Abstract

Abuse of amphetamine-based stimulants is a primary public health concern. Recent studies have underscored a troubling escalation in the inappropriate use of prescription amphetamine-based stimulants. However, the neurophysiological mechanisms underlying the impact of acute methamphetamine exposure (AME) on sleep homeostasis remain to be explored. This study employed non-human primates and electroencephalogram (EEG) sleep staging to evaluate the influence of AME on neural oscillations. The primary focus was on alterations in spindles, delta oscillations, and slow oscillations (SOs) and their interactions as conduits through which AME influences sleep stability. AME predominantly diminishes sleep-spindle waves in the non-rapid eye movement 2 (NREM2) stage, and impacts SOs and delta waves differentially. Furthermore, the competitive relationships between SO/delta waves nesting with sleep spindles were selectively strengthened by methamphetamine. Complexity analysis also revealed that the SO-nested spindles had lost their ability to maintain sleep depth and stability. In summary, this finding could be one of the intrinsic electrophysiological mechanisms by which AME disrupted sleep homeostasis.

Keywords: Amphetamine, Sleep stage, Slow oscillation (SO), Delta oscillation, Addiction, Electroencephalogram (EEG)

Abstract

苯丙胺类兴奋剂的滥用是全球重要的公共健康风险之一。近期研究指出,处方安非他命类药物的滥用呈现显著上升趋势。然而,急性甲基苯丙胺暴露(AME)影响睡眠稳态的神经生理机制仍有待探索。本研究采用非人灵长类动物(恒河猴)为模型,利用脑电图(EEG)睡眠分期的方法评估AME对神经振荡的调控作用,并重点研究AME对睡眠纺锤波、delta波和慢波(SO)的差异性影响,及其在睡眠稳定性调控中的相互作用机制。AME显著抑制非快速眼动2期(NREM2)的睡眠纺锤波,并对SO和delta波具有差异性调控作用。此外,甲基苯丙胺特异性增强了SO和delta波与睡眠纺锤波的嵌套关系;复杂度特征分析发现,SO嵌套的纺锤波维持睡眠深度和稳定性的生理功能也出现显著损伤。上述结果在神经振荡网络层面上阐述了AME导致睡眠稳态破坏的内在电生理机制。

Keywords: 安非他命, 睡眠分期, 慢波振荡, Delta振荡, 脑电图

1. Introduction

Despite the efficacy of amphetamine-based stimulants in treating conditions such as narcolepsy and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, amphetamine abuse has emerged as a prominent substance use disorder, affecting over 35 million people globally and leading to severe mental disorders, violence, and disability (Fazel et al., 2009; Whiteford et al., 2013; Sun et al., 2014; Baingana et al., 2015; McElroy 2017; Bassetti et al., 2019; Posner et al., 2020). Individuals affected by the disorder may engage in “self-medication” with methamphetamine and related substances to cope with stress or negative emotions, or to enhance performance in daily functioning (Winslow et al., 2007; van Emmerik-van Oortmerssen et al., 2012). Recent statistical data indicate a rapid rise in the misuse of prescription amphetamine-based stimulants, resulting in escalating cases of acute adaptation disorders associated with excessive use (Cruickshank and Dyer, 2009; Vivolo-Kantor et al., 2020; Berro et al., 2022).

Sleep disorders constitute one of the most clinically significant health issues resulting from acute methamphetamine exposure (AME) (Herbeck et al., 2015; Vrajová et al., 2021). Research on individuals who abuse methamphetamine has revealed that amphetamine-related effects on sleep manifest primarily as compromised sleep depth, shortened sleep duration, and decreased sleep quality (Rommel et al., 2015). Specific manifestations include prolonged sleep latency, reduced time in rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, shortened non-rapid eye movement 2 (NREM2) sleep, and more REM sleep episodes (Herrmann et al., 2017).

Due to their similarity to humans’ neurodevelopment, non-human primates serve as excellent pathological models for studying sleep disturbances induced by methamphetamine (Nunes et al., 2020; Vrajová et al., 2021). Previous research on human subjects has relied mainly on rough sleep data obtained through wristband measurements of limb activity. Recently, more precise sleep staging methods based on electroencephalogram (EEG) have been applied to this problem (Berro et al., 2022). Non-human primate sleep structure closely resembles that of humans, defined (from shallow to profound sleep) as the REM, NREM1, NREM2, and NREM3 stages (Ishikawa et al., 2017).

Rich sleep spindles, delta oscillations, and slow oscillations (SOs) are characteristics of NREM sleep (Schönauer and Pöhlchen, 2018; Kjaerby et al., 2022; Ruch et al., 2022). They play a crucial role as cortico-thalamic neurogenic oscillations mediating sleep homeostasis and sleep-related physiological functions (Bandarabadi et al., 2020). Sleep spindles not only directly contribute to deep sleep stability and quality but also exhibit temporal coupling with delta oscillation/SO, mediating the memory reactivation during sleep and thereby promoting emotional-cognitive enhancement (Maingret et al., 2016; Mendes et al., 2021; Lv et al., 2022; Kim et al., 2023). The phenomena of mutual exclusion and competition between delta-spindle and SO-spindle temporal coupling occur during sleep, facilitating memory consolidation and forgetting (Kim et al., 2019). However, it remains unclear whether these mechanisms are involved in another core function of sleep spindles, namely, maintaining sleep stability.

Previous research has clarified the significant disruptions of sleep duration and sleep architecture induced by AME (Berro et al., 2022). Building on this foundation, the present study focuses primarily on how neural oscillations and their interactions directly impact the destabilization of sleep homeostasis during AME. By recruiting oscillation coupling patterns that influence brain-wide sleep depth, we explored the mechanisms underlying disrupted neural oscillatory interactions (Maingret et al., 2016).

In this study, we assessed the impact of self-administered methamphetamine on EEG parameters in monkeys using a wireless recording system for continuous EEG and electromyogram (EMG) monitoring. By evaluating the influence of methamphetamine on sleep staging, we identified characteristic changes in sleep spindles and differentiated functionally distinct delta oscillations and SOs within similar frequency ranges. We examined the competitive effects of delta-spindle and SO-spindle temporal coupling under the influence of methamphetamine and observed a significant reduction in the suppressive effect of delta-spindle nesting on SO-spindle nesting. Furthermore, to assess the direct relevance of this process to sleep stability, we extracted sample entropy around delta-nested spindles and SO-nested spindles to characterize local sleep depth (Keshmiri, 2020), revealing differences in baseline functionality between the two spindle types; SO-nested spindles were weakened under the influence of methamphetamine.

