Abstract

Background

The prognosis of colorectal cancer (CRC) varies significantly across different immune subtypes. This study aimed to develop a risk prediction model incorporating the tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) to improve prognosis assessment and predict immunotherapy response in CRC patients, given the significant variability in clinical outcomes across different immune subtypes.

Methods

CRC transcriptome data and corresponding clinical information were obtained from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses were employed to identify m6A-related long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) (mRLs). A risk model was constructed using least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) Cox regression and further validated through nomogram analysis, time-dependent receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves, and Kaplan-Meier survival analysis. Differences in immune infiltration scores and clinical characteristics between low-risk group (LRG) and high-risk group (HRG) were also investigated.

Results

An 11-mRL signature model was established based on their expression profiles in CRC and correlation with m6A regulatory factors. This model demonstrated strong predictive performance for OS, as confirmed by Kaplan-Meier analysis, ROC curves, and Cox regression. Notably, the HRG exhibited significantly higher infiltration of specific immune cells and elevated expression of immune checkpoints [programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1), programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1), and cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA4)] compared to the LRG. Furthermore, the two groups showed distinct responses to immunotherapy, suggesting potential utility in guiding immunosuppressant selection. A nomogram integrating m6A-immune signatures and clinicopathological variables was developed to individualize prognosis prediction.

Conclusions

This study constructed an mRLs risk model that effectively predicts CRC prognosis and immune profiles, offering a potential tool for personalized therapeutic decision-making.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer (CRC), tumor immune microenvironment (TIME), prognosis factors, m6A-immune-related long non-coding RNAs (m6A-immune-related lncRNAs)

Highlight box.

Key findings

• This study established a novel m6A-immune-related long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) risk model that effectively predicts colorectal cancer (CRC) prognosis, tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) characteristics, and immunotherapy response, offering a potential tool for personalized treatment strategies.

What is known and what is new?

• Prior studies link CRC prognosis to immune subtypes and TIME, with known roles for programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1)/ programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) and cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA4) in immunotherapy response. While m6A modification affects cancer biology, its integration with TIME remains unexplored.

• Key innovations include: (I) connecting m6A-related lncRNAs (mRLs) to TIME features (CD4+ T cells, macrophages) and checkpoint upregulation (PD-L1/CTLA4); (II) developing a clinical nomogram combining m6A-immune signatures with pathological variables. The work provides a practical tool for prognosis prediction and immunotherapy guidance in CRC.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• This study establishes an m6A-lncRNA-based risk model that integrates tumor-immune interactions to predict CRC prognosis and immunotherapy response. The findings advocate for: (I) clinical adoption of this 11-mRL signature for risk stratification, particularly to identify PD-1/CTLA4 inhibitor candidates in high-risk patients; (II) incorporation of the combined m6A-immune-clinicopathological nomogram into diagnostic workflows; (III) prospective validation of the model’s predictive value for immunotherapy outcomes. These advances necessitate updating CRC management guidelines to include m6A-immune biomarkers, while prompting investigation of m6A-targeted therapies for high-risk subgroups.

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third prevailing disease regarding both morbidity and death among malignant diseases in all types of cancers worldwide. There are approximately 1.96 million CRC patients annually, and 0.94 million cases result in death. In particular, the incidence of early-onset CRC has been increasing in recent years, and the increase is closely related to both male sex and increasing age (1). Despite the intensive study of the risk factors, including family history and lifestyle, the intrinsic pathogenesis of CRC is still unclear (2). The continued increased incidence and sustained heavy burden of CRC is a clear trend in China, so expanding the screening scope to control CRC is an important task for China in the future. The number of biomarkers for CRC has been rising in recent years, but most of the identified biomarkers have a low prevalence (3). As a complement, a reliable risk prediction model could be a new screening method for evaluating the stage and prognosis of CRC accurately.

Over 170 RNA modifications have been found so far, encompassing mRNA, tRNA, rRNA, and long non-coding RNA (lncRNA). Among them, N6-methyladenosine (m6A) stands out as the predominant internal chemical alteration in mammalian cells and performs wide duties in the procedure of gene expression and regulation (4,5). The modification known as m6A exerts its effects on mRNA by interacting with several components of the m6A reader and m6A writer complexes. Additionally, there are erasers that seem to have a minor involvement in normal physiological settings (6). The latest study shows that the m6A alteration is also present in non-coding RNAs, encompassing microRNAs, circular RNAs, and lncRNAs (7). Among them, lncRNA plays a vital function in controlling the expression of protein-coding genes and in the development of several disorders, including CRC (8,9). Based on the efforts of researchers, studies on m6A modification and lncRNA in the molecular advances of CRC have also partially borne fruits. For example, Ni et al. discovered a detrimental functional loop involving the lncRNA GAS5-YAP-YTHDF3 axis. They also uncovered a novel mechanism by which GAS5 weakens YAP signaling during the advancement of CRC triggered by m6A, providing another idea for the treatment of CRC (10). In addition, a new study has shown that lncRNA MIR100HG interacts with hnRNPA2B1 in an m6A-dependent way to maintain the accurate expression of TCF7L2 mRNA (11). However, the further underlying mechanisms of lncRNA and m6A modification and its guiding significance in the clinical practice of CRC remain unclear.

