Abstract

Smart cities’ have experienced an increasingly higher rate of urbanization and increase of the population leading to strengthening the pressing needs in waste management. In this paper, we present an intelligent waste classification system that utilises Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) for automatic segregation into twelve categories of waste, employing image data. The model is trained on 15,535 images from a publicly available dataset using preprocessing and data augmentation to increase generalisation and mitigate class imbalance. A performance comparison in terms of precision, recall, F1 score, and accuracy shows that the proposed ResNet-based model yields a classification accuracy of 98.16%, outperforming previous work on conventional deep learning architectures. Experimental results demonstrate that the model is a robust framework for handling various types of waste (organic, recyclable, and hazardous) and is a very general model, as confirmed by cross-validation and real-world tests. The proposed system demonstrates great promise for upscaling in automatic waste management towards long-term urban sustainability, improved recycling, and reduced environmental threats.

Keywords: Green technologies, Smart city, Waste classification, Waste management, Deep- learning

Subject terms: Environmental social sciences, Energy science and technology, Engineering

Introduction

One of the pressing global issues is waste, as accelerated urbanisation and population growth have led to increased waste generation. The world’s waste is expected to more than double to 3.4 billion tons a year by 2050, with most of it being generated in developing countries that lack the infrastructure to recycle waste and instead divert resources into collecting it. Proper waste management (recycling, waste-to-energy etc.) is environmentally, economically, and health beneficial, but it needs to be combined with policies, technology and finance1. The improper management of waste significantly contributes to environmental pollution, including the emission of greenhouse gases, soil contamination, and the spread of diseases resulting from the accumulation of waste in urban areas. Many cities still rely on traditional waste disposal methods such as open dumping, incineration, and landfilling, as shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Unattended waste in water, roads, and ground across cities.

Increasing amounts of waste lead to health and environmental hazards due to poor recycling practices. Rapid increases in waste generation around the world have brought with them pressing environmental and public health issues stemming from excessive waste that is often disposed of unsafely, releasing harmful pollutants. Current waste sorting methods are inaccurate, and in real-time, services are too expensive, necessitating an intelligent, automated solution. An innovative deep learning and IoT-enabled intelligent waste management service to cater for these inadequacies and enable accurate, real-time waste sorting2.

Smart waste management is becoming a strategic priority for local municipalities in their efforts to minimise the amount of municipal solid waste and increase recycling rates. Although cities incur high costs in managing public waste, ‘smart’ solutions are seen to hold great prospects for enhancing operational efficiency3. Environmental pollution is increasingly worsening in developing countries like Pakistan due to rapid urbanisation, population growth, industrialisation, and a lack of municipal waste infrastructure. A Sound waste composition analysis is essential as a tool for sustainable planning and resource mobilisation, which can help achieve efficient MSWM4. The environmental and public health implications of landfilling are illustrated in Fig. 2, which shows how open dumping has the potential to pollute the air, soil, and water, thereby endangering the health of nearby urban communities.

Fig. 2.

Different impacts of landfills in waste management.

Current practice in most developing countries indicates a generally poor waste management system that leads to adverse environmental conditions. As shown in Fig. 3, burning is a form of waste disposal that produces noxious substances, which are emitted into the atmosphere, contributing to the overall degradation of air and to health problems , such as respiratory illnesses and heart diseases. It also produces toxic byproducts that seep into the soil and local water sources, thereby further contributing to environmental pollution.

Fig. 3.

Sample of burning waste.

Most municipal waste is disposed of through incineration, open dumping, or landfilling, often in locations that are not adequately designated for waste disposal5. Waste generation is closely linked to income level and the rate of urbanization, which further complicates waste management efforts. Inadequate technology, poor urban planning, bureaucratic obstacles, and a lack of public awareness hinder effective waste handling. In many urban areas, uncollected waste-clogged drains create stagnant water pools and attract disease-carrying insects, further exacerbating health hazards. Most collected waste is dumped in pits, ponds, rivers, and agricultural fields due to a lack of proper disposal sites6,7.

The growing potential of biorefinery technologies to convert organic solid wastes into high-value biobased products promotes sustainable waste management and resource recovery in urban environments8. Waste can also be classified as any non-liquid or non-gaseous byproduct of human activity that has the potential to impact the environment negatively. In this context, the term “solid waste” is used comprehensively to refer to the mixture of refuse discarded by urban communities and the more homogeneous waste generated from agricultural, industrial, and miner activities9.

The concept of a smart city, as shown in Fig. 4, represents the integration of technological advancements within urban environments to create a foundation for sustainable living. One of the primary areas of focus in this integration is waste management, where efficient and innovative solutions are being developed to address the growing challenges related to waste.

Fig. 4.

Different type of waste generated in a smart city.

Introducing smart waste management systems aligns with the broader vision of sustainable cities. The Internet of Things (IoT) has enabled the development of smart devices such as radio-frequency identification (RFID) tags and sensors that collect city-wide data, leading to improved waste monitoring and collection processes. A smart city utilises IoT and various information and communication technologies (ICT) to optimise public space management and urban services while enhancing sustainability10. Dual-layer Multi-Queue Adaptive Priority Scheduling (MQAPS) algorithm for efficient task execution. By dynamically adjusting time slices and prioritising tasks based on real-time criteria, MQAPS outperforms traditional RR and multi-level scheduling in terms of CPU utilisation, fairness, and execution efficiency11.

Waste materials encompass a wide range of substances, including food waste, industrial waste, plastic waste, radioactive waste, sewage waste, electronic waste, and more. If not systematically managed, such waste poses a significant environmental threat12. Current waste classification methods rely on various processes, including landfilling, compaction, and incineration. However, these methods are inefficient and fail to optimize the reuse and recycling of valuable materials.

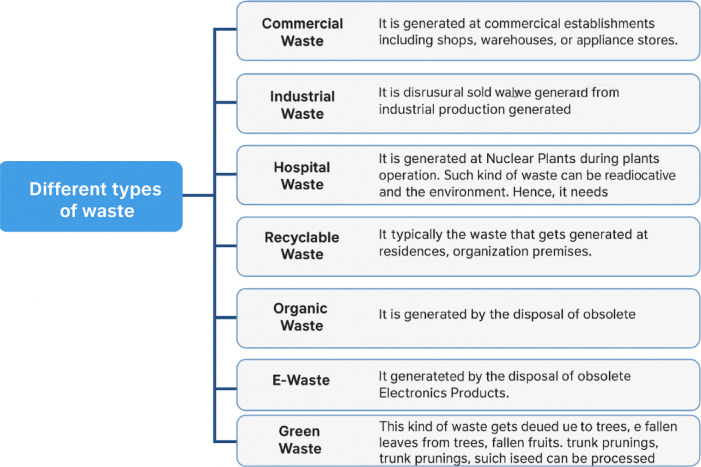

Figure 5 presents a flowchart outlining the different types of waste, including commercial, industrial, hospital, nuclear, recyclable, organic, e-waste, and green waste. Each category is briefly described, highlighting its source and potential environmental or health impacts.

Fig. 5.

Different types of waste.

Manual waste sorting remains labour-intensive, prone to human error, and highly inefficient, particularly when dealing with large volumes of waste. Alternative sensor-based approaches, such as spectroscopy and RFID scanning, have been explored; however, they are expensive and challenging to scale for real-world applications. An advanced and automated waste classification system is crucial to achieving sustainable waste management goals.

