Abstract

Background

Antibiotic resistance is a worldwide problem causing significant health-related and economic losses. Gram-positive causes of urinary tract infections (UTIs) are usually underestimated or overlooked by physicians.

Aim

To examine the prevalence of antibiotic resistance among major gram-positive bacteria from UTIs in a tertiary care health hospital in southern Saudi Arabia.

Method

A cross-sectional retrospective study was done in a tertiary health setting in southern Saudi Arabia between 2019 and 2022, to identify the major gram-positive bacteria and antibiotic resistance. Data were collected from the hospital records and was analyzed using the SPSS statistical package.

Results

The most common gram-positive species were Enterococcus faecalis (44.7%), Staphylococcus aureus (15.1%), and Enterococcus faecium (12.9%), beta-hemolytic streptococci (8.4%), and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) (1.8%). The 1540 isolates showed an overall susceptibility of 71.0%, compared to a resistance of 29.0%. The most resistance was among Enterococcus faecium (54.5%), Enterococcus gallinarum (42.4%), Enterococcus faecalis (34.3%), and MRSA (27.2%). The most common resistance was to erythromycin (75.7%), followed by cefotaxime (73.9%), tetracycline (70.5%), ciprofloxacin (54.3%), and Synercid (53.6%). The prediction model indicates an increase in the prevalence of resistance in MRSA and, to a lesser extent, with E. faecalis, E. faecium, and beta-hemolytic streptococci.

Conclusions

Enterococcus faecalis was the predominant gram-positive species, surpassing Staphylococcus aureus. Almost remarkable resistance was observed to most of the antibiotics that are frequently used in the study area, mainly erythromycin, cefotaxime, and tetracycline. Performing continuous monitoring of drug susceptibility may help with the empirical treatment of bacterial agents in the region.

Introduction

The development of antibiotic resistance has become a serious worldwide health issue that makes treating infectious infections effectively extremely difficult. The abuse and misuse of antibiotics, inadequate infection control procedures, and the dearth of newly developed medications are some of the reasons contributing to the emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Globally, this problem causes significant health and financial damage [1]. Microbial resistance to antibiotics is a global health concern. Resistance mechanisms include β-lactamase production, efflux pumps or target site modifications leading to multidrug resistance bacteria emergence [2–4].

Information on the existence of the causative microorganisms and their susceptibility to commonly used antibiotics are essential to enhance therapeutic outcome [5–7]. Antimicrobial resistance and urinary tract infections continue to be the principal issues, bearing a heavy social and health cost, especially in developing nations. Escherichia coli is the main Gram-negative bacteria that typically causes this infection. Repeated reports of failure of empirical treatment in UTIs and reports of gram-positive bacteria as an important cause of UTIs evoked us to check the rates of infection and antimicrobial resistance pattern in Saudi Arabia [8].

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are one of the most prevalent bacterial illnesses affecting millions of people worldwide [9]. Although there are many several types of bacteria that can cause UTIs, gram-negative bacteria, namely E. coli is the utmost common cause. Nonetheless, gram-positive bacteria have also been recognized as significant contributors to the burden of UTIs, comprising Enterococcus and Staphylococcus species [9–11].

Globally, UTIs placed amongst the most widespread bacterial infections, affecting approximately 150 million persons each year [9]. Gram-negative bacteria as E. coli and Gram-positive organisms as Staphylococcus saprophyticus are the main causes of UTIs, which can develop in the urinary tract, comprising the urethra, bladder, ureters, and kidneys [12]. The burden of UTIs is substantial, with women being mostly affected with up to a 50% risk of acquiring a UTI [13]. Recurring UTIs are also common complaint, with 20–30% of women facing a repeat infection within 6 months of the original incident [14]. A leading case of the significant financial burden of healthcare for UTIs is the about $2.8 billion that are encountered each year in the United States alone [9].

In Saudi Arabia, numerous reports have investigated the epidemiology of UTIs, with an emphasis on the etiology and antimicrobial resistance patterns [15–17]. These studies have underlined the increasing prevalence of gram-positive bacteria as causative agents of UTIs in the region. For example, a retrospective study conducted in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, found that Enterococcus spp. accounted for up to 20% of UTI isolates [15]. The growing concern in Saudi Arabia about the event of antibiotic resistance, mainly to regularly administered drugs as trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and fluoroquinolones, is important [18,19]. High incidence of resistance was reported in Saudi Arabia for Staphylococcus aureus, 100% for cefazolin, 90.5% for fosfomycin, and 94% for fusidic acid; and for Enterococcus species, 97.3% for linezolid, 93% for vancomycin and 80.9% for nitrofurantoin [20].

The burden of Gram-positive bacteria in UTIs in the Aseer region of Saudi Arabia has received little attention. A previous study found that E. coli was the predominant pathogen; Gram-positive bacteria like Staphylococcus saprophyticus and Enterococcus species were also important pathogens [21] This pattern in Aseer region is in harmony with data from Saudi Arabia. Alzohairy and Khadri [22] stated that Gram-positive cocci represented 30–40% of UTI isolates countrywide, draw attention to the increased awareness and suitable management policies. A study from Aseer region found that the majority of the uro-pathogens revealed resistance to widely used antibiotics [21]. In contrast, among all uro-pathogens, vancomycin, daptomycin, and linezolid revealed the least resistance. Given their efficiency against resistant uropathogens, the data suggest that these antibiotics might be considered for empirical therapy of UTIs. Related research suggested the use of fosfomycin, cefoxitin, nitrofurantoin, and amoxicillin/clavulanate as the preferred first-line treatment options for UTIs. This recommendation is based on the relatively high in vitro activity of these antibiotics against the major bacterial causes of UTIs [23]. For more efficient UTI treatment, the researchers advise updating guidelines to include this latest antibiotic susceptibility data.

The purpose of this study was to look into the frequency of antibiotic resistance in common gram-positive bacteria that cause UTIs at a large southern Saudi Arabian tertiary care hospital.

Materials and methods

Study design

This study used a retrospective, cross-sectional design. The research investigated culture and antimicrobial susceptibility information gathered from patients (n = 1540) during 2019 and 2022 in a southern Saudi Arabian tertiary care health setting. Data was accessed on 20th of January 2025. All patient records presented with UTIs as the main complaint and had complete records were recruited for this study without age, gender or severity restrictions.

