Abstract

Background

Lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) is the most common subtype of non-small cell lung cancer. Although immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have brought new treatment options for advanced patients, a considerable proportion still shows limited response. Mitochondrial dysfunction plays a crucial role in tumor development and immune evasion, but its regulatory mechanisms in LUAD immune microenvironment remain unclear.

Methods

We integrated 149 mitochondria-related pathways (1,136 coding proteins) to develop and validate the Mitochondrial Pathway Signature (MitoPS) using machine learning approaches across seven independent LUAD cohorts (n=1,231). The system was systematically compared with 129 published LUAD prognostic signatures and validated in seven immunotherapy cohorts (n=451). Multiomics analysis, immunofluorescence staining, and experimental validation were performed to investigate its molecular mechanism.

Results

MitoPS demonstrated consistent predictive performance across validation cohorts, with high scores indicating poor prognosis, outperforming 129 existing prognostic models. In immunotherapy cohorts, MitoPS reliably predicted treatment response and prognosis. Immune microenvironment analysis revealed that low MitoPS scores correlated with higher immune cell infiltration and active immune function. Mechanistic studies identified mitochondria-related gene NDUFB10 as a core gene of MitoPS (r=0.38, p<0.05), where its high expression was significantly associated with immune desert phenotype and worse prognosis. Functional experiments confirmed that NDUFB10 knockdown significantly enhanced ICIs therapy and increased GZMB+CD8+T cell infiltration, indicating NDUFB10’s crucial role in regulating tumor immune microenvironment and immunotherapy response.

Conclusion

The MitoPS scoring system reliably predicts prognosis and immunotherapy response in patients with LUAD, providing a novel reference for clinical decision-making. Furthermore, its core gene NDUFB10 regulates tumor immune microenvironment, offering a potential therapeutic target for improving immunotherapy outcomes.

Keywords: Immunotherapy, Lung Cancer

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

Lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) is the most common non-small cell lung cancer subtype with limited response to immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) in many patients. Mitochondrial dysfunction is known to influence tumor development and immune evasion, but its specific regulatory mechanisms in the LUAD immune microenvironment and their clinical implications remain poorly understood.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

This study introduces the Mitochondrial Pathway Signature (MitoPS), a novel prognostic model that outperforms 129 existing signatures in predicting LUAD outcomes and immunotherapy response across multiple cohorts. Multiomics analysis identified NDUFB10 as a key mitochondria-related gene associated with immune desert phenotype and poor prognosis. Experimental validation confirmed that NDUFB10 knockdown enhanced ICIs therapy effectiveness and increased GZMB+CD8+T cell infiltration, establishing its critical role in regulating the tumor immune microenvironment.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

MitoPS offers clinicians a reliable tool for predicting prognosis and immunotherapy response in patients with LUAD, potentially improving treatment decision-making and patient selection for immunotherapy. The identification of NDUFB10 as a regulator of the tumor immune microenvironment provides a promising therapeutic target for enhancing immunotherapy efficacy. This work may drive the development of mitochondria-targeted therapies as complementary approaches to immunotherapy in LUAD treatment strategies.

Introduction

Lung cancer remains the leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide, with lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) accounting for approximately 50% of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cases.1,3 Although immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have revolutionized LUAD treatment, only 20–30% of patients achieve durable responses.4 The 5-year survival rate for advanced LUAD remains below 20%, highlighting the urgent need for more effective therapeutic strategies.5 Moreover, the increasing adoption of early screening programs has led to a higher proportion of early-stage diagnoses, emphasizing the importance of accurate treatment response prediction.5 6 Current predictive biomarkers for immunotherapy response, including programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression and tumor mutational burden (TMB), have shown limited accuracy in patient stratification.7 Despite extensive research, these markers fail to capture the complex interactions within the tumor microenvironment that critically influence treatment outcomes.8 For instance, studies have demonstrated significant intratumoral heterogeneity in PD-L1 expression, while TMB alone cannot reliably predict immunotherapy response across different patient cohorts.9 10 Therefore, developing novel predictive biomarkers and therapeutic targets has become a research priority.

Accumulating evidence suggests that mitochondrial function plays a crucial role in tumor progression and immune regulation.11 Alterations in mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation complexes are closely associated with immune cell function and tumor immune evasion.12 For example, downregulation of complex I component NDUFS1 leads to excessive ROS production in tumor cells, subsequently inducing CD8+T cell dysfunction.13 Meanwhile, aberrant expression of mitochondrial fusion proteins MFN1/2 affects antigen presentation by dendritic cells, thereby suppressing antitumor immune responses.14 Additionally, deficiency in mitochondrial stress response protein PINK1 disrupts mitophagy, promoting tumor-associated macrophage polarization toward the protumoral M2 phenotype.15 However, the systematic relationship between mitochondrial function and immune response in LUAD remains poorly understood.16 Notably, mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation complexes exhibit unique roles in tumor metabolism and immune regulation.17 For instance, expression levels of complex III component UQCRC2 closely correlate with the functional status of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes.18 Complex I dysfunction not only affects energy metabolism but may also influence immune cell recruitment and activation through modulation of cytokine secretion.19 These findings suggest that mitochondrial complexes may serve as critical nodes linking tumor metabolism and immune response.

Through systematic analysis of mitochondrial pathways in LUAD, we developed MitoPS, a Mitochondrial Pathway Signature for predicting prognosis and immunotherapy response. By integrating clinical data from 14 independent cohorts, we comprehensively validated the stability and reliability of MitoPS in predicting immunotherapy outcomes. In-depth analysis of MitoPS revealed NDUFB10, a complex I component, as a key gene within the scoring system, with its expression levels strongly correlating with immunotherapy response. Functional studies further elucidated the molecular mechanism by which NDUFB10 influences immunotherapy efficacy through regulation of the tumor immune microenvironment.

Method

Dataset source

We obtained LUAD gene expression data, somatic single nucleotide variant (SNV) data, and copy number variation (CNV) data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database, and normal lung tissue expression data from the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) database for differential analysis. Genomic alterations (recurrently amplified and deleted regions) were determined using the GISTIC V.2.0 analysis (https://software.broadinstitute.org) on the TCGA-derived CNV data. We integrated six independent LUAD cohorts from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database, including GSE13213 (dataset)20 (n=117), GSE26939 (dataset)21 (n=115), GSE29016 (dataset)22 (n=39), GSE30219 (dataset)23 (n=85), GSE31210 (dataset)24 (n=226), and GSE42127 (dataset)25 (n=133). Batch effects between these cohorts were corrected using the ComBat algorithm,26 followed by data normalization. To evaluate the model’s utility in immunotherapy, we collected data from seven immunotherapy-related NSCLC cohorts: POPLAR (dataset)27 (n=59), OAK (dataset)27 (n=257), NG (dataset)28 (n=46), GSE126044 (dataset)29 (n=16), GSE135222 (dataset)30 (n=27), GSE166449 (dataset)31 (n=22), and GSE207422 (dataset)32 (n=24), comprising a total of 451 patients. Somatic mutation and CNV data for patients with LUAD were obtained from the UCSC Xena data portal (https://xena.ucsc.edu/). The 149 mitochondria-related signaling pathways and 1,136 mitochondria-related coding proteins were summarized from the MitoCarta3.0 database33 (online supplemental table S1). To systematically evaluate mitochondrial pathway activities between LUAD and normal tissues, we employed Gene Set Variation Analysis methodology.33

Identification of mitochondria-related prognostic signature

Based on the MitoCarta3.0 database annotation, we systematically analyzed the expression patterns and mutation characteristics of 1,136 mitochondria-related coding genes across 149 signaling pathways. Differential expression analysis was performed using the limma package34 with thresholds of false discovery rate (FDR)<0.05 and |log2FC|>1. The mutation landscape of these genes was comprehensively analyzed using the maftools package. Oncoplot visualization was employed to display the most frequently mutated mitochondria-related genes, while mutation signature analysis revealed the predominant mutation patterns. Machine learning plays a crucial role in the construction of biomarkers.35 36 In order to build a robust MitoPS, we first conducted univariate Cox regression analysis to identify survival-associated genes. The optimization process incorporated a comprehensive evaluation of multiple algorithmic combinations through 10-fold cross-validation methodology.37 The computational approaches encompassed various statistical frameworks: stepwise Cox regression, Lasso penalization, Ridge regression, partial least squares regression adapted for Cox modeling (plsRcox), CoxBoost enhancement, random survival forest methodology, generalized boosted regression modeling, elastic net regularization, supervised principal components analysis, and survival-oriented support vector machine classification. This systematic evaluation aimed to establish the optimal MitoPS configuration, with concordance index (C-index) serving as the primary performance metric. The predictive accuracy of the developed MitoPS was validated through time-dependent receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis, Kaplan-Meier survival analysis, and principal component analysis (PCA) methodology. The comparative assessment phase incorporated established prognostic signatures from previous studies, with C-index serving as the comparative performance indicator.

