ABSTRACT

Background

Plasmid mediated antimicrobial resistance continues to be a source of global concern, especially given the limited pipeline of novel antibiotics. The horizontal transfer of the plasmid mediated colistin resistance gene (mcr‐1) between microorganisms confer resistance to previously susceptible bacterial strains and renders colistin and polymyxin B antimicrobials ineffective.

Objective

To mitigate plasmid mediated colistin resistance using bambermycin and streptomycin on mcr‐1 positive field strains of Escherichia coli. Furthermore, to assess if a commercial MCR‐1 polyclonal antibody would have any synergistic effect on colistin in killing mcr‐1 gene associated colistin‐resistant E. coli in vitro.

Methods

Colistin‐resistant E. coli strains recovered from clinical cases were subjected to checkerboard assays and conjugation assays using varying drug combinations viz colistin, bambermycin, streptomycin, MCR‐1 antibody and human complement serum, to mitigate drug resistance.

Results

Following conjugation assay, the plasmid bound resistance gene was successfully transferred to J53 E. coli strain with colistin minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) rising from ≤0.125 to >2 µg/mL conferring resistance to the former organism. The combination of bambermycin and colistin in a checkerboard assay proved to be synergistic in killing mcr‐1 associated colistin‐resistant strains. The combination of streptomycin, colistin and MCR‐1 polyclonal antibody showed additive lethal effect on mcr‐1 associated colistin‐resistant strains. Bambermycin did not interfere with the transfer of mcr‐1 bound plasmid from donors to recipient organism.

Conclusion

Further studies on bambermycin's mechanism of action are required, as both inhibiting and enhancing effects have been documented. Similarly, the addition of MCR‐1 polyclonal antibody in a checkerboard assay did not enhance colistin's lethal effect on mcr‐1 carrying E. coli strains, thus highlighting the need for further research.

Keywords: AMR, bambermycin, colistin, E. coli, mcr‐1

Bambermycin showed synergistic effect with colistin on mcr‐1 positive E. coli strains. Colistin and MCR‐1 antibody mixture showed additive lethal effect on mcr‐1 strains. Bambermycin had no effect on the transfer of mcr‐1 bound plasmids between organisms.

1. Introduction

Plasmid mediated antimicrobial resistance continues to be a source of global concern, especially given the limited pipeline of novel antibiotics. We are at a point where horizontal transfer of resistant determinants between bacterial organisms is now possible in the absence of selection pressure, with bacterium being able to take up mobile elements from the environment and/or share genetic information for drug resistance through plasmid conjugation (Barlow 2009; Devanga Ragupathi et al. 2019; Kloos 2021; Poole et al. 2006). In 2016, the mcr plasmid mediated colistin resistance gene (mcr‐1) was first discovered in China and subsequently in other parts of the world, including South Africa (Coetzee et al. 2016; Liu et al. 2016; Rhouma et al. 2016; Xavier et al. 2016; Yin et al. 2017). The gene mediates the addition of phosphoethanolamine on the lipid A portion of bacterial lipopolysaccharides (LPS) with resultant reduced colistin (polymyxin E) and polymyxin B's affinity, thereby conferring resistance.

In light of the emergence of mcr colistin resistance in South Africa, veterinary colistin use became restricted to life‐threatening infections only responsive to colistin through antibiogram evaluation. This strategy was put in place to urgently curtail the spread of resistance given that overuse has been attributed to the spread (Al‐Tawfiq et al. 2017; SAVC 2016; WHO 2019). More so, colistin, which used to be avoided as a human therapeutic option, has now been re‐incorporated and considered for critical human cases despite its safety drawbacks. It has become the last line of defence against carbapenem‐resistant Acinetobacter baumannii and Enterobacteriaceae infections (Nordmann and Poirel 2016; Poirel et al. 2016; Qureshi et al. 2015).As part of measures to reduce the veterinary use of antimicrobials in the past, several attempts to develop vaccines against various pathogens were made with some level of success (Bensink and Spradbrow 1999; La Ragione et al. 2013; Matsuda et al. 2011). Additionally, other strategies to mitigate AMR may involve exploring the benefits of synergistic interactions between drug compounds and/or immunoglobulins so as to improve drug efficacy and extend drug life spans (Aminov 2017). These benefits have already been demonstrated, as the combination of a monoclonal antibody with co‐trimoxazole, ticarcillin‐clavulanate or ciprofloxacin has been shown to enhance the bactericidal activity of the latter (Al‐Hamad et al. 2011).

Similarly, with drug‐drug combination, a colistin‐carbapenem combination was associated with a reduced 14‐day mortality rate in extensively drug‐resistant A. baumannii bacteremia in humans (Cheng et al. 2015). Importantly, the world could benefit from drug molecules with the critical ability of hindering the transfer of resistant determinants between microorganisms or with a direct effect on resistance proteins, as these serve as major mechanisms of resistance acquisition. One drug compound with such potential is bambermycin, a complex phosphoglycolipid antibacterial with no known related human analogue (Butaye et al. 2003). It is exclusively used in the livestock industry as a feed additive and currently has no therapeutic use. However, data have historically demonstrated that bambermycin inhibits the transfer of plasmids between bacterial organisms, that is, Escherichia coli and Enterococcus sp. (Kudo et al. 2019; Poole et al. 2006; Riedl et al. 2000). The compound is also ideal for testing, as it has no documented horizontally acquired resistance mechanisms despite its extensive use in food animals to improve nutritional performance and intestinal health for efficient weight gain (Barros et al. 2012; Butaye et al. 2003; Pfaller 2006). A second ideal drug would be one that target bacterial cellular processes different to those of colistin. The aminoglycosides fulfil this criterion, as they interfere with bacterial protein synthesis within the cell (Cavaco et al. 2016; Rebelo et al. 2018), as opposed to colistin and bambermycin, whose targets are limited to the bacterial cell wall (Butaye et al. 2003; De Witte et al. 2018; Dijkmans et al. 2015; Yu et al. 2015). The objective of this study was to explore the principle of multidrug therapy, relying on MCR‐1 polyclonal antibody in order to improve the efficacy of colistin on colistin‐resistant strains as an additional strategy to extend its life span as an effective antimicrobial. In this regard, we evaluated the synergistic effect of bambermycin, streptomycin and/or MCR‐1 specific antibody on colistin in killing colistin‐resistant microorganisms in vitro. It also assessed the effect of bambermycin on the transfer rate of mcr‐1‐gene‐carrying plasmids between E. coli organisms in vitro.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Antibacterial Susceptibility Testing Using Broth Microdilution Technique

