Abstract

Immune cells are recruited to sites of inflammation in a stepwise process involving a symphony of signals and receptors. In the systemic circulation, the step at which immune cells migrate out of the blood and across the endothelium, transendothelial migration, occurs via homophilic interactions between leukocyte PECAM-1 and CD99 and endothelial cell PECAM-1 and CD99. Previous work showed that rolling and adhesion of immune cells in the lung vasculature does not follow the classical paradigm of inflammatory recruitment; however, the transmigration step of this process has largely gone understudied. In this study, we demonstrate that polymorphonuclear cells (PMNs) utilize PECAM-1 and CD99 when transmigrating in response to murine chemical, bacterial and ischemia/reperfusion lung injury (IRI). We demonstrate that recruitment of PMNs in response to both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria is PECAM-1- and CD99- dependent. We implemented a method of intravital microscopy (IVM) of the pulmonary vasculature after IRI with which we directly visualized and quantified transmigration. We demonstrate, in real time, that PMN enter the alveoli by crossing alveolar capillaries. Because PMNs are known to be independent mediators of both tissue damage and resolution of inflammation, we tested these effective blocking antibodies for survival effects in models of 50 – 60% mortality, but found none. In summary, our study shows that the classical transmigration protein interactions are necessary for transmigration of PMNs into the airspace during response to four distinct inflammatory stimuli.

Keywords: Inflammatory cascade, polymorphonuclear cells, pulmonary inflammation, transmigration, PECAM-1, CD99

NEW & NOTEWORTHY

Previous studies have shown that neutrophil extravasation in the lung was selectin-independent and the requirement for leukocyte integrins was stimulus-dependent. This study demonstrates that PECAM-1 and CD99 are required for PMN transmigration during chemical, bacterial, and ischemia/reperfusion lung inflammation. We show directly in real time, using intravital microscopy, that neutrophils extravasate from alveolar capillaries. Blocking antibodies against PECAM-1 or CD99 prevented transmigration into the lung airspace, just as they prevent transmigration in the systemic circulation.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Pneumonia is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in the world (1). There are multiple types of pneumonia, including damage to the airspace of the lungs by gastric contents, bacteria, viruses, and/or fungi (2). For all types of pneumonia, treatment consists of supportive therapy, and antibiotics, antifungals or antivirals during infection. One type of pneumonia, gastric aspiration pneumonia, involves the leaking of the acidic contents of the stomach into the oropharynx from which it is then aspirated into the airspaces of the lungs. In addition to the inflammation resulting from direct chemical damage to the lung, there is often co-infection by oropharyngeal bacteria (3). Gastric aspiration pneumonia occurs in more than 50,000 patients every year and is most common in hospitalized and/or immunodeficient patients. The most common type of pneumonia, bacterial bronchopneumonia, is an infectious form of pneumonia in which bacterial infiltration of the lungs results in PMN recruitment and edema in the airspace (4). Infectious pneumonia is common, affecting 5 million people per year in the US, with 20% of cases requiring hospitalization and 12–40% of hospitalized cases resulting in death (1).

During pneumonia, immune cells are recruited to the airspace of the lungs to respond to and clear infection (5). In the typical leukocyte recruitment cascade in the systemic circulation, polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs) are the first responders to sites of inflammation where they slow, roll, adhere, and transmigrate into the tissue (6). These actions are performed because of interactions between proteins on the leukocyte and proteins on the endothelial cells lining the vasculature. However, the lung is immunologically unique. Previous work shows that rolling and adhesion of leukocytes, including PMNs, differs from the systemic vasculature in the pulmonary vasculature. There is no selectin-dependent rolling, and the dependence on adhesion molecules like β2 integrins is stimulus specific; its requirement has been shown to be based on whether the primary infection is by Gram-positive or Gram-negative bacteria (7, 8). In the lungs, leukocytes exit the vasculature to enter the tissue via the smaller true capillaries rather than the larger postcapillary venules (9, 10). Transendothelial migration (TEM, or transmigration) has been shown in the systemic circulation to require homophilic interactions between PECAM-1 and CD99 on the leukocyte and endothelial cell (11, 12, 13, 14). However, previous work has indicated that the requirement of PECAM-1 for transmigration of immune cells in the lungs is not clear-cut. Studies involving eosinophil recruitment to the lungs during asthma suggested that recruitment of these cells to the airspace is PECAM-1-independent (15). Other work performed using polyclonal rabbit anti-human PECAM-1 blocking antibodies in rats found that PMN infiltration into the lung is PECAM-1-dependent (16). Additionally, a murine study of PMN infiltration in response to S. pneumoniae infection found that transmigration was PECAM-independent (17). Several of these previous works have utilized PECAM-1 blocking antibodies in the C57Bl/6 strain of mice that are now known to be genetically resistant to the blocking antibody’s function (18, 19). Additionally, one study focused primarily on eosinophils, which respond at a later timepoint and function differently than PMNs (20). As a result, the mechanism(s) of transmigration of PMNs in the lungs has remained unclear.

Another unusual immunological feature of the lungs may provide insight to this heterogeneity: the lungs contain a marginated pool of PMNs that are present in the vasculature even in non-inflamed conditions. It has been hypothesized that this physiologic margination of PMNs is due to the passive stalling of PMNs in the overly narrow capillaries as they must deform their shape through polymerization of actin to continue their passage through the vessels that are narrower than the PMNs’ width (21). It has been posited that this natural slowing also contributes to the selectin independence of leukocyte response in pulmonary inflammation.

Understanding the role of these transmigration proteins in the lungs is of clinical importance, because partial leukocyte blockades can be utilized therapeutically to evade the injurious effects of PMN recruitment to tissue. Because the mechanisms of leukocyte recruitment have been previously shown to vary based on the nature of the inflammatory stimulus, we thought it important to study distinct forms of lung injury when testing the role of PECAM-1 and CD99 in transmigration in the lung. The current study aimed to identify the mechanisms by which PMNs transmigrate during chemical lung injury, Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacterial bronchopneumonia, and lung ischemia/reperfusion injury. To address confusion around the requirement for PECAM-1 and CD99 in the pulmonary vasculature, we also aimed to directly visualize transmigration in the lung capillaries. This study confirms that, in all four inflammatory models, PMNs transmigrate into the lung tissue via the same mechanism as the systemic vasculature, requiring both PECAM-1 and CD99 to enter the lung airspace. We visualized transmigration of PMNs into the airspace by IVM and confirmed that this occurs in the alveolar capillaries.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee (IACUC) of Northwestern University. Mice were housed in the Center for Comparative Medicine at Northwestern University (Chicago, IL) under the care of veterinarians and trained animal technicians. All animals were cared for according to Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AALAC) standards and protocols. Mice were fed a standard chow diet and maintained on a 24-hour light/dark cycle. All mice used in experiments were 25–35g, 3–4 months of age, and of both sexes. All experiments performed in wild-type mice utilized FVB/n wild-type mice (RRID:IMSR_JAX:001800, Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME). FVB/n wild-type mice are known to mimic the human vasculature in expression and function of PECAM-1 (19). C57Bl/6 LysM-eGFP mice were obtained from Dr. Paul Kubes (Calgary, AB, Canada); this strain has been described previously (22). These mice were backcrossed by our lab with wild-type FVB/n for nine generations to generate the FVB LysM-eGFP strain (19). Carriers of the LysM-eGFP allele were identified in each backcross by analysis of a blood smear using fluorescence microscopy. The myelomonocytic cells of these mice produce green fluorescent protein (eGFP) under the lysozyme M (LysM) locus, rendering this subset of leukocytes fluorescent. Because they are in the FVB/n background, they can be used for blocking experiments, whereas C57Bl/6 LysM-eGFP mice are resistant to PECAM and CD99 blocking antibodies (19). The mice were euthanized by Avertin anesthetic overdose and cervical dislocation to avoid lung inflammation by CO2 inhalation.