Immunotherapy aims to harness the autoimmune system to fight against cancer. Although the prognosis of advanced tumors has been improved as a whole, the therapeutic effect of immunotherapy could be different in diverse subtypes of CRC, which is mainly related to the tumor microenvironment (TME) (12). The TME is an intricate and inclusive system mostly consisting of immune cells, blood vessels, stromal cells, and extracellular matrix (ECM) (13). Previous studies have shown that according to the constructed prognostic model of osteosarcoma based upon expression of m6A and lncRNA, the risk score was negatively linked to the plasma cell level in the TME, which represents a positive factor during cancer therapy (14,15). In addition, Zhang et al. have established the risk score of the m6A-related lncRNA (mRL) prognostic markers that are strongly associated with clinicopathological features, immunological score and immune cell infiltration level in lung squamous cell carcinoma patients, and further verified mRL prognostic markers’ high expression in lung squamous cell carcinoma cell by real-time PCR (16). Although the intrinsic mechanism is unclear, the immunological traits of TME offer many opportunities for the accurate prediction of immunotherapy and prognosis of mRLs in CRC.

According to The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database, we found 11 mRLs-predictive significance in CRC patients and constructed a prognosis model through bioinformatics methods. In addition, depending on the risk score in the predictive model, CRC patients were allocated into two groups: low-risk group (LRG) and high-risk group (HRG). The two groups not only had distinct CRC immune microenvironments but also distinct immune checkpoint associations. We also validated the model well in accordance with the differences of TME, which may provide an effective screening method for accurate prediction of CRC prognosis. We present this article in accordance with the TRIPOD reporting checklist (available at https://jgo.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jgo-2024-878/rc).

Methods

Information acquisition

The transcriptomic data of CRC patients were retrieved from TCGA (https://ocg.cancer.gov/programs/TCGA) database (17). The gene IDs in the TCGA-CRC datasets were cross-referenced with the Ensembl Genome Browser 99 (GRCh38.p13) from GENCODE in order to distinguish between mRNAs and lncRNAs. We also gathered the clinicopathological information of the CRC patients, including gender, age, tumor recurrence, tumor location, residual tumor, tumor stage, neoplasm cancer, tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) stages, and overall survival (OS) data. In our investigation, we ultimately gathered a total of 611 CRC and 51 normal control specimens. This work adhered to the accepted publishing criteria for the TCGA datasets. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments. As a study based on public databases, ethics committee approval or the agreement of the patients who incorporated into this research was not required.

Determination of mRLs in CRC

Herein, we included a total of 611 CRC and 51 normal control specimens. We used the annotation database of the Ensembl Genome Browser 99 (GRCh38.p13) to detect 14,085 lncRNAs and 19,600 mRNAs with the gene symbols in the TCGA dataset. We gathered the 19 m6A-related gene expression from the TCGA mRNA matrix. These genes include writers (METTL3/14, KIA1499, RBM15, WTAP, and ZC3H13), readers (YTHDC1/2, YTHDF1/2/3, HNRNPA2B1, HNRNPC, and IGF2BP1/2/3), and erasers (ALKBH3/5, and FTO). Additionally, we conducted gene coexpression analysis, specifically focusing on lncRNAs associated with m6A methylation regulation genes in TCGA-CRC datasets. The analysis was based on a threshold of |Pearson R| >0.3 and P<0.001. These lncRNAs were classified as mRLs.

Discovery of m6A-related prognostic lncRNAs in CRC

In this study, we applied a univariate Cox regression analysis to discover mRLs that might possibly act as prognostic markers for CRC patients. We concluded that a significant result was obtained with a P value of less than 0.01. Next, we created a correlation graphic according to the data from the univariate Cox analysis. In addition, we generated a heatmap using the “pheatmap” program to illustrate the connection between these lncRNAs’ expression and the clinicopathological characteristics of CRC patients.

Creation of a risk signature using m6A-related prognostic lncRNAs

To develop a risk profile for CRC patients, we used stepwise multivariate Cox regression analysis. This predictive signature was derived from mRLs. The risk scores were computed by adding together the coefficients and products of the RNA expression levels for each patient incorporated in this work. Subsequently, the patients were classified into HRG and LRG using the median risk scores. To assess the risk score classifier’s ability to distinguish and predict prognosis, we conducted a Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and time-dependent ROC analysis. Furthermore, we conducted univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses to validate the independent importance of the risk signature.

Estimation of tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) profile with the m6A-related predictive lncRNAs signature

To determine immune cell infiltration in the three categories, we used the ESTIMATE method. The R script for calculating estimate, immune, and stromal scores was obtained from a website (https://sourceforge.net/projects/estimateproject/). This was done to forecast tumor purity and examine the TME (18). Furthermore, we applied the deconvolution algorithm offered by the TIMER database (https://cistrome.shinyapps.io/timer/) to examine the connection between predictive risk-linked mRLs and the levels of immune cell infiltration involving B cells, CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, macrophages, neutrophils, and dendritic cells (19). Furthermore, we applied the “limma” software to measure the checkpoint members’ expression, encompassing PDCD1, CD274, and cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA4) in various groups.