2.1.1. Selection of the Resistant Strain

The study made use of available banked (presumptive colistin‐resistant) E. coli strains (n = 20), with seven originating from domestic chicken (Hassan et al. 2023) and 13 of bovine faecal source (Mupfunya et al. 2021). As a first step, an appropriate colistin‐resistant strain needed to be identified. Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of bambermycin, streptomycin and colistin were determined for isolates using broth microdilution technique in duplicate (see Supporting Information section for details). For quality control, an mcr‐1 positive colistin‐resistant E. coli strain (kindly donated by Prof Marleen Kock) and the E. coli ATCC 25922 were included for all analyses.

2.2. Checkerboard Assays

2.2.1. Colistin and Bambermycin

Microtiter plates were prepared with colistin sulphate, and bambermycin solution for antimicrobial susceptibility testing (see Supporting Information section for details). The concentration of colistin along the ordinate of the plate ranged from 127.5 to 0.125 µg/mL in folds of two, whereas that of bambermycin solution along the abscissa ranged from 128 to 1 µg/mL.

2.2.2. Colistin and MCR‐1 Antibody

The concentration of colistin along the ordinate of the plate ranged followed a two‐fold dilution (32–0.5 µg/mL), whereas that of the MCR‐1 antibody solution (Abbexa LLC, Houston, TX USA) along the abscissa ranged from 1000 to 1.95 ng per well.

2.2.3. Colistin, Streptomycin and MCR‐1 Antibody

The concentration of colistin sulphate/streptomycin combination along the ordinate of the plate followed a two‐fold dilution (8/256–0.125/4 µg/mL), whereas that of the MCR‐1 antibody solution along the abscissa ranged from 1000 to 1.95 ng per well.

2.2.4. Colistin, Streptomycin, MCR‐1 Antibody With Complement

The concentration of colistin sulphate and streptomycin combination along the ordinate of the plate followed a two‐fold dilution (8/256–0.125/4 µg/mL), respectively, whereas that of the MCR‐1 antibody solution along the abscissa ranged from 1000 to 1.95 ng per well. However, in this case the stock antibody solution was diluted using 1:50 human complement serum (Sigma‐Aldrich, Saint Louis, Missouri, USA).

Suspensions of bacterial isolates to be tested were prepared, inoculated and incubated to the letter (see Supporting Information section). Each checkerboard assay plate was assigned to a single bacterial isolate. Prior to determining the fractional inhibitory concentration (FIC) index, the plates were briefly incubated aerobically for 2 min at 37°C with shaking at 240 revolutions per minute (rpm) (Lorian 2005; Orhan et al. 2005; Yu et al. 2019). The FIC index was determined using the following arithmetic equation.

| (1) |

where A is the MIC of drug A in combination with drug B; B is the MIC of drug B in combination with drug A; MICA is the MIC of drug A; MICB is the MIC of drug B; FICA is the FIC of drug A; FICB is the FIC of drug B; FIC Index is the FIC index; FIC index of <0.5 is the presence of synergy between the two drug compounds; FIC index of 0.5–4 is the presence of additive effect between the two drug compounds; FIC index of >4 is the presence of antagonism between the two drug compounds.

2.3. Conjugation Assays

2.3.1. Determining the Frequency of mcr‐1 Gene Transfer Between Organisms

All mcr‐1 positive (donor) E. coli organisms and the J53 recipient E. coli isolate were grown separately overnight on 5% blood agar at 37°C for 24 h. Resulting cultures were inoculated into 3 mL Luria‐Bertani (LB) broth each and incubated aerobically for 3 h at 37°C with gentle shaking (120 rpm). Subsequently, one part of donor cells with four parts of recipient cells (Herrero et al. 1990; Ortiz de la Rosa et al. 2021) were transferred into a fresh Bijou bottle and incubated for 3 h at 37°C with gentle shaking (120 rpm). After 3 h of incubation, aliquots were serially diluted and then plated onto the appropriate selective media in duplicates and subsequently incubated for 24 h at 37°C to select for trans‐conjugant, donor and recipient cells. Enumeration of trans‐conjugants was undertaken.

2.3.2. mcr‐1 Gene Uptake Confirmation

Direct colony PCR was carried out on trans‐conjugants to confirm the uptake of mcr‐1gene harbouring plasmids. Single trans‐conjugant colonies were transferred into PCR tubes as DNA templates with mcr‐1 specific primers; F: 5′CGGTCAGTCCGTTTGTTC′3 and R: 5′CTTGGTCGGTCTGTAGGG′3; and Dream Taq Green PCR Master Mix (2X) for the reaction. Thermo‐cycling condition was maintained at 94°C 15 min + 25 × (94°C 30 s + 58°C 90 s + 72°C 60 s) + 72°C 10 min. Amplicons (309 bp) were subjected to agarose gel electrophoresis using 1.5% gel in 1 × TBE with ethidium bromide. The gels ran for 90 min at 90 V before visualizing the bands (Cavaco et al. 2016; Rebelo et al. 2018).

