Abstract

Background

Fibrogenesis is a common pathological feature of endometriotic lesions and contributes to the development of endometriosis-associated chronic pelvic pain and infertility. TGF-β is a critical factor in the induction of fibrogenesis; however, the underlying regulatory mechanisms of TGF-β-induced fibrosis in endometriosis remain unclear. In this study, we investigated the effects and mechanisms of CCN5 in regulating the progression of TGF-β-induced fibrosis in endometriosis.

Methods

We investigated the role of CCN5 in TGF-β-induced proliferation and pro-fibrotic responses in primary HESCs through CCN5 overexpression and knockdown techniques. We evaluated the impact of CCN5 modulation on the activation of the TGF-β/Smad and Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathways in primary HESCs subjected to TGF-β stimulation. To elucidate the role of Smad3 in CCN5 mediating TGF-β-induced pro-fibrotic response and the activation of TGF-β/Smad and Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathways, we employed SIS3, a specific inhibitor of Smad3. Additionally, we assessed the interaction between CCN5 and Smad3 in primary HESCs.

Results

The expression of CCN5 was significantly elevated at both the mRNA and protein levels in patients with endometriosis compared to healthy controls. Overexpression of CCN5 through transfection with LV-CCN5 notably attenuated TGF-β-induced proliferation and pro-fibrotic responses, whereas CCN5 knockdown exhibited the opposite effects in primary HESCs. Additionally, we observed the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, a classical TGF-β-associated pro-fibrotic pathway, was significantly activated in primary HESCs under TGF-β stimulation. CCN5 overexpression inhibited the increased activity of both TGF-β/Smad and Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathways induced by TGF-β, while knockdown of CCN5 significantly enhanced TGF-β-induced activation of these pathways, an effect that was partially mitigated by the TGF-β inhibitor pirfenidone. An in vitro study demonstrated that SIS3, a specific Smad3 inhibitor, blocked the effects of CCN5 knockdown on TGF-β-induced proliferation and pro-fibrotic responses in endometriosis. Furthermore, we established that CCN5 directly interacts with Smad3 in cytoplasm, inhibiting Smad3’s translocation into the nucleus and the subsequent activation of downstream target genes associated with TGF-β signaling pathways.

Conclusions

CCN5 serves as an crucial negative regulator of fibrosis progression in endometriosis and represents a potential therapeutic target for endometrial fibrosis.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12967-025-06804-9.

Keywords: Endometriosis, CCN5, TGF-β, Fibrosis, Wnt/β-catenin, Smad

Introduction

Endometriosis is a chronic inflammatory disease characterized by endometrial-like tissue outside the uterus, which is estimated to affect 6–10% of women of reproductive age [1]. It is associated with chronic pelvic pain and infertility in many patients, and should be considered a public health problem because of its negative effects on the quality of life of patients and the heavy economic burden of treatment, work loss, and healthcare costs [2]. The pathogenesis of endometriosis is complicated, and the heterogeneous symptoms of endometriosis are mediated by a variety of mechanisms that affect the efficacy of current treatment strategies such as gynecological surgery, oral contraceptives, progestins, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists. Therefore, it is desirable to explore the precise pathogenic mechanisms underlying endometriosis to develop potential therapeutic approaches.

An increasing number of studies have revealed that fibrosis, one of the main pathogenic features found in all endometriosis subtypes, contributes substantially to the clinical symptoms of endometriosis [3]. Therefore, targeting the progression of fibrosis is regarded by some researchers as an essential therapeutic strategy for relieving the symptoms of patients with endometriosis [4]. TGF-β is the main driving influence of fibrogenesis in many fibrotic diseases such as cardiac failure and kidney fibrosis [5]. Previous studies have demonstrated that TGF-β levels were significantly increased in ectopic endometrial lesions and plays a key role in the initiation and development of fibrogenesis of endometriotic lesions [6, 7]. Although TGF-β plays an important pathogenic role in the progression of endometriosis, attempts to target TGF-β and its receptors as therapeutic agents have failed because of the essential role of the TGF-β signaling pathway in various physiological processes within the body. Furthermore, the precise mechanisms by which TGFβ mediates endometriosis-associated fibrosis remain incompletely understood [8]. Therefore, it is crucial to investigate the specific regulators and mechanisms involved in the TGF-β-mediated fibrogenesis process in ectopic endometriotic lesions to identify potential therapeutic targets for endometriosis.

Cellular communication network factor 5 (CCN5, also known as WISP2), a member of the CCN family, contributes to many important physiological processes such as cell proliferation, angiogenesis, and extracellular matrix regulation [9]. A growing number of evidence suggests that CCN5 plays an important role in the regulation of the fibrotic process [10, 11]. A previous study demonstrated that CCN5 and CCN2, key regulatory factors promoting fibrosis, exert opposing effects on fibroblast transdifferentiation induced by TGF-β [12]. In addition, a recent study identified CCN5 as a significant negative regulator of cardiac fibrosis by inhibiting myofibroblast activation and attenuating the TGF-β signaling pathway, indicating that CCN5 may serve as a potential therapeutic target for cardiac fibrosis [13]. Interestingly, Sun-Jing Bae et al. [14] found that CCN5 expression is significantly elevated in ectopic lesions of patients with endometriosis, suggesting a pathogenic role for CCN5 in this condition. However, it remains unclear whether CCN5 is also involved in the regulation of TGF-β induced fibrogenesis in endometriosis.

In the present study, we investigated the role of CCN5 in the fibrotic process induced by TGF-β in endometriosis. Our results indicated that expression of CCN5 was significantly increased in ectopic endometrial lesions. Reduced CCN5 levels promoted the pro-fibrotic transition of human endometrial stromal cells partially through activation of the TGF-β/Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway by promoting Smad3 shuttling from the cytosol into the nucleus. Conversely, overexpression of CCN5 exhibited an opposing effect both in vitro and in vivo. Our study demonstrates that CCN5 plays a critical role in the regulation of fibrogenesis and presents a potential therapeutic target for the treatment of endometriosis.

Materials and methods

Ethical approval

All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publications No. 8023, revised 2011), and were approved by the Ethical Committee of Medical Research of ZHBY Biotech Co., Ltd (Nanchang, China) (Reference number: K-2022–0487-1). The use of clinical samples in this study was approved and monitored by the Ethical Committee of Medical Research of the First Affiliated Hospital of Hainan Medical University (Haikou, China) (Reference number: 2022-L-38). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to the collection of tissue samples.

Clinical samples

This study included 15 patients (age range 24–35 years) who underwent laparoscopy with a diagnosis of ovarian endometriosis confirmed by histopathology, alongside 15 control patients (age range 25–35 years) who underwent surgery for benign gynecological conditions, such as benign ovarian cysts and uterine leiomyomas, without endometriosis. All participants had regular menstrual cycles and did not undergo hormonal treatment for at least three months prior to surgery. Among these samples, all 15 patient samples were collected from individuals in the late stages of disease progression (stages III-IV) during the secretory phase of their menstrual cycle. The cyst wall of the ovarian endometrioma was excised, and ectopic endometriotic lesions were carefully removed from the inner lining. Eutopic endometrial biopsies were obtained using endometrial suction catheters.

Cell culture

Primary human endometrial stromal cells (HESCs) were isolated as previously described [7, 15]. Briefly, primary HESCs were digested with 0.2% type I collagenase and filtered through a sieve. After centrifugation of the cell suspension at 500 g for 5 min, the cell pellet was resuspended in complete medium and placed in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C. After 6–8 h, the medium was replaced (nonadherent cells were removed) and purified endometrial stromal cells were obtained. The medium was replaced every 2–3 days. Passage 1 cells were used in the experiments. Immunofluorescence staining (vimentin) was performed to determine the purity of isolated endometrial and endometriotic stromal cells, as previously described [7]. In the present study, the purity of the stromal cells was at least 98%, as confirmed by positive cellular staining for vimentin (Figure S1A).

