Abstract

There is a critical unmet need for safe and efficacious neoadjuvant treatment for cisplatin-ineligible patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Here we launched a phase 1b study using the combination of intravesical cretostimogene grenadenorepvec (oncolytic serotype 5 adenovirus encoding granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor) with systemic nivolumab in cisplatin-ineligible patients with cT2–4aN0–1M0 muscle-invasive bladder cancer. The primary objective was to measure safety, and the secondary objective was to assess the anti-tumor efficacy as measured by pathologic complete response along with 1-year recurrence-free survival. No dose-limiting toxicity was encountered in 21 patients enrolled and treated. Combination treatment achieved a pathologic complete response rate of 42.1% and a 1-year recurrence-free survival rate of 70.4%. Pathologic response was associated with baseline free E2F activity and tumor mutational burden but not PD-L1 status. Although T cell infiltration was broadly induced after intravesical oncolytic immunotherapy, the formation, enlargement and maturation of tertiary lymphoid structures was specifically associated with complete response, supporting the importance of coordinated humoral and cellular immune responses. Together, these results highlight the potential of this combination regimen to enhance therapeutic efficacy in cisplatin-ineligible patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer, warranting additional study as a neoadjuvant therapeutic option. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04610671.

Radical cystectomy and pelvic lymph node dissection (RC-PLND) alone provides inadequate cancer control in patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC)1. The pivotal S8710 study2 and a subsequent meta-analysis3 consistently demonstrated 30–40% pathologic complete response (pCR) and 5% overall survival (OS) benefit associated with cisplatin-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy, helping to establish this regimen as the standard of care4. However, up to 50% of patients with MIBC are unable to receive chemotherapy due to various comorbidities5, thus creating a clinical unmet need for efficacious neoadjuvant systemic therapy in these patients. Recently, several early-phase clinical trials using neoadjuvant immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have preliminarily demonstrated safety and pCR ranging from 18% to 46% in patients with MIBC6–9. However, whether efficacy rates can be further improved using combination strategies with ICIs remains unknown.

Cretostimogene grenadenorepvec (CG0070) is a conditionally replicating double-stranded DNA (dsDNA)-based oncolytic serotype 5 adenovirus (Ad5) genetically engineered with its essential E1a gene placed under the control of the human E2F1 promoter. This genetic modification limits viral replication to retinoblastoma (Rb) pathway-altered tumor cells, in which the inhibitory binding of Rb to E2F1 is abrogated, freeing E2F1 to activate viral replication10. In addition to its tumor-specific replication, cretostimogene also selectively expresses the cytokine granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), which may boost cancer control both locally and systemically10. Intravesical delivery of cretostimogene was first tested in a phase 1 dose-escalation study enrolling 35 patients with non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC), demonstrating a tolerable safety profile along with evidence suggesting replication leading to clinical response11. In a subsequent phase 3 study enrolling 112 patients with Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG)-unresponsive carcinoma in situ (CIS), cretostimogene achieved 75.2% complete response (CR)12. Additionally, when used in conjunction with pembrolizumab in the same disease setting, cretostimogene achieved 82.9% CR with landmark CR rates of 77.3% (12 months) and 69.6% (24 months) on Kaplan–Meier estimation13,14.

Oncolytic immunotherapy (OIT) induces T cell influx into the tumor microenvironment through both innate15 and adaptive16,17 immune responses. We hypothesized that intravesical administration of cretostimogene could potentiate the efficacy of ICIs through (1) decreasing the immunosuppressive environment (from reduced tumor burden); (2) enhancing neoantigen presentation (from tumor cell lysis); and (3) creating a more permissive inflammatory environment for tumor-reactive T cells (from antiviral immune responses). Accordingly, we investigated the safety and efficacy of combined intravesical cretostimogene and nivolumab (anti-PD-1 inhibitor) in cisplatin-ineligible patients with MIBC. This phase 1b trial (NCT04610671) was a first in-human investigation of this combination.

Results

Patient characteristics and treatment

Cisplatin-ineligible patients diagnosed with cT2–4aN0–1M0 MIBC were assessed pre-treatment using cystoscopy to delineate the location of the tumor and subsequently treated with six weekly intravesical instillations of cretostimogene (1 × 1012 viral particles (vp)) and nivolumab (480 mg intravenous (IV)) at weeks 2 and 6 (Fig. 1a). Patients with concurrent upper urinary tract invasive urothelial carcinoma, prior ICI treatment, active autoimmune disease or other conditions that would cause unacceptable safety risk or potentially interfere with the completion of the treatment were deemed ineligible. Clinical re-staging after treatment consisted of computed tomography (CT) of the chest/abdomen/pelvis along with optional transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT) directed at the residual tumor/scar performed 3–4 weeks after treatment completion. RC-PLND was performed 2 weeks after re-staging TURBT. The primary endpoint was to assess the safety of the treatment according to National Cancer Institute (NCI) Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 5.0. Dose-limiting toxicities (DLTs) were assessed in the first six evaluable patients in a safety lead-in phase. The combination was declared tolerable if the incidence of DLTs was less than 33%, and the study was expanded. The secondary endpoints include pathologic complete (pT0N0) and partial (<pT2N0) response as well as recurrence-free survival (RFS) at 1 year after registration. The sample size was reduced from 30 to 21 through an amendment submitted on 7 December 2022 due to sponsor-directed drug re-allocation and agreement between the sponsor and the investigator that safety of the regimen and early efficacy signal had been established, allowing expedited planning for more definitive studies.

Fig. 1 |. Study design and clinical response of cisplatin-ineligible MIBC treated with neoadjuvant cretostimogene and nivolumab.

a, Study schema demonstrating the timing of neoadjuvant therapy, post-treatment assessment and radical cystectomy. Urine and peripheral blood samples were obtained before treatment at baseline, week 2 and week 6. b, Study CONSORT diagram. c, Individual pre-treatment clinical disease characteristics, treatment rendered and pathologic response for patients enrolled. d, Kaplan–Meier curve showing OS in the intention-to-treat population. One-year OS was 85.2% (95% CI: 71.1–100%). e, Kaplan–Meier curve showing the RFS in the intention-to-treat population. One-year RFS was 70.4% (95% CI: 53.0–93.4%). AE, adverse event; q1wk, once a week; q4wks, every 4 weeks.

Between 30 October 2020 and 1 March 2023, cisplatin-ineligible patients with MIBC were enrolled with baseline characteristics depicted in Table 1. All patients met cisplatin ineligibility criteria5 or declined chemotherapy. Treatment was terminated in one patient due to grade 3 acute kidney injury after one intravesical infusion of cretostimogene, which was deemed unrelated to treatment. Two additional patients declined post-treatment TURBT but successfully underwent RC-PLND. Disease progression was detected in two patients after treatment, prohibiting consolidation RC-PLND (Fig. 1b,c). One of the two patients underwent successful salvage chemotherapy followed by RC-PLND, demonstrating ypT3bN2 urothelial carcinoma.

Table 1 |.

Baseline clinicopathologic characteristics

| Age, years | |

| Median | 75 |

| Range | 53–86 |

| Sex (%) | |

| Male | 17 (81) |

| Female | 4 (19) |

| Variant subtype (%) | |

| Squamous | 5 (24) |

| Glandular | 2 (9.5) |

| Sarcomatoid | 1 (5) |

| Plasmacytoid | 2 (9.5) |

| Clinical stage baseline (%) | |

| T2 | 14 (68) |

| T3 | 6 (29) |

| T4 | 1 (5) |

| Reasons for cisplatin ineligibility (%) | |

| Renal insufficiency | 10 (48) |

| Hearing impairment | 8 (38) |

| Declined chemotherapy | 2 (9.5) |

| Neuropathy | 1 (7) |

Safety and efficacy

The treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) are listed in Table 2. No DLTs were encountered in the study. Grade 3 or higher TEAEs, most of which were due to complications from RC-PLND, occurred in 57% of patients. No patient experienced grade 3 or higher treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs). The most frequent TRAEs attributed to cretostimogene were grade 1/2 catheter leakage (24%), bladder spasms (14%) and dysuria (14%); those attributed to nivolumab were grade 1/2 fatigue (19%) and maculo-papular rash (14%). The most common immune-related adverse event (irAE) was grade 1/2 pruritis (28.5%). No patient experienced grade 3 or higher irAEs.

Table 2 |.