Data collection

The research identified the main urinary tract infection (UTI) gram-positive bacteria and analyzed the frequency of antibiotic resistance. Results of culture and antibiotic sensitivity of the bacterial isolates were collected from the record of the microbiology unit for the study period.

Ethical consideration

The data collection was done after obtaining official permission from the King Khalid University institutional review board (ECME#2025-103). Data were collected anonymously. No data can reveal the identity of individual participants during or after data collection were accessed. Each patient submitted an informed consent to Aseer Central Hospital allowing the use of anonymous data for further analysis by Ministry of Health or other collaborators to help improving medical practice in Saudi Arabia.

Clinical specimens and bacterial isolates

A specimen of midstream urine was collected and delivered to the microbiology lab for culture in a sterile collection tube. Before any samples were processed in the lab and cultured, they were all kept in the refrigerator. A loop full from each specimen was streaked onto MacConkey agar and blood agar plates, plates were incubated aerobically at 37°C for 24–48 hours.

Culture was considered positive by the presence of visible colony growth. Initially, a few morphological traits were used to identify the bacterial species, including Gram stain, culture, and biochemical tests then verified using the automatic Vitek microbial identification system in line with the guidelines provided by the manufacturer (BioMérieux SA, Marcy, France).

Antimicrobial susceptibility tests

The resistance and sensitivity profiles for the isolated microbial species were determined using the automated Vitek system, in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol (BioMérieux). We have examined 24 agents (plus a few others that are used less frequently). The five agents that have been used mostly are Synercid, ciprofloxacin, tetracycline, cefotaxime, and erythromycin.

Data analysis

Using the statistical software program SPSS, the collected data was entered, inspected and analyzed. Descriptive statistics were computed to give an overview of the data. A bivariate logistic regression model was utilized to examine the association between the predictor variables, the organisms, and the antimicrobial drugs, as a result, the odds ratios and associated p-values will be estimated.

Results

The distribution of Gram-positive bacteria based on multiple parameters in urinary tract infections

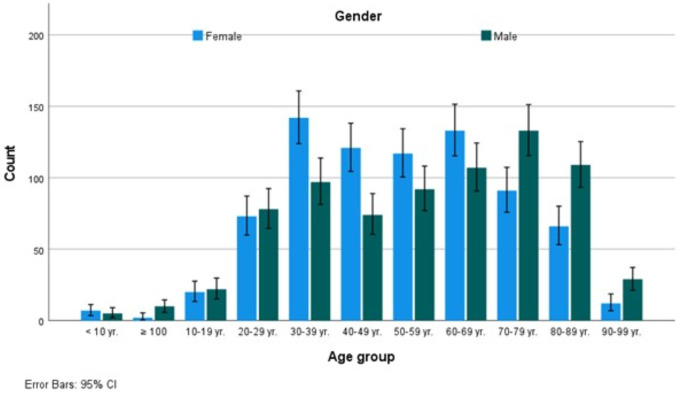

Table 1 provides an overview of the findings of our investigation about the gram-positive bacteria isolated from urinary tract infections. It shows the distribution according to different variables. The distribution of gram-positive bacteria in four years showed a consistent prevalence (p > 0.05), similarly, gender has shown a significant difference, with females at 784 (50.9%) and males at 756 (49.1%). Age groups have shown a tendency to increase in the Middle Ages, from 20–29 years old to 80–89 years old (Fig 1). The source of samples, and hence the infection, was mainly OPD, accounting for 1043 (67.7%) compared to 456 (29.6%) (p < 0.05).

Table 1. Distribution of gram-positive bacteria isolated from urinary tract infections according to year, gender, age group, and source of sample.

| Criteria | Total | Beta-hemolytic streptococci | Enterococcus casseliflavus | Enterococcus faecalis | Enterococcus faecium | Enterococcus gallinarum | Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus | Staphylococcus aureus | Streptococcus sp. | Streptococcus agalactiae | Streptococcus bovis | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| Year | 2019 | 476 | 30.9 | 53 | 41.1% | 1 | 100.0% | 201 | 29.2% | 53 | 26.8% | 1 | 33.3% | 14 | 50.0% | 51 | 22.0% | 32 | 34.8% | 70 | 41.7% | 0 | 0.0% |

| 2020 | 314 | 20.4 | 30 | 23.3% | 0 | 0.0% | 131 | 19.0% | 44 | 22.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 9 | 32.1% | 42 | 18.1% | 49 | 53.3% | 9 | 5.4% | 0 | 0.0% | |

| 2021 | 443 | 28.8 | 40 | 31.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 217 | 31.5% | 67 | 33.8% | 1 | 33.3% | 0 | 0.0% | 77 | 33.2% | 11 | 12.0% | 29 | 17.3% | 1 | 100.0% | |

| 2022 | 307 | 19.9 | 6 | 4.7% | 0 | 0.0% | 139 | 20.2% | 34 | 17.2% | 1 | 33.3% | 5 | 17.9% | 62 | 26.7% | 0 | 0.0% | 60 | 35.7% | 0 | 0.0% | |

| Gender | Female | 784 | 50.9 | 84 | 65.1% | 0 | 0.0% | 332 | 48.3% | 105 | 53.0% | 1 | 33.3% | 10 | 35.7% | 85 | 36.6% | 65 | 70.7% | 101 | 60.1% | 1 | 100.0% |

| Male | 756 | 49.1 | 45 | 34.9% | 1 | 100.0% | 356 | 51.7% | 93 | 47.0% | 2 | 66.7% | 18 | 64.3% | 147 | 63.4% | 27 | 29.3% | 67 | 39.9% | 0 | 0.0% | |

| Age group | < 10 yr. | 12 | 0.8 | 1 | 0.8% | 0 | 0.0% | 6 | 0.9% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 4 | 1.7% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 0.6% | 0 | 0.0% |

| ≥ 100 | 12 | 0.8 | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 6 | 0.9% | 3 | 1.5% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 3.6% | 2 | 0.9% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | |

| 10-19 yr. | 42 | 2.7 | 5 | 3.9% | 0 | 0.0% | 12 | 1.7% | 6 | 3.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 3 | 10.7% | 9 | 3.9% | 2 | 2.2% | 5 | 3.0% | 0 | 0.0% | |

