Abstract

Despite the widespread use of fluconazole (FLC) in treating Candida infections, the emergence of drug resistance has become an increasing concern. Our earlier studies showing synergism between minocycline (Min) and azoles were limited by Min’s high required concentrations exceeding clinically achievable plasma levels. To overcome this limitation, we engineered novel bovine serum albumin (BSA)-encapsulated minocycline nanoparticles (Min-NPs). Then we evaluated the physicochemical properties such as size, potential, particle stability, drug loading and toxicity to make sure their efficacy and safety. Using checkerboard dilution assays, we demonstrated that Min-NPs significantly enhanced azole activity against Candida species at substantially lower Min concentrations than previously required. For C. albicans and N. glabrata, under a certain concentration of FLC, the concentration of Min-NPs required to reach 50% MIC is less than 4 µg/mL. When tested in a murine model of systemic candidiasis, Min-NPs combined with FLC showed superior therapeutic efficacy compared to conventional Min and FLC combinations. In summary, the modification of this formulation can enhance the synergistic efficacy of Min, thereby enabling its potential application as an adjunctive therapy for drug-resistant Candida infections. Clinical trial number. Not applicable.

Keywords: Minocycline, Albumin nanoparticles, Fluconazole, Synergistic effect, Candida spp

Introduction

The global burden of fungal infections, particularly those caused by Candida species, has risen dramatically over the past decade, presenting significant challenges to healthcare systems worldwide [1, 2]. While Candida albicans remains the predominant pathogenic species [3], these infections range from superficial mucosal manifestations to severe systemic infections with mortality rates exceeding 40% in immunocompromised patients [4, 5]. Fluconazole (FLC) has emerged as the frontline treatment for candidiasis, owing to its broad antifungal spectrum, favorable safety profile, and excellent bioavailability [6]. However, its fungistatic mechanism of action [7, 8] necessitates prolonged high-dose regimens (400–800 mg/d) for treating invasive infections. This therapeutic approach has contributed to the widespread emergence of drug-resistant Candida strains, compromising treatment efficacy [9, 10].

To address the growing challenge of antifungal resistance, innovative combination therapies have emerged as promising strategies to restore drug susceptibility in resistant Candida strains [11–13]. Our previous investigations revealed that minocycline (Min), a second-generation tetracycline antibiotic, significantly potentiates the antifungal activity of FLC against azole-resistant Candida species [14]. This synergistic effect extends beyond Candida, showing promise against other clinically relevant fungi including Aspergillus fumigatus and Fusarium species, which typically exhibit high minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) for azoles [15]. However, the clinical application of this promising combination faces a significant hurdle: Min’s limited bioavailability [16]. Current therapeutic protocols restrict oral and intravenous Min administration to 200 mg/d, achieving peak tissue concentrations (Cmax) of only 3.1–4.1 µg/mL [17] - substantially below the levels required for optimal synergistic interaction with azoles.

Recent advances in nanotechnology have spawned various innovative drug delivery systems to overcome Min’s bioavailability limitations, including Min-polyethylene glycosylated poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) nanoparticles (NPs) and nanoliposomal formulations for targeted ocular delivery [18, 19]. Among these emerging platforms, albumin-based NPs have garnered particular attention due to their exceptional drug loading capacity, robust stability, and superior biocompatibility [20–22]. Specifically, bovine serum albumin (BSA) has emerged as an ideal protein scaffold for developing sophisticated nanocarriers [23]. Drawing from our successful experience with BSA-encapsulated amphotericin B nanoparticles [24], we hypothesized that encapsulating Min into BSA nanoparticles would enhance its bioavailability and potentiate its synergistic interaction with FLC, enabling effective treatment at clinically achievable concentrations.

Understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying the synergistic interaction between Min and FLC is paramount for optimizing clinical applications. Previous research has demonstrated that tetracycline-FLC combinations downregulate the expression of Cdr1, a crucial ATP-binding cassette efflux pump implicated in antifungal resistance [25, 26]. This transmembrane protein, characterized by dual transmembrane domains and nucleotide-binding domains (NBDs), facilitates drug efflux through ATP hydrolysis [27–29].

