Abstract

Background

Daytime napping is used as a strategy to complement insufficient night-time sleep and improve daytime mental and physical performance. Massage can play a crucial role in promoting relaxation and wellness at various settings including the work place. The purpose of the present study was to investigate the effect of two different types of manual massage sessions on day-time napping in poor sleepers.

Methods

This was a randomized, single blind, placebo-controlled, three arm, interventional clinical trial. Fifteen participants (aged 21.6 ± 1.3 years) participated in three different conditions over one week apart: 1) 30-min Sports massage condition (ACT), 2) 30-min Relaxation massage condition (REL) and 3) control condition with no massage. Brain activity was monitored using a polysomnography EEG system, while vitals and relaxation/stress state were assessed by validated questionnaires and functional tests. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index Score > 5 was used as cut off for distinguishing poor sleeper.

Results

Results showed significant differences between the three conditions, with muscle tone to be reduced by 7.2% after ACT session (p = 0.000) and relaxation scores to be increased by 23.4% after REL session (p = 0.008). In addition, Sleep Latency N1 was improved only after the REL session compared to other two conditions (p = 0.037).

Conclusions

In conclusion, massage can positively impact the quality and quantity of daytime napping and may serve as a complementary intervention to enhance mental well-being, reduce work related stress, improve performance and promote overall a healthier living.

Trial registration

Retrospectively registered (registration date: 16/01/2025; trial registration number at ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT06780072).

Keywords: Sports massage, Relaxation massage, EEG, RSQ, Handgrip

Introduction

In the quest for optimal physical and mental performance and recovery, people are constantly exploring various strategies to enhance their overall well-being [1]. Daytime napping helps mitigate the effects of inadequate nighttime sleep, allowing people to reduce fatigue and potentially improve physical performance [2]. Research has also shown that strategically timed naps can significantly boost athletic performance, improve cognitive function, and reduce daytime fatigue [3, 4].

Short naps lasting between 10 to 60 min are ideal for quickly boosting alertness and cognitive function [3]. Additionally, they can facilitate a complete sleep cycle, including REM sleep, which is crucial for both physical and mental recovery [5]. Massage therapy, recognized for its ability to alleviate muscle soreness, improve circulation, and induce relaxation and it might play a crucial role in facilitating a good night sleep [6].

In athletes a massage therapy serves as both a proactive and reactive measure in optimizing sports and exercise performance, ensuring athletes are physically and mentally prepared for competition while also facilitating their recovery, minimizing the risk of injury [7, 8]. and particularly effective in alleviating pain [9, 10]. Massage therapy significantly contributes to improving night sleep efficiency as well as the duration of sleep onset [11].

From a biochemical point of view, massage promotes the release of serotonin, a hormone that enhances the sense of wellbeing [12]. In addition, serotonin is a biosynthetic precursor of melatonin and an active neurotransmitter, whose levels affect various functions of the body including sleep promotion [13], while can play a significant role in mental health as it regulates mood and emotional well-being [14].

These mechanisms highlight the potential of massage therapy to improve sleep quality. While most studies focus on its effects on nocturnal sleep, there is growing interest in how daytime napping, combined with massage therapies, may enhance cognitive performance, physical recovery, and well-being. Previous research suggests that daytime napping can improve both mental and physical performance and reduce fatigue after both normal and partial sleep deprivation.

Several non-pharmacological strategies have been proposed to facilitate the initiation and improve the quality of daytime naps. Environmental modifications, such as reducing ambient light and noise, maintaining a comfortable room temperature, and establishing consistent nap routines, appear to play a pivotal role in creating optimal conditions for rest [15]. Moreover, relaxation interventions, including the use of calming music combined with essential oil inhalation, have demonstrated positive effects on autonomic nervous system balance, promoting parasympathetic activity conducive to sleep [16]. Similarly, massage therapy has been shown to stimulate parasympathetic activation following physical exertion, supporting recovery and rest [17]. These interventions, by reducing stress and enhancing relaxation, can significantly improve the effectiveness of midday naps, which are increasingly recognized as important for cognitive function, physical recovery and overall well-being.

Nowadays, massage has evolved into various types that are specialized for the treatment of various health problems [8]. The most well know and frequently used types of massage are the “sports massage” and the “relaxation massage”. Sports massage has been proven to enhance athletic performance, as well as help athletes recover after competition [18] while the Deep Relaxation massage is used exclusively for the relaxation and psychological discharge [19]. More specifically, the relaxation-therapeutic massage uses pressure that is deeply relaxing, but not painful, smooth gliding strokes that are both rhythmic and flowing, which increases blood circulation and promotes a general sense of relaxation [8, 20]. Even thought, these 2 very common types of massage have been applied for many years in various settings, it is not clear whether massage affects brain function and state of alertness.

Therefore, the primary aim of the current study was to investigate the effect of two different types of manual massage sessions on day-time napping using objective (EEG—brain activity) and subjective (questionnaires) measurements of relaxation in poor sleepers.

Materials and methods

Trial design

This study is a randomized, single blind, placebo-controlled, three arm, interventional clinical trial to investigate the effect of two different types of manual massage sessions on day-time napping in poor sleepers.

