Abstract

A gadolinium-based contrast agent (GBCA) disulfide homodimer (Gd3+SS) has been incorporated into a lipoic acid (LA)-based hydrogel (Gd3+Gel) for enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). This study evaluates the magnetic properties and in vitro behavior of Gd3+Gel for potential applications in tracking internal injuries. Results indicate a direct shortening in the relaxation rate with greater magnitude of LA polymerization and a 2.8-fold enhancement in relaxivity (r1) at 1.4 T when Gd3+SS was conjugated into the hydrogel. This effect is attributed to a significant increase in the rotational correlation time (τr) from 0.22 ± 0.05 ns (Gd3+SS) to 6 ± 1 ns (Gd3+Gel). Retention studies confirm that Gd3+SS remains covalently within the hydrogel, with retention of 64.7 ± 1.9% for Gd3+SS and 14.0 ± 1.4% for noncovalent binding gadoterate. The hydrogel relaxation rate (1/T1) increases from 1.1 to 3.5 s−1 at 7 T from blank gel to Gd3+Gel (0.24 mM Gd3+). Cell studies show that PC3-PIP and RAW 264.7 cells maintain high viability with Gd3+SS but exhibit reduced viability with Gd3+Gel, consistent with known lipoic acid effects on immortalized cell lines. Cellular uptake studies using ICP-MS and confocal fluorescence microscopy confirm that monomeric Gd3+SS is readily internalized, whereas Gd3+Gel significantly limits diffusion and uptake. Rheology was conducted to determine the zero-shear viscosity of the LA hydrogel at various concentrations of LA. These findings suggest that the LA hydrogel scaffold enhances MRI contrast, minimizes leaching, and is easily injectable. Gd3+Gel is a promising tool for potential targeted imaging and controlled uptake during healing processes.

Keywords: gadolinium, lipoic acid, hydrogel, relaxivity, MRI

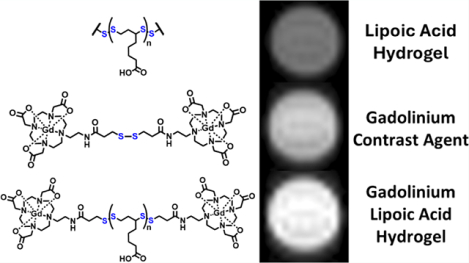

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a powerful tool in clinical diagnostics with excellent spatial resolution, lack of invasiveness, and nonionizing radiation.1 Gadolinium-based contrast agents (GBCAs) allow for improved enhancement of T1-weighted MRI.2–5 Current advances in GBCAs have focused on improving MRI sensitivity due to the lack thereof compared to other imaging modalities.1,2,6 Several approaches have been developed to enhance the relaxivity (r1) of GBCAs, increase the accumulation of the GBCAs ([Gd3+]), or a combination of both according to eq 1:

| (1) |

where 1/T1,obs is the observed 1H relaxation time, [Gd3+] is the local concentration of GBCA, and 1/T1,d is the diamagnetic background. In this study, we investigate a GBCA conjugated to a lipoic acid (LA)-based hydrogel for potential fate-mapping. Hydrogel conjugation also increases the r1 of the GBCA probe through a slowing of the rotational correlation time (τr). The GBCA concentration in our design is easily tunable during the LA hydrogel synthesis.

Hydrogels are porous polymers containing channels of water that have shown promising results in biomedical applications,7–9 and LA is a naturally occurring metabolite, essential for aerobic metabolism and redox homeostasis.10 LA hydrogels are therefore highly biocompatible and offer a combination of therapeutic effects including excellent external wound healing, antibacterial activity, and anti-inflammatory properties.8,11,12 Hydrogels have been used for controlled release of a drug or an imaging agent.13–15 However, there has been minimal progress in investigating the hydrogels for monitoring in vivo injuries. Several hydrogels have been used to investigate various MRI properties,16–20 with few studies of Gd3+-conjugated hydrogels for T1-weighted imaging9,21–25 and none looking at LA-based hydrogels. LA hydrogels use a simple linking of disulfide bonds from the favorable ring opening of a five-membered 1,2-dithiolane ring to form linear chains with hydrophilic carboxylate side chains interacting with water and Tris base counterions. This allows for facile hydrogel derivatization and tunability by the use of substances containing a thiol or disulfide.

Disulfide and thiol functional GBCAs have previously been investigated for their relaxivity and cell uptake/compatibility.26,27 Along with wound healing, the LA hydrogel and the disulfide GBCAs take advantage of common thiol-mediated uptake when reacting to exofacial protein thiols (EPTs). EPTs are essential for several metabolic activities, including cell signaling and cellular uptake.28 There has been extensive investigation into the passive and active thiol-mediated uptake.29–31 These combined traits can be used to fate-map the healing process over time, imaging cells as they remove the hydrogel. In this work, we develop a disulfide GBCA by synthesizing a homodimer (Gd3+SS) and incorporating it into the LA hydrogel (Gd3+Gel) to investigate the relaxivity and in vitro properties (Scheme 1). To investigate the tailoring properties of the LA hydrogel further, we also developed a fluorescein isothiocyanate disulfide (FITC-SS and FITC-Gel) derivative for confocal microscopy.

