Abstract

Recurring interstitial loss of all or part of the long arm of chromosome 5, del(5q), is a hallmark of myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukemia. Although the genes affected by these changes have not been identified, two critically deleted regions (CDRs) are well established. We have identified 76 zebrafish cDNAs orthologous to genes located in these 5q CDRs. Radiation hybrid mapping revealed that 33 of the 76 zebrafish orthologs are clustered in a genomic region on linkage group 14 (LG14). Fifteen others are located on LG21, and two on LG10. Although there are large blocks of conserved syntenies, the gene order between human and zebrafish is extensively inverted and transposed. Thus, intrachromosomal rearrangements and inversions appear to have occurred more frequently than translocations during evolution from a common chordate ancestor. Interestingly, of the 33 orthologs located on LG14, three have duplicates on LG21, suggesting that the duplication event occurred early in the evolution of teleosts. Murine orthologs of human 5q CDR genes are distributed among three chromosomes, 18, 11, and 13. The order of genes within the three syntenic mouse chromosomes appears to be more colinear with the human order, suggesting that translocations occurred more frequently than inversions during mammalian evolution. Our comparative map should enhance understanding of the evolution of the del(5q) chromosomal region. Mutant fish harboring deletions affecting the 5q CDR syntenic region may provide useful animal models for investigating the pathogenesis of myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukemia.

Nonrandom translocations and recurring deletions of specific genomic regions are frequently observed in cases of myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Although the cloning and characterization of fusion genes generated by chromosomal translocations have helped to clarify the pathogenesis of these hematologic malignancies, the contribution of the loss of genes within recurring deletions remains an enigma (1). Interstitial loss of all or part of the long arm of chromosome 5, del(5q), is one of the most frequent somatically occurring clonal chromosomal deletions in MDS and AML (1–3). Approximately 42% of patients with therapy-related MDS/AML (4–6) and 10–15% of those in whom these diseases arise de novo (7, 8) show loss of heterozygosity within the long arm of chromosome 5. Notably, the deletions within 5q are interstitial (4, 5) and occurred early in the development of hematopoietic stem cells (9–11).

Many groups have worked diligently to identify and refine the critical deleted regions (CDRs) on human chromosome 5 and ultimately to identify the tumor suppressor genes in these regions (1–7). Using standard cytogenetic techniques, fluorescence in situ hybridization and loss-of-heterozygosity analysis based on genetic polymorphism, these groups identified two CDRs in MDS/AML. The proximal CDR within chromosome band 5q31 is found in >90% of cases (2–5, 12–15) and was originally defined as the region centromeric to D5S436 and telomeric to IL-9 (4). Subsequent studies refined this commonly deleted region to ≈1.5 Mb, flanked proximally by D5S479 and distally by D5S500 (2, 4). The distal CDR was identified in chromosome bands 5q32-q33. Flanked by the ADRB2 and IL12B genes, it spans up to 3 Mb and is found primarily in patients with 5q− syndrome, a distinct type of MDS characterized by refractory anemia, a favorable prognosis, a low rate of transformation to acute leukemia, and deletion of the 5q region as the sole cytogenetic abnormality (14–18).

Despite reports of increasingly smaller CDRs, attempts to identify tumor suppressor genes in these regions have been unrewarding (1, 19). Studies to identify mutations within retained alleles of genes reduced to hemizygosity, as well as potential submicroscopic homozygous deletions in known CDRs, also have been unproductive (5), suggesting either that haploinsufficiency is adequate to promote myelodysplasia or that the retained tumor suppressor allele has undergone epigenetic inactivation (20, 21). A number of putative tumor suppressor gene candidates from these CDRs have been screened for exon-based mutations by single-strand conformation polymorphism analysis, without success (M. M. Le Beau, personal communication; refs. 19, 22, and 23). If loss of a single allele were sufficient to contribute to the aberrant development of myeloid progenitors (24, 25), one would not expect classical tumor suppressor gene searches, which ultimately rely on detection of a mutation in the undeleted allele, to be an optimal method for identifying tumor suppressor genes.

