Abstract

Background

While neutral mechanical alignment has been the gold standard for total knee arthroplasty (TKA), constitutional knee alignment is commonly nonneutral and varies widely among individuals. We aimed to determine if a bounded functional alignment strategy in robotic assisted TKA restored constitutional alignment and if this restoration resulted in superior patient-reported outcomes (PROs).

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed patients who underwent robotic TKA with a bounded functional alignment strategy at a single institution. Final intraoperative knee alignment was compared to calculated constitutional alignment, which was unknown to the surgeons during the procedure. PROs (Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score for Joint Replacement and Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System) with a 1-year follow-up were compared between patients with a final knee alignment within 2° of constitutional alignment compared with those >2° from calculated constitutional alignment. Mean changes in PROs were analyzed, and proportions achieving minimally clinical important difference between groups was determined.

Results

Of the 188 knees included, 52% (n = 98) were balanced within 2° of constitutional alignment. Despite significant differences in alignment changes between groups (2.0° vs 4.5°), no significant differences were observed in PRO measures. Mean Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score for Joint Replacement improvement (25.0 vs 29.5), Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Physical Health (8.0 vs 7.7), and Mental Health (2.7 vs 1.2) scores were comparable. Similar proportions in both groups achieved minimally clinical important difference across all measures.

Conclusions

While robotic bounded functional strategy restored constitutional alignment in half of cases, this did not result in superior PROs at 1 year. Achieving soft tissue balance within acceptable parameters of alignment and bony excision may be more important than precise restoration of prearthritic alignment.

Keywords: Total knee arthroplasty, Constitutional alignment, Patient-reported outcomes

Introduction

Although total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is an extremely successful surgical intervention from a functionality standpoint, it has been reported that up to 20% of patients report dissatisfaction postoperatively [1]. Patient dissatisfaction has been attributed to a multitude of factors including patient expectations, amount of pain relief, degree of knee function improvement, and implant type [1,2]. More recently, surgeons have become interested in alignment of the knee as a potential dissatisfier postoperatively.

Traditionally, neutral mechanical alignment has been the goal for surgeons in primary TKA [[3], [4], [5]]. Such alignment has been associated with decreased implant wear and loosening, thereby enhancing the implant longevity [4,[6], [7], [8]]. In recent years, alternative alignment methods have gained interest due to the increasing recognition that a large percentage of the nonarthritic population has a nonneutral native knee alignment [9,10]. A variety of nonmechanical alignment techniques exist, most of which aim to reconstruct the patient’s knee closer to their native prearthritic anatomy.

Proposed benefits to these strategies include minimizing soft tissue releases, improved knee kinematics and potentially enhanced functional outcomes [[11], [12], [13], [14]]. However, few studies have investigated the role of TKA alignment method and its impact on patient-reported outcomes (PROs). It remains of interest to understand how reestablishment of constitutional alignment influences PROs following TKA.

In this study, we sought to determine whether a bounded functional alignment (FA) strategy performed with robotic assistance restores constitutional alignment in primary TKA. Further, we sought to answer the question of whether restoration of constitutional alignment resulted in superior PROs at 1 year.

Material and methods

Patient sample

This study was a single institution retrospective review of consecutive patients who underwent elective TKA between September 1, 2021, and August 31, 2022. Patients were included in the study if they were aged 18 or older, had robotic-assisted (MAKOplasty) TKA, and had completed a PRO questionnaire prior to surgery and at 1 year after surgery. We excluded patients who had prior unilateral knee arthroplasty, those who had a revision TKA and patients who had a TKA without robotic assistance. We identified 241 consecutive MAKOplasty procedures performed during the period under study; of which 188 knees were included in the final analysis.

Surgical technique

Three fellowship-trained arthroplasty surgeons performed all procedures using the MAKO robotic arm assisted surgery system (Stryker Corp, Kalamazoo, MI). A standard medial parapatellar approach was performed in all cases. Two surgeons (J.C.S., C.M.L.) excised the posterior cruciate ligament while one surgeon (G.P.) retained it. The surgical strategy was a FA (bounded or restricted kinematic alignment) approach. This approach focuses on maintaining alignment within a certain range of varus and valgus relying primarily on bone cuts to achieve adequate balance based on computer-assisted intraoperative information. Very limited releases of the collateral ligaments are only considered if adequate balance cannot be achieved alone by bone resection. Soft tissue laxity is the primary driver for appropriate balancing of the knee in all cases.

Femoral array pins were placed intraincisional in the femoral metaphysis, with tibial array pins placed either extra-incisional approximately 10 cm distal to the tibial tubercle or intraincisional at least 3 cm distal to the tibial joint line. Following registration and bony mapping verification using the preoperative computed tomography (CT) model, osteophytes were removed, and the tibia was subluxed anteriorly to account for soft tissue tension changes upon component implantation. Mako TKA 1.0 software (Stryker Corp., Kalamazoo, MI) was used to assess virtual joint line gaps, with femoral rotation aligned to the trans-epicondylar axis. Gap measurements were taken at 90° flexion (medial and lateral flexion gaps) and 10° flexion (medial and lateral extension gaps) to detension the posterior capsule.

Initial implant positioning started with mechanical alignment (0° coronal angulation of femur and tibia, 3° posterior tibial slope). Based on the obtained gaps during intraoperative manipulation in conjunction with robotic CT-based spatial modeling, implant positioning was adjusted to achieve medial-lateral balance while minimizing soft tissue releases. For varus knees, a 1 mm smaller medial extension gap and 2 mm smaller medial flexion gap was targeted relative to lateral gaps, with bone resections limited to 4° of tibial varus and 6° of overall varus. For valgus knees, equal medial-lateral laxity was targeted in both extension and flexion, with resections not exceeding 3° of tibial or overall valgus. Additional soft tissue releases were performed only when necessary to accomplish balance outside these parameters. In all cases, the knee implant used was the Stryker Triathlon (Stryker Corp., Kalamazoo, MI).