Murine Chemical Lung Injury

Mice were anesthetized using vaporized Isoflurane in a Moduflex veterinary anesthesia ventilator with 98% room air. Deep anesthesia was confirmed by deep breathing pattern and toe pinch (approximately 5 minutes after beginning anesthetic). Mice were then positioned in an intubation stand by placing their incisors in a looped suture to keep them in an upright supine position. The vocal cords were visualized by pulling the tongue to the side and placing a flat spatula in the palate. 25 μl of 0.1N HCl was injected with micropipette oropharyngeally (as has been described previously) (23). The tongue was held while the nares were covered to encourage deep oral breathing for three inhales. The mouse was then placed back under Isoflurane anesthesia for 3 minutes. After 3 minutes, the instillation of 25 μl of 0.1N HCl was repeated. Control mice underwent the same procedure but received instillations of 25 μl of PBS. The mice were recovered on a heating pad until conscious.

Murine Bacterial Bronchopneumonia

Bacteria from thawed frozen glycerin (30%) stock (ATCC, Manassas, VA) was streaked on the appropriate agar (TSA sheep blood agar for S. pneumoniae and LB agar for P. aeruginosa) using a sterilized loop. This was grown overnight; 24 h later an isolated colony was chosen and inoculated in 8 mls of the appropriate liquid media (TS broth for S. pneumoniae and LB broth for P. aeruginosa) to be shaken at 200 rpm and 37⁰C overnight. 3 hours prior to experiment, 1 ml of the liquid media with bacteria was diluted into 5 ml of the appropriate liquid media and shaken at 100 rpm and 37⁰C to ensure bacteria were instilled at log phase. Using a previously established CFU to OD600 graph, the log phase cultures were diluted to contain 5–6×106 CFUs of bacteria in 50 μl PBS for P. aeruginosa (ATCC 10145) and 5–6×108 CFUs of bacteria in 50 μl PBS for S. pneumoniae (ATCC 49619). CFU calculation was confirmed by serial dilution drip-plate. The media instilled was serially diluted from 1×100 to 1×10−8 and plated on the appropriate agar plate. The plate was incubated overnight at 37⁰C, and colonies were counted 24h later. For P. aeruginosa induced pneumonia, mice were anesthetized with Avertin and 25 μl of bacterial solution was added dropwise to the nares. Mice recovered for 3 minutes before 25 μl more bacterial solution was added dropwise to the nares. For S. pneumoniae-induced pneumonia, mice were anesthetized with Avertin, intubated with a catheter, and 25 μl of bacterial solution was instilled into the catheter. Mice recovered for 3 minutes before 25 μl more of bacterial solution was added to the catheter. Control mice underwent the same procedure but received instillations of 25 μl of PBS. Mice recovered on a heating pad.

Murine Warm Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury

Mice were anesthetized with Avertin (0.5 ml/25 g body weight). The mouse was checked for depth of anesthesia via toe pinch and intubated for mechanical ventilation. Mice were connected to a Rovent PhysioSuite (Kent Scientific, Torrington, CT) calibrated to perform mechanical ventilation. The PhysioSuite performs ventilation based on scaling by animal size; the formula for which has been described previously (24). To determine the scaling, tidal volume (ml) is equal to 7.69 * body mass (kg)1.04 while respiration rate is equal to 53.5 * body mass (kg) −0.26. The machine was set to pressure priority, where the default pressure of 15cmH2O is prioritized (based on mammalian standards). The machine dynamically alters tidal volume based on the presence of air in the lungs. PEEP was set at 3–4cm H2O. Proper intubation was confirmed by temporarily blocking the intubation catheter and checking for agonal breathing. The mouse was placed prone on a heating pad, the back was shaved, and the left side of the posterior chest was opened with an approximately 1 cm cut. The connective tissue and muscle wall was dissected apart and the left ribs exposed. An approximately 0.5 cm cut was made in between the first and second rib and sutures were used to gently pull apart the ribs and open the cavity. A bulldog clamp (Fine Science Tools, Foster City, CA) was placed on the hilum to the left lobe and covered with a PBS-soaked piece of gauze. Thirty minutes later, the clamp was gently removed, taking care to not damage the hilum, and blood and airflow was confirmed to be restored to the left lobe. The ribs and skin were sutured with interrupted stitches to prevent herniation, and the mouse was left to recover on a heating pad before imaging.

Antibody Blockades

Anti-PECAM-1 (2H8, anti-CD31) and anti-CD99 (3F11) monoclonal antibodies were used in blocking experiments. Antibodies were produced in-house by hybridoma methods. These hybridoma-produced 2H8 and 3F11 antibodies have been extensively validated by our lab previously (19). Blockade treated mice were given a retro-orbital injection of 40 μg of 2H8 or 3F11 antibody in 100 μl of PBS at the time of inflammatory stimulus. In experiments where studies extended past 24 h, mice were given an additional retro-orbital injection (in alternating eyes) of 40 μg of either antibody in 100 μl of PBS every 24 h afterwards. Control mice were given a retro-orbital injection of 40 μg of IgG isotype control (ThermoFisher Scientific, cat. #14–4888-81) at the time of inflammatory stimulus, and every 24 h afterwards if the experiment extended beyond 24 h.

Intravital Microscopy (IVM) of the Lung

Mice were anesthetized with Avertin (0.5 ml/25 g body weight). The mouse was checked for depth of anesthesia via toe pinch and intubated for mechanical ventilation. Mice were connected to a Rovent Physiosuite (Kent Scientific, Torrington, CT) calibrated to perform mechanical ventilation according to the weight of the mouse. Proper intubation was confirmed by observing the pattern of breathing in relation to the tempo of the ventilator. The left side of the anterior chest was then exposed by gross dissection. The tissue was carefully dissected away until the ribs of the left side of the chest were exposed, and a small cut was made to the third rib. The connective tissue between the third and fourth rib was cut across the curve of the lung (visible underneath the ribs) and the lung was gently massaged to separate it from the ribs and allow it to retain its physiologic positioning. A small window was then cut from the ribs to expose the left lung, taking care not to sever the spine. Kimwipes were used to keep the field clear of blood, taking care not to touch the lung tissue directly. A coverslip was attached to the imaging stand (custom made at the NU Machine Shop, Evanston, IL) using high vacuum grease (Molykote, Wilmington, DE) and the mouse was placed in position in the stand. For the vessel labeling, 10 mg of 2M kD MW fluorescein dextran (D7137, ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA) was reconstituted in 1 ml of 30% glycerol PBS. 75 μl of this dextran with 75 μl of PBS was injected retro-orbitally immediately prior to imaging. The mechanical ventilator was connected to the Nikon software via 10-pin cord and the ventilator was synced to perform breath holds during imaging using the pulse feature of Nikon’s software. Imaging was performed on the upright Nikon A1R Multiphoton microscope in the NU Center for Advanced Microscopy (CAM). IVM was performed using a 25x magnification water immersion lens (Nikon, MRD77220, WD: 2.0 mm, NA: 1.1) with ten 1 μm steps in the z-plane. Stacks were performed every 25 seconds. Mice were imaged no longer than 120 minutes and euthanized immediately following imaging with anesthetic overdose and cervical dislocation.

