Abstract

Post-catheter-ablation left atrial volume index (LAVI) and left atrial reverse remodeling (LARR) predict successful sinus rhythm maintenance in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF). Although the prognostic value of LAVI has been established in prior literature, few have directly compared the clinical significance of LAVI and LARR. This study compared the significance of the post-ablation LAVI and LARR for clinical events after catheter ablation in patients (n = 365; age 66 ± 9 years; men, 77%) with persistent AF who underwent their first catheter ablation. We calculated the LARR magnitude using the pre- and post-ablation LAVI. Post-ablation LAVI and LARR were divided into tertiles and compared the incidence of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE: all-cause death, unplanned heart failure hospitalization, and cardiovascular hospitalization) across tertiles. Over a median follow-up of 5.2 (interquartile range 3.1–7.0) years, 57 (16%) patients experienced at least one event. MACE incidence significantly increased across ascending post-ablation LAVI tertiles (cumulative incidence [95% confidence interval]: 1st [:<38 mL/m2], 8.4% [2.9–13.5] vs. 2nd [38–52 mL/m2], 11.6% [5.4–17.5] vs. 3rd [> 52 mL/m2], 21.7% [12.4–30.0], p < 0.001). However, MACE incidence was comparable across LARR tertiles (p = 0.900). Multivariate analysis identified post-ablation LAVI as an independent factor associated with post-ablation MACEs but not with post-ablation LARR. To conclude, the incidence of MACE increased significantly with the increase in post-ablation LAVI, but not with post-ablation LARR.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-13311-w.

Keywords: Atrial fibrillation, Heart failure, Catheter ablation, Reverse remodeling, Major adverse cardiovascular events

Subject terms: Cardiology, Cardiovascular diseases, Outcomes research

Introduction

In the current era of widespread oral anticoagulant use, heart failure (HF) has emerged as the predominant cause of death in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF)1,2. The incidence of HF is rapidly increasing owing to the aging population3. The prevalence of AF in patients with HF is high, affecting 30–50% of those with a reduced ejection fraction and 40–60% of those with a preserved ejection fraction4,5. Given the mutual interaction between AF and HF, managing both conditions simultaneously poses substantial challenges, regardless of whether they are the primary focus.

In patients with AF, left atrial enlargement is characteristic of structural remodeling and is recognized as a prognostic factor of poor outcomes6. Catheter ablation for AF is a feasible rhythm control option with high efficacy and safety7,8. This intervention also significantly reduced the left atrial volume (left atrial reverse remodeling [LARR]) by mitigating AF progression9. LARR can lead to favorable outcomes such as fewer arrhythmic recurrences, improved atrial function, and diminished atrial functional mitral regurgitation10–12. Hence, sufficient post-ablation LARR is often considered a key indicator for identifying ablation responders10,11.

Previous studies have suggested that the post-ablation left atrial volume index (LAVI), which can be interpreted as a consequence of LARR, may serve as a prognostic factor for patients who have undergone AF ablation12,13. Of note, we previously reported that patients with an initially enlarged pre-ablation LAVI could still experience a low risk of clinical events if they exhibited significant post-ablation LAVI reduction13. This finding underscored the limitations of using pre-ablation LAVI alone for risk stratification and led us to focus on post-ablation parameters—namely, LAVI and LARR—as potential prognostic markers. However, data specifically linking LARR to clinical outcomes remain scarce, and few studies have directly compared the prognostic value of post-ablation LAVI and LARR in this context. Therefore, we aimed to evaluate the prognostic significance of post-ablation LAVI and LARR for long-term major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) in patients with persistent AF who underwent catheter ablation.

Methods

Study outline

This retrospective, single-center cohort study adhered to the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Our institutional Ethics Committee (Institutional Review Boards of Yamaguchi University Hospital) approved the study, and our institutional Ethics Committee (Institutional Review Boards of Yamaguchi University Hospital) waived the requirement for informed consent due to the implementation of an opt-out system. Patient-level data are not publicly available as the Institutional Review Board (Institutional Review Board of Yamaguchi University Hospital) did not authorize their release. However, the data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Study design

We retrospectively analyzed the data of consecutive patients with persistent AF who underwent their first catheter ablation at our institution between January 2010 and June 2023, focusing on those with available LAVI measurements before and after ablation. Persistent AF was defined in accordance with current guidelines as episodes lasting > 7 days14. Post-ablation LAVI assessments were performed three months after the procedure, which was a timing that had been adopted in our prior studies and was consistent with the existing literature9,12.

We calculated the magnitude of the post-ablation LARR using pre- and post-ablation LAVI measurements. The entire cohort was stratified into three subgroups based on post-ablation LAVI and LARR tertiles. We compared the cumulative incidence of MACE following the procedure across tertiles.

Study endpoints

The primary endpoint was incidence of MACE after ablation. As defined in our previous studies13,15 MACE is a composite endpoint of all-cause death, HF hospitalization, and cardiovascular hospitalization. HF hospitalization was defined as an unplanned admission for the treatment of decompensated HF, whereas cardiovascular hospitalization was defined as an unexpected admission for the treatment of cardiovascular diseases other than HF. Events occurring within the blanking period (the first three months after the procedure) were excluded from the analysis.

Secondary endpoints included the following: (i) evaluation of the cumulative incidence of arrhythmic recurrence across tertiles; (ii) assessment of the relationship between post-ablation LAVI values and the post-ablation LARR; (iii) multivariate analysis to explore the significance of post-ablation LAVI and LARR on the risk of MACE development, adjusting for confounding factors.

