Abstract

Introduction

Anxiety around mealtime continuous to hinder nutritional rehabilitation even after significant weight restoration which undermines recovery with pharmacological and psychological treatments proving to be of little effectiveness. This study explored the anxiolytic effects of wearing a warming vest either during lunchtimes or postlunch rest in comparison to treatment as usual in a sample of AN adolescent patients during nutritional rehabilitation.

Method

14 consecutive inpatients at a Child and Adolescence Mental Health Unit underwent each of the 3 conditions at lunchtime in random order and separated by 2 days: Treatment as usual, wearing heating vest during lunch time, and wearing heating vest during first 30 min of rest time.

Results

According to median prelunch anxiety, half of the sample were classified as a High prelunch anxiety group (HPA), while the remaining 7 were classified as a Low prelunch anxiety group (LPA). Wearing the heating vest either during lunch time or during the 30 min lunch rest significantly decreased patient anxiety in the HPA group, but no differences were in observed in the LPA patients.

Conclusion

These results corroborated prior reports of the anxiolytic effect of warming during lunch rest and extend this anxiolytic effect of warming to lunchtime.

Keywords: Anorexia nervosa, Heat treatment, Lunchtime anxiety, Activity-based anorexia

Plain language summary

This study looked at whether wearing a warming vest could help reduce anxiety during mealtimes in teenagers with anorexia nervosa (AN) who were in a hospital for nutritional recovery. Fourteen patients took part. Each tried three different conditions in random order: regular treatment, wearing the vest during lunch, and wearing it after lunch. The researchers divided the patients into two groups based on their anxiety levels before meals—high or low. In the high-anxiety group, wearing the vest either during or after lunch helped lower their anxiety. However, there was no effect in the low-anxiety group. The study confirms that warmth after meals can reduce anxiety and shows that warmth during meals also helps in patients with high anxiety.

Introduction

AN is a serious mental disorder affecting mainly adolescent women and is characterized by a severe restriction of food intake often resulting in critical weight loss with serious physical and psychological consequences [2]. Although AN is a low prevalence disorder, AN is the mental disorder with the highest mortality rate [7], a modest long-term recovery ranging from one-third to a half of patients, and a relatively poor prognosis with 8% to 15% of patients experiencing a chronic course [33, 41].

Furthermore, there is no evidence substantiating the efficacy of any pharmacological treatment for anorexia nervosa ([9], [28]), only low‐quality evidence [11] has found a moderate effectiveness of family-based treatments in adolescents with AN, and there is no reliable evidence for treatments with clinical guidelines for adults with anorexia nervosa [44], which have shown to be superior to treatment as usual ([19], [38]).

Weight restoration continues to be the single major challenge in AN treatment [43], [37], and anxiety around mealtime continues to be a major hurdle even after significant weight restoration [46]. Premeal anxiety is inversely associated to the number of calories ingested [36], [46] and is associated to abnormal eating behavior [15]. There is a clear need for specific interventions designed to reduce anxiety and facilitate nutritional rehabilitation during the recovery process in AN [39].

Recently, Zandian et al., [48] reported a post meal anxiolytic effect of half an hour rest in bed in a small, warmed room at 32º in comparison with two other conditions (same individual room at 21 °C or resting with other patients in a shared room). These results are in line with the calming effect associated with the use of thermal vests as well as a welcoming improvement in digestion in another clinical trial [4] considering that postprandial distress syndrome is one of the reasons for calory restriction characteristic among AN patient [40].

The idea of supplying external heat to patients in addition to food has a clear precedent in William Gull's [17] mention of a standard practice at the Ticehurst Asylum in East Sussex, England. This practice was in turn based on early preclinical studies on animal starvation conducted by Charles Chossat (1796–1875), a Swiss physiologist who discovered the curative effects of heat on starved animals [20]. Thus, Gull's recommendation could be considered one of the first examples of a "bench-to-bedside" process to bring preclinical research results to the clinic to benefit patients. Since then, a case series [24], and two controlled trials ([5], [4]) have been published reporting the benefits of adding heat supply to AN patients during treatment.

