Abstract

Direct conversion of amines to corresponding alcohols is challenging even under harsh reaction conditions. Inspired by enzymatic transamination, we present a transamination borrowing-hydrogen strategy that enables the direct and selective Mn-catalyzed deaminative hydroxylation of benzylamines, affording a broad scope (>30 examples) of alcohols in good yields at low catalyst loadings (down to 0.05 mol%). Notably, methanol serves a dual role as hydrogen donor and amino acceptor, rather than a conventional role as a methylating agent. Mechanistic investigations reveal base plays a pivotal role in facilitating the 1,3-proton transfer process, thereby effectively suppressing N-methylation pathways and favoring alcohol formation.

Subject terms: Synthetic chemistry methodology, Homogeneous catalysis

Direct conversion of amines to corresponding alcohols is challenging even under harsh reaction conditions. Inspired by enzymatic transamination, the authors present a transamination borrowing-hydrogen strategy that enables the direct deaminative hydroxylation of benzylamines via manganese catalysis.

Introduction

The interconversion of hydroxyl and amino groups plays a crucial role in both metabolic processes and organic synthesis, rendering them indispensable constituents in various fields, including biology and chemistry1–4. The transformation of alcohols into amines has been well-established2–8, particularly with recent advancements in the direct amination of alcohols using ammonia8,9. In contrast, the deaminative hydroxylation of amines continues to be a significant challenge10. Direct nucleophilic attack by hydroxyl groups requires harsh reaction conditions due to the poor leaving ability of amino groups7,11–14. To address this issue, strategies such as converting the amino group into more active diazonium ion15, pyridinium ion16, isodiazene17, or other better leaving groups have been well explored (Fig. 1a)18. However, these activating stepwise methods often rely on stoichiometric excess toxic reagents, leading to significant waste generation and necessitating extra pre-activation steps.

Fig. 1. Representative strategies for converting amines to alcohols.

a Conventional approach of transforming amines to alcohols via direct or indirect substitution. b Deaminative hydroxylation of amines through borrowing hydrogen process. c Enzyme-catalyzed conversion of amino acids to hydroxyl acids via stepwise transamination and reduction. d This work: Bio-inspired transamination borrowing-hydrogen strategy.

Borrowing hydrogen represents a robust and efficient strategy for the construction of C-N bonds2,3,19. By employing this approach, it is also feasible to cleave the C-N bond of primary amines simply using water (Fig. 1b). However, the competitive dehydrogenation between reactant amines (a) and product alcohols (b), as well as the crucial imine intermediates (int-a) being attacked by amines (a) instead of hydrolysis to yield carbonyl compounds (int-b) reduces the selectivity of this reaction (Fig. 1b). To the best of our knowledge, there are only two reports with limited examples on this topic. In addition to the use of noble metal catalysts such as Ru10 and Ir20, either high-pressure H2 (5 bar) or excess glycerol as an external hydrogen source is required to enhance the selectivity towards alcohols. Nevertheless, low yields along with other side products are generally observed.

Transamination is a vital pathway for metabolism in vivo, wherein transaminases facilitate the transfer of amino groups between amino acids and ketoacids21. Recently, inspired by this crucial biocatalytic processes, biomimetic transamination has emerged as a valuable approach for the introduction of amino groups into carbonyl compounds22, enabling the synthesis of diverse amino acids23, peptides24, amines25, and other compounds featuring amino functional groups22. Conversely, only a few examples have aimed at eliminating amino groups to generate carbonyl groups, without further hydrogenation of the carbonyl groups to hydroxyl groups26. Combining transamination and reduction may facilitate the direct conversion of an amino group to a hydroxyl group, however, these two transformations require amino receptors and additional hydrogen source, respectively (Fig. 1c)27.

In line with our recent research interests in the catalytic dehydrogenative coupling of alcohols28–32 and inspired by transamination process in nature33, we conceive that alcohols can serve as both hydrogen donors and amino acceptors. Specifically, we utilize methanol, which is conventionally utilized as a methylating reagent for the reductive amination34–39, as a bifunctional reagent for accomplishing deaminative hydroxylation of amines (Fig. 1d). Herein, we employ earth-abundant Mn catalysts and apply methanol as both a hydrogen donor and an amino acceptor, thereby accomplishing the deaminative hydroxylation of benzyl amines through the transamination borrowing-hydrogen process. This strategy demonstrates nearly quantitative chemo-selectivity and excellent yields for the desired alcohols with an impressive turnover frequency (TOF) of up to 14280 h−1.