Ablation procedure

In our initial procedural approach to persistent AF, we primarily employed pulmonary vein isolation using either radiofrequency or second-generation cryo-balloon energy, as previously described13,15. Targeted ablation was performed in patients with a clinically diagnosed or induced atrial flutter. Atrial substrate modification was not performed empirically unless there was a clear indication such as the presence of a complicated roof-dependent flutter.

Follow-up

At the 3-month follow-up, all patients underwent a comprehensive postprocedural assessment that included a 24-h Holter electrocardiogram and echocardiography. Subsequently, the patients were monitored at 6 and 12 months, with follow-up continuing at least annually for up to 5 years. Arrhythmic recurrence was defined as atrial tachyarrhythmia that persisted for > 30 s beyond the blanking period. In cases of atrial tachyarrhythmia recurrence, a repeat procedure was scheduled unless the patient declined to participate. Clinical event data were obtained from primary care physicians in August 2024.

Calculation of LAVI and LARR

The LAVI was calculated by integrating images acquired from the apical two- and four-chamber views. For patients with AF rhythm, images were captured from the index beat as previously described13. The post-ablation LARR was calculated using the following formula: ([post-ablation LAVI – pre-ablation LAVI] / pre-ablation LAVI × 100).

Statistical analysis

Normally distributed variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation, whereas non-normally distributed variables are presented as medians with interquartile ranges (IQR; 25th and 75th percentiles). Continuous variables across tertiles were compared using one-way analysis of variance. Categorical variables were compared using the chi-squared test.

The incidence of clinical events and arrhythmic recurrence is reported as the cumulative incidence with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) calculated at the median follow-up time using the Kaplan–Meier analysis. Differences in cumulative incidence among tertiles were assessed using the log-rank test.

To examine the relationship between post-ablation LAVI and LARR, we constructed a scatter plot and evaluated their correlation using Pearson’s correlation coefficient.

For multivariate analysis, we included factors relevant to long-term adverse events, particularly hospitalization for HF and all-cause death, as covariates. The results are presented as adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs. To visualize the relationship between post-ablation LAVI/LARR values and the risk of developing MACE, we constructed spline curves for each parameter. The number of knots for the spline curves was determined by optimizing the balance between the Akaike Information Criterion and parsimony.

Because our study population included patients who underwent post-ablation echocardiography for both AF rhythm (due to recurrence) and sinus rhythm, we conducted a sensitivity analysis to calculate the cumulative incidence of the primary outcome in patients who maintained sinus rhythm on post-ablation echocardiography.

Statistical analyses were conducted using R version 4.3.2, and the results were considered statistically significant at a p-value of < 0.05.

Results

Study population

A flow diagram depicting the study protocol is shown in Fig. 1. Of the 418 patients with persistent AF who underwent catheter ablation during the study period, data from 365 patients who underwent both pre- and post-ablation echocardiography were analyzed. The majority of procedures (80%) were performed from 2016 onwards. The tertiles of post-ablation LAVI were categorized as follows: 1st, < 38 mL/m2; 2nd, 38–52 mL/m2; and 3rd, > 52 mL/m2. For post-ablation LARR, the tertiles were 1st, <-19.6%, 2nd, -19.6 to -4.2%; and 3rd, >-4.2%. Table 1 summarizes the demographic characteristics of the entire cohort, while Supplementary Table 1 compares these characteristics across tertiles of post-ablation LAVI and LARR. Across post-ablation LAVI tertiles, patient severity generally increased with each higher tertile, as evidenced by mean age, CHA2DS2-VASc scores, and the prevalence of underlying structural heart disease (Supplemental Table 1A). In contrast, this trend was not observed for post-ablation LARR (Supplemental Table 1B). Furthermore, the pre-ablation LAVI value increased progressively across post-ablation LAVI tertiles (Supplemental Fig. 1A, 1st : 44 ± 11 mL/m2, 2nd : 52 ± 11 mL/m2, 3rd : 69 ± 19 mL/m2, p < 0.001). Conversely, the pre-ablation LAVI decreased across post-ablation LARR tertiles (Supplemental Fig. 1B, 1st : 59 ± 17 mL/m2, 2nd : 55 ± 17 mL/m2, 3rd : 50 ± 18 mL/m2, p = 0.001).

Fig. 1.

Study diagram. AF atrial fibrillation, LARR left atrial reverse remodeling, LAVI left atrial volume index, MACE major adverse cardiovascular event.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

| Characteristics | Total (n = 365) |

|---|---|

| Age (years), mean ± SD (0) | 66 ± 10 |

| Female sex, n (%) (0) | 82 (22) |

| SBP (mmHg), mean ± SD (0) | 128 ± 18 |

| HR (/min), mean ± SD (0) | 78 ± 16 |

| AF duration (months), median (IQR) [1] | 7 (4–21) |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean ± SD (0) | 25 ± 4 |

