Abstract

Background

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common sustained arrhythmia and is linked to increased risk of stroke, heart failure, and mortality. Circulating extracellular RNAs (exRNAs), which regulate gene expression and reflect underlying biological processes, are potential biomarkers for atrial fibrillation.

Methods

As part of an ongoing, larger study into extracellular RNAs (exRNAs) as potential biomarkers for cardiovascular disease, we analyzed exRNA profiles in a subset of 296 survivors of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) enrolled in the Transitions, Risks, and Actions in Coronary Events Center for Outcomes Research and Education (TRACE-CORE) cohort. A total of 318 exRNAs were quantified, selected a priori based on prior findings from the Framingham Heart Study. We assessed associations between circulating exRNAs and echocardiographic intermediate phenotypes relevant to atrial fibrillation (AF), including left atrial dimension, left ventricular (LV) mass, LV end-diastolic volume, and global longitudinal strain. Subsequently, we used logistic regression models to evaluate whether the exRNAs associated with these phenotypes were also associated with a history of AF (n = 18, 5.4%). Downstream bioinformatics analyses were performed to identify putative target genes, enriched gene ontology categories, and molecular pathways regulated by these candidate microRNAs.

Results

We identified 77 extracellular RNAs (exRNAs) that were significantly associated with increased left ventricular (LV) mass and at least one additional echocardiographic intermediate phenotype. Among these, miR-17-5p and miR-574-3p were also significantly associated with a history of atrial fibrillation (AF), with odds ratios of 1.58 (95% CI: 1.10–2.26) and 2.16 (95% CI: 1.03–4.54), respectively. Predicted gene targets of these miRNAs were enriched in pathways implicated in atrial remodeling and arrhythmogenesis. Key overlapping canonical pathways included the Senescence Pathway, Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Signaling, ERK5 Signaling, RHO GTPase Cycle, and HGF Signaling.

Conclusions

Circulating exRNAs, including miR-17-5p and miR-574-3p, are associated with cardiac remodeling and a history of AF in ACS survivors. These findings highlight their potential as biomarkers of atrial remodeling and implicate key molecular pathways involved in AF pathogenesis.

Keywords: atrial fibrillation, echophenotypes, microRNA, biomarker, adverse cardiac remodeling

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is highly prevalent and is associated with significant morbidity, such as stroke and heart failure (1). Although, much is known about the sequelae about AF, the mechanisms by which AF arises and persists are not completely understood. Advancing our understanding of the maladaptive cellular and molecular responses that contribute to AF pathogenesis is critical for improving prevention and treatment strategies. Furthermore, the identification of robust biomarkers may enable risk stratification of individuals at elevated risk for the development of AF.

Small noncoding RNAs, particularly microRNAs (miRNAs), play pivotal roles in regulating cellular signaling pathways in both physiological and pathological contexts. MiRNAs are ∼22 nucleotide noncoding RNAs that modulate gene expression post-transcriptionally and have been shown to influence cardiac development, hypertrophy, fibrosis, and adverse remodeling in response to stressors (2, 3). Extracellular RNAs (ex-RNAs) are endogenous small noncoding RNAs that exist in the plasma with remarkable stability and may reflect cellular states and cellular communication (4). Ex-RNAs have emerged as promising biomarkers in cardiovascular disease, including AF. Although there are several reports implicating ex-RNAs in AF (5–7), few studies have analyzed miRNA profiles of patients with AF in the setting of acute coronary syndrome. Data illustrating the expression of plasma ex-RNAs in the acute clinical setting could provide relevant ex-RNA biomarkers and shed light on the molecular mechanisms underlying clinical AF.

Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) is a widely utilized, noninvasive imaging modality that provides quantitative assessments of cardiac structure and function. It is an essential tool for the diagnosis, management, and prognostication of cardiovascular disease (8). Structural remodeling observed via echocardiography—such as increased left atrial size, reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), and elevated left ventricular mass (LV mass)—has been consistently associated with prevalent and incident AF (9, 10). Furthermore, changes in echocardiographic phenotypes are associated with severity of the disease (11). The high utility of echocardiographic parameters in the evaluation AF severity is due to its ability to define structural processes underpinning pathological cardiac remodeling. Although echocardiographic phenotypes associated with AF are well known, the molecular basis for pathological cardiac remodeling is less understood.

To address this knowledge gap, we investigated the expression of circulating ex-RNAs in relation to echocardiographic indices of cardiac remodeling and clinical AF in a cohort of hospitalized ACS survivors. Using a two-step analysis strategy, we first identified ex-RNAs associated with echocardiographic phenotypes linked to pathological remodeling and subsequently examined their associations with prevalent AF. Our study leveraged data from the Transitions, Risks, and Actions in Coronary Events (TRACE-CORE) cohort, applying a mechanistic framework to nominate candidate ex-RNAs with potential roles in AF pathogenesis.

Methods

Study population

The design, participant recruitment strategy, interview protocols, and medical record abstraction methods employed in the Transitions, Risks, and Actions in Coronary Events (TRACE-CORE) study have been described in detail previously (12, 13). In brief, the TRACE-CORE study is a multicenter, prospective cohort study designed to examine recovery trajectories and long-term outcomes among patients hospitalized with acute coronary syndrome (ACS). TRACE-CORE utilized a six-site prospective cohort design to follow 2,187 patients discharged after an ACS hospitalization between April 2011 and May 2013 (Figure 1). In Massachusetts, participating sites included the two teaching hospitals (University and Memorial) that comprise UMass Memorial Medical Center (UMMMC), a large academic medical center, as well as St. Vincent Hospital, a major community hospital. These three hospitals provide care for the majority of ACS hospitalizations in central Massachusetts. In Georgia, sites included Northside and Piedmont Hospitals—community hospitals in Atlanta affiliated with Kaiser Permanente Georgia—and the Medical Center of Central Georgia, a major cardiac referral center located in Macon serving central and southern Georgia. At the sites in Central Massachusetts, 411 blood samples were collected, processed as described previously and plasma was stored in −80°C (4, 14). Of the plasma collected, 296 were of sufficient quality for RNA extraction and qPCR experiment. The institutional review boards at each participating recruitment site approved this study. All participants provided written informed consent.

Figure 1.

Sample selection for the analyses from the transitions, risks and action in coronary events (TRACE-CORE) study.

