Abstract

Background

Sleep problems faced by college students have become an important global health issue that requires immediate attention. This study investigates the relationship between dysfunctional beliefs and attitudes about sleep (DBAS) and sleep quality among college students, with a focus on examining the mediating effects of anxiety, stress, and depression in this relationship.

Methods

A cross-sectional design was employed, with data collected through a survey conducted from January to March 2024 among Chinese university students. The survey evaluated DBAS, anxiety, depression, stress, and sleep quality. Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis were performed using SPSS 27.0, subsequently applying PROCESS models (Model 4 and Model 6) to develop parallel and chain mediation models.

Results

A total of 864 valid responses were retained, comprising 629 male participants (72.8%) and 235 female participants (27.2%), with ages ranging from 16 to 23 years (M = 18.8, SD = 1.0). The findings demonstrated that DBAS negatively predicted sleep quality (B = − 0.15, 95% CI [− 0.20, − 0.09]). Anxiety (B = − 0.03, 95% CI [− 0.06, − 0.01]) and stress (B = − 0.05, 95% CI [− 0.08, − 0.02]) performed as parallel mediators in the association between DBAS and sleep quality. Furthermore, DBAS influenced sleep quality indirectly through the chain mediation of anxiety and stress (β = −0.04, 95% CI [− 0.07, − 0.02]).

Conclusions

DBAS has a direct negative impact on sleep quality and affects it indirectly through the parallel mediation of anxiety and stress. Additionally, DBAS may indirectly influence sleep quality through the chain-mediating effects of anxiety and stress. The study highlights the significance of addressing DBAS, as it directly affects students’ emotional well-being and sleep quality. Future research should concentrate on creating targeted interventions to reduce DBAS, thus enhancing emotional health and sleep quality in university students.

Keywords: Dysfunctional beliefs and attitudes about sleep, Sleep quality, Anxiety, Stress, College student

Introduction

Sleep is a fundamental physiological process essential for human survival [1], crucial for maintaining internal balance, facilitating physical recovery, and regulating mental well-being [2] Research indicates that almost one-third of human life is dedicated to sleep [3], underscoring the significant influence of sleep on both physical and mental well-being. Sleep quality denotes a person’s subjective evaluations of sleep experiences and outcomes. Chronic poor sleep quality is associated with various adverse health outcomes, including obesity [4–6], diabetes [6, 7], cardiovascular diseases [8, 9], depression [10, 11], anxiety [11, 12], stress [4, 13], and attention deficits [14, 15]. The World Health Organization (WHO) reports that over 27% of the global population experiences sleep disorders [16]. Correspondingly, China’s 2022 Sleep White Paper documents sleep disorders in > 75% of its population, with university-aged individuals (19–25 years) averaging only 6.46 h of sleep [17], confirming disproportionately high prevalence in this demographic. Research indicates that both insufficient and excessive sleep duration are significantly associated with heightened mortality risk [18]. Consequently, poor sleep quality substantially compromises physical health and is strongly associated with mental health disorders [19]. University students face significant academic and social pressures, making them particularly vulnerable to psychological distress and sleep deficiencies [19–21]. Therefore, addressing sleep disorders in this population represents a critical global public health priority requiring urgent intervention.

Multiple studies demonstrate that cognitive processes significantly modulate sleep, particularly through dysfunctional beliefs and attitudes about sleep (DBAS) that substantially compromise sleep quality [22]. DBAS represent crucial cognitive determinants of sleep quality, encompassing dysfunctional beliefs such as erroneous evaluations, unrealistic expectations, and perceptual biases [23]. Harvey’s cognitive model posits that DBAS exacerbate sleep-related performance anxiety, inducing emotional distress and prolonged wakefulness [22]. These processes may disrupt compensatory sleep behaviors like staying in bed during daytime drowsiness or beyond scheduled wake times [24]. Empirical evidence indicates that DBAS are significantly associated with detrimental actions, implying that focused cognitive therapies may enhance sleep quality [25]. Furthermore, extensive research confirms DBAS negatively impact sleep quality, highlighting cognitive factors’ critical role in preventing and treating sleep disorders [26–29]. Prior studies demonstrate that cognitive-behavioral interventions aimed at correcting DBAS effectively improve sleep quality [30–32]. Recent evaluations indicate that altering DBAS enhances sleep quality and mitigates cognitive and behavioral dysfunctions contributing to insomnia [31, 33]. However, certain investigations have identified no substantial statistical correlation between DBAS and sleep issues [34, 35]. Contradictory findings persist despite extensive research on DBAS-sleep quality relationships. Thus, although DBAS correction improves sleep quality, the underlying mechanisms remain unclear. This study seeks to examine the influence of DBAS on sleep quality and to analyze the probable processes at play.

Negative emotions refer to a subjective sensation of distress, generally including anxiety, depression, and stress [36]. University students, as a distinct cohort transitioning from adolescents to adulthood, face numerous challenges in social adaption and psychological adjustment, rendering them at risk for negative emotions such as anxiety and stress [37, 38]. Surveys revealed that the prevalence rates of anxiety, depression, and stress among college students are 29%, 37%, and 23%, respectively [39]. Comprehensive studies indicate that depression [40], anxiety [41, 42], and stress [43] considerably impair sleep quality and intensify sleep problems. Research demonstrates a strong correlation between depression, anxiety, and insomnia [44], revealing a positive relationship between the exacerbation of negative emotions and the deterioration of sleep quality. The mechanisms that underlying anxiety and sleep disorders are analogous, primarily involving dysfunctions in neurotransmitter systems, particularly the cholinergic and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) systems. This dysfunction results in excessive cerebral excitation, which impairs emotional regulation and responsiveness, thereby aggravating sleep disorders [45]. A review indicated that sleep quality and negative emotions (including anxiety and depression) exhibit a bidirectional relationship, whereby sleep disturbances caused by anxiety or depression exacerbate negative emotional states [46]. Cortisol, a pivotal hormone, significantly influences this process. It is intricately linked to the stress response, usually peaking in the morning and progressively declining during the day, attaining its nadir at night. Nonetheless, symptoms of depression, anxiety, and sleeplessness frequently result in heightened cortisol levels during the night, exacerbating physiological arousal and intensifying both unpleasant emotions and sleep disturbances. A systematic review of sleep disturbances in anxiety and associated disorders [46]. Research reveals that anxiety and depression frequently co-occur with increased preoccupation with sleep, hence intensifying sleep disturbances [47]. A cross-sectional study by Bei [48] demonstrated that DBAS exacerbate the correlation between sleep quality and adverse emotions, particularly in individuals susceptible to negative sleep cognitions. DBAS significantly worsen symptoms of anxiety, depression, and insomnia [49–51], with anxiety moderating the relationship between sleep quality and DBAS [52, 53].