2.3.3. Determining the Effect of Bambermycin on Frequency of mcr‐1 Gene Transfer

2.3.3.1. Observable Effects Associated With Bambermycin Inclusion

Four donor strains and the recipient organisms were grown separately overnight on 5% blood agar at 37°C for 24 h. Resulting cultures were inoculated into LB broth each and incubated aerobically for 3 h at 37°C with gentle shaking (120 rpm). Subsequently, one part of donor cells to four parts of recipient cells were mixed into fresh Bijou bottles in duplicates. Bambermycin stock solution (128 µg/mL) was introduced into the first broth culture mix to give a concentration of 32 µg/mL of Bambermycin. To the second broth culture mix, equivalent volumes of diluent (MeOH) was added. Both broth culture mixtures were incubated for 3 h at 37°C with gentle shaking (120 rpm). Aliquots from both mixtures were individually taken, vortexed and placed on ice before plating unto the appropriate separate selective media in duplicates for enumeration of donor, recipient and trans‐conjugant cells (Will and Frost 2006). Direct colony PCR was carried out on trans‐conjugants to confirm the uptake of mcr‐1 plasmids, as previously described above. The numbers of trans‐conjugants to donor cells generated were then equalized for comparison between the two groups.

2.3.3.2. Effect of Varying Concentrations of Bambermycin on Rate of Plasmid Transfer

A single donor E. coli strain and the recipient organism (J53) were grown separately overnight on 5% blood agar at 37°C for 24 h. The resulting culture of the donor organism was inoculated into LB broths containing varying concentrations of bambermycin (0–64 µg/mL) and incubated for 3 h at 37°C with gentle shaking (120 rpm). Recipient culture was inoculated into plain LB broth and incubated similarly. Subsequently, to one part of donor cell culture, four parts of recipient cell cultures were added while maintaining the varying concentrations of bambermycin as indicated. Co‐cultures were incubated for 24 h at 37°C with gentle shaking (120 rpm). After 24 h of incubation, cultures were vortexed and placed on ice before plating on appropriate selective media. All plates were incubated aerobically for 24 h at 37°C before enumeration. Direct colony PCR was carried out on trans‐conjugants to confirm the uptake of mcr‐1 plasmids as previously described above. Trans‐conjugant numbers to donor cells were then compared after normalization (Händel et al. 2015; Poole et al. 2006; Will and Frost 2006).

2.3.3.3. Effect of Bambermycin on Transfer Frequency Over Time

Overnight grown cultures of a donor strain and the recipient organism were inoculated into LB broth each and incubated aerobically for 3 h at 37°C with gentle shaking (120 rpm). Subsequently, one part of donor cell cultures to four parts of recipient cell cultures were mixed into fresh Bijou bottles in duplicates. To the first part, Bambermycin stock solution (1300 µg/mL) was added to give a concentration of 260 µg/mL, whereas the second part had just the diluent (MeOH) added in equal volume of the former. Both broth culture mixtures were incubated for 24 h at 37°C with gentle shaking (120 rpm). Aliquots of 200 µL from both mixtures were individually taken at time intervals from 0 h through 1.5, 3, 7, 12 to 21 h. These aliquots were then vortexed and placed on ice before plating on appropriate selective media in duplicate. All plates were incubated anaerobically for 24 h at 37°C before enumeration. Direct colony PCR was carried out on trans‐conjugants to confirm the uptake of mcr‐1 plasmids as previously described above. Trans‐conjugant numbers to donor cells were then compared after normalization (Händel et al. 2015; Poole et al. 2006; Will and Frost 2006).

The mean numbers of trans‐conjugants to donor cells per time points were compared between bambermycin and bambermycin‐free assays with the aid of Microsoft Excel 2010 (Microsoft Office Corporation, USA) using the student's t test with p value set to 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Selection of the Correct Strain

Of all the 20 E. coli strains tested, only five were found to be resistant to colistin with MIC's of 4 µg/mL (Table 1) and were considered further. These later strains were all of avian origin.

TABLE 1.

Demonstrating the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of colistin, bambermycin and streptomycin in colistin resistant avian Escherichia coli isolates.

| Isolate | Minimum inhibitory concentration (µg/mL) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Colistin | Bambermycin | Streptomycin | |

| 1 | 4 | >128 | 8 |

| 2 | 4 | >128 | 64 |

| 3 | 4 | >128 | 16 |

| 4 | 4 | >128 | 128 |

| 5 | 4 | >128 | >128 |

Note: Minimum inhibitory concentration assays were undertaken in duplicates using manual broth micro dilution technique.

The MIC of bambermycin on the isolates were all above the highest concentration tested (Table 1). Methanol demonstrated no masking effect on the MIC's as all isolate grew in the presence of blank diluent. The MIC of streptomycin on the isolates are presented in the table.

3.2. Checkerboard Assays

3.2.1. Bambermycin and Colistin

Following the combination of colistin and bambermycin during this assay, no antagonism was observed between the two drug compounds. The drug compounds demonstrated additive and synergistic effects on the isolates, as indicated by their FIC index (Table 2). The MIC of the drug compounds decreased significantly in the presence of the other.

TABLE 2.

Showing result of colistin/bambermycin checkerboard assays undertaken in avian Escherichia coli isolates.

| Isolate | In combination (µg/mL) MIC | As single agents (µg/mL) MIC | FIC Index | Interpretation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colistin | Bambermycin | Colistin | Bambermycin | |||

| 1 | 0.5 | 128 | 4 | >256 | 0.375 | Synergy |

| 2 | 0.5 | 128 | 4 | >256 | 0.375 | Synergy |

| 3 | 0.5 | 128 | 2 | >256 | 0.5 | Additive |

| 4 | 0.75 | 64 | 8 | >256 | 0.21875 | Synergy |

| 5 | 0.5 | 128 | 2 | >256 | 0.5 | Additive |

| mcr‐1 + positive control | 0.375 | 64 | 4 | >256 | 0.21875 | Synergy |

| J53 | No growth at all | |||||

Note: Assays were undertaken in duplicates.

Abbreviations: FIC Index, fractional inhibitory concentration index; MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration.