Subjects

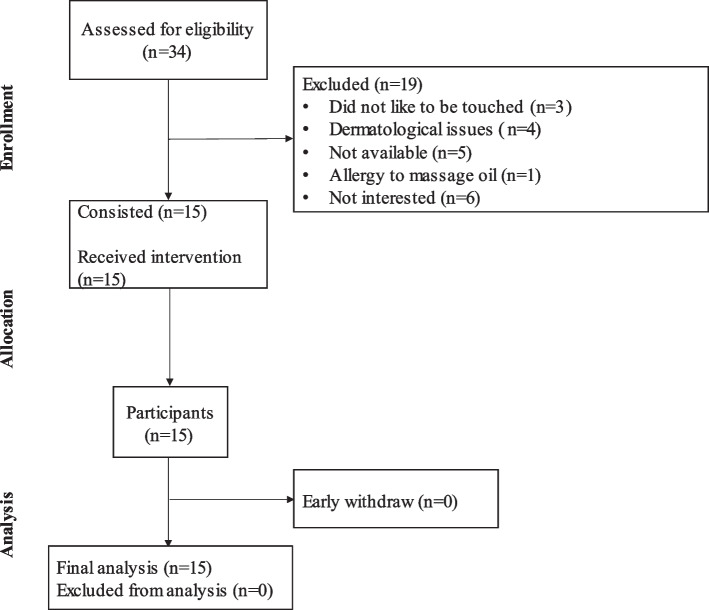

Fifteen (N = 15) participants (age 21.6 ± 1.3 years, 10F/5 M) from the local community were recruited through advertisements at the University of Thessaly students’ union center. The participants assessed for the inclusion and exclusion criteria and voluntarily agreed to participate in the study (Fig. 1). The inclusion criteria required participants to be over 18 years of age, of either sex, and to have a Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) score > 5, indicating some type of sleep disturbances. Exclusion criteria included a history of mental illness, dermatological diseases, allergies to massage oil, epilepsy, or any acute or chronic medical conditions that could limit participation in the study.

Fig. 1.

Consort Diagram. A CONSORT diagram summarizes recruitment, enrollment and dropout rates

Study design

Subjects were randomly assigned by the study director (GKS) into 3 conditions each one week apart using a pseudo-random number generators system. 1) the control condition (CON) where subjects did not receive any intervention, while they were rested for 35 min on a massage bed; 2) the activation condition (ACT) where subjects received an activation (Sports) massage session lasting for 30 min and rested for 5 min without any interference; and 3) the relaxation condition (REL) where subjects received a relaxation massage session lasting for 30 min and rested for 5 min without any interference (Fig. 2). All conditions were separated by one week apart and took place the exact time of the day, while the order of the various conditions was randomly assigned. All massage sessions were delivered by a professional masseur, while the researchers analyzing the data and the participants were blind to the assigned group. All measurements were conducted in the laboratory under controlled conditions, with a constant room temperature of 22°C. The study was approved by the Human Research and Ethics Committee of the University of Thessaly (2094–2/08–02-2023). All Subjects gave their written informed consent prior to study participation.

Fig. 2.

Study Flow Chart. Subjects were assigned in random order to each of the three different sessions over a continuous three-week period. (CON) = control protocol; (REL) = relaxation protocol; (ACT) = activation protocol; (RSQ) = Relaxation State Questionnaire; SF-36 = 36-Item Short Form Survey Instrument; BDI = Beck's Depression Inventory; (EEG) = Polysomnography recordings were taken continuously during the 35-min resting period in each condition

Procedure

All measurements were performed in the Lifestyle Medicine Laboratory, at the Department of Physical Education and Sports Science of Trikala, in Thessaly, Greece between April to September 2024.

Before the initiation of the study, subjects completed a series of questionnaires and measurements related to overall health. Subjects were connected to a portable polysomnographic EEG/EOG system (HST-mit-tablet, SOMNOmedics AG, Randersacker, Germany) for the recording of brain activity. Before and after each condition, subjects completed a relaxation sensation questionnaire (RSQ) for assessing the state of relaxation and performed 3 maximum handgrip attempts for assessing the level of muscle strength. Measurements of vital signs such as resting heart rate and blood pressure also recorded. During the intervention period, participants were given the instructions to stay awake. This was also reinforced by the various manipulations and body maneuvers induced during the massage session from the masseur as well as using various verbal questions such as “are you OK”, “how do you feel”, “do you feel any discomfort” etc. During the “rest phase” participants were free to either sleep or stay awake with the only restriction to stay calm on bed for 5 min.

Data analysis

Data analysis included the final 5 min of EEG called “Rest phase” representing the resting time when participants were left alone without any interaction with the masseur.

Measuring instruments

Body composition

Body composition was assessed using anthropometric measurements including BMI, and bioimpedance (Tanita DC-360 S, Serinth) under standard methodology.

Questionnaires

The following questionnaires were administered using the interview method by experienced researchers.

The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) was used to assess sleep quality and the existence of any sleep abnormalities [21].

The Short Form survey 36-item 36 quality of life questionnaire (SF-36) was used to assess the quality of life [22].

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) questionnaire was used to assess depressive symptoms and signs [23].

The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) was used to assess the level of stress [24].

The Relaxation State Questionnaire (RSQ) was used to assess state of relaxation [25].

Brain activity / arousal assessment

The Home Sleep Test (HST) (www.somnomedics.de), was used to assess brain activity during napping periods. This is a portable sleep monitoring system that enables the recording of various sleep parameters in a natural setting, as the patient’s bedroom. EEG signals were analyzed in 30 s epochs using the SOMNOmedics PSG analysis software (Domino panel ver. 3.0.0.8) and manual editing. The setup for the polysomnography (PSG) involved the use of the Home-Sleep-Test REM + device, which records various sleep parameters, including EEG, EOG, and EMG. EEG measurements were obtained using silver/silver chloride electrode sets, placed in four specific locations that allow for the monitoring of key brain regions associated with sleep cycles. These locations were selected based on the standardized 10/20 system to ensure accurate representation of the frontal, central, and occipital regions, facilitating a comprehensive analysis of the sleep architecture. The use of these electrodes provides high-fidelity recordings essential for evaluating both the depth and quality of sleep stages.

