Abstract

Polycomb repressive complexes (PRC) and nucleosome remodeling and deacetylase (NuRD) complex are crucial for regulating the expression of pluripotent and developmental genes and maintaining the characteristics of mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs). However, the interplay between the Polycomb and NuRD complexes in mESCs, particularly under protein kinase C (PKC) inhibition, remains to be elucidated. We knocked down Polycomb complexes components Ezh2, Ring1b, and Cbx7 via short hairpin RNA interference and observed significant reductions in most NuRD complex components, especially Mbd3, Mta1, Rbbp4, and Rbbp7. Similarly, Ezh2 overexpression increased the levels of these major NuRD complex components. Further, Mbd3 knockdown significantly reduced the expression of PRC1 major components Ring1b, Rybp, and Cbx7 and PRC2 major components Ezh2, Suz12, and Eed, but its overexpression had no significant effect on their levels. These results indicate that PKC inhibition provides a suitable environment for the expression of PRC components. Altogether, our study demonstrates that mESCs exhibit mutual gene regulation of Polycomb and NuRD complexes under PKC inhibition that maintains pluripotency and self-renewal abilities and regulates the plasticity of mESCs to balance between pluripotency and cell fate determination.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-12427-3.

Keywords: Embryonic stem cells, Epigenomics, PKCi, PRC, NuRD, Mouse

Subject terms: Embryonic stem cells, Epigenetics

Introduction

The regulation of pluripotency and self-renewal in embryonic stem cells (ES) involves a complex interplay of factors, including transcription factors, epigenetic changes, and signaling pathways1,2. Key epigenetic modifications encompass histone methylation3histone acetylation4and DNA methylation5. Polycomb repressive complexes (PRC) and nucleosome remodeling and deacetylase (NuRD) complex are crucial in maintaining and differentiating embryonic stem cells (ESCs)6–9. PRC are divided into Polycomb repressive complex 1 (PRC1) and 2 (PRC2), which modify histone H2AK119ub1 and H3K27me1/2/3, respectively10–12. In mammals, PRC2 core components include enhancer of zeste 2 (EZH2) or its paralogue EZH1, embryonic ectoderm development (EED), suppressor of zeste 12 (SUZ12), and retinoblastoma-binding protein (RBBP4 or RBBP7)13. EZH1 and EZH2 function as histone methyltransferases, catalyzing the methylation of lysine 27 on histone H3 14. SUZ12 and EED enhance the catalytic activity of EZH2 15. PRC1 components facilitate the addition of a ubiquitin group to lysine 119 of histone H2A to form H2AK119ub1, with this process mediated by E3 ligase RING finger protein 1 (RING1A/B)16. RING1A/B forms a heterodimer with one of six polycomb group ring-finger domain proteins (PCGF1–6)17,18. In mammals, PRC1 is further divided into canonical PRC1 (cPRC1) and non-canonical PRC1 (ncPRC1), both of which include RING1A or RING1B. The cPRC1 complex contains a chromobox protein homolog (CBX) subunit (CBX2/4/6/7/8), PCGF2 or PCGF4, and polyhomeotic homologs (PHC1/2/3)19. PRC2 is recruited to chromatin by cofactors and/or RNA, catalyzing H3K27me3 modification through methyltransferase activity20. When the H3K27me3 pattern is established, the PRC1 complex is recruited through the chromatin domain of the CBX protein, leading to the formation of H2AK119ub1 by RING1A/B2. CBX7, a critical component of cPRC1, substantially influences the chromatin-binding ability of RING1B and MEL18, relying entirely on the H3K27me3 modification pattern21. The ncPRC1 complex comprises the RING1A/B and YY1 binding protein (RYBP) or its homolog YY1-associated factor 2 (YAF2) and binds to PCGF1/3/5/6-assembled PRC1.1, PRC1.3, PRC1.5, and PRC1.6 complexes, respectively19. RYBP enhances RING1A/B activity18. The ncPRC1 function is independent of the H3K27me3 modification22. The enzymatic activity of RING1B is essential for gene repression and chromatin condensation in ESCs17. EZH2-catalyzed H3K27me3 facilitates PRC1 recruitment and gene silencing14,20. Both PRC1 and PRC2 bind to gene promoters of developmental regulators that feature unique bivalent domains (H3K4me3/H3K27me3), in which H3K27me3 represses gene expression and supports ESCs self-renewal and H3K4me3 activates genes during differentiation23–25.

NuRD is a multisubunit protein complex primarily comprising methyl-CpG-binding domain (MBD2/3), histone deacetylase (HDAC1/2), chromodomain helicase DNA-binding protein (CHD3/4), histone chaperone protein RBBP4/7, transcriptional repressor protein GATAD2A and/or GATAD2B, metastasis-associated protein (MTA1/2/3), and deleted in oral cancer-1 protein (DOC1)26. CHD3/4, GATAD2A/B, and DOC1 contribute to chromatin remodeling subcomplex, whereas HDAC1/2, RBBP4/7, and MTA1/2/3 contribute to deacetylase subcomplex27; MBD2/3 links these subcomplexes to produce an intact NuRD complex. Although HDAC and RBBP proteins are involved in other chromatin modification complexes, MBD, GATAD2, and MTA proteins remain specific to NuRD28. NuRD complexes not only regulate gene expression but also function in chromatin assembly, DNA damage repair, and genome stabilization29,30. They also regulate ESCs pluripotency and cell differentiation via PRC2 recruitment31,32. Pluripotent gene repression alters transcriptional heterogeneity and differentiation of ESCs through the NuRD complex33. In addition to stabilizing the NuRD complex, MBD2/3 represses pluripotent genes and regulates developmental gene expression to ensure proper ESCs differentiation8,33.

The Polycomb and NuRD complexes function in an integrated gene regulation network involving other chromatin regulators and transcription factors34. In mammals, SWItch/Sucrose Non-Fermentable (SWI/SNF) complexes govern the naïve pluripotency ability of mouse ESCs (mESCs)35and both NuRD and Polycomb complexes can antagonize SWI/SNF as inhibitory complexes36–39. Throughout development, a well-balanced gene regulatory network orchestrates gene expression and cell fate decisions in fine and accurate manner31,40. The Polycomb and NuRD complexes co-regulate a shared set of target genes involved in embryonic development and signaling pathways related to stem cell self-renewal32. NuRD-mediated deacetylation facilitates the recruitment of H3K27me332, thereby maintaining the bivalent chromatin domains by both H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 of pluripotency genes, particularly Nanog gene41. We hypothesize that the Polycomb and NuRD complexes synergistically regulate the stability of stem cells in mESCs under protein kinase C inhibition (PKCi). NuRD-mediated H3K27 deacetylation in self-renewing mESCs contributes to PRC2 recruitment for gene repression32. Therefore, NuRD may create a chromatin environment that facilitates subsequent Polycomb repression, and PRC2 may assist in NuRD recruitment32. However, mechanisms through which Polycomb and NuRD complexes interactions influence stemness and self-renewal of mESCs are unknown and remain to be elucidated.

PKC inhibition conditions represent a culture system capable of generating ESCs with germline transmission competence. PKC regulates the pluripotency and differentiation of ESCs42,43. Pluripotency of ESCs in different mammalian species can be maintained by inhibiting PKC signaling44,45. Debasree Dutta et al.45 found that the atypical PKC isoform (PKCζ) maintains the pluripotency of mESCs without activating STAT3 or inhibiting the ERK/GSK3 signaling pathway, and that NF-κB acts as a downstream target of PKCζ, participating in regulating lineage commitment in mESCs. Subsequently, Rajendran et al.44 also demonstrated that inhibition of the PKC signaling pathway maintains pluripotency in rESCs. This effect is achieved primarily through the PKC inhibitor (PKCi, Gö6983) suppressing PKCζ phosphorylation, thereby reducing the phosphorylation level at Ser311 on NF-κB subunits. The reduction of NF-κB decreases its binding to pre-existing NF-κB binding motifs in the promoter regions of miR-21 and miR-29a, which further enhances the pluripotency of ESCs. ESCs derived under PKC inhibition conditions not only exhibit germline transmission competence but also possess a higher naïve pluripotency state compared to serum/LIF-cultured ESCs44,45. However, interaction and regulatory expression of Polycomb and NuRD complexes in mESCs under PKC inhibition remains unexplored.

