Abstract

Background

Childhood obesity is a growing global health concern with significant cardiometabolic consequences. While conventional treatment approaches often fail to achieve sustained outcomes, emerging digital health interventions (DHIs)—including mobile applications, educational video games, wearable devices, telemedicine, and social media—offer innovative tools to support lifestyle modifications and enhance therapeutic adherence.

Methods

In this narrative review, we focus on the main evidence regarding the effectiveness of DHIs for pediatric obesity treatment according to target (children vs. children with families) and duration (short- and long-term interventions). We also review their impact on clinical (e.g. body mass index, body composition, etc.), behavioral (physical activity, nutrition, adherence) and psychosocial (motivation, engagement) outcomes. In addition, future trends in the field are also discussed.

Results

DHIs demonstrate short-term effectiveness, especially when they incorporate personalization, interactivity, and family involvement. Mobile applications and educational video games boost nutritional literacy and promote healthy behaviours. Wearable devices encourage physical activity awareness, though adherence often varies. Long-term, family-based interventions help reduce dropout rates and reinforce lasting healthy habits. Guided use of social media can facilitate health education but also exposes users to risks such as misinformation and unhealthy food marketing. Despite these advancements, DHIs still face major challenges, including unequal access, data privacy concerns, and a lack of long-term outcome evaluations.

Conclusion

The increasing prevalence of pediatric obesity underscores the urgent need for effective and sustainable treatment strategies. DHIs represent a promising, scalable approach for managing childhood obesity, but their long-term sustainability and effectiveness remain to be fully established. Ongoing technological advancements—and their thoughtful integration into existing healthcare frameworks—present significant opportunities to develop innovative, patient-centered therapeutic solutions that can improve engagement, adherence, and long-term health outcomes in children and adolescents with obesity.

Keywords: Artificial intelligence, Digital health intervention, Management, Pediatric obesity, Treatment

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

The global rise in pediatric obesity has reached alarming proportions [1], [2], prompting the implementation of various strategies to address its associated health consequences [3], [4], [5], [6]. Despite these efforts, effectively treating childhood obesity remains a significant challenge for both clinical practice and public health [3], [7], [8], [9]. In recent years, digital health interventions (DHIs), including mobile applications, wearable devices, telehealth services, and online platforms, have emerged as promising, scalable, and accessible tools for managing overweight and obesity in children and adolescents [6], [10], [11], [12]. By leveraging technology-driven platforms such as mHealth applications, exergames, teleconsultations, and social media-based peer support, DHIs aim to promote health-related behaviour change and enhance adherence to lifestyle modifications [6].

These interventions have shown moderate success in reducing body mass index (BMI), increasing physical activity, improving dietary behaviours, and fostering positive psychosocial outcomes [[13], [14], [15]]. Their effectiveness is particularly notable when interventions are interactive, personalized, and incorporate family or caregiver involvement [16]. Factors such as integration with clinical care, tailored content, and user-friendly design have been identified as key contributors to the success of DHIs. However, challenges persist, including digital inequities, sustaining long-term user engagement, ensuring data privacy and security, and addressing the heterogeneity of study designs and outcome measures, which limit the generalizability of findings [17,18].

Despite these challenges, DHIs are increasingly recognized as valuable adjuncts to conventional pediatric obesity care and are being integrated into hybrid treatment models that bridge healthcare, family, and community settings [19]. Current evidence supports their short-term efficacy, particularly when combined with traditional interventions and tailored to individual needs [19]. Given the central role of the family environment in pediatric obesity management [20], parental involvement has been identified as a critical factor in the success of DHIs [21].

However, long-term data on the sustainability, scalability, and equitable access to these interventions remain limited [19].

This review aims to provide a comprehensive evaluation of current trends and evidence regarding the use of DHIs in the treatment of pediatric obesity, with a particular focus on their effectiveness, limitations, and potential for integration into clinical and educational settings to enhance long-term health outcomes.

2. Evidence on DHIs for pediatric obesity management

2.1. Text-based and gamification

Recent literature has explored the effectiveness of DHIs—such as text messages, websites, smartphone apps, and gamification—in supporting weight management and improving dietary behaviours among adolescents [17,[22], [23], [24], [25]]. Text message–based interventions have shown potential in adolescent weight management, although evidence of long-term effectiveness remains limited [26].

A recent systematic review evaluated eight studies involving a total of 767 adolescents aged 10–19 years [26]. The primary outcome across these studies was a reduction in BMI. While seven out of eight studies reported decreases in BMI or BMI z-scores (ranging from 1.3 % to 4.5 %), only one study demonstrated a statistically significant reduction after six months. Interventions included both standard and personalized messaging formats. Notably, two studies employing standard messages observed reductions in BMI, whereas four studies using personalized messages based on individual goals did not report statistically significant changes [26]. Communication modalities also varied, with some interventions utilizing one-way text delivery and others incorporating two-way messaging that allowed for interaction with health professionals. These findings suggest that while text-based interventions may enhance short-term weight-related outcomes, further research is needed to determine the most effective formats and durations [26].

A systematic review and meta-analysis by Suleiman-Martos et al. examined the role of gamification in promoting healthy dietary behaviours and improving body composition in children and adolescents [27]. The review included eight clinical trials and found that gamified interventions were generally effective in enhancing nutritional knowledge, encouraging healthier food selection, increasing fruit and vegetable consumption, and reducing intake of sugar-sweetened beverages. These outcomes indicate that gamification strategies can be a promising adjunct in pediatric nutrition education and behaviour change interventions [27].

Overall, digital and gamified tools have shown the potential to influence health behaviours in pediatric populations, though further high-quality, longitudinal studies are warranted to evaluate their sustained efficacy and optimal implementation strategies [26,27].

2.2. Wearable devices

The effectiveness of wearable devices in promoting physical activity and improving health behaviours among children and adolescents has produced mixed results in the literature [[28], [29], [30], [31]].

The Raising Awareness of Physical Activity (RAW-PA) study assessed a 12-week intervention using Fitbit Flex trackers, Facebook videos, and text messages in 275 adolescents [28]. While 70.8 % reported increased motivation and 78.2 % greater awareness of physical activity, only 18.6 % wore the device daily. Despite overall positive feedback, a subset of participants indicated that the intervention duration was excessive and reported challenges with consistent device usage [28] (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Graphical abstract summarizing a multimodal intervention based on the use of wearable technology (Fitbit Flex) to increase physical activity in adolescents [28].

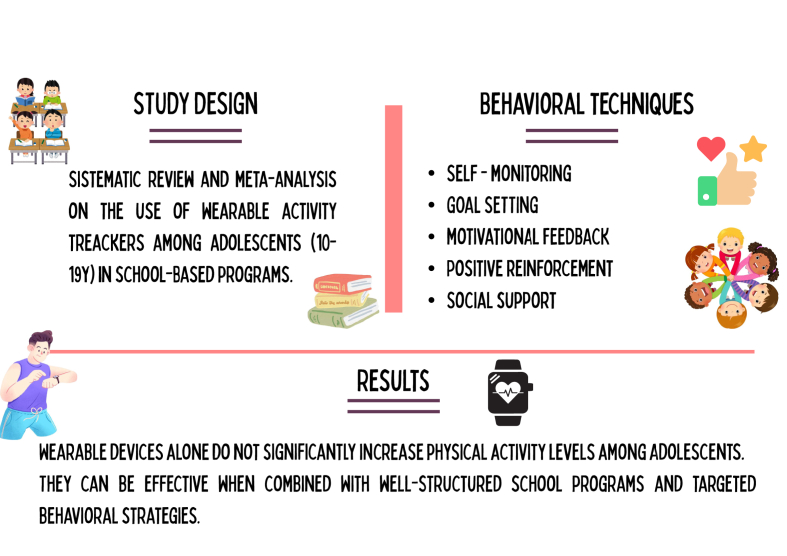

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis by Chen et al. examined 15 school-based studies using wearable activity trackers, including Fitbits, pedometers, and Misfit devices [29]. Most studies reported no significant changes in step count, moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA), or energy expenditure [29] (Fig. 2). However, the iEngage study, which employed Misfit trackers, demonstrated a notable increase in step count, suggesting that device-specific features and intervention design may critically influence the effectiveness of activity-based programs [30].