TEAEs per NCI CTCAE version 5.0

| Adverse Events | Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | Grade 5 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any adverse event | 2 (9.5) | 7 (33.3) | 10 (47.6) | 1 (4.8) | 1a (4.8) | 21 (100) |

| General disorders and administration site conditions | 15 (71.4) | 15 (71.4) | ||||

| Urinary tract infection | 10 (47.6) | 4 (19.0) | 14 (66.7) | |||

| Fatigue | 12 (57.1) | 12 (57.1) | ||||

| Bladder spasm | 6 (28.6) | 4 (19.0) | 10 (47.6) | |||

| Back pain | 8 (38.1) | 1 (4.8) | 9 (42.9) | |||

| Abdominal pain | 8 (38.1) | 8 (38.1) | ||||

| Constipation | 8 (38.1) | 8 (38.1) | ||||

| Hypokalemia | 4 (19.0) | 2 (9.5) | 2 (9.5) | 8 (38.1) | ||

| Nausea | 6 (28.6) | 1 (4.8) | 7 (33.3) | |||

| Vomiting | 6 (28.6) | 1 (4.8) | 7 (33.3) | |||

| Chills | 5 (23.8) | 1 (4.8) | 6 (28.6) | |||

| Flank pain | 6 (28.6) | 6 (28.6) | ||||

| Hematuria | 3 (14.3) | 2 (9.5) | 1 (4.8) | 6 (28.6) | ||

| Hypomagnesemia | 6 (28.6) | 6 (28.6) | ||||

| Hypophosphatemia | 1 (4.8) | 5 (23.8) | 6 (28.6) | |||

| Leukocytosis | 6 (28.6) | 6 (28.6) | ||||

| Rash maculo-papular | 5 (23.8) | 1 (4.8) | 6 (28.6) | |||

| Renal and urinary disorders | 5 (23.8) | 1 (4.8) | 6 (28.6) | |||

| Acute kidney injury | 3 (14.3) | 2 (9.5) | 5 (23.8) | |||

| Dysuria | 5 (23.8) | 5 (23.8) | ||||

| Fever | 4 (19.0) | 1 (4.8) | 5 (23.8) | |||

| Insomnia | 5 (23.8) | 5 (23.8) | ||||

| Investigations | 1 (4.8) | 2 (9.5) | 2 (9.5) | 5 (23.8) | ||

| Urinary incontinence | 5 (23.8) | 5 (23.8) | ||||

| Anemia | 4 (19.0) | 4 (19.0) | ||||

| Diarrhea | 4 (19.0) | 4 (19.0) | ||||

| Hypotension | 3 (14.3) | 1 (4.8) | 4 (19.0) | |||

| Infusion-related reaction | 1 (4.8) | 3 (14.3) | 4 (19.0) | |||

| Pruritus | 3 (14.3) | 1 (4.8) | 4 (19.0) | |||

| Urinary frequency | 4 (19.0) | 4 (19.0) | ||||

| Wound complication | 4 (19.0) | 4 (19.0) | ||||

| Anorexia | 3 (14.3) | 3 (14.3) | ||||

| Dehydration | 1 (4.8) | 2 (9.5) | 3 (14.3) | |||

| Edema limbs | 2 (9.5) | 1 (4.8) | 3 (14.3) | |||

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 2 (9.5) | 1 (4.8) | 3 (14.3) | |||

| Hypertension | 1 (4.8) | 2 (9.5) | 3 (14.3) | |||

| Infections and infestations | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) | 3 (14.3) | ||

| Non-cardiac chest pain | 3 (14.3) | 3 (14.3) | ||||

| Pain | 3 (14.3) | 3 (14.3) | ||||

| Sinus tachycardia | 3 (14.3) | 3 (14.3) | ||||

| Weight loss | 2 (9.5) | 1 (4.8) | 3 (14.3) | |||

| Alkaline phosphatase increased | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) | 2 (9.5) | |||

| Anxiety | 2 (9.5) | 2 (9.5) | ||||

| Arthralgia | 2 (9.5) | 2 (9.5) | ||||

| Atelectasis | 2 (9.5) | 2 (9.5) | ||||

| Atrial fibrillation | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) | 2 (9.5) | |||

| Chest pain (cardiac) | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) | 2 (9.5) | |||

| Creatinine increased | 2 (9.5) | 2 (9.5) | ||||

| Dizziness | 2 (9.5) | 2 (9.5) | ||||

| Dry mouth | 2 (9.5) | 2 (9.5) | ||||

| Dyspnea | 2 (9.5) | 2 (9.5) | ||||

| Erectile dysfunction | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) | 2 (9.5) | |||

| Fall | 2 (9.5) | 2 (9.5) | ||||

| Flatulence | 2 (9.5) | 2 (9.5) | ||||

| Generalized muscle weakness | 2 (9.5) | 2 (9.5) | ||||

| Genital edema | 2 (9.5) | 2 (9.5) | ||||

| Hyperhidrosis | 2 (9.5) | 2 (9.5) | ||||

| Hyperkalemia | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) | 2 (9.5) | |||

| Kidney infection | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) | 2 (9.5) | |||

| Muscle cramp | 2 (9.5) | 2 (9.5) | ||||

| Muscle weakness lower limb | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) | 2 (9.5) | |||

| Neoplasms benign, malignant and unspecified (incl. cysts and polyps) | 2 (9.5) | 2 (9.5) | ||||

| Paresthesia | 2 (9.5) | 2 (9.5) | ||||

| Penile pain | 2 (9.5) | 2 (9.5) | ||||

| Productive cough | 2 (9.5) | 2 (9.5) | ||||

| Rectal pain | 2 (9.5) | 2 (9.5) | ||||

| Sepsis | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) | 2 (9.5) | |||

| Sinus bradycardia | 2 (9.5) | 2 (9.5) | ||||

| Stomach pain | 2 (9.5) | 2 (9.5) | ||||

| Surgical and medical procedures | 2 (9.5) | 2 (9.5) | ||||

| Urinary retention | 2 (9.5) | 2 (9.5) | ||||

| Urinary tract pain | 2 (9.5) | 2 (9.5) | ||||

| Urinary urgency | 2 (9.5) | 2 (9.5) | ||||

| Abdominal distention | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) | ||||

| Acidosis | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) | ||||

| Alanine aminotransferase increased | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) | ||||

| Aspartate aminotransferase increased | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) | ||||

| Atrioventricular block first degree | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) | ||||

| Belching | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) | ||||

| Blurred vision | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) | ||||

| Cardiac disorders | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) | ||||

| Confusion | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) | ||||

| Cough | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) | ||||

| Delirium | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) | ||||

| Duodenal ulcer | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) | ||||

| Dysarthria | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) | ||||

| Dysgeusia | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) | ||||

| Flu-like symptoms | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) | ||||

| Flushing | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) | ||||

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) | ||||

| Headache | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) | ||||

| Hearing impaired | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) | ||||

| Heart failure | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) | ||||

| Hiccups | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) | ||||

| Hypermagnesemia | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) | ||||

| Hypertriglyceridemia | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) | ||||

| Hypoalbuminemia | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) | ||||

| Hypocalcemia | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) | ||||

| Hyponatremia | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) | ||||

| Hypothyroidism | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) | ||||

| Injury, poisoning and procedural complications | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) | ||||

| Intra-abdominal hemorrhage | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) | ||||

| Irritability | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) | ||||

| Lung infection | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) | ||||

| Lymph leakage | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) | ||||

| Malaise | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) | ||||

| Memory impairment | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) | ||||

| Metabolism and nutrition disorders | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) | ||||

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorder | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) | ||||

| Myalgia | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) | ||||

| Nail infection | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) | ||||

| Neck pain | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) | ||||

| Pharyngitis | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) | ||||

| Pleural effusion | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) | ||||

| Psychiatric disorders | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) | ||||

| Reproductive system and breast disorders | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) | ||||

| Respiratory failure | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) | ||||

| Respiratory, thoracic and mediastinal disorders | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) | ||||

| Scrotal pain | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) | ||||

| Testicular pain | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) | ||||

| Thromboembolic event | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) | ||||

| Toothache | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) | ||||

| Urine discoloration | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) | ||||

| Urostomy leak | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) | ||||

| Vaginal discharge | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) | ||||

| Vascular disorders | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) |

Grade 5 SAE not attributed to treatment.

Overall, 17 of 20 patients who successfully finished neoadjuvant treatment underwent RC-PLND (Fig. 1b), with a median of 82 d (range, 45–100 d) from treatment start to surgery. In addition to the two patients found to have progressive disease, another patient with clinical CR elected to forego RC-PLND. Post-surgical complication rates were similar to those previously described in RC-PLND series18, with no additional irAE attributed to neoadjuvant treatment (Table 2).

Of all evaluable patients, pCR (pT0N0) was 42.1% (eight of 19), and no patient achieved partial response (<pT2N0). Two additional patients were found to have disease downstaging within the bladder (pT1) but harbored pelvic nodal metastases (Fig. 1c). Overall, median follow-up was 27.3 months (95% confidence interval (CI): 24.7–35.9 months). Within the intention-to-treat population, four cancer-specific deaths occurred, with two other deaths unrelated to disease (1-year OS was 85.2%, 95% CI: 71.1–100%) (Fig. 1d); 1-year RFS was 70.4% (95% CI: 53.0–93.4%) (Fig. 1e).

Baseline free E2F activity and TMB predict pathologic response

The transcriptional activation of E1A is genetically engineered in cretostimogene to be under the control of the human E2F1 promoter (Fig. 2a). In addition, the oncolytic virus encodes the cDNA for GM-CSF. Importantly, only free E2F1 can drive viral replication, promoting selective infection of Rb-defective tumor cells. As such, we measured global gene expression of E2F targets as a surrogate for free E2F1 activity in the pre-treatment tumor samples as a biomarker for viral replication and treatment response. Indeed, pCR was associated with baseline E2F target gene expression levels (Fig. 2b). Furthermore, in non-responders, E2F target gene expression levels in the post-treatment tumors were significantly lower than those found in the corresponding pre-treatment tumors, suggesting the elimination of free E2F1-high tumor clones through treatment (Fig. 2c).

