Abstract

Introduction

Thyroid dysfunction alters bone metabolism and is associated with osteoporosis. Since periodontitis involves alveolar bone loss, and thyroid disorders may impair immune regulation as well as bone remodeling, we hypothesized that thyroid hormone (TH) levels could predict the risk and severity of periodontitis. However, this potential association remains understudied to date.

Methods

This study utilized cross-sectional data from the 2009-2010 and 2011-2012 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) cycles, comprising 2352 eligible participants: 704 without periodontitis and 1648 with periodontitis. We analyzed the data using multiple machine learning (ML) approaches, including eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), random forest (RF), support vector machine (SVM), logistic regression (LR), and multilayer perceptron (MLP). Predictive models were developed using thyroid function parameters and clinical characteristics.

Results

XGBoost demonstrated the highest performance for both binary and multi-class classification tasks, while MLP performed worse compared to other models. For binary classification, the XGBoost model achieved an average area under the ROC curve (AUC) of 0.854, a recall of 0.760, a precision of 0.760, and an F1-score of 0.754 across 5-fold cross-validations (CV). Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) emerged as a top predictor in feature importance analysis, alongside age and body mass index (BMI). Similarly, for multi-classclassification, TSH ranked highly in both feature importance and SHAP value analyses. Models excluding thyroid function variables exhibited significantly inferior performance compared to those incorporating them.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that thyroid parameters, particularly TSH, might predict risk for periodontitis and serve as its biomarkers, thereby enabling early intervention and personalized patient care. Further validation through larger, prospective studies is warranted to confirm these observations.

Keywords: Thyroid dysfunction, Periodontitis, eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey (NHANES)

Introduction

Initiated by plaque biofilm buildup, periodontitis is a chronic inflammatory dental disease, characterized by destruction of periodontal support tissues.1 This condition causes alveolar bone resorption, tooth mobility, and eventual tooth loss, apart from serving as a risk factor for systemic diseases, including diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and pulmonary disorders. Thus, early prevention and management of periodontitis are clinically essential. As the body's largest endocrine gland, the thyroid secretes hormones that regulate numerous physiological processes. Thyroid dysfunction can disrupt bone metabolism, potentially leading to osteoporosis.2,3 Hypothyroidism causes low-turnover osteoporosis by reducing osteoblast and osteoclast activities, while hyperthyroidism results in high-turnover osteoporosis and reduced bone density by accelerating bone resorption over formation.

Given the possible bidirectional relationship between thyroid diseases and periodontitis,4 thyroid parameters could significantly impact periodontal health and serve as a predictive marker for periodontitis risk and severity. While observational studies have examined this association using conventional statistical methods like logistic regression (LR),5, 6, 7 more advanced analytical approaches remain unexplored.

Machine learning (ML), a subfield of artificial intelligence, has become a powerful paradigm for analyzing complex biomedical data.8,9 By combining statistical modeling with advanced computational algorithms, ML techniques can identify subtle patterns and nonlinear relationships that traditional statistical methods often overlook. ML has experienced exponential growth due to the proliferation of large-scale biomedical datasets, advancements in computational power, and development of sophisticated algorithms.8 For instance, ensemble methods like eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) and random forest (RF) have improved the prediction of diabetic complications by effectively handling heterogeneous clinical variables.10,11 Additionally, deep learning (DL) approaches have achieved a radiologist-level performance in cancer detection from medical images.12, 13, 14

In the context of dental disease prediction, recent review studies15, 16, 17 have demonstrated the superiority of ML and DL methods over conventional statistical approaches. Zhao et al.18 employed ML techniques to develop predictive models for periodontitis, multiple algorithms, including XGBoost, LR, LightGBM, RF, AdaBoost, multilayer perceptrons (MLP), support vector machine (SVM), k-nearest neighbors (KNN), and Naive Bayes. Among them, XGBoost emerged as the top-performing model, with an accuracy of 0.802 on the test set. However, these models were specifically tailored to diabetic patients rather than the general population. Additionally, Farhadian et al.19 designed an SVM-based decision-support system to diagnose various periodontal diseases using data from 300 patients. The best-performing kernel function achieved an overall cross-validation (CV) accuracy of 88.7%. Suh et al.20 revealed that DL models outperformed ML in predicting periodontitis risk, with local interpretable model-agnostic explanations (LIME) analysis identifying age, sex, education, and vitamin D as top predictors. Limitations of that study included thyroid parameter omission, area under curve (AUC)-only evaluation, and no formal statistical comparison with RF or evaluation of XGBoost (despite its strong medical application performance). Collectively, these studies suggest that applying ML to investigate thyroid-parameter and periodontal interactions could be highly efficacious.

