Abstract

Background

Peripheral arterial disease (PAD) is common and is a marker of systemic atherosclerosis. Patients with symptoms of intermittent claudication (IC) are at increased risk of cardiovascular events (myocardial infarction (MI) and stroke) and of both cardiovascular and all cause mortality.

Objectives

To determine the effectiveness of antiplatelet agents in reducing mortality (all cause and cardiovascular) and cardiovascular events in patients with intermittent claudication.

Search methods

The Cochrane Peripheral Vascular Diseases group searched their Specialised Register (last searched April 2011) and CENTRAL (2011, Issue 2) for publications on antiplatelet agents and IC. In addition reference lists of relevant articles were also searched.

Selection criteria

Double‐blind randomised controlled trials comparing oral antiplatelet agents versus placebo, or versus other antiplatelet agents in patients with stable intermittent claudication were included. Patients with asymptomatic PAD (stage I Fontaine), stage III and IV Fontaine PAD, and those undergoing or awaiting endovascular or surgical intervention were excluded.

Data collection and analysis

Data on methodological quality, participants, interventions and outcomes including all cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, cardiovascular events, adverse events, pain free walking distance, need for revascularisation, limb amputation and ankle brachial pressure indices were collected. For each outcome, the pooled risk ratio (RR) or mean difference (MD) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) was calculated.

Main results

A total of 12 studies with a combined total of 12,168 patients were included in this review. Antiplatelet agents reduced all cause (RR 0.76, 95% CI 0.60 to 0.98) and cardiovascular mortality (RR 0.54, 95% CI 0.32 to 0.93) in patients with IC compared with placebo. A reduction in total cardiovascular events was not statistically significant (RR 0.80, 95% CI 0.63 to 1.01). Data from two trials (which tested clopidogrel and picotamide respectively against aspirin) showed a significantly lower risk of all cause mortality (RR 0.73, 95% CI 0.58 to 0.93) and cardiovascular events (RR 0.81, 95% CI 0.67 to 0.98) with antiplatelets other than aspirin compared with aspirin. Antiplatelet therapy was associated with a higher risk of adverse events, including gastrointestinal symptoms (dyspepsia) (RR 2.11, 95% CI 1.23 to 3.61) and adverse events leading to cessation of therapy (RR 2.05, 95% CI 1.53 to 2.75) compared with placebo; data on major bleeding (RR 1.73, 95% CI 0.51, 5.83) and on adverse events in trials of aspirin versus alternative antiplatelet were limited. Risk of limb deterioration leading to revascularisation was significantly reduced by antiplatelet treatment compared with placebo (RR 0.65, 95% CI 0.43 to 0.97).

Authors' conclusions

Antiplatelet agents have a beneficial effect in reducing all cause mortality and fatal cardiovascular events in patients with IC. Treatment with antiplatelet agents in this patient group however is associated with an increase in adverse effects, including GI symptoms, and healthcare professionals and patients need to be aware of the potential harm as well as the benefit of therapy; more data are required on the effect of antiplatelets on major bleeding. Evidence on the effectiveness of aspirin versus either placebo or an alternative antiplatelet agent is lacking. Evidence for thienopyridine antiplatelet agents was particularly compelling and there is an urgent need for multicentre trials to compare the effects of aspirin against thienopyridines.

Keywords: Humans, Cause of Death, Intermittent Claudication, Intermittent Claudication/drug therapy, Intermittent Claudication/mortality, Myocardial Infarction, Myocardial Infarction/mortality, Myocardial Infarction/prevention & control, Platelet Aggregation Inhibitors, Platelet Aggregation Inhibitors/adverse effects, Platelet Aggregation Inhibitors/therapeutic use, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Stroke, Stroke/mortality, Stroke/prevention & control

Plain language summary

Antiplatelet agents for reducing risks in patients with peripheral arterial disease and cramping pain in legs on walking

Peripheral arterial disease (PAD) refers to the blocking of large arteries. Patients with peripheral arterial disease as a result of narrowing of the arteries in the legs may present with cramping pain in the legs or buttocks on walking; this is also known as intermittent claudication (IC). This group of patients are at high risk of a heart attack, stroke and death. Treatment often involves stopping cigarette smoking and the optimising of other risk factors such as diabetes, high blood pressure and cholesterol. Another treatment often used to reduce the risk of heart attacks and strokes in patients with IC is antiplatelet treatment. Antiplatelets make the blood less sticky and therefore block the formation of blood clots, thereby preventing blockages in arteries which can cause heart attacks and strokes. Antiplatelet treatments include drugs such as aspirin, clopidogrel and dipyridamole, but there is limited evidence to date on the benefits of antiplatelet therapy in patients with IC. Twelve studies with a total of 12,168 patients were included in this review. The analyses show that, in patients with IC, antiplatelet agents reduced the risk of death from all causes, and from heart attack and stroke combined when compared with placebo. When aspirin was compared with other antiplatelet agents, there was some evidence that the alternative antiplatelet had a more beneficial effect in reducing all cause mortality or of suffering a cardiovascular event such as heart attack or stroke. However, this was based on only two trials. Antiplatelet usage, however, does increase the risk of indigestion and may also increase risk of major bleeding events. Despite its widespread use, the evidence for first line use of aspirin in patients with IC is weak and further research is required to determine whether aspirin would be better replaced by a different class of antiplatelet agent which has a greater beneficial effect with fewer side‐effects.

Background

Description of the condition

Atherosclerotic peripheral arterial disease (PAD) of the lower limb is common. In the Edinburgh Artery Study of men and women aged 55 to 74 years, 4.5% had symptomatic PAD. A further 8% had evidence of major asymptomatic disease and 16.6% had abnormal haemodynamic parameters suggesting minor PAD (Fowkes 1991). Epidemiological studies have shown that the incidence of PAD increases with age (Fowkes 1991; Selvin 2004) and is more common in men (Fowkes 2008). One of the commonest non‐invasive methods of diagnosing PAD is the ankle brachial pressure index (ABPI). An ABPI < 0.9 is 95% sensitive and 100% specific for detecting angiogram positive disease (Norgren 2007). Peripheral arterial disease encompasses a spectrum of disease severity. In its early stages, PAD may be asymptomatic. The most common symptom, intermittent claudication (IC), occurs in approximately 0.5 to 14% of the population depending on age, sex and geographical location (Balkau 1994; Fowkes 1991). People with IC experience pain in the calves, thighs or buttocks when they are walking and the pain subsides with rest. At the other extreme of the disease, PAD may manifest as rest pain, ulceration or gangrene.

Many patients with IC have relatively mild complaints, but up to 20% of patients will go on to require reconstructive surgery, and 1 to 2% will eventually undergo amputation (Kannel 1970; Leng 1993). Patients with symptomatic IC can have reduced levels of mobility and quality of life which equate to that associated with some cancers (Belch 2003). Peripheral arterial disease is also a marker of systemic atherosclerosis, and is associated with both concomitant and subsequent coronary and cerebrovascular disease (Aronow 1994; Newman 1993). Compared with age‐matched controls, patients with IC have a three to six‐fold increase in cardiovascular mortality (Criqui 1992; Leng 1996). In the Reduction of Atherothrombosis for Continued Health (REACH) multi‐national registry of patients with known cardiovascular disease or increased cardiovascular risk, the highest cardiovascular event rate was in patients with PAD. At one year follow‐up, 18.2% of PAD patients had suffered a cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction (MI), or stroke, or had been hospitalised for a cardiovascular event compared with 13.3% of the coronary artery disease group and 10% of the cerebrovascular disease group (Steg 2007).

The majority of patients with IC are treated conservatively, including smoking cessation and regular exercise (Gardner 1995; Watson 2008) to improve the collateral blood vessels supplying the lower limbs. Smoking is a particularly important modifiable risk factor for PAD: smokers with PAD are more likely to progress to critical limb ischaemia and to require an amputation or vascular intervention (Jonason 1985) and smoking cessation can reduce overall cardiovascular risk to the level of non‐smokers within two to four years (Rosenberg 1990). Diabetes mellitus is also an important risk factor for the development of PAD. People with diabetes have a 1.5 to 2.5 fold increased risk of symptomatic and asymptomatic PAD compared with non‐diabetics, and the life‐time risk of a lower limb amputation is increased 10 to 16 times (Al‐Delaimy 2004; MacGregor 1999). To date, antihypertensive agents (Singer 2008) and lipid‐lowering therapy (Aung 2007; HPSCG 2007; Meade 2002) have been shown to reduce cardiovascular mortality and morbidity in patients with PAD.