For EEG, the electrode is positioned in the frontopolar region, specifically at Fp1 (left side) and M1, allowing for the monitoring of brain activity. The EOG electrodes are placed near the left and right eyes to record eye movements, which is crucial for analyzing sleep stages, including REM sleep. The system is designed for ease of use: a tablet guides the patient through the sensor application process. Once the test begins, the tablet records data that the sensors transfer via Bluetooth. After the sleep study is completed, all data is automatically transferred from the tablet to a cloud platform for comprehensive analysis, ensuring seamless and accurate evaluation of sleep parameters such as brain activity, eye movements, and muscle tone. EEG analysis was reported as followed: Total Sleep Time (total amount of sleep time scored during the total recording time); Sleep Efficiency (Total sleep time/Time in bed); Sustained Sleep Efficiency (Total sleep time/Time in bed – Sleep latency stage 2); Sleep latency is defined as the time from lights off to the start of the first epoch of any stage of sleep, including stage N1 (or any other stage). If no sleep is observed, the sleep latency is typically recorded as 20 min; Sleep Latency N1 specifically refers to the time from lights out to the onset of the N1 stage of sleep; Sleep Latency N2 (the period of time between time in bed and sleep onset stage 2); REM Latency (the amount of time elapsed between the onset of sleep to the first REM stage) [26].

Handgrip strength assessment

The handgrip test was used for the assessment of maximum isometric strength of the hand and arm muscles (Marsden MG-4800 Hand Dynamometer) and used as a measurement of muscle tone alertness [27]. Reduction of muscle strength after the intervention, was assessed as reduction of muscle tone.

Massage sessions

Activation (Sports) massage

The activation (sports) type of massage [28] was used as one of the massage interventions. This technique was performed on a full body with more attention given to specific leg muscle groups such as the feet, the gastrocnemius, the femoral biceps and quadriceps and in upper body muscle groups such as the triceps, the rhomboid, the deltoid, the trapezius and head areas. Briefly, this type of massage involves a wide range of techniques that include effleurage, palmar sliding, pounding and hacking (Table 1). The total duration of the activation massage was 30 min.

Table 1.

Activation/sports massage protocol (Full body)

| Massage Technique | Rate | Focus Area | Time (duration) in minutes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Effleurage (start) | Slow to Moderate (smooth and continuous strokes) | full body (upper and lower limbs) | 5 |

| 2. Palmar Sliding | Moderate to Fast (smooth, gliding palm movements) | hamstrings, gastrocnemius | 7 |

| 3. Hacking | Moderate to Deep (slow, circular movements with pressure) | trapezius, rhomboids, upper back, shoulders | 6 |

| 4. Pounding | Moderate (closed fist strikes, rhythmic) | upper and lower limbs, gastrocnemius | 7 |

| 5. Effleurage (finish) | Moderate (smooth and continuous strokes) | full body (upper and lower limbs) | 5 |

Relaxation massage

The Relaxation type of massage [29] was used as the second type of intervention in this study. This technique is designed to promote deep relaxation, reduce stress and enhance overall well-being. It is characterized by the use of four primary techniques performed on the full body, including the palms and feet. Specifically, these techniques consist of effleurage (long, smooth, gliding strokes), petrissage (light pressure, rhythmic movements) and vibration gentle shaking movements (Table 2). In addition to these, the technique also incorporates rhythmic movements and deep light pressure to enhance relaxation and alleviate tension. The total duration of the Relaxation massage was 30 min.

Table 2.

Relaxation massage protocol (Full body)

| Massage Technique | Rate | Focus Area | Time (duration) in minutes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Effleurage (start) | Slow to Moderate (smooth and continuous strokes) | full body (upper and lower limbs) | 5 |

| 2. Petrissage | Gentle (light pressure, rhythmic movements) | hamstrings, calves, back, shoulders | 8 |

| 3. Light Vibration | Slow (gentle shaking movements) | upper back and lower back | 5 |

| 4. Light Kneading | Slow and Rhythmic | neck, arms, upper back and lower back, calves | 7 |

| 5. Effleurage (finish) | Slow (smooth and relaxing strokes) | full body (upper and lower limbs) | 5 |

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 29 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, U.S.A.) An independent samples T-test was used to examine differences in baseline characteristics and questionnaires between male and female subjects. A General Linear Model (GLM) Repeated Measures ANOVA was used to assess changes in all parameters among the 3 different scenarios. A Bonferroni post-hoc test was performed to assess individual differences. To assess normality, the Shapiro–Wilk test was used alongside graphical representations, including the Normal Q-Q plot, Detrended Normal Q-Q plot, and Box Plot. The significance level was set at 5%. Beyond significance testing (p-value), effect size was also considered to evaluate the magnitude of the effect. An effect size of 0.6 was selected based on previous studies in similar interventions where moderate-to-large effects were expected on sleep-related outcomes.

Power analysis

Sample size calculations were conducted using G*Power 3.1. The post-hoc “GLM”—Repeated measures, within factors” method was used to calculate the power analysis. The resulting minimum required sample size to achieve 85% power was 14 for 2-sided group-1 and group-2 errors 5% [(Effect size 0.60, Critical F 4.10, Ndf 2, Ddf 10, Power (1-β err pob) = 0.86 (86% power)].

Trial registration

The trial was registered under the title “Impact of Massage on Daytime Napping (TakeAnap)” with the full protocol accessible through ClinicalTrials.gov website. Trial registration number: NCT06780072.

Results

Subject characteristics are presented in Table 3. No statistically significant differences were found between male and female participants.

Table 3.

Baseline characteristics

| Parameters | Values |

|---|---|

| N | 15 |

| Sex | 5 M/10F |

| Age (years) | 21.6 ± 1.3 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.9 ± 2.7 |

| Fat (%) | 17.3 ± 7.5 |

| Muscle Mass (kg) | 51.8 ± 11.6 |

| SF-36 Total Score | 72.6 ± 14.4 |

| SF-36 Physical Summary | 69.9 ± 18.9 |

| SF-36 Mental Summary | 67.0 ± 14.7 |

| Beck Depression Inventory | 13.1 ± 7.8 |

| Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index | 13.0 ± 4.8 |

| Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) | 19.7 ± 3.0 |

Data are presented as Mean ± SD. An independent t-test was used to assess differences between males and females. Significance level P < 0.05; ΒΜΙ: Body Mass Index

Furthermore, Table 4 presents the mean PSQI component scores.