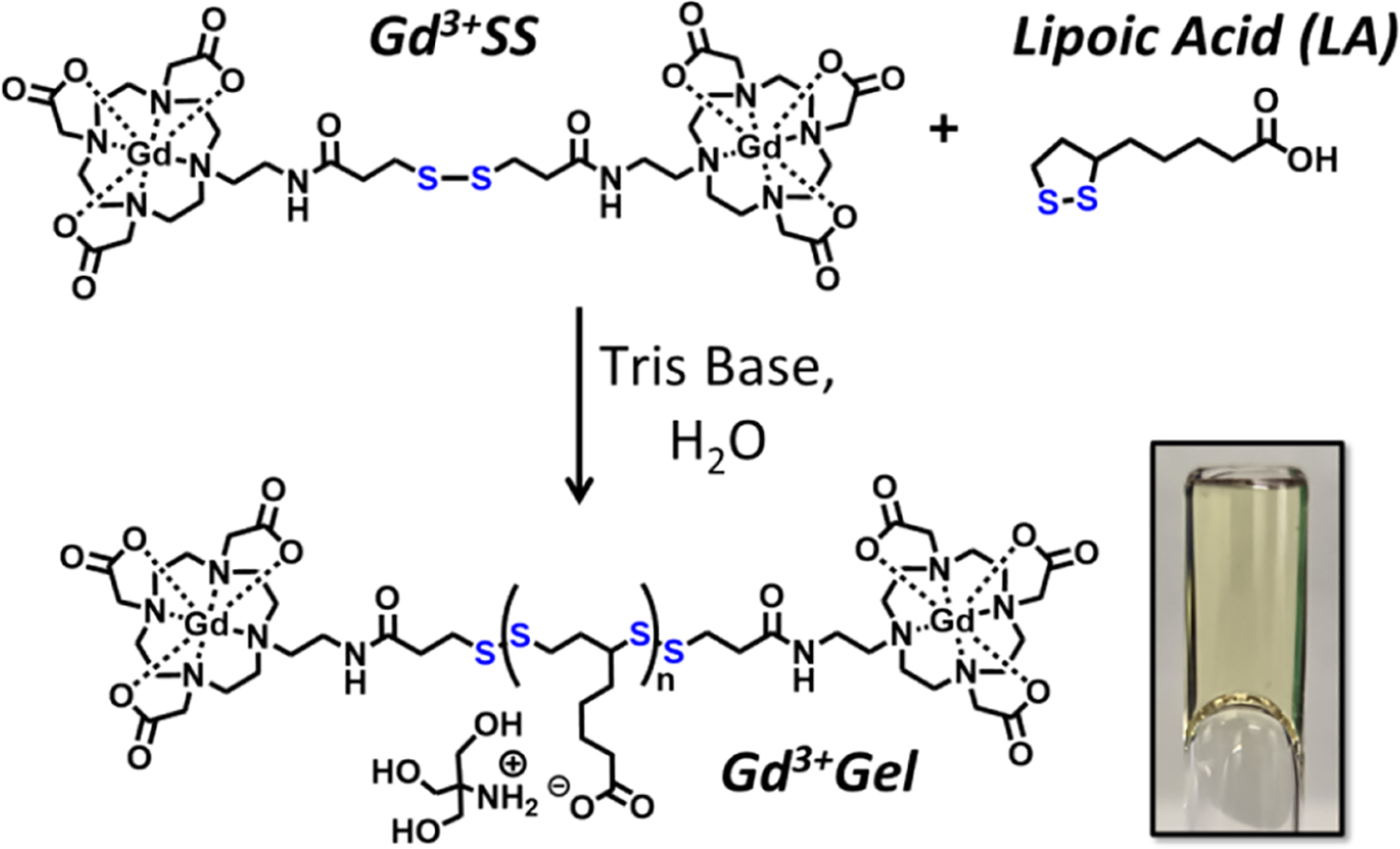

Scheme 1. Synthesis of the Gd3+Gel Using Base-Catalyzed Polymerizationa.

a The inset is a 1.38 M LA hydrogel upside down in a relaxivity tube to show the high viscosity that holds the gel in place.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Synthesis.

The amino-DO3A and FITC-SS were synthesized according to previous literature studies.32,33 The below is in reference to Scheme S1.

Tri-tert-butyl 2,2′,2″-(10-(2-(3-(Tritylthio)propanamido)ethyl)-1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7-triyl)triacetate (1).

The amino-DO3A (1.0480 g, 1.882 mmol), S-trityl mercaptopropionic acid (0.6635 g, 1.904 mmol), EDAC (0.7345 g, 3.846 mmol), and HOBt (0.5094 g, 3.801 mmol) were dissolved in DCM (20 mL) at 0 °C. DIPEA (1 mL, 5.806 mmol) was added. After 30 min, the reaction was taken to room temperature and allowed to stir overnight. The reaction was poured into a separation funnel with H2O (50 mL) and DCM (50 mL). The organic layer was removed, and the aqueous layer was washed once more with DCM (50 mL). The combined organic layers were dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated. The crude oil was purified by flash column chromatography with a gradient of 3 to 5 to 7.5% MeOH in DCM (7.5% MeOH in DCM, rf = 0.25) to give a viscous liquid (0.5559 g, 33% yield). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 7.38 (d, 6 H), 7.26 (t, 6H), 7.19 (t, 3H), 3.64–2.24 (m, 31 H), 1.45 (m, 27 H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 173.4, 172.5, 171.8, 169.9, 144.9, 129.6, 127.8, 126.5, 82.9, 82.5, 81.9, 66.5, 56.5, 55.6, 52.8, 50.4, 35.6, 34.9, 28.1, 28.1, 27.9, 27.7. HRMS (ESI-MS) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C50H73N5O7S 888.530; found 888.536.i

Gd3+SS.

1 (0.5559 g, 0.6267 mmol) was dissolved in a solution of TFA (10 mL), DCM (10 mL), and TIPS (0.39 mL, 1.91 mmol) at room temperature and stirred for 12 h whereupon DMSO (1 mL) was added. After 7 h, the reaction was concentrated down. The crude solid was resuspended in water (25 mL) and centrifuged down (15,000 rcf, 10 min, rt). The supernatant was decanted and filtered. The pH was adjusted to 6, and GdCl3·6H2O (0.2297 g, 0.626 mmol) was added. The pH was maintained at 6 until it stabilized. After 24 h, the pH was adjusted to 10+, filtered, and lyophilized. The crude was redissolved in Milli Q water and purified by HPLC method 1, with a retention time of 14.6 min. The solution was lyophilized to give a white powder (0.1533 g, 39% yield). HRMS (ESI-MS) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C38H62Gd2N10O14S2 1263.244; found 1263.246.

Formation of Hydrogels.

Tris base (250 mg) was dissolved in water (1 mL) with heat (90 °C), and the mixture was vortexed vigorously. Gd3+SS, gadoterate meglumine, or FITC-SS was added from stock solutions in water that were sterilized by passage through 0.2 μm sterile filters. LA was added (50, 125, 250, 500, or 750 mg for concentrations of 0.19, 0.44, 0.81, 1.38, or 1.82 M, respectively) while the solution was hot and aggressively vortexed. While hot, the hydrogel was molded into a syringe, relaxivity tube, or falcon tube. Small aliquots were taken to determine the final concentration of Gd3+ by ICP-MS for each hydrogel. The mold was frozen at – 20 °C overnight, thawed, and immediately tested. All relaxivity at 1.4 T was measured at 37 °C.

Retention.

Redundant 0.2 mM Gd3+, 1.38 M LA gels were made with Gd3+SS or gadoterate meglumine and molded in 15 mL falcon tubes. After formation, the hydrogels were swollen with an additional 5 mL of water using heat and vortexing. The hydrogels were centrifuged (10,000 rcf, 10 min, rt). The supernatant was filtered (0.2 μm), and the Gd3+ concentration was measured by ICP-MS. The experimental concentration was divided by the expected concentration from the dilution and subtracted from 100 to determine the percent of Gd3+ retention.

Relaxivity Overtime.

Nine redundant 0.2 mM Gd3+, 1.38 M LA hydrogels were made with Gd3+SS and molded into relaxivity tubes in three triplicate sets. The initial relaxivity of each set was measured after a single freeze–thaw cycle. Thereafter, each set was incubated at variable temperatures. One set was immediately refrozen upon measurement at −20 °C relaxivity and only thawed daily to measure. The other two sets were kept at either rt (21 °C) or 37 °C. T1 was measured for each set every 24 h for 10 days.

Rheology.