Ascertainment of AF

Trained study staff abstracted participants' baseline demographic, clinical, laboratory, and electrocardiographic data and in-hospital clinical complications from available hospital medical records. AF was identified through medical record abstraction during the index hospitalization, based on clinician documentation, electrocardiogram (ECG) findings, and telemetry reports. AF subtype (paroxysmal, persistent, or permanent) and episode duration were not recorded and thus were not captured in this analysis. Co-morbidities present at the time of hospital admission were identified from each participant's admission history and physical examination. Any patient with documentation of AF by a trained medical provider was considered to have prevalent AF.

ex-RNA selection and profiling

As part of a transcriptomic profiling study, venous blood samples were collected during the index hospitalization from 296 participants enrolled in the TRACE-CORE cohort. Detailed protocols for blood processing, plasma storage, and RNA isolation have been described previously (14). Methods for the quantification of ex-RNAs, including miRNAs and small nucleolar RNAs (snoRNAs), have also been previously published (4). The panel of ex-RNAs was selected a priori based on prior data from the Framingham Heart Study (4). Plasma ex-RNA profiling was conducted at the High-Throughput Gene Expression & Biomarker Core Laboratory at the University of Massachusetts Medical School. Ex-RNA expression levels were reported as quantification cycle (Cq) values, with higher Cq values indicating lower transcript abundance. This approach resulted in the detection of 318 miRNAs. Additional methodological details are provided in the Supplementary Information (Supplementary Table S1).

Echocardiographic measurements

Complete two-dimensional transthoracic echocardiograms were performed during the index hospitalization. Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), volumetric parameters, and linear dimensions were assessed in accordance with the guidelines of the American Society of Echocardiography (ASE) (15). Quantified echocardiographic measures included left ventricular (LV) mass, LVEF, left ventricular end-diastolic (LVED) volume, left atrial (LA) volume, and left atrial volume index (LAVI) (Table 1). LV and LA volumes were derived using the Simpson's biplane method of disks from apical 2- and 4-chamber views. LV mass was calculated using the ASE-recommended formula: LV mass = 0.8 × [1.04 × (LVID + PWTd + SWTd)3—LVID3] + 0.6 g, where LVID is the LV internal diameter in diastole, PWTd is the posterior wall thickness in diastole, and SWTd is the septal wall thickness in diastole (15).

Table 1.

Characteristics of TRACE-CORE participants included in the analytic sample.

| Characteristics | No AF (N = 250) | AF (N = 46) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean SD | 62.1 (11.5) | 69.9 (10.0) | <0.001 |

| Female | 33.6 | 28.3 | 0.47 |

| Race (Caucasian) | 96.4 | 97.8 | 0.03 |

| Height (inches) | 67.9 (8.2) | 75.4 (27.4) | 0.0004 |

| Weight (lbs) | 188.1 (46.9) | 183.6 (51.9) | 0.59 |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | 29.4 (5.5) | 29.2 (5.8) | 0.84 |

| Social History | |||

| Education | |||

| High school | 39.2 | 45.7 | |

| Some college | 28 | 23.9 | 0.7 |

| College | 32.8 | 30.4 | |

| Married | 66.00 | 67.4 | 0.85 |

| Risk Factors | |||

| Hyperlipidemia | 67.6 | 71.7 | 0.58 |

| Myocardial Infarction | 28.8 | 34.8 | 0.42 |

| Anginal Pectoris/CHD | 26.00 | 37.00 | 0.14 |

| Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus | 28.8 | 28.3 | 0.94 |

| Stroke/TIA | 1.2 | 6.5 | 0.05 |

| CHF | 8.8 | 19.6 | 0.04 |

| Hypertension | 67.6 | 84.8 | 0.01 |

| Seattle Angina Questionnaire | |||

| Physical limitation | 83.2 (22.0) | 69.0 (27.6) | 0.03 |

| Angina stability | 43.7 (40.3) | 38.0 (23.5) | 0.44 |

| Angina frequency | 75.4 (23.1) | 67.7 (28.5) | 0.19 |

| Treatment satisfaction | 93.9 (11.2) | 93.0 (13.7) | 0.77 |

| Quality of life | 64.8 (25.5) | 54.8 (31.1) | 0.12 |

| Admission Medications | |||

| Aspirin | 46.0 | 63.0 | 0.03 |

| Beta Blocker | 38.4 | 69.6 | <0.001 |

| ACEI or ARB | 36.8 | 56.5 | 0.01 |

| Statin | 54.8 | 80.4 | 0.0007 |

| Plavix | 13.6 | 15.2 | 0.77 |

| Coumadin | 2.00 | 30.4 | <0.001 |

| Physical Activity | |||

| No physical acitivity | 58.5 | 73.9 | |

| <150 min/wk | 15.5 | 15.2 | 0.05 |

| >150 min/wk | 26.00 | 10.9 | |

| Acute Coronary Syndrome Category | |||

| ST-elevation myocardial infarction | 26.8 | 19.6 | 0.29 |

| Physiological Factors | |||

| Heart rate (beats per minute) | 77.9 (19.4) | 86.0 (31.2) | 0.09 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 141.3 (25.1) | 132.3 (23.2) | 0.02 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 79.5 (16.7) | 75.1 (14.8) | 0.07 |

| Respiratory rate (breaths per minute) | 18.1 (4.1) | 19.3 (4.5) | 0.11 |

| Electrocardiogram | |||

| QRS duration | 96.7 (21.0) | 100.2 (25.3) | 0.39 |

| PR interval | 164.4 (26.9) | 175.4 (47.3) | 0.23 |

| Lab Values | |||

| Troponin peak | 23.6 (35.9) | 24.9 (34.7) | 0.87 |

| Total cholesterol | 174.9 (46.5) | 140.0 (39.5) | 0.003 |

| Brain natriuretic peptide | 620.7 (853.2) | 623.8 (428.7) | 0.99 |

| Creatinine | 1.2 (0.51) | 1.3 (0.55) | 0.08 |

| Hemoglobin | 11.9 (2.15) | 10.2 (2.27) | <0.001 |

| Sodium | 135.9 (3.3) | 134.7 (3.6) | 0.03 |

| Echocardiographic Phenotype* | |||

| LV Ejection Fraction | 53.0 (12.7) | 52.0 (12.2) | 0.74 |

| LA Volume | 46.6 (17.7) | 50.4 (30.3) | 0.58 |

| LAVI = LAVavg/BSA | 23.7 (8.3) | 24.3 (12.9) | 0.82 |

| LVIDd | 4.8 (0.76) | 4.7 (0.71) | 0.58 |

| LVIDs | 3.39 (0.87) | 3.41 (0.80) | 0.94 |

| GLS (−) | (−)13.4 (4.0) | (−)11.8 (4.1) | 0.12 |

| FSmmw | 0.17 (0.06) | 0.16 (0.03) | 0.26 |

| Fsen | 0.32 (0.15) | 0.29 (0.09) | 0.16 |

Echocardiographic phenotypes were characterized in subset of patients (N = 143) where TTE were available.