Table 4.

PSQI component scores

| Parameters | Values (Mean ± SD) |

|---|---|

| Subjective Sleep Quality | 1.19 ± 0.8 |

| Sleep Latency (min.) | 0.14 ± 0.6 |

| Sleep Duration (hours) | 7.26 ± 1.1 |

| Habitual Sleep Efficiency (%) | 2.28 ± 0.9 |

| Sleep Disturbances | 2.14 ± 0.8 |

| Use of Sleep Medication | 0.57 ± 0.8 |

| Daytime Dysfunction | 1.57 ± 1.3 |

Data are presented as Mean ± SD. The values for each subcategory of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index range from 0 to 3, with 0 representing the best possible score and 3 indicating the most problematic outcome

Pre and Post-intervention assessments among the 3 different conditions are shown in Table 5. Significant differences within groups were found in handgrip strength (muscle tone) before and after all conditions. Statistically significant effects were observed in RSQ among the three sessions [F(5,70) = 5.855, p=0.001], with RSQ increasing significantly after the REL massage session by 23.4% (p=0.002), indicating a robust improvement in relaxation.

Table 5.

Pre and post intervention assessment among the 3 different conditions

| Variables | Pre (Mean ± SD) (95% CI) | Post (Mean ± SD) (95% CI) | P Value* (Effect size-d) | Pre (Mean ± SD) (95% CI) | Post (Mean ± SD) (95% CI) | P Value* (Effect size-d) | Pre (Mean ± SD) (95% CI) | Post (Mean ± SD) (95% CI) | P Value* (Effect size-d) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Δ-change%) | (Δ-change%) | (Δ-change%) | |||||||

| N | 15 | 15 | - | 15 | 15 | - | 15 | 15 | - |

| RSQ |

34.8 ± 5.7 (31.9 to 37.7) |

37.4 ± 4.8 (35 to 39.8) |

0.417* (0.493) (14.3% ± 5.0) |

33.9 ± 5.2 (31.3 to 36.5) |

37.5 ± 5.2 (34.9 to 40.1) |

0.683* (0.692) (16.8% ± 5.4) |

32.1 ± 5.1 (29.5 to 34.7) |

39.6 ± 4.9*** (37.1 to 42.1) |

0.168* (1.499) (23.4% ± 5.0)** |

| Systolic Pressure (mmHg) |

112.5 ± 10.1 (107 to 118) |

109.3 ± 10.9 (104 to 115) |

0.030 (0.304) (-3.8% ± 1.0) |

114.1 ± 9.0 (110 to 119) |

108.6 ± 13.2 (102 to 115) |

0.012 (0.469) (-1.2% ± 1.0) |

112.6 ± 9.2 (108 to 117) |

110.0 ± 9.4 (105 to 115) |

0.568 (0.279) (-0.1% ± 0.9) |

| Diastolic Pressure (mmHg) |

68.1 ± 6.5 (64.8 to 71.4) |

70.8 ± 7.9 (66.8 to 74.8) |

0.184 (0.373) (5.1% ± 0.7) |

71.1 ± 6.5 (67.8 to 74.4) |

67.4 ± 6.9 (63.9 to 70.9) |

0.995 (0.551) (-1.2% ± 0.6) |

68.0 ± 5.4 (65.3 to 70.7) |

69.0 ± 5.4 (66.3 to 71.7) |

0.316 (0.185) (2% ± 0.5) |

| Heart Rate (Bits/min) |

78.6 ± 15.2 (70.9 to 86.3) |

66.8 ± 12.9 (60.3 to 73.3) |

0.001 (0.837) (-12.1% ± 15.4) |

81.9 ± 12.7 (75.5 to 88.3) |

73.8 ± 10.4 (68.5 to 79.1) |

0.082 (0.697) (-12.2% ± 12.7) |

75.4 ± 12.5 (69.1 to 81.7) |

73.7 ± 15.6 (65.8 to 81.6) |

0.093 (0.120) (-6.6% ± 13.2) |

| Handgrip Strength (Kg) |

23.3 ± 2.1 (22.2 to 24.4) |

22.8 ± 3.2 (21.2 to 24.4) |

0.002 (0.184) (-4% ± 2.9) |

23.5 ± 2.4 (22.3 to 24.7) |

22.2 ± 3.5 (20.4 to 24) |

0.000 (0.433) (-7.2% ± 3.2) |

23.2 ± 2.4 (22 to 24.4) |

22.0 ± 3.4 (20.3 to 23.7) |

0.006 (0.407) (-4.8% ± 3.3) |

Data are presented as Mean ± SD. Significance level P < 0.05

RSQ Relaxation Scales Questionnaire, CON control, ACT activation massage, REL relaxation massage, Δ-Change % difference compared to Pre values, Paired t test Means of pre-post measurements between (CON-ACT-REL) protocols

*Differences between the Δ-changes were assessed using a GLM Repeated Measures test; RSQ: CON vs ACT vs REL, P = 0.010

**Differences between the %Δ-changes were assessed using an ANOVA test; RSQ: CON vs REL, P = 0.008 and ACT vs REL, P = 0.038 (Bonferroni PostHoc Test)

***Differences between protocols (CON-ACT-REL) were assessed using a GLM Repeated Measures test; RSQ: [F(5,70) = 5.855, P = 0.001], and particularly for RSQ: Pre-REL vs Post-REL, P = 0.002 (Bonferroni Post Hoc Test)

Specifically, handgrip strength decreased after both ACT and REL massage sessions, with percentage changes of -7.2% ± 3.2 (p=0.000) and -4.8% ± 3.3 (p=0.006), respectively, showing a clear reduction in muscle tone. Statistically significant differences were also found in the Δ-change of the aforementioned values. RSQ increased most notably after the REL massage (%Δ-change: 34.2 ± 5.0, p=0.038), while systolic pressure decreased after the ACT massage session (%Δ-change: -1.2 ± 1.0, p=0.012). In addition, no statistically significant difference was found in resting heart rate across all sessions (p>0.05).