| 20-29 yr. | 151 | 9.8 | 9 | 7.0% | 1 | 100.0% | 64 | 9.3% | 20 | 10.1% | 0 | 0.0% | 3 | 10.7% | 26 | 11.2% | 16 | 17.4% | 12 | 7.1% | 0 | 0.0% | |

| 30-39 yr. | 239 | 15.5 | 25 | 19.4% | 0 | 0.0% | 107 | 15.6% | 19 | 9.6% | 0 | 0.0% | 7 | 25.0% | 36 | 15.5% | 21 | 22.8% | 24 | 14.3% | 0 | 0.0% | |

| 40-49 yr. | 195 | 12.7 | 23 | 17.8% | 0 | 0.0% | 75 | 10.9% | 15 | 7.6% | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 7.1% | 26 | 11.2% | 18 | 19.6% | 36 | 21.4% | 0 | 0.0% | |

| 50-59 yr. | 209 | 13.6 | 25 | 19.4% | 0 | 0.0% | 75 | 10.9% | 23 | 11.6% | 2 | 66.7% | 3 | 10.7% | 35 | 15.1% | 11 | 12.0% | 35 | 20.8% | 0 | 0.0% | |

| 60-69 yr. | 240 | 15.6 | 23 | 17.8% | 0 | 0.0% | 89 | 12.9% | 38 | 19.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 4 | 14.3% | 35 | 15.1% | 16 | 17.4% | 34 | 20.2% | 1 | 100.0% | |

| 70-79 yr. | 224 | 14.5 | 12 | 9.3% | 0 | 0.0% | 123 | 17.9% | 39 | 19.7% | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 7.1% | 25 | 10.8% | 7 | 7.6% | 16 | 9.5% | 0 | 0.0% | |

| 80-89 yr. | 175 | 11.4 | 4 | 3.1% | 0 | 0.0% | 109 | 15.8% | 24 | 12.1% | 1 | 33.3% | 3 | 10.7% | 30 | 12.9% | 1 | 1.1% | 3 | 1.8% | 0 | 0.0% | |

| 90-99 yr. | 41 | 2.7 | 2 | 1.6% | 0 | 0.0% | 22 | 3.2% | 11 | 5.6% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 4 | 1.7% | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 1.2% | 0 | 0.0% | |

| Source | EMR | 9 | 0.6 | 1 | 0.8% | 0 | 0.0% | 5 | 0.7% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 0.9% | 1 | 1.1% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% |

| EXT | 32 | 2.1 | 5 | 3.9% | 0 | 0.0% | 12 | 1.7% | 2 | 1.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 3.6% | 4 | 1.7% | 5 | 5.4% | 3 | 1.8% | 0 | 0.0% | |

| INP | 456 | 29.6 | 11 | 8.5% | 0 | 0.0% | 232 | 33.7% | 133 | 67.2% | 1 | 33.3% | 10 | 35.7% | 51 | 22.0% | 7 | 7.6% | 11 | 6.5% | 0 | 0.0% | |

| OPD | 1043 | 67.7 | 112 | 86.8% | 1 | 100.0% | 439 | 63.8% | 63 | 31.8% | 2 | 66.7% | 17 | 60.7% | 175 | 75.4% | 79 | 85.9% | 154 | 91.7% | 1 | 100.0% | |

Fig 1. Age-specific distribution of gram-positive bacteria that cause urinary tract infections in females and males. Bars represent the standard error.

Prevalence of gram-positive bacteria according to criteria

The prevalence over the four years showed persistent patterns (p > 0.05) effecting gender, age groups, and whether the source of the sample whether an outpatient department or inpatient.

Dominant gram-positives species

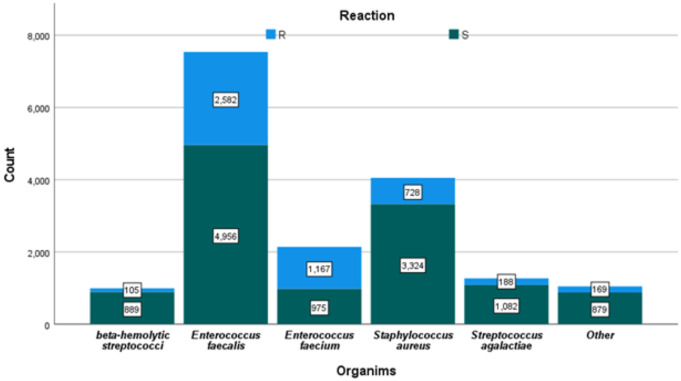

The dominant gram-positives species Enterococcus faecalis (44.7%), Staphylococcus aureus (15.1%), Enterococcus faecium (12.9%), Streptococcus agalactiae (10.9%), beta-hemolytic streptococci (8.4%), Streptococcus sp. (6.0%), Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (1.8%), Enterococcus gallinarum (0.2%), Enterococcus casseliflavus (0.1%), and Streptococcus bovis (0.1%) (Fig 2).

Fig 2. Major gram-positive bacterial counts and their corresponding susceptibility and resistance numbers (S = sensitive and R = Resistant).

Common resistance to antibiotics

The susceptibility of the studied bacteria to all tested antimicrobial agents is shown in Table 2. The 1540 isolates showed an overall susceptibility of 71.0%, compared to a resistance of 29.0%. The most common resistance was to erythromycin (75.7%), followed by cefotaxime (73.9%), tetracycline (70.5%), ciprofloxacin (54.3%), and Synercid (53.6%). The remaining antimicrobials revealed resistance rates of less than 50% (Table 2).

