Abstract

In this study, we propose a novel improved Dung Beetle Optimizer called Environment-aware Chaotic Force-field Dung Beetle Optimizer (ECFDBO). To address DBO’s existing tendency toward premature convergence and insufficient precision in high-dimensional, complex search spaces, ECFDBO integrates three key improvements: a chaotic perturbation-based nonlinear contraction strategy, an intelligent boundary-handling mechanism, and a dynamic attraction–repulsion force-field mutation. These improvements reinforce both the algorithm’s global exploration capability and its local exploitation accuracy. We conducted 30 independent runs of ECFDBO on the CEC2017 benchmark suite. Compared with seven classical and novel metaheuristic algorithms, ECFDBO achieved statistically significant improvements in multiple performance metrics. Moreover, by varying problem dimensionality, we demonstrated its robust global optimization capability for increasingly challenging tasks. We further conducted the Wilcoxon and Friedman tests to assess the significance of performance differences of the algorithms and to establish an overall ranking. Finally, ECFDBO was applied to a 3D path planning simulation in UAVs for safe path planning in complex environments. Against both the Dung Beetle Optimizer and a multi-strategy DBO (GODBO) algorithm, ECFDBO met the global optimality requirements for cooperative UAV planning and showed strong potential for high-dimensional global optimization applications.

Keywords: dung beetle optimizer, improvement strategies, CEC2017, path planning, cooperative UAVs

1. Introduction

Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) have experienced rapid development and have been widely deployed in various domains since their inception. UAVs have been applied in such specialized areas as soil information collection and irrigation decision support in agriculture [1], deterring birds, connecting nodes in communication networks, monitoring the marine environment [2], and urban planning [3]. Three-dimensional (3D) path planning is a critical component of autonomous UAV missions, as it directly determines whether a UAV can navigate complex environments safely and efficiently to reach its destination [4]. An optimized flight path must not only avoid terrain obstacles but also minimize travel distance while adhering to the dynamic constraints of the aircraft. These requirements make path planning particularly challenging in 3D spaces with complex terrain and numerous static obstacles [5]. It is also essential to consider flight altitude, camera angle, overlap rate, and obstacle avoidance to enable comprehensive 3D observation and accurate modeling, especially in areas with varying topography or dense urban structures [6,7,8,9].

Among the classical global path planning algorithms, the grid-based search methods (e.g., A*) are capable of finding the optimal paths in static environments, but they incur large memory overhead and are sensitive to the environment scale, making them unsuitable for planning in vast 3D space [10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. The artificial potential field methods are highly respected for their simplicity and computational speed, and have been used for UAV obstacle avoidance; however, pure potential field methods do not guarantee global optimality and are prone to falling into local minima in complex terrains, leading the path to ‘deadlocks’ [17,18]. Another class of sampling-based expansion algorithms, namely Rapidly exploring Random Trees (RRT) and its improved variant RRT*, can effectively expand paths in continuous space, but RRT makes it difficult to strike a balance between path optimality and obstacle safety, thus may still produce excessively long or non-smooth paths [19]. To address these problems, researchers have proposed various improvements to RRT; for example, Guo et al. introduced a fuzzy control strategy to optimize the sampling process and developed the FC-RRT* algorithm to improve search efficiency and safety in complex 3D environments [20]. In conclusion, traditional algorithms often face such problems as high computational costs and being prone to falling into suboptimal solutions in challenging terrains and scenarios with many obstacles.

In recent years, intelligent optimization algorithms have been increasingly applied in UAV path planning owing to their strong global search capabilities [21]. Genetic algorithms (GA), which are naturally adept at multi-objective optimization, have been employed in planning UAV paths under multiple tasks or constraints. For example, Pehlivanoglu et al. devised an improved GA for UAV coverage missions [22]. Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) algorithms [23,24] have gained widespread attention because of their fast convergence and small number of parameters. Researchers have proposed numerous variants tailored to UAV path-planning needs, including phase-angle-encoded PSO [25,26,27], quantum-behaved PSO [28], and discrete PSO [29,30]. Differential evolution (DE) algorithms excel in global search capability, and some scholars have proposed hybrid DE algorithms in combination with strategies such as grey wolf optimization to plan 3D paths in complex mountainous terrain [31]. Additionally, swarm intelligence methods like Ant Colony Optimization (ACO) [32] and Artificial Bee Colony (ABC) [33] have been applied to UAV obstacle-avoidance path planning. However, single-strategy meta-heuristics often suffer from getting trapped in local optima or lacking sufficient convergence precision. Original PSO, for instance, is prone to converge prematurely, while ACO’s communication-based modeling incurs substantial computational overhead, limiting its real-time application [34]. In addition, researchers have explored various types of plants, animals, and insects in nature and invented various meta-heuristic algorithms. Inspired by the foraging behavior of coatis, Dehghani M et al. proposed the Coati Optimization Algorithm (COA) [35]. Arora S et al. modeled the food search and mating behavior of butterflies and proposed and tested the Butterfly Optimization Algorithm (BOA) [36] based on the foraging strategy of butterflies. Zhong et al. proposed the Beluga Whale Optimization (BWO) algorithm, inspired by the collective behavior of beluga whales [37]. Duan and Qiao introduced the Pigeon-Inspired Optimization (PIO) algorithm, based on the navigational behavior of pigeon flocks. PIO has been successfully applied to flight-robot path planning [38]. Recently, the Nutcracker Optimization Algorithm (NOA) was proposed, simulating the spatial memory and random foraging behavior of nutcracker birds in their seed search, caching, and retrieval process [39]. Liu and Cai et al. proposed a hybrid multi-strategy artificial rabbit optimization (HARO) [40]; by simulating spherical and cylindrical obstacle models, they achieved efficient and stable UAV path planning in complex environments. Therefore, these advancements highlight an emerging research focus: refining algorithms to meet the specific demands of UAV path planning by striking a more effective balance between global exploration capability and local optimization precision.

In response to the above optimization requirements, Dung Beetle Optimizer (DBO) offers a novel perspective for UAV path planning. First proposed by Xue and Shen in 2022 [41], DBO draws inspiration from the behavioral patterns of dung beetles, incorporating five typical behavioral mechanisms—rolling, dancing, foraging, stealing, and reproducing. When applied to three examples of engineering optimization, DBO also achieved superior results compared to benchmark algorithms; the potential of it for practical applications is further confirmed. Owing to these advantages, DBO has attracted increasing attention in the field of path planning and is considered a promising approach for solving complex optimization tasks such as 3D UAV path planning.

Despite the strong performance of the original DBO, subsequent research has revealed certain limitations when the algorithm is applied to high-dimensional and complex search spaces. Responding to these shortcomings, scholars have proposed several enhanced variants of the Dung Beetle Optimizer. For single-UAV path planning, Shen et al. introduced the Multi-strategy Dung Beetle Optimizer (MDBO) [42]. In 2024, Tang et al. proposed RCDBO, an enhanced DBO variant for robotic path planning [43]. Another notable variant is GODBO, introduced by Wang et al. [44], which enhances exploration through opposition-based learning and multiple strategies centered on the current best solution. Results indicated clear improvements in both convergence precision and speed. Similarly, SSTDBO, proposed by Hu et al. [45], was designed to overcome the original DBO’s deficiencies in population diversity, global detection ability, and convergence precision.

For multi-UAV cooperative planning, Zhang et al. proposed the Multi-strategy Improved Dung Beetle Optimizer (MIDBO) for UAV task allocation [46]. In another study, Shen Q. et al. extended DBO to the multi-objective optimization domain by introducing the Directed Evolution Non-dominated Sorting Dung Beetle Optimizer (DENSDBO-ASR) [47]. This algorithm was applied to cooperative multi-UAV path planning and achieved excellent results in both convergence precision and solution set diversity. Collectively, these enhancements demonstrate that integrating chaos theory, evolutionary operators, and distribution-based mechanisms can substantially boost the performance of DBO, making it more suitable for high-dimensional and complex path-planning tasks.

Many researchers have proposed various DBO improvement algorithms, such as MDBO, SSTDBO, and GODBO. However, there are still some problems that need to be solved in high-dimensional, complex search spaces and in actual UAV 3D path planning tasks. For example, SSTDBO can maintain population diversity in the early stages of the search, but it easily falls into local optima due to the fast convergence of strategies, especially in scenarios with more than 50 dimensions. The premature convergence of the algorithm is especially obvious. Second, MDBO is prone to premature population convergence in high-dimensional, complex environments, making it difficult to escape local optima. Furthermore, GODBO enhances exploration capability by applying multi-strategy learning to the current optimal solution. However, it struggles to escape local optimization in multi-constraint UAVs. GODBO enhances exploration capability by applying multi-policy learning to the current optimal solution. However, it exhibits high computational overhead in multi-constraint UAV tasks, affecting the algorithm’s real-time performance and practicality.

In summary, the Dung Beetle Optimizer offers both advantages and limitations in UAV path planning. On the one hand, DBO integrates diverse biological behavior mechanisms, which makes DBO have strong global exploration and local exploitation capabilities. Particularly, strategy-enhanced variants of DBO have shown improved adaptability to complex terrain, enabling safer and more efficient path planning in large-scale 3D environments [48]. On the other hand, the original DBO is still prone to premature convergence and becoming trapped in local optima. In environments with complex obstacle distributions, this can lead to insufficient search diversity and difficulty escaping suboptimal regions [49]. Furthermore, as UAV path planning is inherently a high-dimensional optimization problem, the computational cost of DBO increases with problem scale, making it essential to balance convergence speed and algorithm efficiency in practical applications. For these challenges, we propose a novel improved DBO variant for 3D UAV path planning in environments with complex terrain and static obstacles. The algorithm integrates three core strategies: nonlinear contraction of chaotic perturbation, which significantly inhibits premature convergence; an intelligent boundary-handling mechanism that realizes an “energy wall” rebound at the obstacle boundary in a gradient-guided manner to improve the algorithm’s ability to adapt to a dynamic environment; and an attraction-repulsion force-field variability strategy that adjusts adaptively with iterations. This strategy effectively balances global search and local development, resulting in better convergence accuracy and computational efficiency for high-dimensional complex problems and multi-constraint UAV path planning. This study makes the following specific contributions:

An Environment-aware Chaotic Force–field Dung Beetle Optimizer (ECFDBO) is proposed by us, which augments the original Dung Beetle Optimizer (DBO) with three novel improvement strategies: chaotic perturbation mixed nonlinear contraction, environment-aware boundary handling, and dynamic attraction–repulsion field mutation. It ensures stable performance in high-dimensional search spaces.

ECFDBO was subjected to multi-perspective, multi-run experiments by us on the CEC2017 (Dim = 30, 50, and 100) suite to assess its robustness and effectiveness. Wilcoxon and Friedman’s tests demonstrate that ECFDBO’s performance differences among seven state-of-the-art metaheuristics are statistically significant.

We formulate the multi-UAV coordination task as a multi-constrained optimization problem with several key constraints based on the application of UAV tasks in remote sensing. Additionally, we apply the cooperative path-planning model to four distinct environments to validate its simulated effectiveness.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 reviews the preliminary knowledge of the original DBO algorithm. Section 3 details the three novel improvement mechanisms introduced in ECFDBO. Section 4 analyzes the computational complexity of the proposed algorithm. Section 5 presents benchmark results on the CEC2017 suite and accompanying statistical tests. Section 6 describes the UAV simulation experiments and discusses the results. Section 7 concludes the paper and outlines directions for future work.

2. Preliminary Knowledge

The DBO algorithm is derived from the survival behavior of dung beetles in their natural environment. The algorithm plays an important role in achieving global dominance by simulating the rolling of a dung ball by a beetle and the subsequent redirection of movement by implementing a dancing behavior. The beetles adopt this behavior when encountering obstacles, thus preventing falling into local traps. Female dung beetles establish a localized exploration area by hiding dung balls and laying eggs. Following this initial foraging behavior, the young dung beetles mimic the adults and thus perform a fine search in a small area. Finally, competitive behavior occurs between individuals, accelerating the approach to the optimal solution. This phenomenon is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Dung Beetle Optimizer.