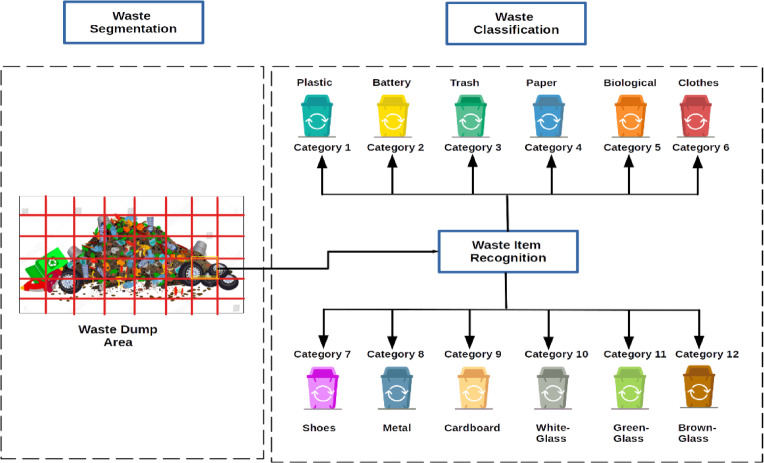

This study aims to bridge these gaps by proposing a CNN-based waste classification model optimized for improved accuracy and robustness. By incorporating techniques such as data augmentation and transfer learning, this research seeks to enhance the performance of waste classification models, particularly in environments where labelled datasets are scarce. Additionally, this study evaluates the effectiveness of CNN-based classification in real-world scenarios, highlighting its potential for integration into smart city waste management frameworks. As shown in Fig. 6, effective waste classification is crucial for ensuring proper disposal, recycling, and waste-to-energy conversion.

Fig. 6.

Waste categories.

A hierarchical classification of waste helps increase recovery by assigning each waste flow to either recycling/reutilization or final disposal options, thereby saving on land usage and minimising environmental impact. The classification of materials in twelve categories is in accordance with regular data sets, which also facilitates AI-based waste recognition with accurate labelling. This is also demonstrated in Fig. 7, where good sorting, depending on material properties, is an absolute prerequisite to achieve a high recycling degree and a high level of waste recovery.

Fig. 7.

Segmentation and classification mechanism.

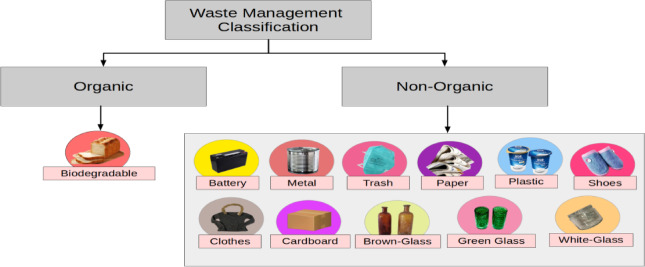

Organic waste includes degradable materials such as food waste, garden waste, and other decomposable substances. Good management of organic waste with composting or bio-energy production greatly reduces methane from dumps. Organic waste, however, is subdivided into 11 sub-categories, thereby promoting a systematic recycling process. These subtypes include paper and cardboard (newspapers, magazines, office paper, and cardboard); metal (aluminium cans, steel tins, and ferrous scrap metal); and plastic (PET bottles and plastic bags), as illustrated in Fig. 8.

Fig. 8.

Classification of waste: organic vs. non-organic.

Literature review

Recent progress in smart waste sorting has proposed deep hybrid models for waste categorization in mixed urban waste disposal context. WasteIQNet, a deep learning framework that is aware of the hierarchical structure, fuses MobileNetV3 and GraphSAGE to achieve fine-grained waste categorization with image-level supervision. Through being equipped with methods including Feature-wise Attention, TopK-MoE, and Hierarchical Tree Loss, the model achieves more accurate and stronger generalization ability on the real datasets, such as WEDR13.

Recent research has investigated the combination of mIoT platforms and deep learning models for providing automated and optimised waste material recovery. The WMR-DL approach achieves higher sorting accuracy and real-time monitoring using IoT sensors and a DL-based classifier, leading to a significant increase in the recovery rate. This method overcomes many of the deficiencies of manual waste destruction, enabling scalable and environmentally friendly waste management solutions14.

Solid waste management has become a pressing global issue. The rapid increase in waste production is a critical concern, particularly in developing countries, due to population growth, rural-to-urban migration, larger family sizes, rapid urbanisation, and rising living standards in communities15. Automatic classification of urban litter is a challenging task due to the increasing problem of urban litter. Indeed, findings in recent studies suggest that tuning the architecture of standard deep learning models, such as CNNs, and popular models designed to address state-of-the-art classification problems, including DenseNet-169 and EfficientNet-V2-S, leads to improved classification performance. Fine-tuned models achieved 96.42% accuracy, a promising result for the high scalability of waste management automation16.

The latest progress in AI-based waste management also demonstrates that fused deep learning models with Multi-Criteria Decision Making (MCDM) methods are efficient. For a two-slice intelligent system with Inception-Xception-type models, a 98% waste classification was achieved for numerous categories. The fusion rules and the MCDM method, such as VIKOR, can facilitate robust model selection for more efficient urban waste sorting17.

Huh et al. explored intelligent waste sorting technologies based on smart waste containers with sensors, vision recognition, and spectroscopy18.

Producer Responsibility Organisations (PROs) are key actors in sustainable e-waste management, but they suffer from a variety of operational problems. A recent study, based on the DEMATEL method, identified nine important barriers at the Indian level with respect to KIBS innovation. The paper underscored the significance of knowledge-sharing platforms, stakeholder partnerships, and monitoring mechanisms. These findings can inform the development of effective policies for sustainable E-waste management19.

CNN-GRU hybrid model for short-term load forecasting using AEP and ISONE datasets. The model effectively captures multi-scale spatiotemporal patterns and achieves superior accuracy with the lowest MAE, RMSE, and MAPE across both single- and multi-step forecasts20. Another widely used method is RFID-based waste management, which utilises radio-frequency identification (RFID) for real-time waste categorisation21. Fang et al. proposed integrating artificial intelligence (AI) into waste management to optimise critical processes, including waste sorting, logistics, hazardous waste handling, and resource recovery22.

Recent developments in waste sorting utilise hyperspectral imagery and real-time analysis to surpass the limitations of RGB-based technologies. Note: The new system runs from 900 to 1800 nm for robust identification of difficult materials, such as plastics and fabrics. By utilising automated pseudo-label and model optimisation methods, we have achieved a promising F1-score of 71% on a dynamic conveyor belt, demonstrating potential for scalable industrial applications23.

In Kazakhstan, increasing MSW generation and low recycling rates have brought severe environmental problems, largely attributable to high levels of methane release. Recent analysis of the physicochemical and calorific properties of municipal solid waste (MSW) from six major cities generated standardised information on assessing waste-to-energy potential. Such results contribute to the design of effective treatment technologies based on the sorting efficiency and characteristics of thermal treatment24.

As environmental issues become increasingly important, computer vision is an effective method for auto-classifying waste and replacing manual work from the past era. In a recent study in Saudi Arabia, it was found that transferred CNN models (e.g., ResNet50V2 and MobileNetV2) can achieve 98.95% accuracy in garbage recognition. These innovations significantly enhance both recycling performance and sustainable waste disposal25.