The present study aimed to elucidate whether Min modulates FLC activity through Cdr1-dependent mechanisms while exploring alternative regulatory pathways, including sphingolipid metabolism, ergosterol biosynthesis, and the target of rapamycin (TOR) signaling cascade [30]. We report the development of albumin-based Min nanoparticles designed to enhance the synergistic antifungal effects of FLC against resistant Candida species, validated through both in vitro and in vivo studies. Additionally, we present a comprehensive investigation of the molecular mechanisms underlying this therapeutic synergy.

Materials and methods

Materials

BSA and 2-morpholinoethanesulfonic acid (MES) were procured from Sigma-Aldrich Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China). Dithiothreitol (DTT) and sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) were obtained from Aladdin Bio-Chem Technology Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China). Min, itraconazole (ITC), and FLC were purchased from Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China). Voriconazole (VOR) and posaconazole (POS) were sourced from Solarbio Biotechnology Co., Ltd (Beijing, China). Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits for mouse alanine aminotransferase (ALT), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), and serum creatinine (CRE) were procured from Yuannuo Tiancheng Technology Co., Ltd (Chengdu, China).

Strain culture

Strains of azole-resistant Candida spp., including C. albicans (R3, R14, N175), Nakaseomyces glabrata (05448), and C. auris (AR383) from Shanghai Skin Disease Hospital, were studied. C. albicans SC5314 served as a quality control. All strains were incubated on Sabouraud dextrose agar (SDA) plates to obtain individual colonies at 35 °C.

Preparation and characterization of Min-NPs

Min-NPs were prepared using a method reported previously with slight modifications [31]. Initially, 120 mg BSA molecules were dissolved in double-distilled water (40 mg/mL, 3 mL) containing SDS (60 mg) and DTT (4.4 mg), and stirred at 180 rpm for 2 h at 90 °C. Subsequently, the activated solution (25 µL) was added to MES (0.1 M, pH 4.5, 1 mL) at 800 rpm for 4 h at 37 °C to obtain BSA-NPs. Min@BSA NPs were obtained by rapidly injecting Min solution (4 mg/mL, 25 µL) into BSA solution at 800 rpm and 37 °C for 4 h. Free Min molecules and other impurities were eliminated via thorough ultrafiltration (100 kDa). The morphology of Min-NPs/BSA-NPs was observed using a transmission electron microscope (Talos L120C, USA). The size value and zeta-potential of Min-NPs were measured using Zetasizer Nano (ZS90, England). Additionally, the stability of Min-NPs over 24 h at room temperature was investigated.

Loading efficiency (LE) and encapsulation efficiency (EE).

The LE and EE of Min were assessed using an ultraviolet-visible (UV-vis) spectrophotometer (Varian, USA) at 348 nm. The LE and EE at different ratios (BSA: Min) were calculated based on the following equations:

LE (%) = (Mass of loaded Min)/(Mass of Min-NPs) × 100%.

EE (%) = (Experimental LE)/(Theoretical LE) × 100%.

Determination of drug release in vitro

Min-NPs (2 mL) were introduced into a pre-treated dialysis bag and immersed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solution (pH 7.4, 100 mL) while being stirred at 150 rpm and maintained at 37 °C. At predetermined intervals (2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, and 24 h), 2 mL aliquots were withdrawn, and an equivalent volume of PBS solution was replenished. The content of released Min was quantified using a UV-vis spectrophotometer.

Cytotoxicity of Min-NPs

The in vitro cytotoxicity of Min-NPs against HEK 293 T cells was assessed via the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK8) assay. HEK 293 T cells (100 µL, 1 × 105 cells/mL) were seeded and cultured in 96-well plates at 37 °C with 5% CO2 overnight. Subsequently, different concentrations (35, 70, 140, 280 µg/mL) of drugs (Min, BSA and Min-NPs) were added to the plates and cultured for 24 h. CCK8 solution was added to the wells (10 µL/well), and absorbance was analyzed following 1 h of incubation using a Microplate Reader at 450 nm (ELx 800, USA). Untreated cells were considered controls.

