Abstract

Dairy foods have been shown to improve BMD, a measure of bone quantity, yet there is little understanding of their influence on measures of bone quality. The aim of this study was to examine associations of dairy intakes with two measures of bone quality: bone material strength index (BMSi) and spinal trabecular bone score (TBS), and the potential mediating role of inflammation, among adults from the Boston Puerto Rican Osteoporosis Study. This cross-sectional analysis included dietary intake assessed with a culturally tailored food frequency questionnaire. Dairy food groups were calculated as total dairy (milk, yogurt, and cheese), milk, cheese, yogurt, desserts, non-fat, and fat-containing dairy. Bone material strength index (n = 138) was measured using micro indentation with the Osteoprobe, and TBS (n = 412) was calculated from DXA scans. Multivariable linear regression estimated the association of dairy food intakes with each bone measure. Mediation analysis evaluated direct and indirect (via inflammatory cytokines) associations between dairy intake and BMSi and TBS. Participants were 77.4% female with mean age 70.5 ± 6.9 yr. Higher intakes of total dairy (β = 1.79, p = .04) and milk (β = 1.74, p = .06) were associated with BMSi. Higher intake of fat-containing dairy (β = .018, p = .04) was positively associated with TBS, while higher intake of non-fat dairy (β = −.042, p = .02) was inversely associated with TBS. Inflammatory cytokines were not identified as mediators of these associations. Dairy food intakes were associated with measures of bone quality; however, the foods that predicted BMSi and TBS differed. Bone material strength index was influenced by total dairy and milk, while TBS was influenced by dairy fat content. Future studies should examine the impact of dairy matrix components on immune and inflammatory pathways.

Keywords: osteoporosis, bone microarchitecture, bone material composition, dairy, dairy matrix, inflammation

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

Introduction

Osteoporosis (OP) is a major public health concern among Puerto Rican adults. Data from the Boston Puerto Rican Osteoporosis Study (BPROS) show a higher or similar prevalence of OP among Puerto Rican adults living in the greater Boston area, compared with US non-Hispanic White (NHW) and Mexican American adults.1 While data are not available exclusively for Puerto Rican adults, a recent meta-analysis reported that people of Hispanic origin experience the second highest rate of fragility fractures in the United States compared with NHW individuals.2 This represents a tremendous economic and health burden as Puerto Ricans are the second largest mainland US Hispanic group, and people of Hispanic origin comprise the second largest racial or ethnic group in the United States.3 Investigation into potential preventive measures of OP in Puerto Rican adults is urgently needed.

Assessment of bone health by BMD, a measure of bone quantity, accounts for only 60% of the variation in bone fragility, due to its inability to capture differences in material composition and structure, referred to collectively as measures of bone quality.4 Bone material strength index (BMSi) and spinal trabecular bone score (TBS) are low-cost indicators of bone quality in tibial cortical (hard outer layer) and vertebral trabecular (spongy, inner bone), respectively. Bone material strength index, assessed by impact microindentation, is a direct measure of material compositional strength and has been shown to predict fracture risk independently of BMD. Trabecular bone score, an imaging technology that captures microarchitectural data from DXA scans of vertebrae, has been shown to predict fracture risk independently of FRAX and BMD.5,6 To better capture true variation in bone fragility, all measures of bone health, both for quantity and quality, must be included in bone assessment research.

Extensive research has confirmed the impact of nutrition on BMD, with a focus on key nutrients (eg, calcium, vitamin D, phosphorus, potassium, and protein) and food groups, including dairy products.7,8 Findings from a recent meta-analysis including 7 studies of varying populations (differing sex, age groups, and geographical areas including Mexico, Korea, and China) suggested that consuming a “milk/dairy” dietary pattern was associated with the greatest reduction in risk of low BMD (OR: 0.59, 95% CI, 0.50-0.68, p < .0001).9 In adults from the BPROS, higher intakes of dairy (milk, yogurt, and cheese) and milk were associated with higher BMD in participants with sufficient vitamin D status, yet no assessment with measures of bone mechanical properties has been made in this cohort.10 Data from the Framingham Osteoporosis Study showed no cross-sectional association of dairy products with measures of bone mechanical properties except for cheese intake with cortical BMD in older women.11 However, bone composition was assessed via HR-pQCT, a geometric model of bone material strength, not an actual measure of strength. Further, the Framingham Osteoporosis Study represents primarily older adults of NHW ethnicity, and the culturally distinct dairy intake of Puerto Rican adults must be considered, to best represent this group.12

The influence of dairy products on bone health may occur, in part, via the immune system. Antioxidant peptides in milk have been shown to increase BMD and bone strength in an animal model via disruption of the bone destructive actions of ROS.13 Other research has reported that dairy products such as aged cheese and yogurt can exert beneficial health effects by improving the ratio of healthful, compared to unhealthful, intestinal microorganisms.14 These findings suggest that individual dairy foods may be pro- or anti-inflammatory and that unique dairy patterns may have differing downstream health effects due to their chemical composition. The objectives of this cross-sectional study were to (1) examine the association of dairy foods with BMSi and TBS, two assessments of bone quality, and (2) investigate the role of inflammatory cytokines as mediators of these associations in Puerto Rican adults from the BPROS. We hypothesized that higher intake of dairy foods would be associated with higher BMSi and TBS, and that the relation would be mediated by a reduction in biomarkers of inflammation.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