| History of HF hospitalization, n (%) (0) | 72 (20) |

| Pacemaker, n (%) (0) | 12 (3) |

| ICD/CRT, n (%) (0) | 14 (4) |

| CHA2DS2-VASc, mean ± SD (0) | 2.3 ± 1.6 |

| Hypertension, n (%) (0) | 208 (60) |

| DM, n (%) (0) | 68 (19) |

| Structural heart diseases | |

| CAD, n (%) (0) | 43 (12) |

| HCM, n (%) (0) | 22 (6) |

| DCM/DHCM, n (%) (0) | 11 (3) |

| VHD, n (%) (0) | 9 (2) |

| Congenital heart diseases, n (%) (0) | 4 (1) |

| Other cardiomyopathies, n (%) (0) | 6 (2) |

| Echocardiographic parameters | |

| LAVI (mL/m2), median (IQR) (0) | 54 ± 17 |

| Post-ablation LARR (%), median (IQR) (0) | -12 (-24–0) |

| LAD (mm), mean ± SD (0) | 45 ± 7 |

| LVDd (mm), mean ± SD (0) | 49 ± 6 |

| LVEF (%), mean ± SD (0) | 58 ± 13 |

| LVEF ≤ 50%, n (%) | 102 (28) |

| Ablation-related parameters | |

| Radiofrequency-PVI, n (%) (0) | 364 (99.7) |

| Cryo-PVI, n (%) (0) | 1 (0.3) |

| CTI-ablation, n (%) (0) | 53 (15) |

| Posterior wall isolation, n (%) (0) | 1 (0.3) |

| Left isthmus ablation, n (%) (0) | 1 (0.3) |

| SVC isolation, n (%) (0) | 289 (79) |

| Therapeutic agents | |

| ACEI/ARB, n (%) (0) | 180 (49) |

| ARNI, n (%) (0) | 14 (4) |

| Beta-blocker, n (%) (0) | 241 (66) |

| SGLT2i, n (%) (0) | 36 (10) |

| MRA, n (%), n (%) (0) | 70 (19) |

| Diuretics, n (%), n (%) (0) | 106 (29) |

| Digitalis, n (%), n (%) (0) | 11 (3) |

| Type I/III AADs, n (%), n (%) (0) | 44 (12) |

| Amiodarone, n (%) (0) | 31 (8) |

| Laboratory data | |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2), mean ± SD, n (%) (0) | 61 ± 17 |

| BNP level (pg/mL), median (IQR), n (%) (0) | 150 (89–224) |

Numerical data are expressed as mean ± SD or median (IQR; first quartile, third quartile), while categorical data are expressed as percentages and numbers. Notation [ ] denotes the missing rate of a specific data point.

AADs antiarrhythmic drugs, ACEI angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, AF atrial fibrillation, ARB angiotensin II receptor blocker, BMI body mass index, BNP brain natriuretic peptide, CAD coronary artery disease, CRT cardiac resynchronization therapy, CTI cavotricuspid isthmus, DCM dilated cardiomyopathy, DHCM dilated phase of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, DM diabetes mellitus, eGFR estimated glomerular filtration rate, HCM hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, HF heart failure, HR heart rate, ICD implantable cardioverter-defibrillator, IQR interquartile range, LARR left atrial reverse remodeling, LAVI left atrial volume index, LVDd left ventricular end-diastolic dimension, LVEF left ventricular ejection fraction, MRA mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist, PVI pulmonary vein isolation, SD standard deviation, SGLT2i sodium-glucose transport protein 2 inhibitors, SBP systolic blood pressure, SVC superior vena cava, VHD valvular heart disease.

MACE incidence across tertiles

During the entire follow-up period (median follow-up period: 5.2 years [IQR, 3.1–7.0 years]), 57 patients (16%) experienced at least one event, with a total of 102 documented events. Hospitalization due to HF accounted for the majority of these events (65 of 102 events, 64%), followed by all-cause death (20 of 102 events, 20%) and cardiovascular hospitalization (17 of 102 events, 16%). Malignancy was the predominant cause of all-cause mortality (40%), followed by cardiovascular disease (20%). Stroke was the leading cause of cardiovascular hospitalization (53%), followed by acute coronary syndrome and bradyarrhythmias, each accounting for 18% of the cases.

Figure 2 compares the cumulative incidence of MACE across tertiles. The incidence of MACE significantly increased with higher tertiles of post-ablation LAVI (Fig. 2A; Table 2, p < 0.001). The cumulative incidence of events at 5.2 years post-procedure was 8.4% (95% CI 2.9–13.5%) for the 1st tertile, 11.6% (5.4–17.5%) for the 2nd tertile, and 21.7% (12.4–30.0%) for the 3rd tertile. In contrast, the incidence of post-ablation LARR was comparable across the tertiles (Fig. 2B; Table 3, p = 0.900).

Fig. 2.

Kaplan–Meier curves comparing the cumulative incidence of MACE across tertiles A Comparison of post-ablation LAVI, B comparison of post-ablation LARR. Each plot is expressed as the cumulative incidence of an event with a 95% confidence interval. Asterisks indicate statistical significance (*p < 0.05). LARR left atrial reverse remodeling, LAVI left atrial volume index, MACE major adverse cardiovascular event.

Table 2.

Comparison of cumulative incidence of events across post-ablation LAVI tertiles.

| Cumulative incidence at median follow-up period (5.2 years), % (95% CI) | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First tertile (< 38 mL/m2) |

Second tertile (38–52 mL/m2) |

Third tertile (> 52 mL/m2) |

||

| *MACE | 8.4 (2.9–13.5) | 11.6 (5.4–17.5) | 21.7 (12.4–30.0) | < 0.001 |

| All-cause death | 5.3 (0.6–9.9) | 3.2 (0–6.6) | 2.8 (0–6.5) | 0.700 |

| *HF hospitalization | 2.7 (0–5.6) | 5.4 (1.0–9.7) | 17.3 (8.9–24.8) | < 0.001 |

| Cardiovascular hospitalization | 2.6 (0–5.6) | 5.5 (1.1–9.7) | 6.4 (0.6–11.8) | 0.700 |

CI confidence interval, HF heart failure, LAVI left atrial volume index, MACE major adverse cardiovascular event.

Asterisk (*) indicates statistical significance (p < 0.05).

Table 3.