Analysis of IVM Videos

IVM videos were analyzed using Nikon NIS Elements software (2025 v6.10.01, Nikon, Melville, NY, RRID:SCR_014329). Transit distance of leukocytes was measured by first applying a binary mask to the GFP channel through the General Analysis function with a fluorescence threshold of 1000, circularity of 0.2, and minimum size of 5 μm. Binary objects were then tracked using the advanced tracking add-on with requirements for frame-matching set to 1 and maximum speed set to 3 μm/s. Stagnation was defined as any GFP+ cell that did not move more than 5 μm for the entire duration of the 15 minute video, while lack of stagnation was defined as any GFP+ cell that moved more than 5 μm at any point during the 15 minute period. Leukocytes were characterized as transmigrating if they were clearly within the vasculature, changed to a squeezed oval shape (see Fig. 6A), then were clearly outside the vasculature for the rest of the video as determined by examination of individual z-planes. Vessel diameters were measured where the leukocyte transmigrated using the distance function on the RFP+ channel. For analysis involving time post-reperfusion, videos were coded as taking place in hour 1 (0–60 minutes), hour 2 (61–120 minutes), hour 3 (121–180 minutes), or hour 4 (181–240 minutes) post-reperfusion. 3D renderings of videos showing the full z-stack were analyzed in Imaris (v10.2.0, RRID:SCR_007370) by creating a volume projection surface with machine learning trainable segmentation on the RFP channel (vasculature) and the GFP channel (leukocytes).

Figure 6. IVM visualization of transmigration during lung ischemia/reperfusion injury.

The white arrows represent the leukocytes in the vessels, followed by green arrows for leukocytes squeezing through the endothelium, and the blue arrows for leukocytes in the airspace. A. Schematic representing the classification of leukocytes as “transmigrating.” Leukocytes were classified as transmigrating if they were initially clearly intravascular, followed by a shape change to move through the endothelium, then either Motion A, spreading out on the alveolar walls, or Motion B, suspended in the alveolus shaking with the effects of breathing motions, as determined by analysis of individual z-planes. B. Representative maximum intensity projection videos of Motion A or Motion B. White arrows show leukocyte transmigrating. Scale bars represent 15 μm. See supplemental videos 1–4. C. Number of leukocytes seen transmigrating. Dots represent individual leukocytes from analysis of three 15-minute videos of individual mice per condition. Statistical tests by Mann-Whitney test. D. Size of the vessel through which leukocytes were seen transmigrating as measured by the dextran label. Dots represent individual leukocytes from analysis of three 15-minute videos of individual mice per condition. Statistical test by Mann-Whitney test.

Histology

Lungs were inflated with 0.7 ml of 10% neutral buffered formalin and removed. Tissue was allowed to fix in formalin for 24 hours followed by 15% and 30% sucrose in PBS. It was then submitted to the Mouse Histology and Phenotyping Laboratory (MHPL) at NU for paraffin embedding, sectioning, and hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. H&E slides were imaged on a TissueGnostics automated slide-viewing microscope in the Center for Advanced Microscopy and stitched to produce full lung images in TissueFAXS (TissueGnostics, Vienna, Austria).

Bronchoalveolar Lavage (BAL)

Bronchoalveolar lavages (BALs) were taken from mice as previously described (25). Briefly, 0.7 ml of 100 μM EDTA PBS was chilled. Mice were sacrificed, and the lungs and trachea were exposed via surgical thoracotomy. A small incision was made using fine point scissors in the space between cartilage rings of the trachea. A Luer stub was inserted into the incision, and the 100 μM EDTA PBS was injected into the airspace of the lungs slowly and evenly using a 1 ml syringe. The solution was then retracted back into the syringe and then washed back out into the lungs three times. After the third retraction, the syringe and Luer stub were removed from the trachea.

Flow Cytometry

Cells for flow cytometry were obtained from bronchoalveolar lavages taken in 100 μM EDTA in PBS. Lung tissue was digested for 45 mins in Accutase (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 37°C and filtered through a 100 μm strainer. Cells were centrifuged and resuspended in flow buffer of 5% fetal bovine serum in PBS for flow cytometry. In experiments describing intravascular PMNs, 12.5 μl of anti-Ly6G APC (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lake, NJ) was given retro-orbitally 3 minutes before sacrifice.

Flow cytometry was performed on an LSR Fortessa X-20 flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lake, NJ). PMNs were gated using forward scatter/side scatter for size and singlets, Live/Dead Zombie Violet (BV420), anti-CD45 PerCP Cy5.5, anti-CD11b FITC, and anti-Ly6G PE. In the experiments describing intravascular PMNs, an additional gate for APC was added. CountBright absolute counting beads (C36950, ThermoFisher Scientific) were used according to manufacturer instructions to obtain absolute counts of cells present in lavages and left lung tissue. Data were analyzed by FlowJo software version 10.8.2 (FlowJo, Ashland, OR, RRID:SCR_008520).

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as mean +/− standard deviation. All data were tested for normality before proceeding with a statistical test. In cases of normality, data were tested appropriately using Student’s t-test or one-way or two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s test. In cases of non-normality, data were analyzed using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test or appropriate test. Significance was set at p<0.05. Survival graphs include percentage of survival +/− STD. Data were excluded only if they were more than two standard deviations above or below the mean. Attrition of mice in the BAL and tissue harvesting experiments is reflected by the survival graphs in Fig. 9. All mice that survived were otherwise included. Group assignment within experiments was random. Statistical analysis was performed in Prism v10 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, RRID:SCR_002798).

Figure 9. Survival of lung injury with blocked transmigration.

Inflammation was induced and mice were given either control antibody or blocking antibody injections daily for 7 days or until deceased. Solid lines indicate survival of control antibody treated mice, while dotted line indicates mice treated with blocking antibodies. All data tested for significance by Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. A. Probability of survival of hydrochloric acid injury with or without treatment by PECAM-1 blocking antibodies. Data represents 3 experiments with n=20 mice. B. Probability of survival of hydrochloric acid injury with or without treatment by CD99 blocking antibodies. Data represents 3 separate experiments with n=20 mice C. Probability of survival of P. aeruginosa injury with or without treatment by PECAM-1 blocking antibodies. Data represents 2 experiments with n=22 mice. D. Probability of survival of P. aeruginosa injury with or without treatment by CD99 blocking antibodies. Data represents 2 experiments with n=24 mice.

RESULTS

Bacterial and chemical murine models of lung injury induce transmigration of PMNs into the airspace

Previous work has identified differences in the inflammatory cascade during lung injury in the pulmonary vasculature (26). That work primarily focused on the steps earlier in the inflammatory cascade, like rolling and adhesion, rather than the later step of transmigration. To better assess the mechanisms of transmigration of PMNs in the lung vasculature, three models of lung injury were implemented. First, two models of bacterial bronchopneumonia were implemented, with anesthetized mice inoculated with either P. aeruginosa (1×106 CFUs) in PBS given dropwise through the nares or S. pneumoniae (1×108 CFUs) in PBS given intratracheally. Additionally, a model of gastric aspiration pneumonia was used to induce chemical lung injury. In pilot experiments (not shown), maximum PMN accumulation in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid was seen at 24 hours after application of the inflammatory stimulus. Therefore, this timepoint was chosen for the experiments in this section.

BALs are an excellent technique for quantifying transmigration, as they identify all cells present in the airspace, which requires transmigration for cells like PMNs that are not tissue-resident in the lungs under non-inflamed conditions. All three models were effective at recruiting PMNs to the lungs as seen by quantitation of BALs by flow cytometry (Fig. 1A,B). Consistent with this, examination of lungs by confocal microscopy (Fig. 1C) and H&E staining of lung tissue sections (Fig. 1D) showed influx of PMN in the affected regions. In the model of gastric aspiration pneumonia, the alveolar walls were damaged with significant necrosis and chemical injury. In the models of bacterial bronchopneumonia, there were still occasional bacteria seen in the alveoli at 24 hours.