The current study presents a cross-sectional analysis of eligible participants from the Boston Puerto Rican Health Study (BPRHS) (Figure 1) to determine whether cumulative dietary intakes (average of up to three intake measures from 2004 to 2022) predict bone quality (2019-2022). Participants with information on diet from two or more waves of the two studies (BPRHS baseline, wave 2, wave 4, and BPROS follow-up) were included for analysis. Exclusion of invalid FFQ data due to extreme energy intake <600 or >4800 kcal/d (n = 143) resulted in 1478 participants with valid dietary data (Figure 1). Then, participants from the follow-up examination to the original BPROS (BPROS wave 2) with information on TBS (n = 426) or BMSi (n = 165) and applicable covariates were included in this study (Figure S1). A total of 21 participants’ LS (L2-L4) and 11 BMSi measures were excluded from analyses, as determined by the study endocrinologist (BDH) who reviewed all DXA scans with T-scores >4.0 to check for nonanatomic parts or extra skeletal calcification and all BMSi. A total of 25 participants’ BMSi measures were excluded. Of these participants, 3 had values >3 SD above the mean (138.2, 124.0, and 107.8); 21 had either no measurement or an invalid measurement, usually because of soft tissue thickness; 1 experienced an acute episode of high blood pressure. Women were determined to be postmenopausal based on the age range of the sample (56-90 yr) and date of last menses. Participants who elected to participate in the measurement of BMSi were more likely to be male, had higher intake of total energy, consumed alcohol more frequently, were less likely to smoke, less likely to self-report diabetes, hypertension or OP, but more likely to use OP meds, and had lower average TBS (Table S1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the analytic sample for the current study chosen from eligible participants from the Boston Puerto Rican Health Study (BPRHS) and the Boston Puerto Rican Osteoporosis Study (BPROS wave 2). Eligible participants for the current study included measures of bone material strength index (BMSi) and trabecular bone score (TBS). The pattern of missing covariate data is shown in Figure S1.

Exposure—dairy groups

Dietary intake was assessed using a semi-quantitative FFQ designed and validated for use in this population.10 FFQ data were collected at all BPRHS and BPROS visits. Nutrient intake was calculated using Nutrition Data System for Research software (Nutrition Coordinating Center, University of Minnesota) and determined as the mean across three study visits (always including baseline and wave 2 BRPHS visits) with the third data point from either the BPROS wave 2 or BPRHS wave 4 assessments (the measurement closest to the bone outcome measures was chosen for each participant). We created energy adjusted (per 2000 kcal) USDA servings for every dairy food. Next, we categorized dairy foods with nutrient similarity into the following subgroups: total dairy (sum of milk, yogurt, and cheese), milk (all percentages of fat), cheese, yogurt, and dairy-specific desserts [eg, pudding, custard (flan), cheesecake, ice cream]. Dairy products are especially high in calcium, protein, and phosphorous; however, the content of these nutrients varies across subgroups. For example, cheese tends to be higher in calcium and protein compared to milk, which tends to be higher in phosphorous compared to cheese, and yogurt tends to be higher in all three nutrients compared to milk and cheese. Dairy groups were created to be reflective of these differences. Additionally, there is evidence to suggest that consumption of quality dairy dessert products may impart health benefits; therefore, this group was included in the analysis.15 Due to the association of select sources of saturated fat with inflammation and with low BMD, dairy groups were also created based on fat content: fat-containing dairy (sum of all dairy products with ≥1% fat content) and non-fat dairy (sum of all dairy products with <1% fat content).16 Tertile categories of dairy food groups were created to compare bone outcomes across “low,” “medium,” and “high” levels of intake.

Measurements and assessments

Bone material strength index by impact microindentation (OsteoProbe, ActiveLife Scientific). Bone material strength index, a measure of bone material composition, is an index of resistance of cortical bone to a 375 μm wide microindentation created by the Osteoprobe device. As the probe indents the surface of the tibia, it induces a microfracture. The more easily this occurs, the deeper the probe indents the bone, recording a higher indentation distance into the bone and a lower BMSi, reflecting poor bone microarchitecture. The measures were obtained following previously described procedures.17 The computer recording the measures automatically reported the BMSi, defined as 100 times the ratio of the mean indentation distance in polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) to the mean indentation distance obtained from the participant. Measurement of the PMMA reference distance between each participant allowed for correction of variation in probe tips.18 The precision of BMSi was reported to be 1.7%–3.2%.19

Trabecular bone score is a measure of trabecular microarchitecture. It is a gray-level texture measurement extracted from anterior-posterior LS DXA images using iNsight software. The model of DXA scanner used to measure TBS was changed during the study; iNsight software used on the Lunar (Lunar Model Prodigy scanner; General Electric) scanner was version 2.1.2.0 and for the Horizon (Hologic) scanner was 2.1. Reported precision of the TBS measurement is between 1.5% and 1.9%.20 Previously published methods were followed to convert data obtained from the Hologic scanner to Lunar equivalents. Briefly, linear regression models were used to derive cross calibration equations for each measure on the 2 scanners; TBS measures obtained on the Horizon scanner were regressed on TBS measures obtained on the Lunar scanner. The International Society of Clinical Densitometry’s (ISCD’s) Advanced Precision Calculation Tool was used to calculate precision as the group root-mean-square SD average coefficient of variation.21 Calibration equations used in the current study are shown in Table S2.

Covariates were measured at either the BPROS wave 2 or BPRHS wave 4 visits except for serum 25OHD, which was measured at the baseline examinations of the BPRHS and BPROS. Demographic and lifestyle characteristics were based on self-report and captured by bilingual, trained interviewers. Important covariates included age (yr), biological sex, BMI (kg/m2), physical activity score, current smoker (yes, no), frequency of alcohol intake (none/light, moderate, heavy within the past year), diagnosis of diabetes (yes, no), plasma PTH concentration (pg/mL), serum pentosidine concentration (ng/mL), and serum 25OHD concentration (ng/mL). PTH and pentosidine were tested in the models as potential confounders of the primary association. In preclinical work, PTH has been shown to increase cortical bone mass and mechanical strength and in human research recombinant PTH increased cortical thickness.22,23 Pentosidine is an advanced glycation end product that increases in cortical bone concentration with age and is associated with a decrease in post yield energy dissipation, a measure that is related to damage density in this compartment of bone.24 Therefore, we accounted for these two biomarkers in this study. Height was measured using a SECA 214 portable stadiometer and weight was measured using a Toledo Weight Plate, model I5S clinical scale (Bay State and Systems, Inc.). These measurements were used to calculate BMI. Individuals were classified as having diabetes if their fasted blood glucose was ≥126 mg/dL or they self-reported use of diabetes medication. Physical activity was assessed with a modification of the Framingham physical activity index, representing the sum of usual daily activity including hours spent sleeping, and performing sedentary, light, moderate, or heavy activities weighted for oxygen consumed during each activity.25