Comparison of cumulative incidence of events across post-ablation LARR tertiles.

| Cumulative incidence at median follow-up period (5.2 years), % (95% CI) | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First tertile (<-19.6%) |

Second tertile (-19.6% to -4.2%) |

Third tertile (>-4.2%) |

||

| MACE | 14.6 (7.3–21.2) | 10.6 (4.3–16.6) | 15.2 (7.9–21.9) | 0.900 |

| All-cause death | 7.8 (1.9–13.2) | 0 | 3.4 (0–7.0) | 0.600 |

| HF hospitalization | 6.7 (1.7–11.4) | 9.0 (3.0–14.7) | 6.8 (1.7–11.6) | 0.800 |

| Cardiovascular hospitalization | 3.8 (0–5.8) | 3.1 (0–6.7) | 8.7 (3.0–14.0) | 0.600 |

CI confidence interval, HF heart failure, LARR left atrial reverse remodeling, MACE major adverse cardiovascular events.

Asterisk (*) indicates statistical significance (p < 0.05).

In the sensitivity analysis, 256 patients who underwent post-ablation echocardiography in sinus rhythm were analyzed, and the results were consistent. The cumulative incidence of MACE for the post-ablation LAVI was 9.5% (3.3–15.1%) in the 1st tertile, 13.9% (5.9–21.2%) in the 2nd tertile, and 26.0% (12.4–37.5%) in the 3rd tertile (p < 0.001). In contrast, for post-ablation LARR, the cumulative incidence of MACE was 14.5% (6.8–21.6%) in the 1st tertile, 13.2% (5.0–20.7%) in the 2nd tertile, and 17.7% (7.0–27.1%) in the 3rd tertile (p = 0.400).

Cumulative incidence of MACE components across tertiles

The cumulative incidences of individual MACE across post-ablation LAVI and LARR tertiles are illustrated in Supplemental Figs. 2 A and B, respectively. For the post-ablation LAVI, the incidence of HF hospitalization significantly increased across the ascending tertiles (p < 0.001), mirroring the overall MACE trend. In contrast, for post-ablation LARR, the incidence of all MACE remained similar across the tertiles.

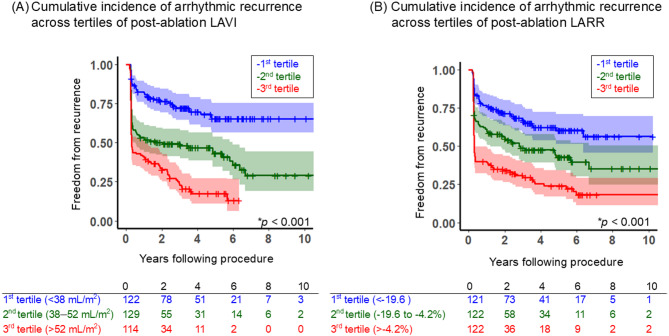

Arrhythmic recurrence across tertiles

Figure 3 illustrates a comparison of the cumulative incidence of arrhythmia-free survival across the tertiles (Fig. 3A: post-ablation LAVI; Fig. 3B: post-ablation LARR). For post-ablation LAVI, the recurrence rate increased significantly with increasing tertile (p < 0.001). The cumulative incidence of freedom from arrhythmic recurrence at 5.2 years post-procedure was 65.3% (56.5–75.5%), 43.2% (34.6–53.8%), and 17.4% (11.5–27.2%) for the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd tertiles, respectively. A similar trend was observed for post-ablation LARR, with the recurrence rate significantly associated with the tertiles (p < 0.001). The cumulative incidences of freedom from arrhythmic recurrence 5.2 years post-procedure were 60.4% (51.5–70.9%), 42.9% (34.1–53.9%), and 24.0% (16.9–34.2%) for the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd tertiles, respectively.

Fig. 3.

Kaplan–Meier curves comparing the cumulative incidence of freedom from arrhythmic recurrence across tertiles (A) Comparison of post-ablation LAVI, (B) Comparison of post-ablation LARR. Each plot expressed the cumulative incidence of freedom from the event with a 95% confidence interval (CI). Asterisks indicate statistical significance (*p < 0.05). LARR left atrial reverse remodeling, LAVI left atrial volume index.

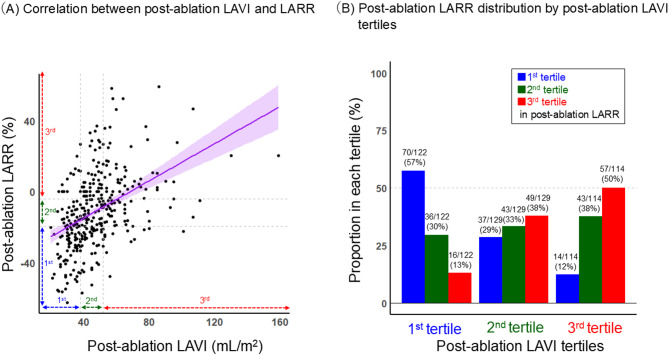

The association between LARR and post-ablation LAVI values

Figure 4 shows the scatter plot of post-ablation LAVI and LARR. Both values demonstrated a mild but significant positive linear correlation (Fig. 4A, R = 0.43 [95%CI: 0.35–0.51], p < 0.001). The lowest (1st ) tertile of LAVI corresponded modestly with the lowest LARR tertile, with 57% of patients being classified in the same tertile, while considerable variability was observed in other tertiles (Fig. 4B). Notably, both the 2nd tertiles of LAVI and LARR showed substantial variability, with wide distributions across all tertiles.

Fig. 4.

The association between post-ablation LAVI and LARR A Correlation between post-ablation LAVI and LARR. B Post-ablation LARR distribution by post-ablation LAVI tertiles. The purple line represents a positive linear correlation between Post-ablation LAVI and LARR, with a 95% confidence interval. LARR left atrial reverse remodeling; LAVI left atrial volume index.