Rheometric measurements were performed using an Anton Paar Modular Compact Rheometer (MCR 302). Variable shear rate oscillatory experiments were performed at 37 °C from 1 × 10–3 Hz to 1 × 103 Hz using a 50 mm and 1° cone–plate geometry. A double gap fixture was used to perform shear experiments on a 0.19 M hydrogel and a single gap PP25 fixture for all other gels. Approximately 400 μL of gel was deposited onto the plate and surrounded by a water reservoir for humidity control. Four oscillatory experiments were conducted for each gel. Viscosities are reported as the average of four zero-shear viscosity values obtained for each gel. The measurement system was cleaned thoroughly with water before the gels. Acetone was also used for cleaning higher viscosity gels.

Cell Lines and Cultures.

PC3-PIP cells were provided by Professor James Basillion (Case Western Reserve University), and RAW 264.7 was purchased from the Northwestern Developmental Therapeutic Core, Evanston, IL. PC3-PIP cells were grown in RPMI 1640 medium and RAW 264.7 cells in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), l-glutamine, penicillin, and streptomycin. All cell lines were grown in a humidified incubator at 37 °C and 5% CO2 and harvested using 0.25% TrypLE. Scraping was needed for RAW 264.7 harvesting. Solutions were filtered through 0.2 μm sterile filters before use. For seeding, cells were counted by a hemocytometer.

Cell Uptake.

Cells were seeded at 3 × 105 cells per well in a six-well plate. For the time dependence, the cells were incubated overnight before dosing and cells were harvested at the designated time points over 48 h. For the dose dependence, the cells were immediately dosed at the time of seeding and incubated for 24 h before harvesting. Cells were dosed for Gd3+SS at 5, 20, or 200 μM Gd3+ or Gd3+Gel at 5 μM Gd3+/1.4 mM LA. The standard harvesting procedure is as follows: the medium was aspirated, and cells were washed with 1 mL of PBS and incubated in another 1 mL of PBS for 10 min. The PBS was aspirated, and the cells were incubated in 1 mL of 0.25% TrypLE for 10 min. The cells were resuspended in media and spun down (10 min, 250 rcf, 4 °C). The supernatant was aspirated, and the cells were resuspended in approximately 200 μL of media. A total of 40 μL was used for cell counting with a Gauva Easy Cyte Mini according to the manual. The remaining cells were used for ICP-MS to determine the concentration of Gd3+. All dilutions for ICP-MS were determined from the mass.

Cell Viability Assay.

Cells were seeded at 5000 cells per well in a 96-well plate. Triplicate treatments were added such that the well concentrations were as follows: Gd3+-SS (5, 10, 24, 50, 100, 200, 457.5, 915, or 1830 μM Gd3+) and Gd3+Gel (Gd3+ conc. of 3.8, 7.6, 15.2, 38.0, 76.0, 152, or 304 μM with the corresponding LA conc. of 1.1, 2.2, 4.4, 11, 22, 44, or 88 mM). A modified hydrogel was made to control the pH where 1 equiv of Tris base to LA was used to make a stock of 0.44 M LA/1.51 mM Gd3+ hydrogel. This stock and dilutions of this stock were added directly into the wells with the cells. The total working volume was 100 μL, and 200 μL of PBS was used on the outside wells to keep the working volume from evaporating. The cells were incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 24 h. The cell medium was aspirated, cells were washed with PBS, and fresh media was added. 20 μL of CellTiter-Glo 2.0 Reagent (Promega, Madison, WI) was added and the cells were incubated for 3.5 h before reading the absorbance at 490 nm. A background control without cells was subtracted from the sample absorbance, and values were normalized to the negative control wells.

In Vitro Fluorescence Imaging.

A total of 100,000 cells were plated on a 35 mm FluoroDish (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL, USA) and incubated overnight (37 °C, 5% CO2). Cells were dosed with the FITC-SS (10 μM in PBS) or with a pH-controlled FITC-Gel (5 μM FITC, 11 mM LA). The hydrogel dish was gently swirled to try and disperse the hydrogel. After 15 min of incubation (37 °C, 5% CO2), the medium was removed and the cells were washed thrice with PBS. FluoroBrite DMEM (Gibco, Waltham, MA) was added as the media. Live cells were imaged using a Nikon SoRa Spinning Disk confocal at a laser wavelength of 488 nm (intensity 15% for FITC-SS and 80% for FITC-Gel), objective of 60× (NA – 1.42) oil immersion, and using a Hamamatsu ORCA-Fusion Digital CMOS Camera. Z-stacking was used to enhance the images.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Synthesis of the Hydrogel.

The gadolinium agent was synthesized from a common tBuDO3A chelator34 with an amino arm32 for peptide coupling a trityl-protected mercaptopropionic acid. A deprotection with TFA, DCM, TIPS, and DMSO35 allowed for the formation of a disulfide bond, and a metalation gave Gd3+SS (Scheme S1). The disulfide form was chosen over the reduced thiol due to the enhanced stability in storage.

Gd3+SS was investigated by covalently conjugating into a lipoic acid-based hydrogel (Scheme 1). By using the proper chelator and covalently attaching the Gd3+SS, we further decrease its bioavailability to potential off targets compared to other hydrogels that attempted to chelate the Gd3+ with the hydrogel itslef.36 While several methods are currently in the literature for formation of the lipoic acid hydrogel,37–40 we adapted a method using Tris base.8 Tris base would be dissolved in water at either a molar equivalence or an excess of LA. A range of LA concentrations were used to measure their effects on physical, magnetic, and cellular properties. These gels were easily molded into a syringe, NMR tube, or falcon tube.

Relaxivity.

Water proton relaxation rates were measured at 1.4 T and 37 °C, conditions chosen to reflect common clinical MRI parameters. In the presence of lipoic acid (LA), a linear relationship (R2 = 0.9758) was observed between the longitudinal relaxation rate (1/T1) and the concentration of LA (Figure 1a). This result suggests that the extent of LA polymerization (i.e., “linking”) can be inferred from the relaxation behavior of water. As the LA concentration increases, longer polymer chains and higher polymer density likely enhance water–polymer interactions, raising the relaxation rate. An increase in LA concentration subsequently increases the macroscopic viscosity, giving rise to a similarly linear relationship with r1. This may indicate an accompanying rise in microscopic viscosity, further elevating the relaxation rate and prolonging the rotational correlation time (τr) of water molecules.41

Figure 1.

(a) Relaxation rates (1/T1 and 1/T2) of LA hydrogels without Gd3+SS and increasing concentrations of LA. (b) T1 and T2 of Gd3+Gels stored at room temperature, 37 °C, or −20 °C over time. The gels are 1.38 M LA. (c) Relaxivity of the Gd3+Gels with increasing concentrations of LA. (d) Percent retained from swelling and dilution of the LA hydrogels with gadoterate and Gd3+SS (**** = p < 0.001, Student’s t test). (e) r1 of Gd3+SS at different pH levels adjusted using NaOH and HCl. (f) Nuclear magnetic resonance dispersion (NMRD) of Gd3+SS and 1.38 M LA Gd3+Gel. All relativities are per Gd3+ concentration.