PTH (pg/mL) was measured in plasma by Abcam ELISA kit (Waltham, MA), with intra-assay and inter-assay CVs ≤1.5% and ≤3.8%, respectively. Pentosidine concentration was measured in serum with a double-Ab sandwich ELISA kit procedure from Antibody Research Corporation (St. Charles, MO 63304), with intra-assay CV < 10% and inter-assay CV < 12%. Serum 25OHD concentration was assessed as the mean of values from fasted blood samples collected at the baseline examinations of the BPRHS and BPROS. This measure was made by extraction followed by RIA with a 25I radioimmunoassay Packard COBRA II Gamma Counter (catalog no. 68100E; DiaSorin, Inc.) with intra-assay and inter-assay CVs of 10.8% and 9.4%, respectively. IL-6 and TNFα were measured in plasma by Invitrogen ELISA (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Intra-assay and inter-assay CVs for IL-6 were 6.2% and 7.9%, respectively; CVs for TNFα were 4.4% and 7.5%, respectively. IL1-β was measured in plasma by Abcam ELISA with intra-assay and inter-assay CVs of 4.8% and 5.6%, respectively. High sensitivity C-reactive protein (CRP) was measured in serum with the EasyRA Clinical Chemistry analyzer (Medica Corporation) and had a CV range of 1.35%–2.33%.

Statistical analysis

Means ± SD for continuous variables and proportions of participants for categorical variables were calculated. Normality was determined by visual inspection of histograms. Dairy foods were created as servings consumed per 2000 kcal per day. Inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNFα, IL1-β, and CRP) were natural log-transformed, z-score standardized, and summed to create an inflammation score.26 Multivariable linear regression was used to examine associations between each dairy food group (milk, yogurt, cheese, dessert dairy, fat-containing dairy, non-fat dairy, and total dairy) as a continuous variable and BMSi and TBS; participants taking OP meds were excluded from these analyses (n = 5 and 12 for BMSi and TBS, respectively) to avoid spurious predictions of improved bone health.27 General linear regression was performed to compare least squares means of BMSi and TBS across tertiles of intake of each dairy food. Covariates for each model were chosen based on previous research with BMD in this cohort, as well as their contribution to the models as assessed by a change of at least 10% in the β coefficient of the independent variable using the forward partial change in estimate method.28 Tested covariates for BMSi included age, sex, BMI, physical activity, smoking status, alcohol intake, inflammation biomarker score, serum 25OHD, plasma PTH, and serum pentosidine. Tested covariates for TBS were the same except for PTH and pentosidine which have not been shown to be related to trabecular bone. Initial models for BMSi were adjusted for age and sex. Secondary models for BMSi were further adjusted for BMI, and plasma concentration of PTH. Initial models for TBS were adjusted for age, sex, and BMI. No further adjustments were made as no additional covariates met the threshold set forward by the partial change in estimate method. p-trend across tertiles of intake of each dairy group was calculated using general linear modeling. For regression models, if the p value of the estimate and least squares means was ≥.10, the authors inferred no detectable effect. Structural equation modeling (SEM), specifically mediation modeling, was used to test the role of inflammation as a mediator of dairy group associations that were significant or approached significance (p < .1) using the lavaan package in R.29 Inflammatory cytokines were represented in the mediation models as the inflammation score. The mediation analysis uses a system of linked regression-type equations. Specifically, the direct association represents the relation between the independent and outcome variables while controlling for the mediator. The indirect association represents the relation between the independent and outcome variables through the mediator (and is the product of the independent variable to the mediator and the mediator to the outcome variable). The total association is the sum of the direct and indirect effects of the independent variable on the outcome variable. The direct association between dairy groups and BMSi was adjusted for age, sex, BMI, and plasma PTH. Models between dairy groups and TBS were adjusted for sex, age, and BMI. If calculated 95% CI included unity (estimate = 0.0), the authors inferred no detectable effect. Missing values were removed from analyses. All analyses were performed using R Statistical Software (v4.3.0).30

Results

Sample characteristics

More than three-quarters of the sample were women, the majority presented with obesity, had diabetes, and exhibited high concentrations of circulating inflammatory cytokines (Table 1). In general, the sample reported low physical activity, smoking behavior, and alcohol intake. The women were all postmenopausal. Total intake of dairy was ~1 serving/d lower than the Dietary Guidelines for Americans recommended intake; however, it was ~0.5 servings/d greater at the most recent visit compared to intake reported at baseline.10,31 Fat-containing dairy represented the largest group of dairy foods consumed and yogurt the smallest.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants from the Boston Puerto Rican Osteoporosis Studya wave 2 (2019-2022) with diet and bone material strength or trabecular bone score measurements.

| Characteristics | Mean ± SD, or % (n = 412) |

|---|---|

| Age, yr | 70.5 ± 6.9 |

| Women, % | 77.4 |

| BMI (kg/m 2 ) | 31.2 ± 6.5 |

| Physical activity score (range: 10.5-57.9) | 29.4 ± 6.1 |

| Total energy intake, kcal/d | 1965 ± 681 |

| Smoking status (current), % | 15.3 |

| Frequency alcohol intake, % | |

| None or light in past yearb | 79.6 |

| Moderate | 16.7 |

| Heavy | 3.7 |

| Serum 25OHD, ng/mL | 17.8 ± 6.2 |

| Diabetes, % | 60.1 |

| Plasma parathyroid hormone, pg/mL (reference: 4.69-300 pg/mL) | 17.1 ± 34.9 |

| Serum pentosidine, ng/mL (reference: 38-322 ng/mL) | 249 ± 111 |

| Serum hsCRP, mg/L (reference: 0.5-160 mg/L) | 6.4 ± 11.2 |

| Serum TNFα, pg/mL (reference: 15.6-1000 pg/mL) | 9.8 ± 7.2 |

| Serum IL-1β, pg/mL (reference: 0.5-160 mg/L) | 40.5 ± 38.6 |

| Serum IL-6, pg/mL (reference: 7.8-2500 pg/mL) | 3.0 ± 5.6 |

| Inflammation score (range − 8.2 to 7.2) | 0.05 ± 2.3 |

| Bone material strength index (n = 138) | 75.0 ± 8.3 |

| Trabecular bone score (L1-L4) | 1.2 ± 0.2 |

| Dairy groupsc, servings/d | |

| Total | 1.9 ± 0.8 |

| Milk | 1.2 ± 0.8 |

| Yogurt | 0.1 ± 0.2 |

| Cheese | 0.5 ± 0.3 |

| Dessert | 0.2 ± 0.2 |

| Full fat dairy | 2.3 ± 1.0 |

| No fat dairy | 0.3 ± 0.4 |

Participants were 57% European, 27% African, and 15% Native American genetic admixture.

