Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate the feasibility and efficacy of patient-directed behavioral-physical intervention (BPI) for acute hiccups after chemotherapy in cancer patients.

Methods

In this prospective randomized controlled trial, cancer patients scheduled for chemotherapy were randomized into the BPI group and the control group. Patients in the BPI group were provided the Hiccup Knowledge Manual and instructional videos on six non-pharmacological behavioral-physical interventions for hiccups and were encouraged to use the interventions when they experienced acute chemotherapy-induced hiccups (CIH). The control group received routine medical attention. The primary endpoint was the median time to acute hiccup remission. The secondary endpoint was the incidence of anxiety and depression in patients and their family caregivers.

Results

A total of 654 patients scheduled to receive chemotherapy were enrolled and randomly assigned (1:1) to the BPI group or the control group. After chemotherapy, 57 patients in the BPI group and 49 patients in the control group experienced acute hiccups. The median acute hiccup remission time was significantly shorter in the BPI group [0.17 h (95% CI 0.13 to 0.21 h)] than that in the control group [3.00 h (95% CI 1.48 to 4.52 h)] (P < 0.01). The mean anxiety and depression scores of patients were significantly lower in the BPI group than that in the control group (7.21 vs. 9.86, P < 0.01; 7.40 vs. 10.27, P < 0.01, respectively). Similarly, the average anxiety and depression scores of family caregivers were significantly lower in the BPI group than in the control group (3.91 vs. 8.31, P < 0.01; 4.30 vs. 8.90, P < 0.01, respectively).

Conclusion

Learning and self-directed implementation of behavioral-physical interventions have potential effects in shortening the median time to remission of acute CIH. It may also reduce anxiety and depression in patients and their family caregivers. Due to the limitations of this preliminary study, further research is warranted.

Trial registration

The study complied with relevant Chinese laws, rules, and regulations (Measures for the Ethical Review of Biomedical Research Involving Humans, etc.), as well as the WMA Declaration of Helsinki and the CIOMS International Ethics Guidelines for Human Biomedical Research, and followed the protocol approved by the medical ethics committee and the informed consent form to carry out clinical trials (research) to protect the health and rights of subjects. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shangjin Nanfu Hospital West China Hospital and was registered in the World Health Organization (WHO) international clinical trials registered organization registered platform (https://www.chictr.org.cn; ChiCTR2400081049; February 21, 2024).

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00520-025-09758-2.

Keywords: Non-pharmacological interventions, Behavioral-physical intervention, Cancer, Chemotherapy, Acute hiccups

Introduction

Chemotherapy remains an important approach in cancer treatment, and hiccups are a common and clinically significant complication. However, they are often underestimated or underrecognized [1]. Studies have shown that the incidence of hiccups after chemotherapy ranges from approximately 30–54% in patients with different cancer types or treatment regimens [2–6]. This symptom not only affects patients’ quality of life but may also interfere with the treatment process in some cases [7, 8]. Chemotherapy-associated hiccups can be classified as acute (lasting less than 48 h), persistent (lasting more than 48 h but less than a month), or refractory (lasting more than a month), with acute hiccups being particularly bothersome [9]. One study also indicates that hiccups may occur outside the typical risk window, potentially affecting patients in the long term [10].

Currently, clinical interventions for acute hiccups in patients undergoing chemotherapy fall into two main categories: non-pharmacological and pharmacological treatments [11]. Non-pharmacological interventions are usually based on physical mechanisms or traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) theories, aiming to relieve symptoms by stimulating specific nerves or muscle groups [12–15]. In contrast, pharmacological treatments primarily act by modulating neurotransmitter levels or altering gastrointestinal motility [16, 17]. Systematic reviews and expert consensus recommend initiating management with non-pharmacological treatments for acute hiccups [18, 19], escalating to pharmacological options if necessary. Despite the variety of available therapies, many are not consistently effective. Some pharmacological agents have notable side effects, limiting their use in vulnerable populations, such as chemotherapy patients [19]. Moreover, there is a lack of high-quality clinical studies to support evidence-based recommendations [20].

In recent years, non-pharmacological behavioral-physical interventions have drawn growing attention for their potential to alleviate acute CIH [21, 22]. Preliminary studies have yielded promising results; however, further data are needed to confirm their efficacy and safety. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the feasibility and effectiveness of a patient-directed behavioral-physical intervention model for managing acute hiccups during chemotherapy.

