Abstract

Introduction

Allogeneic stem cell transplantation (alloSCT) has become available for elderly patients or for patients with comorbidities by introduction of reduced-intense conditioning. Comorbidity-related prognosis after alloSCT can be estimated by the hematopoietic cell transplantation comorbidity index (HCT-CI).

Material and Methods

The charts from 85 patients who have undergone 90 alloSCTs between 1999 and 2011 were analysed. Most patients received a dose-reduced conditioning and a graft from an unrelated donor. Patients were stratified for age, HCT-CI, cGvHD versus no cGvHD, and a modified HCT-CI with a further split high-risk score.

Results

Age over 60 years did not affect the outcome. Manifestation of cGvHD improved the prognosis significantly. An additional stratification of the high-risk group of the HCT-CI revealed that even a fraction of these patients can have considerable benefit from an alloSCT. Furthermore, this high-risk collective could be clearly discriminated into two groups with different outcomes.

Conclusions

The investigation confirms that age is no absolute risk factor for alloSCT and demonstrates the heterogeneity of the high-risk group of the HCT-CI. A comprehensive investigation of an additional stratification is suggested. Furthermore, the authors encourage early withdrawal of immunosuppression, even in elderly patients and patients with comorbidities to permit graft-versus-leukaemia/lymphoma, since cGvHD is associated with a significantly better prognosis.

Keywords: Allogeneic stem cell transplantation, Elderly, Comorbidity, Graft-versus-leukaemia effects

Introduction

Haematological malignancies at high risk or in higher remission are often associated with an unfavourable prognosis and a hopeless course of disease. Allogeneic stem cell transplantation (alloSCT) might be curative in this otherwise fatal situation (Appelbaum 2001; Baron and Storb 2004). However, this treatment approach is associated with a considerable morbidity and mortality due to toxicity of conditioning regimens, infections and acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease (GvHD) (Cutler et al. 2001; Akpek et al. 2003; Vogelsang 1993; Lee et al. 2002). This is particularly true for classical myeloablative conditioning (MAC) regimens including busulphan (16 mg/kg) or total body irradiation (TBI) (12 Gy) in conjunction with cyclophosphamide (120 mg/kg). These regimens combine a high antineoplastic activity with an intensive immunosuppression to permit engraftment of donor haemopoiesis; however, their application may be associated with an intensive toxicity such as mucositis or organ damages, e.g. of liver, lungs and heart (Zander et al. 1997). In consequence, MAC may be ineligible for patients with organ impairment, a history of intensive antineoplastic therapy, severe infectious complications or for elderly patients. To address this problem, a variety of dose-reduced conditioning regimens have been developed. The intensity of these protocols has a wide variation, ranging from ‘toxicity-reduced’ protocols (e.g. treosulfan/fludarabine) over ‘reduced-intense conditioning’ (busulphan 8–10 mg/kg + fludarabine) to so-called minimal conditioning consisting of 2-Gy TBI alone (Baron and Storb 2004; Niederwieser et al. 2003, 2006). In addition, the allogeneic graft-versus-leukaemia effect and the therapy of residual disease with donor lymphocyte infusions were described (Kolb et al. 2004).

These developments made alloSCT suitable as a curative therapy for elderly and heavily pre-treated patients, and the historic age limit of 55–60 years for alloSCT has fallen (Corradini et al. 2002; Shapira et al. 2007). Since elderly patients show a wide variation in biological fitness, presence of chronic diseases and organ function, Sorror et al. developed a risk score to assess prior the probability of non-relapse mortality (NRM) after transplantation (hematopoietic cell transplantation comorbidity index, HCT-CI) (Sorror et al. 2007a). The interest in the publications by Sorror et al. has mainly focused on the observation that the overall survival after alloSCT of patients with a good-to-intermediate comorbidity index is comparable to that of younger patients. Age should consequently not be a contraindication for alloSCT itself (Shapira et al. 2007). However, also the survival curve of patients with high-risk HCT-CI suggests some survival benefit by alloSCT compared to conventional therapy for these patients. To address the question, if a stratification of the high-risk group might be helpful to identify eligible candidates for alloSCT, we analysed our results of transplantation of elderly patients according to the HCT-CI.