In this study, we employed short hairpin RNA (shRNA) interference to knock down the expression of EZH2, RING1B, and CBX7 in Polycomb complexes and overexpressed EZH2 to delineate its regulatory effect on the expression of NuRD complex components. Conversely, we knocked down or overexpressed MBD3, a crucial component of the NuRD complex, to investigate its role in regulating the expression of Polycomb complexes components and on pluripotency and self-renewal in mESCs under PKCi.

Materials and methods

Unless otherwise indicated, all chemicals and reagents used in this study were sourced from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Animal management, hormone-induced superovulation, and embryo collection

C57BL/6J mice aged 6–8 weeks purchased from the Comparative Medicine Center of Yangzhou University. All animal experiments complied with the ARRIVE guidelines and were approved by Nanjing Normal University’s Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC-20201209) and followed guidelines established by the U.S. National Institutes of Health. Female mice were intraperitoneally injected with 7.5 IU pregnant mare serum gonadotropin (Ningbo Second Hormone Factory, China), followed by 7.5 IU human chorionic gonadotropin (Ningbo Second Hormone Factory) 48 h later. They were mated with male mice at a 1:1 ratio, and vaginal plugs were checked the following morning. Blastocysts were flushed from the uterus with M2 medium on day 3.5 after the plug was observed.

De novo derivation and maintenance of mESCs under PKCi

De novo derivation and maintenance of mESCs as described previously8. Briefly, blastocysts were cultured using 0.1% gelatin-coated dishes (ES-006-B; EmbryoMax® 0.1% Gelatin Solution, Millipore) containing mitomycin C–treated mouse embryonic fibroblasts. After 1 week, outgrowths were digested with Accutase (07920; STEMCELL Technologies, WA, USA) and inoculated into a new 24-well plate containing the feeder layer; mESCs were passaged using Accutase at a ratio of 1:3 every 3–5 days in 35-mm dishes containing the feeder layer and incubated in a 5% CO2 chamber at 37℃. Blastocysts and mESCs were cultured in KnockOut™ Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (10829018; Gibco, USA) supplemented with 15% KnockOut™ Serum Replacement (10828028; Gibco), 1% penicillin/streptomycin (SV30010; HyClone, USA), 2mM GlutaMax Supplement (35050-061; Gibco), 0.1mM β-mercaptoethanol (ES-007-E; EmbryoMax 2-Mercaptoethanol, Millipore), 1mM sodium pyruvate (11360088; Gibco), and 7.5µM PKC inhibitor (Gӧ6983, 133053-19-7; Selleck Chemicals, USA).

shRNA interference and overexpression

The experiments of interference and overexpression were performed as described in previous literature8. Briefly, HEK293T cells were transfected with shEZH2, shRING1B, shCBX7, and shMBD3 interference plasmids; oe-EZH2 and oe-MBD3 overexpression plasmids; and psPAX and pMD2.G viral packaging plasmids in a 5:3:2 ratio using the Lipofectamine™ 2000 Transfection Reagent (11668019; Invitrogen, USA) in a 1:2 ratio. Plasmids shEZH2, shRING1B, shCBX7, and oe-EZH2 were purchased from Tsingke (Beijing, China); shMBD3 from GenePharma (Shanghai, China); and oe-MBD3 from Addgene. After transfection for 48 h and 72 h, viral supernatants were collected and filtered (0.45-µm pore size, Millipore). For lentiviral transfection, mESCs at 70–80% confluency were infected with a lentiviral diluent and incubated overnight at 37℃ in a 5% CO2 chamber. After 24 h, the medium was replaced with a fresh PKCi medium, and incubation continued for another 48 h. The short hairpin target sequences were as follows: shEZH2, GCACAAGTCATCCCGTTAAAG and GCAAATTCTCGGTGTCAAACA; shRING1B, GCAGACAAATGGAACTCAACC and GCATCAGGAAAGGGTCTTAGC; shCBX7, CCTCAAGTGAAGTTACCGTGA and CGTGACTGACATCACCGCCAA; shMBD3, GCAGACTGCATCCATCTTCAA and CACCGGAAAGATGTTGATGAA.

RNA isolation and quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted using the VeZol Reagent (R411-00; Vazyme, Nanjing, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Reverse transcription was performed with 1 µg RNA using ABScript III RT Master Mix for qPCR with gDNA Remover (RK20429, ABclonal, China). The synthesized cDNA was tested using Genious 2X SYBR Green Fast qPCR Mix (RK21207; ABclonal). The RT-qPCR primers used in this study are presented in Table 1. The results were normalized using the expression of β-actin. The relative mRNA level was calculated as described previously46.

Table 1.

RT-PCR primer sequences and product sizes.

| Gene | Forward primer (5ʹ–3ʹ) | Reverse primer (5ʹ–3ʹ) | Product size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cbx6 | GCCGAATCCATCATTAAACG | TTGGGTTTAGGTCCCCTCTT | 194 |