Constitutional alignment, which is predicted by the arithmetic hip-knee angle (aHKA), is calculated by the robot software with CT imaging as important data points recorded during the procedure, but this information is never taken into account at any point during the procedure. For this reason, surgeons were blinded to each knee's constitutional alignment during the procedure. This blinding to prearthritic alignment allowed us to determine if our soft tissue-guided FA strategy would incidentally recreate the patient's native, or constitutional, alignment without deliberately targeting it.

PROs and measures

Patients were administered a questionnaire on PROs via a web-based platform (OBERD, Universal Research Solutions LLC, Columbia, MO). Every patient was invited to complete this survey up to 1 month before surgery and again at 1 year after surgery. The PRO surveys could be completed at office visits using internet-enabled tablets or at home. Email and text message reminders were sent to patients. The surveys consisted of the Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score for Joint Replacement (KOOS JR) and Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS-10) questionnaires. Details regarding the content of the KOOS JR and PROMIS-10 assessments are described elsewhere [[15], [16], [17]].

Study variables

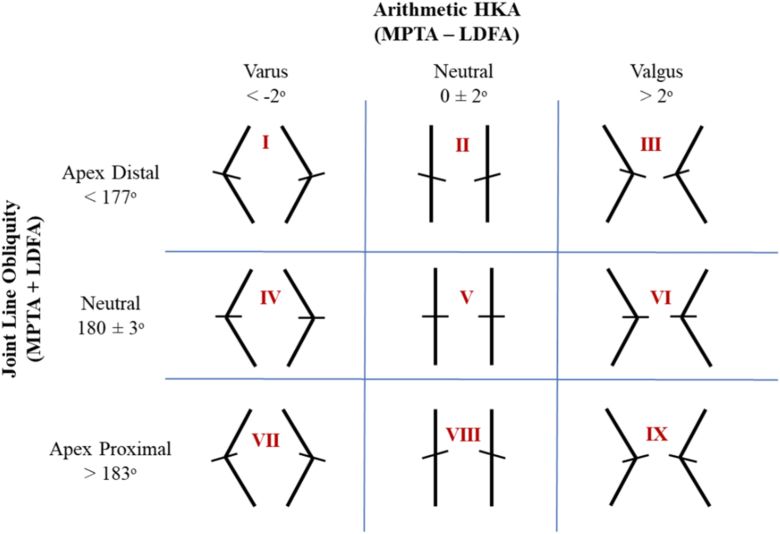

We extracted patient demographic data from medical records, including age, gender, and body mass index (BMI). Using a proprietary formula built into the updated Mako Total Knee 2.0 software (Stryker Corp., Kalamazoo, MI), native constitutional alignment of the operated knee (as aHKA) was calculated. Radiographic parameters including joint line orientation (JLO), medial proximal tibial angle, lateral distal femoral angle, were also measured within the system. Based on aHKA and JLO, we classified each subject under the Coronal Plane Alignment of the Knee (CPAK) classification as described by Macdessi et al [18] (Fig. 1). Final knee alignment after soft tissue balancing was collected. We calculated the difference between our final alignment and the calculated constitutional alignment. For the purposes of this study, a 2° threshold was used to define restoration of constitutional alignment based on typical precision of alignment measurements and clinically meaningful angular differences. Responses to PRO questionnaires were aggregated and scores for KOOS JR, PROMIS-10 Physical Health (PH), PROMIS-10 Mental Health (MH), European Quality of Life 5-dimension, and visual analog scale pain score measures were determined thereof.

Figure 1.

CPAK classification (adapted from Bellemans et al, JBJS 2021). MPTA, medial proximal tibial angle; LDFA, lateral distal femoral angle.

Data analyses

Variables were assessed for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test. We compared general characteristics between groups using 1-way t tests, Wilcoxon Rank sum test, and chi-square test as appropriate. Change in PRO scores were calculated as the difference between preoperative PRO scores and 1-year postoperative PRO scores, and presented as means and standard deviations (SD), or medians with interquartile ranges (IQR). We used t tests, Wilcoxon Rank sum test to compare groups based on the 2° proximity threshold to the constitutional alignment.

We evaluated the minimally clinical important difference (MCID) for KOOS JR, PROMIS-10 PH, and PROMIS-10 MH, the anchor method. We used anchor questions that were relevant but independent of PROs [19]. For KOOS JR scores, we used two anchor questions: “In general, how would you rate your physical health?” and “In general, would you say your quality of life is?”16 For PROMIS-10 PH and PROMIS-10 MH scores, we used the anchor question: “In general, would you say your health is?” Change in health status over time based on the anchor questions were calculated as the difference between the scores of the anchor questions taken preoperatively and scores at 1-year postoperatively. A difference of 0 was taken to imply no change at 1 year; a change of a +1 (improvement) or −1 (deterioration) implied a change. We calculated MCID using 3 different anchor method formulas, based on reported improvement from the anchor questions. The Youden index and the Farrar method depend on receiver-operator characteristics curves to determine the cutoff scores of MCID [19,20]. The average change method calculates MCID as the mean change of PRO scores for patients who reported an improvement based on the anchor questions [20]. Calculated MCID from the 3 methods employed were aggregated and are presented as means and ranges. All statistical analysis was performed using STATA version 18.0 (StataCorp LLC., College Station, TX).

In addition, we conducted a post hoc sensitivity analysis to assess the study's ability to detect clinically meaningful differences, using Cohen's d to determine effect sizes and minimum detectable differences.