Participants and methods

Study design and participants

In this prospective randomized controlled trial, cancer patients receiving chemotherapy at the Oncology Center of Shangjin Hospital of West China Hospital of Sichuan University were screened for eligibility. Eligible patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to either the BPI group or the control group. Patients in the BPI group received the Hiccup Knowledge Manual and instructional videos and were guided to learn and master six non-pharmacological behavioral-physical interventions for hiccups. They were instructed to apply these interventions independently during an acute episode of hiccups, based on their prior training. The control group received routine medical care, which includes general information about CIH and precautions during treatment, but did not involve any systematic BPI. Caregivers held a conversation with the patient prior to chemotherapy to explain the physiology, common triggers, expected duration, and potential impact of hiccups, in order to help the patient understand the symptoms.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: ① patients with malignant tumors confirmed by pathological examination; ② scheduled to receive chemotherapy; ③ planned to receive standardized prophylaxis for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) prevention; ④ normal cognitive function; ⑤ Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status score of 0–2 and full muscle strength (grade 5); and ⑥ provision of written informed consent.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: ① severe cardiopulmonary insufficiency; ② gastrointestinal bleeding; ③ coagulopathy; ④ unstable brain metastases; ⑤ history of intractable hiccups caused by cerebral infarction, traumatic brain injury, or other conditions; and ⑥ occurrence of hiccups from any cause during the week prior to enrollment.

The removal criteria were as follows: ① non-compliance as determined by the investigator; ② withdrawal of informed consent; and ③ failure to receive chemotherapy for any reason.

Research tools

Hospital information system (HIS) data collection

All clinical and demographic data were collected using the HIS electronic medical record platform. Information included the patient’s name, gender, age, smoking history, alcohol consumption history, family history of cancer, past medical history, whether it was the patient’s first treatment, history of hiccups, physical status score (ECOG = 0–2), pathological diagnosis, tumor staging, treatment regimen, comorbid conditions, and other relevant baseline characteristics. All data were collected immediately after enrollment.

Hiccup Knowledge Manual

The manual covers the following topics: an overview of hiccups, their etiology, clinical features, six different behavioral-physical intervention techniques, prognosis, and prevention [23–25].

A variety of possible effective methods for alleviating hiccups were collected through literature retrieval, Internet search, clinical consultation, and other means. Interventions that required professional operation (such as acupuncture, electronic acupoint stimulation, ear pill acupoint stimulation) were excluded. Finally, six methods that were easy to master and could be operated independently by patients were selected. The specific operation is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

List of six behaviors—physical intervention methods

| Behavior-physical intervention methods | Brief description of the operation method | |

|---|---|---|

| Method 1 | Ear plugging and nasal swallowing | Use the index fingers to completely plug both ears (slightly sealed). Then, use the ring fingers to press the nose on both sides (completely sealed). Finally, close your mouth and swallow approximately 3–5 times |

| Method 2 | Press the Neiguan acupoint | Located on the inner arm near the wrist, two thumb widths above the center of the transverse arch. Press down gently, then heavily, for approximately 10 s |

| Method 3 | Press and accumulate bamboo points | Located at the inner edge of the eyebrows at the depression. Slightly bend the hands, place the index fingers on the forehead, and perform acupressure with the thumbs. The force should be uniform, persistent, and gentle, with sensations of swelling and pain for the best effect. Perform acupressure 3–5 times for 5–10 s each time |

| Method 4 | Take a deep breath and hold it | Lift the chest, take a deep breath in, and hold it. Do not exhale until necessary. Repeat this process 3–5 times |

| Method 5 | Tongue depressor | Use a clean spoon to apply firm pressure to the tongue |

| Method 6 | Drink water and bend over | Take a few sips of warm boiled water then bow by bending over at a 90° angle. Repeat this several times before straightening up |

The learning time for the manual was less than 60 min. All patients in the BPI group completed the training within 1 h, and their understanding was verified by study staff. The accompanying video is 2 min and 54 s and illustrated the six interventions for managing acute hiccups. A Quick Response code for the video was printed on the manual, and patients were encouraged to keep the manual accessible for review. If forgotten, the content could be revisited at any time.

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [26]

This scale was used to assess the patient’s level of anxiety and depression during episodes of hiccup. The HADS comprises 14 items, divided into two subscales: anxiety and depression, with each subscale containing seven items. Each item is rated on a scale from 0 to 3, resulting in a total score range of 0–21. A score > 7 indicates anxiety or depression. Specifically, scores of 8–21 indicate anxiety or depression, while scores of 0–7 suggest no anxiety or depression. Scores of 8–10 indicate mild anxiety or depression, 11–14 denote moderate anxiety or depression, and 15–21 represent severe anxiety or depression.