The zebrafish forward-genetic model offers several unique advantages in defining the role of 5q deletions in MDS/AML pathogenesis. First, hematopoietic genes and signal transduction pathways are highly conserved between humans and zebrafish (26–29). Second, both a genome-wide, γ-irradiation-based method of randomly introducing deletions or mutations and PCR-based identification of genomic fragment-specific deletions are well established in zebrafish (30). Finally, there is considerable evolutionary conservation (synteny) of genomic regions between humans and zebrafish. Some reports estimate an 83.1% frequency of conserved syntenies among the 804 orthologous gene pairs shared by humans and zebrafish, compared to 90.4% for 375 mouse–human gene pairs (31–33) and 40–50% for pufferfish–human syntenies (34).

Here we report the identification and characterization of a zebrafish region on linkage group 14 (LG14) that is syntenic with the entire region of human chromosome 5q, containing both the proximal and distal 5q CDRs most frequently lost in human MDS/AML and 5q− syndrome.

Materials and Methods

Identification and Physical Mapping of the Human 5q CDR.

To construct a physical map of the 5q CDR, we searched the updated database of the human genome draft (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov and http://genome.ucsc.edu). In some instances, the physical map was augmented with previously published findings, which were integrated according to their P1 artificial chromosome (PAC)/bacterial artificial chromosome/yeast artificial chromosome-based physical positions (5, 12, 14, 18, 35, 36).

Zebrafish Genes Orthologous to Genes in Human 5q CDR.

To identify zebrafish–human orthologs, we relied on the “reciprocal best-hit” method, as described (31, 33). In brief, the protein sequences of all genes within human 5q CDRs were compared to a subset of nonredundant zebrafish sequences and the dbest database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/blast.cgi) by using tblastn. The forward search usually generated one of three results: a single zebrafish cDNA [either a characterized gene or an expressed sequence tag (EST) homolog], two related zebrafish cDNAs, or no match with the known zebrafish cDNAs. Thus, it was necessary to perform 3′-untranslated region sequence alignment with dnastar software to exclude the possibility of a contiguous sequence from identical clones. If all clones were unique and noncontiguous, they were considered orthologs of genes located within the human 5q CDRs. Zebrafish genes and ESTs showing the highest level of sequence identity (maximum blast probability, e-20) were further compared against the National Center for Biotechnology Information human nonredundent protein sequence database by blastx reverse searching. The identification of zebrafish orthologs was confirmed if the human genes used in the original search retained their positions as the closest match after the blastx search. Mouse orthologs were identified as described above or by homologgene or unigene database searches (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/UniGene). Map positions were obtained from the mouse genome database (http://www.informatics.jax.org/or http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Homology).

Mapping of Zebrafish Orthologs with a Radiation Hybrid Panel.

Radiation hybrid (RH) mapping was performed on the Goodfellow zebrafish T51 RH panel, which was developed by fusing irradiated zebrafish fin AB9 cells to hamster Wg3H cells (37). In brief, primer pairs are designed from the 3′-untranslated regions of putative orthologous gene or EST sequences obtained from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov and http://zfish.wustl.edu/. Among ESTs of which only 5′ sequences were available, we used 3′-rapid amplification of cDNA ends to obtain 3′ sequences. All primer sequences were selected with oligo 6 software. Each gene or EST was positioned relative to frame markers on the T51 panel by using the samapper 1.0 RH mapping program. Additional mapping information can be found at http://134.174.23.167/zonrhmapper/and http://zfin.org/.

Results

Identification and Mapping of Zebrafish Gene/EST Orthologs Within Human Chromosome 5q CDRs.

Two human 5q CDRs were studied: (i) the proximal chromosome band 5q31 CDR spanning ≈12.4 Mb between IL9 and D5S436, which was subsequently refined to a region spanning ≈1.5 Mb between D5S479 and D5S500 (Fig. 1A) and (ii) the distal 5q32–33.3 CDR spanning ≈11.5 Mb between ADRB2 and IL12B (Fig. 1B). All human genes were placed in order according to the Genome Working Draft (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov and http://genome.ucsc.edu/goldenPath/septTracks.html) and previously published data (5, 12, 14, 18, 35). Altogether, 155 genes were physically mapped and distributed along the region between IL9 and D5S1955: 70 in the proximal 5q31 CDR between IL9 and D5S436, with 19 in the smallest 5q31 CDR (between D5S479 and D5S500), and 79 in the distal 5q32–5q33.3 CDR between ADRB2 and IL12B (Fig. 1 A and B). Six genes are located in the “GAP” region between the proximal and distal CDRs. Seventy-six of these genes had putative zebrafish gene/EST orthologs, whereas 79 did not (Fig. 1). RH mapping localized 33 orthologs within a contiguous region of LG14, of which 17 were orthologs of proximal 5q31 CDR genes, 15 were orthologs of distal 5q32–33.3 CDR genes, and 1 was an ortholog of a gene in the gap between the proximal and distal regions (Fig. 2 Center). All 33 orthologs were encompassed in a region on LG14 flanked by polymorphic markers Z8873 and Z1396, which spans ≈75 cM (Fig. 2 Left). Fifteen additional orthologs were located on LG21 between z5193 and z10508, 11 of which are orthologs of CDR genes on distal chromosome band 5q32–33.3. Two of the genes are located on LG10 and LG6 (Fig. 1 A and B).