In Table 6, brain activity parameters are presented. A statistically significant effect was found in Sleep Latency N1 among the three sessions [F (2, 32) = 6.193, p=0.037], indicating that the Relaxation massage session had a greater impact in reducing arousal and facilitating sleep onset. The p-value for Sleep Latency N1 improvement was statistically significant and the effect size was substantial (0.608), suggesting that Relaxation massage may have a meaningful impact. Although, this finding should be interpeted with caution and further validated.

Table 6.

Brain activity pre and post intervention assessment among the 3 different conditions (Rest Phase—5 min)

| Variables | CON (Mean ± SD) (95% CI) | ACT (Mean ± SD) (95% CI) | REL (Mean ± SD) (95% CI) | P Value* (Effect size-E) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Sleep Time (min.) |

2.0 ± 2.1 (0.86 to 3.14) |

2.6 ± 2.2 (1.4 to 3.8) |

1.3 ± 1.9 (0.27 to 2.33) |

0.067 (0.207) |

| Sleep Efficiency (%) |

25.1 ± 32.4 (7.5 to 42.7) |

54.0 ± 44.1 (30 to 78) |

33.6 ± 40.4 (11.6 to 55.6) |

0.125 (0.149) |

| Sustained Sleep Efficiency (%) |

41.3 ± 38.8 (20.2 to 62.4) |

62.0 ± 42.9 (38.7 to 85.3) |

33.8 ± 40.3 (11.9 to 55.7) |

0.117 (0.164) |

| Sleep Latency N1 (min) |

2.3 ± 2.3 (1.05 to 3.55) |

2.9 ± 1.7* (1.98 to 3.82) |

0.04 ± 0.08 (-0.0301 to 0.11) |

0.037 (0.608) |

| Sleep Latency N2 (min) |

1.0 ± 1.6 (0.13 to 1.87) |

0.9 ± 1.3 (0.193 to 1.61) |

0.0 ± 0.0 (0 to 0) |

0.410 (0.182) |

Data are presented as Mean ± SD. Significance level P < 0.05; *a trend: ACT vs REL, P = 0.062

No side effects or signs of discomfort were reported during the duration or after the study.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the effects of two distinct and fashionable types of massage on daytime brain activity among poor sleepers, employing both objective and subjective measurements. A group of poor sleepers was selected due to their consistently more pronounced and stable sleep disturbances, such as insomnia, which are typically characterized by more stable and pronounced sleep issues compared to other sleep disorders.These individuals often present with distinct sleep patterns and characteristics that differ significantly from those diagnosed with clinical insomnia [30]. The primary outcome of this investigation reveals that, when subjective assessments of relaxation were employed, the Relaxation massage demonstrated a significantly greater effect, resulting in a 23.4% increase in relaxation (RSQ) score (Table 5). As expected, objective EEG recordings showed a significant increase in Sleep Latency N1 following the Relaxation massage (REL) condition, indicating a reduction in pre-sleep arousal. Specifically, Sleep Latency N1 increased by 0.6 minutes (approximately 26%), from 2.3 ± 2.3 to 2.9 ± 1.7 minutes consistent with the calming and parasympathetic activation effects typically associated with relaxation massage (Table 6).

Specifically, concerning objective variables, individuals undergoing Sports/Activation massage exhibited a significant decrease in handgrip strength (-7.2%, p = 0.000), indicating a reduction in muscle tone. This observation was concurrent with a decline in systolic blood pressure, suggesting the promotion of muscle relaxation in these individuals (Table 5). It appears that a 30-min full-body sports massage provides benefits in people experiencing poor sleep. In our study, sports massage appears to have a more pronounced effect on reducing arousal levels due to its greater ability to activate the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) compared to relaxation massage. This activation of the PNS promotes relaxation and recovery while simultaneously diminishing the hyperactivity of the sympathetic nervous system (SNS), which is associated with stress and muscle soreness [17, 31].

Through more intense and targeted techniques, sports massage may effectively reduce muscle tension, aiding athletes in achieving quicker recovery and improved the sense of relaxation [32]. This could explain why poor sleepers, who may experience stress and physical strain, benefit from this technique. In our study, participants scored an average of 19.7 ± 3.0 on the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS), indicating a moderate level of stress and verified by the SF36 physical component summary (Table 3). According to the PSS scale, scores ≥ 27 indicate elevated stress levels, which suggests that our participants experienced moderate stress during the study period [33]. This aligns with the potential benefits of sports massage in alleviating stress-related physical strain.

It seems that sports massage could have significant implications for health and performance, influencing sleep therapy, rehabilitation and help reduce anxiety levels and improve the quality of life [34].

Indeed, in the study by Field et al., was found that massage therapy can improve the mental and physical health of depressed pregnant women by increasing levels of dopamine and serotonin while reducing levels of cortisol and norepinephrine, which is associated with lower anxiety, better sleep, and fewer depressive symptoms. High levels of cortisol, often referred to as the "stress hormone," can lead to negative health outcomes, including increased anxiety and disrupted sleep patterns; thus, the ability of massage to lower cortisol levels is particularly beneficial for stress management [35].

Additionally, research by Bazzichi et al. suggests that massage therapy, with strokes directed from the lower extremities upward towards the cranial region, may serve as an effective tool for reducing muscle stiffness and enhancing autonomic nervous system function. This is characterized by a reduction in sympathetic tone and an increase in parasympathetic tone [36]. In a study utilizing EEG, massage therapy performed on an automatic spine bed with a roller massaging the muscles along the spine, moving up and down from the cervical to the coccygeal vertebrae, particularly when combined with infrared heating, significantly improved physical functioning, increased parasympathetic response, and reduced psychological stress and anxiety levels. The novelty of using EEG in this study provides more accurate and immediate insights into the effects of massage on brain arousal, highlighting the relationship between massage and sleep quality [37]. A study by Ventura et al. demonstrated that a parent-led massage routine during the first four months of an infant's life resulted in detectable changes in the electroencephalogram (EEG) during sleep, including increased spectral power in sleep spindles, elevated EEG amplitude, and reduced interhemispheric coherence [38].