However, the ML application in exploring endocrine-periodontal interactions remains limited. This represents a significant gap, as ML’s ability to analyze high-dimensional data could provide novel insights into the thyroid-periodontitis relationship. The current study addresses this limitation by employing a comprehensive ML framework to analyze cross-sectional data from the 2009-2010 and 2011-2012 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) cycles.

Materials and methods

Experimental data

The data for this study were obtained from the 2009-2010 and 2011-2012 cycles of NHANES. NHANES employs a rigorous protocol involving comprehensive physical examinations, laboratory testing, and standardized interviews that collect detailed information on demographics, socioeconomic status, and health indicators. The initial pooled dataset contained 20,293 participants from both survey cycles.

Thyroid function markers including free thyroxine (FT4), thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), total triiodothyronine (TT3), total thyroxine (TT4), and free T3 (FT3) were extracted from the laboratory thyroid profile data. All thyroid measurements were performed using standardized protocols at Collaborative Laboratory Services (Iowa, IA, USA) analyzed specimens for both the NHANES 2009-2010 and 2011-2012 cycles, and the University of Washington (Seattle, WA, USA) processed samples for NHANES 2009-2010.

The diagnosis of periodontitis followed the classification system developed by the American Academy of Periodontology (AAP) in collaboration with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), as adapted for NHANES data by Eke et al.21 Using the CDC-AAP case definitions for population surveillance, we further classified the periodontitis cases by severity into mild, moderate and severe categories based on clinical attachment loss (CAL) and probing pocket depth (PPD) to facilitate more detailed analysis of disease progression patterns.

Exclusion criteria

After excluding 17,437 individuals who lacked either thyroid function tests or periodontal examinations and had missing data rate >10%, we applied clinical exclusion criteria based on NHANES reference ranges. Notably, the responses coded as “refused” or “don't know” in the questionaires were treated as missing values. Participants were excluded if they exhibited primary hypothyroidism (FT4 < 0.6 ng/dL with TSH > 5.4 mIU/L), subclinical hypothyroidism (FT4 0.6-1.6 ng/dL with TSH > 5.4 mIU/L), or primary hyperthyroidism (FT4 > 1.6 ng/dL with TSH < 0.24 mIU/L). This step excluded 504 more paticipants. The final analytical sample consisted of 2352 eligible participants, including 704 without periodontitis and 1,648 with periodontitis.

Preprocessing steps

Eighteen variables were included as predictors in the ML models: sex, age, BMI, smoking status (categorized as smoker, ex-smoker, or never-smoker), hypertension status (defined clinically as systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg), education level, overweight status (defined as BMI ≥25 according to WHO standards) and vitamin D levels. Additionally, the following thryroid parameters were considered: TSH, TT3, TT4, FT3, FT4, and their respective ratios (FT4/FT3, FT4/TT4, FT3/TT3, TT4/FT3, and TT3/FT4). For missing values present in the education and hypertension status variables, we imputed them using the respective modes (most frequent categories) for each variable. For missing BMI values, we used the mean value for imputation.

The whole dataset was randomly split into training and test sets at a ratio of about 6:4. To ensure a robust model evaluation, we employed 2 complementary approaches: assessing performance on the held-out test set, and reporting average metrics across CV folds. This dual evaluation strategy provided comprehensive insights into the models’ generalizability and stability.

Machine learning methods

We employed 5 distinct ML algorithms to investigate the relationship between thyroid function and periodontitis: LR, RF, SVM, XGBoost, and MLP. LR, a generalized linear model, utilizes the sigmoid function to transform linear combinations of predictors into probability estimates (between 0 and 1). SVM identifies an optimal hyperplane in the feature space that maximizes the margin between different classes. RF operates as an ensemble method that aggregates predictions from multiple decision trees, each trained on random subsets of both samples and features, with final classifications determined by majority voting. XGBoost represents an advanced implementation of gradient boosted decision trees (GBDT), employing parallel tree boosting to enhance both computational efficiency and predictive accuracy. MLP, a class of feedforward artificial neural networks, consists of multiple interconnected layers (input, hidden, and output) capable of learning complex nonlinear relationships through hierarchical feature representation.