Figure 1.

Physical map of the human chromosome 5q CDR and chromosomal localization of zebrafish orthologs. Two critically deleted human chromosome 5q regions (proximal and distal) are shown in A and B. The proximal AML/MDS CDR on chromosome bands 5q31 spans a region between IL9 and D5S436 with the proximal smallest CDR between D5S479 and D5S500 (A, red bar and line). The distal 5q− syndrome CDR spans chromosome bands 5q32–33.3 between ARBB2 and IL12B (Fig. 1B, gray bar). One hundred fifty-five genes and 10 sequence-tagged site (STS) markers are listed according to the updated human genome draft at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/and http://genome.ucsc.edu/(Aug. 2001 version) and previous publications (5, 12, 14, 18, 35, 36). Zebrafish orthologs are listed by clone name for ESTs or accession no. for genes on the right side of the figure. n.a., No available orthologs are found in the current public zebrafish database. The RH mapping positions for 55 zebrafish orthologs are indicated, among which 33 orthologs mapped to LG14, 15 to LG21, 2 to LG10, 2 to LG6, and 1 to LG12. We were unable to map 23 orthologs for technical reasons.

Figure 2.

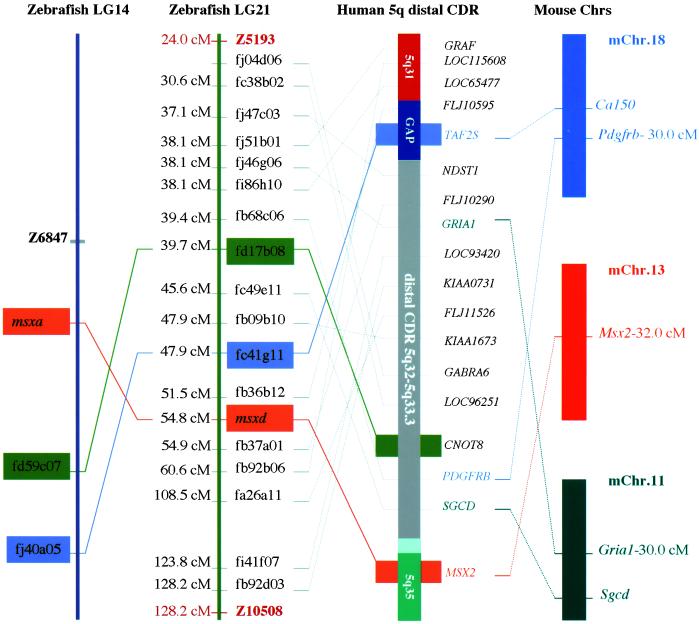

Chromosomal regions in zebrafish and mice syntenic with the proximal and distal human chromosome 5q CDRs. (Left) Thirty-nine zebrafish orthologs of genes within the human chromosome 5q CDR on LG14 are listed according to their RH mapping position between Z8873 and Z1396 (z5qsCDR), where z6847 is a centromere-linked marker. *, Genes with a second duplicated zebrafish gene on LG21 (see Fig. 3). (Center) Human chromosome proximal 5q CDR region (red), distal 5q CDR (gray), and their flanking regions (green). (Right) Mouse syntenic regions and the chromosome positions of murine orthologs in three separate chromosomal regions are shown on the right.

Comparative Analysis and Identification of Zebrafish Genomic Fragments Syntenic to Human 5q CDRs.

Comparative genome mapping relies on the identification of orthologous gene loci in two different species that have descended from a single locus in the last common ancestral organism. Because the lack of full-length ORFs in the zebrafish ESTs precluded phylogenetic tree analysis, we resorted to a reciprocal best-hit search (31, 33) to identify putative orthologs.