Statistical methods

This study adopted an open-label, randomized, and controlled trial design. Computer-generated block randomization was used, and the randomization sequence was assigned in real time by an independent statistician using SAS 9.4 software. Group allocations were generated through a centralized randomization system, and neither the researchers nor the participants could predict the assignment results prior to randomization.

Based on preliminary data from the research team, the median time to remission of acute hiccups following chemotherapy was estimated at 2.48 h. The study aimed to achieve a median remission time of 1 h following patient-directed learning of non-pharmacological behavioral-physical interventions. Sample size calculations were performed using d = , taking into account a significance level (α) of 0.05 and a test power (1-) of 0.80 and assuming equal proportional distribution of participants to the two groups (π = 0.5 and = 0.5). The standard normally distributed critical values for the significance level and the test power were determined: = 1.96, = 0.84. The value of stepwise calculating is 2.8. The natural logarithm of the effect size, θR, was log(0.4) ≈ − 0.916. The sample size was calculated as the following: d ≈ 37.4, which would require approximately 38 patients per group. Considering 20% loss to follow-up, the final requirement was approximately 48 patients per group. Given the incidence of acute hiccups after chemotherapy reported in previous studies as approximately 15%–40% [3–6], it was estimated that a total of no less than 640 chemotherapy patients meeting the enrollment criteria would need to be screened.

The primary endpoint was the median time to remission of acute hiccups, defined for each patient as the interval in hours between the first hiccup and the final hiccup. Remission was established by a hiccup-free period of at least 2 h. The secondary endpoint was the incidence of anxiety and depression in patients and their family caregivers.

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Continuous variables were compared using independent sample t-tests, while categorical variables were analyzed using chi-square tests. Survival plots for the duration of the treatment effect were generated using Kaplan–Meier survival analysis. A P-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics

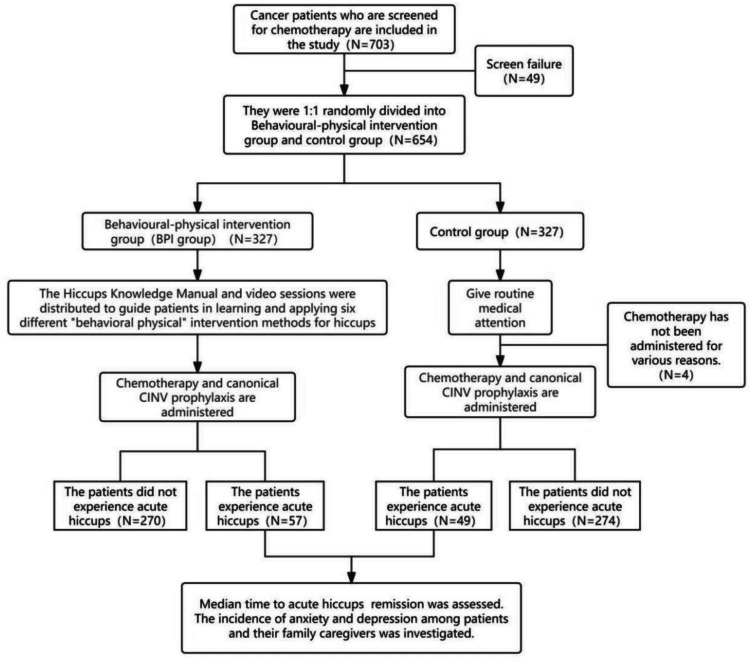

A total of 703 cancer patients scheduled to receive chemotherapy were screened in this study, of which 49 were failed from screening due to the assessment of existing disease, physical reasons, cognitive problems, and poor compliance. The remaining 654 patients who met the inclusion criteria were enrolled in the current study (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The flow of the study

The enrolled patients were 1:1 randomized into the BPI group and the control group. Thus, 327 patients were assigned to the BPI group, of whom 57 (17.4%) experienced acute hiccups. The other 327 patients were assigned to the control group. Four patients were eliminated due to chemotherapy being cancelled. Finally, there were 49 (15.2%) patients who experienced acute hiccups in the control group. The baseline characteristics of the two groups of patients with hiccups are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Baseline in both groups of patients with hiccups

| Characteristics | BPI group (N=57) | Control group (N=49) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age(years), mean (SD) | 60.39(9.16) | 61.49(10.91) | 0.572 |