Figure 1. PMN recruitment during inflammatory lung injury.

Inflammation was induced via one of three methods: hydrochloric acid oropharyngeal instillation, S. pneumoniae (Gram-positive) intratracheal instillation, or P. aeruginosa (Gram-negative) oropharyngeal instillation. After 24 hours, bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid was taken for flow cytometry or tissue sections were taken for imaging. Data represent two separate experiments with dots representing individual mice. Statistics performed by Mann-Whitney test. A. PMN recruitment to BAL fluid 24 hours post bacterial injury. PMNs were gated via flow cytometry on CD45+CD11b+Ly6G+ live cells to discriminate against other recruited inflammatory cells. B. PMN recruitment to BAL fluid 24 hours post acid injury. C. Widefield fluorescence microscopy of control and chemical injury treated LysM-eGFP FVB/n mice 24 hours after inflammatory stimulus. Scale bars = 25 μm. D. Histological sections of murine lung tissue. Scale bars = 50 μm.

PMN transmigration in bacterial bronchopneumonia is PECAM-1- and CD99-dependent

In the typical inflammatory response found in the systemic circulation, PMNs transmigrate into the tissue via homophilic interactions with PECAM-1 and CD99 on the PMN and the endothelial cells lining the vessel walls. These interactions allow the PMNs to squeeze across endothelial cells lining vessel walls. To identify and quantify the presence of transmigrated PMNs in the airspace, mice were subjected to induction of pneumonia and subsequent bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) washing of the airspace contents twenty-four hours later. For all experiments involving the blocking of PECAM-1 and CD99, the FVB/n strain was used, as it is known to more closely represent human physiology and responds to PECAM-1 and CD99 blocking antibodies. The C57Bl/6 model has been previously shown in our lab to be resistant to blockade by PECAM-1 and CD99 blocking antibodies (19).

It has been shown previously that the recruitment of leukocytes to the tissue in the lungs is unique, as it is the only known vasculature bed where inflammatory stimulus affects the mechanism by which leukocytes undergo recruitment. Previous work showed that PMN display differential dependence on β2 during bacterial bronchopneumonia based on whether the inflammatory stimulus is a Gram-positive or Gram-negative bacterial strain. To interrogate requirement of PECAM-1 and CD99 for TEM in the pulmonary vasculature, mice were subjected to bacterial infection of the lungs via either S. pneumoniae (Gram-positive) or P. aeruginosa (Gram-negative) bacteria. Both are human pathogens known to cause nosocomial and community-acquired pneumonia in patient populations and contribute significantly to pneumonia disease burden. Animals were infected by instillation of one of the bacteria strains. Simultaneously, IgG isotype control, PECAM-1 (2H8), or CD99 (3F11) blocking antibodies were administered retro-orbitally. BALs were taken at 24 hours and quantified via flow cytometry for presence of PMNs. Data showed that both types of bacteria elicit PMN responses that were capable of being reduced by blocking either PECAM-1 or CD99 (Fig. 2A,B). This suggests that murine bacterial bronchopneumonia also recruits PMNs that utilize standard PECAM-1 and CD99 mediated PMN transmigration, and that this effect is consistent for both typical Gram+ and Gram- bacterial pathogens.

Figure 2. PECAM-1- and CD99- dependence of PMN recruitment after lung injury.

Inflammation was induced and BALs or tissue sections were taken 24 hours later. At the time of inflammatory stimulus, mice were simultaneously injected with a control antibody or a PECAM-1 or CD99 blocking antibody. Data represent three separate experiments with dots representing individual mice. Statistics performed with Mann Whitney test. A. PMN recruitment to lavage fluid after P. aeruginosa injury. B. PMN recruitment to lavage fluid after S. pneumoniae injury. C. PMN recruitment to lavage fluid after chemical injury. D. Confocal microscopy imaging of FVB/n LysM-eGFP mice with blocking antibodies given at time of inflammatory acid stimulus. Asterisks denote alveolar spaces, which contain many PMNs in the control lungs, but many fewer in anti-PECAM or anti-CD99 treated mice. In the mice treated with anti-PECAM-1 or anti-CD99, many PMN appear to be arrested within the alveolar capillaries (arrows). Scale bars = 25 μm.

PMN transmigration in chemical injury is PECAM-1 and CD99-dependent

To investigate whether the requirement for PECAM-1 and CD99 extended to other models of pulmonary inflammation, we utilized a chemical injury model where mice were subjected to induction of chemical pneumonia via oropharyngeal instillation of 0.1N hydrochloric acid (HCl). Mice were treated at the time of instillation with either IgG isotype control, 2H8 (PECAM-1 blocking antibody), or 3F11 (CD99 blocking antibody). Utilizing blocking antibodies for either PECAM-1 or CD99 abrogated influx of PMNs into the airspace during chemical lung injury as shown by quantitation via flow cytometry (Fig 2C). These data suggest that the mechanism of transmigration of PMNs in the lung vasculature during chemical injury also recapitulates that of the systemic vasculature, requiring both PECAM-1 and CD99 during diapedesis into the tissue. The blockade could be visualized via confocal microscopy of LysM-GFP FVB/n mice with a tetramethylrhodamine dextran volume label, where PMNs remained trapped in vessels after treatment with either 2H8 or 3F11 (Fig. 2D).

Transmigration blocks do not result in intravascular retention at 24 h post-instillation

Histologic sections of lungs from mice whose PMN were prevented from extravasation by mAb blocking PECAM or CD99 (Fig. 3A-I) showed areas where PMNs still present in the tissue at 24 h remained mostly within the lung capillaries. In contrast, PMNs were present in the airspace in non-blocked conditions, consistent with the BAL measurements. These static images did not provide information about whether the PMN seen within the vasculature were totally static or whether they were temporarily arrested due to the block of TEM and would shortly re-enter the circulation, as occurs when they are blocked in the cremaster muscle (19). In that case, the static image would mask a continuous dynamic process. Furthermore, objective quantification of the degree of extravasation from these slides is difficult.

Figure 3. Histological imaging of three models of lung injury with and without blocking antibodies.

H&E stained paraffin embedded section of A. chemical injured tissue with non-blocking antibodies administered. B. acid injured tissue with PECAM-blocking antibodies administered. C. acid injured tissue with CD99-blocking antibodies administered. D. P. aeruginosa injured tissue with non- blocking antibodies administered. E. P. aeruginosa injured tissue with PECAM-blocking antibodies administered. F. P. aeruginosa injured tissue with CD99-blocking antibodies administered. G. S. pneumoniae injured tissue with non-blocking antibodies administered. H. S. pneumoniae injured tissue with PECAM-blocking antibodies administered. I. S. pneumoniae injured tissue with CD99-blocking antibodies administered. In untreated, anti-PECAM or anti-CD99 treated acid-instilled lungs, PMN are seen in alveolar capillaries, but reduced numbers are in the alveoli themselves in the anti-PECAM and anti-CD99 conditions. J. Untreated, PBS-instilled control tissue. Blue arrows show fibrin and leukocytes in alveoli; yellow arrows show clear alveoli. Scale bars = 50 μm.