Fig. 2 |. Exploratory biomarker analyses based on the mechanism of action of the study agents.

a, Genetic construct of cretostimogene, a conditionally replicating dsDNA-based oncolytic adenovirus with the essential E1a gene genetically engineered under the control of a human E2F1 promoter, along with transgene encoding GM-CSF. b, Pre-ranked GSEA analysis using the hallmark gene sets revealed higher global expression of E2F targets in pre-treatment tumor samples from pathologic complete responders versus non-responders. NESs of GSEA are shown. Pathways were considered significant if FDR < 0.05. c, In pathologic non-responders, E2F target expression was decreased in the post-treatment samples, suggesting the elimination of free E2F1-high tumor clones through treatment. d, Using paired WES of the tumor and peripheral blood samples, somatic TMB was higher in the pathologic complete responders versus non-responders (**P = 0.0016). e, Baseline PD-L1 expression as measured by CPS was not significantly correlated with pCR (P = 0.37). f, Using fold change of urinary GM-CSF from pre-treatment to before second cretostimogene infusion as a surrogate measure, viral replication was found to correlate with baseline TMB (n = 18; Pearsonʼs correlation R2 = 0.34, *P = 0.012). ITR, inverted terminal repeat.

On the other hand, we hypothesized that higher tumor mutational burden (TMB) would lead to more abundant neoantigen targets, ultimately resulting in higher likelihood of treatment response. Indeed, higher somatic TMB, as referenced to germline controls, was detected from the baseline tumor samples of clinical responders (Fig. 2d). In contrast, baseline PD-L1 expression as measured by combined positive score (CPS) was not significantly correlated with response (Fig. 2e). As a readout of viral infection and replication, the fold change in the concentration of urinary GM-CSF was measured at weeks 1 and 2 as previously described11. Viral replication was found to correlate with baseline TMB (Fig. 2f) but not molecular subtype or free E2F activity (Extended Data Fig. 1).

OIT boosts local and systemic, neoantigen-specific T cell responses

Supporting our hypothesis that intravesical cretostimogene elicits anti-tumor immune responses, we found increases in urinary type I interferon-induced chemokines (CXCL9 and CXCL11) from baseline to week 2 (after OIT monotherapy), with higher levels maintained at week 6 (Fig. 3a). In contrast, cytokines with tumor-promoting potential (IL-6, IL-8 and TNF) were relatively stable throughout treatment (Fig. 3b). Correspondingly, there were consistent increases in infiltrating CD3+ as well as CD3+CD4+ and CD3+CD8+ T lymphocytes after treatment in samples obtained from both responders and non-responders (Fig. 3c). Notably, increases in total T cell infiltration were not associated with any pre-treatment tumor characteristics (TMB, baseline T cell infiltration or molecular subtype) or treatment response (Extended Data Fig. 2). We then interrogated the phenotypes of T cells via bulk RNA sequencing (RNA-seq). Although PDCD1 (PD-1) expression was elevated after treatment in all patients (Extended Data Fig. 3), expression of ENTPD1 (CD39), an ectonucleotidase previously shown to be a surrogate marker of tumor-reactive CD8+ T cells19, was found elevated after treatment only in patients with pCR (Fig. 3d). In contrast, no difference in the expression levels of other exhaustion markers, such as TNFRSF4, LAG3 or HAVCR2 (TIM3), was found (Extended Data Fig. 3). Together, these data suggest a generalized, early-onset, virally induced T-lymphocytic infiltration that fosters a tumor antigen-specific adaptive immune response in some patients16,17.

Fig. 3 |. T cell response associated with combined oncolytic virotherapy and ICIs.

a, Urinary type I interferon-induced T-lymphocyte-attracting chemokines (CXCL9 and CXCL11) were significantly increased at week 2 as compared to baseline (***P = 0.00026 for CXCL9 and ****P < 0.0001 (P = 3.81 × 10−6) for CXCL-11) after oncolytic immunotherapy and maintained at higher levels by week 6 after combination treatment in all patients (*P = 0.021 for CXCL9 and ***P < 0.001 (P = 0.000483) for CXCL-11). b, Pro-inflammatory cytokines with tumor-promoting potential (IL-6, IL-8 and TNF) were relatively stable throughout the neoadjuvant treatment course (IL-6: baseline versus week 2 P = 0.87, baseline versus week 6 **P = 0.003, week 2 versus week 6, **P = 0.0094; IL-8: baseline versus week 2 P = 0.956, baseline versus week 6 *P = 0.044, week 2 versus week 6, *P = 0.03; TNF: baseline versus week 2 P = 0.19, baseline versus week 6 P = 0.154, week 2 versus week 6 *P = 0.033). c, Consistent increases in the tumor-infiltrating CD3+ (*P = 0.01), CD3+CD4+ (*P = 0.04) and CD3+CD8+ (*P = 0.01) T lymphocytes were detected in the post-treatment samples from both responders and non-responders. d, Expression levels of ENTPD1 (CD39) on bulk RNA-seq were elevated after treatment only in patients with pathologic CR and not in those without response (NR) (**P = 0.003 for CR and P = 0.31 for NR). e, To measure systemic anti-tumor response, we used ELISpot analyses on PBMCs collected at various timepoints on-treatment, using autologous mature DCs pulsed with synthetic neopeptides predicted from WES and RNA-seq from pre-treatment tumor samples co-cultured with autologous T lymphocytes. f, The number of total neopeptides predicted from the baseline tumor samples was higher in responders than non-responders (**P = 0.0045). g, Systemic autologous T cell response against the predicted neopeptides was broadly boosted in the responders compared to non-responders at various on-treatment timepoints. Two-sided P values were calculated using Wilcoxon signed-rank test. For box plots shown in a–d and f: boxes represent median (center) and first and third quartile (bottom and top, respectively) values; Tukey whiskers represent the ±1.5 interquartile range (IQR); and individual data points are shown in dots. PanCK, pan-cytokeratin; Wk, week.

To quantify treatment-induced systemic neoantigen-specific T cell responses, we applied a pipeline to predict neoantigens in human cancer, previously refined by our team (Fig. 3e)20. In brief, we performed whole-exome and transcriptome sequencing on the pre-treatment tumors with paired germline and human leukocyte antigen (HLA) sequencing and predicted neoantigens derived from tumor non-synonymous alterations, including indels and translocations, with enhanced major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-I/II presentation for mutated peptides, compared to the non-mutated sequences. Across 17 pre-treatment tumor samples, we identified an average of 109 neopeptides (range, 2–1,414) per tumor. The number of predicted neopeptides was higher in the tumor samples from clinical responders (Fig. 3f). We then tested systemic reactivity against 3–7 neopeptides for autologous T cell recognition in each patient. As previously described20, custom-synthesized 8–14-mer neoantigen peptides predicted to be presented on MHC-I and 12–16-mer peptides on MHC-II were pulsed with autologous antigen-presenting cells (APCs) (autologous dendritic cells (auto-DCs)) and co-cultured with T cells collected at various timepoints on-study (Fig. 3g). A summary of all tested neoantigen peptides is shown in Supplementary Table 1. As expected, ELISpot analyses performed with peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) demonstrated that complete responders, contrary to non-responders, broadly experienced a boost in systemic T cell responses against predicted neoantigens presented on MHC-I and/or MHC-II molecules at either week 2 or week 6, in response to treatment (Fig. 3g and Extended Data Fig. 4). Therefore, combined OIT and ICI elicited systemic, polyclonal tumor-reactive cytotoxic T cell responses after treatment initiation, in association with therapeutic efficacy.

Oncolytic virus induces the formation of mature tertiary lymphoid structures

Recent studies in different human malignancies support the existence of coordinated cellular and humoral immune responses21. We hypothesized that T cell responses elicited by cretostimogene and nivolumab were synergistically associated with concurrent humoral anti-tumor immune responses. Supporting our hypothesis, we found increased number of tertiary lymphoid structures (TLSs) normalized to tissue surface area on whole-slide multiplex immunofluorescence images obtained from biopsy samples pre-treatment to post-treatment in responders (Fig. 4a) but not in non-responders (Extended Data Fig. 5a). Surprisingly, baseline TLS levels did not predict clinical response (Extended Data Fig. 5b). CXCL13, a key B cell-attracting and lymphoid structure-organizing chemokine, was increasingly detected within the urine after OIT uniformly in all patients (Fig. 4c), pointing to universal germinal center activity in response to OIT, with potential downstream immunosuppressive mechanisms or decreased antigenicity preventing TLS orchestration in the non-responders22.

Fig. 4 |. Combined OIT and ICI treatment induces the formation of mature TLSs.

a, On whole-slide multiplex immunofluorescence, the density of TLSs per unit of tissue surface area was found to be higher after treatment only in the pathologic complete responders (P = 0.07) and not in the non-responders (P = 0.34). b, Increase in the density of mature TLSs marked by dense B cell clusters adjacent to CD4/8 T cell conglomerates was significantly higher after treatment only in responders (**P = 0.0078) as compared to non-responders (P = 0.076). c, Urinary CXCL13 levels were uniformly increased after oncolytic immunotherapy and maintained at higher levels after combination treatment (**** P < 0.0001 (P = 1.34 × 10−5) at week 2 and **P = 0.004 at week 6). d, Density of CD138+ plasma cells was found to be higher in the TLSs on the post-treatment samples of responders (**P = 0.0078) as compared to non-responders (P = 0.082), indicating TLS maturation. Correspondingly, stromal CD138+ density was also found to be elevated only in the responders after treatment (P = 0.045) as compared to non-responders (P = 0.38). e, Isotype switching from IgM to IgA and IgG was found in the post-treatment samples from pathologic complete responders (P = 0.91 for IgM; **P = 0.003 for IgA; *P = 0.03 for IgG), further corroborating maturation of TLSs. Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used for statistical analyses using two-sided P values. For box plots shown in a–e: boxes represent median (center) and first and third quartile (bottom and top, respectively) values. PanCK, pan-cytokeratin; Wk, week.