2.1. Population Initialization

The Dung Beetle Optimizer initializes its population in a randomized manner, where each dung beetle’s position corresponds to a potential solution to the optimization problem. For the dimensional optimization problem, the position of the -th dung beetle is denoted as , and the population of dung beetles of size can be denoted as , as shown in Equation (1).

| (1) |

2.2. Rolling Stage

2.2.1. Obstacle-Free Mode

In the absence of obstacles, a rolling dung beetle simulates its natural counterpart by carrying a dung ball multiple times its size on its back and moving in a straight line in flat or slightly undulating terrain with the help of sun or moonlight. This phase focuses on “covering a wider search space with large steps.” The ball’s position is updated according to Equation (2).

| (2) |

where simulates the inertia of the dung beetle continuing in its original direction, is randomly selected to reflect small deflections in the rolling direction due to natural disturbances such as wind and terrain, , are the current worst individual locations, which encourages the dung beetle to move away from the inferior region by increasing the distance to the worst solution, and maintains the continuity of the algorithm in the current optimal neighborhood.

2.2.2. Obstacle Mode

When a dung beetle encounters an obstacle during rolling and cannot continue in its original direction, it performs a “dancing” behavior—rotating on its dung ball and pausing momentarily to recalibrate its path. The position update rule corresponding to this dancing behavior is defined in Equation (3).

| (3) |

It has been demonstrated that the magnitude of the movement in the new direction is proportional to the difference between the two positions of the dung beetle before and after. Furthermore, the value of takes on a characteristic that produces diversity from zero deflection to large steering. This helps the algorithm to jump out of the trap and avoid falling into local optimization.

2.3. Reproduction Behavior

Female dung beetles will set aside a safe spawning area for their young within a certain distance from the main path of the colony—close to the food source but avoiding detection by predators. The algorithm dynamically defines the upper and lower boundaries of the spawning area centered on the current local optimal position , as shown in Equation (4).

| (4) |

where ; , denote the lower and upper bounds of the optimization problem; as the iteration advances ( decreases gradually), the spawning area shrinks from a wide area to a narrow area, which is conducive to fine mining near the optimal solution. A single spawn location is generated per iteration, as shown in Equation (5).

| (5) |

where is the position information of the -th spawn ball at the -th iteration; and are two independent random vectors of size . Egg balls are strictly confined to spawning areas.

2.4. Foraging Behavior

Some of the dung beetles leave the spawning area to forage on the ground, representing the algorithm’s diverse and smaller step-size fine search around the high-quality area. It also dynamically defines the foraging area centered on the global optimization , as shown in Equation (6).

| (6) |

where , are the lower and upper bounds of the optimal foraging area, respectively. The position of the small dung beetle is updated by measuring normal perturbation and linear interpolation, as shown in Equation (7).

| (7) |

where is a random number following a normal distribution; is a random vector in the range .

2.5. Stealing Behavior

In high-density areas, some dung beetles attempt to “steal” dung balls from others to quickly acquire resources. In the algorithm, this behavior corresponds to a jump-based position update that drives individuals toward convergence on the global best solution. The position update rule for this stealing behavior is defined in Equation (8).

| (8) |

where is a random vector of size obeying a normal distribution and is a constant controlling the jump amplitude. Pseudo code such as the Algorithm 1.

The Pseudo-Code of DBO:

| Algorithm 1: DBO (Dung Beetle Optimizer) |

| Input: population size: N; problem dimension: d; search boundary: [lb, ub]; maximum number of iterations: Tmax; fitness function: f(x) Output: Optimal position: Xbest |

| 1: Initialize Xi ∼ Uniform(lb, ub) for i = 1…N ←Calculated using Equation (1) 2: Evaluate fi = f(Xi), set Xbest = argmin fi, Xworst = argmax fi 3: for t = 1 to Tmax do 4: p = ⌊0.2·N⌋ 5: // Rolling stage 6: for i = 1 to p do 7: if rand() < 0.9 then 8: Xi ←Calculated using Equation (2) 9: else 10: Xi ←Calculated using Equation (3) 11: end if 12: end for 13: // Reproduction stage 14: R = 1 − t/Tmax 15: [Lb*, Ub*] ←Calculated using Equation (4) 16: for i = p + 1 to p + m do 17: Xi ←Calculated using Equation (5) 18: end for 19: // Foraging stage 20: for i = p + m+1 to p + m+q do 21: Xi ←Calculated using Equation (6) 22: end for 23: // Stealing stage 24: for i = p + m+q + 1 to N do 25: Xi ←Calculated using Equation (7) 26: end for 27: // Boundary check 28: for i = 1 to N do 29: Xi = clip(Xi, lb, ub) 30: end for 31: Evaluate all fi, update Xbest, Xworst 32: end for 33: return Xbest |

3. Proposed Algorithm

According to the No Free Lunch theorem [50], different algorithms perform variably on different problems, so there is a continual need for novel optimization strategies in academic research.

3.1. Chaotic Perturbation Mixed Nonlinear Contraction Mechanisms

In the ecological behavior of dung beetles, real individuals exhibit remarkable dynamic spatial adaptability. When a population cooperates around a core resource (the dung ball), its range of activity follows a spiral contraction pattern, gradually shrinking over time. This spatial focusing strategy creates a negatively correlated feedback mechanism with an individual’s energy reserves, causing their radius of motion to decrease at a nonlinear rate, showing a preferential guarding of vested resources and conservative local search behavior.

Inspired by this, a chaotic perturbation–based nonlinear contraction mechanism is designed to enhance the foraging behavior in the algorithm. The specific update rule is provided in Equation (9).

| (9) |

| (10) |

| (11) |

is the nonlinear shrinkage factor; is the chaotic perturbation factor; is the shrinkage strength parameter; is the attenuation factor; denotes the current iteration optimal solution; is the globally optimal solution; maps random numbers to smooth bounded ranges to avoid oscillations due to large step sizes. controls the steepness of the curve, with larger values of being more sensitive to small changes. Exponential decay term : Suppresses the step size of large -values, creating a “small step size for high frequency, large step size for low frequency” search pattern.

The generates a non-monotonic and asymmetric perturbation pattern within the interval , producing differentiated disturbance intensities at positions and . Compared with other chaotic mappings, this approach has lower computational cost and does not require iterative sequence generation. The use of two independent random variables (one governing the perturbation strength and the other controlling the search direction) forms a two-dimensional probabilistic space, which adds a broader range of search patterns than would be possible with a single random number. This design has proven effective in overcoming local optima in constrained search corridors.

3.2. Environment-Aware Boundary-Handling Strategy

In the original DBO algorithm, when an individual violates the search boundary, a simple truncation or directly setting the transboundary component to a boundary value is often used to ensure feasibility. There are two main problems with this approach: information loss: directly “trimming” individuals may destroy their original directional and positional information, especially in the critical region, which may lead to some valuable search information being ignored; and too much randomness: the lack of directional guidance when resetting to the boundary may destroy convergence.

Inspired by this, we designed an environment-aware boundary-handling strategy that treats the boundary as an “energy wall” and intelligently rebounds particles along the gradient field upon collision, using a three-phase process: collision detection (identifying the transgressed dimension), gradient sensing (calculating the gradient of the objective function at the boundary), and intelligent rebounding (adjusting the position along the direction of gradient descent). Specifically, as in Equation (12):

For individual in dimension transgression:

| (12) |

The center difference method is used to avoid double counting:

| (13) |

where : rebound factor; : gradient direction in the dimension; : unit vector in the dimension; : minor perturbation.

This environment-aware boundary-handling strategy significantly enhances the performance of the optimization algorithm on constrained problems through a gradient-guided intelligent rebound mechanism. On the one hand, by maintaining the directionality of the search, particles rebound along the direction of the gradient of the objective function when they cross the boundary, thus avoiding the loss of information caused by the traditional random reset, and prompting the search process to always be directed toward the favorable region; on the other hand, through the adaptive step-size adjustment, the fine search is conducted near the boundary in order to enhance the exploitation of the boundary region, effectively avoiding the premature convergence and at the same time maintaining the diversity of the populations.

3.3. Dynamic Attraction–Repulsion Force-Field Mutation Strategy

The original DBO algorithm relies only on attraction to the global optimal solution, which leads to rapid population aggregation and loss of diversity, thereby increasing the risk of premature convergence. Moreover, all dimensions are updated synchronously, which cannot deal with nonlinear correlation between variables, and the fixed or linear decay step mechanism is difficult to adapt to the demand of multi-stage optimization.

Based on this, a dynamic attraction–repulsion force field strategy is designed: the suboptimal solution with the top 10% fitness is selected as the source of repulsion so that the algorithm is able to perform a fine local search when it is close to the global optimization, and at the same time the repulsion force is utilized to prevent premature aggregation and maintain population diversity. The repulsive force strength is enhanced with iterations as specified in Equation (14):

| (14) |

Intelligent mutation rules:

| (15) |

where is the time-varying attractive weight; is the time-varying repulsive weight; is the set of suboptimal solutions in the top of fitness; is the nonlinear step size; is the adaptive factors perturbation; this strategy is favorable in the weak-field region (): fine search with small step sizes; and in the strong-field region (): fast moving with large step sizes. In the case of the multiple-peak function: the repulsive field effectively prevents premature convergence, and in the case of the single-peak function: the attractive field accelerates the convergence rate. Pseudo code such as the Algorithm 2.

The Pseudo-Code of ECFDBO:

| Algorithm 2: ECFDBO (Environment-aware Chaotic Force-field Dung Beetle Optimizer) |

| Input: population size: N; problem dimension: d; search boundary: [lb, ub]; maximum number of iterations: Tmax; fitness function: f(x) Output: Optimal position: Xbest |

| 1: Initialize {Xi}₁ⁿ ∼ Uniform (lb, ub) 2: Evaluate fi, set Xbest 3: for t = 1…Tmax do 4: // Construct the set of suboptimal solutions Q 5: Sort {Xi} by fitness, let Q ← best K = max (3, ⌊0.1·N⌋) 6: for each i = 1…N do 7: Compute 8: Fi ← Fg − Fr← Calculated using Equation (14) 9: if rand () < pm then 10: η ←Calculated using Equation (15) 11: Xi ←Attraction–Repulsion Mutation 12: else 13: // Chaos Steps Update 14: Xi ← Calculated using Equation (9) 15: end if 16: Xi ← SmartReflect(Xi, lb, ub, ε) ← Calculated using Equation (12) 17: end for 18: {Xi}← DBO_ Stage({Xi}) // Rolling, Reproduction, Foraging, Stealing 19: Evaluate all fi, update Xbest 20: end for 21: return Xbest |

4. Complexity Analysis

The time complexity is an important index of the computational efficiency of the algorithm, assuming that the population size is , the problem dimension is , and the number of iterations is . The complexity of the original DBO algorithm is mainly influenced by the population initialization complexity () and the complexity of the iteration process (), and the time complexity of the DBO algorithm is shown in Equation (16).

| (16) |

ECFDBO adds three key strategies to the original DBO algorithm. The total complexity of its dynamic attraction–repulsion variation strategy: , where are suboptimal solutions; the complexity of the individual behavior update: ; and the complexity of the environment-aware boundary processing strategy: , where is the time complexity of a single adaptation. For each updated individual, it is necessary to check whether variables are out of bounds and correct them, but usually the proportion of out-of-bounds individuals is limited and the actual complexity is far less than the upper bound, so the time complexity can be approximated as . The ECFDBO time complexity is calculated as shown in Equation (17)

| (17) |

From the analysis, it is evident that the complexity of ECFDBO increases from linear to quadratic growth of the original algorithm, primarily due to the attraction–repulsion field. Despite the increase in time complexity, this increase is acceptable under modern computing conditions. The introduced strategy reduces the probability of the algorithm falling into a local optimization and improves the overall convergence performance so that the increased time cost in exchange for a significant improvement in performance is reasonable and worthwhile in most practical optimization scenarios.

5. CEC2017 Test

The CEC series of test suites, recommended by the IEEE CEC Conference, has become a standard evaluation platform in swarm intelligence and evolutionary algorithms, ensuring fair and reproducible comparisons among different algorithms. In order to fully evaluate ECFDBO’s performance advantages, ECFDBO algorithms, and some classical and novel meta-heuristic algorithms are compared based on the CEC2017 test suite, which has wide recognition. All experiments of this research work were performed on Windows 10 64-bit, Intel(R) Core (TM) i5-12400 processor (2.50 GHz), 16 GB RAM, and MATLAB R2023a.