Several synthesis parameters were examined to determine whether they influenced the degree of LA linking specifically, extended stirring times, and immediate heating after LA addition. Neither procedure altered the final extent of cross-linking (see the Supporting Information). However, storing Gd3+-labeled hydrogels (Gd3+Gels) under different conditions—room temperature, 37 °C, and repeated freeze–thaw cycles at −20 °C—revealed that elevated temperatures promote greater cross-linking (Figure 1b). All T1 measurements were conducted at 37 °C, with frozen samples thawed just long enough for measurement before being refrozen. Over time, a slow decrease in T1 was observed for frozen gels, whereas samples kept at room temperature or 37 °C reached a near-plateau in T1 after about 1 day. Although heat-induced linking of LA-based materials is well-documented,39 its direct demonstration via T1 relaxation in LA hydrogels has not been previously reported. These findings highlight the sensitivity of T1 to polymerization and the potential for the temperature to accelerate hydrogel formation.

Despite hydrogels being highly attractive for in vivo applications—owing to their ability to carry aqueous cargo and capacity for mobility—there are comparatively few reports of Gd3+-conjugated hydrogels designed specifically for T1-weighted MRI.9,21–24 Across all tested samples, Gd3+Gels consistently exhibited a T1/T2 ratio of 1.49 ± 0.04, characteristic of GBCAs.

All subsequent r1 measurements were performed immediately after the first thaw to maintain consistency across the samples. The monomeric Gd3+SS exhibited an r1 of 7.3 ± 0.2 mM−1 s−1 at 1.4 T and 37 °C, which is slightly higher than a similar monomeric analogue.42 This modest increase in r1 is attributed to the larger molecular mass of Gd3+SS compared to the simpler monomer.24 When Gd3+SS was incorporated into the LA hydrogel (Gd3+Gel), the r1 more than doubled, reaching 20.2 ± 0.2 mM−1 s−1 at 1.4 T and 37 °C for the hydrogel containing 1.38 M LA. Increasing the LA content in the hydrogel continued to elevate r1, presumably due to partial immobilization of Gd3+SS by the denser polymer network (Figure 1c). However, the correlation between r1 and LA concentration in Gd3+Gels was somewhat lower (R2 = 0.8455) than the near-linear relationship seen with 1/T1 versus LA concentration alone.

To verify whether this enhancement in r1 was an inherent feature of covalent Gd3+ attachment, a control experiment was conducted with commercially available gadoterate meglumine. When both gadoterate and Gd3+SS were incorporated into hydrogels at the same LA concentration (1.38 M), they showed comparable r1 values (19.6 ± 0.5 and 20.2 ± 0.2 mM−1 s−1, respectively; see Table S2). Interestingly, although gadoterate and Gd3+SS differ in their free-solution r1 (gadoterate r1 = 3.32 ± 0.13 mM−1 s−1),43 both converge to similar relaxivities once embedded in the hydrogel matrix.

A swelling–dilution experiment provided further insights into the covalent binding of Gd3+SS. Under these conditions, 64.7 ± 1.9% of Gd3+SS was retained compared to only 14.0 ± 1.4% of noncovalently incorporated gadoterate (Figure 1d), a statistically significant difference (p < 0.001). These data confirm that Gd3+SS is more strongly retained within the LA-based hydrogel network, consistent with covalent conjugation. Despite the difference in binding modes, however, both gadoterate and Gd3+SS displayed similar r1 values when entrapped in the hydrogel at equivalent LA concentrations, indicating that the presence or absence of covalent bonds does not significantly affect the relaxivity in these particular formulations.

The pH sensitivity of Gd3+SS was evaluated. The standard Gd3+Gel dilutions kept the concentration of Tris base constant while varying the LA concentration. This would make the lower concentrations of LA more basic, which could potentially impact the relaxation rate of the Gd3+Gel. The pH titration showed no significant shift in the basic region of the Tris buffer (Figure 1e).

Nuclear magnetic resonance dispersion (NMRD) was used to better understand the relaxation mechanisms in Gd3+Gel (Figure 1f and Table S1). While the relaxivity profile for the Gd3+SS is characterized by a single dispersion (common for fast reorienting small Gd3+ complexes), the appearance of a relaxivity peak around 20 MHz in the Gd3+Gel clearly points to a τr enhancement effect near the clinical field strength. Fitting of the NMRD curves with the Solomon–Bloembergen–Morgan (SBM) model shows that the correlation time modulating relaxation can be ascribed for 10–25% to a longer τr, which increases from 0.22 ± 0.05 to 6 ± 1 ns on passing from Gd3+SS to Gd3+Gel. Additionally, there is a faster reorientation time (τl), which passes from 23 ± 3 to 40 ± 5 ps for the remaining 90–75%. This latter time can be ascribed to the large residual internal mobility of the DO3A-derivative allowed by the flexible linker. The obtained values agree with what is expected from the structure of the Gd3+SS monomer and with the slowing due to gel formation. In this analysis, for both systems, two water molecules that are coordinated42 to the Gd3+ ion have been considered in fast exchange, in agreement with the temperature dependence of the profiles. Remarkably, from this analysis, it results that the relaxivity peak observed for the Gd3+Gel is only determined by the small fraction modulated by the longer reorientation time. Therefore, we predict that significantly higher relaxivity values could be obtained by reducing the fast internal mobility through formation of gels that can further restrict the motion.

7 T phantoms were taken to determine the enhancement effects of the gel at higher field strengths (Table 1). The gel without Gd3+SS already observes a four-fold rate enhancement of the T1 over the blank PBS. When adding Gd3+SS (0.24 mM Gd3+) to the 1.38 M LA gel, there is a 10.5-fold rate enhancement. This Gd3+Gel is shorter in T1 than equivalent concentrations of Gd3+SS, demonstrating improvements in other magnetic properties besides the τr boost. Overall, Gd3+Gel sees a broad relaxivity enhancement.

Table 1.

7 T Phantoms (500 ms Delay for Representation) of Gd3+SS and Hydrogels with and without Inclusion of Gd3+SS at Room Temperature

| Water | Hydrogel | Gd3+SS | Gd3+Gel | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phantoms (500 ms) |

|

|

|

|

| Gd3+ (mM) | 0 | 0 | 0.26 | 0.24 |

| LA (M) | 0 | 1.38 | 0 | 1.38 |

| T1 (ms) | 2706 ± 15 | 662 ± 17 | 328.4 ± 1.4 | 258 ± 4 |

| T2 (ms) | 240 ± 18 | 84 ± 2 | 130 ± 3 | 41.0 ± 0.5 |

Rheology.

