Summary

The microbiota influences intestinal health and physiology, yet the contributions of commensal protists to the gut environment have been largely overlooked. Here, we discover human- and rodent-associated parabasalid protists, revealing substantial diversity and prevalence in non-industrialized human populations. Genomic and metabolomic analyses of murine parabasalids from the genus Tritrichomonas revealed species-level differences in excretion of the metabolite succinate, which results in distinct small intestinal immune responses. Metabolic differences between Tritrichomonas species als o determine their ecological niche within the microbiota. By manipulating dietary fibers and developing in vitro protist culture, we show that different Tritrichomonas species prefer dietary polysaccharides or mucus glycans. These polysaccharide preferences drive trans-kingdom competition with specific commensal bacteria, which affects intestinal immunity in a diet-dependent manner. Our findings reveal unappreciated diversity in commensal parabasalids, elucidate differences in commensal protist metabolism, and suggest how dietary interventions could regulate their impact on gut health.

Keywords: Commensal protist, Tritrichomonas, parabasalid, microbiome, trans-kingdom, mucus, fiber, microbiota-accessible carbohydrate, metabolites, tuft cell

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

The gut microbiota is a complex and diverse microbial ecosystem that broadly impacts the development and function of the intestinal immune system1–5. This relationship has been studied predominantly with microbial communities, where conserved microbial ligands and metabolites have pleiotropic effects on the host6–10. However, some microbial species dominantly influence the immune system independent of other microbiota members11–13. For example, segmented filamentous bacteria induce T helper 17 (Th17) cells in the murine small intestine, and Bacteroides fragilis stimulates regulatory T cells in the colon12,13. While bacteria are the most well-characterized immunologically dominant symbionts, the gut microbiota also contains viruses, fungi, archaea, and protists that interact with the host and alter immune function.

Protists are often overlooked as members of the microbiota, in part due to the historical view of these microbes as universally pathogenic. However, commensal protists, including those in the Parabasalia phylum, are present in healthy mammalian guts and can dominantly shape intestinal immunity in mice14–18. Parabasalid protists from the genus Tritrichomonas are widespread in laboratory mice and dramatically alter the gut mucosa15,19–21. In the small intestine, Tritrichomonas species drive type 2 immunity through production of the metabolite succinate, which lengthens the gut and promotes tuft and goblet cell hyperplasia in the epithelium20,21. In the colon, Tritrichomonas musculis (Tmu) activates the inflammasome to promote Th1 and Th17 immunity15,22. The effects of these tritrichomonads on epithelial and immune functions significantly alter the severity of some enteric infections and several inflammatory diseases in mouse models, without inducing apparent pathology15,20–22. In humans, only two species of commensal parabasalids have been identified, although their effects on intestinal immunity are still unclear. Thus, despite the growing appreciation for how commensal parabasalids impact mucosal tissues, very little is understood about their diversity, metabolism, or microbial ecology.

Fundamental aspects of commensal parabasalid protist biology have been obscured by a lack of genomic information and their recalcitrance to in vitro culture. Consequently, the biology of commensal Tritrichomonas species is largely inferred from studies on the urogenital pathogenic parabasalids Trichomonas vaginalis and Tritrichomonas foetus. However, these pathogens infect different hosts and anatomical niches that may not reflect the specific adaptations of commensal parabasalids in the gut. Additionally, the ecological role of commensal parabasalids within the mammalian gut microbiota is unexplored. Parabasalid protists are generally fermentative21,23–25, but the specific carbohydrate sources used by commensal species and how their harvesting of these carbohydrates affects the intestinal environment is unknown.

In this work, we identified parabasalids in humans from both industrialized and non-industrialized populations, revealing large amounts of unappreciated diversity in human-associated parabasalids. In addition, we identified a previously undescribed murine Tritrichomonas species which we named Tritrichomonas casperi. Using genomic, transcriptomic, and metabolomic approaches, we determined that fermentative output from T. casperi differs from previously characterized murine tritrichomonads like Tmu, resulting in divergent immune responses in the small intestine. We used this metabolic information to create a framework for predicting the production of immunomodulatory metabolites by parabasalids, including human-associated species, based only on phylogeny. Further, we demonstrated that these different species’ preferences for fermenting plant polysaccharides or mucus glycans affect trans-kingdom interactions with bacteria. Finally, we revealed that dietary fiber composition acts as a lever to control protist-induced type 2 immunity. Our work provides mechanistic insights into how commensal parabasalids act as architects of the intestinal ecosystem and establishes a foundation for further studies of the diverse influences of protists on host immunity and microbiome ecology.

RESULTS

Discovery of a commensal Tritrichomonas species in mice

To discover uncharacterized parabasalid protists within laboratory mice, we screened DNA extracted from stool using pan-parabasalid PCR primers. These primers bind to highly conserved sequences of parabasalid rRNA loci and generate internally transcribed spacer (ITS) amplicons sufficient to distinguish parabasalid species using Sanger Sequencing. As expected, we identified Tmu (previously referred to as T. muris19) in a subset of our mice, but stool from another group of mice produced mixed signals that indicated the presence of multiple closely related species. Examination of the cecal contents of these mice by light microscopy revealed protists with two distinct sizes: a large variant consistent in size with Tmu and another variant approximately half the length.

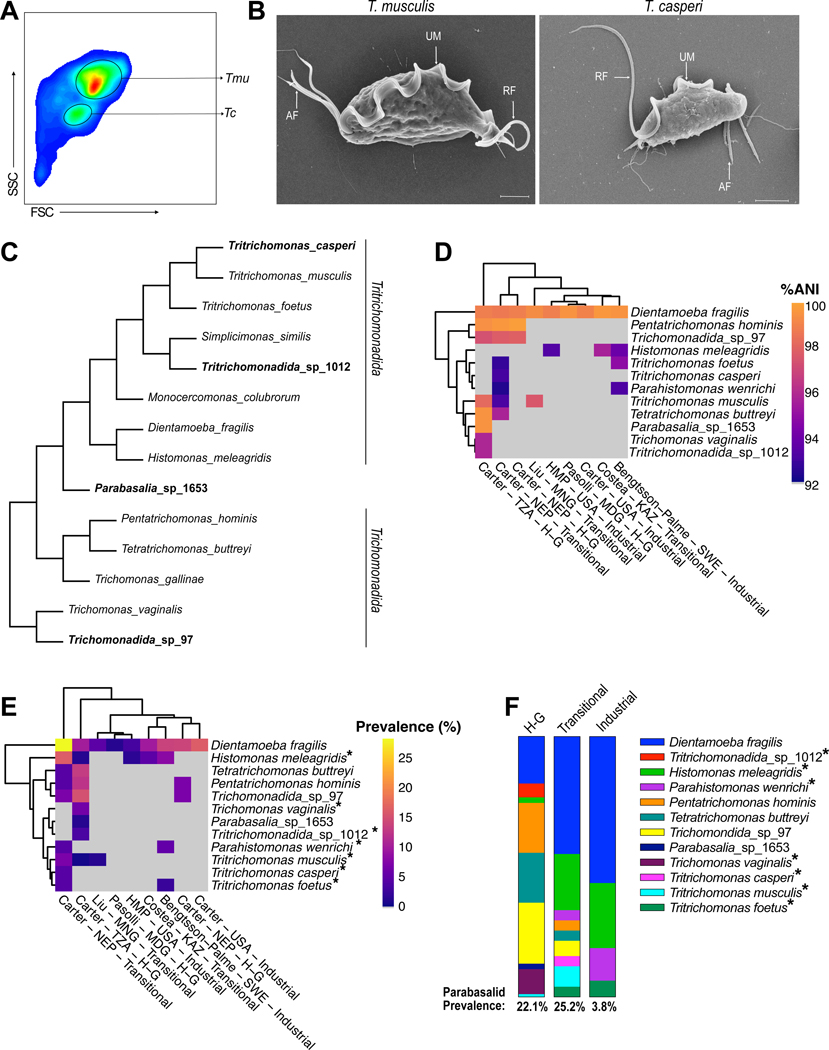

To determine if these two sizes constituted different morphologies of Tmu or two separate species, we purified both sizes of protist by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) and colonized protist-negative specific pathogen free (SPF) mice with either the large or small variant (Figure 1A). Mice maintained colonization with homogenously small or large protists, suggesting these were separate species. Ultrastructural examination of the small and large protists revealed an undulating membrane and recurrent flagellum typical of the Parabasalia phylum (Figure 1B and S1A)26. Additionally, this protist, like Tmu, had three anterior flagella, suggesting it belongs to the genus Tritrichomonas. To confirm this phylogenetic relationship, we compared ITS sequences from both protists, which revealed the smaller species is an uncharacterized murine isolate with accession number MF375342 that shares 83.4% identity with Tmu (Figure S1B). Thus, the smaller protist is an undescribed species, hereafter referred to as Tritrichomonas casperi (Tc). Healthy mice maintained high levels of Tc colonization for at least 3 months, indicating that Tc is a stable member of the murine microbiota (Figure S1C).

Figure 1. Identification of parabasalids in mice and humans.