These contemporary studies can also be considered an example of translational research based on preclinical research with an animal model of anorexia nervosa known as activity-based anorexia (ABA), in which rats with free access to an activity wheel are restricted to 1.5 h/day of food. ABA is considered the best animal model of AN reproducing the main signs of anorexia nervosa, such as hyperactivity, severe weight loss, food restriction, hypothermia, sleep disorders, and marked reductions in brain gray and white matter volume among other signs [12]. The ABA model, also reproduces other signs present in AN such as an increased activity of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis a major neuroendocrine system resulting in increased levels of corticosterone and adrenocorticotropic hormone, hormones that work together to regulate stress and metabolism, and enlarged adrenal glands [6], [26], as well as alterations in various appetite-regulating hormones, mainly the central melanocortin system involved in the regulation of energy balance [1], [27]. AN patients also show increased levels of plasma cortisol and corticotropin releasing hormone, playing an important role in anxiety [10], indicating increased activity of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis [16], [29], [30] and also, changes in the brain melanocortin system MC system have also been reported in AN patients [31].

esearch with the ABA model has provided robust preclinical experimental evidence that increasing the ambient temperature to 32 °C reversed excessive activity, improved food intake, and allowed weight recovery in rats [8, 21]. This triple reversal was particularly remarkable given the animals had already lost 20% of their weight while being exposed to restricted feeding and unlimited access to the activity wheel. The increase in ambient temperature allowed the recovery of 100% of the animals, while at room temperature (21 °C) 100% of the animals had to be removed from the experimental conditions [18].

In line with the work of Zandian et al. [48], the present paper explored the anxiolytic effects of wearing a warming vest. Moreover, the effects of wearing the heating vest were assessed not only during postlunch rest but also during lunchtimes in comparison with treatment as usual in a sample of AN adolescent patients undergoing nutritional rehabilitation.

Methods

Participants

A sample of 14 consecutive inpatients at a Child and Adolescence Mental Health Unit at the University Clinical Hospital of Santiago de Compostela participated in the study. Inclusion criterion for this study was the presence of AN according to the DSM-5 criteria and being 12 to 16 years old. Upon confirmation of the eating disorder diagnosis and after obtaining written informed consent from the participants, and their parents, patients underwent 3 conditions around mealtime presented in random order and separated by 2 days: Control (TAU), wearing heating vest during lunch time (VL), and wearing heating vest during the first 30 min of the 1 h postlunch rest time (VR). Random order of treatments for each patient was established in advance, even before patients being admitted to hospital. This ensured that, over the course of one week, each patient was exposed once to each of the three conditions: TAU, VL, and VR. Exposure to the different conditions was scheduled with a two-day interval between them, and to avoid carryover effects, the order of exposure to the three conditions was randomly determined in advance.

Routinely, patients had lunch for 45 min at 13:00 together with other patients admitted to the child and adolescent psychiatry unit, which was followed by a one-hour rest in the same room, at 26 °C.

Patients completed the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, and the State Anxiety Scale at five time points around meals (30 min before the lunch, at the beginning and end of the lunch, and after 30 and 60 min of postlunch rest). For each patient anxiety measures were taken in three conditions, control (no heating vest), and wearing a heating vest either during lunch, or during the first half hour of after lunch rest. The vest employed was a commercial heating vest (CONQUECO©) that has 4 heating zones: neck, mid-back, left and right chest. It was set to a high mode unless patients asked for a lower temperature.

Additional psychological and anthropometric measures were assessed at the beginning of the study (Table 1). All procedures were approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Galician Health Service (SERGAS), Spain.

Table 1.