Creation and assessment of a predictive nomogram

The nomogram study included 611 patients, with the entire cohort considered as the primary group. The validation was conducted with a random sample of 70% of patients from the initial cohort. Cox proportional hazards regression models were implemented to ascertain the connection between pertinent clinical characteristics and mRLs prognostic signature with OS. The selection of variables for multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression models was based on the evaluation of both the Akaike Information Criterion and the concordance index. The chosen factors were then integrated into a nomogram in order to forecast the likelihood of 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS. The predictive performance was ascertained via the use of decision curve analysis (DCA) and calibration curve indicators.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 21.0 and R software (v4.1.3). Differential expression of m6A RNA methylation regulators in CRC versus normal tissues was assessed via Wilcoxon’s rank-sum test. Spearman’s correlation examined relationships between m6A regulators and mRLs, while Kruskal-Wallis tests evaluated their links to clinical parameters. For survival outcomes, Kaplan-Meier curves were generated, with X-tile defining optimal gene expression cutoffs. Prognostic factors were identified through univariate/multivariate Cox regression of clinicopathological variables and molecular signatures.

Results

Landscape of m6A RNA methylation regulators of CRC patients

In this study, the data consisted of 611 CRC, and 51 normal control specimens were acquired from TCGA. After obtaining RNA-seq data of CRC from the TCGA database, the 19 regulators gene expressions involved in m6A RNA methylation were obtained. These regulators consist of 6 m6A writers, namely METTL3/14, KIAA1429, RBM15, WTAP, and ZC3H13. The 10 readers are YTHDF1/2/3, YTHDC1/2, IGF2BP1/2/3, HNRNPC and HNRNPA2B1. There are three erasers: ALKBH3, ALKBH5, and FTO. The m6A RNA methylesterase expression exhibited a differential regulation (Figure 1A). Tumor tissues have elevated METTL3, KIAA1429, RBM15, ZC3H13, YTHDF1/2, YTHDC1, IGF2BP1/2/3, HNRNPA2B1, HNRNPC, and ALKBH3 expression levels compared to normal colon tissues. In contrast, the tumor tissues exhibited a mitigated level of METTL14, YTHDF3, and ALKBH5. Nevertheless, there were no significant disparities in the WTAP, YTHDC2, and FTO expression between the tumor and neighboring normal tissues. More precisely, HNRNPA2B1 showed the highest level of expression in tumors subsequent to HNRNPC and YTHDF1 (P<0.001, Figure 1A). Next, we determined the associations between 19 regulators of m6A RNA methylation. Over 50% of the m6A RNA methylation regulators exhibited positive associations. YTHDC1 and YTHDF3 showed the highest positive association (correlation coefficient =0.47). YTHDC1 was also strongly and positively correlated with METTL14 and ZC3H13, respectively (Figure 1B). At the same time, the negative correlation was mainly concentrated on demethylase ALKBH5 of all the m6A RNA methylation regulators (Figure 1B). The connection between 19 m6A RNA methylation regulators and the CRC patients’ prognosis was ascertained by univariate Cox regression analysis. The forest plots suggest that only IGF2BP3 may be considered a protective factor, whereas the remaining m6A RNA methylases do not show significant associations with the CRC patients’ prognosis (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

The m6A RNA methylation regulator landscape in CRC. (A) Violin plots depicting the differential expression of the 19 m6A RNA methylation regulators in CRC. (B) An analysis of Spearman’s correlation between the 19 m6A RNA modification regulators in CRC (the ‘X’ symbol denotes statistically non-significant correlations). (C) Univariate Cox regression study of the 19 m6A RNA methylation regulators linked to OS. CI, confidence interval; CRC, colorectal cancer; OS, overall survival.

Identification of mRLs in CRC patients

On the basis of the close relationships between m6A RNA methylation regulators and lncRNAs in CRC, we subsequently ascertain the predictive significance of these mRLs. We identified a total of 1924 mRLs in CRC cases. Using Cox regression analysis, we identified 32 mRLs that are linked with CRC prognosis. First, we evaluated associations between 32 mRLs expression and clinicopathological features in CRC through a heat map (Figure 2A). After analyzing the association of 32 mRLs with T, N, and M stages, we manifested that there may be a possible link between m6A-lncRNAs and distant metastasis and survival in CRC (Figure 2A). The connections between these lncRNAs and genes linked to m6A are emerged in Figure 2B. There is a strongest correlation between AC011632.1 and IGF2BP1, while AC069281.2, MIR210HG, and AC010973.2 have a negative correlation with most m6A RNA modification regulators (Figure 2B). We selected a pair of mRL with the strongest correlation in Figure 2B, namely IGF2BP1 and AC011632.1 for the experiment. Their subcellular localizations in 2 of the 3 cases were successfully visualized. While the lncRNA AC011632.1 predominantly localized in the cytoplasm and IGF2BP1 exhibited both nuclear and cytoplasmic expression, their overlapping signals were notably observed in perinuclear regions (Figure S1). Most prognosis-related mRLs were differentially expressed and generally up-regulated in CRC patients (Figure 2C). Among all up-regulated mRLs, MIR210HG showed the highest expression (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

Relationships between m6A RNA regulators and lncRNAs. (A) Heat map illustrating 32 mRLs expression levels in CRC with various clinicopathological features. (B) Heatmap depicting the connection between 32 OS-related m6A-lncRNAs and m6A RNA regulators. The correlation coefficient and P value are present in each cell. (C) Violin plots of 32 mRLs’ differential expression in CRC patients. CRC, colorectal cancer; mRL, m6A-related lncRNA; lncRNA, long non-coding RNA; OS, overall survival; TNM, tumor-node-metastasis.