(A) FACS purification of the large T. musculis (Tmu) and small T. casperi (Tc) protists isolated from a mouse cecum. FSC, forward scatter. SSC, side scatter. (B) SEM images of Tmu (left) and Tc (right). UM: Undulating Membrane, RF: Recurrent Flagellum, AF: Anterior Flagella. Scale bars are 2μm. (C) Cladogram of parabasalid protists based on ITS sequences, including mouse and human-associated parabasalids. Protists in bold indicate parabasalids discovered in this study. (D-F) Identification of human-associated parabasalids using mapping-based analysis of metagenomic data. (D) Percentage average nucleotide identity (ANI) of parabasalid metagenomic reads mapping to the corresponding reference protist sequence. Imperfect matches indicate that identified parabasalids are relatives of reference protists and not the same species. First author of the cohort study, country of origin, and population type (“Industrial”, “Transitional”, Hunter-Gatherer (“H-G”)) is indicated. Columns and rows are hierarchically clustered based on Euclidean distance. Cells corresponding to protists not identified in a population are colored grey. (E) Percentage prevalence of subjects in human cohorts with metagenomic reads mapping to reference parabasalids. (F) Prevalence of parabasalids identified in each population type. Asterisks denote protists with imperfect matches to the reference sequence, which are therefore relatives of the indicated species (E, F). (Abbreviations: TZA=Tanzania, NEP=Nepal, MNG=Mongolia, USA=United States of America, MDG=Madagascar, KAZ=Kazakhstan, SWE=Sweden, HMP=Human Microbiome Project).

Characterization of parabasalid diversity in humans

Rodent Tritrichomonas species are not known to colonize humans, but two commensal parabasalids, Pentatrichomonas hominis and Dientamoeba fragilis, can colonize the human gut. However, most studies have used targeted approaches that are unlikely to detect diverse species and primarily investigated samples from industrialized populations which harbor less diverse microbiomes18,27,28. Therefore, to identify additional human-associated parabasalids we created a reference set of 29 parabasalid ITS sequences (Table S1) to query previously published metagenomes from 1,800 human fecal samples representing 29 different populations28. These metagenomes encompass a wide array of human lifestyles, including industrial and hunter-gatherer populations, as well as “transitional” populations which have neither hunter-gatherer nor industrialized lifestyles. Using our parabasalid ITS database as reference sequences, we assembled ITS sequences from five parabasalids in these human samples, as well as a previously undescribed Simplicimonas species from cow feces which we refer to as Tritrichomonadida_sp_1012. While the human-associated sequences included D. fragilis and P. hominis, they also contained Tetratrichomonas buttreyi, which has only previously been identified in cattle. We also identified two previously undescribed candidate parabasalid species in the microbiomes of non-industrialized populations, which we refer to as Trichomonadida_sp_97 and Parabasalia_sp_1653 (Figure 1C and Table S1). Phylogenetic analysis suggested that Trichomonadida_sp_97 belongs to the Trichomonadida order and Parabasalia_sp_1653 potentially belongs to an undescribed Parabasalia order (Figure 1C).

The method used to identify these six parabasalids in the metagenomic assemblies suffers from low sensitivity inherent to assembly-based approaches. This sensitivity issue is further compounded by low sequencing depth in a subset of the metagenomic datasets which may have limited the number of identified protists. We therefore analyzed these datasets using a mapping-based approach, which improves sensitivity of detection but does not enable accurate classification beyond identifying the closest match in our reference database (Figure S1D and 1E). This mapping-based methodology revealed a strong effect of sequencing depth on parabasalid identification; we therefore implemented a 5Gbp minimum sequencing depth threshold for further analysis (Figure S1F). This curated database of 557 metagenomes indicated an inverse relationship between industrialization and parabasalid colonization frequency, with parabasalids identified in more than 22% of samples from non-industrialized populations but only 3.8% of industrialized samples (Figure 1D, 1E, 1F). D. fragilis was the most prevalent parabasalid in industrialized and transitional populations, but not in the hunter-gatherer populations. The microbiomes of non-industrialized individuals contained many other parabasalid species including T. buttreyi, Trichomonadida_sp_97, and Parabasalia_sp_1653. Similarly, parabasalids closely related to T. vaginalis, Tritrichomonadida_sp_1012, and the murine tritrichomonads Tmu and Tc, were also present in some non-industrialized populations (Figure 1D, 1E, and 1F). Together, these results are consistent with previous studies suggesting that industrialization is associated with decreased diversity of microeukaryotes in the microbiome17,18, but also demonstrate that a large amount of unappreciated diversity exists among human-associated commensal parabasalids.

Tmu and Tc stimulate divergent immune responses in the small intestine

D. fragilis belongs to the same phylogenetic order as the murine tritrichomonads Tmu and Tc, and we identified even closer relatives of these murine protists in non-industrialized human populations. Thus, in addition to revealing unappreciated parabasalid diversity within human microbiomes, our results reinforce the utility of murine tritrichomonads for understanding the functional impact of commensal parabasalids on the intestinal environment. Previously characterized murine tritrichomonads, such as Tmu, induce tuft cell hyperplasia and type 2 immunity in the distal small intestine (SI) through excretion of the metabolite succinate19–22. However, tuft cell hyperplasia, which results from SI type 2 immunity19–21, was absent in mice colonized with Tc (Figure 2A, 2B, 2C, and S2A). Although Tc stimulated a subtle increase in IL13-positive group 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s), which are more sensitive to weak type 2 stimuli, this increase was markedly lower than the expansion of IL13-positive ILC2s induced by Tmu (Figure 2D, 2E, and S2B). Moreover, Tc colonization reduced the proportion of small intestinal GATA3+ CD4+ T helper 2 (Th2) cells associated with adaptive type 2 immunity, which contrasted with the significant expansion of Th2 cells in Tmu colonized mice (Figure 2F and S2C). Tc was at least as abundant as Tmu along the length of the intestine, suggesting that the lack of type 2 immune induction was not due to colonization deficiencies (Figure S2D). These results suggest that Tc is unique among known murine commensal tritrichomonads because it does not induce type 2 immunity in the distal SI.

Figure 2. T Cell responses to Tmu and Tc differ in the distal SI.

(A) Tuft cell frequency measured by flow cytometry in the distal SI epithelium of uncolonized (Ctrl) mice or those colonized with Tmu or Tc for two weeks. (B) Representative flow cytometry plots of tuft cells. SiglecF marks tuft cells, EpCAM marks epithelial cells. (C) Representative immunofluorescence microscopy images of tuft cell hyperplasia in the distal SI of mice with or without each protist for two weeks. Scale bars are 50μm. (D) Frequency of ILC2s in the lamina propria of the distal SI in Ctrl mice or mice colonized with Tmu or Tc for two weeks. IL13 was measured using the IL13 reporter Smart13 mice (E) Representative flow cytometry plots of ILC2s. (F) Frequency of GATA3+ CD4+ T cells (Th2 cells) in the lamina propria of the distal SI after three weeks of colonization. (G) Frequency of IFNγ and IL-17 positive CD4+ T cells in the distal SI lamina propria after three weeks of Tc colonization, or without protist colonization (Ctrl). Cytokines were stimulated ex vivo and cells were stained for intracellular cytokines. (H) Representative flow cytometry plots of Th1 and Th17 cells in the distal SI with and without Tc. Graphs (A, D, F, G) depict mean. Each symbol represents an individual mouse from two to three pooled experiments (A, D, F, and G). *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001, NS, not significant by Student’s t test.

Previous work demonstrated that Tmu increases CD4+ T helper 1 (Th1) and T helper 17 (Th17) cells in the cecum and colon15,22. Therefore, we examined whether Tc stimulates these same immune responses in the distal SI. IFNγ producing Th1 cells and IL17 producing Th17 cells, as well as IFNγ and IL17 double positive CD4+ T cells, significantly increased in the distal SI of Tc colonized mice compared to protist-free controls (Figure 2G, 2H, and S2C). Because the two species stimulate divergent responses in the distal SI, we wondered whether co-colonization would alter the mucosal response to these protists. To address this question, we co-colonized mice with Tmu and Tc or singly with each protist. Tuft cell hyperplasia was identical in co-colonized and Tmu singly colonized mice, and Tmu and Tc abundance was unaffected by co-colonization (Figure S2E and S2F). This finding suggests that Tmu dominates the mucosal immune response in the distal SI when both species are present simultaneously.

Th1 and Th17 induction is a common tritrichomonad immune response

Although Tmu induces Th1 and Th17 cells in the colon and type 2 immunity in the distal SI, no study has examined the immune response in both intestinal tissues using the same protist isolate. This leaves some ambiguity regarding whether different strains or species contribute to these heterogeneous Tmu-induced immune responses. We therefore characterized CD4+ T cell populations induced by Tmu and Tc in the colon. Both Tmu and Tc significantly increased Th1, Th17, and IFNγ-IL17 double positive T cells (Figure 3A and 3B). Commensal bacteria were not required for induction of these responses, as both protists were sufficient to drive immunity in monocolonized gnotobiotic mice (Figure S3A and S3B). Other T cell responses appeared unaffected by protist colonization; for example, regulatory T cells did not change with colonization by either species (Figure S3C).

Figure 3. Th1 and Th17 induction is the shared tritrichomonad-induced immune response.

