Highlights

-

•

The sitravatinib-venetoclax combination demonstrates potent synergistic effects in FLT3-ITD mutated AML, significantly reducing cell viability, inducing apoptosis, suppressing leukemia progression, and prolonging survival in preclinical models.

-

•

The combination therapy achieves its therapeutic effects through concurrent suppression of AKT/ERK signaling pathways and downregulation of key anti-apoptotic proteins (MCL-1 and BCL-xL).

-

•

These findings support the translation of the combination of sitavatinib and venetoclax from preclinical research to clinical use for treating acute myeloid leukemia patients with FLT3-ITD mutation.

Keywords: FLT3-ITD mutation, BCL-2 inhibitor, Venetoclax, Sitravatinib, Synergistic effect

Abstract

We have previously identified sitravatinib as a potent inhibitor of FLT3, capable of overcoming resistance to gilteritinib in the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia (AML). The combination of venetoclax and FLT3 inhibitors gilteritinib and quizartinib has shown promising results in reducing leukemia burden and improving survival in pre-clinical studies and clinical trials of AML with FLT3 mutation. In this study, we aimed to investigate the therapeutic effect of treating AML with sitravatinib combined with venetoclax. Our findings indicated that the combination of sitravatinib and venetoclax significantly decreased cell viability and increased cell apoptosis in AML cell lines harboring FLT3 mutation, more so than either treatment alone. These two agents exerted strong synergistic effects in FLT3-ITD AML cell lines and patient bone marrow cells in vitro. The activation of MAPK/ERK signaling are common causes that weaken the efficacy of FLT3 inhibitors, while the upregulation of anti-apoptotic proteins including BCL-xL and MCL-1 leads to venetoclax resistance. Our data demonstrated that sitravatinib plus venetoclax further suppressed the phosphorylation of AKT and ERK as well as downregulated MCL-1 and BCL-xL, which mechanically explain the synergistic effect. Finally, we tested the potential application of sitravatinib plus venetoclax in vivo using patient-derived xenografts, and found that the combined therapy was significantly more effective in inhibiting leukemia cell expansion, reducing infiltration in the spleen, and prolonging survival time compared to a single administration. Our study demonstrates the potential use of sitravatinib plus venetoclax as an alternative therapeutic strategy to treat AML patients with FLT3-ITD mutation.

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a malignant tumor characterized by the uncontrolled growth of abnormal or poorly differentiated cells in the hematopoietic system. AML exhibits genetic heterogeneity and clonal evolution [1]. The most prevalent mutations in AML are activating mutations in the FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3) gene, specifically internal tandem duplication within the juxta-membrane domain (FLT3-ITD) and point mutations in the tyrosine kinase domain (FLT3-TKD). FLT3 mutations are present in around 30 %−35 % of AML cases and AML patients with FLT3-ITD mutations generally have a poor prognosis [[2], [3], [4], [5]]. Therefore, targeting FLT3 activity is a promising therapeutic approach for AML with FLT3 mutations, but the currently approved FLT3 tyrosine kinase inhibitors used as monotherapy have limited effectiveness. A subset of patients who achieve complete remission (CR) develop drug resistance and ultimately relapse within a few weeks to months. The drug resistance occurs due to the emergence of FLT3 secondary mutations or the activation of alternative signaling pathways which renders the cells independent of FLT3 signaling [6]. Combining agents targeting other pathways with FLT3 inhibitors may improve clinical outcomes and extend survival.

The anti-apoptotic protein B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2) is often overexpressed in AML, leading to poor prognosis and drug resistance [7,8]. Venetoclax (ABT-199) is a highly selective inhibitor of BCL-2 protein and is used in combination with hypomethylating agents (HMA) as the standard therapy for newly diagnosed AML patients who cannot undergo intensive chemotherapy [9,10]. However, despite the initial remission achieved by venetoclax-azacitidine, the majority of patients eventually relapse, making it urgent to identify new combination drug regimens [8,9,11]. Recent studies have demonstrated that in preclinical models of FLT3-ITD mutant AML, the inhibition of BCL-2 by venetoclax synergistically enhances the anti-leukemia activity of FLT3 inhibitors [12,13]. This suggests that targeting both BCL-2 and FLT3 simultaneously could be a promising therapeutic strategy for AML.

Sitravatinib (MGCD516) is a multi-kinase inhibitor that has been extensively studied. Our recent investigations have identified sitravatinib as a FLT3 inhibitor, which exerts potent anti-leukemia effects by promoting the dephosphorylation of FLT3 and downstream signaling molecules such as STAT5, AKT, and ERK. Furthermore, sitravatinib demonstrated activity against clinically relevant FLT3 inhibitor resistance caused by the F691L mutation or elevated FL/FGF2 levels [14].

In this study, we showed the highly synergistic therapeutic effect of the FLT3 inhibitor sitravatinib in combination with the BCL-2 inhibitor venetoclax in preclinical models of FLT3-ITD mutated AML. Mechanistically, sitravatinib enhances the efficacy of venetoclax by suppressing the expression of MCL-1. Additionally, the combination of these two drugs resulted in a further reduction in the activity of the MAPK and AKT signaling pathways. Given that venetoclax is already a frontline treatment for AML and sitravatinib has shown good safety profiles in clinical trials of solid tumors, the combined therapy strategy deserves further validation in clinical settings [[15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23]].

Materials and methods

Cell culture

The human cell line MV4–11 was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection and MOLM13 was purchased from DSMZ. BaF3-FLT3-ITD cells were constructed as previously described [14]. The cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 (Gibco) with 10 % fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gemini) and incubated at 37 °C with 5 % CO2. The cells were routinely tested with one-step mycoplasma detection kit (Yeasen) to exclude mycoplasma contamination and limited in 10 passages.

Primary bone marrow (BM) cells with FLT3-ITD were collected from AML patients and mononuclear cells (BMMC) were separated with ficoll (Cytiva) using density gradient centrifugation. The BMMC were cultured in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 20 % FBS. Written informed consent was obtained from the AML patients, and all experiments involving primary samples were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Guangzhou First People's Hospital, School of Medicine, South China University of Technology according to the Declaration of Helsinki. The detail of the patients was showed in supplementary Table 1.