Immune profiling analysis

The evaluation of immunotherapeutic responsiveness in LUAD cases was facilitated through immunophenoscore assessment via The Cancer Immunome Atlas platform (https://tcia.at/home).38 Tumor microenvironment characterization was accomplished through the single-sample gene set enrichment analysis (ssGSEA) computational approach, which quantified both immune cell infiltration patterns and immune pathway activation states within neoplastic specimens. Comprehensive immune infiltration profiles across TCGA samples were accessed through the TIMER2.0 platform,39 which synthesized outcomes from multiple computational methods.

Single-cell RNA sequencing data processing

Single-cell transcriptomic analysis integrated data from three public repositories: CRA001963 (National Genomics Data Center), GSE123904 (GEO database), and PRJNA591860 (NCBI Sequence Read Archive). The initial transcriptomic data underwent preprocessing via Seurat R package40 (V.4.2.0). The analytical inclusion criterion was established at a minimum expression threshold of 10 cells per gene within individual samples. Cell quality filtration was implemented based on predetermined parameters: cellular units were excluded if they expressed more than 5,000 or fewer than 200 genes, or if mitochondrial genome-derived unique molecular identifiers exceeded 10%. Sample integration was accomplished through the harmony R package implementation. The subsequent analytical pipeline incorporated highly variable gene selection for PCA, followed by dimensional reduction using the top 30 significant PCs through t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) methodology. Subpopulation-specific transcriptional profiles were delineated using the “FindAllMarkers” algorithmic function, with cellular phenotype classification based on established lineage-specific markers from prior investigations.

Cell–cell signaling networks

Intercellular communication patterns were decoded through CellChat analytical framework integration with expression profiles. The analysis used CellChat’s native ligand-receptor reference database,41 following standardized protocols. The methodology enabled identification of cell-type-specific interaction patterns through detection of preferentially expressed signaling molecules. Communication networks were mapped based on elevated expression patterns of either receptor components or their corresponding ligands within distinct cellular populations.

Patient cohort and sample collection

Clinical specimens included paraffin-embedded tissue sections from the Department of Pathology, Tianjin Medical University Cancer Institute and Hospital. All specimens were pathologically confirmed as LUAD, and only treatment-naive cases before surgical intervention were included. Comprehensive clinical and pathological parameters are shown in online supplemental table S2.

Immunohistochemistry analysis

Tissue processing began with deparaffinization in xylene, followed by rehydration through graded ethanol. After treatment with 3% hydrogen peroxide and blocking with 5% goat serum, sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibody against NDUFB10 (1:250, Cat# ab196019). Subsequent processing included application of horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-labeled secondary antibody (30 min incubation), 3,3'-diaminobenzidine (DAB) chromogen development, and hematoxylin counterstaining. Assessment was independently performed by two pathologists. NDUFB10 expression was semi-quantitatively evaluated using the Immunoreactivity Score, calculated as the product of the percentage score (0: no positive cells; 1: ≤10%; 2: 11–50%; 3: 51–80%; 4: >80%) and the staining intensity score (0: negative; 1: weak; 2: moderate; 3: strong), with total scores ranging from 0 to 12.

Multiplex immunohistochemistry analysis protocol

Spatial relationships between NDUFB10 and immune markers were evaluated using multiplex immunofluorescence staining. Tissue processing began with deparaffinization in xylene, followed by rehydration through graded ethanol. After antigen retrieval and blocking with 5% goat serum, sections were sequentially incubated with primary antibodies: NDUFB10 (1:100, Cat# ab196019), CD3D (1:2000, Cat# ab213362), and CD20 (1:100, Cat# ab64088), followed by corresponding fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies. Nuclear counterstaining was performed with 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). T-cell infiltration levels were semi-quantitatively assessed by evaluating the percentage of positive cells in the tumor stroma (0: no positive cells; 1: ≤10%; 2: 11–50%; 3: 51–80%; 4: >80%). Based on the spatial distribution patterns of T cells, tumors were classified into three phenotypes: inflamed (abundant T-cell infiltration within tumor nests), excluded (T cells mainly aggregated in tumor stroma or marginal areas with little or no infiltration into tumor nests), and deserted (few or absent T cells in tumor tissue).

Cell culture and RNA interference

LUAD cell lines (A549 and H1299) were obtained from the Institute of Biochemistry and Cell Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai). Cells were maintained in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and antibiotics (100 U/mL penicillin, 100 mg/mL streptomycin) at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. Mouse Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC) cells were cultured under the same conditions. Gene knockdown was achieved through lentiviral transduction, followed by puromycin selection (2 µg/mL) for 48 hours. Knockdown efficiency was validated by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analysis.

Cell proliferation assay

Cells were dissociated with 0.25% trypsin, and A549 and H1299 cells were seeded in 96-well plates (2×103 cells/well, five replicate wells per group) and divided into three groups: blank control (NC), vector control (vector), and NDUFB10 knockdown (sh-NDUFB10). After 24-hour adherence, designated as the 0-hour time point, cell viability was assessed at 0, 24, 48, 72, and 96 hours. At each time point, 10 µL of Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) reagent (Dojindo, Japan) was added to each well and incubated at 37°C for 2 hours in the dark. The optical density was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader. The experiment was independently repeated three times.

Murine subcutaneous tumor model

Female C57BL/6 mice (6–8 weeks, Jiangsu GemPharmatech) were randomly divided into groups (n=5 per group). LLC cells (control or NDUFB10 knockdown groups, 5×105 cells/mouse) were subcutaneously injected into the right flank. The therapeutic protocol comprised intraperitoneal injection of anti-programmed cell death 1 receptor (PD-1) antibody (200 µg/mouse) or isotype control on days 6, 9, 12, and 15 post-injection. Tumor volume was measured every 3 days and calculated using the formula: V=(length×width2)/2. Terminal analysis occurred on day 21, with humane euthanasia performed by cervical dislocation under isoflurane anesthesia. Tumor tissues were collected and either fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for histological analysis or processed for flow cytometric analysis. All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Flow cytometric analysis

Fresh tumor specimens were enzymatically dissociated in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with collagenase IV (Gibco 17104019) and DNase I (Roche 10104159001) at 37°C for 2 hours with gentle agitation. Single-cell suspensions were obtained by passing through 70 µm cell strainers (BD Falcon), followed by lymphocyte isolation using Percoll density gradient centrifugation (40%/70%, 800 g for 20 min at room temperature). The isolated cells were stimulated with leukocyte activation cocktail containing phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA)/ionomycin and protein transport inhibitor (BD Pharmingen 550583) at 37°C for 4 hours. For immunostaining, cells were first blocked with anti-mouse CD16/CD32 antibody (BD 553141) at 4°C for 15 min, then incubated with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies against surface markers: CD45 (BD 553080), CD3e (BD 553064), and CD8α (BD 551162) for 30 min at 4°C in the dark. Following surface staining, cells were fixed and permeabilized using Cytofix/Cytoperm solution (BD Biosciences 554714) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Subsequently, intracellular staining was performed with anti-GZMB (BioLegend 372204) antibody at 4°C for 30 min. Data acquisition was performed on a BD FACSCanto II flow cytometer, and data analysis was conducted using FlowJo software (V.10.0).