Stress is generally defined as the physiological and psychological response to external or internal stimuli [54]. The extrinsic override mechanism model posits that prolonged stress maintains the brain in a state of heightened arousal, thereby intensifying insomnia symptoms [55]. Research indicates that elevated stress levels induce both physical and psychological tension, hindering individuals’ ability to initiate sleep or attain adequate deep sleep [56]. Rachman et al. [57] proposed that insomnia may stem from insufficient emotional processing in response to stress. The emotion regulation model indicates that persons with anxiety or depression frequently have deficient emotion regulation skills, rendering them more susceptible to stress and less adept at employing suitable coping mechanisms [58]. For example, individuals with depression often exhibit social avoidance and diminish everyday activities, resulting in a decline in essential social interactions and emotional support, which then exacerbates their perception of stress and feelings of loneliness, so perpetuating a vicious cycle [59, 60]. Furthermore, the vulnerability-stress paradigm emphasizes that stress significantly contributes to the onset of psychological diseases by triggering an individual’s susceptibility, potentially resulting in genuine psychological pathology [55]. Individuals predisposed to anxiety or depression generally exhibit heightened sensitivity to stress, frequently engaging in rumination over adverse occurrences and responding to perceived dangers, thereby exacerbating their sleep disturbances [55]. Within this framework, we propose that anxiety and depression, as antecedents to stress, intensify individuals’ perceptions and responses to stress, thereby affecting their sleep quality. Lundh’s theory on sleep disorders asserts that DBAS directly impede the sleep process and additionally exacerbate sleep disturbances by activating brain neurons through stress, thereby contributing to insomnia [61]. Research has established a bidirectional connection among anxiety, depression, and sleep quality, with DBAS amplifying the association between negative emotions and sleep, therefore worsening symptoms of anxiety, sadness, and insomnia [46]. Thus, stress emerges as a key mediator in the relationship between anxiety/depression and sleep quality.

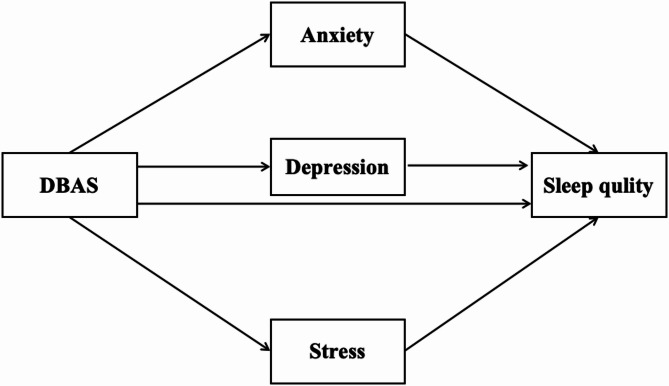

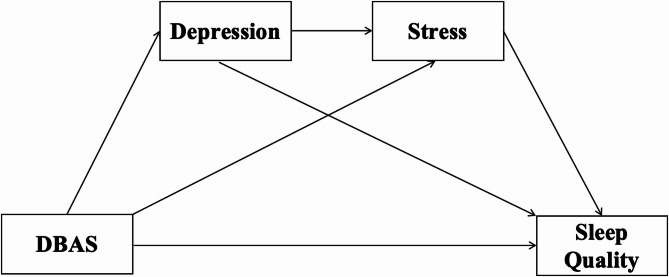

This study aims to examine the mechanisms by which DBAS influence sleep quality, while investigating the mediating roles of depression, anxiety, and stress. Building on the theoretical framework, we propose a parallel mediation model (Fig. 1; Hypothesis 2). If Hypothesis 2 is supported, we further hypothesize chain mediation effects in which depression or anxiety mediate the relationship between DBAS and stress, with stress subsequently mediating the pathway to sleep quality (Figs. 2 and 3; Hypotheses 3 and 4). Thus, we propose the following hypotheses:

Fig. 1.

Diagram of the parallel mediation hypothesis model

Fig. 2.

Diagram of the chain mediation hypothesis model of anxiety and stress

Fig. 3.

Diagram of the chain mediation hypothesis model of depression and stress

Hypothesis 1

There is a significant correlation between college students’ DBAS and sleep quality.

Hypothesis 2

Depression, anxiety, and stress play a parallel mediating role in the association between DBAS and sleep quality.

Hypothesis 3

Anxiety and stress have a chain mediation effect on the relationship between DBAS on sleep quality.

Hypothesis 4

Depression and stress have a chain mediation effect on the relationship between DBAS on sleep quality.

Methods

Participants

The study was conducted from January to March 2024, employing a random sample technique to survey undergraduate students at a university in Shanghai, China. To ensure confidentiality, all responses were anonymized. The survey’s beginning offered comprehensive information regarding the study’s aims and substance, ensuring participants comprehended the research clearly. Participation was optional, and informed consent was secured in advance. The anticipated duration to finish the questionnaire was 10 min. The institutional ethics committee approved the protocol in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Questionnaires with implausible completion times (< 3 min) or identical responses across > 80% of items were excluded. The 1,010 distributed questionnaires, 864 valid responses were retained, resulting in a response rate of 85.54%. The sample comprised 629 male participants (72.8%) and 235 female participants (27.2%), aged 16 to 23 years (M = 18.8, SD = 1).

Measures

Sleep quality

The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), which was developed by Buysse et al. [62] and translated by Zheng et al. [63], was used in this study to evaluate the quality of sleep for participants. The PSQI contains seven components: subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleeping medication, and daytime dysfunction. Items are scored 0–3, yielding a global score of 0–21, with higher scores indicating poorer sleep quality. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for this scale was 0.802 in this study.

Depression, anxiety, and stress

The Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS-21), which was developed by Lovibond et al. [64] and translated by Gong et al. [65], was employed in this study to evaluate the negative emotional states of the participants. DASS-21 comprises three dimensions: depression, anxiety, and stress. The scale comprises three 7-item subscales (depression, anxiety, stress) rated on a 4-point Likert scale. The scores for each subscale range from 7 to 28. Scores that are higher suggest that the emotional state is worse. In this study, the overall Cronbach’s alpha for the scale was 0.947 with subscale coefficients of 0.877 for depression, 0.821 for anxiety, and 0.879 for stress.