Fig. 2.

Graphical abstract on the main results of a systematic review on the use of wearable activity trackers in school-based programs [29].

Chimatapu et al. conducted a comprehensive review of wearable technologies extending beyond basic activity tracking [31]. Across 15 studies involving participants aged 6–21 years, wearables were used for diverse health monitoring purposes, including physical activity, physiological assessments, chronic disease management (e.g., diabetes), and biometric data collection. This underscores the broad potential of wearables in supporting health management across different age groups [31].

Several studies have used wearable devices to monitor glycemic variability to identify children at risk for diabetes. Others tracked cardiometabolic parameters such as energy expenditure, heart rate via photoplethysmography, blood pressure, and body fat composition using wrist-based bioimpedance. Additionally, some devices captured daily functional metrics, including dietary intake through wearable cameras and sleep patterns via piezoelectric sensors. These data have proven valuable for clinical assessments and for motivating users to adopt healthier behaviours [31].

Among these studies, only one demonstrated a statistically significant impact of wearable devices on weight and body composition, indicating limited but promising evidence for their role in obesity management [32]. Overall, wearable technologies are safe for pediatric populations and offer a viable alternative to traditional measurement tools by providing real-time, user-generated health data. This functionality supports continuous monitoring and personalized management, particularly in obesity care [32] (Fig. 3). Notably, age influences engagement, with adolescents showing higher motivation and adherence to wearable use compared to younger children, who tend to have lower interest and compliance [33].

Fig. 3.

Graphical abstract on the results of a systematic review and meta-analysis on the effectiveness of wearable activity trackers in promoting physical activity in childhood [32].

3. Interventions on children

3.1. Short-term interventions

A randomized controlled trial (RCT) involving 41 adolescent girls with obesity evaluated the effects of a 12-week exergaming intervention on body composition and cardiovascular risk factors (e.g., blood pressure, cholesterol, triglycerides, glucose, and insulin) [34]. Participants were randomly assigned to group-based dance exergaming (36 h over 3 months) or a self-directed care control. Body composition, including fat mass percentage, total fat mass, and bone mineral density (BMD), was assessed via anthropometry, dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA), and MRI. While no significant changes were observed in BMI or cardiovascular risk markers, the intervention group—specifically those attending ≥75 % of sessions or achieving ≥2600 steps/session—showed significant reductions in subcutaneous abdominal and total adipose tissue, leg fat percentage, and improvements in spine and trunk BMD. These findings suggest that exergaming can effectively improve body composition in adolescents with obesity [34].

A 12-week pilot Turkish RCT investigated the effects of active video games (AVG) on physical fitness, reaction time, self-perception, enjoyment, and parental and child perspectives in inactive, technology-focused children aged 8–13 years [35]. The study found that AVG positively influenced weight and self-perception, suggesting it may be an effective strategy during the peripubertal period to prevent weight gain linked to the “adiposity rebound” phenomenon [35].

In contrast, a study involving 29 children with overweight or obesity evaluated the impact of an active video game (AVG) intervention combined with multicomponent exercise on muscular fitness, physical activity (PA), and motor competence [36]. Participants were randomly assigned to either the intervention group, which engaged in a 5-month program using Xbox 360® Kinect, Nintendo Wii®, dance mats, and BKOOL® interactive cycling alongside multicomponent exercise thrice weekly, or a control group maintaining usual activities. Assessments included accelerometry-measured PA, motor competence, muscular fitness, and lean mass. The intervention group demonstrated significant improvements in muscular fitness, motor skills, and PA levels compared to controls [36].

In this regard, the potential of active video games (AVGs) to improve not only physical activity but also knowledge of healthy nutrition and lifestyle—often referred to as serious games—has recently been explored [37]. Froome et al. evaluated the effectiveness of the serious game “Foodbot Factory” in a single-blinded, parallel, randomized controlled pilot study involving children aged 8–10 years. The study found a significant improvement in overall nutrition knowledge among children who used Foodbot Factory compared to controls, highlighting its value as an educational tool for promoting nutrition awareness [37]. In this context, serious video games designed to improve health—known as “games for health” (G4Hs)—are created with educational and behavioral goals, representing innovative and promising tools for promoting health-related behaviours change [38,39] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Main findings of studies on short-term interventions in children.

| References | Study Design | Population and methods | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| [26] | Systematic Review (median active intervention 4.5 months) | 8 articles selected involving adolescents (aged 10–19 years) with change in BMI as primary outcome. Intervention: text message |

Seven of eight studies showed (median active intervention 4.5 months) a change in BMI or BMI z-score, but only one study was statistically significant. The overall quality of the studies was low. |

| [34] | RCT Duration: 12 weeks |

N = 41 (intervention n = 22, control n = 19) Girls aged 14–18 years, with BMI percentile ≥85th. Intervention: 1 h dance exergaming session, 3 times a week. |

No significant effects on cardiovascular risk factors were reported. EG recorded significant reduction of subcutaneous abdominal adipose tissue (p = 0.048), total adipose tissue (p = 0.01) and leg% fat (p = 0.049) than CG. Significant improvement of spine (p = 0.008) and trunk BMD (p = 0.03) in EG compared to CG was observed. |

| [36] | RCT Duration: 5 months |

N = 29 (EG n = 21, CG n = 8) Children with overweight or obesity recruited from medical centers through their pediatricians of Zaragoza Intervention:1-h sessions three times per week in combination with multicomponent training |

Significant increase of total daily PA, LPA (p = 0.02) and reduction of sedentary behaviour (p < 0.034) occurred in the EG, but no effects on MPA and VPA were detected. Significant improvement of knee extension maximal isometric strength, hand-grip test and CMJ (all p < 0.05) were detected. |

| [38] | Observational, mixed-methods feasibility and acceptability study. Duration: 4–6 weeks. |

N = 34 children (9–12 years) from 4 primary schools in Hong Kong with diverse socioeconomic backgrounds Narrative-based serious video game “Escape from Diab” (9 episodes over 4–6 weeks). Interventions: educational minigames, 3D virtual environment, personalized goal setting, and immersive storytelling |

50 % completed goal setting. Children reported a high immersion score (mean = 39.1 ± 9.0), and 85 % rated enjoyment ≥7/10. No significant improvements in dietary and PA awareness, were found. |

Abbreviations: BMI: body mass index; CG, control group; CMJ: counter movement jump; EG: experimental group; PA: physical activity; LPA: light physical activity; MPA: moderate physical activity; RCT, Randomized controlled trial; VPA: vigorous physical activity.

3.2. Long-term interventions

A 24-week RCT evaluated the effects of AVGs on body composition in children and adolescents with obesity [40]. Positive changes were observed in the intervention group, consistent across subgroups defined by ethnicity, sex, and cardiovascular fitness, underscoring the clinical potential of AVGs for pediatric obesity management [40].

An Italian study involving 64 male elementary school children reported more encouraging outcomes, with exergaming sessions conducted three times weekly over six months leading to significant improvements in BMI, body weight, and fat mass compared to controls who maintained standard physical activity [41]. Although engagement and enjoyment scores measured by the PACES questionnaire were initially higher in the exergaming group, these effects were not sustained. Additional benefits included enhanced aerobic fitness, standing long jump distance, and flexibility, suggesting that exergaming may be a viable and enjoyable component of physical education programs targeting childhood obesity [41].