Cell viability assay

Cell viability assays were conducted with CellTiter-Glo® 2.0 (Promega) as previously described [14].

Cell apoptosis assay

MV4–11 and MOLM13 were seeded into 6-well plates at a density of 5 × 10^4 cells per well and treated with vehicle, sitravatinib (TargetMol), venetoclax (TargetMol) or the combination of the two drugs. After 48 h, cells were processed following the instructions in the Annexin V-APC/PI apoptosis detection kit (eBioscience) and were then analyzed using flow cytometry analysis with FACSCelesta (BD Biosciences).

Immunoblotting

Cells exposed to the indicated drugs were lysed with Laemmli 2 × concentrated sample buffer (Sigma-Aldrich), followed by immunoblotting as detailed previously [14]. The following antibodies were used: anti-Phospho-FLT3 (Tyr589/591) (#3464, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-FLT3/CD135 (#ab245116, Abcam), anti-Phospho-STAT5 (Tyr694) (#9359, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-STAT5 (#A5029, ABclonal), anti-Phospho-AKT (S473) (#AP1208, ABclonal), anti-Pan-AKT (#A18675, ABclonal), anti-Phospho-ERK1/2 (Tr202/Tyr204) (#4370, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-ERK1/2 (#4695, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-Caspase8 (#13423–1-AP, Proteintech), anti-PARP1 (#13371–1-AP, Proteintech), HRP-conjugated Alpha Tubulin (#HRP-66031, Proteintech), anti-MCL1 (#ab28147, Abcam), anti-BCL-2(#ab182858, Abcam), anti-BCL-xL(#ab223547, Abcam).

Animal studies

The animal studies were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee at South China University of Technology. The patient-derived xenografts (PDX) were constructed according to previously established methods [14]. After 14 days from leukemia cell injection, the second generation PDX mice (P1 PDX) were randomly divided into 4 groups and treated with sitravatinib (10 mg/kg/d, dissolved in 5 % DMSO + 30 % PEG300 + 10 % Tween 80 + 55 % water), venetoclax (40 mg/kg/d, dissolved in 10 % DMSO + 30 % PEG300 + 10 % Tween 80 + 50 % water), a combination of both drugs, or vehicle, daily for 21 days. The percentage of human CD45+ cells in the peripheral blood (PB) of mice was measured by flow cytometry 2 days after stopping the treatment. When mice in the vector group showed signs of distress, 3 mice from each group were euthanized, and their bone marrow and spleen were analyzed for the percentage of human CD45+ cells using flow cytometry. The spleens were also weighted and further examined by H&E staining and immunochemistry of human CD45 and human CD34. Throughout the study, the mice were weighed every other day. The following antibodies were used: anti-human CD45 for flow cytometry (# 982304, biolegend), anti-human CD45 for immunochemistry (GB113885, Servicebio), anti-human CD34 for immunochemistry (GB151693, Servicebio).

Statistical analysis and softwares

The combination index (CI) values of the drugs were calculated using the Calcusyn software, and the Highest Single Agent (HSA) score was determined on the https://synergyfinder.org/ website. GraphPad Prism 8.0 software was used to perform statistical analyses. IC50 values were calculated by nonlinear best-fit regression analysis. Kaplan–Meier survival curves were compared using the log-rank test. Error bars represent the mean plus or minus standard error of the mean. P values were analyzed utilizing the paired or unpaired 2-tailed Student’s t-test (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001). The statistical significance level was set at P < 0.05.

Results

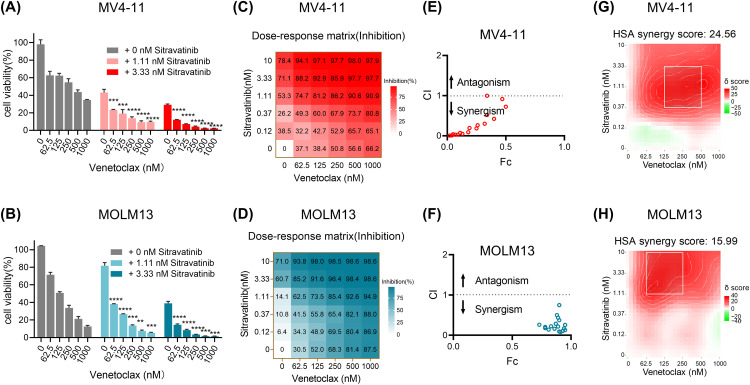

Sitravatinib and venetoclax synergistically inhibit the proliferation of MOLM13 and MV4–11 harboring FLT3-ITD mutation

The concurrent inhibition of FLT3 and BCL-2 has shown encouraging synergistic outcomes in clinical settings. Our research has revealed that sitravatinib is a FLT3 inhibitor and exhibits superior therapeutic effects compared to clinically approved drugs, gilteritinib and quizartinib, in pre-clinical models. Therefore, we aimed to explore the combined efficacy of sitravatinib with the approved BCL-2 inhibitor, venetoclax. To determine the optimal concentrations for the combination therapy, we initially conducted growth inhibitory assays on AML cell lines with FLT3-ITD mutation using each drug separately. The dose-response curves indicated that the IC50 values of sitravatinib in MV4–11 cells and MOLM13 cells ranged between 0.46 nM and 4.12 nM, while the IC50 values of venetoclax in both cell lines fell between 37 nM and 333 nM (Supplementary Fig. 1A, 1B). Consequently, we selected the concentration range of 0–10 nM for sitravatinib and 0–1000 nM for venetoclax for the combination treatment. The combined treatment of sitravatinib and venetoclax resulted in significantly increased inhibition of proliferation compared to when each drug was used alone in MV4–11 and MOLM13 cells (Fig. 1A, 1B, 1C, 1D). To analyze the drug interactions quantitatively, we used Calcusyn software to calculate the combination index (CI) values for different dosage combinations. The CI values for each combination in MV4–11 and MOLM13 cells were lower than 1, indicating synergistic effects (Fig. 1E, 1F). Additionally, we calculated synergy scores using the HSA model to identify the most effective concentration ranges for the synergistic effect. In MV4–11 cells, the HSA score was 24.562 while greater than 10 indicating synergistic interaction, and the most effective combination range was 0.37–3.33 nM for sitravatinib and 125–500 nM for venetoclax (Fig. 1G). In MOLM13 cells, the HAS score was 15.99, with the most effective combination range being 1.11–10 nM for sitravatinib and 62.5–250 nM for venetoclax (Fig. 1H).