Demographic data and psychological measures for the entire group, and separately for the HPA and LPA groups

| HPA group (n = 7) | LPA group (n = 7) | Total (n = 14) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean yrs (range; SD) | 13.3 (12–15; 1.2) | 13.8 (12–16; 1.7) | 13.6 (1.4) |

| BMI, mean (SD) kg/m2 | 17.1 (1.1) | 16.3 (1.1) | 16.7 (1.1) |

| Duration of illness in months, mean (SD) | 13.6 (5.9) | 8.2 (6.3) | 11.1 (6.5) |

| Prelunch anxiety, mean (SD) | 50 (1.5) ** | 35.6 (12.1) | 42.8 (11.1) |

| STAIC-T | 49.1 (7.1; 6P) * | 36.7 (6.8; 4P) | 44.2 (9.2) |

| STAIC-S | 46.4 (4.9) * | 33.8 (10.7) | 40.1 (10.3) |

| CDI | 30.7 (9.5; 4P) * | 13.6 (7; 5P) | 21.22 (11.8) |

| EDI | 164.8 (5.3; 5P) | 151.6 (23.9; 5P) | 158.2 (17.8) |

| DT | 22.2 (3.2; 5P) | 19 (11.7; 5P) | 20.6 (8.3) |

| BD | 30.2 (10.1; 5P) | 24.2 (14.4; 5P) | 27.3 (12.1) |

BD, body dissatisfaction scale; BMI, body mass index (weight/height2); DT, drive for thinness scale; CDI, children’s depression inventory; EDI, eating disorders inventory; SD, standard deviation. STAIC-S/T, state-trait anxiety inventory for children. *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01

According to median prelunch anxiety (47.5), patients were classified as High prelunch anxiety (HPA) group (mean = 49.8; n = 7 patients) while the remaining 7 were classified as Low prelunch anxiety (LPA) group (mean = 33.7).

Psychological measures and VAS scales

Psychological measures included the following self-report instruments: the Eating Disorder Inventory-3 (EDI-3, [14]), only the total score and the subscales Drive for Thinness (DT) and Body Dissatisfaction (BD) are shown,the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children (STAIC, [45]); and the Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI, [32]). Moreover, after lunch patients were required to indicate on a 0–10 VAS scale about their degree of abdominal discomfort (functional dyspepsia according to Rome IV criteria): early satiety, postprandial fullness, epigastric pain and nausea [3].

Data analysis

Non-parametric statistical tests that did not assume normal distribution were used. The Friedman test among repeated measures was used to test changes over time for the whole group of patients and for changes over time in both HPA and LPA. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare HPA and LPA groups while the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare paired samples for the whole group and both HPA and LPA groups. A p-value < 0.05 was used to assess statistical significance.

Results

As shown in Table 1, there were significant differences between HPA and LPA groups for prelunch anxiety. Moreover, the HPA group was more depressed (U = 2, p = 0.05), and scored higher in trait anxiety on the STAIC-T (U = 2, p = 0.03), but no differences were observed either in the EDI total score nor on the DT and BD subscales. There was a nonsignificant tendency for the HPA to have a higher illness duration (U = 8, p = 0.06).

Prelunch anxiety significantly increased from 30 min before lunch for the whole group of 14 patients, (z = −3,26, p = 0.001), and this increase was observed in both HPA and LPA groups (z = −2.32, p = 0.02 in both cases).

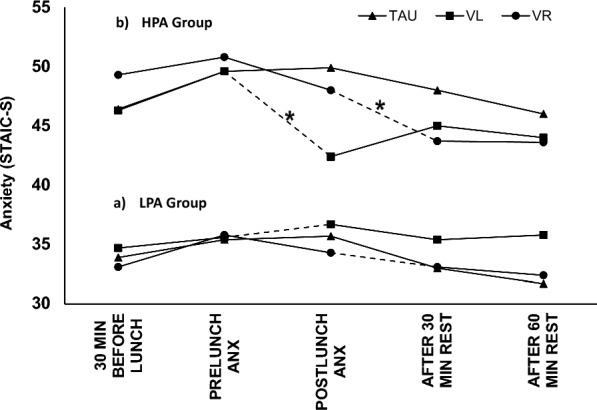

Wearing the heating vest during lunch time significantly decreased anxiety for the whole group of 14 patients (z = −2.181, p = 0.03). When results were analyzed for both subgroups, only the HPA group showed a significant reduction in anxiety (z = −2.197, p = 0.03) but not the LPA group, as depicted in Fig. 1. Furthermore, wearing the heating vest during the 30 min lunch rest significantly decreased anxiety for patients in the HPA group (z = −2.375, p = 0.02), whereas no differences in anxiety were observed in the LPA patients.