To further analyze the presence of PMNs in the vasculature, we implemented a flow cytometry strategy to label intravascular, interstitial, and airspace PMNs in murine lung samples. Mice were subjected to chemical injury with or without simultaneous antibody blockade. 24 h post-instillation, mice were given a antemortem retro-orbital injection of APC anti-Ly6G to label PMN in the vasculature at the time of sacrifice, as has been detailed previously (27). After 3 minutes, mice were sacrificed, and BALs and left lung tissue were harvested. All samples were labeled for CD45 (PerCP Cy5.5), CD11b (FITC), and a postmortem Ly6G marker (PE). Intravascular PMNs were defined as CD45+ CD11b+ Ly6G PEpostmortem+ Ly6G APCantemortem+ in the tissue samples, interstitial PMNs were defined as CD45+ CD11b+ Ly6G PEpostmortem+ Ly6G APCantimortem- in the tissue samples, and airspace PMNs were defined as CD45+ CD11b+ Ly6G PEpostmortem+ Ly6G APCantimortem- in the BAL samples (Fig. 4A). The near complete lack of APC+ PMNs in the BAL samples confirmed that the antimortem label did not leak out of the vessels. We additionally verified the efficiency of Ly6G APCantimortem labeling via cardiac puncture finding 85.4% (+/− 0.08 STD) of Ly6G PEpostmortem blood-circulating cells to be APC positive. At 24 h post-acid instillation, we found that there were no significant differences in the presence of intravascular or interstitial PMNs between the blocked or untreated conditions (Fig. 4B). There was a significant increase in the airspace PMNs present in the untreated condition when compared to the PBS instillation control or PECAM-1/CD99 blocked conditions (Fig. 4C). These data demonstrate that while the number of PMNs that reach the pulmonary airspace is drastically reduced by transmigration blockade, the PMNs do not remain adherent in the vasculature or stagnated in the interstitium.

Figure 4. Presence of PMNs in the vasculature, interstitium, and airspace post-blockade.

Mice were subjected to chemical injury and given an antemortem injection of APC anti-Ly6G retro-orbitally to label circulating PMNs. BALs and left lung tissue were harvested sequentially from each mouse 24 h post-instillation. Data represent two separate experiments with dots representing individual mice. Single cell suspensions were made from the lung tissue and subjected to cytometry. Significance determined by non-parametric ANOVA (Kruskal-Wallis test). A. Flow cytometry gating strategy for the analysis of intravascular, interstitial, and airspace PMNs with representative plots. Numbers in the dot plot refer to the percentage of total cells in that quadrant. B. Using counting beads in the flow cytometry analysis, the number of intravascular and interstitial PMNs present with or without antibody blockade after chemical injury were quantified from murine left lung lobe tissue. C. Quantification of airspace PMNs present with or without antibody blockade after chemical injury quantified from BAL.

IVM imaging of lung ischemia/reperfusion injury shows PECAM-1- and CD99- dependent transmigration

While BALs, tissue digestion analysis by flow cytometry, and static timepoint microscopy are effective ways to quantitate blockade efficiency, the inflammatory cascade is a highly dynamic, active process. Thus, we aimed to complement this cytometric and imaging data by directly visualizing transmigration in the lungs.

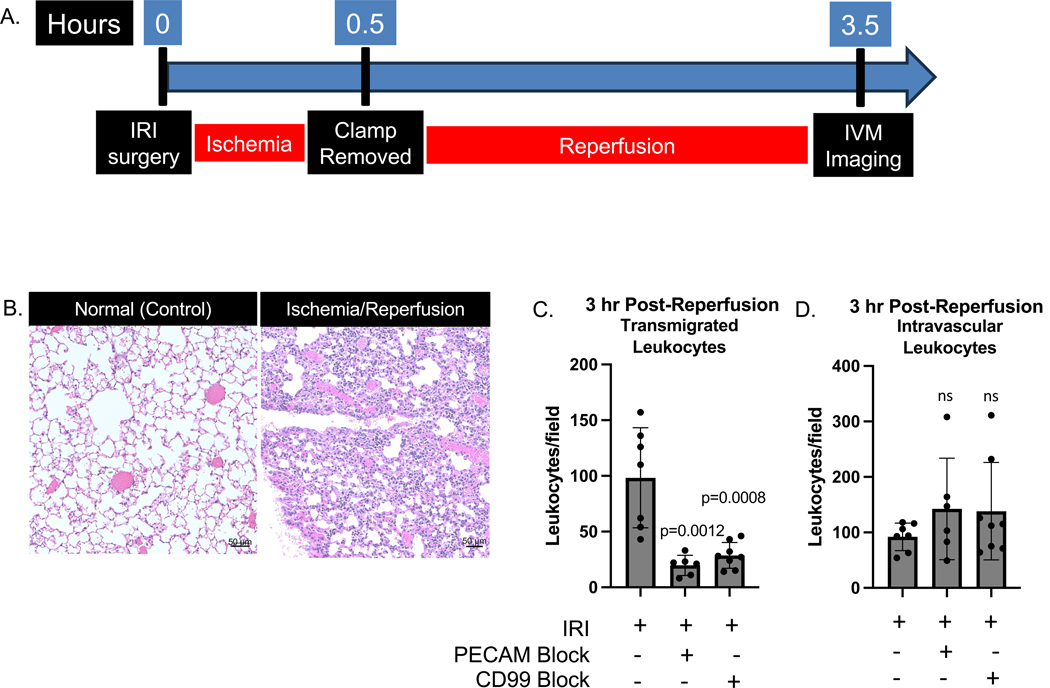

Previous work in our lab and others have used intravital microscopy (IVM) in live animals to visualize the process of the inflammatory cascade as it occurs (21). While the chemical injury induces robust inflammation (seen in our BAL data), the acute inflammatory response is primarily limited to the areas surrounding the bronchi of the lung deep within the lobes. Meanwhile, multiphoton microscopy of the live lung only resolves leukocytes and vasculature 1–2 mm into the tissue. Given these limitations, to utilize the most robust possible intravital imaging of the murine lung, we established an inflammatory model of the lungs that induced distal inflammation in the subpleural space. We utilized a hilar clamp placed to induce ischemia for 30 minutes, followed by reperfusion and intravital imaging (Fig. 5A). This ischemia reperfusion injury (IRI) model mimics warm ischemia in lung transplants. In FVB/n LysM-eGFP mice it induces subpleural recruitment of PMNs (Fig. 5B). In injured mice treated with control IgG, many PMN were seen in the subpleural alveoli in response to injury. Treatment with anti-PECAM or anti-CD99 mAb blocked appearance of PMNs in the alveoli (Fig. 5C). There were no differences in the absolute counts of intravascular PMNs in blocked and untreated mice at 3 hours post reperfusion (Fig. 5D). At 3 h post-reperfusion, many PMNs were seen in vessels, but few were seen actively transmigrating. Thus, we imaged earlier, at 1-hour post-reperfusion, to analyze transmigrating leukocytes. Transmigrating leukocytes were defined in videos by leukocytes that were clearly inside the vessels, squeezed out of the vasculature, and either spread out and became adherent to the lining of the airspace (Motion A) or were rocked by the motion of breathing in the airspace (Motion B) (Fig. 6A,B, Supplemental Videos 1–5). The number of transmigrating leukocytes was significantly higher in non-blocked conditions, although some leukocytes were able to overcome blocks in the PECAM-1- and CD99- blocked conditions (as reflected by previous flow cytometry data showing that these blocks are not complete) (Fig. 6C). For transmigrating cells, the vessel width was measured, and transmigrating leukocytes were seen primarily in the smaller alveolar capillaries (Fig. 6D), demonstrating in real time what had been surmised from previous light and electron microscope studies (9, 10). This direct visualization or transmigration in the pulmonary capillaries complements our indirect methods showing PECAM-1 and CD99 are required for efficient transmigration.