For most models, hyperparameter optimization was performed by a 5-fold CV and grid search. Key parameters included the number of hidden layers, nodes per layer, learning rate, and dropout rate in MLP; the number of trees and features considered at each split in RF, and the regularization parameter C and kernel type in SVM. In contrast, the hyperparameters of XGBoost, including learning rate, n_estimators, max_depth, min_child_weight, colsample_bytree, gamma, and subsample, were optimized using Bayesian optimization. Figure 1 depicts the study’s flowchart.

Fig. 1.

Study schema.

Model performance was evaluated using 4 key metrics: recall, precision, F1-score, and area under the ROC curve (AUC). Finally, both the importance scores of each method and Shapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) method were utilized to evaluate the importance/contribution of features made on each model , thus helping decode those models.

All ML modeling and statistical analyses were implemented in Python (version 3.11.4) using the following key libraries:1) Data processing: pandas (v2.2.1), NumPy (v1.26.4); 2) Machine learning: scikit-learn (v1.3.0), XGBoost (v2.0.3), PyTorch (v2.2.1); 3)Statistical analysis: SciPy (v1.12.0), statsmodels (v0.14.1); 4) Data visualization: matplotlib (v3.8.3), and 5) Class imbalance handling: imbalanced-learn (v0.12.0).

Results

Periodontitis risk

Using 18 predictor variables, we trained 5 ML models to classify periodontitis disease status. Model performance was evaluated using 5-fold CV, with average metrics and their corresponding standard error (SE) reported in Table 1. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for all models—excluding MLP due to its notably poor performance—are presented in Figure 2A. The XGBoost model achieved the highest discriminative ability, with an AUC of 0.82 (95% CI: 0.79-0.85), followed by RF (AUC = 0.77; 95% CI = 0.73-0.81). In contrast, both LR and SVM demonstrated lower performance (AUC = 0.71; 95% CI = 0.69-0.73).

Table 1.

Performance metrics of machine learning models across 5-fold cross-validation data for periodontitis risk.

| XGBoost | Random forest | Logistic regression | Support vector machine | Multilayer perceptrons | Reduced model XGBoost | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Precision | 0.7601 ± 0.0304 | 0.7492 ± 0.0273 | 0.6883 ± 0.0291 | 0.7079 ± 0.0210 | 0.5994 ± 0.0422 | 0.7032 ± 0.0297 |

| Recall | 0.7603 ± 0.0280 | 0.7310 ± 0.0311 | 0.6902 ± 0.0294 | 0.7103 ± 0.0212 | 0.5147 ± 0.0395 | 0.7244 ± 0.0318 |

| Area under curve | 0.8544 ± 0.0165 | 0.8156 ± 0.0253 | 0.743 ± 0.0219 | 0.7534 ± 0.0126 | 0.4148 ± 0.0416 | 0.7902 ± 0.0306 |

| F1 score | 0.7536 ± 0.0310 | 0.7337 ± 0.0318 | 0.6827 ± 0.0271 | 0.7025 ± 0.0196 | 0.5406 ± 0.0322 | 0.7186 ± 0.0291 |

The reduced model was defined as the model excluding thyroid function parameters as predictors.

This model incorporated only the following covariates: sex, age, BMI, smoking status, hypertension status, educational attainment, overweight status, and vitamin D levels.

Fig. 2.

The performance of machine learning methods on the test set. A. Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves for periodontitis risk assessment. B. Confusion matrics for periodontitis risk assessment.

XGBoost demonstrated superior performance among all evaluated algorithms. The full model configuration achieved robust predictive accuracy with an AUC of 0.8544 (95% CI: 0.8221-0.8864), balanced discrimination capability (recall: 0.7603; 95% CI: 0.7054-0.8152), and strong positive predictive value (precision: 0.7601; 95% CI: 0.7005-0.8197), yielding a harmonized F1-score of 0.7536 (95% CI: 0.6928-0.8144) in CV analyses. Notably, the MLP approach consistently delivered inferior results compared to other methods, particularly ensemble techniques like RF and XGBoost, despite its deep learning architecture. The corresponding confusion matrices on the test set are present in Figure 2B, showing a consistent ranking of these ML methods.