Light alcohol intake = <1 drink/d in women and <2 drinks/d in men.

Total dairy = milk + yogurt + cheese; milk = all percentages of fat.

Associations between dairy food intake and BMSi and TBS

In fully adjusted regression models, BMSi was positively related to higher intakes of total dairy (β = 1.79 ± 0.85, p = .04) and approached significance for milk (β = 1.74 ± 0.90, p = .06) (Table 2). Differences in BMSi across tertiles of milk intake approached significance after adjustment for covariates, with the highest tertile showing higher BMSi, compared to the lowest tertile (T3: 76.99 ± 1.32 servings/d/2000 kcal; T1: 73.57 ± 1.25 servings/d/2000 kcal; p = .06) (Table 3). There were no meaningful differences in BMSi across tertiles of the remaining dairy food groups.

Table 2.

Multivariable associations between dairy groups and BMSi and TBS in participants from the Boston Puerto Rican Osteoporosis Study, wave 2.

| BMSi (n = 138) | TBS (n = 412) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dairy group a | β ± SE | p | β ± SE | p |

| Adjusted modelsb | ||||

| Total dairy | 1.79 ± 0.85 | .04 | 0.001 ± 0.01 | .89 |

| Milk | 1.74 ± 0.90 | .06 | −0.002 ± 0.01 | .84 |

| Cheese | 1.66 ± 2.5 | .51 | 0.009 ± 0.03 | .74 |

| Yogurt | 0.85 ± 4.7 | .86 | 0.049 ± 0.05 | .28 |

| Dessert dairy | −0.88 ± 2.7 | .74 | 0.044 ± 0.03 | .15 |

| Non-fat dairy | 1.88 ± 1.7 | .28 | −0.042 ± 0.02 | .02 |

| Fat-containing dairy | 0.84 ± 0.77 | .28 | 0.016 ± 0.01 | .04 |

Total dairy = milk + yogurt + cheese.

BMSi models adjusted for sex, age, BMI, plasma parathyroid hormone; TBS models adjusted for age, sex, and BMI.

Abbreviations: BMSi, bone material strength index; TBS, trabecular bone score.

Table 3.

Least squares mean BMSi and TBS across tertiles of dairy food intake in participants from the Boston Puerto Rican Osteoporosis Study, wave 2.

| Dairy food groupa | Tertile 1 | Tertile 2 | Tertile 3 | p-trend |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMSi, fully adjustedb | ||||

| n | 46 | 46 | 46 | |

| Total dairy | 75.01 ± 1.21 | 73.10 ± 1.30 | 76.94 ± 1.32 | .27 |

| Milk | 73.57 ± 1.25 | 74.90 ± 1.27 | 76.99 ± 1.32 | .06 |

| Cheese | 74.05 ± 1.25 | 76.38 ± 1.32 | 74.84 ± 1.25 | .63 |

| Yogurt | 74.99 ± 0.80 | 73.09 ± 1.21 | 75.80 ± 1.31 | .64 |

| Dessert dairy | 74.78 ± 1.26 | 75.74 ± 1.29 | 74.64 ± 1.26 | .94 |

| Non-fat dairy | 75.96 ± 1.22 | 72.84 ± 1.27 | 76.19 ± 1.28 | .87 |

| Fat-containing dairy | 75.71 ± 1.27 | 74.73 ± 1.25 | 74.62 ± 1.35 | .54 |

| TBS, fully adjustedc | ||||

| n | 138 | 138 | 137 | |

| Total dairy | 1.20 ± 0.01 | 1.21 ± 0.01 | 1.19 ± 0.01 | .78 |

| Milk | 1.20 ± 0.01 | 1.20 ± 0.01 | 1.19 ± 0.01 | .53 |

| Cheese | 1.20 ± 0.01 | 1.19 ± 0.01 | 1.20 ± 0.01 | .96 |

| Yogurt | 1.17 ± 0.01 | 1.22 ± 0.01 | 1.21 ± 0.01 | .01 |

| Dessert dairy | 1.17 ± 0.01 | 1.20 ± 0.01 | 1.21 ± 0.01 | .03 |

| Non-fat dairy | 1.21 ± 0.01 | 1.20 ± 0.01 | 1.18 ± 0.01 | .14 |

| Fat-containing dairy | 1.18 ± 0.01 | 1.21 ± 0.01 | 1.20 ± 0.01 | .18 |

Values are adjusted least squares means ± SE. BMSi, bone material strength index, TBS, trabecular bone score.

Total dairy = milk + yogurt + cheese; milk = all percentages of fat.

BMSi models are adjusted for sex, age, BMI, and plasma parathyroid hormone.

TBS models adjusted for sex, age, and BMI.

Abbreviations: BMSi, bone material strength index; TBS, trabecular bone score.

In fully adjusted regression models, higher intake of non-fat dairy was associated with lower TBS (β = −.042 ± 0.02, p = .02) and higher intake of fat-containing dairy was associated with higher TBS (β = .016 ± 0.01, p = .04). Differences in TBS were observed across tertiles of yogurt intake after adjustment for covariates, with the highest tertile showing higher TBS, compared to the lowest tertile (T3: 1.21 ± 0.01 servings/d/2000 kcal; T1: 1.17 ± 0.01 servings/d/2000 kcal; p = .01) and across tertiles of dessert dairy with the highest tertile also showing higher TBS, compared to the lowest tertile (T3: 1.21 ± 0.01 servings/d/2000 kcal; T1: 1.17 ± 0.01 servings/d/2000 kcal; p = .03) (Table 3). There were no meaningful differences in TBS across tertiles of the remaining dairy food groups.