Fig. 1.

Evolution of anxiety around mealtimes. Two groups of seven patients with anorexia nervosa, with high (HPA) and low (LPA) anxiety, underwent three conditions in a counterbalanced sequence: use of a heated vest either during lunch (VL) or during the first 30 min after lunch rest (VR), or without a heated vest (TAU), while their anxiety was assessed at the indicated times. The high (HPA, N = 7) and low (LHA, N = 7) anxiety groups are shown respectively at the top and bottom of the figure. Thus, for example TAU lines in both the HPA and LPA groups depicts patients mean anxiety scores the day they did not wear the heated vest. Dashed lines represent the period patients wore the heated vest. The asterisks (*) indicate statistically significant changes (p < 0.05)

From prelunch anxiety to the final measurement after 1 h rest, anxiety levels only decreased in the HPA group while wearing the heating vest either during lunch time (z = −1.892, p = 0.05) or for the 30 min lunch rest, (z = −2.120, p = 0.03), but not in the TAU condition. On the other hand, no differences were observed between these measures for the LPA group in any of the three conditions (TAU, VL and VR) as shown in Fig. 1.

No differences were found in wearing the heating vest and gastric discomfort after lunch, all five scales measuring gastric discomfort p > 0.05.

Discussion

The results of this study have provided empirical evidence that brief heat applications to patients reduced anxiety levels from prelunch time to one hour afterwards. These results corroborated the anxiolytic effect of warming during lunch rest reported by Zandian et al., [48], and extend this anxiolytic effect of warming to patients during mealtime. However, the anxiolytic effect of a single session wearing the warming vest during postmeal rest was smaller than that reported by Zandian et al. [48] for patients resting in a room at 32ºC. Notwithstanding, decreases in anxiety levels either during mealtime or rest were in the same range as those reported by Steinglass et al., [47], after 12 sessions of an exposure and response prevention treatment designed to target fear and anxiety related to food intake in patients who had achieved near normal weight restoration.

Patients rated wearing the heating vest as a positive experience: the most frequent subjective benefit expressed was that the vests were pleasant and relaxing to wear. However, in the VL condition, 3 of the 14 patients (two from LPA and one from the HPA group) asked for a lowering of the vest temperature, and another 2 patients (one from HPA and one from LPA) needed to take the vest off before finishing lunch because they felt the temperature was excessive. These complaints seemed not to have hindered the anxiolytic effect reported for the HPA group. However, this reduction in anxiety was smaller than that obtained by Zandian et al., [48], who employed more immersive sessions at higher temperatures, which may explain the discrepancy in the results.

Wearing the vest during lunchtime had no effect on gastric discomfort. It is plausible that the absence of an effect could be related to the position of the front thermal pads being well above the abdomen.

The present study does not clarify the mechanism by which heat exerted this effect only in the HPA group of patients, whose anxiety and depression scores were significantly higher than those of the LPA group, but not their level of eating disorders or other aspects such as age or disease duration (see Table 1).

At present we can only speculate about these mechanisms by drawing on the evidence from preclinical research using the ABA model [23]. For instance, the documented effect of heat in reversing the overexpression of the hypothalamic MC4 receptor, which participates in the hypothalamic leptin-melanocortin signaling pathway and plays a key role in suppressing food intake [22], as well as the increase in circulating leptin levels [13]. Though the regulation of food intake and body composition through the action of leptin on the melanocortin system is widely documented in both rats and humans [42], and although leptin substitution therapy is currently being explored [25], blocking melanocortin signaling for the treatment of AN remains unfeasible.