3.2.2. Colistin, Streptomycin, mcr‐1 Antibody With Complement

No synergy or antagonism was noted following colistin/MCR‐1 antibody; colistin/streptomycin/MCR‐1 antibody; and colistin/streptomycin/MCR‐1 antibody/complement checkerboard assays. In all cases, only additive effect was observed (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Showing result of colistin/streptomycin/MCR‐1 antibody checkerboard assays undertaken in avian Escherichia coli isolates.

| Isolate | In combination (µg/Ml) MIC | As single agents (µg/Ml) MIC | FIC Index | Interpretation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Col | Strept | Ab | Col | Strept | Ab | |||

| 3 | 0.5 | 16 | ≤1.95 | 4 | 16 | ≤1.95 | 2 | Additive |

| 3 | 0.5 | 16 | ≤1.95 | 4 | 16 | ≤1.95 | 2 | Additive |

| 1 | 8 | ≤1.95 | 8 | ≤1.95 | 2 | Additive | ||

| 2 | 2 | 64 | ≤1.95 | 4 | 64 | ≤1.95 | 2 | Additive |

Note: Highlighted cell‐assay undertaken in presence of human serum complement in duplicate.

Abbreviations: Ab, mcr‐1 antibody; Col, colistin; MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration; FIC Index, fractional inhibitory concentration index; Strept, streptomycin.

3.3. Conjugation Assays

3.3.1. Frequency of mcr‐1 Gene Transfer Between Organisms

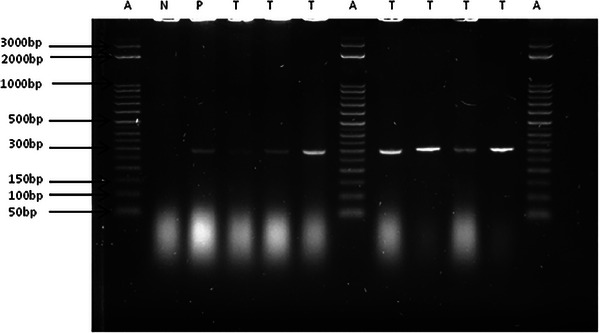

From the table below, the conjugation assay resulted in a sufficient number of trans‐conjugants (Table 4). Polymerase chain reaction products from the trans‐conjugants demonstrated presence of the mcr‐1 gene following gel electrophoresis (Figure 1). More important is the change in colistin MIC for J53 E. coli from a low of ≤0.125 µg/mL to a high of >2 µg/mL.

TABLE 4.

Showing colony counts of donor and trans‐conjugant Escherichia coli cells following a 3 h pre‐incubation conjugation assays.

| Isolates | Donor cells colony count (107 CFU/mL) | Trans‐conjugant cells (CFU/mL) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 268 | 552 ± 60 |

| 2 | 144 | 548 ± 32 |

| 3 | 197 | 1376 ± 56 |

| 4 | 93 | 4 ± 0 |

| mcr‐1 + positive control | 157 | 12 ± 4 |

FIGURE 1.

Gel image of mcr‐1 gene (309 bp) positive trans‐conjugants following direct colony PCR and electrophoresis. A = 50 bp DNA step ladder; B = 100 bp DNA ladder; N = negative control; P = positive control; T = trans‐conjugant.

3.3.2. In Vitro Effect of Bambermycin on the Transfer of mcr‐1 Gene

Following a 3 h pre‐incubation conjugation assay in the presence and absence of bambermycin, there was no obvious suppressing effect on the rate of plasmid transfer in the strains tested. Except for one particular isolate, in which case the rate of mcr‐1 gene transfer was clearly suppressed in the presence of bambermycin, as indicated by the lesser number of trans‐conjugant to donor cells after normalization (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Showing colony counts of trans‐conjugant Escherichia coli cells in the presence and absence of bambermycin (32 µg/mL) following a 3 h pre‐incubation conjugation assay.

| Donor strains | Donor (106 CFU/mL) | Average number of trans‐conjugantsa (CFU/mL) | p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bambermycin | Drug free | Normalised | Bambermycin | Drug free | ||

| 1 | 185 | 85 | 21 | 2.4 × 103 ± 160 | 5.1 × 103 ± 140 | 0.004823 |

| 2 | 18 | 197 | 21 | 2.8 × 102 ± 160 | 1.5 × 102 ± 110 | 0.23375 |

| 3 | 42 | 195 | 21 | 9.4 × 102 ± 220 | 1.0 × 102 ± 20 | 0.148806 |

| 4 | 70 | 72 | 21 | 7.0 × 101 ± 10 | 3.0 × 101 ± 10 | 0.295167 |

aNormalize.

Similarly, in comparing the various numbers of trans‐conjugant to donor cells per millilitre in relation to the varying concentrations of bambermycin used, there was no obvious correlation or trend in numbers generated (Table 6 and Figure 2).

TABLE 6.

Showing colony counts of trans‐conjugant Escherichia coli cells in the presence of bambermycin (64–2 µg/mL) following a 3 h pre‐incubation conjugation assay.

| Sl. No. | Bambermycin (µg/mL) | Bacterial cell count (CFU/mL) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Donor | Trans‐conjugants | ||

| 1 | 64 | 2.4 × 109 | 9.8 × 103 |

| 2 | 32 | 2.4 × 109 | 12.2 × 103 |

| 3 | 16 | 2.4 × 109 | 12.5 × 103 |

| 4 | 8 | 2.4 × 109 | 9.8 × 103 |

| 5 | 4 | 2.4 × 109 | 14.0 × 103 |

| 6 | 2 | 2.4 × 109 | 8.1 × 103 |

| 7 | 0 | 2.4 × 109 | 10.0 × 103 |

Abbreviation: SN, serial number.

FIGURE 2.

Gel image of mcr‐1 gene (309 bp) positive trans‐conjugants following direct colony PCR and electrophoresis. A = DNA step ladder; N = negative control; P = positive control; T = trans‐conjugant.

When the frequency of conjugation over a 21 h period was monitored, the presence of bambermycin in culture clearly suppressed the rate of plasmid transfer between donor and recipient cells, as indicated by the number of trans‐conjugants formed per time point. Cultures prepared in the presence of bambermycin produced less trans‐conjugants to donor ratio when compared to cultures prepared in the absence of bambermycin (Table 7). This effect of bambermycin became clearer after normalization (Table 7). Polymerase chain reaction and electrophoresis confirmed the uptake of the mcr‐1 plasmid by the J53 E. coli recipient.