5.1. CEC2017 Introduction

The CEC2017 test suite aims to provide a fair and systematic performance evaluation of the newly proposed optimization algorithms. The test suite contains 29 standardized single-objective real-parameter optimization functions (the F2 function has been officially removed due to instability), including two single-peak functions (F1–F3) to test the global convergence capability of the algorithm; seven multi-peak functions (F4–F10) to test the global exploration capability of the algorithm; ten hybrid functions (F11–F20) to evaluate the performance of the algorithm by combining different basis functions; and 10 composition functions (F21–F30) to test the robustness and adaptability of the algorithm to highly complex and nonlinear problems. Both simple convex functions are covered, and high-dimensional complex combinations are introduced to ensure the reliable performance of the algorithm in diverse search spaces. The shift and rotation transformations are applied to all basis functions, and the search domain is uniformly set to: to force the algorithm to find the optimal solution in a large range.

5.2. Comparison with Mainstream Optimization Algorithms

In order to facilitate the testing of the convergence capability, global exploitation capability, and robustness of the new improved algorithm, a total of seven comparison algorithms are compared and analyzed on the CEC2017 test component using five novel metaheuristic algorithms, namely BWO [37], COA [35], PIO [38], BOA [36], and NOA [39], as well as the original DBO [41] algorithm and a novel variant of DBO, namely GODBO [44]. Parameter settings are shown in Table 1. The test parameters are 30 populations, 500 iterations, and 30, 50, and 100 dimensions, and the results are evaluated on five performance indicators: mean, standard deviation, best, median, and worst. The optimal solution for each function is shown in bold.

Table 1.

Parameter settings.

| Algorithm | Parameter |

|---|---|

| ECFDBO | = 0.07 |

| BWO | = 0.1, = (1 − 0.5 × t/iter)× rand, = 3/2, = 0.05 |

| COA | No internal hyperparameters |

| PIO | = Maxiter − Nc1 |

| BOA | = 0.8, = 0.1, = 0.01 |

| NOA | = 0.2 |

| GODBO | = 0.2, = 1.25 |

| DBO | = 0.2 |

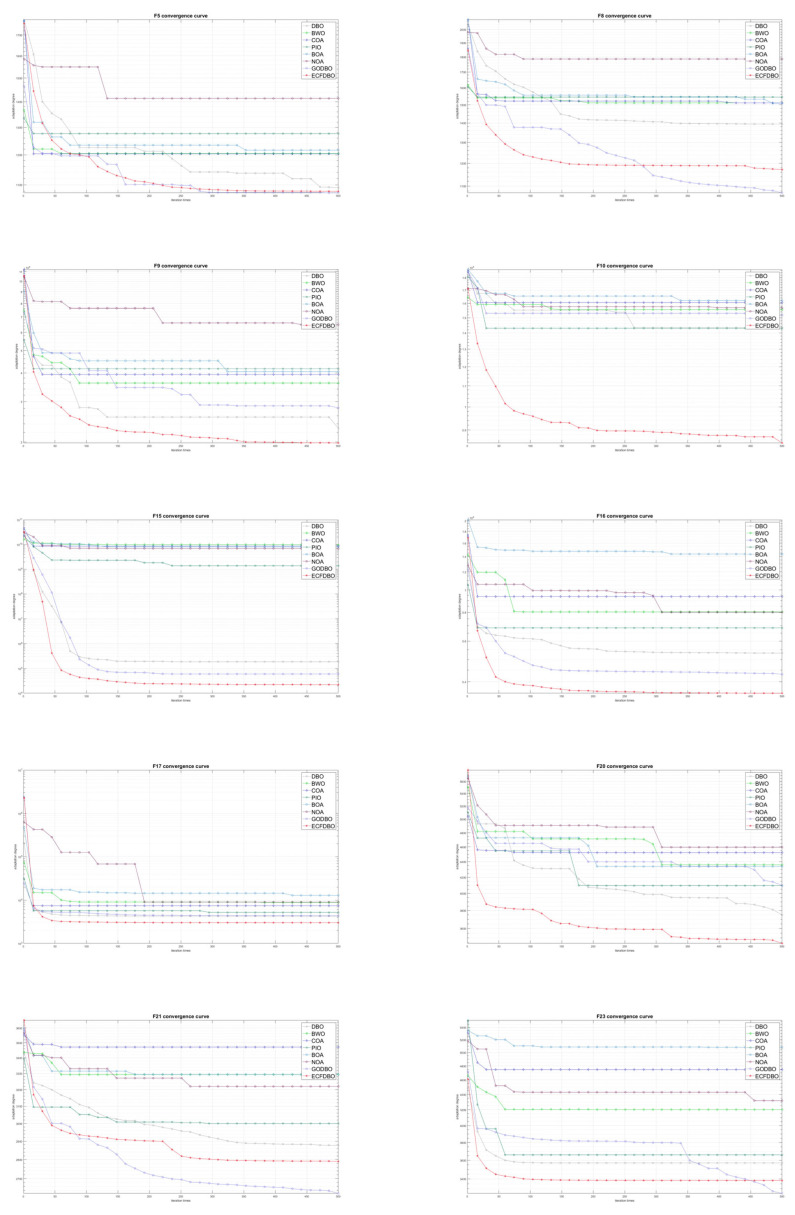

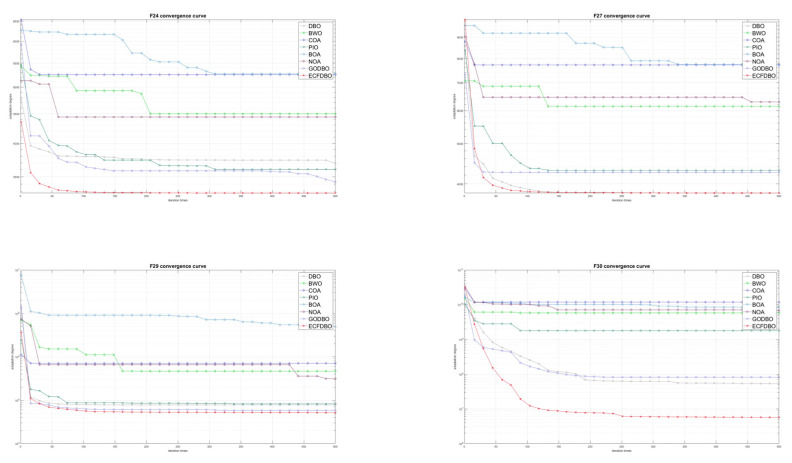

As shown in Table 2 and Figure A1, in the 30-dimensional CEC2017 benchmark, the ECFDBO algorithm achieved the best average performance on most of the test functions. Among the 29 test functions, ECFDBO achieved the best performance on 18 functions, while GODBO performed best on the remaining 11 functions. It is worth noting that, with the exception of GODBO, none of the other algorithms compared can outperform ECFDBO on any function; for example, on the typical complex benchmark function F1, the average value of ECFDBO is only 63,942.51, while the suboptimal algorithm DBO is as high as 2.64 × 108, and the rest of the algorithms are even in the order of 1010, which is an extremely wide gap, showing the significant advantage of ECFDBO in convergence precision. On simpler benchmarks such as the F5 function, although GODBO slightly outperforms ECFDBO (with means of 657.68 vs. 800.48), ECFDBO still significantly surpasses all other algorithms. In terms of standard deviation, ECFDBO achieved minimum values for 15 functions, followed by BWO with 7 functions. On the complex hybrid function F12, ECFDBO’s standard deviation is 1,863,468, which is 102 better than the second best algorithm, DBO with 1.19 × 108. On the F29 function, ECFDBO’s 271.7949 is only less than 50 different from the first place GODBO, and in the remaining optimal, median, and worst values, ECFDBO has 15, 19, and 17 optimal function values, respectively, all of which are ranked first among all algorithms. Overall, ECFDBO shows clear dominance on the 30-dimensional problem: six of the seven algorithms compared are outperformed by ECFDBO on almost all functions, and only GODBO is able to follow ECFDBO on some functions.

Table 2.

F1–F30 Benchmark Function Test Results (dim = 30).

| ECFDBO | BWO | COA | PIO | BOA | NOA | GODBO | DBO | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | mean | 63,942.51 | 5.3 × 1010 | 6.01 × 1010 | 2.39 × 1010 | 5.61 × 1010 | 6.94 × 1010 | 70,930,059 | 2.64 × 108 |

| std | 25,681.63 | 3.89 × 109 | 7.05 × 109 | 4 × 109 | 8.45 × 109 | 7.01 × 109 | 91,756,810 | 1.52 × 108 | |

| best | 26,987.47 | 4.5 × 1010 | 4.35 × 1010 | 1.71 × 1010 | 3.7 × 1010 | 5.09 × 1010 | 98,021.64 | 8,135,863 | |

| worst | 63,480.11 | 5.37 × 1010 | 6.04 × 1010 | 2.31 × 1010 | 5.63 × 1010 | 6.86 × 1010 | 49,093,779 | 2.57 × 108 | |

| median | 136,598.9 | 5.86 × 1010 | 7.33 × 1010 | 3.7 × 1010 | 7.02 × 1010 | 8.4 × 1010 | 4.57 × 108 | 5.65 × 108 | |

| F3 | mean | 9633.591 | 81,544.45 | 84,950.16 | 93,315.5 | 82,745.1 | 167,120.2 | 84,780.36 | 99,466.21 |

| std | 3718.314 | 6400.38 | 5554.423 | 11,092.81 | 7651.117 | 18,639.5 | 9399.648 | 44,057.83 | |

| best | 4364.107 | 65,363.83 | 68,694.54 | 65,001.02 | 64,619.64 | 128,257.5 | 61,888.87 | 48,642.91 | |

| worst | 9190.556 | 82,800.58 | 86,511.15 | 94,228.91 | 83,836.86 | 167,579.1 | 87,999.2 | 88,573.77 | |

| median | 20,079.23 | 89,699.18 | 92,190.43 | 140,987.2 | 94,910.4 | 201,649.3 | 98,912.04 | 276,108.9 | |

| F4 | mean | 507.3657 | 12,623.19 | 15,825.34 | 2722.201 | 20,935.8 | 18,256.86 | 580.2727 | 661.3345 |

| std | 36.80775 | 1638.889 | 2792.877 | 942.6409 | 3621.418 | 3024.038 | 78.66037 | 116.997 | |

| best | 413.7077 | 7410.967 | 7205.844 | 1384.752 | 13,918.25 | 11,069.96 | 473.5652 | 492.5788 | |

| worst | 499.465 | 12,837.3 | 16,777.87 | 2499.828 | 20,571.39 | 18,053.4 | 567.4128 | 640.5954 | |

| median | 593.5448 | 14,671.85 | 19,562.26 | 5098.445 | 26,488.42 | 23,726.71 | 842.6524 | 913.3457 | |

| F5 | mean | 800.4774 | 927.4693 | 913.1074 | 861.2371 | 912.0203 | 994.2789 | 657.6842 | 747.3314 |

| std | 66.09734 | 20.75242 | 30.04247 | 35.8504 | 26.87911 | 30.76318 | 51.81988 | 46.88862 | |

| best | 689.4502 | 866.6334 | 859.8462 | 815.4365 | 861.6815 | 891.0154 | 582.831 | 670.1164 | |

| worst | 787.3878 | 928.829 | 913.4338 | 856.991 | 912.5462 | 1002.681 | 644.9905 | 749.2904 | |

| median | 941.7984 | 959.2968 | 979.8217 | 937.9318 | 957.8257 | 1033.27 | 796.3756 | 823.7392 | |

| F6 | mean | 656.6684 | 692.5882 | 692.5231 | 664.002 | 689.7923 | 700.5578 | 632.6684 | 651.2531 |

| std | 10.41309 | 3.796584 | 6.053389 | 9.607602 | 6.46441 | 6.283517 | 7.125919 | 14.1612 | |

| best | 638.408 | 683.9351 | 680.0325 | 647.6615 | 672.0864 | 687.1371 | 620.9715 | 625.9021 | |

| worst | 656.0106 | 692.5493 | 692.5136 | 662.3847 | 690.1579 | 700.4147 | 630.7543 | 651.611 | |

| median | 682.1257 | 700.5901 | 706.2709 | 684.4867 | 698.8628 | 709.9328 | 649.3964 | 689.0801 | |

| F7 | mean | 1153.35 | 1399.737 | 1426.264 | 1480.295 | 1399.608 | 2509.026 | 956.4392 | 1033.291 |

| std | 95.01219 | 31.46096 | 56.81814 | 69.98394 | 39.21844 | 146.9285 | 59.31968 | 96.73882 | |

| best | 984.1991 | 1324.88 | 1192.911 | 1319.496 | 1303.075 | 2124.928 | 854.8254 | 861.6912 | |

| worst | 1155.905 | 1405.592 | 1431.847 | 1488.556 | 1397.56 | 2510.022 | 949.4535 | 1023.429 | |