(A) Frequency (top) and absolute abundance (bottom) of IFNγ and IL-17 positive CD4+ T cells in the colonic lamina propria of WT and Caspase1−/− mice after three weeks of protist colonization, or without protist colonization (Ctrl). (B) Representative flow cytometry plots of the frequency of IFNγ and IL17 positivity in colonic lamina propria CD4+ T cells. (C) Frequency and absolute abundance of IFNγ and IL-17 positive CD4+ T cells in the distal SI lamina propria of Trpm5−/− mice after three weeks of Tmu colonization, or without protist colonization (Ctrl). (D) Representative flow cytometry plots of the frequency of IFNγ and IL17 positivity in distal SI lamina propria CD4+ T cells from Trpm5−/− mice with or without Tmu. Cytokines were stimulated ex vivo and cells were stained for intracellular cytokines. Graphs depict mean. Each symbol represents an individual mouse from two (C) or three (A) pooled experiments. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001, NS, not significant by Student’s t test.

Microbial adhesion has been proposed as a nonspecific Th17-inducing signal29, and previous work identified examples of Tmu adhering to colonic epithelial cells15. To address the prevalence of epithelial adhesion by Tmu and Tc, we developed a polyclonal antibody against Tmu. This antibody recognizes Tmu, and to a lesser extent Tc, and stains both trophozoites and pseudocysts of Tmu (Figure S3D and S3E). We gently flushed the colons of Tmu colonized mice with PBS to remove unadhered protists and then searched for adherent protists by fluorescence microscopy. Adherent protists were extremely rare (0–3 per colonic tissue section) and thus are unlikely to drive immune responses across the entire tissue (Figure S3F, S3G, and S3H).

Tmu requires the inflammasome to fully induce colonic Th1 and Th17 cells15, so we hypothesized that Tc also stimulates Th1 and Th17 immunity by activating the inflammasome. Mice deficient in the inflammasome component Caspase-1 had partially suppressed colonic immune induction by Tmu (Figure 3A and 3B)15. Caspase-1 was similarly important for the immune response in Tc colonized mice, suggesting that both protists stimulate Th1 and Th17 immunity in the colon through a shared effector.

Although Tmu and Tc induce the same Th1 and Th17 immune responses in the colon, only Tc appears to drive this response in the distal SI. We reasoned that the lack of Th1 and Th17 induction in the distal SI by Tmu may be due to succinate-driven type 2 immunity masking this response. The poor cellular viability caused by processing tissue with active type 2 immunity prevented direct measurement of IFNγ+ and IL17+ T cells in the distal SI of wild type Tmu colonized mice. Instead, we measured Th1 and Th17 induction in Trpm5−/− mice, which lack the tuft cell taste chemosensory component TRPM5 and are insensitive to succinate-induced type 2 immunity20,21. Like Tc in wild type mice, Tmu stimulated expansion of IFNγ+, IL17+, and IFNγ-IL17 double positive CD4+ T cells in the distal SI of Trpm5−/− mice (Figure 3C and 3D). Altogether, these data suggest tritrichomonads can induce Th1 and Th17 immunity across the intestinal tract, but metabolic production of succinate by Tmu masks this response in the distal SI by driving type 2 immunity.

Metabolic differences in tritrichomonads underly the divergent immune responses

Succinate excreted by Tmu stimulates the succinate receptor (GPR91) on tuft cells and drives type 2 immunity in the distal SI (Figure S4A)20,21. Because Tc does not stimulate type 2 immunity, we hypothesized that Tc does not produce succinate. We directly measured in vivo succinate concentrations in the ceca of Tmu and Tc colonized mice using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS). Tmu colonization significantly increased the extracellular concentrations of cecal succinate compared to uncolonized controls, while Tc colonized mice showed no change in succinate levels (Figure 4A).

Figure 4. Metabolic differences in tritrichomonads underly divergent immune responses.

(A) Extracellular succinate concentration in the cecal contents of uncolonized mice (Ctrl) or mice colonized with each protist for 3 weeks. (B, C) Genome assemblies of Tmu (B) and Tc (C). Outermost rings show position (in Mbp), middle ring shows genome assembly contigs, inner ring shows GC content in 10kb sliding windows (blue, above genome average; red, below genome average). Total genome size is at the center of each circle. (D) Schematic of metabolic pathways in parabasalid protists. Magenta boxes surround fermentative pathways found in Tc, cyan box surrounds the pathway found in Tmu. (E and F) Gene expression levels (in transcripts per million (TPM)) in the cecum vs. distal SI for Tmu (E) and Tc (F). Transcripts in the lactate and succinate fermentative pathways are labelled if present. (G and H) Intracellular succinate (G) and lactate (H) measurements from purified Tmu and Tc cell lysates. (I) Cladogram of parabasalids. Green shading shows predicted succinate producers. Purple shading shows predicted lactate producers. Asterisks signify metabolic confirmations made in this study. “Human Tritrichomonadida/Trichomonadida” represent previously undescribed human-associated parabasalids detected in Figure 1, but for which sequence information was not obtainable. Phylogenetic orders are labelled on the right. Graphs (A, G, H) depict mean with SD. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, NS, not significant by Student’s t test.

Two fermentative pathways are currently established in parabasalid protists based on studies of T. vaginalis and T. foetus24,30. T. vaginalis maintains redox homeostasis by converting pyruvate to lactate through the action of lactate dehydrogenase. In T. foetus, and presumably Tmu, redox balance occurs via conversion of malate to succinate by the sequential activity of fumarase and fumarate reductase. Lactate or succinate are then excreted as waste products from the protists. However, as with succinate, Tc colonization did not result in an increase in extracellular lactate in mouse cecal contents (Figure S4B).

To identify the metabolic pathways present in each protist, we sequenced the genomes of both Tmu and Tc. Massive numbers of repeat regions in parabasalid genomes make short-read genome assemblies challenging31–33. Therefore, we used Nanopore long-read sequencing to assemble these parabasalid genomes (Figure 4B, 4C, and S4C). As predicted, Tmu encodes the succinate production pathway, but not the lactate pathway (Figure 4D, cyan box). Despite the lack of succinate or lactate excretion by Tc, it encodes both the succinate and lactate production genes (Figure 4D, magenta boxes). To assess the relative contribution of each pathway to Tc metabolism, we performed RNA sequencing on Tmu and Tc isolated from the distal SI and ceca of mice. Both species expressed genes in the succinate pathway at high levels, whereas lactate dehydrogenase was expressed by Tc but relatively less than fumarate reductase (Figure 4E and 4F). Transcriptomics also confirmed that expression of these fermentative pathways does not vary drastically between the distal SI and cecum. Contrary to our hypothesis based on LC-MS measurements from cecal supernatants and the lack of type 2 immune induction by Tc, these data suggest that Tmu and Tc both use the succinate fermentation pathway.

To directly determine the usage of each fermentative pathway, we measured the intracellular concentrations of both metabolites in lysates from purified protists. Consistent with the genomic and transcriptomic analyses, cell extracts from purified Tmu and Tc contained high levels of succinate and low levels of lactate (Figure 4G and 4H). These intracellular succinate concentrations suggest that both protists use the succinate pathway to maintain redox homeostasis, yet cecal LC-MS measurements and the absence of tuft cell hyperplasia suggest Tc does not excrete this metabolite. Some bacteria can metabolize succinate into short chain fatty acids such as propionate and butyrate34,35. Therefore, we reasoned that Tc might also metabolize succinate in a similar manner. However, short chain fatty acids, including butyrate, propionate, and acetate, were not more abundant in lysates from Tc than Tmu (Fig. S4D). We next attempted to identify other potential succinate derivatives in Tc using additional mass spectrometry methods capable of identifying over 400 microbiota-produced metabolites36, but of the 48 metabolites we identified none had significantly higher abundance in Tc (Figure S4E and Table S2). Altogether, these data indicate that although both protists use succinate production for redox homeostasis, Tc does not excrete sufficient succinate into the intestinal lumen to stimulate type 2 immunity. However, the precise metabolic mechanism remains undefined.

We observed that T. foetus, Tmu, and Tc all use the succinate fermentative pathway and belong to the order Tritrichomonadida, whereas T. vaginalis uses the lactate pathway and belongs to the order Trichomonadida. This led us to hypothesize that an evolutionary split had occurred within the Parabasalia phylum, with lactate versus succinate production representing a branch point. To investigate this hypothesis, we analyzed the fermentative metabolism of two additional intestinal parabasalids: P. hominis (a human-associated Trichomonadida) and Monocercomonas colubrorum (a reptile-associated Tritrichomonadida). As predicted, P. hominis cultures contained high concentrations of lactate whereas M. colubrorum cultures contained high concentrations of succinate (Figure S4F). These data suggest that the phylogenetic classification of new and uncharacterized parabasalid species can help predict the production of the immunomodulatory metabolites lactate and succinate (Figure 4I). For example, this predictive framework suggests that the human-associated parabasalid Trichomonadida_sp_97 produces lactate, whereas the human-associated Tritrichomonas species identified here likely generate succinate (Figure 4I).