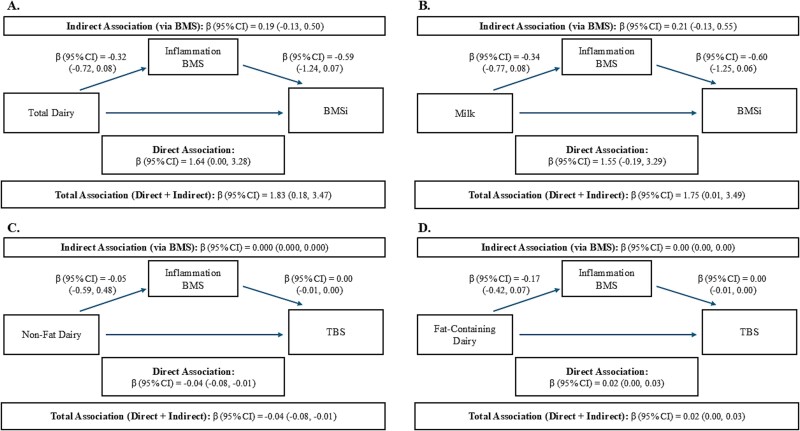

Mediation by inflammatory cytokines in associations between dairy food groups and BMSi and TBS

The four associations between dairy groups and bone outcomes with p < .1, were included in SEM to test for potential mediation by inflammatory cytokines (CRP, IL-6, TNFα, and IL1-β) using the inflammation score. The analysis revealed similar direct associations as the linear regression models; however, indirect tests of the pathways through the inflammation score showed no association, suggesting a lack of mediation via these cytokines. These results suggest that the associations of dairy with BMSi and TBS may be independent of inflammatory mechanisms. Specifically, there were positive direct and total associations with total dairy and milk intake and BMSi, inverse direct and total associations between non-fat dairy and TBS, and a positive association between fat-containing dairy and TBS (Figure 2A-D). The direct path and total effects from SEM chi-square p ≥ .05 (with 4 degrees of freedom), Comparative fit index (CFI) > 0.67, Root Mean Square Error of Assessment (RMSEA) ≥ 0.1, and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) < 0.06 suggested good model fit for BMSi models. Fit statistics for TBS showed models that were less well fit with SEM chi-square p = .00 (with 3 degrees of freedom), CFI < 0.50, RMSEA ≥ 0.1, and SRMR = 0.05. These results suggest good model-data fit, but that the correlations are weak among variables.32

Figure 2.

Direct and indirect (via inflammation score) associations of dairy intakes with BMSi and TBS in participants from the follow-up visit in the Boston Puerto Rican Osteoporosis Study. (A) Depicts associations between total dairy and BMSi via the inflammation score, (B) associations between milk and BMSi via the inflammation score, (C) non-fat dairy and TBS via the inflammation score, and (D) fat-containing dairy and TBS via the inflammation score. All models were adjusted for age, sex, and BMI. The associations of total dairy and milk with BMSi were additionally adjusted for plasma parathyroid hormone. Abbreviations: BMSi, bone material strength index; TBS, trabecular bone score.

Discussion

In this cohort of Puerto Rican adults aged 56-90 yr, dietary intake of total dairy (yogurt + milk + cheese) was associated with BMSi in fully adjusted models, and milk alone was weakly associated. Non-fat and fat-containing dairy groups were associated with TBS in fully adjusted models. Inflammatory cytokines were hypothesized to partially explain the association between dairy foods and TBS and BMSi; however, tests of mediation by a standardized variable comprised of IL-6, TNFα, IL1-β, and CRP did not show significant results.

Extensive research suggests a positive impact of dairy foods on BMD.10,33 While this dietary group is comprised of foods that are varied in their nutritional composition, including fat content, degree of fermentation, and individual nutrients, the group as a whole represents a highly bioavailable source of compounds beneficial to bone quantity including calcium, vitamin D, phosphorus, and protein.8 Far less is known about the influence of dairy foods on measures of bone quality, including whether different aspects of dairy are more relevant to cortical vs trabecular bone health. Earlier work in the BPROS wave 1 demonstrated that higher dairy consumption predicts BMD in those with, but not without sufficient serum 25OHD.10 However, in the current study, 25OHD was not a statistically significant predictor of BMSi or TBS. It should be noted that numerous studies demonstrate the positive influence vitamin D may have on bone,34–36 and the results from the current paper should be interpreted carefully, as fortification of dairy products in the United States, particularly milk, is strongly encouraged, although not federally mandated. Therefore, the influence of some dairy products on bone quality and strength may be due to their fortified vitamin D content, in addition to their unique nutrient density and bioavailability.

The influence of dairy products on bone quality may occur via the action of dairy matrix components on the immune system. Antioxidant peptides in milk were recently shown to increase BMD and cortical bone strength (as measured using the three-point bending test) in ovariectomized rats treated with a casein-derived peptide, compared to controls.13 The positive association of milk intake with BMSi in the current study supports these findings. The absence of an association between cheese, which may or may not be a fermented milk-based product, and BMSi in our study could be due to the type of cheese consumed in this population of Puerto Rican adults—American cheese, which contributes to calcium intake but is not created via fermentation, an important aspect of the maturation process which produces bioactive peptides. Of these peptides, Casoxin A and B, Valyl-Prolyl-Proline, and β-lactotensin have been shown to exhibit antioxidant properties that can have numerous health benefits and likely contribute to the positive association of milk with BMSi.37 In a recent publication from the Framingham Osteoporosis Study with 1226 older men and women, mean age 64 yr, milk was not found to be positively associated with cortical bone strength yet, in women, cheese was inversely associated with cortical BMD at the tibia (β: −9.42, p < .01), and radius (β: −9.61, p = .001).11 These discrepant findings may be due to the lower intake of milk in the Framingham Osteoporosis Study compared to the BPROS (5.6 vs 8.5 servings/wk). Additionally, the 2 studies utilized different tools to measure cortical bone strength; the impact on outcomes of using HRpQCT, an indirect measure (in the Framingham Osteoporosis Study), vs the Osteoprobe, a direct measure (in the current study) is unknown.