Results

Optimization of reaction conditions

Initially, the reaction conditions were screened based on our preceding work on the Mn-catalyzed mono-N-methylation of aliphatic amines34. Conducting the reaction with 3 mmol of benzylamine (1a), 1.2 equiv. Cs2CO3, and 0.1 mol% Mn-I in MeOH at 140 °C for 18 h in a 15 mL sealed tube yielded the targeted benzyl alcohol (1b) in 77% yield (for more details, see Supplementary Information, Tables S1–S5), along with N-methylbenzylamine (1c) byproduct at 13%, arising from side N-methylation34. Exploration of other inorganic bases indicated that strong bases tend to produce significantly more alcohol 1b and less N-methylated amine 1c compared to weak bases (Table S1, entries 1–6). This disparity likely results from the enhanced facilitation of 1,3-proton migration induced by the stronger base40. Moreover, it is critical to highlight that increased catalyst loadings could hasten the hydrogenation of the imine intermediates (int-1c and int-1d), culminating in formation of the N-methylbenzylamine (1c) byproduct. Utilizing CsOH‧H2O as the base enhanced the benzyl alcohol (1b) yield to 87%, with the byproduct 1c reduced to 6% (Table S1, entry 6). Extending the reaction time to 24 h notably boosted the yield of 1b to 94% (Table S3, entry 5). Reducing catalyst loading to 0.05 mol% at a 6 mmol scale effectively curtailed the formation of 1c, albeit potentially exceeding the pressure threshold of the sealed tube. For safety concern, a preferable reaction scale is 3 mmol with 0.1 mol% Mn-I.

Exploration of substrate scope

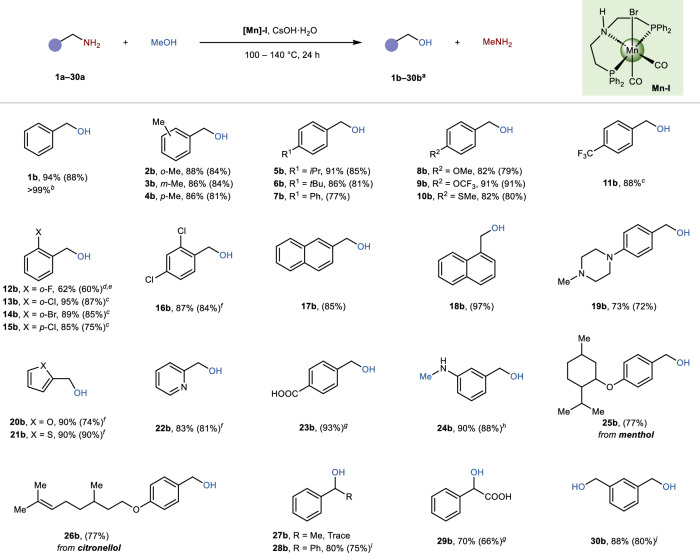

With the optimal reaction conditions in hand, the scope of benzylamines was initially investigated (Fig. 2). The position of the methyl substituents on the phenyl ring had a minimal impact on the transformation, producing ortho-, meta-, and para-methylphenyl methanol in high yields (2b–4b, 86–88% yields). Both electron-donating and electron-withdrawing groups are well compatible to the protocol, resulting in good to excellent yields (5b–16b, 62–91%). Specifically, the presence of a strong electron-withdrawing group (-CF3, 11b) necessitated a milder reaction temperature (120 °C), possible due to increased acidity of the H atoms at the benzyl position, which could facilitate a possible 1,3-proton transfer process40. Halogen substituents were also tolerated to gain the corresponding alcohols in moderate to excellent yields (62–95%, 12b–16b). The relatively low yield observed for 2-fluorobenzyl alcohol (12b, 62%) can be attributed to the formation of a defluorinated methoxy-substituted byproduct (8%). The protocol was also well suited for sterically hindered naphthalene methylamines, resulting in yields of 97% and 85% for 17b and 18b, respectively. Heterocyclic substrates also demonstrated good compatibility, affording alcohols 19b–22b in 83%–90% yields. Subsequently, we explored the protocol tolerance towards sensitive functional groups. Unprotected carboxylic group and double bond were well retained, giving the products 23b and 26b in good isolated yields (77%–93%).