To evaluate the added predictive value of thyroid function markers, we compared these models against reduced models that excluded thyroid-related variables (in the reduced model, only clinical and demographics features, including sex, age, BMI, smoking status, hypertension status, education levels, overweight status, and vatimin D levels were considered). Performance metrics for both approaches are summarized in Table 1, allowing direct assessment of whether thyroid function enhances predictive accuracy beyond demographic and clinical factors alone. The reduced XGBoost model exhibited statistically significant degradation across all metrics: AUC decreased to 0.7902 (95% CI: 0.7302-0.8502), recall to 0.7244 (95% CI: 0.6621-0.7867), precision to 0.7032 (95% CI: 0.6450-0.7614), and F1-score to 0.7186 (95% CI: 0.6616-0.7756). The DeLong test confirmed the significant inferiority of the reduced model's discriminatory power (AUC comparison: P = .0309).

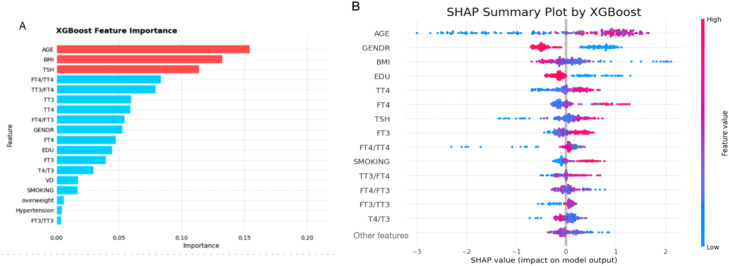

Feature importance analysis revealed interesting patterns in variable contributions. The XGBoost importance plot ranked age, BMI, and TSH as the top 3 predictors, followed by FT4/TT4 and TT3/FT4 ratios. However, SHAP value analysis showed some divergence, with TSH dropping out of the top 5 while age and BMI maintained their high rankings. This discrepancy between traditional feature importance (Figure 3A) and SHAP values (Figure 3B) underscores the nuanced nature of variable contributions in our predictive framework. Figure 3B reveals several clinically interpretable patterns: the risk of periodontitis increases with age, decreases with higher education levels, and is positively associated with elevated TT4 and TSH levels. Importantly, the consistently superior performance of models integrating thyroid function variables—especially when implemented via the XGBoost algorithm—demonstrates that thyroid parameters offer significant predictive power for periodontitis risk, augmenting conventional demographic and clinical predictors (Table 1).

Fig. 3.

Predictor importance rankings for periodontitis risk using the XGBoost model. A. Importance rankings as determined by the model. B. SHAP summary plot, showing feature importance rankings and potential impact direction.

Periodontitis severity

Subsequently, we used the same ML approaches to develop predictive models for periodontitis. For this analysis, we combined mild and moderate periodontitis cases and created 3 distinct categories: healthy controls, mild-to-moderate periodontitis, and severe periodontitis.

Following our established methodology, we compared the full model (including thyroid hormone levels) against the reduced model (excluding thyroid variables). The results showed several consistent patterns: First, XGBoost again demonstrated superior performance across all evaluation metrics, while MLP remained the weakest performer. Second, the XGBoost reduced model consistently underperformed compared to its counterpart that included thyroid parameters (the full model) across all evaluation metrics (Table 2). Third, all models showed reduced performance compared to the binary classification task. This may be due to limited sample sizes in some categories as the number of classes increased. A second possible reason is that combining mild and moderate cases into 1 group may have obscured heterogeneity, as some moderate cases resemble severe cases more than mild ones. Lastly, it also reflects the greater complexity of multiclass prediction. Given the suboptimal performance, this classification remains exploratory; we therefore chose not to present or discuss these results in detail.

Table 2.