Treatment with transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) and pirfenidone

TGF-β is a well-known pro-fibrotic activator for the fibrogenesis in ectopic lesions of endometriosis [6]. To verify the effects of CCN5 on pro-fibrotic transition in endometriosis, Primary HESCs transfected with the CCN5 overexpression plasmid were treated with 10 ng/mL TGF-β (#781,802, BioLegend) for 24 h. Primary HESCs transfected with shCCN5 were treated with 10 ng/mL TGF-β with or without 100 g/mL pirfenidone (HY-B0673, Med Chem Express), an inhibitor of the TGF-β signaling pathway, for 24 h.

Treatment with SIS3

Smad3 is a key transcription factor in-associated signaling pathway, as previously reported [16]. To determine the role of Smad3 in the CCN5-mediated activation of pro-fibrotic effects in primary HESCs, 10 μM SIS3 (HY-100444, Med Chem Express) which is the specific Smad3 inhibitor was stimulated with CCN5-knockdown primary HESCs for 24 h.

Vector construction and transfection

The overexpression of CCN5 (LV-CCN5) and silencing of CCN5 (sh-CCN5), and scrambled shRNA as a negative control (sh-NC) were purchased from Tsingke Biotechnology Co., Ltd. Certain constructs, together with lentivirus-packing plasmids, were transfected into HEK293T cells using Lipofectamine™ 3000 (L3000015, Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The culture medium of the transfected cells was then used to infect the target cells. The shRNAs were prepared using at least two different target sequences for the target gene, and essentially the same results were observed for the first and second shRNAs.

Nucleo-plasmic separation assay

Experimental cells were harvested in an ice-cold Nuclei EZ lysis buffer (NUC101, Sigma-Aldrich). Then the lysates were subjected to subcellular fractionation by centrifuging at 500g for 5 min at 4 ℃. The supernatants were collected as non-nuclear cytoplasmic fractions, while the sediments were washed twice with the Nuclei EZ lysis buffer, and the resulting nuclear fractions were pelleted by centrifuging at 500g for 5 min at 4 ℃. Subsequently, the cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions were evaluated by western blotting using specific antibodies.

Endometriosis mice model

A group of adult female C57BL/6 mice aged 6–8 weeks was purchased from Cyagen Biosciences (Guangzhou, China) and maintained in the animal facility for 2 weeks prior to experimentation. To establish the intraperitoneal endometriosis model, one-third of the mice were randomly selected as donors (n = 15), while the remaining mice served as recipients (n = 30). Beginning on day 0, the donor mice were intramuscularly injected with estradiol benzoate (0.1 mg/kg/d) for 7 days prior to surgery. On day 7, the donor mice were sacrificed, and their uterine horns were removed under sterile conditions. The harvested endometrium was minced into fragments measuring less than 1 mm in diameter. A small incision (approximately 1 cm) was made on the lateral side of the abdomen of the recipient mice. The prepared endometrial tissue fragments were suspended in sterile saline and carefully injected intraperitoneally into the peritoneal cavity of the recipient mice, maintaining a ratio of 1:2 between the uterine tissue and the intraperitoneal injection. To confirm the induction of endometriosis, the recipient mice were sacrificed after 21 days (day 28), and their peritoneal cavities were examined for signs of endometriosis. Suspicious tissues were collected for histopathological assessment. Furthermore, C57BL/6JCya-Ccn5em1/Cya mice (#S-KO-16036), which have a knockout of the CCN5 gene, were also acquired from Cyagen Biosciences (Guangzhou, China). In experiments aimed at verifying the regulatory role of CCN5 in vivo, uterine tissue from either wild-type or CCN5-knockout mice was transferred into wild-type mice following the forementioned construction method. All animal experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee and conducted in strict accordance with the approved guidelines.

Immunohistochemistry

The endometrial tissues were collected, fixed in 10% formalin acid (5%) and embedded in paraffin for histopathological examination. Paraffin-embedded cervical tissues were cut into 4 μm thick sections and stained as previously described. In brief, immunohistochemical staining was performed with mouse monoclonal antibody directed against human αSMA, (#19,245, Cell Signaling Technology). After rinsing with phosphate buffered saline (PBS), the sections were incubated with a secondary antibody for 1 h and stained with 3, 3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB; Zhongshan biotech, Beijing, China). All sections were dehydrated and sealed with hematoxylin for counterstaining. Images were captured using a microscope (Olympus).

Hematoxylin–Eosin (H&E), Masson and Sirius red staining

The endometrial tissues were collected, fixed in 10% formalin acid (5%) and embedded in paraffin for histopathological examination. Paraffin-embedded cervical tissues were cut into 4 μm thick sections and then stained as previously reported [17]. The tissue sections were dewaxed in xylene and washed twice with 100% ethanol to eliminate the xylene, followed by rehydration in a series of gradient concentrations of ethanol with distilled water. Subsequently, the sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), Masson’s trichrome stain, or Sirius red stain according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and visualized by microscopy (Olympus).

Immunofluorescent staining

Paraffin-embedded tissues were cut into 4 μm thick sections and then performed as previously described. Primary HESCs were cultured on coverslips and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. After permeabilization with PBS-T (0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS solution), 5% bovine serum albumin was used to block non-specific interaction for 30 min and then incubated HESCs with primary antibodies against CCN5 (sc-514070, Santa Cruz), β-catenin (#8480, Cell Signaling Technology), Smad3 (#9523, Cell Signaling Technology), α-SMA (#19,245, Cell Signaling Technology), Vimentin (60,330–1-Ig, Proteintech) or CK-18 (66,187–1-Ig, Proteintech) at 4 ℃ overnight. A fluorescence-conjugated secondary antibody solution (1:100; MultiSciences, Hangzhou, China) was incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (Sigma-Aldrich).

Cell proliferation assay

A Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8; Yeasen, Shanghai, China) assay and EdU assay were used for cell proliferation assays according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Primary HESCs transfected with the CCN5 overexpression plasmid or shCCN5 were seeded into 96-well tissue culture plates at 3500 cells per well. After treatment with TGF-β or the vehicle for 36 h, 10 μL of CCK-8 reagent was added to each well at indicated time points according to manufacturer’s instruction. After incubation for 2 h at 37 ℃, the degree of cell proliferation was measured by the increase in absorbance at 450 nm.

Primary HESCs were seeded in 24-well plates (2 × 104/mL), and treatment details are described in the CCK-8 assay. After treatment, the EdU assay was performed using the EdU cell proliferation kit with Apollo 568 (Ribobio, China), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Primary HESCs were fixed, washed and permeabilized after incubation with EdU working reagents for 2 h at 37 ℃. Then, primary HESCs were incubated with the nuclear dye Hoechst 33,342 reaction reagent for 30 min in the dark. The proliferative capacity of primary HESCs was calculated as EdU incorporation rate (%) = Edu-positive cells (red)/st-positive cells (blue). All experiments were conducted in triplicates.

Cell apoptosis assay

Flow cytometry analysis was performed to quantify the apoptosis rate of HESCs using an Annexin V/propidium iodide (PI) staining assay kit (Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China), in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. For the assessment of the apoptosis rate, 4 × 105 HESCs were seeded in 6-well plates. After 48 h of transfection, the cells were stained and subsequently analyzed using flow cytometry (BD Biosciences, USA).

Luciferase reporter assay of the TGF‐β‐response element (TRE)‐ and Tcf/Lef‐dependent promoters

The experiments were performed as reported previously [18]. Primary HESCs (1 × 105), transfected with CCN5 overexpression plasmid or shCCN5, seeded in serum‐free DMEM medium treated with TGF-β, TGF-β + pirfenidone or the vehicle were co-transfected with the exogenous TRE DNA subcloned into a promoterless luciferase expression vector, pGL3 (1 μg; Promega), along with the Renilla luciferase vector, pRL‐CMV (0.1 μg), by using Lipofectamine™ 3000 (L3000015, Invitrogen). Luciferase activity was measured using a dual-luciferase reporter assay system (E1910, Promega).