2. Results

2.1. Experimental design and procedure of AME

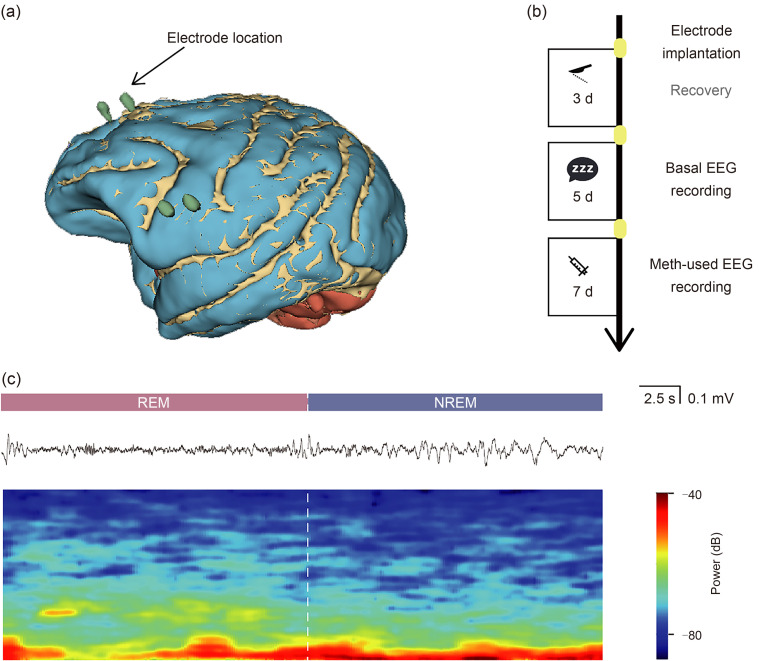

To investigate the effects of AME on monkey sleep structure, we surgically implanted electrocorticography (ECOG) electrodes into the cortices of three macaques and recorded their limb movements with an accelerometer. Electrode contact points were reconstructed using a three-dimensional (3D) slicer and computed tomography (CT) data to ensure consistency of location across individuals (Figs. 1a and S1a). Baseline data were continuously recorded for 5 d (approximately 120 h), after which each monkey received intravenous injections of methamphetamine at 1.5 mg/kg daily for 7 d (approximately 180 h) (Fig. 1b). Based on circadian rhythms, each monkey was observed for at least one daily sleep period exceeding 5 h. We extracted these continuous sleep periods and classified sleep stages based on synchronized EEG data, activity data, and a specific sleep-stage identification method, categorizing sleep into wakefulness, REM sleep, NREM1, NREM2, and NREM3 (Fig. 1c).

Fig. 1. Experimental design and procedure of acute methamphetamine exposure. (a) Schematic of surgical electrode implantation and electrode-position reconstruction, showing the precise arrangement of electrodes in specific locations. (b) Experimental procedure schematic illustrating the entire experimental process. (c) Sleep stage diagram depicting sleep stages of rapid eye movement (REM) and non-rapid eye movement (NREM) with raw wave representation and its heatmap features. EEG: electroencephalogram; Meth: methamphetamine.

2.2. Functional sleep impairment induced by AME

Significant alterations in the typical sleep structure were induced by AME, resulting in a noteworthy decrease in both REM and NREM sleep (Fig. 2a). This indicated that AME directly led to a reduction in total sleep time, a decrease in sleep quality, and disruption of monkey sleep homeostasis, which is consistent with early studies (Daley et al., 2006; Herrmann et al., 2017; Berro et al., 2022). To further investigate whether AME hinders the progression of sleep towards deeper stages, we calculated probability matrices for transitions between different sleep stages and visualized the comparisons in the form of chord diagrams (Fig. 2b). The results indicated that AME did not significantly impede transitions between any of the sleep stages.

Fig. 2. Functional sleep impairment induced by acute methamphetamine exposure (AME). (a) The total time of each sleep stage (rapid eye movement (REM), non-rapid eye movement 1 (NREM1), NREM2, and NREM3) after AME. AME significantly prolongs the total duration of REM sleep and shortens the total time of NREM2 and NREM3 sleep (n=14 in basal versus n=20 in meth, Mann-Whitney test of non-parameters test: for REM, P=0.0002; for NREM1, P=0.7178; for NREM2, P=0.0001; for NREM3, P<0.0001). (b) Chord diagram illustrating the probability of transitions between sleep stages. The left panel represents the baseline state, while the right panel depicts the state after AME. AME does not significantly impair the progression from REM to NREM sleep. (c) Average duration of segments of each sleep stage (REM, NREM1, NREM2, and NREM3). In addition to the significantly prolonged duration of individual REM sleep stages, impairment of NREM sleep stability mainly occurs during the NREM2 stage (for awake stage, n=51 in basal versus n=34 in meth, Mann-Whitney test of non-parameters test, P=0.0720; for REM, n=202 in basal versus n=381 in meth, Mann-Whitney test of non-parameters test, P<0.0001; for NREM1, n=238 in basal versus n=310 in meth, Mann-Whitney test of non-parameters test, P=0.4821; for NREM2, n=72 in basal versus n=22 in meth, Mann-Whitney test of non-parameters test, P=0.0012; for NREM3, n=156 in basal versus n=98 in meth, Mann-Whitney test of non-parameters test, P=0.2720). Data are expressed as mean±standard deviation (SD). n.s.: not significant. ** P<0.01, *** P<0.001, **** P<0.0001.Meth: methamphetamine.

Based on these results, to identify the specific sleep stages disrupted by AME and investigate the steady state, we measured the duration of each sleep stage before the transition to the next stage. Longer duration indicated greater stability in maintaining a sleep stage. We found a significant increase in REM sleep duration after AME, while NREM2 sleep duration significantly decreased; however, no significant changes were observed in other stages (Fig. 2c). These results indicated that NREM, particularly the NREM2 stage, may represent the sleep stages most susceptible to the influence of AME. Further analysis of the factors that influence sleep stability during this period is necessary.