Statistical methods

Statistical analyses were performed using R V.4.2.0 software. For comparisons between two groups, unpaired Student’s t-test was applied for normally distributed data, while Mann-Whitney U test was used for non-normally distributed data. For multiple group comparisons, one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s post hoc test was employed for normally distributed data, while Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s post hoc test was used for non-normally distributed data. Correlation analysis was performed using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. Data are presented as mean±SD. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05 (*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001).

Result

Molecular characteristics and clinical significance of mitochondria-related signaling pathway

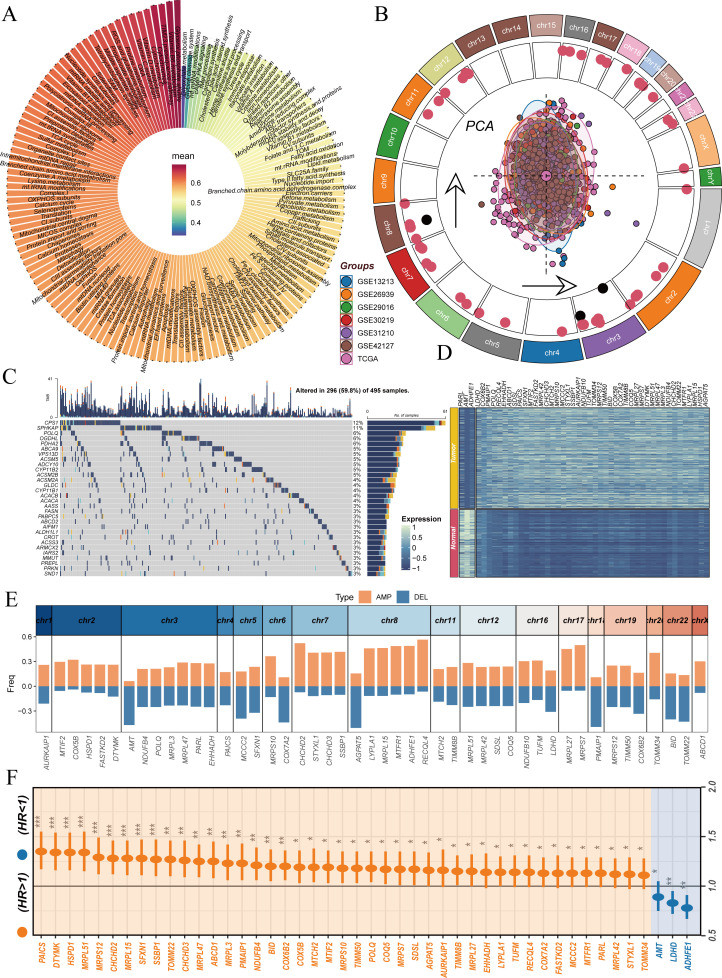

LUAD is the most common subtype of NSCLC.42 Although ICIs have brought new hope for advanced patients, a considerable proportion of patients still do not benefit from this treatment, and the prognosis of advanced patients remains poor.43 Recent studies have shown that mitochondrial dysfunction plays a crucial role in tumor development and immune evasion,44 but its specific regulatory mechanisms in the immune microenvironment of LUAD remain unclear. Therefore, we developed a MitoPS scoring system to explore the relationship between mitochondrial function and the tumor immune microenvironment, aiming to provide new strategies for improving immunotherapy efficacy (figure 1). To systematically explore the role of mitochondria-related signaling pathways in LUAD, we conducted a comprehensive analysis across multiple datasets. Initially, using TCGA and GTEx databases, we analyzed the ssGSEA activity differences of 149 mitochondria-related signaling pathways between LUAD and normal samples. Results revealed significant activation of most mitochondrial pathways in tumor samples (figure 2A). This observation suggests that mitochondria-related pathways may play crucial roles in LUAD development. Building on these findings, we integrated data from seven independent LUAD cohorts for more in-depth analysis. PCA after batch effect correction demonstrated consistent sample distribution across different cohorts(figure 2B). To investigate the genomic characteristics of mitochondria-related genes, we first mapped the chromosomal locations of differentially expressed and prognostically significant genes among 1,136 mitochondria-related coding proteins, with red and black indicating genes highly expressed in tumor and normal tissues, respectively (figure 2B). To further characterize the mutation features of mitochondria-related proteins, we performed a systematic analysis of their mutation spectrum (online supplemental figure 1). Results showed that missense mutations were the predominant variant type, followed by nonsense mutations and splice site mutations, while frameshift deletions, frameshift insertions, and other types were relatively rare (online supplemental figure 1A, E). Among variant types, single nucleotide polymorphisms were dominant, with insertions and deletions (DEL) occurring at lower frequencies (online supplemental figure 1B). SNV analysis revealed that C>A and C>T transitions were the most common variant types (online supplemental figure 1C). Analysis of mutation burden showed a median of 5 variants per sample (online supplemental figure 1D). We further analyzed the top 30 most frequently mutated genes among mitochondria-related proteins, among which CPS1 (12%) and SPHKAP (11%) showed the highest mutation frequencies (online supplemental figure 1F, figure 2C). Differential expression analysis identified numerous mitochondria-related genes showing significant expression differences between tumor and normal tissues (figure 2). Furthermore, we analyzed the CNV characteristics of these genes. Results showed significant amplifications and DEL in multiple chromosomal regions, which may significantly affect the function of mitochondria-related signaling pathways (figure 2E). Finally, through univariate Cox regression analysis, we further screened prognosis-related mitochondrial genes, revealing that high expression of certain genes (such as PAICS and MRPL51) indicated poor prognosis, while others (such as ADHFE1) showed protective effects (figure 2F). These findings emphasize the crucial role of mitochondria-related signaling pathways in LUAD development and progression, providing new insights for targeted therapy.

Figure 1. Construction and validation process of the MitoPS scoring system. We first integrated information from 149 mitochondria-related pathways and their 1,136 encoded proteins. During the model development phase, we integrated data from 1,682 samples across 14 independent cohorts to construct the MitoPS scoring system. In the model evaluation phase, we validated the reliability of this scoring system from three aspects: (1) performance comparison with established signatures; (2) evaluation of its value as a marker for immune cell infiltration; (3) screening and identification of critical genes. The specific workflow includes: (1) cohort integration: integration of 1,682 samples from 14 independent cohorts; (2) model performance: evaluation of MitoPS performance in prognostic stratification and immunotherapy response prediction based on immune status (immune-hot vs immune-cold); (3) internal validation: verification of NDUFB10’s relationship with immune rejection through multiplex immunofluorescence and IHC, finding high NDUFB10 expression in CD8+T cell desert regions while low expression in areas with CD20+B cell infiltration; (4) experimental validation: confirmation through in vivo experiments and flow cytometry analysis that NDUFB10 knockdown enhanced infiltration of activated GZMB+CD8+ T cells and improved PD-1 blockade efficacy. IHC, Immunohistochemistry; MitoPS, Mitochondrial Pathway Signature; PD-1, programmed cell death 1 receptor.

Figure 2. Analysis of molecular characteristics of mitochondria-related signaling pathways in lung adenocarcinoma. (A) ssGSEA activity differences of 149 mitochondria-related signaling pathways between lung adenocarcinoma and normal samples. (B) PCA analysis of seven lung adenocarcinoma cohorts after batch effect removal (center) and chromosomal location map of differentially expressed prognostic mitochondria-related genes (outer ring), with red and black indicating genes highly expressed in tumor and normal tissues, respectively. (C) Waterfall plot of the top 30 most frequently mutated mitochondria-related proteins. (D) Expression heatmap of differentially expressed prognostic mitochondria-related genes. (E) Copy number variation analysis of differentially expressed prognostic mitochondria-related genes, showing genomic amplifications (AMP) and deletions (DEL). (F) Forest plot analysis of prognostic genes based on TCGA dataset. PCA, principal component analysis; ssGSEA, single-sample Gene Set Enrichment Analysis; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas.