Dysfunctional beliefs and attitudes about sleep

The Dysfunctional Beliefs and Attitudes about Sleep Scale-16 (DBAS-16), which was developed by Morin et al. [23] and translated by Fu [66], was employed in this study to evaluate the beliefs and attitudes of participants about sleep. The scale comprises 16 items, with responses ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”), resulting in a total score range of 16 to 80. The scale is composed of four key components: medication-related beliefs, concerns about insomnia, expectations about sleep, and the consequences of insomnia. Per standardized DBAS-16 scoring, lower total scores indicate stronger endorsement of irrational sleep beliefs and attitudes. The Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.912 in this study.

Statistical analysis

We performed descriptive statistics, Pearson correlation analysis, and mediation analyses using SPSS 27.0. First, common method bias was assessed through Harman’s single-factor test [67] via unrotated principal component analysis of all scale items. Subsequently, descriptive statistics and Pearson correlations were computed for primary variables. Finally, mediation analyses were conducted using Hayes’ PROCESS macro (v4.0, Model 4) [68] to test parallel mediation effects of depression, anxiety, and stress on the DBAS - sleep quality relationship. Furthermore, we utilized the PROCESS (Model 6) to investigate if depression and stress, along with anxiety and stress, functioned as chain mediators in the association between DBAS and sleep quality. We conducted 5000 bootstrap iterations to evaluate model fit and generate the 95% confidence interval (95% CI), so augmenting the trustworthiness of our data analysis. The significance level was established at p <.05 for the entire study.

Results

Common method bias test

The common method bias test findings indicated that 12 factors possessed eigenvalues exceeding 1. The first factor accounted for 23.55% of the total variance, below the critical threshold of 40% [67], indicating no significant common method bias.

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis

As show in Table 1, significant negative correlations were observed between DBAS and depression (r = −.19, p <.01), anxiety (r = −.18, p < 001), stress (r = −.20, p <.01), and sleep quality (r = −.24, p <.01). Per the DBAS scoring protocol, lower total scores reflect more irrational sleep beliefs and attitudes. Positive correlations were significant among depression, anxiety (r =.81, p <.01), stress (r =.84, p <.01), and sleep quality (r =.45, p <.01). A significant positive correlation was also noted between stress and sleep quality (r =.48, p < 001).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis (N = 864)

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. DBAS | 48.78 | 11.89 | |||||

| 2. Depression | 6.62 | 7.37 | − 0.19** | ||||

| 3. Anxiety | 6.81 | 6.65 | − 0.18*** | 0.81** | |||

| 4. Stress | 8.18 | 7.89 | − 0.20** | 0.84** | 0.85** | ||

| 5. Sleep Quality | 4.95 | 2.76 | − 0.24** | 0.45** | 0.46** | 0.48*** |

Note: M = Means, SD = Standard deviations, ** p <.01, *** p <.001

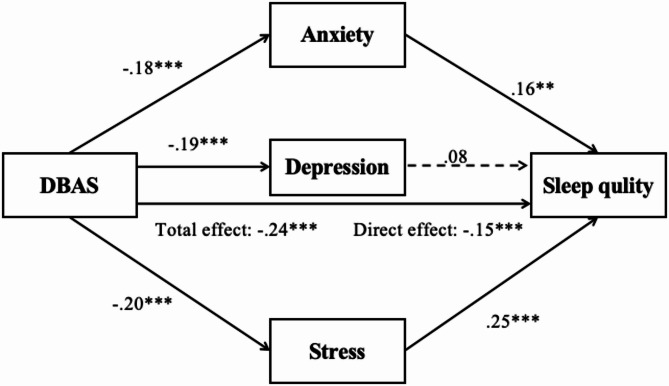

Parallel mediation model

A parallel mediation analysis, controlling for gender, age, and grade, examined whether depression, anxiety, and stress mediated the relationship between DBAS and sleep quality. As illustrated in Fig. 4, DBAS negatively predicted anxiety (β = −0.18, p <.001) and stress (β = −0.20, p <.001), both of which in turn positively predicted sleep quality (βanxiety = 0.16, p =.003; βstress = 0.25, p <.001). Although DBAS also negatively predicted depression (βdepression = − 0.19, p <.001), the path from depression to sleep quality was non-significant (βdepression = 0.08, p >.05).

Fig. 4.

The parallel multiple mediation model diagram of negative emotion in DBAS and sleep quality. Note: ** p <.01, *** p <.001

As shown in Table 2, the total effect of DBAS on sleep quality was significant (B = − 0.24, 95% Boot CI [− 0.30, − 0.17]). The direct effect remained significant (B = − 0.15, 95% Boot CI [− 0.20, − 0.09]), explaining 62.5% of the total effect. The total indirect effect through the three mediators was also significant (B = − 0.09, 95% Boot CI [− 0.13, − 0.06]), accounting for 37.5% of the total effect. Specifically, the stress pathway showed the strongest mediation (B = − 0.05, 55.5% of the total indirect effect), followed by anxiety (B = − 0.03, 33.3%), whereas depression’s indirect effect was non-significant (B = − 0.01, 95% Boot CI [− 0.04, 0.01]). These results partially support Hypothesis 2, indicating that anxiety and stress significantly mediate the DBAS - sleep quality relationship, whereas depression does not demonstrate a significant mediating effect.

Table 2.

Confidence intervals and effect sizes for the parallel mediation effect test

| Path | Effect size | Boot Standard Error | Boot CI Upper Limit |

Boot CI Lower Limit |

Relative mediation effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Effect | − 0.15 | 0.03 | − 0.20 | − 0.09 | 62.5% |

| Total Indirect Effect | − 0.09 | 0.02 | − 0.13 | − 0.06 | 37.5% |

| DBAS → Depression → Sleep Quality | − 0.01 | 0.01 | − 0.04 | 0.01 | 11.1% |

| DBAS → Anxiety → Sleep Quality | − 0.03 | 0.01 | − 0.06 | − 0.01 | 33.3% |

| DBAS → Stress → Sleep Quality | − 0.05 | 0.02 | − 0.08 | − 0.02 | 55.5% |

| Total Effect | − 0.24 | 0.03 | − 0.30 | − 0.17 | 1 |

Chain mediation model

In the preceding phase of the analysis, we confirmed that anxiety and stress served as parallel mediators in the relationship between DBAS and sleep quality. Furthermore, guided by theoretical foundations, we employed Hayes’ PROCESS macro (Model 6) to investigate the sequential mediating effect of anxiety and stress on the relationship between DBAS and sleep quality. After controlling for age, gender, and grade characteristics, the findings indicated that DBAS significantly and negatively predicted the sleep quality of college students (β = − 0.24, p <.001) (Fig. 5; Table 3). The mediation model analysis revealed that DBAS significantly negatively predicted anxiety among college students (β = − 0.18, p <.001), and anxiety significantly positively predicted sleep quality (β = 0.19, p <.001). DBAS significantly and negatively predicted stress (β = − 0.05, p <.05), while stress positively and significantly predicted the sleep quality of college students (β = 0.29, p <.001). In this pathway, anxiety significantly predicts stress (β = 0.83, p <.001), and the chain mediation of anxiety and stress accounts for the relationship between DBAS and sleep quality in college students (β = − 0.09, p <.001). Table 4 provides a comprehensive summary of the mediation pathways and their respective effect sizes.