Smart city development and waste management have overlapped and emerged as a central theme in sustainability literature. A systematic review of 1,768 recently published papers reveals new trends in urban waste systems , including digitalisation, energy recovery, and policy innovation. These findings highlight the need for technology-enabled, integrated strategies to advance sustainable urban living and circular economy practices26.

In a recent investigation, attention is shifting towards a multi-layer smart city-wide architecture (i.e., perception, edge, network, cloud, and application layers) to improve waste management. IoT devices enable real-time data acquisition, while edge computing and cloud storage are utilised for effective processing and analytics. Additionally, federated learning improves the accuracy of waste classification while maintaining data privacy27.

More complex smart city architectures, which extend to ICT services, enable automation and optimisation in waste management, but in doing so also bring to light new threats regarding cybersecurity. Attackers can manipulate AI models by poisoning them with deceptive “waste” images , resulting in incorrect categorisation. At the network level, we are facing denial-of-service (DoS) attacks that can disrupt IoT-based monitoring, as well as data tampering and unauthorised access, which could undermine the tracking systems. To mitigate these drawbacks, several researchers have also presented solutions on blockchain for secure, transparent, and tamper-proof waste logs28.

In addition to waste classification, there has been significant progress in optimising renewable energy performance driven by deep learning (DL) and machine learning (ML), complementing sustainable waste management aspirations. ML contributes to decision-making in the fields of smart home energy optimisation, energy requirement forecasts, and smart grid management. The development of deep neural network (DNN) architectures and their large-scale optimisation have provided higher accuracy predictions for renewable energy forecasting and allocation29. The inclusion of meteorological variables and Scheduling features improves the model’s performance, which is beneficial for WtE systems, as climatic factors significantly influence energy recovery efficiency30. Moreover, the energy usage is reduced and waste is minimized by the ML-based smart home energy management systems31. These smart systems are capable of making real-time adaptations to the changing volume of waste generation and power demand.

Despite this progress, some significant challenges remain. First, most AI models for waste classification are constrained by small and unbalanced datasets, which can lead to overfitting and reduced generalisation. Secondly, since waste appearances can be variable according to material composition, contamination, and deformation, there are many misclassification outputs. Third, the computational cost of many deep learning (DL) models is too high to be deployed in real-time edge environments. Fourthly, AI-based waste identification is poorly secured. To address these restrictions, advanced data augmentation, lightweight AI models suitable for edge computing, and blockchain-based frameworks for secure and transparent waste tracking are part of ongoing research32.

Meanwhile, remanufacturing has become a sustainable approach to environmental protection and cost savings. The most recent models suggest that remanufacturing intermediate (used but not yet at end-of-life) products leads to earlier adoption, higher secondary market value, and higher profits and consumer surplus compared to end-of-life (EOL) remanufacturing33.

In a different field, a new Trustworthy Multi-Focus Fusion (TMFF) structure has been developed for real-time interpretation of sewer videos. The system utilises a focal segment module (FSM), evidential deep learning (EDL), and expert fusion to enhance the performance of defect detection and disambiguation. Experiments on the VideoPipe dataset validate the superiority and resistance to unknown anomalies of TMFF34.

In the context of climate change and ecological disruption, the application of AI for achieving carbon neutrality is becoming a focus. Multimodal AI systems, such as ALBEF, offer combined vision and text capabilities for service models, providing a comprehensive ability for environmental surveillance and informed decision support. Such technologies enable detailed scene understanding and offer scalable routes to addressing global sustainability targets35.

To address the class imbalance and reduce the waste of computer power in detection, a deep convolutional neural network (DCNN) combined with an AdaBoost ensemble, along with a new Binomial Crossover Ship Rescue Algorithm (BCSRA) approach for hyperparameter tuning, is presented in this paper. The proposed model outperforms existing methods with 98.56% accuracy and 98.82% precision. The experiments’ results confirm that this approach can be practical for early waste identification and accurate waste separation, ensuring that the waste generated is addressed sustainably36.

Table 1 presents common types of attacks targeting different IoT layers in smart waste management systems, along with solutions proposed in recent literature.

Table 1.

IoT Layer-wise attacks and proposed solutions in smart waste Management.

| IoT layer | Type of attacks | Proposed solutions | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perception layer |

Node capture Fake node injection Sensor jamming |

RFID-based authentication Sensor calibration Use of secure sensor nodes |

10,20,21,27 |

| Network layer |

Data interception Routing attacks (e.g., sinkhole, blackhole) |

Federated learning to enhance privacy Encrypted communication protocols |

12,27,36 |

| Application layer |

Unauthorized access Malware injection Data tampering |

Deep learning-based anomaly detection Secure APIs Role-based access |

15,18,24 |

| Middleware layer |

Man-in-the-middle attacks Insecure interfaces |

Blockchain integration Secure middleware platforms with AI-enabled authentication |

22,25,35 |

| Data processing layer |

Data poisoning Model inversion attacks |

Federated learning Trust-aware data fusion Model validation |

9,27,34 |

Research gap and motivation

The goal of this research is to design an automated waste sorting and segregation model that segregates waste into organic, non-organic, biodegradable, and non-biodegradable categories using image classification techniques. This research aims to develop a smart and cost-effective solution to reduce waste production by ensuring the proper disposal, recycling, and reuse of discarded products. Although applied research has led to significant progress in AI-based waste classification, at least two main challenges remain unsolved in the state-of-the-art. Most current models are based on unbalanced, non-diversified, and/or impractical datasets, resulting in poor applicability of the models in different urban systems. Furthermore, objects with similar visual appearances (e.g., glass or different types of plastics) are still often misclassified, particularly when the quality of the input features is poor due to occlusions or contaminations. Moreover, in many cases, models are too complex to be run in real-time, which is a deal-breaker for smart bins and embedded systems. Only a few works have effectively investigated lightweight, scalable, and adaptive CNN architectures tuned for both accuracy and efficiency at inference. Hence, the demand for intelligent waste classification models is urgent for the accurate, robust, computationally efficient, and scalable implementation of a smart city.

Methods

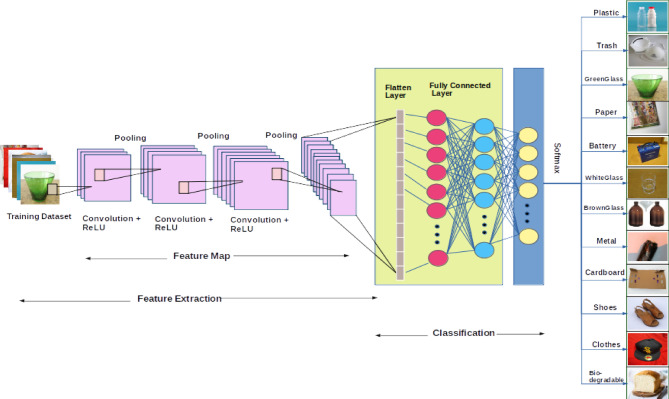

This research utilises a Convolutional Neural Network to automate waste segregation, a process commonly performed manually into predefined categories, including plastic, metal, glass, paper, and biodegradable materials. Several studies proposed different approaches; however, no study claimed 100% accuracy. The system’s architecture involves two key components: feature extraction and classification. In the feature extraction stage, the CNN processes input waste images through layers of is convolution and pooling to identify key characteristics. These feature maps are then flattened and passed through fully connected layers, ultimately yielding classification results via a softmax layer. Each category corresponds to a specific type of waste, ensuring accurate segregation based on learned patterns.