CHD, coronary heart disease; TIA, transient ischemic attack; ACEi, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blockers; LV, left ventricle; LA, left atrium; LAVI, left atrial volume index; LAVavg/BSA, average left atrial volume/body surface area.

Statistical analyses

A two-step analysis model was used to leverage echocardiographic phenotypes to identify candidate ex-RNAs and then examining ex-RNAs identified and prevalent AF. In step 1, we examined the relations between ex-RNAs with one or more echocardiographic phenotypes (Table 2, Supplementary Table S2). In step 2, we examined the associations of ex-RNAs identified from step 1 with prevalent AF (Table 3). Given the modest sample size of our study, we did not adjust for age or other covariates. Of note, the number of participants in each step differed as we did not have echocardiographic data available for all participants with plasma ex-RNA data. There are 143 cases with both ex-RNA and echocardiographic data in our TRACE-CORE cohort (Figure 1). We used this group to determine the ex-RNAs significantly related to one or more echo parameters. Using this significant list of ex-RNAs, we queried for a relationship with prevalent AF on the full 296 cases with ex-RNA data.

Table 2.

ex-RNAs associated with echocardiographic phenotypes.

| ex-RNA | No AF (N = 250) | AF (N = 46) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean (1/Cq) | Median (1/Cq) | Std Dev | N | Mean (1/Cq) | Median (1/Cq) | Std Dev | |

| hsa_miR_1_3p | 78 | 0.0532116 | 0.0492086 | 0.021974 | 14 | 0.0486145 | 0.0485775 | 0.0021635 |

| hsa_miR_10a_5p | 74 | 0.0544765 | 0.0490171 | 0.026744 | 9 | 0.0479115 | 0.0471863 | 0.0020413 |

| hsa_miR_10b_5p | 105 | 0.0526464 | 0.0519433 | 0.005696 | 19 | 0.054176 | 0.0525778 | 0.008361 |

| hsa_miR_1185_1_3p | 10 | 0.076133 | 0.048098 | 0.077952 | 4 | 0.0811416 | 0.0646895 | 0.0489224 |

| hsa_miR_1229_3p | 87 | 0.0527826 | 0.0490296 | 0.023452 | 17 | 0.0496961 | 0.0494903 | 0.0030281 |

| hsa_miR_1246 | 248 | 0.0697233 | 0.0689199 | 0.007744 | 46 | 0.0706521 | 0.0691848 | 0.0075221 |

| hsa_miR_1247_5p | 193 | 0.0530236 | 0.0512006 | 0.014657 | 30 | 0.0520521 | 0.0507146 | 0.0057972 |

| hsa_miR_1271_5p | 6 | 0.0711808 | 0.0462112 | 0.056029 | 3 | 0.1112173 | 0.0686812 | 0.0941748 |

| hsa_miR_128_3p | 102 | 0.0528408 | 0.0498578 | 0.020063 | 16 | 0.04953 | 0.0505303 | 0.0022436 |

| hsa_miR_1307_3p | 79 | 0.052133 | 0.0489367 | 0.01868 | 15 | 0.0487416 | 0.0481839 | 0.0027178 |

| hsa_miR_139_5p | 172 | 0.0509962 | 0.0504476 | 0.003436 | 31 | 0.0502585 | 0.0498191 | 0.0024643 |

| hsa_miR_144_5p | 91 | 0.0538011 | 0.0498353 | 0.034404 | 11 | 0.0504393 | 0.0503199 | 0.0020809 |

| hsa_miR_152_3p | 109 | 0.0546243 | 0.053788 | 0.015778 | 21 | 0.0531483 | 0.0531467 | 0.0048266 |

| hsa_miR_17_3p | 34 | 0.0581639 | 0.048011 | 0.048989 | 8 | 0.048671 | 0.0487127 | 0.0021114 |

| hsa_miR_17_5p | 174 | 0.0526555 | 0.0520309 | 0.00485 | 33 | 0.051199 | 0.0505799 | 0.0036006 |

| hsa_miR_181c_3p | 134 | 0.0496425 | 0.0493075 | 0.004581 | 19 | 0.0496737 | 0.0492549 | 0.0022402 |

| hsa_miR_185_3p | 12 | 0.0807253 | 0.0469793 | 0.078499 | 1 | 0.0467564 | 0.0467564 | . |

| hsa_miR_186_5p | 99 | 0.0496918 | 0.0492638 | 0.002817 | 23 | 0.0485152 | 0.0487082 | 0.0017551 |

| hsa_miR_190a_3p | 25 | 0.0559995 | 0.0481922 | 0.028327 | 5 | 0.0486872 | 0.0493391 | 0.0016668 |

| hsa_miR_193b_3p | 17 | 0.0474027 | 0.046771 | 0.002504 | 1 | 0.0494669 | 0.0494669 | . |

| hsa_miR_194_5p | 80 | 0.0514792 | 0.0489358 | 0.013029 | 13 | 0.0602008 | 0.0477006 | 0.0434223 |

| hsa_miR_200b_3p | 36 | 0.056391 | 0.0477348 | 0.028669 | 8 | 0.0535471 | 0.0482227 | 0.0116097 |

| hsa_miR_200c_3p | 28 | 0.0487998 | 0.0477602 | 0.003904 | 3 | 0.1384421 | 0.0479771 | 0.1585388 |

| hsa_miR_210_3p | 60 | 0.0482735 | 0.0479058 | 0.002153 | 9 | 0.0485037 | 0.0484956 | 0.0019539 |

| hsa_miR_2110 | 66 | 0.049364 | 0.0483657 | 0.007079 | 6 | 0.0477354 | 0.0471473 | 0.0024344 |

| hsa_miR_215_5p | 48 | 0.0611305 | 0.0487926 | 0.067106 | 6 | 0.0524814 | 0.0511999 | 0.0057445 |