A 3-year longitudinal study assessed the impact of an educational program incorporating motor games, AVGs, and virtual learning environments on healthy habits and nutritional knowledge among 64 children with obesity aged 6–12 years [42]. Significant improvements in nutrition knowledge and eating behaviours were reported in the intervention group versus controls, highlighting the effectiveness of gamified educational programs supported by information and communication technologies in motivating children and improving dietary habits [42].

The PEGASO e-Diary project examined a mobile food recording application designed to monitor and influence adolescent dietary behaviours, focusing on adherence to the Mediterranean diet [43]. Behavioral analyses revealed modest yet significant increases in fruit and vegetable consumption—an 18 % rise in adolescents consuming at least two servings of fruit per day and a 17 % increase for vegetables. Despite these improvements, 29 % of participants still consumed only one serving daily, indicating ongoing dietary insufficiencies. User engagement data showed that while 83.2 % of participants used the app at least once, maintaining consistent long-term engagement was challenging. No significant changes were observed in other dietary target behaviours, highlighting the limited impact beyond fruit and vegetable intake. These findings emphasize the promise of mobile health technologies in facilitating short-term dietary improvements but also reveal the need for enhanced behavioral strategies and app design to sustain long-term effectiveness [43] (Table 2).

Table 2.

Main findings of studies on long-term interventions in children.

| References | Study Design | Population and methods | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| [40] | Parallel RCT Duration: 24 weeks |

N = 322 (EG n = 160, CG = 162) Children with overweight or obesity aged 10–14 years, regularly using sedentary video games Intervention: active video game to play at home. Subgroup analysis (baseline outcome, age, sex, and ethnicity) |

At 24 weeks, significant differences for BMI, BMI Z-score, and body fat percentage were found in EG vs. CG. No statistically significant interactions were observed between the treatment and any subgroups across all regression models (p = 0.36 to 0.93). |

| [41] | Group-RCT Duration: 6 months |

N = 64 (intervention n = 32, control n = 32) Male children, between 9 and 10 years old, from an elementary school in Italy Intervention: 45 min exergaming sessions (Kinect Adventures) 3 times a week + supplementary physical activity outside the regular school program |

BMI (-1.6 in EG vs 0 in CG), body weight (-2.3 in EG vs +1 in CG), and relative fat mass, (-1.7 in EG vs, +0.5 in CG) showed a significant reduction (all p < 0.001). Significant improvement of aerobic fitness (+80.51 ± 10.66 m in EG, p = 0.004 vs + 10.4 2.59 m in CG, p = 0.485) and flexibility (+75 % in EG vs + 28 % in CG (p < 0.001) was observed. No significant improvement in standing long jump test was found (150.20 ± 6.1 cm in EG vs 149.92 ± 6.8 cm in CG, p > 0.05). No sustained children enjoyment after 20 weeks. |

| [43] | Longitudinal observational multicenter study. Duration: 6 months. |

N = 357 adolescents (13–16 years) from 4 European countries (Italy, UK, Spain, Netherlands) Mobile app “e-Diary” for real-time food tracking, gamification features, notifications, personalized suggestions, visual feedback and dietary indices. |

Both fruit and vegetable intake significantly increased (p < 0.0001 and p = 0.0087, respectively) Adolescents with app usage >2 weeks demonstrated significantly higher odds of breakfast consumption adherence over the study duration (aOR 2.5, 95 % CI 1.0–6.3). A higher engagement among females (aOR 3.8, 95 % CI 1.6–8.8), participants 14-year-olds (aOR 5.1, 95 % CI 1.4–18.8), and adolescents with self-reported good health (aOR 4.2, 95 % CI 1.3–13.3) was found. |

Abbreviations: aOR, adjusted odds ratio; BMI, body mass index; CG: control group; EG: experimental group; RCT, Randomized controlled trial.

4. Community-based interventions

Despite high dropout rates in pediatric obesity treatment—reaching up to 50 % after one year [44,45]—there is growing evidence that integrating DHIs into family, school, and healthcare settings can offer an effective alternative to traditional strategies [21,46]. The effectiveness of DHIs has been assessed across various settings (e.g. family, school, and healthcare environments) and intervention durations (short- and long-term), showing a range of positive outcomes [19,[47], [48], [49]].

4.1. Short interventions

An elegant 10-week intervention study investigated the effectiveness of exergames within a comprehensive weight management program for children and adolescents with obesity [50]. The program combined weekly group exergaming sessions, nutritional education, and psychological support, with mandatory parental involvement. Exergames transformed screen time into interactive physical activity (e.g., dancing, cycling, tennis simulation), resulting in an 83 % completion rate (n = 40), a significant reduction in BMI z-score (–0.072, p < 0.0001), and a decrease in BMI (–0.48 kg/m2, p = 0.002). Additionally, improvements were observed in self-reported screen time, soda consumption, physical activity, and self-esteem. These findings support the use of exergames as an engaging and effective component of pediatric obesity interventions when paired with family involvement.

Similarly, Trost et al. assessed AVGs in a 16-week family-based behavioral program without specific usage guidelines [51]. Participants in the intervention group showed a significant reduction in BMI z-score and percentage overweight, along with increased MVPA (+7.4 min/day) and vigorous physical activity (+2.8 min/day), aligning with World Health Organization (WHO) recommendations for child activity levels [52].

Beyond gaming, mobile health tools such as text messaging (e.g. short message service (SMS)) have shown promise in supporting family-based interventions. Armstrong et al. implemented a 12-week program involving daily motivational texts to parents of children aged 5–12 in a pediatric obesity program [53]. While no significant changes in BMI z-score were observed, 80 % of parents responded to at least one message, and 95 % found them helpful for making healthier decisions. Importantly, families in the intervention group attended significantly more follow-up visits (3.3 vs. 2.1, p < 0.001), particularly notable given the predominance of low-income families at high risk of dropout.

Further supporting SMS-based strategies, Norman et al. evaluated the “Adventure & Veg” intervention, which included five weekly text messages and access to a closed Facebook group [54]. The 8-week program led to increased vegetable intake (+0.45 servings/day, p = 0.001) and greater variety of vegetables consumed (+1.85 types/week, p < 0.001). Children also expanded the variety of physical activities performed, although no change in total physical activity hours was observed. While participants appreciated the SMS component, the Facebook group was less effective due to poor visibility and engagement.

A systematic review of 15 studies further confirmed parental satisfaction and feasibility of digital tools such as SMS, email, social media, video calls, web platforms, and mobile apps [55]. While SMS was often rated the most useful component, families expressed a preference for more interactive formats, such as apps and telehealth platforms, over SMS or Facebook for continued use [56]. Notably, this preference may reflect a sample bias favoring participants with higher digital literacy.

The feasibility and impact of family-centered web-based programs have also been demonstrated. Zhu et al. evaluated a 10-week online intervention involving 148 children with overweight or obesity (aged 7–13), combining weekly modules with professional support via phone consultations [57]. The intervention group experienced a significant reduction in BMI z-score (–0.13) along with improvements in diet, physical activity, and quality of life. Notably, 89 % of families completed all activities, indicating that digital formats offer flexibility and accessibility compatible with daily life.

Kahana et al. studied a 5-month multicomponent intervention combining behavioral counseling, physical activity sessions, dietary consultations, and healthy cooking classes for children and parents [58]. The use of an exergaming app during one weekly physical activity session contributed to a significant BMI reduction and improvements in various fitness parameters, including agility, coordination, endurance, and aerobic capacity [58].

Collectively, these findings suggest that DHIs—particularly when embedded in broader behavioral, educational, and family-based frameworks—can initiate meaningful short-term changes in weight-related behaviours [55]. However, longer-term interventions are needed for sustained weight outcomes [55] (Table 3).

Table 3.