| Cbx7 | GAGGCAGAAGCAGACCTGAC | GCCGCTATTCACAGCTTCTC | 170 |

| Eed | AGCCACCCTCTATTAGCAGTT | GCCACAAGAGTGTCTGTTTGGA | 206 |

| Ezh1 | TTCGTGTCCAGCCTGTTCA | AGTGTTCAGAGACCGCATCA | 125 |

| Ezh2 | GGACCACAGTGTTACCAGCA | GGGCGTTTAGGTGGTGTCTT | 167 |

| Hdac1 | ACAAAGCCAATGCTGAGGAGA | TCAAACAAGCCATCAAACACC | 154 |

| Hdac2 | CGGTGTTTGATGGACTCTTTG | AGAACCCTGATGCTTCTGACT | 150 |

| Mbd3 | CAGCCATTGCGAGTGCTCTAC | CTGTCACCATGAAGGCTTTGC | 129 |

| Mta1 | AGGCTGACATCACTGACT | AGGCTGACATCACTGACT | 111 |

| Pcgf1 | TGCCACCACCATCACAGAG | CTGCGTCTCGTGGATCTTGA | 112 |

| Pcgf2 | CGGACCACACGGATTAAAATCA | CGATGCAGGTTTTGCAGAAGG | 124 |

| Pcgf3 | CAGGTAAGCATCTGTCTGGAATG | GTAACAACCACGAACTTGAGAGT | 206 |

| Pcgf4 | CAATGAAGACCGAGGAGAAGTT | TCCGATCCAATCTGCTCTGAT | 107 |

| Pcgf5 | GCCTGGACTACGAGAACAAGA | TCATCACCTTCCTCATCTGCTT | 126 |

| Pcgf6 | TCGTATTCCACCTGAACTTGAT | CCGATAGTTGCTTCTCCTGAA | 141 |

| Phc1 | TAGCACAGATGTCCCTGTATGA | TTGCTGGAGCATGAACTGGTG | 104 |

| Phc2 | CCGACTCAGAGATGGAGGAG | AAAGTCCCACTCGTTTGGTG | 183 |

| Phc3 | TACCAGCGGCAGTATTACCC | TGCAGACTGACAGGAAGGTG | 187 |

| Rbbp4 | GTGCTTCAGATGACCATACCAT | CGTCCTCCACTACTGCTGTA | 114 |

| Rbbp7 | CTGTGGAGGAGCGTGTCAT | CCAGCACTAGCCAATGAAGG | 174 |

| Ring1a | GGAGTGCCTGCATAGGTTCTG | TAGGGACCGCTTGGATACCA | 106 |

| Ring1b | GAGTTACAACGAACACCTCAGG | CAATCCGCGCAAAACCGATG | 158 |

| Rybp | GAAGGTCGAAAAGCCTGACAA | AGCTTCACTAGGAGGATCTTTCA | 130 |

| Suz12 | CCACAGCAGGTTCATCTTCAA | GCATAGGAGCCATCATAACACT | 90 |

| Yaf2 | AAGACCGAGTAGAGAAGGACAA | GATCTCCAACAGTGACTTCCAA | 132 |

| Yy1 | GATACCTGGCATTGACCTCTC | TGTTCTTGGAGCATCATCTTCT | 94 |

| β-actin | TGTTACCAACTGGGACGACA | GGGGTGTTGAAGGTCTCAAA | 165 |

Western blot

The Western blot experiment refers to the previous literature47. Briefly, mESCs were treated with cold RIPA Lysis Buffer 1 (C500005; Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China). The protein level was quantified using the BCA Protein Quantification Kit (E112-01; Vazyme). Total protein (6 µg) from each group was separated using 10% and 12% Tris-HCl gel electrophoresis and then electrotransferred onto a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (03010040001; Roche, Basel, Switzerland) for 2 h in an ice bath. The membrane was blocked with 5% non-fat powdered milk (A600669; Sangon) for 1 h at 22–24 ºC room temperature, then rinsed with tris-buffered saline containing tween 20 (TBST), and incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4℃ after membrane was cropped according to protein markers. The primary antibodies used in this study are presented in Table 2. The next day, the membrane was rinsed with TBST for 15 min three times and incubated with horseradish peroxidase–conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:5000, BS13278; Bioworld) for 2 h on a shaker. The membrane was then processed using the SuperPico ECL Chemiluminescence Kit (E422-01; Vazyme). Protein bands were visualized using a Tanon 4600 Chemiluminescent Imaging System. β-actin was used as an internal control. Different target proteins were detected in the same experiment, or experiments with different purposes were performed to detect the same index. According to protein markers, the membranes were cut moderately before antibody hybridization, or the images were cropped moderately after visualization of the blots membranes.

Table 2.

Sources of antibodies for Western blot.

| Antibodies | Source | Identifier |

|---|---|---|

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-CBX7 | Servicebio Technology | Catalog NO.: GB114894 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-EED | ABclonal Technology | Catalog NO.: A12773 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-EZH1 | ABclonal Technology | Catalog NO.: A5818 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-EZH2 | ABclonal Technology | Catalog NO.: A5743 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-HDAC1 | ABclonal Technology | Catalog NO.: A0238 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-HDAC2 | ABclonal Technology | Catalog NO.: A2084 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-MBD3 | ABclonal Technology | Catalog NO.: A8905 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-MTA1 | ABclonal Technology | Catalog NO.: A16085 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-PCGF4 | ABclonal Technology | Catalog NO.: A0211 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-RBBP4 | ABclonal Technology | Catalog NO.: A3645 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-RBBP7 | ABclonal Technology | Catalog NO.: A13456 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-RING1A | ABclonal Technology | Catalog NO.: A20171 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-RING1B | ABclonal Technology | Catalog NO.: A5563 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-RYBP | ABclonal Technology | Catalog NO.: A14605 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-SUZ12 | ABclonal Technology | Catalog NO.: A7786 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-β-actin | ABclonal Technology | Catalog NO.: AC026 |

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) and data analysis

Total RNA was isolated from mESCs using TRIzol reagent, and RNA integrity was precisely quantified with the Agilent 2100 RNA 6000 Nano Kit. cDNA synthesis and library preparation were performed using the EpiTMDRUG-seq methodology (Digital mRNA with pertUrbation of Genes)48. Following library construction, the library concentration and fragment size are detected using Qubit and Agilent 2100 respectively. High-throughput sequencing was executed on the GENEMIND SURFSeq 5000. Raw sequencing reads underwent quality control processing through fastp49 software (version 0.18.0) for adapter trimming and quality filtering. Filtered reads were aligned to the reference mouse genome (GRCm38/mm10) using NextGenMap, followed by gene expression quantification in FPKM (Fragments Per Kilobase Million) units for annotated genes and transcripts. Differential expression analysis between experimental and control groups was performed using DESeq2, with statistically significant differential expressed genes (DEGs) identified under the threshold criteria of P < 0.05 and |log2(fold change)| > 1. GO and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analysis used the clusterProfiler package in R (4.3.3), with significant enrichment defined as a P-value < 0.05 50.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were conducted in biological triplicates for each group unless otherwise stated. Data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean. The differences between experimental groups were analyzed using independent sample t-tests. The letters ‘a’ and ‘b’ indicate significant differences between groups (P < 0.05).

Results

Knockdown of PRC2 component EZH2 significantly reduces the expression of most NuRD complex subunits

To elucidate the regulatory function of PRC2 in NuRD complex in mESCs under PKCi, we used RT-qPCR to measure the mRNA and protein expression of Mbd3, Hdac1, Hdac2, Mta1, Rbbp4, and Rbbp7, which are core components of the NuRD complex, after Ezh2 knockdown. After Ezh2 silencing, both Ezh2 mRNA and protein levels in the experimental group were reduced by 67% compared with those in the control group (Fig. 1A and B, respectively; both P < 0.05). Ezh2 knockdown also significantly reduced the mRNA expression of Mbd3, Hdac1, Hdac2, Mta1, Rbbp4, and Rbbp7 (Fig. 1C, P < 0.05). This is consistent with transcriptome analysis showing reduced expression of NuRD subunits (Supplementary Fig. S1A). Western blot analysis revealed that Ezh2 knockdown reduced the protein expression of MBD3 by 51%, HDAC1 by 37%, HDAC2 by 45%, MTA1 by 57%, RBBP4 by 43%, and RBBP7 by 55% (Fig. 1D, P < 0.05).

Fig. 1.

Effect of Ezh2 knockdown on NuRD complex components in mESCs under PKCi. (A) RT-qPCR results after Ezh2 knockdown show that the mRNA expression of Ezh2 is significantly decreased to 33%. (B) Western blot results after Ezh2 knockdown show that the protein expression of Ezh2 is significantly decreased to 33%. (C) RT-qPCR results show that the mRNA expression of Mbd3 (from 1.0 to 0.71), Hdac1 (from 1.0 to 0.73), Hdac2 (from 1.0 to 0.76), Mta1 (from 1.0 to 0.67), Rbbp4 (from 1.0 to 0.67), and Rbbp7 (from 1.0 to 0.60) is significantly downregulated after Ezh2 knockdown. (D) The protein expression of Mbd3 (from 1.0 to 0.51), Hdac1 (from 1.0 to 0.63), Hdac2 (from 1.0 to 0.55), Mta1 (from 1.0 to 0.43), Rbbp4 (from 1.0 to 0.57), and Rbbp7 (from 1.0 to 0.45) is significantly downregulated after Ezh2 knockdown. The letters ‘a’ and ‘b’ indicate significant differences among groups (P < 0.05).