Figure 5. Leukocyte recruitment during warm ischemia-reperfusion injury.

Mice were subjected to warm ischemia-reperfusion injury, with 30 minutes of ischemia followed by 3 hours of reperfusion. Each dot represents a 30-minute video from an individual mouse with two mice imaged per experimental day. Fields were imaged at the same magnification across mice and conditions. A. Timeline of the surgery and imaging. B. Histological sections stained with H&E demonstrating IR injured sections with PMN recruitment at the periphery. C. Number of leukocytes present in the airspace of videos taken 3 h post-reperfusion. Statistical significance determined by Mann-Whitney test. D. Number of leukocytes present in the vasculature of videos taken 3 h post-reperfusion.

Live animal imaging reveals stagnation of PMNs in vessels during blockade

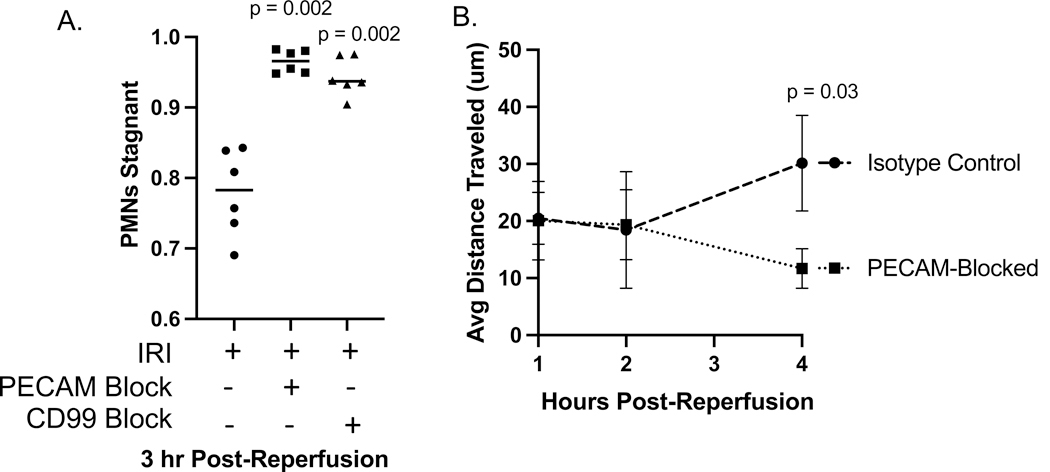

We additionally analyzed IVM videos of IRI for changes in leukocyte dynamics and transit time in the lungs, as previous work by our lab and others has shown differences in leukocyte stagnation after blockade. Treatment with anti-PECAM-1 or anti-CD99 mAb not only blocked appearance of PMN in the alveoli but also resulted in a relatively slow movement of PMN through the vasculature, reminiscent of what we see in the systemic circulation as adherent PMN crawl along the vessel attempting to transmigrate (19). Imaging in this model 3–4 h post-reperfusion revealed that movement of leukocytes in the subpleural capillaries was significantly reduced by blockade with either PECAM-1- or CD99- blocking antibodies. Representative videos show the reduced movement of leukocytes during blockade as well as their conformation to the shape of the capillary plexus containing them (Fig. 7A-C, Supplemental videos 6–8). Stagnation, defined by lack of translational movement during a 15-minute imaging time-period, was significantly increased in the antibody blocked conditions 3–4 h post-reperfusion (Fig. 8A). 0–2 h post-reperfusion, leukocyte transit distance was not affected by blockade; however, after most leukocytes have undergone transmigration at 3–4 hours post-reperfusion, average leukocyte transit distance is significantly reduced in the PECAM blocked condition (Fig. 8B). These data taken together directly demonstrate that transmigration is PECAM-1 and CD99 dependent in the pulmonary vasculature and that blockade of transmigration acutely, but not permanently (Fig. 4), alter leukocyte dynamics.

Figure 7. Intravital microscopy of ischemia-reperfusion injury.

Mice were subjected to warm IR injury and imaged via live animal imaging on a Nikon multiphoton microscope. Mice were LysM-GFP FVB/n with PMNs/monocytes/macrophages (green) and a non-blocking PECAM-1 endothelial junction label (red). Scale bars represent 50um. Each video was taken for 15 minutes with a z-stack taken every 25 seconds. Arrows are used to show GFP+ cells moving over time. A. Representative images from video of leukocyte recruitment post-IR injury. B. Representative images from video of leukocyte recruitment post-IR injury with simultaneous injection of PECAM-1 blocking antibody. C. Representative images from video of leukocyte recruitment post-IR injury with simultaneous injection of CD99 blocking antibody. Asterisks denote alveolar spaces with multiple neutrophils in A, but far fewer in anti-PECAM or anti-CD99-treated mouse lungs. Also see Supplemental Videos 6–8.

Figure 8. Quantification of leukocyte behavior after IRI via IVM.

Videos were taken of the subpleural vasculature of the left lobe of the lung 3 hours after resumption of perfusion post-ischemic clamp. Each video represents 15 minutes elapsed time with LysM-eGFP+ PMNs and monocytes/macrophages (green) and PECAM-1 endothelial junctions (red). See supplemental videos 6 – 8. A. Percent of LysM-eGFP+ cells that are stagnant during the 15 minutes of imaging. Each point represents a 15-min video taken from an individual mouse. B. Average distance traveled by leukocytes imaged. 15-minute videos were coded as taking place in hour 1 (0–60 minutes), hour 2 (61–120 minutes), hour 3 (121–180 minutes), or hour 4 (181–240 minutes) post-reperfusion. Transit distance was measured using Nikon NIS Elements software (see methods) and the average distance of all leukocytes from each video was taken. Each condition includes video from at least 2 mice, and the figure represents 12 experimental days. ANOVA statistical test performed.

Blocking transmigration of PMNs via PECAM-1 or CD99 does not affect mortality following pneumonia

Knowing that PMN transmigration blocks are effective at targeting airspace PMN recruitment in the lungs, as shown by direct and indirect methods, we aimed to study their potential therapeutic effects. PMNs are the first responders of the innate immune system, rapidly trafficking to sites of inflammation and migrating into the tissue to perform their effector functions. While they are essential to immune function, they can also cause tissue damage and unwanted pro-inflammatory effects during disease. A better, more fine-tuned PMN response could be therapeutic, particularly in the sensitive tissue of the lung airspace. Because blockade of PECAM-1 and CD99 was successful in reducing the influx of PMNs to the tissue during chemical injury and bacterial pneumonia, PMN blockades at the step of transmigration potentially offer value as treatment for PMN-mediated inflammatory diseases. As we and others have shown, transmigration blocks are not 100% effective; however, this is potentially beneficial, as total blockade could lead to general immunodeficiency.

Animals with chemical and bacterial pneumonia were subjected to blockade or IgG isotype control injection and their survival and outcomes were tracked. We intentionally tested our two models in which only approximately half the mice survive without intervention to mimic clinically relevant severe pneumonias. Blocking either PECAM-1 or CD99 in chemical injury had no effect on survival rate, neither worsening nor improving it (Fig. 9A,B). These data suggest that transmigration blockades are not therapeutically relevant for the treatment of this model of chemical lung injury. In P. aeruginosa pneumonia, blocking transmigration via either PECAM-1 or CD99 also had no effect on survival rate, either positive or negative (Fig. 9C,D). We did not perform this experiment in the S. pneumoniae induced pneumonia, because the infection is mild in FVB/n wild-type mice, and no mice died by seven days post-instillation in any blocked/non-blocked condition. These findings are particularly surprising given that PMNs are known to be necessary for resolving bacterial infection in numerous organ systems, including the lungs. Because transmigration blockade by PECAM-1 and CD99 is not 100% effective, there is still migration of a population of PMNs into the airspace during infection. This could provide enough cells to combat infection while not affecting the outcome of disease.