Main findings of studies on short interventions in children and family.

| References | Study Design | Population and methods | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| [35] | Parallel RCT Duration: 12 weeks |

N = 106 Intervention = 53 Control = 53 Children aged 8–13 years old, inactive and with technological preoccupation, recruited from randomly selected elementary public schools Children in EG alternatively played Nintendo Wii AVGs from different categories (sports, balance, aerobics, resort and training) for 50–60 min, 3 days a week. |

Weight gain occurred in both groups (+0.53 in EG vs +1.9 in CG, p < 0.01). BMI (-0.33 in EG vs – 0.66 in CG, p = 0.001) and BMI z-score (-0.13 in EG vs +0.21 in CG, p = 0.0001) significantly decreased No significant changes in Fat Ratio % were observed. Visual and auditory reaction time of both dominant and non-dominant hands significantly decreased in EG (p < 0.01). |

| [50] | Prospective observational pilot study Duration: 10 weeks |

48 children and adolescents (26 males and 22 females) aged between 8 and 16 years (mean age 11.2 ± 2.2 years), with BMI ≥85th percentile. Parental involvement. |

Significant BMI z-score reduction, improvement in global self-esteem, and behavioral conduct were found (p < .0001, p = 0.034, and p = 0.037, respectively), Significant reduction in screen time (3.4 vs 2.75 h, p < 0.047), in consumption of sweet drinks (4.27 vs 2.75/day, p < 0.026) and in time spent in front of the TV during the meal (p < 0.020) were reported. Significant increase in weekly physical activity (3.7 vs 5.9 h, p < 0.02) was also reported. |

| [51] | Group-RCT Duration: 16 weeks |

N = 60 (intervention n = 26, control n = 34 Children with overweight or obesity recruited from YMCAs and schools located in Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Texas. All participants underwent a comprehensive family-based weight management program (JOIN for ME). Intervention: EG received a game console and motion capture device and 1 active sports game at their second treatment session. A second active game was provided at week 9 of the program. |

Significant reduction of BMI z-score (-0.25 in EG vs -0.11 in CG, p < 0.001) and of percentage overweight (-10.9 % in EG vs -5.5 % in CG, p = 0.02) was reported. Both MVPA (+7.4 min/day in EG vs -0.6 min/day in CG) and VPA (+2.8 min/day in EG vs -0.3 min/day in CG) significantly increased in the EG (p < 0.05). |

| [53] | RCT Duration: 12 weeks |

101 children aged between 5 and 12 years with BMI ≥95th percentile Children and their parents were randomly assigned to: - CG: standard care at the clinic -EG: standard care + daily text messages sent to the parent and inspired by the motivational interview |

Mean participation in clinical visits was higher in EG vs. CG (p < 0.001). After 12 weeks, mean change BMI z-score was not significant (p = 0.20) Change in parent BMI did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.11) |

| [54] | Two-arm RCT Duration:8 weeks |

242 parents or caregivers of children of primary school age. Participants were randomly assigned to either the intervention group or the control group EG: - Five one-way text messages per week, focusing on: vegetable consumption, outdoor physical activity, and reducing time in front of screens. -A closed Facebook group with posts suggesting free, outdoor activities. -An A4 paper planner (Adventure & Veg planner and tracker) sent home, to plan and monitor the children's weekly diet and exercise behaviour. |

Significant increased vegetable consumption in EG by 0.45 servings/day compared to CG was reported (p = 0.001). EG also consumed 1.85 more varieties of vegetables during the week (p < 0.001). Parents in the EG increased their daily consumption of vegetables by 0.44 servings (p = 0.01). Children in the EG performed 0.64 more physical activities per week than CG (p = 0.022). A high acceptability was reported (94 %) 88 % of participants completed the follow-up. |

| [57] | RCT Duration: 10 weeks |

148 children (125 families) aged between 7 and 13 years, with BMI ≥85th percentile according to CDC criteria. Of these, 102 children (85 families) completed the study. Randomised assignation to one of the two groups: -EG:10-week online programme -CG |

Significant reduction in BMI z-score in the EG than CG was observed (p = 0.018) Significant improvement in quality of life was reported: +11 points according to parents (vs +1 of control group), p < 0.001; +7 points according to children (vs +2 of control group), p = 0.034. Significant improvement in diet quality was observed (p < 0.001) A significant median increase in physical activity time (5.2 min per day) was reported (p = 0.022) |

| [58] | Non-RCT Duration: 5 months |

N = 95 (EG n = 41, CG n = 54) Children (median age 10 years) with overweight or obesity. All participants followed PA sessions led by a fitness trainer, nutritional consultation sessions with a dietitian and healthy cooking workshop for both children and parents The EG had access to exergame apps (Just Dance Now and Motion Sports). |

Significant BMI reduction (-2.1 in EG vs -0.7 in CG, p < 0.0001) was observed, even if BMI percentile remained high (99th in both groups). The EG showed significant improvement in speed and agility (4 × 10 m run -0.9 s, p < 0.0001), leg strength endurance (wall sit-up test +14.9 s, p = 0.0002), aerobic component (yo-yo running distance +60 m, p < 0.0001), and handgrip (dynamometer +1 kg, p = 0.0029) Increase of hand-eye coordination was not significant (p = 0.18). |

Abbreviations: ARFS: Australian Recommended Food Score; AVG: Active video game; BMI: body mass index; CG: control group; EG: experimental group; MVPA: moderate to vigorous physical activity; PA: physical activity; RCT, Randomized controlled trial; VPA: vigorous physical activity.

4.2. Long-term interventions

A large American multicenter RCT conducted across six pediatric outpatient clinics evaluated the effectiveness of two community-based, year-long interventions in 721 children with BMI ≥85th percentile [59]. One group received enhanced primary care, including electronic medical record alerts, monthly messages, and educational materials for parents. The second group received individualized health coaching in addition to enhanced care, incorporating biweekly text/email messages, personalized goal- setting via motivational interviewing, and participation in the Cooking Matters program. Both groups demonstrated modest but statistically significant reductions in BMI z-score (–0.06 and –0.09, respectively), with no significant difference between groups. However, the coaching group reported improved health-related quality of life (as measured by the PedsQL), and both groups showed increased parental empowerment in managing child weight [59].

Family-centered digital strategies, especially when integrated with in-person elements, have shown promising results in promoting engagement and lifestyle change. The REDUCE (REorganise Diet, Unnecessary sCreen time and Exercise) program in Malaysia used a mixed-methods approach combining face-to-face sessions with digital communication via Facebook and WhatsApp [60]. Among 8–11-year-old children with overweight or obesity, the intervention led to a significant reduction in BMI z-score (–0.10; p = 0.045) and waist circumference percentile (p = 0.021) after six months. Parents reported enhanced communication with their children and increased awareness of food choices. The program demonstrated that blended delivery models—unlike interventions relying solely on digital or in-person components—may yield better adherence and outcomes [[60], [61], [62]].

A randomized trial involving 1,392 elementary school Chinese children further demonstrated the efficacy of multifactorial interventions using digital tools [63]. The 1-year intervention included health education, physical activity promotion, and family engagement via a smartphone app. Teachers used the app to upload anthropometric data, while families accessed it to track children's progress. The prevalence of obesity decreased by 27.0 % in the intervention group versus 5.6 % in controls, along with improvements in dietary and physical activity behaviours [63].

In Sweden, Hagman et al. evaluated Evira, a digital platform integrated with clinical care, which included a mobile app connected to a scale that displayed personalized BMI z-score trajectories [64]. Families and healthcare providers could monitor progress and communicate regularly. After one year, the Evira group showed a significantly greater reduction in BMI z-score (–0.30 vs –0.15), and a higher percentage of participants achieved clinically significant weight loss (≥0.25 BMI z-score: 45.8 % vs 30.5 %). Obesity remission was also more frequent in the Evira group (25.2 % vs 17.8 %). Long-term follow-up at three years confirmed these benefits, with sustained BMI z-score reductions (–0.29 vs –0.12) and higher obesity remission (31.8 % vs 18.7 %) [65]. Family engagement emerged as a critical factor in both short- and long-term success.