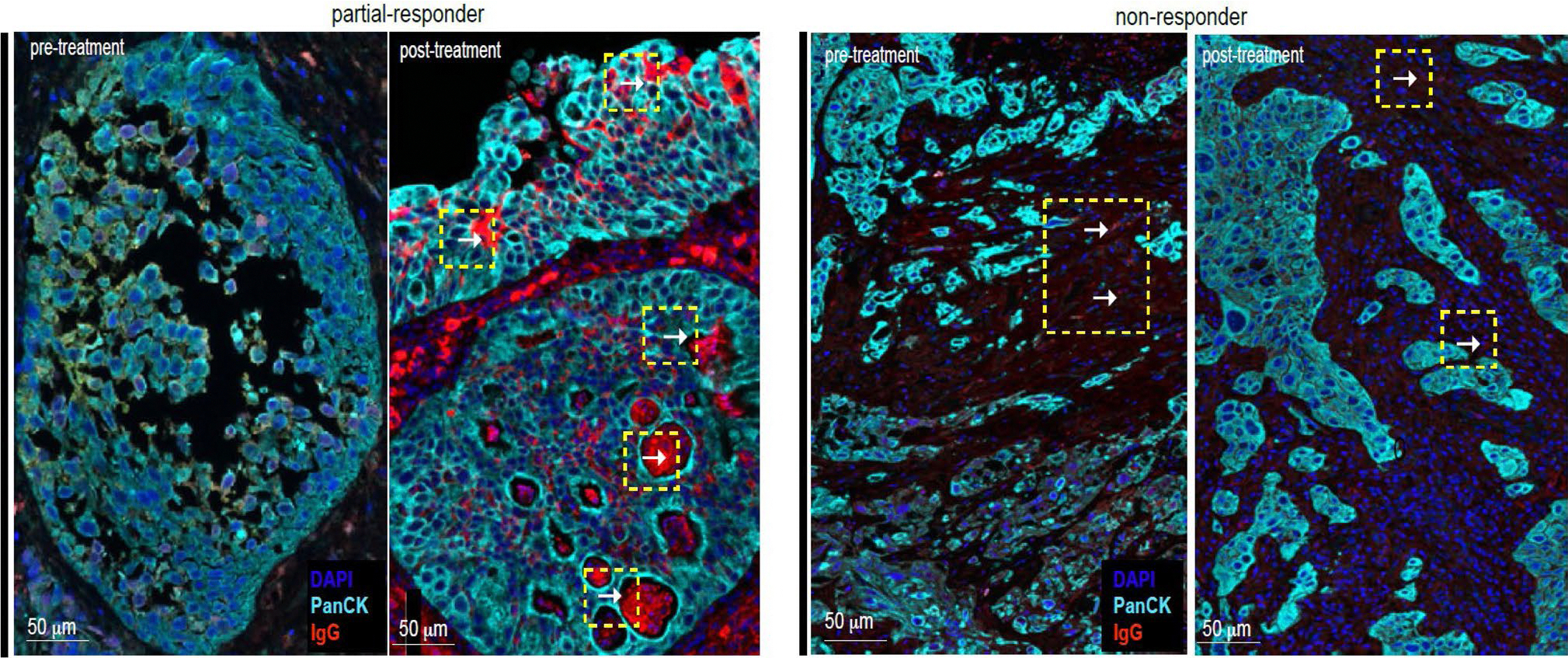

In particular, mature TLSs marked by dense B cell structures adjacent to CD4/8 T cell conglomerates were found to be more abundant after treatment in responders (Fig. 4b and Extended Data Fig. 6a) but not in non-responders (Extended Data Fig. 5a). These TLSs tended to have larger surface areas and cellular density compared to the pre-treatment TLSs (Extended Data Fig. 6b,c). In addition, in patients deriving pCR, we found increasing numbers of CD138+ plasma cells within the TLSs after treatment (Fig. 4b,d), further supporting that therapy elicited mature TLS formation. Therefore, clinical responses associated with combined OIT and ICI drive both de novo formation and maturation of TLSs at the tumor bed, presumably as a result of the buildup of antibody-producing cells.

TLS growth associated with proliferation of plasma cells

Plasma cells in responders were predominantly found in the periphery of TLSs after treatment (Fig. 4b,d). Corroborating earlier studies23, TLS maturation also led to the accumulation of infiltrating CD138+ plasma cells within the tumor bed but only in responders (Fig. 4d). Comparing the Ig isotype expressed by the B cells/plasma cells pre-treatment versus post-treatment in the responders, we found isotype switching from a predominant immature IgM profile to mature IgA/IgG post-treatment, indicative of treatment-induced enhanced B cell activation, in both TLSs and stromal plasma cells (Fig. 4e). Hence, the systemic T cell responses observed in responders are associated with concurrent humoral responses, which take place, at least in part, within the TLSs and are associated with superior therapeutic efficacy.

The observation of increased infiltrating Ig-producing plasma cells within the tumor bed after treatment prompted investigation of whether the antibodies produced are directed against the tumor cells. Of all pathologic complete responders, only one patient exhibited downstaging of disease (cTis) on the post-treatment biopsy before attaining pCR at the time of RC-PLND, thus offering a window to observe tumor specificity of the humoral response. Indeed, there was an increase in the density of TLSs (0.0151 per mm2 to 0.1815 per mm2) and stromal CD138+ plasma cells (122 per mm2 to 567 per mm2) observed in this patient after treatment. Using multiplex immunofluorescence, we observed coating of pan-cytokeratin+ tumor cells by IgG only in the post-treatment tumor specimen (Extended Data Fig. 7), suggesting treatment-induced, tumor-directed humoral response as previously described23,24.

Discussion

In this phase 1b study, we demonstrate that combined treatment using intravesical cretostimogene with systemic nivolumab for cisplatin-ineligible patients with MIBC is safe and efficacious. No DLT was encountered, with no treatment-related delay to RC-PLND, which is an important parameter in the treatment of MIBC. Along with its favorable safety profile, this combined intravesical and systemic immunotherapeutic strategy achieved a 42.1% pCR rate, similar to the 36–42% associated with standard-of-care neoadjuvant cisplatin-based chemotherapy2,25, as well as 37.5–46% with combined anti-PD-(L)1/CTLA-4 blockade6,9.

Although unravelling the contribution of components to toxicity and efficacy in single-armed combination trials such as ours is inherently difficult, it is nevertheless instructive to informally compare our results to those from previous neoadjuvant ICI trials enrolling cisplatin-ineligible patients with MIBC8,26–31. Most reported treatment abortion and RC-PLND completion rates similar to ours (Supplementary Table 2). On the other hand, the 42.1% pCR rate seen with OIT/ICI compared favorably to those from single-agent ICI trials (7–32%)8,26–31, especially those using nivolumab (7–17%)26,27,30. These reference efficacy rates suggest added benefit to local/regional cancer control mediated through intravesical OIT. However, the 1-year RFS of 70.4% was in line with the 64–73% range previously reported26,32,33, suggesting that the local disease control provided by way of the in situ vaccination from OIT/ICI may not translate into durable elimination of micrometastatic disease. This finding is somewhat counter to results from our ELISpot analysis, demonstrating augmented neoantigen-specific systemic response on-treatment in patients deriving pCR. Indeed, 1-year RFS was much higher in patients with pCR (87.5%, 95% CI: 67.3–100%). Ultimately, longer-term follow-up and additional translational investigations are needed to assess the true long-term benefit to systemic cancer control provided by combination neoadjuvant immunotherapy.

To understand the mechanism of synergistic anti-tumor activity between cretostimogene and nivolumab, we used surgeon-directed site-specific biopsy specimens obtained 3–4 weeks after treatment completion. Such sampling would otherwise be difficult to ascertain based on histologic examination at the time of RC-PLND, particularly in patients with pCR. Serendipitously, similar clinical re-staging after neoadjuvant treatment was recently shown by Galsky et al.34 as a potential tool for selecting patients to avoid RC-PLND. From our analyses, combination of intravesical and systemic immunotherapy elicited potent, coordinated cellular and humoral anti-tumor immune responses in some, which were associated with complete pathologic response. Together, these results highlight the potential of OIT in conjunction with ICI to enhance the therapeutic efficacy in patients with MIBC, offering new hope for those ineligible to receive cisplatin-based treatments.

It is well established that OIT leads to an influx of T cells both through direct tumor lysis causing immunogenic cell death as well as via recruitment by cross-presentation of tumor-associated antigens on licensed APCs35. It is notable that, in contrast to previous studies using neoadjuvant ICI monotherapy7,8, pCR rate was numerically higher in the PD-L1− patients, suggesting the ability of OIT to convert some immune cold tumors to respond to ICI. In the setting of bladder cancer, cytokine profiling of urine samples collected on-treatment recapitulates in real time the progressive inflammatory milieu engendered within the tumor bed. Furthermore, we demonstrate that clinical treatment response correlated with baseline TMB, increased tumor-reactive CD8+ T cells as surrogated by ENTPD1 expression19 and systemic neoantigen-specific immune response unleashed during the course of treatment. Immune reactivity as measured by IFN-γ production on ELISpot assays was heightened on-treatment against neopeptides predicted to be presented on both MHC-I and MHC-II molecules, corroborating findings from previous seminal work highlighting the role of CD4+ cytotoxic T cells in the spontaneous immune protection against bladder cancer36.