Tmu and Tc occupy different nutritional niches within the microbiota

In addition to the microbiota’s metabolic output, the metabolic input of each species also shapes its interactions with other microbes and the host37–39. Plant polysaccharides such as dietary fibers are the most commonly utilized carbon source by the microbiota, and collectively are referred to as dietary Microbiota Accessible Carbohydrates (MACs)40–42. However, non-dietary MACs are also prevalent in the intestine. For example, mucus secreted by intestinal epithelial goblet cells provides a complex and glycan-rich nutrient source for microbes capable of breaking down its diverse glycosidic linkages42–44. To determine whether Tmu and Tc ferment dietary MACs, we altered the fiber content of mouse diets using defined chow similar to a previous study21. Fibers in these diets were restricted to inulin, a fermentable fiber that acts as a dietary MAC, and cellulose, a non-fermentable fiber that passes largely undigested through the intestine. Standard mouse chow, which contains a complex mixture of plant material, was used as a control (complex). Tmu abundance was high in mice fed complex chow and defined chow with inulin and cellulose (def-CI) or inulin alone (def-I) (Figures 5A and S5A). However, Tmu colonization was dramatically reduced when fiber was removed entirely (def-None) or cellulose was the sole fiber (def-C) (Figures 5A and S5A). In contrast, Tc colonization was completely independent of dietary MACs, as this protist’s abundance did not decrease on any of the defined diets (Figure 5B, S5B). These results suggest that Tmu utilizes dietary MACs, whereas Tc may rely on host-derived carbohydrates as a nutritional source.

Figure 5. Tmu and Tc occupy different nutritional niches within the microbiota.

(A) Abundance of Tmu and (B) Tc in the stool of mice fed diets with defined fiber compositions for two weeks or fed standard chow (complex) as a control. Fibers in the defined diets are limited to inulin (I), cellulose (C), or no fiber (None). (C) 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing in the colon of uncolonized (Ctrl) mice or mice colonized with Tmu or Tc for three weeks. The 15 most abundant taxa are shown, and data is the average abundance from five mice per group. (D) Relative abundance of bacteria depleted by Tmu and Tc colonization in each region of the intestine, from 16S Sequencing. (E) Representative microscopy showing localization of Tmu and Tc in the colons of mice fed complex chow. Scale bars are 100μm. (F) Quantification of protist localization by microscopy. Higher mucus/lumen protist signal indicates tighter localization to the colonic mucus layer. (G) Number of CAZymes encoded by protists and bacterial competitors with predicted activity against host and plant glycans. (H) Abundance (in TPM) of putative mucus-utilization genes in Tc and Tmu from transcriptomics data. CAZymes were identified by dbCAN2. For putative mucolytic CAZymes the glycoside hydrolase family (GH) is indicated in brackets. Graphs (A, B, D, F) depict mean, error bars depict SD in (D). Each symbol represents an individual mouse from one to three pooled experiments (A). **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001, NS, not significant by Mann-Whitney test (A, B) or Student’s t test (F).

The gut microbial ecosystem is a complex and species rich community, with most nutritional niches occupied by one or more community members competing for limited resources37,45,46. This scarcity of open niches can prevent new microbes from colonizing the gut, a phenomenon termed “colonization resistance”. However, commensal tritrichomonads such as Tmu and Tc are unusual as they appear unaffected by colonization resistance. Inoculation with as few as one thousand Tmu or Tc protists can result in robust colonization of SPF mice without niche-clearing manipulation. We reasoned that Tmu and Tc overcome colonization resistance due to one of two possibilities, (1) Tmu and Tc occupy unique and uninhabited niches within the gut ecosystem, or (2) Tmu and Tc outcompete other microbes that occupy their preferred niche. Due to the dearth of unoccupied niches, we favored the second hypothesis. Therefore, identifying microbes eliminated by tritrichomonad colonization could offer insights into the preferred nutritional niches of these protists.

To investigate trans-kingdom competition between tritrichomonads and bacteria, we performed 16S rRNA sequencing on the distal SI, cecum, and colon contents from mice with and without Tmu or Tc (Figures 5C, S5C, and S5D). In all three regions of the intestine, Tmu colonization dramatically reduced Bifidobacterium pseudolongum and Turicibacter sanguinis abundance (Figure 5C, 5D, S5C, and S5D). Alternatively, Tc colonization decreased Akkermansia muciniphila to undetectable levels (Figures 5C, 5D, and S5C–E). Bifidobacteria are prolific fiber degraders and Turicibacter abundance is positively correlated with fiber consumption47,48, consistent with Tmu outcompeting these bacteria for dietary MACs. A. muciniphila is a mucin specialist, suggesting that Tc may preferentially consume host mucus glycans.

In the colon, mucus forms a highly interlinked network that is tightly associated with the intestinal epithelium and acts as a barrier against microbial encroachment2. Mucolytic bacteria such as A. muciniphila preferentially colonize the mucus layer. To determine whether Tc also localizes to the colonic mucus layer, we used quantitative imaging to map the location of each protist along the mucosal-luminal axis of the intestine. Tmu was present at both the mucosal interface and in the lumen of the colon, consistent with a preference for dietary MACs (Figures 5E and 5F). Tc instead tightly co-localized with the colonic mucus layer, corroborating its preference for mucus glycans.

Mucus glycans and fiber are composed of diverse sugar structures that require a large repertoire of carbohydrate active enzymes (CAZymes) to catabolize. To investigate the glycan utilization potential of Tmu and Tc, we used dbCAN2 to identify CAZymes in the protist genomes49. Additionally, we annotated CAZymes in the genomes of the putative bacterial competitors B. pseudolongum, T. sanguinis, and A. muciniphila. Consistent with our hypothesis of nutritional trans-kingdom competition, B. pseudolongum and T. sanguinis were enriched for CAZymes active on plant polysaccharides, whereas A. muciniphila was enriched for host-active CAZymes (Figures 5G and S5F). However, Tmu and Tc each encoded a large number of both plant and host-active CAZymes, suggesting that these protists are capable of breaking down a wide variety of carbohydrate substrates. We therefore used the protist transcriptomes to determine the expression levels of mucus active CAZymes. Tc expresses CAZymes with predicted activity against all of the sugar subunits found on mucus glycans, and these CAZymes are members of Glycoside Hydrolase (GH) families associated with mucus degradation (Figure 5H)27,43. In particular, Tc expresses high levels of galactosidases, which can cleave the abundant galactose residues from mucus glycans. Galactose cannot be directly catabolized and must be converted to glucose to be oxidized for energy production. Consistent with a galactose-dependent metabolism, Tc also expresses high levels of UDP-galactose 4-epimerase used to convert galactose to glucose50. However, these putatively mucolytic CAZymes identified in Tc are also expressed by Tmu, albeit at lower levels of expression, suggesting that Tmu may also be capable of fermenting mucus glycans (Figure 5H).

Dietary MAC deprivation causes Tmu to switch to mucolytic metabolism

Although Tmu colonization was markedly reduced when mice were fed the def-C diet, a small number of protists survived in a subset of these mice (Figure 5A and S5A). This observation, combined with the expression of mucolytic CAZymes, suggested that Tmu can utilize mucus glycans to survive dietary MAC deprivation. To investigate this possibility, we examined the localization of Tmu in the colons of mice fed cellulose as the sole fiber. The few remaining Tmu cells in def-C fed mice strongly co-localized with the mucus layer (Figure 6A and 6B).

Figure 6. Dietary MAC deprivation causes Tmu to switch to a mucolytic metabolism.

(A) Representative images of Tmu in the colons of mice fed complex chow (left) and defined chow with cellulose (def-C) chow (right) for two weeks. Scale bars are 100μm. Inset shows mucus-associated Tmu during fiber starvation. (B) Quantification of microscopy on Tmu localization to the mucus layer when mice are fed complex chow or def-C chow. Higher mucus/lumen protist signal indicates tighter localization to the colonic mucus layer. (C) Growth curves of Tmu cultured in vitro, using the PBF medium that we developed, with maltose (cyan) or mucus (green) added as carbon sources, or with no defined carbon source added (grey). (D) Differential gene expression from Tmu grown in vitro with either maltose or mucus as a carbon source. Green data points indicate putative mucus-utilization genes with increased expression when grown in the presence of mucus. GH families for putative mucolytic CAZymes are labelled. Dashed lines delineate the fold change cutoff (1.5-fold). (E) Tmu abundance in the stool of mice fed def-CI or def-C chow for two weeks, with or without an antibiotic cocktail (VNA). Antibiotics used are Vancomycin, V; Neomycin, N; Ampicillin, A. (F) Tmu abundance in the cecal contents of mice fed cellulose chow for two weeks with different antibiotic treatments. (G) 16S rRNA sequencing of stool from Tmu-colonized mice fed def-C chow for two weeks with different antibiotic treatments. Each column represents an individual mouse. (H) Relative abundance of known mucolytic bacteria in mice from each group in (G). LD, limit of detection. Graphs (B, C, E, F, H) are plotted as mean, error bars depict SD in (C). Each symbol represents an individual mouse from one to three pooled experiments (B, E, and F). **p<0.01, ****p<0.0001, NS, not significant by Mann-Whitney test (E, F) or Student’s t test (B).

We next sought to study this metabolic shift in a reductionist model to understand the effects of specific substrates on protist growth and survival without the inherent complexity of the intestinal environment. Although some parabasalids can be propagated in vitro, murine gut commensals such as Tmu and Tc do not grow with existing culture conditions. While previous studies by our group and others have cultured these protists short-term to eliminate bacteria and fungi with antibiotics15,19–21, growth does not occur; instead, the protists slowly die over the course of several days. This method is sufficient to colonize mice with pure protists but does not allow for mechanistic investigation of protist biology. All currently used media for parabasalid culture add serum as a source of lipids and micronutrients. However, serum is a heterogenous and undefined additive, which could contain components that are toxic to microbes. Thus, we created an artificial serum containing both lipids and micronutrients. Tmu grew when artificial serum was added to the cultures, whereas heat-inactivated bovine serum killed the protists (Figure S6A). By combining this artificial serum with additional changes to components of the growth medium, we created a medium, Parabasalid Bi-phasic Formulation (PBF), that supports the long-term culture of Tmu (Figure S6B). Despite the success of PBF for Tmu culture, it did not support the growth of Tc. Nevertheless, adding mucus to PBF medium improved Tc survival 5-fold, supporting the conclusion that this species ferments mucus glycans (Figure S6C).