Verification of the mRL signatures for anticipating OS

We performed least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) Cox analysis using the 32 prognostic mRLs, which led to the discovery of an mRL signature consisting of 11 genes. A patients’ risk score was computed with these gene coefficients. CRC patients were then categorized into LRG and HRG depending on the median risk score. The Kaplan-Meier survival analysis manifested that the LRG had superior clinical outcomes contrasted with the HRG (P=8.876e−10) (Figure 3A). Additionally, the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis displayed that the mRL signature accurately predicts OS (Figure 3B). After accounting for clinicopathological variables encompassing gender, age, tumor, T, N, and M stages in the TCGA data, we applied univariate and multivariate Cox regression studies to assess if the risk scores computed with the mRL signatures accurately forecasted the CRC patients’ prognosis. In the univariate Cox regression analysis, age, risks scores, tumor, T, N, and M stages were significantly associated with the prognosis of CRC patients (Figure 3C). Based on the univariate Cox regression analysis results, multivariate Cox regression analysis revealed that the risk score computed with the mRL signatures was independent risk factors affecting the prognosis of patients with CRC (Figure 3D). In addition, we endeavored to ascertain the potential correlation between the mRL signatures and clinicopathological characteristics. We manifested a significant correlation between greater risk scores and greater fatality rates, as well as more advanced tumor stages. However, we did not notice any correlation with age or gender (Figure 3E).

Figure 3.

Verification of the mRL signatures for anticipating OS. (A) The Kaplan-Meier survival curves illustrate the OS of CRC patients at HRG and LRG, as determined by the mRL signature. (B) The accuracy prediction of OS using the mRL signature is demonstrated by time-dependent ROC curves. (C) Univariate Cox regression analysis identifying the clinicopathological factors linked to OS in CRC patients. (D) Multivariate Cox regression analysis identifying the clinicopathological factors linked to OS in CRC patients. (E) The heatmap displays the correlation analysis findings, illustrating the connection between the mRL signature and the clinicopathological characteristics. **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001. AUC, area under the curve; CI, confidence interval; CRC, colorectal cancer; HRG, high-risk group; LRG, low-risk group; mRL, m6A-related lncRNA; lncRNA, long non-coding RNA; OS, overall survival; ROC, receiver operating characteristic; TNM, tumor-node-metastasis.

Correlation between mRLs and TME

Stromal score, immunoscore, and tumor purity exhibited a significant association between the different risk groups and the mRL signatures. A consolidated method was implemented to execute stromal and immune scores and determine tumor purity. No significant cohort bias clustering was found. At first, we acquired gene expression profiles and clinical data of 11 CRC patients from TCGA. Subsequently, we observed statistically significant variations in stromal, immune scores, and tumor purity in the HRG and LRG. Within the HRG, there was a significant rise in both the immune and stromal scores, although the tumor purity had a significant drop (Figure 4A-4C). The mRLs expression demonstrated a connection with the five immune cell type levels in CRC tissues. The TGF-β dominant subtype based on risk score had the highest correlation with gene expression (Figure 4D). The six immune cells infiltration (B cells, CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, neutrophils, macrophages, and myeloid dendritic cells) in HRG and LRG was determined using TIMER database analysis based on mRL signatures (Figure 4E). The HRG manifested a significant rise in CD4+ T cells, neutrophils, macrophages, and myeloid dendritic cells (all P<0.05). The populations of B cells and CD8+ T cells did not show a significant change (Figure 4E).

Figure 4.

Correlation between mRL and TME. (A) Immune scores between the HRG and LRG groups in CRC patients based on mRL features. (B) Stromal scores between the HRG and LRG groups in CRC patients based on mRL features. (C) Tumor purity between the HRG and LRG groups in CRC patients based on mRL features. (D) The fraction of five immune cell types in the HRG and LRG based on mRL signatures. (E) The correlation between the abundance of six immune cell types in the CRC tissues and the mRL expression. *, P<0.05. CRC, colorectal cancer; HRG, high-risk group; LRG, low-risk group; mRL, m6A-related lncRNA; lncRNA, long non-coding RNA; TME, tumor microenvironment.