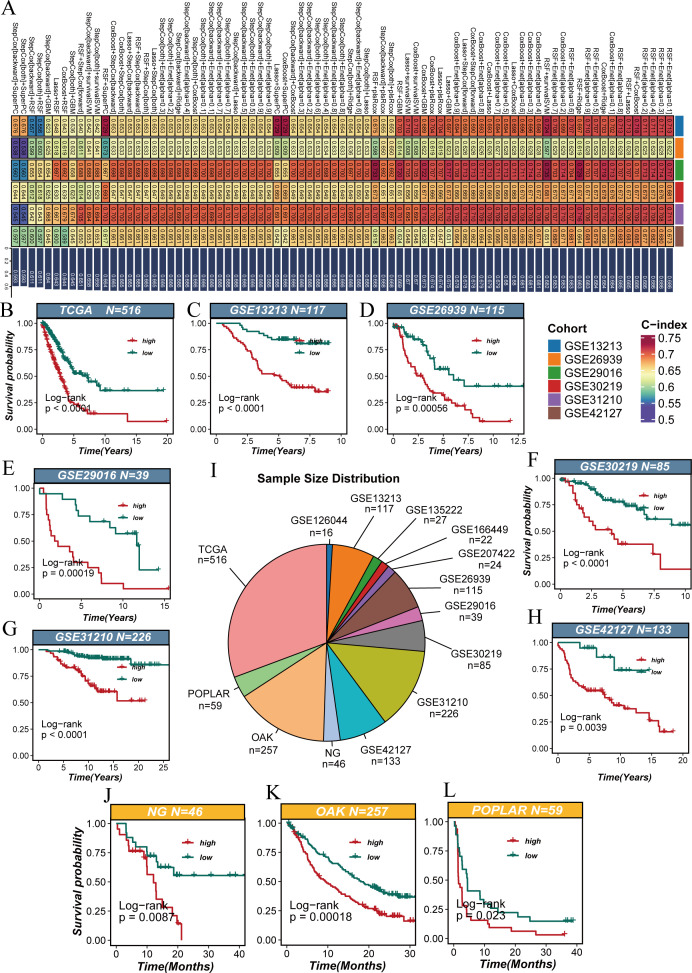

Multicohort validation of the MitoPS scoring system

We utilized ten machine learning algorithms to create all possible random pairwise combinations and identified the optimal model based on the highest C-index as the evaluation metric (figure 3A). To ensure the reliability of our findings, we integrated multiple independent cohorts from different databases, including TCGA (n=516), GSE13213 (n=117), GSE26939 (n=115), GSE29016 (n=39), GSE30219 (n=85), GSE31210 (n=226), GSE42127 (n=133), and immunotherapy-related cohorts such as POPLAR (n=59), OAK (n=257), and NG (n=46) (figure 3I). In survival analysis, patients were stratified into high and low score groups based on MitoPS scores. Results showed that in the TCGA cohort, patients with high scores had significantly shorter overall survival than those with low scores (p<0.0001, figure 3B). This finding was validated in the GSE13213 cohort (p<0.0001, figure 3C). Similar prognostic differences were observed in other independent cohorts, including GSE26939 (p=0.00056, figure 3D), GSE29016 (p=0.00019, figure 3E), GSE30219 (p<0.0001, figure 3F), GSE31210 (p<0.0001, figure 3G), and GSE42127 (p=0.0039, figure 3H). Notably, the MitoPS score also demonstrated good predictive value in cohorts of patients receiving immunotherapy. In the NG cohort (p=0.0087, figure 3J), OAK cohort (p=0.00018, figure 3K), and POPLAR cohort (p=0.023, figure 3L), high MitoPS scores were significantly associated with poor prognosis. Further analysis of immunotherapy response revealed that across multiple NSCLC immunotherapy cohorts, non-responders showed significantly higher MitoPS scores compared with responders (online supplemental figure 2A–G). This trend was most significant in the NG (p=0.0038) and was further validated in GSE126044 and GSE166449 cohorts (p<0.05). Although the differences did not reach statistical significance in other cohorts, the overall trend remained consistent. These results suggest that the MitoPS scoring system can not only predict the prognosis of patients receiving conventional treatment but may also help identify populations who might benefit from immunotherapy, providing important reference for clinical treatment decisions.

Figure 3. Multicohort validation of the MitoPS scoring system. (A) The optimal model identified by machine learning heatmap selection was used as the MitoPS scoring system. (B–H) Survival analysis of MitoPS scores in conventional treatment cohorts, including TCGA (B), GSE13213 (C), GSE26939 (D), GSE29016 (E), GSE30219 (F), GSE31210 (G), and GSE42127 (H). (I) Sample size distribution of validation cohorts. (J–L) Survival analysis of MitoPS scores in immunotherapy cohorts, including NG (J), OAK (K), and POPLAR (L). MitoPS, Mitochondrial Pathway Signature; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas.

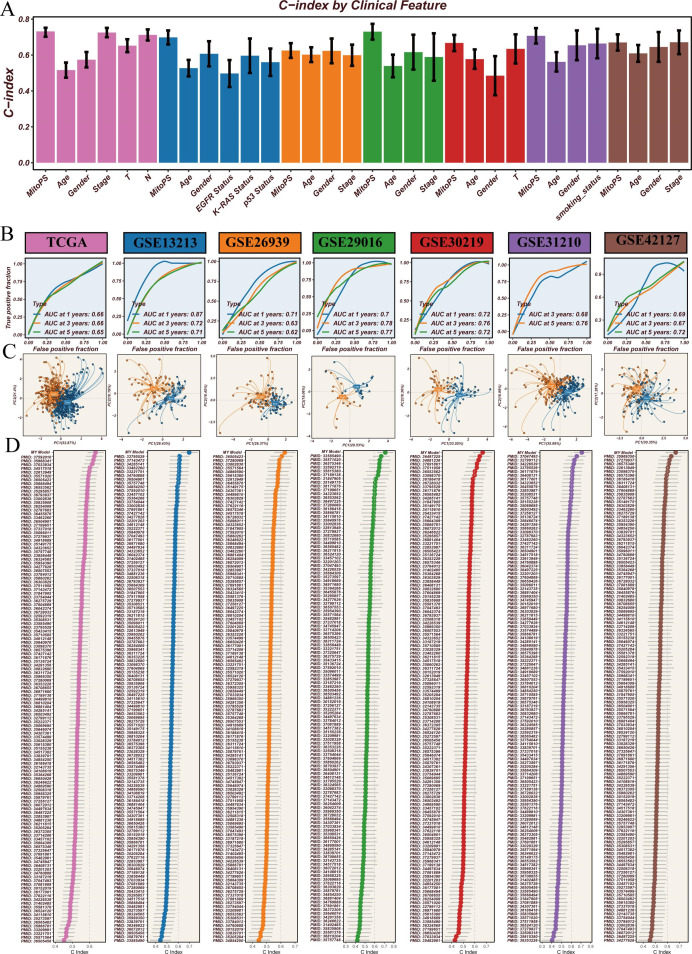

Validation of MitoPS scoring system’s predictive performance

To comprehensively evaluate the predictive performance of the MitoPS scoring system, we conducted a series of systematic analyses (figure 4). First, we compared MitoPS with existing clinical indicators for prognostic assessment. Results showed that MitoPS consistently outperformed traditional clinical features such as age, gender, and stage across all test cohorts, demonstrating the highest C-index values (figure 4A), confirming its superiority as a prognostic marker. Further time-dependent ROC curve analysis evaluated the long-term predictive capability of the MitoPS score. Results demonstrated stable predictive accuracy: in the TCGA cohort, area under the curve (AUC) values at 1, 3, and 5 years reached 0.66, 0.66, and 0.65, respectively. This predictive capability was consistently validated in other independent cohorts, including GSE13213 (AUC: 0.71–0.87), GSE26939 (AUC: 0.62–0.71), GSE29016 (AUC: 0.70–0.78), GSE30219 (AUC: 0.72-0.76), GSE31210 (AUC: 0.68–0.76), and GSE42127 (AUC: 0.67–0.72) (figure 4B). These results indicate reliable long-term predictive value of MitoPS. To assess the ability of the MitoPS scoring system to distinguish patients at the molecular level, we performed PCA based on the signature genes included in the model. Results showed that high-score and low-score samples exhibited distinct spatial distribution patterns across all validation cohorts (figure 4C). This significant clustering pattern confirms that MitoPS effectively distinguishes patient populations with different prognostic risks at the molecular level. Finally, we systematically compared MitoPS with 129 previously published prognostic signatures for LUAD. Through comparison of predictive performance across different signatures, we found that MitoPS demonstrated the highest C-index values across all validation cohorts (figure 4D). This systematic comparison revealed that MitoPS significantly outperformed all published prognostic models. In conclusion, through comparison with clinical indicators, evaluation of long-term predictive capability, molecular-level validation, and benchmarking against existing models, we have demonstrated the superior performance of the MitoPS scoring system in predicting LUAD prognosis from multiple perspectives.