Thirty-three zebrafish cDNAs were identified as orthologs of human 5q CDR genes and were distributed on LG14 between Z8873 and Z1396. This region spans 54 Mb (roughly corresponding to 75 cM, based on the 720 kb/cM distance estimated for the sex-averaged map), or approximately twice as long as its human 5q counterpart fragment (≈27 Mb). We termed this region the zebrafish 5q syntenic CDR (z5qsCDR), which contains at least 39 orthologous pairs and is highly syntenic with human 5q31.1–33.3, representing a stretch of DNA that has been conserved since the divergence of human and zebrafish genomes ≈450 million years ago.

The order of genes within this large syntenic region appears to have been reshuffled during evolution (Fig. 2 Left). In general, the upper section of the syntenic region corresponds more closely to the human proximal 5q31 CDR, whereas the middle and lower parts are more syntenic with the distal 5q− syndrome CDR (5q32–33.3). This finding is consistent with the disrupted gene order reported for zebrafish-human syntenies, such as LG17-Hsa 14, LG8-Hsa1, and LG3-Hsa17 (32, 33), indicating that significant intrachromosomal rearrangements and inversions have developed in fish and mammalian lineages since the divergence from their last common ancestor.

We also compared syntenic relationships among humans, mice, and zebrafish (Fig. 2 Right). Although the 5q CDR orthologs have remained largely intact in humans and zebrafish, they are distributed among chromosomes 18, 11, and 13 in mice. This finding should not be considered unusual because another group of genes that has remained intact during the evolution of zebrafish, cats, and humans was fragmented into four chromosomes in the mouse (32). Nonetheless, the order of genes residing in the human 5q CDRs and the three syntenic mouse chromosomes appears to be colinear, consistent with the notion that chromosomal translocations were fixed more frequently than inversions during mammalian evolution (32).

Is the Zebrafish LG21, a Duplicated product of the LG14 Genome Region, Syntenic with the Human 5q CDR?

Previous studies revealed extensive contiguous or interrupted blocks of synteny, but no one-to-one correspondence, between zebrafish and human genomes (31–33). Each zebrafish LG shares conserved syntenies with an average of 4.5 (2–7) human chromosomes (31), whereas each mammalian chromosome shares syntenies with more than one zebrafish LG (33). Consistent with these observations, the human 5q CDR chromosome fragment contains at least two blocks of synteny with zebrafish LG14 (39 genes or ESTs) and LG21 (15 ESTs). In addition, five zebrafish ESTs (fb52g05, fd19g04, fc15e05, fb15a06, and fc66d05) were unexpectedly located on LG10, LG12, and LG6.

It is worth noting that zebrafish orthologs on LG21 are dispersed within the region containing the LG14 orthologs (Fig. 1B). Thus, fragmentation of the human 5q CDR into two zebrafish chromosomes (LG14 and LG21) seems unlikely. A more likely possibility is that LG21 and LG14 are duplicates of each other, both being orthologous to the 5q CDR. In support of this hypothesis, we found two zebrafish orthologs of three single-copy human genes on 5q CDR: MSX2 (30), CNOT8, and TAF2S. One copy of these genes (Msxa, fd59c07 and fj40a05) mapped to LG14 and the other (Msxd, fd17b08 and fc41g11) to LG21 (Fig. 3 Left), indicating that portions of LG21 and LG14 are duplicates of each other. This new LG14–LG21 duplicated chromosome segment, combined with 13 previously identified duplicated segments (33), strongly suggests that genome-wide duplication events occurred and were retained during ray-fin evolution.

Figure 3.

Duplication in zebrafish of the human chromosome 5qsCDR. Eighteen ESTs that are orthologous to human chromosome 5q CDR genes are located on LG21 (genetic distance indicated in cM). Three LG21 zebrafish genes (fd17b08, fc41g11, and Msxd; human orthologs, CNOT8, TAF2S, and MSX2) are duplicates of genes located on LG14. Human chromosome 5q− syndrome CDR (distal CDR) and the mouse chromosome location of corresponding orthologs are also shown.

Discussion

The zebrafish affords a potentially useful model for identifying human tumor suppressor genes relevant to MDS/AML. It offers the advantage of “forward genetics” (39, 40), and there is considerable conservation of genes, signaling pathways, and chromosome fragments (syntenies) between humans and zebrafish (26–29, 31–33). As many as 83% of the orthologous gene pairs are conserved within syntenic chromosomal regions (33). The value of a zebrafish model of tumor suppressor genes deleted in human MDS/AML will depend in part on the level of synteny between human chromosome 5q and previously unidentified genomic regions in the fish.