| median | 1363.504 | 1455.351 | 1492.507 | 1591.572 | 1475.421 | 2819.798 | 1099.998 | 1237.708 | |

| F8 | mean | 1025.492 | 1150.519 | 1144.503 | 1150.445 | 1140.776 | 1240.074 | 956.0772 | 1023.584 |

| std | 55.48367 | 17.49316 | 26.30245 | 31.96821 | 22.10053 | 31.092 | 59.19539 | 53.63345 | |

| best | 932.3506 | 1115.986 | 1067.319 | 1051.653 | 1078.164 | 1152.245 | 876.1469 | 933.177 | |

| worst | 1017.925 | 1151.833 | 1147.954 | 1147.037 | 1146.534 | 1241.165 | 938.4419 | 1024.154 | |

| median | 1136.266 | 1196.125 | 1181.328 | 1205.558 | 1168.874 | 1295.581 | 1083.507 | 1126.276 | |

| F9 | mean | 9736.612 | 11,225.61 | 11,006.85 | 11,206.31 | 11,285.16 | 19,537.19 | 3953.867 | 6765.347 |

| std | 2383.204 | 1012.324 | 1454.668 | 2377.326 | 1176.202 | 2469.75 | 1464.371 | 1543.686 | |

| best | 5041.098 | 8552.426 | 8263.224 | 7715.942 | 8045.321 | 13,774.64 | 1759.752 | 4228.991 | |

| worst | 9855.975 | 11,336.28 | 11,214.13 | 10,825.41 | 11,383.51 | 19,132.04 | 3849.641 | 6651.009 | |

| median | 15,743.02 | 13,329.95 | 13,500.85 | 18,884.46 | 13,336.9 | 23,146.73 | 7918.796 | 9490.701 | |

| F10 | mean | 5713.745 | 8901.387 | 8736.062 | 8948.604 | 9224.094 | 9078.285 | 6807.646 | 6231.936 |

| std | 664.7464 | 357.743 | 476.0732 | 447.7387 | 346.0579 | 310.5175 | 1617.939 | 944.1829 | |

| best | 4282.283 | 8159.714 | 7632.897 | 7856.555 | 8399.939 | 7874.633 | 3640.744 | 4264.357 | |

| worst | 5621.71 | 8961.451 | 8780.951 | 8953.611 | 9296.556 | 9103.181 | 6538.687 | 5975.079 | |

| median | 7289.91 | 9538.599 | 9513.005 | 9625.635 | 9659.249 | 9465.218 | 9083.362 | 8844.381 | |

| F11 | mean | 1292.336 | 8200.144 | 9024.436 | 4832.391 | 9120.109 | 12,833.55 | 1401.827 | 1742.403 |

| std | 69.0754 | 1516.37 | 1678.05 | 1121.911 | 2668.268 | 2871 | 142.0839 | 575.7978 | |

| best | 1164.307 | 4821.051 | 6320.424 | 2628.512 | 5682.718 | 5379.799 | 1234.603 | 1346.82 | |

| worst | 1285.529 | 8306.735 | 8685.513 | 4614.778 | 8221.468 | 13,228.65 | 1375.095 | 1613.581 | |

| median | 1441.465 | 11,521.07 | 12,781.11 | 7008.444 | 16,082.06 | 17,555.23 | 1911.36 | 4505.651 | |

| F12 | mean | 2,519,837 | 1.16 × 1010 | 1.3 × 1010 | 2.05 × 109 | 1.33 × 1010 | 1 × 1010 | 1.05 × 108 | 75,765,766 |

| std | 1,863,468 | 2.18 × 109 | 3.2 × 109 | 6.39 × 108 | 3.25 × 109 | 2.26 × 109 | 2.56 × 108 | 1.19 × 108 | |

| best | 192,565.7 | 8.3 × 109 | 7.21 × 109 | 8.47 × 108 | 6.78 × 109 | 5.96 × 109 | 2,916,036 | 2,025,324 | |

| worst | 2,047,460 | 1.17 × 1010 | 1.28 × 1010 | 2.04 × 109 | 1.31 × 1010 | 1.01 × 1010 | 20,653,606 | 27,026,788 | |

| median | 8,109,615 | 1.6 × 1010 | 1.96 × 1010 | 4.15 × 109 | 2.14 × 1010 | 1.41 × 1010 | 1.09 × 109 | 6.04 × 108 | |

| F13 | mean | 25,844.73 | 6.55 × 109 | 8.69 × 109 | 6.77 × 108 | 1.3 × 1010 | 5.64 × 109 | 1.15 × 108 | 11,920,817 |

| std | 20,870.87 | 2.1 × 109 | 4.36 × 109 | 2.49 × 108 | 6.3 × 109 | 1.5 × 109 | 6.03 × 108 | 20,468,936 | |

| best | 3899.699 | 2.83 × 109 | 2.84 × 109 | 1.85 × 108 | 3.88 × 109 | 2.1 × 109 | 41,537.44 | 46,900.35 | |

| worst | 18,980.97 | 6.51 × 109 | 7.8 × 109 | 6.19 × 108 | 1.22 × 1010 | 5.79 × 109 | 224,277.8 | 1,574,382 | |

| median | 72,569.17 | 1.05 × 1010 | 2.02 × 1010 | 1.22 × 109 | 2.83 × 1010 | 9.46 × 109 | 3.31 × 109 | 71,958,593 | |

| F14 | mean | 32,334.97 | 4,257,854 | 3,960,435 | 815,745.2 | 4,297,723 | 3,025,255 | 283,592.4 | 209,998.4 |

| std | 26,512.96 | 2,620,007 | 3,167,737 | 583,094.9 | 4,097,839 | 1,467,041 | 382,286.9 | 185,649 | |

| best | 2309.498 | 592,077.2 | 557,713 | 90,371.21 | 144,606.2 | 667,300.7 | 10,666.78 | 10,345.24 | |

| worst | 25,730.5 | 3,906,692 | 3,948,395 | 681,304.7 | 2,568,498 | 2,860,144 | 136,500.5 | 166,456.7 | |

| median | 89,428.44 | 14,500,690 | 14,945,409 | 2,395,542 | 19,757,277 | 7,075,432 | 1,673,009 | 881,024.9 | |

| F15 | mean | 13,198.82 | 3.28 × 108 | 8.58 × 108 | 1.52 × 108 | 5.68 × 108 | 8.21 × 108 | 65,525.93 | 285,280.7 |

| std | 12,461.62 | 1.9 × 108 | 5.73 × 108 | 91,543,844 | 5.76 × 108 | 4.38 × 108 | 53,997.25 | 1,102,114 | |

| best | 1908.749 | 13,466,524 | 45,179,493 | 34,061,391 | 37,393,246 | 1.09 × 108 | 2920.75 | 7399.019 | |

| worst | 9093.7 | 3.34 × 108 | 7.62 × 108 | 1.13 × 108 | 3.63 × 108 | 8.15 × 108 | 58,370.11 | 59,707.92 | |

| median | 43,755.35 | 8.69 × 108 | 2.91 × 109 | 4.03 × 108 | 2.37 × 109 | 1.71 × 109 | 177,445.2 | 6,109,350 | |

| F16 | mean | 2879.769 | 5819.178 | 6364.759 | 4098.702 | 7467.678 | 5202.702 | 3115.283 | 3288.972 |

| std | 344.4561 | 410.5533 | 906.3894 | 348.0564 | 1430.561 | 352.1852 | 420.6608 | 435.3645 | |

| best | 2175.863 | 4673.785 | 5161.759 | 3114.32 | 4054.969 | 4353.857 | 2333.674 | 2172.459 | |

| worst | 2899.125 | 5900.782 | 6260.549 | 4115.118 | 7507.335 | 5263.261 | 3055.136 | 3317.381 | |

| median | 3567.785 | 6616.584 | 8789.34 | 4960.323 | 9887.666 | 5749.903 | 4083.444 | 4184.224 | |

| F17 | mean | 2516.491 | 4475.714 | 5249.251 | 2971.063 | 10974.59 | 3581.037 | 2582.441 | 2679.382 |

| std | 262.9417 | 763.2336 | 3076.794 | 154.6144 | 11,398.86 | 228.1887 | 289.5168 | 272.8822 | |

| best | 2054.322 | 3156.685 | 3006.496 | 2702.383 | 3899.054 | 3086.8 | 1904.785 | 2203.731 | |

| worst | 2571.811 | 4347.132 | 3900.741 | 2999.47 | 7324.974 | 3562.245 | 2597.015 | 2706.697 | |

| median | 3159.862 | 6487.527 | 17,638.14 | 3241.072 | 59,337.9 | 4019.663 | 3276.592 | 3195.838 | |

| F18 | mean | 715,402.3 | 54,249,832 | 59,452,992 | 11,870,742 | 49,325,991 | 40,892,718 | 1,948,317 | 4,033,524 |

| std | 817,243.3 | 27,073,426 | 53,818,539 | 7,421,462 | 44,586,033 | 19,512,922 | 3,992,745 | 5,215,681 | |

| best | 41,453.47 | 6,640,996 | 1,889,149 | 2,794,686 | 6,903,898 | 5,674,777 | 35,531.39 | 78,313.29 | |

| worst | 486,623.9 | 53,683,497 | 49,593,129 | 10,764,934 | 31,256,161 | 39,061,988 | 860,592.8 | 1,839,512 | |

| median | 3,439,557 | 1.12 × 108 | 2.11 × 108 | 30,407,745 | 1.86 × 108 | 1.06 × 108 | 20,309,921 | 23,672,496 | |

| F19 | mean | 21,262.95 | 4.85 × 108 | 7.77 × 108 | 2 × 108 | 6.64 × 108 | 1.17 × 109 | 4,097,332 | 5,784,654 |

| std | 18,941.24 | 2.03 × 108 | 5.22 × 108 | 96,177,925 | 4.79 × 108 | 4.63 × 108 | 11,501,863 | 18,081,030 | |

| best | 2583.758 | 92,132,654 | 59,577,484 | 40,201,933 | 89,876,191 | 2.88 × 108 | 2193.569 | 2638.476 | |

| worst | 16,050.65 | 4.87 × 108 | 7.96 × 108 | 2.14 × 108 | 6.08 × 108 | 1.22 × 109 | 116,303.4 | 404,450.8 | |

| median | 56,775.43 | 9.58 × 108 | 2.71 × 109 | 4.2 × 108 | 2.24 × 109 | 1.97 × 109 | 50,617,202 | 98,073,607 | |

| F20 | mean | 2656.364 | 3033.38 | 3094.954 | 3036.89 | 3118.8 | 3100.258 | 2697.781 | 2742.864 |

| std | 239.1146 | 130.2307 | 168.8114 | 119.101 | 92.77931 | 110.8192 | 226.7765 | 260.9707 | |

| best | 2272.189 | 2771.009 | 2554.983 | 2787.174 | 2897.134 | 2857.476 | 2300.289 | 2235.967 | |

| worst | 2647.291 | 3043.592 | 3139.187 | 3045.243 | 3119.75 | 3110.219 | 2628.047 | 2707.018 | |

| median | 3128.032 | 3296.213 | 3339.509 | 3352.285 | 3288.163 | 3338.99 | 3137.841 | 3249.261 | |

| F21 | mean | 2580.126 | 2723.701 | 2747.425 | 2615.562 | 2751.371 | 2754.239 | 2465.95 | 2561.324 |

| std | 73.88951 | 48.44362 | 45.47191 | 27.57139 | 48.36754 | 23.98249 | 45.84667 | 48.4529 | |

| best | 2447.708 | 2517.947 | 2648.155 | 2564.386 | 2623.924 | 2706.618 | 2377.878 | 2471.764 | |

| worst | 2572.032 | 2732.73 | 2752.298 | 2617.724 | 2755.723 | 2760.237 | 2468.811 | 2558.892 | |

| median | 2731.755 | 2792.62 | 2855.607 | 2663.135 | 2825.202 | 2790.236 | 2560.656 | 2655.951 | |

| F22 | mean | 6787.768 | 8871.049 | 9576.702 | 5759.646 | 7151.263 | 9518.539 | 4205.682 | 6215.286 |

| std | 1677.095 | 484.1969 | 764.6035 | 2399.439 | 1026.057 | 723.9233 | 2613.766 | 2311.638 | |

| best | 2303.192 | 7887.258 | 6769.96 | 3515.935 | 4850.228 | 7868.123 | 2311.7 | 2364.278 | |