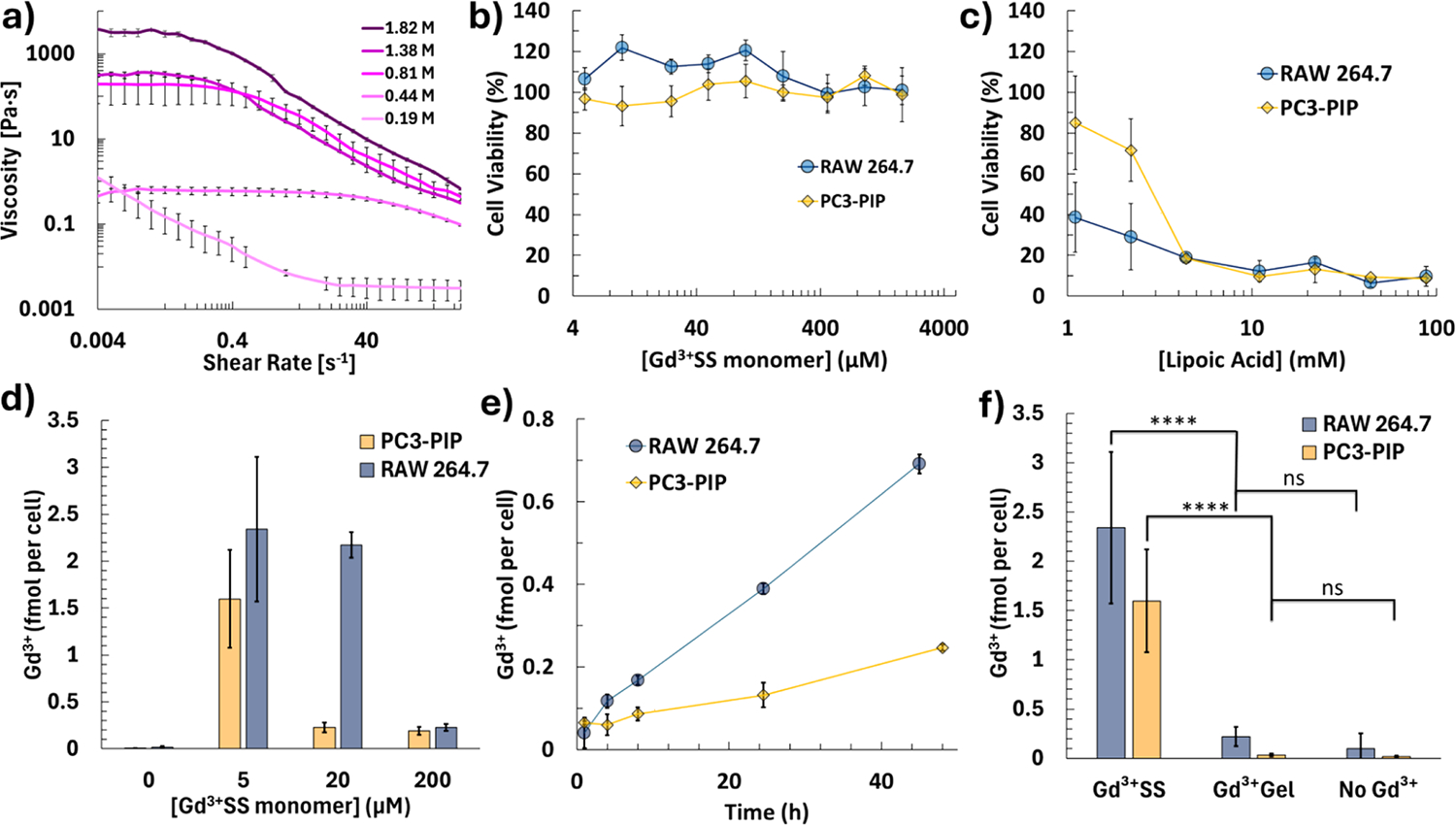

While the Gd3+SS is a terminal group of the linear disulfide polymer, we saw no significant difference in rheology at the highest ratio of Gd3+SS to LA concentration (0.002). The gels showed non-Newtonian properties, by having dynamic viscosities over a range of shear rates. The LA hydrogels demonstrated constant viscosity at low shear rates (<1 rad/s) and an inversely linear viscosity at high shear rates (>10 radians/s) when plotted logarithmically, except for the most diluted 0.19 M LA hydrogel (Figure 2a). Zero-shear viscosity values were determined by averaging the viscosity values at a low shear rate for each gel except the 0.19 M LA (Table S4). The observed decrease in viscosity with an increasing shear rate is a characteristic shear-thinning behavior.44 This makes these gels amenable to in vivo applications, as they can be tailored to extrude through small gauge needles for injections. LA hydrogels could be a good alternative to extracellular matrix hydrogels, which are being investigated to accelerate healing for ischemic strokes and hemorrhage.45,46

Figure 2.

(a) Rheology of the LA hydrogels with different LA concentrations and an increasing shear rate. Cell viability with (b) Gd3+SS and (c) Gd3+Gels. (d) Dose-dependent cell uptake via ICP-MS when incubated after 24 h and (e) time dependence when incubated in 200 μM Gd3+SS. (f) Cell uptake of 5 μM Gd3+ of Gd3+SS and Gd3+Gels (1.4 mM LA) incubated after 24 h (**** = p < 0.001, ns = not significant, Student’s t test). All dosages are per Gd3+ concentration, and “No Gd3+” represents the limit of detection.

Uniquely, the relaxivity had a linear relationship with the logarithm of the macroscopic viscosity, which increases exponentially with LA concentration (r1, R2 = 0.9959, Figure S1). A previous study was conducted to measure the viscosity using MRI empirically but did not utilize a GBCA,47 despite the role of viscosity in MRI contrast.48,49 Future studies could be conducted to measure the microscopic viscosity using magnetic resonance.

Cell Viability.

The cell viability of the Gd3+SS and Gd3+Gel was then explored using the CellTiter-Glo luminescence assay. PC3-PIP was selected as an epithelial cell line and RAW 264.7 macrophages for their active uptake of antigens. Both cell lines are known to express EPTs.50,51 Similar to previous Gd3+ disulfide and thiol-containing MR agents,27 Gd3+SS shows no significant cell death (Figure 2b). The LA hydrogel however shows cell death, which is common for immortalized and tumorigenic cell lines (Figure 2c).52 LA is not toxic in normal cell lines and is even used as a nutritional supplement with several preliminary studies showing high safety profiles.10 A similar lipoic acid hydrogel has shown promise with accelerated healing when replacing an excised tumor.38

Modified Gd3+Gels were used to control for the pH by using equimolar Tris base to LA and all dilutions done in PBS. Even though the Gd3+Gel constrains much of the lipoic acid and Gd3+SS, the linking is not complete as the yellow color indicates that five-membered, 1,2-dithiolane rings remain.39

This means some dosages of the surrounding cells of the gel are still exposed to lower concentrations of free LA and likewise any other thiol or disulfide monomer.

Cell Uptake.