| Sex, n(%) | 1.000 | ||

| Male | 40(70.20) | 34(69.40) | |

| Female | 17(29.80) | 15(30.60) | |

| Type of cancer, n(%) | 0.233 | ||

| Lung cancer | 27(47.40) | 23(46.90) | |

| Colorectal cancer | 7(12.30) | 8(16.30) | |

| Carcinoma of bile duct | 3(5.30) | 2(4.10) | |

| Ovarian cancer | 4(7.00) | 4(8.20) | |

| Gastric cancer | 4(7.00) | 3(6.10) | |

| Endometrial cancer | 2(3.50) | 1(2.00) | |

| Other | 10(17.50) | 8(16.30) | |

| Stage, n(%) | 0.404 | ||

| I | 6(10.50) | 8(16.30) | |

| II | 18(31.60) | 10(20.40) | |

| III | 10(17.50) | 13(26.50) | |

| IV | 23(40.40) | 18(36.70) | |

| Patients’performance status score (ECOG) | 0.071 | ||

| 0 | 51(89.50) | 37(75.50) | |

| 1 | 6(10.50) | 12(24.50) | |

| History of smoking status, n(%) | 0.433 | ||

| No | 36(63.20) | 27(55.10) | |

| Yes | 21(36.80) | 22(44.90) | |

| History of alcoholism, n(%) | 0.840 | ||

| No | 37(64.90) | 30(61.20) | |

| Yes | 20(35.10) | 19(38.80) | |

| Initial treatment or relapse, n(%) | 0.730 | ||

| No | 53(93.00) | 44(89.80) | |

| Yes | 4(7.00) | 5(10.20) | |

| Combined underlying diseases, n(%) | 0.542 | ||

| No | 36(63.20) | 34(69.40) | |

| Yes | 21(36.80) | 15(30.60) | |

| History of hiccups, n(%) | 0.377 | ||

| No | 41(71.90) | 39(79.60) | |

| Yes | 16(28.10) | 10(20.40) | |

| Treatment regimen, n(%) | 0.377 | ||

| Platinum-based chemotherapy | 44(77.20) | 42(85.70) | |

| Non-platinum chemotherapy | 13(22.80) | 7(14.30) | |

Remark:Platinum-based chemotherapy:Pemetrexed + Carboplatin,Pemetrexed + Cisplatin,Bleomycin + Etoposide + Cisplatin,Etoposide + Cisplatin,Leucovorin)+ 5-FU + Irinotecan + Oxaliplatin, Leucovorin + 5-FU + OXaliplatin,Tegafur/Gimeracil/Oteracil + Oxaliplatin + Paclitaxel,Paclitaxel + Carboplatin,Paclitaxel + Cisplatin,Paclitaxel + Cisplatin + Fluorouracil,Pemetrexed + Leucovorin + 5-FU + Irinotecan + Oxaliplatin,Etoposide + Cisplatin + Fluorouracil,Gemcitabine + Cisplatin,Tegafur + Paclitaxel + Oxaliplatin, Non-platinum chemotherapy:Irinotecan + Leucovorin + Fluorouracil, Irinotecan + Paclitaxel , Paclitaxel , Tegafur/Gimeracil/Oteracil , Pemetrexed , Gemcitabine + Tegafur/Gimeracil/Oteracil

Time to remission of acute hiccups

The median time to remission of acute hiccups in the BPI group was 0.17 h (95% CI 0.13 to 0.21 h), which was significantly shorter than the median time of 3.00 h (95% CI 1.48 to 4.52 h) in the control group (P < 0.01) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Time to acute hiccup remission

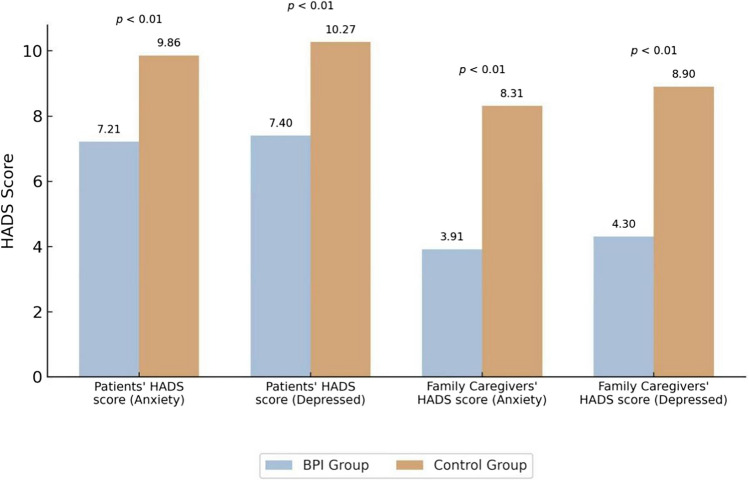

Anxiety and depression in patients and their family caregivers

The mean anxiety and depression scores (HADS) for patients were significantly lower in the BPI group than in the control group (7.21 vs. 9.86, P < 0.01; 7.40 vs. 10.27, P < 0.01, respectively). Similarly, the average anxiety and depression scores for their family caregivers were significantly lower in the BPI group than in the control group (3.91 vs. 8.31, P < 0.01; 4.30 vs. 8.90, P < 0.01, respectively) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Average HADS (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale) score of patients and family caregivers in two groups