Of 155 physically positioned genes or protein-coding sequences located on human 5q31–33.3 within the proximal and distal CDRs, we identified 76 genes/ESTs as zebrafish orthologs. RH mapping showed that 33 map to zebrafish LG14 and cluster in the region between Z8873 and Z1396, which we refer to as the z5qsCDR. There also are six additional zebrafish genes/ESTs in this region, raising the total to 39 (Fig. 2 Left). We expect to be able to identify zebrafish orthologs for most of the remaining 79 human 5q CDR genes, as additional zebrafish ESTs and genes are sequenced. It also will be interesting to determine whether any of these orthologs map to the conserved region on LG14.

The orders of loci within the chromosome segments of this block of conserved synteny are quite different between zebrafish and humans. This fact, together with previous work, suggests that chromosomal inversions are fixed in fish and human lineages more often than translocations. By contrast, mouse genomic regions syntenic with the human 5q CDR can be found on chromosomes 18, 11, and 13, but the order of genes is better preserved than in fish. Thus, since their divergence from humans ≈112 million years ago, mice appear to have undergone more rapid genomic evolution than zebrafish, which diverged ≈450 million years ago. This may reflect an increase in chromosomal translocations during murine evolution.

As vertebrates evolved from their early deuterostome ancestor, the entire genome was duplicated through two rounds of duplication (one-to-two-to-four rule) (41). Accumulating evidence suggests further that the fish genome was duplicated a third time to produce up to eight copies of the original deuterostome (one-to-two-to-four-to-eight rule) (42, 43). The third duplication took place after the divergence of two major radiations of jawed vertebrates, consisting of ray-finned fish/actinopterygia (which includes zebrafish) and the sarcopterygian lineage (which includes lungfish and all land vertebrates). The most convincing example comes from research on Hox gene clusters. Tetrapods possess more than 42 Hox genes arranged in four clusters (A–B–C–D), whereas zebrafish have at least 47 genes arranged in seven clusters (AaAb–BaBb–CaCb–Da), suggesting a genome duplication in zebrafish followed by the loss of individual genes and clusters (41, 43).

We found that human 5q CDRs share syntenies with two zebrafish LGs, LG14 and LG21. One interpretation is that LG14 and LG21 are derived from fragmentation of the human 5q CDR orthologs in ray-finned fish. However, because LG21 contains 15 zebrafish EST orthologs, and human orthologs of both LG14 and LG21 are distributed across essentially the same loci, simple fragmentation or translocation seems an unlikely explanation. Further study indicated that of 39 genes on z5qsCDR, three are duplicated (fd59c07–fd17b08, fj40a05–fc41g11, Msxa–Msxd) and all map to LG14 and LG21, as the regional duplication model would predict. Thus, the three duplicated gene pairs provide critical evidence that portions of LG21 and LG14 are duplicates of each other and increase the total of zebrafish–human duplicated gene pairs to 62 (59 were identified previously) (33). This finding, and the observation that 21 of 25 zebrafish LGs contain duplicate segments (33), strongly suggests that the third duplication event ≈450 million years ago could have involved the entire genome.

As noted earlier, duplicates for 36 of the 39 orthologs on LG14 have not yet been identified. This could reflect missing duplicates due to the redundancy of gene function and relaxed selection pressure, the presence of pseudogenes or silencing by mutation (44, 45). However, one could predict that fewer than 92% of the duplicated genes were lost after the duplication event, consistent with current estimates that fewer than 80% of duplicates are missing after the third duplication (33). Once sequencing of the zebrafish genome is completed, direct alignment of chromosome sequences, as applied to the Arabidopsis thaliana genome (46), will offer the best strategy for addressing the questions raised here.

Taken together, our findings suggest that the zebrafish contain highly evolutionarily preserved chromosome fragments orthologous to the human 5q CDR chromosome fragment. Zebrafish mutants harboring deletions that disrupt the z5qsCDR should provide a valuable model to investigate the molecular pathogenesis of AML/MDS, especially, in view of the conservation of myeloid cell development between zebrafish and man (47). Finally, our syntenic map could be used in genomic “ping-ponging” between the human 5q CDR and z5qsCDR, allowing positional cloning of many genes that are mapped to this region.