This property is observed by ICP-MS. The overall LA was kept at 1.4 mM or lower where each cell line would still be viable enough to measure after 24 h. When both cell lines are dosed with Gd3+SS, there is significant cell uptake, like previous sulfur uptake probes.26,27 However, previous probes did not test a wide range of concentrations, specifically lower micromolar concentrations where there is a clear nonlinear dosage dependence with Gd3+SS (Figure 2d). Uniquely, lower concentrations saw higher cell uptake than those with higher dosages. Several peptides with thiols have been investigated for cell uptake but they lack in dosages at higher ranges,30,31 whereas previous Gd3+ disulfide agents only dosed concentrations higher than 1 mM.27 The previous study did cell uptake with increasing concentrations of a reductant, tris(2-carboxyethyl) phosphine (TCEP), which showed that the highest concentration of TCEP had a lower Gd3+ uptake.26 This nonlinear trend could be due to the sensitive regulatory processes that ETC’s have on cellular signals, as this is a main mode of transportation for viruses,53 and should be taken into account when designing future agents.

When a time dependence curve is performed, the 20 μM concentration sees a higher overall uptake but no clear trend (Figure S2), whereas the larger 200 μM dose sees a lower yet steady linear increase (Figure 2e). This characteristic is reflected when dosed with 5 μM Gd3+ in Gd3+SS and Gd3+Gels. RAW 264.7 and PC3-PIP see 2.3 ± 0.8 and 1.6 ± 0.5 fmol of Gd3+ per cell with the Gd3+SS, respectively, whereas the Gd3+Gel uptake is not different from negative controls (Figure 2f). This is again likely due to Gd3+ being constrained to the Gd3+Gel.

Confocal fluorescence microscopy was used to investigate uptake, where a similar FITC disulfide (FITC-SS) was synthesized and conjugated into the LA hydrogel (FITC-Gel). The cells were incubated for 15 min with FITC-SS or FITC-Gel (10 μM FITC). The imaging further confirmed the uptake results from the ICP-MS experiments where FITC-SS saw intracellular accumulation compared to the FITC-Gel (Figure 3). The morphologies of the FITC-Gel exposed cells exhibit cells under stress or apoptotic as they become rounder and/or bleb. There is additional evidence of FITC-Gel debris showing the limiting diffusion that the hydrogel produces.

Figure 3.

Bright field and confocal fluorescence microscopy of PC3-PIP and RAW 264.7 incubated in 10 μM FITC in either FITC-SS or FITC-Gel (1.4 mM LA) after 15 min. Note that the debris in the FITC-Gel cells has more round morphologies of stressed cells, whereas the FITC-SS cells exhibit more typical morphology and brighter fluorescence.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, the GBCA was covalently incorporated into a lipoic acid (LA) hydrogel to explore its potential for mapping the healing process of internal injuries. When the LA hydrogel and the Gd3+SS compound were combined, they synergistically improve water relaxation, evident by a direct increase in the relaxation rate with greater linking of the LA polymer. In cell studies, PC3-PIP and RAW 264.7 cells remained highly viable when exposed to the monomer (Gd3+SS) but not with Gd3+Gel, a response typical of immortalized cell lines in the presence of lipoic acid.

The minimal leaching observed in LA-based hydrogels confers an advantage for targeted imaging and localized therapy rather than presenting a limitation. By retaining the imaging agent (e.g., Gd3+ complexes) within the hydrogel, only cells in direct contact with the matrix take up the agent, allowing for precise, site-specific visualization of tissue–hydrogel interactions. These preliminary findings highlight the potential of LA-based hydrogels as multifunctional platforms that present robust T1-weighted contrast, offering promising avenues for future biomedical applications.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsabm.5c00584.

Materials, further methods, and characterizations (ICP-MS, hydrogel methods, relaxivity, rheology, cell studies, synthesis, and small molecule characterization) (PDF)

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was funded [or funded in part] by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) grant number R01 NS-1222768-01, and we gratefully thank Lucia Calucci (ICCOM-CNR, Pisa, Italy) for her assistance in the NMRD experiments, performed at CNR, Istituto di Chimica dei Composti Organometallici, Pisa. A.R.B. gratefully acknowledges the NSF Graduate Research Fellowship Grant no. DGE-2234667. This work made use of the IMSERC MS and NMR facility at Northwestern University, which has received support from the Soft and Hybrid Nanotechnology Experimental (SHyNE) Resource (NSF ECCS-2025633), Northwestern University. Metal analysis was performed at the Northwestern University Quantitative Bioelement Imaging Center generously supported by NASA Ames Research Center NNA06CB93G. This work made use of the MatCI Facility supported by the MRSEC program of the National Science Foundation (DMR-2308691) at the Materials Research Center of Northwestern University. Microscopy was performed at the Biological Imaging Facility at Northwestern University (RRID:SCR_017767), graciously supported by the Chemistry for Life Processes Institute, the NU Office for Research, and the Department of Molecular Biosciences.

Footnotes

Complete contact information is available at: https://pubs.acs.org/10.1021/acsabm.5c00584

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Contributor Information

Andrew R. Brotherton, Department of Chemistry, Evanston, Illinois 60208-3113, United States

Bennett Phillips-Sorich, Department of Chemistry, Evanston, Illinois 60208-3113, United States.

Naedum DomNwachukwu, Department of Biomedical Engineering, Evanston, Illinois 60208, United States; Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, Chicago, Illinois 60611, United States.

Matthew D. Bailey, Department of Chemistry, Evanston, Illinois 60208-3113, United States

Aarnav S. Patel, Department of Chemistry, Evanston, Illinois 60208-3113, United States

Claudio Luchinat, Department of Chemistry “Ugo Schiff” and Magnetic Resonance Center (CERM), University of Florence, Sesto Fiorentino 50019, Italy; Consorzio Interuniversitario Risonanze Magnetiche Metallo Proteine (CIRMMP), 50019 Sesto Fiorentino, Italy.

Giacomo Parigi, Department of Chemistry “Ugo Schiff” and Magnetic Resonance Center (CERM), University of Florence, Sesto Fiorentino 50019, Italy; Consorzio Interuniversitario Risonanze Magnetiche Metallo Proteine (CIRMMP), 50019 Sesto Fiorentino, Italy;.

