Abstract

Anti-N-methyl-ᴅ-aspartate (anti-NMDA) receptor encephalitis is a well-known autoimmune encephalitis caused by antibodies against the GluN1 subunit of the anti-NMDA receptor (anti-NMDAR). Stroke, characterized by abrupt focal neurological deficits due to ischemic or hemorrhagic vascular insults, is rarely preceded by anti-NMDAR encephalitis. Here, we described a case of a 69-year-old female without any prior comorbidities who presented with acute stroke and left hemiparesis with a history of recent onset of neuropsychiatric symptoms. Her cerebrospinal fluid was positive for anti-NMDAR antibody, and significant improvement was noticed after the initiation of immunotherapy. In this patient, stroke occurred following anti-NMDAR encephalitis; however, the pathophysiological link between the two remains unclear. This case presents an interesting and rare clinical intersection between stroke and anti-NMDAR encephalitis, highlighting the difficulty of neurological diagnosis. Due to the unusual association of such pathological conditions, this case contributes to the broader understanding of potential connections between stroke and autoimmune encephalitis, emphasizing the need for a multidisciplinary approach to diagnosis and management.

Keywords: Anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor encephalitis, Autoimmune encephalitis, Central nervous system, Stroke

Introduction

Anti-N-methyl-ᴅ-aspartate (anti-NMDA) encephalitis is a prominent form of autoimmune encephalitis, typically linked to antibodies targeting the GluN1 subunit of the NMDA receptor (NMDAR). The disease predominantly affects young adults, with a propensity for women. Diagnosis is often challenging due to its complex clinical presentation and varying symptoms, which can mimic psychiatric disorders [1,2]. The hallmark presentation of anti-NMDAR encephalitis includes subacute onset of neuropsychiatric symptoms such as agitation, confusion, hallucinations, memory deficits, and behavioral changes. Seizures, movement disorders, and autonomic dysfunction may also develop as the disease progresses [2,3]. One of the notable associations with anti-NMDAR encephalitis is the presence of ovarian teratomas in women. This highlights the potential paraneoplastic nature of the disorder, where an immune response against tumor antigens mistakenly targets neuronal tissues [2,3]. Infections, particularly herpes simplex and varicella-zoster virus, are recognized triggers for postinfectious anti-NMDAR encephalitis. The proposed mechanisms linking these infections and cancer to autoimmune encephalitis include molecular mimicry, where antigens from the disease or tumor closely resemble neural antigens, leading to an autoimmune response, and bystander activation, where immune activation in response to infection inadvertently damages neural tissue [4,5]. This condition requires timely diagnosis and management, usually involving immunosuppressive therapies such as corticosteroids, intravenous immunoglobulin, or plasmapheresis as a first-line therapy, and tumor resection might be needed if a neoplasm is present. Early treatment improves outcomes, while delays can lead to prolonged illness and persistent neurological impairments [1-5]. In contrast, stroke is characterized by a sudden onset of focal neurological deficit due to vascular injury to the central nervous system, either by ischemia (infarction) or hemorrhage. The most common type of stroke is ischemic stroke (85% of cases), which is typically caused by small vessel arteriolosclerosis, large artery atherothromboembolism, cardio-embolism, and arterial dissection [6-8]. Here, we present a case of anti-NMDAR encephalitis preceding stroke. This case presents an interesting and rare clinical intersection between stroke and encephalitis, highlighting the complexity of neurological diagnosis when patients exhibit coinciding symptoms.