Acknowledgments

We thank Anne Delahaye-Brown and AnHua Song for technical assistance, John Gilbert for editorial review, and Doris Dodson for assistance with manuscript preparation. This work was supported by a National Institutes of Health Grant CA 93152 and by a Leukemia and Lymphoma Society Center grant.

Abbreviations

- MDS

myelodysplastic syndrome

- AML

acute myeloid leukemia

- CDR

critical deleted region

- RH

radiation hybrid

- LG

linkage group

- z5qsCDR

zebrafish 5q syntenic CDR

- EST

expressed sequence tag

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

References

- 1.Van den Berghe H, Michaux L. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1997;94:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(96)00350-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boultwood J, Fidler C, Lewis S, Kelly S, Sheridan H, Littlewood T J, Buckle V J, Wainscoat J S. Genomics. 1994;19:425–432. doi: 10.1006/geno.1994.1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Willman C L, Sever C E, Pallavicini M G, Harada H, Tanaka N, Slovak M L, Yamamoto H, Harada K, Meeker T C, List A F. Science. 1993;259:968–971. doi: 10.1126/science.8438156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Le Beau M M, Espinosa R, Neuman W L, Stock W, Roulston D, Larson R A, Keinanen M, Westbrook C A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:5484–5488. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.12.5484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhao N, Stoffel A, Wang P W, Eisenbart J D, Espinosa R, Larson R A, Le Beau M M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:6948–6953. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.13.6948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xie D, Hofmann W K, Mori N, Miller C W, Hoelzer D, Koeffler H P. Leukemia. 2000;14:805–810. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Samuels B L, Larson R A, Le Beau M M, Daly K M, Bitter M A, Vardiman J W, Barker C M, Rowley J D, Golomb H M. Leukemia. 1988;2:79–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nimer S D, Golde D W. Blood. 1987;70:1705–1712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van den Berghe H, Vermaelen K, Mecucci C, Barbieri D, Tricot G. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1985;17:189–255. doi: 10.1016/0165-4608(85)90016-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jaju R J, Jones M, Boultwood J, Kelly S, Mason D Y, Wainscoat J S, Kearney L. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2000;29:276–280. doi: 10.1002/1098-2264(2000)9999:9999<::aid-gcc1035>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nilsson L, Astrand-Grundstrom I, Arvidsson I, Jacobsson B, Hellstrom-Lindberg E, Hast R, Jacobsen S E. Blood. 2000;96:2012–2021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Horrigan S K, Arbieva Z H, Xie H Y, Kravarusic J, Fulton N C, Naik H, Le T T, Westbrook C A. Blood. 2000;95:2372–2377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horrigan S K, Westbrook C A, Kim A H, Banerjee M, Stock W, Larson R A. Blood. 1996;88:2665–2670. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fairman J, Chumakov I, Chinault A C, Nowell P C, Nagarajan L. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:7406–7410. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.16.7406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horrigan S K, Bartoloni L, Speer M C, Fulton N, Kravarusic J, Ramesar R, Vance J M, Yamaoka L H, Westbrook C A. Genomics. 1999;57:24–35. doi: 10.1006/geno.1999.5765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jaju R J, Boultwood J, Oliver F J, Kostrzewa M, Fidler C, Parker N, McPherson J D, Morris S W, Muller U, Wainscoat J S, et al. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1998;22:251–256. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2264(199807)22:3<251::aid-gcc11>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boultwood J, Fidler C, Soularue P, Strickson A J, Kostrzewa M, Jaju R J, Cotter F E, Fairweather N, Monaco A P, Muller U, et al. Genomics. 1997;45:88–96. doi: 10.1006/geno.1997.4899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boultwood J, Strickson A J, Jabs E W, Cheng J F, Fidler C, Wainscoat J S. Hum Genet. 2000;106:127–129. doi: 10.1007/s004399900215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lai F, Fernald A A, Zhao N, Le Beau M M. Gene. 2000;248:117–125. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00135-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soengas M S, Capodieci P, Polsky D, Mora J, Esteller M, Opitz-Araya X, McCombie R, Herman J G, Gerald W L, Lazebnik Y A, et al. Nature (London) 2001;409:207–211. doi: 10.1038/35051606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Teitz T, Wei T, Valentine M B, Vanin E F, Grenet J, Valentine V A, Behm F G, Look A T, Lahti J M, Kidd V J. Nat Med. 2000;6:529–535. doi: 10.1038/75007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lai F, Orelli B J, Till B G, Godley L A, Fernald A A, Pamintuan L, Le Beau M M. Genomics. 