Table 2. Susceptibility of gram-positive bacteria to antimicrobial agents.

| Beta-hemolytic streptococci | Enterococcus casseliflavus | Enterococcus faecalis | Enterococcus faecium | Enterococcus gallinarum | Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus | Staphylococcus aureus | Streptococcus sp. | Streptococcus agalactiae | Streptococcus bovis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Column N % | Column N % | Column N % | Column N % | Column N % | Column N % | Column N % | Column N % | Column N % | Column N % | ||

| Amox/ K Clav | R | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 100% | 6.9% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| S | 100.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 93.1% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | |

| Fosfomycin | R | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 9.5% | 6.7% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| S | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 90.5% | 93.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | |

| Nitrofurantoin | R | 0.0% | 0.0% | 5.6% | 43.2% | 0.0% | 4.8% | 1.0% | 0.0% | 2.3% | 0.0% |

| S | 100.0% | 100.0% | 94.4% | 56.8% | 0.0% | 95.2% | 99.0% | 100.0% | 97.7% | 0.0% | |

| Trimeth/ Sulfa | R | 0.0% | 0.0% | 93.3% | 100.0% | 0.0% | 21.4% | 10.2% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| S | 0.0% | 0.0% | 6.7% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 78.6% | 89.8% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | |

| Amikacin | R | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 50.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| S | 0.0% | 0.0% | 100.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 50.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | |

| Amoxicillin | R | 14.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| S | 85.7% | 0.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 0.0% | |

| Ampicillin | R | 0.0% | 0.0% | 11.4% | 78.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 65.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| S | 100.0% | 100.0% | 88.6% | 22.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 35.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | |

| Azithromycin | R | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 56.3% | 37.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| S | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 43.8% | 62.7% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | |

| Cefepime | R | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| S | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 0.0% | |

| Cefotaxime | R | 0.0% | 0.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| S | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 0.0% | |

| Cefoxitin | R | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 40.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| S | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 60.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | |

| Cephalothin | R | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 100.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| S | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 100.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | |

| Chloramphenicol | R | 0.0% | 0.0% | 13.8% | 25.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| S | 0.0% | 0.0% | 86.2% | 75.0% | 0.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | |

| Ciprofloxacin | R | 0.0% | 0.0% | 53.9% | 83.6% | 100.0% | 45.0% | 34.6% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| S | 100.0% | 100.0% | 46.1% | 16.4% | 0.0% | 55.0% | 65.4% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | |

| Clarithromycin | R | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 33.3% | 20.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| S | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 66.7% | 80.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | |

| Clindamycin | R | 30.8% | 0.0% | 95.7% | 100.0% | 0.0% | 22.2% | 19.0% | 16.7% | 59.1% | 0.0% |

| S | 69.2% | 0.0% | 4.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 77.8% | 81.0% | 83.3% | 40.9% | 100.0% | |

| Daptomycin | R | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| S | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | |

| Erythromycin | R | 45.5% | 0.0% | 87.1% | 90.1% | 50.0% | 50.0% | 37.0% | 50.0% | 78.6% | 0.0% |

| S | 54.5% | 0.0% | 12.9% | 9.9% | 50.0% | 50.0% | 63.0% | 50.0% | 21.4% | 0.0% | |

| Fusidc Acid | R | 0.0% | 0.0% | 100.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 28.6% | 23.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| S | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 71.4% | 77.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | |

| Gent.Synergy | R | 50.0% | 0.0% | 47.1% | 45.9% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| S | 50.0% | 0.0% | 52.9% | 54.1% | 100.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | |

| Gentamicin | R | 0.0% | 0.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 0.0% | 7.4% | 14.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| S | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 92.6% | 85.7% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | |

| Imipenem | R | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 100.0% | 7.6% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| S | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 92.4% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | |

| Inducible Clindamycin | R | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 100.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| S | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | |

| Levofloxacin | R | 4.1% | 0.0% | 50.8% | 84.7% | 100.0% | 46.4% | 32.9% | 9.1% | 6.5% | 0.0% |

| S | 95.9% | 100.0% | 49.2% | 15.3% | 0.0% | 53.6% | 67.1% | 90.9% | 93.5% | 100.0% | |

| Linezolid | R | 0.0% | 0.0% | 2.9% | 4.2% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 4.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| S | 100.0% | 100.0% | 97.1% | 95.8% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 96.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | |

| Meropenem | R | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| S | 100.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 100.0% | 0.0% | |

| Moxifloxacin | R | 14.3% | 0.0% | 25.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 44.4% | 28.9% | 0.0% | 10.8% | 0.0% |

| S | 85.7% | 0.0% | 75.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 55.6% | 71.1% | 100.0% | 89.2% | 0.0% | |

| Mupirocin | R | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 5.9% | 4.5% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| S | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 94.1% | 95.5% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | |

| Netilmicin | R | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 10.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| S | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 100.0% | 90.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | |

| Norfloxacin | R | 0.0% | 0.0% | 33.3% | 100.0% | 0.0% | 50.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| S | 0.0% | 0.0% | 66.7% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 50.0% | 100.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | |

| Oxacillin | R | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 100.0% | 41.6% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| S | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 58.4% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | |

| Penicillin | R | 0.0% | 0.0% | 16.8% | 81.5% | 66.7% | 100.0% | 90.6% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| S | 100.0% | 100.0% | 83.2% | 18.5% | 33.3% | 0.0% | 9.4% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | |

| Rifampin | R | 0.0% | 0.0% | 27.8% | 82.5% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 3.8% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| S | 0.0% | 100.0% | 72.2% | 17.5% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 96.2% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | |

| Strep.Synergy | R | 0.0% | 0.0% | 50.0% | 20.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| S | 0.0% | 0.0% | 50.0% | 80.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | |

| Synercid | R | 0.0% | 0.0% | 92.6% | 30.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 6.2% | 0.0% | 2.9% | 0.0% |

| S | 100.0% | 0.0% | 7.4% | 69.7% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 93.8% | 100.0% | 97.1% | 100.0% | |

| Teicoplanin | R | 0.0% | 0.0% | 5.9% | 42.7% | 33.3% | 3.6% | 2.4% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| S | 100.0% | 100.0% | 94.1% | 57.3% | 66.7% | 96.4% | 97.6% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | |

| Tetracycline | R | 91.2% | 0.0% | 88.6% | 60.5% | 33.3% | 25.0% | 18.8% | 100.0% | 77.2% | 100.0% |

| S | 8.8% | 100.0% | 11.4% | 39.5% | 66.7% | 75.0% | 81.2% | 0.0% | 22.8% | 0.0% | |

| Tigecycline | R | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| S | 100.0% | 0.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 0.0% | |

| Tobramycin | R | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 14.3% | 19.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| S | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 85.7% | 81.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | |

| Vancomycin | R | 0.8% | 0.0% | 2.7% | 37.9% | 33.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| S | 99.2% | 100.0% | 97.3% | 62.1% | 66.7% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | |

| Without antibiotics | R | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| S | 100.0% | 0.0% | 100.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 100.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

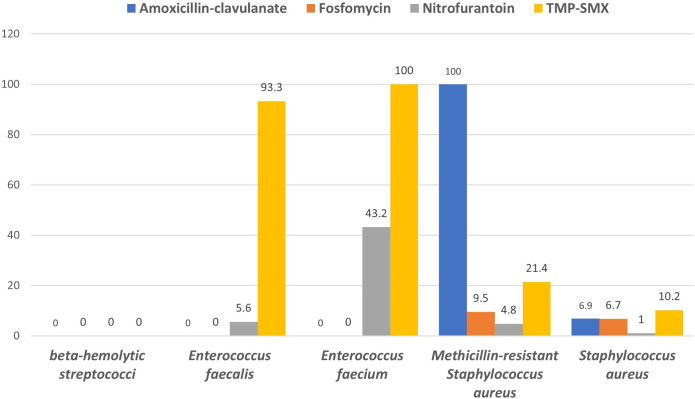

Resistance rates of major gram-positive bacteria to commonly used as treatment agents for uncomplicated UTIs are shown in Fig 3.