Figure 4. Analysis of MitoPS scoring system’s predictive performance. (A) Comparison of C-index values between MitoPS and clinical features. (B) Time-dependent receiver operating characteristic curve analysis showing stable long-term predictive capability of MitoPS scores across cohorts. (C) Principal component analysis based on MitoPS signature genes showing distinct sample clustering. (D) Performance comparison between MitoPS and published prognostic signatures. AUC, area under the curve; C-index, concordance index; MitoPS, Mitochondrial Pathway Signature; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas.

Association analysis between MitoPS score and tumor immune microenvironment

To investigate the relationship between MitoPS score and tumor immune microenvironment, we conducted comprehensive immunological feature analyses. First, we systematically evaluated the immune cell composition in different MitoPS score groups. Heatmap analysis revealed significant differences in immune cell infiltration patterns between high and low score groups (figure 5A). Specifically, the low MitoPS group showed higher levels of immune cell infiltration, including T cells, B cells, and dendritic cells. Further immune function analysis revealed differences in immune characteristics between the groups. Radar plots showed that the low MitoPS group had higher levels of immune cell proportions (figure 5B), while there was no significant difference in immune functional characteristics (figure 5C). We conducted an in-depth analysis using The Cancer Immunome Atlas (TCIA) database, which serves as a comprehensive platform integrating various immune cell infiltration and functional indicators, where higher scores represent stronger antitumor immune responses. Results showed that patients with low MitoPS scores had significantly higher TCIA scores (p<0.05), indicating that these patients’ tumor microenvironments exist in a stronger immune-activated state (figure 5D–G). Regarding immune-related gene expression, we systematically analyzed co-stimulatory molecules, co-inhibitory molecules, and major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules (figure 5H). The low-MitoPS group showed significantly higher expression of certain key co-stimulatory molecules (including CD27 and CD28), which promote T-cell activation and proliferation, enhancing antitumor immune responses. Additionally, MHC class II molecules were highly expressed in the low-score group, facilitating antigen presentation and T-cell recognition. Correlation analysis further revealed significant associations between MitoPS scores and key immune features, including stromal score (figure 5I, r=−0.39), immune score (figure 5J, r=−0.4), ESTIMATE score (figure 5K, r=−0.41), and tumor purity (figure 5L, r=0.5). These results indicate that the MitoPS score not only reflects tumor prognosis but is also closely associated with the tumor immune microenvironment, potentially providing important reference for immunotherapy strategy development.

Figure 5. Association analysis between MitoPS score and tumor immune microenvironment. (A) Heatmap of immune cell infiltration. (B–C) Radar plots of immune cell proportions and functional characteristics. (D–G) The Cancer Immunome Atlas analysis. (H) Heatmap of immune-related gene expression. (I–L) Correlation analysis between MitoPS score and key immune features. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001. aDC, activated dendritic cell; APC, antigen-presenting cell; CCR, chemokine receptor; DCs, dendritic cells; HLA, human leukocyte antigen; IFN, interferon; iDC, immature dendritic cell; MitoPS, mitochondrial pathway signature; MHC, major histocompatibility complex; NK, natural killer; pDC, plasmacytoid dendritic cell; TIL, tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte; Treg, regulatory T cell.

Single-cell sequencing reveals the relationship between MitoPS score and tumor microenvironment

To gain deeper insights into the relationship between MitoPS scores and the tumor microenvironment, we performed single-cell RNA sequencing analysis (figure 6). Through t-SNE clustering analysis, we identified 12 major cell types, including T cells, B cells, natural killer cells, macrophages, monocytes, dendritic cells, plasma cells, regulatory T cells, proliferating cells, mast cells, epithelial cells, and fibroblasts (figure 6A). The distribution of MitoPS scores showed distinct heterogeneity among these cell populations (figure 6B). The distribution of scores across cell types was visualized using violin plots (figure 6D), with proliferating cells showing the highest MitoPS scores, consistent with the crucial role of mitochondria in cell proliferation. Cell proportion analysis revealed significant differences in immune cell composition between high and low MitoPS groups (figure 6C). The low-MitoPS group exhibited higher proportions of T cells and B cells infiltration, but lower proportions of macrophages and dendritic cells, suggesting distinct roles of different immune cell subsets in the tumor microenvironment. Cell communication network analysis revealed differences in cellular interactions between high and low score groups. The high MitoPS group demonstrated more complex and stronger intercellular communication networks (figure 6F), while cellular interactions in the low MitoPS group were relatively weaker (figure 6E). Heatmap analysis further illustrated differences in the number (figure 6G) and strength (figure 6H) of cellular interactions, with the high-score group showing more active cell communication. Analysis of cellular communication input–output strengths (figure 6I,J) revealed significantly higher interaction intensities in the high-score group compared with the low-score group, indicating more active intercellular communication networks. Differential signaling pathway analysis and intercellular signaling pathway activity analysis (figure 6K,L) revealed significant activation of key pathways such as PDGF and CDH1 in the high-score group, which promoted tumor cell proliferation, migration, and invasion through regulation of intercellular communication networks. These results indicate that the MitoPS score not only reflects characteristics of individual cell types but is also closely associated with complex interaction networks in the tumor microenvironment. The high-score group exhibited more active cellular communication and activation of tumor-related signaling pathways, which may promote tumor progression.

Figure 6. Single-cell sequencing analysis reveals tumor microenvironment characteristics associated with MitoPS score. (A) t-SNE clustering of cell types. (B) Distribution of MitoPS scores. (C) Stacked bar plot of cell proportions in high/low score groups. (D) Violin plots of MitoPS score distribution across cell types. (E–F) Cell communication networks in low/high score groups. (G–H) Heatmaps of cellular interaction numbers and strengths. (I–J) Scatter plots of cellular communication input–output strengths. (K) Differential signaling pathway analysis. (L) Heatmap of intercellular signaling pathway activity. MitoPS, Mitochondrial Pathway Signature; NK, natural killer; t-SNE, t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding.

Systematic validation of NDUFB10 expression and immune infiltration patterns

Through analysis of the genes constituting the MitoPS score model, we identified NDUFB10 as a key component, showing significant positive correlation with MitoPS score (r=0.38, q=0) (online supplemental figure 3A). To systematically validate the clinical significance of NDUFB10, we first analyzed the Kaplan-Meier (KM) plotter database and found that high NDUFB10 expression was significantly associated with poor patient prognosis (HR=1.53, 95% CI: 1.18 to 1.97, log-rank p=0.00099) (online supplemental figure 3B). This result was validated in our cohort, where patients with high expression also demonstrated poorer overall survival (figure 7E) and disease-free survival (figure 7F). To investigate the relationship between NDUFB10 expression and immune infiltration, we first analyzed the correlation between NDUFB10 and CD8A expression in two independent cohorts: TCGA and OAK. Results showed significant negative correlations in both cohorts (TCGA: r=−0.23, p=2.1e−07; OAK: r=−0.3, p=2e−07) (online supplemental figure 3C, D). Further validation through immunohistochemistry results from the Human Protein Atlas database revealed significantly higher NDUFB10 expression in lung cancer tissues (figure 7A,B) compared with normal lung tissues (figure 7C,D). Based on the spatial distribution characteristics of CD8+T cells, we classified patients into three immune infiltration patterns: desert, excluded, and inflamed. This classification effectively stratified patients with LUAD in terms of overall survival (figure 7G) and disease-free survival (figure 7H). Further analysis revealed that desert-type patients showed the highest NDUFB10 expression levels (figure 7I), suggesting NDUFB10’s potential role in regulating immune cell infiltration. Based on this finding, we stratified patients into high and low expression groups according to NDUFB10 immunohistochemistry scores (figure 7J), and found that the high expression group had significantly shorter overall survival (figure 7K) and disease-free survival (figure 7L). Multiplex immunofluorescence staining (figure 7M) further validated the spatial relationship between NDUFB10 expression and immune markers (CD3D and CD20), with the high expression group showing lower immune cell infiltration. These results systematically demonstrate that NDUFB10, as a key gene in the MitoPS score, is closely associated with immune desert microenvironment and poor patient prognosis when highly expressed, suggesting its potential role in regulating tumor progression through modulation of immune cell infiltration.