Furthermore, CD4+ Tfh cells are known to play an important role in the orchestration and maintenance of TLSs37 as well as facilitating their maturation via isotype switching38, linking them to one of the most intriguing findings in our study—that OIT plus ICI stimulated both de novo formation of TLSs and enlargement and maturation of pre-existing TLSs in responders to therapy. TLSs are follicle-like ectopic lymphoid organs that develop in non-lymphoid tissues at sites of chronic inflammation39,40. Because of the early recognition of their importance within solid tumors40, TLSs have been linked to favorable prognosis in several cancer types39,41,42 as well as response to ICI43–45. Their predictive significance in the setting of neoadjuvant immunotherapy in MIBC seems to be mixed: whereas some described higher prevalence linked with response6, others found the opposite9. The discrepancy was attributed to the presence of tumor-agnostic TLSs located in the superficial layers beneath the urothelium46. Indeed, we also did not find baseline TLS density to be a reliable biomarker for treatment response. Rather, it was the proliferation of TLSs (in number, size and maturity) that was correlated with response. It is tempting to speculate that it was the intravesical OIT that instigated the formation and maturation of the TLSs within the superficial layers of the bladder wall, which, in turn, potentiated response to ICI. On the other hand, we observed increases in the plasma cell population producing isotype-switched IgG and IgA accumulate in the periphery of the TLSs, along with IgG coating of the receding tumor islet in a transient partial responder. This points to the onset of anti-tumor humoral immunity, which could serve, in part, as the basis for the observed clinical efficacy achieved as well as may be essential for a durable response. Although provocative, these results need further validation in larger sample sets. Notwithstanding, long-term follow-up of our clinical responders and future trials may help define the relative contribution of cellular versus humoral immune responses to the observed outcomes. In addition, TLS-derived antibodies could also be engineered for novel immunotherapies, if recombinant antibodies generated with clonally enriched VH/VL sequences show exclusive reactivity against tumor cell surface proteins.

Our study is not without limitations. First, one question that has yet to be fully addressed is why TLSs were formed in some patients but not others. As shown here, the degree of viral infection and replication, dependent on baseline tumor characteristics such as TMB, may have played a role. Alternatively, the immunosuppressive burden within the tumor microenvironment may have proven too much to overcome, impeding the orchestration and maturation of TLSs, which ultimately led to disease progression. Further dissecting the mechanism(s) of resistance may yield knowledge on how best to improve upon the currently available therapeutic regimen. Second, the cognate antigen for the proliferating and maturing antibody-producing lymphocytes within the TLS is unknown. Understanding whether the antibody is targeted against oncolytic viral protein(s) versus tumor-associated antigen(s) will be critically important in designing novel immunotherapeutic strategies against bladder cancer. Third, despite repeated demonstrations of correlation43–45, the precise mechanism linking the formation of TLSs to clinical response after ICI has yet to be fully resolved. Recently, Ng et al.47 found that envelope glycoproteins of endogenous retroviruses (ERVs) were the dominant targets of antibodies produced from TLSs associated with lung adenocarcinoma. Furthermore, the anti-tumor activity exerted by the ERV-reacting antibodies was amplified by ICI, providing a mechanistic explanation to why the presence of TLSs predicted ICI treatment response. Whether similar mechanisms of action underpin the synergism between cretostimogene and nivolumab is yet to be determined. Finally, although our study demonstrates the safety of the therapeutic combination, it was not sufficiently powered to investigate clinical efficacy, and the results should be interpreted accordingly. The translational correlates, although striking, should also be viewed as exploratory, and they require validation. Previous clinical studies demonstrated similar pCR rates after neoadjuvant ICI, albeit in cisplatin-eligible patients. Nevertheless, based on the preliminary efficacy results, conceptualization of phase 2/3 studies using similar combinations are currently ongoing.

In conclusion, neoadjuvant intravesical cretostimogene combined with nivolumab was safe and yielded pCR of 42% in cisplatin-ineligible patients with MIBC, similar to response rates seen from standard-of-care cisplatin-based chemotherapy. With its favorable tolerability profile, this combination may be more easily deployed in the neoadjuvant setting than other regimens demonstrating similar efficacy, such as chemotherapy or combined anti-PD-(L)1/CTLA-4 blockade. We found that treatment response associated with baseline free E2F levels and TMB. Combination immunotherapy elicited potent cellular and humoral anti-tumor immunity.

Online content

Any methods, additional references, Nature Portfolio reporting summaries, source data, extended data, supplementary information, acknowledgements, peer review information; details of author contributions and competing interests; and statements of data and code availability are available at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-024-03324-9.

Methods

Study design

This is a single-arm, phase 1b, open-label clinical trial for patients with MIBC (cT2–4), with and without pelvic lymphadenopathy (cN0–1) and no evidence of distant metastases (cM0) who are cisplatin ineligible or who refused cisplatin before radical cystectomy. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Moffitt Cancer Center (MCC) ethics committee, with written informed consented provided by all patients before enrollment. The trial is sponsored by CG Oncology and was approved by the MCC institutional review board (IRB) (MCC20575) and registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT04610671). The primary objective was to test the safety of this drug combination, assessed per NCI CTCAE version 5.0. DLTs were assessed in six DLT-evaluable patients in a safety lead-in phase. The combination was declared tolerable as the incidence of DLTs was less than 33%, and the study expanded to 30 total patients. Secondarily, clinical measures of efficacy related to the drug combination will be assessed. An amendment in December 2022 reduced the sample size to 21 patients due to sponsor-directed drug re-allocation and agreement between the sponsor and the investigator that safety of the regimen and early efficacy signal had been established, allowing expedited planning for more definitive studies.

Patients

Patients were cisplatin ineligible as per the following definition: glomerular filtration rate < 60 ml min−1, chronic heart failure New York Heart Association (NYHA) class III or higher, peripheral neuropathy grade 2 or higher, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group score ≥ 2 or impaired hearing. Patient’s refusal of traditional chemotherapy was also included. Other inclusion/exclusion criteria are outlined in the protocol (Supplementary Information). During screening, patients were evaluated by a surgeon to determine eligibility for RC-PLND; they also underwent complete tumor staging using CT of the thorax/abdomen/pelvis or non-contrast CT/MRI (in case of poor renal function). Screening cystoscopy was performed at baseline to evaluate location of the tumor and residual tumor burden. All patients provided informed consent. Patient sex, as determined based on self-report, was not factored into study accrual. The sex distribution seen was reflective of that for MIBC.

Inclusion criteria.

Patients must have histologically confirmed MIBC (cT2-T4a, N0-N1, M0 per American Joint Commission on Cancer) pure or mixed histology urothelial carcinoma. Clinical node-positive (N1) patients are eligible provided the lymph nodes are within the planned surgical dissection template.

The initial TURBT that showed muscularis propria invasion should be within 90 d before beginning study therapy. Patients must have sufficient baseline tumor tissue from either initial or repeat TURBTs. The local site pathologist will be asked to estimate and record the rough approximate percentage of viable tumor in the TURBT sample (initial or repeat TURBT with highest tumor content) to document at least 20% viable tumor content before registration. This is to ensure that adequate tissue is available to perform tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cell assessment.

-

Patients must be ineligible for cisplatin-based chemotherapy due to any of the following:

Creatinine clearance (CrCl) < 60 ml min−1 (with ECOG performance status 0–1)

Hearing impaired ≥grade 2 by CTCAE criteria

Neuropathy ≥grade 2 by CTCAE criteria

Heart failure NYHA ≥ III

ECOG ≥ 2

Refusing to undergo cisplatin chemotherapy

Patients must be medically fit for TURBT and radical cystectomy.

Age ≥18 years.

Ability to understand and willingness to sign IRB-approved informed consent.

Willing to provide tumor tissue, blood and urine samples for research.

-

Adequate organ function as measured by the following criteria, obtained ≤4 weeks before registration:

Absolute neutrophil count ≥ 1,000 mm3 (stable off growth factor within 4 weeks of first study drug administration)

Platelets ≥ 100,000 per mm3

Hemoglobin ≥ 8 g dl−1

Serum creatinine clearance ≥ 20 ml min−1 using the Cockcroft–Gault formula

ALT and AST ≤ 2.5× the upper limit of normal (ULN)

Total bilirubin ≤ 1.5× ULN (in the absence of diagnosed Gilbert’s disease)

Exclusion criteria.

Patients who are pregnant or breastfeeding, because the effects of nivolumab and cretostimogene on the fetus or breastfeeding child are unknown. All sexually active females of childbearing potential (not surgically sterilized and between menarche and 1 year after menopause) must have a blood test to rule out pregnancy within 4 weeks before registration.

Patient with local symptoms from bladder cancer (that is, gross hematuria, dysuria, etc.) who are deemed to be unable to complete the treatment protocol.

-

Patients with active or prior documented autoimmune disease within the past 2 years before screening or other immunosuppressive agent within 14 d of study treatment.

Note: Patients with well-controlled type 1 diabetes mellitus, vitiligo, Graves disease, Hashimoto’s disease, eczema, lichen simplex chronicus or psoriasis not requiring systemic treatment (within the past 2 years before screening) are not excluded.

Patients who have concurrent upper urinary tract (that is, ureter and renal pelvis) invasive urothelial carcinoma. Patients with history of non-invasive (Ta, T1 and Tis) upper tract urothelial carcinoma that has been definitively treated with at least one post-treatment disease assessment (that is, cytology, biopsy or imaging) that demonstrates no evidence of residual disease are eligible.

-

Patients who have another malignancy that could interfere with the evaluation of safety or efficacy of the study drugs. Patients with a prior malignancy will be allowed without principal investigator approval in the following circumstances:

Not currently active and diagnosed at least 3 years before the date of registration

Non-invasive diseases, such as low-risk cervical cancer or any cancer in situ

Localized (early-stage) cancer treated with curative intent (without evidence of recurrence and intent for further therapy) and in which no chemotherapy was indicated (for example, low/intermediate risk prostate cancer). Patients with other malignancies not meeting these criteria must be discussed before registration.