Other findings

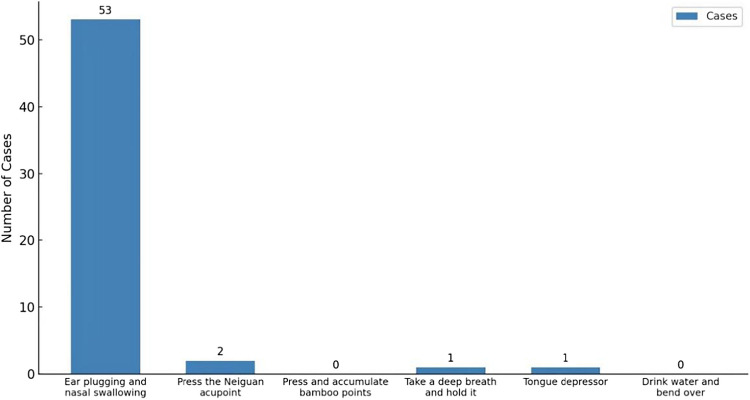

Patients’ preferred intervention as the first attempt

In order to gain a better understanding of patients’ choice of the behavioral-physical interventions, we counted the distribution of the interventions selected for the first time when they encountered acute hiccups. The results showed that the vast majority of participants (94.64%) first chose the ear plugging method and swallowed by nose, while the other methods had a lower preference degree (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Patients’ first preferred intervention method (N = 57)

Relative factor analysis for acute hiccups after chemotherapy

To assess the impact of potential relative factors on the incidence of acute hiccups, we conducted a binary logistic regression analysis. The results indicated that a history of alcohol consumption (P = 0.011, OR = 2.021) was associated with a significant risk of hiccups, approximately doubling the risk for patients without a drinking history. The patients with digestive tract tumors had a significantly lower risk of hiccups (P < 0.001, OR = 0.289). Chemotherapy regimens were also related to the acute hiccups (P < 0.001, OR = 6.429): platinum-based regimens had a 6.4 times higher risk of hiccups compared to those non-platinum regimens. Age, gender, and initial treatment versus re-treatment did not show statistical significance (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis of factors associated with hiccups

| Variable | Odds ratio | P-value | 95% Cl |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age(≥ 50 vs. < 50) | 1.341 | 0.413 | 0.665–2.704 |

| Sex | 1.080 | 0.779 | 0.663–1.842 |

| Initial treatment or relapse | 1.082 | 0.862 | 0.446–2.626 |

| History of alcoholism | 2.021 | 0.011 | 1.173–3.484 |

| Type of cancer (GI vs. non-GI) | 0.289 | < 0.001 | 0.176–0.475 |

| Chemotherapy regimen (platinum vs. non-platinum) | 6.429 | < 0.001 | 3.786–10.919 |

Discussion

The incidence of CIH varies widely, with reported rates ranging from 15 to 40%, depending on tumor type and treatment regimen [3–6]. Cisplatin-containing regimens, in particular, have been associated with hiccups in up to 28.6% of patients [6]. Additionally, while novel drugs like NK1-RAs (neurokinin-1 receptor antagonist) can relieve some chemotherapy-related side effects such as constipation and insomnia, they also introduce new risks, including diarrhea and hiccups [27].While hiccups are typically transient, some patients experience persistent or refractory episodes, which can significantly impact quality of life, causing sleep disturbances, reduced appetite, and difficulty in speaking or social interactions [7, 8]. In severe cases, prolonged hiccups may even necessitate modifications in chemotherapy regimens, highlighting the need for better prevention and management strategies [8].

Furthermore, a prior study indicated that over 20% of cancer patients experience hiccups during chemotherapy, and if poorly controlled, these may persist beyond the acute phase [3, 5]. Certain malignancies appear to have a higher association with hiccups, particularly gastrointestinal and lung cancers, where studies have reported CIH incidences of 54.1% and 31.6%, respectively [2]. Our study further identified key risk factors for CIH, revealing that alcohol consumption, tumor type, and platinum-based chemotherapy significantly influenced hiccups’ occurrence.