Patients and methods

Patients and diagnoses

Eighty-six patients aged ≥55 years were treated with an allogeneic haemopoietic stem cell transplantation between 1999 and 2011 at Greifswald University Medical Centre. The charts from 85 patients were available for this retrospective analysis. Three patients were re-transplanted, and a further person with AML got three stem cell transplantations. Therefore, a total of 90 transplantations could be analysed. Re-transplantations were considered as single cases in this analysis. Thirty-four of 85 (40 %) patients were female and 51 (60 %) male. The median age was 61 (range 55–72) years. 53 % were older than 60 years (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Patients | |

| Total, n (%) | 85 (100 %) |

| Female, n (%) | 34 (40 %) |

| Male, n (%) | 51 (60 %) |

| Age | Median 61 years, range 55–72, >60 years: n = 48 (53 %) |

| Re-transplantations | N = 5 (twice: one patient, once: three patients) |

| Diagnoses | |

| AML | N = 43 (48 %), (relapsed = 9, secondary = 19) |

| ALL | N = 3 (3 %) |

| MDS | N = 9 (10 %) |

| MM | N = 10 (11 %) |

| NHL indolent | N = 6 (7 %) (IC = 2, CLL = 3, CLL/plasmocytoid = 1) |

| NHL aggressive | N = 8 (9 %) (MCL = 5, tFL = 2, Burkitt = 1) |

| PTCL | N = 3 (3 %) |

| CML | N = 4 (4 %) |

| Other | N = 4 (4 %) (haemophagocytic syndrome = 1, CD4+/CD56+-intradermal neoplasia = 1, RCC = 1, OMF = 1) |

| Remission state prior to alloSCT, n (%) | |

| CR | 41 (46 %) |

| PR | 26 (29 %) |

| SD | 9 (10 %) |

| PD | 13 (14 %) |

| N/A | 1 (1 %) |

AML acute myeloid leukaemia, ALL acute lymphoblastic leukaemia, CML chronic myeloic leukaemia, MCL mantle cell lymphoma, MDS myelodysplastic syndrome, MM multiple myeloma, NHL non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, PTCL peripheral T-cell lymphoma, RCC renal cell cancer, OMF osteomyelofibrosis, CR complete remission, PR partial remission, SD stable disease, PD progressive disease

The underlying disease was acute myeloid leukaemia in 43 cases (48 %). In nine cases, the leukaemia was in a higher remission than CR#1 and 19 from these 43 patients suffered from secondary leukaemia. Ten (11 %) patients were grafted because of multiple myeloma and nine (10 %) for myelodysplastic syndrome. The diagnoses were aggressive and indolent non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in eight (9 %) and six (7 %) cases each. Four patients (4 %) suffered from chronic myeloid leukaemia and one (1 %) patient each from haemophagocytic syndrome, renal cell cancer, blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm and primary myelofibrosis (Table 1). In 82/90 transplantations, a high-risk situation was defined by the remission state, by response of disease or by cytogenetic alterations.

Forty-one (46 %) and twenty-six (29 %) patients were grafted in complete and partial remission, respectively. Nine (10 %) patients had stable disease and 13 (14 %) patients progressive disease at start of the conditioning treatment before haemopoietic cell transplantation (Table 1).

Haemopoietic cell transplantation comorbidity index (HCT-CI)

The HCT-CI was evaluated prior to alloSCT according to the publications by Sorror et al. and shown in Table 2 (Sorror et al. 2007a). In one case, the HCT-CI could not be determined retrospectively from the charts. The median HCT-CI was 3 (0–9), and 45 patients were scored to the high-risk group.

Table 2.

Haemopoietic cell transplantation comorbidity index

| HCT-CI, n (%) | HCT-CI score/groups, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 18 (20) | Low (0) | N = 18 (20) |