Fig. 5.

Diagram of chain mediation. Note: * p <.05, ** p <.01, *** p <.001

Table 3.

Tests the mediation model

| Outcome variables | Predictor variables | β | SE | t | R 2 | F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep quality | DBAS | − 0.238 | 0.033 | -7.283 | 0.085 | 19.95*** |

| Gender | 0.111 | 0.033 | 3.397 | |||

| Age | 0.127 | 0.046 | 2.764 | |||

| Grade | − 0.026 | 0.046 | − 0.573 | |||

| Anxiety | DBAS | − 0.180 | 0.034 | -5.362 | 0.041 | 9.20*** |

| Gender | − 0.008 | 0.034 | − 0.228 | |||

| Age | 0.088 | 0.047 | 1.878 | |||

| Grade | 0.001 | 0.047 | 0.019 | |||

| Stress | DBAS | − 0.048 | 0.018 | -2.658 | 0.72 | 443.92*** |

| Anxiety | 0.834 | 0.018 | 45.305 | |||

| Gender | − 0.002 | 0.018 | − 0.1 | |||

| Age | 0.009 | 0.025 | 0.4 | |||

| Grade | 0.039 | 0.025 | 1.557 | |||

| Sleep quality | DBAS | − 0.148 | 0.03 | -4.98 | 0.28 | 56.32*** |

| Anxiety | 0.186 | 0.054 | 3.423 | |||

| Stress | 0.288 | 0.054 | 5.265 | |||

| Gender | 0.115 | 0.029 | 3.962 | |||

| Age | 0.086 | 0.041 | 2.127 | |||

| Grade | − 0.038 | 0.041 | − 0.934 |

Table 4.

Path analysis of mediation model

| Path | Effect size | Boot Standard Error | Boot CI Upper Limit |

Boot CI Lower Limit |

Relative mediation effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Effect | − 0.15 | 0.03 | − 0.21 | − 0.09 | 62.5% |

| Total Indirect Effect | − 0.09 | 0.02 | − 0.13 | − 0.06 | 37.5% |

| DBAS → Anxiety → Sleep Quality | − 0.03 | 0.01 | − 0.06 | − 0.01 | 33.3% |

| DBAS → Stress → Sleep Quality | − 0.01 | 0.01 | − 0.03 | − 0.01 | 11.1% |

| DBAS → Anxiety → Stress → Sleep Quality | − 0.04 | 0.01 | − 0.07 | − 0.02 | 44.4% |

| Total Effect | − 0.24 | 0.03 | − 0.30 | − 0.17 | 1 |

Discussion

Sleep is a fundamental physiological function essential for maintaining homeostasis and mental health, and is intricately associated with numerous health outcomes. University students face heightened risks of poor sleep quality and emotional distress due to academic pressures and emerging social challenges, which adversely affect learning and cognitive abilities. This study aimed to explore how DBAS affects sleep quality among university students and to examine the mediating roles of depression, anxiety, and stress in this relationship. Results indicated that anxiety and stress served as parallel mediators between DBAS and sleep quality, with stress exerting a significantly stronger influence on sleep quality. Depression did not demonstrate a significant mediating effect within this model. Students with elevated DBAS levels are more prone to experiencing anxiety and stress, which correlate with diminished sleep quality. Further analysis revealed that DBAS - related anxiety contributed to heightened stress levels, subsequently impairing sleep quality. The chain mediation effect of anxiety and stress is significant in the relationship between DBAS and sleep quality. These findings align with existing research and support the cognitive model of insomnia.

This study demonstrated a significant negative correlation between DBAS and sleep quality among university students, indicating that higher DBAS levels were associated with poorer sleep quality. This result supported our Hypothesis 1and further emphasized the central role of cognitive factors in sleep problems. As a group with relatively high cognitive awareness, university students are typically more conscious of the importance of sleep and tend to pay more attention to their sleep status. However, this heightened awareness can lead to increased anxiety, fear, and helplessness when individuals are unable to control their sleep (e.g., experiencing difficulties falling asleep, maintaining sleep, or waking too early). These emotional responses amplify negative interpretations of sleep failure, deepen insomnia-related fear, and lead individuals to form rigid beliefs (e.g., “I must sleep for 8 hours tonight to perform well tomorrow”), further exacerbating the sleep experience [69]. Empirical research has consistently shown that DBAS is one of the core predictors of sleep quality, particularly in the formation and maintenance of sleep disorders [21, 22, 26–29]. From a physiological perspective, individuals with DBAS may experience excessive activation of the sympathetic nervous system when faced with sleep failure, manifesting as increased heart rate, muscle tension, and heightened alertness. This physiological activation not only worsens difficulty falling asleep but also leads to more negative emotions, such as anxiety and irritability, thus creating a vicious cycle of “cognitive-emotional-physiological” interactions [22]. Furthermore, research indicates that DBAS may lead individuals to adopt irrational compensatory behaviors, including going to bed early, postponing wake-up times, or taking daytime naps [24]. These behaviors, while aimed at compensating for sleep loss, frequently disrupt biological rhythms, exacerbate circadian rhythm disturbances, and further diminish sleep quality [33]. Our findings indicate that DBAS may paradoxically function as a cognitive risk factor for both sleep quality impairment and mental health issues [70]. DBAS are associated with reduced sleep quality, indicating that DBAS serves as a significant predictor of sleep quality in university students and a crucial target for clinical interventions aimed at treating sleep disorders.