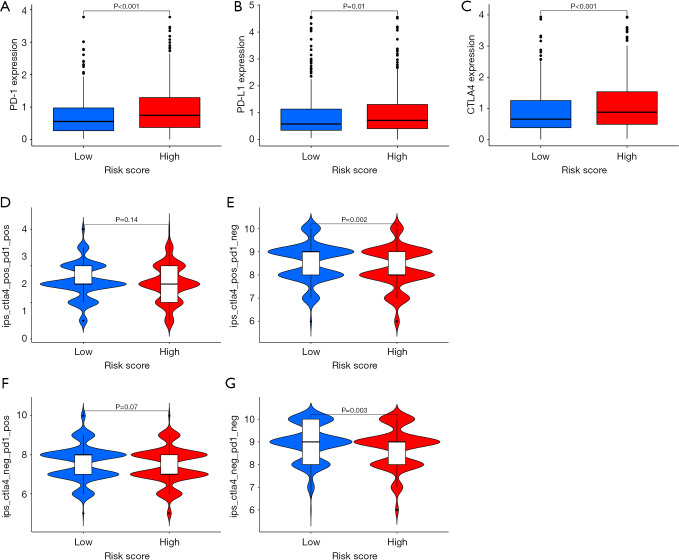

Correlation between mRLs and tumor immune checkpoints

We endeavored to enhance the exploration of the worth of the risk model created using the 11 mRLs in forecasting the immunotherapeutic results of patients. The HRG manifested a significant rise in the expression of programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) (P<0.001), programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) (P=0.01), and CTLA4 (P<0.001) compared to the LRG. This suggests that there is a greater degree of immune escape in the HRG (Figure 5A-5C). Immunophenoscore was a predictor of response to anti-CTLA4 and anti-PD-1 treatments. Specifically, the researchers examined the link between risk and immunophenoscores. The findings indicated that distinct risk groups had varying responses to several CRC medications, including anti-CTLA4 therapy, anti-PD-1 therapy, or a combination of both therapies (Figure 5D-5G). Herein, we clearly suggest that mRLs are very effective in identifying the most suitable CRC patients’ treatment and accurately predicting the outcomes of CRC therapy. Furthermore, we analyzed the proportion of microsatellite instability (MSI) subtypes in the HRG and LRG (Figure S2A). We found no statistically significant difference in risk scores among the different MSI types (Figure S2B). We then reversed the analysis to compare MSI risk scores between the LRG and HRG and found no significant difference either (Figure S2C).

Figure 5.

Correlation between mRL and tumor immune checkpoints. (A-C) The expression patterns of PD-1, PD-L1, and CTLA4 in HRG and LRG. (D-G) The association between various risk groups and immunophenoscores. CTLA4, cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4; HRG, high-risk group; LRG, low-risk group; mRL, m6A-related lncRNA; lncRNA, long non-coding RNA; PD-1, programmed cell death protein 1; PD-L1, programmed death-ligand 1.

Nomogram construction and validation according to the mRL signatures

To enhance the precision of forecasting the OS in CRC patients, we have devised a nomogram that integrates age, T, N, M stages, and risk scores to estimate the probability of 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS (Figure 6A). The calibration plots clearly indicate that the nomogram is more effective in predicting the 3-year OS (Figure 6B). Additionally, our nomogram shows an elevated net advantage across a broader spectrum of threshold probabilities when compared to traditional TNM staging alone for forecasting 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS (Figure 6C). Furthermore, combining mRL signatures with TNM staging improves the net benefit for anticipating a 3-year OS (Figure 6D). Based on the risk score derived from the nomogram, subjects were divided into two groups using the median value. The findings demonstrate that the HRG exhibited significantly worse outcomes contrasted with LRG (P<0.001) (Figure 6E). Time-dependent ROC curves confirm that our nomogram exhibits excellent prognostic accuracy for predicting 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS with AUC values of approximately 0.813, 0.826, and 0.841, respectively (Figure 6F).

Figure 6.

Creation of a predictive model to estimate the OS of CRC patients in the TCGA dataset. (A) Nomogram for anticipating 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS in CRC patients. (B) Comparison between forecasted and found 3-year OS rates using calibration plot. (C) Evaluation of the predictive performance for 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS predictions through DCA. (D) Comparative analysis of nomogram with TNM stage and 11 mRL signatures using DCA. (E,F) Assessment of time-dependent ROC curves and Kaplan-Meier curves for OS prediction in TCGA cohort by the nomogram. AUC, area under the curve; CRC, colorectal cancer; DCA, decision curve analysis; mRL, m6A-related lncRNA; lncRNA, long non-coding RNA; OS, overall survival; ROC, receiver operating characteristic; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; TNM, tumor-node-metastasis.

Discussion

The most common type of internal chemical change that may be observed in eukaryotic mRNAs and lncRNAs is recognized as m6A. A strong association was observed between m6A regulators and lncRNAs, indicating that the target gene expression in CRC patients’ prognosis may be influenced by the interaction between lncRNAs and m6A regulators. In this study, we chose 1,924 mRLs from the TCGA database to investigate their link to the TME, progression, and prognosis of CRC. Initially, a total of 32 mRLs were verified to have a correlation with the CRC stage in patients. Subsequently, based on the expression in CRC and correlation with m6A regulatory factors, 11 mRLs (AP006621.3, GAS1RR, AC090061.1, AL391422.4, AC011120.1, AC009996.1, MIR210HG, ALMS1-IT1, LINC00638, AC010973.2, AC015712.2) were applied to create an mRL signatures model. Through retrieving these 11 mRLs, we found a definitive study has been conducted for MIR210HG, which acts as an oncogenic lncRNA by IGF2BP1 mediated m6A modification in breast cancer (20). Furthermore, as a hub gene pointed by methylated RNA immunoprecipitation sequencing conducted on primary and metastatic prostate cancer samples, MIR210HG has been validated the facilitative role in driving pancreatic cancer progression both in vitro and in vivo (21). Moreover, bioinformatics analysis respectively confirmed that AP006621.3, AL391422.4, ALMS1-IT1, and LINC00638 were linked to the progression and prognosis of different types of tumors and successfully used to construct valid models (22-25). As shown above, there are still few experimental studies on the connection between these mRLs and CRC prognosis. Thus, mRLs may represent a novel prognostic indicator for CRC patients.