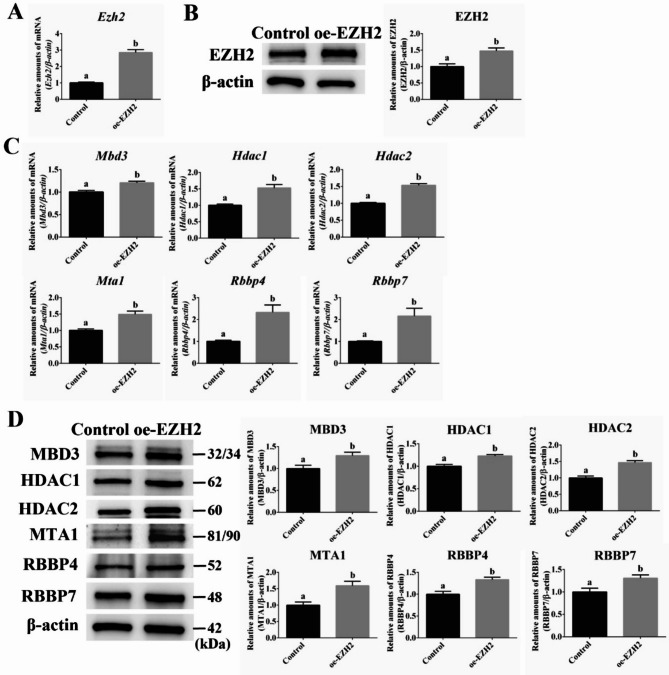

Overexpression of PRC2 component EZH2 significantly increases the expression of NuRD complex subunits

The previous experiment demonstrated that Ezh2 knockdown downregulated the expression of NuRD complex components, implying a regulatory function of the Polycomb complexes. We hypothesized that Ezh2 overexpression might upregulate the expression of NuRD complex components. Ezh2 overexpression resulted in a 190% increase in its mRNA expression (Fig. 2A, P < 0.05) and 50% increase in its protein expression (Fig. 2B, P < 0.05). RT-qPCR was used to detect mRNA expression changes in Mbd3, Mta1, Hdac1, Hdac2, Rbbp4, and Rbbp7. Ezh2 overexpression significantly increased the expression of most NuRD complex components (Fig. 2C, P < 0.05). Western blot analysis revealed that EZH2 overexpression increased the expression of MBD3 by 30%, MTA1 by 59%, HDAC1 by 23%, HDAC2 by 47%, RBBP4 by 33%, and RBBP7 by 31% (Fig. 2D, P < 0.05).

Fig. 2.

Effect of Ezh2 overexpression on NuRD complex components in mESCs under PKCi. (A) RT-qPCR results show that the mRNA expression of Ezh2 (from 1.0 to 2.9) is significantly increased after Ezh2 overexpression. (B) Western blot results show that the protein expression of Ezh2 (from 1.0 to 1.5) is significantly increased after Ezh2 overexpression. (C) RT-qPCR results show that the mRNA expression of Mbd3 (from 1.0 to 1.21), Hdac1 (from 1.0 to 1.53), Hdac2 (from 1.0 to 1.54), Mta1 (from 1.0 to 1.49), Rbbp4 (from 1.0 to 2.33), and Rbbp7 (from 1.0 to 2.16) is significantly upregulated after Ezh2 overexpression. (D) The protein expression of Mbd3 (from 1.0 to 1.30), Hdac1 (from 1.0 to 1.23), Hdac2 (from 1.0 to 1.47), Mta1 (from 1.0 to 1.59), Rbbp4 (from 1.0 to 1.33), and Rbbp7 (from 1.0 to 1.31) is significantly upregulated after Ezh2 overexpression. The letters ‘a’ and ‘b’ indicate significant differences among groups (P < 0.05).

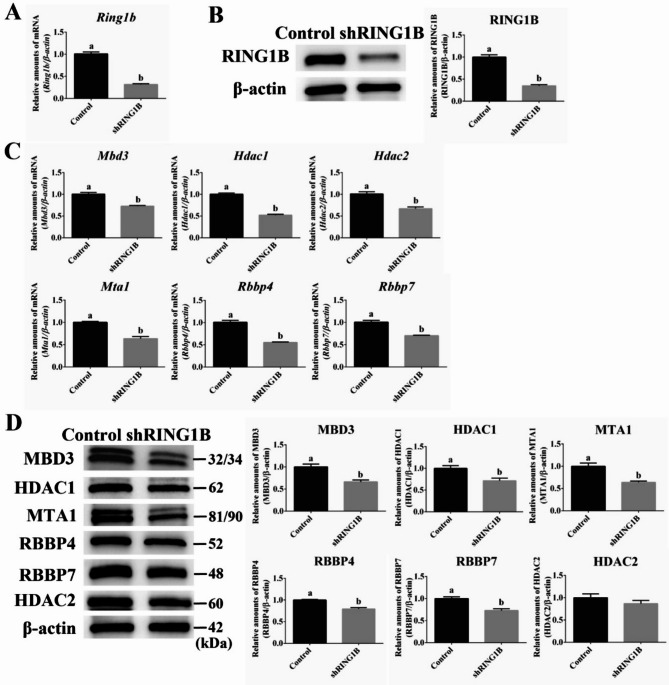

Knockdown of PRC1 component RING1B significantly reduces the expression of NuRD complex subunits

Because PRC2 influenced the expression of NuRD complex components, we hypothesized that PRC1 also regulates these components. Our interference experiment showed that compared with the control group, the Ring1b mRNA level in the experimental group was significantly reduced by 68% (Fig. 3A, P < 0.05) and its protein expression by 65% (Fig. 3B, P < 0.05). RT-qPCR showed that Ring1b knockdown significantly decreased the mRNA expression of Mbd3, Hdac1, Hdac2, Mta1, Rbbp4, and Rbbp7 (Fig. 3C, P < 0.05) and protein expression of MBD3 by 34%; HDAC1, 28%; MTA1, 36%; RBBP4, 21%; and RBBP7, 27% (Fig. 3D, P < 0.05) but had no influence on the expression of HDAC2 (Fig. 3D).

Fig. 3.

Effect of Ring1b knockdown on NuRD complex components in mESCs under PKCi. (A) RT-qPCR results show that the mRNA expression of Ring1b is significantly decreased to 32% of control levels after Ring1b knockdown. (B) Western blot results after Ring1b knockdown show that the protein expression of Ring1b is significantly decreased to 35%. (C) RT-qPCR results show that the mRNA expression of Mbd3 (from 1.0 to 0.71), Hdac1 (from 1.0 to 0.52), Hdac2 (from 1.0 to 0.67), Mta1 (from 1.0 to 0.64), Rbbp4 (from 1.0 to 0.55), and Rbbp7 (from 1.0 to 0.70) is significantly downregulated after Ring1b knockdown. (D) The protein expression of Mbd3 (from 1.0 to 0.66), Hdac1 (from 1.0 to 0.72), Mta1 (from 1.0 to 0.64), Rbbp4 (from 1.0 to 0.79), and Rbbp7 (from 1.0 to 0.73) is significantly downregulated after Ring1b knockdown except that of Hdac2. The letters ‘a’ and ‘b’ indicate significant differences among groups (P < 0.05).

Knockdown of cPRC1 component CBX7 reduces the expression of most NuRD complex subunits

CBX7 primarily maintains pluripotency and self-renewal of ESCs and inhibits lineage commitment and cell differentiation21. We knocked down Cbx7 in mESCs under PKCi and observed that the mRNA expression was reduced by 67% (Fig. 4A, P < 0.05) and protein expression by 48% (Fig. 4B, P < 0.05). RT-qPCR showed that Cbx7 knockdown significantly decreased the mRNA expression of Mbd3, Hdac2, Mta1, Rbbp4, and Rbbp7 (Fig. 4C, P < 0.05) except that of Hdac1 (Fig. 4C). Western blot analysis revealed that Cbx7 knockdown significantly reduced the protein expression of MBD3 by 26%, HDAC2, 30%; MTA1, 38%; RBBP4, 34%; and RBBP7, 41% (Fig. 4D, P < 0.05) but had no significant influence on the expression of HDAC1 (Fig. 4D).

Fig. 4.

Effect of Cbx7 knockdown on NuRD complex components in mESCs under PKCi. (A) RT-qPCR results show that the mRNA expression of Cbx7 is significantly decreased to 33% of control levels after Cbx7 knockdown. (B) Western blot results after Cbx7 knockdown show that the protein expression of Cbx7 is significantly decreased to 52%. (C) RT-qPCR results show that the mRNA expression of Mbd3 (from 1.0 to 0.76), Hdac2 (from 1.0 to 0.68), Mta1 (from 1.0 to 0.68), Rbbp4 (from 1.0 to 0.74), and Rbbp7 (from 1.0 to 0.76) is significantly downregulated after Cbx7 knockdown except that of Hdac1. (D) The protein expression of Mbd3 (from 1.0 to 0.74), Hdac2 (from 1.0 to 0.70), Mta1 (from 1.0 to 0.62), Rbbp4 (from 1.0 to 0.66), and Rbbp7 (from 1.0 to 0.59) is significantly downregulated after Cbx7 knockdown except that of Hdac1. The letters ‘a’ and ‘b’ indicate significant differences among groups (P < 0.05).