A 12-month Italian RCT assessed the Nutrilio mobile app (M-App) as a digital adjunct to traditional nutritional counseling for children and adolescents with obesity [66]. The experimental group used the app for the first six months, followed by a six-month follow-up without app access. Although there was no sustained BMI z-score reduction, the intervention group demonstrated a significantly lower dropout rate compared to controls. Moreover, 53.3 % of M-App users reported improved eating habits, including increased fruit and vegetable consumption and reduced intake of sugary drinks. These findings suggest that mobile apps with educational and feedback features can enhance engagement and reduce attrition in pediatric obesity management [66], consistent with similar findings in adult populations [67] (Table 4).

Table 4.

Main findings of studies on long-term interventions in children and family.

| References | Study Design | Population and methods | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| [42] | Longitudinal experimental study. Duration: 2 annual phases with a total duration 3 years. |

N = 46 children with obesity (6–12 years), recruited from hospitals and primary schools in the Canary Islands Gamified educational program: 12 weekly 2-h face-to-face sessions, active video game (TANGO:H), home-based physical activity using Wii Fit Plus, parental education with virtual platforms (Moodle, ClassDojo). |

Nutritional knowledge significantly improved over time (p < 0.001). The KIDMED index increased in the EG (7.67–7.75) and decreased in the CG (7.11–6.68), but differences were not statistically significant. Consumption of vegetables, fish and cereals rose increased, while intake of industrial pastries dropped from 8.3 % to 0, but differences were not statistically significant. |

| [49] | Pragmatic clinical trial | Participants in the experimental group had already taken part in the previous 1-year study with Evira (see above) The aim was to evaluate the long-term effects (3 years) of integrating Evira digital support in the treatment of pediatric obesity compared to standard treatment |

After 3 years, a reduction in BMI z-score of –0.29 in the EG and of –0.12 in the CG (p = 0.02) was found. An obesity remission of 31.8 % was observed in the digi-physical group and of 18.7 % in standard care group (p = 0.0046) A non-retention rate of 42 % was reported in digi-physical group, of 55 % in the control group (p = 0.0002) |

| [59] | Two-arm RCT | 721 children aged between 2 and 12 years, with a BMI ≥85th percentile. children were randomly assigned to one of the two groups: - Enhanced Primary Care - Enhanced Primary Care + Contextualised Coaching |

After 1 year, the difference between groups in BMI z-score was not significant (p = 0.39). At one year, 9.3 % of the children in the primary care group and 11.6 % in the group with coaching were no longer overweight or obese Improvement in the quality of life of children (+1.53 in the PedsQL score was reported only in the group with coaching parents. 53 % of the parents in the primary care group reported being satisfied with the content of the messages received. In the group with coaching, 72 % indicated high levels of satisfaction |

| [60] | RCT | 134 parent-child dyads Children age was between 8 and 11 years. All of them had BMI z-score > +1 SD. Parents had to have basic digital skills, internet access and willingness to use social media. Parent-child dyads were randomly assigned to the two groups: -intervention group -waiting list control group The REDUCE program lasted 4 months: - 4-week training phase, with two in-person sessions and two via Facebook. −12-week booster phase via WhatsApp, with materials, support, personalized feedback and direct interaction between parents and researchers. |

After 6 months, the intervention group showed a significant reduction in BMI z-score (0.10 vs. 0.02, p = 0.045), and a significant reduction in waist circumference percentile of -3.18 points compared to the control group (p = 0.021) 91 % of dyads completed the study, 96.9 % used WhatsApp, and 81 % used Facebook. 69 % participated in the first in-person session and 42 % in the second one. |

| [63] | Cluster RCT Duration: 9 months (a school year) |

1,392 children aged 8–10 years from 24 elementary school located in three Chinese regions with different socioeconomic characteristics and with an average BMI of 18.6 The schools were randomly assigned into two groups: −12 schools in the intervention group −12 in the control group. Intervention involved schools and families promoting a healthy diet and physical activity to support behavioral changes. An innovative element was the use of a smartphone application. |

A mean BMI difference between groups of -0.46 (95 % CI, −0.67 to −0.25; p < 0.001) and a mean waist circumference difference between groups at the end of trial of -1.63 (95 % CI, −2.82 to −0.43) were found. A reduction in the prevalence of obesity was also reported (27 % in the EG vs 5.6 % in the CG). |

| [64] | Pragmatic clinical trial Duration: 1 year |

107 children and adolescents (age 4.1–17.4 years) treated with digital support. 321 age- and sex-matched controls treated with standard care Intervention group received a digital support (Evira): -Daily home weighing with a scale connected via Bluetooth to a mobile application. -Graphical display of the BMI Z-score with personalized target curves. -Continuous monitoring by the medical staff via a web platform. -Frequent written communication between the clinic and families via the app. The control group received standard treatment based on lifestyle modifications according to the national pediatric recommendations. |

After 1 year, a reduction in BMI z-score was observed (−0.30 ± 0.39 in the digital support group vs −0.15 ± 0.28 in the standard care group, p = 0.0002) Significant BMI z-score reduction in the EG vs. CG was reported (45.8 % vs. 30 %, p = 0.004). No significant obesity remission between the groups was observed (25.2 % vs. 17.8 %, p = 0.09) |

| [66] | RCT Duration: 12 months |

Children and adolescents aged 6–12 years with BMI ≥95th percentile according to WHO curves EG received standard treatment (nutritional, physical and psychological counseling) plus 6 months of use of a mobile application (Nutrilio). CG received standard treatment only. |

After 6 months, the dropout for EG was 40 % and 72 % for CG (p = 0.02). BMI z-score median reduction was similar between groups (p = 0.51) After 12 months, the dropout between the groups was not significant (80 % vs. 92 %, p = 0.24). No significant differences in BMI z-score between the two groups at 12 months were observed (p > 0.05). |

Abbreviations: BMI: body mass index; CG, control group; EG, experimental group; REDUCE: REorganise Diet, Unnecessary sCreen time and Exercise; PedsQL: Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory; RCT, Randomized controlled trial; SD, standard deviation; WHO, World Health Organization.

5. Impact of social media on pediatric eating habits and behaviours

Over recent years, social media platforms—Instagram, TikTok, YouTube, and Facebook—have become deeply embedded in the daily lives of children and adolescents, significantly influencing their preferences, behaviours, and cultural perceptions [68,69]. This widespread use has prompted researchers and public health professionals to explore structured DHIs integrated within these platforms as potential tools for preventing childhood obesity [69].

Notably, the 14-week SanoYFeliz e-Health program—which incorporates personalized nutrition and physical activity guidance, peer interaction, and virtual incentives—demonstrated significant improvements in BMI percentiles, PAQ-A scores, and KIDMED dietary scores among adolescents [70]. Similarly, the “Adventure & Veg” intervention combined regular text messaging with Facebook support to increase daily vegetable intake by +0.45 servings and broaden dietary variety by +1.85 types per week in children, with comparable gains in parental habits [54].

Despite these successes, social media also facilitates obesogenic messaging by promoting high-calorie, nutrient-poor foods through food challenges, fast-food advertisements, and influencer endorsements using animated content and digital rewards [[71], [72], [73], [74]].

Notably, studies have reported significant correlations between exposure to such misleading nutritional information and increased BMI in pediatric populations, underscoring the potential impact of these platforms on unhealthy weight trajectories among youth [75,76].

Of concern, studies indicate that children are susceptible to these persuasive techniques, even when they recognize marketing intent [[77], [78], [79]], and that social platforms routinely disseminate nutritionally inaccurate information [78,80,81]. For instance, only 36 % of TikTok videos tagged “#WhatIEatInADay” contained fully accurate nutritional data [80], while Instagram posts with “#weightloss” predominantly featured thin or muscular body types, with minimal mention of nutritional or physical activity advice, raising concerns about negative impacts on adolescent body image and mental health [81].

Naderer et al. found that approximately two-thirds (67 %) of food cues in 162 YouTube videos by German-speaking youth influencers promoted products classified as inappropriate for children under WHO guidelines, with 46.5 % of branded items non-permitted vs. only 7.7 % permitted (p < 0.001); prohibited foods were also more likely to receive positive framing (36.9 % vs. 28.1 %, p < 0.001) [78]. Additionally, analysis of 1,373 social media posts from Canadian adolescent influencers showed that male‐targeted content promoted unhealthy food in 89 % of cases, compared to 54 % in female‐targeted posts [68].

These findings reveal that algorithm-driven content delivery and lack of sponsorship disclosure amplify youth exposure to unhealthy food marketing. Given the inadequacy of voluntary self-regulation [69], enforceable advertising restrictions and digital media literacy initiatives are critical to safeguard children [69,71,78,80].

In summary, while social media offers a promising channel for delivering scalable, evidence-based DHIs, its dual role in disseminating unhealthy marketing underscores the urgent need for a comprehensive public health approach integrating regulatory oversight and digital literacy efforts with thoughtfully designed, health-promoting digital interventions [68,74,78,80].

6. Novel insights from emerging DHIs

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is emerging as a valuable tool in pediatric obesity management, offering enhanced precision, personalization, and scalability of interventions [82]. By analyzing large-scale datasets, AI can identify complex patterns across behavioral, genetic, and environmental factors, enabling early risk detection and tailored prevention strategies [82]. Machine learning models support the development of individualized risk profiles and predict treatment responses, allowing for adaptive, patient-specific care [[82], [83], [84]]. AI-driven tools—such as chatbots, virtual coaches, and wearable-integrated systems—facilitate real-time monitoring, personalized feedback, and sustained engagement [[82], [83], [84]]. While the field is still developing, and concerns remain regarding data privacy, bias, and clinical validation, preliminary evidence suggests that AI holds considerable promise for improving decision-making, optimizing resource use, and supporting long-term outcomes in pediatric obesity treatment [82,85].

7. Conclusions

Pediatric obesity remains a critical public health challenge worldwide, with rising prevalence and significant long-term health consequences [1,3]. Traditional management approaches often encounter barriers including limited accessibility, low adherence, and variable patient engagement [3].

In recent years, advancements in technology have enabled DHIs to address the complex behavioral, physiological, and environmental determinants of pediatric obesity [5,6]. Leveraging mobile applications, wearable devices, telemedicine, AI, gamification, and AR, DHIs offer scalable, engaging, and potentially cost-effective solutions to promote healthy behaviours and support weight management among children and adolescents [6,10,12].

These interventions can help overcome key limitations of conventional treatment approaches, including geographic and financial barriers, and are particularly effective when parental involvement is integrated [6,12,13].

Emerging innovations are increasingly incorporating AI, genetic and epigenetic profiling, and multi-modal data from wearable sensors and mobile platforms to enable precision-based, personalized interventions [[85], [86], [87]]. Such tools facilitate early risk identification and the delivery of adaptive, data-driven treatment strategies, marking a shift toward proactive and individualized pediatric obesity care [87].

While current evidence supports the short-term efficacy of DHIs, their long-term effectiveness, sustainability, and equity remain poorly explored [5,6]. Future research should emphasize rigorous and standardized methodologies, including consistent study designs, uniform outcome measures, and extended follow-up periods. Additionally, the adoption of user-centered design principles may enhance the usability, acceptability, and overall impact of DHIs in pediatric obesity management.

7.1. Three bulleted key takeaway clinical messages

-

1.

Childhood obesity represents a growing health challenge worldwide that requires timely and multifaceted interventions.

-

2.

Despite the limited success of conventional treatments, digital health interventions (DHIs) are emerging as promising therapeutic strategies. However, evidence supporting their long-term effectiveness remains moderate.

-

3.

The development and integration of advanced technological tools may substantially improve the effectiveness of interventions targeting childhood obesity.

Informed consent statement

Not applicable.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, VF and ADS; methodology, ADS, PM and EMDG Literature search and data curation, AM, DC, NM, GF and PDF; writing—original draft preparation, VF and ADS.; writing—review and editing, ADS, PM, and EMDG; visualization, EMDG and ADS; supervision, ADS and EMDG. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional review board statement

Not applicable.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the paper are included in the review article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Declaration of artificial intelligence (AI) and AI-assisted technologies

The authors did not use AI during the preparation of this manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

This article is part of a special issue entitled: Obesity in Children and Adolescents and Therapy published in Obesity Pillars.

Contributor Information

Vittoria Frattolillo, Email: vitto.fratt@gmail.com.

Alessia Massa, Email: alessiamassax@gmail.com.

Dalila Capone, Email: dalilacapone@hotmail.it.

Noemi Monaco, Email: monaconoemi1@gmail.com.

Gianmario Forcina, Email: gianmario.forcina@gmail.com.

Pierluigi Di Filippo, Email: pierluigi.difilippo94@gmail.com.

Pierluigi Marzuillo, Email: pierluigi.marzuillo@unicampania.it.

Emanuele Miraglia del Giudice, Email: emanuele.miraglia@unicampania.it.

Anna Di Sessa, Email: anna.disessa@unicampania.it.

References

- 1.Hannon T.S., Arslanian S.A. Obesity in adolescents. N Engl J Med. 2023;389:251–261. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp2102062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang X., Liu J., Ni Y., et al. Global prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2024;178:800. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2024.1576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lister N.B., Baur L.A., Felix J.F., et al. Child and adolescent obesity. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2023;9:24. doi: 10.1038/s41572-023-00435-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kassim P.S.J., Muhammad N.A., Rahman N.F.A., et al. Digital behaviour change interventions to promote physical activity in overweight and obese adolescents: a systematic review protocol. Syst Rev. 2022;11:188. doi: 10.1186/s13643-022-02060-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yien J.-M., Wang H.-H., Wang R.-H., et al. Effect of mobile health technology on weight control in adolescents and preteens: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Public Health. 2021;9 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.708321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flølo T.N., Tørris C., Riiser K., et al. Digital health interventions to treat overweight and obesity in children and adolescents: an umbrella review. Obes Rev. 2025;26 doi: 10.1111/obr.13905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nicolucci A., Maffeis C. The adolescent with obesity: what perspectives for treatment? Ital J Pediatr. 2022;48:9. doi: 10.1186/s13052-022-01205-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manco M. Reframing obesity in children. JAMA Pediatr. May 2025 doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2025.1038. Epub ahead of print 19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhutta Z.A., Norris S.A., Roberts M., et al. The global challenge of childhood obesity and its consequences: what can be done? Lancet Global Health. 2023;11:e1172–e1173. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(23)00284-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alotaibi M., Alnajjar F., Cappuccio M., et al. Efficacy of emerging technologies to manage childhood obesity. DMSO. 2022;15:1227–1244. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S357176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Porri D., Morabito L.A., Cavallaro P., et al. Time to act on childhood obesity: the use of technology. Front Pediatr. 2024;12 doi: 10.3389/fped.2024.1359484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Luca V., Virgolesi M., Vetrani C., et al. Digital interventions for weight control to prevent obesity in adolescents: a systematic review. Front Public Health. 2025;13 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1584595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Islam M.M., Poly T.N., Walther B.A., et al. Use of mobile phone app interventions to promote weight loss: meta-analysis. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2020;8 doi: 10.2196/17039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Metzendorf M.-I., Wieland L.S., Richter B. Mobile health (m-health) smartphone interventions for adolescents and adults with overweight or obesity. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2024 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013591.pub2. Epub ahead of print 20 February 2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang J.-W., Zhu Z., Shuling Z., et al. Effectiveness of mHealth app–based interventions for increasing physical activity and improving physical fitness in children and adolescents: systematic review and meta-analysis. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2024;12 doi: 10.2196/51478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhai S., Chu F., Tan M., et al. Digital health interventions to support family caregivers: an updated systematic review. DIGITAL HEALTH. 2023;9 doi: 10.1177/20552076231171967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wąsacz M., Sarzyńska I., Błajda J., et al. The impact of digital technologies in shaping weight loss motivation among children and adolescents. Children. 2025;12:685. doi: 10.3390/children12060685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Partridge S.R., Knight A., Todd A., et al. Addressing disparities: a systematic review of digital health equity for adolescent obesity prevention and management interventions. Obes Rev. 2024;25 doi: 10.1111/obr.13821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Talens C., Da Quinta N., Adebayo F.A., et al. Mobile- and web-based interventions for promoting healthy diets, preventing obesity, and improving health behaviours in children and adolescents: systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Med Internet Res. 2025;27 doi: 10.2196/60602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.East P., Delker E., Blanco E., et al. Home and family environment related to development of obesity: a 21-year longitudinal study. Child Obes. 2019;15:156–166. doi: 10.1089/chi.2018.0222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aleid A.M., Sabi N.M., Alharbi G.S., et al. The impact of parental involvement in the prevention and management of obesity in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Children. 2024;11:739. doi: 10.3390/children11060739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rose T., Barker M., Maria Jacob C., et al. A systematic review of digital interventions for improving the diet and physical activity behaviours of adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2017;61:669–677. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alghamdi A.S., Bitar H.H. The positive impact of gamification in imparting nutritional knowledge and combating childhood obesity: a systematic review on the recent solutions. Digital Health. 2023;9 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prowse R., Carsley S. Digital interventions to promote healthy eating in children: umbrella review. JMIR Pediatr Parent. 2021;4 doi: 10.2196/30160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Melo G.L.R., Santo R.E., Mas Clavel E., et al. Digital dietary interventions for healthy adolescents: a systematic review of behaviours change techniques, engagement strategies, and adherence. Clin Nutr. 2025;45:176–192. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2025.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Partridge S.R., Raeside R., Singleton A., et al. Effectiveness of text message interventions for weight management in adolescents: systematic review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2020;8 doi: 10.2196/15849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suleiman-Martos N., García-Lara R.A., Martos-Cabrera M.B., et al. Gamification for the improvement of diet, nutritional habits, and body composition in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients. 2021;13:2478. doi: 10.3390/nu13072478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koorts H., Salmon J., Timperio A., et al. Translatability of a wearable technology intervention to increase adolescent physical activity: mixed methods implementation evaluation. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22 doi: 10.2196/13573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen X., Wang F., Zhang H., et al. Effectiveness of wearable activity trackers on physical activity among adolescents in school-based settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2025;25:1050. doi: 10.1186/s12889-025-22170-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Caillaud C., Ledger S., Diaz C., et al. iEngage: a digital health education program designed to enhance physical activity in young adolescents. PLoS One. 2022;17 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0274644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chimatapu S.N., Mittelman S.D., Habib M., et al. Wearable devices beyond activity trackers in youth with obesity: summary of options. Child Obes. 2024;20:208–218. doi: 10.1089/chi.2023.0005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang W., Cheng J., Song W., et al. The effectiveness of wearable devices as physical activity interventions for preventing and treating obesity in children and adolescents: systematic review and meta-analysis. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2022;10 doi: 10.2196/32435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Creaser A.V., Clemes S.A., Bingham D.D., et al. Applying the COM-B model to understand wearable activity tracker use in children and adolescents. J Public Health. 2023;31:2103–2114. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Staiano A.E., Marker A.M., Beyl R.A., et al. A randomized controlled trial of dance exergaming for exercise training in overweight and obese adolescent girls. Pediatr Obes. 2017;12:120–128. doi: 10.1111/ijpo.12117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Coknaz D., Mirzeoglu A.D., Atasoy H.I., et al. A digital movement in the world of inactive children: favourable outcomes of playing active video games in a pilot randomized trial. Eur J Pediatr. 2019;178:1567–1576. doi: 10.1007/s00431-019-03457-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Comeras-Chueca C., Villalba-Heredia L., Perez-Lasierra J.L., et al. Active video games improve muscular fitness and motor skills in children with overweight or obesity. IJERPH. 2022;19:2642. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19052642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Froome H.M., Townson C., Rhodes S., et al. The effectiveness of the Foodbot factory mobile serious game on increasing nutrition knowledge in children. Nutrients. 2020;12:3413. doi: 10.3390/nu12113413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang J., Baranowski T., Lau P.W.C., et al. Acceptability and applicability of an American health videogame with story for childhood obesity prevention among Hong Kong Chinese children. Game Health J. 2015;4:513–519. doi: 10.1089/g4h.2015.0029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gkintoni E., Vantaraki F., Skoulidi C., et al. Promoting physical and mental health among children and adolescents via gamification-A conceptual systematic review. Behav Sci. 2024;14:102. doi: 10.3390/bs14020102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Foley L., Jiang Y., Ni Mhurchu C., et al. The effect of active video games by ethnicity, sex and fitness: subgroup analysis from a randomised controlled trial. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Activ. 2014;11:46. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-11-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marsigliante S., My G., Mazzotta G., et al. The effects of exergames on physical fitness, body composition and enjoyment in children: a six-month intervention study. Children. 2024;11:1172. doi: 10.3390/children11101172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Del Río N.G., González-González C.S., Martín-González R., et al. Effects of a gamified educational program in the nutrition of children with obesity. J Med Syst. 2019;43:198. doi: 10.1007/s10916-019-1293-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Caon M., Prinelli F., Angelini L., et al. PEGASO e-diary: user engagement and dietary behaviours change of a mobile food record for adolescents. Front Nutr. 2022;9 doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.727480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jelalian E., Hart C.N., Mehlenbeck R.S., et al. Predictors of attrition and weight loss in an adolescent weight control program. Obesity. 2008;16:1318–1323. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Skelton J.A., Beech B.M. Attrition in paediatric weight management: a review of the literature and new directions. Obes Rev. 2011;12:e273–e281. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00803.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bean M.K., Caccavale L.J., Adams E.L., et al. Parent involvement in adolescent obesity treatment: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2020;146 doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-3315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McMullan M., Millar R., Woodside J.V. A systematic review to assess the effectiveness of technology-based interventions to address obesity in children. BMC Pediatr. 2020;20:242. doi: 10.1186/s12887-020-02081-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Valeriani F., Protano C., Marotta D., et al. Exergames in childhood obesity treatment: a systematic review. IJERPH. 2021;18:4938. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18094938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hagman E., Lindberg L., Putri R.R., et al. Long-term results of a digital treatment tool as an add-on to pediatric obesity lifestyle treatment: a 3-year pragmatic clinical trial. Int J Obes. 2025;49:973–976. doi: 10.1038/s41366-025-01738-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Christison A., Khan H.A. Exergaming for health: a community-based pediatric weight management program using active video gaming. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2012;51:382–388. doi: 10.1177/0009922811429480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Trost S.G., Sundal D., Foster G.D., et al. Effects of a pediatric weight management program with and without active video games: a randomized trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168:407. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.3436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.WHO guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK566046/