Results from the current study reveal a positive association between the intake of fat-containing dairy and TBS, and an inverse association between non-fat dairy and TBS, suggesting that percentage of fat is another component of the dairy matrix that could be influencing bone quality. While the mechanism is not well established, animal studies of other health outcomes suggest that fatty acids in dairy products, such as conjugated linoleic acid (CLA) can exert beneficial effects via inflammatory pathways.38 The conversion of CLA to nitro-conjugated linoleic acid (NO2-CLA) by saliva and by the acidic environment of the stomach has been found to inhibit IL-6 secretion, a cytokine that promotes osteoclast formation, particularly in pathological states.39 Interestingly, researchers have shown that IL-6 exerts its effects on cortical and trabecular bone via cis and trans-signaling pathways, respectively, with inhibition of the trans-signaling pathway in post-ovariectomy mice preventing trabecular bone loss.40 This may explain the positive association of fat-containing dairy with TBS in this study including mainly postmenopausal women. Recent research in 4740 men and women in the Framingham Osteoporosis Study revealed no association between dairy and TBS, but that may be due to the lack of testing of dairy groups based on percent fat.41 A recent analysis of data from NHANES 2011 to 2018, with 8942 adults aged 20-59 yr, provides additional support for the beneficial impact of fatty acids on bone. The fourth quartile of total saturated fatty acid intake (g/d), compared to the first, was associated with greater BMD; as was also seen for total monounsaturated fatty acids and total polyunsaturated fatty acids, suggesting that the fat composition of dairy products may be beneficial for BMD.42

High levels of circulating and BM inflammatory cytokines have been mechanistically linked to low BMD.43 Structural equation model testing in this study of Puerto Rican adults suggested strong overall associations between intakes of total dairy and milk with BMSi and between intakes of fat-containing dairy with TBS; however, there was no suggestion of a mediating role by inflammatory cytokines in these associations. Structural equation modeling model fit indices suggest that the absence of indirect effects was due to weak pathway correlations, as opposed to poor model fit. This contrasts with a recent study in which similar inflammatory cytokines were shown to mediate numerous measures of bone quantity and quality in 183 postmenopausal women (mean 62 yr) from the Prune Study.44 The dissimilar results may be the result of the different study populations: the Prune Study excluded adults with chronic disease while the current study did not. The complication of an individual’s underlying health status on bone outcomes can be appreciated by recognizing the complexity of the inflammatory signaling pathways on bone. The pathways are marked by cross-talk among the numerous hormones, transcription factors, cytokines, and growth factors, direct and indirect actions by the same factors, and systemic as well as local actions by several.45 Especially in populations with underlying chronic illnesses, such as the BPROS, correlation strength between SEM pathways may be improved by testing markers of inflammation that directly influence bone such as NF-κB, activator protein 1, and the MMPs 1, 2, and 9.46,47 An additional consideration is that this cohort of Puerto Rican adults may not exhibit the genetic polymorphisms that have been associated with inflammatory cytokines and OP.48,49 Finally, the potential for measurement error of inflammatory cytokines cannot be discounted.

This study has numerous strengths. It is the first to investigate measures of bone quality and to report on the association of dairy foods in the largest cohort of Puerto Rican older adults living in the US mainland. The use of repeated measures of dietary intake assessed from a culturally tailored and validated FFQ provides confidence in the accuracy of the self-reported responses. However, one limitation to the use of an FFQ is its lack of information on brand of food consumed, meaning it is not possible to disentangle nutrient fortified products from non-fortified products in this study. A limitation of the study is the small sample size for BMSi analyses. To assess the potential for an increased risk of false negatives, a post hoc power calculation was performed in G*Power (v3.1.9.7) using an F test with linear multiple regression, an alpha of 0.05, and an effect size (f2) of 0.06. The resulting power was 82%, suggesting the study had a conventionally accepted level of statistical power.50 The absence of inflammatory mediators known to act directly on bone and the lack of serum 25OHD measurement at the same visit that the bone data were collected represent further limitations. The potential for residual confounding exists in this study, as with all observational studies. To minimize this, we carefully adjusted for potential confounders, including demographics and relevant lifestyle factors and comorbidities. Further, the ability to determine causality is limited by the cross-sectional design of this study. Finally, the specific dietary and lifestyle characteristics of the Puerto Rican population may lessen the generalizability of the findings. Future longitudinal analyses are needed to confirm the results observed here.

Conclusions

Higher intakes of milk and milk + yogurt + cheese were associated with higher BMSi, and higher intake of fat-containing dairy was associated with higher TBS after adjustment for confounders. Higher intake of non-fat dairy was associated with lower TBS. IL-6, TNFα, IL1-β, and CRP, assessed as a standardized biomarker score, did not act as mediators of the observed associations; however, future efforts to elucidate the mechanisms by which dairy foods differentially impact BMSi and TBS may benefit from mediation analyses with inflammatory factors that exert an exclusively direct effect on bone. Another important future step is the determination of the genetic polymorphisms associated with inflammatory cytokines and bone health in Puerto Rican adults.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the valuable help with the trabecular bone score conversion formulas provided by Elise Reitshamer and Elsa Konieczynski of the Jean Mayer USDA Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging, Tufts University, Boston, MA. The authors are also grateful for the numerous laboratory measurements performed by the Garelnabi Lab, Center for Population Health, University of Massachusetts Lowell, Lowell, MA. The authors also wish to extend their gratitude to Xiyuan Zhang of the Center for Population Health, University of Massachusetts Lowell, Lowell, MA for her valuable assistance with data management.

Contributor Information

Lisa C Merrill, Department of Biomedical and Nutritional Sciences, Zuckerberg College of Health Sciences, University of Massachusetts Lowell, Lowell, MA 01854, United States; The Center for Population Health, Zuckerberg College of Health Sciences, University of Massachusetts Lowell, Lowell, MA 01854, United States.

Sabrina E Noel, The Center for Population Health, Zuckerberg College of Health Sciences, University of Massachusetts Lowell, Lowell, MA 01854, United States; Department of Public Health, Zuckerberg College of Health Sciences, University of Massachusetts Lowell, Lowell, MA 01854, United States.

Yan Wang, Department of Psychology, College of Fine Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Massachusetts Lowell, Lowell, MA 01854, United States.

Bess Dawson-Hughes, Jean Mayer US Department of Agriculture Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging, Tufts University, Boston, MA 02111, United States.

Natalia Palacios, The Center for Population Health, Zuckerberg College of Health Sciences, University of Massachusetts Lowell, Lowell, MA 01854, United States; Department of Public Health, Zuckerberg College of Health Sciences, University of Massachusetts Lowell, Lowell, MA 01854, United States.

Katherine L Tucker, Department of Biomedical and Nutritional Sciences, Zuckerberg College of Health Sciences, University of Massachusetts Lowell, Lowell, MA 01854, United States; The Center for Population Health, Zuckerberg College of Health Sciences, University of Massachusetts Lowell, Lowell, MA 01854, United States.