Next, we cultured Tmu axenically with either the simple sugar maltose or with mucus as the primary carbon source and found that both glycans supported robust protist growth (Figure 6C). To confirm whether the CAZymes expressed by protists in vivo (Figure 5H) may support mucus glycan harvesting, we performed RNA sequencing on Tmu grown with either maltose or mucus (Figure 6D). Tmu grown with mucus significantly increased the expression of 16 CAZymes in GH families associated with mucolytic activity relative to protists grown with maltose. These upregulated CAZymes included the putative mucolytic genes identified above, supporting the hypothesis that both protists use these CAZymes to metabolize mucus glycans. In addition, the gene encoding the galactose-utilization enzyme UDP-galactose-4-epimerase was upregulated in mucus-grown Tmu, consistent with a metabolic shift towards fermenting mucosal sugars.

The discrepancy between Tmu survival on mucus in vivo (in which the protists barely survive) and in vitro (where the protists thrive) led us to consider what factors might account for this difference. One major distinction is the absence of bacteria in the in vitro cultures. To determine if mucolytic bacteria outcompete Tmu during dietary MAC deprivation in vivo, we treated Tmu-colonized mice with antibiotics before switching to the def-C diet. Strikingly, antibiotic treatment with a cocktail of vancomycin, neomycin, and ampicillin restored Tmu colonization in the absence of dietary MACs (Figure 6E). To narrow down the potential bacterial competitors, we tested the ability of each antibiotic to restore colonization. Neomycin and vancomycin were dispensable for Tmu survival, whereas ampicillin treatment completely restored colonization (Figure 6F and S6D). Consistent with ampicillin relieving competition for the mucus niche during fiber deprivation, Tmu localized tightly to the mucus layer (Figure S6E and S6F).

To identify specific bacteria that outcompete Tmu during dietary MAC starvation, we profiled the changes to the bacterial microbiome during treatment with each of the individual antibiotics. Mice treated with ampicillin had undetectable levels of Bacteroidetes and A. muciniphila, known mucolytic members of the microbiota (Figure 6G, 6H, and S6G)43. In contrast, the mice treated with no antibiotics, vancomycin, or neomycin all had high levels of Bacteroidetes, A. muciniphila, or both. These results suggest that Tmu switches to a mucolytic metabolism during dietary MAC starvation but is largely outcompeted by the mucolytic bacteria Bacteroidetes spp. and A. muciniphila.

Diet-protist interactions shape the host immune response

Next, we characterized dietary MAC fermentation by Tmu using axenic in vitro culture. Although inulin was sufficient for Tmu to colonize mice (Figure 5A), Tmu failed to grow in PBF medium with inulin as the carbon source (Figure 7A). To understand this apparent discrepancy, we investigated the localization of Tmu in mice fed def-CI chow, in which inulin is the sole dietary MAC. Similar to mice starved of dietary MACs, Tmu was tightly associated with the mucus layer in mice fed def-CI chow (Figure 7B and 7C). This suggests that although inulin is sufficient for Tmu to colonize mice at high abundance, Tmu does not directly utilize inulin and instead ferments mucus glycans when inulin is the sole dietary MAC. Notably, many Bacteroidetes species can ferment both inulin and mucus, suggesting that these bacteria may utilize inulin when the fiber is present, thereby reducing competition with Tmu for mucus glycans43,51. Bacteroidetes abundance did not change in Tmu-colonized mice fed def-C chow compared to def-CI chow, whereas Tmu levels decreased in def-C chow (Figure 7D and 5A). This observation is consistent with Bacteroidetes outcompeting Tmu for mucus glycans when all dietary MACs, including inulin, are removed. However, this same dietary switch in Tc-colonized mice results in a significant decrease in Bacteroidetes abundance, consistent with the ability of Tc to outcompete mucolytic bacteria for the mucus niche (Figure 7D).

Figure 7. Diet-protist interactions shape the host immune response.

(A) In vitro growth curve of Tmu cultured in PBF medium with maltose or inulin added as carbon sources, or with no defined carbon source added. (B) Representative images of Tmu in the colons of mice fed complex chow or defined chow with cellulose and inulin (def-CI) for three weeks. Scale bars are 50μm. (C) Quantification of microscopy on Tmu localization to the colonic mucus layer when mice are fed complex chow or def-CI chow. Higher mucus/lumen protist signal indicates tighter localization to the colonic mucus layer. (D) Relative abundance of Bacteroidetes bacteria in the stool of mice colonized by Tmu or Tc, with the fermentable fiber inulin or the non-fermentable fiber cellulose as the only fiber sources in the diet. (E) Maximum Tmu culture density when grown in vitro with different dietary MACs added as carbon sources to PBF medium. All statistical comparisons are relative to culture with no defined carbon source added. (F) Differential expression of Tmu transcripts grown in vitro with either maltose or arabinoxylan as a carbon source. Cyan data points represent upregulated CAZymes with potential activity towards arabinoxylan. Dashed lines delineate the fold change cutoff (1.5-fold). (G and H) Epithelial tuft cell (G) and lamina propria Th2 (H) frequency in the distal SI of mice colonized with Tmu or no protist (Ctrl) and fed complex or def-CI chow for 3 weeks. (I) Tmu abundance in the distal SI of mice fed complex chow and def-CI chow for 3 weeks. Data is plotted as mean with SD (A and E). Each symbol represents an individual mouse from two or three pooled experiments (C, D, G, H, and I). *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001, NS, not significant by Mann-Whitney test (D, I) or Student’s t test (C, E, G, H).

To determine whether Tmu can ferment other dietary MACs, we tested a wider array of fermentable fibers as the carbon source in Tmu cultures. While Tmu failed to grow in maltose-free PBF medium supplemented with the fibers arabinan, arabinogalactan, and fructooligosacharides (FOS), the protist readily grew on arabinoxylan, galactomannan, and pectin (Figure 7E and S7A). To identify CAZymes responsible for fiber utilization by Tmu, we performed transcriptomics on Tmu cultured with either the simple sugar maltose or the fermentable fiber arabinoxylan (Figure 7F). We identified 3 CAZymes in GH families associated with fiber utilization that increased expression during growth on arabinoxylan, suggesting these CAZymes break down fiber polymers27,43.

Finally, we wondered whether diet and Tmu metabolic input would affect immune induction by the protist. When Tmu-colonized mice were fed def-C chow, and thus protists were largely depleted from the intestine, type 2 immune induction was ablated (Figure S7B and S7C). However, when Tmu-colonized mice were fed def-CI chow, and thus Tmu fermented mucus glycans, type 2 immune induction in the distal SI still occurred but was largely suppressed (Figure 7G and 7H). This suppression did not appear to be due to decreased succinate output by Tmu on a per-cell basis during mucus feeding, as Tmu grown on mucus in vitro showed no decrease in succinate excretion (Figure S7D). However, Tmu abundance in the distal SI of mice fed def-CI chow was substantially lower than in mice fed complex chow, suggesting that when fermenting mucus, this protist cannot colonize the SI at sufficiently high levels to induce type 2 immunity (Figure 7I). Altogether, these results demonstrate that alteration of dietary fiber intake can induce graded type 2 immune responses by Tmu.

Discussion

The role of the eukaryotic microbiome, and commensal protists in particular, in shaping community structure and influencing host physiology is far less understood than their bacterial counterparts. This study reveals previously unrecognized phylogenetic diversity of commensal protists in the Parabasalia phylum in both mice and humans. Amongst the human-associated parabasalid discovered here are close relatives of the murine species, Tmu and Tc. Although the species found in humans are distinct from the murine isolates, they reinforce the potential translational impact of functional studies using Tmu and Tc. We demonstrate numerous shared features between parabasalids, but importantly, our results also revealed that even minor phylogenetic differences can have meaningful biological consequences.

Although Tmu and Tc are closely related species, they differ in the excretion of the fermentative waste product succinate and prefer distinct nutritional niches within the gut ecosystem. These metabolic differences lead to divergent small intestinal immune responses, distinct trans-kingdom interactions, and differential reliance on host dietary fiber. Succinate induced type 2 immunity in the SI has been a ubiquitous feature of previously characterized commensal tritrichomonads19–21, but Tc demonstrates that this is not universal. Additionally, all commensal parabasalids are assumed to ferment dietary fiber, but Tmu and Tc deviate in dietary fiber usage, leading to trans-kingdom competition with fiber or mucus digesting bacteria, respectively. However, comparing Tmu and Tc revealed unanticipated similarities as well. Tc increases Th1 and Th17 cells in the distal SI, whereas Tmu initiates type 2 immunity by stimulating tuft cells with succinate. However, Tmu colonization of mice lacking the tuft cell response to this metabolite instead exhibited a Th1 and Th17 response in the SI comparable to Tc. This result suggests both protists have the capacity to stimulate Th1 and Th17 immunity in the small intestine. Additional studies will be required to identify potential shared factor(s) that promote this immune response and determine the extent of its conservation in the Parabasalia phylum.