For the Tcf/Lef‐dependent promoter assay, pTop‐Flash or pFop‐Flash luciferase reporter vector (1 μg), together with pRL‐CMV (0.1 μg), were co-transfected into the primary HESCs. At 5 h post-transfection, the cells were rinsed with fresh medium and cultured in a medium supplemented with 10% FBS for 24 h. Following treatment with recombinant human TGF-β at 0, 5, 10, 20 ng/mL for 24 h, the cells were lysed, and then luciferase activity was measured using the Dual Luciferase Kit (Promega). The results normalized to Renilla luciferase activity were referred to as promoter activity. In the case of the Tcf/Lef promoter, the promoter activity was expressed as a ratio of pTop‐Flash/pFop‐Flash.

Immunoblot assay and Co-IP

Immunoblot assay

Standard western blotting was performed as the general protocol set out on the Cell Signaling Technology website (https://www.cellsignal.cn/learn-and-support/protocols). The antibody for CCN5 (sc-514070) was purchased from Santa Cruz, and p-β-catenin (80,067–1-RR), β-actin (81,115–1-RR), LaminB1 (12,987–1-AP), c-Myc (67,447–1-Ig) and Cyclin D1 (60,186–1-Ig) were purchased from Proteintech, whilst α-SMA (#19,245), Collagen I (#72,026), Smad3 (#9523), p-Smad3 (#9520), β-catenin (#8480) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. The secondary antibodies were purchased from ZSGB-Bio.

Co-IP

Cells lysates were harvested by lysed cells in IP lysis buffer with protease inhibitor cocktail at 4 ℃ for 30 min. Then cells lysates were centrifugation at 12,000 ×g for 10 min at 4 ℃ and the supernatant was collected for IP overnight at 4 ℃ with indicated antibodies and protein G-agarose beads. After overnight incubation, washed proteins bound on the beads 4 times with IP lysis buffer, boiled in 1 × Laemmli buffer, and fractionated by SDS-PAGE, followed by immunoblot assays, as described previously, with antibodies against CCN5 and Smad3.

RT-qPCR

RT-qPCR was performed as previously described. Briefly, total RNA was isolated from cells using TRIzol reagent (T9424, Sigma-Aldrich), and cDNA was synthesized using an RT-qPCR kit from TAKARA (RR036A). The relative mRNA transcript levels were calculated using the 2−ddCt method. The primers used for RT-qPCR were listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

The primers used for RT-qPCR

| Gene | Forward (5′ to 3′) | Reverse (5′ to 3′) |

|---|---|---|

| CCN5 | TGTGCCCGACACCATGTACC | CCACAGCCATCCAGCACCAG |

| TGF-β | CTAATGGTGGAAACCCACAACG | TATCGCCAGGAATTGTTGCTG |

| COL1A1 | ATGCCATCAAAGTCTTCTGCAAC | GAATCCATCGGTCATGCTCTCG |

| α-SMA | AAAAGACAGCTACGTGGGTGA | GCCATGTTCTATCGGGTACTTC |

| C-Myc | GTCAAGAGGCGAACACACAAC | TTGGACGGACAGGATGTATGC |

| Jun | TCCAAGTGCCGAAAAAGGAAG | CGAGTTCTGAGCTTTCAAGGT |

| Cyclin D1 | GCTGCGAAGTGGAAACCATC | CCTCCTTCTGCACACATTTGAA |

| SNAIL1 | ACTGCAACAAGGAATACCTCAG | GCACTGGTACTTCTTGACATCTG |

| ZEB1 | TTACACCTTTGCATACAGAACCC | TTTACGATTACACCCAGACTGC |

| ZEB2 | GCGATGGTCATGCAGTCAG | CAGGTGGCAGGTCATTTTCTT |

| TWIST | GTCCGCAGTCTTACGAGGAG | GCTTGAGGGTCTGAATCTTGCT |

Statistical analysis

All experiments were conducted independently at least three times. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 20.0. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or standard error of the mean (SEM), with a P value < 0.05 considered significant. Independent sample t-tests were employed to analyze differences between two groups, while one-way ANOVA was utilized to assess differences among multiple groups.

Results

Increased expression of CCN5 in ectopic tissues of patients with endometriosis

Emerging evidence has demonstrated that CCN5 contributes to fibrosis progression in a variety of fibrotic diseases, and a previous study reported that CCN5 expression is significantly increased in patients with endometriosis [14]. Thus, we hypothesized that CCN5 may be involved in endometriosis-associated fibrosis. To verify this hypothesis, we investigated the expression of CCN5 in ectopic endometrial lesions and in the endometrium of healthy controls. Our results demonstrated that CCN5 expression was significantly increased in endometriosis samples at both the mRNA (Fig. 1A) and protein levels (Fig. 1B) compared to endometrial tissues from healthy controls, consistent with previous study [14]. Immunohistochemical staining revealed that CCN5 expression was significantly higher in endometriotic lesions than in healthy control samples (Fig. 1C). Similar findings were observed in immunofluorescence staining images, where CCN5 appears to co-localize with α-smooth muscle actin (ACTA2)-positive myofibroblast cells in ectopic lesions of endometriosis (Fig. 1D). Collectively, these findings suggest that the expression of CCN5 is significantly increased in ectopic lesions of patients with endometriosis, indicating a potential role for CCN5 in the pathogenesis of fibrosis in endometriosis.

Fig. 1.

Expression of CCN5 is significantly increased in endometriosis. A The mRNA expression of CCN5 in ectopic lesions of patients with endometriosis and control eutopic endometrial tissues measured by RT-qPCR (n = 15, ****p < 0.0001). B Protein expression of CCN5 in ectopic lesions of patients with endometriosis and control eutopic endometrial tissues determined by western blotting. C IHC assay of CCN5 protein expression in control eutopic endometrial tissues and ectopic lesions of patients with endometriosis. Scale bar: 100 μm; 50 μm. D Immunofluorescent staining assay of CCN5 protein expression in control eutopic endometrial tissues and ectopic lesions of patients with endometriosis. Scale bar: 50 μm; 20 μm. Data are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical analysis was performed using an unpaired student’s t-test, ****p < 0.0001

Decreased CCN5 promoted TGF-β-induced primary HESCs proliferation and pro-fibrotic marker expression in vitro

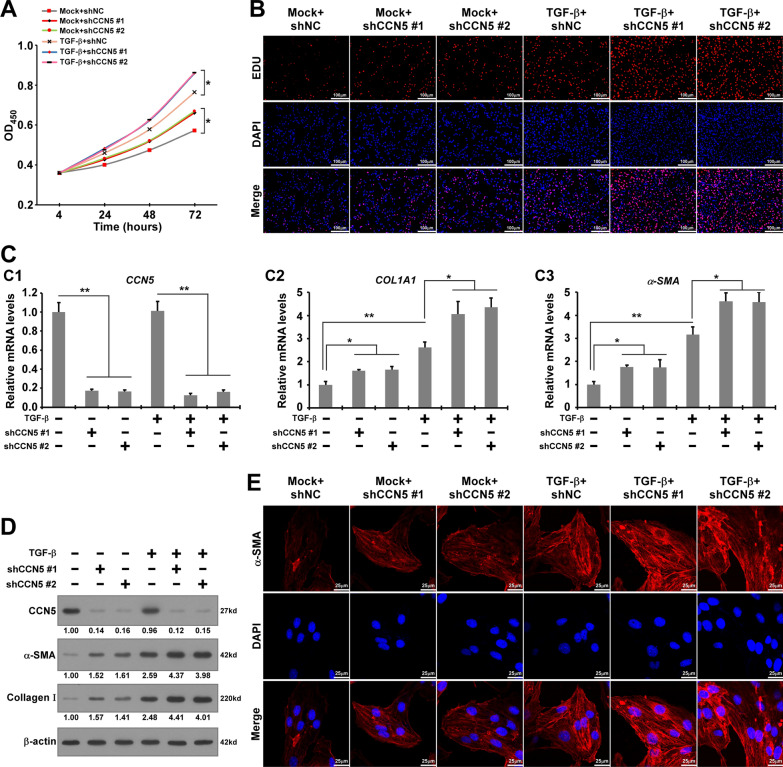

To determine the role of CCN5 in the progression of fibrogenesis in endometriosis, we performed in vitro CCK-8 and EdU assays. We constructed two independent CCN5 knockdown (CCN5-KD) primary HESCs using specific shRNAs. The cells were treated with or without TGF-β, a well-known driver of fibrogenesis in endometriosis that induces HESCs proliferation and pro-fibrotic marker expression. The results from the CCK-8 and EdU assays revealed that TGF-β increased the proliferation of HESCs, which was further enhanced by CCN5-KD compared to the control (Fig. 2A, B). Our results suggest that CCN5 knockdown promotes TGF-β-induced proliferation of HESCs.