TABLE 7.

Showing colony count of donor and trans‐conjugant Escherichia coli cells in the presence and absence of bambermycin (260 µg/mL) following a 3 h pre‐incubation, over a 21 h period.

| Time (h) | Donor (106 CFU/mL) | Trans‐conjugants (CFU/mL) | Trans‐conjugants a (CFU/mL) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug free | Bambermycin | Drug free | Bambermycin | Drug free | Bambermycin | |

| 0 | 130 | 632 | 260 ± 20 | 260 ± 20 | 80 | 16 |

| 1.5 | 220 | 1646 | 120 ± 0 | 100 ± 0 | 22 | 2 |

| 3 | 492 | 826 | 0 ± 0 | 80 ± 20 | 0 | 4 |

| 7 | 96 | 614 | 220 ± 20 | 20 ± 0 | 92 | 1 |

| 12 | 158 | 224 | 100 ± 20 | 0 ± 0 | 25 | 0 |

| 21 | 50 | 40 | 20 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | 16 | 0 |

Normalize.

4. Discussion

The wide difference in MIC of colistin on the same isolates tested on different occasions was totally unexpected. Nonetheless, different subsets of a bacterial population with differing susceptibility phenotype towards colistin is not uncommon among the Enterobacteriaceae (Band and Weiss 2019; Chew et al. 2017; Jayol et al. 2015; Napier et al. 2014). The plausibility of resistant colonies being tested in the first occasion and the susceptible subpopulation tested in subsequent occasions may not be out of place, especially as subcultures of the strains were obtained from the former. Similarly, the ability of colistin drug residues to bind to commonly used microtiter plates has been shown to render media relatively drug‐free, allowing bacterial growth (Landman et al. 2013); thus, misclassifying organisms as resistant and affecting the accuracy of results obtained. This aligns with the opinion of some researchers who have regarded polymyxins susceptibility testing unreliable (Landman et al. 2013). In addition, the loss of a resistance determinant by a rather resistant organism could also be associated with reversion to susceptibility and thus could be a logical explanation for our observations in the present study.

One of the objectives of the present study was to determine the specific colistin MIC's of isolate carrying the mcr‐1 gene. Our findings, just like other studies, indicate that the presence of the mcr‐1 gene is associated with low‐level colistin resistance near the break point, that is, MIC of 4–8 µg/mL (Chew et al. 2017; Liu et al. 2016; Luo et al. 2017). Although in some rare occasions, organisms with MIC's below the breakpoint (<2 µg/mL) have been shown to possess the gene, which brings into question the clinical relevance of the gene (Fernandes et al. 2016; Hassan et al. 2021; Lentz et al. 2016). More important, attention should equally be given to colistin resistance due to chromosomal mutations, as they are usually associated with higher level of resistance (Luo et al. 2017). With WGS becoming more readily accessible, the identification of these resistance mechanism would become much easier.

The MIC's of bambermycin on isolates were beyond the highest concentration tested (256 µg/mL). This was not surprising, as previous reports have demonstrated E. coli to be bambermycin resistant (Pfaller 2006). Moreover, the drug targets bacterial cell wall peptidoglycan synthesis, which is limited in Gram‐negative organisms. The cell wall of Gram‐positive bacteria is chiefly made up of peptidoglycan, making them more susceptible to the drug.

One of the most significant observations noted in the present study is the synergy between colistin and bambermycin on some of the isolates tested. Given that the MIC's of bambermycin in combination with colistin were still on the high side, one may argue that the synergy and/or additive effect observed would not make any therapeutic sense. However, it is important to note that the MIC of the drug decreased significantly in the presence of colistin (Table 2). Bambermycin is known to have little or no effect on Gram‐negative bacteria because of its inability to penetrate their outer membranes, which prevents the drug from reaching its target. Conversely, in the presence of colistin, the drug appears to gain easy access to its target. Colistin interferes with the outer membrane permeability of Gram‐negative bacteria by attaching to the Lipid A portion of their LPS (Rhouma et al. 2016). The resulting compromised bacteria outer membrane allows passage of bambermycin, making it available to effectively inhibit the synthesis of the thin layer of peptidoglycan. The combination of both drugs effects ultimately leads to bacterial cell death. This is not different from the well documented synergy between the penicillins and aminoglycosides (Fantin and Carbon 1992). Although the latter's lethal effect is exerted by interfering with bacterial protein synthesis, its intracellular uptake is facilitated through impaired bacterial cell wall, initiated by the beta‐lactam combination (Fantin and Carbon 1992).

Clinicians have long taken advantage of this relationship, as numerous studies have shown that the observed in vivo synergism between the two drug class combinations is a direct reflection of their inherent in vitro synergistic property (Norden 1978; Sande and Courtney 1976; Sande and Johnson 1975). Similarly, this phenomenon in the present study suggests that the use of colistin/bambermycin combinations in poultry medicine should effectively kill E. coli strains associated with colibacillosis, including those resistant to colistin. More important is that it could also prevent the shedding of the former into the environment, especially as both drug compounds remain poorly absorbed within the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) and excreted unchanged. Furthermore, taking lessons from the common tuberculosis/human immunodeficiency virus (TB/HIV) multidrug therapy, which are often associated with drug toxicity and/or therapy failure arising from drug–drug interaction or drug‐disease interaction (Pepper et al. 2007; Tornheim and Dooley 2018), the present drug combination in the context of this study are not likely to present with such challenges, as both bambermycin and colistin are poorly absorbed orally and excreted unchanged in faeces. However, the risk of drug resistance emergence exist, especially as this use will make both parent drugs readily available in the environment, thus perpetually exerting selective pressure on microbes. Importantly, a colistin‐bambermycin‐mcr‐1 antibody assay could have provided additional valuable insights; however, this was not undertaken and may represent a limitation of the study.