This study identified a significant negative correlation among anxiety, DBAS, and sleep quality, with anxiety acting as a mediator in the relationship between DBAS and sleep quality, thereby partially validating Hypothesis 2. However, depression did not exhibit a significant mediating effect within this model. This finding warrants further consideration. One possible explanation is the high correlation between depression and anxiety (r =.81), which may have resulted in substantial overlap in their explanatory power. This multicollinearity could have led to depression’s unique variance being absorbed by the anxiety and stress pathways, thereby attenuating its independent mediating effect. Furthermore, since anxiety and stress are more immediate, situational emotional responses, they may exert a more direct impact on sleep quality among university students compared to depression, which often represents a more chronic emotional state. Future research could explore these differential emotional pathways in greater depth, possibly employing longitudinal or experimental designs, to better understand their specific mechanisms underlying sleep disturbances. The results of this study indicated that DBAS significantly negatively affected sleep quality and may exacerbate emotional distress by increasing sleep-related anxiety, thereby reinforcing wakefulness [20]. This relationship indicates that individuals with dysfunctional sleep beliefs are more likely to experience anxiety when facing sleep difficulties, potentially trapping them in a vicious cycle that exacerbates exacerbate sleep problems. Prior studies have shown that DBAS elevates the risk of anxiety among university students, including anxiety related to academic pressure, social stress, and emotional challenges stemming from relationships with educators, peers, and family [70]. The complex interaction between these stressors and mental health further intensifies the effect of DBAS on anxiety, potentially creating a fertile ground for the development of sleep disorders. Moreover, studies have shown that anxiety significantly impairs sleep quality through various physiological mechanisms [71]. Anxiety frequently correlates with muscle tension and increased autonomic nervous system activity [72]. This physiological response not only hinders individuals from entering deep sleep but also exacerbates difficulties in falling asleep and maintaining sleep, leading to a deterioration in sleep quality [22]. Furthermore, our research revealed that individuals with higher levels of anxiety are more prone to sleep problems, possibly because anxiety disrupts the balance of neurotransmitters in the brain, particularly the cholinergic system, GABA system, and the functioning of serotonin and melatonin—key substances for the stability of the sleep cycle [73]. This neurotransmitter imbalance can trigger irregular sleep patterns and excessive brain excitation, which impairs emotional regulation and responsiveness, thereby further worsening sleep disorders [45]. Anxiety thus serves as a crucial mediator in the relationship between DBAS and sleep quality, significantly influencing sleep via multiple physiological and cognitive mechanisms. Consequently, adjusting DBAS and managing anxiety represent promising strategies for improving sleep quality.

Our findings indicated a significant negative correlation between stress and DBAS, with stress showing the strongest standardized regression coefficient in predicting sleep quality. Mediation analysis revealed that stress significantly mediates the relationship between DBAS and sleep quality in college students, partially supporting Hypothesis 2. This result aligns with previous research, suggesting that stress often increases individuals’ worries about falling asleep, thus perpetuating the vicious cycle of insomnia [28, 43]. Lundh’s sleep disorder theory posits that DBAS not only directly interferes with sleep processes but may also disrupt sleep through stress-induced neural activation, leading to insomnia [61]. Specifically, DBAS may exacerbate stress from academic and social pressures, further impacting sleep quality in college students [74]. The intensity of this effect depends on the individual’s stress levels [28]. According to the Extrinsic Over-ride Mechanism model, prolonged stress may keep the brain in a heightened state of arousal, triggering both physical and psychological tension responses, which in turn worsen insomnia symptoms [55]. This physiological response makes it difficult for individuals to fall asleep or achieve deep sleep, further deteriorating sleep quality [56]. Rachman et al. [57] also highlighted that insomnia may be closely linked to inadequate emotional processing in response to stress. In summary, the results indicate that anxiety and stress serve as parallel mediators between DBAS and sleep quality, with stress having a more significant impact on sleep quality.

This research emphasizes the critical influence of DBAS in directly forecasting sleep quality in college students. The impact is primarily mediated by the regulation of negative emotions, which indirectly affects sleep quality deterioration. Prior studies indicate that DBAS directly negatively impacts sleep and may also elevate anxiety levels, exacerbating emotional distress and reinforcing hyperarousal [70]. College students, as a unique population, frequently encounter academic and social pressures. The complex interaction between these stressors and mental health further amplifies the influence of DBAS on anxiety, creating a potential breeding ground for sleep disturbances. These findings suggest that the emergence of stress-related emotional responses is closely linked to anxiety states. According to emotion regulation models, individuals with anxiety often lack effective strategies for managing emotions, making them more sensitive to perceived stress [58] and less capable of processing emotional experiences constructively [57]. Additionally, the vulnerability-stress model posits that stress plays a pivotal role in triggering mental health issues by activating individual vulnerabilities and converting latent predispositions into actual psychopathological symptoms [55]. Prior studies have also indicated that both anxiety and stress are associated with poorer sleep outcomes, including prolonged wakefulness, reduced total sleep time, lower sleep efficiency, and shortened REM sleep duration [75]. Thus, when individuals hold DBAS—for example, overestimating the consequences of poor sleep despite no actual sleep disorder—they may develop heightened anxiety. This, in turn, exacerbates stress and leads to further deterioration of sleep quality. Such psychological responses can activate physiological systems, disrupt sleep processes, and result in cognitive and emotional impairments such as rumination and excessive worry [22, 76]. Over time, this cycle may escalate into a chronic condition, ultimately disturbing circadian rhythms and reinforcing insomnia [77, 78]. Our findings suggest that individuals with a predisposition toward anxiety are more reactive to stress, more likely to fixate on negative events, and prone to overrespond to perceived threats—factors that collectively worsen their sleep problems. DBAS appears to elevate anxiety, activating individual vulnerabilities and amplifying stress perception and reactivity, thereby impairing sleep quality. These results shed light on the cognitive mechanisms through which DBAS influences sleep. Specifically, dysfunctional beliefs about sleep lead individuals to excessively monitor and worry about their sleep, triggering autonomic arousal and emotional distress. This heightened anxiety and stress sensitivity perpetuate a self-reinforcing cycle that ultimately results in persistent sleep disturbances.

Strengths and limitations

This research further investigates the psychological mechanisms that connect DBAS to sleep quality among college students. The findings indicate that DBAS may deteriorate sleep quality by elevating anxiety levels, activating personal vulnerabilities, and amplifying stress perception and reactivity. This study not only examines the direct impact of DBAS on sleep quality but also provides a deeper analysis of the mediating role of emotional factors, such as anxiety and stress. It offers a novel cognitive framework for understanding the factors influencing sleep quality, particularly the role of anxiety, and suggests practical psychological intervention strategies to improve sleep quality among college students. Specifically, the results imply that university mental health interventions could adopt a dual-pronged approach: using cognitive therapies to directly address dysfunctional sleep beliefs and incorporating complementary skills training for anxiety and stress management. This integrated approach could help students manage emotional responses and reduce their impact on sleep quality, leading to more effective interventions. However, the study has several limitations. The sample is derived from a distinct cultural context involving college students. While the prevalence of stress and anxiety in this population is notable, the generalizability of the findings may be limited by the characteristics of the sample. Future research should expand the sample to encompass individuals of varying ages, genders, and cultural backgrounds to improve the generalizability of the findings. This study predominantly utilized classical self-report questionnaires. Although these tools demonstrate a strong foundation of reliability and validity and were administered under instructor supervision, the inherent limitations of self-report data, including recall bias, may influence the findings. Moreover, self-reports may inadequately reflect the intricacies of sleep problems in real-time situations. Future research should utilize objective instruments, such as actigraphy, to assess sleep parameters, thereby improving the reliability and validity of the findings.

Conclusions

This study clarifies the mechanisms connecting DBAS to sleep quality among college students. DBAS was identified as a direct negative predictor of sleep quality. Anxiety and stress function as concurrent mediators in the association between DBAS and sleep quality. Additionally, DBAS may indirectly influence sleep quality through the chain-mediating effects of anxiety and stress. This study underscores the significance of monitoring and intervening in DBAS, given its direct effects on emotional well-being and sleep quality. Future interventions designed to address DBAS may provide effective strategies for enhancing sleep quality in college students.

Acknowledgements

I’m grateful to all the participants for giving their time and participating willing.

Abbreviations

- DBAS

Dysfunctional beliefs and attitudes about sleep

Author contributions

W.P.S., W.K.and X.C.: Conceptualization, data collection, data analysis, and writing themain manuscript. Q.J.L., X.L., J.X.Y., C.G.Z.and C.S.B.: Supervise and review methodology, data analysis, and manuscript writing.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

The dataset from this study is not available in public repositories. However, it can be obtained from the corresponding author W.K. upon reasonable request for reuse.

Declarations

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The authors confirm that all the methods comply with current guidelines and regulations that follow the Declaration of Helsinki. The ethics committee of Shanghai Jiao Tong University reviewed and approved the study protocol and consent forms.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