Case Report

A 69-year-old female without any prior comorbidity or addiction was admitted to the Department of Neurology, Institute of Medical Sciences, Banaras Hindu University in Varanasi, India, with the chief complaint of left-sided hemiparesis for 3 days. Three days prior, she had no symptoms; she had eaten dinner the night before and slept through the night. The next morning when she woke, she noticed weakness in her left limbs, and family members observed the same. This event was associated with slurring of speech without any tonic-clonic movement, head trauma, altered sensorium, fever, headache, vomiting, or incontinence. Weakness was maximal at the onset and remained static for the next 3 days. Upon examination, the patient was conscious and oriented, with a Glasgow Coma Scale of 15 (E4M6V5). Her general physical examination was unremarkable, with a blood pressure of 132/84 mmHg and a normal pulse rate of 82 beats/min. On further assessment, there was mild left lower facial palsy, and motor power was reduced on the left side (upper limb power MRC [Medical Research Council] grade 3 and lower limb grade 2). Hypotonia was observed in the left upper and lower limbs, and the Babinski sign was positive on the same side. No signs of sensory impairment, cerebellar dysfunction, or meningeal irritation were found, and her NIHSS (National Institute of Health Stroke Scale) on admission was 9. Twenty-four-hour Holter monitoring was performed for detection of any paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, which is a significant risk factor due to its association with cardioembolic stroke. No abnormality was observed (Supplementary Figure 1). Considering the diagnosis of left hemiparesis possibly due to vascular etiology, a thorough workup was performed, including brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI, Figure 1) with magnetic resonance angiography (Tables 1–3). MRI suggested an acute right anterior cerebral artery infarction with a normal angiogram. Initial treatment was started with antiplatelet, statin, and other supportive therapies. During admission, she developed a delirious state. On further questioning, family members reported that she had been acting strangely over the past month, including babbling, muttering, talking excessively, and sleeping less. She also experienced visual hallucinations in the form of relatives who were not present or who had died. Occasionally, she did recognize family members and called them by their incorrect names. However, there was no history of fever, seizure, new-onset movement disorder, or any other systemic or constitutional symptoms.

Figure 1. Brain magnetic resonance imaging and angiography showing an acute infarct and temporal lobe abnormalities.

(A) T1-weighted, (B) T2-weighted, and (C) fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) images of axial sections at the level of the midbrain; images show asymmetric ill-defined areas of T1 hypo-intensities and T2/FLAIR hyperintensities involving the medial temporal lobes. Left temporal lobe atrophy is seen as dilatation of the temporal horn of the ipsilateral lateral ventricle. (D) Diffusion-weighted image and (E) corresponding apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) images at the upper level of the lateral ventricles demonstrate restricted diffusion involving the right paramedian frontoparietal lobe with low signal on the corresponding ADC map, consistent with acute right anterior cerebral artery infarct. (F) Time-of-flight brain magnetic resonance angiography does not demonstrate any notable abnormality.

Table 1.

Blood investigations of the patient

| Component | Results |

|---|---|

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 10.4 |

| WBC (×103/µL) | 13.9 |

| Neutrophil (%) | 71.4 |

| Lymphocyte (%) | 16.8 |

| Mean corpuscular volume (fL) | 81.4 |

| Platelet count (×103/µL) | 306 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.69 |

| Urea (mg/dL) | 124.2 |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 123.3 |

| Potassium (mmol/L) | 3.4 |

| AST (IU/L) | 35 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 31 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.52 |

| Direct bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.35 |

| Total protein (g/dL) | 5.0 |

| Serum Albumin (g/dL) | 2.7 |

| ALP (IU/L) | 236 |

| Random blood sugar (mg/dL) | 96 |

| Phosphate (mg/dL) | 5.18 |

| Calcium (mg/dL) | 8.65 |

| ESR (mm/hr) | 18 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 42.88 |

| Rheumatoid factor (IU/mL) | 22.43 |

| PT (sec)/INR | 16.3/1.22 |

| Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 176 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 127 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 66 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 102 |

| VLDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 25.4 |

WBC, white blood cell; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; CRP, C-reactive protein; PT, prothrombin time; INR, international normalized ratio; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; VLDL, very low-density lipoprotein.

Table 2.

Viral markers and other infection panels

| Test | Result |

|---|---|

| HIV 1 and 2 | Negative |

| HBsAg, anti-HCV | Negative |

| Malaria para check | Negative |

| IgM Dengue, NS1 antigen | Negative |

| IgM Typhi DOT (Salmonella Typhi IgM test), Scrub, Leptospira | Negative |

| VDRL | Negative |

HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; HCV, hepatitis C virus; IgM, immunoglobulin M; NS1, non-structural protein 1; DOT, dot enzyme immunoassay; VDRL, venereal disease research laboratory.

Table 3.

Imaging-based and other relevant investigations

| Investigation | Result |

|---|---|

| Chest X-ray (anteroposterior view) | Normal |

| Ultrasonography abdomen | Normal |

| Electrocardiogram | Normal sinus rhythm |

| Two-dimensional echocardiography | No resting regional wall motion abnormality, normal LV function, grade I diastolic dysfunction |

| Renal Doppler | Normal |

| Vasculitis panel (ANA, ANCA) | Negative |

| Electroencephalogram | Normal |

| Urine routine examination | Within normal limits |

| Serum anti-TPO (IU/mL) | 16 |

| Serum ACE level (IU/L) | 18 |

| Serum ammonia (μg/dL) | 42 |

| CECT thorax, abdomen, and pelvis | Normal |

LV, left ventricle; ANA, antinuclear antibodies; ANCA, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies; TPO, thyroid peroxidase; ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; CECT, contrast-enhanced computed tomography.