Fig 3. Resistance rate (%) of major gram-positive bacteria to commonly used antimicrobial agents for uncomplicated UTIs.

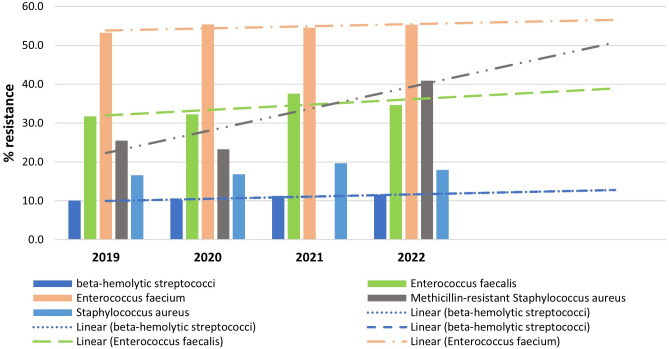

The direction of the prediction lines and the general antibiotic resistance of the major gram-positive bacteria are displayed in Fig 4. This prediction model indicates an increasing in the prevalence of resistance in MRSA and to a lesser extent with E. faecalis, E. faecium, and least is beta-hemolytic streptococci.

Fig 4. Overall resistance of the main gram-positive bacteria to antibiotics and orientation of the prediction lines.

Predictive model for infectivity by

Table 3 presents a predictive model for the infectivity of three urinary tract infection (UTI) organisms – Enterococcus faecalis, Enterococcus faecium, and GBS – based on a multiple logistic regression analysis of patient data from southern Saudi Arabia. The multivariate regression analysis did not detect any important risk factors associated with the causation and prevalence of UTI-causing organisms. The odds ratios (Exp(B) values) and their corresponding p-values did not present a statistically significant link between any of the demographic factors checked and the incidence of UTI-causing organisms.

Table 3. Predictive model for infectivity by the three major UTI organisms (E. faecalis, E. faecium, and GBS) recovered from patients in southern Saudi Arabia according to multiple logistic regression analysis.

| Organims* |

B |

Std. Error |

Wald |

df |

Sig. |

Exp (B) |

95% Confidence Interval for Exp(B) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |||||||