Fig. 1.

The synergistic effect of sitravatinib and venetoclax on the proliferation of MV4–11 and MOLM13 cells. FLT3-ITD AML cell lines MV4–11 and MOLM13 cells were treated with venetoclax with or without sitravatinib at the indicated concentrations for 48 h. Cell viabilities were detected by CellTiter-Glo assay (A-B) and the mean proliferation inhibitory rates were shown by the heatmaps (C-D). **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. (E-F) The combination indexs (CI) of the two drugs at a range of concentrations were calculated by Calcusyn software; CI < 1 synergistic effect, CI = 1 additive effect, CI > 1, antagonism effect. (G-H) The Highest Single Agent (HSA) analysis was used to determine the best regions of synergy, which was dashed by the white line; synergy score > 10, synergistic effect.

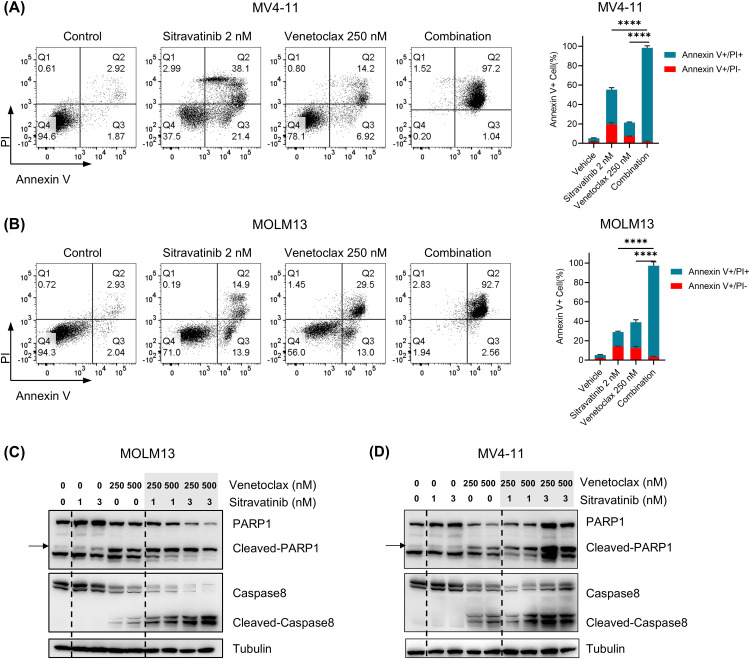

Sitravatinib and venetoclax synergistically induce apoptosis in FLT3-ITD cells

We performed apoptosis assays to investigate whether the combination of sitravatinib and venetoclax could further induce the apoptosis of FLT3-ITD cells compared to monotherapy. In the experiments, we treated MV4–11 and MOLM13 cells with 2 nM Sitravatinib, 250 nM venetoclax or the combination for 48 h. In MV4–11 cells, the percentage of apoptotic cells (sum of AnnexinV+/PI- and AnnexinV+/PI+ cells) in the combination group (98.42 % ± 1.00 %) was much higher than the sitravatinib (55.30 % ± 2.25 %) and venetoclax (21.44 % ± 0.29 %) groups (Fig. 2A). Similarly, in MOLM13 cells, the proportion of apoptotic cells in the combination group (96.29 % ± 1.64 %) was significantly higher compared to the sitravatinib (28.97 % ± 0.17 %) and venetoclax (39.07 % ± 2.32 %) groups (Fig. 2B). Simultaneously, we treated MV4–11 and MOLM13 cells with 1 nM and 3 nM sitravatinib or 250 nM and 500 nM venetoclax for 48 h. The results showed that the combination group significantly increased the activation of PARP1 and caspase 8 cleavage compared to the single drug group (Fig. 2C, 2D). In summary, the combination therapy of sitravatinib and venetoclax synergistically promoted cell apoptosis of FLT3-ITD cell lines.

Fig. 2.

The two drugs effectively increased the apoptotic proportion of FLT3-ITD cells. MV4–11 and MOLM13 cells were incubated with sitravatinib (2 nM), venetoclax (250 nM) or the combination therapy for 48 h. (A-B) Left: The representative flow cytometry graphs of the early apoptosis (Annexin V+ PI−) and late apoptosis (Annexin V− PI−) cells. Right: Bar plots of the cell apoptosis stained by Annexin V/PI assays. (C-D) Cells were lysed and the expression of PARP1, cleaved-PARP1, caspase 8 and cleaved-caspase8 was assessed by immunoblotting.