Performance metrics of machine learning models across 5-fold cross-validation data for periodontitis severity.

| XGBoost | Random forest | Logistic regression | Support vector machine | Multilayer perceptrons | Reduced model XGBoost | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Precision | 0.6529 ± 0.0379 | 0.6319 ± 0.0306 | 0.6179 ± 0.0258 | 0.5115 ± 0.0246 | 0.5025 ± 0.0258 | 0.5928 ± 0.0232 |

| Recall | 0.6145 ± 0.0488 | 0.5778 ± 0.0351 | 0.5203 ± 0.0267 | 0.4335 ± 0.0204 | 0.3346 ± 0.0240 | 0.5757 ± 0.0247 |

| Area under curve | 0.8151 ± 0.0270 | 0.7974 ± 0.0301 | 0.7557 ± 0.0314 | 0.4241 ± 0.0238 | 0.2319 ± 0.0084 | 0.7613 ± 0.0282 |

| F1 | 0.6124 ± 0.0449 | 0.5791 ± 0.0366 | 0.5282 ± 0.0274 | 0.5707 ± 0.0471 | 0.5816 ± 0.0314 | 0.5572 ± 0.0228 |

The reduced model was defined as the model excluding thyroid function parameters as predictors.

This model incorporated only the following covariates: sex, age, BMI, smoking status, hypertension status, educational attainment, overweight status, and vitamin D levels.

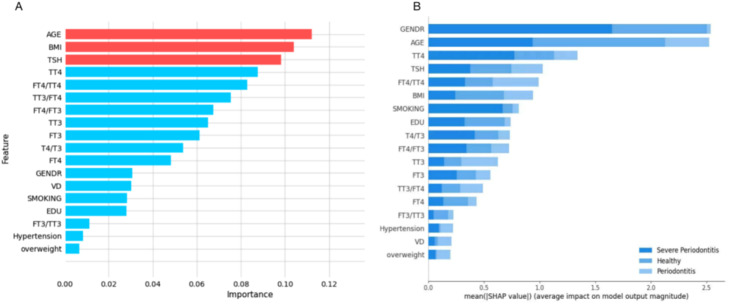

Feature importance analysis revealed that BMI, age and TSH were consistently ranked among the top predictors in the XGBoost model (Figure 4A). SHAP value analysis (Figure 4B) showed some variation, with gender, age, TT4, TSH and FT4/TT4 ratio emerging as the most influential features. This partial agreement between the 2 feature evaluation methods suggests that while certain demographic and thyroid-related variables are consistently important, their exact contributions may vary depending on the evaluation approach.

Fig. 4.

Predictor importance rankings for periodontitis severity using the XGBoost model. A. Importance rankings as determined by the model. B. Importance rankings generated using the Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP) method.

Discussion

This study sought to: 1) investigate the association between thyroid function and periodontitis, and 2) evaluate the predictive capacity of thyroid parameters for disease development and progression. Our analysis suggested that XGBoost-based models demonstrated a strong predictive performance, with TSH emerging as a significant contributor to both periodontitis risk and severity assessment.

Observational studies22,23 demonstrated that hypothyroid patients exhibit both higher prevalence and greater severity of periodontal disease compared to controls. A retrospective population study of 2,530 euthyroid Chinese participants further supports the thyroid-periodontitis association.7 The analysis revealed significant positive correlations between thyroid function indices and periodontitis risk when examined per standard deviation (SD) increase. Most notably, each standard deviation increase in TSH levels was significantly associated with higher periodontitis risk (OR = 1.36; 95% CI: 1.21-1.52). This result aligns with our SHAP-derived feature interpretation and existing observational data. Conversely, it contradicts a Mendelian randomization (MR) study24 that found no causal relationship. While that MR analysis identified hypothyroidism as significantly associated with periodontitis risk, it did not investigate potential causal links with disease severity. Therefore, further investigation is definitely needed.

Regarding the potential pathways/mechanisms underlying the thyroid-periodontitis association, the pituitary gland secretes TSH, which stimulates the thyroid gland to produce and release thyroid hormones (TH). These hormones bind to target tissues’ specific receptors and regulate various metabolic processes. Disruptions in TH secretion impair normal bone metabolism and cause pathological bone lesions. Notably, TSH also directly influences bone remodeling independent of its endocrine function.25 TSH suppresses osteoclast formation and activity of osteoclasts through its G-protein-coupled receptor (TSHR). Reduced TSHR expression might cause the development of osteoporosis,26 while an in vitro study demonstrated that TSH inhibits osteoclasts’ function via TNF-α modulation.25 Experimental studies reveal that TSH downregulates TNF-α transcription induced by IL-1 or RANKL stimulation. Yamoah et al.26 also reported elevated TNF-α expression in osteoclast progenitor cells of TSHR-deficient mice, thereby exhibiting increased susceptibility to osteoporosis. These findings suggest that excessive TNF-α production causes bone loss.27 Collectively, thyroid dysfunction disrupts bone metabolism through multiple pathways involving these cytokines and signaling molecules, potentially initiating osteoporosis and periodontitis.