A total of 188 robotic assisted total knee arthroplasties from 175 patients were included. A slight majority of patients were women (n = 96). The median BMI prior to surgical intervention was 30.8 and the mean age was 68. Utilizing the CPAK classification, the most common knee phenotypes found in the study population were type I (57; 30%), followed by type II (68; 36%) and type III (45; 24%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and alignment characteristics of the study population.

| Characteristic | Within 2° of constitutional (n = 98) | >2° from constitutional (n = 90) | Total (N = 188) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age at Surgery (years) | 67.4 (6.9) | 68.4 (8.3) | 67.9 (7.6) | .36 |

| Female | 46 (46.9%) | 50 (55.6%) | 96 (51.1%) | .24 |

| BMI | 31.5 (27.5-35.0) | 29.8 (26.9-34.4) | 30.8 (27.2-34.7) | .18 |

| Osteoarthritis diagnosis | 91 (92.9%) | 85 (94.4%) | 176 (93.6%) | .87 |

| Alignment parameters | ||||

| Constitutional alignment | <.001 | |||

| Valgus >5° | 0 (0.0%) | 22 (24.4%) | 22 (11.7%) | |

| Valgus ≤5° | 26 (26.5%) | 33 (36.7%) | 59 (31.4%) | |

| Neutral | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.1%) | 1 (0.5%) | |

| Varus ≤5° | 67 (68.4%) | 18 (20.0%) | 85 (45.2%) | |

| Varus >5° | 5 (5.1%) | 16 (17.8%) | 21 (11.2%) | |

| CPAK classification | <.001 | |||

| Class I | 35 (35.7%) | 22 (24.4%) | 57 (30.3%) | |

| Class II | 48 (49.0%) | 20 (22.2%) | 68 (36.2%) | |

| Class III | 7 (7.1%) | 38 (42.2%) | 45 (23.9%) | |

| Classes IV-VII | 8 (8.2%) | 10 (11.1%) | 18 (9.6%) | |

| Correction parameters | ||||

| Median proximity to constitutional alignment (°) | 0.1 (−0.8 to 0.8) | 2.9 (−2.0 to 4.3) | 0.7 (−0.9 to 2.9) | <.001 |

| Alignment modification (°) | 2.0 (1.0-3.0) | 4.5 (1.9-6.5) | 2.6 (1.3-4.9) | <.001 |

| Valgus knees | 1.4 (1.0) | 4.5 (3.1) | 3.5 (3.0) | <.001 |

| Varus knees | 2.5 (1.7) | 3.9 (2.9) | 3.2 (2.3) | <.001 |

Values presented as mean (SD), median (IQR), or n (%) as appropriate.

Results

No significant differences were observed between knees within 2° of constitutional alignment and knees >2° outside of constitutional alignment with respect to sex, age, BMI, or preoperative diagnosis. CPAK classification differed significantly with types I, II, and III being the most prevalent (P < .001) (Table 1). Additional study group characteristics can be found in Supplemental Table 1. There was minimal deviation from constitutional values (median 0.1°, IQR: −0.8° to 0.8°), yet substantial alignment modification was still needed during surgery (median 2.0°, IQR: 1.0°-3.0°). On the other hand, knees that ended >2° from constitutional alignment had a greater deviation (median 2.9°, IQR: −2.0° to 4.3°; P < .001) and required significantly greater alignment modification (median 4.5°, IQR: 1.9°-6.5°; P < .001) than the within 2° group. In subgroup analysis of alignment modification based on preoperative alignment, valgus knees in the >2° group required more correction (mean 4.5°) than varus knees in the same group (mean 3.9°). Among knees that remained within 2° of constitutional alignment, varus knees required greater correction (mean 2.5°) than valgus knees (mean 1.4°).

No significant differences were found in the PRO measures between knees which were balanced to within 2° of the patient’s constitutional alignment compared to knees balanced >2° outside of the patient’s constitutional alignment. Specifically, no significant differences were observed in the mean changes of scores reported at 1-year follow-up through KOOS JR, PROMIS PH, PROMIS MH, European Quality of Life 5-dimension scores, or visual analog scale pain scores between the two groups (Table 2). Most knees that were classified as CPAK type I were balanced within 2° of constitutional alignment (n = 35; 61%). However, no significant differences were seen in the mean changes of PRO scores when compared to those which were not balanced within 2° of constitutional alignment (Table 3). There were 71% of knees classified as CPAK type II balanced within 2° of constitutional alignment. PROMIS-10 PH showed significant differences in average preoperative and 1 year postoperative scores (Supplemental Table 2), but the mean change between the time points showed no difference between the groups (Table 3). In the CPAK type II knees, no significant differences were observed in the other PRO scores when compared to those which were not balanced within 2° of constitutional alignment. Only 16% of knees classified as CPAK type III were balanced within 2° of constitutional alignment, and as with CPAK 1 and 2, no significant differences in PROs were identified.

Table 2.