Considering her acute neuropsychiatric symptoms, possibilities of metabolic, infectious, or immune-mediated encephalitis were considered. Based on those, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis, video electroencephalogram (EEG), vasculitis panel, autoimmune and paraneoplastic encephalitis panel, serum ammonia, angiotensin-converting enzyme, and anti-thyroid peroxidase level were tested (Table 2–4). Her CSF anti-NMDAR antibody was positive, confirming NMDAR encephalitis (Table 5). The indirect immunofluorescence method was used to determine the presence of anti-NMDAR antibodies in the CSF. The presence of the GluN1 (NR1) subunit was tested, as it is associated with stroke-related autoimmunity. Immunotherapy was started with methylprednisolone pulse therapy followed by oral prednisolone, and she experienced a large improvement in her symptoms. This suggests that early recognition and treatment of such encephalitis, even in atypical presentations like stroke, can lead to favorable outcomes. During follow-up, we added azathioprine as a steroid-sparing immunotherapy, and oral prednisolone was gradually tapered and stopped.

Table 4.

Cerebrospinal fluid analysis

| Parameter | Result |

|---|---|

| Cell count (cells/mm3) | 3 |

| Neutrophil (%) | 0 / 100 |

| Lymphocyte (%) | |

| Protein (mg/dL) | 33.67 |

| Sugar (mg/dL) | 68 |

| Corresponding blood sugar (mg/dL) | 96 |

| Pan neurotropic viral panel | Negative |

| Autoimmune and paraneoplastic encephalitis panel | Anti-NMDAR positive |

| OCB, cytology, CBNAAT, Gram stain and culture/sensitivity, cryptococcal antigen | Negative |

OCB, oligoclonal bands; CBNAAT, cartridge-based nucleic acid amplification test; NMDAR, N-methyl-ᴅ-aspartate receptor.

Table 5.

Cerebrospinal fluid autoimmune encephalitis profile

| Antibodies against | Results |

|---|---|

| Glutamate receptor, N-methyl-ᴅ-aspartate | Positive |

| Glutamate receptor, α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid 1 | Negative |

| Glutamate receptor, α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid 2 | Negative |

| Contactin-associated protein 2 | Negative |

| Leucine-rich glioma-inactivated protein 1 | Negative |

| Gamma aminobutyric acid B1, B2 | Negative |

This type of autoimmune encephalitis can cause a range of neuropsychiatric and neurological symptoms. In this case, it is presented alongside acute ischemic stroke, which is a rare association with poorly understood causality.

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient in the presence of his family members. Ethical approval was not required, as per the guidelines of our institution, for single case reports not involving experimental intervention or identifiable personal data.