| worst | 7116.831 | 8882.628 | 9874.276 | 4697.181 | 7126.808 | 9654.074 | 2427.148 | 7212.762 | |

| median | 8901.377 | 9708.593 | 10,688.6 | 10,792.8 | 9364.771 | 10,622.98 | 9568.586 | 9886.574 | |

| F23 | mean | 3014.155 | 3333.174 | 3651.941 | 2990.432 | 3575.073 | 3402.129 | 2915.651 | 3014.023 |

| std | 97.72177 | 50.0228 | 148.0593 | 29.88314 | 187.2047 | 60.65244 | 112.0721 | 86.11765 | |

| best | 2787.788 | 3226.259 | 3351.357 | 2935.955 | 3025.996 | 3276.915 | 2762.188 | 2864.823 | |

| worst | 2996.712 | 3337.957 | 3632.102 | 2989.931 | 3596.07 | 3403.872 | 2871.606 | 3007.588 | |

| median | 3250.481 | 3430.545 | 3998.319 | 3056.997 | 3864.495 | 3505.623 | 3139.631 | 3177.673 | |

| F24 | mean | 3161.378 | 3613.339 | 3787.649 | 3158.17 | 4161.534 | 3645.135 | 3113.082 | 3182.059 |

| std | 102.5177 | 79.48947 | 185.5656 | 42.43335 | 238.4944 | 75.61685 | 90.56529 | 75.59769 | |

| best | 2965.589 | 3496.282 | 3365.74 | 3082.772 | 3590.092 | 3434.83 | 2979.835 | 3044.666 | |

| worst | 3173.165 | 3596.364 | 3808.872 | 3159.029 | 4152.174 | 3653.606 | 3097.128 | 3162.987 | |

| median | 3327.024 | 3762.824 | 4200.671 | 3240.074 | 4590.274 | 3824.527 | 3310.4 | 3336.49 | |

| F25 | mean | 2896.548 | 4480.734 | 5323.274 | 4724.265 | 5704.686 | 8804.558 | 2923.458 | 2999.593 |

| std | 15.91772 | 199.7949 | 350.8185 | 380.5895 | 641.2731 | 863.4685 | 30.39884 | 77.06749 | |

| best | 2883.728 | 3962.203 | 4410.293 | 4017.356 | 4641.95 | 7384.903 | 2885.076 | 2894.905 | |

| worst | 2889.672 | 4477.085 | 5326.115 | 4702.903 | 5546.177 | 8584.713 | 2924.395 | 2983.4 | |

| median | 2950.292 | 4847.75 | 5965.091 | 5495.495 | 7193.241 | 10803.07 | 3023.588 | 3210.79 | |

| F26 | mean | 7455.369 | 10,646.15 | 11,735.05 | 6895.655 | 11,882.12 | 11,251.12 | 6034.232 | 7158.672 |

| std | 1340.177 | 561.0557 | 861.7151 | 959.6498 | 788.1217 | 822.3199 | 997.3035 | 785.1776 | |

| best | 2816.789 | 9133.756 | 9854.465 | 5176.728 | 10,765.61 | 9540.23 | 3676.833 | 5295.298 | |

| worst | 7586.724 | 10,689.68 | 11,804.83 | 7168.295 | 11,911.44 | 11,502.11 | 5888.133 | 7151.111 | |

| median | 9757.087 | 11,751.22 | 13,408.35 | 8646.077 | 13,352.94 | 12,632.54 | 8731.387 | 8632.776 | |

| F27 | mean | 3290.302 | 4034.996 | 4495.708 | 3404.736 | 4395.659 | 4132.721 | 3349.182 | 3347.978 |

| std | 45.08133 | 151.9417 | 395.5547 | 55.45793 | 363.7561 | 122.9201 | 79.86542 | 70.67476 | |

| best | 3213.545 | 3652.449 | 3830.985 | 3293.771 | 3752.556 | 3903.359 | 3261.087 | 3249.935 | |

| worst | 3272.556 | 4059.076 | 4402.444 | 3403.038 | 4458.546 | 4138.376 | 3323.077 | 3336.538 | |

| median | 3392.306 | 4294.696 | 5635.099 | 3520.293 | 5352.941 | 4402.514 | 3634.885 | 3534.849 | |

| F28 | mean | 3252.387 | 6458.329 | 7659.126 | 4566.759 | 8163.217 | 7789.137 | 3352.866 | 3604.37 |

| std | 42.03031 | 325.0748 | 701.5746 | 459.2043 | 500.8554 | 776.3482 | 75.75684 | 687.9095 | |

| best | 3200.329 | 5574.211 | 6126.061 | 4073.511 | 7047.834 | 6335.197 | 3265.205 | 3299.473 | |

| worst | 3250.148 | 6521.058 | 7650.086 | 4413.026 | 8244.752 | 7842.011 | 3324.336 | 3392.65 | |

| median | 3373.517 | 7105.451 | 8955.831 | 5831.231 | 9021.743 | 9020.772 | 3558.877 | 6272.067 | |

| F29 | mean | 4429.617 | 6895.76 | 8345.137 | 5101.263 | 13,156.87 | 6395.72 | 4214.615 | 4549.805 |

| std | 271.7949 | 711.9064 | 1580.409 | 304.2742 | 6171.057 | 428.0731 | 229.5287 | 392.7875 | |

| best | 3947.653 | 5733.582 | 5557.795 | 4427.106 | 6837.421 | 5507.769 | 3817.121 | 3800.398 | |

| worst | 4455.078 | 6874.303 | 8501.48 | 5147.45 | 11,409.63 | 6436.563 | 4261.45 | 4548.292 | |

| median | 4972.681 | 8645.288 | 12397.94 | 5690.939 | 34917.82 | 7228.335 | 4635.857 | 5311.23 | |

| F30 | mean | 48,500.77 | 1.16 × 109 | 1.78 × 109 | 1.23 × 108 | 1.22 × 109 | 6.8 × 108 | 1,780,797 | 7,762,810 |

| std | 41,110.94 | 3.57 × 108 | 1.19 × 109 | 50,993,436 | 5.91 × 108 | 2.22 × 108 | 2,843,252 | 22,587,572 | |

| best | 6351.341 | 5.08 × 108 | 1.04 × 108 | 35,740,734 | 3.27 × 108 | 2.09 × 108 | 30,084.02 | 13,525.09 | |

| worst | 31,118.47 | 1.15 × 109 | 1.35 × 109 | 1.15 × 108 | 1.1 × 109 | 6.98 × 108 | 570,931.4 | 1,081,845 | |

| median | 151,815.9 | 1.96 × 109 | 5.45 × 109 | 2.4 × 108 | 2.48 × 109 | 1.1 × 109 | 10,298,184 | 1.23 × 108 |

As shown in Table 3 and Figure A2, the overall dominance of ECFDBO is further extended in the 50-dimensional benchmark test. The result statistics for the 29 tested functions show that ECFDBO achieves the best average performance value on 19 functions, while the remaining 10 functions are still dominated by GODBO. None of the other algorithms outperform ECFDBO on any function, reflecting the fact that ECFDBO remains a solid leader in higher dimensions. For example, on the F9 function, ECFDBO has a mean of 2.63 × 104, while the second-best GODBO is about 1.87 × 104 higher, and the remaining algorithms’ values are generally more than an order of magnitude higher. This indicates that as the dimensionality increases, some algorithms such as BWO and COA show deterioration in performance, with their average errors and rankings significantly lagging behind those of ECFDBO; in contrast, ECFDBO and GODBO are still able to maintain good adaptation to complex functions. In terms of standard deviation, ECFDBO achieves the lowest fluctuation on 14 functions, and the second-best BWO is the most stable on 5 functions; in the complex single-peak function F1, the standard deviation of ECFDBO is about 2.36 × 106, while the value of GODBO is more than 7.03 × 108, with a magnitude difference of more than 102. In the rest of the best, median, and worst values, ECFDBO also achieves the first place with 18, 17, and 18, while GODBO is in the second place with 10, 9, and 10. In the high-dimensional environment of 50 dimensions, the ECFDBO algorithm still shows the overall leading performance advantage. Its average convergence precision continues to be the best and is slightly better than the performance in 30 dimensions. In the extreme cases of optimal/worst, ECFDBO wins with the majority function, showing good robustness.

Table 3.

F1–F30 Benchmark Function Test Results (dim = 50).

| ECFDBO | BWO | COA | PIO | BOA | NOA | GODBO | DBO | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | mean | 4,780,258 | 1.06 × 1011 | 1.09 × 1011 | 9.65 × 1010 | 1.09 × 1011 | 1.71 × 1011 | 1.18 × 109 | 9.19 × 109 |

| std | 2,359,295 | 5.01 × 109 | 9.86 × 109 | 1.39 × 1010 | 7.88 × 109 | 1.07 × 1010 | 7.03 × 108 | 1.69 × 1010 | |

| best | 1,512,934 | 9.37 × 1010 | 8.91 × 1010 | 6.82 × 1010 | 9.01 × 1010 | 1.5 × 1011 | 4.25 × 108 | 4.64 × 108 | |

| worst | 3,928,363 | 1.06 × 1011 | 1.1 × 1011 | 9.83 × 1010 | 1.1 × 1011 | 1.73 × 1011 | 1 × 109 | 3.77 × 109 | |

| median | 10,522,602 | 1.15 × 1011 | 1.25 × 1011 | 1.22 × 1011 | 1.22 × 1011 | 1.94 × 1011 | 3.35 × 109 | 7.07 × 1010 | |

| F3 | mean | 87,516.16 | 249,766.4 | 197,257.9 | 264,701.7 | 316,388.5 | 329,198.4 | 322,936.4 | 248,865.5 |

| std | 32,122.38 | 36,977.68 | 21,021.17 | 29,715.68 | 149,694.8 | 33,740.95 | 58,986.33 | 54,829.01 | |

| best | 36,759.7 | 189,932.7 | 162,315.7 | 179,046.2 | 170,203 | 248,425.4 | 193,637.4 | 145,758.5 | |

| worst | 73,523.75 | 251,556.4 | 195,704.8 | 266,654.4 | 272,373.2 | 331,103.4 | 314,708 | 247,962.2 | |

| median | 162,429.7 | 351,854.8 | 238,114.7 | 311,972.1 | 865,964.3 | 382,355.9 | 513,354.7 | 393,175.2 | |

| F4 | mean | 609.8426 | 34,119.13 | 39,293.57 | 15,732.3 | 41,410.92 | 51,193.12 | 912.5862 | 1194.075 |

| std | 60.86762 | 3216.901 | 5100.663 | 5187.062 | 3473.452 | 8197.951 | 159.1647 | 299.3094 | |

| best | 489.1183 | 22,722.15 | 30,096.17 | 7784.69 | 31,673.1 | 37,072.26 | 654.7685 | 663.9026 | |

| worst | 617.0304 | 34,459.92 | 39,746.09 | 14,700.99 | 40,911.51 | 53,136.07 | 878.393 | 1115.647 | |

| median | 800.1924 | 39,085.95 | 48,427.4 | 31,976.03 | 49,882.52 | 63,973.42 | 1351.225 | 1895.822 | |

| F5 | mean | 1023.086 | 1196.792 | 1194.138 | 1243.679 | 1176.389 | 1447.111 | 831.1338 | 995.0373 |

| std | 111.8223 | 18.2011 | 32.05341 | 28.3418 | 26.20114 | 33.46087 | 81.35437 | 99.21457 | |

| best | 837.5148 | 1151.511 | 1134.758 | 1167.687 | 1104.998 | 1368.81 | 700.8344 | 821.8647 | |

| worst | 1044.548 | 1198.489 | 1197.412 | 1241.588 | 1184.553 | 1455.214 | 817.1006 | 1005.631 | |

| median | 1273.856 | 1221.935 | 1243.223 | 1313.445 | 1218.404 | 1507.044 | 1044.84 | 1153.54 | |

| F6 | mean | 673.1587 | 703.0555 | 702.3727 | 691.9153 | 705.7748 | 720.2816 | 647.1692 | 670.9763 |

| std | 6.741626 | 4.470917 | 4.770088 | 9.732927 | 5.495881 | 4.579695 | 7.042482 | 9.649086 | |

| best | 659.9427 | 689.8744 | 687.6308 | 673.5214 | 686.885 | 708.4121 | 634.3791 | 643.4003 | |

| worst | 673.5805 | 703.072 | 704.0603 | 693.1564 | 705.456 | 720.9183 | 647.4455 | 670.9801 | |

| median | 688.3811 | 710.4015 | 707.9847 | 711.0534 | 715.5399 | 727.7279 | 663.3866 | 687.7654 | |