Fig. 2.

Decreased CCN5 promotes TGF-β-induced proliferation and pro-fibrotic markers expression of primary HESCs in vitro. A The proliferation ability of shCCN5-HESCs and shNC-HESCs treated with TGF-β or not by CCK-8 assay. Data are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical analysis was conducted using one-way ANOVA for the optical density (OD) values at 72 h. *p < 0.05. B EdU assay was performed to reveal the effects of CCN5 knockdown on the proliferation of CCN5-knockdown HESCs and WT-HESCs treated with TGF-β or without TGF-β. Scale bar, 100 μm. C The mRNA expression levels of CCN5, COL1A1 and α-SMA in shCCN5-HESCs and shNC-HESCs treated with TGF-β or without TGF-β. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. D Expression of CCN5, α-SMA, Collagen Ι in shCCN5-HESCs and shNC-HESCs treated with TGF-β or without TGF-β. E Immunofluorescence for α-SMA in shCCN5-HESCs and shNC-HESCs treated with TGF-β or without TGF-β. Scale bar, 25 μm (red α-SMA, blue DAPI)

To verify the role of CCN5 in the TGF-β-induced pro-fibrotic process within primary HESCs, we performed RT-qPCR and western blotting to assess the expression of classical hallmarks associated with the pro-fibrotic process. Our RT-qPCR results demonstrated that TGF-β significantly increased the mRNA expression of COL1A1 (collagen type I alpha 1 chain) and α-SMA. Western blotting results indicated that TGF-β enhanced the protein expression of α-SMA and Collagen-Ι (designated as COL1A1 protein in this study) compared to the control group without TGF-β stimulation (Fig. 2C, D). In HESCs treated with TGF-β, CCN5-KD significantly promoted the transition of pro-fibrotic markers compared to HESCs transfected with shNC. We performed immunofluorescence to further assess the effects of CCN5 on the expression of α-SMA, a contractile protein indicative of the transformation of fibroblasts into myofibroblasts. As illustrated in Fig. 2E, the α-SMA signal (red) predominantly localized in the cytoplasm of HESCs and was considerably enhanced in CCN5-KD HESCs stimulated with TGF-β. Collectively, these results indicate that CCN5 knockdown promotes the transition of pro-fibrotic markers in HESCs.

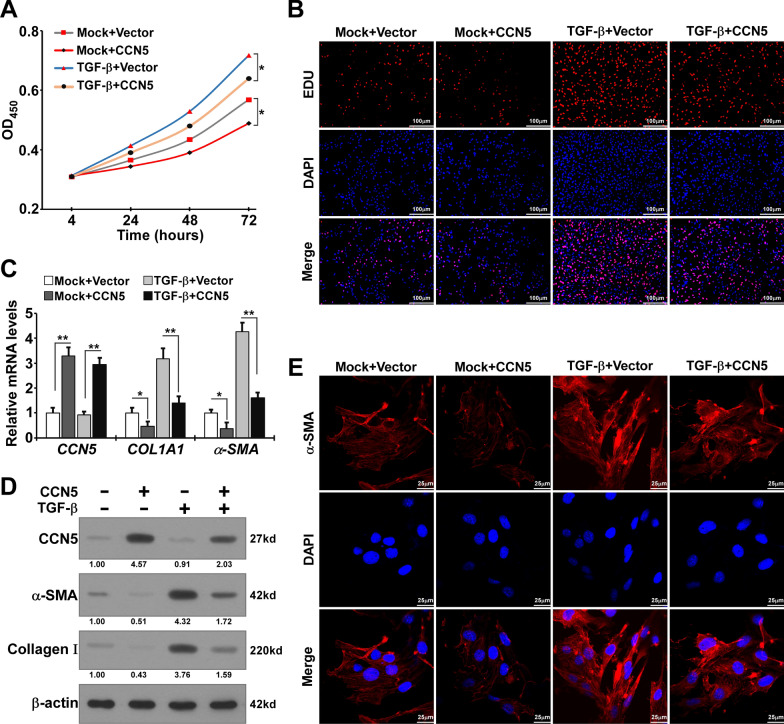

CCN5 overexpression attenuated TGF-β-induced primary HESCs proliferation and pro-fibrotic marker transition in vitro

To further verify the effects of CCN5 on TGF-β stimulated primary HESCs, we constructed CCN5 overexpression HESCs through transfection with the LV-CCN5 plasmid. Results from the CCK-8 and EdU assays indicated that CCN5 significantly inhibited TGF-β-induced proliferation of HESCs (Fig. 3A, B). Additionly, apoptosis experiments revealed that CCN5 slightly promoted apoptosis in HESCs (Figure S1B-C). RT-qPCR and western blotting were performed to elucidate the impacts of CCN5 overexpression on the expression levels of TGF-β-induced pro-fibrotic markers. The results demonstrated the upregulation of COL1A1 and α-SMA induced by TGF-β was attenuated by CCN5 overexpression (Fig. 3C). Western blotting results showed that overexpression of CCN5 significantly inhabited the upregulation of α-SMA and Collagen-Ι in HESCs stimulated by TGF-β (Fig. 3D). Immunofluorescence analysis indicated a reduction in the α-SMA signal (red) in CCN5 overexpressing HESCs treated with TGF-β (Fig. 3E). Collectively, our findings suggest that CCN5 overexpression exerts an inhibitory effect on TGF-β-induced pro-fibrotic responses in HESCs.

Fig. 3.

Overexpression of CCN5 attenuates TGF-β-induced proliferation and pro-fibrotic markers expression of primary HESCs in vitro. A The proliferation ability of CCN5-overexpression HESCs (CCN5) and control-HESCs (Vector) treated with TGF-β or without TGF-β by CCK-8 assay. Data are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical analysis was conducted using one-way ANOVA for the optical density values at 72 h. *p < 0.05. B EdU assay was performed to reveal the effects of CCN5 knockdown on the proliferation of CCN5-overexpression HESCs and control-HESCs treated with TGF-β or without TGF-β. Scale bar, 100 μm. C The mRNA expression levels of CCN5, COL1A1 and α-SMA in CCN5-overexpression HESCs and control-HESCs treated with TGF-β or without TGF-β. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA for each target gene. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. D Expression of CCN5, α-SMA, Collagen Ι in CCN5-overexpression HESCs and control-HESCs treated with TGF-β or without TGF-β. E. Immunofluorescence for α-SMA in CCN5-overexpression HESCs and control-HESCs treated with TGF-β or without TGF-β. Scale bar, 25 μm (red α-SMA, blue DAPI)

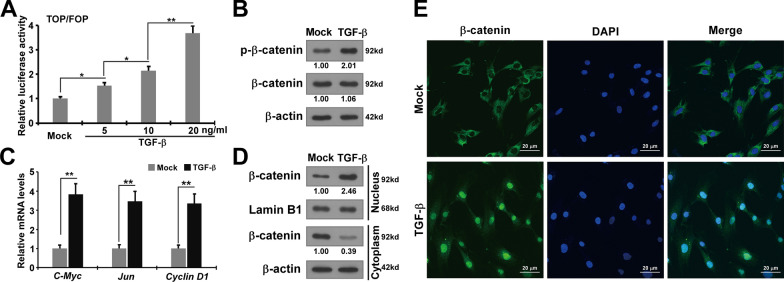

TGF-β activates Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in primary HESCs

The catenin signaling pathway plays an essential role in the progression of fibrogenetic diseases such as renal and cardiac fibrosis. Recent studies have demonstrated that β-catenin signaling contributes to the fibrosis of ectopic lesions in endometriosis [17]. To explore the precise molecular mechanisms of CCN5 regulating TGF-β-induced pro-fibrotic effects on primary HESCs, we highlighted Wnt/β-catenin intracellular signaling pathways. A luciferase reporter assay was performed to investigate the effects of TGF-β-induced nuclear β-catenin signaling in HESCs by measuring the transcriptional activity of the β-catenin-responsive promoter. The transcriptional activity of the β-catenin-responsive Tcf/Lef-binding promoter in HESCs significantly increased at higher concentrations of TGF-β-stimulation (Fig. 4A). To further confirm the activating effect of TGF-β on β-catenin signaling in HESCs, we assessed the expression level of phosphorylated β-catenin and found that TGF-β significantly elevated this level in HESCs (Fig. 4B). RT-qPCR was performed to evaluate the impacts of TGF-β stimulation on the expression of downstream target genes of β-catenin signaling pathway. We observed that TGF-β significantly upregulated the expression of these downstream target genes (Fig. 4C). These results demonstrate that TGF-β significantly enhances the β-catenin signaling pathway in HESCs.