Furthermore, it is worth highlighting the striking reduction in corticosterone blood levels of heated rats up to a fifth of the level found in ABA animals at a standard AT of 21 °C [13], which again provides a plausible explanation for the anxiolytic effect of warming given the elevated cortisol levels associated with anxiety in AN [34], [35].

There are several limitations to this study that should be mentioned. First, the small number of patients showing high prelunch anxiety. An unexpected finding was that half of the patients showed low anxiety scores, and it should be noted the room temperature used for lunch and rest was 26 °C. However, raised AT did not inhibit the heating vests from reducing anxiety in the HPA group. Furthermore, most of the patients were under anxiolytic medication, which could have buffered the effect of wearing a heating vest on anxiety levels.

Future randomized clinical trial studies should continue exploring both the immediate (as in the case of premeal anxiety) and the distal consequences (outcome of nutritional rehabilitation) of providing continuous external heat to patients with AN, as well as the inclusion of serum biochemical parameters and hormone levels that help identify the mechanisms underpinning the beneficial action of heat.

Author contributions

O C: conceptualization; investigation; methodology; writing:—original draft; writing:—review and editing. C A: investigation and testing; writing—review and editing. JM: investigation; writing—review and editing. E G: methodology; resources; writing—review and editing.

Funding

Supported by the research budget of the Unidad Venres Clinicos: 5064.C2MS.64200S.

Availability of data and materials

Data are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Galician Health Service (SERGAS): 2022/151. Informed consent was obtained from all study participants and their parents.

Consent for publication

An institutional consent form was used to acquire consent for publication from all study participants.

Competing interests

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Adan RA, Hillebrand JJ, De Rijke C, Nijenhuis W, Vink T, Garner KM, et al. Melanocortin system and eating disorders. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;994:267–74. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb03189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Edition F. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Am Psychiatric Assoc. 2013;21(21):591–643. 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asociación madrileña de Pediatría de Atención Primaria (AMPAP) . Trastornos Gastrointestinales Funcionales Pediátricos. Criterios Roma IV. Guías de actuación conjunta Pediatría Primaria-Especializada, Madrid. 2017.

- 4.Birmingham CL, Gutierrez E, Jonat L, Beumont P. Randomized controlled trial of warming in anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2004;35(2):234–8. 10.1002/eat.10246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bergh C, Brodin U, Lindberg G, Södersten P. Randomized controlled trial of a treatment for anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(14):9486–91. 10.1073/pnas.142284799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burden VR, White BD, Dean RG, Martin RJ. Activity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis is elevated in rats with activity-based anorexia. J Nutr. 1993;123(7):1217–25. 10.1093/jn/123.7.1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Button EJ, Chadalavada B, Palmer RL. Mortality and predictors of death in a cohort of patients presenting to an eating disorders service. Int J Eat Disord. 2010;43(5):387–92. 10.1002/eat.20715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cerrato M, Carrera O, Vázquez R, Echevarria E, Gutiérrez E. Heat makes a difference in activity-based Anorexia: a translational approach to treatment development in Anorexia Nervosa. Int J Eat Disorder. 2012;45:26–35. 10.1002/eat.20884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crow SJ, Mitchell JE, Roerig JD, Steffen K. What potential role is there for medication treatment in anorexia nervosa? Int J Eat Disord. 2009;42(1):1–8. 10.1002/eat.20576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dedic N, Kühne C, Jakovcevski M, Hartmann J, Genewsky AJ, Gomes KS, et al. Chronic CRH depletion from GABAergic, long-range projection neurons in the extended amygdala reduces dopamine release and increases anxiety. Nat Neurosci. 2018;21(6):803–7. 10.1038/s41593-018-0151-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fisher CA, Skocic S, Rutherford KA, Hetrick SE. Family therapy approaches for anorexia nervosa. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;5(5):CD004780. 10.1002/14651858.CD004780.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Foldi CJ. Taking better advantage of the activity-based anorexia model. Trends Mol Med. 2024;30(4):330–8. 10.1016/j.molmed.2023.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fraga A, Rial-Pensado E, Nogueiras R, Fernø J, Diéguez C, Gutierrez E, et al. Activity-based Anorexia induces browning of adipose tissue independent of hypothalamic AMPK. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;12:669980. 10.3389/fendo.2021.669980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garner D M (2010) EDI-3, Inventario de trastornos de la conducta alimentaria. (Spanish adaptation: Elosua, P., López-Jauregui P., and Sánchez F). Hogrefe TEA Ediciones. 2017.