Discussion

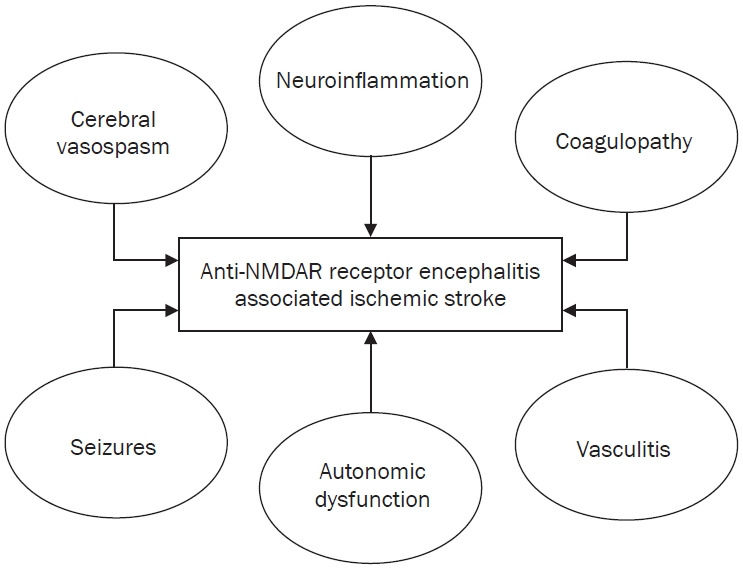

Anti-NMDAR encephalitis and its co-occurrence with stroke, as seen in this presented case, is rare, and the exact pathophysiological connection remains unclear. In anti-NMDAR encephalitis, ischemic stroke-like events such as neuroinflammation, coagulopathy, vasculitis, autonomic dysfunction, seizures, and cerebral vasospasm can occur due to various factors related to the disease pathophysiology (Figure 2). These factors can interact in a complex manner in the setting of anti-NMDAR encephalitis, increasing the risk of ischemic events [9,10]. While stroke may result in secondary neuropsychiatric manifestations, the presence of anti-NMDAR antibodies suggests that autoimmune encephalitis is the primary triggering factor of cognitive and behavioral changes [11,12]. The diagnosis of anti-NMDAR encephalitis in this case raises several important points. While this autoimmune encephalitis typically affects younger individuals, it can also present in older patients as neuropsychiatric symptoms, such as confusion, hallucinations, memory deficits, and abnormal behavior [13,14].

Figure 2. Representation of the interplay of inflammation, vascular dysfunction, autonomic instability, and seizures in anti-N-methyl-ᴅ-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) encephalitis, which creates a prothrombotic and ischemic environment that increases the risk of stroke.

Anti-NMDAR encephalitis is increasingly encountered in clinical care. The diagnosis is confirmed with positive antibody testing, preferably in the CSF, and is supported by abnormal EEG and inflammatory CSF profile [15]. However, as in our case, 20%–40% of cases can have normal EEG. In autoimmune encephalitis, EEG is an essential tool, primarily for excluding subclinical seizures and prognosis, and a normal EEG correlates with good outcomes independent of other prognostic factors. Our patient who presented with subacute neuropsychiatric symptoms followed by an acute stroke event had normal awake and drowsy EEG and demonstrated good outcomes after treatment [16,17].

Detection of immunoglobulin G antibodies against the GluN1 subunit of the NMDAR is generally considered a highly specific test for anti-NMDAR encephalitis, although there have been rare reports of false positives. In a retrospective case series, 4 of 40 anti-NMDAR antibody-positive cases were false positive. Thus, although antibody testing is a crucial diagnostic tool, positive results should be interpreted with care if the clinical and paraclinical data do not align with the well-established NMDAR encephalitis phenotype [16]. In our case, the preceding history of acute-onset neuropsychiatric symptoms and significant improvement with immunotherapy suggests underlying autoimmune encephalitis, reducing the likelihood of a false positive anti-NMDAR antibody result.

In the literature, there are only a few descriptions of NMDAR encephalitis presenting as stroke-like episodes (SLEs). In a retrospective case series of 24 children with NMDAR encephalitis, six patients presented with hemiparesis or SLEs. Four of them experienced seizures, and all had normal MRI findings. In another case series of 29 patients, only one reported hemiplegia with aphasia [17,18]. However, our case is unique as the patient was an older female with MRI showing an acute infarct in a specific vascular territory (Figure 1). The sequential relationship between stroke and encephalitis raises interesting questions about potential shared mechanisms, such as immune-mediated causes, infectious causes (bacterial, viral, fungi, and parasites), and postischemic inflammation [19-21]. Stroke typically results from a vascular event, while anti-NMDAR encephalitis is immune-mediated, affecting synaptic transmission and frequently associated with tumors like ovarian teratomas. However, no clear tumor or paraneoplastic syndrome was identified in this case. There are a few potential hypotheses for the coexistence of these two conditions: poststroke neuroinflammation and shared mechanisms of vascular and immune pathways [2,3,6,7].

In conclusion, NMDAR encephalitis associated with stroke may be underreported, and this case highlights the need for clinicians to consider autoimmune encephalitis in patients with unexplained neuropsychiatric symptoms, even in the setting of a stroke. Due to the unusual relationship of such pathological conditions, this case report contributes to the broader understanding of potential connections between stroke and autoimmune encephalitis, emphasizing the need for a multidisciplinary approach to diagnosis and management.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Mitra A, Srivastava NK; Data curation: Mishra VN; Investigation, Supervision: Pathak A; Writing–original draft: Mitra A, Srivastava NK; Writing–review and editing: Vivek A, Mishra VN, Pathak A

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1 can be found via https://doi.org/10.47936/encephalitis.2025.00017.