| Beta-hemolytic streptococci | ||||||||

| Intercept | 28.893 | 1595.325 | 0.000 | 1 | 0.986 | |||

| [Gender=1] | −12.337 | 712.044 | 0.000 | 1 | 0.986 | E | 0.000 | .b |

| [Gender=2] | 0c | 0 | ||||||

| [Age=1] | 0.896 | 9400.602 | 0.000 | 1 | 1.000 | 2.450 | 0.000 | .b |

| [Age=2] | −13.731 | 8649.744 | 0.000 | 1 | 0.999 | E | 0.000 | .b |

| [Age=3] | 1.397 | 4859.505 | 0.000 | 1 | 1.000 | 4.043 | 0.000 | .b |

| [Age=4] | 0.696 | 2876.406 | 0.000 | 1 | 1.000 | 2.007 | 0.000 | .b |

| [Age=5] | 1.412 | 2412.735 | 0.000 | 1 | 1.000 | 4.105 | 0.000 | .b |

| [Age=6] | 1.480 | 1.038 | 2.033 | 1 | 0.154 | 4.394 | 0.574 | 33.619 |

| [Age=7] | 1.446 | 1.036 | 1.949 | 1 | 0.163 | 4.247 | 0.557 | 32.361 |

| [Age=8] | −13.924 | 1427.606 | 0.000 | 1 | 0.992 | E | 0.000 | .b |

| [Age=9] | 0.097 | 2364.515 | 0.000 | 1 | 1.000 | 1.102 | 0.000 | .b |

| [Age=10] | −0.844 | 2588.550 | 0.000 | 1 | 1.000 | 0.430 | 0.000 | .b |

| [Age=11] | 0c | 0 | ||||||

| [Source=1] | 13.738 | 6284.871 | 0.000 | 1 | 0.998 | E | 0.000 | .b |

| [Source=2] | 1.401 | 4003.322 | 0.000 | 1 | 1.000 | 4.060 | 0.000 | .b |

| [Source=3] | 11.021 | 882.936 | 0.000 | 1 | 0.990 | E | 0.000 | .b |

| [Source=4] | 0c | 0 | ||||||

| Enterococcus faecalis | ||||||||

| Intercept | 31.168 | 1595.325 | 0.000 | 1 | 0.984 | |||

| [Gender=1] | −12.857 | 712.044 | 0.000 | 1 | 0.986 | E | 0.000 | .b |

| [Gender=2] | 0c | 0 | ||||||

| [Age=1] | 0.988 | 9400.602 | 0.000 | 1 | 1.000 | 2.685 | 0.000 | .b |

| [Age=2] | −0.731 | 8601.793 | 0.000 | 1 | 1.000 | 0.482 | 0.000 | .b |

| [Age=3] | 0.092 | 4859.505 | 0.000 | 1 | 1.000 | 1.096 | 0.000 | .b |

| [Age=4] | 0.488 | 2876.406 | 0.000 | 1 | 1.000 | 1.630 | 0.000 | .b |

| [Age=5] | 0.713 | 2412.735 | 0.000 | 1 | 1.000 | 2.039 | 0.000 | .b |

| [Age=6] | 0.370 | 0.776 | 0.227 | 1 | 0.634 | 1.447 | 0.316 | 6.621 |

| [Age=7] | 0.339 | 0.775 | 0.192 | 1 | 0.661 | 1.404 | 0.307 | 6.411 |

| [Age=8] | −14.799 | 1427.606 | 0.000 | 1 | 0.992 | E | 0.000 | .b |

| [Age=9] | 0.022 | 2364.515 | 0.000 | 1 | 1.000 | 1.022 | 0.000 | .b |

| [Age=10] | 0.005 | 2588.550 | 0.000 | 1 | 1.000 | 1.005 | 0.000 | .b |

| [Age=11] | 0c | 0 | ||||||

| [Source=1] | 13.995 | 6284.871 | 0.000 | 1 | 0.998 | E | 0.000 | .b |

| [Source=2] | 0.556 | 4003.322 | 0.000 | 1 | 1.000 | 1.744 | 0.000 | .b |

| [Source=3] | 12.608 | 882.936 | 0.000 | 1 | 0.989 | E | 0.000 | .b |

| [Source=4] | 0c | 0 | ||||||

| Enterococcus faecium | ||||||||

| Intercept | 29.663 | 1595.325 | 0.000 | 1 | 0.985 | |||

| [Gender=1] | −12.552 | 712.044 | 0.000 | 1 | 0.986 | E | 0.000 | .b |

| [Gender=2] | 0c | 0 | ||||||

| [Age=1] | −13.092 | 9427.803 | 0.000 | 1 | 0.999 | E | 0.000 | .b |

| [Age=2] | −0.592 | 8601.793 | 0.000 | 1 | 1.000 | 0.553 | 0.000 | .b |

| [Age=3] | 0.156 | 4859.505 | 0.000 | 1 | 1.000 | 1.169 | 0.000 | .b |

| [Age=4] | 0.096 | 2876.406 | 0.000 | 1 | 1.000 | 1.101 | 0.000 | .b |

| [Age=5] | −0.321 | 2412.735 | 0.000 | 1 | 1.000 | 0.725 | 0.000 | .b |

| [Age=6] | −0.729 | 0.866 | 0.708 | 1 | 0.400 | 0.482 | 0.088 | 2.634 |

| [Age=7] | −0.156 | 0.850 | 0.034 | 1 | 0.855 | 0.856 | 0.162 | 4.527 |

| [Age=8] | −14.997 | 1427.606 | 0.000 | 1 | 0.992 | E | 0.000 | .b |

| [Age=9] | −0.591 | 2364.515 | 0.000 | 1 | 1.000 | 0.554 | 0.000 | .b |

| [Age=10] | −0.979 | 2588.550 | 0.000 | 1 | 1.000 | 0.376 | 0.000 | .b |

| [Age=11] | 0c | 0 | ||||||

| [Source=1] | 0.638 | 6342.719 | 0.000 | 1 | 1.000 | 1.893 | 0.000 | .b |

| [Source=2] | 0.969 | 4003.322 | 0.000 | 1 | 1.000 | 2.636 | 0.000 | .b |

| [Source=3] | 14.038 | 882.936 | 0.000 | 1 | 0.987 | E | 0.000 | .b |

| [Source=4] | 0c | 0 | ||||||

a. The reference category is: Streptococcus bovis.

b. Floating point overflow occurred while computing this statistic. Its value is therefore set to system missing.

c. This parameter is set to zero because it is redundant.

E. The value of Ex (B) is very high.

Discussion

The present study attracts attention to the high incidence and patterns of antibiotic resistance of Staphylococcus aureus and Enterococcus faecalis among the survived community. The result that E. faecalis be more than S. aureus is noteworthy because E. faecalis is known to be innately more resistant to a wide range of widely used antibiotics [24]. It is notably worrying to observe the high rates of resistance to antibiotics for example erythromycin, cefotaxime, and tetracycline. Their poorer susceptibility denotes that there are not much effective empirical treatment possibilities, even if they are often given antimicrobials. Our present prediction model likewise displays a worrying trend of increasing MRSA resistance, which makes treating these infections even more difficult. Significant resistance was also noticed in Enterococcus faecium, one more bacterium of clinical implication. This is important since infections caused by vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE) are hard to cure and have a bad prognosis [25].

The epidemiology of urinary tract infections (UTIs) in Saudi Arabia has revealed alarming results about antibiotic resistance that is in line our present finding and the worldwide trends [26]. Many studies have been done in the region which underlined the increasing occurrence of gram-positive bacteria, such as Enterococcus species, as causative agents of UTIs. For example, a retrospective analysis in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia observed that Enterococcus spp. accounted for up to 20% of UTI isolates [23]. The increasing global resistance and the trend towards gram-positive infections playing a larger role in UTIs highlight the need for improved surveillance and antimicrobial stewardship initiatives in Saudi Arabia and the Middle East as a whole. The growing prevalence of gram-positive bacteria, such as Enterococcus, as causative agents of UTIs in Saudi Arabia, along with the universal increase in antimicrobial resistance, underscores the need for improved surveillance and enhanced antimicrobial stewardship efforts in the area. In Jazan, the incidence of UTIs caused by bacteria resistant to antibiotics is notable. As stated by study from other districts, E. coli persists to be the common bacteria accountable for UTIs and has a seasonal display that requires further attention. Multi-drug-resistant organism comprised about 35% of documented cases, with ESBLs making up 30% of those cases [19].

Understanding the role of causative microorganisms and their antibiotic resistance patterns is crucial for developing effective treatments and improving patient outcomes. Continued research, surveillance, and comprehensive interventions are essential to address this growing public health threat [27]. The present study found that the dominant gram-positive bacteria isolated from urinary tract infections (UTIs) were Enterococcus faecalis, Staphylococcus aureus, and Enterococcus faecium. Flores-Mireles et al. [9] discussed the epidemiology of UTIs, including the common causative pathogens such as Enterococcus faecalis, Staphylococcus aureus, and Enterococcus faecium. Their findings are in line with our ranking Enterococcus faecalis as number one gram-positive bacteria in UTI causal agents. Other work provides supporting evidence for the conclusion that the dominant gram-positive bacteria isolated from urinary tract infections (UTIs) were Enterococcus faecalis, Staphylococcus aureus, and Enterococcus faecium [28]. Many other studies have reported that Enterococcus faecalis prevalence ranges from 16–26% [29–31].