| 1 | 14 (16) | Intermediate (1–2) | N = 26 (29) |

| 2 | 12 (14) | ||

| 3 | 16 (18) | High (≥3) | N = 45 (51 %) |

| 4 | 10 (11) | ||

| 5 | 4 (5) | ||

| 6 | 8 (9) | ||

| 7 | 3 (3) | ||

| 8 | 3 (3) | ||

| 9 | 1 (1) | ||

| Median | 3 | ||

| Range | 0–9 | ||

| Modified scoring according to the HCT-CI—age related | ||

|---|---|---|

| Score | Patients ≤60 years | Patients >60 years |

| 0–2 | N = 19 (46 %) | N = 25 (52 %) |

| 3–5 | N = 13 (32 %) | N = 17 (35 %) |

| 6–9 | N = 9 (22 %) | N = 6 (13 %) |

N = 90, in one case, the HCT-CI could not be evaluated retrospectively

Transplant biology, conditioning regimen and transplantation

Ninety alloSCTs from matched unrelated (n = 75, 83 %) and related donors (n = 15, 17 %) were mainly performed with G-CSF-mobilised peripheral stem cells (n = 87, 97 %). Three transplantations (3 %) were carried out with bone marrow aspirations. The stem cell grafts consisted of 6.62 (median range 1.5–19.11) × 106 CD34+ cells and the marrow grafts of 2.93 (2.28–7.9) × 106 CD34+ cells per kg recipient’s bodyweight. A HLA match less than 10/10 had to be accepted in 26 cases. In fourteen transplantations (16 %), a CMV+ patient was grafted from a CMV− donor, 45 (50 %) of the reported cases were without AB0 disparity, and in 14 (16 %) transplantations, there was a ‘female-to-male’ constellation.

In 42 (47 %) of the transplantations, a MAC protocol basing on busulphan (12–16 mg/kg) or treosulfan (36–42 g/m2) was applied (Zander et al. 1997; Casper et al. 2004). The busulphan dose is given for oral administration, and the i.v. equivalent dose was decreased by 20 %. Reduced-intense conditioning was used in 10 (11 %) cases. Given was either busulphan8mg/kg (n = 2, 2 %) or (n = 7, 8 %) in conjunction with fludarabine. One (1 %) patient was conditioned according to the FLAMSA protocol (Schneidawind et al. 2013). Non-MAC using TBI of 2 Gy or cyclophosphamide in conjunction with fludarabine was applied in 38 (42 %) transplantations (Niederwieser et al. 2003). Conditioning regimens are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Conditioning regimens

| Regimen | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Busulphana16mg/kg) + cyclophosphamide120mg/kg (n = 1 +VP-1630mg/kg) | 9 | 10 |

| Busulphana12–14mg/kg) + fludarabine | 2 | 2 |

| Busulphana8mg/kg) + fludarabine | 2 | 2 |

| + fludarabine (n = 1: + thiotepa10mg/kg) | 31 | 34 |

| Cyclophosphamide120mg/kg + fludarabine | 1 | 1 |

| + fludarabine | 7 | 8 |

| TBI2Gy + fludarabine | 37 | 41 |

| FLAMSA | 1 | 1 |

Fludarabine was given in doses between 75 mg and 180 mg/m2

ap.o. dose; the i.v. equivalent dose was 80 %, where applicable

GvHD prophylaxis, supportive care and haematological recovery

GvHD prophylaxis after transplantation was performed with cyclosporine-A and short-course methotrexate. Cyclosporine-A in association with mycophenolate mofetil was given after conditioning with TBI2Gy/fludarabine conditioning (Bolwell et al. 2004; Niederwieser et al. 2003). In general, it was scheduled to discontinue GvHD prophylaxis between day +100 and lately +180, the latter after MAC.

Third-generation quinolones were used as antibacterial prophylaxis. Systemic antifungal prophylaxis was initiated with fluconazole and switched at day +1 to either itraconazole or voriconazole. Also, metronidazole for anaerobic gut decontamination was initiated at day +1. Quinolones were discontinued after engraftment or at initiation of broad-spectrum antibiosis for treatment of infections. Metronidazole was discontinued at day +30, and antifungal prophylaxis was given until day +70, depending on the absence of GvHD. All patients received aciclovir from day +1 at least until day +30 to prevent reactivation of herpes simplex virus. Pneumocystis jirovecii prophylaxis was conducted until day +180 either with TMP-SMZ or with aerosolised pentacarinate (Krüger et al. 2005).

Acute and chronic GvHD was graded and treated according to international standard (Glucksberg et al. 1974; Vogelsang 1993). Freedom from GvHD was calculated using log-rank test and Kaplan–Meier analysis. Events were here the onset of either acute or chronic GvHD or death. Overall survival and relapse-free survival were calculated using the log-rank test and the Kaplan–Meier analysis. For the calculation of overall survival and progression-free survival intervals, relapse and progress of the underlying disease or death were defined as events.

Statistics

Data were collected using the computer software MS Office (Microsoft, Munich, Germany) and analysed with WinStat (www.winstat.com) or GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

Results

Engraftment and regimen-related toxicity

Eighty-two of 90 (91 %) patients engrafted with 1,000 leucocytes per microlitre at day +16 (median range 0–108) and 72/90 (80 %) with 20 thrombocytes per microlitre at 15.5 days (median range 0–103) after allogeneic transplantation. Regimen-related toxicity according to the Bearman scale was mild to moderate (Bearman et al. 1988). Mucosal and hepatic toxicity up to grade 2 followed by grade 1 renal toxicity was the leading events. Grade 3 toxicity was rare, and only one patient experienced lethal grade 4 toxicity of the liver (Table 4). Infectious complications were scored according to the NIH/NCI criteria. Twenty-four (26 %) patients had no infectious complications, one (1 %) patient each experienced grade 1, three (3 %) patients severe 3° and four (4 %) patients life-threatening 4° infections. 13 (14 %) patients died from infections after allogeneic SCT (grade 5).