2.3. Attenuation of sleep-spindle waves in NREM2 stage by AME

Sleep-spindle waves are an intrinsic neural oscillatory mechanism involved in maintaining sleep homeostasis and exhibit widespread activity throughout the cortex. We chose these EEG features for study due to their maintaining sleep stability. We extracted sleep-spindle waves and analyzed changes in their physiological characteristics after AME (Fig. 3a). The results revealed a significant attenuation of sleep-spindle waves after AME, with lower incidence (Fig. 3b), flattening of peak-trough amplitudes (Figs. S1b and S1c), reduction in average power (Fig. 3c), shortened duration (Fig. S1d), and uneven distribution (Figs. 3d and S1e). Among these features, the incidence of sleep-spindle waves is the most crucial factor in maintaining sleep homeostasis. We assessed the changes in the incidence of sleep-spindle waves during different sleep stages before and after AME. The results showed a significant decrease in the incidence of sleep-spindle waves during NREM2 sleep stages (Fig. 3e), with no significant change observed in NREM3 sleep (Fig. 3f). Additionally, no sleep-spindle waves were observed during NREM1 sleep. Thus, the disruption of sleep-spindle waves is one of the intrinsic mechanisms of sleep homeostasis disruption induced by AME.

Fig. 3. Attenuation of sleep-spindle waves in non-rapid eye movement 2 (NREM2) stage by acute methamphetamine exposure (AME). (a) Schematic representation of spindle waves identified in the raw waveform after 4‒12 Hz filtering during NREM sleep. (b) Spindle-wave incidence (count per second) during basal sleep period and AME sleep period (n=14 in basal versus n=20 in meth, Mann-Whitney test of non-parameters test, P<0.0001). (c) Average power of spindle waves during basal sleep period and AME sleep period (n=30 145 in basal versus n=28 904 in meth, Mann-Whitney test of non-parameters test, P<0.0001). (d) Average spindle waveform during basal sleep period and AME sleep period. AME induced a flatter waveform with lower amplitude and shorter duration, which leads to functional loss in sleep stability. Red curve indicated the basal; yellow curve indicated the meth. (e) Spindle-wave incidence in the NREM2 stage (count per second) during basal sleep period and AME sleep period (n=14 in basal versus n=20 in meth, Mann-Whitney test of non-parameters test, P<0.0001). (f) Spindle-wave incidence in the NREM3 stage (count per second) during basal sleep period and AME sleep period (n=14 in basal versus n=20 in meth, Mann-Whitney test of non-parameters test, P=0.3451). Data are expressed as mean±standard deviation (SD). n.s.: not significant. **** P<0.0001. Meth: methamphetamine.

2.4. Differential modulation of delta oscillations and SOs by AME

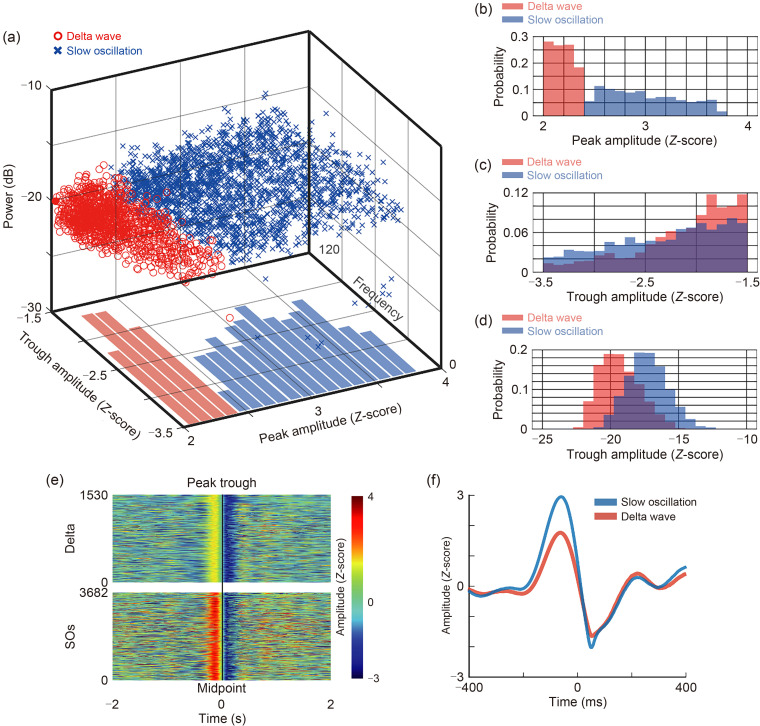

SO/delta waves are also considered essential oscillatory elements for maintaining sleep homeostasis, and have slight physiological differences despite their overlapping frequency ranges. The former primarily induces deep sleep, while the latter participates in mediating cognitive functions. Using the method reported by Kim et al. (2019), we extracted SOs and delta oscillations during the entire sleep period and classified them based on peak amplitude, trough amplitude, and power. Consistent with previous findings, SOs and delta oscillations were mainly distinguished by their peak amplitude, with similar trough amplitude distributions and significant overlap in average power distribution (Fig. 4a). SOs exhibited a significantly higher peak amplitude (Figs. 4b‒4f).

Fig. 4. Dissociation of delta waves and slow oscillations (SOs). (a) Delta waves and SOs from single monkeys in the basal sleep period stage (n=5). The scatter plot is based on Z-scored peaks of up states, Z-scored troughs of up states, and average power. (b) Distribution of Z-scored peaks of up states. The peak distribution of the delta wave is completely separated from the SO. (c) Distribution of Z-scored troughs in the up states of delta waves and SOs. (d) Distribution of average power of delta waves and SOs. SOs exhibit slightly higher power than delta waves. (e) Heatmap matrix which vertically stacks all original waveform heatmaps of delta wave and SOs. On the left side of the midpoint is the peak amplitude, and on the right side are the trough amplitudes. (f) Average waveform of SOs (n=1530 from five trials) and delta waves (n=3682 from five trials).

We compared the relevant features of SO/delta waves after AME. The results demonstrated that AME differentially affected delta oscillations and SOs. Firstly, AME significantly reduced the incidence of delta oscillations to nearly half the original value (Fig. 5a) and slightly lowered their average power (Fig. 5b). Concerning the waveform features, AME increased the amplitude of delta oscillations (Figs. S2a and S2b) but prolonged their latency, resulting in more uneven distribution (Fig. S2c). AME did not alter the incidence of SOs (Fig. 5c), but reduced average power (Fig. 5d) and amplitude without a significant impact on latency (Figs. S2d‒S2f). AME also induced differences across various sleep stages. In the NREM2 stage, AME only resulted in a decrease in delta occurrence without affecting SOs (Figs. 5e and 5f). In the NREM3 stage, it led to the disappearance of SOs and delta oscillations in some individuals, resulting in a significant overall decrease (Figs. 5g and 5h). These results indicated differential effects of AME on SOs and delta waves, laying the groundwork for further investigation of the intrinsic mechanisms of AME-induced sleep homeostasis disruption.