The current study highlighted the rising problems with antibiotic resistance, especially with Enterococcus species, in the community under study in southern Saudi Arabia. According to the current results, erythromycin resistance was the most common antibiotic resistance next in decreasing order of prevalence was resistance to cefotaxime, tetracycline, ciprofloxacin, and Synercid. Less than 50% of the remaining antimicrobials showed signs of resistance. A study in 2023 examined antibiotic resistance trends in UTIs across the United States. The study found that resistance to commonly prescribed UTI antibiotics like trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and ciprofloxacin reached 25–30% nationwide by 2022. Worryingly, the researchers also identified increasing resistance to last-line therapies like nitrofurantoin and fosfomycin, reaching 10–15% in some regions [32].

Microorganisms are becoming increasingly resistant to antibiotics; this is a developing worldwide matter. This is produced by the abuse and misuse of antibiotics, which obliges bacteria to evolve and promotes the growth of resistant species [1]. The problem can be further aggravated as these resistant bacteria share their resistance make-ups through genetic exchange [33,34]. Thus, infections conveyed by microorganisms that have developed resistance become hard to treat. Patients will therefore demand further cost for medications, stay in the hospital longer, and have a greater possibility of complications and death. This increase in antibiotic resistance adding a substantial burden on international economies and healthcare systems [35].

The analysis’s findings in this study corroborate previous research in showing that UTI-causing organisms may not be principally determined by demographic factors. However, numerous demographic characters, such as age and sex, were linked to an increased incidence of UTIs, the influences were often trivial and unreliable across studies, as stated by a systematic study by Smith et al. [36]. Similarly, clinical and behavioral factors like sexual activity, antibiotic use, and underlying diseases were found to be greater predictors of UTI incidence than standard demographic characteristics [37].

These studies show up the complex, versatile etiology of UTIs. UTIs are caused by a dynamic communication between the pathogen, the host, and environmental factors that can vary from person to person [9].

The findings of prediction model in the current study showed rising resistance tendencies, this worrying and coherent with broader universal patterns of antimicrobial resistance, particularly for MRSA and to a lesser extent for Enterococcus species and beta-hemolytic streptococci. In the previous 20 years, reports have revealed that the occurrence of MRSA infections has risen in healthcare as well as in community settings [38,39]. The increasing resistance among beta-hemolytic streptococci, such as group A Streptococcus, has also been reported, further complicating treatment of severe invasive infections [40]. To fight these increases in resistance and assure inexpensive management of infections caused by these pathogens, continuing surveillance and the formation of state-of-the-art antimicrobial strategies will be important. With the use of this data, policymakers ought to urge the careful use of antibiotics to reduce the increase of resistant organisms and put in place strong mechanisms for infection prevention and control. Future research has a responsibility to investigate the causal means behind the registered resistance and create pioneering therapeutic strategies to combat the infections that are difficult to manage.

Conclusions

This study highlights the importance of gram-positive bacteria as causative pathogens of UTIs and describes antibiotic resistance in southern Saudi Arabia. Increasing resistance in MRSA is a big concern. Continuous monitoring of antibiotic susceptibility is essential to guide empirical treatment. Follow-up on resistance is so important to guide antibiotics stewardship and lower the cost and patient’s hospitalization.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their appreciation to Aseer Central hospital for their support.

Data Availability

Data are all contained within the manuscript.

Funding Statement

Deanship of Scientific Research at King Khalid University for funding this work through large group research project under the grant number RGP2/570/45.