Figure 7. Analysis of NDUFB10 expression and immune infiltration. (A–B) Immunohistochemical staining of NDUFB10 in lung cancer tissues. (C–D) Immunohistochemical staining of NDUFB10 in normal lung tissues. (E–F) Relationship between NDUFB10 expression levels and patient survival. (G–H) Relationship between CD8-based immune infiltration patterns and patient survival. (I) Distribution of NDUFB10 expression levels across three immune infiltration patterns. (J) Histological features of high and low NDUFB10 immunohistochemistry score groups. (K–L) Relationship between NDUFB10 expression levels and patient prognosis. (M) Multiplex immunofluorescence staining of NDUFB10, CD3D, and CD20. DFS, disease-free survival; IHC, immunohistochemistry; OS, overall survival.

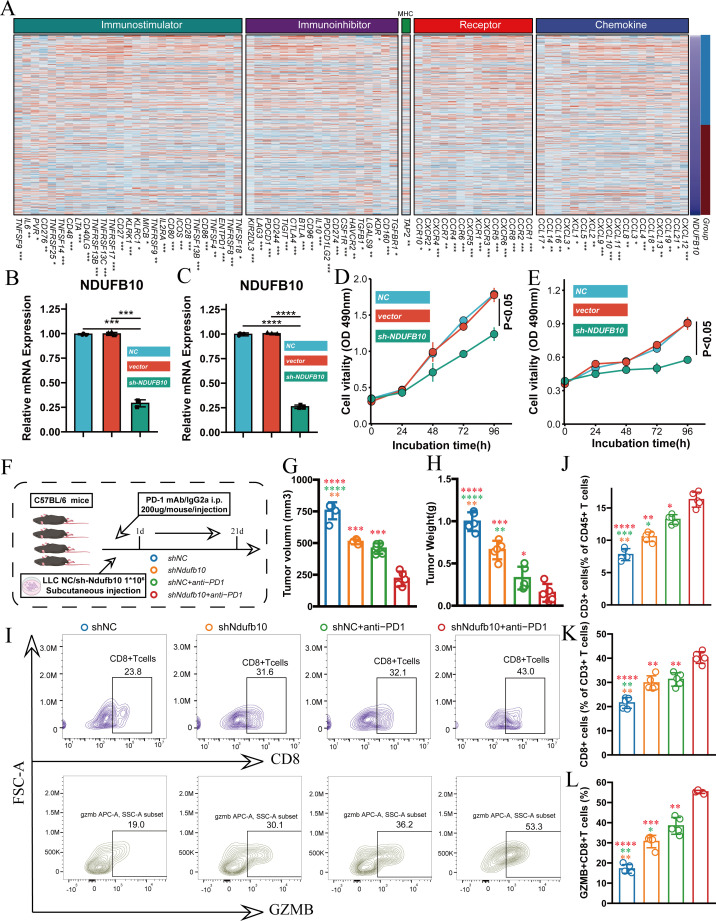

Investigation of NDUFB10’s role in immune regulation and immune checkpoint inhibition therapy

To understand the mechanism of NDUFB10 in tumor immunity, we first analyzed the association between NDUFB10 expression and immune-related genes based on TCGA database. Heatmap analysis revealed significant negative correlations between NDUFB10 expression and various immune regulatory genes, categorized into four main groups: immunostimulators, immunoinhibitors, receptors, and chemokines. Notable negative correlations were observed with immunostimulatory molecules (including ENTPD1, TNFSF4, CD80, TNFSF13B, CD86), immunoinhibitory molecules (including TIGIT, CD96, PDCD1, PDCD1LG2), as well as various receptors and chemokines (online supplemental figure 4). These results were validated in the OAK cohort (figure 8A), further supporting that NDUFB10 might influence the tumor immune microenvironment by suppressing these immune-related genes. To validate the functional role of NDUFB10, we established stable NDUFB10 knockdown cell lines in both A549 and H1299 cells. qRT-PCR validation showed effective reduction of NDUFB10 expression by two different shRNA sequences (figure 8B,C), and CCK-8 assays demonstrated that NDUFB10 knockdown significantly inhibited tumor cell proliferation (figure 8D,E). To further validate the impact of NDUFB10 knockdown on immune checkpoint inhibition therapy, we established a mouse tumor model using LLC cells with anti-PD-1 treatment (figure 8F). Compared with the control group, the NDUFB10 knockdown group showed significant inhibition of tumor growth. When NDUFB10 knockdown was combined with anti-PD-1 treatment, tumor volume (figure 8G) and weight (figure 8H) were further reduced compared with single treatment groups, demonstrating the best therapeutic effect. Flow cytometry analysis revealed significantly increased proportions of CD8+T cells in tumor tissues from the NDUFB10 knockdown group (figure 8I), along with increased percentages of CD45+ and CD3+ T cells (figure 8J,K). Importantly, the proportion of GZMB+CD8+ T cells was significantly elevated in the NDUFB10 knockdown group (figure 8L), indicating enhanced T-cell cytotoxic function. These effects were more pronounced in the combination treatment group with anti-PD-1. These findings systematically demonstrate that NDUFB10 influences the tumor immune microenvironment by regulating multiple immune-related genes, and its knockdown not only directly inhibits tumor growth but also enhances the efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibition therapy by promoting T-cell infiltration and function.

Figure 8. NDUFB10 knockdown enhances the efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibition. (A) Correlation heatmap between NDUFB10 expression and immune-related genes in OAK cohort. (B–C) Validation of NDUFB10 knockdown efficiency using two shRNA sequences in A549 and H1299 cell lines. (D–E) CCK-8 assays showing the effect of NDUFB10 knockdown on A549 and H1299 cell proliferation. (F) Schematic diagram of mouse experimental design using LLC cells. (G–H) Comparison of tumor volume and weight among groups. (I–L) Flow cytometry analysis of CD8+T cells, CD45+cells, CD3+T cells, and GZMB+CD8+ T cells proportions in tumor tissues from different groups. CCK-8, Cell Counting Kit-8; i.p., intraperitoneal injection; LLC, Lewis lung carcinoma; mAb, monoclonal antibody; MHC, major histocompatibility complex; mRNA, messenger RNA; PD-1, programmed cell death 1 receptor.

Discussion

Despite the promise of ICIs for patients with advanced LUAD, a significant proportion still fail to benefit from this treatment.45 Traditional research has focused on biomarkers like PD-L1 expression and TMB,46 47 but studies by Rizvi et al48 and Garon et al49 revealed clear limitations, prompting exploration of new predictive markers. Recently, the relationship between mitochondrial function and immunotherapy efficacy has attracted attention,50 51 with Chamoto et al52 finding that enhanced mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation improves anti-PD-1 treatment, while Watson et al53 confirmed that lactate accumulation in the tumor microenvironment promotes immune suppression. Unlike previous studies, we systematically investigated mitochondria-related pathways in LUAD immune microenvironment, observing significant activation of mitochondrial pathways in tumor samples, further revealing the negative correlation between NDUFB10 expression and CD8+T cell spatial distribution, and developing the MitoPS scoring system that not only reflects mitochondrial functional status but also predicts immunotherapy response, providing new perspectives for tumor metabolic reprogramming research.