CNNs are the most commonly used networks in Image Recognition tasks. It had an impact on the human visual system. A fundamental CNN layout is demonstrated in Fig. 9 for simple pattern. It consists of the following layers: an input layer and an output layer, a convolution layer, a pooling layer, and a fully connected layer. This describes the utilisation of the CNN layer and the status of feature analysis.

Fig. 9.

Architecture of CNN of proposed model.

The rationale for selecting CNN over other models is based on multiple factors. Traditional machine learning models, such as Support Vector Machines (SVM), Random Forests, and Decision Trees, rely on handcrafted features, which makes them less effective in handling variations in lighting, object occlusion, and background noise.

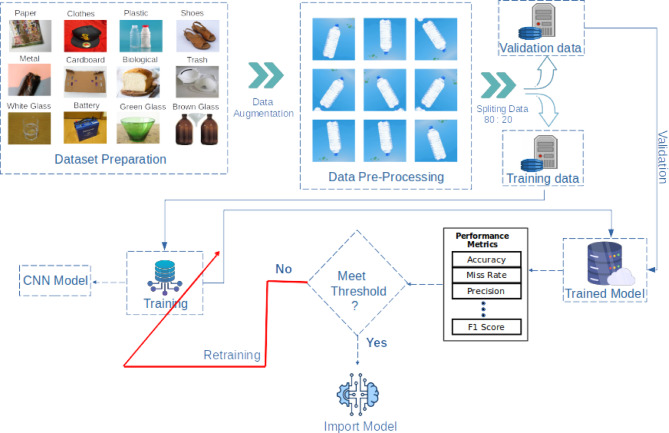

The proposed methodology, as shown in Fig. 10, begins with dataset preparation, where labelled images of waste categories are collected and organised. The dataset is split into subsets for training (80%) and validation (20%) to train and evaluate the model. To enhance image clarity and reduce noise, the Adaptive Gaussian Bilateral Filter (AGBF) is applied, which smooths images while preserving edges, improving feature extraction for classification. Preprocessing ensures uniformity in training, avoiding computational inefficiencies. Data augmentation techniques, including random flipping (vertical and horizontal) and random rotation, are also applied to expand the dataset and improve model robustness artificially. Figures 9 and 10 have been updated to illustrate the CNN architecture and model training flow with detailed layer-wise specifications, including kernel sizes, strides, padding, number of filters, and activation functions used at each stage, to provide a clearer understanding of the network configuration.

Fig. 10.

Training flow of the proposed model.

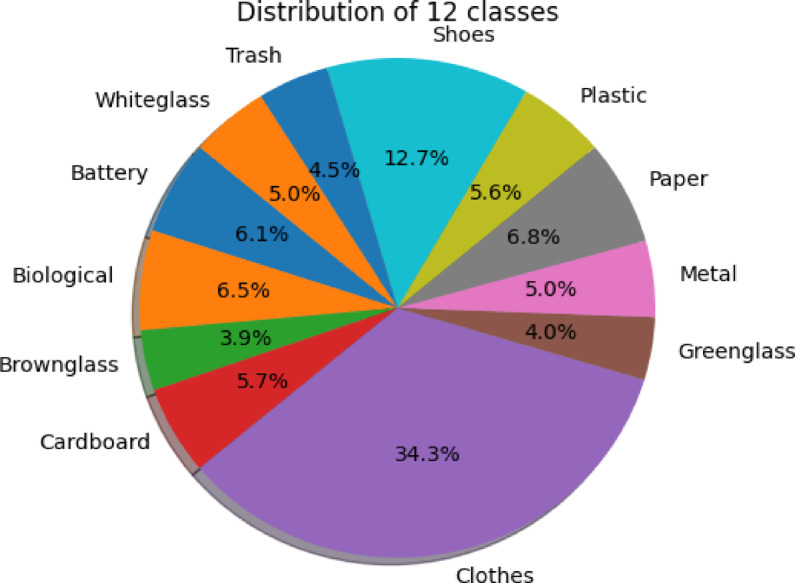

The proposed model is evaluated on a benchmark garbage classification dataset from the publicly accessible Kaggle repository, utilising Python 3.6.5. The dataset contains Twelve different classes of waste. It consists of 15,535 images of garbage objects that may be part of domestic waste, either non-organic or organic. Battery has 945 images, Biological has 1005 images, Brown-Glass has 607 images, cardboard has 891 images, Clothes has 5325 images, Green-Glass has 629 images, metal has 769 images, paper has 1050 images, plastic has 865 images, Shoes has 1977 images, Trash has 697 images, and White-glass has 755 images. The visual representation of the 12 classes of waste dataset distribution is shown in the form of a pie chart in Fig. 11.

Fig. 11.

Distribution of 12 types of waste.

One challenge encountered in dataset preparation is class imbalance, where certain categories (e.g., Clothes and Shoes) have significantly more samples than others (e.g., Brown Glass and Trash). To mitigate this, oversampling techniques such as Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE) and weighted loss functions were applied to ensure that minority classes received equal representation during training.

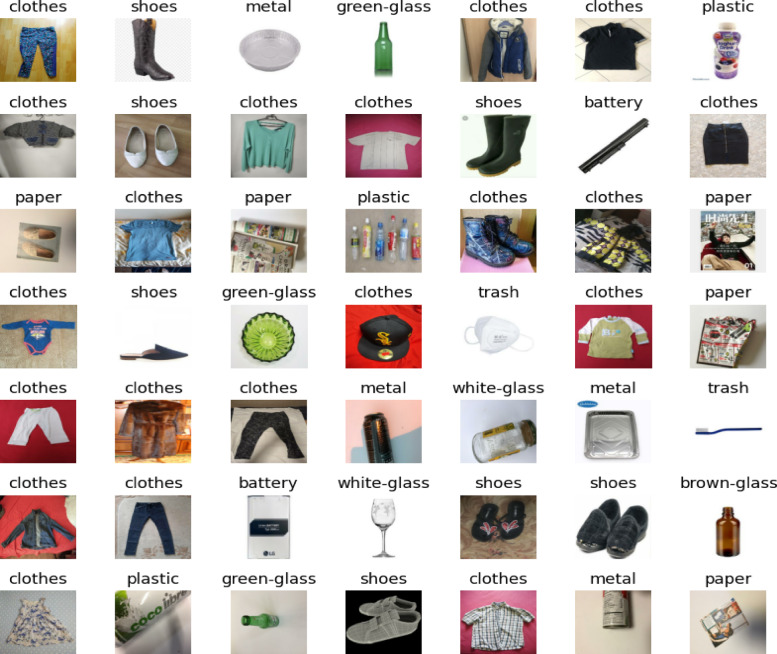

Sample test images from the Kaggle dataset, as used for training, are shown in Fig. 12. These images represent diverse lighting conditions, object orientations, and backgrounds, ensuring that the model learns to generalize across various environmental factors.

Fig. 12.

Sample dataset images.

Data augmentation refers to artificially increasing the size and diversity of a dataset by applying various transformations to pre-existing images. A waste classification dataset with 12 classes involves modifying the original images to create new, altered versions while preserving the original class label. Here, we employ two data augmentation techniques: random flipping, which includes vertical and horizontal flipping, and random rotation. Here are sample images from augmentation, as shown in Fig. 13.

Fig. 13.

Augmentation of cardboard class of waste category.