Multivariate analysis

Table 4 presents the results of multivariate analysis for the development of MACE. Post-ablation LAVI emerged as an independent factor associated with MACE after multivariate adjustment (adjusted HR [95% CI] 1.02 [1.01–1.04], p < 0.001), unlike post-ablation LARR (0.98 [0.97–1.004], p = 0.162).

Table 4.

Multivariate analysis of factors associated with MACE.

| Variables | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| *Post-ablation LAVI (/1 mL/m2 increase) | 1.02 (1.01–1.04) | < 0.001 |

| Post-ablation LARR (/1% increase) | 0.98 (0.97–1.004) | 0.162 |

| *Age (/1 year increase) | 1.05 (1.01–1.09) | 0.005 |

| Female | 1.04 (0.56–1.93) | 0.900 |

| Pre-ablation LVEF (/1% increase) | 0.97 (0.95–1.00) | 0.051 |

| Arrhythmic recurrence at 3 months post-ablation | 0.90 (0.45–1.77) | 0.763 |

| *Pre-ablation BNP (/1 pg/mL increase) | 1.0001 (1.0002–1.002) | 0.017 |

| History of HF hospitalization | 1.65 (0.84–3.23) | 0.139 |

| Pre-ablation eGFR level (/1 mL/min/1.73m2 increase) | 0.99 (0.97–1.01) | 0.322 |

| Any structural heart disease | 1.07 (0.58–1.97) | 0.809 |

BNP brain natriuretic peptide, CI confidence interval, eGFR estimated glomerular filtration rate, HF heart failure, HR hazard ratio, LARR left atrial reverse remodeling, LAVI left atrial volume index, LVEF left ventricular ejection fraction, MACE major adverse cardiovascular events.

Asterisks indicate statistical significance (*p < 0.05).

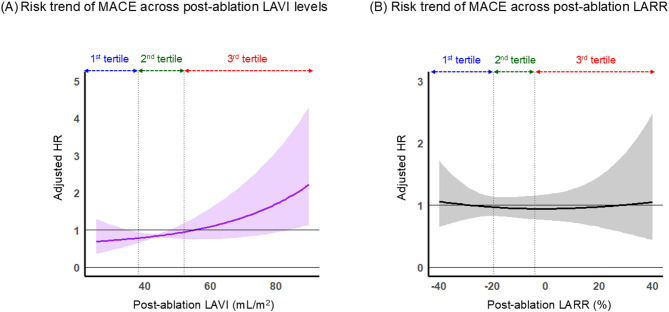

Figure 5 illustrates the spline curves depicting MACE risk in relation to post-ablation LAVI and LARR values. The risk associated with post-ablation LAVI showed a consistent increase as the LAVI values increased (Fig. 5A). In contrast, the post-ablation LARR did not exhibit a clear trend in MACE risk across the range of values (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Risk trend for MACE across the post-ablation LAVI and LARR A Across post-ablation LAVI values, B Across post-ablation LARR values. Each plot is expressed as an adjusted HR with a 95% confidence interval. The HR was adjusted for age, female sex, pre-ablation left ventricular ejection fraction, arrhythmic recurrence at 3 months post-ablation, pre-ablation brain natriuretic peptide level, history of heart failure hospitalization, pre-ablation estimated glomerular filtration rate, and any structural heart disease. HR hazard ratio, LARR left atrial reverse remodeling, LAVI left atrial volume index, MACE major adverse cardiovascular event.

Discussion

The key findings of this study are summarized as follows (Fig. 6; Graphical Abstract). First, although the incidence of MACE increased significantly with ascending post-ablation LAVI tertiles, the incidence across post-ablation LARR tertiles remained comparable. Second, the incidence of arrhythmic recurrence increased significantly with increasing tertiles in relation to both the post-ablation LAVI and LARR. Third, after multivariate adjustment, the post-ablation LAVI emerged as an independent factor associated with MACE following ablation; however, this was not the case for post-ablation LARR. The risk of MACE increased linearly with an increase in post-ablation LAVI values. In contrast, the post-ablation LARR did not exhibit a clear trend in relation to MACE risk. While the prognostic significance of post-ablation LAVI has been well established in previous literature, the novelty of our study lies in its direct comparative evaluation of LAVI and LARR in relation to long-term clinical outcomes.

Fig. 6.

Graphical abstract. AF atrial fibrillation, CA catheter ablation, CV cardiovascular, LARR left atrial reverse remodeling, LAVI left atrial volume index, MACE major adverse cardiovascular event.

Effect of post-ablation LARR

Left atrial remodeling in patients with AF involves multiple etiological processes, including pressure and volume overload, stimulation of neurohormonal factors, systemic inflammation, and electrophysiological changes, such as shortened refractory periods in atrial myocytes6. These stressors interact mutually, collectively promoting interstitial fibrosis within the atrial myocardium, thereby contributing to the perpetuation of AF16. However, sinus rhythm restoration through cardioversion or catheter ablation can halt this process, resulting in a reduction in left atrial volume18,19.

Although a standardized definition of LARR remains elusive, several studies have adopted a post-ablation reduction of 15–23% in LAVI as a threshold for identifying “responders” who have achieved significant LARR10,11,17,20. Responders typically experience more favorable atrial functional recovery and demonstrate lower arrhythmic recurrence rates after the procedure17. However, few studies have investigated the association between post-ablation LARR and long-term clinical outcomes.

In the present study, we observed a significant association between the degree of LARR and arrhythmic recurrence rates, which is consistent with the previous literature. However, we were unable to establish a clear relationship between the post-ablation LARR and the risk of MACE.

This may reflect the role of LARR in reducing the arrhythmogenic substrate through structural reverse remodeling, thereby contributing to lower recurrence rates. In contrast, MACEs are multifactorial and may arise from mechanisms unrelated to atrial arrhythmogenicity—such as progressive HF, thromboembolism, or underlying vascular disease—which may not be adequately captured by LARR alone. Additionally, this observation may be influenced by the substantial heterogeneity in LARR values, particularly pronounced at higher in patients with intermediate to large post-ablation LAVI, namely in the 2nd and 3rd tertiles (≥ 38 mL/m2). Notably, the 2nd tertile demonstrated wide variability from both perspectives, with post-ablation LARR values spanning across all post-ablation LAVI tertiles and vice versa. In addition, we observed that post-ablation LARR became more pronounced (i.e., smaller tertiles) with greater pre-ablation LAVI, contrasting with post-ablation LAVI patterns. For instance, a larger initial left atrial volume provides a greater denominator for the percentage change calculation, meaning a substantial absolute reduction can result in a very favorable LARR value, even if the final post-ablation LAVI is not the smallest. Conversely, a small pre-ablation left atrial volume may show minimal LARR despite a favorable post-ablation LAVI, simply because the potential for relative change is limited. These seemingly contradictory phenomena, where post-ablation LARR shows both concordant and discordant relationships with LAVI, likely arise from LARR reflecting the wide variation in baseline left atrial conditions. Align with this inference, while patient profiles became progressively more severe across increasing tertiles of post-ablation LAVI, the baseline characteristics showed no clear trends across post-ablation LARR tertiles. This heterogeneity complicates the straightforward interpretation of LARR for risk stratification.

Effect of post-ablation LAVI

Unlike the results for LARR, we observed a significant increase in the risk of MACE associated with incremental increases in the post-ablation LAVI. This discrepancy may be attributed to the role of the LAVI as a downstream indicator of the LARR pathway, which reflects the final manifestation of atrial remodeling. Consequently, the post-ablation LAVI may provide a more direct and simplified representation of atrial remodeling.

Emerging evidence suggests that left atrial volume may serve as an incremental marker for adverse events post-ablation, as well as for rhythm outcomes12,13,18. For example, an increased preprocedural LAVI has been linked to an increased risk of adverse clinical events, including HF and stroke18. Furthermore, we previously reported that patients who achieved modest post-ablation LAVI, despite having enlarged LAVI before the procedure, demonstrated comparably low MACE risk as those with initially small LAVI13.

The data in the present study also demonstrated that patients with larger post-ablation LAVI commonly presented with more severe clinical profiles, suggesting that the higher MACE risk in these patients may not be attributable to left atrial pathology alone. Recently, patients with blunted recovery of left atrial size after ablation have been suggested to have underlying atrial cardiomyopathy, a condition that may not fully respond to catheter ablation procedures due to persistent atrial myocardial degenerative changes that remain even after AF elimination19–21.

The concept of atrial cardiomyopathy is evolving and encompasses a spectrum of structural, functional, and electrical abnormalities affecting the atria, predisposing to AF and adverse outcomes19. Importantly, as highlighted by recent research, atrial cardiomyopathy does not always manifest as gross left atrial enlargement; a stiff, fibrotic atrium may fail to dilate significantly yet harbor advanced disease22,23. Furthermore, some components of atrial remodeling, such as interstitial edema, may be reversible with rhythm control, while more established fibrosis and cellular changes might persist, limiting the extent of reverse remodeling24.

Although atrial cardiomyopathy primarily indicates atrial pathology, it may encompass latent myocardial degeneration (e.g., amyloidosis), thus linking to ventricular dysfunction19. The patients with larger post-ablation LAVI, particularly those in the 3rd tertiles, characterized by persistently greater post-ablation LAVI, poor LARR, and high prevalence of underlying heart disease, may predominantly comprise patients with this atrial cardiomyopathy pathology. In addition, this subgroup with the largest post-ablation LAVI also exhibited higher mean ages and higher CHA₂DS₂-VASc scores. This observation underscores that a large post-ablation LAVI might reflect not only the severity of atrial remodeling itself but also a more vulnerable patient cohort with a greater burden of extracardiac comorbidities and systemic risk factors. Therefore, while post-ablation LAVI is a strong indicator, it is crucial to acknowledge that it may represent a confluence of factors, rather than being the sole determinant of adverse outcomes. Hence, our data suggest that for patients presenting with this profile – characterized by a large post-ablation LAVI in the context of higher CHA₂DS₂-VASc scores and a greater comorbidity burden – the benefits of catheter ablation in terms of MACE reduction may be limited, even if sinus rhythm is successfully restored.

Furthermore, our spline curve analysis visually suggested that while MACE risk generally increases with post-ablation LAVI, the risk escalation becomes notably steeper once LAVI exceeds approximately 50 mL/m² (Fig. 5A). This threshold falls within the upper range of our 2nd tertile and encompasses the 3rd tertile. Given that the patient demographics of these tertiles share several high-risk characteristics, this finding suggests that the 2nd tertile may represent a heterogeneous group with varying degrees of underlying risk, which could explain the observed inflection in MACE risk. Although the present study, which focused on volumetric changes of the left atrium, could not provide the information to further stratify risk within this intermediate LAVI range, future investigations incorporating advanced modalities that can assess functional changes of the left atrium, such as left atrial strain or cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, may be warranted to achieve more precise risk stratification in this subgroup.

Clinical implication

Our results highlight the distinct clinical significance of the post-ablation LAVI and LARR in patients with persistent AF who undergo catheter ablation. Although both parameters effectively stratified the risk of arrhythmic recurrence, only post-ablation LAVI emerged as a reliable marker for predicting the risk of long-term post-ablation MACEs. Our study adds novelty by addressing the prognostic value of these two post-ablation parameters in direct comparison. The post-ablation LAVI was particularly effective in stratifying the risk of hospitalization for HF, which was the primary component of MACE in our study. While post-ablation LAVI offers a readily accessible and valuable prognostic indicator, a larger value might reflect not only the extent of atrial remodeling itself but also a broader spectrum of underlying patient comorbidities and systemic risk factors, suggesting its significance could extend beyond isolated atrial pathology. Conversely, the LARR remains a valuable parameter for predicting arrhythmic recurrence. While its utility for MACE prediction was less pronounced than that of post-ablation LAVI in our overall cohort, LARR could potentially hold particular relevance for stratifying arrhythmic recurrence risk in patient subgroups inherently at low risk for MACE. We previously reported that patients with low pre-ablation BNP levels, who often present as younger individuals with fewer comorbidities, generally have a lower overall MACE risk25. For such patient cohorts, information regarding arrhythmia recurrence may be relatively more critical than MACE prediction itself. In these scenarios, where the primary concern shifts from MACE to rhythm control, LARR might serve as a useful, albeit adjunctive, prognostic tool for arrhythmia recurrence.

Limitations

Our study had several limitations. First, its single-center retrospective design inherently restricts the generalizability of our findings. The extent of LARR can vary significantly based on population characteristics including coexisting heart diseases, comorbidities, and medication profiles6. In particular, we could not fully account for potential unmeasured confounders. For instance, variations in medication adherence (e.g., to anticoagulants or HF medications) or differences in the intensity and type of HF treatment across patients could have influenced long-term outcomes. Although we adjusted for several known confounders in our multivariate analysis, residual confounding cannot be entirely excluded. Therefore, external validation through multicenter prospective studies is crucial to establish broader applicability and reproducibility of our results.Second, our study population predominantly consisted of patients with a preserved left ventricular ejection fraction. Although this aligns with the typical profile of patients undergoing AF ablation in clinical practice, making our findings particularly relevant, it also raises uncertainty regarding the applicability of our findings to patients with impaired systolic function. This subgroup often includes cases of arrhythmia-induced cardiomyopathy26 in which LARR may play a more crucial role. Therefore, it is important to evaluate these findings in this population. Third, echocardiographic measurements, including LAVI, are subject to intra- and inter-observer variability, despite efforts to standardize acquisition and analysis as per guidelines. While we used a consistent methodology described previously, such variability could introduce some imprecision into our LAVI assessments and subsequent risk stratification. Prospective studies with core laboratory adjudication of echocardiographic parameters could mitigate this limitation. Furthermore, our study relied on left atrial volumetric assessment. While informative, this approach may not fully differentiate risk within the intermediate post-ablation LAVI range (i.e., the 2nd tertile), where our data suggest risk escalation begins. Incorporating other modalities, such as left atrial strain or left atrial pressure, could potentially improve risk stratification in this heterogeneous subgroup. Fourth, the primary assessment of post-ablation LAVI and LARR was conducted at 3 months post-procedure. This timepoint is consistent with previous studies9,12 and aligns with our routine comprehensive follow-up protocol. However, we acknowledge that reverse remodeling can still be an ongoing process at this timepoint. Focusing on this single early assessment point may not have fully captured the complete trajectory of LARR in all individuals, potentially leading to an underestimation of its eventual magnitude or misclassification of some patients with more protracted remodeling. However, conducting echocardiographic assessments at later time points (e.g., six months or one year) for all patients would have been difficult in this retrospective cohort due to the increased risk of missing data and selection bias, particularly since our routine follow-up protocol included echocardiography at three months post-ablation. Patients who had echocardiographic data beyond the three-month mark were more likely to represent a clinically distinct subgroup, such as those who experienced symptom worsening or arrhythmic recurrence during follow-up. Fifth, our assessment of arrhythmic recurrence relied on 24-hour Holter monitoring at scheduled intervals. While our study population comprised patients with persistent AF, where recurrences often re-manifest in a persistent form25making them more amenable to detection with standard Holters, this method may still underestimate the true burden of arrhythmia, particularly any paroxysmal episodes. More prolonged or continuous monitoring would be ideal for a complete assessment.

Finally, our study encompassed a broad time range (up to a decade after patient inclusion). Although most cases were collected after 2016, catheter ablation in contemporary clinical practice has shown improvements in procedural outcomes owing to ongoing technological advancements27. Although we observed consistent results in a subgroup of patients who achieved sinus rhythm on post-ablation echocardiography, validation studies involving more recent cohorts are recommended to guarantee the applicability of our findings to contemporary clinical settings. It is also important to reiterate that while post-ablation LAVI emerged as a strong predictor, it may reflect broader atrial pathology and a constellation of risk factors rather than acting as a purely independent predictor of MACE. This nuanced interpretation is crucial when applying our findings.

Conclusions

The incidence of MACE increased significantly in the ascending tertiles of post-ablation LAVI; however, the incidence was comparable across the tertiles of post-ablation LARR. The post-ablation LAVI demonstrated efficacy as a marker for stratifying the risk of both MACE, particularly hospitalization for HF and post-procedure arrhythmic recurrence. While post-ablation LAVI is a feasible and significant indicator, its interpretation should consider that a larger value may reflect not only advanced atrial remodeling but also a broader patient risk profile, extending beyond isolated atrial pathology.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.jp) for English language editing. Before professional editing, the manuscript was proofread by Claude, an AI assistant.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: HI, YY. Data curation: HI, MF, SF, SH. Formal analysis: HI, MH. Investigation: HI, TO. Methodology: HI, SK, MS. Project administration: HI, YY, MS. Resources: YY, TO. Software: HI. Visualization: HI, MH. Validation: HI. Writing-original draft: HI. Writing-review & editing: YY, MF, NF, SK, MS. Supervision: SK, MS. Guarantor: HI.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grants from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

Patient-level data are not publicly available as the Institutional Review Board (Institutional Review Board of Yamaguchi University Hospital) did not authorize their release. However, the data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical information

Our institutional Ethics Committee approved the study (approval number: H2019-044) and waived the requirement for informed consent due to the implementation of an opt-out system.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Gómez-Outes, A. et al. Causes of death in anticoagulated patients with atrial fibrillation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol.68, 2508–2521 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.An, Y. et al. Causes of death in Japanese patients with atrial fibrillation: the Fushimi atrial fibrillation registry. Eur. Hear. J. - Qual. Care Clin. Outcomes. 5, 35–42 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Savarese, G. et al. Global burden of heart failure: a comprehensive and updated review of epidemiology. Cardiovasc. Res.118, 3272–3287 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mundisugih, J. et al. Prevalence and prognostic implication of atrial fibrillation in heart failure subtypes: systematic review and Meta-Analysis. Hear. Lung Circ.32, 666–677 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sartipy, U., Dahlström, U., Fu, M. & Lund, L. H. Atrial fibrillation in heart failure with preserved, Mid-Range, and reduced ejection fraction. JACC Hear. Fail.5, 565–574 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thomas, L. & Abhayaratna, W. P. Left atrial reverse remodeling. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging. 10, 65–77 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nishino, S. et al. Reverse remodeling of the mitral valve complex after radiofrequency catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging12(10), e009317 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Poole, J. E. et al. Recurrence of atrial fibrillation after catheter ablation or antiarrhythmic drug therapy in the CABANA trial. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol.75, 3105–3118 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rettmann, M. E. et al. Treatment-Related changes in left atrial structure in atrial fibrillation: findings from the CABANA imaging substudy. Circ. Arrhythmia Electrophysiol14(5), e008540 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Tops, L. F. et al. Left atrial strain predicts reverse remodeling after catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol.57, 324–331 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakanishi, K. et al. Pre-Procedural serum atrial natriuretic peptide levels predict left atrial reverse remodeling after catheter ablation in patients with atrial fibrillation. JACC Clin. Electrophysiol.2, 151–158 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wen, S. et al. Association of postprocedural left atrial volume and reservoir function with outcomes in patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing catheter ablation. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 35, 818–828e3 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ishiguchi, H. et al. Novel method for risk stratification of major adverse clinical events using Pre- and Post-Ablation left atrial volume index in patients with persistent atrial fibrillation. Circ. Rep. CR-24-0062. 10.1253/circrep.CR-24-0062 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joglar, J. A. et al. 2023 ACC/AHA/ACCP/HRS guideline for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation: A report of the American college of cardiology/american heart association joint committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation149(1), e1–e156 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Ishiguchi, H. et al. Long-term events following catheter‐ablation for atrial fibrillation in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. ESC Hear. Fail.9, 3505–3518 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pozios, I., Vouliotis, A. I., Dilaveris, P. & Tsioufis, C. Electro-Mechanical alterations in atrial fibrillation: structural, electrical, and functional correlates. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis.10, 149 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Machino-Ohtsuka, T. et al. Significant improvement of left atrial and left atrial appendage function after catheter ablation for persistent atrial fibrillation. Circ. J.77, 1695–1704 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Masuda, M. et al. Clinical impact of left atrial remodeling pattern in patients with atrial fibrillation: comparison of volumetric, electrical, and combined remodeling. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol.35, 171–181 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goette, A. et al. Atrial cardiomyopathy revisited—evolution of a concept: a clinical consensus statement of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) of the ESC, the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS), the Asian Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS), and the Latin American Heart. Europace26 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Reddy, Y. N. V., Noseworthy, P., Borlaug, B. A. & Albert, N. M. Screening for unrecognized HFpEF in atrial fibrillation and for unrecognized atrial fibrillation in HFpEF. JACC Hear. Fail.12, 990–998 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kessler Iglesias, C. et al. Atrial cardiomyopathy: current and future imaging methods for assessment of atrial structure and function. Front. Cardiovasc. Med.10,1099625 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Takahashi, Y. et al. Histological validation of atrial structural remodelling in patients with atrial fibrillation. Eur. Heart J.44, 3339–3353 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamaguchi, T. et al. Atrial structural remodeling in patients with atrial fibrillation is a diffuse fibrotic process: evidence from High-Density voltage mapping and atrial biopsy. J. Am. Heart Assoc.11(6), e024521 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Yamaguchi, T. Atrial structural remodeling and atrial fibrillation substrate: A histopathological perspective. J. Cardiol.85, 47–55 (2025). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ishiguchi, H. et al. Integrating pre-ablation and post-ablation B-type natriuretic peptide to identify high-risk population for long-term adverse events and arrhythmic recurrence in persistent atrial fibrillation. Open. Hear.12, e003251 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huizar, J. F., Ellenbogen, K. A., Tan, A. Y. & Kaszala, K. Arrhythmia-Induced cardiomyopathy: JACC State-of-the-Art review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol.73, 2328–2344 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pallisgaard, J. L. et al. Temporal trends in atrial fibrillation recurrence rates after ablation between 2005 and 2014: a nationwide Danish cohort study. Eur. Heart J.39, 442–449 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Patient-level data are not publicly available as the Institutional Review Board (Institutional Review Board of Yamaguchi University Hospital) did not authorize their release. However, the data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.