Furthermore, it seems that a full-body sports massage can enhance blood circulation to the muscles, aiding in the delivery of oxygen and nutrients while removing metabolic waste [39]. Additionally, this enhanced blood flow can contribute to the recovery process by reducing muscle soreness and fatigue [40]. Through more intense and targeted techniques, sports massage may effectively reduce muscle tension, aiding athletes in achieving quicker recovery and improved the sense of relaxation [41]. This could explain why poor sleepers, who are likely exposed to higher levels of stress and physical strain, experience greater relief through this technique. It seems, the duration of massage appears to play a crucial role in muscle relaxation and neuromuscular response, with longer sessions potentially causing excessive relaxation, an effect that may not occur with shorter protocols [42]. This phenomenon could have significant implications for muscle performance and functionality, making the appropriate selection of massage duration essential depending on the desired outcome. Furthermore, sports massage exerts its effects through mechanisms that enhance blood circulation and activate the lymphatic system, aiding in the transport of nutrients and the removal of metabolic waste [43]. Additionally, sports massage impairs postexercise muscle blood flow and "lactic acid" removal [44]. Moreover, increased blood flow and the production of hyaluronic acid, which reduces friction between muscle structures, facilitate muscle relaxation and recovery, while the improvement in range of motion (ROM) provides additional functional benefits [45] and rehabilitation [7]. Therefore, both the duration and technique of massage are key factors in determining its overall impact on muscle relaxation and recovery.

Another study revealed the immediate neurophysiological effects of different types of massage on healthy adults, indicating that Swedish/Relaxation massage, using gentle strokes and gliding manoeuvres (i.e., effleurage, petrissage, longitudinal and transverse foulage, the latter two involving thumb sliding over tendons, ligaments, or muscles to separate these tissues), activates specific brain regions associated with consciousness during cognitive tasks, influencing neural activity and the management of mood disorders [46]. Similarly, in another study by Shen et al., it was found that a single acute Swedish massage applied to the plantar surface of the right foot increased resting state activation in two brain regions (sACC and RSC/PCC), which are important nodes in the default mode network and are critical for self-awareness and arousal [47].

Contrary to our original hypothesis that relaxation massage would have the largest effect in reducing arousal levels, only the Sports/Activation massage, lasting 30 min, demonstrated a significant beneficial effect on relaxation by increasing Sleep Latency N1. Analysis revealed a positive effect on Sleep Latency N1 following the Sports/Activation massage, indicating that participants were able to fall asleep faster after this type of massage. This implies that participants experienced a more rapid entry into the N1 sleep stage, characterized by light sleep and marking the initial phase of the sleep cycle [48]. Faster entry into the N1 sleep stage offers numerous benefits, particularly for athletes [49]. This efficient transition results in less time spent awake attempting to fall asleep, leading to higher sleep efficiency and increased total sleep duration. Poor sleepers often have difficulty falling asleep, wake up multiple times during the night, or rise early in the morning without feeling rested. Interestingly, those who report high or low levels of distress regarding their sleep issues tend to have similar severity and duration of the problem [50].

In contrast, individuals with clinical insomnia experience persistent sleep disturbances occurring at least three times per week. These disturbances are frequently associated with psychological issues such as anxiety and depression, along with a heightened state of alertness during the day struggling most of the time to both initiate and/or maintain sleep at night [51].

It is known that enhanced sleep efficiency and napping positively impacts cognitive functions such as memory attention and decision making, all of which are vital for any type of performance [52, 53]. Improved sleep quality also contributes to higher energy levels, reduced daytime fatigue, and better mood and mental health, collectively enhancing the person’s overall well-being and performance [54, 55].

In the present study, we must acknowledge both some significant strengths and unforeseen limitations. One of the primary strengths of our study is the combination of both objective and subjective type of methodology used to assess relaxation and brain activity. In addition, a blinding process of analysing the data was applied, since all researchers involved in the analysis were unaware of the type of session. Finally, the use of a real time EEG monitoring system provided an objective measurement of the brain activity that is valuable for understanding the immediate effects of massage on the brain.

One limitation that requires acknowledgment is the disparity in sample size between female and male subjects. This imbalance could have resulted in minor errors in measurement data or inconsistencies in our results. Another limitation of our study is that the EEG system used was part of a full-night EEG-EOG polysomnography system with only 4 EEG channels, rather than the 10–24 channels typically used in neurological EEG systems. This limitation may have impacted the ability to capture finer details of sleep architecture. In addition, poor sleepers were separated by good sleepers using a validated questionnaire and not the gold standard methodology which is the full night polysomnography. Finally, another weakness that needs to be acknowledged is that the day of the massage session was not controlled for the menstrual cycle of the female participants. This could have an impact of relaxation and arousal levels.

Future research should explore the long-term effects of repeated massage sessions on various populations, with a particular focus on athletes and individuals with sleep disorders.

Conclusions

The Relaxation type of massage improves overall feelings of relaxation; however, the Sports/Activation massage seems to reduce brain arousal, leading to a faster and longer napping period in people with poor sleep quality. Further research is necessary to ascertain the mechanism by which massage can alter brain activity and whether these techniques can exert the same effect on individuals with insomnia or stress and anxiety disorders over the long term.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all participants who volunteered for the purposes of this study.