Fig. 4.

TGF-β activates Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway activation in primary HESCs. A Wnt/β-catenin signaling was activated by TGF-β. Luciferase reporter assays was performed in HESCs transfected pTop‐Flash or pFop‐Flash luciferase reporter with the vehicle or TGF-β. FLuc/RLuc activity was determined as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. B The protein expression of phosphorylation-β-catenin, β-catenin in HESCs treated with TGF-β or without TGF-β were measured by western blotting. C The mRNA expression of c-Myc, Jun, Cyclin D1 in HESCs treated TGF-β or without TGF-β. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA for each target gene. **p < 0.01. D The protein expression of β-catenin in cytoplasmic and nuclear part of HESCs with or without TGF-β stimulation was measured by western blotting. E Immunofluorescence for β-catenin in HESCs treated with TGF-β or without TGF-β. Scale bar, 20 μm (green β-catenin, blue DAPI)

Previous studies have shown that β-catenin promotes the transcription of downstream target genes by translocating from the cytosol to the nucleus, a process in which TGF-β plays an crucial role [19, 20]. As illustrated in Fig. 4D and E, TGF-β increased nuclear β-catenin expression in HESCs compared to the controls. These results indicate that TGF-β activates the Wnt/β-catenin intracellular signaling pathway in HESCs, consistent with previous research, suggesting that TGF-β partially promotes the pro-fibrotic transition of HESCs through the Wnt/β-catenin pathway.

CCN5 regulates TGF-β/Smad and Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway

To determine whether CCN5 regulates the TGFβ-induced pro-fibrotic response mainly through the activation of TGF-β-associated intracellular signaling in primary HESCs, we initially conducted a TGF-β luciferase reporter assay. This assay utilized a transfected TGF-β luciferase reporter plasmid in CCN5 overexpression cells, as well as CCN5 Knockdown (KD1 or KD2) HESCs, both with and without TGF-β stimulation. The results showed that the transcriptional activity was significantly decreased in CCN5 overexpression cells (Fig. 5A). On the contrary, as Fig. 5B showed, TGF-β induced TGF-β transcriptional activity upregulation was significantly increased in CCN5-KD HESCs, whilst it was inhibited by TGF–β inhibitor pirfenidone. These findings suggest that CCN5 is involved in the regulation of TGF-β transcription activity in HESCs, whereby decreased levels of CCN5 promote TGF-β transcription.

Fig. 5.

CCN5 regulates activation of TGF-β/Smad and Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathways. A, B Luciferase reporter assays in primary HESCs transfected with the indicated plasmids and treated with the vehicle, TGF-β or prifenidone. FLuc/RLuc activity was determined as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. C, D. The mRNA expression of downstream target genes of TGF-β/Smad and Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathways in CCN5-overexpression HESCs (C) or CCN5-knockdown HESCs (D) treated with TGF-β or without TGF-β. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA for each target gene. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. E, F. The protein expression of p-Smad3, Smad3, p-β-catenin and β-catenin in CCN5-overexpression HESCs (E) or CCN5-knockdown HESCs (F) treated with TGF-β or without TGF-β. G. The protein expression of β-catenin in cytoplasmic and nuclear part of CCN5-overexpression HESCs or CCN5-knockdown HESCs was measured by western blotting

To investigate the role of CCN5 in regulating the expression of downstream target genes within TGF-β-associated signaling pathways, RT-qPCR assay was performed. The results demonstrated that CCN5 overexpression significantly decreased the transcription of SNAIL1, ZEB1, ZEB2, TWIST, C-Myc, Jun and Cyclin D1, which are downstream target genes of classical TGF-β-associated intracellular signaling pathways, including TGF-β/Smad and Wnt/β-catenin (Fig. 5C). In contrast, CCN5 knockdown (CCN5-KD1 or KD2) exhibited the opposite effects on TGF-β-induced expression of TGF-β/Smad and Wnt/β-catenin target genes, and these effects were abolished by pirfenidone (Fig. 5D). To further elucidate the role of CCN5 in the activation of TGF-β/Smad and Wnt/β-catenin signaling, we conducted a western blotting assay to assess the expression levels of phosphorylated Smad3 (p-Smad3) and phosphorylated β-catenin (p-β-catenin), which were significantly decreased in TGF-β-treated CCN5-overexpressing HESCs. Consistent with the RT-qPCR assay, CCN5 overexpression downregulated TGF-β induced phosphorylation of Smad3 and β-catenin, as well as downstream proteins C-Myc and Cyclin D1 (Fig. 5E). Conversely, CCN5 knockdown exacerbated the upregulation of Smad3 and β-catenin phosphorylation, along with increased levels of C-Myc and Cyclin D1 (Fig. 5F). Additionally, CCN5 also inhibited the nuclear distribution of β-catenin (Fig. 5G). Overall, these results indicate that CCN5 plays a crucial role in regulating the activation of TGF-β mediated TGF-β/Smad and Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathways, and that CCN5 overexpression inhibits these pathways in primary HESCs in response to TGF-β stimulation.

CCN5 regulates TGF-β induced proliferation and pro-fibrotic transition in primary HESCs through phosphorylation of Smad3

To further evaluate the underlying mechanism by which CCN5 mediates TGF-β-induced pro-fibrotic effects in HESCs, we examined Smad3, a key transcription factor in the TGF-β associated intracellular signaling pathway involved in TGF-β-induced fibrosis in endometriosis [6]. Subsequently, we investigated whether CCN5 regulates TGF-β induced proliferation and the pro-fibrotic transition in HESCs mainly through Smad3. SIS3, a specific Smad3 inhibitor that prevents Smad3 phosphorylation, was administered to CCN5-kncockdown HESCs. Our findings revealed that the addition of SIS3 abrogated CCN5 knockdown-induced HESCs proliferation as assessed by the CCK-8 assay, suggesting that Smad3 plays a crucial role in CCN5 regulation of HESCs proliferation (Fig. 6A). Furthermore, a RT-qPCR assay was conducted to confirm the role of Smad3 in the promotion of TGF-β-induced pro-fibrotic effects by CCN5 knockdown in HESCs. The results showed that SIS3 treatment inhibited the upregulation of COL1A1 and α-SMA induced by CCN5 knockdown, with western blotting corroborating these effects (Fig. 6B, C).

Fig. 6.