MRA images in the sagittal plane

References

- 1.Stavrou M, Yeo JM, Slater AD, Koch O, Irani S, Foley P. Case report: meningitis as a presenting feature of anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis. BMC Infect Dis. 2020;20:21. doi: 10.1186/s12879-020-4761-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhong R, Chen X, Liao F, et al. FLAMES overlaying anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor encephalitis: a case report and literature review. BMC Neurol. 2024;24:140. doi: 10.1186/s12883-024-03617-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rong X, Xiong Z, Cao B, Chen J, Li M, Li Z. Case report of anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor encephalitis in a middle-aged woman with a long history of major depressive disorder. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17:320. doi: 10.1186/s12888-017-1477-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guarino M, La Bella S, Santoro M, et al. The Leading role of brain and abdominal radiological features in the work-up of anti-NMDAR encephalitis in children: an up-to-date review. Brain Sci. 2023;13:662. doi: 10.3390/brainsci13040662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ioannidis P, Papadopoulos G, Koufou E, Parissis D, Karacostas D. Anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis possibly triggered by measles virus. Acta Neurol Belg. 2015;115:801–802. doi: 10.1007/s13760-015-0468-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Potter TB, Tannous J, Vahidy FS. A contemporary review of epidemiology, risk factors, etiology, and outcomes of premature stroke. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2022;24:939–948. doi: 10.1007/s11883-022-01067-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Esenwa C, Gutierrez J. Secondary stroke prevention: challenges and solutions. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2015;11:437–450. doi: 10.2147/VHRM.S63791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Knight-Greenfield A, Nario JJ, Gupta A. Causes of acute stroke: a patterned approach. Radiol Clin North Am. 2019;57:1093–1108. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2019.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.GBD 2019 Stroke Collaborators Global, regional, and national burden of stroke and its risk factors, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Neurol. 2021;20:795–820. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(21)00252-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guzik A, Bushnell C. Stroke epidemiology and risk factor management. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2017;23(1, Cerebrovascular Disease):15–39. doi: 10.1212/con.0000000000000416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang S, Xu M, Liu ZJ, Feng J, Ma Y. Neuropsychiatric issues after stroke: clinical significance and therapeutic implications. World J Psychiatry. 2020;10:125–138. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v10.i6.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang Q, Xie Y, Hu Z, Tang X. Anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor encephalitis: a review of pathogenic mechanisms, treatment, prognosis. Brain Res. 2020;1727:146549. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2019.146549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alam AM, Easton A, Nicholson TR, et al. Encephalitis: diagnosis, management and recent advances in the field of encephalitides. Postgrad Med J. 2023;99:815–825. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2022-141812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shichita T, Sakaguchi R, Suzuki M, Yoshimura A. Post-ischemic inflammation in the brain. Front Immunol. 2012;3:132. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu CY, Zhu J, Zheng XY, Ma C, Wang X. Anti-N-Methyl-D-aspartate receptor encephalitis: a severe, potentially reversible autoimmune encephalitis. Mediators Inflamm. 2017;2017:6361479. doi: 10.1155/2017/6361479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ardakani R, Vernino S, Blackburn K. False positive cerebrospinal fluid NMDA receptor antibodies: a single center case series. Neurology. 2022;99(23_Supplement_2):S54–S55. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000903440.65833.71. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gowda VK, Vignesh S, Natarajan B, Shivappa SK. Anti-NMDAR encephalitis presenting as stroke-like episodes in children: a case series from a tertiary care referral centre from southern India. J Pediatr Neurosci. 2021;16:194–198. doi: 10.4103/jpn.jpn_80_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chandra SR, Padmanabha H, Koti N, Kalya Vyasaraj K, Mailankody P, Pai AR. N-methyl-D-aspartate encephalitis our experience with diagnostic dilemmas, clinical features, and outcome. J Pediatr Neurosci. 2018;13:423–428. doi: 10.4103/jpn.jpn_96_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berkowitz AL. Approach to neurologic infections. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2021;27:818–835. doi: 10.1212/con.0000000000000984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gole S, Anand A. StatPearls Publishing; Autoimmune encephalitis [updated 2023 Jan 2]. In: StatPearls [Internet] 2025 Jan [cited 2025 Feb 1]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK578203/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nguyen L, Wang C. Anti-NMDA receptor autoimmune encephalitis: diagnosis and management strategies. Int J Gen Med. 2023;16:7–21. doi: 10.2147/ijgm.s397429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

MRA images in the sagittal plane