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization, I.N. and G.K.S; Methodology, G.K.S., C.K.; formal analysis, I.N. and G.K.S; investigation, I.N., G.K.S, C.K., F.B., N.M., A.A., C.-D.G., F.P., E.D., E.L.; writing-original draft preparation, I.N. and G.K.S., C.K., F.B., N.M., A.A., C.-D.G., F.P., E.D., E.L.; writing-review and editing, I.N., G.K.S., C.K., C.-D.G, E.D., E.L.; visualization, I.N., G.K.S., C.K.; supervision, G.K.S., C.K.; project administration, G.K.S., C.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data availability

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Declarations

Ethics and consent to participate

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki/). Ethical approval was obtained from the Human Research and Ethics Committee of the University of Thessaly (Approval No. 2094–2/08–02-2023). All participants provided written informed consent prior to their inclusion in the study.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Mujika I, Halson S, Burke LM, Balagué G, Farrow D. An integrated, multifactorial approach to periodization for optimal performance in individual and team sports,” May 01, 2018, Human Kinetics Publishers Inc. 10.1123/ijspp.2018-0093. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Boukhris O, et al. The impact of daytime napping following normal night-time sleep on physical performance: a systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression. Springer Sci Business Media Deutschland GmbH. 2024;54(2):323–45. 10.1007/s40279-023-01920-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dutheil F, et al. Effects of a short daytime nap on the cognitive performance: a systematic review and meta-analysis. MDPI. 2021;18(19):10212. 10.3390/ijerph181910212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simpson NS, Gibbs EL, Matheson GO. Optimizing sleep to maximize performance: implications and recommendations for elite athletes. Blackwell Munksgaard. 2017;27(3):266–74. 10.1111/sms.12703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.M Lastella, SL Halson, JA Vitale, AR Memon, GE Vincent. To nap or not to nap? A systematic review evaluating napping behavior in athletes and the impact on various measures of athletic performance. Dove Medical Press Ltd. 2021. 10.2147/NSS.S315556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Guo J, et al. Massage alleviates delayed onset muscle soreness after strenuous exercise: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers Media SA. 2017;27:747. 10.3389/fphys.2017.00747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.J Brummitt. Literature review the role of massage in sports performance and rehabilitation : current evidence and future correspondence. Phys Ther. 20083(1):7–21, [Online]. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2953308/pdf/najspt-03-007.pdf. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Weerapong P, Hume PA, Kolt GS. The mechanisms of massage and effects on performance, muscle recovery and injury prevention. Sports Med. 2005;35(3):235–56. 10.2165/00007256-200535030-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Angelopoulos P, et al. Cold-water immersion and sports massage can improve pain sensation but not functionality in athletes with delayed onset muscle soreness. Healthcare (Switzerland). 2022;10:12. 10.3390/healthcare10122449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mak S, et al. Use of massage therapy for pain, 2018–2023: a systematic review. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(7):e2422259. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.22259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kudo Y, Sasaki M. Effect of a hand massage with a warm hand bath on sleep and relaxation in elderly women with disturbance of sleep: a crossover trial”. Japan J Nurs Sci. 2020;17:3. 10.1111/jjns.12327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carley DW, Farabi SS. Physiology of sleep. Diab Spectrum. 2016;29(1):5–9. 10.2337/diaspect.29.1.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Erland LAE, Saxena PK. Melatonin natural health products and supplements: presence of serotonin and significant variability of melatonin content. J Clin Sleep Med. 2017;13(2):275–81. 10.5664/jcsm.6462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meneses A, Liy-Salmeron G. Serotonin and emotion, learning and memory. Rev Neurosci. 2012;23(5–6):543–53. 10.1515/revneuro-2012-0060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang H, Chen Y, Wang Z. Comparative efficacy of non-pharmacological interventions on sleep quality in old adults: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Clin Nurs. 2024;33(5):1948–57. 10.1111/jocn.17086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peng S-M, Koo M, Yu Z-R. Effects of music and essential oil inhalation on cardiac autonomic balance in healthy individuals. J Alternat Complement Med. 2009;15(1):53–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Isar NE, Halim MH, Ong ML. Acute massage stimulates parasympathetic activation after a single exhaustive muscle contraction exercise. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2022;30:105–11. 10.1016/j.jbmt.2022.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dakić M, Toskić L, Ilić V, Đurić S, Dopsaj M, Šimenko J. The effects of massage therapy on sport and exercise performance: a systematic review. Sports. 2023;11(6):110. 10.3390/sports11060110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.M Romanowski, J Romanowska, M Grześkowiak. A comparison of the effects of deep tissue massage and therapeutic massage on chronic low back pain. In Studies in Health Technology and Informatics, IOS Press, 2012, pp. 411–414. 10.3233/978-1-61499-067-3-411. [PubMed]

- 20.Gasibat Q, Suwehli W. Determining the benefits of massage mechanisms: a review of literature. Article J Rehab Sci. 2017;2(3):58–67. 10.11648/j.rs.20170203.12. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ, Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28:193–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.JE Ware. SF-36 health survey update. Dec. 15, 2000. 10.1097/00007632-200012150-00008.

- 23.Beck AT, Guth D, Steer RA, Ball R. Screening for major depression disorders in medical inpatients with the beck depression inventory for primary care. Behav Res Ther. 1997;35(8):785–91. 10.1016/S0005-7967(97)00025-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.E Yılmaz Koğar, H Koğar. A systematic review and meta-analytic confirmatory factor analysis of the perceived stress scale (PSS-10 and PSS-14),” Feb. 01, 2024, John Wiley and Sons Ltd. 10.1002/smi.3285. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Steghaus S, Poth CH. Assessing momentary relaxation using the Relaxation State Questionnaire (RSQ). Sci Rep. 2022;12:1. 10.1038/s41598-022-20524-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berry RB, Brooks R, Gamaldo CE, Harding SM, Marcus C, Vaughn BV. The AASM manual for the scoring of sleep and associated events”, Rules, Terminology and Technical Specifications, Darien, Illinois, American Academy of. Sleep Med. 2012;176:7. [Google Scholar]

- 27.SC Higgins, J Adams, R Hughes. Measuring hand grip strength in rheumatoid arthritis,” May 01, 2018, Springer Verlag. 10.1007/s00296-018-4024-2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Benjamin PJ, Lamp SP. Understanding sports massage. Human Kinet. 2005. 10.5040/9781718209657. [Google Scholar]

- 29.EA Holey, EM Cook. Evidence-based Therapeutic Massage: A Practical Guide for Therapists. Churchill Livingstone, 2003.