DISCUSSION

In these studies, we have shown that the transmigration of PMNs across the lung vasculature during chemical lung injury, Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacterial bronchopneumonia, and lung ischemia/reperfusion injury requires canonical inflammatory cascade proteins PECAM-1 and CD99. These proteins are essential for the efficient transmigration of PMNs to the airspace, and blocking their function drastically reduces the presence of PMNs in the lung airspace during pathology.

PMN rolling, one of the steps of the inflammatory cascade prior to transmigration, depends on selectins in the systemic circulation, whereas extravasation in the lungs is selectin independent (28). Similarly, previous work has identified a stimulus-dependent role for the β2 integrins that are canonically considered to be necessary molecules for the process of adhesion, another step prior to transmigration in the inflammatory cascade. In those studies, response to Gram-negative E. coli required β2 integrins, whereas response to Gram-positive S. pneumoniae was β2 integrin independent (26). The same integrin-independence of TEM in the lung was seen in human cases of Leukocyte Adhesion Deficiency Type I (29). Despite these differences of leukocyte rolling and adhesion in the lung, we have demonstrated that the subsequent step of leukocyte transmigration is regulated by PECAM-1 and CD99, as in the systemic circulation.

Given that PMNs are known to be damaging to the tissue and that blocking transmigration has been proposed previously as a potential treatment for inflammatory diseases, this novel finding was investigated in its capacity to treat murine pneumonia (30, 31, 32, 33). The blocking of PMNs’ ability to transmigrate by either PECAM-1 or CD99 had no effect on survival in two models (chemical injury and P. aeruginosa pneumonia) in which ~ 50% of the mice progressed to death. These conditions were chosen to represent translationally relevant conditions. We could have given a weaker stimulus in which fewer mice died. Under those conditions, it is possible that blocking PMN entry could have made a significant difference in survival. However, our model was chosen for its ability to test the blocking of PMNs under conditions where mice become acutely ill to remain translationally relevant. Work in our lab has shown that blocking transmigration of PMNs during ischemic stroke and arthritis has therapeutic effects (33, 34). These differences may be model- or vascular bed dependent and should be explored further in future studies. It should be noted that antibody blockade with anti-PECAM and anti-CD99 is never complete, and it is possible that the small percentage of leukocytes that did transmigrate were sufficient to successfully respond to the insult. Neutrophils are known to secrete lipid compounds that promote resolution of inflammation in the lungs (35). A non-mutually exclusive possibility is that the intravascular PMNs retained in the alveolar capillaries by blocking PECAM or CD99 are still capable of secreting these and promoting repair of the damaged lung.

In these studies, we also implemented methods for the live imaging of transmigration of leukocytes across the alveolar capillaries. To our knowledge, this represents the first direct visualization of leukocyte transmigration in the lungs. We showed that PECAM-1 and CD99 are required for efficient transmigration of leukocytes in response to ischemia/reperfusion injury. Intravital microscopy has the added benefit (compared to flow cytometric analysis of BALs) of measuring the vessel size to understand the location of transmigration. We found that leukocytes transmigrate through the alveolar capillaries, as has been shown previously by analysis of static images (9, 10). Blockades of PECAM-1 and CD99 caused leukocytes to have reduced transit times through the imaging fields of view.

While these studies identified canonical transmigration proteins PECAM-1 and CD99 as essential regulators in the lung vasculature during inflammation, there is ample work from our lab and others that these are not the only regulators of transmigration. Our lab has previously demonstrated VEGFR2 is required for TEM in the lungs presumably as part of the PECAM/VE-cadherin/VEGFR2 mechanotransduction complex (36), but there are several proteins that are less well-known but could be different in their use in the lung vasculature. For example, calcium signaling is known to be highly important in the transmigration of PMNs in the systemic vasculature (37). It is not known whether other regulators of transmigration, such as the lateral border recycling complex (LBRC), are critical for transendothelial migration in the lungs as they appear to be in the systemic vasculature (14, 38). Future work will need to address the requirement for these pathways in the lung during various models of lung inflammation. It is vital that we fully understand leukocyte dynamics in acute lung injury, as the disease burden is high and associated with inflammatory cell infiltration.

Acute lung injury is a highly severe disorder. This is, in part, due to the inflammatory cell recruitment and subsequent alveolar edema, deposition of protein, lipid, and cellular debris, and tissue damage, which results in compromised gas exchange and inability to properly oxygenate the body. The latter is an effect not seen in the inflammation of any other tissue in the body. In our work, we specifically chose to utilize a model that recapitulated this acute clinical presentation of ALI. Three of our inflammatory models were tuned to result in a survival rate of approximately 50% over seven days. This aspect of our models allows our work presented here to be highly therapeutically relevant, as the most pressing need in the space of ALI is acute therapeutics that affect positive change during the time when the most mortality is seen.

In summary, these data show the requirement for PECAM-1 and CD99 in four models of both sterile and non-sterile inflammation of the lungs. These findings contribute to our understanding of the inflammatory cascade in the immunologically unique vasculature of the lungs.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Videos S1–S8: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28836251.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Robert Golenia at the Northwestern University (NU) Professional Machine Shop for assistance with manufacturing a microscope stage for IVM. We thank Felix Nunez (Pulmonary and Critical Care) for training in intravital imaging of the lung. Imaging work was performed at the Northwestern University Center for Advanced Microscopy (CAM) (RRID: SCR_020996) generously supported by CCSG P30 CA060553 awarded to the Robert H Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center. Multiphoton microscopy was performed on a Nikon A1R multiphoton microscope, acquired through the support of NIH 1S10OD010398–01. We thank Drs. Constadina Arvinitis, David Kirchenbuechler, and Mariana de Niz at NU CAM for assistance with multiphoton microscopy and analysis. We thank Dr. Wilson Liu at NU CAM for assistance with histology microscopy and analysis. Non-clinical research histopathology and molecular phenotyping services were provided by the Northwestern University Mouse Histology and Phenotyping Laboratory (MHPL) which is supported by NCI P30-CA060553 awarded to the Robert H Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center. We thank Dr. Alan Hauser (NU) for the gift of the strain of the P. aeruginosa used to complete this work. We acknowledge the contributions of Lily Miller (NU) and Zoie Lipfert (NU) in supporting this work. We thank Drs. Cara Gottardi (NU), GR Scott Budinger (NU), Peter Sporn (NU), and Marie-Pierre Tetrault for guidance on the direction of this work. DPS is supported by NIH R21AG086751. For this work, MEH is funded by NIH F31HL172345, and WAM is funded by NIH R35HL155652.

GRANTS

NIH, NHLBI, Award Number: F31HL172345 (to MEH);

NIH, NINDS, Award Number: F31NS130939 (to EA);

NIH, NIA, Award Number: R21AG086751 (to DPS);

NIH, NHLBI, Award Number: R35HL155652 (to WAM)

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

We declare no conflicts of interest.