Fig. 2. Substrate scope.

aReaction carried out with Mn-I complex (0.1 mol %), amines (3 mmol), and CsOH·H2O (1.2 equiv.) in methanol (10 equiv.) under N2 atmosphere at 140 °C for 24 h. Yields were determined by 1H NMR analysis by using mesitylene as an internal standard. Isolated yields are given in parentheses. bAmine (6 mmol) and Mn-I (0.05 mol%). cAt 120 °C. dAt 100 °C. e48 h. fAt 110 °C. gWith 2.5 equiv. KOH. h3h. iAmines (5 mmol) and Mn-I (0.05 mol%). jAmine (1 mmol), Mn-I (0.3 mol%), CsOH·H2O (3.6 equiv.), and methanol (30 equiv.). kAmine (1.5 mmol).

In the case of substrate containing both aromatic amine and alkyl amine moieties, besides deaminative hydroxylation, primary aromatic amino group underwent simultaneously mono-N-methylation, leading to the formation of (3-(methylamino)phenyl)methanol in an excellent yield (24b, 90%). This observation further demonstrates the selectivity and generality of the protocol. Pleasingly, the protocol could also be applied to the synthesis of natural derivatives, affording the alcohols 25b–26b in good yields (77%). The optimized conditions were found to be incompatible with 1-phenylethylamine resulting in the production of trace amounts of 1-phenethylalcohol (27b), likely attributed to potential self-coupling or cross-coupling reactions32,37,41. Other α-secondary amines performed well, with diphenylmethanol (28b) and 2-hydroxy-2-phenylacetic acid (29b) achieving yields of 80% and 70%, respectively. The protocol also enabled the synthesis of the diol (30b), with a good yield of 88%. Non-benzylic amines, as illustrated by alkyl substrate 37a (Fig. S9), demonstrated a distinct tendency to form N-methylamine derivatives. This observation can be mechanistically rationalized by the lack of an aromatic ring system, which appears to hamper the possible 1,3-proton transfer process.

Owing to its significant advantages, including rapid heating, precise control and short reaction times, microwave irradiation has found widespread applications in diverse metal- and organo-catalyzed organic synthesis42–44. Under microwave irradiation, the model reaction with 6 mmol of benzylamine and 0.05 mol% of Mn-I was proceed smoothly at 160 °C (Fig. 3a). An impressive turnover frequency of up to 14280 h−1 could be achieved within 5 min, while extending to 15 min, quantitative yield could be achieved, demonstrating its significant acceleration compared to conventional oil bath heating.

Fig. 3. Synthetic application.

a Microwave-assisted deaminative hydroxylation of benzyl amines. b Diversified transformation of alcohol products. c Synthesis of Fesoterodine.

To demonstrate the utility of the protocol, product transformations and corresponding synthesis of bioactive molecules were carried out. Benzyl alcohols are readily subjected to oxidation or esterification processes, resulting in the production of aldehydes, carboxylic acids, and ester products, which are easily further converted to obtain Butenafine, Aniracetam, and Racecadotril (Fig. 3b). Moreover, Butenafine can also be obtained via borrowing hydrogen coupling reaction twice (Fig. 3b)45,46. The deaminative hydroxylation protocol can be readily employed for the synthesis of drug intermediate 31b in an isolated yield of 55%, which can subsequently undergo a simple transformation to produce Fesoterodine, a mAChR antagonist (Fig. 3c). This outcome demonstrates the potential application of this innovative approach in the synthesis of pharmaceutically important compounds.

Mechanistic studies

To comprehend the mechanisms underlying the remarkable preference for the formation of alcohols other than normal amines or imines, a series of control experiments were conducted. Firstly, the reaction profile of the model reaction between benzylamine (1a) and methanol was plotted under the optimized reaction conditions (Fig. 4a). The crucial intermediate N-methyl-1-phenylmethanimine (int-1d) was detected as expected, which clearly indicates the occurrence of pivotal 1,3-proton transfer process17,19 in the reaction. The absence of N-benzylmethanimine (int-1c) may be attributed to its rapid rearrangement into int-1d. Additionally, the N-benzyl-1-phenylmethanimine (int-1e) was also observed, which could potentially arise from the side condensation between benzylamine (1a) and benzaldehyde (int-1b).