Fig. 5. Acute methamphetamine exposure (AME) differentially altering delta waves and slow oscillations (SOs). (a) Comparison of the delta incidence during non-rapid eye movement (NREM) in basal and AME periods (n=14 in basal versus n=20 in meth, unpaired t-test, P=0.0002). (b) Comparison of the average power of delta waves during NREM in basal and AME periods (n=93 204 delta in basal versus n=134 091 delta in meth, Mann-Whitney test of non-parameters test, P<0.0001). (c) Comparison of the incidence of SOs during NREM in baseline and AME periods (n=14 in basal versus n=20 in meth, unpaired t-test, P=0.1496). (d) Comparison of the average power of SOs during NREM in basal and AME periods (n=39 300 SOs in basal versus n=50 043 SOs in meth, Mann-Whitney test of non-parameters test, P<0.0001). (e) Comparison of the incidence of SOs during NREM2 sleep (n=14 in basal versus n=20 in meth, unpaired t-test, P=0.9343). (f) Comparison of the incidence of delta waves during NREM2 sleep (n=14 in basal versus n=20 in meth, unpaired t-test, P=0.0015). (g) Comparison of the incidence of SOs during NREM3 sleep (n=14 in basal versus n=20 in meth, Mann-Whitney test of non-parameters test, P=0.0033). (h) Comparison of the incidence of delta waves during NREM3 sleep (n=14 in basal versus n=20 in meth, Mann-Whitney test of non-parameters test, P=0.0004). Data are expressed as mean±standard deviation (SD). n.s.: not significant. ** P<0.01, *** P<0.001, **** P<0.0001. Meth: methamphetamine.

2.5. Competitive SO/delta-spindle nesting in AME-induced sleep disruption

Competitive nesting between SO/delta waves and sleep-spindle waves has been shown to play a role in cognitive processes. Increased nesting of sleep-spindle waves with delta waves leads to decreased nesting with SO waves, promoting memory consolidation (Kim et al., 2019). Building upon this conclusion and the aforementioned results, we explored the role of this competitive mechanism in AME-induced disruption of monkey sleep homeostasis.

First, we identified nesting of delta waves with sleep-spindle waves and nesting of SO waves with sleep-spindle waves and quantified them separately (Fig. 6a). We found a clear segregation effect, with AME leading to a significant decrease in the incidence of delta-spindle nesting and a significant increase in the incidence of SO-spindle nesting (Figs. 6b and 6c). Subsequently, changes in the distribution of spindle probabilities around the nesting time window were consistent between delta and SO waves: both decreased after AME (Figs. 6d and 6e). This indicated a weakening of the recruitment of spindle waves by both delta and SO waves after AME. To further quantitatively describe recruitment of spindles by SO/delta waves, we obtained the corresponding nesting index by calculating the firing rate of spindles within nesting time windows (Figs. 6f and 6g). Finally, to determine the competitive relationship between SO and delta waves while eliminating the influence of baseline firing rates, we calculated the ratio of the proportion of delta-nested spindles to SO-nested spindles as the delta/SO competing index. It showed a significant decrease in the SO/delta competition index after AME, with an almost twofold difference in average value (Fig. 6h). This implies that the enhancement of coupling between SO waves and spindles is established based on their competitive interaction with delta-spindle coupling.

Fig. 6. Strengthened competitive spindle nesting of slow oscillations (SOs) over delta waves by acute methamphetamine exposure (AME). (a) Schematic diagram illustrating the independent nesting of SOs and delta waves with spindles. The waveforms represent the SO, spindle wave, and delta wave from the filtered signal. The dashed line indicates the starting point of the down state, which is also the beginning time-point of nesting. (b) Delta-spindle nesting incidence (per minute) changes from basal to AME periods (n=14 in basal versus n=20 in meth, unpaired t-test, P=0.0051). (c) SO-spindle nesting incidence (per minute) changes from basal to AME periods (n=14 in basal versus n=20 in meth, unpaired t-test, P=0.0238). (d) Peri-delta-nesting distribution of spindle wave in basal (red line) and AME periods (yellow line). Lines and dots represent the means, and shading represents the standard error of the mean (SEM). (e) Peri-SO-nesting distribution of spindle waves in basal (red line) and AME periods (yellow line). Lines and dots represent the means, and shading represents SEM. (f) Delta-nesting index changes from basal to AME periods (n=14 in basal versus n=20 in meth, unpaired t-test, P=0.8559). (g) SO-nesting index changes from basal to AME periods (n=14 in basal versus n=20 in meth, unpaired t-test, P<0.0001). (h) Delta/SO competing index changes from basal to AME periods, calculated based on the ratio of spindles involved in delta nesting to the ratio of spindles involved in SO nesting, reflecting the competitive recruitment effects of the two types of nesting (n=14 in basal versus n=20 in meth, unpaired t-test, P<0.0001). Data are expressed as mean±standard deviation (SD). n.s.: not significant. * P<0.05, ** P<0.01, **** P<0.0001. Meth: methamphetamine.

The enhanced competitive coupling between SO waves and spindles does not directly lead to conclusions regarding its impact on sleep stability. Therefore, we hypothesize that there might be some physiological abnormalities associated with SO-nested spindles. To validate this hypothesis regarding the role of AME in disrupting sleep stability, we separately extracted SO-nested spindles, delta-nested spindles, and non-nested spindles (Fig. 7a). The overall sample entropy of EEG around the three types of spindle waves was calculated, and lower sample entropy represented a lower overall wakefulness level of the brain, directly related to sleep depth (Fig. 7a). For SO-nested spindles, although AME increased their occurrence and competitive roles, the process of reduced entropy mediated by them under baseline conditions (purple line at top of Fig. 7b) showed significant attenuation after AME (purple line at bottom of Fig. 7b). It was evident that there was a significant increase in complexity around SO-nested spindle waves, indicating a gradual loss of physiological function in some spindles after AME. These spindles became coupled with SO waves, contributing to the overall disruption of sleep homeostasis. In Fig. 7b, the complexity around non-nested spindles remained relatively stable both before and after AME. Meanwhile, the trend of sample entropy changes around delta-nested spindles exhibited an opposite pattern to that of SO-nested spindles overall. This finding indicates physiological differences between the two, with the former potentially associated with cognitive consolidation and the latter more involved in sleep homeostasis, leading to the disruption of sleep structure after AME.