Techniques were employed to enhance the generalisation of the CNN model to unseen data, including fine-tuning, transfer learning, and hyperparameter optimisation. Fine-tuning was performed by initializing the CNN with pre-trained weights from a large-scale image classification dataset (ImageNet), allowing the model to leverage pre-learned feature representations for improved accuracy. Transfer learning enabled faster convergence, reducing the number of required training epochs.The dataset is divided into two sections: one for training purposes (i.e., 80% of the dataset) and the other for testing purposes (i.e., 20% of the dataset). Hyperparameter optimisation was conducted using both grid search and Bayesian optimisation, exploring various combinations of learning rates, dropout rates, and batch sizes. Before training the model, all the images were resized to 180 × 180 × 3. The CNN model was then trained using 80% of a dataset with 150 epochs. 20% of the dataset is used to test the model’s validity. If the accuracy measure required for model validation does not meet the threshold value, the model is retrained until it achieves the acceptable threshold value. The resulting model is then considered the final one for further processing.

Results

The performance of the proposed CNN-based waste classification model was evaluated using standard accuracy metrics, including True Positive Rate (TPR), True Negative Rate (TNR), False Negative Rate (FNR), and Precision. The confusion matrix was used to compute these metrics, as shown in Table 2. The confusion matrix provides essential statistics to evaluate the classification accuracy across twelve waste categories, showing the number of correctly and incorrectly classified waste items. The model’s accuracy is calculated as the ratio of correctly classified waste objects (true positives and true negatives) to the total number of test samples. The model also considers false-negative rate (FNR), sensitivity (TPR), false-positive rate (FPR), and precision (PPV) to assess classification effectiveness. The F1-score balances precision and recall, serving as an additional key metric to evaluate overall performance.

Table 2.

Accuracy metrics.

| Predicted | Actual | ||

| Positive | Negative | ||

| Positive | True positive (TP) | False positive (FP) | |

| Negative | False negative (FN) | True negative (TN) | |

Accuracy measures the proportion of correctly classified instances (both true positives (TP) and true negatives (TN)) out of the total samples.

| 1 |

The error rate represents the fraction of misclassified instances, including both false positives (FP) and false negatives (FN), relative to the total predictions.

| 2 |

The False Negative Rate (FNR), also known as the miss rate, measures the proportion of positive samples that are incorrectly classified as negative.

| 3 |

True Positive Rate (TPR), also known as recall or sensitivity, measures the model’s effectiveness in identifying actual positive samples.

| 4 |

The False Positive Rate (FPR) represents the proportion of negative samples that are incorrectly classified as positive.

| 5 |

Precision quantifies the accuracy of the predicted positive classifications.

| 6 |

The Negative Predictive Value (NPV) calculates the proportion of correctly identified negative cases among all predicted negatives.

| 7 |

The F1-score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall (TPR), balancing false positives and false negatives.

| 8 |

The figure described that the methodology has identified 141 images were classified as battery, 147 as biological, 88 as brown-glass, 131 as cardboard, 155 as clothing, 94 as green-glass, 112 as metal, 155 as paper, 122 as plastic, 155 as shoes, 111 as white-glass, and 105 as trash.

The confusion matrix in Table 3 illustrates the performance of the waste classification system across 12 categories, showing strong overall accuracy. Most items were correctly classified, with high precision in categories like clothes, paper, and shoes, which each achieved 155 correct classifications. Minor misclassifications occurred, such as brown glass being mistaken for biological and some confusion between similar materials like white glass and green glass. Despite these minor errors, the system distinguished visually and contextually different waste types, demonstrating its effectiveness for waste management applications.

Table 3.

Confusion matrix.

| Actual | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 1546 | Battery | Biological | Brown glass | Cardboard | Clothes | Green glass | Metal | Paper | Plastic | Shoes | Trash | White glass | |

| Predicted | Battery | 141 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Biological | 0 | 147 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Brown Glass | 0 | 1 | 88 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Cardboard | 0 | 0 | 0 | 131 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Clothes | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 155 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| Green Glass | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 94 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Metal | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 112 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Paper | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 155 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Plastic | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 122 | 0 | 0 | 3 | |

| Shoes | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 155 | 1 | 0 | |

| Trash | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 105 | 0 | |

| White Glass | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 111 | |

The waste classification management system results, implemented using a CNN-based AI agent in MATLAB, demonstrate that ResNet is the most effective algorithm among those tested. ResNet achieved the highest accuracy at 98.0595%, along with the best precision (97.9764%), recall (98.0158%), and F1-score (97.9875%), making it the top-performing model for this task. Additionally, it recorded the lowest miss rate (1.9405%), indicating fewer classification errors compared to the other algorithms. Clothes, Paper, Shoes, and Trash each achieved 155 correct predictions, showing near-perfect classification. White Glass had 111 correct, but was misclassified 5 times (once as Brown Glass, twice as Metal, and twice as Plastic).

Although the proposed model for CNN-based waste classification achieved a high accuracy rate of approximately 98.16% during validation, a careful examination of the confusion matrix reveals trends in misclassification. An interesting trend is the mismatch of glass types (white, green, and brown) with transparent plastic. This variation occurs because these materials have similar reflective properties and are transparent, making them visually indistinguishable using regular RGB image classification methods. In some instances, transparent plastic bottles were incorrectly classified as glass bottles, demonstrating that the model tends to rely on shape and colour features without learning about material texture or reflectivity.

Another common trend with misclassification was observed with paper and cardboard, where some print media and crushed boxes were misclassified as each other. This is probably because their surface textures and colour patterns are similar, particularly when lighting conditions or occlusions obscure differentiating features. Related to that, background noise and waste items overlap , leading to a few classification errors. A paper sheet partially covering a plastic wrapper was also classified as a paper object, indicating that object segmentation needs improvement.

Hybrid deep learning models may be preferable since they can help to recover features specifically required to discriminate materials through attention mechanisms. Additionally, multimodal learning approaches (for instance, infrared or hyperspectral imaging) can contain extra spectral information that could enable the model to distinguish more accurately between plastic and glass. These improvements would make the system more robust and enable it to adapt to the various scenarios encountered in real-world waste classification.

Table 4 presents a comparative analysis of various deep learning models for waste segregation. The ResNet model outperforms others, achieving the highest accuracy (98.06%) and F1-score (97.99%), while SqueezeNet exhibits the lowest performance across all metrics.

Table 4.

Accuracy analysis of waste segregation techniques using different methods.

| Methods | Accuracy (%) | Miss rate (%) (1- accuracy) |

Precision (%) |

Recall (%) |

F1-Score (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ResNet | 98.0595% | 1.9405% | 97.9764% | 98.0158% | 97.9875% |

| AlexNet | 96.5071% | 3.4929% | 96.46% | 96.372% | 96.372% |

| VGG16 | 95.2135% | 4.7865% | 95.665% | 95.98% | 95.74% |

| GoogleNet | 93.7257% | 6.2743% | 93.6057% | 93.3936% | 93.4266% |

| SqueezNet | 90.4916% | 9.5084% | 90.4096% | 90.3301% | 90.2371% |

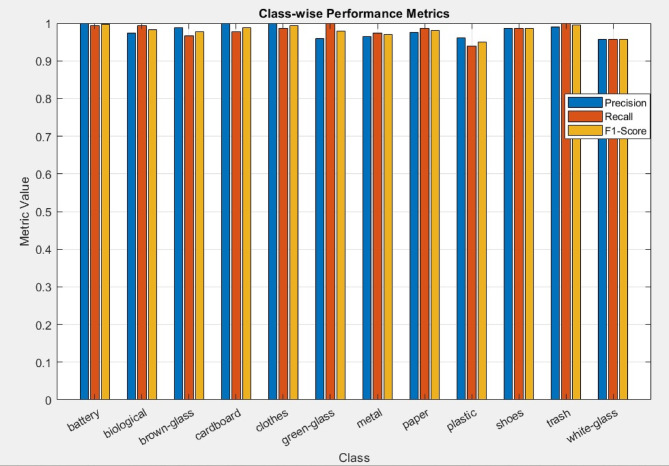

Figure 14 presents class level performance metrics, the precision, recall, and F1-score for the waste segregation model across the different classes. All of the results are still generally very high, approximately 1.0, illustrating a strong classification performance. Small discrepancies in classes such as metal, trash and white-glass indicate small misclassifications, but the results in general confirm the model’s rigour and relevance in practical waste management opera- tions.