- 15.Gianini L, Liu Y, Wang Y, Attia E, Walsh BT, Steinglass J. Abnormal eating behavior in video-recorded meals in anorexia nervosa. Eat Behav. 2015;19:28–32. 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2015.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gold PW, Gwirtsman H, Avgerinos PC, Nieman LK, Gallucci WT, Kaye W, et al. Abnormal hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal function in Anorexia Nervosa. N Engl J Med. 1986;314(21):1335–42. 10.1056/NEJM198605223142102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gull W. Anorexia nervosa (apepsia hysterica, anorexia hysterica). Clin Soc Trans. 1874;7:22–8. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gutierrez E. A rat in the labyrinth of anorexia nervosa: Contributions of the activity-Based Anorexia rodent model to the understanding of anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disorder. 2013;46:289–301. 10.1002/eat.22095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gutiérrez E, Carrera O. Anorexia nervosa treatments and Occam’s razor. Psychol Med. 2018;48(8):1390–1. 10.1017/S0033291717003944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gutierrez E, Carrera O (2020) Warming in anorexia nervosa: a review. In: H.Himmerich (ed.) Weight Management. London: IntechOpen. 10.5772/intechopen.90353.

- 21.Gutierrez E, Cerrato M, Carrera O, Vazquez R. Heat reversal of activity-based anorexia: implications for the treatment of anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2008;41(7):594–601. 10.1002/eat.20535./eat.20535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gutiérrez E, Churruca I, Zárate J, Carrera O, Portillo MP, Cerrato M, et al. High ambient temperature reverses hypothalamic MC4 receptor overexpression in an animal model of anorexia nervosa. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34(3):420–9. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gutierrez E, García N, Carrera O. Disordered eating in anorexia nervosa: give me heat, not just food. Front Public Health. 2024;6(12):1433470. 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1433470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gutierrez E, Vazquez R. Heat in the treatment of patients with anorexia nervosa. Eat Weight Disord. 2001;6(1):49–52. 10.1007/BF03339752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hebebrand J, Hinney A, Antel J. Could leptin substitution therapy potentially terminate entrapment in anorexia nervosa? Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2023;19(8):435–6. 10.1038/s41574-023-00863-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hillebrand JJ, Kas MJ, Adan RA. alpha-MSH enhances activity-based anorexia. Peptides. 2005;26(10):1690–6. 10.1016/j.peptides.2004.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hillebrand JJ, Kas MJ, Scheurink AJ, van Dijk G, Adan RA. AgRP(83–132) and SHU9119 differently affect activity-based anorexia. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2006;16(6):403–12. 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Himmerich H, Kan C, Au K, Treasure J. Pharmacological treatment of eating disorders, comorbid mental health problems, malnutrition and physical health consequences. Pharmacol Ther. 2021;217:107667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hotta M, Shibasaki T, Masuda A, Imaki T, Demura H, Ling N, et al. The responses of plasma adrenocorticotropin and cortisol to corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) and cerebrospinal fluid immunoreactive CRH in anorexia nervosa patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1986;62(2):319–24. 10.1210/jcem-62-2-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaye WH, Berrettini WH, Gwirtsman HE, Chretien M, Gold PW, George DT, et al. Reduced cerebrospinal fluid levels of immunoreactive pro-opiomelanocortin related peptides (including beta-endorphin) in anorexia nervosa. Life Sci. 1987;41(18):2147–55. 10.1016/0024-3205(87)90533-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaye WH, Gwirtsman HE, George DT, Ebert MH, Jimerson DC, Tomai TP, Chrousos GP, Gold PW, et al. Elevated cerebrospinal fluid levels of immunoreactive corticotropin-releasing hormone in anorexia nervosa: relation to state of nutrition, adrenal function, and intensity of depression. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1987;64(2):203–8. 