Our studies generated tools and datasets for commensal tritrichomonads, which will eliminate critical barriers that have stymied mechanistic studies of these protists. The genomes of Tmu and Tc combined with metabolomic and transcriptomic datasets form a valuable foundation for future studies. Furthermore, the ability to grow these tritrichomonads in culture is an essential step for microbiological investigations. Previous studies, including our own, isolated tritrichomonads from mice but the protists did not grow robustly in axenic in vitro culture15,19–21. The playbook for culturing an unculturable microbe involves supplementing the medium with complex additives. However, we used the opposite approach and substituted the complex additive serum with a defined lipid supplement to grow Tmu in vitro. Estimates suggest that more than 50% of bacterial species in the microbiome cannot be cultured52,53. Serum and other undefined additives are also standard components of bacterial media, and this approach may facilitate the growth of other unculturable microbiota members.

Only two species of commensal parabasalid, D. fragilis and P. hominis, have been identified in the human gut. Previous studies also suggested industrialized microbiomes have decreased microeukaryotic prevalence17,18. Here, we identified multiple human-associated commensal parabasalids, which were primarily found in the stool of individuals from non-industrialized populations. These parabasalids further emphasize the need to consider the microbiome of diverse human populations and highlight the importance of understanding how different parabasalids influence human health. Our discovery that parabasalid production of the immunomodulatory metabolites succinate and lactate can be predicted based solely on phylogeny is a powerful tool. For example, this model predicts that D. fragilis and the human-associated tritrichomonads discovered here produce succinate, and therefore may stimulate type 2 immunity in the small intestine. However, further work is required to refine this predictive model to account for alternative metabolic mechanisms, including those that may limit succinate excretion in protists like Tc.

Limitations of the study

An important limitation of this study is that our identification of parabasalids in human microbiomes likely includes a high rate of false negativity. Despite the high sequencing depth in some of the metagenomic datasets, read depth was low for parabasalid ITS sequences in most samples. Thus, the prevalence of human-associated parabasalids identified here likely underestimates the true prevalence. Parabasalid-specific approaches will help to circumvent this issue in future studies. A second limitation of this study is that our predictive framework for fermentative pathways in parabasalids only allows for prediction of utilization of a pathway for redox homeostasis, and not excretion of the metabolite. Our discovery that Tc produces succinate but does not excrete enough of this metabolite to stimulate type 2 immunity highlights the importance of this distinction. Identifying the genetic basis of the metabolic mechanism underlying this distinction could facilitate the prediction of excretion based solely on genomic data.

STAR METHODS

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents may be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Michael Howitt (mhowitt@stanford.edu).

Materials availability

Mouse and microbial strains used in this study will be made available upon request addressed to the lead contact.

Data and code availability

Raw sequencing files and genome assemblies have been deposited at Stanford Digital Repository and are publicly available as of the date of publication (links to each dataset can be found in Key Resources Table). Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Purified Rat anti-mouse CD16/CD32 (Clone 93) | BioLegend | Cat# 101302; RRID AB_312801 |

| PacBlue Rat anti-mouse CD45 (Clone 30-F11) | BioLegend | Cat# 103126; RRID AB_493535 |

| PE/Cyanine7 Rat anti-mouse CD326 (Ep-CAM) (Clone G8.8) | BioLegend | Cat# 118216; RRID AB_1236471 |

| AlexaFluor 647 Rat anti-mouse Siglec-F (Clone E50-2440) | BD Biosciences | Cat# 562680; RRID AB_2687570 |

| AlexaFluor 647 Rat IgG2α,κ Isotype Control (Clone R35-95) | BD Biosciences | Cat# 557690; RRID AB_396799 |

| FITC anti-mouse CD4 antibody (Clone GK1.5) | BioLegend | Cat #100405 AB_312690 |

| PerCP/Cy5.5 anti-mouse CD3 (Clone 17A2) | BioLegend | Cat #100217 RRID AB_1595597 |

| PerCP/Cy5.5 anti-mouse CD127 (Clone A7R34) | BioLegend | Cat # 135021 |

| PE/Cy7-conjugated anti-mouse KLRG1 (Clone PK136) | BioLegend | Cat #138425 |

| PE-conjugated anti-human CD4 (Clone RPA-T4) | BioLegend | Cat #300507 |

| FITC-conjugated anti-mouse NK1.1 (Clone PK136) | BioLegend | Cat #108705 |

| FITC-conjugated anti-mouse CD19 (Clone 6D5) | BioLegend | Cat #115505 |

| FITC-conjugated anti-mouse CD8 (Clone 53-6.7) | BioLegend | Cat #100705 |

| FITC-conjugated anti-mouse CD64 (Clone S18017D) | BioLegend | Cat #161007 |

| FITC-conjugated anti-mouse CD11b (Clone M1/70) | BioLegend | Cat #101205 |

| FITC-conjugated anti-mouse TER119 (Clone TER-119) | BioLegend | Cat #116205 |

| Alexa647-conjugated anti-mouse GATA3 (Clone L50 823) | BD | Cat #560068 |

| Alexa647-conjugated anti-mouse FOXP3 (Clone MF-14) | BioLegend | Cat #126407 |

| APC rat anti-mouse IFNγ (clone XMG1.2) | eBioscience | Cat #17-7311-81 |

| PE anti-mouse IL17A (clone eBio17B7) | eBioscience | Cat #12-7177-81 |

| AlexaFluor 647 anti-mouse GATA3 (clone L50 823) | BD Biosciences | Cat #560068 |

| Rat IgG2a kappa isotype control, PE (clone eBR2a) | eBioscience | Cat #12432180 |

| Rat IgG1 kappa isotype control, APC (clone eBRG1) | eBioscience | Cat #17430181 |

| Rabbit anti-DCLK1 | Abcam | Cat# ab37994; RRID: AB_873538 |

| Mouse anti-E-Cadherin (Clone 36/E-Cadherin) | BD Biosciences | Cat# 610181; RRID: AB_397580 |

| IRDye® 800CW Goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) | LI-COR Biosciences | Cat# 926-32211; RRID: AB_621843 |

| Rhodamine-labeled Ulex Europaeus Agglutinin I (UEA I) | Vector Laboratories | Cat# RL-1062 |

| Rabbit anti-Tritrichomonas musculis polyclonal antibody | Rockland Immunochemicals, Inc. (this study) | |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| BBL Biosate Peptone | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat #B11862 |

| D-Maltose monohydrate | Fisher Scientific | Cat #BP684-500 |

| Sodium Chloride | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #S9888 |

| L-Cysteine hydrochloride, anhydrous | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #C1276 |

| Potassium phosphate, dibasic | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #P3786 |

| Potassium phosphate monobasic | Sigma-aldrich | Cat #P5655 |

| L-Ascorbic acid | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #A92902 |

| Ammonium iron(II) sulfate, hexahydrate | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# 215406 |

| Penicillin-Streptomycin | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat# 15140122 |

| Amphotericin B solution | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# A2942 |

| Diamond Vitamin Tween 80 Solution | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# 58980C |

| AlbuMAX I Lipid-Rich BSA | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 11020021 |

| Oleic acid | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# 364525 |

| Cholesterol | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# C8667 |

| Murashige and Skoog basal salt | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# M0529 |

| Bovine Serum, heat inactivated | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 26-170-043 |

| Amphotericin B powder | Alfa Aesar | Cat# J61491-03 |

| Vancomycin hydrochloride | Alfa Aesar | Cat# J62790-06 |

| Ampicillin sodium salt | Alfa Aesar | Cat# J63807-09 |

| Neomycin trisulfate salt hydrate | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# N1876 |

| Percoll | Cytiva | Cat# 17-0891-01 |

| Mucin from porcine stomach, type III | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# M1778 |

| Inulin from chicory | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# 12255 |

| Arabinan (sugar beet) | Megazyme | Cat# P-ARAB |

| Arabinogalactan (larch wood) | Megazyme | Cat# P-ARGAL |

| Arabinoxylan (wheat flour, low viscosity) | Megazyme | Cat# P-WAXYL |

| Galactomannan (carob, low viscosity) | Megazyme | Cat# P-GALML |

| Pectin from apple | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# 93854 |

| Fructooligosaccharides (FOS) from chicory | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# F8052 |

| Paraformaldehyde | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# P6148-500G |

| VECTASHIELD Antifade Mounting Medium | Vector Laboratories | Cat# H-1000-10 |

| DAPI (4’, 6-Diamidino-2-Phenylindole, Dilactate) | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# 10236276001 |

| Histo-Clear | National Diagnostics | Cat# HS-200 |

| Bovine Serum Albumin | Fisher Scientific | Cat# BP1600-100 |

| Normal goat serum | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 50062Z |

| Saponin | Millipore Sigma | Cat# 588255 |

| Triton X-100 | Fisher Scientific | Cat# BP151 |

| HEPES | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# H3375 |

| EDTA 0.5M Solution, pH 8.0 | Research Products International | Cat# E14000 |

| Dispase | StemCell Technologies | Cat# 07913 |

| Deoxyribonuclease I, bovine pancreas | Alfa Aesar | Cat# J62229-MC |

| Propidium iodide | BioLegend | Cat# 421301 |

| Sodium chloride | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# S9888 |