Fig. 14.

Class-wise performance metric of precision, recall, F1-score.

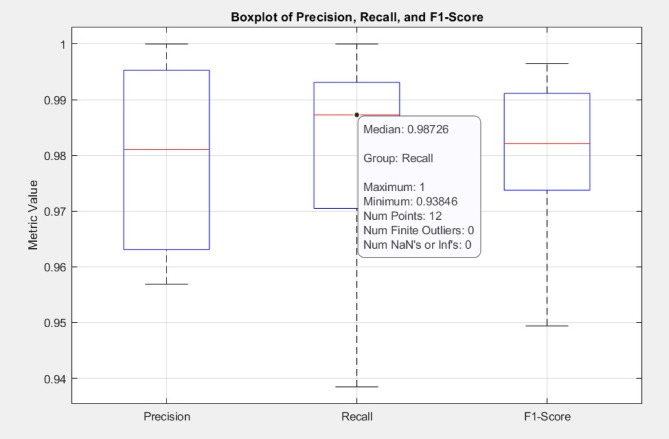

The boxplot in Fig. 15 illustrates the performance of the CNN model in waste segregation using Precision, Recall, and F1-Score metrics. The median precision (≈ 0.99) indicates the model’s ability to minimise false positives, while the median recall (≈ 0.98726) highlights its capability to detect most positive samples with minimal false negatives, despite a slight drop in the lower range from the minimum ≈(0.93846) to the maximum ≈ (1.0). The F1-Score consistently balances precision and recall, confirming the model’s robustness. The narrow range and absence of outliers across all metrics demonstrate the model’s stability and reliability across different waste categories, making it well-suited for efficient and accurate automated waste management.

Fig. 15.

Boxplot of precision, recall, F1-score.

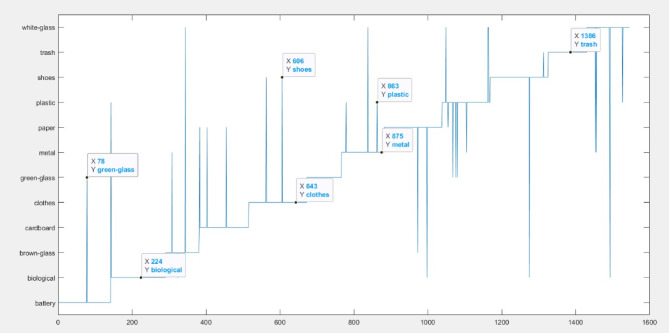

Each data point on the chart corresponds to a specific waste type, such as “trash,” “shoes,” “plastic,” and others, plotted against the x-axis, which likely represents the sequence of input images. The y-axis categorises the types of detected waste. CNN successfully identified specific categories, such as “green-glass” at X = 78, “biological” at X = 224, “shoes” at X = 606, “plastic” at X = 863, and “trash” at X = 1386. However, some categories, such as “clothes” and “metal,” show variability, indicating potential challenges in consistent detection. This variability may arise from overlapping visual features among categories or limitations in the model’s training data. The stair-step pattern observed in the plot suggests a sequential classification approach, where the model processes and categorizes inputs one at a time. The results highlight the CNN’s capability in waste segregation, while also emphasising the need for further optimisation, such as expanding the dataset, utilising advanced data augmentation techniques, or fine-tuning the model’s architecture, to improve detection accuracy across all waste categories. This study demonstrates the applicability of CNNs for automated waste management, a critical step toward efficient and sustainable recycling practices.

The accuracy measured regarding training and validation is depicted in Fig. 16. The blue line represents the Training accuracy whereas the Orange line demonstrates the Training loss of the training dataset. The X-axis represents the number of iterations used for the training dataset, while the Y-axis reflects the accuracy.

Fig. 16.

The graph of testing prediction.

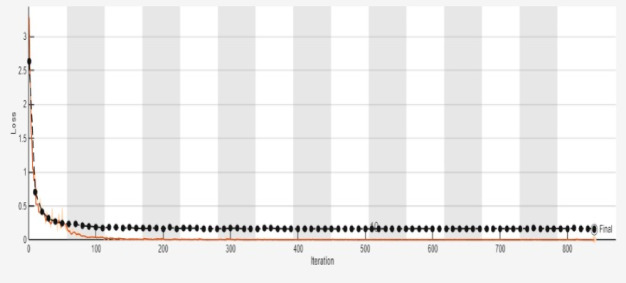

The training and validation accuracy graph Fig. 17 provides insights into the performance of the ResNet model during the learning process. Initially, the training accuracy (blue line) increases sharply as the model learns to classify the waste categories. By around 100 iterations, the accuracy stabilizes and gradually approaches nearly 100%. While the black dotted line denotes that the validation accuracy follows a similar trend, reaching a final value of 95.54%, this demonstrates strong generalisation on unseen data. The close alignment between training and validation accuracy throughout the iterations indicates that the model effectively avoids over fitting while maintaining consistency.

Fig. 17.

Training and validation accuracy graph.

The corresponding loss graph Fig. 18 offers further evidence of the model’s performance by tracking the error reduction over iterations. The orange line represents the training loss, which decreases sharply at the beginning, indicating rapid learning. Similarly, the black dotted line, representing the validation loss, follows the same trend, stabilizing at a low value. The close proximity of these lines confirms the model’s robustness, as it successfully minimizes errors for both the training and validation datasets. These graphs illustrate that the ResNet model strikes a balance between learning efficiency and accuracy.

Fig. 18.

Training and validation loss graph.

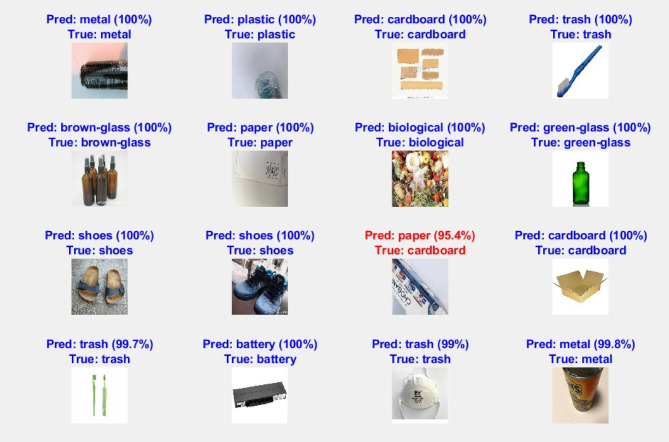

The comparison of the predicted and actual labels for 16 randomly selected test samples is visualised in Fig. 19. The model also accurately labeled 15 of 16 objects, indicating closely matching and robust performance. The close to perfect predictions demonstrate that the ResNet system can reliably discriminate between decomposable waste of different types under practical conditions.