During the preparation of this work, the authors used ChatGPT 4.0 to improve language and readability. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and took full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Kohyama J. Which is more important for health: sleep quantity or sleep quality? Children. 2021;8:542. 10.3390/children8070542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spiegal K, Tasali E, Penev P, Van Cauter E. Brief communication: sleep curtailment in healthy young men is associated with decreased leptin levels, elevated Ghrelin levels and increased hunger and appetite. Ann Int Med. 2004;141(11):846–50. 10.7326/0003-4819-141-11-200412070-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pavlova MK, Latreille V. Sleep disorders. Am J Med. 2019;132(3):292–9. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2018.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hur S, Oh B, Kim H, Kwon O. Associations of diet quality and sleep quality with obesity. Nutrients. 2021;13:3181. 10.3390/nu13093181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fatima Y, Doi SAR, Mamun AA. Longitudinal impact of sleep on overweight and obesity in children and adolescents: a systematic review and bias-adjusted meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2015;16(2):137–49. 10.1111/obr.12245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Antza C, Kostopoulos G, Mostafa S, Nirantharakumar K, Tahrani A. The links between sleep duration, obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Endocrinol. 2022;252(2):125–41. 10.1530/JOE-21-0155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shan ZL, Ma HF, Xie ML, Yan PP, Guo YJ, Bao W, Rong Y, Jackson CL, Hu FB, Liu LG. Sleep duration and risk of type 2 diabetes: A Meta-analysis of prospective studies. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(3):529–37. 10.2337/dc14-2073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Çakır H, Güneş A, Er F, Çakır H, Karagöz A, Yılmaz F, Öcal L, Zehir R, Emiroğlu MY, Demir M, et al. Evaluating the relationship of sleep quality and sleep duration with Framingham coronary heart disease risk score. Chronobiol Int. 2022;39(5):636–43. 10.1080/07420528.2021.2018453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kwok CS, Kontopantelis E, Kuligowski G, Gray M, Muhyaldeen A, Gale CP, Peat GM, Cleator J, Chew-Graham C, Loke YK, et al. Self‐reported sleep duration and quality and cardiovascular disease and mortality: A dose‐response meta‐analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7(15):e008552. 10.1161/JAHA.118.008552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsuno N, Besset A, Ritchie K. Sleep and depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(10):1254–69. 10.5665/sleep.2810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alvaro PK, Roberts RM, Harris JK. A systematic review assessing bidirectionality between sleep disturbances, anxiety, and depression. Sleep. 2013;36:1059–68. 10.5665/sleep.2810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alqahtani JS, AlRabeeah SM, Aldhahir AM, Siraj R, Aldabayan YS, Alghamdi SM, Alqahtani AS, Alsaif SS, Naser AY, Alwafi H. Sleep quality, insomnia, anxiety, fatigue, stress, memory and active coping during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(4940). 10.3390/ijerph19094940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Almojali AI, Almalki SA, Alothman AS, Masuadi EM, Alaqeel MK. The prevalence and association of stress with sleep quality among medical students. J Epidemiol Glob Health. 2017;7(3):169–74. 10.1016/j.jegh.2017.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gregory AM, Agnew-Blais JC, Matthews T, Moffitt TE, Arseneault L. ADHD and sleep quality: longitudinal analyses from childhood to early adulthood in a twin cohort. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2017;46(2):284–94. 10.1080/15374416.2016.1183499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baron KG, Reid KJ. Circadian misalignment and health. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2014;26(2):139–54. 10.3109/09540261.2014.911149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Organization WH. World health statistics 2024: monitoring health for the SDGs. sustainable development goals: World Health Organization; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu X, Lang L, Wang R, Chen W, Ren X, Lin Y, Chen G, Pan C, Zhao W, Li T, et al. Poor sleep quality and its related risk factors among university students. Ann Palliat Med. 2021;10(4):4479–85. 10.21037/apm-21-472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Svensson T, Saito E, Svensson AK, Melander O, Orho-Melander M, Mimura M, Rahman S, Sawada N, Koh W-P, Shu X-O, et al. Association of sleep duration with all- and major-cause mortality among adults in japan, china, singapore, and Korea. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(9):e2122837. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.22837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mairs L, Mullan B. Self-monitoring vs. implementation intentions: a comparison of behaviour change techniques to improve sleep hygiene and sleep outcomes in students. Int J Behav Med. 2015;22(5):635–44. 10.1007/s12529-015-9467-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beiter R, Nash R, McCrady M, Rhoades D, Linscomb M, Clarahan M, Sammut S. The prevalence and correlates of depression, anxiety, and stress in a sample of college students. J Affect Disord. 2015;173:90–6. 10.1016/j.jad.2014.10.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Norbury R, Evans S. Time to think: subjective sleep quality, trait anxiety and university start time. Psychiatry Res. 2019;271:214–9. 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.11.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harvey AG. A cognitive theory and therapy for chronic insomnia. J Cogn Psychother. 2005;19(1):41–59. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morin CM, Vallières A, Ivers H. Dysfunctional beliefs and attitudes about sleep (DBAS): validation of a brief version (DBAS-16). Sleep. 2007;30(11):1547–54. 10.1093/sleep/30.11.1547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carney CE, Harris AL, Friedman J, Segal ZV. Residual sleep beliefs and sleep disturbance following cognitive behavioral therapy for major depression. Depress Anxiety. 2011;28(6):464–70. 10.1002/da.20811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pantesco EJ, Kan IP. False beliefs about sleep and their associations with sleep-related behavior. Sleep Health. 2022;8(2):216–24. 10.1016/j.sleh.2021.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jin L, Zhou J, Peng H, Ding S, Yuan H. Investigation on dysfunctional beliefs and attitudes about sleep in Chinese college students. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2018;14(null):1425–32. 10.2147/NDT.S155722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou J, Jin L-R, Tao M-J, Peng H, Ding S-S, Yuan H. The underlying characteristics of sleep behavior and its relationship to sleep-related cognitions: a latent class analysis of college students in Wuhu city, China. Health Psychol. 2020;25(7):887–97. 10.1080/13548506.2019.1687915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang C-M, Chou CP-W, Hsiao F-C. The association of dysfunctional beliefs about sleep with vulnerability to stress-related sleep disturbance in young adults. Behav Sleep Med. 2011;9(2):86–91. 10.1080/15402002.2011.557990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muthuraman K, Sankaran A, Subramanian K. Association between sleep-related cognitions, sleep-related behaviors, and insomnia in patients with anxiety and depression: A Cross-sectional study. Indian J Psychol Med. 2024;46(3):228–37. 10.1177/02537176231223304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eidelman P, Talbot L, Ivers H, Bélanger L, Morin CM, Harvey AG. Change in dysfunctional beliefs about sleep in behavior therapy, cognitive therapy, and cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia. Behav Ther. 2016;47(1):102–15. 10.1016/j.beth.2015.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Song Y, Kelly MR, Fung CH, Dzierzewski JM, Grinberg AM, Mitchell MN, Josephson K, Martin JL, Alessi CA. Change in dysfunctional sleep-Related beliefs is associated with changes in sleep and other health outcomes among older veterans with insomnia: findings from a randomized controlled trial. Ann Behav Med. 2022;56(1):35–49. 10.1093/abm/kaab030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thakral M, Von Korff M, McCurry SM, Morin CM, Vitiello MV. Changes in dysfunctional beliefs about sleep after cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2020;49:101230. 10.1016/j.smrv.2019.101230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nielson SA, Perez E, Soto P, Boyle JT, Dzierzewski JM. Challenging beliefs for quality sleep: A systematic review of maladaptive sleep beliefs and treatment outcomes following cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia. Sleep Med Rev. 2023;72:101856. 10.1016/j.smrv.2023.101856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Okajima I, Nakajima S, Ochi M, Inoue Y. Reducing dysfunctional beliefs about sleep does not significantly improve insomnia in cognitive behavioral therapy. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(7):e102565. 10.1371/journal.pone.0102565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tremblay V, Savard J, Ivers H. Predictors of the effect of cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic insomnia comorbid with breast cancer. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77(4):742–50. 10.1037/a0015492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect—The PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54(6):1063–70. 10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li Y, Wang A, Wu Y, Han N, Huang H. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of college students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychol. 2021;12. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.669119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Ye W, Ye X, Liu Y, Liu Q, Vafaei S, Gao Y, Yu H, Zhong Y, Zhan C. Effect of the novel coronavirus pneumonia pandemic on medical students’ psychological stress and its influencing factors. Front Psychol. 2020;11. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.548506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Wang C, Wen W, Zhang H, Ni J, Jiang J, Cheng Y, Zhou M, Ye L, Feng Z, Ge Z. Anxiety, depression, and stress prevalence among college students during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Health. 2021;71(7):2123–30. 10.1080/07448481.2021.1960849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Steiger A, Pawlowski M. Depression and sleep. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(3):1422–0067. 10.3390/ijms20030607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oh C-M, Kim HY, Na HK, Cho KH, Chu MK. The effect of anxiety and depression on sleep quality of individuals with high risk for insomnia: A population-based study. Front Neurol. 2019;10. 10.3389/fneur.2019.00849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Xiao T, Pan M, Xiao X, Liu Y. The relationship between physical activity and sleep disorders in adolescents: a chain-mediated model of anxiety and mobile phone dependence. BMC Psychol. 2024;12(1):751. 10.1186/s40359-024-02237-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roberts RE, Roberts CR, Xing Y. Restricted sleep among adolescents: prevalence, incidence, persistence, and associated factors. Behav Sleep Med. 2011;9(1):18–30. 10.1080/15402002.2011.533991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Taylor DJ, Lichstein KL, Durrence HH, Reidel BW, Bush AJ. Epidemiology of insomnia, depression, and anxiety. Sleep. 2005;28(11):1457–64. 10.1093/sleep/28.11.1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Clark LA, Watson D. Tripartite model of anxiety and depression: psychometric evidence and taxonomic implications. J Abnorm Psychol. 1991;100(3):316–36. 10.1037/0021-843x.100.3.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cox RC, Olatunji BO. A systematic review of sleep disturbance in anxiety and related disorders. J Anxiety Disord. 2016;37:104–29. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2015.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fang H, Tu S, Sheng J, Shao A. Depression in sleep disturbance: A review on a bidirectional relationship, mechanisms and treatment. J Cell Mol Med. 2019;23(4):2324–32. 10.1111/jcmm.14170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bei B, Wiley JF, Allen NB, Trinder J. A cognitive vulnerability model on sleep and mood in adolescents under naturalistically restricted and extended sleep opportunities. Sleep. 2015;38(3):453–61. 10.5665/sleep.4508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Peng J, Zhang T, Li Y, Wu L, Peng X, Li C, Lin X, Yu J, Mao L, Sun J, et al. Effects of dysfunctional beliefs about sleep on sleep quality and mental health among patients with COVID-19 treated in Fangcang shelter hospitals. Front Public Health. 2023;11. 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1129322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Janati Idrissi A, Lamkaddem A, Benouajjit A, Ben El Bouaazzaoui M, El Houari F, Alami M, Labyad S, Chahidi A, Benjelloun M, Rabhi S, et al. Sleep quality and mental health in the context of COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown in Morocco. Sleep Med. 2020;74:248–53. 10.1016/j.sleep.2020.07.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Blake MJ, Trinder JA, Allen NB. Mechanisms underlying the association between insomnia, anxiety, and depression in adolescence: implications for behavioral sleep interventions. Clin Psychol Rev. 2018;63:25–40. 10.1016/j.cpr.2018.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Faccini J, Joshi V, Graziani P, Del-Monte J. Beliefs about sleep: links with ruminations, nightmare, and anxiety. BMC Psychiatry. 2023;23(1):198. 10.1186/s12888-023-04672-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li HY, Guo Q, Tang QQ, Yang J, Gu YF, Shen TS. Study on the status and influencing factors of sleep beliefs and attitudes of the elderly in elderly care institutions. Modern Prev Med. 2023.