Table 4.

Regimen-related toxicity according to the Bearman scale

| Grade | Cardiac | Bladder | Kidney | Lung | Liver | Mucosa | GIT | CNS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 79 | 87 | 58 | 77 | 36 | 48 | 78 | 86 |

| I | 3 | 0 | 24 | 5 | 35 | 18 | 9 | 2 |

| II | 4 | 3 | 6 | 4 | 14 | 22 | 1 | 2 |

| III | 4 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| IV | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| N | 90 | 90 | 89a | 90 | 89a | 90 | 90 | 90 |

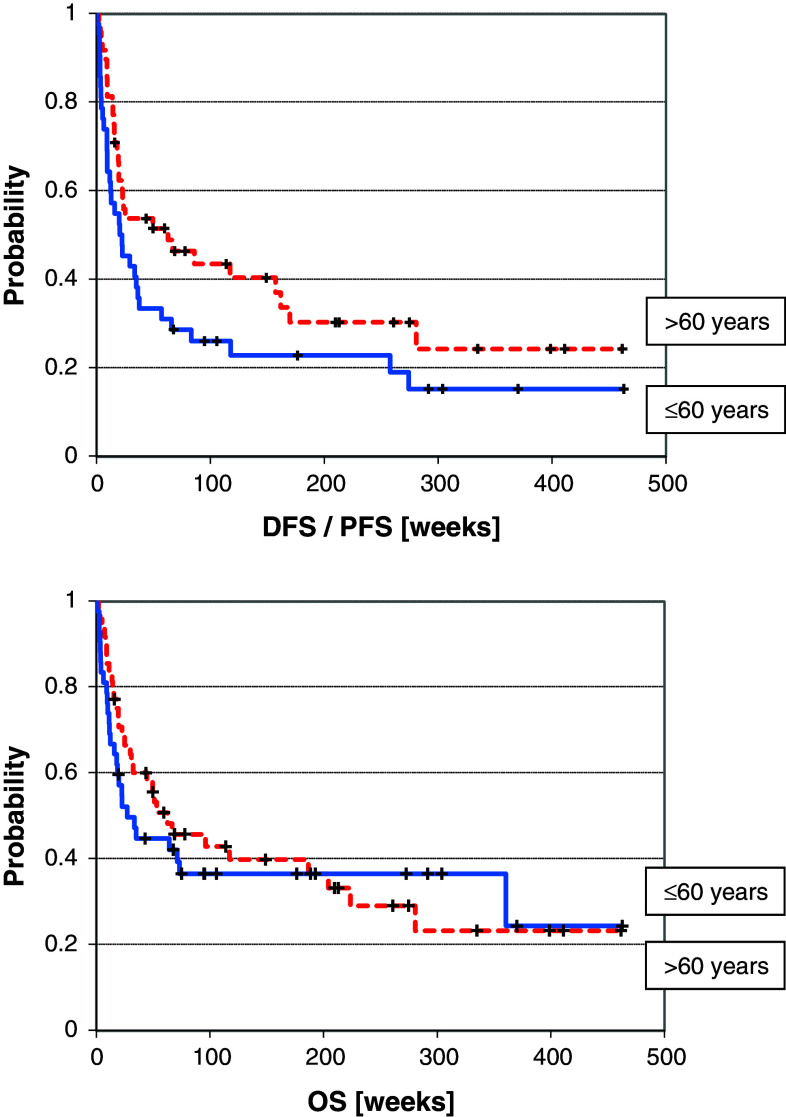

The age-related survival is shown in Fig. 1

aData not available in one case each

Donor lymphocyte infusions and acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease

Sixteen (18 %) of the patients received donor lymphocyte infusions after alloSCT, either for treatment of relapse (n = 10, 11 %) or for prevention of graft failure or treatment of minimal residual disease (n = 6, 7 %). Two infusions (median range 1–7) were given containing a cumulative dose of 7.5 (median range 0.57–71) × 106 CD3+ cells per kg bodyweight.