Herein, we developed a robust predictive model using mRL signatures to evaluate the OS of CRC patients. Through Kaplan-Meier survival analysis, ROC curve assessment, and univariate as well as multivariate Cox regression analyses, our signatures demonstrated strong predictive ability for assessing OS in this patient population. We concluded that HRG was associated with increased mortality, advanced tumor stage, and lymph node, as well as distant metastasis of CRC. These clinical and pathological characteristics are known determinants of OS and significantly contribute to disease progression in these patients. In addition, we developed a nomogram that combines m6A-related signatures and clinicopathological variables into a single numerical method for forecasting each CRC patient’s prognosis. In particular, our model incorporated TIME and immune checkpoints in addition to the conventional model. Emerging evidence underscores the critical involvement of lncRNAs in orchestrating tumor immune responses through multifaceted regulatory mechanisms (26-28). LncRNAs molecule exert precise control over immune cell functionality by modulating T cell activation states and directing macrophage polarization programs, while simultaneously enabling immune evasion through their governance of checkpoint molecules like PD-L1 (29). Beyond cellular regulation, lncRNAs shape the TME by fine-tuning chemokine networks that dictate immune cell trafficking and by modulating inflammatory cascades through key signaling pathways including NF-κB and STAT3, which collectively determine the cytokine landscape (26,30). This sophisticated regulatory network allows lncRNAs to dynamically influence immune phenotypes, capable of either potentiating antitumor immunity or fostering immunosuppressive niches, thereby critically impacting disease progression and therapeutic efficacy.

As a common occurrence in infiltrated tumors, the TME of CRC encompasses tumor cells, vascular structures, ECM components, fibroblasts, lymphocytes, suppressor cells derived from bone marrow, and signaling molecules (31). Our risk prediction model indicates a significant up-regulation of the number of CD4+ T cells, macrophages, and myeloid dendritic cells in the HRG. The functional involvement of anti-tumor CD4+ T lymphocytes in the TME varies significantly depending on the specific kinds of antigen-presenting cells (APCs). APCs effectively internalize and present tumor antigens on major histocompatibility complex class II molecules at levels that are adequate for T-cell identification (32). The CD4+ T cells are involved in enabling APCs to begin immune responses against tumors. Additionally, they trigger and maintain these responses inside the TME (33). This approach may enhance the ability of CD4+ T lymphocytes to destroy tumor cells indirectly, as shown in a study using a murine model of B cell lymphoma (34). The CD4+ T cells not only stimulate APCs to launch immune responses against tumors but also activate and sustain them inside the TME. A study has proven that Tumor-associated macrophages elevate the proliferation and infiltration of colon cancer cells by activating epithelial-mesenchymal transition remodeling. Co-culturing HT-29 or HCT116 cells with macrophages leads to the activation of the JAK2/STAT3 pathway by IL-6 derived from macrophages, resulting in increased expression of FoxQ1, triggers the production of CCL2 and enhances the recruitment of macrophages, thereby promoting migration and invasion of CRC cells (35). In addition, the TME can release chemokines, cause myeloid dendritic cells to migrate to the tumor site, inhibit immune function, and expedite tumor advancement in line with our initial predictions (36). In this research, the HRG had high immune and stromal scores and low tumor purity. Because the ECM structure of tumor tissue is disorganized compared to normal tissue, fibroblast/myofibroblast infiltration and subsequent accumulation of large collagenous ECM observed in TME destroy tumor purity, and this connective tissue hyperplasia is associated with poor prognosis and treatment resistance (37). Furthermore, the ECM’s shielding diffusion barrier leads to hypoxia, which directly promotes immune evasion by elevating immunomodulatory factors and amplifying angiogenic signals (38).

The potential of the immune system to attack tumor cells is demonstrated by using antibodies to suppress T-cell immune regulatory checkpoints. The listing of antibody drugs targeting immune checkpoint molecules encompassing PD-1, PD-L1, and CTLA4 continues to bring new hope for the treatment of tumor patients. Consistent with the previous study, HRG showed a significant rise in the PD-1/PD-L1 and CTLA4 expressions through our prediction model (39). However, the HRG and LRG have different responses to immunotherapy, which may inform the selection of immunosuppressants.

To summarize, mRLs have a significant impact on the malignant advancement of CRC. Gaining insight into the probable molecular processes of these lncRNAs in CRC is very important for enhancing our comprehension of the molecular biological foundation of CRC onset and progression. Additionally, it aids in identifying novel distinctive biomarkers or treatment targets for CRC patients.