2000;66:65–75. doi: 10.1006/geno.2000.6181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Godley L A, Lai F, Liu J, Zhao N, Le Beau M M. Genomics. 1999;60:226–233. doi: 10.1006/geno.1999.5912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fero M L, Randel E, Gurley K E, Roberts J M, Kemp C J. Nature (London) 1998;396:177–180. doi: 10.1038/24179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Song W J, Sullivan M G, Legare R D, Hutchings S, Tan X, Kufrin D, Ratajczak J, Resende I C, Haworth C, Hock R, et al. Nat Genet. 1999;23:166–175. doi: 10.1038/13793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Donovan A, Brownlie A, Zhou Y, Shepard J, Pratt S J, Moynihan J, Paw B H, Drejer A, Barut B, Zapata A, et al. Nature (London) 2000;403:776–781. doi: 10.1038/35001596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Amatruda J F, Zon L I. Dev Biol. 1999;216:1–15. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang H, Long Q, Marty S D, Sassa S, Lin S. Nat Genet. 1998;20:239–243. doi: 10.1038/3041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brownlie A, Donovan A, Pratt S J, Paw B H, Oates A C, Brugnara C, Witkowska H E, Sassa S, Zon L I. Nat Genet. 1998;20:244–250. doi: 10.1038/3049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fritz A, Rozowski M, Walker C, Westerfield M. Genetics. 1996;144:1735–1745. doi: 10.1093/genetics/144.4.1735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barbazuk W B, Korf I, Kadavi C, Heyen J, Tate S, Wun E, Bedell J A, McPherson J D, Johnson S L. Genome Res. 2000;10:1351–1358. doi: 10.1101/gr.144700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Postlethwait J H, Woods I G, Ngo-Hazelett P, Yan Y L, Kelly P D, Chu F, Huang H, Hill-Force A, Talbot W S. Genome Res. 2000;10:1890–1902. doi: 10.1101/gr.164800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Woods I G, Kelly P D, Chu F, Ngo-Hazelett P, Yan Y L, Huang H, Postlethwait J H, Talbot W S. Genome Res. 2000;10:1903–1914. doi: 10.1101/gr.10.12.1903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McLysaght A, Enright A J, Skrabanek L, Wolfe K H. Yeast. 2000;17:22–36. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(200004)17:1<22::AID-YEA5>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boultwood J, Fidler C, Strickson A J, Watkins F, Kostrzewa M, Jaju R J, Muller U, Wainscoat J S. Genomics. 2000;66:26–34. doi: 10.1006/geno.2000.6193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Borkhardt A, Bojesen S, Haas O A, Fuchs U, Bartelheimer D, Loncarevic I F, Bohle R M, Harbott J, Repp R, Jaeger U, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:9168–9173. doi: 10.1073/pnas.150079597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Geisler R, Rauch G J, Baier H, van Bebber F, Brobeta L, Dekens M P, Finger K, Fricke C, Gates M A, Geiger H, et al. Nat Genet. 1999;23:86–89. doi: 10.1038/12692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moens C B, Cordes S P, Giorgianni M W, Barsh G S, Kimmel C B. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1998;125:381–391. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.3.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vogel G. Science. 2000;288:1160–1161. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5469.1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aldhous P. Nature (London) 2000;404:910. doi: 10.1038/35010215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Meyer A, Schartl M. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1999;11:699–704. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(99)00039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Prince V E, Joly L, Ekker M, Ho R K. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1998;125:407–420. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.3.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Amores A, Force A, Yan Y L, Joly L, Amemiya C, Fritz A, Ho R K, Langeland J, Prince V, Wang Y L, et al. Science. 1998;282:1711–1714. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5394.1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wagner A. BioEssays. 1998;20:785–788. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199810)20:10<785::AID-BIES2>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Force A, Lynch M, Pickett F B, Amores A, Yan Y L, Postlethwait J. Genetics. 1999;151:1531–1545. doi: 10.1093/genetics/151.4.1531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.The Arabidopsis Genome Initiative. Nature (London) 2000;408:796–815. doi: 10.1038/35048692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bennett C M, Kanki J P, Rhodes J, Liu T X, Paw B H, Kieran M W, Langenau D M, Delahaye-Brown A, Zon L I, Fleming M D, et al. Blood. 2001;98:643–651. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.3.643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]