| hsa_miR_22_3p | 194 | 0.052095 | 0.0517429 | 0.003923 | 35 | 0.0524587 | 0.0512132 | 0.0065555 |

| hsa_miR_22_5p | 58 | 0.0507662 | 0.0482315 | 0.007676 | 11 | 0.0537059 | 0.0484255 | 0.0141602 |

| hsa_miR_224_5p | 88 | 0.0490206 | 0.0483175 | 0.002941 | 10 | 0.0501532 | 0.0494765 | 0.0031774 |

| hsa_miR_296_5p | 119 | 0.0607483 | 0.0636846 | 0.01262 | 23 | 0.0623518 | 0.0669331 | 0.0114245 |

| hsa_miR_29a_3p | 186 | 0.0542824 | 0.0527513 | 0.009596 | 32 | 0.0643896 | 0.0526593 | 0.061423 |

| hsa_miR_29b_3p | 100 | 0.0497822 | 0.0492949 | 0.002587 | 11 | 0.0619879 | 0.0482569 | 0.0456338 |

| hsa_miR_29c_3p | 145 | 0.051691 | 0.0511776 | 0.003584 | 27 | 0.050784 | 0.0504793 | 0.0028985 |

| hsa_miR_29c_5p | 247 | 0.0586745 | 0.0605409 | 0.005869 | 46 | 0.0585694 | 0.0597602 | 0.0055613 |

| hsa_miR_301b_3p | 34 | 0.0570262 | 0.0489981 | 0.021454 | 8 | 0.0505417 | 0.0460105 | 0.0115485 |

| hsa_miR_30b_5p | 104 | 0.0524204 | 0.049863 | 0.013113 | 19 | 0.0518143 | 0.0490891 | 0.0078867 |

| hsa_miR_30c_5p | 158 | 0.0536866 | 0.050752 | 0.028003 | 31 | 0.0506949 | 0.049967 | 0.0029418 |

| hsa_miR_320d | 34 | 0.0474423 | 0.0467811 | 0.001899 | 7 | 0.0475848 | 0.0474307 | 0.0014531 |

| hsa_miR_324_3p | 195 | 0.0518799 | 0.052044 | 0.003289 | 39 | 0.0509503 | 0.0515589 | 0.0032071 |

| hsa_miR_331_3p | 76 | 0.0581103 | 0.0590573 | 0.00509 | 15 | 0.057876 | 0.0590844 | 0.0039275 |

| hsa_miR_337_3p | 49 | 0.0544614 | 0.049184 | 0.022267 | 6 | 0.0501628 | 0.0496202 | 0.0020578 |

| hsa_miR_342_5p | 26 | 0.0540327 | 0.0477244 | 0.031145 | 3 | 0.0458949 | 0.0457851 | 0.0003425 |

| hsa_miR_34a_3p | 42 | 0.0481224 | 0.0475388 | 0.003913 | 7 | 0.0478629 | 0.04801 | 0.0017482 |

| hsa_miR_3615 | 159 | 0.0502273 | 0.0493263 | 0.009675 | 27 | 0.048445 | 0.0482488 | 0.0018838 |

| hsa_miR_378a_3p | 142 | 0.0518858 | 0.0506277 | 0.013493 | 25 | 0.0503217 | 0.0495978 | 0.0044944 |

| hsa_miR_381_3p | 6 | 0.055495 | 0.0521887 | 0.012588 | 2 | 0.0531945 | 0.0531945 | 0.0033558 |

| hsa_miR_425_5p | 65 | 0.0518003 | 0.0493772 | 0.009402 | 9 | 0.0484625 | 0.0477814 | 0.0020986 |

| hsa_miR_4446_3p | 238 | 0.0574881 | 0.0596986 | 0.006702 | 44 | 0.0572826 | 0.0593641 | 0.0066937 |

| hsa_miR_450b_5p | 37 | 0.0590072 | 0.0480829 | 0.035178 | 4 | 0.0836709 | 0.0504592 | 0.0687618 |

| hsa_miR_454_3p | 48 | 0.0607224 | 0.0486327 | 0.035194 | 6 | 0.0496523 | 0.0488364 | 0.003395 |

| hsa_miR_4770 | 28 | 0.0724879 | 0.0492878 | 0.04995 | 10 | 0.0641504 | 0.0490861 | 0.0419758 |

| hsa_miR_483_3p | 33 | 0.0612955 | 0.0470936 | 0.044739 | 6 | 0.0487458 | 0.0488686 | 0.00068702 |

| hsa_miR_497_5p | 62 | 0.0507918 | 0.048863 | 0.008547 | 7 | 0.0502849 | 0.0504037 | 0.002183 |

| hsa_miR_502_3p | 35 | 0.0505644 | 0.0478932 | 0.013581 | 3 | 0.0465949 | 0.0467552 | 0.00060646 |

| hsa_miR_532_3p | 192 | 0.052351 | 0.0502476 | 0.005461 | 33 | 0.0539177 | 0.0530617 | 0.0070026 |

| hsa_miR_532_5p | 38 | 0.0523519 | 0.0475867 | 0.017305 | 3 | 0.1580497 | 0.1890047 | 0.0857976 |

| hsa_miR_545_5p | 9 | 0.0822204 | 0.0489364 | 0.07149 | 3 | 0.093437 | 0.1052632 | 0.0404737 |

| hsa_miR_548d_3p | 25 | 0.0477521 | 0.0475845 | 0.00138 | 9 | 0.0468183 | 0.046468 | 0.0010111 |

| hsa_miR_548e_3p | 16 | 0.10365 | 0.0483893 | 0.118834 | 3 | 0.0794202 | 0.0669776 | 0.041042 |

| hsa_miR_550a_3p | 6 | 0.0882057 | 0.0489723 | 0.096385 | 1 | 0.0460695 | 0.0460695 | . |

| hsa_miR_574_3p | 89 | 0.0519335 | 0.049021 | 0.017758 | 19 | 0.0488315 | 0.0484904 | 0.0026017 |

| hsa_miR_582_3p | 12 | 0.0733303 | 0.0561478 | 0.04628 | 1 | 0.0614546 | 0.0614546 | . |

| hsa_miR_584_5p | 153 | 0.0535996 | 0.0504307 | 0.028997 | 28 | 0.0505161 | 0.0509117 | 0.0026293 |

| hsa_miR_590_3p | 19 | 0.0490983 | 0.0483512 | 0.002403 | 1 | 0.0726819 | 0.0726819 | . |