- 54.Agorastos A, Chrousos GP. The neuroendocrinology of stress: the stress-related continuum of chronic disease development. Mol Psychiatry. 2022;27(1):502–13. 10.1038/s41380-021-01224-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Richardson GS. Human physiological models of insomnia. Sleep Med. 2007;8:S9–14. 10.1016/S1389-9457(08)70003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shen Q, Wang S, Liu Y, Wang Z, Bai C, Zhang T. The chain mediating effect of psychological inflexibility and stress between physical exercise and adolescent insomnia. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):24348. 10.1038/s41598-024-75919-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rachman S. Emotional processing. Behav Res Ther. 1980;18(1):51–60. 10.1016/0005-7967(80)90069-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Amstadter A. Emotion regulation and anxiety disorders. J Anxiety Disord. 2008;22(2):211–21. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Moitra E, Herbert JD, Forman EM. Behavioral avoidance mediates the relationship between anxiety and depressive symptoms among social anxiety disorder patients. J Anxiety Disord. 2008;22(7):1205–13. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yuan Y, Jiang S, Yan S, Chen L, Zhang M, Zhang J, Luo L, Jeong J, Lv Y, Jiang K. The relationship between depression and social avoidance of college students: a moderated mediation model. J Affect Disord. 2022;300:249–54. 10.1016/j.jad.2021.12.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lundh LG, Broman JE. Insomnia as an interaction between sleep-interfering and sleep-interpreting processes. J Psychosom Res. 2000;49(5):299–310. 10.1016/s0022-3999(00)00150-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28(2):193–213. 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zheng BLM, Wang KL, Lu J. Analysis of the reliability and validity of the Chinese version of Pittsburgh sleep quality index among medical college students. J Peking Univ. 2016;48(03):5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lovibond S. Manual for the depression anxiety stress scales. Sydney Psychol Foundation. 1995.

- 65.Gong X, Xie XY, Xu R, Luo YJ. Psychometric properties of the Chinese versions of DASS-21 in Chinese college students. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2010;18(4):443-446. 10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2010.04.020

- 66.Fu S. Reliability and validity of simple sleep belief and attitude scale and its preliminary application. Nanjing Medical University; 2014.

- 67.Zhou H, Long L. Statistical remedies for common method biases. Adv Psychol Sci. 2004;12(06):942. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hayes AF. Partial, conditional, and moderated moderated mediation. Quantification, inference, and interpretation. Communication Monogr. 2018;85(1):4–40. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Edinger JD, Wohlgemuth WK, Radtke RA, Marsh GR, Quillian RE. Does cognitive-behavioral insomnia therapy alter dysfunctional beliefs about sleep? Sleep. 2001;24(5):591–9. 10.1093/sleep/24.5.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wang B, Wang Z, Zhang X, Ji Y, Shuai Y, Shen Y, Shen Z, Chen W. Relationship between dysfunctional beliefs and attitudes about sleep and mental health in medical staff: the mediating role of sleep quality. Sleep Breath. 2025;29(2):141. 10.1007/s11325-025-03283-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Akram U, Gardani M, Riemann D, Akram A, Allen SF, Lazuras L, Johann AF. Dysfunctional sleep-related cognition and anxiety mediate the relationship between multidimensional perfectionism and insomnia symptoms. Cogn Process. 2020;21:141–8. 10.1007/s10339-019-00937-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kim H, Kim SH, Jang S-I, Park E-C. Association between sleep quality and anxiety in Korean adolescents. J Prev Med Public Health. 2022;55(2):173. 10.3961/jpmph.21.498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chellappa SL, Aeschbach D. Sleep and anxiety: from mechanisms to interventions. Sleep Med Rev. 2022;61:101583. 10.1016/j.smrv.2021.101583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Schmidt RE, Courvoisier DS, Cullati S, Kraehenmann R, Linden, MVd. Too imperfect to fall asleep: perfectionism, pre-sleep counterfactual processing, and insomnia. Front Psychol. 2018;9:1288. 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Daviu N, Bruchas MR, Moghaddam B, Sandi C, Beyeler A. Neurobiological links between stress and anxiety. Neurobiol Stress. 2019;11:100191. 10.1016/j.ynstr.2019.100191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Carney CE, Edinger JD, Meyer B, Lindman L, Istre T. Symptom-focused rumination and sleep disturbance. Behav Sleep Med. 2006;4(4):228–41. 10.1207/s15402010bsm0404_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Harvey AG. Pre-sleep cognitive activity: a comparison of sleep-onset insomniacs and good sleepers. Br J Clin Psychol. 2000;39(3):275–86. 10.1348/014466500163284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sella E, Cellini N, Miola L, Sarlo M, Borella E. The influence of metacognitive beliefs on sleeping difficulties in older adults. Appl Psychol Health Well Being. 2019;11(1):20–41. 10.1111/aphw.12140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset from this study is not available in public repositories. However, it can be obtained from the corresponding author W.K. upon reasonable request for reuse.