DATA AVAILABILITY

Data will be publicly available and provided upon request. Source data found at https://figshare.com/s/2aaf167a6e3e9d65fdd0.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gupte T, Knack A, Cramer JD. Mortality from Aspiration Pneumonia: Incidence, Trends, and Risk Factors. Dysphagia. 2022;37(6):1493–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Regunath H, Oba Y. Community-Acquired Pneumonia. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL)2025. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hunt EB, Sullivan A, Galvin J, MacSharry J, Murphy DM. Gastric Aspiration and Its Role in Airway Inflammation. Open Respir Med J. 2018;12:83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reynolds JH, McDonald G, Alton H, Gordon SB. Pneumonia in the immunocompetent patient. Br J Radiol. 2010;83(996):998–1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kumar V Pulmonary Innate Immune Response Determines the Outcome of Inflammation During Pneumonia and Sepsis-Associated Acute Lung Injury. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ley K, Laudanna C, Cybulsky MI, Nourshargh S. Getting to the site of inflammation: the leukocyte adhesion cascade updated. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7(9):678–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mizgerd JP. Molecular mechanisms of neutrophil recruitment elicited by bacteria in the lungs. Semin Immunol. 2002;14(2):123–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muller WA. Mechanisms of transendothelial migration of leukocytes. Circ Res. 2009;105(3):223–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Downey GP, Worthen GS, Henson PM, Hyde DM. Neutrophil sequestration and migration in localized pulmonary inflammation. Capillary localization and migration across the interalveolar septum. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;147(1):168–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Loosli CG, Baker RF. Acute Experimental Pneumococcal (Type I) Pneumonia in the Mouse: The Migration of Leucocytes from the Pulmonary Capillaries into the Alveolar Spaces as Revealed by the Electron Microscope. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 1962;74:15–28. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carlos TM, Harlan JM. Leukocyte-endothelial adhesion molecules. Blood. 1994;84(7):2068–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lou O, Alcaide P, Luscinskas FW, Muller WA. CD99 is a key mediator of the transendothelial migration of neutrophils. J Immunol. 2007;178(2):1136–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muller WA, Weigl SA, Deng X, Phillips DM. PECAM-1 is required for transendothelial migration of leukocytes. J Exp Med. 1993;178(2):449–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sullivan DP, Muller WA. Neutrophil and monocyte recruitment by PECAM, CD99, and other molecules via the LBRC. Semin Immunopathol. 2014;36(2):193–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller M, Sung KL, Muller WA, Cho JY, Roman M, Castaneda D, et al. Eosinophil tissue recruitment to sites of allergic inflammation in the lung is platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule independent. J Immunol. 2001;167(4):2292–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vaporciyan AA, DeLisser HM, Yan HC, Mendiguren II, Thom SR, Jones ML, et al. Involvement of platelet-endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 in neutrophil recruitment in vivo. Science. 1993;262(5139):1580–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tasaka S, Qin L, Saijo A, Albelda SM, DeLisser HM, Doerschuk CM. Platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 in neutrophil emigration during acute bacterial pneumonia in mice and rats. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167(2):164–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seidman MA, Chew TW, Schenkel AR, Muller WA. PECAM-independent thioglycollate peritonitis is associated with a locus on murine chromosome 2. PLoS One. 2009;4(1):e4316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sullivan DP, Watson RL, Muller WA. 4D intravital microscopy uncovers critical strain differences for the roles of PECAM and CD99 in leukocyte diapedesis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2016;311(3):H621–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aulakh GK. Neutrophils in the lung: “the first responders”. Cell Tissue Res. 2018;371(3):577–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Worthen GS, Schwab B, 3rd, Elson EL, Downey GP. Mechanics of stimulated neutrophils: cell stiffening induces retention in capillaries. Science. 1989;245(4914):183–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Faust N, Varas F, Kelly LM, Heck S, Graf T. Insertion of enhanced green fluorescent protein into the lysozyme gene creates mice with green fluorescent granulocytes and macrophages. Blood. 2000;96(2):719–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nielsen TB, Yan J, Luna B, Spellberg B. Murine Oropharyngeal Aspiration Model of Ventilator-associated and Hospital-acquired Bacterial Pneumonia. J Vis Exp. 2018(136). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmidt-Nielsen K Scaling, why is animal size so important? Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press; 1984. xi, 241 p. p. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mutlu GM, Green D, Bellmeyer A, Baker CM, Burgess Z, Rajamannan N, et al. Ambient particulate matter accelerates coagulation via an IL-6-dependent pathway. J Clin Invest. 2007;117(10):2952–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Doerschuk CM, Winn RK, Coxson HO, Harlan JM. CD18-dependent and -independent mechanisms of neutrophil emigration in the pulmonary and systemic microcirculation of rabbits. J Immunol. 1990;144(6):2327–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chow YH, Murphy RC, An D, Lai Y, Altemeier WA, Manicone AM, et al. Intravascular Leukocyte Labeling Refines the Distribution of Myeloid Cells in the Lung in Models of Allergen-induced Airway Inflammation. Immunohorizons. 2023;7(12):853–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Doerschuk CM, Quinlan WM, Doyle NA, Bullard DC, Vestweber D, Jones ML, et al. The role of P-selectin and ICAM-1 in acute lung injury as determined using blocking antibodies and mutant mice. J Immunol. 1996;157(10):4609–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Etzioni A, Doerschuk CM, Harlan JM. Of man and mouse: leukocyte and endothelial adhesion molecule deficiencies. Blood. 1999;94(10):3281–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arias E, Nadkarni N, Fang R, Haynes M, Batra A, Muller W, et al. Inhibition of PECAM-1 Significantly Delays Leukocyte Extravasation into the Subcortex Post-Stroke. FASEB J. 2022;36 Suppl 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bixel MG, Li H, Petri B, Khandoga AG, Khandoga A, Zarbock A, et al. CD99 and CD99L2 act at the same site as, but independently of, PECAM-1 during leukocyte diapedesis. Blood. 2010;116(7):1172–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bogen S, Pak J, Garifallou M, Deng X, Muller WA. Monoclonal antibody to murine PECAM-1 (CD31) blocks acute inflammation in vivo. J Exp Med. 1994;179(3):1059–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nadkarni NA, Arias E, Fang R, Haynes ME, Zhang HF, Muller WA, et al. Platelet Endothelial Cell Adhesion Molecule (PECAM/CD31) Blockade Modulates Neutrophil Recruitment Patterns and Reduces Infarct Size in Experimental Ischemic Stroke. Am J Pathol. 2022;192(11):1619–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dasgupta B, Chew T, deRoche A, Muller WA. Blocking platelet/endothelial cell adhesion molecule 1 (PECAM) inhibits disease progression and prevents joint erosion in established collagen antibody-induced arthritis. Exp Mol Pathol. 2010;88(1):210–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Serhan CN, Levy BD. Proresolving Lipid Mediators in the Respiratory System. Annu Rev Physiol. 2025;87(1):491–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fu T, Sullivan DP, Gonzalez AM, Haynes ME, Dalal PJ, Rutledge NS, et al. Mechanotransduction via endothelial adhesion molecule CD31 initiates transmigration and reveals a role for VEGFR2 in diapedesis. Immunity. 2023;56(10):2311–24 e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dalal PJ, Sullivan DP, Weber EW, Sacks DB, Gunzer M, Grumbach IM, et al. Spatiotemporal restriction of endothelial cell calcium signaling is required during leukocyte transmigration. J Exp Med. 2021;218(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sullivan DP, Dalal PJ, Jaulin F, Sacks DB, Kreitzer G, Muller WA. Endothelial IQGAP1 regulates leukocyte transmigration by directing the LBRC to the site of diapedesis. J Exp Med. 2019;216(11):2582–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be publicly available and provided upon request. Source data found at https://figshare.com/s/2aaf167a6e3e9d65fdd0.