Kelsey M Mangano, Department of Biomedical and Nutritional Sciences, Zuckerberg College of Health Sciences, University of Massachusetts Lowell, Lowell, MA 01854, United States; The Center for Population Health, Zuckerberg College of Health Sciences, University of Massachusetts Lowell, Lowell, MA 01854, United States.

Author contributions

Lisa C. Merrill (Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing), Sabrina Noel (Funding acquisition, Methodology, Writing—review & editing), Yan Wang (Methodology, Writing—review & editing), Bess Dawson-Hughes (Data curation, Methodology, Writing—review & editing), Natalia Palacios (Writing—review & editing), Katherine L. Tucker (Funding acquisition, Methodology, Writing—review & editing), Kelsey M. Mangano (Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Supervision, Writing—review & editing)

Funding

National Institutes of Health grants P01 AG023394, P50 HL105185, R01 AG055948, and R01 AR072741. The study sponsor did not have a role in the design and conduct of the study; in the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or in the preparation of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

K.M.M. received funding from the National Dairy Council for work related to this MS.

Data availability

The procedure for requesting data from the Boston Puerto Rican Osteoporosis Study can be found at https://www.uml.edu/research/uml-cph/.

IRB approval

Study protocols were approved by the IRB at Tufts University and by the University of Massachusetts Lowell. All participants provided written informed consent.

Dr Mangano is the guarantor of this work and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

References

- 1. Noel SE, Mangano KM, Griffith JL, Wright NC, Dawson-Hughes B, Tucker KL. Prevalence of osteoporosis and low bone mass among Puerto Rican older adults. J Bone Miner Res. 2018;33(3):396–403. 10.1002/jbmr.3315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bao Y, Xu Y, Li Z, Wu Q. Racial and ethnic difference in the risk of fractures in the United States: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):9481. 10.1038/s41598-023-32776-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Funk C, Lopez MH. Hispanic Americans’ Trust in and Engagement with Science. Pew Research Center, 2022.