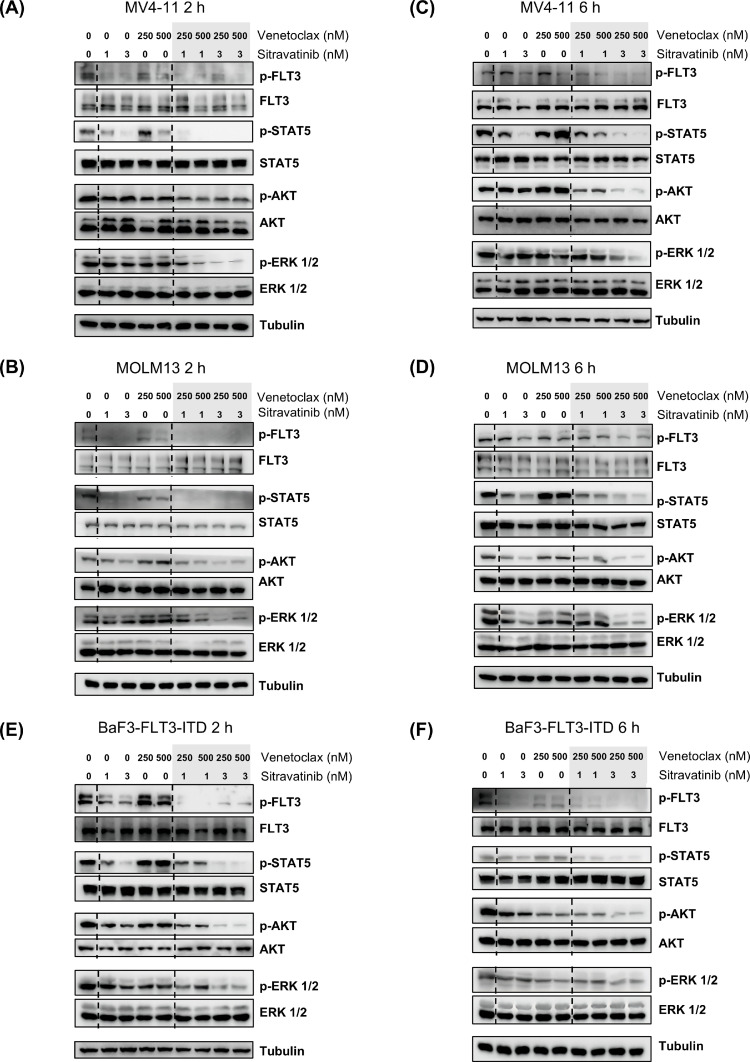

The combination of sitravatinib and venetoclax more profoundly inhibits the activation of FLT3 downstream pathway

FLT3-ITD mutation drives the expansion of leukemia cells through continuously activating the downstream pathways including JAK/STAT5, PI3K/AKT and RAS/MAPK. In consistent with our previous studies, sitravatinib dephosphorylated FLT3 and its downstream targets when incubated with MV4–11 and MOLM13 cells. At the low concentrations (1 nM and 3 nM), single-agent sitravatinib effectively inhibits the phosphorylation levels of FLT3 and STAT5 in MOLM13 and MV4–11 cells but has weaker inhibitory effects on the activation of the MAPK and AKT signaling pathways. Little changes of FLT3 activity and its downstream pathways were observed in both cell lines after 2 h treatment of venetoclax. Compared to single-agent treatment, the exposure of both drugs in MV4–11 and MOLM13 cells by 2 h result in a more effective suppression on the activity of FLT3 signaling pathways, especially AKT and ERK (Fig. 3A, B). After 6 h, the combination therapy also further downregulated phosphorylated FLT3, STAT5, ERK and AKT compared to monotherapy (Fig. 3C, 3D). Furthermore, we confirmed the effect of the combined treatment on oncogenetic FLT3 signaling in BaF3-FLT3-ITD cells, which rely on mutant FLT3 to survive. The data showed that sitravatinib exerted prominent activity against FLT3 and its downstream molecules both at 2 h and 6 h, while venetoclax exerted weaker activity against the activation of FLT3-ITD. A greater reduction of phosphorylated FLT3, STAT5, ERK and AKT was observed in cells co-treated with sitravatinib and venetoclax at the indicated concentrations (Fig. 3E, F). These results indicated that sitravatinib and venetoclax synergistically hinder FLT3-ITD AML cell growth partly through a more effective inhibition of the FLT3 signaling pathway.

Fig. 3.

Sitravatinib and venetoclax synergistically inhibited the activation of FLT3 signaling pathway. Human AML cell lines MV4–11 (A, C) and MOLM13 (B, D), BaF3 cells that depended on FLT3-ITD to survive (E-F) were treated with sitravatinib (1 nM, 3 nM), venetoclax (250 nM, 500 nM) or the combination of the two drugs for 2 h or 6 h. Western blot was used to evaluate the expression of FLT3, Phospho-FLT3 (Tyr589/591) (p-FLT3), STAT5, p-STAT5 (Tyr694), AKT, p-AKT (S473), ERK, p-ERK1/2 (Tr202/Tyr204).

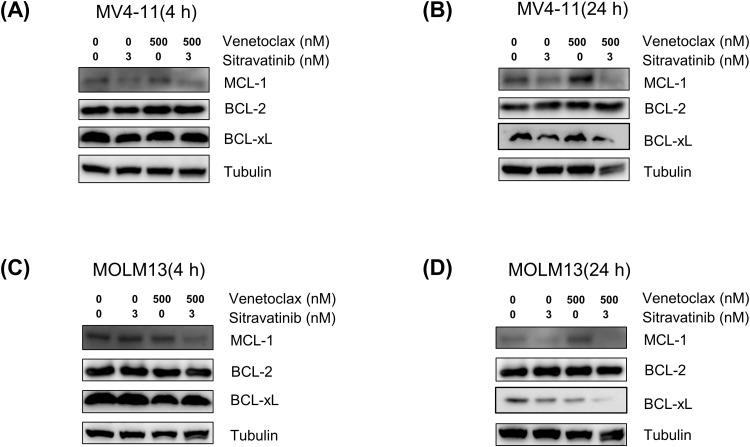

Sitravatinib synergizes with venetoclax in FLT3-ITD cells by suppressing MCL-1 and BCL-xL