| hsa_miR_590_5p | 25 | 0.0727524 | 0.0493378 | 0.062432 | 3 | 0.1036606 | 0.1119633 | 0.0543337 |

| hsa_miR_642a_5p | 15 | 0.1042246 | 0.0928847 | 0.091516 | 2 | 0.0912716 | 0.0912716 | 0.0482923 |

| hsa_miR_654_3p | 31 | 0.0853935 | 0.0548196 | 0.06543 | 4 | 0.0599797 | 0.0572262 | 0.0140572 |

| hsa_miR_654_5p | 24 | 0.0481984 | 0.0477808 | 0.002624 | 2 | 0.0491084 | 0.0491084 | 0.00107 |

| hsa_miR_659_3p | 45 | 0.0474394 | 0.0475009 | 0.001371 | 7 | 0.0472299 | 0.0474096 | 0.00044278 |

| hsa_miR_660_5p | 91 | 0.0524652 | 0.0491282 | 0.020054 | 16 | 0.0497289 | 0.0488174 | 0.0025629 |

| hsa_miR_664a_5p | 34 | 0.0530387 | 0.0468396 | 0.031089 | 4 | 0.0481101 | 0.0479805 | 0.0019548 |

| hsa_miR_6803_3p | 38 | 0.0492133 | 0.047891 | 0.007958 | 8 | 0.0808498 | 0.0494892 | 0.0907363 |

| hsa_miR_7977 | 50 | 0.048617 | 0.0483476 | 0.001892 | 5 | 0.0480875 | 0.048202 | 0.0017095 |

| hsa_miR_877_3p | 66 | 0.0532129 | 0.0504439 | 0.015183 | 15 | 0.050662 | 0.050671 | 0.0025874 |

| hsa_miR_885_5p | 65 | 0.0546778 | 0.0486122 | 0.022415 | 10 | 0.0483796 | 0.0479623 | 0.0018983 |

| hsa_miR_9_3p | 74 | 0.0513739 | 0.0497939 | 0.006949 | 12 | 0.0520303 | 0.0518041 | 0.0039796 |

| hsa_miR_99a_5p | 192 | 0.0549907 | 0.0558302 | 0.004637 | 33 | 0.0552821 | 0.0562075 | 0.0046839 |

Table 3.

miRNAs significantly related to history of AF.

| miRNA | n | mean | std | Estimate | StdErr | ProbChiSq | OddsRatioEst | LowerCL | UpperCL | Raw P-value | FDR P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hsa_miR_106b_5p | 171 | 19.6432 | 1.426 | 0.5328 | 0.2517 | 0.0343 | 1.704 | 1.04 | 2.79 | 0.0343 | 0.0395 |

| hsa_miR_125b_5p | 126 | 20.0642 | 1.00202 | 1.0726 | 0.4102 | 0.0089 | 2.923 | 1.308 | 6.53 | 0.0089 | 0.0343 |

| hsa_miR_142_3p | 81 | 19.5754 | 3.04565 | 1.6648 | 0.8318 | 0.0454 | 5.285 | 1.035 | 26.982 | 0.0454 | 0.0454 |

| hsa_miR_150_5p | 269 | 16.2008 | 2.00911 | 0.2283 | 0.0993 | 0.0214 | 1.256 | 1.034 | 1.526 | 0.0214 | 0.0343 |

| hsa_miR_15b_3p | 175 | 19.4343 | 1.57645 | 0.6897 | 0.2322 | 0.003 | 1.993 | 1.264 | 3.142 | 0.003 | 0.0343 |

| hsa_miR_17_5p | 207 | 19.2059 | 1.49941 | 0.4549 | 0.1828 | 0.0128 | 1.576 | 1.101 | 2.255 | 0.0128 | 0.0343 |

| hsa_miR_20b_5p | 199 | 18.5883 | 2.30551 | 0.482 | 0.2119 | 0.0229 | 1.619 | 1.069 | 2.453 | 0.0229 | 0.0343 |

| hsa_miR_23b_3p | 186 | 19.5649 | 1.5271 | 0.5582 | 0.2394 | 0.0197 | 1.748 | 1.093 | 2.794 | 0.0197 | 0.0343 |

| hsa_miR_3613_3p | 243 | 18.4669 | 1.6719 | 0.3741 | 0.144 | 0.0094 | 1.454 | 1.096 | 1.928 | 0.0094 | 0.0343 |

| hsa_miR_362_3p | 27 | 18.5678 | 4.59545 | −0.3338 | 0.1403 | 0.0174 | 0.716 | 0.544 | 0.943 | 0.0174 | 0.0343 |

| hsa_miR_433_3p | 220 | 19.3035 | 2.34432 | −0.1656 | 0.0752 | 0.0276 | 0.847 | 0.731 | 0.982 | 0.0276 | 0.0376 |

| hsa_miR_495_3p | 115 | 19.7469 | 1.49644 | 0.9642 | 0.3822 | 0.0116 | 2.623 | 1.24 | 5.547 | 0.0116 | 0.0343 |

| hsa_miR_574_3p | 108 | 20.0059 | 1.99826 | 0.773 | 0.3771 | 0.0404 | 2.166 | 1.034 | 4.536 | 0.0404 | 0.0433 |

| hsa_miR_6511b_3p | 138 | 20.3203 | 1.113 | 0.7134 | 0.337 | 0.0343 | 2.041 | 1.054 | 3.951 | 0.0343 | 0.0395 |

| hsa_miR_942_5p | 84 | 20.4355 | 1.65312 | −0.5972 | 0.2437 | 0.0143 | 0.55 | 0.341 | 0.887 | 0.0143 | 0.0343 |

Bolded miRNA are also associated with echophenotypes.

For step 1 of our analyses, we used ordinary least-squares linear regression to quantify associations between ex-RNA levels and one or more echocardiographic phenotypes in all participants. To account for multiple testing, we employed Bonferroni correction to establish a more restrictive threshold for defining statistical significance. We established a 5% false-discovery rate (via the Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate approach) to screen associations between ex-RNAs and one or more echocardiographic phenotypes. The α for achieving significance was set at 0.05/340 = 0.000147 a priori. Note that Cq represents a log measure of concentration, with exponentiation factor 2. In step 2 of the analysis, we examined the associations of miRNAs identified from step 1, with prevalent AF using a logistic regression model. Here, the continuous 1/Cq values, which corresponded to plasma miRNA levels, were compared with prevalent AF (Table 3).