| Succinic acid disodium salt | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# 224731 |

| QIAzol Lysis Reagent | Qiagen | Cat# 79306 |

| PowerUp SYBR Green Master Mix | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# A25777 |

| BD GolgiPlug (containing Brefeldin A) | BD Biosciences | Cat# 555029 |

| Foxp3/Transcription factor staining buffer set | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 00-5523-00 |

| Collagenase A, from Clostridium | Sigma Aldrich | Cat# 10103578001 |

| Methacarn fixative | Fisher Scientific | Cat# NC0547175 |

| Sodium dodecyl sulfate | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# 71736 |

| Monarch RNase A | New England Biolabs | Cat# T3018 |

| Phenol:Chloroform:Isoamyl alcohol | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 15-593-031 |

| Proteinase K | Qiagen | Cat# 19131 |

| Vacuum Grease | Dow Corning | Cat# 1597418 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| DNeasy PowerSoil Pro Kit | Qiagen | Cat# 47016 |

| TURBO DNA-free Kit | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat# AM1907 |

| Direct-zol RNA Miniprep kit | Zymo Research | Cat# R2050 |

| KAPA Stranded RNA-Seq Kit | Roche | KK8400 |

| Deposited data | ||

| Raw sequencing data (Tmu distal SI) | This paper | https://purl.stanford.edu/hk632xt6449 |

| Raw sequencing data (Tmu cecum) | This paper | https://purl.stanford.edu/jv169bq2041 |

| Raw sequencing data (Tc distal SI) | This paper | https://purl.stanford.edu/bz204zx2289 |

| Raw sequencing data (Tc cecum) | This paper | https://purl.stanford.edu/yc907qm9119 |

| Raw sequencing data (Tmu PBF maltose) | This paper | https://purl.stanford.edu/mn686yr7047 |

| Raw sequencing data (Tmu PBF mucus) | This paper | https://purl.stanford.edu/dv208bv2737 |

| Raw sequencing data (Tmu PBF wax) | This paper | https://purl.stanford.edu/fn865fy8284 |

| T. musculis genome assembly | This paper | https://purl.stanford.edu/ht207tk9988 |

| T. casperi genome assembly | This paper | https://purl.stanford.edu/yc907qm9119 |

| Raw sequencing data (16S) | This paper | https://purl.stanford.edu/gh231tz1328 |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| C57BL/6J wild-type mice | Jackson Laboratory | Stock#: 000664 |

| C57BL/6J Gpr91−/− mice | Amgen | N/A |

| C57BL/6J SMART13 mice | PMID 22138715 | N/A |

| B6N.129S2-Casp1tm1Flv/J | Jackson Laboratory | Stock#: 016621 |

| Tritrichomonas musculis mEG2 | Howitt et al. (2016) | |

| Tritrichomonas casperi cEG1 | This study | |

| Pentatrichomonas hominis Hs-3:NIH | ATCC | Cat# 30000 |

| Monocercomonas colubrorum | ATCC | Cat# 50210 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Parabasalid PCR (forward): CCACGGGTAGCAGCA | This study | |

| Parabasalid PCR (reverse): GGCAGGGACGTATTCAA | This study | |

| Bacteria qPCR (forward): AAACTCAAAKGAATTGACG | Yu-Wen Yang et al 2015 | |

| Bacteria qPCR (reverse): CTCACRRCACGAGCTGAC | Yu-Wen Yang et al 2015 | |

| Bacteroidetes qPCR (forward): GTTTAATTCGATGATACGCGAG | Yu-Wen Yang et al 2015 | |

| Bacteroidetes qPCR (reverse): TTAASCCGACACCTCACGG | Yu-Wen Yang et al 2015 | |

| A. muciniphila qPCR (forward): CAGCACGTGAAGGTGGGGAC | Schneeberger et al, 2015 | |

| A. muciniphila qPCR (reverse): CCTTGCGGTTGGCTTCAGAT | Schneeberger et al, 2015 | |

| T. musculis qPCR (forward): GCTTTTGCAAGCTAGGTCCC | Howitt et al, 2016 | |

| T. musculis qPCR (reverse): TTTCTGATGGGGCGTACCAC | Howitt et al, 2016 | |

| T. casperi qPCR (forward): AGGTTACTGAATCATACATGCGT | This study | |

| T. casperi qPCR (reverse): GCAGGAGTTGCTTTCATTGTG | This study | |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| GraphPad Prism 9 | GraphPad | https://www.graphpad.com/ |

| ImageJ | NIH | https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/ |

| R Version 4.1.2 | The R Foundation | https://www.r-project.org/ |

| QIIME | Caporaso et al, 2010 | http://qiime.org/ |

| Trimmomatic | Bolger et al, 2014 | http://www.usadellab.org/cms/?page=trimmomatic |

| Burrows-Wheeler Aligner | Li, Durbin, 2009 | https://github.com/lh3/bwa |

| Samtools | Danecek et al, 2021 | http://www.htslib.org/ |

| featureCounts | Liao et al, 2014 | http://subread.sourceforge.net/ |

| DESeq2 | Anders and Huber, 2010 | https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/DESeq2.html |

| dbCAN2 | Zhang et al, 2018 | https://bcb.unl.edu/dbCAN2/ |

| Phylogeny.fr | Lemoine et al, 2019 | https://ngphylogeny.fr/about |

| LEfSe | Segata et al, 2011 | https://huttenhower.sph.harvard.edu/lefse/ |

| Flye | Kolmogorov et al, 2019 | https://github.com/fenderglass/Flye |

| Bowtie2 | Langmead and Salzberg, 2012 | http://bowtie-bio.sourceforge.net/bowtie2/index.shtml |

| MetaEuk | Karin et al, 2010 | https://github.com/soedinglab/metaeuk |

| BUSCO | Manni et al, 2021 | https://busco.ezlab.org/ |

| DNAPlotter | Carver et al, 2009 | https://www.sanger.ac.uk/tool/dnaplotter/ |

| Other | ||

| Defined mouse chow, containing inulin and cellulose |

Schneider et al, 2018 Research Diets, Inc |

D11112201 |

| Inulin mouse chow |

Schneider et al, 2018 Research Diets, Inc |

D11112226 |

| Cellulose mouse chow |

Schneider et al, 2018 Research Diets, Inc |

D17030102 |

| No fiber mouse chow |

Schneider et al, 2018 Research Diets, Inc |

D11112229 |

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND STUDY PARTICPANT DETAILS

Animals

C57BL/6 WT and Caspase1−/− mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory. Mice from Jackson Laboratory are protist-negative, as verified by PCR on the stool and examination of cecal contents. Tprm5−/− and Gpr91−/− mice were generously provided by Dr. Robert Margolskee and Amgen, respectively, under materials transfer agreements. The IL13 reporter mouse line (SMART13 mice)54 were generously provided by Dr. Jakob von Moltke. All mice were used at 6–12 weeks of age. Experiments were performed using age and sex matched groups. All animal procedures used in this study were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at Stanford School of Medicine.

All mice were housed in individually ventilated cage systems and maintained at specific pathogen free (SPF) health status, unless stated otherwise. Colonies of protist-negative and protist-colonized mice were maintained and handled separately. Protist colonization status was routinely verified by PCR on stool and examination of cecal contents by light microscopy. Cage bottoms were covered with autoclaved bedding and enrichment material. Mice were handled within HEPA filtered air exchange stations, and all surfaces and tools were sanitized using Virkon™ S disinfectant before and after handling. All cage changes were performed by lab staff, who were required to wear personal protection equipment (lab coats, gloves, disposable sleeves) to handle mice used in this study.

Custom diets for in vivo fiber experiments were obtained from Research Diets, Inc. The diets were the same as those used previously21, with diet IDs D11112201 (Defined chow with cellulose and inulin), D11112229 (no fiber), D17030102 (cellulose), D11112226 (inulin). For antibiotic treatment experiments, mice were given antibiotics in the drinking water, which was changed every 3 days. Antibiotics and concentrations used were: vancomycin (0.5g/mL), neomycin (1g/mL), ampicillin (1g/mL). For succinate treatment, disodium succinate (100mM) was added to the drinking water and changed every 3 days.

METHOD DETAILS

Identification of protists in mouse stool

Mice at Stanford University animal facilities were screened for commensal protists by extracting DNA from stool using the DNeasy Powersoil Pro Kit (Qiagen) according to manufacturer instructions. Samples were then used as input for PCR using pan-parabasalid primers (forward: 5’-CCACGGGTAGCAGCA-3’, reverse: 5’-GGCAGGGACGTATTCAA-3’). These primers generate an approximately 1.1kb amplicon of the parabasalid internally transcribed spacer (ITS) sequence, which was sequenced by Sanger Sequencing for phylogenetic classification. Phylograms were generated using MAFFT55.

Isolation of Tritrichomonas spp. from mice

Protists were purified as described previously19, with modifications. Briefly, cecal contents were harvested from WT C57BL/6 mice and passed over a 40μm strainer. Contents were then washed three times in PBS and purified at the interface of a 40%/80% Percoll (GE healthcare) gradient, after centrifugation at 1000xg for 10minutes with no brake. The number of viable protists was quantified using a hemocytometer, and 1×106 trophozoites were inoculated per mL of PBF growth medium (recipe below). The PBF medium was supplemented with 1x Penicillin/Streptomycin (Caisson Labs), 2.5μg/mL Amphotericin B (Sigma Aldrich), 100μg/mL Vancomycin (Alfa Aesar), 12.5μg/mL Chloramphenicol (Sigma). Protists were then cultured overnight in an anaerobic chamber (Coy Labs) at 37°C.