Patients who have received any prior ICI (that is, anti-KIR, antiPD-1, anti-PD-L1, anti-CTLA4 or other).

Patients who have undergone major surgery (that is, intra-thoracic, intra-abdominal or intra-pelvic), open biopsy or major traumatic injury or specific anti-cancer treatment ≤4 weeks before starting study drug or patients who have had placement of a vascular access device ≤1 week before starting study drug or who have not recovered from side effects of such procedure or injury.

-

Patients who have clinically significant cardiac diseases deemed not fit for radical cystectomy, including any of the following:

History or presence of serious uncontrolled ventricular arrhythmias

Clinically significant resting bradycardia

Any of the following within 3 months before starting study drug: severe/unstable angina, congestive heart failure, cerebrovascular accident and transient ischemic attack

Uncontrolled hypertension defined by systolic blood pressure ≥ 180 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 100 mmHg, with or without anti-hypertensive medication(s)

Patients who have history of chronic active liver disease or evidence of acute or chronic hepatitis B virus or hepatitis C virus.

Patients who have known diagnosis of HIV infection. Testing is not required in the absence of clinical suspicion.

Patients who have known diagnosis of any condition (for example, post-hematopoietic or solid organ transplant, pneumonitis, inflammatory bowel disease, etc.) that requires chronic immunosuppressive therapy that cannot be stopped for the duration of the clinical trial. Usage of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for the treatment of osteoarthritis and uric acid synthesis inhibitors for the treatment of gout are permitted.

Patients with any serious and/or uncontrolled concurrent medical conditions (for example, active or uncontrolled infection, uncontrolled diabetes) or psychiatric illness that could, in the investigator’s opinion, cause unacceptable safety risks or potentially interfere with the completion of the treatment according to the protocol.

Patients who have used any live viral vaccine for prevention of infectious diseases within 4 weeks before study drug(s). Examples of live vaccines include, but are not limited to, the following: measles, mumps, rubella, varicella/zoster (chicken pox), yellow fever, rabies, BCG and typhoid vaccine. Seasonal influenza vaccines for injection are generally killed virus vaccines and are allowed; however, intranasal influenza vaccines (for example, FluMist) are live attenuated vaccines and are not allowed.

Patients unwilling or unable to comply with the protocol.

Patients with a known allergy to any of the study medications, their analogues or excipients in the various formulations of any agent.

Patients who participate in any other therapeutic clinical trials, including those with other investigational agents not included in this trial throughout the duration of this study.

Use of excluded antiviral medication that cannot be suspended at least 14 d before and for 14 d after the administration of any cretostimogene treatment throughout the duration of the trial.

Treatment

Intravesical cretostimogene was administered within 90 d from the biopsy demonstrating MIBC, and, in the absence of hematuria/traumatic catheterization, all patients received sterile placement of a Foley catheter, with instillations of 0.1% dodecyl β-d-maltoside (DDM) and 1 × 1012 vp of cretostimogene in 100 ml of normal saline. Intravesical dwell time was maintained at 1 h as tolerated. The patient was monitored for an additional hour for safety evaluations and the collection of protocol-specified research samples. Cretostimgene (1 × 1012 vp) was administered weekly for 6 weeks, and nivolumab (480 mg IV) was administered at weeks 2 and 6. In the event of cretostimogene dose holds, dosing was resumed at the next pre-specified protocol timepoint. Cretostimogene doses were held for grade 3 or higher serious adverse events (SAEs) as well as those thought to be clinically significant or likely to impair the efficacy of treatment. In the event of dose delays or discontinuations of cretostimogene, receipt of nivolumab was still permitted per protocol. A post-treatment TURBT was strongly recommended within 3–4 weeks of treatment completion. RC-PLND occurred 2 weeks after post-treatment TURBT. All patients were followed clinically and radiographically per standard of care after radical cystectomy. Pre-treatment, on-treatment and post-treatment blood, urine and tissue samples were collected for correlative biological analyses per an IRB-approved laboratory protocol (MCC 22288).

GM-CSF expression

To measure GM-CSF levels after cretostimogene treatment, primary urine samples from eligible patients were collected at different timepoints including at baseline, week 2 and week 6 pre-treatment. Urine specimens were spun down at 10,000g, and supernatants were saved for ELISA assays. For the ELISA experiments, a Quantikine HS Human GM-CSF kit was used (R&D Systems/Biotechne, cat. no. HSGMO). The assay was performed in triplicate and according to the manufacturer’s recommendations.

Olink analysis on urine samples

Urine samples were analyzed for the presence of inflammation and immuno-oncology-related proteins using the Olink Target 96 inflammation, immuno-oncology and oncology assays (Olink). In short, these measurements are based on proximity extension assay (PEA) technology, which enables high-throughput multiplex immunoassays of proteins using 1 μl of urine. Normalized protein expression (NPX) median-based intensity-normalized data provided by Olink were used for data analysis. Samples not passing quality control were removed. Assays were excluded if less than 20% of the samples were above the limits of detection (LODs). LODs for assays ranged between −0.53 and 4.98.

Immunohistochemistry with anti-PD-L1 antibodies

Immunohistochemistry of PD-L1 was performed using 22C3 pharmDX antibodies on a Dako Autostainer Link 48 using 5-μm-thick tissue sections according to the technical manual. For each case, three serial sections were cut. One section was stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) to evaluate the presence of adequate numbers of viable tumor cells; one section was stained with the PD-L1 antibody; and one section was stained with a negative reagent control (NRC). Each slide also contained a negative and a positive in-house control. Slides were independently evaluated by a trained genitourinary pathologist (J.D.). Controls were examined, first, to invalidate any slide with unwanted staining. Slides were examined at ×200 magnification. Necrotic and apoptotic tumor cells, plasma cells, neutrophils and fibroblasts were not evaluated.

A CPS equal to or greater than 10 was considered positive.

Fluorescent multiplex immunohistochemistry panel

Formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue samples were immune-stained using an OPAL 7-Color Automation IHC kit (Akoya Biosciences) on a BOND RX auto-stainer (Leica Biosystems). The OPAL 7-Color kit uses tyramide signal amplification (TSA) conjugated to individual fluorophores to detect various targets within the multiplex assay. Sections were baked at 65 °C for 1 h and then transferred to the BOND RX. All subsequent steps (for example, deparaffinization and antigen retrieval) were performed using an automated OPAL immunohistochemistry procedure (Akoya Biosciences). OPAL staining of each antigen occurred as follows. Heat-induced epitope retrieval (HIER) was achieved with citrate pH 6.0 buffer for 20 min at 95 °C before the slides were blocked with Akoya blocking buffer for 10 min. Then, slides were incubated with primary antibody, CD138 (Abcam, EPR6454, 1:700, dye 620), at room temperature for 60 min, followed by OPAL HRP polymer and one of the OPAL fluorophores during the final TSA step. Individual antibody complexes are stripped after each round of antigen detection. This was repeated five more times using the following antibodies: CD8 (Dako, C8/144B, HIER-EDTA pH 9.0, 1:50, dye520), CD4 (CM, EP204, HIER-EDTA pH 9.0, 1:100, dye570), CD20 (Dako, L26, HIER-EDTA pH 9.0, 1:300, dye 480), CD3 (Dako, Rb poly, HIER-EDTA pH 9.0, 1:100, dye690) and PCK (Dako, AE1/AE3, HIER-citrate pH 6.0, 1:150, dye780). Additional multiplex immunohistochemistry panels were developed using the following antibodies: PIGR (Abcam, Rb poly 1:50), IgM (Abcam, IM260 1:50), IgA (Abcam, Rb poly, 1:1,000) and IgG (Abcam, EPR4421, 1:300). After the final stripping step, DAPI counterstain was applied to the multiplexed slide and was removed from BOND RX for cover-slipping with ProLong Diamond Antifade Mountant (Thermo Fisher Scientific). All slides were imaged with the Vectra 3 Automated Quantitative Pathology Imaging System.

Quantitative image analysis

Multi-layer TIFF images were spectrally unmixed in InForm version 2.6.0 (Akoya Biosciences) and imported into HALO (Indica Labs) for quantitative image analysis. Each image was annotated by an experienced image analysis specialist to identify individual TLS objects by manual creation of regions of interest around areas consisting of a dense co-clustering of CD3+ and CD20+ cells with an emphasis on the CD20 cell density. Manual scoring was also performed on each TLS to categorize them into immature and mature structures (Extended Data Fig. 5). Criteria for scoring included overall cell density (DAPI channel), shape (distribution of CD3/CD20 cells into circular or ovular formation) and size (greater than 5,000 μm2). Immature TLS scoring consisted of less dense structures with unremarkable and undefined shape, whereas mature TLSs were identified as very dense structures highly populated with CD20+ with well-defined shape and morphology. Automated segmentation of tumor, stroma and non-tissue regions was performed on the whole tissue image by training a classifier using the pan-cytokeratin channel as a tumor region marker. The classifier was created and tested on various images in the image set. The tissue was segmented into individual cells using the DAPI marker that stains cell nuclei. For each marker, a positivity threshold within the nucleus or cytoplasm was determined per marker based on published staining patterns and intensity for that specific antibody. After setting a positive fluorescent threshold for each staining marker, the TLS, tumor and stroma regions for the entire image set were analyzed with the created algorithm. The generated data include positive cell counts for each fluorescent marker in cytoplasm or nucleus and percent of cells positive for the marker. Along with the summary output, a per-cell analysis can be exported to provide the marker status, classification and fluorescent intensities of every individual cell within an image. The following table describes the fluorescent antibodies used for the TLS panel.