Differentially expressed miRNAs were analyzed using miRDB, an online database that captures miRNA and gene target interactions (16, 17). The network and functional analyses were generated through the use Qiagen's Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) version 24.0.2 (18). All statistics were performed with SAS software version 9.3 (SAS Institute) with a 2-tailed P value < 0.05 as significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

The baseline demographic, clinical, and echocardiographic characteristics of the 296 study participants are outlined in Table 1. Study participants were middle aged to older adults (mean age of 62 ± 11 and 70 ± 10 for the no AF [control group] vs. the AF group, respectively). There was a male predominance; women represented 33% and 28% of control and AF groups, respectively. The patients with AF had a significant higher history of transient ischemic attacks, strokes, congestive heart failure and hypertension (Table 1). There are nonsignificant trends of higher LA volume (46.6 vs. 50.4 ml) and lower global longitudinal strains (−13.4% vs. 11.1%) in patients with AF as compared to those without (Table 1). However, we did not find any significant trends in in echo parameters associated with and without AF.

Association of ex-RNAs with echocardiographic phenotypes and AF

A total of 318 ex-RNAs were quantified in the plasma of TRACE-CORE participants included in our investigation. There were 77 ex-RNAs that associated with one or more echocardiographic parameters, independent of other clinical variables (Table 2). Five miRNAs were associated with three or more echocardiographic traits, miR-10a-5p, miR-10b-5p, miR-190a-3p, miR-425-5p, and miR-574-3p (Supplementary Table S2). Of the 77 ex-RNA that were significantly associated echo-phenotypes, miR-17-5p and miR-574-3p were also significantly associated with a history of AF, with odds ratios of 1.58 (95% CI: 1.10–2.26) and 2.16 (95% CI: 1.03–4.54), respectively (Table 3). We found fifteen ex-RNAs that associated with prevalent AF via unadjusted logistic regression modeling (Table 3).

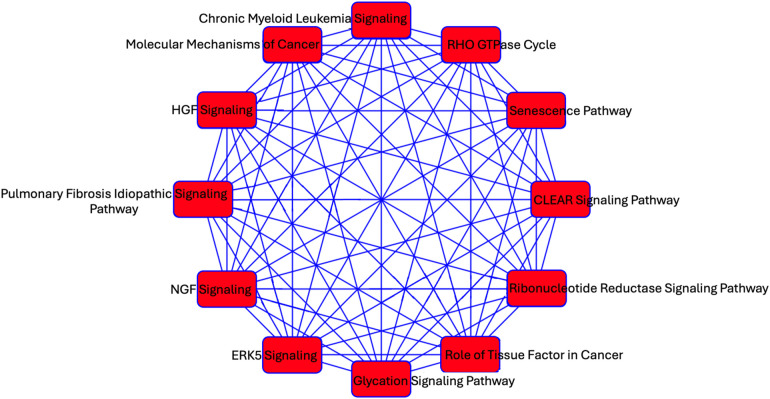

Gene targets of ex-RNAs associated with prevalent AF

We investigated predicted targets of the two miRNAs associated with echocardiographic phenotypes and prevalent AF using the database miRDB. From this, 1,355 genes were predicted as targets for at least one miRNA. As miRNA are known to act in concert, we used the combined targets of miR-17-5p and miR-574-3p to perform further analysis in IPA (2). Overlapping canonical pathways were mapped to allow for visualization of the shared biological pathways through the common genes (Figure 2). The resulting network revealed significant enrichment of interconnected canonical pathways, including the Senescence Pathway, Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Signaling Pathway, RHO GTPase Cycle, ERK5 Signaling, HGF Signaling, NGF Signaling, CLEAR Signaling Pathway, Glycation Signaling Pathway, Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Signaling, Molecular Mechanisms of Cancer, and Role of Tissue Factor in Cancer.

Figure 2.

A network analysis of predicted targets of miR-17-5p and miR-574-3p as performed by IPA. Each node represents a unique pathway, and edges denote shared gene components between pathways. The pathways include those implicated in fibrosis (Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Signaling Pathway), cellular stress responses (ERK5 Signaling, RHO GTPase signaling, Senescence Pathway), cancer (e.g., Molecular Mechanisms of Cancer, Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Signaling), and metabolic regulation (Glycation Signaling Pathway).

Discussion

In our investigation of ex-RNA profiles of 296 hospitalized ACS survivors in the TRACE-CORE Cohort, we identified 77 plasma ex-RNAs associated with one or more echocardiographic traits. Furthermore, two of these ex-RNAs, miR-17-5p and miR-574-3p, were associated with prevalent AF. While the association of miRNA and AF has been explored previously, our study uniquely examined the association between ex-RNA and AF in the acute clinical setting. We identified miR-17-5p and miR-574-3p as regulators in cardiac remodeling and AF in patients hospitalized for ACS.

Echocardiographic phenotypes and cardiac remodeling in AF

AF is intimately linked with structural and functional remodeling of the heart, particularly involving the left atrium and ventricle. Among the echocardiographic parameters that reflect these changes, the left atrial volume index (LAVI) and global longitudinal strain (GLS) are particularly sensitive indicators of remodeling. In the presented data, there is a slight but consistent trend toward increased LAVI in the AF group, suggesting chronic atrial pressure or volume overload. While this subtle enlargement may not reach statistical significance, it likely reflects early or sustained atrial remodeling associated with AF pathophysiology. Elevated LAVI has been associated with increased atrial stiffness and fibrosis, both of which are known contributors to the maintenance and recurrence of AF (19, 20).

Simultaneously, a downward trend in GLS values in the AF group indicates early LV systolic dysfunction despite preserved ejection fraction. GLS, which captures longitudinal myocardial deformation, is a more sensitive marker of subclinical ventricular dysfunction than traditional metrics like LVEF. Reduced GLS in AF patients, even in the absence of overt systolic impairment, underscores the subtle mechanical changes that accompany electrical abnormalities in this arrhythmia (21). These findings suggest that the combination of mild increases in LAVI and early reductions in GLS may serve as echocardiographic markers of the atrial and ventricular remodeling continuum seen in AF (11).