Fig. 19.

Actual vs. predicted.

The suggested CNN model was trained using an 80:20 training-validation split with the Adam optimiser, categorical cross-entropy loss, and a batch size of 32 for 150 epochs. The performance stabilised after around 100 epochs, and the precision improved, along with a decrease in the validation loss, indicating the robustness of the learning. The tuning of hyperparameters fine-tuned the learning rate (0.0005), dropout (0.2–0.5), and batch size, which improved the model’s generalisation. Data augmentation (flipping, rotation, and contrast normalization) simulated variations in real situations and was effective to enhance robustness to distortions and occlusion. These improvements culminated in a final classification accuracy of 98.16%. Accuracy and loss plot, as well as confusion matrix analysis, supported the reduction in misclassification—such as differences in visual similarity classes, such as the green vs. white class of glass—proving that the model is accurate and consistent for waste sorting in real scenarios.

Discussion

The results of this study demonstrate that deep learning, particularly CNN-based models, can significantly enhance waste classification by automating the segregation of waste into organic and non-organic categories and further categorising twelve distinct types of waste. The proposed ResNet-based model outperformed other architectures, achieving an accuracy of 98.06%, making it the most reliable deep learning model for automated waste classification. However, despite the promising results, specific challenges and limitations must be acknowledged, along with opportunities for further optimization.

One key finding of this study is the advantage of deeper residual networks, such as ResNet, over shallower architectures, including AlexNet, VGG16, and GoogleNet. ResNet’s accuracy suggests that deeper models with optimized feature extraction layers are more effective in distinguishing between diverse waste categories. However, deeper networks improve performance and require higher computational resources, making real-time implementation challenging in low-power embedded systems or IoT-based waste management applications. Future work could focus on lightweight deep learning models, such as MobileNet or EfficientNet, which maintain high accuracy while reducing computational overhead.

The study also highlighted specific waste categories that were frequently misclassified. For example, brown glass was sometimes mistaken for biological waste, while white glass and green glass were misclassified due to their similar transparency and reflective properties. These errors indicate that shape and colour-based classification alone may not be sufficient for highly similar materials. One possible enhancement is the integration of multispectral imaging and material-based sensors to differentiate between waste types based on spectral signatures or chemical composition, rather than just visual features. Such techniques have been explored in industrial recycling and smart waste management research, and incorporating them into AI-based classification could significantly reduce misclassification rates.

Beyond improving classification accuracy, real-world deployment requires efficiency in processing speed, adaptability to varying environments, and integration with existing waste management infrastructures. The training and validation accuracy graphs (Figs. 16 and 17) demonstrated that the model effectively avoids overfitting, ensuring stable performance on unseen data. However, deployment in large-scale municipal waste sorting facilities would require further validation under real-world conditions, such as variations in camera angles, object occlusion, and contamination. The real-time simulation experiment in this study, where 15 out of 16 test images were correctly classified, suggests that the model is highly applicable for practical implementation. However, future studies should test the model using live video-based waste classification systems rather than relying solely on static image classification.

This study37 used a nonlinear fractional-order model with an Abel dashpot to describe the overall creep of the alkali-activated MSWI fly ash-based filling material. The model successfully simulated decelerating, constant, and accelerating creep stages under triaxial loading up to a total axial deformation, s_total = 0.46–0.78%, which was comparable to that of soft rock.

The evaluates the effect of ECER demonstration city policy on domestic waste control in China (2010–2020) using a staggered difference-in-differences model. Results show significant improvements in waste removal and disposal, driven by government investment, green lifestyles, and technological innovation38.

Table 5 compares the proposed CNN model (ResNet) with other commonly used deep learning architectures, including AlexNet, VGG16, GoogleNet, and SqueezeNet. The performance comparison, summarized in Table 4, highlights that ResNet outperformed all other models, achieving the highest accuracy (98.06%), the lowest miss rate (1.94%), and the best balance between precision (97.98%) and recall (98.02%).

Table 5.

Performance comparison of different deep learning models for waste Classification.

| Study | Model / Approach | Dataset | Accuracy (%) | Precision (%) | F1-Score (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cheema et al.2 | VGG16 + IoT Integration | Real-time Waste Dataset | 96.00 | 95.80 | 95.90 |

| He et al.31 | YOLOv3 + Smart City IoT | Custom Smart Waste Dataset | 94.80 | 94.50 | 94.60 |

| Abdulkareem17 | Efficient CNN for Trash | TrashNet | 95.10 | 94.30 | 94.60 |

| This Study (2025) | CNN (ResNet-based) | Kaggle Garbage Dataset | 98.16 | 97.98 | 97.99 |

Even when it is relatively accurate, the model struggles to distinguish between visually similar materials, such as specific glasses and plastics, particularly when lighting conditions or occlusion vary. Moreover, it is limited to considering material-specific properties because the approach is based on RGB images. For future studies, it would be worthwhile to investigate the combination of multispectral or hyperspectral imaging with lightweight architectures for edge deployment. Adding IoT-based sensors and real-time video analytics can further enhance scalability and performance in dynamic urban environments.

Conclusion

This study presents an intelligent waste classification framework using Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) to automate the segregation of urban waste into twelve categories, addressing the critical challenge of inefficient waste management in smart cities. A high classification accuracy of 98.16% was achieved by the proposed ResNet-based model, which significantly outperforms those of other deep learning models, such as AlexNet, VGG16, GoogleNet, and SqueezeNet. With good data preprocessing, data augmentation, and hyperparameter tuning, it achieved good generalizability and practical robustness. The embedding of adaptive filters and performance measures, such as precision, recall, and F1-score, further demonstrates the validity of the model in dealing with different types of waste across various challenges. It is demonstrated through this study towards sustainable waste management by enabling automation, accuracy and scalability of modern cities.

Author contributions

G.A. and F.M.A. conceptualized the study and designed the research methodology. G.A. and T.A. developed and trained the Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) model. A.A. and S.A. conducted the data preprocessing and augmentation, and N.T. performed the statistical analysis. A.M.I. prepared Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 and 13 and drafted the initial manuscript. Q.A. and W.N. performed critical revisions and helped improve the structure and clarity of the manuscript. T.M.G. contributed to technical validation and provided expert feedback on model optimization. G.A. and F.M.A. finalized the manuscript, ensuring its coherence and alignment with the journal’s requirements. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript prior to submission.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Nadia Tabassum, Email: nadiatabassum@vu.edu.pk.

Aidarus Mohamed Ibrahim, Email: aidarusibrahim11@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Kumari, T. & Raghubanshi, A. S. Waste management practices in the developing nations: challenges and opportunities, Waste Manag. Resour. Recycl. Dev. World 773–797, 2023, (2022). 10.1016/B978-0-323-90463-6.00017-8

- 2.Cheema, S. M., Hannan, A. & Pires, I. M. Smart waste management and classification systems using cutting edge approach, Sustain. 14 16 (2022). 10.3390/su141610226

- 3.Abdel-Shafy, H. I. & Mansour, M. S. M. Solid waste issue: sources, composition, disposal, recycling, and valorization. Egypt. J. Pet.27 (4), 1275–1290. 10.1016/j.ejpe.2018.07.003 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nadeem, K. et al. Municipal solid waste generation and its compositional assessment for efficient and sustainable infrastructure planning in an intermediate City of Pakistan. Environ. Technol. (United Kingdom). 44 (21), 3196–3214. 10.1080/09593330.2022.2054370 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Waste dumping-landfill problems end product – WtE. p. [1] waste dumping-landfill problems end product –, (2018).