Knockdown of NuRD component MBD3 reduces the expression of Polycomb complexes subunits

The Polycomb complexes regulated the expression of NuRD complex components in mESCs under PKCi. We thus explored whether the NuRD complex reciprocally affects the expression of Polycomb complexes components. Following Mbd3 knockdown, we observed a significant 75% decrease in mRNA expression (Fig. 5A, P < 0.05) and 72% decrease in protein expression of Mbd3 (Fig. 5B, P < 0.05). RT-qPCR showed that Mbd3 knockdown significantly reduced the mRNA expression of most Polycomb complexes components, including Ezh1, Ezh2, Suz12, Eed, Rbbp4, Rbbp7, Ring1a, Ring1b, Yaf2, Pcgf1, Pcgf4, Cbx6, Cbx7, Phc1, and Phc2 (Fig. 5C, P < 0.05), but had no influence on the mRNA expression of Rybp, Pcgf2, Pcgf3, Pcgf5, Pcgf6, Jarid2, Yy1, and Phc3 (Fig. 5C). This is consistent with transcriptome analysis showing reduced expression of Polycomb complexes subunits (Supplementary Fig. S1C). Western blot analysis with available antibodies revealed that Mbd3 knockdown significantly reduced the protein expression of EZH2 by 45%, SUZ12 by 34%, EED by 37%, RBBP4 by 43%, RBBP7 by 38%, RING1B by 37%, RYBP by 42%, PCGF4 by 44%, and CBX7 by 50% (Fig. 5D, P < 0.05).

Fig. 5.

Effect of Mbd3 knockdown on Polycomb complexes components in mESCs under PKCi. (A) RT-qPCR results after Mbd3 knockdown show that the mRNA expression of Mbd3 is significantly decreased to 25%. (B) Western blot results after Mbd3 knockdown show that the protein expression of Mbd3 is significantly decreased to 28%. (C) The mRNA expression of Ezh1 (from 1.0 to 0.63), Eeh2 (from 1.0 to 0.76), Suz12 (from 1.0 to 0.79), Eed (from 1.0 to 0.83), Rbbp4 (from 1.0 to 0.80), Rbbp7 (from 1.0 to 0.82), Ring1a (from 1.0 to 0.71), Ring1b (from 1.0 to 0.72), Yaf2 (from 1.0 to 0.83), Pcgf1 (from 1.0 to 0.66), Pcgf4 (from 1.0 to 0.81), Cbx6 (from 1.0 to 0.81), Cbx7 (from 1.0 to 0.74), Phc1 (from 1.0 to 0.68), and Phc2 (from 1.0 to 0.84) is significantly downregulated after Mbd3 knockdown; no effect is observed on the expression of Rybp, Pcgf2, Pcgf3, Pcgf5, Pcgf6, Yy1, and Phc3. (D) The protein expression of Ezh2 (from 1.0 to 0.55), Suz12 (from 1.0 to 0.66), Eed (from 1.0 to 0.63), Rbbp4 (from 1.0 to 0.57), Rbbp7 (from 1.0 to 0.62), Ring1b (from 1.0 to 0.63), Rybp (from 1.0 to 0.58), Pcgf4 (from 1.0 to 0.56), and Cbx7 (from 1.0 to 0.50) is significantly downregulated after Mbd3 knockdown except that of Ezh1. The letters ‘a’ and ‘b’ indicate significant differences among groups (P < 0.05).

Overexpression of NuRD component MBD3 does not affect the expression of polycomb complexes subunits

Reportedly, Mbd3 overexpression can induce extensive differentiation of mESCs, whereas its knockdown can inhibit this process8. Our results showed that Mbd3 knockdown reduced the expression of Polycomb complexes components. The Polycomb complexes are an essential epigenetic regulator in maintaining stem cell identity20,51; it inhibits the expression of developmental gene regulators during mESCs self-renewal, and its dysregulation leads to cell differentiation25. We thus explored whether Mbd3 overexpression influences the expression of Polycomb complexes components. Following lentivirus infection, Mbd3 expression in mESCs was upregulated, with a 1800% increase in mRNA (Fig. 6A, P < 0.05) and 100% increase in protein (Fig. 6B, P < 0.05) levels. RT-qPCR showed that Mbd3 overexpression had no significant influence on the mRNA and protein expression of Ezh1, Ezh2, Ring1b, Suz12, Eed, Rbbp4, Rbbp7, Rybp, and Cbx7 (Fig. 6C and D), although it did increase the mRNA expression of Ring1a, Pcgf3, Pcgf4, Phc1, Phc2, and Yaf2 (Fig. 6C, P < 0.05). Western blot analysis with available antibodies revealed no significant change in the protein expression of RING1A and PCGF4 (Fig. 6C and D).

Fig. 6.

Effect of Mbd3 overexpression on Polycomb complexes components in mESCs under PKCi. (A) RT-qPCR results show that the mRNA expression of Mbd3 (from 1.0 to 19.3) is significantly increased after Mbd3 overexpression. (B) Western blot results show that the protein expression of Mbd3 (from 1.0 to 2.0) is significantly increased after Mbd3 overexpression. (C) The mRNA expression of Ezh1, Ezh2, Suz12, Eed, Rbbp4, Rbbp7, Ring1b, Rybp, and Cbx7 is not significantly changed but that of Ring1a (from 1.0 to 1.21), Pcgf3 (from 1.0 to 1.14), Pcgf4 (from 1.0 to 1.19), Phc1 (from 1.0 to 1.20), Phc2 (from 1.0 to 1.20), and Yaf2 (from 1.0 to 1.35) is upregulated. (D) No significant difference is observed in the protein expression of EZH1, EZH2, SUZ12, EED, RBBP4, RBBP7, RING1B, RYBP, PCGF4, and CBX7 between the Mbd3 overexpression and control groups. The letters ‘a’ and ‘b’ indicate significant differences among groups (P < 0.05).

Discussion

Our research clearly demonstrated that both Polycomb and NuRD complexes reciprocally and interactively regulate their gene expression in mESCs under PKCi. The regulation of gene expression by Polycomb and NuRD complexes may indeed involve both direct and indirect mechanisms, depending on the specific biological context. Specifically, the PRC2 component EZH2 and PRC1 components RING1B and CBX7 directly regulated the expression of NuRD subunit genes. Polycomb and NuRD complexes can regulate pluripotency and differentiation of mESCs, respectively17,31,52,53. Both complexes can condense the chromatin structure and repress the expression of developmentally related genes54–56. To the best of our knowledge, no prior research has adequately demonstrated a direct interplay between the Polycomb and NuRD complexes. In mESCs, PRC2 (via EZH2) and PRC1 (via RING1B) components catalyze H3K27 methylation and H2AK119ub monoubiquitination, respectively; these histone modifications can regulate chromatin structure or directly regulate target genes, inhibiting several developmental regulatory genes23,57. The Polycomb complexes maintain and amplify the repressive state of targeted chromatin by regulating its structure, thus facilitating cell lineage differentiation and related gene expression58. EZH2, an essential catalytic subunit of the PRC2 complex, mainly modifies H3K27me3 12. Knockout of EZH2 leads to an aberrant reactivation of mesoderm/endoderm genes during neural induction in human ESCs59and causes embryonic death in mice60. In mESCs, EZH2 knockdown influences mesoderm differentiation, whereas simultaneous EZH1/EZH2 knockdown significantly reduces the H3K27me3 marker at the target site of the Polycomb complexes57. We found that the mRNA and protein expression of NuRD complex components Mbd3, Hdac1, Hdac2, Mta1, Rbbp4, and Rbbp7 were significantly decreased after EZH2 knockdown (Fig. 1). EZH2 knockdown under PKC inhibition also increases the proportion of stem cells, especially by raising the proportion of undifferentiated mESCs colonies from 43 to 51%, while reducing differentiated colonies from 20 to 10% and mixed colonies from 37 to 40%. RNA-seq analysis also demonstrated that downregulated genes following EZH2 knockdown showed enrichment not only in epigenetic regulation mediating transcriptional suppression, but also in biological processes related to stem cell differentiation when compared with control groups (Supplementary Fig. S1B). The mechanism underlying the downregulation of the gene expression of NuRD complex components after EZH2 knockdown remains unclear. We hypothesize that the downregulation of NuRD complex components following EZH2 knockdown may result from either direct epigenetic regulation or indirect effects mediated by other transcription factors. ESCs maintenance is regulated by the fine network of transcription factors that regulate gene expression and finally direct stem cell self-renewal, pluripotency, cell determination, and cell differentiation1,61–63. We found that the reduced expression of Ezh2 in mESCs leads to decreased H3K27me3 modifications on chromatin12thus enhancing the expression of pluripotent genes that promote mESCs self-renewal and pluripotency41. The increased pluripotency transcription factors and/or self-renewal regulatory network in stem cells effectively inhibit the gene expression of NuRD complexes. This hypothesis warrants further investigation. This study also showed that EZH2 overexpression significantly upregulated the expression of NuRD complex components, especially MBD3 (Fig. 2), indirectly confirming the regulatory function of EZH2 in NuRD gene expression.