Our study had several limitations. First, we did not perform any external validation using completely independent cohorts, which might have limited the generalizability and applications of our predictive models. Second, residual or unobserved confounding effects are possible, such as dietary intake and C-reactive protein levels. This may have resulted in biased effect estimation/predictive values of TH concentrations on the disease. Furthermore, urinary iodine levels were not considered in modeling processes given these details were missing in the majority of participants. Since urinary iodine levels might influence TSH levels,28,29 their exclusion in the ML models may lead to a biased estimation. Although incorporating additional relevant features could potentially enhance model performance and reduce estimation bias, this approach would unavoidably increase the prevalence of missing data. To preserve data quality and analytical rigor, we deliberately excluded variables exhibiting high rates of missing values. Future research should overcome these limitations by implementing prospective studies with more comprehensive clinical variable collection and broader population representation to reduce biases and improve generalizability. Fourth, we did not perform feature selection, which may have resulted in some redundancy among the thyroid parameters. Furthermore, as the data were derived from an American population, the generalizability of our findings to other ethnic groups requires further investigation. Lastly, the severity of periodontitis is not exclusively categorized in this study, and more research is necessary to understand how the severity of periodontitis is influenced by TH concentrations.

Conclusions

While traditional studies have shown thyroid-periodontitis correlations and ML has proven valuable for complex disease diagnosis and prognosis, ML applications specifically examining this relationship remain scarce. Our work directly address this unmet need. Our findings demonstrate that thyroid function parameters, particularly TSH levels, may serve as valuable biomarkers for assessing both the risk and progression of periodontitis. These results suggest that TH concentrations could provide clinically meaningful insights for periodontal disease evaluation. However, additional large-scale prospective studies are needed to validate these observations, while mechanistic investigations should be conducted to elucidate the underlying biological pathways connecting thyroid dysfunction and periodontal pathogenesis and progression.