Fig. 4. Mechanistic investigations.

a Reaction profile of the transformation of benzylamine to benzyl alcohol under standard conditions. b Control experiments: (i) without catalyst Mn-I, or replacing methanol with tert-amyl alcohol (t-AmOH) or H2O; (ii) replacing methanol with n-BuOH; (iii) deuteration experiments. c Additional control experiments: (i) monitor of the reaction of benzylamine 1a with paraformaldehyde without the presence of catalyst Mn-I; (ii) transformation of benzylamine 1a in the presence of active Mn-II species without base; (iii) transformation of int-1c in the presence of active Mn-II species without base. d Proposed mechanism for the Mn-Catalyzed deaminative hydroxylation of benzyl amines.

Secondly, in the absence of the Mn-I catalyst, no product 1b formation was detected (Fig. 4b–i), thereby excluding the possible substitution of amino group by hydroxyl group directly5–8. When t-amyl alcohol or H2O was employed as a solvent instead of MeOH, no 1b was formed either. These observations may indicate a different plausible mechanism other than that illustrated in Fig. 1a, b. Considering that MeNH2 is gaseous and difficult to be isolated at ambient conditions, n-BuOH was utilized instead of methanol under the otherwise identical conditions (Fig. 4b–ii). As expected, n-BuNH2 could be detected in the reaction mixture (59% NMR yield) and isolated as tert-butyl butylcarbamate (Figs. S13 and S14). This observation confirmed the direct exchange between amino and hydroxyl groups process, suggesting the plausible transamination pathway was involved. To understand the role of methanol, a systematic deuteration study was conducted by replacing methanol with deuterated CD3OD (Fig. 4b–iii and Table S7). The formation of deuterated product 1b-d2 with 84% deuteration ratio at the benzylic position suggested methanol served as a hydrogen donor in the catalytic cycle. Through slight optimization of reaction parameters (Table S7), the deuteration ratio was enhanced to 90%, establishing this protocol as a robust strategy for preparing deuterated fine chemicals.

Subsequently, several experiments were carried out to elucidate the pivotal factors driving the transamination (Fig. 4c), specifically the roles of Mn-I and base. When benzylamine 1a was reacted with formaldehyde without catalyst (Fig. 4c–i), species int-1d was identified as the major component in the reaction mixture along with the formation of benzyl alcohol (14%, 1b) and int-1e (10%), highlighting the essential role of a base in facilitating the 1,3-proton transfer. In view of Mn-II is the possible active catalyst species in the N-methylation of benzylamine47,48, it was synthesized and directly used in the deaminative hydroxylation of benzylamine under standard conditions without base participation (Fig. 4c–ii). Trace amounts of benzyl alcohol (1b) was detected under base-free conditions. Additionally, in the absence of a base, N-benzylmethanimine (int-1c) failed to undergo conversion into N-methyl-1-phenylmethanimine (Fig. 4c–iii). Combining these observations, we confirmed that base was crucial for the 1,3-proton transfer other than Mn catalysts. By using int-1c, int-1d, and int-1e as the substrates instead of 1a under the optimal reaction conditions, all produced desired 1b in moderate to excellent yields (91%, 97%, and 62% respectively), further confirming they are true intermediates in the transformation. However, the conversion of N-methylbenzylamine (1c) to 1b was impeded under the standard reaction conditions, potentially attributed to the challenging formation of an iminium species from 1c and formaldehyde49 (for more details, see Supplementary Information, Section 9.2).

Based on aforementioned observation and literature2,21,22, we propose a plausible mechanism involving a transamination borrowing-hydrogen process (Fig. 4d). Firstly, methanol undergoes dehydrogenation catalyzed by Mn-I to generate formaldehyde (amino acceptor) and H2 (hydrogen source)50–52. The amine (a) further reacts with formaldehyde and undergoes dehydration to form an imine intermediate (int-c)53. Subsequently, with the assistance of a base, a 1,3-proton transfer occurs as the pivotal step in the transamination to generate the key intermediate int-d23,25,54,55. Imine (int-d) is ready for hydrolysis, leading to the formation of a carbonyl species (int-b). Finally, after hydrogenation catalyzed by the catalyst, int-b is successfully converted into desired alcohol (b)56,57. N-methyl-1-phenylmethanimine (int-e) may also be detected as an intermediate. However, if N-methylbenzylamine (c) is produced through conventional N-methylation pathway, benzyl alcohol (b) is hardly accessible.