Mean change in patient-reported outcomes at 1 year.

| Outcome measure | Within 2° of constitutional (n = 98) | >2° from constitutional (n = 90) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| KOOS JR | |||

| Preoperative | 46.4 (15.0) | 44.2 (14.7) | .31 |

| 1 y postoperative | 71.4 (18.7) | 73.7 (16.8) | .37 |

| Mean change | 25.0 (19.6) | 29.5 (20.1) | .12 |

| Achieving MCID (31.85)a | 36.7% | 42.2% | .45 |

| Achieving MCID (30.15)b | 41.8% | 46.7% | |

| PROMIS Physical Healthc | |||

| Preoperative | 40.1 (6.9) | 40.6 (6.6) | .63 |

| 1 y postoperative | 48.1 (8.8) | 48.3 (8.7) | .89 |

| Mean change | 8.0 (8.0) | 7.7 (7.7) | .8 |

| MCID achievement | 44.90% | 38.90% | .4 |

| PROMIS Mental Healthd | |||

| Preoperative | 50.2 (8.0) | 51.6 (8.2) | .23 |

| 1 y postoperative | 52.9 (8.6) | 52.8 (9.1) | .97 |

| Mean change | 2.7 (7.3) | 1.2 (6.4) | .14 |

| MCID achievement | 41.80% | 40.00% | .8 |

| EQ-5D | |||

| Preoperative | 0.7 (0.1) | 0.7 (0.1) | .59 |

| 1 y postoperative | 0.75 (0.11) | 0.75 (0.11) | .88 |

| Mean change | 0.1 (0.1) | 0.1 (0.1) | .51 |

| Pain VAS score | |||

| Preoperative | 6.4 (2.0) | 6.5 (1.9) | .56 |

| 1 y postoperative | 3.1 (2.4) | 2.9 (2.5) | .63 |

| Mean change | −3.3 (2.8) | −3.6 (3.0) | .43 |

EQ-5D, European Quality of Life 5-dimension; VAS, visual analog scale.

MCID threshold based on anchor question: "Rate your physical health."

MCID threshold based on anchor question: "Rate your quality of life."

MCID threshold for PROMIS PH = 9.8.

MCID threshold for PROMIS MH = 3.05.

Table 3.

Mean change in PROs at 1 year by CPAK classification.

| Outcome measure | Within 2° of constitutional | >2° from constitutional | Total | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPAK class I | (n = 35) | (n = 22) | (n = 57) | |

| KOOS JR | 19.2 (19.5) | 29.3 (20.2) | 23.1 (20.2) | .064 |

| PROMIS Physical Health | 7.1 (7.7) | 8.8 (6.8) | 7.8 (7.3) | .41 |

| PROMIS Mental Health | 2.6 (8.4) | −0.4 (7.0) | 1.5 (8.0) | .17 |

| EQ-5D | 0.1 (0.1) | 0.1 (0.1) | 0.1 (0.1) | .88 |

| Pain VAS score | −3.3 (2.7) | −3.7 (2.7) | −3.5 (2.7) | .62 |

| CPAK class II | (n = 48) | (n = 20) | (n = 68) | |

| KOOS JR | 27.1 (19.3) | 27.4 (21.4) | 27.2 (19.8) | .96 |

| PROMIS Physical Health | 7.7 (8.9) | 6.9 (7.7) | 7.4 (8.5) | .74 |

| PROMIS Mental Health | 2.9 (7.1) | 0.8 (6.5) | 2.3 (6.9) | .26 |

| EQ-5D | 0.1 (0.1) | 0.1 (0.1) | 0.1 (0.1) | .65 |

| Pain VAS score | −3.0 (2.9) | −3.6 (3.0) | −3.2 (2.9) | .46 |

| CPAK class III | (n = 7) | (n = 38) | (n = 45) | |

| KOOS JR | 31.1 (18.5) | 32.2 (21.4) | 32.0 (20.8) | .9 |

| PROMIS Physical Health | 11.0 (3.5) | 8.1 (8.5) | 8.6 (8.0) | .39 |

| PROMIS Mental Health | 1.3 (5.6) | 1.6 (6.0) | 1.5 (5.9) | .91 |

| EQ-5D | 0.1 (0.1) | 0.1 (0.1) | 0.1 (0.1) | .26 |

| Pain VAS score | −4.9 (2.0) | −3.9 (3.3) | −4.1 (3.1) | .49 |

Values presented as mean (standard deviation).

EQ-5D, European Quality of Life 5-dimension; VAS, visual analog scale.

When the KOOS JR questionnaire was anchored to the statement “How would you rate your physical health?,” the mean MCID for the distribution methods was 31.85 (range, 28.42-34.83). Utilization of this anchor showed that 37% of knees within 2° of constitutional alignment and 42% of knees >2° outside of constitutional alignment achieved a MCID. When the KOOS JR questionnaire was anchored to the statement “How would you rate your quality of life?,” the mean MCID was 30.15 (range, 28.07-31.82). In this case, 42% of knees aligned within 2° and 47% of knees aligned >2° achieved a MCID (Table 2).

Both the PROMIS PH and PROMIS MH were anchored to the question: “How would you rate your overall health?” The mean MCID for PROMIS PH was 9.89 (range, 6.9- 12.87) leading to 45% of knees aligned within 2° of constitutional alignment and 39% of knees >2° outside of constitutional alignment achieved a MCID. The mean MCID for PROMIS MH was 3.05 (range, 1.15-5.31) leading to 42% of knees aligned within 2° of constitutional alignment and 40% of knees >2 outside of constitutional alignment achieved a MCID (Table 2).

In post hoc sensitivity analysis, assuming 80% power at α = 0.05, and our sample size of 188, our study was capable of detecting a standardized effect size (Cohen's d) of 0.41 or larger. This translates to minimum detectable differences of 8.1 points for KOOS-JR, 3.2 points for PROMIS PH, and 2.8 points for PROMIS MH. The observed effect sizes were smaller than our detection threshold: KOOS-JR (d = 0.23, representing a 4.5-point difference), PROMIS PH (d = −0.04, representing a 0.3-point difference), and PROMIS MH (d = −0.22, representing a 1.5-point difference). All observed effects represented small or negligible standardized differences.