CCN5 regulates TGF-β induced proliferation and pro-fibrotic transition in HESCs through phosphorylation of Smad3. A Proliferative capability of primary HESCs in shCCN5-HESCs or shNC-HESCs treated with or without SIS3 assessed by CCK8 assay. Data are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical analysis was conducted using one-way ANOVA for the optical density values at 72 h. *p < 0.05. B The mRNA expression of downstream target genes of TGF-β/Smad and Wnt/β-catenin signaling in shCCN5-HESCs or shNC-HESCs treated with SIS3 or without SIS3. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA for each target gene. ns, non-significant, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. C The protein expression of α-SMA and Collagen Ι in shCCN5-HESCs or shNC-HESCs treated with SIS3 or without SIS3. D The HE, Masson and Sirius red staining of the endometriosis tissues from the endometriosis mice constructed based on CCN5 knockout mice and combined SIS3 treatment, along with the expression of α-SMA in the endometriosis tissues. Scale bar, 100 μm

Furthermore, we developed an endometriosis mouse model using CCN5 knockdown mice and treated them with SIS3 to investigate whether CCN5 inhibits fibrosis through the phosphorylation of Smad3. As shown in Fig. 6D, hematoxylin and eosin staining indicated a reduction in single-layer columnar epithelial cells, which were subsequently covered by flattened or low columnar epithelial cells following CCN5 knockdown. Masson and Sirius red staining demonstrated an increase in endometrial fiber deposition, with fibrosis hyperplasia becoming more pronounced after CCN5 knockdown. The typical pro-fibrotic marker α-SMA was significantly upregulated as a result of CCN5 knockdown. Notably, these effects were significantly mitigated in the SIS3 treatment group (Fig. 6D). These findings suggest that CCN5 regulates the TGFβ-induced pro-fibrotic transition in HESCs through the phosphorylation of Smad3. A recent study has reported that Smad3 regulates the activation of the β-catenin signaling pathway [19]. However, it remains unclear whether CCN5 knockdown promotes TGFβ-induced activation of β-catenin signaling pathway in HESCs through its interaction with Smad3.

CCN5 prohibited Smad3 shuttle into nucleus by forming a complex in cytosol

Smad3 activates signaling by translocating into the nucleus and binding directly to target gene promoters. To investigate whether CCN5 physically interacts with Samd3 in TGF-β-mediated signaling, we first conducted immunofluorescence staining and nucleoplasmic separation experiments to assess the effect of CCN5 overexpression on Smad3 distribution in HESCs, both with and without TGF-β stimulation. Our results demonstrated that CCN5 and Smad3 co-localized in the cytoplasm; however, TGF-β promoted the nuclear translocation of Smad3, thereby reducing its co-localization in the cytoplasm, whereas CCN5 overexpression promoted the distribution of Smad3 in the cytoplasm (Fig. 7A, B). Subsequently, through a Co-IP experiment, we found that endogenous CCN5 and Smad3 interact with each other in HESCs, with this interaction increasing following TGF-β interference (Fig. 7C). Additional Co-IP experiments, conducted after nuclear-cytoplasmic separation, indicated that the interaction between CCN5 and Smad3 primarily occurs in the cytoplasm, and that TGF-β inhibition enhances their interaction in this compartment (Fig. 7D). Molecular docking results suggest that CCN5 may interact with the HIS98, GLU102, and GLU131 residues of Smad3 via the ARG38 residue (Fig. 7E). These findings imply that CCN5 inhibits TGF-β induced Smad3 translocation into the nucleus by physically interacting with Smad3 in the cytosol.

Fig. 7.

CCN5 prohibited Smad3 shuttle into nucleus by forming complex in cytosol. A Immunofluorescence for CCN5 and Smad3 in HESCs treated with TGF-β or without TGF-β. Scale bar, 20 μm (green CCN5, red Smad3, blue DAPI). B The distribution of Smad3 in the nucleus and cytoplasm in CCN5-overexpression HESCs (CCN5) and control-HESCs treated with TGF-β or without TGF-β was detected by WB. C Co-immunoprecipitation assay of endogenous CCN5 and Smad3 in HESCs treated with or without TGF-β specific inhibitor TGF-β-IN-1. D Co-immunoprecipitation assay of CCN5 and Smad3 in cytoplasm or nucleus in HESCs treated with or without TGF-β specific inhibitor TGF-β-IN-1. E. Molecular docking of CCN5 with Smad3

Discussion

With the expanding knowledge of the pathology of endometriosis, fibrosis has been identified as one of the cardinal features of endometriosis and should be the focus of future research. Endometriosis is classified into three well-recognized phenotypes, and fibrosis is a consistent feature of the disease. A growing body of evidence suggests that fibrosis of endometriotic lesions contributes to the development of chronic pelvic pain, deep dyspareunia, and infertility in patients, highlighting that key role of fibrosis of ectopic lesions in the pathophysiology of endometriosis [21].

Studies have demonstrated that TGF-β is one of the main driving factors in fibrotic diseases such as cardiac fibrosis and is also significantly increased in endometriotic lesions which contribute to the fibrogenesis of endometriosis by inducing extracellular matrix synthesis and driving myofibroblast activation and differentiation which are characterized by neo-expressed α-SMA [6, 22, 23]. To date, attempts to directly target TGF-β to inhibit the pro-fibrotic process in endometriosis or other fibrosis diseases have failed, mainly because TGF-β is not only involved in fibrogenesis but also participates in many essential biological processes. Consequently, inhibiting TGF-β and its receptors can lead to severe adverse outcomes [24]. Therefore, it is crucial to elucidate the precise molecular mechanisms underlying TGF-β-induced fibrogenesis in endometriosis, as this could facilitate identification of alternative therapeutic strategies to prevent or delay fibrogenesis in affected patients. However, the exact mechanisms of TGF-β-induced fibrogenesis and the key regulators involved in this pathophysiological process have not been fully elucidated. In the current study, we demonstrate that CCN5 plays a protective role in the progression of TGF-β-induced fibrogenesis in endometriosis and may serve as a potential clinical therapeutic target.

CCN5 is a member of the CCNs protein family and exhibits various biological activities [9]. Recent studies have reported that the expression of CCN5 is significantly increased in endometriotic lesions [14], suggesting that CCN5 contributes to the development of endometriosis. Emerging evidence demonstrates that CCN5 plays a regulatory role in fibrogenesis in various tissues. Dongtak Jeong et al. [13] demonstrated that decreased CCN5 expression is involved in the development of cardiac fibrosis associated with heart failure by promoting TGF-β-induced myofibroblast activation, while overexpression of CCN5 attenuates the pro-fibrotic effects induced by TGF-β in cardiac tissues. However, whether CCN5 also playing a protective role in fibrogenesis in endometriosis induced by TGF-β has not yet been reported. Herein, we investigated CCN5 expression in ectopic endometriotic lesions. Our results revealed that CCN5 expression, both at the mRNA and protein levels, was significantly increased in endometriotic lesions compared to that in healthy control endometrial samples, which is in accordance with results of a previous report [14]. Similar results were obtained from immunohistochemical and immunofluorescence staining, which showed that the expression of CCN5 dramatically increased in ectopic lesions of endometriosis and mainly co-localized with α-SMA in endometriotic lesions, indicating that CCN5 may play a pathophysiological role in the progression of fibrosis in endometriosis.

Subsequently, we investigated the role of CCN5 in TGF-β-stimulated primary HESCs by either interfering with or overexpressing CCN5. The overexpression of CCN5, achieved through targeted Ad-CCN5, significantly reduced HESCs proliferation and the TGF-β induced expression of pro-fibrotic markers, particularly α-SMA and Collagen-Ι, both of which are critical components of fibrogenesis. Conversely, the knockdown of CCN5 elicited an opposing trend. Furthermore, in vivo studies demonstrated that CCN5 knockdown markedly promoted fibrosis in ectopic lesions compared to the control group. This observation indicates that the elevation of CCN5 in ectopic endometrial tissue represents a protective response by the body against the fibrotic process. This increase may be a compensatory response triggered by inflammation or other stress responses resulting from an initial anti-fibrotic reaction [3, 8, 25]. And its anti-fibrotic effects have been documented in various disease processes including cardiac fibrosis [13, 26]. Additionally, characteristics of ectopic endometrium, such as hormonal dysregulation and progesterone resistance [1], may contribute to the upregulation of CCN5 expression in ectopic endometrial lesions. In summary, these findings suggest that CCN5 plays a critical role in counteracting the fibrotic pathogenesis associated with TGF-β-induced endometriosis.