The combination of colistin sulphate and streptomycin in the presence of polyclonal MCR‐1 antibody with human complement serum showed no synergistic effect in killing mcr‐1 gene associated colistin‐resistant E. coli strains. This was totally surprising, as one would expect to see a ‘lock and key’ interaction between the MCR‐1 protein (i.e., phosphoethanolamine transferase) and its antibody in conformity with the basic principle of antigen‐antibody reaction. However, we know that the structure of the former protein has not been fully elucidated as yet and perhaps could explain our results, as possibility exists that the antibody used may not have been a match for the full bacterial protein (Huang et al. 2018; Kai and Wang 2020). Moreover, the trans‐membrane localization of this protein may have prevented this antigen–antibody reaction from taken place despite our inclusion of serum complements to facilitate it (Kai and Wang 2020). In addition, it has been suggested that the protein may exist in multiple functional states, highlighting the need for further research (Hu et al. 2016; Kai and Wang 2020).

The successful conjugative transfer of mcr‐1 gene from donor strains to a recipient strain was as expected. Previous studies have demonstrated this mobility of the gene while conferring resistance to an otherwise known susceptible organism (Liu et al. 2016). However, the inability of bambermycin to inhibit the said transfer was unexpected, as studies by Poole et al. (2006) and Riedl et al. (2000) have reported a decrease in rate of plasmid transfer in the presence of bambermycin. Although several mechanisms have been hypothesized to explain the drugs inhibiting effects, an alternate effect of transfer enhancement by the drug depending on plasmid type has also been reported (George and Fagerberg 1984; Kudo et al. 2019). It should also be noted that bambermycin has not been shown to have any effect on vertical transmission of plasmids through cell division. Therefore, it should be expected that trans‐conjugants be able to undergo normal cell division and multiply, especially if there are no fitness cost associated with carrying a plasmid. Perhaps this might explain in part why there are no significant differences in the number trans‐conjugants generated in the present study irrespective of bambermycin inclusion, that is, any effect of the latter on vertical transmission would result in reduction of the number of trans‐conjugants despite the drug's inability to interfere with conjugation. Moreover, the drug may not have had any effect on plasmid types carried by the strains. At this point, with hypothesis being unavailable to explain the effect of bambermycin on plasmid transfer, further speculations as to the reason for study failure is not possible.

5. Conclusion

The synergy demonstrated by colistin/bambermycin combination in vitro potentially suggests that their combination could be useful in the management of colibacillosis not being responsive to colistin chemotherapy. Although bambermycin demonstrated no significant effect on rate of plasmid transfer, the outcome does highlight the need for further studies on its mechanism of action, as both inhibiting and enhancing effects have been documented. In addition, the necessity for further optimization of colistin susceptibility testing protocol was highlighted.

Author Contributions

Vinny Naidoo: conceptualization, methodology, writing – review and editing, supervision, funding acquisition, resources; Ibrahim Zubairu Hassan: methodology, investigation, formal analysis, writing – original draft, review and editing, project administration; Daniel Nenene Qekwana: methodology, formal analysis, writing – review and editing, supervision.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Peer Review

The peer review history for this article is available at https://www.webofscience.com/api/gateway/wos/peer‐review/10.1002/vms3.70519.

Supporting information

Supplementary file.docx

Acknowledgement

We are extremely grateful to the South African Medical Research Council (SIR Grant‐Risk assessment of the use of colistin in poultry medicine on human health in South Africa), the University of Pretoria, and the South African National Research Foundation (I.Z.H. PhD grant) for funding this research.

Funding: This study was supported by the South African Medical Research Council (SIR Grant‐Risk assessment of the use of colistin in poultry medicine on human health in South Africa), the University of Pretoria and the South African National Research Foundation (I.Z.H. PhD grant).

Data Availability Statement

The data that supports the findings of this study are available in the Supporting Information section of this article.

References

- Al‐Hamad, A. , Burnie J., and Upton M.. 2011. “Enhancement of Antibiotic Susceptibility of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia Using a Polyclonal Antibody Developed Against an ABC Multidrug Efflux Pump.” Canadian Journal of Microbiology 57, no. 10: 820–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al‐Tawfiq, J. A. , Laxminarayan R., and Mendelson M.. 2017. “How Should We Respond to the Emergence of Plasmid‐Mediated Colistin Resistance in Humans and Animals?” International Journal of Infectious Diseases 54: 77–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aminov, R. 2017. “History of Antimicrobial Drug Discovery: Major Classes and Health Impact.” Biochemical Pharmacology 133: 4–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Band, V. I. , and Weiss D. S.. 2019. “Heteroresistance: A Cause of Unexplained Antibiotic Treatment Failure?” PLoS Pathogens 15, no. 6: e1007726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow, M. 2009. “What Antimicrobial Resistance Has Taught Us About Horizontal Gene Transfer.” Horizontal Gene Transfer: Genomes in Flux 532: 397–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barros, R. , Vieira S. L., Favero A., et al. 2012. “Reassessing Flavophospholipol Effects on Broiler Performance.” Revista Brasileira De Zootecnia 41: 2458–2462. [Google Scholar]