Discussion

This retrospective analysis found that balancing close to constitutional alignment of the HKA after robotic assisted TKA did not result in superior PROs at 1-year follow-up when compared to knees which were not balanced within 2° of constitutional alignment. These results held true for the three most prominent CPAK knee phenotypes in the present study population. Although 9 unique CPAK knee phenotypes exist, most of the population belongs to 3 or 4 of these phenotypes. MacDessi et al [18] found the most common knee phenotypes amongst healthy and osteoarthritic knees to be type I (apex distal JLO & varus aHKA), type II (apex distal JLO & neutral aHKA), and type V (neutral JLO and neutral aHKA). Huber et al utilized a larger sample size and found the most common CPAK phenotypes amongst osteoarthritic patients to be type I, type II, and type III (apex distal JLO and valgus aHKA) [10]. Our results remain consistent with the previous literature as the most common phenotypes were found to be types I, II, and III. After isolating by the most prominent phenotypes, still no significant differences arose when comparing knees balanced within constitutional alignment compared to those balanced outside of constitutional alignment. Analysis regarding more extreme knee phenotypes, where constitutional alignment may prove more advantageous, could not be conducted due to the low frequency within the sample population.

Our post hoc sensitivity analysis provides important context for interpreting these findings. With our sample size, this study was adequately powered to detect effect sizes of d = 0.41 or larger, corresponding to differences of at least 8.1 points for KOOS-JR. The observed effect size of d = 0.23 (4.5-point difference) fell below this detection threshold, indicating our study may not have been adequately powered to detect this specific subtle difference. However, had there been a true 4.5-point difference, it remains far smaller than the calculated clinically meaningful differences in this study sample. The observed KOOS-JR difference is approximately 7-fold smaller than our calculated MCID of 30-32 points, and the minimal PROMIS differences (0.3 and 1.5 points for PROMIS PH and PROMIS MH respectively) are also smaller than their respective MCIDs. While our study may not have detected small statistical differences, these findings suggest that any true effects of constitutional alignment restoration are likely clinically negligible. In all, our study was appropriately designed to detect differences that would meaningfully impact patient outcomes. The consistent observation of small nonsignificant differences between the groups across various PRO measures in this study, supports the notion that recreation of constitutional alignment postoperatively does not produce clinically relevant improvements in PROs.

It was suspected that knees balanced to constitutional alignment would produce greater improvement to patient outcomes due to its implications on soft tissue balance. Macdessi et al showed that achieving constitutional alignment provided more equal intraoperative mediolateral compartmental loads at all knee positions. The same study reported that fewer soft tissue releases were required during TKA when constitutional alignment was utilized compared to mechanical alignment [11]. Chang et al [21] also found that constitutional alignment produced well balanced mediolateral soft tissue tension through knee flexion. These studies suggest that intraoperative bony cuts recreating prediseased constitutional alignment minimize the required soft tissue releases in order to achieve their balancing parameter with intraoperative sensors. However, in our study the surgeons, blinded to the constitutional alignment as the value of the aHKA is not directly used for preoperative planning or for intraoperative decision-making, utilized bony cuts as well as soft tissue releases in order to achieve desired soft tissue balance within alignment boundaries.

While many studies have documented that enhanced functional outcomes are associated with constitutional alignment, few studies have quantified the impact of constitutional alignment in relation to PROs [12,[22], [23], [24], [25]]. Macdessi et al [11] found no significant differences in PROs at 1 year between knees assigned to constitutional alignment compared to mechanical alignment although no direct comparison could be drawn from these outcomes. Dossett et al [26] reported a statistically nonsignificant improvement in satisfaction for knees constitutionally aligned compared to mechanically aligned knees and further found no significant differences in PROs over a 13-year follow-up period. Additionally, Dosset et al reported on surgical management which utilized 3D printed cutting guides for surgeons instead of robotic assisted planning. We aimed to determine whether knees reconstructed in close approximation to constitutional alignment resulted in superior PROs. We could find no significant differences in PROs. Both groups displayed a similar proportion of subjects who achieved MCID. The results of our study suggest that improved PROs after TKA are most likely related to achieving adequate soft tissue balance regardless of alignment proximity to prediseased alignment. Furthermore, our current PROs measurements may not be refined enough to pick up small differences in outcomes after TKA.

The differences observed in proximity to constitutional alignment and intraoperative alignment modification between the two groups offers some insights into both technical and clinical aspects of alignment in TKA. While knees in the within 2° group ended close to their constitutional alignment (median proximity 0.1°), they still required significant alignment modification during surgery (median 2.0°). This indicates that balancing near constitutional alignment often involves significant correction from the preoperative arthritic state. Knees that ended >2° from constitutional alignment required even greater modifications (median 4.5°). The subgroup analysis revealed that valgus knees in the >2° group required the most substantial corrections (mean 4.5°), consistent with the clinical understanding that pronounced valgus deformities often need more extensive modification to achieve stability [27]. Of note, in knees that remained close to constitutional alignment, varus deformities required greater correction (mean 2.5°) than valgus deformities (mean 1.4°), possibly reflecting different soft tissue adaptation patterns in these phenotypes or milder coronal alignments [9,10]. Despite these differences in correction parameters, we observed no significant differences in PROs. This suggests that reproducing constitutional alignment during a TKA may not be necessary for optimal knee function. Furthermore, it implies that the knee will likely tolerate a wider range of alignments without adversely affecting clinical outcomes [11,21,23]. Our findings align with Dossett et al [26], who similarly reported no significant differences in satisfaction or functional outcomes between different alignment approaches over an extended follow-up period. Finally, our results suggest that adequate soft tissue balancing within acceptable biomechanical and alignment parameters may be more critical than precise alignment restoration of the knee.