Nevertheless, it is crucial to independently confirm the predictive mRL signatures in other groups of CRC patients. Confirming the identical RNA signature among many datasets is challenging because of variations in microarray chip platforms and inclusion criteria. Therefore, when establishing a signature, careful consideration should be given to the heterogeneity among different datasets, optimization of data processing procedures and algorithms, and improving the predicted accuracy and practical significance of the signature. Moreover, it is important to conduct experimental validation both in vitro and in vivo to authenticate the processes involved in RNAs and their interactions with m6A-related regulators. Our findings provide a foundation for further investigation into understanding the mechanisms involved in the m6A modification of RNAs.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we have identified 11 m6A-immune-related lncRNAs from the TCGA-CRC cohort and created a robust prognostic risk score model. This model demonstrates significant predictive capability for immunotherapy response in CRC patients. Our findings provide crucial perspectives into the functions of m6A-immune-related lncRNAs in CRC tumorigenesis, progression, and the construction of TIME.

Supplementary

The article’s supplementary files as

Acknowledgments

Data generated by The Cancer Genome Atlas, managed by the NCI and NHGRI, is the basis for the publication of this paper.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments.

Footnotes

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the TRIPOD reporting checklist. Available at https://jgo.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jgo-2024-878/rc

Funding: This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. U23A20432, 82203623 and 82302523), the Natural Science Foundation of Hebei (Nos. H2023206290 and H2024206117); Shijiazhuang Municipal Government Funded the Training of Clinical Medical Talents (No. ZF2023031), Clinical Medicine Innovation Research Team of Hebei Medical University (No. 2022LCTD-B2); Hebei Provincial Department of Human Resources and Social Security (Nos. A20240020 and C2024016); Hebei Municipal Government Funded the Training of Clinical Medical Talents (Nos. ZF2025063, ZF2025042 and ZF2025038); Construction Funds of Hebei Key Laboratory of Colorectal Cancer Precision Diagnosis and Treatment from The First Hospital of Hebei Medical University (No. 02-000497).