Description of the intervention

Platelets play a key role in haemostasis and in the pathogenesis of atherosclerotic disease. Circulating platelets are quiescent and do not bind to the intact endothelium. However, endothelial damage following injury leads to exposure of circulating platelets to the subendothelial extracellular matrix and triggers platelet recruitment and adhesion (Varga‐Szabo 2008). Platelet adhesion occurs when the von Willebrand factor binds to various glycoprotein (GP) receptors (GP Ib‐IX‐V complex); receptors for collagen and fibronectin also participate in platelet adhesion. Adherent platelets secrete preformed adenosine diphosphate (ADP), fibrinogen, thromboxane A2 (TXA2), and other chemotaxins; clotting factors; and vasoconstrictors from granules, which activate the platelets (Hiatt 2002b). Activated platelets change their shape and secrete ADP and platelet‐derived growth factor, fibrinogen and TXA2. Platelet aggregation involves recruitment of additional platelets and is mediated by the GPIIb/IIIa receptor. This forms a prothrombotic surface that promotes clot formation, contributing to the fibrous plaque development and the consequent thromboembolic complications. The latter can lead to myocardial infarction, stroke or peripheral vascular occlusions (Davi 2007). There is evidence to suggest that PAD is associated with a hypercoagulable state. Blood viscosity, for example, is increased in with patients with claudication (Fagher 1993). Antiplatelet agents, such as aspirin, dipyridamole, picotamide, ticlodipine and clopidogrel act at specific sites of platelet activation and affect multiple pathways. Aspirin (a cyclo‐oxygenase inhibitor) interferes with the biosynthesis of TXA2, prostacyclin and other prostaglandins (Awtry 2000). Dipyridamole (a phosphodiesterase inhibitor) is a platelet adhesion inhibitor that exerts its effects by inhibiting the phosphodiesterase and blocking the uptake of adenosine (Patrono 2004). Picotamide on the other hand interferes with arachidonic acid cascade of platelets by inhibiting TXA2 synthase and antagonising TXA2 receptors (Ratti 1998). Unlike aspirin, picotamide does not affect cyclo‐oxygenase. Ticlopidine and clopidogrel (thienopyridines) interfere with ADP‐mediated platelet activation and aggregation and cause an irreversible non‐competitive inhibition of platelet function (Schror 2000).

Why it is important to do this review

Current use of antiplatelet treatment to reduce the risk of cerebrovascular and coronary events in high risk patients subgroups is based to a great extent on evidence inferred from a meta‐analysis of randomised controlled trials involving patients with coronary and cerebrovascular disease (ATC 2002). The benefit of antiplatelet agents specifically in patients with IC is unknown. In addition, use of antiplatelet agents can be associated with an increased risk of gastrointestinal ulcer and haemorrhage and other adverse events, such as blood dyscrasias (neutropaenia and thrombocytopaenia). There is currently no clear evidence on the risk‐benefit ratio of antiplatelet therapy in people with IC. Novel antiplatelet agents with potentially increased effectiveness and fewer side‐effects compared with aspirin and other older antiplatelet agents are being developed (Ueno 2011), however, there is a paucity of evidence comparing the effectiveness of one antiplatelet agent over another.

Objectives

The primary aim of this review was to determine the effectiveness of antiplatelet agents in reducing mortality (all cause and cardiovascular), and cardiovascular events (fatal and non‐fatal myocardial infarction or stroke) in patients with stable intermittent claudication (Fontaine stage II) (Fontaine 1954).

In addition, the efficacy of antiplatelet agents in reducing the need for revascularisation of the lower limbs and preventing amputation; improving treadmill walking distance; and improving ankle brachial pressure index was assessed. Adverse effects (in particular, major bleeding, gastrointestinal side‐effects and side‐effects leading to cessation of treatment) were also assessed. The efficacy of one or more antiplatelet agent(s) versus placebo or versus an alternative antiplatelet agent was considered.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included all double‐blinded, randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing oral antiplatelet agents versus control, or versus other antiplatelet agents in patients with stable IC (Fontaine stage II) (Fontaine 1954). We excluded quasi‐RCTs, single‐blinded or open studies. Quasi‐RCTs are studies randomised by methods of allocation such as alternation, date of birth or case record number (Higgins 2011). We excluded cross‐over trials because we considered them inappropriate for antiplatelet agent treatment in this study population. Minimum duration of follow‐up for trials to be considered for the review was 24 weeks.

Types of participants

We included all patients presenting with stable IC (Fontaine stage II) for more than six months. We excluded studies which included patients with asymptomatic PAD, rest pain, ischaemic ulcer or gangrene (Fontaine stages I, III and IV). Similarly, we excluded patients undergoing planned future vascular surgical intervention (angioplasty, surgery or amputation).

Types of interventions

We considered trials which compared either single or combination oral antiplatelet agents (aspirin, indobufen, sulphinpyrazone, dipyridamole, picotamide, clopidogrel, ticlopidine, prasugrel, ticagrelor, elinogrel, atopaxar and vorapaxar) with placebo or other antiplatelet agent . The intervention must have been given for at least three months. We recorded the type of therapy, dosage, time of starting and duration of therapy. We excluded trials comparing antiplatelets with exercise, anticoagulants or surgery (angioplasty or bypass). We also did not consider studies incorporating vasodilating agents (beraprost, iloprost, cilostazol, pentoxifylline, suloctidil and trapidil), where the main mechanism of action is not thought to be via their antiplatelet effect.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

All cause mortality

Cardiovascular mortality (death from stroke or myocardial infarction)

Cardiovascular events (fatal and non‐fatal myocardial infarction or stroke)

Secondary outcomes

Adverse events: major bleeding, GI symptoms (specifically dyspepsia) and adverse events leading to cessation of therapy

Pain free walking distance

Revascularisation (angioplasty or surgical bypass)

Limb amputation

Change in ankle brachial pressure index

All definitions were standardised whenever possible.

Major bleeding was defined as a bleeding event that resulted in one or more of the following:

death;

a decrease in haemoglobin concentration of 2 g/dL or more;

transfusion of at least 2 units of blood;

bleeding from a retroperitoneal, intracranial, or intraocular site;

a serious or life‐threatening clinical event;

need for surgical or medical intervention.

Inconsistent or missing outcome definitions were considered as a source of bias.

Search methods for identification of studies

We applied no language restriction on publications or any restrictions regarding publication status.

Electronic searches

The Cochrane Peripheral Vascular Diseases Group searched their Specialised Register (last searched April 2011) and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library 2011, Issue 2) at www.thecochranelibrary.com. See Appendix 1 for details of the search strategy used to search CENTRAL. The Specialised Register is maintained by the Trials Search Co‐ordinator (TSC) and is constructed from weekly electronic searches of MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL and AMED; and through handsearching relevant journals. The full list of the databases, journals and conference proceedings which have been searched, as well as the search strategies used, are described in the Specialised Register section of the Cochrane Peripheral Vascular Diseases (PVD) Group module in The Cochrane Library (www.thecochranelibrary.com).

The following trial databases were searched by the TSC (April 2011) using the term "intermittent claudication" for details of ongoing and unpublished studies:

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry http://apps.who.int/trialsearch/; ClinicalTrials.gov http://clinicaltrials.gov/; Current Controlled Trials http://www.controlled‐trials.com/.

Searching other resources

We searched the reference lists of articles retrieved by electronic searches for additional citations. We contacted trialists for further information in cases where there were missing data or doubts about whether to include trials in the review.

Data collection and analysis

We performed separate analyses for trials of (1) antiplatelet agent(s) versus placebo and (ii) antiplatelet agent(s) versus an alternative antiplatelet agent.

Selection of studies

Two authors (PW and LYC) independently selected trials for inclusion based on titles and abstract retrieved from the full search. Full text papers were obtained and further screening was performed independently by two authors (PW and LYC) if it was felt that the trial could possibly meet the inclusion criteria. In the event of disagreements, a consensus was reached by discussion and if necessary, a final decision was reached following involvement of a third author (GS).

Data extraction and management

Data extraction from included trials was performed independently by two authors (PW and LYC) and entered into a standardised electronic spreadsheet (Microsoft Excel, for details, see Characteristics of included studies). Data from multiple reports of the same study were extracted directly onto a single data collection form on the spreadsheet. The data collated were then compared and any discrepancies or disagreements were resolved by discussion.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two authors (PW and LYC) independently assessed study eligibility and risk of bias using the following domain‐based evaluation: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data and selective reporting according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a). The risk of bias was classified as 'low risk', 'unclear risk' or 'high risk', and a rating was provided for each study (and for each outcome, for those risks of biases that were outcome specific).

Measures of treatment effect

We used the statistical package (Review Manager 5.1) provided by the Cochrane Collaboration to analyse data. For dichotomous outcomes, statistical analysis was presented as risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence interval (CI). We used mean difference (MD) with 95% CI for continuous outcomes.

Unit of analysis issues

Participating individuals in the individually randomised trials were the unit of analysis.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted the principal authors of included studies when necessary to clarify data and to provide missing information.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We based all analyses on the intention‐to‐treat data from individual trials. We assessed trial heterogeneity using Chi2 test of heterogeneity, and I2 statistic, which describes the percentage of the variability in effect estimates that is due to heterogeneity rather than sampling error (chance). Where heterogeneity was identified (P < 0.1 or I2 > 50%), we investigated the reason for heterogeneity. If no apparent reason was found, we conducted a random‐effects meta‐analysis to incorporate heterogeneity among studies. In the absence of heterogeneity, we used a fixed‐effect model.

Assessment of reporting biases

We planned to use asymmetry in funnel plots to assess reporting bias but due to the small number of included trials, the power of this analysis would have been too low to distinguish chance from real asymmetry, and therefore this was not performed.

Data synthesis

Where clinical or statistical heterogeneity existed (P < 0.1 or I2 > 50%), we used a random‐effects model. In the absence of heterogeneity we used a fixed‐effect model.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to perform a subgroup analysis for patients with and without diabetes; this was not possible due to the small number of trials that recruited and stratified patients by diabetic status.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to perform sensitivity analyses based on the risk of bias if there were studies with very high risk of bias included (that is, with high risk methods of allocation concealment and random sequence generation).

Results

Description of studies

For a detailed description of studies, see Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies.

Results of the search

The combined search yielded 1626 records and out of these we identified 232 potentially suitable titles and abstracts . Following review of these titles and abstracts, two authors (PW and LYC) independently reviewed 197 full text articles, of which 115 were found to potentially meet the inclusion criteria (Figure 1). These were assessed further for inclusion in the review.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

Twelve trials (published in 17 articles) of antiplatelet therapy in patients with IC were included in the review (ADEP 1993; Arcan 1988; Aukland 1982; Auteri 1995; Balsano 1989; CAPRIE 1996; Coto 1989; DAVID 2004; EMATAP 1993; Signorini 1988; STIMS 1990; Tonnesen 1993).

The breakdown of studies according to the countries in which they were performed was as follows:

One Argentinian (EMATAP 1993);

Five Italian (ADEP 1993; Auteri 1995; Coto 1989; DAVID 2004; Signorini 1988);

One Swedish (STIMS 1990);

One British (Aukland 1982);

Two European (Arcan 1988; Balsano 1989);

Two multinational (CAPRIE 1996; Tonnesen 1993).

A total of 12,168 patients were recruited into the trials. The number of participants in each trial ranged from 40 (Signorini 1988) to 6452 (CAPRIE 1996). The age range of participants was 21 to 80 years of age. One trial recruited male patients only (Aukland 1982). Six trials incorporated patients with previous reconstructive surgery or amputation (ADEP 1993; Aukland 1982; CAPRIE 1996; DAVID 2004; EMATAP 1993; STIMS 1990). Two trials excluded patients with insulin dependent diabetes (Auteri 1995; STIMS 1990), and three trials excluded all patients with diabetes (Coto 1989; Signorini 1988; Tonnesen 1993). One trial specifically recruited patients with both IC and diabetes (DAVID 2004).

Ten trials compared an antiplatelet agent against placebo (ADEP 1993; Arcan 1988; Aukland 1982; Auteri 1995; Balsano 1989; Coto 1989; EMATAP 1993; Signorini 1988; STIMS 1990; Tonnesen 1993), and two trials compared an antiplatelet agent against aspirin (CAPRIE 1996; DAVID 2004). The most common antiplatelet agent tested was ticlopidine (Arcan 1988; Aukland 1982; Balsano 1989; EMATAP 1993; STIMS 1990). The breakdown of antiplatelet agents tested was as follows:

Clopidogrel versus aspirin (CAPRIE 1996);

Indobufen versus placebo (Signorini 1988; Tonnesen 1993);

Picotamide versus placebo (ADEP 1993; Coto 1989) or aspirin (DAVID 2004);

Ticlopidine versus placebo (Arcan 1988; Aukland 1982; Balsano 1989; EMATAP 1993; STIMS 1990);

Triflusal versus placebo (Auteri 1995).

Power calculations were performed in eight trials (ADEP 1993; Arcan 1988; Auteri 1995; CAPRIE 1996; DAVID 2004; EMATAP 1993; STIMS 1990; Tonnesen 1993). Intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis was performed in seven trials (ADEP 1993; Arcan 1988; CAPRIE 1996; DAVID 2004; EMATAP 1993; STIMS 1990; Tonnesen 1993).

A placebo run‐in period was used in six trials (ADEP 1993; Arcan 1988; Aukland 1982; Balsano 1989; Coto 1989; Tonnesen 1993).

The length of follow‐up varied between the trials:

24 weeks to 12 months: seven trials (Arcan 1988; Aukland 1982; Auteri 1995; Coto 1989; EMATAP 1993; Signorini 1988; Tonnesen 1993);

13 to 24 months: four trials (ADEP 1993; Balsano 1989; CAPRIE 1996; DAVID 2004);

> 5 years: one trial (STIMS 1990).

In terms of primary outcome events, seven trials (ADEP 1993; Arcan 1988; Balsano 1989; CAPRIE 1996; DAVID 2004; EMATAP 1993; STIMS 1990) reported both all cause and cardiovascular mortality. Cardiovascular events (fatal and non‐fatal MI or stroke) were reported in eight trials (ADEP 1993; Arcan 1988; Balsano 1989; CAPRIE 1996; Coto 1989; DAVID 2004; EMATAP 1993; STIMS 1990).

In terms of adverse events, major bleeding was reported in two trials (Balsano 1989; DAVID 2004) and ten trials reported adverse GI symptoms (ADEP 1993; Arcan 1988; Aukland 1982; Auteri 1995; Balsano 1989; Coto 1989; DAVID 2004; EMATAP 1993; Signorini 1988; Tonnesen 1993). Nine trials reported adverse events leading to early cessation of therapy (ADEP 1993; Arcan 1988; Auteri 1995; Balsano 1989; Coto 1989; DAVID 2004; EMATAP 1993; STIMS 1990; Tonnesen 1993).

For local disease outcomes, walking distance was reported in four trials (Auteri 1995; Coto 1989; Signorini 1988; Tonnesen 1993) and two trials had these data in graphical form (Arcan 1988; Balsano 1989). One of the studies (Auteri 1995) only reported walking distance for the antiplatelet intervention group and noted that there was no statistically significant difference compared with the placebo group.

Six trials reported progression of disease leading to revascularisation (ADEP 1993; Arcan 1988; Aukland 1982; Balsano 1989; EMATAP 1993; STIMS 1990) and there were four trials with data on limb deterioration leading to amputation (ADEP 1993; Balsano 1989; DAVID 2004; STIMS 1990). Data on ABPI were reported in one trial (Coto 1989).

Sources of funding were declared in four trials (ADEP 1993; CAPRIE 1996; DAVID 2004; STIMS 1990).

Excluded studies

Ninety‐eight reports of studies were excluded.

We excluded studies which did not fulfil the inclusion criteria. Reasons for exclusion were:

non‐randomised studies (Fiotti 2003; Randi 1985; Smith 1981);

no control group (Belcaro 1991; Mannucci 1987);

shorter than required treatment duration (Abrahamsen 1974; Davi 1985; Jagroop 2004, Landini 1989; Leo 2007; Mangiafico 2000; Pasqualini 2002);

cross‐over trials (Abrahamsen 1974; Canonico 1991; Davi 1985; Eikelboom 2005; Nenci 1979; Nenci 1982; Novo 1996; Wilhite 2003);

using comparison agents excluded from the review (Adriaensen 1976; Ahn 1992; Allegra 1993; Allegra 1994; Andreozzi 1993; Brass 2006; Castano 1999; Castano 2001; Castano 2003; Castano 2004; Cesarone 1994; Ciocon 1997; Duda 2001; Elam 1998; Gillot 1976; Gregoratti 1982; Gresele 2000; Guan 2003; Hevia 1992; Hiatt 2002; Holm 1984; Hsieh 2009; Jones 1982; Kakkar 1981; Labs 1999; Lievre 1996; Lievre 2000; Mangiafico 2000; Mannarino 1991; Mantero 1983; Marelli 1990; Marrapodi 1994; Miyazaki 2007; Mohler 2003; Norgren 2006; Novo 1996; O'Donnell 2008; O'Donnell 2009; Okadome‐Kenchiro 1992; Panchenko 1997; Pollastri 1991; Regenthal 1991; Rossini 1998; Roztocil 1989; Warfarin 2007);

populations that did not meet inclusion criteria, for example, studies which included patients with planned surgical interventions (Cassar 2005; Cassar 2005a; Creutzig 1994; Ehresmann 1977; Ranke 1992; Ranke 1993; Ranke 1994;Schweizer 2003), or asymptomatic PAD participants (CHARISMA 2009; CLIPS 2007; Fowkes 2010; POPADAD 2008) and stage III and IV Fontaine patients (Fabris 1992; Katsumura 1982; Randi 1985);

ex‐vivo studies (Cassar 2006);

unusual dosing (Giansante 1990) for example, once every third day;

trial proposal (Singer 2006; Tepe 2007).

Studies which fulfilled the inclusion criteria (Baumgartner 1992; Bhatt 2000; Boneu 1996; Destors 1985; Harker 1999; Hawker 1984; Hess 1985; Libretti 1986; Libretti 1986a; Neirotti 1994, Randi 1991, Rudofsky 1987; Schoop 1987; Stiegler 1984; Topol 2000) but did not report on any of the primary or secondary outcomes were excluded. Trials in which results for a subgroup of patients with IC were not available separately were also excluded. One study was excluded because of unclear patient grouping and reporting of results (Catalano 1984).

Risk of bias in included studies

See Figure 2 and Figure 3 for a graphical presentation of the risk of bias. Many studies were conducted in the late 1980s or 1990s. The reporting of the methods section was brief in the study papers, and it was not possible to obtain a record of the full protocol. The lack of details was the main reason for the 'unclear' rating for most studies for selection bias, and selective reporting bias.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

In six trials, the method of randomisation was described or performed by an independent organisation (ADEP 1993; Arcan 1988; CAPRIE 1996; DAVID 2004; EMATAP 1993; STIMS 1990), with a low perceived risk of bias. The randomisation method was unclear in six trials (Aukland 1982; Auteri 1995; Balsano 1989; Coto 1989; Signorini 1988; Tonnesen 1993). Allocation concealment method was not reported in most studies.

Blinding

Apart from two studies (Coto 1989; Signorini 1988), all studies clearly reported that a double‐blinded trial was conducted, and reported the methods used to achieve blinding for investigators and patients. Aside from two additional studies which did not clearly report how investigators measuring the outcomes were blinded to the treatment assignment (STIMS 1990; Tonnesen 1993), all other studies reported the method used to prevent detection bias. Many studies used independent committees blinded to treatment allocation to independently verify and assess outcomes.

Incomplete outcome data

Most studies conducted ITT analyses, and continued follow‐up and reporting of patients who discontinued treatment early, and were therefore classed as low risk of bias. The risk of bias was high for six studies (ADEP 1993; Arcan 1988; Aukland 1982; Balsano 1989; DAVID 2004; Signorini 1988), where the drop out rate was high or the absolute difference in the drop‐out rates were large compared with the primary outcome event rates, or both. The follow‐up period varied between studies and ranged from six months (Arcan 1988; Auteri 1995; Coto 1989; EMATAP 1993; Signorini 1988; Tonnesen 1993) to up to seven years (STIMS 1990).

Selective reporting

Many of the studies were conducted in the late 1980s and 1990s. The protocols for these studies were often not clearly reported. Therefore, the risk of bias was unclear for most studies (Auteri 1995; Balsano 1989; Coto 1989; Signorini 1988) and high for one study (Aukland 1982).

Effects of interventions

Twelve trials that fulfilled the inclusion criteria were included in the review. Five antiplatelet agents were tested (clopidogrel, indobufen, picotamide, ticlopidine and triflusal) in these 12 trials. The effects of antiplatelet agents were considered in two separate categories: antiplatelet agent(s) against placebo and antiplatelet agent(s) against aspirin. The initial protocol (Robless 2003) planned to perform analyses on differences in quality of life (QoL) and cost‐effectiveness between patients who received antiplatelet and control, however, there were no data on these outcomes in the included trials. Neither were any reports of cost‐effectiveness of the different agents found.

1. Antiplatelet agent(s) versus placebo

Four different antiplatelet agents (indobufen, picotamide, ticlopidine and triflusal) were tested against placebo in ten trials (ADEP 1993; Arcan 1988; Aukland 1982; Auteri 1995; Balsano 1989; Coto 1989; EMATAP 1993; Signorini 1988; STIMS 1990; Tonnesen 1993). Overall, 4507 patients were included from these trials (2246 in the antiplatelet group, and 2261 in the placebo group).

Primary outcomes

All cause mortality

All cause mortality was reported in five trials (ADEP 1993; Arcan 1988; Balsano 1989; EMATAP 1993; STIMS 1990). Meta‐analysis showed a statistically significant benefit of antiplatelet agents in reducing all cause mortality (RR 0.76, 95% CI 0.60 to 0.98) (P = 0.03, Analysis 1.1). Combined data from trials of ticlopidine, which showed a statistically significant effect in reducing all cause mortality (RR 0.73, 95% CI 0.56 to 0.96) (P = 0.02), contributed 81.9% of weight to this analysis.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antiplatelet agent versus placebo, Outcome 1 All cause mortality.

Cardiovascular mortality

Antiplatelet agents demonstrated a statistically significant benefit in reducing cardiovascular mortality in meta‐analysis of four trials that reported this outcome (Arcan 1988; Balsano 1989; EMATAP 1993; STIMS 1990) (RR 0.54, 95% CI 0.32 to 0.93) (P = 0.03, Analysis 1.2). All four trials used ticlopidine as the drug of intervention.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antiplatelet agent versus placebo, Outcome 2 Cardiovascular mortality (fatal stroke or MI).

Cardiovascular events

Data were reported for cardiovascular events (fatal and non‐fatal MI or stroke) in six trials (ADEP 1993; Arcan 1988; Balsano 1989; Coto 1989; EMATAP 1993; STIMS 1990). However, one of these, a small trial (n = 40) with six months of follow‐up and a single angina pectoris event in the treatment group (Coto 1989) was excluded from our meta‐analysis on this outcome since "major cardiovascular event" was not defined and it was unclear whether this was a pre‐planned outcome. In meta‐analysis of the remaining five trials, there was a non‐significant reduction in total cardiovascular events in participants receiving antiplatelet therapy compared with placebo (RR 0.80, 95% CI 0.63 to 1.01) (P = 0.06, Analysis 1.3).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antiplatelet agent versus placebo, Outcome 3 Cardiovascular event (fatal and non‐fatal MI or stroke).

We subsequently analysed results for the following sub‐categories of cardiovascular events separately; total MI (fatal and non‐fatal), fatal MI, non‐fatal MI, total stroke (fatal and non‐fatal), fatal stroke and non‐fatal stroke. For total MI, data were available from all five trials contributing data on total cardiovascular events. No statistically significant reduction in total MI with antiplatelet therapy was found (RR 0.84, 95% CI 0.63 to 1.12) (P = 0.24, Analysis 1.4). Subgroup analyses by class of antiplatelet did not reveal evidence of a statistically significant reduction in total MI.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antiplatelet agent versus placebo, Outcome 4 Myocardial infarction (fatal and non‐fatal).

For fatal and non‐fatal MI separately, data were available from only four of the five trials contributing data on total MI, since the ADEP 1993 study reported only combined fatal and non‐fatal MI. There were no fatal MIs reported in three of these trials (Arcan 1988; Balsano 1989; EMATAP 1993) and in the remaining trial (STIMS 1990) there was no statistically significant effect of antiplatelet therapy (ticlopidine) on fatal MI (RR 0.57, 95% CI 0.31 to 1.05) (P = 0.07, Analysis 1.5). Meta‐analysis of data from the four trials reporting non‐fatal MI showed no statistically significant difference in non‐fatal MI between antiplatelet and placebo (RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.69 to 1.48) (P = 0.96, Analysis 1.6).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antiplatelet agent versus placebo, Outcome 5 Myocardial infarction (fatal).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antiplatelet agent versus placebo, Outcome 6 Myocardial infarction (non‐fatal).

None of the five trials that reported on total stroke (fatal and non‐fatal) showed a statistically significant reduction in this outcome with antiplatelet and overall there was no statistically significant difference in total stroke between antiplatelet and placebo groups in the meta‐analysis (RR 0.71, 95% CI 0.45 to 1.13) (P = 0.15, Analysis 1.7). Subgroup analyses by class of antiplatelet did not reveal evidence of a statistically significant reduction in stroke events. Meta‐analyses of 4 trials reporting fatal and non‐fatal stroke separately (one trial (ADEP 1993) only reported total stroke events) also did not show statistically significant differences between antiplatelet and placebo for either fatal stroke (RR 0.33, 95% CI 0.07 to 1.64) (P = 0.18, Analysis 1.8) or non‐fatal stroke (RR 0.74, 95% CI 0.42 to 1.30) (P = 0.30, Analysis 1.9).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antiplatelet agent versus placebo, Outcome 7 Stroke (fatal and non‐fatal).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antiplatelet agent versus placebo, Outcome 8 Stroke (fatal).

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antiplatelet agent versus placebo, Outcome 9 Stroke (non‐fatal).

Secondary outcomes

Adverse events

Three main adverse events were considered in this review: major bleeding, GI symptoms (dyspepsia) and adverse events leading to early cessation of treatment. Only two trials (Balsano 1989; STIMS 1990) reported major bleeding adverse events in a total of 838 patients and meta‐analysis showed no statistically significant difference between antiplatelet and placebo (RR 1.73, 95% CI 0.51 to 5.83) (P = 0.38, Analysis 1.10) although the 95% confidence intervals were wide. For the two other adverse events, GI symptoms (dyspepsia) (RR 2.11, 95% CI 1.23 to 3.61) (P = 0.006, Analysis 1.11) and adverse events leading to cessation of therapy (RR 2.05, 95% CI 1.53 to 2.75) (P < 0.00001, Analysis 1.12), there were statistically significant increases in adverse events with antiplatelet therapy. For GI symptoms, subgroup analyses by class of antiplatelet showed a statistically significant increase in symptoms with both indobufen (RR 3.29, 95% CI 1.17 to 9.27) (P = 0.02) and ticlopidine (RR 2.40, 95% CI 1.82 to 3.17) (test of subgroup differences P < 0.00001).

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antiplatelet agent versus placebo, Outcome 10 Major bleeding.

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antiplatelet agent versus placebo, Outcome 11 GI symptoms (dyspepsia).

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antiplatelet agent versus placebo, Outcome 12 Early cessation of treatment.

Other secondary outcomes

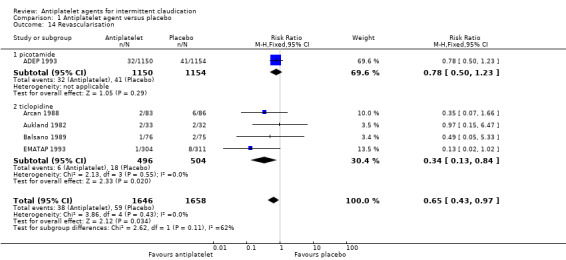

Pain free walking distance (PFWD) was reported in three trials (Coto 1989; Signorini 1988; Tonnesen 1993) and meta‐analysis showed a statistically significant increase in PFWD with antiplatelet therapy compared with placebo (MD 78.09, 95% CI 12.24 to 143.95) (P = 0.02, Analysis 1.13). Antiplatelet treatment also significantly reduced the need for revascularisation based on meta‐analysis of five trials (ADEP 1993; Arcan 1988; Aukland 1982; Balsano 1989; EMATAP 1993) (RR 0.65, 95% CI 0.43 to 0.97) (P = 0.03, Analysis 1.14). Amputation events were not significantly different between antiplatelet and placebo groups in meta‐analysis of two trials reporting this outcome (RR 0.84, 95% CI 0.38 to 1.86) (P = 0.67, Analysis 1.15 ). Only one trial (Coto 1989) reported effects of antiplatelet on ABPI (MD 0.04, 95% CI ‐0.00 to 0.08).

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antiplatelet agent versus placebo, Outcome 13 Pain Free Walking Distance.

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antiplatelet agent versus placebo, Outcome 14 Revascularisation.

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antiplatelet agent versus placebo, Outcome 15 Limb amputations.

2. Antiplatelet agent(s) versus aspirin

Two different antiplatelet agents (clopidogrel and picotamide) were compared with aspirin in two trials (CAPRIE 1996; DAVID 2004). Overall, 7661 patients were included from these two trials (3826 participants in the antiplatelet group, and 3835 in the aspirin group).

Primary outcomes

All cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality

Compared with aspirin, treatment with an alternative antiplatelet was associated with a significantly lower risk of all cause mortality (RR 0.73, 95% CI 0.58 to 0.93) (P = 0.01, Analysis 2.1). This effect, however, was not reflected in cardiovascular mortality, where there was no statistically significant difference between the alternative antiplatelet and aspirin groups (RR 0.74, 95% CI 0.48 to 1.15) (P = 0.18, Analysis 2.2).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Antiplatelet agent(s) versus aspirin, Outcome 1 All cause mortality.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Antiplatelet agent(s) versus aspirin, Outcome 2 Cardiovascular mortality (fatal stroke or MI).

Cardiovascular events

Meta‐analysis for total cardiovascular events (fatal and non‐fatal MI or stroke) showed a significantly lower risk of events in participants randomised to the alternative antiplatelet compared with aspirin (RR 0.81, 95% CI 0.67 to 0.98) (P = 0.03, Analysis 2.3). This was accounted for mainly by the significantly lower risk of non‐fatal MI with the alternative antiplatelet compared with aspirin (RR 0.65, 95% CI 0.47 to 0.89) (P = 0.008, Analysis 2.6). Total MI events were also significantly lower with the alternative antiplatelet compared with aspirin (RR 0.66, 95% CI 0.50 to 0.86) (P = 0.002, Analysis 2.4). Meta‐analyses for separate cardiovascular events showed no statistically significant difference between the alternative antiplatelet group and the aspirin group for fatal MI (RR 0.68, 95% CI 0.40 to 1.15) (P = 0.15, Analysis 2.5), total stroke (fatal and non‐fatal) (RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.34) (P = 0.93, Analysis 2.7), fatal stroke (RR 0.57, 95% CI 0.05 to 6.44) (P = 0.65, Analysis 2.8) or non‐fatal stroke (RR 1.03, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.39) (P = 0.86, Analysis 2.9).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Antiplatelet agent(s) versus aspirin, Outcome 3 Cardiovascular event (fatal and non‐fatal MI or stroke).

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Antiplatelet agent(s) versus aspirin, Outcome 6 Myocardial infarction (non‐fatal).

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Antiplatelet agent(s) versus aspirin, Outcome 4 Myocardial infarction (fatal and non‐fatal).

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Antiplatelet agent(s) versus aspirin, Outcome 5 Myocardial infarction (fatal).

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Antiplatelet agent(s) versus aspirin, Outcome 7 Stroke (fatal and non‐fatal).

2.8. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Antiplatelet agent(s) versus aspirin, Outcome 8 Stroke (fatal).

2.9. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Antiplatelet agent(s) versus aspirin, Outcome 9 Stroke (non‐fatal).

Secondary outcomes

Adverse events

Adverse events were not consistently reported by one trial (CAPRIE 1996) that recruited patients with polyvascular aetiology, so inclusion of these data in a meta‐analysis was not possible. The second study (DAVID 2004) reported major bleeding, GI symptoms and adverse events leading to cessation of therapy. Gastrointestinal symptoms (dyspepsia) in this single study were significantly increased in the aspirin group compared with the group receiving picotamide (RR 0.60, 95% CI 0.45 to 0.79) (P = 0.0004, Analysis 2.11). Risks for the other adverse events were not significantly different between the aspirin and picotamide groups (Analysis 2.10; Analysis 2.12).

2.11. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Antiplatelet agent(s) versus aspirin, Outcome 11 GI symptoms (dyspepsia).

2.10. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Antiplatelet agent(s) versus aspirin, Outcome 10 Major bleeding.

2.12. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Antiplatelet agent(s) versus aspirin, Outcome 12 Early cessation of treatment.

Other secondary events

Only one study (DAVID 2004) reported results for limb deterioration leading to amputation and this showed no statistically significant differences in risk ratio between aspirin and picotamide (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.25 to 4.00) (P = 0.99, Analysis 2.13).

2.13. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Antiplatelet agent(s) versus aspirin, Outcome 13 Amputation.

Discussion

Summary of main results

In this review, antiplatelet treatment was associated with a statistically significant reduction in all cause mortality compared with placebo in patients suffering from intermittent claudication (RR 0.76, 95% CI 0.60 to 0.98). When compared with aspirin, antiplatelet agent(s) other than aspirin were associated with a significantly lower risk of all cause mortality (RR 0.73, 95% CI 0.58 to 0.93).

Cardiovascular mortality was significantly reduced in trial participants treated with antiplatelet compared with placebo (RR 0.54, 95% CI 0.32 to 0.94), but data were only reported on this outcome by trials which used ticlopidine as the drug of intervention. When compared with aspirin, antiplatelet agent(s) other than aspirin were not associated with a significantly lower risk of cardiovascular mortality (RR 0.74, 95% CI 0.48 to 1.15).

Composite cardiovascular events (combined fatal and non‐fatal MI or stroke) appeared lower with antiplatelet treatment compared with placebo (RR 0.80, 95% CI 0.63 to 1.01) but this difference did not reach statistical significance.and there was no statistically significant difference in the risk of individual cardiovascular events i.e. total MI (fatal and non‐fatal), fatal MI, non‐fatal MI, total stroke (fatal and non‐fatal), fatal stroke or non‐fatal stroke, when antiplatelet was compared with placebo. Antiplatelet agent(s) other than aspirin were associated with a significantly lower risk of total cardiovascular events compared with aspirin (RR 0.81, 95% CI 0.67 to 0.98). This was mainly accounted for by the significantly lower risk of MI events (fatal and non‐fatal) (RR 0.66, 95% CI 0.50 to 0.86) and specifically non‐fatal MI (RR 0.65, 95% CI 0.47 to 0.89).

Adverse events (GI symptoms, specifically dyspepsia, and adverse events leading to cessation of therapy) were significantly more common in participants who were treated with antiplatelet agent compared with placebo. The risk of major bleeding was not significantly different between groups treated with antiplatelet and placebo, although data on this outcome were limited. Meta‐analysis for adverse events in trials comparing aspirin with antiplatelet agents other than aspirin was not performed due to lack of data.

Antiplatelet therapy significantly improved pain free walking distance when compared with placebo (MD 78.09, 95% CI 12.24 to 143.95). The risk of revascularisation was also significantly reduced by antiplatelet treatment compared with placebo (RR 0.65, 95% CI 0.43 to 0.97). The risk of amputation was not significantly different between antiplatelet treatment and placebo. Data were only available from one trial comparing antiplatelet agents other than aspirin with aspirin for risk of amputation and this did not show a statistically significant difference.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

This review included 12 trials on patients with IC (Fontaine Stage II). Subgroup analyses were performed to assess the effects of varying classes of antiplatelets.

All cause and cardiovascular mortality reporting varied between trials. Composite outcomes, for example "vascular deaths" were used in many studies. Although this has the benefit of reducing the size of the trial required to detect a statistically significant difference, it can reduce our ability to understand the precise impact of antiplatelet use in reducing mortality and morbidity. In addition, not all components within these composite outcomes are of equal importance (Cordoba 2010). For the purpose of this review, cardiovascular mortality was defined as death as a result of MI or stroke, and cardiovascular events was defined as fatal and non‐fatal MI and stroke, these definitions were employed by most of the included studies. ADEP 1993 did not report fatal and non‐fatal events separately and could therefore not be included in meta‐analyses for these individual outcomes.

All cause and cardiovascular mortality reporting was further complicated by the variable lengths of follow‐up. This review was therefore unable to determine a relative risk reduction specifically in relation to treatment length. The majority of the trials (Arcan 1988; Aukland 1982; Auteri 1995; Coto 1989; EMATAP 1993; Signorini 1988; Tonnesen 1993) involved follow‐up for up to a year. For the purpose of this review, cardiovascular mortality was defined as death as a result of myocardial infarction or stroke within 30 days of the event, and this definition was employed by most of the studies. The evidence for cardiovascular mortality should be interpreted as 30‐day risk ratio or relative risk ratio (RRR).

The evidence for aspirin despite its widespread use remains unsubstantiated due to the lack of trials which fulfilled the inclusion criteria specifically for this review. The majority of evidence was derived from historical trials incorporating ticlopidine, which has since been supplanted by another thienopyridine (clopidogrel) due to the increased risk of neutropaenia and thrombocytopaenic purpura (Bennett 1999; Moloney 1993). As a result, ticlopidine is no longer widely used in Europe, the United States of America and Australasia. As thienopyridines, both clopidogrel and ticlopidine are prodrugs that are converted in vivo to pharmacologically active metabolites that inhibit platelet function after irreversibly binding to the platelet ADP P2Y12 receptors. Clopidogrel has been shown to be at least as efficacious as ticlopidine but with better tolerability and fewer side‐effects (Bhatt 2002; Casella 2003; Sudlow 2009). For this reason it is now used in preference to ticlopidine in most countries. We have extrapolated the results of ticlopidine to encompass the thienopyridine group of antiplatelets due to their similar efficacy and mechanism of action. The results of this review and its applicability must therefore be interpreted with this context in mind.

Four large RCTs were excluded (CLIPS 2007; CHARISMA 2009; Fowkes 2010; POPADAD 2008) as they recruited participants with asymptomatic PAD. Both Fowkes 2010 and POPADAD 2008 only included asymptomatic participants.

Further trials were excluded because the study populations included a mixture of Fontaine stage patients and the data by the different Fontaine stages were not available. The review authors propose therefore that for future updates of this review, the review is broadened to include all stages of PAD including stage I (asymptomatic patients).

Quality of the evidence

This review provides a critical, quantitative review of antiplatelet agents in patients with IC. This review examined 12 different trials with 12,168 participants with varying methodology and outcome reporting. Apart from newer studies, most have unclear methods of randomisation and allocation concealment. There is a high rate of early discontinuation of treatment in both arms of the included trials which may potentially affect the final results. These cases were often not clearly reported and it was uncertain whether they were accounted for in studies published in the 1980s and early 1990s.

Potential biases in the review process

This review was limited to RCTs and excluded controlled clinical trials to limit the potential for bias. Most studies were described by their authors as randomised without details being given about the randomisation sequence generation or the type of precautions taken in relation to concealment of allocation. Incomplete outcome data was addressed in the majority of trials.

The main risk of bias from the review process was contributed by the lack of clear definition or variations in the definition of outcomes in the studies reviewed. One example of inconsistencies is that some trials incorporated deaths due to pulmonary embolism and "any deaths that were not clearly non‐vascular" as "vascular deaths". For the purpose of this review, the review authors have strictly employed deaths due to MI and ischaemic stroke to define cardiovascular deaths. Other definitions vary between studies, for example, the definition for major bleeding was not always provided in the studies. Some studies only reported "bleeding", without any further details, while others provided a list of different types of bleeding. For the purpose of this review, a pragmatic approach was taken; the review authors included data which were labelled as "major bleeding", or when there was an attempt to distinguish more serious bleeding events from the minor ones. If data on individual components were available, these were also extracted and added up for the major bleeding outcomes.

In addition, a number of studies were excluded because patients with different stages of PAD (either Fontaine stage I participants or Fontaine stage III and IV patients) were included in the study populations and the results for the different stages were not presented separately.

The risk of data collection bias was reduced by independent data extractions by two review authors, and the use of predefined outcomes in our review protocol. Where there were inconsistencies in the data extracted, these were discussed between the review authors to reach an agreement.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

This review demonstrated statistically significant risk reductions in terms of all cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality with antiplatelet treatment in patients with IC. This was consistent with the Antithrombotic Trialists' Collaboration (ATC 2002) report, which similarly showed a proportional reduction of 23% in serious vascular events in patients with PAD who were treated with antiplatelet agents compared with placebo. This review only included patients who had received at least three months of therapy as opposed to four weeks of treatment described in the ATC trial (ATC 2002) therefore reducing the potential of bias from under‐reporting from a short period of treatment, and also allowing real assessment of antiplatelet agents and their longer term impact on mortality.

Basili 2010 reviewed the effects of antiplatelets on the composite outcome of vascular events (non‐fatal MI, non‐fatal stroke of ischaemic or unknown aetiology or vascular death) in patients with IC (surgical series excluded) and found an odds ratio of 0.839 (95% CI 0.73 to 0.97) in favour of antiplatelet treatment compared with placebo. This meta‐analysis from Basili and colleagues (Basili 2010) also found that even though aspirin reduced vascular events, this was not statistically significant.

Another meta‐analysis of aspirin in PAD patients (Berger 2009) also showed no significant benefit of aspirin on cardiovascular events when compared with placebo or control. This review, however, showed that aspirin did accord a significant reduction in the risk of non‐fatal stroke.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Antiplatelet agents have proven efficacy in patients with IC in terms of reduction in all cause and cardiovascular mortality. The review was limited to patients with stage II Fontaine and cannot be extrapolated to patients with stage I, III or IV Fontaine, or patients requiring surgical intervention (endovascular treatment, surgical bypass or amputation). The results were highly influenced by trials which used ticlopidine (a thienopyridine) as the intervention antiplatelet, but this agent is no longer available in many countries due to the availability of clopidogrel which has an improved safety profile. When aspirin was compared with other antiplatelet agent(s), there was no evidence that aspirin has any benefit over picotamide or clopidogrel. In fact, there was a reduction in risk of all cause mortality in patients treated with an alternative antiplatelet compared with those in the aspirin group. There is a need to reconsider the use of aspirin as the drug of choice in most clinical practice guidelines in view of the lack of evidence on aspirin compared with the evidence for the thienopyridine class of antiplatelet agents.

Compared with placebo, antiplatelet agents have a significant risk of adverse events (GI side‐effects, specifically dyspepsia and adverse events leading to cessation of therapy) and both healthcare professionals and patients need to be aware of this potential harm. Interestingly, there was no statistically significant difference in the risk of major bleeding between antiplatelet treatment and placebo, but the latter outcome has to be interpreted with caution as it was only reported in only two trials with a relatively small number of participants and the result demonstrated wide 95% confidence intervals.

Implications for research.

The methodology of RCTs in this area of research needs to be better standardised in order to allow for future meta‐analysis. Power calculations should be performed to ensure sufficient patient recruitment. The authors recommend that future trialists should consistently report on all cause and cardiovascular mortality. For the latter outcome, this should be defined as death within 30 days of either MI or ischaemic stroke. Follow‐up length should be increased to at least one year to allow a consistent reporting of risk reduction which would be clinically meaningful. Risk from cancer deaths have always been defined in relation to time i.e. either one‐year, three‐year or five‐year, and it is time similar reporting in patients with IC is performed. Separate reporting of fatal and non‐fatal MI and stroke would be helpful to allow clear distinction of the effects of antiplatelet agents on these morbidities, even when a composite outcome is used as the primary outcome.

There was no consistent definition of major bleeding and the review authors would strongly recommend using the following for future trials:

death due to major bleeding,

a decrease in haemoglobin concentration of 2g/dL or more,

transfusion of at least 2 units of blood,

bleeding from a retroperitoneal, intracranial, or intraocular site,

a serious or life‐threatening clinical event,

requiring surgical or medical intervention.

Due to the paucity of data on use of aspirin and its widespread use in the western world, there is an urgent need for multicentre trials to examine the effects of aspirin in patients with IC.

History

Protocol first published: Issue 1, 1999 Review first published: Issue 11, 2011

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 3 November 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 13 November 2003 | Amended | A protocol on this topic was originally published in Issue 1, 1999 of The Cochrane Library by Professor David Moher and his team. Mr Peter Robless has now taken over the review and has amended the protocol. |

Notes

August 2003: A protocol on this topic was originally published in Issue 1, 1999 of The Cochrane Library by Professor David Moher and his team. Mr Peter Robless and colleagues have taken over the review.

Acknowledgements

A protocol and draft review of this topic was originally written by a team led by Dr David Moher. The authors would like to thank the personnel from Cochrane Peripheral Vascular Diseases Review group, especially Marlene Stewart and Karen Welch for their invaluable assistance and advice.

Appendices

Appendix 1. CENTRAL search strategy

| #1 | MeSH descriptor Platelet Aggregation Inhibitors explode all trees | 7499 |

| #2 | MeSH descriptor Platelet Activation explode all trees | 1670 |

| #3 | (antiplatelet* or anti‐platelet* or antiaggreg* or anti‐aggreg*):ti,ab,kw | 1661 |

| #4 | ((platelet or thromboxane or thrombocyte or cyclooxygenase or cyclo‐oxygenase or phosphodiesterase or fibrinogen or PAR‐1) near3 (antagonist or inhibitor)):ti,ab,kw | 5439 |

| #5 | (gp* or glycoprotein* or protease or P2Y12 or TXA2) near3 (inhibit* or antag*):ti,ab,kw | 1654 |

| #6 | (aspirin* or nitroaspirin or ASA or "acetyl salicylic acid*" or "acetylsalicylic acid" or "acetyl‐salicylic acid"):ti,ab,kw | 12752 |

| #7 | (carbasalate calcium or indobufen or triflusal or Disgren or Grendis or Triflux):ti,ab,kw | 158 |

| #8 | (GR144053 or GR‐144053 or abciximab or tirofiban* or eftifibatid or eptifibatide or ReoPro or Integrilin* or Aggrastat ):ti,ab,kw | 832 |

| #9 | (thienopyrid* or thiophen* or clopidogrel or Plavix or Iscover or prasugrel or Effient or ticlopidine or Ticlid or Ticagrelor or Cangrelor or Elinogrel):ti,ab,kw | 2431 |

| #10 | cilostazol or Pletal or d?pyridamol? or Persantin or Triflusal or picotamide:ti,ab,kw | 1442 |

| #11 | (picotinamide or suloctidil or sulphinpyrazone):ti,ab,kw | 83 |

| #12 | (satigrel or sarpolgrelate or kbt3022 or kbt‐3022 or isbogrel or cv4151 or cv‐4151):ti,ab,kw | 13 |

| #13 | (epoprostenol* or iloprost* or ketanserin* or milrinone* or mopidamol*):ti,ab,kw | 1313 |

| #14 | (Dispril or Albyl* or Ticlid* or Persantin* or Plavix or Aggrenox or Plasugrel or Ticagrelor or Cangrelor or SCH 530348 or SCH530348 or Ozagrel or OKY046 or OKY‐046):ti,ab,kw | 182 |

| #15 | E5555 or NCX 4016 or NCX4016 or PRT060128 or PRT 060128 or S18886 or S 18886 | 8 |

| #16 | terutroban | 6 |

| #17 | PRT060128 or PRT 060128 | 0 |

| #18 | AZD6140 or AZD 6140 | 10 |

| #19 | MeSH descriptor Arteriosclerosis, this term only | 902 |

| #20 | MeSH descriptor Arteriolosclerosis, this term only | 0 |

| #21 | MeSH descriptor Arteriosclerosis Obliterans, this term only | 68 |

| #22 | MeSH descriptor Atherosclerosis, this term only | 320 |

| #23 | MeSH descriptor Arterial Occlusive Diseases, this term only | 745 |

| #24 | MeSH descriptor Intermittent Claudication, this term only | 671 |

| #25 | MeSH descriptor Peripheral Vascular Diseases, this term only | 562 |

| #26 | (atherosclero* or arteriosclero* or PVD or PAOD or PAD):ti,ab,kw | 5930 |

| #27 | (arter* or vascular or vein* or veno* or peripher*) near (occlus* or steno* or obstuct* or lesio* or block*):ti,ab,kw | 6218 |

| #28 | (peripheral near3 dis*):ti,ab,kw | 2430 |

| #29 | (claudic* or hinken*):ti,ab,kw | 1211 |

| #30 | (#19 OR #20 OR #21 OR #22 OR #23 OR #24 OR #25 OR #26 OR #27 OR #28 OR #29) | 13432 |

| #31 | (#1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12 OR #13 OR #14 OR #15 OR #16 OR #17 OR #18) | 23377 |

| #32 | (#30 AND #31) | 1625 |

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Antiplatelet agent versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 All cause mortality | 5 | 3926 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.76 [0.60, 0.98] |

| 1.1 picotamide | 1 | 2304 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.91 [0.50, 1.66] |

| 1.2 ticlopidine | 4 | 1622 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.73 [0.56, 0.96] |

| 2 Cardiovascular mortality (fatal stroke or MI) | 4 | 1622 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.54 [0.32, 0.93] |

| 2.1 ticlopidine | 4 | 1622 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.54 [0.32, 0.93] |

| 3 Cardiovascular event (fatal and non‐fatal MI or stroke) | 5 | 3926 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.80 [0.63, 1.01] |

| 3.1 picotamide | 1 | 2304 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.84 [0.47, 1.50] |

| 3.2 ticlopidine | 4 | 1622 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.79 [0.61, 1.02] |

| 4 Myocardial infarction (fatal and non‐fatal) | 5 | 3926 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.84 [0.63, 1.12] |

| 4.1 picotamide | 1 | 2304 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.82 [0.39, 1.69] |

| 4.2 ticlopidine | 4 | 1622 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.85 [0.62, 1.16] |

| 5 Myocardial infarction (fatal) | 4 | 1622 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.57 [0.31, 1.05] |

| 5.1 ticlopidine | 4 | 1622 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.57 [0.31, 1.05] |

| 6 Myocardial infarction (non‐fatal) | 4 | 1622 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.01 [0.69, 1.48] |

| 6.1 ticlopidine | 4 | 1622 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.01 [0.69, 1.48] |

| 7 Stroke (fatal and non‐fatal) | 5 | 3926 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.71 [0.45, 1.13] |

| 7.1 picotamide | 1 | 2304 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.89 [0.35, 2.30] |

| 7.2 ticlopidine | 4 | 1622 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.66 [0.39, 1.12] |

| 8 Stroke (fatal) | 4 | 1622 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.33 [0.07, 1.64] |

| 8.1 ticlopidine | 4 | 1622 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.33 [0.07, 1.64] |

| 9 Stroke (non‐fatal) | 4 | 1622 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.74 [0.42, 1.30] |

| 9.1 ticlopidine | 4 | 1622 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.74 [0.42, 1.30] |

| 10 Major bleeding | 2 | 838 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.73 [0.51, 5.83] |

| 10.1 ticlopidine | 2 | 838 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.73 [0.51, 5.83] |

| 11 GI symptoms (dyspepsia) | 9 | 3818 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.11 [1.23, 3.61] |

| 11.1 indobufen | 2 | 352 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 3.29 [1.17, 9.27] |

| 11.2 picotamide | 2 | 2344 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.94 [0.75, 1.18] |

| 11.3 ticlopidine | 4 | 1000 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.40 [1.82, 3.17] |

| 11.4 trifusal | 1 | 122 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 6.41 [0.79, 51.64] |

| 12 Early cessation of treatment | 8 | 4388 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.05 [1.53, 2.75] |

| 12.1 indobufen | 1 | 300 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.46 [0.47, 4.49] |

| 12.2 picotamide | 2 | 2344 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.45 [0.73, 2.84] |

| 12.3 ticlopidine | 4 | 1622 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.35 [1.66, 3.31] |

| 12.4 trifusal | 1 | 122 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.07 [0.07, 16.69] |

| 13 Pain Free Walking Distance | 3 | 329 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 78.09 [12.24, 143.95] |

| 13.1 indobufen | 2 | 294 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 196.87 [‐85.58, 479.32] |

| 13.2 picotamide | 1 | 35 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 38.70 [2.68, 74.72] |

| 14 Revascularisation | 5 | 3304 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.65 [0.43, 0.97] |

| 14.1 picotamide | 1 | 2304 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.78 [0.50, 1.23] |

| 14.2 ticlopidine | 4 | 1000 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.34 [0.13, 0.84] |

| 15 Limb amputations | 2 | 2991 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.84 [0.38, 1.86] |

| 15.1 picotamide | 1 | 2304 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.80 [0.22, 2.98] |

| 15.2 ticlopidine | 1 | 687 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.86 [0.32, 2.35] |