Fig. 7. Acute methamphetamine exposure (AME) impairing slow oscillations (SOs)-nested spindles in sleep stability maintenance. (a) Schematic diagram of sample entropy calculation. Spindle waves were divided into three groups: nested with delta waves, nested with SOs, and non-nested spindles. To mitigate the silencing effects of SO/delta-mediated down states, sample entropy was computed within a time window (Δt) consisting of the first 20 s following the peak of the first spindle wave after the end of the down state. For each time window, sample entropy was computed using a sliding window approach with a width of 1 s and a step size of 1 s. (b) Average peri-event entropy for delta-nested spindles, SO-nested spindles, and non-nested spindles in baseline (top) and AME (bottom) periods. The entropy around delta-nested spindles and SO-nested spindles exhibits completely opposite activity, while non-nested spindles occupy an intermediate position. AME also induces a flatter entropy profile around SO-nested spindles. Solid lines represent the means, and the dashed line represents the standard error of the mean (SEM). The gray semi-transparent line indicates the average value of entropy. The statistical results are based on the average sample entropy around the gray box for events. The significance markers indicate the statistical results between the average peri-spindle sample entropy (for peri-delta-nested spindle entropy, n=3494 in basal versus n=3414 in meth, unpaired t-test, **** P<0.0001; for peri-SO-nested spindle entropy, n=13 996 in basal versus n=8861 in meth, unpaired t-test, **** P<0.0001).

3. Discussion

In this study, we investigated the impact of AME on the sleep state of monkeys through continuous recording of EEG-EMG data. Utilizing implanted and wearable devices with wireless technology, we longitudinally collected data in freely moving monkeys. The study refrained from imposing light-dark cycles on the monkeys’ living environment, maintaining sleep under natural lighting conditions for 8‒12 h to minimize environmental interference. Basic sleep states were roughly identified with cameras, and fine staging was performed based on EEG-EMG data.

With regard to the influence of AME on sleep structure, our results indicate a significant deterioration in the depth of monkey sleep. Specifically, there were notable reductions in the length of both NREM2 and NREM3 periods. NREM3, in particular, disappeared frequently in nearly half of the trials. Building upon these findings, we further explored whether there were disruptions in the progression of sleep following AME exposure, particularly during an intermediate phase. Analysis of sleep-transform probabilities and average durations revealed a substantial decrease in stability during NREM2 (Troynikov et al., 2018). Combined with the shortened duration of NREM3, this suggests a tendency for NREM2 to transition to wakefulness in an unstable manner after AME (Shalaby et al., 2022). Previous studies, including investigations on methamphetamine abusers and non-human primate models, have consistently shown that acute or chronic exposure to methamphetamine can lead to sleep-wake behavior dysregulation and sustained disruption of sleep cycles, including reduced total sleep time, prolonged sleep-onset latency, and diminished self-reported sleep quality (Vrajová et al., 2021). However, the manifestation of these effects may vary depending on the effective dose of methamphetamine.

Perez et al. (2008) initially observed in methamphetamine abusers that the impact of the drug on total sleep duration is dose-dependent, with acute sleep disturbances reliably induced only at oral doses above 0.7 mg/kg. Therefore, we employed a 1 mg/kg intravenous injection to investigate the neurophysiological mechanisms underlying AME-induced sleep disruption. Murnane et al. (2013) demonstrated in rhesus monkeys that an oral dose of 0.5 mg/kg failed to consistently induce sleep disturbances. Similarly, Berro et al. (2016) administered methamphetamine intravenously at doses of 0.01, 0.10, and 0.30 mg/kg in rhesus monkeys without observing significant changes in total sleep duration.

The differences between these reports and the findings in our study are likely primarily due to variations in dosage. Additionally, there are differences in the assessment of sleep structure. While prior studies mainly relied on activity-measuring wristbands, we employed a combination of wristbands and multi-channel sleep EEG signals for more precise sleep staging (Vrajová et al., 2021). Furthermore, previous research has indicated that in healthy individuals exposed to acute methamphetamine, tolerance to methamphetamine’s sleep-disrupting effects tends to develop gradually, with a diminishing impact approximately five days later (Comer et al., 2001). However, we did not observe this phenomenon in our study, which may also be linked to the dosage administered. It is important to note that studies investigating chronic methamphetamine exposure did not report this phenomenon, even at lower doses such as 0.01 mg/kg, which could still disrupt sleep parameters (Andersen et al., 2013).

Apart from total sleep duration, methamphetamine dosage may also dictate its effects on the NREM sleep stage. While most research on sleep cycles in humans and non-human primates primarily indicates a reduction in the duration of NREM periods, Herrmann et al. (2017) observed that recreational methamphetamine use did not significantly impact the duration of NREM3 periods. This discrepancy can be attributed not only to differences in species and administration routes (oral and intravenous), but more importantly, to the dose dependency of methamphetamine’s sleep effects. They primarily administered doses ranging from 0.3 mg/kg to 0.5 mg/kg. Considering additional studies investigating changes in sleep parameters across various doses, lower doses are unlikely to decrease the duration of NREM3 periods, while doses above 1.0 mg/kg can reliably induce this phenomenon (Perez et al., 2008). It is worth noting that another study using a dose of 1.3 mg/kg also found a reduction in the duration of NREM3 periods and disruption of sleep structure (Berro et al., 2022).

Building upon the impact of AME on NREM3 sleep, SOs and delta oscillations emerge as distinct electroencephalographic features of the NREM3 period, garnering further attention (Diekelmann and Born, 2010). At the synaptic level, methamphetamine’s influence on sleep primarily involves the monoaminergic and dopaminergic pathways (Paulus and Stewart, 2020). One of its crucial effects is the inhibition of monoamine transporters and dopamine transporters at the terminals of dopaminergic neurons, which affects the sleep process through projections from the midbrain to the frontal cortex (Brodt et al., 2023). Research indicates that during this process, there is a lengthening of the firing time of dopaminergic neurons, which potentially affects a broad spectrum of SOs and delta oscillations by modulating inhibitory post-synaptic potentials; this could lead to disrupted oscillatory-mediated information exchange in the frontal cortex (Hedges et al., 2018).