The PRC1 component RING1B catalyzes H2AK119 monoubiquitination16. In mESCs, RING1A/B knockout leads to morphological loss and arrest of proliferation of normal stem cells, and dysregulation of gene expression related to differentiation and development, as well as down-regulation of Oct3/4 expression and up-regulation of Gata4 expression52. RING1B also plays a role in the early neural differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells64. Our lentiviral infection of mESCs to reduce the mRNA and protein expression of Ring1b resulted in a reduced expression of NuRD complex components, consistent with the effects observed with Ezh2 knockdown. The mRNA and protein expression of Mbd3, Hdac1, Mta1, Rbbp4, and Rbbp7 were also reduced (Fig. 3). NuRD not only regulates the self-renewal of ESCs8,31,53but also maintains the characteristics of the ESCs lineage by regulating the dynamic levels of pluripotency genes and maintaining transcriptional heterogeneity33. NuRD inhibits the expression of pluripotency genes, and the cells are further differentiated upon removal of self-renewal factors33.

E3 activity of RING1B is required to repress Polycomb targets and maintain ESCs17. Our results showed that RING1B knockdown increased the proportion of mESCs differentiated colonies from 16 to 23%, mixed colonies from 38 to 43% and decreased the proportion of undifferentiated colonies from 46 to 34% under PKC inhibition. Therefore, we speculate that under PKCi RING1B knockdown disrupts NuRD regulation of pluripotent and differentiation genes; the downregulation of NuRD components would derepress differentiation genes by increasing their expression, which would, in turn, inhibit the expression of pluripotent genes. Similarly, CBX7 knockdown decreased the mRNA and protein expression of Mbd3, Hdac2, Mta1, Rbbp4, and Rbbp7 (Fig. 4). Reportedly, CBX7 knockdown upregulates differentiation- and lineage-related genes in stem cells21. We demonstrated that CBX7 knockdown increased the proportion of mESCs differentiated colonies from 17 to 22% and mixed colonies from 32 to 39%, thus reducing the proportion of undifferentiated colonies from 51 to 39% under PKC inhibition. We hypothesized that under PKCi, Cbx7 knockdown alleviates its repressive effect on ectodermal differentiation gene expression. In the context of stem cells, the protein expression of differentiation genes may inhibit the expression of components of the NuRD complex. As the NuRD complex components decrease, their ability to suppress differentiation genes is also reduced, creating a feedback loop that further enhances the expression of development and differentiation genes. The study ultimately suggests that PRC1, which includes CBX7, directly influences the expression of NuRD complex components, thereby impacting the differentiation process. To date, no studies have investigated the epigenetic regulation of ESCs by Polycomb complexes under PKCi. Previous study has also shown that PRC2/cPRC1 and vPRC1 cooperate to maintain silencing of lineage-specific genes6. So, we propose that the Polycomb complexes regulates the expression and stability of the NuRD complex in mESCs under PKCi.

The NuRD complex facilitates the formation of heterochromatin and termination of gene transcription26,65,66while also promoting transcriptional heterogeneity and determining cell lineages by inhibiting pluripotent gene expression33. MBD3 stabilizes the structure and function of the NuRD complex53. Basically, MBD3 can recognize specific DNA sequences, then directly bind to the target genes, thus finally perform essential and repressive biological functions33. MBD3 is vital for maintaining the pluripotency of ESCs and contributes to mESCs self-renewal independently of the leukemia inhibitory factor53. Mbd3 knockdown leads to an unstable NuRD complex, significantly impacting mESCs differentiation53. RNA-seq experiments revealed that, compared to the control group, MBD3 knockdown resulted in the downregulation of genes associated with histone modification and cellular differentiation (Supplementary Fig. S1D). Importantly, we found the regulatory effect of Mbd3 knockdown on the expression of Polycomb complexes genes. The mRNA and protein expression of Ezh2, Ring1b, and Cbx7 were significantly reduced when MBD3 expression was downregulated. Although the mRNA expression of Rybp was not significantly reduced, its protein expression was reduced (Fig. 5). Nonetheless, the mechanism through which MBD3 regulates PRC remains unclear. We previously found that PKCi effectively suppresses the expression of NuRD complex components8. MBD3 knockdown increased PKCi-derived mESCs pluripotency by increasing NANOG and OCT4 expression and colony formation8. MBD3 knockdown probably reduces the binding of NuRD complex components to pluripotent genes, thereby facilitating the expression of pluripotency genes NANOG and OCT4 8. These pluripotent transcription factors then inhibit the expression of Polycomb complexes components, further promoting pluripotency and self-renewal while increasing the stem cell population. Under PKCi, mESCs contain sufficient PRC to maintain pluripotency and self-renewal, therefore MBD3 overexpression does not regulate the expression of PRC2 and PRC1. The mRNA and protein expression of Polycomb complexes components RING1B, CBX7, RYBP, EZH2, and EZH1 remained unaffected following Mbd3 overexpression, though the mRNA expression of cofactors such as Pcgf3, Pcgf4, Phc1, Phc2, Yaf2, and Ring1a partially increased. However, the protein expression of PCGF4 and RING1A did not significantly change (Fig. 6D). Therefore, although Mbd3 overexpression enhanced the mRNA expression of some Polycomb genes, it did not influence the protein expression of PRC genes. Further, RING1B plays a more significant regulatory role than RING1A, which serves as an auxiliary partner to RING1B in mESCs16. Reportedly, MBD3/NuRD may promote chromatin alterations and PRC2 recruitment32,67resulting in enhanced differentiation of mESCs under PKCi upon MBD3 overexpression8. Our earlier research indicates that MBD3 overexpression or inhibition of PKCi-induced mESCs differentiation results in reduced NANOG, OCT4, and REX1 expression and colony formation; increased differentiation gene expression; and differentiation into flat cell phenotypes8. Thus, there exists a synergy between PRC and NuRD complexes, where a decrease in one repressive complex can suppress the expression of the other. This epigenetic regulation may not function independently in mESCs under PKCi40. In ESCs, pluripotency genes have been shown to interact with transcriptional repression complexes such as Polycomb and NuRD68,69. Particularly the Nanog gene, harbor bivalent chromatin domains marked by both H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 modifications, while the maintenance of H3K27me3 signature specifically depends on PRC2 functional component EZH241. Studies have shown that NuRD-mediated deacetylation and chromatin compaction facilitate the recruitment of H3K27me332,67. So, the Polycomb and NuRD complexes collaboratively regulate the expression of pluripotent and developmental genes33,61while also mutually influencing the stability of complex and execution of function31,32.