| Reagent | Lot no. | Product no. | OPAL | Clone | Dilution | Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target Antibody 1CD138 | 1009209-1 | ab128936 | OPAL-620 | EPR6454 | 1:700 | Abcam |

| Target Antibody 2CD8 | 41527763 | M7103 | OPAL-520 | C8/144B | 1:50 | Dako |

| Target Antibody 3CD4 | 186600 | 104R-25 | OPAL-570 | EP204 | 1:50 | Cell Marque |

| Target Antibody 4CD20 | 20042864 | M0755 | OPAL-480 | L26 | 1:300 | Dako |

| Target Antibody 5CD3 | 41495387 | A0452 | OPAL-690 | Rb poly | 1:100 | Dako |

| Target Antibody 6PCK | 11478870 | M3515 | OPAL-780 | AE1/AE3 | 1:150 | Dako |

The following table describes the fluorescent antibodies used for the Ig panel.

| Reagent | Lot no. | Product no. | OPAL | Clone | Dilution | Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target Antibody 1PIGR | GR3357008-9 | ab96196 | OPAL-480 | Rb poly | 1:50 | Abcam |

| Target Antibody 2CD20 | 20042864 | M0755 | OPAL-570 | L26 | 1:200 | Dako |

| Target Antibody 3IgM | GR3345045-2 | ab200541 | OPAL-620 | IM260 | 1:50 | Abcam |

| Target Antibody 4IgA | GR271550-17 | ab97216 | OPAL-520 | Rb poly | 1:1,000 | Abcam |

| Target Antibody 5IgG | GR3258727-10 | ab109489 | OPAL-690 | EPR4421 | 1:300 | Abcam |

| Target Antibody 6PCK | 11375363 | M3515 | OPAL-780 | AE1/AE3 | 1:150 | Dako |

Tissue preparation followed by DNA and RNA extraction

Tissues were fixated by placing them in 10% neutral buffered formalin within 15 min of collection and fixed for 24 h before embedding in paraffin using standard methodologies. Sections (4 μm) from each FFPE tissue were stained with H&E and reviewed by the study pathologist (J.D.) to ensure tumor content. Scrolls (3–5, 20-μm sections) from each FFPE block were used for total RNA extraction using an RNeasy FFPE kit (Qiagen, 73504) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA quality was assessed using Qubit Fluorometric Quantification (Invitrogen) and TapeStation 4200 (Agilent Technologies).

Tissues were snap frozen within 15 min of collection and stored in liquid nitrogen until processing. Sections (4 μm) from each frozen sample were stained with H&E and reviewed by the study pathologist to ensure tumor content. Then, 30 mg of tissue was macrodissected to enrich for tumor and used for total DNA extraction using a DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen, 69504) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA quality was assessed using Qubit Fluorometric Quantification and TapeStation 4200.

RNA-seq data analysis

The raw RNA-seq reads were first assessed for quality using FastQC. Quality trimming was performed using Cutadapt48 to remove reads with adaptor contaminants and low-quality bases. Read pairs with either end too short (<25 bp) were discarded from further analysis. Next, trimmed and filtered reads were aligned to the human transcriptome GRCh37 using STAR49. Gene expression was quantified as transcripts per million (TPM) using RSEM50. Batch effects were corrected with Combat51, and differential expression analysis was performed by limma on the log-transformed batch-corrected TPM values (Extended Data Fig. 2; RNA-seq). Genes were then ranked based on −log10(P value) × (sign of log2(fold change)), such that the most upregulated genes were at the top and the most downregulated ones were at the bottom. The pre-ranked gene list was used to perform pre-ranked gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA52 version 4.0.2) to assess enrichment of hallmarks, curated gene sets and Gene Ontology53 terms in the Molecular Signatures Database52,54. The resulting normalized enrichment score (NES) and false discovery rate (FDR)-controlled P values were used to assess transcriptome changes. Additionally, we employed non-negative matrix factorization (NMF)-based methodologies to delineate the molecular subtypes within tumors, using log-transformed and median-centralized TPM values. In brief, a collection matrix (WTCGA) of 354 subtype-specific differentially overexpressed marker genes and their weights to the five subtypes (Luminal, Luminal-Infiltrated, Basal-Squamous, Neuronal and Luminal-Papillary) were identified from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) advanced urothelial cancers through unsupervised clustering55. Using the NMF-based subtype classification model, the bladder cancer subtype for each tumor was determined by approximating , where represents the tumor gene expression and H represents the subtype weight vector. The classification was carried out using the R package ADAPTS56 employing non-negative least squares deconvolution.

Somatic mutations identification and profiling

Somatic mutations were identified from whole-exome sequencing (WES) of matched tumor and normal samples following the strategies described in TCGA’s Multi-Center Mutation Calling in Multiple Cancers project (MC3 project)57. Short reads were aligned to human reference genome GRCh37 using the Burrows–Wheeler Aligner (BWA58) and then improved by base quality score recalibration, sequence realignment near indels and duplicate read removal using the Genome Analysis Tool Kit version 4 (GATK59) and Picard. SAMSTAT60 and Picard were used for quality checking of the aligned BAM files. Somatic mutations were further detected from the recalibrated BAM using a combination of Mutect2 (ref. 60), SomaticSniper61, MuSe62, FreeBayes63, Pindel64 and Strelka65 with default settings. Mutations with reported variant allele frequency (VAF) > 0.01 in external databases, including the 1000 Genomes Project66, the NHLBI Exome Sequence Project (ESP) and the Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC)67, were considered germline-inherited variations and were removed from further analysis. Only point mutations and indels predicted by at least two algorithms were included for subsequent analysis. Additional annotations were added from COSMIC68, ExAC67, dbGAP69 and Ensembl70 using ANNOVAR71. The identified somatic mutations were further analyzed and visualized using the R package Maftools72. TMB was calculated as number of non-synonymous mutations for each tumor. Genes under positive selection as putative oncogenic drivers were identified using dNdScv73. Four genes (TP53, RB1, ARID1A and KMT2D) with a global q value (qglobal_cv) less than 0.15 were considered significant. Mutational signatures were identified by evaluating patterns of nucleotide substitutions using an NMF-based method implemented in Maftools. The top four signatures that optimally represented the mutation profile were extracted and matched to the SBS signature database74.

Neoantigen prediction

Neoantigens were predicted from somatic mutations detected as described above. The four-digit patient-specific HLA haplotypes were determined in silico using arcasHLA75 (RNA-seq), hlahd76 (WES) and T1K77 (both). All non-synonymous somatic mutations identified above were translated into 8–14-mer peptides flanking the mutant amino acid for MHC-I and 12–16-mer peptides flanking the mutant amino acid for MHC-II neoantigens. Only the mutated sequences with TPM ≥ 1 in tumor RNA-seq data were further analyzed to predict MHC–peptide binding affinity against patient-specific HLA type using NetMHCpan78 for MHC-I and NetMHCIIpan79 for MHC-II. Neoantigen burden was the calculated number of 25-mer mutated peptides with any 9–14-mer or 12–16-mer predicted with higher binding compared to their reference counterparts for either MHC-I or MHC-II.

Neopeptide prioritization

We used a two-pass approach to prioritize neopeptides. First, the 25-mer mutated peptides were prioritized based on expression and MHC binding prediction analyses to obtain an additive score (AS) as previously described80. The expression score (ES) component was determined by using the maximum VAF in the RNA-seq data and fragments per kilobase of exon per million mapped fragments (FPKM) obtained from the RNA-seq data. Additionally, the MHC combined score (MCS) component incorporated the maximum predicted binding of each peptide to the patient’s MHC molecules, along with the differential agretopicity index (DAI) between the variant (var) peptide and its corresponding reference (ref) peptide for both MHC-I (mhc1) and MHC-II (mhc2). The complete formula for the AS prioritization of 25-mers is provided below:

In the second pass, within the top 25-mer peptides prioritized, the binding of each 9–14-mer or 12–16-mer neopeptides and their reference counterparts to MHC-I and MHC-II were evaluated as strong binding (SB), weak binding (WB) and no binding (NB) based on %Rank score generated by NetMHCpan and NetMHCIIpan. %Rank < 0.5% and %Rank < 2% thresholds were considered for detecting SBs and WBs for MHC-I, and %Rank < 2% and %Rank < 10% thresholds were considered for detecting SBs and WBs for MHC-II. %Rank ≥ 2% and %Rank ≥ 10% were considered as NBs for MHC-I and MHC-II, respectively. We then chose the best 9–14-mer neopeptides for MHC-I and the best 12–16-mer neopeptides for MHC-II using following criteria: (1) when a neopeptide was classified as SB, the reference form of the neopeptide was required to be either NB or WB with log2(IC50 of reference / IC50 of neopeptide) > 1.2; (2) when a neopeptide was classified as WB, the reference form of the neopeptide was required to be NB.

ELISpot assays to quantify the systemic reactivity

A detailed schema is shown in Fig. 3d. PBMCs from enrolled patients were collected at baseline, week 2 and week 6 pre-treatment.

Generation of auto-DCs.