Recent research that compares outcomes of TKAs using various alignment approaches supports this overarching principle. For example, Lee at al demonstrated that FA approach produced superior PROS at 1 year compared to propensity matched manual and robotic-assisted mechanical alignment cohorts. In particular, notable improvements in KOOS and Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index scores were observed [28]. Kafelov et al also compared robotic assisted FA and manual restricted kinematic alignment approaches in a cohort of 120 patients and found significantly higher Forgotten Joint Scores in the FA group [29]. Our results specifically demonstrate that while FA approaches are beneficial, the exactitude of restoring constitutional alignment may not significantly impact patient outcomes, suggesting that achieving appropriate soft tissue balance within acceptable alignment parameters may be an important determinant of success.

Limitations

Our study has important limitations that should be acknowledged. The retrospective nature of this study introduces potential for selection bias and unknown confounding variables that could influence outcomes. A significant limitation of this study is the inherent challenge of isolating alignment as a single variable affecting outcomes. PROs reflect patients' subjective experiences, which are influenced by individual expectations, comorbidities, and factors unrelated to alignment [14,15]. While we used multiple validated measures and MCID calculations (using multiple anchor method formulas) to address this, these instruments remain imperfect tools for assessing the specific impact of alignment. We did not assess objective functional assessments or perform radiographic outcome assessments that could have strengthened our findings, although they are beyond the scope of this research. Finally, some patients may choose not to continue responding to PRO questionnaires for a variety of reasons, limiting the study size.

While we recognize that the current standard for reporting on PROs within the scientific context has widely been accepted as a follow-up duration of 2 years, multiple studies have recently established the nonsignificant differences in reported outcomes when comparing 1- and 2-year follow-up [30,31]. For these reasons we do not foresee significant changes in the results of the present study if repeated at 2-year follow-up.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that a bounded FA strategy in robotic-assisted TKA achieves excellent 1-year outcomes. Proximity to constitutional alignment (within 2° vs >2°) did not significantly affect PROs, despite significant differences in the magnitude of correction between groups. This suggests that achieving soft tissue balance within acceptable parameters of alignment and bony excision may be more critical for patient outcomes than precise restoration of prearthritic alignment. These findings could influence surgical decision-making by allowing greater flexibility in component positioning while emphasizing optimal soft tissue balance. Future studies with long-term follow-up and larger populations will be valuable to further delineate differences in outcomes between various alignment approaches.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Hallie B. Remer: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Bryan S. Brockman: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Investigation, Data curation, Conceptualization. Chukwuemeka U. Osondu: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Software, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Hannah Mosher: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Investigation. Yvette Hernandez: Writing – review & editing, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Data curation. Giovanni Paraliticci: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization. Charles M. Lawrie: Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Conceptualization. Juan C. Suarez: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Project administration, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests:

G. Paraliticci is a Zimmer/Biomet and Sanara MedTech consultant, serves in the Zimmer/Biomet and Sanara MedTech speakers bureau, is a Miami Orthopedic Society board member; J.C. Suarez receives royalties from Corin USA, serves in the Depuy speakers bureau, is a Depuy paid consultant, serves in the Arthroplasty Today Editorial Board; C.M. Lawrie receives royalties from Zimmer Biomet, is a Zimmer Biomet, Medtronic, Smith and Nephew, Mizuho OSI, Ignite Orthomotion, Ganymed Robotic paid consultant, is a Fios Health unpaid consultant, receives stock or stock options from Fios Health, is a AAHKS Fellowship Committee member and Anterior Hip Foundation Vice President; all other authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

For full disclosure statements refer to https://doi.org/10.1016/j.artd.2025.101776.

Appendix

Supplemental Table 1.

Additional patient characteristics.

| Characteristic | Within 2° of constitutional (n = 98) | >2° from constitutional (n = 90) | Total (N = 188) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laterality | .19 | |||

| Left | 57 (58.2%) | 43 (47.8%) | 100 (53.2%) | |

| Right | 41 (41.8%) | 47 (52.2%) | 88 (46.8%) | |

| ASA class | .51 | |||

| 1 | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.1%) | 1 (0.5%) | |

| 2 | 46 (46.9%) | 46 (51.1%) | 92 (48.9%) | |

| 3 | 52 (53.1%) | 43 (47.8%) | 95 (50.5%) | |

| Fixation | <.05 | |||

| Cemented | 27 (27.6%) | 40 (44.4%) | 67 (35.6%) | |

| Hybrid | 10 (10.2%) | 5 (5.6%) | 15 (8.0%) | |

| Press fit | 61 (62.2%) | 45 (50.0%) | 106 (56.4%) | |

| Patella resurfaced | .88 | |||

| No | 64 (65.3%) | 57 (63.3%) | 121 (64.4%) | |

| Yes | 34 (34.7%) | 33 (36.7%) | 67 (35.6%) | |

| Secondary diagnoses | .87 | |||

| Inflammatory arthritis | 1 (1.0%) | 1 (1.1%) | 2 (1.1%) | |

| Posttraumatic arthritis | 6 (6.1%) | 4 (4.4%) | 10 (5.3%) |

Values presented as n (%).

ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists.

Supplemental Table 2.