The Polycomb and NuRD complexes significantly and interactively influenced the expression and stability of the other complex. However, questions remain about whether there are interactions between their components, how their synergy affects chromatin structure alterations in mESCs under PKCi, and whether other epigenetic factors are involved. Future studies will conduct genome-wide chromatin profiling on histone modifications and subunits of complexes, analyzing the distribution and dynamics of these histone modifications and subunits in the genome, and revealing whether these complexes co-occupy specific chromatin regions. This provides insight into how Polycomb and NuRD complexes interact and cooperatively regulate gene expression and chromatin structure in mESCs under PKC inhibition conditions. Additionally, integrating RNA-seq and ATAC-seq data can establish causal relationships among complex localization, chromatin state transitions, and gene expression programs. It is worth noting that during gene silencing, whether the chromatin remodeling mediated by NuRD precedes histone modification mediated by Polycomb, or whether these processes occur through parallel pathways. Meanwhile, further exploration of the mechanisms contributing to stemness, cell determination, and cell differentiation is essential. Our study provides correlative evidence of mutual regulation. Although these studies lack in-depth exploration of the molecular mechanisms. At present, there is no direct evidence of physical interactions or chromatin occupancy to distinguish direct transcriptional control from indirect effects mediated by chromatin state changes or intermediate factors. Future studies integrating multi-omics (ChIP-seq) will clarify these mechanisms.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrated a mutual gene regulation between the Polycomb and NuRD complexes in mESCs under PKCi. Knockdown of PRC components EZH2, RING1B, or CBX7 significantly decreased the expression of NuRD complex components MBD3, HDAC1, HDAC2, MAT1, RBBP4, and RBBP7, whereas EZH2 overexpression increased the expression of these components in mESCs under PKCi. Similarly, knockdown of the NuRD component MBD3 decreased the expression of Polycomb complexes components, but MBD3 overexpression had no significant effect. The PKCi culture condition in this study provided a favorable epigenetic environment that facilitated interactions between the Polycomb and NuRD complexes67,70directly or indirectly influencing the gene regulation, stability, and function of related complexes. This synergistic regulation alters the epigenetic landscape of mESCs and balances the regulatory expression of pluripotent and developmental genes. Therefore, mESCs are poised at a crucial state where they can either maintain pluripotency or differentiate. This finely controlled dynamic balance ensures that mESCs retain their plasticity during processes of cell differentiation and development when influenced by PKCi.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (Grant No. 32072732 and 32372877to F.D.).

Author contributions

F.W.: Designed and performed the experiments, analyzed and interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript; Z.L.: Designed and performed the experiments, analyzed and interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript; J.H.: Acquired data and revised the manuscript; Y.G.: Acquired data and revised the manuscript; Y.L.: Supervised the work, designed the experiments, interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript; F.D.: Supervised the work, designed the experiments, interpreted the data, financial support and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files. Additional information can be found in the Supplementary Information section. This section includes the full-length / uncropped blots. The raw sequencedata reported in this paper have been deposited in the Genome Sequence Archive71 in National Genomics Data Center72, China National Center forBioinformation / Beijing Institute of Genomics, Chinese Academy of Sciences (GSA: CRA026207) that are publicly accessible athttps://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Fangfang Wu and Zhihui Liu contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Lan Yang, Email: yanglan11@sinopharm.com.