| F7 | mean | 1677.512 | 1989.602 | 2070.307 | 2113.629 | 2008.223 | 4750.685 | 1335.724 | 1401.825 |

| std | 129.802 | 43.66188 | 41.57328 | 77.63079 | 52.39592 | 171.1507 | 181.3475 | 134.9587 | |

| best | 1415.056 | 1864.435 | 1960.993 | 1884.382 | 1841.49 | 4404.823 | 1075.477 | 1139.746 | |

| worst | 1692.121 | 1994.192 | 2074.903 | 2120.844 | 2001.787 | 4751.85 | 1307.007 | 1407.649 | |

| median | 1973.952 | 2069.746 | 2130.137 | 2199.236 | 2110.807 | 5066.757 | 1893.642 | 1700.882 | |

| F8 | mean | 1351.27 | 1512.373 | 1495.853 | 1563.182 | 1512.089 | 1749.039 | 1169.113 | 1279.896 |

| std | 85.06685 | 17.77129 | 27.11427 | 36.59189 | 24.964 | 42.2352 | 124.1553 | 117.3652 | |

| best | 1132.023 | 1467.454 | 1448.889 | 1487.389 | 1436.219 | 1623.599 | 1024.438 | 1068.045 | |

| worst | 1332.628 | 1511.177 | 1496.799 | 1568.833 | 1512.149 | 1756.379 | 1111.142 | 1312.018 | |

| median | 1524.114 | 1545.217 | 1545.219 | 1624.462 | 1555.27 | 1810.891 | 1443.049 | 1485.358 | |

| F9 | mean | 26,315.19 | 39,713.01 | 39,487.92 | 43,652.74 | 40,148.12 | 64,453.51 | 18,684.12 | 27,981.46 |

| std | 5710.865 | 2801.281 | 2733.521 | 6709.924 | 3165.292 | 6313.14 | 5930.056 | 7751.885 | |

| best | 14,120 | 30,240.19 | 34,025.13 | 29,168.84 | 30,667.48 | 44,678.95 | 10,217.21 | 14,544.16 | |

| worst | 26,145.71 | 40,060.17 | 39,455.94 | 43,719.75 | 40,167.54 | 65,672.73 | 18,116.57 | 27,353.29 | |

| median | 39,054.82 | 44,701.06 | 44,175.14 | 54,292.88 | 45,526.84 | 76,863.93 | 33,371.21 | 43,059.4 | |

| F10 | mean | 9036.244 | 15,023.68 | 15,408.3 | 15,529.49 | 15,601.81 | 15,607.16 | 12,851.33 | 11,442.55 |

| std | 1028.188 | 463.9161 | 452.2438 | 447.2961 | 565.7118 | 364.0358 | 2916.489 | 2387.653 | |

| best | 6960.834 | 13,673.81 | 14,072.49 | 14,574.59 | 14,099.78 | 14,972.36 | 7474.548 | 8069.785 | |

| worst | 9123.119 | 15,059.99 | 15,410.71 | 15,589.28 | 15,670.62 | 15,660.5 | 14,533.69 | 11,116.4 | |

| median | 10,696.68 | 15,644.29 | 16,156.46 | 16,218.35 | 16,541.27 | 16,122.54 | 15,705.3 | 15,258.18 | |

| F11 | mean | 1456.014 | 22,646.18 | 25,955.2 | 16,038.51 | 24,384.56 | 37,752.18 | 3113.923 | 5406.151 |

| std | 101.1321 | 1911.871 | 2606.749 | 4284.927 | 2959.744 | 6875.879 | 685.7545 | 4643.407 | |

| best | 1307.773 | 18,668.89 | 19,768.28 | 9414.711 | 15,229.5 | 19,129.47 | 1899.894 | 2176.385 | |

| worst | 1438.399 | 22,946.78 | 26,342.5 | 15,599.38 | 25,237.19 | 38,325.34 | 3226.607 | 3474.322 | |

| median | 1667.795 | 25,295.74 | 30,296.26 | 26,549.58 | 28,484.62 | 49,140.39 | 4584.315 | 19,830.63 | |

| F12 | mean | 21,208,223 | 6.3 × 1010 | 8.9 × 1010 | 1.41 × 1010 | 8.17 × 1010 | 6.76 × 1010 | 3.98 × 108 | 9.58 × 108 |

| std | 11,394,622 | 1.05 × 1010 | 1.46 × 1010 | 2.63 × 109 | 1.76 × 1010 | 9.25 × 109 | 4.05 × 108 | 8.38 × 108 | |

| best | 7,817,785 | 3.66 × 1010 | 5.51 × 1010 | 8.37 × 109 | 5.32 × 1010 | 4.61 × 1010 | 31,344,196 | 31,725,817 | |

| worst | 19,125,871 | 6.25 × 1010 | 9.14 × 1010 | 1.39 × 1010 | 8.61 × 1010 | 6.79 × 1010 | 2.88 × 108 | 6.88 × 108 | |

| median | 48,400,214 | 8.33 × 1010 | 1.13 × 1011 | 2.09 × 1010 | 1.13 × 1011 | 8.4 × 1010 | 1.75 × 109 | 3.61 × 109 | |

| F13 | mean | 65,586.63 | 4.12 × 1010 | 4.74 × 1010 | 4.37 × 109 | 4.13 × 1010 | 2.85 × 1010 | 1.93 × 108 | 1.61 × 108 |

| std | 44,267.62 | 8.42 × 109 | 1.62 × 1010 | 1.31 × 109 | 1.72 × 1010 | 4.54 × 109 | 5.22 × 108 | 2.28 × 108 | |

| best | 13,035.42 | 2.71 × 1010 | 1.55 × 1010 | 1.89 × 109 | 1.66 × 1010 | 1.92 × 1010 | 114,020.3 | 2,961,075 | |

| worst | 51,812.64 | 4.15 × 1010 | 4.68 × 1010 | 4.28 × 109 | 3.65 × 1010 | 2.87 × 1010 | 22,893,078 | 65,134,665 | |

| median | 144,709.6 | 5.91 × 1010 | 8.47 × 1010 | 6.93 × 109 | 7.87 × 1010 | 3.76 × 1010 | 2.57 × 109 | 9.92 × 108 | |

| F14 | mean | 327,094.4 | 70,972,878 | 1.21 × 108 | 4,716,715 | 1.57 × 108 | 31,301,009 | 3,210,835 | 4,034,978 |

| std | 206,097.4 | 26,730,785 | 1.07 × 108 | 2,287,260 | 1.16 × 108 | 16,751,125 | 4,229,751 | 4,957,667 | |

| best | 62,115.75 | 10,693,642 | 5,875,508 | 1,233,774 | 16,131,250 | 9,128,897 | 304,722.2 | 148,710.7 | |

| worst | 311,704.9 | 71,552,201 | 79,985,985 | 4,621,592 | 1.2 × 108 | 27,603,229 | 1,954,626 | 1,928,327 | |

| median | 859,561.4 | 1.44 × 108 | 4.11 × 108 | 12,215,340 | 4.41 × 108 | 85,198,632 | 23,139,889 | 17,643,989 | |

| F15 | mean | 20,076.14 | 6.39 × 109 | 8.42 × 109 | 1.85 × 109 | 9.56 × 109 | 7.81 × 109 | 1,194,628 | 99,311,999 |

| std | 12,505.08 | 1.61 × 109 | 3.71 × 109 | 7.37 × 108 | 2.88 × 109 | 2.2 × 109 | 4,993,285 | 3.24 × 108 | |

| best | 3435.915 | 3.34 × 109 | 2.86 × 109 | 3.12 × 108 | 3.54 × 109 | 2.44 × 109 | 16,137.75 | 38,951.08 | |

| worst | 19,200.35 | 6.16 × 109 | 8.49 × 109 | 1.85 × 109 | 9.96 × 109 | 8.04 × 109 | 95,439.28 | 222,537.5 | |

| median | 55,648.57 | 9.84 × 109 | 2.03 × 1010 | 3.18 × 109 | 1.53 × 1010 | 1.1 × 1010 | 27,128,857 | 1.76 × 109 | |

| F16 | mean | 4149.21 | 8913.883 | 10,551.97 | 6367.51 | 11,540.07 | 8841.368 | 4350.922 | 4647.712 |

| std | 449.7375 | 713.0557 | 1734.323 | 517.7536 | 1392.449 | 475.2364 | 620.8001 | 733.0185 | |

| best | 2885.242 | 7250.674 | 7519.845 | 5428.665 | 8080.71 | 7966.537 | 3034.95 | 3140.566 | |

| worst | 4161.454 | 8945.439 | 10,219.52 | 6349.436 | 11,493.53 | 8814.252 | 4308.845 | 4797.013 | |

| median | 4885.024 | 10,160.04 | 14,156.68 | 7510.284 | 14,834.54 | 9721.609 | 5773.102 | 6039.062 | |

| F17 | mean | 3925.459 | 7852.056 | 12,419.1 | 5903.533 | 17,758.61 | 16,857.18 | 3714.467 | 4287.897 |

| std | 400.7181 | 1469.263 | 9511.617 | 524.5195 | 11,094.1 | 7660.292 | 376.9633 | 575.6267 | |

| best | 3266.528 | 5184.302 | 4962.228 | 4893.874 | 6891.405 | 6954.543 | 2801.898 | 2809.991 | |

| worst | 3885.232 | 7429.907 | 10,080.37 | 5944.598 | 15,095.38 | 17,259.1 | 3752.541 | 4376.222 | |

| median | 4527.253 | 11,919.57 | 54,864.4 | 7012.83 | 47,128.53 | 43,756.89 | 4383.183 | 5328.389 | |

| F18 | mean | 3,741,347 | 1.58 × 108 | 2.06 × 108 | 56,514,657 | 1.8 × 108 | 1.7 × 108 | 8,681,295 | 10,596,914 |

| std | 2,325,907 | 63,623,326 | 1.04 × 108 | 25,410,815 | 92,081,400 | 53,349,251 | 9,155,939 | 9,242,248 | |

| best | 723,232.6 | 52,320,253 | 77,846,397 | 19,530,349 | 57,970,648 | 75,065,695 | 724,814.8 | 1,571,896 | |

| worst | 3,132,272 | 1.59 × 108 | 1.82 × 108 | 51,753,001 | 1.41 × 108 | 1.72 × 108 | 5,021,894 | 7,209,046 | |

| median | 10,168,401 | 3.36 × 108 | 5.33 × 108 | 1.11 × 108 | 4.29 × 108 | 2.91 × 108 | 42,010,779 | 39,489,195 | |

| F19 | mean | 22,177.84 | 3.65 × 109 | 4.7 × 109 | 6.87 × 108 | 4.44 × 109 | 3.52 × 109 | 3,340,464 | 8,448,320 |

| std | 15,848.02 | 8.07 × 108 | 1.74 × 109 | 2.54 × 108 | 1.8 × 109 | 7.66 × 108 | 5,014,682 | 10,142,526 | |

| best | 2419.492 | 1.99 × 109 | 1 × 109 | 2.68 × 108 | 1.72 × 109 | 1.14 × 109 | 12,709.89 | 258,850.9 | |

| worst | 23,607.7 | 3.62 × 109 | 4.73 × 109 | 6.82 × 108 | 3.92 × 109 | 3.53 × 109 | 1,037,733 | 4,918,391 | |

| median | 44,662.61 | 5.31 × 109 | 7.28 × 109 | 1.18 × 109 | 8.35 × 109 | 4.8 × 109 | 19,438,061 | 39,488,873 | |

| F20 | mean | 3644.941 | 4157.516 | 4297.97 | 4367.142 | 4365.791 | 4512.71 | 3788.856 | 3724.264 |

| std | 405.6563 | 182.891 | 195.1588 | 236.7496 | 218.3726 | 156.6324 | 432.4924 | 269.4832 | |

| best | 2731.173 | 3642.467 | 3861.911 | 3678.193 | 3747.012 | 4093.051 | 2791.965 | 3237.719 | |

| worst | 3730.817 | 4153.203 | 4339.08 | 4388.035 | 4407.163 | 4520.621 | 3857.83 | 3697.314 | |

| median | 4448.922 | 4476.917 | 4654.814 | 4731.953 | 4701.596 | 4894.467 | 4418.513 | 4227.031 | |

| F21 | mean | 2854.438 | 3211.012 | 3266.611 | 2971.814 | 3230.192 | 3246.853 | 2689.216 | 2836.455 |

| std | 104.4249 | 40.49479 | 91.52014 | 48.47485 | 61.12815 | 34.9707 | 110.5395 | 77.75509 | |

| best | 2624.227 | 3095.647 | 3044.184 | 2876.981 | 3144.784 | 3169.299 | 2492.846 | 2695.025 | |

| worst | 2870.038 | 3215.319 | 3261.033 | 2972.478 | 3221.754 | 3253.185 | 2665.487 | 2831.948 | |

| median | 3047.414 | 3267.575 | 3445.266 | 3083.429 | 3357.7 | 3314.383 | 2909.121 | 2953.604 | |

| F22 | mean | 10,998.8 | 16,980.06 | 17,249.4 | 16,679.94 | 17,358.84 | 17,391.27 | 13,652.73 | 12,998.59 |

| std | 840.0132 | 408.6059 | 515.1264 | 2123.499 | 786.7584 | 417.0635 | 2907.168 | 2632.685 | |

| best | 9175.088 | 16,194.08 | 16,400.35 | 7408.293 | 13,847.85 | 16,508.11 | 9287.273 | 8554.412 | |

| worst | 10,922.91 | 17,105.06 | 17,387.52 | 17,186.66 | 17,511.75 | 17,358.62 | 12,992.19 | 12,206.8 | |

| median | 12,981.21 | 17,617.41 | 18,030.33 | 18,131.47 | 18,188.65 | 18,118.71 | 17,712.53 | 17,233.74 | |

| F23 | mean | 3581.643 | 4128.582 | 4620.601 | 3510.33 | 4719.551 | 4298.04 | 3307.936 | 3534.21 |

| std | 206.2312 | 91.56528 | 189.0447 | 68.58512 | 192.4512 | 124.7457 | 129.4303 | 133.5617 | |

| best | 3210.139 | 3939.255 | 4212.774 | 3411.791 | 4076.143 | 4022.329 | 3161.893 | 3350.576 | |

| worst | 3583.159 | 4138.696 | 4653.107 | 3497.276 | 4730.426 | 4302.796 | 3268.264 | 3537.664 | |

| median | 3952.577 | 4266.704 | 4987.475 | 3681.977 | 5042.447 | 4499.2 | 3650.281 | 3956.54 | |

| F24 | mean | 3731.615 | 4570.291 | 4977.045 | 3600.492 | 5383.01 | 4623.296 | 3516.178 | 3755.547 |

| std | 182.5002 | 145.2558 | 319.1224 | 58.59646 | 363.3184 | 151.54 | 256.9348 | 134.312 | |

| best | 3515.322 | 4265.015 | 4471.506 | 3480.267 | 4864.839 | 4229.267 | 3166.45 | 3428.635 | |

| worst | 3694.558 | 4581.483 | 4947.526 | 3600.111 | 5382.951 | 4625.649 | 3453.59 | 3798.043 | |

| median | 4218.938 | 4826.476 | 5813.129 | 3707.121 | 6419.906 | 4884.136 | 4227.354 | 3985.79 | |

| F25 | mean | 3110.898 | 14,313.62 | 15,991.59 | 14,126.02 | 16,062.94 | 33,891.03 | 3248.244 | 4482.356 |

| std | 35.02985 | 642.6781 | 1098.787 | 2319.172 | 1040.241 | 2965.027 | 78.15422 | 2045.493 | |

| best | 3039.404 | 12,625.6 | 13,102.36 | 8969.727 | 13,429.07 | 24,792.33 | 3123.983 | 3140.849 | |

| worst | 3115.631 | 14,328.07 | 15,887.54 | 14,173.48 | 16,125.58 | 34,648.34 | 3243.365 | 3573.945 | |

| median | 3192.159 | 15,495.95 | 17,971.18 | 18,126.43 | 18,101.86 | 38,039.97 | 3434.72 | 10,113.06 | |

| F26 | mean | 12,568.05 | 16,850.6 | 17,622.64 | 17,458.21 | 17,780.67 | 21,232.97 | 7701.159 | 10,970.81 |

| std | 1580.866 | 378.2373 | 535.129 | 2077.685 | 615.3835 | 1315.065 | 2403.614 | 1118.15 | |

| best | 9295.756 | 16,187.63 | 16,391.97 | 11,932.34 | 15,771.89 | 18,804.74 | 4126.587 | 8835.321 | |

| worst | 12,811.02 | 16,858.82 | 17,703.9 | 17,938.19 | 17,869.69 | 21,437.78 | 7611.067 | 11,041.12 | |

| median | 17,119.85 | 17,673.45 | 18,813.64 | 19,701.78 | 18,878.72 | 23,754.6 | 12,024.9 | 13,645.62 | |

| F27 | mean | 3808.675 | 6063.492 | 7074.102 | 4337.961 | 6850.284 | 6255.282 | 4020.108 | 3984.485 |

| std | 235.8524 | 455.9033 | 910.8321 | 196.7503 | 807.757 | 321.4446 | 209.8758 | 213.1498 | |

| best | 3484.347 | 5243.028 | 5646.505 | 4030.389 | 5131.224 | 5697.883 | 3657.32 | 3623.358 | |

| worst | 3811.76 | 6093.332 | 6923.087 | 4318.229 | 6767.458 | 6244.369 | 4020.047 | 3939.278 | |

| median | 4270.054 | 6871.226 | 8560.403 | 4815.071 | 8550.204 | 6939.098 | 4531.801 | 4417.38 | |

| F28 | mean | 3365.325 | 12,358.22 | 14,036.87 | 9989.373 | 14,426.55 | 15,690.86 | 3964.528 | 6578.806 |

| std | 37.49875 | 722.2068 | 1214.651 | 1047.597 | 1115.615 | 1440.892 | 1197.622 | 2123.016 | |

| best | 3298.155 | 9369.051 | 12,230.38 | 7433.328 | 12,290.5 | 12,654.15 | 3371.988 | 3527.566 | |

| worst | 3369.195 | 12,457.72 | 13,653.71 | 9811.273 | 14,322.91 | 15,661.53 | 3764.248 | 6543.57 | |

| median | 3456.389 | 13,161.69 | 16,948.66 | 12,382.35 | 17,099.86 | 18,663.63 | 10,185.55 | 10,123.58 | |

| F29 | mean | 5497.258 | 29,545.38 | 156,637.6 | 8103.622 | 309,734.5 | 25,633.53 | 5625.994 | 6369.865 |

| std | 590.1981 | 17,812.2 | 192,179.3 | 635.5026 | 341,597 | 9502.369 | 632.0883 | 889.2101 | |

| best | 4439.055 | 10,118.99 | 25,201.37 | 6565.725 | 28,361.95 | 13,564.98 | 4492.346 | 4770.456 | |

| worst | 5484.536 | 25,437.29 | 79,776.49 | 8036.524 | 144,237.5 | 23,549.28 | 5650.587 | 6220.656 | |

| median | 7052.816 | 75,688.88 | 999,331.1 | 9552.535 | 1,209,936 | 55,501.01 | 6680.621 | 9653.24 | |

| F30 | mean | 2,795,529 | 5.14 × 109 | 8.39 × 109 | 1.2 × 109 | 7.06 × 109 | 5.73 × 109 | 29,677,057 | 48,080,697 |

| std | 1,351,722 | 1.11 × 109 | 3.87 × 109 | 3.56 × 108 | 2.87 × 109 | 1.39 × 109 | 29,781,941 | 41,573,944 | |

| best | 903,013.9 | 2.54 × 109 | 2.27 × 109 | 6.3 × 108 | 1.76 × 109 | 2.99 × 109 | 4,194,733 | 3,665,377 | |

| worst | 2,509,618 | 5.03 × 109 | 7.53 × 109 | 1.12 × 109 | 7.05 × 109 | 5.69 × 109 | 15,930,412 | 26,709,720 | |

| median | 6,397,697 | 7.53 × 109 | 1.68 × 1010 | 2.14 × 109 | 1.23 × 1010 | 7.88 × 109 | 1.02 × 108 | 1.49 × 108 |

As shown in Table 4 and Figure A3, in the 100-dimensional benchmarks, the performance of the algorithms is more clearly differentiated: ECFDBO remains the best on most functions, with the best average optimization on a total of 20 functions; GODBO is still the main contender, with a slight edge on 8 functions; and there is an unexpected optimization of the COA algorithm on F3, with an average of 3.51 × 105 for COA and 5.56 × 105 for ECFDBO, suggesting that ECFDBO may fall into a local optimization on this particular function. Nevertheless, ECFDBO still performs best on most functions. For example, on the F7 function, which has a complex multi-peak structure, ECFDBO averages 3.29 × 103, significantly outperforming all algorithms except GODBO (2.75 × 103); even on the F3 function, which has a dominant COA, ECFDBO ranks 4th without significant performance degradation. In terms of standard deviation, best, median, and worst, ECFDBO wins again with 14, 18, 17, and 18 times, respectively. Especially in terms of standard deviation, the suboptimal algorithm BWO has only 5 optimal times, GODBO is only dominated by one function, F29, and DBO has even failed completely, creating a substantial performance gap with ECFDBO. Overall, ECFDBO shows more stable and efficient optimization in 100 dimensions compared to 30 dimensions and 50 dimensions.

Table 4.

F1–F30 Benchmark Function Test Results (dim = 100).

| ECFDBO | BWO | COA | PIO | BOA | NOA | GODBO | DBO | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | mean | 7.45 × 108 | 2.59 × 1011 | 2.73 × 1011 | 2.69 × 1011 | 2.61 × 1011 | 4.84 × 1011 | 3.7 × 1010 | 8.06 × 1010 |

| std | 3.24 × 108 | 5.57 × 109 | 9.06 × 109 | 1.3 × 1010 | 1.46 × 1010 | 1.66 × 1010 | 1.34 × 1010 | 6.3 × 1010 | |

| best | 2.28 × 108 | 2.46 × 1011 | 2.54 × 1011 | 2.33 × 1011 | 2.27 × 1011 | 4.41 × 1011 | 1.82 × 1010 | 2.93 × 1010 | |

| worst | 6.31 × 108 | 2.6 × 1011 | 2.75 × 1011 | 2.7 × 1011 | 2.62 × 1011 | 4.84 × 1011 | 3.61 × 1010 | 4.57 × 1010 | |

| median | 1.61 × 109 | 2.68 × 1011 | 2.88 × 1011 | 2.91 × 1011 | 2.84 × 1011 | 5.17 × 1011 | 6.51 × 1010 | 2.5 × 1011 | |

| F3 | mean | 556,312.7 | 377,040 | 351,483 | 475,644.8 | 511,431.5 | 783,361.5 | 414,625.3 | 595,729.4 |

| std | 155,549.4 | 50,453.21 | 16,245.01 | 176,121 | 174,033.4 | 87,093.05 | 106,216.4 | 250,553.3 | |

| best | 284,156.4 | 332,419.6 | 310,093.1 | 366,642.5 | 359,050.2 | 608,466.1 | 362,163.9 | 322,179.9 | |

| worst | 574,389.5 | 362,168.8 | 356,070.1 | 366,718 | 435,797 | 778,483.9 | 391,103.9 | 511,466.6 | |

| median | 964,242.4 | 560,682.7 | 374,778.9 | 883,061.5 | 947,707.4 | 975,420 | 951,696.2 | 1,369,806 | |

| F4 | mean | 1103.319 | 100,125.8 | 109,569.4 | 70,926.48 | 113,669.9 | 174,227.7 | 3727.137 | 19,936.42 |

| std | 109.6269 | 7489.947 | 11,451.92 | 16,469.75 | 10,194.13 | 14,779.12 | 1350.386 | 20,626.2 | |

| best | 948.5583 | 85,618.23 | 87,562.86 | 39,553.18 | 90,745.05 | 147,507.9 | 1956.474 | 3387.313 | |

| worst | 1076.578 | 101,194.6 | 108,947.3 | 72,477.39 | 115,869.6 | 174,697.2 | 3401.511 | 8784.596 | |

| median | 1481.919 | 110,236.8 | 126,735.7 | 100,351.8 | 130,039.5 | 198,696.7 | 9386.499 | 71,595.01 | |

| F5 | mean | 1744.406 | 2120.383 | 2130.764 | 2219.419 | 2091.949 | 2741.801 | 1684.584 | 1692.849 |

| std | 294.6566 | 22.99016 | 35.44666 | 55.07385 | 50.9796 | 66.98955 | 226.6237 | 205.015 | |