Analysis of antifungal activity in vitro

A broth microdilution susceptibility test was conducted to determine the MICs of Min-NPs singularly or in combination with VOR, FLC, ITC, and POS against Candida spp. following Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) M27-A4 [32]. Fungal suspension was prepared from strains at 1 × 104 CFU/mL, and 100 µL of this suspension was seeded into a 96-well plate. Subsequently, 50 µL of serially diluted Min-NP solution (0.063–32 µg/mL) was added to the horizontal row of wells, whereas 50 µL of serially diluted VOR, FLC, ITC, or POS (0.125–64 µg/mL) was added to the horizontal row of the plate. Control groups included wells treated with Min-NPs, VOR, FLC, ITC, or POS alone. Wells with only fungal inoculum served as the growth control. The culture medium used was RPMI-1640, and Candida parapsilosis ATCC 22019 was used as the quality control strain. Following 24 h of incubation at 35 °C, MICs were determined based on the minimum drug concentration necessary to suppress 50% of fungal growth relative to the growth control. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Fractional inhibitory concentration index (FICI) was utilized to analyze the interaction between drugs [FICI = (MICA drug in combination/MICA alone + MICB drug in combination/MICB alone)]. Synergism was defined as FICI ≤ 0.5, indifference as 0.5 < FICI ≤ 4, and antagonism as FICI > 4.

Mouse systemic fungal infection model

Female BALB/c mice (6–8 weeks) were procured from Shanghai Jiesijie Biotechnology Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China). Following 1 week of adaptive feeding, the animals were randomly assigned to control or experimental groups (6 animals each). To establish a systemic fungal infection model, cyclophosphamide (100 mg/kg) was subcutaneously injected 1 and 4 days before fungal infection. For systemic fungal infection, 0.1 mL of C. albicans n175 (1 × 106 CFU/mL) was injected into the mice via the lateral tail vein. Min (10 mg/kg), FLC (32 mg/kg), Min (10 mg/kg) + FLC (32 mg/kg), Min-NPs (10 mg/kg), and Min-NPs (10 mg/kg) + FLC (32 mg/kg) were intraperitoneally administered once a day for 7 days to the experimental group. The control group include model groups (infected but did not receive drug treatment) and PBS groups (neither infected nor drug treated) received an equivalent volume of PBS. Mice weight and survival were monitored and recorded daily, and the mice were sacrificed 1 day after the last administration.

All animals were treated in a humane manner in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines, and anesthetics and sedatives were used to minimize animal distress and discomfort during the experimental process. Mice were anesthetized using 2,2,2-tribromoethanol (TBE) at a concentration of 1.25%, administered via intraperitoneal injection at a dosage of 0.2 mL per 10 g of body weight. Animals were monitored to ensure adequate anesthesia, as confirmed by the absence of response to toe pinch before proceeding with any interventions.

Antifungal effects and safety evaluation in vivo

At the end of the experiment, mice were euthanized using inhalational isoflurane anesthesia. The specific procedures were as follows: Animals were placed in an induction chamber pre-filled with 3–5% isoflurane vapor in oxygen. They remained in the chamber for several minutes until complete loss of consciousness was confirmed by absence of righting reflex and no response to toe pinch. Once animals were fully anesthetized and unconscious, euthanasia was completed by maintaining isoflurane exposure until respiratory and cardiac arrest occurred.

Blood was collected from the orbits of the mice, the serum levels of ALT, BUN, and CRE were evaluated using ELISA kits. The left kidney of the mice was extracted and homogenized in 1 mL PBS. The homogenized kidney was appropriately diluted and inoculated on SDA plates at 35 °C for 48 h. The colony forming unit (CFU) of kidneys was calculated using the following formula: CFU/g = (CFU count × diluted fold) × 10/tissue weight. The right kidney of the mouse was extracted and stained with hematoxylin–eosin (HE) to visualize the pathological change of the kidney and with periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) to visualize the fungal burden.

Deletion of C. albicans CDR1 and E-test

We used CRISPR-Cas9 technology to construct a C. albicans cdr1△/cdr1△ null mutant. The single-guide RNA (sgRNA) oligonucleotides were designed and ligated into the Cas9 plasmid (PV1393). We established a repair template and a double-stranded DNA fragment to induce appropriate mutation. A hybrid lithium acetate/electroporation protocol were used for the co-transformation of sgRNA plasmid and repair fragment into C. albicans strain SN152 [33]. The primers are shown in Table 1. Susceptibility testing of the wild strain and transformants displaying the expected mutations was performed against FLC (E-test®) with or without Min-NPs.