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://jgo.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jgo-2024-878/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Patel SG, Karlitz JJ, Yen T, et al. The rising tide of early-onset colorectal cancer: a comprehensive review of epidemiology, clinical features, biology, risk factors, prevention, and early detection. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022;7:262-74. 10.1016/S2468-1253(21)00426-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li N, Lu B, Luo C, et al. Incidence, mortality, survival, risk factor and screening of colorectal cancer: A comparison among China, Europe, and northern America. Cancer Lett 2021;522:255-68. 10.1016/j.canlet.2021.09.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sveen A, Kopetz S, Lothe RA. Biomarker-guided therapy for colorectal cancer: strength in complexity. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2020;17:11-32. 10.1038/s41571-019-0241-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wiener D, Schwartz S. The epitranscriptome beyond m(6)A. Nat Rev Genet 2021;22:119-31. 10.1038/s41576-020-00295-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang T, Kong S, Tao M, et al. The potential role of RNA N6-methyladenosine in Cancer progression. Mol Cancer 2020;19:88. 10.1186/s12943-020-01204-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zaccara S, Ries RJ, Jaffrey SR. Reading, writing and erasing mRNA methylation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2019;20:608-24. 10.1038/s41580-019-0168-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yi YC, Chen XY, Zhang J, et al. Novel insights into the interplay between m(6)A modification and noncoding RNAs in cancer. Mol Cancer 2020;19:121. 10.1186/s12943-020-01233-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chi Y, Wang D, Wang J, et al. Long Non-Coding RNA in the Pathogenesis of Cancers. Cells 2019;8:1015. 10.3390/cells8091015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ghafouri-Fard S, Hussen BM, Gharebaghi A, et al. LncRNA signature in colorectal cancer. Pathol Res Pract 2021;222:153432. 10.1016/j.prp.2021.153432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ni W, Yao S, Zhou Y, et al. Long noncoding RNA GAS5 inhibits progression of colorectal cancer by interacting with and triggering YAP phosphorylation and degradation and is negatively regulated by the m(6)A reader YTHDF3. Mol Cancer 2019;18:143. 10.1186/s12943-019-1079-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu H, Li D, Sun L, et al. Interaction of lncRNA MIR100HG with hnRNPA2B1 facilitates m(6)A-dependent stabilization of TCF7L2 mRNA and colorectal cancer progression. Mol Cancer 2022;21:74. 10.1186/s12943-022-01555-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kasprzak A. The Role of Tumor Microenvironment Cells in Colorectal Cancer (CRC) Cachexia. Int J Mol Sci 2021;22:1565. 10.3390/ijms22041565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderson NM, Simon MC. The tumor microenvironment. Curr Biol 2020;30:R921-5. 10.1016/j.cub.2020.06.081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu Z, Zhang X, Chen D, et al. N6-Methyladenosine-Related LncRNAs Are Potential Remodeling Indicators in the Tumor Microenvironment and Prognostic Markers in Osteosarcoma. Front Immunol 2021;12:806189. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.806189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weiner AB, Vidotto T, Liu Y, et al. Plasma cells are enriched in localized prostate cancer in Black men and are associated with improved outcomes. Nat Commun 2021;12:935. 10.1038/s41467-021-21245-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang W, Zhang Q, Xie Z, et al. N (6) -Methyladenosine-Related Long Non-Coding RNAs Are Identified as a Potential Prognostic Biomarker for Lung Squamous Cell Carcinoma and Validated by Real-Time PCR. Front Genet 2022;13:839957. 10.3389/fgene.2022.839957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network ; Weinstein JN, Collisson EA, et al. The Cancer Genome Atlas Pan-Cancer analysis project. Nat Genet 2013;45:1113-20. 10.1038/ng.2764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Newman AM, Liu CL, Green MR, et al. Robust enumeration of cell subsets from tissue expression profiles. Nat Methods 2015;12:453-7. 10.1038/nmeth.3337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li T, Fan J, Wang B, et al. TIMER: A Web Server for Comprehensive Analysis of Tumor-Infiltrating Immune Cells. Cancer Res 2017;77:e108-10. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-0307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shi W, Tang Y, Lu J, et al. MIR210HG promotes breast cancer progression by IGF2BP1 mediated m6A modification. Cell Biosci 2022;12:38. 10.1186/s13578-022-00772-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liang Y, Yin W, Cai Z, et al. N6-methyladenosine modified lncRNAs signature for stratification of biochemical recurrence in prostate cancer. Hum Genet 2024;143:857-74. 10.1007/s00439-023-02603-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luo Y, Xie Y, Wu D, et al. AL360181.1 promotes proliferation and invasion in colon cancer and is one of ten m6A-related lncRNAs that predict overall survival. PeerJ 2023;11:e16123. 10.7717/peerj.16123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou SZ, Pan YL, Deng QC, et al. A Prognostic Signature for Colon Adenocarcinoma Patients Based on m6A-Related lncRNAs. J Oncol 2023;2023:7797710. 10.1155/2023/7797710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jin LP, Sun YW, Liu T, et al. Screening of m6A gene-related lncRNAs in colon adenocarcinoma and construction of a prognostic prediction model. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2023;27:10462-71. 10.26355/eurrev_202311_34321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang T, Bai J, Zhang Y, et al. N(6)-Methyladenosine regulator RBM15B acts as an independent prognostic biomarker and its clinical significance in uveal melanoma. Front Immunol 2022;13:918522. 10.3389/fimmu.2022.918522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hu Y, Li Y, Xiong H, et al. Exosomal SLC16A1-AS1-induced M2 macrophages polarization facilitates hepatocellular carcinoma progression. Int J Biol Sci 2024;20:4341-63. 10.7150/ijbs.94440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu X, Li Z, Tong J, et al. Characterization of the Expressions and m6A Methylation Modification Patterns of mRNAs and lncRNAs in a Spinal Cord Injury Rat Model. Mol Neurobiol 2025;62:806-18. 10.1007/s12035-024-04297-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang M, Su Y, Wen P, et al. Subtype cluster analysis unveiled the correlation between m6A- and cuproptosis-related lncRNAs and the prognosis, immune microenvironment, and treatment sensitivity of esophageal cancer. Front Immunol 2025;16:1539630. 10.3389/fimmu.2025.1539630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xi Q, Yang G, He X, et al. M(6)A-mediated upregulation of lncRNA TUG1 in liver cancer cells regulates the antitumor response of CD8(+) T cells and phagocytosis of macrophages. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2024;11:e2400695. 10.1002/advs.202400695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang F, Wen J, Liu J, et al. Demethylase FTO mediates m6A modification of ENST00000619282 to promote apoptosis escape in rheumatoid arthritis and the intervention effect of Xinfeng Capsule. Front Immunol 2025;16:1556764. 10.3389/fimmu.2025.1556764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li J, Wu C, Hu H, et al. Remodeling of the immune and stromal cell compartment by PD-1 blockade in mismatch repair-deficient colorectal cancer. Cancer Cell 2023;41:1152-1169.e7. 10.1016/j.ccell.2023.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haabeth OAW, Fauskanger M, Manzke M, et al. CD4(+) T-cell-Mediated Rejection of MHC Class II-Positive Tumor Cells Is Dependent on Antigen Secretion and Indirect Presentation on Host APCs. Cancer Res 2018;78:4573-85. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-2426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Isser A, Silver AB, Pruitt HC, et al. Nanoparticle-based modulation of CD4(+) T cell effector and helper functions enhances adoptive immunotherapy. Nat Commun 2022;13:6086. 10.1038/s41467-022-33597-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paget C, Chow MT, Duret H, et al. Role of γδ T cells in α-galactosylceramide-mediated immunity. J Immunol 2012;188:3928-39. 10.4049/jimmunol.1103582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wei C, Yang C, Wang S, et al. Crosstalk between cancer cells and tumor associated macrophages is required for mesenchymal circulating tumor cell-mediated colorectal cancer metastasis. Mol Cancer 2019;18:64. 10.1186/s12943-019-0976-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Garris CS, Luke JJ. Dendritic Cells, the T-cell-inflamed Tumor Microenvironment, and Immunotherapy Treatment Response. Clin Cancer Res 2020;26:3901-7. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-1321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.De Martino D, Bravo-Cordero JJ. Collagens in Cancer: Structural Regulators and Guardians of Cancer Progression. Cancer Res 2023;83:1386-92. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-22-2034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yuan Z, Li Y, Zhang S, et al. Extracellular matrix remodeling in tumor progression and immune escape: from mechanisms to treatments. Mol Cancer 2023;22:48. 10.1186/s12943-023-01744-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kalbasi A, Ribas A. Tumour-intrinsic resistance to immune checkpoint blockade. Nat Rev Immunol 2020;20:25-39. 10.1038/s41577-019-0218-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]