| best | 1373.308 | 2049.402 | 2060.307 | 2109.29 | 1936.35 | 2556.87 | 1284.559 | 1344.777 | |

| worst | 1714.638 | 2123.877 | 2133.904 | 2223.298 | 2106.804 | 2756.277 | 1692.64 | 1613.662 | |

| median | 2269.237 | 2159.801 | 2191.759 | 2307.57 | 2145.858 | 2837.671 | 2112.396 | 2048.001 | |

| F6 | mean | 678.0402 | 712.5224 | 713.1258 | 717.9441 | 712.8578 | 740.7731 | 665.6168 | 683.7687 |

| std | 8.109982 | 2.330429 | 3.682679 | 5.089617 | 3.313486 | 3.780802 | 9.107656 | 13.90364 | |

| best | 666.344 | 707.813 | 701.4139 | 707.4029 | 706.6868 | 729.5406 | 650.24 | 657.0897 | |

| worst | 677.4142 | 712.1859 | 713.4107 | 720.0742 | 713.603 | 741.2842 | 664.9418 | 685.7911 | |

| median | 698.8027 | 717.3 | 717.6363 | 725.4998 | 718.7438 | 747.9626 | 699.5684 | 707.3842 | |

| F7 | mean | 3293.137 | 3884.255 | 4032.22 | 4143.678 | 3944.478 | 11,069.35 | 2753.51 | 3015.819 |

| std | 200.926 | 61.64376 | 52.51027 | 104.3898 | 69.1295 | 479.8582 | 202.3837 | 256.7895 | |

| best | 2614.124 | 3761.538 | 3921.182 | 3800.1 | 3804.844 | 9824.999 | 2370.676 | 2389.143 | |

| worst | 3309.688 | 3879.63 | 4026.939 | 4147.419 | 3950.498 | 11,177.42 | 2698.88 | 3022.455 | |

| median | 3736.915 | 3984.399 | 4133.647 | 4285.594 | 4083.88 | 11,755.91 | 3180.337 | 3526.901 | |

| F8 | mean | 2222.104 | 2599.935 | 2598.42 | 2663.825 | 2578.03 | 3117.185 | 1903.055 | 2153.67 |

| std | 202.2045 | 34.72153 | 56.75434 | 48.33201 | 38.17371 | 73.77207 | 200.1381 | 254.3752 | |

| best | 1717.655 | 2526.253 | 2448.614 | 2550.778 | 2508.156 | 2964.277 | 1645.144 | 1722.929 | |

| worst | 2221.624 | 2602.339 | 2615.513 | 2667.069 | 2582.048 | 3115.349 | 1838.554 | 2236.892 | |

| median | 2620.501 | 2680.056 | 2705.458 | 2736.03 | 2661.689 | 3234.99 | 2372.973 | 2498.944 | |

| F9 | mean | 60,455.35 | 80,183.84 | 81,018.74 | 99,296.14 | 86,041.04 | 165,765.3 | 77,050.36 | 73,587.85 |

| std | 18655 | 4820.338 | 4885.766 | 6903.58 | 3395.674 | 10,464.62 | 8062.067 | 12,965.47 | |

| best | 27,080.32 | 65,379.89 | 69,477.43 | 78,988.2 | 80,435.73 | 142,076.6 | 58,765.57 | 35,460.35 | |

| worst | 60,669.35 | 80,472.15 | 80,475.79 | 102,981.4 | 85,766.82 | 165,432.2 | 77,127.33 | 75,350.98 | |

| median | 103,171.6 | 87,361.81 | 91,129.78 | 107,492 | 92,480.88 | 185,227.9 | 89,292.5 | 94,984.11 | |

| F10 | mean | 18,753.74 | 32,411.89 | 32,823.04 | 33,026.71 | 33,190.84 | 33,492.99 | 31,613.64 | 28,054.6 |

| std | 1731.832 | 578.5304 | 855.6955 | 632.246 | 635.5477 | 566.0072 | 2337.055 | 4967.889 | |

| best | 15,986.87 | 31,194.72 | 30,940.53 | 31,454.9 | 31,740.45 | 32,155.73 | 22,861.36 | 18,960.93 | |

| worst | 18,962.75 | 32,577.92 | 32,940.26 | 33,120.2 | 33,221.75 | 33,575.51 | 32,405.64 | 29,006.16 | |

| median | 23,201.87 | 33,521.24 | 34,038.48 | 34,043.18 | 34,294.1 | 34,400.95 | 33,363.61 | 33,813.22 | |

| F11 | mean | 30,562.76 | 375,307.3 | 251,568.9 | 234,786.9 | 435,013.7 | 361,867.1 | 278,041 | 229,312.4 |

| std | 6570.78 | 79,545.43 | 66,685.19 | 40,111.28 | 200,693.6 | 58,812.15 | 76,660.37 | 54,000.11 | |

| best | 19,355.85 | 253,923.3 | 143,315.6 | 125,476.8 | 165,383.3 | 250,249.2 | 134,985.8 | 151,359.1 | |

| worst | 29,760.43 | 368,621.2 | 225,813.5 | 239,133.6 | 361,261.8 | 364,866.1 | 276,670.5 | 220,557.2 | |

| median | 43,382 | 516,893.2 | 437,470.1 | 319,686.3 | 991,459 | 463,055.7 | 478,738.9 | 335,987.1 | |

| F12 | mean | 3.35 × 108 | 1.92 × 1011 | 2.03 × 1011 | 8.9 × 1010 | 1.91 × 1011 | 2.31 × 1011 | 3.21 × 109 | 7.15 × 109 |

| std | 1.47 × 108 | 1.23 × 1010 | 1.81 × 1010 | 1.77 × 1010 | 2.33 × 1010 | 2.12 × 1010 | 1.07 × 109 | 2.48 × 109 | |

| best | 1.23 × 108 | 1.6 × 1011 | 1.65 × 1011 | 5.96 × 1010 | 1.39 × 1011 | 1.73 × 1011 | 1.71 × 109 | 1.37 × 109 | |

| worst | 3.26 × 108 | 1.95 × 1011 | 2.04 × 1011 | 9.01 × 1010 | 1.94 × 1011 | 2.37 × 1011 | 2.84 × 109 | 6.64 × 109 | |

| median | 6.28 × 108 | 2.07 × 1011 | 2.39 × 1011 | 1.33 × 1011 | 2.36 × 1011 | 2.62 × 1011 | 5.34 × 109 | 1.52 × 1010 | |

| F13 | mean | 699,034 | 4.38 × 1010 | 4.9 × 1010 | 1.56 × 1010 | 4.62 × 1010 | 5.55 × 1010 | 1.01 × 108 | 3.83 × 108 |

| std | 1,404,644 | 3.91 × 109 | 5.34 × 109 | 3.05 × 109 | 5.96 × 109 | 4.91 × 109 | 1.46 × 108 | 2.85 × 108 | |

| best | 38,284.6 | 3.67 × 1010 | 3.65 × 1010 | 6.95 × 109 | 3.2 × 1010 | 4.24 × 1010 | 195,268 | 79,403,252 | |

| worst | 89,752.62 | 4.46 × 1010 | 4.86 × 1010 | 1.53 × 1010 | 4.71 × 1010 | 5.63 × 1010 | 53,102,300 | 2.98 × 108 | |

| median | 4,738,688 | 5.04 × 1010 | 6 × 1010 | 2.16 × 1010 | 5.63 × 1010 | 6.33 × 1010 | 6.02 × 108 | 1.29 × 109 | |

| F14 | mean | 3,357,850 | 85,212,469 | 1.02 × 108 | 68,947,180 | 1.51 × 108 | 1.76 × 108 | 5,119,034 | 19,596,326 |

| std | 2,371,169 | 29,998,080 | 34,349,981 | 22,965,475 | 91,411,206 | 43,582,925 | 3,686,515 | 14,389,273 | |

| best | 942,121.9 | 31,318,902 | 44,596,733 | 15,755,741 | 45,787,788 | 88,132,376 | 1,248,844 | 3,347,050 | |

| worst | 2,366,674 | 81,087,973 | 89,294,636 | 70,365,901 | 1.21 × 108 | 1.76 × 108 | 4,347,843 | 16,060,509 | |

| median | 10,420,191 | 1.57 × 108 | 1.82 × 108 | 1.41 × 108 | 3.93 × 108 | 2.66 × 108 | 18,256,524 | 68,172,667 | |

| F15 | mean | 78,930.7 | 2.34 × 1010 | 2.51 × 1010 | 5.57 × 109 | 2.41 × 1010 | 2.23 × 1010 | 13,072,258 | 61,298,556 |

| std | 219,072.8 | 3.02 × 109 | 4.33 × 109 | 1.12 × 109 | 5.12 × 109 | 5.04 × 109 | 21,948,861 | 79,951,870 | |

| best | 12,611.07 | 1.36 × 1010 | 1.51 × 1010 | 3.66 × 109 | 1.27 × 1010 | 1.39 × 1010 | 52,749.1 | 406,195.4 | |

| worst | 26,017.69 | 2.42 × 1010 | 2.57 × 1010 | 5.56 × 109 | 2.41 × 1010 | 2.24 × 1010 | 3,704,249 | 38,353,874 | |

| median | 1,220,023 | 2.84 × 1010 | 3.21 × 1010 | 8.21 × 109 | 3.38 × 1010 | 2.96 × 1010 | 77,559,893 | 3.09 × 108 | |

| F16 | mean | 7420.488 | 22,623.58 | 25,147.88 | 14,599.08 | 26,320.23 | 24,164.12 | 7951.092 | 8898.95 |

| std | 1072.346 | 1437.168 | 3156.294 | 843.7633 | 2172.911 | 1644.561 | 1032.6 | 1284.48 | |

| best | 5570.599 | 19,049.66 | 19,358.85 | 12,878.89 | 19,940.45 | 19,856.09 | 5912.598 | 6313.505 | |

| worst | 7379.487 | 22,827.85 | 25,509.03 | 14,565.16 | 26,451.68 | 24,062.32 | 7705.267 | 8900.273 | |

| median | 9546.879 | 25,581.13 | 30,852.49 | 16,755.66 | 30,537.53 | 27,797.61 | 10,722.2 | 11,774.85 | |

| F17 | mean | 6750.273 | 5,120,658 | 11,568,266 | 19,556.08 | 18,571,373 | 4,215,614 | 8014.545 | 9561.856 |

| std | 607.155 | 3,202,454 | 10,391,713 | 7302.894 | 12,013,187 | 2,973,714 | 1475.525 | 1472.375 | |

| best | 5389.357 | 1,038,674 | 719,282.4 | 11,665.35 | 431,620.6 | 253,709.6 | 5894.588 | 6670.773 | |

| worst | 6734.364 | 4,444,374 | 9,134,410 | 17,682.34 | 19,581,069 | 3,070,116 | 7672.809 | 9609.199 | |

| median | 7765.744 | 11,556,604 | 38,037,312 | 39,841.93 | 57,540,752 | 10,549,137 | 13,547.69 | 12,806.76 | |

| F18 | mean | 7,110,332 | 2.01 × 108 | 3.2 × 108 | 1.23 × 108 | 2.6 × 108 | 3.31 × 108 | 13,751,662 | 31,038,738 |

| std | 2,779,528 | 53,722,189 | 1.74 × 108 | 33,787,632 | 1.06 × 108 | 1.03 × 108 | 8,773,563 | 21,182,188 | |

| best | 2,437,016 | 87,289,245 | 38,115,404 | 61,624,382 | 67,995,553 | 1.5 × 108 | 2,827,917 | 5,159,165 | |

| worst | 6,988,379 | 1.97 × 108 | 2.93 × 108 | 1.18 × 108 | 2.57 × 108 | 3.23 × 108 | 11,671,407 | 29,795,728 | |

| median | 12,595,111 | 3.26 × 108 | 7.19 × 108 | 1.98 × 108 | 5.18 × 108 | 5.3 × 108 | 34,595,900 | 88,488,020 | |

| F19 | mean | 161,629.1 | 2.24 × 1010 | 2.72 × 1010 | 5.25 × 109 | 2.62 × 1010 | 2.45 × 1010 | 23,478,427 | 82,678,768 |

| std | 150,792.2 | 2.39 × 109 | 4.2 × 109 | 1.01 × 109 | 3.76 × 109 | 2.58 × 109 | 18,582,036 | 71,810,474 | |

| best | 17,306.4 | 1.72 × 1010 | 2.03 × 1010 | 3.31 × 109 | 1.84 × 1010 | 1.95 × 1010 | 235,256.2 | 1,656,899 | |