Preoperative and 1-year postoperative PRO scores by CPAK classification.

| Outcome measure | Within 2° of constitutional | >2° from constitutional | Total | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPAK class I | (n = 35) | (n = 22) | (n = 57) | |

| KOOS JR | ||||

| Preoperative | 45.6 (15.0) | 44.7 (15.8) | 45.2 (15.2) | .84 |

| 1 y postoperative | 64.7 (18.4) | 74.0 (15.7) | 68.3 (17.9) | .054 |

| PROMIS Physical Health | ||||

| Preoperative | 38.7 (6.3) | 42.2 (5.7) | 40.1 (6.3) | .039 |

| 1 y postoperative | 45.9 (8.5) | 51.0 (8.2) | 47.9 (8.7) | .028 |

| PROMIS Mental Health | ||||

| Preoperative | 48.6 (8.5) | 53.8 (6.7) | 50.6 (8.2) | .018 |

| 1 y postoperative | 51.2 (9.1) | 53.4 (8.0) | 52.0 (8.7) | .36 |

| EQ-5D | ||||

| Preoperative | 0.6 (0.1) | 0.7 (0.1) | 0.7 (0.1) | .067 |

| 1 y postoperative | 0.73 (0.12) | 0.77 (0.08) | 0.74 (0.11) | .17 |

| Pain VAS score | ||||

| Preoperative | 6.9 (1.7) | 6.4 (2.0) | 6.7 (1.9) | .3 |

| 1 y postoperative | 3.6 (2.6) | 2.7 (2.1) | 3.2 (2.4) | .18 |

| CPAK class II | (n = 48) | (n = 20) | (n = 68) | |

| KOOS JR | ||||

| Preoperative | 46.2 (13.5) | 48.0 (16.1) | 46.7 (14.2) | .64 |

| 1 y postoperative | 73.3 (18.8) | 75.4 (19.7) | 73.9 (18.9) | .68 |

| PROMIS Physical Health | ||||

| Preoperative | 41.0 (6.6) | 38.5 (7.2) | 40.2 (6.8) | .18 |

| 1 y postoperative | 48.6 (8.6) | 45.4 (9.5) | 47.7 (8.9) | .17 |

| PROMIS Mental Health | ||||

| Preoperative | 50.8 (6.9) | 50.1 (8.2) | 50.6 (7.2) | .71 |

| 1 y postoperative | 53.7 (7.5) | 50.9 (9.8) | 52.8 (8.3) | .21 |

| EQ-5D | ||||

| Preoperative | 0.7 (0.1) | 0.6 (0.1) | 0.7 (0.1) | .46 |

| 1 y postoperative | 0.75 (0.10) | 0.72 (0.13) | 0.74 (0.11) | .3 |

| Pain VAS score | ||||

| Preoperative | 6.0 (2.1) | 6.5 (2.0) | 6.2 (2.1) | .41 |

| 1 y postoperative | 3.0 (2.3) | 2.9 (2.4) | 3.0 (2.3) | .85 |

| CPAK class III | (n = 7) | (n = 38) | (n = 45) | |

| KOOS JR | ||||

| Preoperative | 49.5 (18.1) | 41.1 (13.8) | 42.4 (14.6) | .16 |

| 1 y postoperative | 80.6 (9.7) | 73.3 (16.5) | 74.4 (15.8) | .26 |

| PROMIS Physical Health | ||||

| Preoperative | 40.7 (7.0) | 40.7 (6.3) | 40.7 (6.3) | .99 |

| 1 y postoperative | 51.7 (6.4) | 48.8 (8.4) | 49.3 (8.1) | .4 |

| PROMIS Mental Health | ||||

| Preoperative | 53.8 (9.1) | 52.6 (7.6) | 52.8 (7.7) | .72 |

| 1 y postoperative | 55.1 (4.0) | 54.2 (9.4) | 54.3 (8.8) | .81 |

| EQ-5D | ||||

| Preoperative | 0.7 (0.1) | 0.7 (0.1) | 0.7 (0.1) | .82 |

| 1 y postoperative | 0.79 (0.07) | 0.75 (0.11) | 0.76 (0.10) | .35 |

| Pain VAS score | ||||

| Preoperative | 6.6 (1.5) | 6.8 (1.9) | 6.8 (1.8) | .72 |

| 1 y postoperative | 1.7 (1.9) | 2.9 (2.7) | 2.7 (2.6) | .27 |

Values presented as mean (standard deviation).