- 4. Ammann P, Rizzoli R. Bone strength and its determinants. Osteoporos Int. 2003;14(Suppl 3):13–18. 10.1007/s00198-002-1345-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shevroja E, Reginster JY, Lamy O, et al. Update on the clinical use of trabecular bone score (TBS) in the management of osteoporosis: results of an expert group meeting organized by the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis, Osteoarthritis and Musculoskeletal Diseases (ESCEO), and the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF) under the auspices of WHO Collaborating Center for Epidemiology of Musculoskeletal Health and Aging. Osteoporos Int. 2023;34(9):1501–1529. 10.1007/s00198-023-06817-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rozental TD, Walley KC, Demissie S, et al. Bone material strength index as measured by impact microindentation in postmenopausal women with distal radius and hip fractures. J Bone Miner Res. 2018;33(4):621–626. 10.1002/jbmr.3338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Feskanich D, Meyer HE, Fung TT, Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Willett WC. Milk and other dairy foods and risk of hip fracture in men and women. Osteoporos Int. 2018;29(2):385–396. 10.1007/s00198-017-4285-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sahni S, Mangano KM, McLean RR, Hannan MT, Kiel DP. Dietary approaches for bone health: lessons from the Framingham Osteoporosis Study. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2015;13(4):245–255. 10.1007/s11914-015-0272-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fabiani R, Naldini G, Chiavarini M. Dietary patterns in relation to low bone mineral density and fracture risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Adv Nutr. 2019;10(2):219–236. 10.1093/advances/nmy073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mangano KM, Noel SE, Sahni S, Tucker KL. Higher dairy intakes are associated with higher bone mineral density among adults with sufficient vitamin D status: results from the Boston Puerto Rican osteoporosis study. J Nutr. 2019;149(1):139–148. 10.1093/jn/nxy234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Millar CL, Kiel DP, Hannan MT, Sahni S. Dairy food intake is not associated with measures of bone microarchitecture in men and women: the Framingham Osteoporosis Study. Nutrients. 2021;13(11):21-26. 10.3390/nu13113940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bermúdez OI, Falcón LM, Tucker KL. Intake and food sources of macronutrients among older Hispanic adults: association with ethnicity, acculturation, and length of residence in the United States. J Am Diet Assoc. 2000;100(6):665–673. 10.1016/s0002-8223(00)00195-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mada SB, Reddi S, Kumar N, et al. Antioxidative peptide from milk exhibits antiosteopenic effects through inhibition of oxidative damage and bone-resorbing cytokines in ovariectomized rats. Nutrition. 2017;43-44:21–31. 10.1016/j.nut.2017.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. He M, Shi B. Gut microbiota as a potential target of metabolic syndrome: the role of probiotics and prebiotics. Cell Biosci. 2017;7(1):54. 10.1186/s13578-017-0183-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cuesta-Triana F, Verdejo-Bravo C, Fernández-Pérez C, Martín-Sánchez FJ. Effect of milk and other dairy products on the risk of frailty, sarcopenia, and cognitive performance decline in the elderly: a systematic review. Adv Nutr. 2019;10(suppl_2):S105–S119. 10.1093/advances/nmy105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Corwin RL, Hartman TJ, Maczuga SA, Graubard BI. Dietary saturated fat intake is inversely associated with bone density in humans: analysis of NHANES III. J Nutr. 2006;136(1):159–165. 10.1093/jn/136.1.159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dawson-Hughes B, Bouxsein M, Shea K. Bone material strength in normoglycemic and hyperglycemic black and white older adults. Osteoporos Int. 2019;30(12):2429–2435. 10.1007/s00198-019-05140-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bridges D, Randall C, Hansma PK. A new device for performing reference point indentation without a reference probe. Rev Sci Instrum. 2012;83(4):044301. 10.1063/1.3693085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Farr JN, Drake MT, Amin S, Melton LJ III, McCready LK, Khosla S. In vivo assessment of bone quality in postmenopausal women with type 2 diabetes. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29(4):787–795. 10.1002/jbmr.2106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Silva BC, Leslie WD, Resch H, et al. Trabecular bone score: a noninvasive analytical method based upon the DXA image. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29(3):518–530. 10.1002/jbmr.2176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Reitshamer E, Barrett K, Shea K, Dawson-Hughes B. Cross-calibration of prodigy and horizon a densitometers and precision of the horizon A densitometer. J Clin Densitom. 2021;24(3):474–480. 10.1016/j.jocd.2021.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mashiba T, Burr DB, Turner CH, Sato M, Cain RL, Hock JM. Effects of human parathyroid hormone (1-34), LY333334, on bone mass, remodeling, and mechanical properties of cortical bone during the first remodeling cycle in rabbits. Bone. 2001;28(5):538–547. 10.1016/S8756-3282(01)00433-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jiang Y, Zhao JJ, Mitlak BH, Wang O, Genant HK, Eriksen EF. Recombinant human parathyroid hormone (1–34) [Teriparatide] improves both cortical and cancellous bone structure. J Bone Miner Res. 2009;18(11):1932–1941. 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.11.1932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nyman JS, Roy A, Tyler JH, Acuna RL, Gayle HJ, Wang X. Age-related factors affecting the postyield energy dissipation of human cortical bone. J Orthop Res. 2007;25(5):646–655. 10.1002/jor.20337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tucker KL, Mattei J, Noel SE, et al. The Boston Puerto Rican Health Study, a longitudinal cohort study on health disparities in Puerto Rican adults: challenges and opportunities. BMC Public Health. 2010;10(1):107. 10.1186/1471-2458-10-107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Byrd DA, Judd SE, Flanders WD, Hartman TJ, Fedirko V, Bostick RM. Development and validation of novel dietary and lifestyle inflammation scores. J Nutr. 2019;149(12):2206–2218. 10.1093/jn/nxz165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Migliorini F, Maffulli N, Colarossi G, Eschweiler J, Tingart M, Betsch M. Effect of drugs on bone mineral density in postmenopausal osteoporosis: a Bayesian network meta-analysis. J Orthop Surg Res. 2021;16(1):533. 10.1186/s13018-021-02678-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Talbot D, Massamba VK. A descriptive review of variable selection methods in four epidemiologic journals: there is still room for improvement. Eur J Epidemiol. 2019;34(8):725–730. 10.1007/s10654-019-00529-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rosseel Y. lavaan: an R package for structural equation Modeling. J Stat Softw. 2012;48(2):1–36. 10.18637/jss.v048.i02 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Team RC. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing [Internet] [Internet]. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2021: Available from: https://www.r-project.org/. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Agriculture USDoHaHSaUSDo . Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020–2025. 9th ed. U.S. Government Printing Office; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rigdon EE. CFI versus RMSEA: a comparison of two fit indexes for structural equation modeling. Struct Equ Model Multidiscip J. 1996;3(4):369–379. 10.1080/10705519609540052 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Shi Y, Zhan Y, Chen Y, Jiang Y. Effects of dairy products on bone mineral density in healthy postmenopausal women: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Osteoporos. 2020;15(1):48. 10.1007/s11657-020-0694-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Barbáchano A, Fernández-Barral A, Ferrer-Mayorga G, Costales-Carrera A, Larriba MJ, Muñoz A. The endocrine vitamin D system in the gut. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2017;453:79–87. 10.1016/j.mce.2016.11.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lauretani F, Bandinelli S, Russo CR, et al. Correlates of bone quality in older persons. Bone. 2006;39(4):915–921. 10.1016/j.bone.2006.03.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Barbour KE, Zmuda JM, Horwitz MJ, et al. The association of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D with indicators of bone quality in men of Caucasian and African ancestry. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22(9):2475–2485. 10.1007/s00198-010-1481-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rangel AHN, Bezerra DAFVA, Sales DC, et al. An overview of the occurrence of bioactive peptides in different types of cheeses. Foods. 2023;12(23):4261-4275. 10.3390/foods12234261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. den Hartigh LJ. Conjugated linoleic acid effects on cancer, obesity, and atherosclerosis: a review of pre-clinical and human trials with current perspectives. Nutrients. 2019;11(2):0370. 10.3390/nu11020370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sims NA. Influences of the IL-6 cytokine family on bone structure and function. Cytokine. 2021;146:155655. 10.1016/j.cyto.2021.155655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lazzaro L, Tonkin BA, Poulton IJ, McGregor NE, Ferlin W, Sims NA. IL-6 trans-signalling mediates trabecular, but not cortical, bone loss after ovariectomy. Bone. 2018;112:120–127. 10.1016/j.bone.2018.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Millar CL, Kiel DP, Hannan MT, Sahni S. Dairy food intake is not associated with spinal trabecular bone score in men and women: the Framingham Osteoporosis Study. Nutr J. 2022;21(1):26. 10.1186/s12937-022-00781-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Fang ZB, Wang GX, Cai GZ, et al. Association between fatty acids intake and bone mineral density in adults aged 20-59: NHANES 2011-2018. Front Nutr. 2023;10:1033195. 10.3389/fnut.2023.1033195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Abdelmagid SM, Barbe MF, Safadi FF. Role of inflammation in the aging bones. Life Sci. 2015;123:25–34. 10.1016/j.lfs.2014.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Damani JJ, De Souza MJ, Strock NCA, et al. Associations between inflammatory mediators and bone outcomes in postmenopausal women: a cross-sectional analysis of baseline data from the prune study. J Inflamm Res. 2023;16:639–663. 10.2147/jir.S397837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Tsukasaki M, Takayanagi H. Osteoimmunology: evolving concepts in bone–immune interactions in health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2019;19(10):626–642. 10.1038/s41577-019-0178-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Osta B, Benedetti G, Miossec P. Classical and paradoxical effects of TNF-α on bone homeostasis. Front Immunol. 2014;5. 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Paiva KBS, Granjeiro JM. Matrix metalloproteinases in bone resorption, remodeling, and repair. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2017;148:203–303. 10.1016/bs.pmbts.2017.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Moffett SP, Zmuda JM, Oakley JI, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-α polymorphism, bone strength phenotypes, and the risk of fracture in older women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(6):3491–3497. 10.1210/jc.2004-2235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Chao T-H, Yu H-N, Huang C-C, Liu W-S, Tsai Y-W, Wu W-T. Association of interleukin-1 beta (-511C/T) polymorphisms with osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Ann Saudi Med. 2010;30(6):437–441. 10.4103/0256-4947.71062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Haile ZT. Power analysis and exploratory research. J Hum Lact. 2023;39(4):579–583. 10.1177/08903344231195625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The procedure for requesting data from the Boston Puerto Rican Osteoporosis Study can be found at https://www.uml.edu/research/uml-cph/.