10.1210/jcem-64-2-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kovacs M. Children’s depression inventory. Toronto: Multi-Health Systems; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Quadflieg N, Naab S, Fichter M, Voderholzer U. Long-term outcome and mortality in adolescent girls 8 years after treatment for Anorexia Nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2024;57(12):2497–503. 10.1002/eat.24299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Landon J, Greenwood FC, Stamp TC, Wynn V. The plasma sugar, free fatty acid, cortisol, and growth hormone response to insulin, and the comparison of this procedure with other tests of pituitary and adrenal function II In patients with hypothalamic or pituitary dysfunction or anorexia nervosa. J Clin Invest. 1966;45(4):437–49. 10.1172/JCI105358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lawson EA, Holsen LM, Desanti R, Santin M, Meenaghan E, Herzog DB, et al. Increased hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal drive is associated with decreased appetite and hypoactivation of food-motivation neurocircuitry in anorexia nervosa. Eur J Endocrinol. 2013;169(5):639–47. 10.1530/EJE-13-0433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lloyd EC, Powell C, Schebendach J, Walsh BT, Posner J, Steinglass JE. Associations between mealtime anxiety and food intake in anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2021;54(9):1711–6. 10.1002/eat.23589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maguire S, Kesby A, Brownlow R, Hunt GE, Kim M, McAulay C, Russell J. A phase II randomised controlled trial of intranasal oxytocin in anorexia nervosa. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2024;164:107032. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2024.107032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Monteleone AM, Abbate-Daga G. Effectiveness and predictors of psychotherapy in eating disorders: state-of-the-art and future directions. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2024;37(6):417–23. 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Murray SB, Loeb KL, Le Grange D. Dissecting the core fear in Anorexia Nervosa: can we optimize treatment mechanisms? JAMA Psychiat. 2016;73:891–2. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Santonicola A, Siniscalchi M, Capone P, Gallotta S, Ciacci C, Iovino P. Prevalence of functional dyspepsia and its subgroups in patients with eating disorders. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18(32):4379–85. 10.3748/wjg.v18.i32.4379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schmidt U, Adan R, Böhm I, Campbell IC, Dingemans A, Ehrlich S, et al. Eating disorders: the big issue. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(4):313–5. 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)00081-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schwartz MW, Woods SC, Porte D Jr, Seeley RJ, Baskin DG. Central nervous system control of food intake. Nature. 2000;404(6778):661–71. 10.1038/35007534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sjögren M, Kizilkaya I, Støving RK. Inpatient weight restoration treatment is associated with decrease in post-meal anxiety. J Pers Med. 2021;11(11):1079. 10.3390/jpm11111079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Solmi M, Wade TD, Byrne S, Del Giovane C, Fairburn CG, Ostinelli EG, De Crescenzo F, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of psychological interventions for the treatment of adult outpatients with anorexia nervosa: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8(3):215–24. 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30566-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spielberger CD, Edwards CD, Lushene RE, Montuori J, Platzek D. STAIC, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children (N. Seidedos Cubero, adaptador). (4º edición). Hogrefe TEA Ediciones. 2009

- 46.Steinglass JE, Sysko R, Mayer L, Berner LA, Schebendach J, Wang Y, Walsh BT. Pre-meal anxiety and food intake in anorexia nervosa. Appetite. 2010;55(2):214–8. 10.1016/j.appet.2010.05.090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Steinglass JE, Albano AM, Simpson HB, Wang Y, Zou J, Attia E, et al. Confronting fear using exposure and response prevention for anorexia nervosa: a randomized controlled pilot study. Int J Eat Disord. 2014;47(2):174–80. 10.1002/eat.22214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zandian M, Holmstedt E, Larsson A, Bergh C, Brodin U, Södersten P. Anxiolytic effect of warmth in anorexia nervosa. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2017;135(3):266–7. 10.1111/acps.12691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the corresponding author upon request.