The expression of MCL-1, a protein known for its anti-apoptotic properties, was found to increase after treatment with venetoclax, leading to reduced therapeutic efficacy and resistance. Current studies have indicated that FLT3 inhibitors such as quizartinib and gilteritinib can enhance the activity of venetoclax by decreasing MCL-1 levels [13]. Thus we investigated whether sitravatinib and venetoclax exerted synergistic effects by reducing MCL-1 expression. In MV4–11 cells, the immunoblotting analysis revealed that BCL-2 expression remained stable following treatment with sitravatinib or venetoclax for 4 h or 24 h, whereas MCL-1 expression notably increased after 24 h of venetoclax treatment. Sitravatinib reduced the MCL-1 levels and the combination treatment also downregulated MCL-1 expression by 4 h and 24 h. Additionally, our findings indicated that the combination of the two drugs also led to a reduction in BCL-xL, another protein involved in apoptosis, compared to no treatment or single agent treatment by 24 h (Fig. 4A, 4B). In MOLM13 cells, sitravatinib did not alter MCL-1 levels for 4 h but significantly lowered MCL-1 expression for 24 h. When compared to treatment with a single agent, the combination of sitravatinib and venetoclax effectively downregulated MCL-1 by 4 h and 24 h and also lowered BCL-xL expression by 24 h (Fig. 4C, 4D). These results indicated that sitravatinib and venetoclax acted synergistically in part by modulating the apoptotic pathway through the suppression of MCL-1 and BCL-xL.

Fig. 4.

Sitravatinib combined with venetoclax reduced the MCL-1 and BCL-xL levels. Western blot analysis of MCL-1, BCL-2, BCL-xL in MV4–11 (A-B) and MOLM13 (C-D) cells treated with a single agent (sitravatinib 3 nM, venetoclax 500 nM) or the combination drugs for 4 h or 24 h.

The co-treatment of sitravatinib and venetoclax synergistically inhibit the cell viabilities of primary AML samples harboring FLT3-ITD mutation

We further investigated the effects of the combination treatment on the AML patient samples with FLT3-ITD. We firstly performed growth inhibition assays to assess the effects of each drug individually on primary cells. Both sitravatinib and venetoclax demonstrated the ability to reduce the viability of primary leukemia cells, although the sensitivity to the drugs varied among different patients (Supplementary Figure 2A-D). Based on the dose-response curves of each drug, we selected customized drug concentrations to administer as a combination treatment for each sample. The combination treatment resulted in a significant decrease in cell viability compared to single-agent therapy (Fig. 5A-D). The heatmaps displayed the combined effect of sitravatinib and venetoclax on the cell proliferation inhibition rate of primary samples more intuitively (Fig. 5E-H). We calculated the CI values of the two drugs in each sample using Calcusyn. The CI scores of each combination dose were all <1, indicating obvious synergy between sitravatinib and venetoclax in the four patient samples (Fig. 5I-L). Additionally, we employed the HSA analysis to determine regions of synergy in the primary cells and found that the HSA scores of the two drugs ranged from 13.34 to 26.80 (Fig. 5M-P). In summary, our results suggest that combining sitravatinib with venetoclax is an effective treatment for primary AML cells with FLT3-ITD.

Fig. 5.

The combination treatment synergistically inhibited cell viability of FLT3-ITD AML primary cells. Primary AML samples with FLT3-ITD were treated with the indicated doses of venetoclax and sitravatinib for 48 h. (A-D) Cell viabilities were detected by CellTiter-Glo assay. ns P > 0.05, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.(E-H) The heatmaps showed the mean proliferation inhibitory rates of primary cells. (I-L) The combination index (CI) of the two drugs under a series of concentration combinations calculated by Calcusyn software; CI < 1 synergistic effect, CI = 1 additive effect, CI > 1, antagonism effect. (M-P) The Highest Single Agent (HSA) scores of the two drugs in the four samples with the best regions of synergy were dashed by the white line; synergy score > 10, synergistic effect.

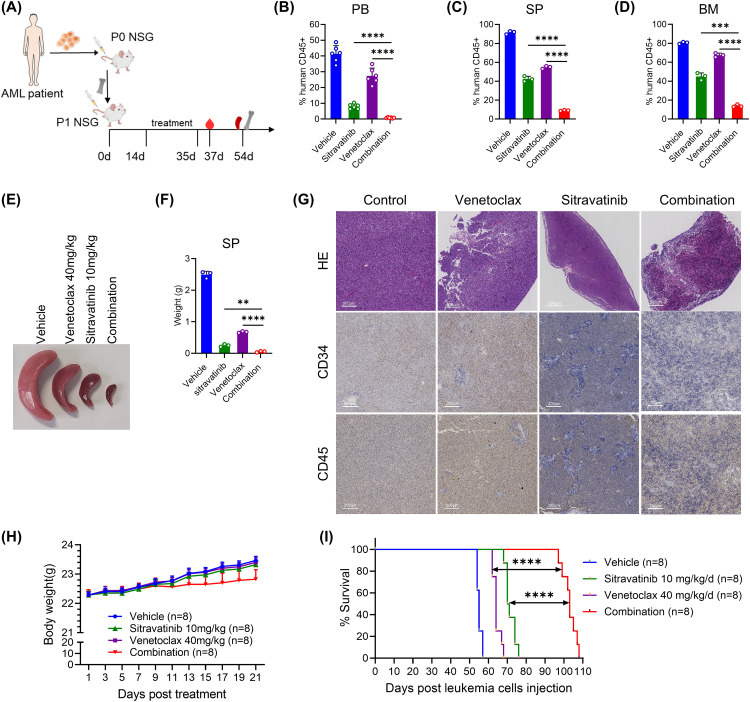

The combination of sitravatinib and venetoclax effectively eliminates FLT3-ITD AML cells in AML PDX mice

To further validate the in vivo anti-tumor effect of the sitravatinib and venetoclax combination, we constructed a mouse model using patient-derived samples with FLT3-ITD mutations. The mice were randomly treated with control, sitravatinib (10 mg/kg/d), venetoclax (40 mg/kg/d), or the combination of sitravatinib (10 mg/kg/d) and venetoclax (40 mg/kg/d) for 21 days (Fig. 6A). Two days after the cessation of treatment, we observed a significant accumulation of leukemia cells in the blood samples of the mice in the vehicle group. There was a reduction in leukemia burden in PB of mice treated with venetoclax and a more noticeable reduction in PB of mice treated with sitravatinib while almost no leukemia cells were found in mice treated with the drug combination (Fig. 6B). Furthermore, 19 days after drug cessation, three mice from each group were randomly euthanized to detect the proportion of human CD45+ cells in their SP and BM. The results showed that the tumor burden was the highest in the vehicle group of mice, and the lowest in the combined treatment group (Fig. 6C, D). The size and weight of the spleens of the mice in the combination treatment group were also significantly smaller than those of the other three groups (Fig. 6E, F). In the combination group, the H&E staining showed a more normal structure of spleens and the immunohistochemistry showed less infiltration of leukemia cells (CD45+, CD34+), compared with vehicle and single agent group (Fig. 6G). The weight of the mice did not differ between groups during drug administration, suggesting good safety of the drug combinations (Fig. 6H). Notably, the combination of the two drugs extended the median survival of mice from 55 days in the vehicle group, 64 days in the venetoclax group and 70.5 days in the sitravatinib group to 103 days (Fig. 6I). Overall, the data supports the idea that sitravatinib combined with venetoclax can be effectively used to treat FLT3-ITD AML.

Fig. 6.

Sitravatinib combined with venetoclax exerted significant efficacy in FLT3-ITD PDX mice. (A) Schematic flow of animal experiments in patient-derived xenografts (PDX) with FLT3-ITD. (B) Two days after drug discontinuation, 6 mice in each group (vehicle, sitravatinib 10 mg/kg/d, venetoclax 40 mg/kg/d or combined therapy) were randomly selected to collect peripheral blood (PB) and the percentage of human CD45+ cells in PB were detected by flow cytometry. (C-G) 19 days after drug discontinuation, 3 mice of each group were randomly euthanized and the percentage of human CD45+ cells in spleen (SP) (C) and bone marrow (BM) (D) were detected by flow cytometry. The representative image of the SP size in each group was shown (E) and the SPs of the mice were weighted (F). One SP of each group was randomly selected to perform H&E staining and the immunochemistry of human CD45 and CD34 (G). (H) The body weight of PDX mice during drug treatment. (I) The Kaplan–Meier survival plot of the PDX mice treated with veheicle, sitravatinib 10 mg/kg/d, venetoclax 40 mg/kg/d or combined therapy. n = 8 for each group. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

Discussion

AML is a heterogeneous disease driven by various cytogenetic abnormalities and gene mutations, which is the most prevalent type of leukemia and has the worst prognosis among hematological malignancies [24]. For many years, the standard treatment for AML was limited to intensive chemotherapy with cytarabine (Cytarabine) and anthracycline (7 + 3) [25]. However, AML is more common in older patients, many of whom are not suited for intensive chemotherapy, leading to unsatisfactory outcomes [26,27].

Recent advancements in understanding the molecular mechanisms of AML have led to the development of small molecule compounds that target genetic abnormalities. This has significantly improved the survival of AML patients and their tolerance to treatment [[28], [29], [30]]. One major breakthrough is the BCL-2 inhibitor venentoclax, which has been approved, in combination with demethylation agents, as a front-line therapy for elderly or unfit AML patients. However, venetoclax alone has limited effectiveness [31,32]. And FLT3 inhibitors targeting the most common genetic mutation in AML have been shown to provide survival benefits for patients with FLT3 mutation as monotherapy, in combination with chemotherapy, or as maintenance therapy after bone marrow transplantation [[33], [34], [35]].

However, relapse or primary resistance is common during target inhibitors treatment and significantly reduced the therapeutic effect. In the phase III clinical trials, only two-third of treated patients responded to venetoclax plus azacitidine and the 2-year overall survival rate was only 37.5 % [31]. Regarding FLT3 inhibitors, there is a clearer understanding of the tyrosine kinase inhibitor resistance. On-target resistance involves secondary mutations in the FLT3 tyrosine kinase domain, while off-target resistance results from aberrant activation of other oncogenetic genes or signaling, leading to AML patients being refractory and experiencing relapse [36,37]. Many efforts have been made to overcome resistance to targeted inhibitors. Developing new inhibitors has proven to be an effective strategy to overcome drug resistance. In our previous study, we identified sitavatinib as an excellent FLT3 inhibitor to overcome FLT3-F691L resistance and retained activity against cytokine-induced resistance [14]. And there are emerging clinical data to validate the safety of sitravatinib in humans [15,18].

Another strategy to improve treatment outcomes and overcome drug resistance is the combination of targeted drugs with different anti-tumor mechanisms to generate a synergistic effect [38]. There has been extensive evidence for the rational of combining FLT3 inhibitors including gilteritinib, quizartinib or midostaurin with venetoclax in preclinical studies and clinical trials [13,39,40]. Considering the promising application prospect of sitravatinib for AML patients with FLT3 mutation, we herein tested the efficacy of using sitravatinib and venetoclax simultaneously. The data showed that the addition of venetoclax significantly reduced cell viabilities and promoted cell apoptosis in cell lines with FLT3-ITD mutation compared with sitravatinib monotherapy. Consistently, the calculation of combination index and HSA synergy scores indicated sitravatinib and venetoclax have an apparent synergistic effect in cell lines and patient primary blasts with FLT3-ITD mutation. The activation of PI3K/AKT and RAS/MAPK signaling were found to mediate venetoclax resistance and render FLT3 inhibitors disabled [[41], [42], [43]]. Our previous study demonstrated that sitravatinib monotherapy could inhibit the rebound of ERK and AKT phosphorylation relative to gilteritinib monotherapy, a phenomenon that might be mechanistically linked to sitravatinib’s capacity as a multi-kinase inhibitor to effectively attenuate bypass signaling pathway activation [14]. In this study, we further found that the combination of sitravatinib and venetoclax apparently lowered the phosphorylation of ERK and AKT, partly explaining the combinational mechanism. MCL-1 and BCL-xL are members of anti-apoptotic protein family like BCL-2. The upregulation of MCL-1 and BCL-xL is a clear reason responsible for venetoclax resistance [44]. Previous studies have revealed that venetoclax combined with gilteritinib or midostaurin could downregulated the expression of MCL-1 and quizartinib plus venetoclax could inhibit MCL-1 as well as BCL-xL [40,45]. Our results demonstrated that co-treatment of sitravatinib and venetoclax could also reduce MCL-1 expression as well as BCL-xL expression. In a recent study, gilteritinib also potentiated venetoclax response through inducing MCL-1 downregulation in FLT3 wild-type AML [12]. We assume that sitravatinib plus venetoclax might also exert synergistic effect in FLT3 wild-type AML.

One advantage of combination therapy is the ability to use lower doses of medication, which helps to reduce toxicity and improve safety. We finally verified the activity of sitravatinib plus venetoclax in a PDX model with FLT3-ITD. The results showed that the combination treatment is capable of effectively eliminating leukemia cells with lower dosage and good safety, supporting the clinical translation of sitravatinib plus venetoclax. Sitravatinib has been found to modulate the function of ABCB1 and ABCG2, which are ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters responsible for removing the drug from cells [46,47]. Recent research has indicated that ABCC1 affects the response of AML cells to venetoclax, and inhibiting ABCC1 enhances the sensitivity to venetoclax [48]. The pharmacologic action of sitravatinib on ABCC1 is uncertain and may also contribute to the synergistic effect, requiring further investigation. In summary, our findings suggest a new approach for the clinical use of sitravatinib and identify a potential partner for venetoclax, which could ultimately enhance the treatment outcomes for AML patients with FLT3 mutation.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Jie Yang: Writing – original draft, Validation, Software, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation. Yvyin Zhang: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Resources, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Qingshan Li: Writing – review & editing, Resources, Funding acquisition, Data curation. Peihong Wang: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Consent for publication

All authors approved to publish the study in this journal.

Availability of data and materials

All data created or analyzed during this study are enrolled in this published article or are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Guangzhou First People's Hospital, School of Medicine, South China University of Technology in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all patients. All mice were bred and handled in an animal facility accredited by the Society for Evaluation and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care at the Animal Center of South China University of Technology. This study complied with all relevant ethical regulations regarding animal research.

Funding

This research was funded by a Guangzhou Health Technology Project (Grant/Award Number 20231A011012 to P. Wang), Guangzhou Municipal Science and Technology Project (Grant/Award Numbers 2024A03J1022 and 2023A04J0616 to P. Wang), Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (Grant/Award Numbers 2214050003863 to Q.Li).

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.tranon.2025.102467.

Contributor Information

Qingshan Li, Email: drliqingshnag@126.com.

Peihong Wang, Email: wangph91@163.com.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Ding L., et al. Clonal evolution in relapsed acute myeloid leukaemia revealed by whole-genome sequencing. Nature. 2012;481(7382):506–510. doi: 10.1038/nature10738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Papaemmanuil E., et al. Genomic classification and prognosis in acute myeloid leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016;374(23):2209–2221. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1516192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tao S., et al. Prognosis and outcome of patients with acute myeloid leukemia based on FLT3‑ITD mutation with or without additional abnormal cytogenetics. Oncol. Lett. 2019;18(6):6766–6774. doi: 10.3892/ol.2019.11051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chevallier P., et al. A new Leukemia prognostic Scoring system for refractory/relapsed adult acute myelogeneous leukaemia patients: a GOELAMS study. Leukemia. 2011;25(6):939–944. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cancer Genome Atlas Research, N. Genomic and epigenomic landscapes of adult de novo acute myeloid leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;368(22):2059–2074. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1301689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daver N., et al. Secondary mutations as mediators of resistance to targeted therapy in leukemia. Blood. 2015;125(21):3236–3245. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-10-605808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pan R., et al. Selective BCL-2 inhibition by ABT-199 causes on-target cell death in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Discov. 2014;4(3):362–375. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lagadinou E.D., et al. BCL-2 inhibition targets oxidative phosphorylation and selectively eradicates quiescent human leukemia stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;12(3):329–341. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DiNardo C.D., et al. Venetoclax combined with decitabine or azacitidine in treatment-naive, elderly patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2019;133(1):7–17. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-08-868752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jonas B.A., Pollyea D.A. How we use venetoclax with hypomethylating agents for the treatment of newly diagnosed patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2019;33(12):2795–2804. doi: 10.1038/s41375-019-0612-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DiNardo C.D., et al. Clinical experience with the BCL 2-inhibitor venetoclax in combination therapy for relapsed and refractory acute myeloid leukemia and related myeloid malignancies. Am. J. Hematol. 2018;93(3):401–407. doi: 10.1002/ajh.25000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Janssen M., et al. Venetoclax synergizes with gilteritinib in FLT3 wild-type high-risk acute myeloid leukemia by suppressing MCL-1. Blood. 2022;140(24):2594–2610. doi: 10.1182/blood.2021014241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ma J., et al. Inhibition of bcl-2 synergistically enhances the antileukemic activity of Midostaurin and Gilteritinib in preclinical models of FLT3-mutated acute myeloid leukemia. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019;25(22):6815–6826. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-0832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang Y., et al. Sitravatinib as a potent FLT3 inhibitor can overcome gilteritinib resistance in acute myeloid leukemia. Biomark. Res. 2023;11(1):8. doi: 10.1186/s40364-022-00447-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karam J.A., et al. Phase II trial of neoadjuvant sitravatinib plus nivolumab in patients undergoing nephrectomy for locally advanced clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Nat. Commun. 2023;14(1):2684. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-38342-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Msaouel P., et al. A phase 1-2 trial of sitravatinib and nivolumab in clear cell renal cell carcinoma following progression on antiangiogenic therapy. Sci. Transl. Med. 2022;14(641):eabm6420. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abm6420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.He K., et al. MRTX-500 phase 2 trial: sitravatinib with Nivolumab in patients with nonsquamous NSCLC progressing on or after checkpoint inhibitor therapy or chemotherapy. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2023;18(7):907–921. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2023.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Borghaei H., et al. SAPPHIRE: phase III study of sitravatinib plus nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2024;35(1):66–76. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2023.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ingham M., et al. A single-arm phase II trial of Sitravatinib in advanced well-differentiated/dedifferentiated liposarcoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2023;29(6):1031–1039. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-22-3351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bauer T., et al. First-in-human phase 1/1b study to evaluate sitravatinib in patients with advanced solid tumors. Invest. New Drugs. 2022;40(5):990–1000. doi: 10.1007/s10637-022-01274-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao J., et al. SAFFRON-103: a phase 1b study of the safety and efficacy of sitravatinib combined with tislelizumab in patients with locally advanced or metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. J. ImmunOther Cancer. 2023;11(2) doi: 10.1136/jitc-2022-006055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Msaouel P., et al. A phase 2 study of Sitravatinib in combination with Nivolumab in patients with advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma. Eur. Urol. Oncol. 2023 doi: 10.1016/j.euo.2023.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang X., et al. SAFFRON-103: a phase ib study of sitravatinib plus tislelizumab in anti-PD-(L)1 refractory/resistant advanced melanoma. Immunotherapy. 2024;16(4):243–256. doi: 10.2217/imt-2023-0130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duncavage E.J., et al. Genomic profiling for clinical decision making in myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia. Blood. 2022;140(21):2228–2247. doi: 10.1182/blood.2022015853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jen W.Y., et al. Combination therapy with novel agents for acute myeloid leukaemia: insights into treatment of a heterogenous disease. Br. J. Haematol. 2024 doi: 10.1111/bjh.19519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Recher C., et al. Long-term survival after intensive chemotherapy or hypomethylating agents in AML patients aged 70 years and older: a large patient data set study from European registries. Leukemia. 2022;36(4):913–922. doi: 10.1038/s41375-021-01425-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buchner T., et al. Age-related risk profile and chemotherapy dose response in acute myeloid leukemia: a study by the German Acute Myeloid Leukemia Cooperative Group. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009;27(1):61–69. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.4245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wysota M., Konopleva M., Mitchell S. Novel therapeutic targets in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2024;26(4):409–420. doi: 10.1007/s11912-024-01503-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Forsberg M., Konopleva M. AML treatment: conventional chemotherapy and emerging novel agents. Trends. Pharmacol. Sci. 2024;45(5):430–448. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2024.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abaza Y., McMahon C., Garcia J.S. Advancements and challenges in the treatment of AML. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book. 2024;44(3) doi: 10.1200/EDBK_438662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.DiNardo C.D., et al. Azacitidine and venetoclax in previously untreated acute myeloid leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;383(7):617–629. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2012971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Konopleva M., et al. Efficacy and biological correlates of response in a phase II study of venetoclax monotherapy in patients with acute myelogenous leukemia. Cancer Discov. 2016;6(10):1106–1117. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-16-0313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pulte E.D., et al. FDA approval summary: gilteritinib for relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia with a FLT3 mutation. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021;27(13):3515–3521. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-4271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Erba H.P., et al. Quizartinib plus chemotherapy in newly diagnosed patients with FLT3-internal-tandem-duplication-positive acute myeloid leukaemia (QuANTUM-First): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2023;401(10388):1571–1583. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00464-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xuan L., et al. Sorafenib maintenance in patients with FLT3-ITD acute myeloid leukaemia undergoing allogeneic haematopoietic stem-cell transplantation: an open-label, multicentre, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(9):1201–1212. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30455-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lang T.J.L., et al. Mechanisms of resistance to small molecules in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancers. (Basel) 2023;(18):15. doi: 10.3390/cancers15184573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Desikan S.P., et al. Resistance to targeted therapies: delving into FLT3 and IDH. Blood Cancer J. 2022;12(6):91. doi: 10.1038/s41408-022-00687-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jin H., Wang L., Bernards R. Rational combinations of targeted cancer therapies: background, advances and challenges. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2023;22(3):213–234. doi: 10.1038/s41573-022-00615-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Daver N., et al. Venetoclax plus gilteritinib for FLT3-mutated relapsed/refractory acute myeloid leukemia. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022;40(35):4048–4059. doi: 10.1200/JCO.22.00602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhu R., et al. FLT3 tyrosine kinase inhibitors synergize with BCL-2 inhibition to eliminate FLT3/ITD acute leukemia cells through BIM activation. Signal. Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021;6(1):186. doi: 10.1038/s41392-021-00578-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nachmias B., et al. Venetoclax resistance in acute myeloid leukaemia-clinical and biological insights. Br. J. Haematol. 2024;204(4):1146–1158. doi: 10.1111/bjh.19314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alotaibi A.S., et al. Patterns of resistance differ in patients with acute myeloid leukemia treated with type I versus Type II FLT3 inhibitors. Blood Cancer Discov. 2021;2(2):125–134. doi: 10.1158/2643-3230.BCD-20-0143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lindblad O., et al. Aberrant activation of the PI3K/mTOR pathway promotes resistance to sorafenib in AML. Oncogene. 2016;35(39):5119–5131. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu J., et al. Mechanisms of venetoclax resistance and solutions. Front. Oncol. 2022;12 doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.1005659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Singh Mali R., et al. Venetoclax combines synergistically with FLT3 inhibition to effectively target leukemic cells in FLT3-ITD+ acute myeloid leukemia models. Haematologica. 2021;106(4):1034–1046. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2019.244020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang Y., et al. Modulating the function of ABCB1: in vitro and in vivo characterization of sitravatinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor. Cancer Commun. (Lond) 2020;40(7):285–300. doi: 10.1002/cac2.12040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang Y., et al. Sitravatinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, inhibits the transport function of ABCG2 and restores sensitivity to chemotherapy-resistant cancer cells in vitro. Front. Oncol. 2020;10:700. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.00700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ebner J., et al. ABCC1 and glutathione metabolism limit the efficacy of BCL-2 inhibitors in acute myeloid leukemia. Nat. Commun. 2023;14(1):5709. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-41229-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data created or analyzed during this study are enrolled in this published article or are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.