- 53.Armstrong S., Mendelsohn A., Bennett G., et al. Texting motivational interviewing: a randomized controlled trial of motivational interviewing text messages designed to augment childhood obesity treatment. Child Obes. 2018;14:4–10. doi: 10.1089/chi.2017.0089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Norman J., Furber S., Bauman A., et al. The feasibility, acceptability and potential efficacy of a parental text message and social media program on children's vegetable consumption and movement behaviours: a pilot randomised controlled trial. Health Promot J Aust. 2024;35:1087–1097. doi: 10.1002/hpja.839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fidjeland T.G., Øen K.G. Parents' experiences using digital health technologies in paediatric overweight and obesity support: an integrative review. IJERPH. 2022;20:410. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20010410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chai L.K., Collins C.E., May C., et al. Fidelity and acceptability of a family-focused technology-based telehealth nutrition intervention for child weight management. J Telemed Telecare. 2021;27:98–109. doi: 10.1177/1357633X19864819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhu D., Dordevic A.L., Gibson S., et al. The effectiveness of a 10-week family-focused e-Health healthy lifestyle program for school-aged children with overweight or obesity: a randomised control trial. BMC Public Health. 2025;25:59. doi: 10.1186/s12889-024-21120-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kahana R., Kremer S., Dekel Dahari M., et al. The effect of incorporating an exergame application in a multidisciplinary weight management program on physical activity and fitness indices in children with overweight and obesity. Children. 2021;9:18. doi: 10.3390/children9010018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Taveras E.M., Marshall R., Sharifi M., et al. Comparative effectiveness of clinical-community childhood obesity interventions: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171 doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.1325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ahmad N., Shariff Z.M., Mukhtar F., et al. Family-based intervention using face-to-face sessions and social media to improve Malay primary school children's adiposity: a randomized controlled field trial of the Malaysian REDUCE programme. Nutr J. 2018;17:74. doi: 10.1186/s12937-018-0379-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Croker H., Viner R.M., Nicholls D., et al. Family-based behavioral treatment of childhood obesity in a UK National Health Service setting: randomized controlled trial. Int J Obes. 2012;36:16–26. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2011.182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hughes A.R., Stewart L., Chapple J., et al. Randomized, controlled trial of a best-practice individualized behavioral program for treatment of childhood overweight: scottish Childhood Overweight Treatment Trial (SCOTT) Pediatrics. 2008;121:e539–e546. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liu Z., Gao P., Gao A.-Y., et al. Effectiveness of a multifaceted intervention for prevention of obesity in primary school children in China: a cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2022;176 doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.4375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hagman E., Johansson L., Kollin C., et al. Effect of an interactive mobile health support system and daily weight measurements for pediatric obesity treatment, a 1-year pragmatical clinical trial. Int J Obes. 2022;46:1527–1533. doi: 10.1038/s41366-022-01146-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hagman E., Lindberg L., Putri R.R., et al. Long-term results of a digital treatment tool as an add-on to pediatric obesity lifestyle treatment: a 3-year pragmatic clinical trial. Int J Obes. 2025;49:973–976. doi: 10.1038/s41366-025-01738-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Umano G.R., Masino M., Cirillo G., et al. Effectiveness of smartphone app for the treatment of pediatric obesity: a randomized controlled trial. Children. 2024;11:1178. doi: 10.3390/children11101178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Roth L., Ordnung M., Forkmann K., et al. A randomized-controlled trial to evaluate the app-based multimodal weight loss program zanadio for patients with obesity. Obesity. 2023;31:1300–1310. doi: 10.1002/oby.23744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Amson A., Bagnato M., Remedios L., et al. Beyond the screen: exploring the dynamics of social media influencers, digital food marketing, and gendered influences on adolescent diets. PLOS Digit Health. 2025;4 doi: 10.1371/journal.pdig.0000729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lafontaine J., Hanson I., Wild C. The impact of the social media industry as a commercial determinant of health on the digital food environment for children and adolescents: a scoping review. BMJ Glob Health. 2025;10 doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2023-014667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Benítez-Andrades J.A., Arias N., García-Ordás M.T., et al. Feasibility of social-network-based eHealth intervention on the improvement of healthy habits among children. Sensors (Basel) 2020;20:1404. doi: 10.3390/s20051404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Prybutok V., Prybutok G., Yogarajah J. Social media influences on dietary awareness in children. Healthcare (Basel) 2024;12:1966. doi: 10.3390/healthcare12191966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Théodore F.L., López-Santiago M., Cruz-Casarrubias C., et al. Digital marketing of products with poor nutritional quality: a major threat for children and adolescents. Public Health. 2021;198:263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2021.07.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.van der Bend D.L.M., Jakstas T., van Kleef E., et al. Adolescents' exposure to and evaluation of food promotions on social media: a multi-method approach. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Activ. 2022;19:74. doi: 10.1186/s12966-022-01310-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Winzer E., Naderer B., Klein S., et al. Promotion of food and beverages by German-speaking influencers popular with adolescents on TikTok, YouTube and Instagram. Int J Environ Res Publ Health. 2022;19 doi: 10.3390/ijerph191710911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Foubister C., Jago R., Sharp S.J., et al. Time spent on social media use and BMI z-score: a cross-sectional explanatory pathway analysis of 10798 14-year-old boys and girls. Pediatr Obes. 2023;18 doi: 10.1111/ijpo.13017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gu Y., Coffino J., Boswell R., et al. Associations between state-level obesity rates, engagement with food brands on social media, and hashtag usage. Int J Environ Res Publ Health. 2021;18 doi: 10.3390/ijerph182312785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Coates A.E., Hardman C.A., Halford J.C.G., et al. ‘It's just addictive people that make addictive videos': children's understanding of and attitudes towards influencer marketing of food and beverages by YouTube video bloggers. Int J Environ Res Publ Health. 2020;17:449. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17020449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Naderer B., Wakolbinger M., Haider S., et al. Influencing children: food cues in YouTube content from child and youth influencers. BMC Public Health. 2024;24:3340. doi: 10.1186/s12889-024-20870-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Potvin Kent M., Pauzé E., Roy E.-A., et al. Children and adolescents' exposure to food and beverage marketing in social media apps. Pediatr Obes. 2019;14 doi: 10.1111/ijpo.12508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zeng M., Grgurevic J., Diyab R., et al. #WhatIEatinaDay: the quality, accuracy, and engagement of nutrition content on TikTok. Nutrients. 2025;17:781. doi: 10.3390/nu17050781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jebeile H., Partridge S.R., Gow M.L., et al. Adolescent exposure to weight loss imagery on Instagram: a content analysis of ‘top’ images. Child Obes. 2021;17:241–248. doi: 10.1089/chi.2020.0351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Alghalyini B. Applications of artificial intelligence in the management of childhood obesity. J Fam Med Prim Care. 2023 Nov;12(11):2558–2564. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_469_23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Jeong J.H., Lee I.G., Kim S.K., Kam T.E., Lee S.W., Lee E. DeepHealthNet: adolescent obesity prediction system based on a deep learning framework. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform. 2024 Feb 5 doi: 10.1109/JBHI.2024.3356580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wang Q., Yang M., Pang B., Xue M., Zhang Y., Zhang Z., Niu W. Predicting risk of overweight or obesity in Chinese preschool-aged children using artificial intelligence techniques. Endocrine. 2022 Jun;77(1):63–72. doi: 10.1007/s12020-022-03072-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Choi Y., Lee K., Seol E.G., Kim J.Y., Lee E.B., Chae H.W., Ko T., Song K. Development and validation of a machine learning model for predicting pediatric metabolic syndrome using anthropometric and bioelectrical impedance parameters. Int J Obes. 2025 Jun;49(6):1159–1165. doi: 10.1038/s41366-025-01761-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Šket R., Slapnik B., Kotnik P., Črepinšek K., Čugalj Kern B., Tesovnik T., Jenko Bizjan B., Vrhovšek B., Remec Ž.I., Debeljak M., Battelino T., Kovač J. Integrating genetic insights, technological advancements, screening, and personalized pharmacological interventions in childhood obesity. Adv Ther. 2025 Jan;42(1):72–93. doi: 10.1007/s12325-024-03057-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bays H.E., Fitch A., Cuda S., Gonsahn-Bollie S., Rickey E., Hablutzel J., Coy R., Censani M. Artificial intelligence and obesity management: an obesity medicine association (OMA) clinical practice statement (CPS) 2023. Obes Pillars. 2023 Apr 20;6 doi: 10.1016/j.obpill.2023.100065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the paper are included in the review article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.