Utilizing EEG electrodes positioned in the frontal lobe, we effectively captured SOs and delta oscillations originating from this brain region. Conversely, sleep-spindle waves predominantly stem from the thalamus. During the up state of SOs, neurons in the thalamic reticular nucleus are influenced by the widespread depolarization of cortical neurons, giving rise to spindle oscillations. These oscillations then propagate via thalamocortical projections to the frontal lobe cortex, thereby contributing to the maintenance of sleep stability in the brain (Brodt et al., 2023). However, prior imaging studies have indicated a marked reduction in thalamocortical pathway activity in individuals using methamphetamine. This hindrance of the feedback process may represent one of the microstructural underpinnings for the diminished activity of spindles under the influence of methamphetamine (Andersen et al., 2013).

Sleep-spindle waves represent a crucial functional neural oscillation for maintaining sleep stability during NREM periods (Castelnovo et al., 2016; Brockmann et al., 2020; Weng et al., 2020; Kaulen et al., 2022). Increasing spindle waves has been shown to directly improve various sleep disorders and enhance sleep quality (Joechner et al., 2023). Our study observed not only a reduction in the number of sleep spindles in cortical EEG after AME but also a functional decline characterized by a shortened duration, decreased amplitude, and an overall flattened trend. Specifically, the decrease in sleep-spindle quantity was prominent during NREM2, aligning with the instability observed in this stage. This finding suggests a significant role for AME-induced disruptions of sleep-spindle activity, particularly in NREM2 instability (Chen et al., 2023).

The precise temporal coordination between SO/delta waves and sleep spindles is a critical characteristic of NREM sleep. This process primarily occurs in the frontal cortex, where SOs/delta oscillations induce spindles that propagate from the thalamus to the frontal cortex and establish coupling. Previous studies have shown that the efficiency and temporal accuracy of this coupling regulate various physiological functions during sleep, and its reduced precision correlates with dysfunction in the frontal-thalamic network (Helfrich et al., 2018; Muehlroth et al., 2019). Methamphetamine exposure has been demonstrated to notably diminish both the volume and functionality of the thalamus (Volkow et al., 2001; Morales et al., 2015; Li et al., 2017; Warton et al., 2018).

The nesting of SOs/delta oscillations with sleep-spindle waves is a critical mediator for the physiological function of spindle waves (Kim et al., 2019). Previous research has demonstrated that the precise timing relationship between delta waves and spindles and between SO waves and spindles contributes to cognitive enhancement during sleep (Miyamoto et al., 2017; Kim et al., 2019; Hahn et al., 2020). In the competition between delta-spindle and SO-spindle nesting, our study showed an enhancement of SO-spindle nesting and a reduction of delta-spindle nesting after AME exposure. The competitive mechanism found in our study, involving stronger recruitment of spindles by SOs and a doubling of the proportion of spindles involved in SO nesting, indicates a significant impact on sleep stability.

In the absence of abnormalities, SO-spindle nesting is a factor in maintaining sleep stability (Malkani and Zee, 2020; Girardeau and Lopes-Dos-Santos, 2021). Therefore, AME-induced enhancement of SO-spindle nesting is likely a pathological factor leading to the loss of normal function. This study introduces sample entropy from information theory as an evaluation metric, with increased sample entropy associated with decreased neuronal activity during deepening sleep (Ma et al., 2018; Hou et al., 2021; Liang et al., 2021; Sathyanarayana et al., 2021). Analysis of sample entropy around spindle events categorized as SO-nested, delta-nested, and non-nested spindles reveals a significant increase in sample entropy around SO-nested spindles after AME, indicating a loss of sleep-stabilizing function. Notably, baseline conditions show a clear opposite trend in sample entropy around delta-nested spindles compared to SO-nested spindles, which highlights functional differences. Delta-nested spindles are primarily implicated in cognitive function enhancement, while SO-nested spindles play a key role in sleep stability (Zhang et al., 2021).

In summary, this study of monkey sleep stability following AME not only highlights significant changes in sleep structure but also reveals multiple key alterations at the neural oscillation level. The detailed analysis of the competition between SO-spindle and delta-spindle nesting sheds light on AME-induced enhancement of SO-spindle nesting and reduction of delta-spindle nesting. This competitive mechanism may adversely affect cognitive function, particularly through the failure of SO-spindle nesting (Kim et al., 2019). We hope that this more comprehensive understanding will contribute to elucidating the impact of AME on monkey sleep stability, as it emphasizes neural oscillation changes as a critical factor in the diverse effects induced by AME.

Materials and methods

Detailed methods are provided in the electronic supplementary materials of this paper.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82271515), the SJTU Trans-Med Awards Research (No. 2019015), the Scientific and Technological Innovation Action Plan of Shanghai (No. KY20211478), the Shanghai Municipal Science and Technology Major Project (No. 2021SHZDZX), the Nursing Development Program of Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine (No. SJTUHLXK2022), the 2024 Shanghai Ruijin Hospital Nursing Research Fund (No. RJHK-2024-001), and the Shanghai Nursing Association Funding (No. 2024MS-B13), China. We would like to express our gratitude to Shanghai Quanlan Technology Co., Ltd. for the technical support.

AUTHORS’CONTRIBUTIONS

Xin LV proposed the research hypothesis, designed the experiments, conducted the data analysis, and drafted the paper. Jie LIU and Shuo MA collected the experimental data, with assistance from Yuhan WANG, Yixin PAN, and Xian QIU. Yu CAO contributed to the revision of the manuscript. Bomin SUN provided funding for the research. Shikun ZHAN supervised the study design and the dataset collection. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript, and therefore, have full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity and security of the data.

Compliance with ethics guidelines

Xin LV, Jie LIU, Shuo MA, Yuhan WANG, Yixin PAN, Xian QIU, Yu CAO, Bomin SUN, and Shikun ZHAN declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

All experimental procedures received approval from the Animal Committee of the Institute of Neuroscience and the Center for Excellence in Brain Science and Intelligence Technology, Chinese Academy of Sciences. Animal care protocols adhered to the U.S. National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (identification number: CEBSIT-2022003R01).