- Bensink, Z. , and Spradbrow P.. 1999. “Newcastle Disease Virus Strain I2—A Prospective Thermostable Vaccine for Use in Developing Countries.” Veterinary Microbiology 68, no. 1–2: 131–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butaye, P. , Devriese L. A., and Haesebrouck F.. 2003. “Antimicrobial Growth Promoters Used in Animal Feed: Effects of Less Well Known Antibiotics on Gram‐Positive Bacteria.” Clinical Microbiology Reviews 16, no. 2: 175–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavaco, L. , Mordhorst H., and Hendriksen R.. 2016. PCR for Plasmid‐Mediated Colistin Resistance Genes: Mcr‐1 and Mcr‐2 (Multiplex). Protocol Optimized at National Food Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, A. , Chuang Y.‐C., Sun H.‐Y., et al. 2015. “Excess Mortality Associated With Colistin‐Tigecycline Compared With Colistin‐Carbapenem Combination Therapy for Extensively Drug‐Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Bacteremia: A Multicenter Prospective Observational Study.” Critical Care Medicine 43, no. 6: 1194–1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chew, K. L. , La M.‐V., Lin R. T., et al. 2017. “Colistin and Polymyxin B Susceptibility Testing for Carbapenem‐Resistant and Mcr‐Positive Enterobacteriaceae: Comparison of Sensititre, MicroScan, Vitek 2, and Etest With Broth Microdilution.” Journal of Clinical Microbiology 55, no. 9: 2609–2616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coetzee, J. , Corcoran C., Prentice E., et al. 2016. “Emergence of Plasmid‐Mediated Colistin Resistance (MCR‐1) Among Escherichia coli Isolated From South African Patients.” SAMJ: South African Medical Journal 106, no. 5: 449–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Witte, C. , Taminiau B., Flahou B., et al. 2018. “In‐Feed Bambermycin Medication Induces Anti‐Inflammatory Effects and Prevents Parietal Cell Loss Without Influencing Helicobacter Suis Colonization in the Stomach of Mice.” Veterinary Research 49, no. 1: 35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devanga Ragupathi, N. K. , Muthuirulandi Sethuvel D. P., Gajendran R., et al. 2019. “Horizontal Transfer of Antimicrobial Resistance Determinants Among Enteric Pathogens Through Bacterial Conjugation.” Current Microbiology 76: 666–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dijkmans, A. C. , Wilms E. B., Kamerling I. M., et al. 2015. “Colistin: Revival of an Old Polymyxin Antibiotic.” Therapeutic Drug Monitoring 37, no. 4: 419–427. 10.1097/FTD.0000000000000172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fantin, B. , and Carbon C.. 1992. “In Vivo Antibiotic Synergism: Contribution of Animal Models.” Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 36, no. 5: 907–912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, M. R. , Moura Q., Sartori L., et al. 2016. “Silent Dissemination of Colistin‐Resistant Escherichia coli in South America Could Contribute to the Global Spread of the Mcr‐1 Gene.” Eurosurveillance 21, no. 17: 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George, B. , and Fagerberg D.. 1984. “Effect of Bambermycins, In Vitro, on Plasmid‐Mediated Antimicrobial Resistance.” American Journal of Veterinary Research 45, no. 11: 2336–2341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Händel, N. , Otte S., Jonker M., et al. 2015. “Factors That Affect Transfer of the IncI1 β‐Lactam Resistance Plasmid pESBL‐283 Between E. coli Strains.” PLoS ONE 10, no. 4: e0123039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, I. , Wandrag B., Gouws J., et al. 2021. “Antimicrobial Resistance and Mcr‐1 Gene in Escherichia coli Isolated From Poultry Samples Submitted to a Bacteriology Laboratory in South Africa.” Veterinary World 14, no. 10: 2662–2669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, I. Z. , Qekwana D. N., and Naidoo V.. 2023. “Do Pathogenic Escherichia coli Isolated From Gallus gallus in South Africa Carry Co‐Resistance Towards Colistin and Carbapenem Antimicrobials?” Foodborne Pathogens and Disease 20, no. 9: 388–397. 10.1089/fpd.2023.0047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrero, M. , De Lorenzo V., and Timmis K. N.. 1990. “Transposon Vectors Containing Non‐Antibiotic Resistance Selection Markers for Cloning and Stable Chromosomal Insertion of Foreign Genes in Gram‐Negative Bacteria.” Journal of Bacteriology 172, no. 11: 6557–6567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu, M. , Guo J., Cheng Q., et al. 2016. “Crystal Structure of Escherichia coli Originated MCR‐1, a Phosphoethanolamine Transferase for Colistin Resistance.” Scientific Reports 6, no. 1: 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J. , Zhu Y., Han M.‐L., et al. 2018. “Comparative Analysis of Phosphoethanolamine Transferases Involved in Polymyxin Resistance Across 10 Clinically Relevant Gram‐Negative Bacteria.” International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents 51, no. 4: 586–593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayol, A. , Nordmann P., Brink A., et al. 2015. “Heteroresistance to Colistin in Klebsiella pneumoniae Associated With Alterations in the PhoPQ Regulatory System.” Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 59, no. 5: 2780–2784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kai, J. , and Wang S.. 2020. “Recent Progress on Elucidating the Molecular Mechanism of Plasmid‐Mediated Colistin Resistance and Drug Design.” International Microbiology 23, no. 3: 355–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloos, J. M. 2021. Horizontal Transfer, Selection and Maintenance of Antibiotic Resistance Determinants. UiT The Arctic University of Norway. [Google Scholar]