Association of ex-RNAs, cardiac remodeling and AF

Several canonical pathways enriched among the predicted targets of miR-17-5p and miR-574-3p converge on well-established mechanisms of atrial remodeling. The Senescence Pathway and Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (IPF) Signaling Pathway are central to fibrotic transformation and extracellular matrix accumulation, processes that underlie the adverse structural substrate. Senescent fibroblasts and cardiomyocytes can adopt a pro-inflammatory secretory phenotype, amplifying fibrotic signaling and promoting atrial electrical inhomogeneity (22, 23). Similarly, the ERK5 and RHO GTPase signaling pathways are activated in response to mechanical stress and oxidative injury—conditions prevalent in the atria of patients with elevated atrial pressure or volume overload—and are implicated in cytoskeletal reorganization, endothelial dysfunction, and atrial dilation (24, 25). Furthermore, dysregulation of the Hepatocyte Growth Factor (HGF) Signaling Pathway, while generally cardioprotective, may lead to increased vulnerability to AF (26).

In addition, NGF signaling plays a key role in autonomic remodeling, a known contributor to AF initiation and maintenance. Elevated NGF levels in atrial tissue have been associated with sympathetic hyperinnervation and parasympathetic imbalance, both of which shorten atrial refractoriness and promote arrhythmogenicity (27). Interestingly, the enrichment of cancer-associated pathways such as Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Signaling, Molecular Mechanisms of Cancer, and Role of Tissue Factor in Cancer may reflect shared transcriptional programs between fibrotic and proliferative remodeling in AF and oncogenic processes (28, 29). Together, the convergence of these pathways suggests a multifactorial molecular basis for AF, in which structural, autonomic innervation, and inflammatory mechanisms intersect.

Emerging evidence suggests that miR-17-5p and miR-574-3p play a role in the pathogenesis of AF. miR-17-5p is part of the miR-17-92 cluster, which has been shown to regulate genes involved in sinoatrial node development and pacemaker activity (30). Specifically, miR-17-92 represses genes such as Shox2 and Tbx3, which are crucial for sinoatrial node formation. Deficiency of miR-17-92 leads to increased susceptibility to pacing-induced AF and sinoatrial node dysfunction—both recognized as risk factors for AF in humans (30). Similarly, miR-574-3p has been shown to be elevated in the left atrial appendages of patients with persistent AF secondary to mitral stenosis, compared to those in normal sinus rhythm, suggesting its involvement in adverse structural remodeling (31).

Strength and limitations

This study has several strengths. We analyzed associations between circulating ex-RNAs and both echocardiographic phenotypes and AF in a well-characterized cohort of patients hospitalized with ACS as part of the TRACE-CORE study. This cohort uniquely enabled the profiling of plasma ex-RNA expression in the acute clinical setting. While it is conceivable that the observed ex-RNA signatures may be influenced by the acute ischemic event rather than AF, our prior work did not identify significant ex-RNA differences attributable to acute myocardial infarction (32). Given that we employed a similar analytic method in the current study, the differential ex-RNA expression is more plausibly attributed to AF status rather than ACS event.

Several limitations should be acknowledged. The relatively small sample size and limited racial and geographic diversity may constrain the generalizability of our findings. Moreover, while we identified several microRNAs associated with echocardiographic parameters and AF, the cellular origin and biological mechanisms underlying their release into the circulation remain undefined. In addition, AF subtypes were not systematically recorded and could not be assessed in this analysis. Due to the modest sample size of our study, we did not adjust for age or other covariates, which limits our ability to evaluate independent associations between ex-RNA expression and AF. Future studies incorporating mechanistic investigations, including cellular and molecular approaches, as well as multivariable models to account for potential confounders such as age are needed to elucidate the functional roles of these miRNAs in AF pathogenesis.

Conclusion

In this study of hospitalized ACS survivors, we identified circulating ex-RNAs, including miR-17-5p and miR-574-3p, that are associated with echocardiographic markers of cardiac remodeling and with prevalent atrial fibrillation. These miRNAs target gene networks involved in fibrosis, senescence, cytoskeletal remodeling, and autonomic signaling—pathways central to the structural and electrical substrate of AF. Our findings suggest that plasma ex-RNAs may serve as informative biomarkers of atrial remodeling and AF risk, particularly in the acute clinical setting. By linking molecular signatures with imaging phenotypes, this study provides a foundation for further investigation into the mechanistic roles of ex-RNAs in AF pathogenesis and their potential utility in risk stratification and therapeutic targeting.

Funding Statement

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by U01HL105268 (CK), K23HL161432 (KVT) and R01HL126911, R01HL137734, R01HL137794, R01HL135219, R01HL136660, U54HL143541, and 1U01HL146382 to DDM from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by UMass Chan Medical School Institutional Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

KT: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Visualization, Validation, Investigation. DL: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. CK: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Resources, Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft. JF: Investigation, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Resources, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Supervision, Validation. MP: Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Writing – original draft. GA: Methodology, Investigation, Resources, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. KD: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. DM: Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Project administration, Supervision, Data curation, Investigation, Resources, Software, Conceptualization, Visualization, Funding acquisition, Validation. KT: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Supervision, Data curation, Investigation, Software, Conceptualization, Resources, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Validation, Visualization.

Conflict of interest

DM has received consultancy fees from Heart Rhythm Society, Fitbit, Flexcon, Pfizer, Avania, NAMSA, and Bristol Myers Squibb. DM reports receiving research support from Fitbit, Apple, Care Evolution, Boeringher Ingelheim, Pfizer, and Bristol Myers Squibb. KT has research support for Novartis.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcvm.2025.1623112/full#supplementary-material