Data availability statement

The data and custom code that support the findings from this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- Andersen ML, Diaz MP, Murnane KS, et al. , 2013. Effects of methamphetamine self-administration on actigraphy-based sleep parameters in rhesus monkeys. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 227(1): 101-107. 10.1007/s00213-012-2943-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baingana F, al'Absi M, Becker AE, et al. , 2015. Global research challenges and opportunities for mental health and substance-use disorders. Nature, 527(7578): S172-S177. 10.1038/nature16032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandarabadi M, Herrera CG, Gent TC, et al. , 2020. A role for spindles in the onset of rapid eye movement sleep. Nat Commun, 11: 5247. 10.1038/s41467-020-19076-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassetti CLA, Adamantidis A, Burdakov D, et al. , 2019. Narcolepsy—clinical spectrum, aetiopathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment. Nat Rev Neurol, 15(9): 519-539. 10.1038/s41582-019-0226-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berro LF, Andersen ML, Tufik S, et al. , 2016. Actigraphy-based sleep parameters during the reinstatement of methamphetamine self-administration in rhesus monkeys. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol, 24(2): 142-146. 10.1037/pha0000064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berro LF, Overton JS, Rowlett JK, 2022. Methamphetamine-induced sleep impairments and subsequent slow-wave and rapid eye movement sleep rebound in male rhesus monkeys. Front Neurosci, 16: 866971. 10.3389/fnins.2022.866971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockmann PE, Bruni O, Kheirandish-Gozal L, et al. , 2020. Reduced sleep spindle activity in children with primary snoring. Sleep Med, 65: 142-146. 10.1016/j.sleep.2019.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodt S, Inostroza M, Niethard N, et al. , 2023. Sleep—a brain-state serving systems memory consolidation. Neuron, 111(7): 1050-1075. 10.1016/j.neuron.2023.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castelnovo A, D'Agostino A, Casetta C, et al. , 2016. Sleep spindle deficit in schizophrenia: contextualization of recent findings. Curr Psychiatry Rep, 18(8): 72. 10.1007/s11920-016-0713-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Wang K, Belkacem AN, et al. , 2023. A comparative analysis of sleep spindle characteristics of sleep-disordered patients and normal subjects. Front Neurosci, 17: 1110320. 10.3389/fnins.2023.1110320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comer SD, Hart CL, Ward AS, et al. , 2001. Effects of repeated oral methamphetamine administration in humans. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 155(4): 397-404. 10.1007/s002130100727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruickshank CC, Dyer KR, 2009. A review of the clinical pharmacology of methamphetamine. Addiction, 104(7): 1085-1099. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02564.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daley JT, Turner RS, Freeman A, et al. , 2006. Prolonged assessment of sleep and daytime sleepiness in unrestrained Macaca mulatta . Sleep, 29(2): 221-231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diekelmann S, Born J, 2010. The memory function of sleep. Nat Rev Neurosci, 11(2): 114-126. 10.1038/nrn2762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazel S, Långström N, Hjern A, et al. , 2009. Schizophrenia, substance abuse, and violent crime. JAMA, 301(19): 2016-2023. 10.1001/jama.2009.675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girardeau G, Lopes-Dos-Santos V, 2021. Brain neural patterns and the memory function of sleep. Science, 374(6567): 560-564. 10.1126/science.abi8370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn MA, Heib D, Schabus M, et al. , 2020. Slow oscillation-spindle coupling predicts enhanced memory formation from childhood to adolescence. eLife, 9: e53730. 10.7554/eLife.53730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedges DM, Obray JD, Yorgason JT, et al. , 2018. Methamphetamine induces dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens through a sigma receptor-mediated pathway. Neuropsychopharmacology, 43(6): 1405-1414. 10.1038/npp.2017.291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helfrich RF, Mander BA, Jagust WJ, et al. , 2018. Old brains come uncoupled in sleep: slow wave-spindle synchrony, brain atrophy, and forgetting. Neuron, 97(1): 221-230.e4. 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.11.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbeck DM, Brecht ML, Lovinger K, 2015. Mortality, causes of death, and health status among methamphetamine users. J Addict Dis, 34(1): 88-100. 10.1080/10550887.2014.975610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann ES, Johnson PS, Bruner NR, et al. , 2017. Morning administration of oral methamphetamine dose-dependently disrupts nighttime sleep in recreational stimulant users. Drug Alcohol Depend, 178: 291-295. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou FZ, Zhang LL, Qin BK, et al. , 2021. Changes in EEG permutation entropy in the evening and in the transition from wake to sleep. Sleep, 44(4): zsaa226. 10.1093/sleep/zsaa226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa A, Sakai K, Maki T, et al. , 2017. Investigation of sleep-wake rhythm in non-human primates without restraint during data collection. Exp Anim, 66(1): 51-60. 10.1538/expanim.16-0073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joechner AK, Hahn MA, Gruber G, et al. , 2023. Sleep spindle maturity promotes slow oscillation-spindle coupling across child and adolescent development. eLife, 12: e83565. 10.7554/eLife.83565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaulen L, Schwabedal JTC, Schneider J, et al. , 2022. Advanced sleep spindle identification with neural networks. Sci Rep, 12: 7686. 10.1038/s41598-022-11210-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keshmiri S, 2020. Entropy and the brain: an overview. Entropy (Basel), 22(9): 917. 10.3390/e22090917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Gulati T, Ganguly K, 2019. Competing roles of slow oscillations and delta waves in memory consolidation versus forgetting. Cell, 179(2): 514-526.e13. 10.1016/j.cell.2019.08.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Joshi A, Frank L, et al. , 2023. Cortical-hippocampal coupling during manifold exploration in motor cortex. Nature, 613(7942): 103-110. 10.1038/s41586-022-05533-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjaerby C, Andersen M, Hauglund N, et al. , 2022. Memory-enhancing properties of sleep depend on the oscillatory amplitude of norepinephrine. Nat Neurosci, 25(8): 1059-1070. 10.1038/s41593-022-01102-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li YD, Dong HB, Li F, et al. , 2017. Microstructures in striato-thalamo-orbitofrontal circuit in methamphetamine users. Acta Radiol, 58(11): 1378-1385. 10.1177/0284185117692170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang XY, Xiong JL, Cao ZT, et al. , 2021. Decreased sample entropy during sleep-to-wake transition in sleep apnea patients. Physiol Meas, 42(4): 044001. 