The plastic adherence method was used to generate monocyte-derived DCs according to published protocol with some modifications20. In brief, approximately 6–9 × 106 PBMCs were suspended in AIM-V medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and seeded in tissue culture plates of an appropriate size. Cells were then incubated in a humidified 37 °C 5% CO2 incubator for 2 h. The non-adherent cells (CD14−, a source of T cells) were collected and cryopreserved in LN2. Adherent cells were washed with AIM-V medium twice with an interval of 60 min, after which DC medium was added. DC medium was made from Corning RPMI 1640 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 5% heat-inactivated human AB serum plasma (BioIVT, Elevating Science), 100 U ml−1 penicillin and 100 μg ml−1 streptomycin, 2 mM L-glutamine (media supplements from Thermo Fisher Scientific), 80 ng ml−1 GM-CSF and 160 ng ml−1 IL-4 (cytokines from PeproTech). On day 3, fresh DC complete medium supplemented with GM-CSF and IL-4 was added to DCs. DCs were collected on day 6 for co-culture experiments.

Screening T cells for reactivity.

For the ELISpot assay, a human IFN-γ ELISpot kit containing 96-PVDF-backed microplate already pre-coated with monoclonal antibody specific for human IFN-γ (R&D Systems, IL285) was used. The ELISpot assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. On the day before co-culture experiments, autologous CD14− non-adherent cells (source of T cells) were thawed and seeded in appropriately sized tissue culture plates in complete RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 5% heat-inactivated human AB serum plasma (BioIVT, Elevating Science), 100 U ml−1 penicillin and 100 μg ml−1 streptomycin, 2 mM L-glutamine (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and incubated in a 37 °C, 5% CO2 incubator for one overnight (approximately 18 h). Before co-culture, wells from the IFN-γ pre-coated microplate were filled with 300 μl of AIM-V culture medium and incubated for 20 min at room temperature. When cells were ready to be plated, culture media were aspirated from the wells, and, immediately after this, 100 μl of appropriate cells or controls suspended in AIM-V culture medium were added to the wells. In brief, a cell-to-cell ratio of 1:10 stimulated monocyte-derived DCs (mo-DCs) (1 × 104) and autologous T cells (1 × 105) was used. These co-cultures were spiked with the corresponding manufactured predicted neoantigen peptide (GenScript) at a concentration of 1.0 μg ml−1. As a negative control, co-cultures were spiked with vehicle control (for example, 1× PBS). Co-cultures were incubated at 3 °C, 5% CO2 for 24 h. After 24 h of co-culture, the content of each well was aspirated and washed four times with wash buffer provided by the ELISpot kit. Then, 100 μl of diluted detection antibody mixture was added to each well of the microplate and incubated for 2 h at room temperature on a rocking platform. After this, wells were washed four times with wash buffer. Then, 100 μl of diluted Streptavidin-AP concentrate A was added into each well of the microplate and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Wells were washed four times with wash buffer as described before. Next, 100 μl of BCIP/NBT substrate was added into each well. After incubation at room temperature for 1 h and protected from light, BCIP/NBT substrate was decanted, and the wells were rinsed with deionized water. The microplate was completely dried at room temperature for 90 min. The microplate was scanned using an ImmunoSpot ELISpot plate reader (Mabtech Apex 2).

For the ELISpot assays, four patients were excluded for the following reasons. Not enough tissue sample was available for RNA/DNA extraction, and, therefore, no predictions of neoantigens were performed. One of the patients did not complete the clinical study. At some timepoints, there was not sufficient PBMCs to generate autologous mo-DCs and T cells.

Bulk RNA-seq deconvolution

Processed and annotated single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data from 25 patients with MIBC81 were downloaded from GSE169379. PDCD1+CD3+ T cells were identified as T cells with PCDC1 gene expression > 0. BayesPrism (version 2.0)82 was used to deconvolute bulk RNA-seq of bladder tumors using the above scRNA-seq data as reference with default settings. To balance the number of cells and accelerate the computing process, we randomly downsampled 500 cells from each cell type in the scRNA-seq data. Using the raw count gene expression of the scRNA-seq as a reference, we built a Bayesian model that inferred the distribution of cell types that were built from count matrix of bulk RNA-seq. The proportions of PDCD1+CD3+ T cells were deconvoluted from the bulk and compared between pre-treatment and post-treatment in responders and non-responders.

Statistics

Adverse events were continuously monitored through 100 d of discontinuation of experimental drug dosing. Acceptable safety was prospectively defined as a DLT rate of 33% or less, using a Pocock-type stopping boundary with continuous monitoring83. DLT was defined as grade 3 or higher toxicity attributed to the treatment agents, as detailed in Supplementary Information. Pearson’s correlation test was used to determine R2. P values were generated using either Wilcoxon or Pearson tests. Reported P values were two-sided with a significance of 0.05, unless otherwise noted. Normality was not assumed, and non-parametric tests were performed where applicable. RFS and OS were calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method, and 95% CI was included for medians and curves. The formal analysis of treatment response biomarkers (E2F targets, TMB and CPS) were carried out in the per-protocol analysis population, excluding the patient who discontinued treatment before completion. The patient with clinical CR on post-treatment TURBT but did not undergo RC-PLND was considered a responder. The additional exploratory endpoints were analyzed using available samples. ELISA experiments to access the secretion of GM-CSF from urine were performed in triplicate, and the results were reproducible. When enough number of autologous mo-DCs and T cells were obtained from PBMC samples, ELISpot assays were performed in triplicate at the indicated timepoints. R software version 4.2.3 was used to perform a statistical summary and comparative analysis. Specifically, the R gtsummary package version 1.7.1 was used to summarize descriptive statistics and perform Wilcoxon rank-sum and signed-rank tests. The R ggplot2 package version 3.4.2 and the R ggpubr package version 0.6.0 were used to visualize data along with statistical test results.

Extended Data

Extended Data Fig. 1 |. Increases in viral replication is not associated with tumor intrinsic molecular features.

Fold change in GM-CSF, used as a surrogate marker for viral replication, was associated with neither baseline E2F target expression levels (n = 18; Pearson correlation R2 = 0.019; p = 0.58) (a), nor with molecular subtypes (n = 17; p = 0.228) (b).

Extended Data Fig. 2 |. Increase in T lymphocyte infiltration is not associated with baseline tumor/immune features nor treatment response.

Fold changes in infiltrating T lymphocyte levels were not associated with baseline tumor mutational burden (n = 19; CD3+ p = 0.33; CD4+ p = 0.23; CD8+ p = 0.81) (a); pre-treatment CD3+ lymphocytic infiltration (n = 19; CD3+ p = 0.27; CD4+ p = 0.44; CD8+ p = 0.43) (b); baseline tumor molecular subtypes (n = 17; CD3+ p = 0.11; CD4+ p = 0.305; CD8+ p = 0.16) (c); nor with treatment response (n = 19; CD3+ p = 0.97; CD4+ p = 0.9; CD8+ p = 0.5) (d). For dot-plots in a-c, correlation coefficients and P values were calculated using Pearson Correlation. For boxplots in d, boxes represent median (center) and first/third quartile (bottom and top, respectively) values; Tukey whiskers represent the ± 1.5 interquartile range (IQR); individual data points are shown in dots; Two-sided P values were calculated by Wilcoxon’s signed-rank test.

Extended Data Fig. 3 |. Phenotypic changes in T cell markers from pre-to post-treatment.

a, Gene expression levels of PDCD1 (PD-1), TNFRSF4 (b); LAG3 (c); and HAVCR2 (TIM3) (d) on bulk RNA sequencing were not different from pre-to post-treatment in pathologic complete responders vs. non-responders. Two-sided P values were calculated by Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Boxes represent median (center) and first/third quartile (bottom and top, respectively) values; Tukey whiskers represent the ± 1.5 interquartile range (IQR); individual data points are shown in dots colored by CR (blue) or NR (gray).

Extended Data Fig. 4 |. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot (ELISpot) analysis indicates heightened cell-mediated anti-tumor systemic reactivity in patients with pathologic complete response.

a, Representative plots showing fold changes in interferon-γ (IFN-γ) spot-forming units at weeks 2 and/or 6 compared to baseline in clinical responders and b, clinical non-responders. Significance increases were seen at the following timepoints in the following patients: Due to sample limitations, co-culture using neopeptide-primed monocyte-derived DCs with autologous T cells from each patient at each time point was conducted once without replicates.

Extended Data Fig. 5 |. No change was found in the tertiary lymphoid structure (TLS) density from pre-to post-treatment in non-responding patients following treatment.

a, Representative whole slide multiplex immunofluorescence images from a patient who did not respond to treatment, demonstrating lack of increase of TLS in the post-treatment samples. b, TLS density at baseline did not predict pathologic response to combined oncolytic immunotherapy and immune checkpoint inhibitor (n = 16; p = 0.594). Two-sided p values were calculated by Wilcoxon’s signed-rank test. Boxes represent median (center) and first/third quartile (bottom and top, respectively) values; Tukey whiskers represent the ± 1.5 interquartile range (IQR); individual data points are shown in dots colored by the response (responder = blue; non-responder = gray).

Extended Data Fig. 6 |. Features of mature vs. immature tertiary lymphoid structure (TLS).

a, TLS were scored according to morphological features on multiplex immunofluorescence. Immature TLS consisted of general clustering of CD20 + B cells with unclear shape and structure. Mature TLS consisted of large, oval or circular shaped conglomeration of CD20 + B cells. As expected, mature TLS were marked by higher surface areas (***p < 0.001) (b) and cellular density (**p = 0.00652) (c). Two-sided p values were calculated by Wilcoxon’s signed-rank test. Boxes represent median (center) and first/third quartile (bottom and top, respectively) values; Tukey whiskers represent the ± 1.5 interquartile range (IQR).

Extended Data Fig. 7 |. Heightened antibody response post-treatment is directed against tumor cells.