The prior study [11] found that patients are willing to learn about hiccups after chemotherapy. Learning seems to reduce the incidence of hiccups, but its primary endpoint is not an efficacy indicator and cannot directly reflect the effect of relieving hiccups. The current study directly assessed the use and efficacy of six non-pharmacological behavioral-physical interventions in hiccups. In contrast, our study design focused more on patient involvement, validated the effect of the pre-learning intervention on hiccup remission, and further explored its effect on the improvement of anxiety and depression levels in patients and their families. Therefore, this study, building on the prior study, provides more direct evidence to support primary research data on the clinical use of non-pharmacological interventions in the management of hiccups.

Non-pharmacological interventions have been increasingly recognized as effective strategies for managing CIH, offering a safe and well-tolerated alternative to pharmacological treatments [28, 29]. Prior studies have demonstrated the efficacy of various behavioral-physical interventions, such as acupuncture, breath-holding, deep breathing exercises, and acupressure, in alleviating hiccups [30–33]. Our study further validated the clinical effectiveness of these interventions, demonstrating that pre-learning and autonomous use of six behavioral-physical methods significantly shortened hiccup duration compared to standard care. Naturally, further research is needed to confirm this hypothesis.

Our previous study found that CINV in patients can significantly increase the risk of anxiety/depression in their family caregivers [34], so we speculate that acute hiccups in patients may also cause psychological problems in their family caregivers. In our study, the intervention group exhibited significantly lower anxiety and depression scores compared to the control group, suggesting that providing patients with the knowledge and tools to manage hiccups not only enhances their confidence but also alleviates psychological stress for both themselves and their caregivers.

Among the six intervention methods, the ear-plugging and nasal-swallowing technique was most frequently chosen by patients, likely due to it being ranked at the top in the manual and video and due to its intuitive ease of use, simplicity, and perceived immediate effect. Since the arrangement order of the six methods is determined by the random method, the method ranked earlier may be adopted in a concentrated manner, thereby affecting the judgment of the effectiveness of other methods. Further investigation is needed to determine whether it offers superior efficacy compared to other options. Understanding patient preferences and clinical effectiveness is essential for developing personalized hiccup management strategies.

The effectiveness of BPI in managing CIH may be attributed to their modulation of autonomic and reflex pathways. Hiccups involve a reflex arc consisting of the afferent, central, and efferent pathways, primarily mediated by the vagus, phrenic, and recurrent laryngeal nerves [35, 36]. Different BPI methods likely target specific neural mechanisms: the ear plugging method and nasal swallowing by nose may stimulate Arnold’s nerve (auricular branch of the vagus nerve), influencing vagal activity and reducing diaphragm spasms; deep breathing exercises may increase CO2 levels, affecting medullary respiratory centers and decreasing phrenic nerve excitability; drinking water and bending over may activate the esophago-pharyngeal reflex, enhancing coordination between the diaphragm and swallowing muscles; acupressure at specific points (e.g., Neiguan P6, Zhuzhu BL2) may regulate the autonomic nervous system via connections between the trigeminal and vagus nerves; and using a tongue depressor may stimulate the glossopharyngeal and recurrent laryngeal nerves, disrupting afferent signaling and transiently inhibiting the hiccup reflex. By enabling patients to intervene early, BPI not only helps suppress the hiccup reflex but may also alleviate anxiety by restoring a sense of control over symptoms.

To optimize individualized hiccup management, future research should consider patient preferences and intervention adherence. Moreover, the potential link between hiccup control and psychological well-being warrants further investigation. Autonomic nervous system regulation and symptom-related stress reduction may play key roles in mediating this relationship. Future studies should focus on clarifying causal pathways between symptom relief and psychological benefits, utilizing longitudinal research and neurophysiological assessments.

As a preliminary interventional study in the field of CIH, this research has several limitations. The study adopted an open-label design, and the primary endpoint was self-reported by patients, making it difficult to implement blinding. These factors may have introduced observer bias and social desirability bias. Additionally, the randomized sequence of intervention methods presented in the manual and instructional video may have led patients to preferentially select certain techniques, potentially affecting the assessment of the overall effectiveness of other methods and the intervention model as a whole. The current findings suggest only that the intervention model may be feasible and potentially effective in alleviating CIH; however, both the model and specific techniques require further validation through more rigorously designed studies. Future research will aim to optimize the study design by introducing appropriate blinding, evaluating each intervention method separately, and incorporating objective monitoring tools such as diaphragmatic electromyography to accurately record hiccup events and assess intervention efficacy.