Colonization of mice with protists

Mice were colonized with commensal parabasalid protists as described previously19 with slight modifications. Briefly, protists were resuspended in PBS and mice were colonized with 1×105 protists per mouse by oral feeding. Colonization was verified after 7 days by qPCR on the stool using Tmu or Tc specific primers. For Tc colonization of mice, protists were isolated directly from mouse ceca one day prior to colonization. For Tmu colonization of mice, protists were cultured in vitro for no more than 20 passages prior to colonization of mice.

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

SEM was performed on Tmu and Tc as described previously19. Briefly, protists were isolated from the ceca of SPF mice as described above and adhered to poly-lysine coated coverslips. Samples were then fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1M cacodylate pH 7.2. Samples were then rinsed and post-fixed for 30min in 1% OsO4 in 0.1M cacodylate buffer and dehydrated in a graded series of ethanol prior to critical point drying with liquid CO2. Protists were then sputter-coated with 5nm platinum and examined with a Zeiss Sigma scanning electron microscope.

Collating previously published human gut metagenomic samples

Prevalence of parabasalid species across lifestyle was characterized using a curated collection of 1,800 metagenomes including samples from “industrial”, “transitional” and “hunter-gatherer” populations that were reported previously28. Due to the sensitivity of this analysis to read depth, we removed studies that had a median read depth lower than 5 giga base pairs.

Discovery of previously undescribed parabasalid ITS sequences

We compiled a set of Parabasalid internal transcribed spacer (ITS) sequences derived in this study or from public databases. We used these sequences as “bait” to mine for previously undescribed ITS sequences in the contigs of metagenome assemblies of samples derived from Tanzania, Nepal or California28. The comparison between bait and assembly contigs was performed by mashmap56. A phylogenetic tree of these ITS sequences, along with our bait ITS sequences, was created using FastTree57.

Species prevalence analysis

All reads were mapped against a database of Parabasalid ITS sequences derived in this study or from public databases (Bowtie2)58. Resulting mappings were processed using inStrain profile (v1.2.14)59 and CoverM v0.4.0 (https://github.com/wwood/CoverM). Species with more than one read aligning to the ITS sequence at a breadth greater than 20% were considered present and prevalence was calculated as the percentage of metagenomes in which the species was present.

High molecular weight DNA extraction and Nanopore Sequencing

To obtain pure protist DNA for genome sequencing, Tc-colonized mice were treated with an antibiotic and antifungal cocktail in the drinking water (0.5g/L Vancomycin, 1g/L Neomycin, 1g/L Ampicillin, 0.2g/L Amphotericin B) for 6 days. Tc was then purified from the cecal contents as described above, with the modification of two rounds of Percoll purification, instead of one. For Tmu, protists were instead axenically cultured. High molecular weight DNA from each protist was then isolated by gently resuspending pelleted protists in lysis buffer (PBS+0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate), using a wide-bore pipet tip. Lysed cells were transferred to DNA LoBind tubes (Eppendorf) and incubated with Monarch RNase A (NEB) for 2 hours at 37°C. Next, Proteinase K (Qiagen) was added, and samples were incubated for 2 hours at 50°C. Nucleic acid was then isolated using two rounds of extraction with Phenol:Chloroform:Isoamyl alcohol (Sigma). To avoid pipetting during transfer steps, vacuum grease (Dow Corning) was added as a phase-lock gel. Protein contaminants were then precipitated using 2M Ammonium Acetate, and then DNA was precipitated overnight in ethanol. Next, DNA was pelleted by centrifugation at 8000xg, and DNA pellets were washed three times with 70% ethanol. DNA was then resuspended in water and used for library preparation and sequencing using the Nanopore Ligation Sequencing Kit and Minion Flow Cell (Oxford Nanopore).

Genome assembly and annotation

Genome assemblies for both T. casperi and T. musculis were constructed using Flye60, v. 2.9-b1768 with default parameters. Short read libraries were then mapped against the genome assemblies with Bowtie258, v. 2.4.4 and resulting alignments were used for assembly polishing with pilon61. Genes were predicted with MetaEuk62, v. 5.34c21f2 with Uniref90 as the reference protein dataset. Genome completeness was assessed with BUSCO63, v5.0.0 in protein mode with Eukaryota ODB10 lineage marker gene set. Genome diagrams were generated using DNAPlotter64, v. 18.2.0.

RNA-Sequencing

RNA-Sequencing was performed on Tmu and Tc in vivo by first isolating the luminal contents from the distal small intestine and cecum of 3 mice per group. Contents were strained over 40μm filters, then washed with ice-cold PBS to remove debris. To minimize potential for sample processing to affect transcriptomes, samples were then immediately resuspended in Qiazol (Qiagen). RNA was purified using the Direct-zol RNA Miniprep kit (Zymo Research). RNA-Seq libraries were then generated using the KAPA Stranded RNA-Seq kit with poly-dT enrichment of mRNA transcripts, and libraries were sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq instrument.

Transcriptomics on the in vitro grown Tmu samples was performed on protists grown for 3 days in the condition of interest. Cultures (3 biological replicates per condition) were pelleted at 700xg for 5min at 4°, then resuspended in Qiazol. RNA was then isolated using the Direct-zol RNA Miniprep kit (Zymo Research), as above. Library preparation and sequencing was performed at Azenta Life Sciences (South Plainfield, NJ). Libraries were constructed using the TruSeq Stranded mRNA kit (Illumina), with poly-dT enrichment of mRNA transcripts. Samples were sequenced on a HiSeq instrument (Illumina).

Analysis of all transcriptomics datasets was performed using alignment-based analysis, using the Tmu and Tc genomes. Briefly, Illumina adapters were trimmed and low-quality sequence was removed using Trimmomatic65. Reads were then aligned to the respective genome using Burrows Wheeler Aligner66. Samtools67 was used to convert corresponding files to binary alignment and map (bam) files and sort the reads by position. Next, featureCounts68 was used to quantify read depth of each genome feature. Differential expression analysis was performed using DESeq269.

Protist enumeration

Enumeration of protists from the small intestinal tissue was performed as described previously19, with modifications. Briefly, the distal 10cm of small intestine was removed and flushed with ice-cold sterile PBS using a 19-gauge feeding needle. The contents were then pelleted and the supernatant was aspirated. Genomic DNA was isolated using the Powersoil Pro Kit (Qiagen) according to manufacturer instructions. To detect and enumerate protists, quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed using PowerUp SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). For T. musculis, the following primers specific to the 28S rRNA gene were used: 5’-GCTTTTGCAAGCTAGGTCCC-3’and 5’-TTTCTGATGGGGCGTACCAC-3’19. For T. casperi detection, primers were designed that specifically recognized this protist: 5’-AGGTTACTGAATCATACATGCGT-3’ and 5’-GCAGGAGTTGCTTTCATTGTG-3’. qPCRs were run on a QuantStudio 3 Real Time PCR instrument (Thermo Fisher). To convert qPCR values into protist numbers, protists were isolated and counted using a hemocytometer before extracting genomic DNA and analyzing a dilution series by qPCR. These results were used to create a standard curve, and regression analysis was used to convert Ct values to protist numbers, as has been described previously15,19.

Quantification of protists in the stool was performed similarly. Stool pellets were collected from mice and weighed. A fraction of the stool was dried and used to calculate the water content of the stool, while the rest was used for DNA extraction. Quantification was performed using the same qPCR primers as above. Protists were quantified in the cecum by weighing the cecal luminal contents, then resuspending in PBS. Live trophozoites were then counted using a hemocytometer and normalized to cecal weight.

Isolation of Epithelial Cells for Flow Cytometry

Ileal epithelial cells were isolated as described previously19. Briefly, the terminal 10cm of the small intestine was removed and trimmed of fat. Luminal contents were gently flushed with 10mL of ice-cold PBS, then the tissue was opened longitudinally. Peyer’s Patches were removed and the tissue was incubated on ice in PBS, 5mM HEPES pH 7.4, 2% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (iFBS), 1mM DTT. Tissue was then transferred to pre-warmed PBS, 5mM HEPES, 2% iFBS, 5mM EDTA and shaken at 200rpm for 15 minutes at 37°, followed by vigorous shaking. This was repeated and epithelial cells from both fractions were combined and washed with PBS. Tissue was then digested in DMEM containing 10% iFBS, 0.5U/mL Dispase II (StemCell Technologies), 50μg/mL DNase (Roche) for 10 minutes at 37°C. The cells were then filtered over 40μm strainers and washed with PBS, 2% iFBS, 1mM EDTA. Cells were then incubated for 10 minutes with anti-CD16/CD32 (clone 93, Biolegend) and then stained with the following antibodies: PacBlue-conjugated anti-CD45 (clone 30-F11, Biolegend), PE/Cy7-conjugated anti-EpCam (clone G8.8, Biolegend), and Alex647-conjugated anti-SiglecF (clone E50–2440, BD Biosciences). Cell viability was assessed by propidium iodide staining (Biolegend). Cells were then analyzed on a BD FACSCanto II.

Lamina propria cell isolation and flow cytometry