Thomas J. Meade, Department of Chemistry, Evanston, Illinois 60208-3113, United States; Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, Chicago, Illinois 60611, United States; Department of Molecular Bioscience, Neurobiology, and Radiology, Evanston, Illinois 60208, United States

REFERENCES

- (1).Wahsner J; Gale EM; Rodriguez-Rodriguez A; Caravan P Chemistry of MRI Contrast Agents: Current Challenges and New Frontiers. Chem. Rev 2019, 119 (2), 957–1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Merbach A; Helm L; Tóth É The Chemistry of Contrast Agents in Medical Magnetic Resonance Imaging 2nd ed.; Wiley; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- (3).Brotherton AR; Mohamed SN; Meade TJ Synthesis and relaxivity of gadolinium-based DOTAGA conjugated 3-phosphoglycerate. Dalton Transactions 2024, 53 (44), 17777–17782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Kaster MA; Levasseur MD; Edwardson TGW; Caldwell MA; Hofmann D; Licciardi G; Parigi G; Luchinat C; Hilvert D; Meade TJ Engineered Nonviral Protein Cages Modified for MR Imaging. ACS Appl. Bio Mater 2023, 6, 591–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Li H; Meade TJ Molecular Magnetic Resonance Imaging with Gd(III)-Based Contrast Agents: Challenges and Key Advances. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141 (43), 17025–17041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Caravan P; Ellison JJ; McMurry TJ; Lauffer RB Gadolinium(III) chelates as MRI contrast agents: Structure, dynamics, and applications. Chem. Rev 1999, 99 (9), 2293–2352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Liang YP; He JH; Guo BL Functional Hydrogels as Wound Dressing to Enhance Wound Healing. ACS Nano 2021, 15 (8), 12687–12722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Chen C; Yang X; Li SJ; Zhang C; Ma YN; Ma YX; Gao P; Gao SZ; Huang XJ Tannic acid-thioctic acid hydrogel: a novel injectable supramolecular adhesive gel for wound healing. Green Chem. 2021, 23 (4), 1794–1804. [Google Scholar]

- (9).Liu J; Wang K; Luan J; Wen Z; Wang L; Liu ZL; Wu GY; Zhuo RX Visualization of in situ hydrogels by MRI in vivo. J. Mater. Chem. B 2016, 4 (7), 1343–1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Fogacci F; Rizzo M; Krogager C; Kennedy C; Georges CMG; Knežević T; Liberopoulos E; Vallée A; Pérez-Martínez P; Wenstedt EFE; Šatrauskiene A; Vrablík M; Cicero AFG Safety Evaluation of α-Lipoic Acid Supplementation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Placebo-Controlled Clinical Studies. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Lei R; Gu MB; Li JY; Wang WJ; Yu Q; Ali R; Pang JJ; Zhai ML; Wang Y; Zhang KX; Yin JB; Xu JH Lipoic acid/trometamol assembled hydrogel as injectable bandage for hypoxic wound healing at high altitude. Chem. Eng. J 2024, 489, No. 151499. [Google Scholar]

- (12).Zeng JJ; Fang HW; Pan HY; Gu HJ; Zhang KX; Song YL Rapidly Gelled Lipoic Acid-Based Supramolecular Hydrogel for 3D Printing of Adhesive Bandage. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16 (40), 53515–53531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Ma B; Liu P; Zhang YF; Tang LJ; Zhao ZY; Ding Z; Wang TY; Dong TZ; Chen HW; Liu JF Hydrogel for slow-release drug delivery in wound treatment. Journal of Polymer Engineering 2024, 44 (9), 637–650. [Google Scholar]

- (14).Adams TJ; Brotherton AR; Molai JA; Parmar N; Palmer JR; Sandor KA; Walter MG Obtaining Reversible, High Contrast Electrochromism, Electrofluorochromism, and Photochromism in an Aqueous Hydrogel Device Using Chromogenic Thiazolothiazoles. Adv. Funct. Mater 2021, 31, 36. [Google Scholar]

- (15).Arifin DR; Kedziorek DA; Fu YL; Chan KWY; McMahon MT; Weiss CR; Kraitchman DL; Bulte JWM Microencapsulated Cell Tracking. NMR in Biomedicine 2013, 26 (7), 850–859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Zhu W; Chu C; Kuddannaya S; Yuan Y; Walczak P; Singh A; Song X; Bulte JWM In Vivo Imaging of Composite Hydrogel Scaffold Degradation Using CEST MRI and Two-Color NIR Imaging. Adv. Funct. Mater 2019, 29, 36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Dorsey SM; McGarvey JR; Wang H; Nikou A; Arama L; Koomalsingh KJ; Kondo N; Gorman JH; Pilla JJ; Gorman RC; Wenk JF; Burdick JA MRI evaluation of injectable hyaluronic acid-based hydrogel therapy to limit ventricular remodeling after myocardial infarction. Biomaterials 2015, 69, 65–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Kim JI; Kim B; Chun C; Lee SH; Song SC MRI-monitored long-term therapeutic hydrogel system for brain tumors without surgical resection. Biomaterials 2012, 33 (19), 4836–4842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Nguyen CTV; Chow SKK; Nguyen HN; Liu TS; Walls A; Withey S; Liebig P; Mueller M; Thierry B; Yang CT; Huang CJ Formation of Zwitterionic and Self-Healable Hydrogels via Amino-yne Click Chemistry for Development of Cellular Scaffold and Tumor Spheroid Phantom for MRI. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16 (28), 36157–36167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Carniato F; Ricci M; Tei L; Garello F; Furlan C; Terreno E; Ravera E; Parigi G; Luchinat C; Botta M Novel Nanogels Loaded with Mn(II) Chelates as Effective and Biologically Stable MRI Probes. Small 2023, 19, 42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Gallo E; Diaferia C; Di Gregorio E; Morelli G; Gianolio E; Accardo A Peptide-Based Soft Hydrogels Modified with Gadolinium Complexes as MRI Contrast Agents. Pharmaceuticals 2020, 13 (2), 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Courant T; Roullin VG; Cadiou C; Callewaert M; Andry MC; Portefaix C; Hoeffel C; de Goltstein MC; Port M; Laurent S; Vander Elst L; Muller R; Molinari M; Chuburu F Hydrogels Incorporating GdDOTA: Towards Highly Efficient Dual T1/T2MRI Contrast Agents. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2012, 51 (36), 9119–9122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Carniato F; Tei L; Botta M; Ravera E; Fragai M; Parigi G; Luchinat C 1H NMR Relaxometric Study of Chitosan-Based Nanogels Containing Mono- and Bis-Hydrated Gd(III) Chelates: Clues for MRI Probes of Improved Sensitivity. Acs Applied Bio Materials 2020, 3 (12), 9065–9072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Carniato F; Ricci M; Tei L; Garello F; Terreno E; Ravera E; Parigi G; Luchinat C; Botta M High Relaxivity with No Coordinated Waters: A Seemingly Paradoxical Behavior of Gd-(DOTP)5- Embedded in Nanogels. Inorg. Chem 2022, 61 (13), 5380–5387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Padovan S; Carrera C; Catanzaro V; Grange C; Koni M; Digilio G Glycol Chitosan Functionalized with a Gd(III) Chelate as a Redox-responsive Magnetic Resonance Imaging Probe to Label Cell Embedding Alginate Capsules. Chem.Eur. J 2021, 27 (48), 12289–12293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Menchise V; Digilio G; Gianolio E; Cittadino E; Catanzaro V; Carrera C; Aime S In Vivo Labeling of B16 Melanoma Tumor Xenograft with a Thiol-Reactive Gadolinium Based MRI Contrast Agent. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2011, 8 (5), 1750–1756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Digilio G; Menchise V; Gianolio E; Catanzaro V; Carrera C; Napolitano R; Fedeli F; Aime S Exofacial Protein Thiols as a Route for the Internalization of Gd(III)-Based Complexes for Magnetic Resonance Imaging Cell Labeling. J. Med. Chem 2010, 53 (13), 4877–4890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Yi MC; Khosla C Thiol-Disulfide Exchange Reactions in the Mammalian Extracellular Environment. In Annual Review of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, Prausnitz JM Ed. 2016; Vol. 7, pp 197–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Gasparini G; Sargsyan G; Bang EK; Sakai N; Matile S Ring Tension Applied to Thiol-Mediated Cellular Uptake. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2015, 54 (25), 7328–7331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Gasparini G; Bang EK; Molinard G; Tulumello DV; Ward S; Kelley SO; Roux A; Sakai N; Matile S Cellular Uptake of Substrate-Initiated Cell-Penetrating Poly(disulfide)s. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136 (16), 6069–6074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Laurent Q; Martinent R; Lim B; Pham AT; Kato T; López-Andarias J; Sakai N; Matile S Thiol-Mediated Uptake. Jacs Au 2021, 1 (6), 710–728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Gianolio E; Napolitano R; Fedeli F; Arena F; Aime S Poly-β-Cyclodextrin Based Platform for pH Mapping via a Ratiometric 19F/1H MRI Method. Chem. Commun 2009, No. 40, 6044–6046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Fouda AE; Gamage AK; Pflum MKH An Affinity-Based, Cysteine-Specific ATP Analog for Kinase-Catalyzed Cross-linking. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2021, 60 (18), 9859–9862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Mastarone DJ; Harrison VSR; Eckermann AL; Parigi G; Luchinat C; Meade TJ A Modular System for the Synthesis of Multiplexed Magnetic Resonance Probes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133 (14), 5329–5337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Wu FZ; Mayer JP; Gelfanov VM; Liu F; DiMarchi RD Synthesis of Four-Disulfide Insulin Analogs via Sequential Disulfide Bond Formation. J. Org. Chem 2017, 82 (7), 3506–3512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Wang C; Jing Y; Yu W; Gu J; Wei Z; Chen A; Yen Y; He X; Cen L; Chen A; Song X; Wu Y; Yu L; Tao G; Liu B; Wang S; Xue B; Li R Bivalent Gadolinium Ions Forming Injectable Hydrogels for Simultaneous In Situ Vaccination Therapy and Imaging of Soft Tissue Sarcoma. Adv. Healthcare Mater 2023, 12, 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Alraddadi MA; Chiaradia V; Stubbs CJ; Worch JC; Dove AP Renewable and recyclable covalent adaptable networks based on bio-derived lipoic acid. Polym. Chem 2021, 12 (40), 5796–5802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Jia MQ; Lu RL; Liu CK; Zhou XD; Li PF; Zhang SY In Situ Implantation of Chitosan Oligosaccharide-Doped Lipoic Acid Hydrogel Breaks the ‘Vicious Cycle’ of Inflammation and Residual Tumor Cell for Postoperative Skin Cancer Therapy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15 (27), 32824–32838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Shi CY; Zhang Q; Wang BS; Chen M; Qu DH Intrinsically Photopolymerizable Dynamic Polymers Derived from a Natural Small Molecule. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13 (37), 44860–44867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Yu Q; Fang ZY; Luan SF; Wang L; Shi HC Biological applications of lipoic acid-based polymers: an old material with new promise. J. Mater. Chem. B 2024, 12 (19), 4574–4583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Bertini I; Luchinat C; Parigi G; Ravera E NMR of Paramagnetic Molecules: Applications to Metallobiomolecules and Models. 2nd ed.; Sether C Elsevier; 2017; p 495 [Google Scholar]