- 6.Mor, S. & Ravindra, K. Municipal solid waste landfills in lower- and middle-income countries: Environmental impacts, challenges and sustainable management practices, Process Saf. Environ. Prot.174 510–530(2022). 10.1016/j.psep.2023.04.014

- 7.Kaur, M., Soodan, R. K., Kumar, V., Katnoria, J. K. & Nagpal, A. Sustainable solutions for solid waste management: A review. Int. J. Adv. Res. Biol. Sci. Int. J. Adv. Res. Biol. Sci.2 (2), 79–86 (2015). [Online]. Available: www.ijarbs.com. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adetunji, A. I., Oberholster, P. J. & Erasmus, M. From garbage to treasure: A review on biorefinery of organic solid wastes into valuable biobased products. Bioresour Technol. Rep.24, 101610. 10.1016/j.biteb.2023.101610 (2023). no. August. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen, X. Machine learning approach for a circular economy with waste recycling in smart cities, Energy Rep. 8 3127–3140 2022. 10.1016/j.egyr.2022.01.193

- 10.Gade, D. S. & Aithal, P. S. Smart city waste management through ICT and IoT driven solution. Int J. Appl. Eng. Manag Lett 51–65, (2021).

- 11.Iqbal, M., Shafiq, M. U., Khan, S., Obaidullah, Alahmari, S. & Ullah, Z. Enhancing task execution: a dual-layer approach with multi-queue adaptive priority scheduling. PeerJ. Comput. Sci.10, e2531. 10.7717/peerj-cs.2531 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sosunova, I. & Porras, J. IoT-Enabled smart waste management systems for smart cities: a systematic review, IEEE Access10 73326–73363 (2022). 10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3188308

- 13.Tiwari, S., Bisht, S. & Sharma, K. Intelligent waste management using wasteIQNet with hierarchical learning and Meta-Optimization, in IEEE access, 10.1109/ACCESS.2025.3574095

- 14.Arun, M. Investigation of a deep learning-based waste recovery framework for sustainability and a clean environment using IoT. Sustain. Food Technol.3, 599–611. 10.1039/d4fb00340c (2025). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al Duhayyim, M. et al. Deep reinforcement learning enabled smart city recycling waste object classification. Comput. Mater. Contin. 71 (2), 5699–5715. 10.32604/cmc.2022.024431 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 16.M. Kaya, S. Ulutürk, Y. Çetin Kaya, O. Altıntaş, and B. Turan, Optimization of several deep CNN models for waste classification, SAUCIS 6 2, 91–104 (2023)

- 17.Abdulkareem, K. H. et al. A manifold intelligent decision system for fusion and benchmarking of deep waste-sorting models. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell.132, 107926. 10.1016/j.engappai.2024.107926 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huh, J. H., Choi, J. H. & Seo, K. Smart trash Bin model design and future for smart city. Appl. Sci.11 (11). 10.3390/app11114810 (Jun. 2021).

- 19.Gaur, T. S., Yadav, V., Mittal, S., Singh, S. & Khan, M. A. E-Waste management challenges in India from the perspective of producer responsibility organizations, in IEEE access, 13, 54462–54473, (2025). 10.1109/ACCESS.2025.3553203

- 20.Hasanat, S. M. et al. Enhancing short-term load forecasting with a CNN-GRU hybrid model: a comparative analysis. In IEEE Access 12 184132–184141, (2024). 10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3511653

- 21.Amritkar, M. V. Automatic waste management system with RFID and ultrasonic sensors. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Eng.5 (10), 240–242 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fang, B. et al. Artificial intelligence for waste management in smart cities: a review. Springer Int. Publishing. 2110.1007/s10311-023-01604-3 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Mazanov, G. et al. Hyperspectral data driven solid waste classification, In IEEE Access13 46659–46672, (2025). 10.1109/ACCESS.2025.3551097

- 24.Glazyrin, S. A., Aibuldinov, Y. K., Kopishev, E. E., Zhumagulov, M. G. & Bimurzina, Z. A. Analysis of the composition and properties of municipal solid waste from various cities in Kazakhstan. Energies17, 6426. 10.3390/en17246426 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ahmed, M. I. B. et al. Deep learning approach to recyclable products classification: towards sustainable waste management. Sustain15 (14). 10.3390/su151411138 (2023).

- 26.Szpilko, D., de la Gallegos, A., Jimenez Naharro, F., Rzepka, A. & Remiszewska, A. Waste management in the smart city: current practices and future directions. Resources12 (10), 1–25. 10.3390/resources12100115 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ahmed, M., Chatterjee, M. & Moustafa, N. Integration of federated learning with IoT for smart cities applications, challenges, and solutions. PeerJ Comput. Sci.10, e1657. 10.7717/peerj-cs.1657 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tang, H. & Zhao, J. Optimizing deep neural network architectures for renewable energy forecasting. Energy Inf.10, 43–60. 10.1007/s43621-024-00615-6 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee, D. & Park, S. Optimizing smart home energy management for sustainability using machine learning techniques. Energ. Syst.12 (3), 189–207. 10.1007/s43621-024-00681-w (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nguyen, T. & Chen, R. Comparative analysis of deep neural network architectures for renewable energy forecasting: enhancing accuracy with meteorological and time-based features. Renew. Energy J.15 (1), 299–320. 10.1007/s43621-024-00783-5 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 31.He, J. et al. EC-YOLOX: A deep learning algorithm for floating objects detection in ground images of complex water environments.(IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing, 2024).

- 32.Selvarajan, S. A comprehensive study on modern optimization techniques for engineering applications. Artif. Intell. Rev.57 (8), 194 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu, S., Cao, J. & Shao, Q. How to select remanufacturing mode: end-of-life or used product? Environ. Dev. Sustain., 1–21. (2024).

- 34.Hu, C., Zhao, C., Shao, H., Deng, J. & Wang, Y. TMFF: trustworthy multi-focus fusion framework for multi-label sewer defect classification in sewer inspection videos. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol.34 (12), 12274–12287. 10.1109/TCSVT.2024.3433415 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen, Y., Li, Q. & Liu, J. Innovating sustainability: VQA-based AI for carbon neutrality challenges. J. Organizational End. User Comput.36 (1), 1–22. 10.4018/JOEUC.337606 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jagadeesh, G. et al. EADCN-BCSR: A novel framework for accurate and real-time waste detection and classification. Earth Sci. Inf.18, 379. 10.1007/s12145-025-01838-5 (2025). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Su, L., Wu, S., Fu, G., Zhu, W., Zhang, X. Liang, B. (2024). Creep characterisation and microstructural analysis of municipal solid waste incineration fly ash geopolymer backfill. Sci. Rep., 14 (1), 29828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Ma, Q., Zhang, Y., Hu, F. & Zhou, H. Can the energy conservation and emission reduction demonstration city policy enhance urban domestic waste control? evidence from 283 cities in China. Cities154, 105323. 10.1016/j.cities.2024.105323 (2024). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on request.