Twenty-five patients developed acute GvHD at 41 (median range 7–118) days after alloSCT (Table 5). The majority of cases was mild to moderate (n = 16, 18 %), but 9 (10 %) patients suffered from severe disease. Severe aGvHD was due to hepatic and enteric manifestation. Acute graft-versus-host disease had an incidence of 31 % (5/16) after donor lymphocyte infusion. Two (13 %) patients suffered from stage II and stage IV each and one (6 %) patient from stage I disease (Table 5). Chronic GvHD occurred in 21 % (n = 19) after alloSCT. Eleven (12 %) patients had limited disease and eight (8 %) patients extensive disease.

Table 5.

Acute and chronic GvHD after stem cell transplantation and donor lymphocyte infusions

| Overall grading | I | II | III | IV | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute GvHD after alloSCT | |||||

| N (%) | 7 (8 %) | 9 (10 %) | 8 (9 %) | 1 (1 %) | 25 (28 %) |

| Acute GvHD after DLI (n = 16) | |||||

| N (%) | 1 (6 %) | 2 (13 %) | 0 | 2 (13 %) | 5 (31 %) |

| Chronic GvHD | |||||

|

Limited disease n = 11 (12 %) |

Extensive disease N = 8 (9 %) |

Total n = 19 (21 %) |

|||

Results after allogeneic SCT ± DLI

Seventy-nine (88 %) patients had a complete remission after alloSCT. Five (6 %) patients each had a partial remission or a progressive disease, and one (1 %) patient relapsed immediately after alloSCT. In total, 27 (30 %) patients relapsed 161 (median range 20–1,920) days after alloSCT, and 7 (8 %) patients experienced progress of underlying disease at day 28 (median range 14–602) after alloSCT. Donor lymphocyte infusions could re-induce a remission in seven cases.

Mortality

The overall mortality was 68 % (58/85). Twenty-six (31 %) patients died from underlying disease due to relapse or progress, and 32 (38 %) patients died from NRM. Nineteen patients died from infectious complications, three from GvHD and ten due to other reasons such as pulmonary bleeding (n = 2), liver failure (n = 2), myocardial infarction, suicide, secondary malignancy, BOOP syndrome, leukoencephalopathy and pancreatitis.

Survival analysis

The median disease or progression-free survival of the entire group was 170 days with a range from 4 to 3,241 days, and the median overall survival was 302.5 days (range 4–3,241 days). A variety of parameters were analysed using the log-rank test for a possible association with DFS/EFS and OS (Table 6).

Table 6.

Factors influencing DFS/PFS and OS

| Parameter | Patients | DFS/PFS (p) | OS (p) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient: male versus female | 54 versus 36 | n.s. | n.s. |

| Patient’s age: ≤60 versus >60 | 42 versus 48 | 0.08, n.s. | n.s. |

| Donor: mrd versus mud | 15 versus 75 | n.s. | n.s. |

| SCT: Don.female to Rec.male versus other | 14 versus 76 | n.s. | n.s. |

| CMV: Don.neg to Rec.pos versus other | 14 versus 76 | n.s. | n.s. |

|

HLA match (mud only) 10/10 versus 9/10 versus <9/10 |

49 versus 18 versus 8 | n.s. | n.s. |

| Conditioning MAC versus NMC versus RIC | 42 versus 38 versus 10 | n.s. | n.s. |

|

HCT-CIconventional 0 versus 1–2 versus ≥3 |

18 versus 26 versus 45 | 0.08, n.s. | n.s. |

|

HCT-CImodified 0–2 versus 3–5 versus 6–9 |

44 versus 30 versus 15 | 0.013 | 0.02 |

| Acute GvHD/no aGvHD | 25 versus 65 | n.s. | n.s. |

| Chronic GvHD/no cGvHD | 19 versus 71 | 0.000026 | 0.000024 |

| cGvHDltd versus cGvHDext versus no cGvHD | 11 versus 8 versus 71 | 0.00012 | 0.00014 |

Exact values are only given below 0.05 and for a trend (<0.10)

The following parameters could be associated with a superior survival: patients suffering from a chronic GvHD after alloSCT, either in the stage of limited or extensive disease, had improved DFS/EFS (p = 0.00012) and OS (p = 0.0014) compared to patients without chronic GvHD (Table 6; Fig. 2). The classical HCT-CI could not identify different risk groups with a significance level of 0.05 or better in our investigation (Table 6; Fig. 3). In contrast, the application of the modified HCT-CI with the score groups 0–2, 3–5 and 6–9 identified significant differences in DFS/EFS (p = 0.013) as well as in OS (p = 0.014) between the three groups (Fig. 4).

Fig. 2.

DFS/PFS (p = 0.00012) and OS (p = 0.00014) related to chronic GvHD

Fig. 3.

DFS/PFS (p = 0.08) and OS (p = 0.1) related to the HCT-CI

Fig. 4.

DFS/PFS (p = 0.013) and OS (p = 0.02) related to the modified HCT-CI

A patient’s age of 60 years and higher did affect neither the DFS/EFS nor the OS negatively after alloSCT (Table 6; Fig. 1). In addition, the parameters related versus unrelated donor, female-to-male SCT versus other, CMV serology, HLA match, intensity of conditioning regimen and manifestation of an acute GvHD after stem cell transplantation were without significant influence on course and survival (DFS/EFS and OS) after transplantation (Table 1, curves not shown).

Fig. 1.

Age-related DFS/PFS (0.08) and OS (p = 0.58)

Discussion

Patients aged above 60 years with haematological malignancies were in the past mainly subjected to palliative therapy strategies. This is mainly true for the acute myeloid leukaemia and for myelodysplastic syndromes. For many years, it has been assumed that elderly patients were mainly ineligible for more intensive approaches (Ferrara et al. 2001). However, already in the late 1970s, the Seattle group began to treat selected patients above 60 years of age successfully with allogeneic marrow transplantation after MAC and reported a long-term survival of 36 % (Wallen et al. 2005). The first data that fit elderly patients who may have considerable benefit from intensive therapy were delivered by registry analyses (Juliusson et al. 2009). Allogeneic haemopoietic stem cell transplantation became broader available for older and pre-treated patients after introduction of dose-reduced conditioning protocols (Baron and Storb 2004; Corradini et al. 2002; Shapira et al. 2004). To allow an estimation of the risk of these patients for death after transplantation, Sorror et al. developed the HCT-CI (Sorror et al. 2007b; Sorror 2010). Patients were stratified into three groups without comorbidities (score 0), with 1–2 points and in high-risk patients with a score of three and higher. However, the survival curves suggest that even high-risk patients could have considerable benefit from an alloSCT compared to palliative treatment (Deschler et al. 2006).

To address this important question, we have analysed all haemopoietic stem cell transplantations performed in patients at least 55 years of age at Greifswald University Medical Centre from the begin of the local transplant programme in 1999–2011. The data from ninety stem cell transplantations performed in 85 patients were available for analysis. The data confirm clearly that elderly patients do not perform necessarily worse compared to younger patients (Table 6; Fig. 1). The application of the HCT-CI to the entire cohort scored 51 % into the high-risk group. This is in accordance with the data from Houston but not from Seattle (Table 2) (Sorror et al. 2007b). These variations can be easily explained by individual selection criteria. Sorror et al. showed convincingly that patients scoring in the low- and intermediate-risk groups have an excellent course after alloSCT. This observation was confirmed in the present analysis (Table 6; Fig. 3). Since more than 50 % of our patients scored into the high-risk group, it was the goal to clarify the question, which patients from the high-risk group could have substantial benefit from an alloSCT. This question is from urgent interest due to the fact that especially elderly patients with high-risk malignancies have an extremely poor prognosis under conventional therapy (Stone et al. 2004; Burnett et al. 2013; Gattermann et al. 2013). The alternative risk stratification showed first that the risk profile of elderly patients was not higher than that of younger patients (Table 2). This observation might be due to a stronger patient selection with increasing age. Secondly was shown that even patients scored to the high-risk group of the classic HCT-CI can be successfully allografted. The alternative HCT-CI stratification showed a comparable overall survival for patients with the scores 0–2 and 3–5 (Fig. 4). Additionally, it allows a clear discrimination of patients at high and at very high risk prior to alloSCT.

Manifestation of chronic GvHD improved the outcome after alloSCT significantly. This result is in accordance with other publications describing the graft-versus-leukaemia/lymphoma (GvL) effects after alloSCT in conjunction with cGvHD (Crawley et al. 2005). Particularly after conditioning with non-myeloablative protocols, the GvL is mandatory for eradication of malignancy (Crawley et al. 2005; Kolb et al. 2004). The excellent transplant results in patients with chronic GvHD underline the feasibility of alloSCT in patients with considerable comorbidities and in elderly patients. Furthermore, they should encourage haematologists to consider an early reduction and withdrawal of immunosuppression.

In conclusion, the published data encourage treatment of elderly patients and of patients scoring into the high-risk group of the classic HCT-CI with high-risk malignancies by alloSCT. Furthermore, the investigators propose to investigate an additional stratification of the high-risk group of the classic HCT-CI in larger trials. Finally, the presented data show that an early reduction of immunosuppression permitting GvL effects with or without cGvHD is a feasible approach, even in elderly patients or in patients with comorbidities.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the nurses from the BMT unit for the excellent patient care.

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- Akpek G, Lee SJ, Flowers ME, Pavletic SZ, Arora M, Lee S, Piantadosi S, Guthrie KA, Lynch JC, Takatu A, Horowitz MM, Antin JH, Weisdorf DJ, Martin PJ, Vogelsang GB (2003) Performance of a new clinical grading system for chronic graft-versus-host disease: a multicenter study. Blood 102:802–809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appelbaum FR (2001) Who should be transplanted for AML? Leukemia 15:680–682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron F, Storb R (2004) Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation as treatment for hematological malignancies: a review. Springer Semin Immunopathol 26:71–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bearman SI, Appelbaum FR, Buckner CD, Petersen FB, Fisher LD, Clift RA, Thomas ED (1988) Regimen-related toxicity in patients undergoing bone marrow transplantation. J Clin Oncol 6:1562–1568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolwell B, Sobecks R, Pohlman B, Andresen S, Rybicki L, Kuczkowski E, Kalaycio M (2004) A prospective randomized trial comparing cyclosporine and short course methotrexate with cyclosporine and mycophenolate mofetil for GVHD prophylaxis in myeloablative allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 34:621–625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnett AK, Russell NH, Hunter AE, Milligan D, Knapper S, Wheatley K, Yin J, McMullin MF, Ali S, Bowen D, Hills RK (2013) Clofarabine doubles the response rate in older patients with acute myeloid leukemia but does not improve survival. Blood 122:1384–1394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casper J, Knauf W, Kiefer T, Wolff D, Steiner B, Hammer U, Wegener R, Kleine HD, Wilhelm S, Knopp A, Hartung G, Dölken G, Freund M (2004) Treosulfan and fludarabine: a new toxicity-reduced conditioning regimen for allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood 103:725–731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corradini P, Tarella C, Olivieri A, Gianni AM, Voena C, Zallio F, Ladetto M, Falda M, Lucesole M, Dodero A, Ciceri F, Benedetti F, Rambaldi A, Sajeva MR, Tresoldi M, Pileri A, Bordignon C, Bregni M (2002) Reduced-intensity conditioning followed by allografting of hematopoietic cells can produce clinical and molecular remissions in patients with poor-risk hematologic malignancies. Blood 99:75–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawley C, Lalancette M, Szydlo R, Gilleece M, Peggs K, Mackinnon S, Juliusson G, Ahlberg L, Nagler A, Shimoni A, Sureda A, Boiron JM, Einsele H, Chopra R, Carella A, Cavenagh J, Gratwohl A, Garban F, Zander A, Bjorkstrand B, Niederwieser D, Gahrton G, Apperley JF (2005) Outcomes for reduced-intensity allogeneic transplantation for multiple myeloma: an analysis of prognostic factors from the Chronic Leukaemia Working Party of the EBMT. Blood 105:4532–4539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutler C, Giri S, Jeyapalan S, Paniagua D, Viswanathan A, Antin JH (2001) Acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic peripheral-blood stem-cell and bone marrow transplantation: a meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol 19:3685–3691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deschler B, de WT, Mertelsmann R, Lübbert M (2006) Treatment decision-making for older patients with high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome or acute myeloid leukemia: problems and approaches. Haematologica 91:1513–1522 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara F, Morabito F, Latagliata R, Martino B, Annunziata M, Oliva E, Schiavone EM, Pollio F, Palmieri S, Gianfaldoni G, Leoni F (2001) Aggressive salvage treatment is not appropriate for the majority of elderly patients with acute myeloid leukemia relapsed from first complete remission. Haematologica 86:814–820 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gattermann N, Kündgen A, Kellermann L, Zeffel M, Paessens B, Germing U (2013) The impact of age on the diagnosis and therapy of myelodysplastic syndromes: results from a retrospective multicenter analysis in Germany. Eur J Haematol 91(6):473–482 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Glucksberg H, Storb R, Fefer A, Buckner CD, Neiman PE, Clift RA, Lerner KG, Thomas ED (1974) Clinical manifestations of graft-versus-host disease in human recipients of marrow from HL-A-matched sibling donors. Transplantation 18:295–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juliusson G, Antunovic P, Derolf A, Lehmann S, Möllgard L, Stockelberg D, Tidefelt U, Wahlin A, Höglund M (2009) Age and acute myeloid leukemia: real world data on decision to treat and outcomes from the Swedish Acute Leukemia Registry. Blood 113:4179–4187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolb HJ, Schmid C, Barrett AJ, Schendel DJ (2004) Graft-versus-leukemia reactions in allogeneic chimeras. Blood 103:767–776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krüger WH, Bohlius J, Cornely OA, Einsele H, Hebart H, Massenkeil G, Schüttrumpf S, Silling G, Ullmann AJ, Waldschmidt DT, Wolf HH (2005) Antimicrobial prophylaxis in allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Working Party (AGIHO) of the German Society of Haematology and Oncology. Ann Oncol 16:1381–1390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SJ, Klein JP, Barrett AJ, Ringden O, Antin JH, Cahn JY, Carabasi MH, Gale RP, Giralt S, Hale GA, Ilhan O, McCarthy PL, Socie G, Verdonck LF, Weisdorf DJ, Horowitz MM (2002) Severity of chronic graft-versus-host disease: association with treatment-related mortality and relapse. Blood 100:406–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niederwieser D, Maris M, Shizuru JA, Petersdorf E, Hegenbart U, Sandmaier BM, Maloney DG, Storer B, Lange T, Chauncey T, Deininger M, Pönisch W, Anasetti C, Woolfrey A, Little MT, Blume KG, McSweeney PA, Storb RF (2003) Low-dose total body irradiation (TBI) and fludarabine followed by hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) from HLA-matched or mismatched unrelated donors and postgrafting immunosuppression with cyclosporine and mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) can induce durable complete chimerism and sustained remissions in patients with hematological diseases. Blood 101:1620–1629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niederwieser D, Lange T, Cross M, Basara N, Al-Ali H (2006) Reduced intensity conditioning (RIC) haematopoietic cell transplants in elderly patients with AML. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol 19:825–838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneidawind D, Federmann B, Faul C, Vogel W, Kanz L, Bethge WA (2013) Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation with reduced-intensity conditioning following FLAMSA for primary refractory or relapsed acute myeloid leukemia. Ann Hematol 92:1389–1395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapira MY, Resnick IB, Bitan M, Ackerstein A, Samuel S, Elad S, Miron S, Zilberman I, Slavin S, Or R (2004) Low transplant-related mortality with allogeneic stem cell transplantation in elderly patients. Bone Marrow Transplant 34:155–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapira MY, Tsirigotis P, Resnick IB, Or R, Abdul-Hai A, Slavin S (2007) Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in the elderly. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 64:49–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorror ML (2010) Comorbidities and hematopoietic cell transplantation outcomes. Hematol Am Soc Hematol Educ Progr 2010:237–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorror ML, Giralt S, Sandmaier BM, de LM, Shahjahan M, Maloney DG, Deeg HJ, Appelbaum FR, Storer B, Storb R (2007a) Hematopoietic cell transplantation specific comorbidity index as an outcome predictor for patients with acute myeloid leukemia in first remission: combined FHCRC and MDACC experiences. Blood 110:4606–4613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorror ML, Sandmaier BM, Storer BE, Maris MB, Baron F, Maloney DG, Scott BL, Deeg HJ, Appelbaum FR, Storb R (2007b) Comorbidity and disease status based risk stratification of outcomes among patients with acute myeloid leukemia or myelodysplasia receiving allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol 25:4246–4254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone RM, O’Donnell MR, Sekeres MA (2004) Acute myeloid leukemia. Hematol Am Soc Hematol Educ Progr 2004:98–117 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Vogelsang GB (1993) Acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease. Curr Opin Oncol 5:276–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallen H, Gooley TA, Deeg HJ, Pagel JM, Press OW, Appelbaum FR, Storb R, Gopal AK (2005) Ablative allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation in adults 60 years of age and older. J Clin Oncol 23:3439–3446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zander AR, Berger C, Kröger N, Stockschläder M, Krüger W, Horstmann M, Grimm J, Zeller W, Kabisch H, Erttmann R, Schönrock P, Kuse R, Braumann D, Illiger HJ, Fiedler W, de WM, Hossfeld KD, Weh HJ (1997) High dose chemotherapy with busulfan, cyclophosphamide, and etoposide as conditioning regimen for allogeneic bone marrow transplantation for patients with acute myeloid leukemia in first complete remission. Clin Cancer Res 3:2671–2675 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]