- (42).Gündüz S; Vibhute S; Botár R; Kálmán FK; Tóth I; Tircsó G; Regueiro-Figueroa M; Esteban-Gómez D; Platas-Iglesias C; Angelovski G Coordination Properties of GdDO3A-Based Model Compounds of Bioresponsive MRI Contrast Agents. Inorg. Chem 2018, 57 (10), 5973–5986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Szomolanyi P; Rohrer M; Frenzel T; Noebauer-Hohmann IM; Jost G; Endrikat J; Trattnig S; Pietsch H Comparison of the Relaxivities of Macrocyclic Gadolinium-Based Contrast Agents in Human Plasma at 1.5, 3, and 7 T, and Blood at 3 T. Invest. Radiol 2019, 54 (9), 559–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Ricarte RG; Shanbhag S A tutorial review of linear rheology for polymer chemists: basics and best practices for covalent adaptable networks. Polym. Chem 2024, 15 (9), 815–846. [Google Scholar]

- (45).Ghuman H; Hitchens TK; Modo M A systematic optimization of 19F MR image acquisition to detect macrophage invasion into an ECM hydrogel implanted in the stroke-damaged brain. Neuroimage 2019, 202, No. 116090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Modo M; Ghuman H; Azar R; Krafty R; Badylak SF; Hitchens TK Mapping the acute time course of immune cell infiltration into an ECM hydrogel in a rat model of stroke using 19F MRI. Biomaterials 2022, 282, No. 121386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Goloshevsky AG; Walton JH; Shutov MV; de Ropp JS; Collins SD; McCarthy MJ Nuclear magnetic resonance imaging for viscosity measurements of non-Newtonian fluids using a miniaturized RF coil. Meas. Sci. Technol 2005, 16 (2), 513–518. [Google Scholar]

- (48).Swenson J; Jansson H; Bergman R Relaxation processes in supercooled confined water and implications for protein dynamics. Phys. Rev. Lett 2006, 96 (24), No. 247802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Marciani L; Gowland PA; Spiller RC; Manoj P; Moore RJ; Young P; Fillery-Travis AJ Effect of meal viscosity and nutrients on satiety, intragastric dilution, and emptying assessed by MRI. American Journal of Physiology-Gastrointestinal and Liver. Physiology 2001, 280 (6), G1227–G1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Garibaldi S; Barisione C; Marengo B; Ameri P; Brunelli C; Balbi M; Ghigliotti G Advanced Oxidation Protein Products-Modified Albumin Induces Differentiation of RAW264.7 Macrophages into Dendritic-Like Cells Which Is Modulated by Cell Surface Thiols. Toxins 2017, 9, 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Chaiswing L; Oberley TD Extracellular/Microenvironmental Redox State. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling 2010, 13 (4), 449–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Van de Mark K; Chen JS; Steliou K; Perrine SP; Faller DV α-lipoic acid induces p27Kip-dependent cell cycle arrest in non-transformed cell lines and apoptosis in tumor cell lines. J. Cell. Physiol 2003, 194 (3), 325–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Lim B; Cheng YY; Kato T; Pham AT; Le Du E; Mishra AK; Grinhagena E; Moreau D; Sakai N; Waser J; Matile S Inhibition of Thiol-Mediated Uptake with Irreversible Covalent Inhibitors. Helv. Chim. Acta 2021, 104 (8), No. e2100085. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.