To identify the regulatory mechanisms of CCN5 on TGF-β-induced pro-fibrotic transition of HESCs, we focused on the classical TGF-β/Smad pathway and Wnt/β-catenin pathway which playing a vital role in the initiation and development of fibrosis diseases induced by TGF-β [27–29]. Guo et al. demonstrated that the TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway contributes to fibrogenesis of ectopic lesions in endometriosis [30]. Li et al. reported that the β-catenin pathway is activated by TGF-β1 involved in fibrogenesis in ovarian endometriomas [17]. However, the precise mechanisms regulating the TGF-β-associated classical signaling pathways in the fibrogenesis of endometriosis are not fully understood. In current study, we showed that TGF-β significantly induced phosphorylation of β-catenin and promoted its nuclear accumulation. Furthermore, TGF-β also markedly increased the expression of downstream targets of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling, such as C-Myc, Jun, Cyclin D1. This indicates that TGF-β activates the Wnt/β-catenin pathway in HESCs and that this pathway is involved in the TGF-β-induced fibrotic response in HESCs.

Next, we examined whether CCN5 mediates TGF-β-induced pro-fibrotic effects through regulating the classical TGF-β-associated intercellular signaling pathway. Our study revealed that CCN5 overexpression significantly attenuated the transcriptional activity of TGF-β, while knockdown of CCN5 showed the opposite effect. Gain and loss of function studies showed that CCN5 regulates the downstream target genes expression of the TGF-β signaling pathway and participates in the activation of the TGF-β/Smad and Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in HESCs. Pirfenidone, a specific TGF-β inhibitor, partially inhibited the increased pro-fibrotic response induced by CCN5 knockdown under TGF-β stimulation in HESCs. Taken together, our data suggest that CCN5 may regulate the expression of TGF-β-induced fibrotic markers in primary HESCs, at least partially, through the classical TGF-β-associated cellular signaling pathways, including TGF- β/Smad and Wnt/β-catenin. However, TGF-β-mediates the progression of tissue fibrosis through a complex signaling network, with many other intracellular signaling pathways involved in TGF-β-induced fibrogenesis. Therefore, further studies are warranted to determine whether CCN5 regulates TGF-β-induced pro-fibrotic effects in HESCs through other TGF-β-mediated intracellular signaling pathways.

Our results show that CCN5 has regulatory effects on the phosphorylation of Smad2/3 in human endometrial stromal cells. Several studies demonstrated that the Smad family of transcription factors plays a key role in TGF-β receptors-mediated intracellular signaling pathway [5, 19]. Smad2/3 are key transcription factors functioning mainly through shuttling into the nucleus and enhancing downstream genes transcription by forming a heteromeric complex with Smad4 [5, 31]. Previous studies revealed that Smad3 can form a complex with β-catenin, one of the key transcription factors of β-catenin pathway, to enhance gene transcription of pro-fibrotic molecules [32, 33]. These studies indicate that Smad3 plays a vital role in TGF-β-associated signaling pathways. To further elucidate whether CCN5 regulating TGF-β-associated signaling pathway in HESC through Smad3, SIS3, a specific Smad3 inhibitor [16], was administrated. Pharmacological inhibition of Smad3 with SIS3 in CCN5-knockdown HESCs abrogated the upregulatory effects of CCN5 silencing on TGF-β-induced pro-fibrotic transition and Wnt/β-catenin signaling activation in primary HESCs.

We generated a mouse model of endometriosis to investigate the role of CCN5 in endometriosis-associated fibrosis. Our findings indicate that CCN5 knockdown promotes pro-fibrotic progression in the ectopic lesions of endometriotic mice compared to WT control mice, as assessed by HE, Masson, and Sirius red staining. Furthermore, the pro-fibrotic effects of CCN5 knockdown in the mouse model of endometriosis were significantly attenuated by SIS3 treatment. These results suggest that CCN5 play a critical role in the TGF-β-induced pro-fibrotic response during the progression of endometriotic fibrosis, primarily mediated through Smad3, a key transcription factor in TGF-β-associated intracellular signaling pathways.

Numerous studies have demonstrated that TGF-β induced the translocation of Smad3 from the cytosol to the nucleus, activating pro-fibrotic downstream genes [34]. To elucidate the precise mechanism by which CCN5 regulates the TGF-β-associated intercellular signaling pathway in HESCs, a Co-IP assay was performed. The results showed that CCN5 directly interacts with Smad3 in the cytoplasm of HESCs. Moreover, our findings indicate that the formation of the CCN5-Smad3 complex in the cytosol inhibits TGF-β-induced translocation of Smad3 into the nucleus. Our observations support a model, in which the binding of CCN5 to Smad3 may mask the nuclear localization signal, thereby preventing the nuclear translocation process stimulated by TGF-β.

The precise mechanism by which CCN5 regulates fibrogenesis is complex. CCN2, another member of the CCN family, plays a crucial role in various fibrotic diseases, including endometriosis [35, 36]. Some studies have demonstrated that CCN5 functions as a dominant-negative protein that suppresses CCN2-mediated fibrosis through its interaction with CCN2 [12]. However, the potential protective role of CCN5 in the fibrogenesis of endometriosis via its interaction with CCN2 requires further investigation. Furthermore, CCN5 is a context-dependent regulatory molecule, and the spatial specificity of its domain interactions, along with the variations in the disease tissue microenvironment, may impart a “double-edged sword” regulatory effect. Therefore, future research should incorporate single-cell sequencing and spatial transcriptomics technologies to accurately elucidate the cellular interaction network of CCN5 within the endometriosis microenvironment. This will enable a detailed analysis of its dual role in different environments and tissues, thereby enhancing its potential as a therapeutic target. Additionally, future studies could focus on developing allosteric regulators, exploring epigenetic regulatory mechanisms, and investigating the spatiotemporal specificity of targeted drug delivery. These efforts should be combined with the optimization of preclinical models tailored to disease progression stages, biosafety assessments, and the establishment of a CCN5 activity scoring system to promote the development of precision personalized treatment strategies targeting CCN5.

Conclusions

Our findings underscore that the expression of CCN5 is decreased in ectopic endometriotic lesions, highlighting its key role in regulating the progression of fibrogenesis. The mechanisms through which CCN5 mediates TGF-β-induced fibrogenesis in ectopic lesions partially depend on the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, as it interacts with Smad3, thereby proventing Smad3 from translocating into the nucleus. Our data elucidate the precise mechanisms underlying fibrosis in endometriotic lesions and suggest that CCN5 may serve as a potential therapeutic target for managing fibrosis in endometriosis.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the participants and tissue donors involved in this study. We also thanks for the support of Nanfang Hospital, Southern Medical University.

Author contributions

Authors had full access to and reviewed the data analyses and vouch for fidelity of the trial to the protocol. Mian Liu, Yi Gong and Hong Cai were responsible for data analysis and vouches for the accuracy of the data., with the assistance of Rui Hua, Hong Li, Zhe Wang and Yao Zhou. The first manuscript draft was written by Mian Liu. Song Quan and Yanlin Ma were responsible for the design, guidance and revision of the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed and provided feedback on all versions.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82301914, 82202044, 81901566, 82171656), Natural Science Foundation of Hainan Province (Nos. 823MS145, 823QN349), and China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Nos. 2020M682810, 2021M691466).

Data availability

Data will be made available based on reasonable requests.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The use of clinical samples in this study was approved and monitored by the Ethical Committee of Medical Research of the First Affiliated Hospital of Hainan Medical University (Haikou, China) (Reference number: 2022-L-38). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to the collection of tissue samples.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All authors declare no competing of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Mian Liu, Yi Gong and Hong Cai have contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Yanlin Ma, Email: mayl1990@foxmail.com.