A key finding of our study is the development of the MitoPS scoring system. Unlike existing prognostic models that primarily rely on immune cell markers or metabolic indicators,54 55 MitoPS integrates both mitochondrial function and immune characteristics, demonstrating robust predictive capability across multiple independent cohorts. Notably, in immunotherapy cohorts (POPLAR, OAK, and NG), MitoPS effectively identified treatment-benefiting populations, providing new insights into immunotherapy prediction. Importantly, systematic comparison with 129 published prognostic signatures demonstrated MitoPS’s superior predictive performance, highlighting the significance of incorporating mitochondrial function into prognostic assessment. Through integrative analysis, we revealed important connections between mitochondrial function and the tumor immune microenvironment. Our single-cell RNA sequencing analysis demonstrated how mitochondrial functional states influence the dynamics and interactions of different immune cell subgroups. Specifically, we found that low MitoPS scores correlated with increased immune cell infiltration and more active antitumor immune responses, a correlation validated across multiple independent cohorts. This multidimensional analytical approach provides new insights into understanding the complexity of the tumor immune microenvironment.

Another significant finding of our study is the identification of NDUFB10 as a potential immune modulator in LUAD. Through multiomics analysis, we identified NDUFB10 as one of the core genes in our MitoPS scoring system (r=0.38, p<0.05), with its expression level significantly positively correlated with MitoPS scores, indicating NDUFB10’s critical role in regulating mitochondrial function and tumor immune microenvironment. While NDUFB10 is known as a mitochondrial complex I assembly factor, our research is the first to reveal its role in modulating tumor immunity. Immunofluorescence staining validated that NDUFB10 expression strongly correlates with immune desert phenotype and poor patient prognosis, consistent with the immunosuppressive characteristics observed in our high MitoPS score group. Functional validation further confirmed that NDUFB10 knockdown not only directly inhibited tumor growth but also significantly enhanced anti-PD-1 treatment efficacy. Specifically, NDUFB10 knockdown increased the proportion of tumor-infiltrating CD8+T cells, particularly GZMB+CD8+ T cells, along with elevated percentages of CD45+ and CD3+ T cells. These effects were more pronounced when combined with anti-PD-1 treatment, suggesting NDUFB10 as a novel therapeutic target for overcoming immunotherapy resistance in patients with high MitoPS scores, providing a molecular basis for individualized precision treatment strategies based on the MitoPS scoring system.

However, translating these findings into clinical practice faces several challenges. First, while MitoPS shows promising performance in retrospective cohorts, prospective clinical trials are needed to validate its predictive value. Second, the specific molecular mechanisms by which NDUFB10 regulates the immune microenvironment require further elucidation, particularly its interaction networks with other immune regulatory pathways. Third, developing NDUFB10-targeted therapeutics requires careful consideration of its function in normal tissues to ensure treatment safety. Based on our findings, future research directions may include:1 investigating the immune regulatory networks mediated by NDUFB10,2 exploring NDUFB10-targeted therapeutic strategies,3 studying mitochondrial function-based immunotherapy optimization approaches, and4 conducting prospective clinical validation studies.

In conclusion, this study systematically investigated the role of mitochondrial function in LUAD immune regulation and identified NDUFB10 as a potential therapeutic target, providing new strategies for improving immunotherapy efficacy. The establishment of the MitoPS scoring system may aid in patient stratification and personalized treatment decisions, offering new directions for LUAD treatment research.

Supplementary material

Footnotes

Funding: This work was supported by the Tianjin Natural Science Foundation under Grant/Award Number 21JCYBJC01020, and funded by Tianjin Key Medical Discipline (Specialty) Construction Project (TJYXZDXK-011A).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not applicable.

Ethics approval: Our research methodology aligned with Helsinki Declaration standards and was endorsed by the Ethics Board of Tianjin Medical University Cancer Institute and Hospital (Registration bc2023152). Participants were enrolled only after providing documented informed consent.

Data availability free text: The data that support the findings of this study are available from multiple public databases and repositories. Single-cell RNA sequencing data were obtained from CRA001963 (National Genomics Data Center), GSE123904 (Gene Expression Omnibus), and PRJNA591860 (NCBI Sequence Read Archive). Bulk RNA sequencing data were accessed from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA-LUAD, http://cancergenome.nih.gov/) and Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx). Independent validation cohorts were collected from Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) database (GSE13213, GSE26939, GSE29016, GSE30219, GSE31210, and GSE42127). Immunotherapy cohorts data were obtained from previously published studies (POPLAR, OAK, and NG cohorts) and GEO datasets (GSE126044, GSE135222, GSE166449, and GSE207422). Somatic mutation and copy number variation data were retrieved from UCSC Xena data portal (https://xena.ucsc.edu/), and mitochondrial pathway information was sourced from the MitoCarta3.0 database. The processed data used in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. All other data are available in the main text or the supplementary materials.

Data availability statement

Data are available in a public, open access repository.