Comparison 2. Antiplatelet agent(s) versus aspirin.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 All cause mortality | 2 | 7661 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.73 [0.58, 0.93] |

| 1.1 clopidogrel vs aspirin | 1 | 6452 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.78 [0.60, 1.02] |

| 1.2 picotamide vs aspirin | 1 | 1209 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.55 [0.31, 0.98] |

| 2 Cardiovascular mortality (fatal stroke or MI) | 2 | 7661 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.74 [0.48, 1.15] |

| 2.1 clopidogrel vs aspirin | 1 | 6452 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.83 [0.51, 1.35] |

| 2.2 picotamide vs aspirin | 1 | 1209 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.46 [0.16, 1.31] |

| 3 Cardiovascular event (fatal and non‐fatal MI or stroke) | 2 | 7661 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.81 [0.67, 0.98] |

| 3.1 clopidogrel vs aspirin | 1 | 6452 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.79 [0.64, 0.97] |

| 3.2 picotamide vs aspirin | 1 | 1209 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.94 [0.57, 1.54] |

| 4 Myocardial infarction (fatal and non‐fatal) | 2 | 7661 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.66 [0.50, 0.86] |

| 4.1 clopidogrel vs aspirin | 1 | 6452 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.63 [0.47, 0.85] |

| 4.2 picotamide vs aspirin | 1 | 1209 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.79 [0.41, 1.55] |

| 5 Myocardial infarction (fatal) | 2 | 7661 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.68 [0.40, 1.15] |

| 5.1 clopidogrel vs aspirin | 1 | 6452 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.67 [0.37, 1.21] |

| 5.2 picotamide vs aspirin | 1 | 1209 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.72 [0.23, 2.25] |

| 6 Myocardial infarction (non‐fatal) | 2 | 7661 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.65 [0.47, 0.89] |

| 6.1 clopidogrel vs aspirin | 1 | 6452 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.62 [0.44, 0.88] |

| 6.2 picotamide vs aspirin | 1 | 1209 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.84 [0.36, 1.92] |

| 7 Stroke (fatal and non‐fatal) | 2 | 7661 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.01 [0.76, 1.34] |

| 7.1 clopidogrel vs aspirin | 1 | 6452 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.99 [0.73, 1.34] |

| 7.2 picotamide vs aspirin | 1 | 1209 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.17 [0.55, 2.51] |

| 8 Stroke (fatal) | 2 | 7661 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.57 [0.05, 6.44] |

| 8.1 clopidogrel vs aspirin | 1 | 6452 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.38 [0.55, 3.42] |

| 8.2 picotamide vs aspirin | 1 | 1209 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.11 [0.01, 2.07] |

| 9 Stroke (non‐fatal) | 2 | 7661 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.03 [0.76, 1.39] |

| 9.1 picotamide vs aspirin | 1 | 1209 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.76 [0.74, 4.16] |

| 9.2 clopidogrel vs aspirin | 1 | 6452 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.95 [0.69, 1.31] |

| 10 Major bleeding | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 10.1 picotamide vs aspirin | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 11 GI symptoms (dyspepsia) | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 11.1 picotamide vs aspirin | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 12 Early cessation of treatment | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 12.1 picotamide vs aspirin | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 13 Amputation | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 13.1 picotamide vs aspirin | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

ADEP 1993.

| Methods | Randomised, double‐blinded, controlled trial, stratified by centre. Multicentre (120 Italian centres) study. Enrolment started in January 1989. Power calculation: Based on detection of 25% reduction of "major and minor events" compared with untreated patients (estimated as 14% in 18 months from PACK study), the number of patients required would be 1100 for α = 0.05 and β = 0.20, one‐tailed test. The number of patients enrolled increased by 10% to account for lost to follow‐up. ITT analysis: performed. Single‐blinded run‐in period of one month on placebo treatment. Follow‐up length: 18 months. |

|

| Participants | Number of patients randomised: 2304. 1150 (picotamide) versus 1154 (placebo). Male : female ratio = 84.9% male (picotamide); 83.6% male in (placebo). Age (mean with SD): 63.4 ± 7.31 (picotamide); 62.9 ± 7.45 (placebo). Inclusion criteria: consecutive patients up to age of 80 suffering from PVD screened. PVD was defined according to one or more of the following criteria: patients with claudication defined as leg pain on walking that disappeared in five minutes on standing and an ABPI by Doppler ultrasonography ≤0.85 in the posterior and anterior tibial artery of one foot; or patients with claudication with previous amputation or reconstructive vascular surgery. Exclusion criteria: treatment with antiplatelet drugs such as aspirin, ticlopidine, dipyridamole, indobufen and other NSAIDs, anticoagulants; pain at rest; skin lesions; myocardial infarction, stroke, or survival intervention in the previous three months; stable or unstable angina requiring aortocoronary bypass or angioplasty; liver insufficiency (prothrombin activity ≤ 40%); serious renal disorders (serum creatinine ≥2.8 mg%) and other conditions resulting in a life expectancy of < 2 years. |

|

| Interventions | Intervention: picotamide 300 mg tds. Control: placebo tds. |

|

| Outcomes | All cause mortality. Cardiovascular mortality. Myocardial infarction (fatal and non‐fatal). Stroke (fatal and non‐fatal). Adverse events leading to cessation of therapy. Progression of disease resulting in need for revascularisation. Amputation (above ankle). Adverse events: adverse events leading to cessation of therapy, gastrointestinal symptoms. |

|

| Notes | Source of funding: Samil S.p.A. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "randomisation lists were generated by an automatic procedure developed expressly to have two balanced groups in each centre". |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not stated. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "double‐blind study", "placebo used", "appearance and taste of the capsules were identical". |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "double‐blind study", "qualitative evaluation of selected events validated under blinded conditions by an independent review committee". Comment: it was not stated explicitly if assessors were blinded to the randomisation arm. Probably done. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | Lost to follow‐up: 57/1150(4.9%) (picotamide), 59/1154 (5.1%) (placebo). Withdrawal from study: 48/1150 (4.2%) (picotamide), 29/1154 (2.5%) (placebo). Comment: rate of withdrawal is higher in picotamide group (P = 0.02, Chi2 test). Rate of patients lost to follow‐up were comparable (P = 0.86, Chi2 test). |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Outcomes clearly listed and defined, all reported clearly in a table. |

Arcan 1988.

| Methods | Randomised, double blinded, placebo controlled trial. Multicentre (29 French and 1 Swiss) study. Study period: December 1982 ‐ October 1985. Power calculation: 204 patients required, based on a "success" rate of 30% with placebo increased to 50% with ticlopidine. The hypothesis under investigation was set one‐tailed with a type I error of 0.05 and a statistical power of 0.90. ITT analysis: performed. Four week, single‐blind placebo run in. Follow‐up length: 24 weeks. |

|

| Participants | Number of patients: 169. 83 (ticlopidine) versus 86 (placebo). Male : female ratio = 154 : 15. Age (mean): 59.87 ± 1.03 (ticlopidine); 58.53 ± 0.98 (placebo). Inclusion criteria: symptomatic intermittent claudication for at least 12 months and had to present a walking distance assessed by treadmill testing (3.2 km/h, 10% slope, ambient temperature 20‐24 oC) of between 50 and 300 meters. Patient was included if the relative variation of the walking distance was within 25% of initial values at the end of the run‐in period. A recent confirmation of obstructive arterial disease was required by either angiography (< 6 months) or Doppler studies (< 3 months). Exclusion criteria: patient less than 35 or older than 75 years old, stage III or IV Fontaine disease, purely diabetic arteriopathy, vascular surgery within the past six months or planned within the next six months, severe hypertension not adequately controlled by treatment, need for treatment with anti‐inflammatory or anti‐coagulant or vasodilating agents, any contra‐indication to ticlopidine, hepatic or renal disease, and poor vital prognosis. |

|

| Interventions | Intervention: ticlopidine 250 mg bd. Control: placebo bd. |

|

| Outcomes | All cause mortality. Cardiovascular mortality. Cardiovascular events (MI, stroke or TIA). Walking distance: total and pain free walking distance (data presented in graphical form). Adverse events: adverse events leading to cessation of therapy; GI symptoms (dyspepsia). Need for revascularisation. |

|

| Notes | Trial enrolment terminated early because of persistence of a much slower recruitment rate than expected. Source of funding: not stated. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "An academic audit centre...issued the randomisation list". Comment: However, it was unclear how sequence generation was conducted. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "An academic audit centre, independent of the sponsor and clinical investigators, was established, to implement an external quality control. It participated in all administrative commitment. It issued the randomisation list". Comment: Unclear how list was concealed. |