10.1088/1361-6579/abf1b2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv X, Zhang XL, Zhao Q, et al. , 2022. Acute stress promotes brain oscillations and hippocampal-cortical dialog in emotional processing. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 598: 55-61. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2022.01.116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y, Shi WB, Peng CK, et al. , 2018. Nonlinear dynamical analysis of sleep electroencephalography using fractal and entropy approaches. Sleep Med Rev, 37: 85-93. 10.1016/j.smrv.2017.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maingret N, Girardeau G, Todorova R, et al. , 2016. Hippocampo-cortical coupling mediates memory consolidation during sleep. Nat Neurosci, 19(7): 959-964. 10.1038/nn.4304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malkani RG, Zee PC, 2020. Brain stimulation for improving sleep and memory. Sleep Med Clin, 15(1): 101-115. 10.1016/j.jsmc.2019.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElroy SL, 2017. Pharmacologic treatments for binge-eating disorder. J Clin Psychiatry, 78(Suppl 1): 14-19. 10.4088/JCP.sh16003su1c.03 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendes RAV, Zacharias LR, Ruggiero RN, et al. , 2021. Hijacking of hippocampal-cortical oscillatory coupling during sleep in temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav, 121: 106608. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2019.106608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto D, Hirai D, Murayama M, 2017. The roles of cortical slow waves in synaptic plasticity and memory consolidation. Front Neural Circuits, 11: 92. 10.3389/fncir.2017.00092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales AM, Kohno M, Robertson CL, et al. , 2015. Gray-matter volume, midbrain dopamine D2/D3 receptors and drug craving in methamphetamine users. Mol Psychiatry, 20(6): 764-771. 10.1038/mp.2015.47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muehlroth BE, Sander MC, Fandakova Y, et al. , 2019. Precise slow oscillation-spindle coupling promotes memory consolidation in younger and older adults. Sci Rep, 9: 1940. 10.1038/s41598-018-36557-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murnane KS, Andersen ML, Rice KC, et al. , 2013. Selective serotonin 2A receptor antagonism attenuates the effects of amphetamine on arousal and dopamine overflow in non-human primates. J Sleep Res, 22(5): 581-588. 10.1111/jsr.12045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunes EV, Kunz K, Galanter M, et al. , 2020. Addiction psychiatry and addiction medicine: the evolution of addiction physician specialists. Am J Addict, 29(5): 390-400. 10.1111/ajad.13068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulus MP, Stewart JL, 2020. Neurobiology, clinical presentation, and treatment of methamphetamine use disorder: a review. JAMA Psychiatry, 77(9): 959-966. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.0246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez AY, Kirkpatrick MG, Gunderson EW, et al. , 2008. Residual effects of intranasal methamphetamine on sleep, mood, and performance. Drug Alcohol Depend, 94(1-3): 258-262. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.10.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner J, Polanczyk GV, Sonuga-Barke E, 2020. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Lancet, 395(10222): 450-462. 10.1016/s0140-6736(19)33004-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rommel N, Rohleder NH, Wagenpfeil S, et al. , 2015. Evaluation of methamphetamine-associated socioeconomic status and addictive behaviors, and their impact on oral health. Addict Behav, 50: 182-187. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.06.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruch S, Schmidig FJ, Knüsel L, et al. , 2022. Closed-loop modulation of local slow oscillations in human NREM sleep. Neuroimage, 264: 119682. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2022.119682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sathyanarayana A, el Atrache R, Jackson M, et al. , 2021. Measuring the effects of sleep on epileptogenicity with multifrequency entropy. Clin Neurophysiol, 132(9): 2012-2018. 10.1016/j.clinph.2021.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schönauer M, Pöhlchen D, 2018. Sleep spindles. Curr Biol, 28(19): R1129-R1130. 10.1016/j.cub.2018.07.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalaby AS, Bahanan AO, Alshehri MH, et al. , 2022. Sleep deprivation & amphetamine induced psychosis. Psychopharmacol Bull, 52(3): 31-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun HQ, Chen HM, Yang FD, et al. , 2014. Epidemiological trends and the advances of treatments of amphetamine-type stimulants (ATS) in China. Am J Addict, 23(3): 313-317. 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2014.12116.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troynikov O, Watson CG, Nawaz N, 2018. Sleep environments and sleep physiology: a review. J Therm Biol, 78: 192-203. 10.1016/j.jtherbio.2018.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Emmerik-van Oortmerssen K, van de Glind G, van den Brink W, et al. , 2012. Prevalence of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in substance use disorder patients: a meta-analysis and meta-regression analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend, 122(1-2): 11-19. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vivolo-Kantor AM, Hoots BE, Seth P, et al. , 2020. Recent trends and associated factors of amphetamine-type stimulant overdoses in emergency departments. Drug Alcohol Depend, 216: 108323. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Chang LD, Wang GJ, et al. , 2001. Higher cortical and lower subcortical metabolism in detoxified methamphetamine abusers. Am J Psychiatry, 158(3): 383-389. 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.3.383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vrajová M, Šlamberová R, Hoschl C, et al. , 2021. Methamphetamine and sleep impairments: neurobehavioral correlates and molecular mechanisms. Sleep, 44(6): zsab001. 10.1093/sleep/zsab001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warton FL, Meintjes EM, Warton CMR, et al. , 2018. Prenatal methamphetamine exposure is associated with reduced subcortical volumes in neonates. Neurotoxicol Teratol, 65: 51-59. 10.1016/j.ntt.2017.10.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weng YY, Lei X, Yu J, 2020. Sleep spindle abnormalities related to Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic mini-review. Sleep Med, 75: 37-44. 10.1016/j.sleep.2020.07.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteford HA, Degenhardt L, Rehm J, et al. , 2013. Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: findings from the global burden of disease study 2010. Lancet, 382(9904): 1575-1586. 10.1016/s0140-6736(13)61611-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winslow BT, Voorhees KI, Pehl KA, 2007. Methamphetamine abuse. Am Fam Physician, 76(8): 1169-1174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang ZY, Campbell IG, Dhayagude P, et al. , 2021. Longitudinal analysis of sleep spindle maturation from childhood through late adolescence. J Neurosci, 41(19): 4253-4261. 10.1523/jneurosci.2370-20.2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data and custom code that support the findings from this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.