References

- 1.Prince SS, Chijioke O, Bubendorf L. Unravelling lung adenocarcinoma with mucinous histology and its translational implications. Ann Oncol. 2025;36:235–7. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2025.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yu Z, Tang H, Chen S, et al. Exosomal LOC85009 inhibits docetaxel resistance in lung adenocarcinoma through regulating ATG5-induced autophagy. Drug Resist Updat. 2023;67:100915. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2022.100915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tan N, Li Y, Ying J, et al. Histological transformation in lung adenocarcinoma: Insights of mechanisms and therapeutic windows. J Transl Int Med. 2024;12:452–65. doi: 10.1515/jtim-2024-0019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zeng Y, Hu CH, Li YZ, et al. Association between pretreatment emotional distress and immune checkpoint inhibitor response in non-small-cell lung cancer. Nat Med. 2024;30:1680–8. doi: 10.1038/s41591-024-02929-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ederhy S, Cadranel J, Granger C, et al. Investigation of endocarditis finds advanced lung adenocarcinoma: both resolve after tyrosine kinase inhibitor treatment. The Lancet. 2024;403:860–1. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(24)00042-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kondo KK, Rahman B, Ayers CK, et al. Lung cancer diagnosis and mortality beyond 15 years since quit in individuals with a 20+ pack-year history: A systematic review. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74:84–114. doi: 10.3322/caac.21808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rizzo A, Ricci AD. PD-L1, TMB, and other potential predictors of response to immunotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: how can they assist drug clinical trials? Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2022;31:415–23. doi: 10.1080/13543784.2021.1972969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li J, Cao Y, Liu Y, et al. Multiomics profiling reveals the benefits of gamma-delta (γδ) T lymphocytes for improving the tumor microenvironment, immunotherapy efficacy and prognosis in cervical cancer. J Immunother Cancer. 2024;12:e008355. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2023-008355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schmitt AM, Larkin J, Patel SP. Dual Immune Checkpoint Inhibition in Melanoma and PD-L1 Expression: The Jury Is Still Out. J Clin Oncol. 2025;43:122–4. doi: 10.1200/JCO-24-01572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang X, Lamberti G, Di Federico A, et al. Tumor mutational burden for the prediction of PD-(L)1 blockade efficacy in cancer: challenges and opportunities. Ann Oncol. 2024;35:508–22. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2024.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sprenger H-G, Mittenbühler MJ, Sun Y, et al. Ergothioneine controls mitochondrial function and exercise performance via direct activation of MPST. Cell Metab. 2025;37:857–69. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2025.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mao Y, Zhang J, Zhou Q, et al. Hypoxia induces mitochondrial protein lactylation to limit oxidative phosphorylation. Cell Res. 2024;34:13–30. doi: 10.1038/s41422-023-00864-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jacquemin G, Margiotta D, Kasahara A, et al. Granzyme B-induced mitochondrial ROS are required for apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2015;22:862–74. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2014.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kimura T, Murakami F. Evidence that dendritic mitochondria negatively regulate dendritic branching in pyramidal neurons in the neocortex. J Neurosci. 2014;34:6938–51. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5095-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ling Z, Ge X, Jin C, et al. Copper doped bioactive glass promotes matrix vesicles-mediated biomineralization via osteoblast mitophagy and mitochondrial dynamics during bone regeneration. Bioact Mater. 2025;46:195–212. doi: 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2024.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Naresh NU, Haynes CM. Breaks in mitochondrial DNA rig the immune response. Nature New Biol. 2021;591:372–3. doi: 10.1038/d41586-021-00429-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ma S, Chee J, Fear VS, et al. Pre-treatment tumor neo-antigen responses in draining lymph nodes are infrequent but predict checkpoint blockade therapy outcome. Oncoimmunology. 2020;9:1684714. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2019.1684714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Creaney J, Ma S, Sneddon SA, et al. Strong spontaneous tumor neoantigen responses induced by a natural human carcinogen. Oncoimmunology. 2015;4:e1011492. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2015.1011492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buttgereit T, Pfeiffenberger M, Frischbutter S, et al. Inhibition of Complex I of the Respiratory Chain, but Not Complex III, Attenuates Degranulation and Cytokine Secretion in Human Skin Mast Cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:11591. doi: 10.3390/ijms231911591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tomida S, Takeuchi T, Shimada Y, et al. Relapse-related molecular signature in lung adenocarcinomas identifies patients with dismal prognosis. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2793–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.7053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilkerson MD, Yin X, Walter V, et al. Differential pathogenesis of lung adenocarcinoma subtypes involving sequence mutations, copy number, chromosomal instability, and methylation. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e36530. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Staaf J, Jönsson G, Jönsson M, et al. Relation between smoking history and gene expression profiles in lung adenocarcinomas. BMC Med Genomics. 2012;5:22. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-5-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rousseaux S, Debernardi A, Jacquiau B, et al. Ectopic activation of germline and placental genes identifies aggressive metastasis-prone lung cancers. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:186ra66. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yamauchi M, Yamaguchi R, Nakata A, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase defines critical prognostic genes of stage I lung adenocarcinoma. PLoS One. 2012;7:e43923. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tang H, Xiao G, Behrens C, et al. A 12-Gene Set Predicts Survival Benefits from Adjuvant Chemotherapy in Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer Patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:1577–86. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-2321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang Y, Parmigiani G, Johnson WE. ComBat-seq: batch effect adjustment for RNA-seq count data. NAR Genomics and Bioinformatics . 2020;2:lqaa078. doi: 10.1093/nargab/lqaa078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patil NS, Nabet BY, Müller S, et al. Intratumoral plasma cells predict outcomes to PD-L1 blockade in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Cell. 2022;40:289–300. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2022.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ravi A, Hellmann MD, Arniella MB, et al. Genomic and transcriptomic analysis of checkpoint blockade response in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Nat Genet. 2023;55:807–19. doi: 10.1038/s41588-023-01355-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cho JW, Hong MH, Ha SJ, et al. Genome-wide identification of differentially methylated promoters and enhancers associated with response to anti-PD-1 therapy in non-small cell lung cancer. Exp Mol Med. 2020;52:1550–63. doi: 10.1038/s12276-020-00493-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jung H, Kim HS, Kim JY, et al. DNA methylation loss promotes immune evasion of tumours with high mutation and copy number load. Nat Commun. 2019;10:4278. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-12159-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee JS, Nair NU, Dinstag G, et al. Synthetic lethality-mediated precision oncology via the tumor transcriptome. Cell. 2021;184:2487–502. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.03.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hu J, Zhang L, Xia H, et al. Tumor microenvironment remodeling after neoadjuvant immunotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer revealed by single-cell RNA sequencing. Genome Med. 2023;15:14. doi: 10.1186/s13073-023-01164-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rath S, Sharma R, Gupta R, et al. MitoCarta3.0: an updated mitochondrial proteome now with sub-organelle localization and pathway annotations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49:D1541–7. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen Y, Chen S, Lei EP. DiffChIPL: a differential peak analysis method for high-throughput sequencing data with biological replicates based on limma. Bioinformatics. 2022;38:4062–9. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btac498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Luo K, Qian Z, Jiang Y, et al. Characterization of the metabolic alteration-modulated tumor microenvironment mediated by TP53 mutation and hypoxia. Comput Biol Med. 2023;163:107078. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2023.107078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang L, Cui Y, Zhou G, et al. Leveraging mitochondrial-programmed cell death dynamics to enhance prognostic accuracy and immunotherapy efficacy in lung adenocarcinoma. J Immunother Cancer . 2024;12:e010008. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2024-010008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang P, Wang D, Zhou G, et al. Novel post-translational modification learning signature reveals B4GALT2 as an immune exclusion regulator in lung adenocarcinoma. J Immunother Cancer . 2025;13:e010787. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2024-010787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Van Allen EM, Miao D, Schilling B, et al. Genomic correlates of response to CTLA-4 blockade in metastatic melanoma. Science. 2015;350:207–11. doi: 10.1126/science.aad0095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li T, Fan J, Wang B, et al. TIMER: A Web Server for Comprehensive Analysis of Tumor-Infiltrating Immune Cells. Cancer Res. 2017;77:e108–10. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-0307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cao Y, Fu L, Wu J, et al. Integrated analysis of multimodal single-cell data with structural similarity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022;50:e121. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkac781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jin S, Guerrero-Juarez CF, Zhang L, et al. Inference and analysis of cell-cell communication using CellChat. Nat Commun. 2021;12:1088. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21246-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thai AA, Solomon BJ, Sequist LV, et al. Lung cancer. Lancet. 2021;398:535–54. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00312-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang Y, Safi M, Hirsch FR, et al. Immunotherapy for advanced-stage squamous cell lung cancer: the state of the art and outstanding questions. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2025;22:200–14. doi: 10.1038/s41571-024-00979-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ikeda H, Kawase K, Nishi T, et al. Immune evasion through mitochondrial transfer in the tumour microenvironment. Nature New Biol. 2025;638:225–36. doi: 10.1038/s41586-024-08439-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Di Federico A, Hong L, Elkrief A, et al. Lung adenocarcinomas with mucinous histology: clinical, genomic, and immune microenvironment characterization and outcomes to immunotherapy-based treatments and KRASG12C inhibitors. Ann Oncol. 2025;36:297–308. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2024.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim ES, Velcheti V, Mekhail T, et al. Blood-based tumor mutational burden as a biomarker for atezolizumab in non-small cell lung cancer: the phase 2 B-F1RST trial. Nat Med. 2022;28:939–45. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01754-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Di Federico A, Alden SL, Smithy JW, et al. Intrapatient variation in PD-L1 expression and tumor mutational burden and the impact on outcomes to immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2024;35:902–13. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2024.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rizvi NA, Hellmann MD, Snyder A, et al. Cancer immunology. Mutational landscape determines sensitivity to PD-1 blockade in non-small cell lung cancer. Science. 2015;348:124–8. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Garon EB, Rizvi NA, Hui R, et al. Pembrolizumab for the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2018–28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1501824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hwang S-M, Awasthi D, Jeong J, et al. Transgelin 2 guards T cell lipid metabolism and antitumour function. Nature New Biol. 2024;635:1010–8. doi: 10.1038/s41586-024-08071-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Baldwin JG, Heuser-Loy C, Saha T, et al. Intercellular nanotube-mediated mitochondrial transfer enhances T cell metabolic fitness and antitumor efficacy. Cell. 2024;187:6614–30. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2024.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chamoto K, Chowdhury PS, Kumar A, et al. Mitochondrial activation chemicals synergize with surface receptor PD-1 blockade for T cell-dependent antitumor activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114:E761–70. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1620433114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Watson MJ, Vignali PDA, Mullett SJ, et al. Metabolic support of tumour-infiltrating regulatory T cells by lactic acid. Nature New Biol. 2021;591:645–51. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-03045-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Deng F, Xiao G, Tanzhu G, et al. Predicting Survival Rates in Brain Metastases Patients from Non‐Small Cell Lung Cancer Using Radiomic Signatures Associated with Tumor Immune Heterogeneity. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2025;12:e2412590. doi: 10.1002/advs.202412590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lin H, Hua J, Wang Y, et al. Prognostic and predictive values of a multimodal nomogram incorporating tumor and peritumor morphology with immune status in resectable lung adenocarcinoma. J Immunother Cancer . 2025;13:e010723. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2024-010723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available in a public, open access repository.