- 30.Bonnet MH, Burton GG, Arand DL. Physiological and medical findings in insomnia: implications for diagnosis andcare. Sleep Med Rev. 2014;18(2):111–22. 10.1016/j.smrv.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davis HL, Alabed S, Chico TJA. Effect of sports massage on performance and recovery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. 2020;6(1):e000614. 10.1136/bmjsem-2019-000614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boguszewski D, Szkoda S, Adamczyk JG, Białoszewski D. Sports mass age therapy on the reduction of delayed onset muscle soreness of the quadriceps femoris. Human Movement. 2014;15(4):234–7. 10.1515/humo-2015-0017. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khafagy G, El Sayed I, Abbas S, Soliman S. Perceived stress scale among adolescents with polycystic ovary syndrome. Int J Womens Health. 2020;12:1253–8. 10.2147/IJWH.S279245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Naderi A, Rezvani MH, Aminian-Far A, Hamood-Ahvazi S. Can a six-week Swedish massage reduce mood disorders and enhance the quality of life in individuals with Multiple Sclerosis? A randomized control clinical trial. Explore. 2024;20(5):103032. 10.1016/j.explore.2024.103032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Field T, Diego MA, Hernandez-Reif M, Schanberg S, Kuhn C. Massage therapy effects on depressed pregnant women. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol. 2004;25(2):115–22. 10.1080/01674820412331282231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bazzichi L, et al. A combination therapy of massage and stretching increases parasympathetic nervous activity and improves joint mobility in patients affected by fibromyalgia. Health N Hav. 2010;02(08):919–26. 10.4236/health.2010.28136. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim DW, Lee DW, Schreiber J, Im CH, Kim H. Integrative evaluation of automated massage combined with thermotherapy: physical, physiological, and psychological viewpoints”. Biomed Res Int. 2016;2016:2826905. 10.1155/2016/2826905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ventura S, et al. Parent-led massage and sleep EEG for term-born infants: a randomized controlled parallel-group study. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2023;65(10):1395–407. 10.1111/dmcn.15565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ningsih YF, Kurniasih F, Puspitaningrum DA, Mahmudi K, Wardoyo AA. The effect of sport massage and Thai massage to lactic acid and pulse decreased. Int J Adv Eng Res Sci. 2017;4(12):237335. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Best TM, Hunter R, Wilcox A, Haq F. Effectiveness of sports massage for recovery of skeletal muscle from strenuous exercise. Clin J Sport Med. 2008;18(5):446–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boguszewski D, Szkoda S, Adamczyk JG, Białoszewski D. Sports mass age therapy on the reduction of delayed onset muscle soreness of the quadriceps femoris. Human Movement. 2014;15(4):234–7. 10.1515/humo-2015-0017. [Google Scholar]

- 42.W Poppendieck, M Wegmann, A Ferrauti, M Kellmann, M Pfeiffer, T Meyer. Massage and Performance Recovery: A Meta-Analytical Review. Feb. 01, 2016, Springer International Publishing. 10.1007/s40279-015-0420-x. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Bakar Y, Coknaz H, Karli Ü, Semsek Ö, Serin E, Pala ÖO. Effect of manual lymph drainage on removal of blood lactate after submaximal exercise. J Phys Ther Sci. 2015;27(11):3387–91. 10.1589/jpts.27.3387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wiltshire EV, Poitras V, Pak M, Hong T, Rayner J, Tschakovsky ME. Massage impairs postexercise muscle blood flow and ‘lactic Acid’ removal. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42(6):1062–71. 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181c9214f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McKechnie GJB, Young WB, Behm DG. Acute effects of two massage techniques on ankle joint flexibility and power of the plantar flexors. J Sports Sci Med. 2007;6(4):498–504. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sliz D, Smith A, Wiebking C, Northoff G, Hayley S. Neural correlates of a single-session massage treatment. Brain Imaging Behav. 2012;6(1):77–87. 10.1007/s11682-011-9146-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shen CC, Tseng YH, Shen MCS, Lin HH. Effects of sports massage on the physiological and mental health of college students participating in a 7-week intermittent exercises program. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:9. 10.3390/ijerph18095013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Putilov AA, Kovalzon VM, Dorokhov VB. A relay model of human sleep stages. Eur Phys J. 2023. 10.1140/epjs/s11734-023-01059-1. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kölling S, Duffield R, Erlacher D, Venter R, Halson SL. Sleep-related issues for recovery and performance in athletes. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2019;14(2):144–8. 10.1123/ijspp.2017-0746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fichten CS, Creti L, Amsel R, Brender W, Weinstein N, Libman E. Poor sleepers who do not complain of insomnia: Myths and realities about psychological and lifestyle characteristics of older good and poor sleepers. J Behav Med. 1995;18(2):189–223. 10.1007/BF01857869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Roth T. Insomnia: definition, prevalence, etiology, and consequences. J Clin Sleep Med. 2007;3(5 SUPPL.):3–6. 10.5664/jcsm.26929. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Diekelmann S. Sleep for cognitive enhancement. Front Syst Neurosci. 2014;8:1. 10.3389/fnsys.2014.00046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.B Faraut, T Andrillon, MF Vecchierini, D Leger. Napping: A public health issue. From epidemiological to laboratory studies,” Oct. 01, 2017, W.B. Saunders Ltd. 10.1016/j.smrv.2016.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.McCarthy S. Weekly patterns, diet quality and energy balance. Physiol Behav. 2014;134:55–9. 10.1016/j.physbeh.2014.02.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pastier N, Jansen E, Boolani A. Sleep quality in relation to trait energy and fatigue: an exploratory study of healthy young adults. Sleep Sci. 2022;15:375–9. 10.5935/1984-0063.20210002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.