References

- 1.Murray CJ, Ikuta KS, Sharara F, Swetschinski L, Robles Aguilar G, Gray A, et al.; Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2022;399(10325):629–55. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02724-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abbasi Montazeri E, Khosravi AD, Saki M, Sirous M, Keikhaei B, Seyed-Mohammadi S. Prevalence of Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae Causing Bloodstream Infections in Cancer Patients from Southwest of Iran. Infect Drug Resist. 2020;13:1319–26. doi: 10.2147/idr.s254357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chinemerem Nwobodo D, Ugwu MC, Oliseloke Anie C, Al-Ouqaili MTS, Chinedu Ikem J, Victor Chigozie U, et al. Antibiotic resistance: The challenges and some emerging strategies for tackling a global menace. J Clin Lab Anal. 2022;36(9):e24655. doi: 10.1002/jcla.24655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hussein RA, AL-Kubaisy SH, Al-Ouqaili MTS. The influence of efflux pump, outer membrane permeability and β-lactamase production on the resistance profile of multi, extensively and pandrug resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Infect Public Health. 2024;17(11):102544. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2024.102544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andersson DI, Hughes D. Persistence of antibiotic resistance in bacterial populations. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2011;35(5):901–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2011.00289.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shankar Pr. Book review: Tackling drug-resistant infections globally. Arch Pharma Pract. 2016;7(3):110. doi: 10.4103/2045-080x.186181 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salam MA, Al-Amin MY, Salam MT, Pawar JS, Akhter N, Rabaan AA, et al. Antimicrobial Resistance: A Growing Serious Threat for Global Public Health. Healthcare (Basel). 2023;11(13):1946. doi: 10.3390/healthcare11131946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abalkhail A, AlYami AS, Alrashedi SF, Almushayqih KM, Alslamah T, Alsalamah YA, et al. The Prevalence of Multidrug-Resistant Escherichia coli Producing ESBL among Male and Female Patients with Urinary Tract Infections in Riyadh Region, Saudi Arabia. Healthcare (Basel). 2022;10(9):1778. doi: 10.3390/healthcare10091778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flores-Mireles AL, Walker JN, Caparon M, Hultgren SJ. Urinary tract infections: epidemiology, mechanisms of infection and treatment options. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2015;13(5):269–84. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gupta K, Hooton TM, Stamm WE. Increasing antimicrobial resistance and the management of uncomplicated community-acquired urinary tract infections. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135(1):41–50. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-1-200107030-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gajdács M, Ábrók M, Lázár A, Burián K. Increasing relevance of Gram-positive cocci in urinary tract infections: a 10-year analysis of their prevalence and resistance trends. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):17658. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-74834-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hooton TM. Clinical practice. Uncomplicated urinary tract infection. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(11):1028–37. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1104429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Foxman B. Urinary tract infection syndromes: occurrence, recurrence, bacteriology, risk factors, and disease burden. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2014;28(1):1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2013.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmiemann G, Kniehl E, Gebhardt K, Matejczyk MM, Hummers-Pradier E. The diagnosis of urinary tract infection: a systematic review. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2010;107: 361–367. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2010.0361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al Mijalli SH. Bacterial Uropathogens in Urinary Tract Infection and Antibiotic Susceptibility Pattern in Riyadh Hospital, Saudi Arabia. Cell Mol Med. 2017;03(01). doi: 10.21767/2573-5365.100028 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Balkhi B, Mansy W, AlGhadeer S, Alnuaim A, Alshehri A, Somily A. Antimicrobial susceptibility of microorganisms causing Urinary Tract Infections in Saudi Arabia. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2018;12(4):220–7. doi: 10.3855/jidc.9517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aabed K, Moubayed N, Alzahrani S. Antimicrobial resistance patterns among different Escherichia coli isolates in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2021;28(7):3776–82. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2021.03.047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Al-Tawfiq JA. Changes in the pattern of hospital intravenous antimicrobial use in Saudi Arabia, 2006-2008. Ann Saudi Med. 2012;32(5):517–20. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2012.517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alhazmi AH, Alameer KM, Abuageelah BM, Alharbi RH, Mobarki M, Musawi S, et al. Epidemiology and Antimicrobial Resistance Patterns of Urinary Tract Infections: A Cross-Sectional Study from Southwestern Saudi Arabia. Medicina (Kaunas). 2023;59(8):1411. doi: 10.3390/medicina59081411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thabit AK, Alabbasi AY, Alnezary FS, Almasoudi IA. An Overview of Antimicrobial Resistance in Saudi Arabia (2013-2023) and the Need for National Surveillance. Microorganisms. 2023;11(8):2086. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms11082086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alamri A, Hamid ME, Abid M, Alwahhabi AM, Alqahtani KM, Alqarni MS, et al. Trend analysis of bacterial uropathogens and their susceptibility pattern: A 4-year (2013-2016) study from Aseer region, Saudi Arabia. Urol Ann. 2018;10(1):41–6. doi: 10.4103/UA.UA_68_17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alzohairy M. Frequency and Antibiotic Susceptibility Pattern of Uro-Pathogens Isolated from Community and Hospital-Acquired Infections in Saudi Arabia – A Prospective Case Study. J Adv Med Med Res. 2011;1(2):45–56. doi: 10.9734/bjmmr/2011/207 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alamri A, Hassan B, Hamid ME. Susceptibility of hospital-acquired uropathogens to first-line antimicrobial agents at a tertiary health-care hospital, Saudi Arabia. Urol Ann. 2021;13(2):166–70. doi: 10.4103/UA.UA_109_20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guan L, Beig M, Wang L, Navidifar T, Moradi S, Motallebi Tabaei F, et al. Global status of antimicrobial resistance in clinical Enterococcus faecalis isolates: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2024;23:1–16. doi: 10.1186/s12941-024-00728-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ahmed MO, Baptiste KE. Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococci: A Review of Antimicrobial Resistance Mechanisms and Perspectives of Human and Animal Health. Microb Drug Resist. 2018;24(5):590–606. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2017.0147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sula I, Alreshidi MA, Alnasr N, Hassaneen AM, Saquib N. Urinary Tract Infections in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, a Review. Microorganisms. 2023;11(4):952. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms11040952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prestinaci F, Pezzotti P, Pantosti A. Antimicrobial resistance: a global multifaceted phenomenon. Pathog Glob Health. 2015;109(7):309–18. doi: 10.1179/2047773215Y.0000000030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Najar MS, Saldanha CL, Banday KA. Approach to urinary tract infections. Indian J Nephrol. 2009;19(4):129–39. doi: 10.4103/0971-4065.59333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hall LM, Duke B, Urwin G, Guiney M. Epidemiology of Enterococcus faecalis urinary tract infection in a teaching hospital in London, United Kingdom. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30(8):1953–7. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.8.1953-1957.1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sharifi Y, Hasani A, Ghotaslou R, Naghili B, Aghazadeh M, Milani M, et al. Virulence and antimicrobial resistance in enterococci isolated from urinary tract infections. Adv Pharm Bull. 2013;3(1):197–201. doi: 10.5681/apb.2013.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Salm J, Salm F, Arendarski P, Kramer TS. High frequency of Enterococcus faecalis detected in urinary tract infections in male outpatients – a retrospective, multicenter analysis, Germany 2015 to 2020. BMC Infect Dis. 2023;23:1–7. doi: 10.1186/S12879-023-08824-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mareș C, Petca R-C, Popescu R-I, Petca A, Mulțescu R, Bulai CA, et al. Update on Urinary Tract Infection Antibiotic Resistance-A Retrospective Study in Females in Conjunction with Clinical Data. Life (Basel). 2024;14(1):106. doi: 10.3390/life14010106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Laxminarayan R, Duse A, Wattal C, Zaidi AKM, Wertheim HFL, Sumpradit N, et al. Antibiotic resistance-the need for global solutions. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13(12):1057–98. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70318-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Owaid HA, Al-Ouqaili MTS. Molecular characterization and genome sequencing of selected highly resistant clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and its association with the clustered regularly interspaced palindromic repeat/Cas system. Heliyon. 2025;11(1):e41670. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2025.e41670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.O’Neill J. Tackling drug-resistant infections globally: final report and recommendations. 2016.

- 36.Smith AL, Brown J, Wyman JF, Berry A, Newman DK, Stapleton AE. Treatment and Prevention of Recurrent Lower Urinary Tract Infections in Women: A Rapid Review with Practice Recommendations. J Urol. 2018;200(6):1174–91. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2018.04.088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.He Y, Zhao J, Wang L, Han C, Yan R, Zhu P, et al. Epidemiological trends and predictions of urinary tract infections in the global burden of disease study 2021. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):4702. doi: 10.1038/s41598-025-89240-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Deurenberg RH, Stobberingh EE. The evolution of Staphylococcus aureus. Infect Genet Evol. 2008;8(6):747–63. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2008.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chambers HF, Deleo FR. Waves of resistance: Staphylococcus aureus in the antibiotic era. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7(9):629–41. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lamagni T, Guy R, Chand M, Henderson KL, Chalker V, Lewis J, et al. Resurgence of scarlet fever in England, 2014-16: a population-based surveillance study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18(2):180–7. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30693-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data are all contained within the manuscript.