EQ-5D, European Quality of Life 5-dimension; VAS, visual analog scale.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Gunaratne R., Pratt D.N., Banda J., Fick D.P., Khan R.J.K., Robertson B.W. Patient dissatisfaction following total knee arthroplasty: a systematic review of the literature. J Arthroplasty. 2017;32:3854–3860. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2017.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Choi Y.J., Ra H.J. Patient satisfaction after total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Relat Res. 2016;28:1–15. doi: 10.5792/ksrr.2016.28.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Insall J.N., Binazzi R., Soudry M., Mestriner L.A. Total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1985;192:13–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bargren J.H., Blaha J.D., Freeman M.A. Alignment in total knee arthroplasty. Correlated biomechanical and clinical observations. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1983;173:178–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Evans J.T., Walker R.W., Evans J.P., Blom A.W., Sayers A., Whitehouse M.R. How long does a knee last? A systematic review and meta-analysis of case series and national registry reports with more than 15 years of follow-up. Lancet. 2019;393:655–663. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32531-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berend M.E., Ritter M.A., Meding J.B., Faris P.M., Keating E.M., Redelman R., et al. Tibial component failure mechanisms in total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;428:26–34. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000148578.22729.0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ritter M.A., Faris P.M., Keating E.M., Meding J.B. Postoperative alignment of total knee replacement. Its effect on survival. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;299:153–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lotke P.A., Ecker M.L. Influence of positioning of prosthesis in total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1977;59:77–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bellemans J., Colyn W., Vandenneucker H., Victor J. The Chitranjan Ranawat award: is neutral mechanical alignment normal for all patients? The concept of constitutional varus. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470:45–53. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-1936-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huber S., Mitterer J.A., Vallant S.M., Simon S., Hanak-Hammerl F., Schwarz G.M., et al. Gender-specific distribution of knee morphology according to CPAK and functional phenotype classification: analysis of 8739 osteoarthritic knees prior to total knee arthroplasty using artificial intelligence. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2023;31:4220–4230. doi: 10.1007/s00167-023-07459-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.MacDessi S.J., Griffiths-Jones W., Chen D.B., Griffiths-Jones S., Wood J.A., Diwan A.D., et al. Restoring the constitutional alignment with a restrictive kinematic protocol improves quantitative soft-tissue balance in total knee arthroplasty: a randomized controlled trial. Bone Joint J. 2020;102-b:117–124. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.102B1.BJJ-2019-0674.R2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Howell S.M., Howell S.J., Kuznik K.T., Cohen J., Hull M.L. Does a kinematically aligned total knee arthroplasty restore function without failure regardless of alignment category? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471:1000–1007. doi: 10.1007/s11999-012-2613-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blakeney W., Clément J., Desmeules F., Hagemeister N., Rivière C., Vendittoli P.A. Kinematic alignment in total knee arthroplasty better reproduces normal gait than mechanical alignment. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2019;27:1410–1417. doi: 10.1007/s00167-018-5174-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maderbacher G., Keshmiri A., Krieg B., Greimel F., Grifka J., Baier C. Kinematic component alignment in total knee arthroplasty leads to better restoration of natural tibiofemoral kinematics compared to mechanic alignment. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2019;27:1427–1433. doi: 10.1007/s00167-018-5105-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hung M., Bounsanga J., Voss M.W., Saltzman C.L. Establishing minimum clinically important difference values for the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Physical Function, hip disability and osteoarthritis outcome score for joint reconstruction, and knee injury and osteoarthritis outcome score for joint reconstruction in orthopaedics. World J Orthop. 2018;9:41–49. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v9.i3.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Only A.J., Albright P., Guenthner G., Parikh H.R., Kelly B., Huyke F.A., et al. Interpreting the Knee Osteoarthritis Outcome Score Joint Replacement: minimum clinically important difference values vary over time within the same patient population. J Orthop Exp Innov. 2021;2:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pak S.S., Miller M.J., Cheuy V.A. Use of the PROMIS-10 global health in patients with chronic low back pain in outpatient physical therapy: a retrospective cohort study. J Patient Reported Outcomes. 2021;5:81. doi: 10.1186/s41687-021-00360-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.MacDessi S.J., Griffiths-Jones W., Harris I.A., Bellemans J., Chen D.B. Coronal Plane alignment of the knee (CPAK) classification. Bone Joint J. 2021;103-B:329–337. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.103B2.BJJ-2020-1050.R1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Molino J., Harrington J., Racine-Avila J., Aaron R. Deconstructing the minimum clinically important difference (MCID) Orthop Res Rev. 2022;14:35–42. doi: 10.2147/ORR.S349268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Franceschini M., Boffa A., Pignotti E., Andriolo L., Zaffagnini S., Filardo G. The minimal clinically important difference changes greatly based on the different calculation methods. Am J Sports Med. 2023;51:1067–1073. doi: 10.1177/03635465231152484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chang J.S., Kayani B., Wallace C., Haddad F.S. Functional alignment achieves soft-tissue balance in total knee arthroplasty as measured with quantitative sensor-guided technology. Bone Joint J. 2021;103-b:507–514. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.103B.BJJ-2020-0940.R1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu B., Feng C., Tu C. Kinematic alignment versus mechanical alignment in primary total knee arthroplasty: an updated meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Orthop Surg Res. 2022;17:201. doi: 10.1186/s13018-022-03097-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Delport H., Labey L., Innocenti B., De Corte R., Vander Sloten J., Bellemans J. Restoration of constitutional alignment in TKA leads to more physiological strains in the collateral ligaments. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2015;23:2159–2169. doi: 10.1007/s00167-014-2971-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dossett H.G., Swartz G.J., Estrada N.A., LeFevre G.W., Kwasman B.G. Kinematically versus mechanically aligned total knee arthroplasty. Orthopedics. 2012;35:e160–e169. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20120123-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Howell S.M., Papadopoulos S., Kuznik K.T., Hull M.L. Accurate alignment and high function after kinematically aligned TKA performed with generic instruments. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013;21:2271–2280. doi: 10.1007/s00167-013-2621-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dossett H.G., Arthur J.R., Makovicka J.L., Mara K.C., Bingham J.S., Clarke H.D., et al. A randomized controlled trial of kinematically and mechanically aligned total knee arthroplasties: long-term follow-up. J Arthroplasty. 2023;38:S209–S214. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2023.03.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Greenberg A., Kandel L., Liebergall M., Mattan Y., Rivkin G. Total knee arthroplasty for valgus deformity via a lateral approach: clinical results, comparison to medial approach, and review of recent literature. J Arthroplasty. 2020;35:2076–2083. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2020.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee J.H., Kwon S.C., Hwang J.H., Lee J.K., Kim J.I. Functional alignment maximises advantages of robotic arm-assisted total knee arthroplasty with better patient-reported outcomes compared to mechanical alignment. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2024;32:896–906. doi: 10.1002/ksa.12120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kafelov M., Batailler C., Shatrov J., Al-Jufaili J., Farhat J., Servien E., et al. Functional positioning principles for image-based robotic-assisted TKA achieved a higher Forgotten Joint Score at 1 year compared to conventional TKA with restricted kinematic alignment. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2023;31:5591–5602. doi: 10.1007/s00167-023-07609-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seetharam A., Deckard E.R., Ziemba-Davis M., Meneghini R.M. The AAHKS clinical research award: are minimum two-year patient-reported outcome measures necessary for accurate assessment of patient outcomes after primary total knee arthroplasty? J Arthroplasty. 2022;37:S716–S720. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2022.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spece H., Kurtz M.A., Piuzzi N.S., Kurtz S.M. Patient-reported outcome measures offer little additional value two years after arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bone Joint J. 2025;107-B:296–307. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.107B3.BJJ-2024-0910.R1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.