Discussion

In summary, inspired by biomimetic transamination, we have accomplished the direct and selective deaminative hydroxylation of benzylamines to their corresponding alcohols using a transamination borrowing-hydrogen strategy. This achievement was realized with the aid of a pincer Mn-catalyst and a base. Unlike the traditional use of methanol as a methylating agent in well-established N-methylation reactions, in this case, methanol functions both as a hydrogen donor and amino acceptor. Beyond the broad substrate scope and good compatibility with various functional groups, including halogens, heterocycles, and carboxyl groups, we have demonstrated excellent selectivity towards alcohols at low catalyst loadings (0.05 mol%), achieving up to 14280 h−1 turnover frequency (TOF). Comprehensive mechanistic studies highlight the key role of bases in the transamination process, where strong bases facilitated the 1,3-proton transfer in imine intermediates, leading to the production of alcohols, rather than the conventional N-methylated products.

Methods

Materials

Unless otherwise noted, all reactions were carried out in a nitrogen-filled glove box. All commercial reagents were used directly without further purification, unless otherwise stated. MeOH was dried over magnesium and distilled under a N2 atmosphere. All reaction sealed tubes (15 mL) were purchased from Beijing Synthware Glass. CDCl3 and DMSO-d6 was purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories.

General procedures for the deaminative hydroxylation of amines

To a sealed tube (15 mL) equipped with a stir bar, Mn-I catalyst (1.9 mg, 0.1 mol%), CsOH·H2O (604.5 mg, 3.6 mmol), benzylamine derivatives (3 mmol), and methanol (30 mmol, 1.2 mL) were added in sequence under nitrogen atmosphere. The solution was heated in a pre-heated oil bath at 140 °C for 24 h (attention: during reaction, pressure develops, a high-pressure resistant sealed tube is recommended). After cooling to room temperature, mesitylene (60 mg, 0.5 mmol) was added as an internal standard and sent for NMR measurement. The residue was purified by column chromatography to afford the desired product.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22271060, T.T.), School of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering at Ningxia University, and Department of Chemistry at Fudan University.

Author contributions

J.J. performed the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the original draft. S.W., Y.H., Z.D., and L.W. performed some experiments. Q.Z. analyzed the data and revised the manuscript. T.T. designed the project, supervised J.J. in conducting this research, and revised the manuscript. All the authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Liqun Jin, and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

All data are available in the main text or the Supplementary Information. The experimental procedures and characterization of all new compounds are provided in the Supplementary Information. Data supporting the findings of this manuscript are also available from the corresponding author upon request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Qingshu Zheng, Email: qszheng@fudan.edu.cn.

Tao Tu, Email: taotu@fudan.edu.cn.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-025-61989-3.