Conclusions

Learning and self-directed implementation of behavioral-physical interventions have potential effects in shortening the median time to remission of acute CIH. It may also reduce anxiety and depression in patients and their family caregivers. Due to the limitations of this preliminary study, further research is warranted.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Cancer Psychology and Health Management Committee of Sichuan Cancer Society & Cancer Recovery and Palliative Care Committee of Sichuan Anti-cancer Association for their valuable guidance.I am deeply grateful for the help and support I received from many sources during the writing of this article. Special thanks to my colleagues for their valuable comments and suggestions, as well as for every in-depth discussion, which has benefited me a lot. Here, I would like to express my sincerest and deepest gratitude to all those who have given me help and support.

Author contribution

XZL: data curation, formal analysis, investigation, visualization, original draft; LLX: data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, validation; LLY: formal analysis, resources, software; JC: resources, validation; JX: resources, validation; LPT: resources, validation; YMW: resources, validation; YT: resources, project administration, supervision, review and editing, conceptualization;JZ:conceptualization, project administration, resources, supervision, review and editing.

Funding

This research was supported by the Sichuan Provincial Department of Science and Technology (No. 24KJPX0155).

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval

This study has been approved by the Ethics Review Committee of Chengdu Shangjin Nanfu Hospital (Approval No. 2024 (14)).

Consent to participate

All participants provided written informed consent.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Xiaozhen Luo and Lingling Xie are co-first authors.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Yu Tang, Email: 16943897@qq.com.

Jiang Zhu, Email: zhujiang@wchscu.cn.

References

- 1.Ehret CJ, Le-Rademacher JG, Martin N, Jatoi A et al (2024) Dexamethasone and hiccups: a 2000-patient, telephone-based study. BMJ Support Palliat Care 13(e3):e790–e793. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2021-003474 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Hosoya R, Tanaka I, Ishii-Nozawa R, Amino T, Kamata T, Hino S, Kagaya H, Uesawa Y (2018) Risk factors for cancer chemotherapy-induced hiccups (CIH). Pharmacology Pharmacy 9:331–343. 10.4236/pp.2018.98026 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ergen M, Arikan F, Fırat ÇR (2021) Hiccups in cancer patients receiving chemotherapy: a cross-sectional study. J Pain Symptom Manage 62(3):e85–e90. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hendrix K, Wilson D, Kievman MJ, Jatoi A (2019) Perspectives on the medical, quality of life, and economic consequences of hiccups. Curr Oncol Rep 21(12):113. 10.1007/s11912-019-0857-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ehret C, Young C, Ellefson CJ, Aase LA, Jatoi A (2022) Frequency and symptomatology of hiccups in patients with cancer: using an on-line medical community to better understand the patient experience. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 39(2):147–151. 10.1177/10499091211006923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ehret C, Martin NA, Jatoi A (2023) What percentage of patients with cancer develop hiccups with oxaliplatin- or cisplatin-based chemotherapy? A compilation of patient-reported outcomes. PLoS ONE 18(1):e0280947. 10.1371/journal.pone.0280947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jatoi A (2022) Evaluating and palliating hiccups. BMJ Support Palliat Care 12(4):475–478. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2022-003676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adam E (2020) A systematic review of the effectiveness of oral baclofen in the management of hiccups in adult palliative care patients. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother 34(1):43–54. 10.1080/15360288.2019.1705457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang T, Wang D (2014) Metoclopramide for patients with intractable hiccups: a multicentre, randomised, controlled pilot study[J]. Intern Med J 44(12a):1205–1209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hou X, Pan L, Wang Q (2018) Hiccup after chemotherapy for lung cancer[J]. World Journal of Acupuncture-Moxibustion 28(4):303–305 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ehret CJ, Le-Rademacher J, Storandt MH, Martin N, Rajotia A, Jatoi A (2022) A randomized, double-blinded feasibility trial of educational materials for hiccups in chemotherapy-treated patients with cancer. Support Care Cancer 31(1):30. 10.1007/s00520-022-07457-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choi TY, Lee MS, Ernst E (2012) Acupuncture for cancer patients suffering from hiccups: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Complement Ther Med 20(6):447–455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stacey SK, Bassett MS (2024) Hiccup relief using active prolonged inspiration. Cureus 16(1):e53045. 10.7759/cureus.53045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Obuchi T, Makimoto Y, Iwasaki A (2020) Hiccups always cease when exposed to acute hypercapnia. Chest 157(6):A380 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang FY, Lu CL (2012) Hiccup: mystery, nature and treatment. J Neurogastroenterol Motil 18(2):123–30. 10.5056/jnm.2012.18.2.123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Calsina-Berna A, García-Gómez G, González-Barboteo J et al (2012) Treatment of chronic hiccups in cancer patients: a systematic review[J]. J Palliat Med 15(10):1142–1150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steger M, Schneemann M, Fox M (2015) Systemic review: the pathogenesis and pharmacological treatment of hiccups. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 42(9):1037–1050. 10.1111/apt.13374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chinese Society of Neurosurgery, Chinese Neurosurgery Intensive Care Management Group (2016) Expert consensus on digestion and nutrition management of critically ill neurosurgery patients in China (2016)[J]. Chinese Med J 96(21):1643–1647.10.3760/cma.j.issn.0376-2491.2016.021.005

