodology, Conceptualization, Writing—Original Draft, Revised draft, Visualization, and created graphic illustrations. YX: Revised draft. TJZ, Revised draft. YLB, Supervision, Final Revisions. MLY: Methodology, Conceptualization, Supervision; Project administration, Funding acquisition, and Final Revisions. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82304481 to M. Y). Guangzhou Science and Technology Bureau (SL2024A04J00652 to M. Y).

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Manuscript does not report on or involve the use of any animal or human data or tissue. Ethics report certification is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Consent for publication

Personal privacy informed report is not applicable to this article as no contain data from any individual person.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Yunlong Bai, Email: ylbai@gzucm.edu.cn.

Meiling Yan, Email: yanmeiling0122@gdpu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Collaboration NCDRF. Worldwide trends in diabetes since. a pooled analysis of 751 population-based studies with 4.4 million participants. Lancet. 1980;2016(387):1513–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kolb H, Martin S. Environmental/lifestyle factors in the pathogenesis and prevention of T2D. BMC Med. 2017;15:131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ling C, Groop L. Epigenetics: a molecular link between environmental factors and T2D. Diabetes. 2009;58:2718–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scott LJ, Mohlke KL, Bonnycastle LL, Willer CJ, Li Y, Duren WL, et al. A genome-wide association study of T2D in Finns detects multiple susceptibility variants. Science. 2007;316:1341–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Magliano DJ, Islam RM, Barr ELM, Gregg EW, Pavkov ME, Harding JL, et al. Trends in incidence of total or T2D: systematic review. BMJ. 2019;366: l5003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ogurtsova K, Guariguata L, Barengo NC, Ruiz PL, Sacre JW, Karuranga S, et al. IDF diabetes Atlas: global estimates of undiagnosed diabetes in adults for 2021. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2022;183:109118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saltiel AR. New perspectives into the molecular pathogenesis and treatment of T2D. Cell. 2001;104:517–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tabak AG, Herder C, Rathmann W, Brunner EJ, Kivimaki M. Prediabetes: a high-risk state for diabetes development. Lancet. 2012;379:2279–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Demir S, Nawroth PP, Herzig S, Ekim UB. Emerging targets in T2D and diabetic complications. Adv Sci. 2021;8: e2100275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barrera-Chimal J, Lima-Posada I, Bakris GL, Jaisser F. Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists in diabetic kidney disease—mechanistic and therapeutic effects. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2022;18:56–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tan Y, Zhang Z, Zheng C, Wintergerst KA, Keller BB, Cai L. Mechanisms of diabetic cardiomyopathy and potential therapeutic strategies: preclinical and clinical evidence. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2020;17:585–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.International Hypoglycaemia Study G. Hypoglycaemia cardiovascular disease, and mortality in diabetes: epidemiology, pathogenesis, and management. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019;7:385–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jensen TS, Karlsson P, Gylfadottir SS, Andersen ST, Bennett DL, Tankisi H, et al. Painful and non-painful diabetic neuropathy, diagnostic challenges and implications for future management. Brain. 2021;144:1632–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Little K, Llorian-Salvador M, Scullion S, Hernandez C, Simo-Servat O, Del Marco A, et al. Common pathways in dementia and diabetic retinopathy: understanding the mechanisms of diabetes-related cognitive decline. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2022;33:50–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumar V, Agrawal R, Pandey A, Kopf S, Hoeffgen M, Kaymak S, et al. Compromised DNA repair is responsible for diabetes-associated fibrosis. EMBO J. 2020;39: e103477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fan Y, Pedersen O. Gut microbiota in human metabolic health and disease. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2021;19:55–71. 10.1038/s41579-020-0433-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qin J, Li Y, Cai Z, Li S, Zhu J, Zhang F, et al. A metagenome-wide association study of gut microbiota in T2D. Nature. 2012;490:55–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qin N, Yang F, Li A, Prifti E, Chen Y, Shao L, et al. Alterations of the human gut microbiome in liver cirrhosis. Nature. 2014;513:59–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koeth RA, Wang Z, Levison BS, Buffa JA, Org E, Sheehy BT, et al. Gut microbiota metabolism of L-carnitine, a nutrient in red meat, promotes atherosclerosis. Nat Med. 2013;19:576–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Allin KH, Tremaroli V, Caesar R, Jensen BAH, Damgaard MTF, Bahl MI, et al. Aberrant gut microbiota in individuals with prediabetes. Diabetologia. 2018;61:810–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qin J, Li R, Raes J, Arumugam M, Burgdorf KS, Manichanh C, et al. A human gut microbial gene catalogue established by metagenomic sequencing. Nature. 2010;464:59–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pedersen HK, Gudmundsdottir V, Nielsen HB, Hyotylainen T, Nielsen T, Jensen BA, et al. Human gut microbes impact host serum metabolome and insulin sensitivity. Nature. 