References

- 1.Benjamin EJ, Muntner P, Alonso A, Bittencourt MS, Callaway CW, Carson AP, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2019 update: a report from the American heart association. Circulation. (2019) 139(10):e56–e528. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartel DP. Metazoan MicroRNAs. Cell. (2018) 173(1):20–51. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.03.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McManus DD, Ambros V. Circulating MicroRNAs in cardiovascular disease. Circulation. (2011) 124(18):1908–10. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.062117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freedman JE, Gerstein M, Mick E, Rozowsky J, Levy D, Kitchen R, et al. Diverse human extracellular RNAs are widely detected in human plasma. Nat Commun. (2016) 7:11106. 10.1038/ncomms11106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wiedmann F, Kraft M, Kallenberger S, Büscher A, Paasche A, Blochberger PL, et al. MicroRNAs regulate TASK-1 and are linked to myocardial dilatation in atrial fibrillation. J Am Heart Assoc. (2022) 11(7):e023472. 10.1161/JAHA.121.023472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McManus DD, Tanriverdi K, Lin H, Esa N, Kinno M, Mandapati D, et al. Plasma microRNAs are associated with atrial fibrillation and change after catheter ablation (the miRhythm study). Heart Rhythm. (2015) 12(1):3–10. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2014.09.050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wei F, Ren W, Zhang X, Wu P, Fan J. miR-425-5p is negatively associated with atrial fibrosis and promotes atrial remodeling by targeting CREB1 in atrial fibrillation. J Cardiol. (2022) 79(2):202–10. 10.1016/j.jjcc.2021.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prastaro M, D’Amore C, Paolillo S, Losi M, Marciano C, Perrino C, et al. Prognostic role of transthoracic echocardiography in patients affected by heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. Heart Fail Rev. (2015) 20(3):305–16. 10.1007/s10741-014-9461-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vaziri SM, Larson MG, Benjamin EJ, Levy D. Echocardiographic predictors of nonrheumatic atrial fibrillation. The framingham heart study. Circulation. (1994) 89(2):724–30. 10.1161/01.CIR.89.2.724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsang TSM, Barnes ME, Gersh BJ, Bailey KR, Seward JB. Left atrial volume as a morphophysiologic expression of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction and relation to cardiovascular risk burden. Am J Cardiol. (2002) 90(12):1284–9. 10.1016/S0002-9149(02)02864-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuppahally SS, Akoum N, Burgon NS, Badger TJ, Kholmovski EG, Vijayakumar S, et al. Left atrial strain and strain rate in patients with paroxysmal and persistent atrial fibrillation: relationship to left atrial structural remodeling detected by delayed-enhancement MRI. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. (2010) 3(3):231–9. 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.109.865683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Waring ME, McManus RH, Saczynski JS, Anatchkova MD, McManus DD, Devereaux RS, et al. Transitions, risks, and actions in coronary events–center for outcomes research and education (TRACE-CORE): design and rationale. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. (2012) 5(5):e44–50. 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.112.965418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McManus DD, Saczynski JS, Lessard D, Waring ME, Allison J, Parish DC, et al. Reliability of predicting early hospital readmission after discharge for an acute coronary syndrome using claims-based data. Am J Cardiol. (2016) 117(4):501–7. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.11.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McManus DD, Lin H, Tanriverdi K, Quercio M, Yin X, Larson MG, et al. Relations between circulating microRNAs and atrial fibrillation: data from the framingham offspring study. Heart Rhythm. (2014) 11(4):663–9. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2014.01.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lang RM, Badano LP, Mor-Avi V, Afilalo J, Armstrong A, Ernande L, et al. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: an update from the American society of echocardiography and the European association of cardiovascular imaging. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. (2015) 16(3):233–70. 10.1093/ehjci/jev014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wong N, Wang X. miRDB: an online resource for microRNA target prediction and functional annotations. Nucleic Acids Res. (2015) 43(Database issue):D146–52. 10.1093/nar/gku1104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang X. Improving microRNA target prediction by modeling with unambiguously identified microRNA-target pairs from CLIP-ligation studies. Bioinformatics. (2016) 32(9):1316–22. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krämer A, Green J, Pollard J, Tugendreich S. Causal analysis approaches in ingenuity pathway analysis. Bioinformatics. (2014) 30(4):523–30. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abhayaratna WP, Seward JB, Appleton CP, Douglas PS, Oh JK, Tajik AJ, et al. Left atrial size: physiologic determinants and clinical applications. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2006) 47(12):2357–63. 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.02.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mannina C, Ito K, Jin Z, Yoshida Y, Russo C, Nakanishi K, et al. Left atrial strain and incident atrial fibrillation in older adults. Am J Cardiol. (2023) 206:161–7. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2023.08.060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee H-H, Lee M-K, Lee W-H, Hsu P-C, Chu C-Y, Lee C-S, et al. Atrial fibrillation per se was a major determinant of global left ventricular longitudinal systolic strain. Medicine. (2016) 95(26):e4038. 10.1097/MD.0000000000004038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yan C, Xu Z, Huang W. Cellular senescence affects cardiac regeneration and repair in ischemic heart disease. Aging Dis. (2021) 12(2):552–69. 10.14336/AD.2020.0811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burstein B, Nattel S. Atrial fibrosis: mechanisms and clinical relevance in atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2008) 51(8):802–9. 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.09.064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schotten U, Verheule S, Kirchhof P, Goette A. Pathophysiological mechanisms of atrial fibrillation: a translational appraisal. Physiol Rev. (2011) 91(1):265–325. 10.1152/physrev.00031.2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Verma SK, Lal H, Golden HB, Gerilechaogetu F, Smith M, Guleria RS, et al. Rac1 and RhoA differentially regulate angiotensinogen gene expression in stretched cardiac fibroblasts. Cardiovasc Res. (2011) 90(1):88–96. 10.1093/cvr/cvq385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakamura T, Matsumoto K, Mizuno S, Sawa Y, Matsuda H, Nakamura T. Hepatocyte growth factor prevents tissue fibrosis, remodeling, and dysfunction in cardiomyopathic hamster hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. (2005) 288(5):H2131–9. 10.1152/ajpheart.01239.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen PS, Tan AY. Autonomic nerve activity and atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. (2007) 4(3):S61–4. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2006.12.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li J, Solus J, Chen Q, Rho YH, Milne G, Stein CM, et al. Role of inflammation and oxidative stress in atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. (2010) 7(4):438–44. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.12.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scott L, Jr., Li N, Dobrev D. Role of inflammatory signaling in atrial fibrillation. Int J Cardiol. (2019) 287:195–200. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.10.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang J, Bai Y, Li N, Ye W, Zhang M, Greene SB, et al. Pitx2-microRNA pathway that delimits sinoatrial node development and inhibits predisposition to atrial fibrillation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. (2014) 111(25):9181–6. 10.1073/pnas.1405411111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu H, Chen G-x, Liang M-y, Qin H, Rong J, Yao J-p, et al. Atrial fibrillation alters the microRNA expression profiles of the left atria of patients with mitral stenosis. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. (2014) 14:10. 10.1186/1471-2261-14-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mick E, Shah R, Tanriverdi K, Murthy V, Gerstein M, Rozowsky J, et al. Stroke and circulating extracellular RNAs. Stroke. (2017) 48(4):828–34. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.015140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.