References

- 1.Reed, J. H. & Seebeck, F. P. Reagent engineering for group transfer biocatalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.63, e202311159 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Irrgang, T. & Kempe, R. 3d-metal catalyzed N- and C-alkylation reactions via Borrowing hydrogen or hydrogen autotransfer. Chem. Rev.119, 2524–2549 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang, Q., Wang, Q. & Yu, Z. Substitution of alcohols by N-nucleophiles via transition metal-catalyzed dehydrogenation. Chem. Soc. Rev.44, 2305–2329 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pelckmans, T. R. M., Van de Vyver, S. & Sels, B. F. Bio-based amines through sustainable heterogeneous catalysis. Green. Chem.19, 5303–5331 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mutti, F. G., Knaus, T., Scrutton, N. S., Breuer, M. & Turner, N. J. Conversion of alcohols to enantiopure amines through dual-enzyme hydrogen-borrowing cascades. Science349, 1525–1529 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morandi, B., Legnani, L. & Bhawal, B. Recent developments in the direct synthesis of unprotected primary amines. Synthesis49, 776–789 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kanbara, Y., Abe, T., Fushimi, N. & Ikeno, T. Base-catalyzed direct transformation of benzylamines into benzyl alcohols. Synlett23, 706–710 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bähn, S. et al. The catalytic amination of alcohols. ChemCatChem3, 1853–1864 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang, M., Qi, Z., Xie, M. & Qu, Y. Employing ammonia for the synthesis of primary amines: recent achievements over heterogeneous catalysts. ChemSusChem18, e202401550 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khusnutdinova, J. R., Ben-David, Y. & Milstein, D. Direct deamination of primary amines by water to produce alcohols. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.52, 6269–6272 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu, L. et al. Hydrothermal water enabling one-pot transformation of amines to alcohols via supported Pd catalysts. React. Chem. Eng.7, 839–843 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abdur Rahman, S. M. et al. Efficient one-step conversion of primary aliphatic amines into primary alcohols: application to a model study for the total synthesis of (±)-Scopadulin. Org. Lett.2, 2893–2895 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abdur Rahman, S. M. et al. Total synthesis of (±)-Scopadulin. J. Org. Chem.66, 4831–4840 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abdur Rahman, S. M., Ohno, H. & Tanaka, T. Improved method of an unusual conversion of aliphatic amines into alcohols. Tetrahedron Lett.42, 8007–8010 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stuhr-Hansen, N., Padrah, S. & Strømgaard, K. Facile synthesis of α-hydroxy carboxylic acids from the corresponding α-amino acids. Tetrahedron Lett.55, 4149–4151 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghiazza, C. et al. Bio-Inspired deaminative hydroxylation of aminoheterocycles and electron-deficient anilines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.62, e202212219 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dherange, B. D. et al. Direct deaminative functionalization. J. Am. Chem. Soc.145, 17–24 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berger, K. J. & Levin, M. D. Reframing primary alkyl amines as aliphatic building blocks. Org. Biomol. Chem.19, 11–36 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reed-Berendt, B. G., Latham, D. E., Dambatta, M. B. & Morrill, L. C. Borrowing hydrogen for organic synthesis. ACS Cent. Sci.7, 570–585 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheong, Y. J. et al. Ir(bis-NHC)-catalyzed direct conversion of amines to alcohols in aqueous glycerol. Eur. J. Org. Chem.2019, 1940–1946 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xiao, X. & Zhao, B. Vitamin B6-based biomimetic asymmetric catalysis. Acc. Chem. Res.56, 1097–1117 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xie, Y., Pan, H., Liu, M., Xiao, X. & Shi, Y. Progress in asymmetric biomimetic transamination of carbonyl compounds. Chem. Soc. Rev.44, 1740–1748 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu, Y. E. et al. Enzyme-inspired axially chiral pyridoxamines armed with a cooperative lateral amine chain for enantioselective biomimetic transamination. J. Am. Chem. Soc.138, 10730–10733 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cai, W. et al. Asymmetric biomimetic transamination of α-keto amides to peptides. Nat. Commun.12, 5174–5182 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cai, W. et al. Transamination of aromatic aldehydes to primary arylmethylamines. Org. Lett.25, 3876–3880 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou, Y., Wu, S. & Bornscheuer, U. T. Recent advances in (chemo)enzymatic cascades for upgrading bio-based resources. Chem. Commun.57, 10661–10674 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Contente, M. L. & Paradisi, F. Self-sustaining closed-loop multienzyme-mediated conversion of amines into alcohols in continuous reactions. Nat. Catal.1, 452–459 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu, J. et al. Iridium-catalyzed selective cross-coupling of ethylene glycol and methanol to lactic acid. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.59, 10421–10425 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lu, Z. et al. NHC-Iridium-catalyzed deoxygenative coupling of primary alcohols producing alkanes directly: synergistic hydrogenation with sodium formate generated in situ. ACS Catal.11, 10796–10802 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zeng, G. et al. Selective modular synthesis of ortho-substituted phenols via Pd-catalyzed dehydrogenation–coupling–aromatization of alcohols. ACS Catal.13, 6222–6229 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zeng, G. et al. Modular access to quaternary α-hydroxyl acetates by catalytic cross-coupling of alcohols. ACS Catal.13, 2061–2068 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang, S. et al. Selective control of secondary alcohols upgrading using Ir-catalyzed cross-coupling strategy. Sci. China Chem.67, 914–921 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mathew, S., Renn, D. & Rueping, M. Advances in one-pot chiral amine synthesis enabled by amine transaminase cascades: pushing the boundaries of complexity. ACS Catal.13, 5584–5598 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ji, J. et al. Manganese-catalyzed mono-N-methylation of aliphatic primary amines without the requirement of external high-hydrogen pressure. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.63, e202318763 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sun, F. et al. Borrowing hydrogen β-phosphinomethylation of alcohols using methanol as C1 source by pincer manganese complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc.145, 25545–25552 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sivakumar, G. et al. Multi-functionality of methanol in sustainable catalysis: beyond methanol economy. ACS Catal.13, 15013–15053 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lu, Z. et al. Highly efficient NHC-iridium-catalyzed β-methylation of alcohols with methanol at low catalyst loadings. Sci. China Chem.64, 1361–1367 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang, J. et al. Selective mono-N-methylation of nitroarenes with methanol catalyzed by atomically dispersed NHC-Ir solid assemblies. J. Catal.389, 337–344 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bruneau-Voisine, A. et al. Manganese catalyzed α-methylation of ketones with methanol as a C1 source. Chem. Commun.55, 314–317 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Casasnovas, R. et al. C–H activation in pyridoxal-5′-phosphate and pyridoxamine-5′-phosphate Schiff bases: effect of metal chelation. A computational study. J. Phys. Chem. B117, 2339–2347 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang, K. et al. Asymmetric Guerbet reaction to access chiral alcohols. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.59, 11408–11415 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baig, R. B. N. & Varma, R. S. Alternative energy input: mechanochemical, microwave and ultrasound-assisted organic synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev.41, 1559–1584 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Polshettiwar, V. & Varma, R. S. Microwave-assisted organic synthesis and transformations using benign reaction media. Acc. Chem. Res.41, 629–639 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Larhed, M., Moberg, C. & Hallberg, A. Microwave-accelerated homogeneous catalysis in organic chemistry. Acc. Chem. Res.35, 717–727 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sawama, Y. et al. Palladium on carbon-catalyzed aqueous transformation of primary alcohols to carboxylic acids based on dehydrogenation under mildly reduced pressure. Adv. Synth. Catal.357, 1205–1210 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vadakkekara, R. et al. Visible-light-induced efficient selective oxidation of nonactivated alcohols over {001}-Faceted TiO2 with molecular oxygen. Chem. Asian J.11, 3084–3089 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang, Y. et al. Unmasking the ligand effect in manganese-catalyzed hydrogenation: mechanistic insight and catalytic application. J. Am. Chem. Soc.141, 17337–17349 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang, Y. et al. Structure, reactivity and catalytic properties of manganese-hydride amidate complexes. Nat. Chem.14, 1233–1241 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Choi, G. & Hong, S. H. Selective monomethylation of amines with methanol as the C1 source. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.57, 6166–6170 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen, Z. et al. Methanol as hydrogen source: transfer hydrogenation of aldehydes near room temperature. Asian J. Org. Chem.9, 1174–1178 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Aboo, A. H. et al. Methanol as hydrogen source: transfer hydrogenation of aromatic aldehydes with a rhodacycle. Chem. Commun.54, 11805–11808 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Subaramanian, M. et al. General and selective homogeneous Ru-catalyzed transfer hydrogenation, deuteration, and methylation of functional compounds using methanol. J. Catal.425, 386–405 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ng, X. Q. et al. Direct access to chiral aliphatic amines by catalytic enantioconvergent redox-neutral amination of alcohols. Nat. Synth.2, 572–580 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Molleti, N. et al. Base-catalyzed [1,n]‑proton shifts in conjugated polyenyl alcohols and ethers. ACS Catal.9, 9134–9139 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang, K. et al. Asymmetric hydrogenation of racemic allylic alcohols via an isomerization–dynamic kinetic resolution cascade. J. Org. Chem.87, 3804–3809 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Widegren, M. B. et al. A highly active manganese catalyst for enantioselective ketone and ester hydrogenation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.56, 5825–5828 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang, L. et al. Lutidine-based chiral pincer manganese catalysts for enantioselective hydrogenation of ketones. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.58, 4973–4977 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data are available in the main text or the Supplementary Information. The experimental procedures and characterization of all new compounds are provided in the Supplementary Information. Data supporting the findings of this manuscript are also available from the corresponding author upon request.