Authors’ contributions

Conception and design: NL. Data acquisition and analysis: SB, CY, HW, and ZG. Drafting of the work: HW and ST. Revision for critical important content: ST and NL. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Kwon M., Jeong Y.J., Kwak J., Jung K.Y., Baek SK. Association between oral health and thyroid disorders: a population-based cross-sectional study. Oral Dis. 2022;28(8):2277–2284. doi: 10.1111/odi.13895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Apostu D., Lucaciu O., Oltean-Dan D., et al. The influence of thyroid pathology on osteoporosis and fracture risk: a review. Diagnostics (Basel) 2020;10(3):149. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics10030149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams G.R., Bassett JHD. Thyroid diseases and bone health. J Endocrinol Invest. 2018;41(1):99–109. doi: 10.1007/s40618-017-0753-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Inchingolo F., Inchingolo A.M., Inchingolo A.D., et al. Bidirectional association between periodontitis and thyroid disease: a scoping review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2024;21(7):860. doi: 10.3390/ijerph21070860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Song E., Park M.J., Kim J.A., et al. Implication of thyroid function in periodontitis: a nationwide population-based study. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1) doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-01682-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kwon M., Jeong Y.J., Kwak J., Jung K.Y., Baek SK. Association between oral health and thyroid disorders: a population-based cross-sectional study. Oral Dis. 2022;28(8):2277–2284. doi: 10.1111/odi.13895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang H., Lu Y., Zhao L., He Y., He Y., Chen D. The mediating role of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D on the association between reduced sensitivity to thyroid hormones and periodontitis in Chinese euthyroid adults. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2024;15 doi: 10.3389/fendo.2024.1456217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greener J.G., Kandathil S.M., Moffat L., Jones DT. A guide to machine learning for biologists. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2022;23(1):40–55. doi: 10.1038/s41580-021-00407-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alhumaidi N.H., Dermawan D., Kamaruzaman H.F., Alotaiq N. The use of machine learning for analyzing real-world data in disease prediction and management: systematic review. JMIR Med Inform. 2025;13 doi: 10.2196/68898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feng X., Cai Y., Xin R. Optimizing diabetes classification with a machine learning-based framework. BMC Bioinformatics. 2023;24(1):428. doi: 10.1186/s12859-023-05467-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lv K., Cui C., Fan R., et al. Detection of diabetic patients in people with normal fasting glucose using machine learning. BMC Med. 2023;21(1):342. doi: 10.1186/s12916-023-03045-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen Y., Wang B., Zhao Y., et al. Metabolomic machine learning predictor for diagnosis and prognosis of gastric cancer. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):1657. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-46043-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duan H., Zhang Y., Qiu H., et al. Machine learning-based prediction model for distant metastasis of breast cancer. Comput Biol Med. 2024;169 doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2024.107943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li B., Kugeratski F.G., Kalluri R. A novel machine learning algorithm selects proteome signature to specifically identify cancer exosomes. eLife. 2024;12 doi: 10.7554/eLife.90390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Samaranayake L., Tuygunov N., Schwendicke F., et al. The transformative role of artificial intelligence in dentistry: a comprehensive overview. part 1: fundamentals of ai, and its contemporary applications in dentistry. Int Dent J. 2025;75(2):383–396. doi: 10.1016/j.identj.2025.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tuygunov N., Samaranayake L., Khurshid Z., et al. The transformative role of artificial intelligence in dentistry: a comprehensive overview part 2: the promise and perils, and the international dental federation communique. Int Dent J. 2025;75(2):397–404. doi: 10.1016/j.identj.2025.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sitaras S., Tsolakis I.A., Gelsini M., et al. Applications of artificial intelligence in dental medicine: a critical review. Int Dent J. 2025;75(2):474–486. doi: 10.1016/j.identj.2024.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao A., Chen Y., Yang H., Chen T., Rao X., Li Z. Exploring the risk factors and clustering patterns of periodontitis in patients with different subtypes of diabetes through machine learning and cluster analysis. Acta Odontol Scand. 2024;83:653–665. doi: 10.2340/aos.v83.42435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farhadian M., Shokouhi P., Torkzaban P. A decision support system based on support vector machine for diagnosis of periodontal disease. BMC Res Notes. 2020;13(1):337. doi: 10.1186/s13104-020-05180-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suh B., Yu H., Cha J.K., Choi J., Kim JW. Explainable deep learning approaches for risk screening of periodontitis. J Dent Res. 2025;104(1):45–53. doi: 10.1177/00220345241286488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eke P.I., Dye B.A., Wei L., et al. Update on prevalence of periodontitis in adults in the United States: NHANES 2009 to 2012. J Periodontol. 2015;86(5):611–622. doi: 10.1902/jop.2015.140520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim S.M., Ryu V., Miyashita S., et al. Hyperthyroidism, and Bone Mass. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106(12):e4809–e4821. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgab548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.AlAhmari F.M., Albahouth H.S., Almalky H.A., Almutairi E.S., Alatyan M.H., Alotaibi LA. Association between periodontal diseases and hypothyroidism: a case-control study. Int J Gen Med. 2024;17:3613–3619. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S476430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gao Y., Huang D., Liu Y., Qiu Y., Lu S. Periodontitis and thyroid function: a bidirectional Mendelian randomization study. J Periodontal Res. 2024;59(3):491–499. doi: 10.1111/jre.13240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abe E., Marians R.C., Yu W., et al. TSH is a negative regulator of skeletal remodeling. Cell. 2003;115(2):151–162. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00771-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamoah K., Brebene A., Baliram R., et al. High-mobility group box proteins modulate tumor necrosis factor-alpha expression in osteoclastogenesis via a novel deoxyribonucleic acid sequence. Mol Endocrinol. 2008;22(5):1141–1153. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Monteiro Viana J.C., da Silva Gomes G.E., Duarte Oliveira F.J., et al. The role of different types of cannabinoids in periodontal disease: an integrative review. Pharmaceutics. 2024;16(7):893. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics16070893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gonzalez-Nunez A., García-Solís P., Ramirez-Garcia S.G., et al. High iodine urinary concentration is associated with high TSH levels but not with nutrition status in schoolchildren of northeastern Mexico. Nutrients. 2021;13(11):3975. doi: 10.3390/nu13113975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Henjum S., Groufh-Jacobsen S., Aakre I., et al. Thyroid function and urinary concentrations of iodine, selenium, and arsenic in vegans, lacto-ovo vegetarians and pescatarians. Eur J Nutr. 2023;62(8):3329–3338. doi: 10.1007/s00394-023-03218-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]