2016;535:376–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pedersen HK, Forslund SK, Gudmundsdottir V, Petersen AO, Hildebrand F, Hyotylainen T, et al. A computational framework to integrate high-throughput “-omics” datasets for the identification of potential mechanistic links. Nat Protoc. 2018;13:2781–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhong H, Ren H, Lu Y, Fang C, Hou G, Yang Z, et al. Distinct gut metagenomics and metaproteomics signatures in prediabetics and treatment-naive type 2 diabetics. EBioMedicine. 2019;47:373–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Everard A, Belzer C, Geurts L, Ouwerkerk JP, Druart C, Bindels LB, et al. Cross-talk between Akkermansia muciniphila and gut epithelium controls diet-induced obesity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:9066–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Plovier H, Everard A, Druart C, Depommier C, Van Hul M, Geurts L, et al. A purified membrane protein from Akkermansia muciniphila or the pasteurized bacterium improves metabolism in obese and diabetic mice. Nat Med. 2017;23:107–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Larsen N, Vogensen FK, van den Berg FW, Nielsen DS, Andreasen AS, Pedersen BK, et al. Gut microbiota in human adults with T2D differs from non-diabetic adults. PLoS ONE. 2010;5: e9085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iatcu CO, Steen A, Covasa M. Gut microbiota and complications of type-2 diabetes. Nutrients. 2021;14:166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang X, Shen D, Fang Z, Jie Z, Qiu X, Zhang C, et al. Human gut microbiota changes reveal the progression of glucose intolerance. PLoS ONE. 2013;8: e71108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Karlsson FH, Tremaroli V, Nookaew I, Bergstrom G, Behre CJ, Fagerberg B, et al. Gut metagenome in European women with normal, impaired and diabetic glucose control. Nature. 2013;498:99–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sato J, Kanazawa A, Ikeda F, Yoshihara T, Goto H, Abe H, et al. Gut dysbiosis and detection of “live gut bacteria” in blood of Japanese patients with T2D. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:2343–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Qiu J, Zhou H, Jing Y, Dong C. Association between blood microbiome and T2D mellitus: a nested case-control study. J Clin Lab Anal. 2019;33: e22842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ridaura VK, Faith JJ, Rey FE, et al. Gut microbiota from twins discordant for obesity modulate metabolism in mice. Science. 2013;341(6150):1241214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bays HE, Jones PH, Jacobson TA, et al. Lipids and bariatric procedures part 1 of 2: scientific statement from the national lipid association, American society for metabolic and bariatric surgery, and obesity medicine association: FULL REPORT. J Clin Lipidol. 2016;10(1):33–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sweeney TE, Morton JM. The human gut microbiome: a review of the effect of obesity and surgically induced weight loss. JAMA Surg. 2013;148(6):563–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Forslund K, Hildebrand F, Nielsen T, Falony G, Le Chatelier E, Sunagawa S, et al. Disentangling T2D and metformin treatment signatures in the human gut microbiota. Nature. 2015;528:262–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu H, Esteve E, Tremaroli V, Khan MT, Caesar R, Manneras-Holm L, et al. Metformin alters the gut microbiome of individuals with treatment-naive T2D, contributing to the therapeutic effects of the drug. Nat Med. 2017;23:850–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bryrup T, Thomsen CW, Kern T, Allin KH, Brandslund I, Jorgensen NR, et al. Metformin-induced changes of the gut microbiota in healthy young men: results of a non-blinded, one-armed intervention study. Diabetologia. 2019;62:1024–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Greer RL, Dong X, Moraes AC, Zielke RA, Fernandes GR, Peremyslova E, et al. Akkermansia muciniphila mediates negative effects of IFNgamma on glucose metabolism. Nat Commun. 2016;7:13329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huang L, Xiong S, Liu H, et al. Bioinformatics analysis of the inflammation-associated lncRNA-mRNA coexpression network in type 2 diabetes. J Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone Syst. 2023;2023:6072438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu X, Su Y, Liu J, Liu D, Yu C. Inhibition of Th17 cell differentiation by aerobic exercise improves vasodilatation in diabetic mice. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2024;46(1):2373467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Targher G, Corey KE, Byrne CD, Roden M. The complex link between NAFLD and T2D mellitus—mechanisms and treatments. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;18:599–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mooradian AD, Morley JE, Levine AS, Prigge WF, Gebhard RL. Abnormal gut permeability to sugars in diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 1986;29:221–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Han H, Jiang Y, Wang M, Melaku M, Liu L, Zhao Y, et al. Gut dysbiosis in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): focusing on the gut-liver axis. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2023;63:1689–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang R, Tang R, Li B, Ma X, Schnabl B, Tilg H. Gut microbiome, liver immunology, and liver diseases. Cell Mol Immunol. 2021;18:4–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]