- Kudo, H. , Usui M., Nagafuji W., et al. 2019. “Inhibition Effect of Flavophospholipol on Conjugative Transfer of the Extended‐Spectrum β‐Lactamase and vanA Genes.” Journal of Antibiotics 72, no. 2: 79–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Ragione, R. , Woodward M., Kumar M., et al. 2013. “Efficacy of a Live Attenuated Escherichia coli O78∶ K80 Vaccine in Chickens and Turkeys.” Avian Diseases 57, no. 2: 273–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landman, D. , Salamera J., and Quale J.. 2013. “Irreproducible and Uninterpretable Polymyxin B MICs for Enterobacter cloacae and Enterobacter aerogenes .” Journal of Clinical Microbiology 51, no. 12: 4106–4111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lentz, S. A. , de Lima‐Morales D., Cuppertino V. M., et al. 2016. “Letter to the Editor: Escherichia coli Harbouring Mcr‐1 Gene Isolated From Poultry Not Exposed to Polymyxins in Brazil.” Eurosurveillance 21, no. 26: 30267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.‐Y. , Wang Y., Walsh T. R., et al. 2016. “Emergence of Plasmid‐Mediated Colistin Resistance Mechanism MCR‐1 in Animals and Human Beings in China: A Microbiological and Molecular Biological Study.” Lancet Infectious Diseases 16, no. 2: 161–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorian, V. 2005. Antibiotics in Laboratory Medicine. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Q. , Yu W., Zhou K., et al. 2017. “Molecular Epidemiology and Colistin Resistant Mechanism of Mcr‐Positive and Mcr‐Negative Clinical Isolated Escherichia coli .” Frontiers in Microbiology 8: 2262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda, K. , Chaudhari A. A., and Lee J. H.. 2011. “Evaluation of Safety and Protection Efficacy on cpxR and Lon Deleted Mutant of Salmonella gallinarum as a Live Vaccine Candidate for Fowl Typhoid.” Vaccine 29, no. 4: 668–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mupfunya, C. R. , Qekwana D. N., and Naidoo V.. 2021. “Antimicrobial Use Practices and Resistance in Indicator Bacteria in Communal Cattle in the Mnisi Community, Mpumalanga, South Africa.” Veterinary Medicine and Science 7, no. 1: 112–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napier, B. A. , Band V., Burd E. M., et al. 2014. “Colistin Heteroresistance in Enterobacter cloacae Is Associated With Cross‐Resistance to the Host Antimicrobial Lysozyme.” Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 58, no. 9: 5594–5597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norden, C. W. 1978. “Experimental Osteomyelitis. V. Therapeutic Trials With Oxacillin and Sisomicin Alone and in Combination.” Journal of Infectious Diseases 137, no. 2: 155–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordmann, P. , and Poirel L.. 2016. “Plasmid‐Mediated Colistin Resistance: An Additional Antibiotic Resistance Menace.” Clinical Microbiology and Infection 22, no. 5: 398–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orhan, G. , Bayram A., Zer Y., et al. 2005. “Synergy Tests by E Test and Checkerboard Methods of Antimicrobial Combinations Against Brucella melitensis .” Journal of Clinical Microbiology 43, no. 1: 140–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz de la Rosa, J. M. , Nordmann P., and Poirel L.. 2021. “Antioxidant Molecules as a Source of Mitigation of Antibiotic Resistance Gene Dissemination.” Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 65, no. 6: e02658–e02720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepper, D. J. , Meintjes G. A., McIlleron H., et al. 2007. “Combined Therapy for Tuberculosis and HIV‐1: The Challenge for Drug Discovery.” Drug Discovery Today 12, no. 21–22: 980–989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaller, M. A. 2006. “Flavophospholipol Use in Animals: Positive Implications for Antimicrobial Resistance Based on Its Microbiologic Properties.” Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease 56, no. 2: 115–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poirel, L. , Kieffer N., Brink A., et al. 2016. “Genetic Features of MCR‐1‐Producing Colistin‐Resistant Escherichia coli Isolates in South Africa.” Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 60, no. 7: 4394–4397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole, T. , McReynolds J., Edrington T., et al. 2006. “Effect of Flavophospholipol on Conjugation Frequency Between Escherichia coli Donor and Recipient Pairs In Vitro and in the Chicken Gastrointestinal Tract.” Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 58, no. 2: 359–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qureshi, Z. A. , Hittle L. E., and O'Hara J. A., et al. 2015. “Colistin‐Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii: Beyond Carbapenem Resistance.” Clinical Infectious Diseases 60, no. 9: 1295–1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebelo, A. R. , Bortolaia V., Kjeldgaard J. S., et al. 2018. “Multiplex PCR for Detection of Plasmid‐Mediated Colistin Resistance Determinants, Mcr‐1, Mcr‐2, Mcr‐3, Mcr‐4 and Mcr‐5 for Surveillance Purposes.” Eurosurveillance 23, no. 6: 17–00672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhouma, M. , Beaudry F., Theriault W., et al. 2016. “Colistin in Pig Production: Chemistry, Mechanism of Antibacterial Action, Microbial Resistance Emergence, and One Health Perspectives.” Frontiers in Microbiology 7: 1789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riedl, S. , Ohlsen K., Werner G., et al. 2000. “Impact of Flavophospholipol and Vancomycin on Conjugational Transfer of Vancomycin Resistance Plasmids.” Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 44, no. 11: 3189–3192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sande, M. , and Courtney K.. 1976. “Nafcillin‐Gentamicin Synergism in Experimental Staphylococcal Endocarditis.” Journal of Laboratory and Clinical Medicine 88, no. 1: 118–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sande, M. A. , and Johnson M. L.. 1975. “Antimicrobial Therapy of Experimental Endocarditis Caused by Staphylococcus aureus .” Journal of Infectious Diseases 131, no. 4: 367–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAVC . 2016. Colistin Use by Veterinarians. Official Newsletter of the SAVC. [Google Scholar]

- Tornheim, J. A. , and Dooley K. E.. 2018. “Challenges of TB and HIV Co‐Treatment: Updates and Insights.” Current Opinion in HIV and AIDS 13, no. 6: 486–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO . 2019. Critically Important Antimicrobials for Human Medicine. World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Will, W. R. , and Frost L. S. 2006. “Characterization of the Opposing Roles of H‐NS and TraJ in Transcriptional Regulation of the F‐Plasmid Tra Operon.” Journal of Bacteriology 188, no. 2: 507–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xavier, B. B. , Lammens C., Ruhal R., et al. 2016. “Identification of a Novel Plasmid‐Mediated Colistin‐Resistance Gene, Mcr‐2, in Escherichia coli, Belgium, June 2016.” Eurosurveillance 21, no. 27: 30280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin, W. , Li H., Shen Y., et al. 2017. “Novel Plasmid‐Mediated Colistin Resistance Gene Mcr‐3 in Escherichia coli .” MBio 8, no. 3: e00543–e00617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y. , Walsh T. R., Yang R.‐S., et al. 2019. “Novel Partners With Colistin to Increase Its In Vivo Therapeutic Effectiveness and Prevent the Occurrence of Colistin Resistance in NDM‐and MCR‐Co‐Producing Escherichia coli in a Murine Infection Model.” Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 74, no. 1: 87–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Z. , Qin W., Lin J., et al. 2015. “Antibacterial Mechanisms of Polymyxin and Bacterial Resistance.” BioMed Research International 2015: 679109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary file.docx

Data Availability Statement

The data that supports the findings of this study are available in the Supporting Information section of this article.