Fuliang Du, Email: fuliangd@njnu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Yeo, J. C. & Ng, H. H. The transcriptional regulation of pluripotency. Cell. Res.23 (1), 20–32 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morey, L., Santanach, A. & Di Croce, L. Pluripotency and epigenetic factors in mouse embryonic stem cell fate regulation. Mol. Cell. Biol.35 (16), 2716–2728 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cao, R. & Zhang, Y. The functions of E(Z)/EZH2-mediated methylation of lysine 27 in histone H3. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev.14 (2), 155–164 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saraiva, N. Z., Oliveira, C. S. & Garcia, J. M. Histone acetylation and its role in embryonic stem cell differentiation. World J. Stem Cells. 2 (6), 121–126 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gu, T. et al. DNMT3A and TET1 cooperate to regulate promoter epigenetic landscapes in mouse embryonic stem cells. Genome Biol.19 (1), 88 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zepeda-Martinez, J. A. et al. Parallel PRC2/cPRC1 and vPRC1 pathways silence lineage-specific genes and maintain self-renewal in mouse embryonic stem cells. Sci. Adv.6 (14), eaax5692 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Carroll, D. et al. The polycomb-group gene Ezh2 is required for early mouse development. Mol. Cell. Biol.21 (13), 4330–4336 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dai, Y. et al. Nucleosome remodeling and deacetylation complex and MBD3 influence mouse embryonic stem cell Naïve pluripotency under Inhibition of protein kinase C. Cell. Death Discov. 8 (1), 344 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Montibus, B. et al. The nucleosome remodelling and deacetylation complex coordinates the transcriptional response to lineage commitment in pluripotent cells. Biol. Open.13 (1), bio060101 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blackledge, N. P. & Klose, R. J. The molecular principles of gene regulation by polycomb repressive complexes. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol.22 (12), 815–833 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tamburri, S. et al. Histone H2AK119 Mono-Ubiquitination is essential for Polycomb-Mediated transcriptional repression. Mol. Cell.77 (4), 840–56e5 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Margueron, R. et al. Ezh1 and Ezh2 maintain repressive chromatin through different mechanisms. Mol. Cell.32 (4), 503–518 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Margueron, R. & Reinberg, D. The polycomb complex PRC2 and its mark in life. Nature469 (7330), 343–349 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cao, R. et al. Role of histone H3 lysine 27 methylation in Polycomb-group Silencing. Science298 (5595), 1039–1043 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Conway, E., Healy, E. & Bracken, A. P. PRC2 mediated H3K27 methylations in cellular identity and cancer. Curr. Opin. Cell. Biol.37, 42–48 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Napoles, M. et al. Polycomb group proteins Ring1A/B link ubiquitylation of histone H2A to heritable gene Silencing and X inactivation. Dev. Cell.7 (5), 663–676 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Endoh, M. et al. Histone H2A mono-ubiquitination is a crucial step to mediate PRC1-dependent repression of developmental genes to maintain ES cell identity. PLoS Genet.8 (7), e1002774 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gao, Z. et al. PCGF homologs, CBX proteins, and RYBP define functionally distinct PRC1 family complexes. Mol. Cell.45 (3), 344–356 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chan, H. L. & Morey, L. Emerging roles for Polycomb-Group proteins in stem cells and Cancer. Trends Biochem. Sci.44 (8), 688–700 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morey, L. & Helin, K. Polycomb group protein-mediated repression of transcription. Trends Biochem. Sci.35 (6), 323–332 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morey, L. et al. Nonoverlapping functions of the polycomb group Cbx family of proteins in embryonic stem cells. Cell. Stem Cell.10 (1), 47–62 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tavares, L. et al. RYBP-PRC1 complexes mediate H2A ubiquitylation at polycomb target sites independently of PRC2 and H3K27me3. Cell148 (4), 664–678 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ku, M. et al. Genomewide analysis of PRC1 and PRC2 occupancy identifies two classes of bivalent domains. PLoS Genet.4 (10), e1000242 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee, T. I. et al. Control of developmental regulators by polycomb in human embryonic stem cells. Cell125 (2), 301–313 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boyer, L. A. et al. Polycomb complexes repress developmental regulators in murine embryonic stem cells. Nature441 (7091), 349–353 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Torchy, M. P., Hamiche, A. & Klaholz, B. P. Structure and function insights into the NuRD chromatin remodeling complex. Cell. Mol. Life Sci.72 (13), 2491–2507 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bode, D., Yu, L., Tate, P. & Pardo, M. Characterization of two distinct nucleosome remodeling and deacetylase (NuRD) complex assemblies in embryonic stem cells. Mol. Cell. Proteom.15 (3), 878–891 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burgold, T. et al. The nucleosome remodelling and deacetylation complex suppresses transcriptional noise during lineage commitment. EMBO J.38 (12), e100788 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lai, A. Y. & Wade, P. A. Cancer biology and nurd: a multifaceted chromatin remodelling complex. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 11 (8), 588–596 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Denslow, S. A. & Wade, P. A. The human Mi-2/NuRD complex and gene regulation. Oncogene26 (37), 5433–5438 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hu, G. & Wade, P. A. NuRD and pluripotency: a complex balancing act. Cell. Stem Cell.10 (5), 497–503 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reynolds, N. et al. NuRD-mediated deacetylation of H3K27 facilitates recruitment of polycomb repressive complex 2 to direct gene repression. Embo J.31 (3), 593–605 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reynolds, N. et al. NuRD suppresses pluripotency gene expression to promote transcriptional heterogeneity and lineage commitment. Cell. Stem Cell.10 (5), 583–594 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schuettengruber, B., Bourbon, H. M., Di Croce, L. & Cavalli, G. Genome regulation by polycomb and trithorax: 70 years and counting. Cell171 (1), 34–57 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gatchalian, J. et al. A non-canonical BRD9-containing BAF chromatin remodeling complex regulates Naive pluripotency in mouse embryonic stem cells. Nat. Commun.9 (1), 5139 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kadoch, C. et al. Dynamics of BAF-Polycomb complex opposition on heterochromatin in normal and oncogenic States. Nat. Genet.49 (2), 213–222 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nakayama, R. T. & Pulice, J. L. SMARCB1 is required for widespread BAF complex-mediated activation of enhancers and bivalent promoters. Nat. Genet.49 (11), 1613–1623 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yildirim, O. et al. Mbd3/NURD complex regulates expression of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine marked genes in embryonic stem cells. Cell147 (7), 1498–1510 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hainer, S. J. et al. Suppression of pervasive noncoding transcription in embryonic stem cells by EsBAF. Genes Dev.29 (4), 362–378 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bracken, A. P., Brien, G. L. & Verrijzer, C. P. Dangerous liaisons: interplay between SWI/SNF, nurd, and polycomb in chromatin regulation and cancer. Genes Dev.33, 15–16 (2019). 936 – 59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Villasante, A. et al. Epigenetic regulation of Nanog expression by Ezh2 in pluripotent stem cells. Cell. Cycle. 10 (9), 1488–1498 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ji, J., Cao, J., Chen, P., Huang, R. & Ye, S. D. Inhibition of protein kinase C increases Prdm14 level to promote self-renewal of embryonic stem cells through reducing Suv39h-induced H3K9 methylation. J. Biol. Chem.300 (3), 105714 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pieles, O. & Morsczeck, C. The role of protein kinase C during the differentiation of stem and precursor cells into tissue cells. Biomedicines12 (12), 2735 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rajendran, G. et al. Inhibition of protein kinase C signaling maintains rat embryonic stem cell pluripotency. J. Biol. Chem.288 (34), 24351–24362 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dutta, D. et al. Self-renewal versus lineage commitment of embryonic stem cells: protein kinase C signaling shifts the balance. Stem Cells. 29 (4), 618–628 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang, J., Xiao, B., Kimura, E., Mongan, M. & Xia, Y. The combined effects of Map3k1 mutation and Dioxin on differentiation of keratinocytes derived from mouse embryonic stem cells. Sci. Rep.12 (1), 11482 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oyama, H., Nukuda, A., Ishihara, S. & Haga, H. Soft surfaces promote astrocytic differentiation of mouse embryonic neural stem cells via dephosphorylation of MRLC in the absence of serum. Sci. Rep.11 (1), 19574 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ye, C. et al. DRUG-seq for miniaturized high-throughput transcriptome profiling in drug discovery. Nat. Commun.9 (1), 4307 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen, S., Zhou, Y., Chen, Y. & Gu, J. Fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics34 (17), i884–i90 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu, T. et al. ClusterProfiler 4.0: A universal enrichment tool for interpreting omics data. Innov. (Camb). 2 (3), 100141 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Laugesen, A. & Helin, K. Chromatin repressive complexes in stem cells, development, and cancer. Cell. Stem Cell.14 (6), 735–751 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Endoh, M. et al. Polycomb group proteins Ring1A/B are functionally linked to the core transcriptional regulatory circuitry to maintain ES cell identity. Development135 (8), 1513–1524 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kaji, K. et al. The NuRD component Mbd3 is required for pluripotency of embryonic stem cells. Nat. Cell. Biol.8 (3), 285–292 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Eskeland, R. et al. Ring1B compacts chromatin structure and represses gene expression independent of histone ubiquitination. Mol. Cell.38 (3), 452–464 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tong, J. K., Hassig, C. A., Schnitzler, G. R., Kingston, R. E. & Schreiber, S. L. Chromatin deacetylation by an ATP-dependent nucleosome remodelling complex. Nature395 (6705), 917–921 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Allen, H. F., Wade, P. A. & Kutateladze, T. G. The NuRD architecture. Cell. Mol. Life Sci.70 (19), 3513–3524 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shen, X. et al. EZH1 mediates methylation on histone H3 lysine 27 and complements EZH2 in maintaining stem cell identity and executing pluripotency. Mol. Cell.32 (4), 491–502 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Guo, Y. & Wang, G. G. Modulation of the high-order chromatin structure by polycomb complexes. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol.10, 1021658 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhao, Y. et al. Coordination of EZH2 and SOX2 specifies human neural fate decision. Cell. Regen. 10 (1), 30 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Huang, X. J. et al. EZH2 is essential for development of mouse preimplantation embryos. Reprod. Fertil. Dev.26 (8), 1166–1175 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kashyap, V. et al. Regulation of stem cell pluripotency and differentiation involves a mutual regulatory circuit of the NANOG, OCT4, and SOX2 pluripotency transcription factors with polycomb repressive complexes and stem cell MicroRNAs. Stem Cells Dev.18 (7), 1093–1108 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang, J. et al. A protein interaction network for pluripotency of embryonic stem cells. Nature444 (7117), 364–368 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kim, J., Chu, J., Shen, X., Wang, J. & Orkin, S. H. An extended transcriptional network for pluripotency of embryonic stem cells. Cell132 (6), 1049–1061 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Desai, D., Khanna, A. & Pethe, P. PRC1 catalytic unit RING1B regulates early neural differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells. Exp. Cell. Res.396 (1), 112294 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang, Y., LeRoy, G., Seelig, H. P., Lane, W. S. & Reinberg, D. The dermatomyositis-specific autoantigen Mi2 is a component of a complex containing histone deacetylase and nucleosome remodeling activities. Cell95 (2), 279–289 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Xue, Y. et al. NURD, a novel complex with both ATP-dependent chromatin-remodeling and histone deacetylase activities. Mol. Cell.2 (6), 851–861 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Morey, L. et al. MBD3, a component of the NuRD complex, facilitates chromatin alteration and deposition of epigenetic marks. Mol. Cell. Biol.28 (19), 5912–5923 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.van den Berg, D. L. C. et al. An Oct4-centered protein interaction network in embryonic stem cells. Cell. Stem Cell.6 (4), 369–381 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pardo, M. et al. An expanded Oct4 interaction network: implications for stem cell biology, development, and disease. Cell. Stem Cell.6 (4), 382–395 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sparmann, A. et al. The chromodomain helicase Chd4 is required for Polycomb-mediated Inhibition of astroglial differentiation. Embo J.32 (11), 1598–1612 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chen, T. et al. The genome sequence archive family: toward explosive data growth and diverse data types. Genomics Proteom. Bioinf.19 (4), 578–583 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Xue, Y. et al. Database resources of the National genomics data center, China National center for bioinformation in 2022. Nucleic Acids Res.50 (D1), D27–d38 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files. Additional information can be found in the Supplementary Information section. This section includes the full-length / uncropped blots. The raw sequencedata reported in this paper have been deposited in the Genome Sequence Archive71 in National Genomics Data Center72, China National Center forBioinformation / Beijing Institute of Genomics, Chinese Academy of Sciences (GSA: CRA026207) that are publicly accessible athttps://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa.