Abstract

Wastewater from the oil and gas industry is notoriously challenging to treat due to its complex composition. In this work, polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) was used to modify graphene oxide (GO) nanoparticles for the synthesis of PSf based thin-film nanocomposite (TFN) membranes through the interfacial polymerization (IP) technique, aimed at oil removal from wastewater. The composite membrane, incorporated with GO, at different PVP loadings (0.025 wt%, 0.030 wt%, and 0.035 wt%) were fabricated and characterized using FESEM, AFM, ATR-FTIR, UV–Vis spectra, tensile strength and contact angle goniometer. It is found that with the presence of PVP-GO inside the TFN membranes, it exhibited higher surface hydrophilicity due to an increment in hydroxyl and carboxyl groups in the polyamide (PA) layer, which improves the attraction between water molecules and membrane surface. TFN membrane assimilated with 0.035 wt% PVP-GO achieved 48.871 L/m2.h and flux recovery ratio of 88% of water flux with decreased contact angle up to 46° and thin film thickness of 137 nm as compared to the TFN membranes without the addition of PVP with 34.118 L/m2.h of water flux. Overall, the PVP-modified GO nanocomposite membranes in this work demonstrated promising performance for oil-in-water emulsion separation, which makes them an attractive candidate for industrial water separation especially for produced water treatment.

Keywords: Graphene oxide, Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP), Thin film nanocomposite membrane, Forward osmosis, Oily wastewater

Subject terms: Chemical engineering, Graphene

Introduction

There is an estimation that global oil production is expected to rise by about 50% by 20251. The discharge of oily wastewater from industries such as petrochemicals, daily chemicals, textiles, leather, and metal finishing can lead to several environmental and ecological concerns on land2. The prohibition of direct disposal of oily wastewater and the requirement to meet discharge standards are common regulatory measures implemented by governments to protect the environment and public health3. The existing water treatment methods, such as physical, chemical, and biological, have drawbacks including high energy consumption, production of harmful by-products, low separation rates4,5, and removal of oil droplets with a diameter greater than 10 µm is limited6.

Therefore, membrane separation technology stands out as a versatile and effective solution for water treatment, especially in the removal of contaminants like oils and emulsions from wastewater7. Processes such as microfiltration (MF), ultrafiltration (UF), nanofiltration (NF), and reverse osmosis (RO) are based on the nominal size of the pores in these membranes, on the principle of selectively allowing certain substances to pass through a semi-permeable membrane while blocking others8. Table 1 Provides a comparison of these process technologies for oil and water separation.

Table 1.

Membrane technologies of oil/water emulsion separation.

| Membrane processes | Merits | Demerits | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microfiltration |

• Lowest pressure applied • Colloidal can be removed |

• Oil drops pile up on the exterior of the membrane • Produce polarization layer |

2,9–11 |

| Ultrafiltration | • Non-detrimental separation, without phase transition |

• Concentration polarization • Membrane fouling |

6,9,11–14 |

| Nanofiltration | • Can hold divalent ions | • Complex process | 6,9,11–13 |

| Reverse Osmosis |

• Yield high-level quality treated water • Nearly perfect elimination of all the components found in oily wastewater |

• Membrane fouling • Extra chemical and energy cost for membrane clean-up and substitutes • Additional downtime of the apparatus treatment • Demands efficient pretreatment for oil and grease exclusion |

6,11–13 |

Forward osmosis (FO) has garnered increasing attention as its unique features including the use of lower process pressure, higher efficiency, achieving high recovery and requires a smaller footprint, make it a technology with widespread potential applications amongst all15,16. In addition, the low membrane fouling potential of FO is a significant advantage, particularly when applied without the need for draw solute recovery, makes it an attractive technology for the treatment of oily wastewater17. Therefore, FO has gained substantial attention from both academic researchers and industries due to its unique advantages and potential applications18.

Oily wastewater treatment can be achieved by using inorganic and polymeric membranes12. Inorganic membranes such as zeolites, ceramics, glass, and metals, exhibit excellent properties for water filtration, however, they are expensive and require intricate fabrication processes, restricting their commercialization9. On the other hand, polymers such as polyacrylonitrile (PAN), polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF), polyethersulfone (PES), and polysulfone (PSf)19 demonstrate superior mechanical potency, incredible flexibility, and chemical steadiness20. Yet having a limited membrane lifespan due to fouling remains the major challenge of polymeric membranes on oily wastewater treatment21. Among the polymeric membranes, Polysulfone (PSf) is widely used due to its thermal stability, pH resistance, mechanical and chemical strength, and good ability for forming membranes as support layer, shows high rejection for ions22.

Therefore, a thin film composite (TFC) membrane comprises of polymeric and inorganic material has been introduced to defeat their drawbacks. Recent studies have shown a significant increase in the application of carbon-based nanomaterials. CNTs offer remarkable properties that make them highly effective for oily wastewater treatment. Yet, their full-scale application is limited by high fabrication costs and environmental concerns23,24. Similarly, in recent years, incorporating hydrophilic nanomaterials such as alumina, silica, titanium dioxide, and zeolites into TFC membranes has significantly enhanced their performance by improving permeability, selectivity, and antifouling properties25. However, achieving these benefits requires careful optimization of nanofiller concentration to prevent aggregation and ensure uniform dispersion within the membrane matrix25. Emerging materials such as MAX phase and MXene have also been explored due to their tunable surface chemistry and layered structures, offering new directions in membrane design26,27. However, the roughness is increased by adding MAX phase which increases the fouling effect26. Similarly, the development of more facile and efficient techniques for the large-scale production of MXene-membranes is required. Also, tuning the membrane characteristics, and applications in real conditions are the major challenges27. Table 2 Shows a comparison of these nanomaterials based thin film nanocomposite membranes performances. According to Table 2, these findings underline the importance of carefully optimizing nanoparticle concentration in membrane fabrication. While nanomaterials can enhance flux and selectivity, excessive loading often causes aggregation, pore blockage, or loss of structural integrity.

Table 2.

Nanomaterials based thin film nanocomposite membranes performances.

| Polymer | Inorganic filler | NP conc. (g) | Water flux (LMH) | Main finding | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PES | TiO2 | 5.00 | 34.30 | Internal concentration remains a challenge in FO process | 28 |

| PSf | ZIF-8 | 0.2 | 1.39 |

NPs became larger after PSS coating ZIF-8 particles lost their stability due to degradation and agglomeration in water during PSS coating |

29 |

| PSf | CNT | 0.01 | 37.00 |

Increasing NP concentration affects the interfacial polymerization process and change the selectivity of the membranes Full-scale application is limited by high fabrication costs and environmental concerns |

24,30,31 |

| PSf | SiO2 | 0.05 | 22.50 | A critical need for optimizing the silica nanoparticle loading was required, overloading of silica was not advantageous for FO performance and even has the negative impact on the membrane properties | 30,32 |

| PES | MAX phase | 0.025 | 7.57 | No significant change observed in the porosity of membrane when varying the MAX content. While a dramatic change was witnessed in the pore size when increasing the MAX phase content from 0.025 to 0.075 wt% | 26 |

| CA | MXene | 4.00 | 125.10 |

The development of more facile and efficient techniques for the large-scale production of MXene-membranes are required Tuning the membrane characteristics, and applications in real conditions are the major challenges |

27 |

On the other hand, graphene, known for its remarkable mechanical, thermal, electrical, and functional properties, has a two-dimensional planar structure. However, its inherent hydrophobic nature poses challenges for its use in fabricating hydrophilic membranes, especially for applications like oily wastewater treatment24. Graphene oxide (GO), the oxidized form of graphene, is inherently hydrophilic due to its strongly polarized functional groups24. GO in industrial wastewater treatment, yielding extremely positive outcomes23. The incorporation of oxygen functional groups, such as hydroxyl, epoxy, and carboxyl groups, introduce polar sites onto the graphene sheets, making them more compatible with polar solvents and polymers. As a result, the dispersion of GO in solvents and polymers improves significantly33. Moreover, these functional groups, making it a valuable material for fabricating hydrophilic membranes for oily wastewater24. It has been reported that GO has garnered significant attention as novel membrane modifiers as it has unique properties including large surface area, great compatibility, prominent electron transport and great mechanical properties as well as lower economic cost which contributes to its versatility in various applications34. Furthermore, leveraging the antibacterial properties of GO in the fabrication of FO membranes holds significant promise for addressing biofouling challenges35.

An important consideration in the effective utilization of GO nanosheets is to control the morphology and surface chemistry of GO nanosheets to minimize aggregation36. Increasing the concentration of GO leads to greater aggregation, which can be mitigated through functionalization. Studies found that removing oxygen-containing functional groups from GO led to increased agglomeration in nanocomposites. This suggests that the presence of functional groups helps prevent aggregation by stabilizing the GO sheets37,38. These studies collectively indicate that increasing GO concentration can lead to greater aggregation, however appropriate functionalization with hydrophilic groups can mitigate this effect. Hence, enhance dispersion, and improve the overall performance of membranes, particularly in terms of water permeation36. Research demonstrated that functionalizing GO with hydrophilic organic molecules enhances its stability in aqueous solutions, thereby reducing aggregation39. The concentration range of GO selected in our study was based on reported values in the literature, where GO concentrations such as 0.0013 wt%, 0.004 wt%, 0.008 wt%, 0.01 wt%, and 0.015 wt% have been shown to enhance membrane performance particularly in forward osmosis applications involving seawater treatment25,40–43. However, oily wastewater presents a more complex challenge due to the presence of emulsified oil droplets, surfactants, and organic contaminants, which require membranes with enhanced antifouling and separation properties.

To address this complexity, higher concentrations of GO are often necessary, provided that the GO is adequately dispersed and modified to prevent agglomeration, which would otherwise negatively impact membrane morphology and performance. In our study, we selected GO concentrations that extend slightly beyond those used in desalination research to evaluate their synergistic interaction with PVP and their effectiveness in treating oily wastewater. We were careful to avoid excessive loading to mitigate the risk of GO aggregation, which can compromise membrane performance. The chosen concentrations therefore reflect a balance between leveraging GO’s beneficial properties and maintaining membrane structural integrity. Furthermore, previous studies showed other polymer-GO composites for water treatment such as Kim et al. poly (Nisopropylacrylamide-co–N, N’-methylene-bisacrylamide) functionalized GO (~ 25.8 LMH)44 and GO-TA membranes (~ 25.7 LMH)45.Similarly, polydopamine/graphene oxide (PDA/GO) with water flux 17.32 LMH46, and graphene oxide-graft-poly(2-hydroxy ethyl methacrylate) (GO-g-PHEMA, GP) nanoplates with permeate flux 15.6 LMH47.

Other hydrophilic polymers, such as polyvinyl pyrrolidone (PVP) and polyethylene glycol (PEG), are commonly used as pore-forming additives in the fabrication of membranes48. PVP is recognized for its multifunctional roles in membrane fabrication for its additional benefits such as anti-biofouling and improved water flux22. Moreover, it has a water-soluble linear structure of polyamide with strong hydrophilicity with high chemical stability, nontoxicity, and excellent solubility in many polar solvents as well as with lower procurement cost making it widely useful for biological and chemical species49–51. PVP served as a stabilizer and ascorbic acid was used as a reducing agent for graphene oxide52. PVP is an amphiphilic polymer characterized by having both hydrophilic and lipophilic groups along its backbone. This dual nature allows PVP to effectively disperse single-layer graphene in various solvents, including water53. When PVP is added to a GO suspension, a strong interfacial interaction between PVP and GO occurs, promoting the molecular-level dispersion of GO nanosheets54. It has been reported that hydrophilic GO can form hydrogen bonds with PVP, which provides an effective way to change the surface properties of GO55. The homogeneous distribution of GO particles within the membrane matrix, facilitated by hydrogen bonding with PVP, is a key factor in enhancing the performance of GO-PVP composite membranes49. Furthermore, PVP contributes to superior hydrophilicity due to its amide groups, which help in minimizing organic fouling, especially from oily substances. This gives PVP-GO an advantage over TA, PVA, and poly (Nisopropylacrylamide-co–N, N’-methylene-bisacrylamide), PDA/GO, and GO-g-PHEMA, GP functionalized GO for FO processes44–47,56, where fouling mitigation mechanisms are either weaker or not as versatile.

Previous studies have primarily functionalized graphene oxide (GO) with polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) to enhance electrical properties, enable innovative biological applications, and improve biocompatibility51,57,58. Although Junaidi et al. employed PVP-modified GO to improve hydrophilicity in forward osmosis membranes, its fouling resistance under oily wastewater conditions was not investigated49. Likewise, Poolachira et al. demonstrated effective heavy metal rejection using similar materials, but their performance against oil–water emulsions remain untested59. Furthermore, in the previous study (Xing Wu)60, a composite membrane incorporating 0.0175 wt% GO with 25 mg PVP was tested for desalination applications under ALDS (active layer facing draw solution) mode, achieving a water flux of 33.2 LMH. In contrast, the current study explores the same GO concentration (0.0175 wt%) but increases the PVP content to 35 mg, applying the membrane for oily wastewater treatment under ALFS (active layer facing feed solution) mode. This comparison confirms that the combination of PVP and GO in a TFN membrane matrix for oily wastewater treatment via forward osmosis has not been reported previously. It showing that our study offers a new combination of PVP and GO in TFN membranes with improved antifouling and separation performance.

The addition of PVP-modified GO increases the hydrophilicity of the membrane surface due to decreased aggregation, resulting in lower contact angles. This enhancement facilitates higher water flux and better antifouling properties49. Furthermore, the incorporation of PVP-modified GO imparts bactericidal activity to the membrane surface, reducing biofouling. This results in sustained membrane performance and longer operational lifespan61. Hence, these advantages make PVP-modified GO nanoparticles a superior additive for enhancing the performance of TFN FO membranes compared to unmodified GO and with other polymer based modified GO membranes. Therefore, graphene oxide (GO) was selected due to its strong hydrophilicity, rich oxygen-containing groups, and compatibility with polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP), providing a practical and scalable approach to enhance membrane properties for oily wastewater treatment.

In the present work, thin-film composite (TFC), GO and PVP-modified GO thin-film nanocomposite membranes were prepared on PSf support by interfacial polymerization method and analysed by the contact angle, field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM), attenuated total reflection (ATR) attached with Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy and atomic force microscopy (AFM) and mechanical properties by tensile strength and elongation at break test. The prepared membrane’s performance was then evaluated using a crossflow filtration FO setup. Moreover, a comparison was made between the TFC membrane and the TFN membrane loaded with GO nanoparticles and GO-modified membranes to assess the impact of these modifications on overall separation efficiency. The aim of this work investigates the impact of varying the PVP (pore-forming additive) concentrations towards membrane performances besides evaluating the membrane porosity and hydrophilicity after adding PVP as well as graphene oxide. It is necessary to seek the optimal concentration of pore-forming additives in order to optimize the hydrophilicity and pore structure which may could influence the performance of the membrane. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study reporting on PSF/PVP-GO TFN membrane for oily wastewater as well as address the challenges associated with the dispersion and stability of graphene oxide (GO) in membrane applications. This work may open new avenues for the use of PSF/PVP-GO based nanocomposites in membrane technology, contributing to new material combinations for enhancing separation processes.

Materials and methods

Polysulfone (PSf, Solvay P3500, Aldrich), 1-methyl-2-pyrrolidinone (NMP, ≥ 99%, Merck), Trimesoyl chloride (TMC, 98%, Aldrich), and m-phenylenediamine (MPD, 99%, Aldrich) were used as received. Meanwhile, n-hexane (Merck) was used as TMC solvent. For the modification of graphene oxide (GO) (4 mg/ml), Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP K30) and L-ascorbic acid (L-AA, ≥ 99%) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich. In addition, for the synthesis of synthetic oily wastewater, soybean oil (Sigma Aldrich), sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) as surfactant, and sodium chloride (Sigma Aldrich) were used for membrane performance testing.

Preparation of PVP-modified GO

GO was modified with PVP using the procedure reported by Wu et al.51, and Wang et al.52. Figure 1 shows the schematic of the preparation of PVP-modified GO. First, 250 mg of GO was added into 100 ml of deionized water before sonicated for about 60 min to attain even distribution. For the modification of graphene oxide, 25 mg of PVP and 50 mg of L-AA were added into GO dispersion as a surface modifier and reducing agent, respectively. The mixture was then used in a stirrer for around 10 min at normal temperature and kept in a water bath for 4 h at 80 °C. The suspension was then centrifugated at 12,000 rpm for 15 min and washed with deionized water three times to remove the surplus amount of PVP and L-AA. Lastly, PVP-modified GO was re-dispersed into 100 ml of deionized water for future use. This procedure was repeated for 30 mg, and 35 mg of PVP, respectively. Similarly, the GO dispersion into 100 ml deionized water was prepared without PVP addition for control experiment. The modified GO particles with different concentrations; 25 mg, 30 mg, and 35 mg were designated as PVP-GO-1, PVP-GO-2, and PVP-GO-3, respectively. The selected PVP loadings were chosen based on preliminary studies and literature reports. Lower concentrations < 0.020 wt%) were excluded as they have a negligible effect on membrane morphology and performance, offering limited improvement in water flux or antifouling properties. Conversely, higher concentrations (> 0.040 wt%) were avoided due to potential issues such as excessive pore formation, membrane brittleness, or PVP leaching, which could compromise membrane mechanical stability and long-term performance. Thus, the chosen range was considered most relevant for evaluating the impact of PVP on membrane characteristics within a practical and effective formulation window51,55,62–65.

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram of PVP modified GO preparation.

Preparation of PSF support layer

PSF substrate membrane was prepared via a non-induced phase inversion process as reported by Jurkuyeh et al.42. Firstly, 2 wt% of PVP and 16 wt% of PSf were dissolved into NMP before stirring for 8 h at 60 °C and degassed for 48 h to obtain a clear casting mixture. The PSf based support layer mixture was then liquidated onto the clear glass plate and casted by casting knife with thickness of 175 μm thickness, before being immediately placed into a water bath. The phase separation process in the water bath triggered the conversion of the casting solution from a solvent-rich state to a non-solvent-rich state, which directed the development of the support layer. The membrane was then removed from the water bath, it is stored in deionized water before use to ensure its stability and preserve its properties.

Fabrication of TFC, GO, and PVP-modified GO TFN membranes

TFC FO membrane was prepared by interfacial polymerization reaction (IP) reaction on the top surface of the PSF substrate66. 2 wt% of MPD aqueous solution was transferred onto the substrate’s top surface and then the excess solution was poured off before the residual drops on the membrane were dried using a roller. After that, the membrane skin side was exposed to 0.1 wt/vol % TMC-n-hexane solution for 1 min for IP reaction. Then, the membrane was dried in an oven for 8 min at 60 °C. Subsequently, the as-prepared membrane was preserved in deionized water for further evaluation. A similar method was applied for the TFN membrane preparation with the additional steps where GO and PVP-modified GO were dispersed with 0.0175 wt % loading in the MPD aqueous solution before being transferred onto the substrate’s top surface. It has been previously reported that the separation performance of TFC membranes decreases when the concentration of GO in the aqueous phase solution exceeds 0.015 wt%25. The membranes fabricated in the present work are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

The concentration of nanoparticles in MPD solution.

| Membrane | PVP in GO solution (wt%) | GO solution (wt%) |

|---|---|---|

| TFC | 0.000 | 0.0000 |

| TFN | 0.000 | 0.0175 |

| TFN-1 | 0.025 | 0.0175 |

| TFN-2 | 0.030 | 0.0175 |

| TFN-3 | 0.035 | 0.0175 |

Characterization of GO, PVP-GO particles, and membranes

The particles were analyzed using Marvern Zetasiver Nano-Zeta Potential analyser. The aggregation intensity of particles was analyzed using Electrophoretic light scattering (ELS) technique. On the other hand, nanoparticle (NP) functional groups were estimated by Fourier Transformation Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR, Nicolet iS10, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) in the wavelength range of 700 cm-1 to 4000 cm-1 and for oily wastewater in the wavelength range of 1000 cm-1 to 4000 cm-1 under transmission mode. UV–vis absorption spectroscopy was performed on a Lambda 950 UV–vis spectrophotometer for the wavelength from 200 to 800 nm.

Furthermore, the physicochemical properties of the membranes were analysed by using ATR-FTIR, FESEM, AFM and contact angle. The morphologies of the surface and cross-section of fabricated membranes were characterized by using field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM, TESCON CLARA, Czech). High-resolution images, magnified up to 10,000 times (10kX), were captured under high vacuum conditions at an accelerating voltage of 15 kV. The razor blade was used to cut the membrane to obtain the cross-section image due to the presence of the fabric layer, liquid nitrogen cannot be used to cut the membranes. Membrane functional groups were estimated by Attenuated Total Reflectance-Fourier Transformation Infrared Spectroscopy (ATR-FTIR, Nicolet iS10, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) in the wavelength range of 500 cm-1 to 4000 cm-1 under transmission mode. The topological profiles of membranes were identified using atomic force microscopy (AFM, USPM NANONAVI, ESWEEP). Samples were cut into 1 cm × 1 cm pieces and attached to a flat glass slide for AFM scanning using contact mode. A 2 μm × 2 μm area was used for scanning.

A standard goniometer system was used with drop image advanced v2.5 (Rame-hart 260, USA) to measure the contact angle of the membranes in order to investigate the hydrophilicity of membranes. Each membrane sample was dried at room temperature for 24 h to ensure consistent surface conditions before testing. A drop of deionized water is placed on the surface of the membrane. The contact angle was measured immediately after placing the drop to ensure accuracy and minimize the effects of evaporation or absorption. The dynamic mechanical properties of composites films were.

studied with ASTM D638 analyser (TA Instruments, New Castle, USA). Tension mode was used, and the measurement was carried out on a rectangular shaped specimen with size of 0.5 mm × 0.25 mm × 0.190 mm at a speed rate of 5 mm/min.

Evaluation of the performance of membranes for oily wastewater treatment

The performance of the synthesized membranes was investigated using lab-scale crossflow FO mode, in which the active layer facing the feed solution, with an effective membrane area of 0.00427 m2. The oily wastewater (soybean oil emulsion) was used as feed solution. As soybean oil and industrial oily wastewater exhibit certain similarities, particularly in their lipid content and the challenges they present in wastewater treatment processes. Both, soybean oil and industrial oily wastewater pose challenges in wastewater treatment due to their high oil and grease content67. Similarly, they contain significant amounts of fats and fatty acids. Soybean oil is rich in triglycerides, primarily composed of unsaturated fatty acids such as oleic and linoleic acids. Similarly, industrial oily wastewater contains high concentrations of oils and greases, including various fatty acids68,69. The use of synthetic oily wastewater (soybean oil–water emulsion) is a common practice in membrane studies due to its reproducibility and controlled composition, which allows for consistent performance evaluation70,71. Meanwhile, NaCl solution (2 M) was used as draw solutions. Both solutions were transported into the membrane system by a peristaltic pump with an average flow velocity of 300 ml/min. The draw solution was weighed using a digital weight balance. The weight change was recorded over time to assess the performance of the membrane in terms of water flux or solute rejection. The conductivity of the feed solution was measured using a conductivity meter. Both water flux (Jw) and reverse solute flux (Js) were examined every 15 min for 3 times to calculate the average value by using Eqs. (1) and (2), respectively72.

|

1 |

|

2 |

where ∆V is the volume of permeated water (L), Am is the membrane area (m2), ∆t is the permeation time (h), and  C is the change in concentration of NaCl in the feed solution.

C is the change in concentration of NaCl in the feed solution.

The antifouling property was evaluated by the water flux recovery ratio (FRR, Eq. (3) 73), which was intended based on the pure water flux before and after the oily wastewater purification. The membranes were washed with pure water and the flux (Fo) was measured for 30 min. After treating the emulsified oily wastewater for 60 min, pure water was used to rinse the membranes for 30 min and the flux was restrained within this period and denoted by Fi51. The consecutive separation cycles were repeated three times to calculate the average FRR73.

|

3 |

Results and discussion

Characterization of nanoparticles

Zeta potential

The zeta potential of GO and PVP-GO particles are demonstrated in Table 4. Based on Table 4, the zeta potential for GO is – 21.3 mV, meanwhile, PVP-GO at optimum loading 0.035 wt% of PVP (PVP-GO-3) shows the highest value of zeta potential of – 41 mV. The negative charge of zeta potential increased by enhancing the concentration of PVP in the GO solution probably due to the presence of oxygen and hydroxyl groups produced by the reaction between PVP and GO54. This finding reveals higher stability of the PVP-GO aqueous solution than the GO aqueous solution. This enhanced stability can be attributed to the adsorption of PVP onto the surface of GO, which prevents the aggregation of GO nanoparticles52.

Table 4.

Zeta potential of aqueous solution containing nanoparticles.

| Aqueous solution | Zeta potential (mV) |

|---|---|

| GO | -27.3 |

| PVP-GO-1 | -36.1 |

| PVP-GO-2 | -37.9 |

| PVP-GO-3 | -41.0 |

UV–Vis spectroscopy

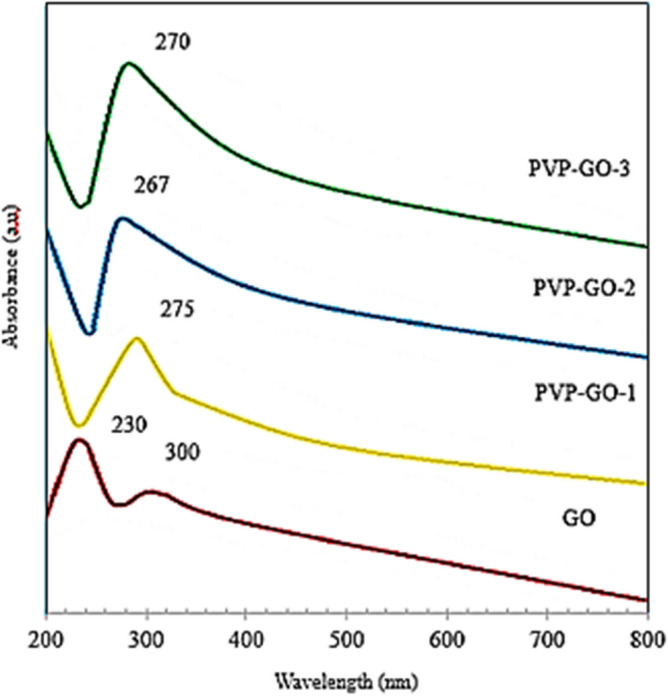

The successful functionalization of GO to PVP-GO nanoparticles is confirmed by UV–Vis spectroscopy analysis, as shown in Fig. 2. Based on Fig. 2. GO exhibits a distinct peak at approximately 230 nm, corresponding to the π-π* transition of the C–C bond. Additionally, a shoulder-like absorbance peak is observed around 300 nm, also attributed to π-π* transitions. In the PVP-GO spectra, the π-π* transition peak shifts to approximately 275 nm for PVP-GO-1, suggesting that the π-conjugated structure is partially restored due to the removal of oxygen-containing functional groups, confirming the successful loading of PVP onto the GO surface. Furthermore, the UV absorption peak of PVP-GO-2 appears around 267 nm with higher intensity, indicating a greater degree of GO reduction74. The intensity of the PVP-GO-1 absorbance peak is lower than that of the PVP-GO-2 and PVP-GO-3. The highest intensity is observed for PVP-GO-3 spectra at 270 nm, this phenomenon indicates that dispersion of modified GO is significantly upgraded in the presence of increasing concentration of PVP75,76.

Fig. 2.

UV–Vis spectra for GO, PVP-GO-1, PVP-GO-2, and PVP-GO-3 nanoparticles.

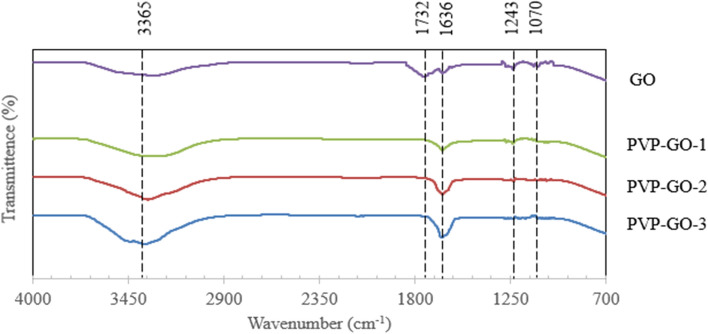

FTIR analysis

Figure 3 demonstrates the FTIR spectra of GO and PVP-GO. The spectrogram of GO nanoparticles (NP) representing the peak at 3365 cm−1 corresponding to structural O–H group stretching vibration, C = O carbonyl stretching at 1732 cm−1, the band at 1636 cm−1 represented the offerings from the vibration of aromatic C = C functional groups, C − O − C epoxy stretching vibration at 1243 cm−1 and the C − O alkoxy group stretching at 1070 cm−125,77. It is important to note that the peaks at 1732 cm−1, 1243 cm−1, 1070 cm−1 (in the pure GO) have disappeared in GO-PVP confirms that some of the oxygen containing groups of GO reacted with PVP54,77. The peaks of GO with PVP appeared at 1636 cm−1 and 3365 cm−1 to be more intense than those of GO. This higher peak intensity suggested the successful functionalization of GO by PVP58. The intensity of the above peaks is increased as the PVP content increased by 0.025 wt%, 0.030 wt% and 0.035 wt%. The change in intensity in the above peaks may be caused by the difference in the content of PVP in the GO solution31. Moreover, the observation that no new functional groups appeared in the analysis of PVP-GO composite membranes further supports the existence of strong π-π (pi-pi) interactions between graphene sheets and PVP55.

Fig. 3.

The FTIR spectrum for different nanoparticles.

FTIR of oil-in-water emulsion

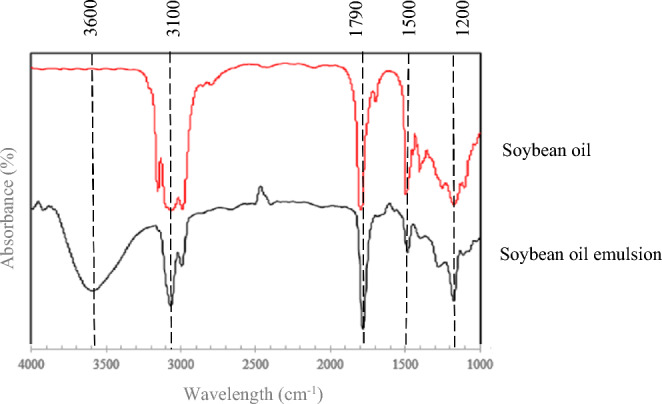

Figure 4 demonstrates the FTIR spectra of pure soybean oil and soybean oil emulsion. For pure soybean oil spectra, the spectrogram of ester groups appeared at 1200 cm-1 stretching vibration, alkene C = C functional groups representing the peak at 1500 cm−1, and C = O carboxylic acid functional group shown at 1790 cm−1 stretching. Furthermore, the band at 3100 cm-1 correspond to the symmetric and asymmetric stretching vibrations of –CH₂ and –CH₃ groups present in the fatty acid chains of soybean oil78. For soybean oil emulsion, broad band at 3600 cm-1 region is associated with hydroxyl groups from water and possible hydrogen bonding interactions in the emulsion59. A strong absorption band around 1790 cm-1 wavenumber is indicative of the ester carbonyl groups in triglycerides of soybean oil. The strong peak at 1200 cm-1 reflects the presence of sulphate groups from SDS, confirming the incorporation of the surfactant in the emulsion42,79.

Fig. 4.

FTIR of soybean oil and soybean oil emulsion.

Characterization of membranes

ATR-FTIR analysis

Figure 5, demonstrates the ATR-FTIR spectra of the membranes prepared in the present work. According to Fig. 5, it is observed that all membranes showed some typical peaks of polyamide membranes. The characteristic peaks at 1313 cm−1, 1236 cm−1, and 1147 cm−1 are attributed to the stretching vibration of asymmetric O = S = O, symmetric C–O–C, and O = S = O symmetric groups. The presence of these peaks confirms the successful incorporation of sulfur-containing components within the polyamide matrix42,79. The peak at 1407 cm−1 corresponds to the C-H symmetric deformation vibration of the -C(CH3)2 group. The detection of this peak indicates the presence of isopropyl groups within the polymer structure, contributing to the overall chemical stability and rigidity of membranes79. The peak at 1676 cm⁻1 (amide I) due to C = O stretching and 1584 cm⁻1 peak (amide II) indicates N–H bending, reflecting the amide bond formation in the polyamide structure66. The identification of these characteristic peaks serves as a confirmation of the successful formation of the polyamide layer through interfacial polymerization of MPD and TMC. It ensures that the intended chemical reactions have occurred, resulting in the desired membrane structure66,79.

Fig. 5.

ATR-FTIR of membranes fabricated in the present work.

As the membrane is incorporated with GO, the enhancement in absorbance of peaks at 1584 cm-1 and 1676 cm-1 in TFN membrane indicates the formation of more and new amide bonds due to the interaction of –COOH groups of GO with the amine (‒NH₂) groups of MPD41. The spectra of the modified membrane with GO at 1758 cm-1 shows more intensity than the unmodified TFC membrane due to the stretching vibration of C = O bonds of ester group, generated due to the reaction between GO and PA layer41,51. For the membranes incorporated with PVP-GO, the presence of more oxygen containing groups in PVP-GO solution leads the augmentation in the amide functional groups in TFN-1, TFN-2, and TFN-3 membranes. When GO is functionalized with PVP, additional oxygen-containing groups are introduced due to the chemical structure of PVP, which includes carbonyl groups. Pristine TFC and TFN membranes lack these additional oxygen-containing groups, resulting in lower transmittance intensity at 1758 cm−1. By increasing the amount of PVP, a narrower peak is observed in TFN-3 than in TFN-2 and TFN-1 ATR-FTIR spectra due to more oxygen-containing groups introduced after the interaction of PVP with GO. The peaks at 2971 cm⁻1 and 2851 cm⁻1 are typically assigned to the C‒H asymmetric and symmetric stretching vibrations of the C-H bonds in TFC41. Moreover, these characteristics peaks become more intense in TFN membranes due to the C-H bonds present in GO and PVP-GO. The appearance of the 3362 cm−1 peaks in the ATR-FTIR spectrum of the modified membranes, which is absent in the unmodified membrane, attributed to the OH functional groups that confirmed the occurrence of GO and PVP-GO on TFC58. In addition, by increasing the concentration of PVP, compared with the pristine TFC and TFN, the stronger absorption peak at 3362 cm−1 is observed for TFN-3 than for TFN-2 and TFN-1, which indicates that more dissociative hydroxyl groups are adsorbed on modified membrane surface due to higher hydrophilicity of grafted PVP-GO NPs51. This spectral evidence supports the conclusion that the modification process has introduced hydroxyl groups, which contribute to the enhanced performance characteristics of the modified membranes.

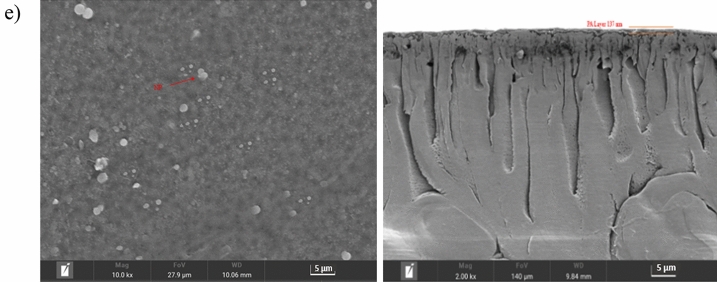

FESEM analysis

Figure 6 shows the FESEM images of the membranes fabricated in the present work. Based on Fig. 6, all fabricated membranes exhibited a slight ridge-and-valley surface on the top layer. This was attributed to the structural limitations of the porous support layer, which restricted the attachment of the aqueous phase solution, thereby slowing the interfacial polymerization reaction. As a result, the ridge-valley morphology and structural characteristics of the polyamide active selective layer were not distinctly visible80–83. TFC membrane without the presence of the nanoparticles, is shown, meanwhile, TFN membrane with the incorporation of GO particles without PVP is shown a severe agglomeration at the top of the surface25,36,81. TFC membrane without the presence of the nanoparticles, is shown a flat top surface, meanwhile, TFN membrane with the incorporation of GO particles without PVP is shown a severe agglomeration at the top of the surface. However, as the membranes are incorporated with PVP-GO nanoparticles as demonstrated in Fig. 6 (c), (d) and (e), it is noticed that there is less accumulation of PVP-GO nanoparticles on the membrane surface than GO nanoparticles. PVP, with its carbonyl and amide groups, can form hydrogen bonds with the carboxylic and hydroxylic groups present on the surface of graphene oxide55. These hydrogen bonds help to anchor the PVP molecules onto the GO surface, effectively preventing the graphene sheets from stacking together (aggregation)53. Furthermore, as the membrane is amalgamated with PVP-GO with increasing PVP loading, the scattering is improved and of the tendency for accumulation is reduced as compared to the membrane incorporated without PVP addition. This is due to the presence of strong π-π interactions and hydrogen bonds between GO and PVP to form a network in solution55.

Fig. 6.

(a) FESEM of cross-sections and top surfaces of (a) TFC, (b) TFN, (c) TFN-1, (d) TFN-2, and (e) TFN-3.

In addition, the measurement of thin film thickness using ImageJ revealed that the incorporation of GO and PVP-GO into TFC membranes results in significantly thinner layers. PA selective dense layer is well developed on the top of the TFC membranes resulting in a thicker top layer than modified membranes. This is due to the higher amount of MPD available for cross-linking with TMC, a thicker and rougher PA surface is formed. This increased availability of MPD leads to more extensive cross-linking, resulting in a denser and more textured membrane structure43. As compared to the TFC membrane, the incorporation of GO nanosheets introduces a hindrance effect and delays the diffusivity of MPD from the aqueous phase to the interface where it reacts with TMC in the organic phase. This hindrance effect results in a thinner interfacial polymerized skin layer25. This is due to the oxygen-containing functional groups in GO reacting with MPD and the carboxyl or hydroxyl groups interacting with the acyl chloride in TMC, thus affecting the reaction rate between MPD and TMC41. The decreased thickness is observed by adding PVP in GO aqueous solution due to the hydrogen bonding between PVP and GO which inhibits the diffusion of MPD and consequently decreased the thickness of the PA layer84. The observed thickness of 137.0 nm for TFN-3 made it the thinnest among the compared membranes: pristine TFC, TFN, TFN-1 and TFN-2 with 317.0 nm, 240.0 nm, 151.0 nm and 145.0 nm. This might be due to the more active site present on the PVP surface for making complexes including hydrogen bonds with GO which decreases the possibility of cross-linking structure growth of the network of MPD and TMC, leading to creation of thinner PA layer41,77,84. The reduction in the top layer thickness significantly lowers the mass transfer resistance, thereby contributing to the enhanced pure water flux41.

AFM analysis

AFM topography images of all the membranes are shown in Fig. 7. Table 5 illustrates the roughness parameters including mean roughness (Ra), root average square height (Rq), and average difference between the highest peaks and lowest valleys (Rz). According to Fig. 7, the ridge (brighter areas) and valley (darker areas) formations on the AFM images signify the presence of a polyamide layer on the polysulfone substrate. From Table 5, RMS for unmodified thin layer membrane (TFC) is calculated at 49.14 nm which conceivably decreased to 42.39, 17.40, 17.34, and 14.38 nm for TFN, TFN-1, TFN-2, and TFN-3 membranes, respectively. The roughness of the PA layer is decreased with the addition of nanoparticles showing the stabilized dispersion of synthesized nanoparticles. It can be seen that the unmodified FO membrane has higher roughness than modified FO membranes is due to the higher availability of MPD for cross-linking with TMC. The increased availability of MPD promotes more extensive cross-linking which enhances the structural complexity and surface characteristics of the membrane, contributing to its roughness43. It appears that the integration of GO inhibits the diffusion of MPD in the organic phase and modifies the surface morphology, making the convex parts smoother due to the hydrogen bonding between the functional groups of GO and PA film, hence enhancing the hydrophilicity of the membranes84,85. The inserted PVP layer helps smoothen the surface of the GO-PVP nanocomposite due to the high affinity of the GO and PVP components57,58. The surface roughness of the membrane decreases with increasing the concentration of PVP in GO aqueous solution. Specifically, the smoothest surface is achieved when the thin layer was prepared using 0.035 wt% PVP-GO. Increase in PVP concentration in GO solution reveals proper dispersion and distribution of NPs with the thin covering of TMC monomer layer on the surface. This tends to have increased the smoothness of the surface compared to control membrane86.

Fig. 7.

AFM images of prepared FO membranes.

Table 5.

AFM results of different synthesized membranes.

| Membrane | Ra (nm) | Rq (nm) | Rz (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| TFC | 34.93 | 49.14 | 267.20 |

| TFN | 29.02 | 42.39 | 242.10 |

| TFN-1 | 13.36 | 17.40 | 86.01 |

| TFN-2 | 12.38 | 17.34 | 69.14 |

| TFN-3 | 10.80 | 14.38 | 50.04 |

Mechanical properties

To evaluate the mechanical properties of the membranes, the tensile strength was determined for all fabricated membranes, as illustrated in Fig. 8. The pristine TFC membrane displayed a tensile strength of 12.45 MPa, whereas the GO-decorated TFN membrane exhibited an improved tensile strength of 18.93 MPa. This enhancement is primarily due to the superior mechanical properties of GO particles incorporated into the polymer matrix, which reinforce the membrane structure, as depicted in Fig. 8. Graphene possesses an exceptional tensile strength of 130 GPa. However, graphene oxide (GO) has a tensile strength of 87.9 MPa, primarily due to variations in the distribution of oxygen functional groups87. The incorporation of GO enhances the mechanical strength and stiffness of polymer composites. When PVP is introduced alongside GO, both tensile strength and elongation exhibit further improvement. Among the tested membranes, the TFN-3 FO membrane demonstrates the highest tensile strength, reaching 22.16 MPa, surpassing that of TFN-2 and TFN-1. This enhancement is attributed to the uniform dispersion of PVP-modified GO within the polymer matrix. Consequently, the integration of PVP-GO nanofillers into TFC membrane enhances its ability to endure applied stress during water filtration, preventing the collapse of its porous structure. These findings suggest that the specific interactions between GO, PVP, and the polymer matrix play a crucial role in improving the tensile elongation of PSf-based nanocomposite membranes87,88.

Fig. 8.

Tensile strength of TFC, TFN, TFN-1, TFN-2, and TFN-3 FO membranes.

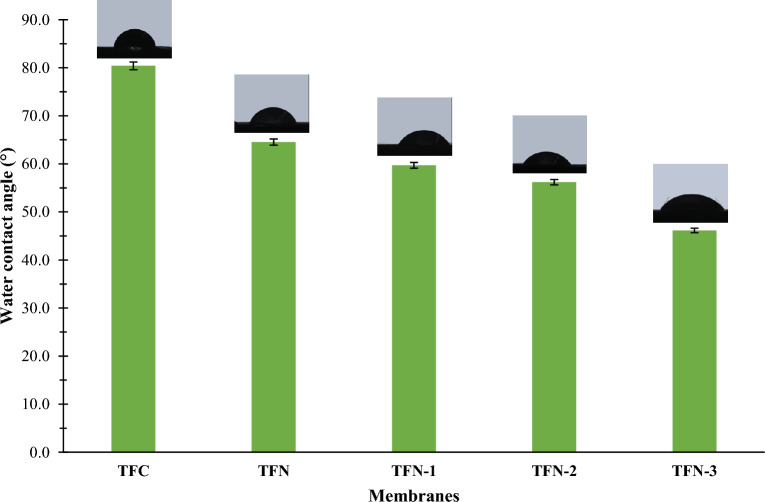

Water contact angle analysis

Figure 9 shows the water contact angles of membranes fabricated in the present work. According to Fig. 9, the contact angle of TFN-embedded GO was lower than pristine TFC. This is because graphene oxide itself possesses hydrophilic functional groups such as hydroxyl (-OH) and carboxyl (-COOH) groups, which promote its interaction with water molecules39. These functional groups increase the surface energy of GO, making it more hydrophilic and enhancing its affinity for water85. For TFN membranes with PVP-GO, the effect of PVP in GO solution significantly enhances the hydrophilicity of membranes49. This improvement is attributed to the presence of hydroxyl functional groups in GO and the water-soluble nature of PVP49. The PVP molecules can interact with water molecules via hydrogen bonding and other interactions, effectively increasing the overall hydrophilicity of the membrane85. The observed decrease in contact angles with increasing concentrations of PVP in PVP-GO composite membranes from 59.70° to 46.14° for 0.025 wt% PVP-GO (TFN-1) to 0.035 wt% PVP-GO (TFN-3) membranes, respectively, demonstrates the enhancement of hydrophilicity. This is due to the increase in hydroxyl functional groups of PVP-modified GO, which are confirmed by the ATR-FTIR results, shown in Fig. 5.

Fig. 9.

Water contact angle of membranes incorporated with GO and PVP-G.

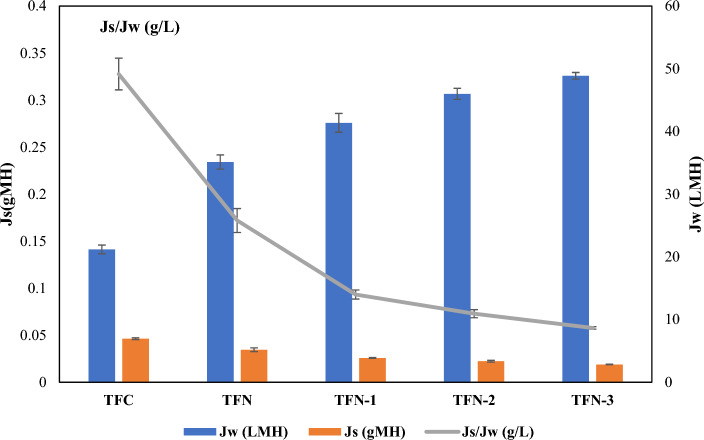

FO performance evaluation

Soybean oil-in-water emulsion as feed solution, prepared by first dissolving sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) in 1 L of deionized water. The synthetic oily wastewater used in this study was prepared based on a well-established formulation from the literature89, which reports a mean oil droplet size of 226.7 nm and a zeta potential of − 69.4 mV. Figure 10 represents the flux performance Jw and Js of different synthesized membranes. Based on Fig. 10, all TFN membranes incorporated with GO and PVP-GO demonstrate enhanced water fluxes as compared to the TFC membrane without the addition of fillers. This indicates that both GO and PVP-GO are effective modifiers for improving water flux in FO membranes. The water flux for GO membrane with the addition of 0.0175 wt% of GO into the MPD solution, resulting in a 38.114 L/m2.hr (LMH). This is because GO provides two-dimensional (2D) nanochannels that enhance both water transport and hydrophilicity in membranes72. In addition, as PVP is combined with GO to form a composite membrane, it further contributes to the hydrophilicity of the membrane due to its inherent hydrophilic nature85. For PVP-GO modified TFN membranes, PVP, being hydrophilic, increases the hydrophilicity of a membrane surface and hence increases the water flux owing increased hydrogen bonding with GO49.

Fig. 10.

FO performance of prepared TFC, TFN, TFN-1, TFN-2, and TFN-3 FO membranes.

Under the same operating conditions, the TFN-3 membrane exhibits the highest water flux with 48.871 LMH as compared to the TFC, TFN, TFN-1 and TFN-2 with water flux of 21.181 LMH, 35.114 LMH, 41.363 LMH, and 45.988 LMH. It has been reported that PVP attracts water molecules, thereby increasing the relative hydrophilicity as well as the improved hydrophilicity introduced by the increased hydrophilic functional groups on the surface of GO49. Additionally, the thinnest polyamide layer of the TFN-3 FO membrane is a critical factor in enhancing the water fluxes84. This improvement is likely due to enhancements in both hydrophilicity and dispersibility of PVP-GO in TFN-3 than TFN-2 and TFN-1. Moreover, membrane roughness plays a significant role in its hydrophilicity by fouling resistance, both in terms of biofouling (deposition of biological materials) and general fouling (deposition of non-biological materials). A membrane with a low roughness, having a uniform and smooth surface, tends to exhibit stronger anti-fouling and anti-biofouling properties86. When a membrane has a rough surface, it provides more sites for foulants to adhere to, thereby increasing the likelihood of fouling and decreasing the water flux. In contrast, a smooth and uniform surface reduces the number of available sites for foulants to attach to, making it more difficult for them to adhere and form a fouling layer ultimately increases the water flux90.

Furthermore, as shown in Table 5, TFN-3 membrane shown the lowest value of Ra, Rq and Rs, which support the highest increment of water flux for this membrane. Based on Fig. 10, the membrane loaded with GO nanoparticles demonstrates the reduction of reverse salt flux (Js) flux to 4.035 g/m2.hr (gMH) as compared to unmodified membrane, TFC with reverse solute flux of 6.942 gMH. This phenomenon is due to the improved interaction of NPs with the PA layer and hence attained the proper cross-linking degree of the selective layer91. The mechanisms underlying this improvement include that the PVP modification enhances the dispersibility of GO nanosheets within the membrane matrix, preventing aggregation. This uniform distribution leads to a more consistent and defect-free selective layer, which is crucial for maintaining selective ion rejection and thereby reducing reverse salt flux. As it is a hydrophilic polymer that, when grafted onto GO, increases the overall hydrophilicity of the membrane surface. This enhancement facilitates the formation of a stable hydration layer, which acts as a barrier to salt ions and oil, effectively decreasing their passage through the membrane and thus enhanced salt rejection and oil rejection. The interaction between PVP and the membrane polymer matrix improves compatibility, leading to better structural integrity. This compatibility ensures that the membrane maintains its selective properties under operational conditions61. Hence, by adding PVP in GO solution, the water flux is increased by increasing the hydrophilicity, it allows more water to pass across the membrane which allows less salt to counter diffuse across the membrane as well as the high rejection of oil.

Furthermore, Fig. 10. shows the ratio of reverse salt flux and water flux. The ratio of reverse solute flux to water flux is another critical factor for evaluating the performance of FO membranes. Based on Fig. 9, higher ratios indicate a greater amount of salt moving from the draw solution to the feed solution76. As compared to TFC, TFN, TFN-1, and TFN-2 with Js/Jw such as 0.3277 g/L, 0.172 g/L, 0.0933 g/L, 0.0729 g/L reductions could be observed. Especially, when the concentration of PVP is 0.035 wt%, the Js/Jw of PVP-GO-FO membrane is at a minimum with 0.0577 g/L. This is potentially associated with enhancements in both the hydrophilicity and the dispersibility of PVP-GO. The enhancement of water fluxes is observed in membranes containing GO and PVP-GO is often attributed to the improved hydrophilicity introduced by the hydrophilic functional groups present on the surface of GO and within the PVP-GO composite85. By introducing more hydrophilic functional groups around the surface of GO by increasing PVP amount within the PVP-GO composite, the membrane becomes more favourable for water molecules to interact. Overall, the use of membranes containing GO and PVP-GO, with their enhanced hydrophilicity and improved water fluxes, holds great promise for advancing water treatment technologies and addressing global water scarcity challenges.

Antifouling performance evaluation

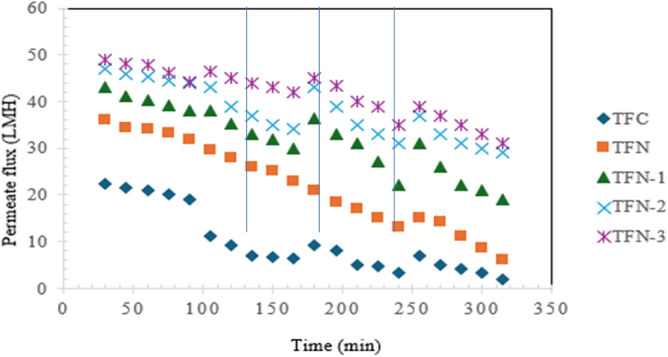

Figure 11. illustrates the antifouling properties of both pristine and modified membranes during oily wastewater filtration. In addition to membrane permeability, the flux recovery rate (FRR) is a crucial parameter for assessing a membrane antifouling capability and long-term stability in practical applications. The dynamic fouling test evaluated the permeation performance of the FO membranes through multiple filtration cycles. During the first filtration cycle, a comparison of pure water flux over the initial 30 min revealed that the modified membranes exhibited significantly higher permeability than the pristine membrane. However, after 60 min of oily wastewater filtration, the permeability of the pristine TFC membrane sharply declined to approximately 35% of its initial water flux. Notably, the pristine TFC membrane abortive to fully recover its original flux after each washing cycle. This was primarily attributed to the adhesion of hydrophobic protein foulants on the membrane surface and the subsequent concentration polarization, which led to pore blockage.

Fig. 11.

Antifouling performance of prepared TFC, TFN, TFN-1, TFN-2, and TFN-3 FO membranes (vertical lines indicate cycle after washing).

After three filtration cycles, the FRR values of the TFC, TFN, TFN-1, TFN-2, and TFN-3 membranes were recorded as 60.3%, 71.8%, 83.9%, 86.5%, and 88.6%, respectively, highlighting the enhanced antifouling performance of the modified membranes. TFN-3 exhibited the highest fouling resistance and a high flux recovery ratio (FRR), attributed to the presence of functionalized GO with PVP. This suggests that the well-dispersed PVP-GO-3 nanocomposite membrane enhanced both water permeability and antifouling properties of the TFC FO membrane. Based on Fig. 11, it can be observed that during operation, the formation of a fouling layer on the membrane surface increases hydraulic resistance, leading to a decline in flux73. Overall, the grafting of hydrophilic PVP-GO significantly improved the hydrophilicity of the TFC membrane surface while also forming an interfacial hydration layer that acts as a protective barrier. This barrier helps mitigate interactions between hydrophobic foulants and the membrane surface, preventing pore blockage. Additionally, the presence of the PVP-GO layer, characterized by low surface energy and lubricating properties, facilitated easier cleaning of the modified TFN membranes through a simple water-washing process, leading to a higher flux recovery ratio (FRR)51,73,92.

Contact angle measurements and flux recovery analysis reveal that the oil rejection mechanism is strongly influenced by the membrane physicochemical modifications. The presence of PVP helps control the pore size distribution which allows water molecules to pass through while retaining larger oil droplets. Also, PVP is highly hydrophilic and introduces polar functional groups (carbonyl and amide) on the membrane surface, this promotes water permeability while repelling hydrophobic oil droplets, thus reducing fouling22,48. The GO nanosheets also contribute hydrophilic oxygen-containing groups (e.g., hydroxyl, carboxyl), which improve wettability and reduce oil adsorption24,33. GO and PVP-modified surfaces generally carry negative surface charges, provided in Table 4. Soybean oil droplets, stabilized by surfactants (SDS), are also negatively charged. This leads to electrostatic repulsion, preventing oil droplets from depositing or penetrating the membrane. Since FO is osmotic pressure driven, the draw solution (brine) pulls water across the membrane, leaving oil and other contaminants in the FS. The direction of water flux (from FS to DS) helps in minimizing the transport of oil or foulants into the active layer.

Conclusion

In this study, PVP-modified GO forward osmosis membranes were synthesized to evaluate their effectiveness in oily wastewater treatment. The optimal membrane, TFN-3 (0.035 wt% PVP-GO), exhibited superior properties, including a higher absolute zeta potential (-41.0 mV vs. -21.3 mV for unmodified GO), confirming improved dispersion and reduced aggregation. ATR-FTIR analysis verified successful functionalization, while FESEM and AFM results showed reduced polyamide layer thickness (137.0 nm) and a smoother surface (14.38 nm RMS). Therefore, this finding contributes to increase the performance of membrane. The lowest water contact angle (46.14°) indicated enhanced hydrophilicity, contributing to the highest water flux (48.871 LMH) and minimal Js/Jw (0.0396 g/L). The developed membrane shows potential for improving oily wastewater treatment efficiency by improved hydrophilicity also enhanced antifouling performance, reducing cleaning frequency, chemical costs, and environmental impact. Future work will aim to further enhance the membrane fouling resistance, supporting its use in industrial applications. With increased permeability, the PVP-GO membrane could become a practical and effective solution for real-world oily wastewater treatment.

Acknowledgements

The technical support received from Center of Carbon Capture, Utilisation and Storage (CCCUS), Institute of Sustainable Energy and Resources (ISER) is duly acknowledged.

Author contributions

H.B.; Formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing original draft, visualization. N.J; Con-ceptualization, methodology, writing-review and editing, supervision, funding acquisition, project administration. N.H.S; writing-review and editing, visualization.

Funding

The YUTP Research Grant (Cost centers: 015LCO-270 and 015LCO-505) has supported the financial parts of this work.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Shahriari, H. R. & Hosseini, S. S. Experimental and statistical investigation on fabrication and performance evaluation of structurally tailored PAN nanofiltration membranes for produced water treatment. Chem. Eng. Process. - Process Intensif.147, 107766. 10.1016/j.cep.2019.107766 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yue, X., Li, Z., Zhang, T., Yang, D. & Qiu, F. Design and fabrication of superwetting fiber-based membranes for oil/water separation applications. Chem. Eng. J.364, 292–309. 10.1016/j.cej.2019.01.149 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang, S., Ras, R. H. A. & Tian, X. Antifouling membranes for oily wastewater treatment: Interplay between wetting and membrane fouling. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci.36, 90–109. 10.1016/j.cocis.2018.02.002 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xu, Y., Zhu, Y., Chen, Z., Zhu, J. & Chen, G. A comprehensive review on forward osmosis water treatment: Recent advances and prospects of membranes and draw solutes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health19(13), 8215 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yadav, S. et al. Recent developments in forward osmosis membranes using carbon-based nanomaterials. Desalination482, 114375. 10.1016/j.desal.2020.114375 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sutrisna, P. D., Kurnia, K. A., Siagian, U. W., Ismadji, S. & Wenten, I. G. Membrane fouling and fouling mitigation in oil–water separation: A review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng.10(3), 107532 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peng, Y. et al. A novel reduced graphene oxide-based composite membrane prepared via a facile deposition method for multifunctional applications: oil/water separation and cationic dyes removal. Sep. Purif. Technol.200, 130–140. 10.1016/j.seppur.2018.01.059 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Munirasu, S., Haija, M. A. & Banat, F. Use of membrane technology for oil field and refinery produced water treatment—A review. Process Saf. Environ. Prot.100, 183–202. 10.1016/j.psep.2016.01.010 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu, X., Yang, Y., Liu, T. & Chu, B. Cost-effective polymer-based membranes for drinking water purification. Giant10, 100099. 10.1016/j.giant.2022.100099 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li, J.-J., Zhou, Y.-N. & Luo, Z.-H. Polymeric materials with switchable superwettability for controllable oil/water separation: A comprehensive review. Prog. Polym. Sci.87, 1–33. 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2018.06.009 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abbas, T. K. et al. Decontamination-of-Aqueous-Nuclear-Waste-via-Pressure-driven-Membrane-Application-A-Short-Review. Eng. Technol. J.41(9), 1152–1174 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahmad, N. A., Goh, P. S., Abdul Karim, Z. & Ismail, A. F. Thin film composite membrane for oily waste water treatment: Recent advances and challenges. Membranes8(4), 86 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yalcinkaya, F., Boyraz, E., Maryska, J. & Kucerova, K. A Review on Membrane Technology and Chemical Surface Modification for the Oily Wastewater Treatment. Materials13(2), 493. 10.3390/ma13020493 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chao, G. et al. A Review of Ultrafiltration and Forward Osmosis:application and modification. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci.128, 012150. 10.1088/1755-1315/128/1/012150 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu, L., Yang, T., Li, M., Chang, J. & Xu, J. Thin-film nanocomposite membrane doped with carboxylated covalent organic frameworks for efficient forward osmosis desalination. J. Membr. Sci.610, 118111. 10.1016/j.memsci.2020.118111 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zheng, K., Zhou, S. & Zhou, X. A low-cost and high-performance thin-film composite forward osmosis membrane based on an SPSU/PVC substrate. Sci. Rep.8(1), 10022. 10.1038/s41598-018-28436-4 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hassan Arafat, ‘Desalination Sustainability, A Technical, Socioeconomic, and Environmental Approach, Masdar Institute of Science and Technology, Abu Dhabi, ISBN: 978–0–12–809791–5

- 18.Xu, G.-R., Xu, J.-M., Feng, H.-J., Zhao, H.-L. & Wu, S.-B. Tailoring structures and performance of polyamide thin film composite (PA-TFC) desalination membranes via sublayers adjustment-a review. Desalination417, 19–35. 10.1016/j.desal.2017.05.011 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Esfahani, M. R. et al. Nanocomposite membranes for water separation and purification: Fabrication, modification, and applications. Sep. Purif. Technol.213, 465–499. 10.1016/j.seppur.2018.12.050 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berber, M. R. Current Advances of Polymer Composites for Water Treatment and Desalination. J. Chem.2020, 1–19. 10.1155/2020/7608423 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Junaidi, N. F. D. et al. Recent development of graphene oxide-based membranes for oil–water separation: A review. Sep. Purif. Technol.258, 118000. 10.1016/j.seppur.2020.118000 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zahid, M., Rashid, A., Akram, S., Rehan, Z. A. & Razzaq, W. A Comprehensive Review on Polymeric Nano-Composite Membranes for Water Treatment. J. Membr. Sci. Technol10.4172/2155-9589.1000179 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Noamani, S., Niroomand, S., Rastgar, M. & Sadrzadeh, M. Carbon-based polymer nanocomposite membranes for oily wastewater treatment. Npj Clean Water2(1), 20. 10.1038/s41545-019-0044-z (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thines, R. K. et al. Application potential of carbon nanomaterials in water and wastewater treatment: A review. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng.72, 116–133. 10.1016/j.jtice.2017.01.018 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ali, M. E. A., Wang, L., Wang, X. & Feng, X. Thin film composite membranes embedded with graphene oxide for water desalination. Desalination386, 67–76. 10.1016/j.desal.2016.02.034 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abdul-Hussein, S. T. et al. Systematic investigation of MAX phase (Ti3AlC2) modified polyethersulfone membrane performance for forward osmosis applications in desalination. Arab. J. Chem.17(1), 105475. 10.1016/j.arabjc.2023.105475 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ihsanullah, I. & Bilal, M. Potential of MXene-based membranes in water treatment and desalination: A critical review. Chemosphere303, 135234. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.135234 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kallem, P. et al. High-performance thin-film composite forward osmosis membranes with hydrophilic PDA@TiO2 nanocomposite substrate for the treatment of oily wastewater under PRO mode. J. Environ. Chem. Eng.10(3), 107454. 10.1016/j.jece.2022.107454 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beh, J. J., Ooi, B. S., Lim, J. K., Ng, E. P. & Mustapa, H. Development of high water permeability and chemically stable thin film nanocomposite (TFN) forward osmosis (FO) membrane with poly(sodium 4-styrenesulfonate) (PSS)-coated zeolitic imidazolate framework-8 (ZIF-8) for produced water treatment. J. Water Process Eng.33, 101031. 10.1016/j.jwpe.2019.101031 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moeinzadeh, R., Jadval Ghadam, A. G., Lau, W. J. & Emadzadeh, D. Synthesis of nanocomposite membrane incorporated with amino-functionalized nanocrystalline cellulose for refinery wastewater treatment. Carbohydr. Polym.225, 115212. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2019.115212 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sun, W. et al. A review on organic–inorganic hybrid nanocomposite membranes: A versatile tool to overcome the barriers of forward osmosis. RSC Adv.8(18), 10040–10056. 10.1039/c7ra12835e (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Amini, M., Jahanshahi, M. & Rahimpour, A. Synthesis of novel thin film nanocomposite (TFN) forward osmosis membranes using functionalized multi-walled carbon nanotubes. J. Membr. Sci.435, 233–241. 10.1016/j.memsci.2013.01.041 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Niksefat, N., Jahanshahi, M. & Rahimpour, A. The effect of SiO2 nanoparticles on morphology and performance of thin film composite membranes for forward osmosis application. Desalination343, 140–146. 10.1016/j.desal.2014.03.031 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morales-Torres, S., Esteves, C. M. P., Figueiredo, J. L. & Silva, A. M. T. Thin film composite forward osmosis membranes based on polysulfone supports blended with nanostructured carbon materials. J. Membr. Sci.520, 326–336. 10.1016/j.memsci.2016.07.009 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bassyouni, M., Abdel-Aziz, M. H., Zoromba, MSh., Abdel-Hamid, S. M. S. & Drioli, E. A review of polymeric nanocomposite membranes for water purification. J. Ind. Eng. Chem.73, 19–46. 10.1016/j.jiec.2019.01.045 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu, W., Shi, Y., Liu, G., Fan, X. & Yu, Y. Recent development of graphene oxide based forward osmosis membrane for water treatment: A critical review. Desalination491, 114452. 10.1016/j.desal.2020.114452 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 37.He, L. et al. Promoted water transport across graphene oxide–poly(amide) thin film composite membranes and their antibacterial activity. Desalination365, 126–135. 10.1016/j.desal.2015.02.032 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu, L. et al. Aggregation Kinetics of Graphene Oxides in Aqueous Solutions: Experiments, Mechanisms, and Modeling. Langmuir29(49), 15174–15181. 10.1021/la404134x (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li, Z. et al. Effect of functional groups on the agglomeration of graphene in nanocomposites. Compos. Sci. Technol.163, 116–122. 10.1016/j.compscitech.2018.05.016 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim, C., Lee, J., Wang, W. & Fortner, J. Organic Functionalized Graphene Oxide Behavior in Water. Nanomaterials10.3390/nano10061228 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Akther, N. et al. Influence of graphene oxide lateral size on the properties and performances of forward osmosis membrane’. Desalination484, 114421. 10.1016/j.desal.2020.114421 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xia, S., Yao, L., Zhao, Y., Li, N. & Zheng, Y. Preparation of graphene oxide modified polyamide thin film composite membranes with improved hydrophilicity for natural organic matter removal. Chem. Eng. J.280, 720–727. 10.1016/j.cej.2015.06.063 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saeedi-Jurkuyeh, A., Jafari, A. J., Kalantary, R. R. & Esrafili, A. A novel synthetic thin-film nanocomposite forward osmosis membrane modified by graphene oxide and polyethylene glycol for heavy metals removal from aqueous solutions. React. Funct. Polym.146, 104397. 10.1016/j.reactfunctpolym.2019.104397 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lai, G. S. et al. A novel interfacial polymerization approach towards synthesis of graphene oxide-incorporated thin film nanocomposite membrane with improved surface properties. Arab. J. Chem.12(1), 75–87. 10.1016/j.arabjc.2017.12.009 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sahu, A., Dosi, R., Kwiatkowski, C., Schmal, S. & Poler, J. C. Advanced Polymeric Nanocomposite Membranes for Water and Wastewater Treatment: A Comprehensive Review. Polymers10.3390/polym15030540 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yassari, M., Shakeri, A., Salehi, H. & Razavi, S. R. Enhancement in forward osmosis performance of thin-film nanocomposite membrane using tannic acid-functionalized graphene oxide. J. Polym. Res.29(2), 43. 10.1007/s10965-022-02894-x (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ibrar, I. et al. A Review of Fouling Mechanisms, Control Strategies and Real-Time Fouling Monitoring Techniques in Forward Osmosis. Water11(4), 695. 10.3390/w11040695 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Junaidi, N. F. D. et al. Effect of graphene oxide (GO) and polyvinylpyrollidone (PVP) additives on the hydrophilicity of composite polyethersulfone (PES) membrane. Malays. J. Fundam. Appl. Sci.15(3), 361–366 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li, X. et al. Graphene/thermoplastic polyurethane nanocomposites: Surface modification of graphene through oxidation, polyvinyl pyrrolidone coating and reduction. Compos. A Appl. Sci. Manuf.68, 264–275 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu, W. et al. Enhanced MPBR with polyvinylpyrrolidone-graphene oxide/PVDF hollow fiber membrane for efficient ammonia nitrogen wastewater treatment and high-density Chlorella cultivation. Chem. Eng. J.379, 122368. 10.1016/j.cej.2019.122368 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang, L. et al. High-selective and sensitive voltammetric sensor for butylated hydroxyanisole based on AuNPs–PVP– graphene nanocomposites. Talanta138, 169–175. 10.1016/j.talanta.2015.01.016 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang, X. et al. Polyvinyl pyrrolidone modified graphene oxide for improving the mechanical, thermal conductivity and solvent resistance properties of natural rubber. RSC Adv.6(60), 54668–54678. 10.1039/C6RA11601A (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Su, Q.-W., Lu, H., Zhang, J.-Y. & Zhang, L.-Z. Fabrication and analysis of a highly hydrophobic and permeable block GO-PVP/PVDF membrane for membrane humidification-dehumidification desalination. J. Membr. Sci.582, 367–380. 10.1016/j.memsci.2019.04.023 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gao, B., Kalulu, M., Oderinde, O., Mei, J. & Ren, L. “Synthesis of three-dimensional graphene architectures by using an environmental-friendly surfactant as a reducing agent”,nt. J. Hydrog. Energy42(29), 18196–18202. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2017.04.159 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Akther, N., Ali, S. M., Phuntsho, S. & Shon, H. Surface modification of thin-film composite forward osmosis membranes with polyvinyl alcohol–graphene oxide composite hydrogels for antifouling properties. Desalination491, 114591. 10.1016/j.desal.2020.114591 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kim, W. K., Wu, C. & Kim, T. W. Effect of a PEDOT:PSS modified layer on the electrical characteristics of flexible memristive devices based on graphene oxide:polyvinylpyrrolidone nanocomposites. Appl. Surf. Sci.444, 65–70. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2018.03.035 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rana, A. et al. Functionalized graphene oxide based nanocarrier for enhanced cytotoxicity of Juniperus squamata root essential oil against breast cancer cells. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol.72, 103370. 10.1016/j.jddst.2022.103370 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 58.Poolachira, S. & Velmurugan, S. Efficient removal of lead ions from aqueous solution by graphene oxide modified polyethersulfone adsorptive mixed matrix membrane. Environ. Res.210, 112924. 10.1016/j.envres.2022.112924 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li, Y., Yang, Y., Li, C. & Hou, L. Comparison of performance and biofouling resistance of thin-film composite forward osmosis membranes with substrate/active layer modified by graphene oxide. RSC Adv.9(12), 6502–6509. 10.1039/C8RA08838A (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wu, X., Field, R. W., Wu, J. J. & Zhang, K. Polyvinylpyrrolidone modified graphene oxide as a modifier for thin film composite forward osmosis membranes. J. Membr. Sci.540, 251–260. 10.1016/j.memsci.2017.06.070 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vatsha, B., Ngila, J. C. & Moutloali, R. M. Preparation of antifouling polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP 40K) modified polyethersulfone (PES) ultrafiltration (UF) membrane for water purification. Phys. Chem. Earth, Parts A/B/C67–69, 125–131. 10.1016/j.pce.2013.09.021 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ochoa, N. A. et al. Pore size distributions based on AFM imaging and retention of multidisperse polymer solutes: Characterisation of polyethersulfone UF membranes with dopes containing different PVP. J. Membr. Sci.187(1), 227–237. 10.1016/S0376-7388(01)00348-9 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 63.Marchese, J. et al. Fouling behaviour of polyethersulfone UF membranes made with different PVP. J. Membr. Sci.211(1), 1–11. 10.1016/S0376-7388(02)00260-0 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 64.Al Malek, S. A., Abu Seman, M. N., Johnson, D. & Hilal, N. Formation and characterization of polyethersulfone membranes using different concentrations of polyvinylpyrrolidone. Desalination288, 31–39. 10.1016/j.desal.2011.12.006 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cheng, B. et al. Preparation and characterization of novel thin film composite forward osmosis membrane with halloysite nanotube interlayer. Polymer254, 125096. 10.1016/j.polymer.2022.125096 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 66.Davarnejad, R., Sabzehei, M., Parvizi, F., Heidari, S. & Rashidi, A. Chemical Engineering & Technology, Study on Soybean Oil Plant Wastewater Treatment Using the Electro-Fenton Technique. Chem. Eng. Technol.10.1002/ceat.201800765 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 67.Welz, P., Swanepoel, G., Weels, S. & Le Roes-Hill, M. Wastewater from the Edible Oil Industry as a Potential Source of Lipase- and Surfactant-Producing Actinobacteria. Microorganisms.9(9), 1987. 10.3390/microorganisms9091987.PMID:34576882;PMCID:PMC8465459 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pathe, P. P., Nandy, T. & Kaul, S. N. Wastewater management in vegetable oil industries. Indian J. Environ. Prot.20, 481–492 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 69.Elhady, S. et al. Oily Wastewater Treatment Using Polyamide Thin Film Composite Membrane Technology. Membranes10, 84. 10.3390/membranes10050084 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Li, P. et al. Short- and Long-Term Performance of the Thin-Film Composite Forward Osmosis (TFC-FO) Hollow Fiber Membranes for Oily Wastewater Purification. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res.53(36), 14056–14064. 10.1021/ie502365p (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 71.Choi, H., Shah, A. A., Nam, S.-E., Park, Y.-I. & Park, H. Thin-film composite membranes comprising ultrathin hydrophilic polydopamine interlayer with graphene oxide for forward osmosis. Desalination449, 41–49. 10.1016/j.desal.2018.10.012 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 72.Alammar, A., Park, S.-H., Williams, C. J., Derby, B. & Szekely, G. Oil-in-water separation with graphene-based nanocomposite membranes for produced water treatment. J. Membr. Sci.603, 118007. 10.1016/j.memsci.2020.118007 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhi, X. et al. The immunotoxicity of graphene oxides and the effect of PVP-coating. Biomaterials34(21), 5254–5261. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.03.024 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhang, X. et al. Multifunctional nanocomposites between natural rubber and polyvinyl pyrrolidone modified graphene. Compos. B Eng.84, 121–129. 10.1016/j.compositesb.2015.08.077 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 75.Uddin, Md. E., Layek, R. K., Kim, N. H., Hui, D. & Lee, J. H. Preparation and properties of reduced graphene oxide/polyacrylonitrile nanocomposites using polyvinyl phenol. Compos. B Eng.80, 238–245. 10.1016/j.compositesb.2015.06.009 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 76.Du, R. et al. PVP modified rGO/CoFe2O4 magnetic adsorbents with a unique sandwich structure and superior adsorption performance for anionic and cationic dyes. Sep. Purif. Technol.286, 120484. 10.1016/j.seppur.2022.120484 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 77.Taheri, R., Kosasih, B., Zhu, H. & Tieu, A. K. Surface Film Adsorption and Lubricity of Soybean Oil In-Water Emulsion and Triblock Copolymer Aqueous Solution: A Comparative Study. Lubricants5, 1. 10.3390/lubricants5010001 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nie, Y., Xie, C. & Wang, Y. Preparation and Characterization of the Forward Osmosis Membrane Modified by MXene Nano-Sheets. Membranes12(2), 146. 10.3390/membranes12020146 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rastgar, M., Shakeri, A., Bozorg, A., Salehi, H. & Saadattalab, V. Highly efficient forward osmosis membrane tailored by magnetically responsive graphene oxide/Fe3O4 nanohybrid. Appl. Surf. Sci.441, 923–935. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2018.02.118 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rezaei-DashtArzhandi, M. et al. Development of novel thin film nanocomposite forward osmosis membranes containing halloysite/graphitic carbon nitride nanoparticles towards enhanced desalination performance. Desalination447, 18–28. 10.1016/j.desal.2018.08.003 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 81.Klaysom, C., Hermans, S., Gahlaut, A., Van Craenenbroeck, S. & Vankelecom, I. F. J. Polyamide/Polyacrylonitrile (PA/PAN) thin film composite osmosis membranes: Film optimization, characterization and performance evaluation. J. Membr. Sci.445, 25–33. 10.1016/j.memsci.2013.05.037 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 82.Li, J., Wei, M. & Wang, Y. Substrate matters: The influences of substrate layers on the performances of thin-film composite reverse osmosis membranes. Chin. J. Chem. Eng.25(11), 1676–1684. 10.1016/j.cjche.2017.05.006 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 83.Izadmehr, N., Mansourpanah, Y., Ulbricht, M., Rahimpour, A. & Omidkhah, M. R. TETA-anchored graphene oxide enhanced polyamide thin film nanofiltration membrane for water purification; performance and antifouling properties. J. Environ. Manage.276, 111299. 10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.111299 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Chang, X. et al. Exploring the synergetic effects of graphene oxide (GO) and polyvinylpyrrodione (PVP) on poly(vinylylidenefluoride) (PVDF) ultrafiltration membrane performance. Appl. Surf. Sci.316, 537–548. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2014.07.202 (2014). [Google Scholar]