Song Quan, Email: QuanSongnffc@163.com, Email: quansong@smu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Taylor HS, Kotlyar AM, Flores VA. Endometriosis is a chronic systemic disease: clinical challenges and novel innovations. Lancet. 2021;397:839–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saunders PTK, Horne AW. Endometriosis: etiology, pathobiology, and therapeutic prospects. Cell. 2021;184:2807–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garcia Garcia JM, Vannuzzi V, Donati C, Bernacchioni C, Bruni P, Petraglia F. Endometriosis. Cellular and molecular mechanisms leading to fibrosis. Reprod Sci. 2023;30:1453–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vigano P, Candiani M, Monno A, Giacomini E, Vercellini P, Somigliana E. Time to redefine endometriosis including its pro-fibrotic nature. Hum Reprod. 2018;33:347–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meng XM, Nikolic-Paterson DJ, Lan HY. TGF-beta: the master regulator of fibrosis. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2016;12:325–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Young VJ, Ahmad SF, Duncan WC, Horne AW. The role of TGF-beta in the pathophysiology of peritoneal endometriosis. Hum Reprod Update. 2017;23:548–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matsuzaki S, Pouly JL, Canis M. Persistent activation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 via interleukin-6 trans-signaling is involved in fibrosis of endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2022;37:1489–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koninckx PR, Fernandes R, Ussia A, Schindler L, Wattiez A, Al-Suwaidi S, Amro B, Al-Maamari B, Hakim Z, Tahlak M. Pathogenesis based diagnosis and treatment of endometriosis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;12: 745548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Russo JW, Castellot JJ. CCN5: biology and pathophysiology. J Cell Commun Signal. 2010;4:119–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang L, Li Y, Liang C, Yang W. CCN5 overexpression inhibits profibrotic phenotypes via the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in lung fibroblasts isolated from patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and in an in vivo model of lung fibrosis. Int J Mol Med. 2014;33:478–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yoon A, Im S, Lee J, Park D, Jo DH, Kim JH, Kim JH, Park WJ. The matricellular protein CCN5 inhibits fibrotic deformation of retinal pigment epithelium. PLoS ONE. 2018;13: e0208897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu H, Li P, Liu M, Liu C, Sun Z, Guo X, Zhang Y. CCN2 and CCN5 exerts opposing effect on fibroblast proliferation and transdifferentiation induced by TGF-beta. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2015;42:1207–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jeong D, Lee MA, Li Y, Yang DK, Kho C, Oh JG, Hong G, Lee A, Song MH, LaRocca TJ, et al. Matricellular protein CCN5 reverses established cardiac fibrosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67:1556–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bae SJ, Jo Y, Cho MK, Jin JS, Kim JY, Shim J, Kim YH, Park JK, Ryu D, Lee HJ, et al. Identification and analysis of novel endometriosis biomarkers via integrative bioinformatics. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13: 942368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu M, Chen X, Chang QX, Hua R, Wei YX, Huang LP, Liao YX, Yue XJ, Hu HY, Sun F, et al. Decidual small extracellular vesicles induce trophoblast invasion by upregulating N-cadherin. Reproduction. 2020;159:171–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun YB, Qu X, Howard V, Dai L, Jiang X, Ren Y, Fu P, Puelles VG, Nikolic-Paterson DJ, Caruana G, et al. Smad3 deficiency protects mice from obesity-induced podocyte injury that precedes insulin resistance. Kidney Int. 2015;88:286–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li J, Dai Y, Zhu H, Jiang Y, Zhang S. Endometriotic mesenchymal stem cells significantly promote fibrogenesis in ovarian endometrioma through the Wnt/beta-catenin pathway by paracrine production of TGF-beta1 and Wnt1. Hum Reprod. 2016;31:1224–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee MS, Lee J, Kim YM, Lee H. The metastasis suppressor CD82/KAI1 represses the TGF-beta (1) and Wnt signalings inducing epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition linked to invasiveness of prostate cancer cells. Prostate. 2019;79:1400–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hu Y, Wang Q, Yu J, Zhou Q, Deng Y, Liu J, Zhang L, Xu Y, Xiong W, Wang Y. Tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase 5 promotes pulmonary fibrosis by modulating beta-catenin signaling. Nat Commun. 2022;13:114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dzialo E, Tkacz K, Blyszczuk P. Crosstalk between the TGF-beta and WNT signalling pathways during cardiac fibrogenesis. Acta Biochim Pol. 2018;65:341–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burney RO. Fibrosis as a molecular hallmark of endometriosis pathophysiology. Fertil Steril. 2022;118:203–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee JH, Massague J. TGF-beta in developmental and fibrogenic EMTs. Semin Cancer Biol. 2022;86:136–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bernacchioni C, Capezzuoli T, Vannuzzi V, Malentacchi F, Castiglione F, Cencetti F, Ceccaroni M, Donati C, Bruni P, Petraglia F. Sphingosine 1-phosphate receptors are dysregulated in endometriosis: possible implication in transforming growth factor beta-induced fibrosis. Fertil Steril. 2021;115:501–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Budi EH, Schaub JR, Decaris M, Turner S, Derynck R. TGF-beta as a driver of fibrosis: physiological roles and therapeutic opportunities. J Pathol. 2021;254:358–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Afrisham R, Farrokhi V, Ayyoubzadeh SM, Vatannejad A, Fadaei R, Moradi N, Jadidi Y, Alizadeh S. CCN5/WISP2 serum levels in patients with coronary artery disease and type 2 diabetes and its correlation with inflammation and insulin resistance; a machine learning approach. Biochem Biophys Rep. 2024;40: 101857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zolfaghari S, Kaasboll OJ, Ahmed MS, Line FA, Hagelin EMV, Monsen VT, Attramadal H. Tissue distribution and transcriptional regulation of CCN5 in the heart after myocardial infarction. J Cell Commun Signal. 2022;16:377–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nlandu-Khodo S, Neelisetty S, Phillips M, Manolopoulou M, Bhave G, May L, Clark PE, Yang H, Fogo AB, Harris RC, et al. Blocking TGF-beta and beta-catenin epithelial crosstalk exacerbates CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28:3490–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cai J, Liu Z, Huang X, Shu S, Hu X, Zheng M, Tang C, Liu Y, Chen G, Sun L, et al. The deacetylase sirtuin 6 protects against kidney fibrosis by epigenetically blocking beta-catenin target gene expression. Kidney Int. 2020;97:106–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Milara J, Ballester B, Montero P, Escriva J, Artigues E, Alos M, Pastor-Clerigues A, Morcillo E, Cortijo J. MUC1 intracellular bioactivation mediates lung fibrosis. Thorax. 2020;75:132–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shen M, Liu X, Zhang H, Guo SW. Transforming growth factor beta1 signaling coincides with epithelial–mesenchymal transition and fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transdifferentiation in the development of adenomyosis in mice. Hum Reprod. 2016;31:355–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frangogiannis N. Transforming growth factor-beta in tissue fibrosis. J Exp Med. 2020;217: e20190103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen DQ, Cao G, Zhao H, Chen L, Yang T, Wang M, Vaziri ND, Guo Y, Zhao YY. Combined melatonin and poricoic acid A inhibits renal fibrosis through modulating the interaction of Smad3 and beta-catenin pathway in AKI-to-CKD continuum. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2019;10:2040622319869116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Du Y, Wang X, Li L, Hao W, Zhang H, Li Y, Qin Y, Nie S, Christopher TA, Lopez BL, et al. miRNA-mediated suppression of a cardioprotective cardiokine as a novel mechanism exacerbating post-MI remodeling by sleep breathing disorders. Circ Res. 2020;126:212–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xue J, Lin X, Chiu WT, Chen YH, Yu G, Liu M, Feng XH, Sawaya R, Medema RH, Hung MC, Huang S. Sustained activation of SMAD3/SMAD4 by FOXM1 promotes TGF-beta-dependent cancer metastasis. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:564–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ramazani Y, Knops N, Elmonem MA, Nguyen TQ, Arcolino FO, van den Heuvel L, Levtchenko E, Kuypers D, Goldschmeding R. Connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) from basics to clinics. Matrix Biol. 2018;68–69:44–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Valle-Tenney R, Rebolledo DL, Lipson KE, Brandan E. Role of hypoxia in skeletal muscle fibrosis: synergism between hypoxia and TGF-beta signaling upregulates CCN2/CTGF expression specifically in muscle fibers. Matrix Biol. 2020;87:48–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available based on reasonable requests.