- 19.Moretto EN, Wee B, Wiffen PJ, Murchison AG (2013) Interventions for treating persistent and intractable hiccups in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013(1):CD008768. 10.1002/14651858.CD008768.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steger M, Schneemann M, Fox M (2015) Systemic review: the pathogenesis and pharmacological treatment of hiccups[J]. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 42(9):1037–1050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jeon YS, Kearney AM, Baker PG (2018) Management of hiccups in palliative care patients[J]. BMJ Support Palliat Care 8(1):1–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kocak AO, Akbas I, Kocak MB et al (2020) Intradermal injection for hiccup therapy in the emergency department[J]. Am J Emerg Med 38(9):1935–1937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kishi Y, Nakawaga M, Inumaru A, Nambu M, Sakaguchi M, Murabata M, Matsuoka M, Kako J (2025) Interventions for hiccups in adults: a scoping review of western and eastern approaches. Palliat Med Rep 6(1):171–178. 10.1089/pmr.2024.0109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alvarez J, Anderson JM, Snyder PL, Mirahmadizadeh A, Godoy DA, Fox M, Seifi A (2021) Evaluation of the forced inspiratory suction and swallow tool to stop hiccups. JAMA Netw Open 4(6):e2113933. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.13933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kako J, Kajiwara K, Kobayashi M (2020) Traditional influences within studies of nonpharmacological interventions for hiccups in adults: a systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage 60(4):e34–e37. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Annunziata MA, Muzzatti B, Bidoli E, Flaiban C, Bomben F, Piccinin M, Gipponi KM, Mariutti G, Busato S, Mella S (2020) Hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS) accuracy in cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 28(8):3921–3926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yuan DM, Li Q, Zhang Q, Xiao XW, Yao YW, Zhang Y, Lv YL, Liu HB, Lv TF, Song Y (2016) Efficacy and safety of neurokinin-1 receptor antagonists for prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 17(4):1661–1675. 10.7314/apjcp.2016.17.4.1661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang L, Wang H, Liu Y (2021) The effectiveness of non-pharmacological interventions in reducing chemotherapy-induced hiccups in lung cancer patients: a randomized controlled trial. Support Care Cancer 29(11):6821–6829 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu C, Huang X (2023) Non-pharmacological interventions for the management of chemotherapy-induced hiccups in cancer patients: a narrative review. Oncol Lett 22(2):1679–1687 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Canonica S, Eze R, Carlen F, Guechi Y, Schmutz T (2024) Hoquet chronique : diagnostic et traitement [Chronic hiccups: diagnosis and treatment]. Rev Med Suisse 20(874):991–995. 10.53738/REVMED.2024.20.874.991 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Li X, Chen J, Wang Z (2022) A systematic review and meta-analysis of acupuncture for the treatment of chemotherapy-induced hiccups. Complement Ther Med 47:102645 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lederer AK, Schmucker C, Kousoulas L et al (2018) Naturopathic treatment and complementary medicine in surgical practice. Dtsch Arztebl Int 115(49):815–821. 10.3238/arztebl.2018.0815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith JA et al (2020) Behavioral interventions for the management of hiccups in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy: a pilot study. J Palliat Care Med 10(3):251–258 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luo X, Yang L, Chen J, Zhang J, Zhao Q, Zhu J (2023) Chemotherapy induced nausea and vomiting may cause anxiety and depression in the family caregivers of patients with cancer. Front Psychiatry. 14:1221262. 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1221262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Steger M, Schneemann M, Fox M (2015) Systemic review: the pathogenesis and pharmacological treatment of hiccups. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 42:1037–1050. 10.1111/apt.13374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ke X, Wu Y, Zheng H (2023) Successful termination of persistent hiccups via combined ultrasound and nerve stimulator-guided singular phrenic nerve block: a case report and literature review. J Int Med Res 51(12):3000605231216616. 10.1177/03000605231216616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.