Table 1.

Primer for genes deletion

| Primer name | Primer sequence (5’−3’) |

|---|---|

| cdr1 sgRNA F | CGTAAACTATTTTTAATTTGAACCATAGCCAATAACAACAGTTTTAGAGCTAGAAATAGC |

| cdr1 sgRNA R | GCTATTTCTAGCTCTAAAACTGTTGTTATTGGCTATGGTTCAAATTAAAAATAGTTTACG |

| Repair template F | CCAACATACTTGGAGTTGGGATAACGAACCCAGTATAAATAACCATAGCCAATAACAACA |

| Repair template R | TTGGTGCTGTTTCAACATCTATTTCTGGTGCCATGACTCCTTAATAAGTGTTGTTATTGGCTATGGTTATTTAT |

| CDR1 F | TATGCCCTTTATCGTCCTTCAG |

| CDR1 R | GCTATGGTACCAACGGCAACTT |

Quantitative PCR (qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent from FLC-resistant C. albicans N175 treated with different drugs (C. albicans isolates were treated with 32 µg/ml Min-NPs, 8 µg/ml FLC alone, or 1 µg/ml Min-NPs and 8 µg/ml FLC; the control group was not treated). After 24 h of co-incubation with the drugs, RNA was extracted and reverse transcribed into cDNA via TransScript One-Step gDNA Removal and cDNA Synthesis SuperMix (TransGen Biotech, China). Table 2 presents the primer sequences used for the PCR of the test genes. Transcription levels of gene mRNA were analyzed using a lightcycler 96 fluorescent quantitative PCR (qRT-PCR) system (Roche, Switzerland). Specific primers and SYBR Premix Ex Taq (TaKaRa, Japan) were used using the following steps: 95 °C for 10 min, 95 °C for 15 s, 58 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 30 s, for 40 cycles. Relative gene expression was calculated using the 2−△△Ct method and the tubulin gene was used as an internal control. Three independent experiments were performed, with 8 replicates in each group.

Table 2.

List of qRT-PCR primer sequences analysis

| Gene name | Forward primer (5’−3’) | Reverse primer (5’−3’) |

|---|---|---|

| LCB1 | AATAACAAGACGGCAGTGA | AACGGAACCAGCAGTAAC |

| LCB2 | GTTAGGACCTGAAGGAAGAG | CGCCGAACTGACACATAA |

| LAG1 | ATCTCACAGCCAATCACTT | TCATCAGCAGAATCTTCACT |

| LAC1 | GGACTCCAGTTGTTATTGATAC | ACTTCCTCCTCCTCTTCTTC |

| AUR1 | GGTTACATACGCATCTTGG | TCGCCTTCTTCTTCTTCAT |

| RTG1 | AATACCGCAGGAGTAGGAA | CGTATAACCGATTCTGATTGG |

| RTG3 | TGTGAATAACGCCGACTC | CTGTTGTGGTTGTTGTTGT |

| PHO84 | TTCGGATGGACTCAAGTTAA | TCACCACCAATACCAATACC |

| SUR4 | CTGGTGGTTCATATCATTCC | CGGTTAATTGAGTGTAGCAT |

| FEN1 | AGCCGCTAGAGGTATAAGA | GCACAATCTCCACAATAAGG |

| IPT1 | GCATCTCTGGCTTGGTTAT | TGATCGTCATTGTCTTGGAA |

| ERG4 | CGGAAGGTCAATCTTGGAA | CAGTCATACGATGGTAATCAC |

| ERG6 | TGTCTCCAGTTCAATTAGCA | TACACCACAACCAACATCTA |

| ERG24 | GGTGACTGGTTGATTGGAT | GACGATGGATTAGCAAGGA |

| Tubulin | GTCTAACACTACTGCCATTG | TCACCTTCTTCCATACCTTC |

Statistical analysis

Comparison between groups was performed using the one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and post hoc tests. Survival curves were constructed using the Kaplan–Meier method. Differences were evaluated by performing the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. Data were analyzed using the GraphPad Prism version 8 and presented as the mean ± standard deviation (M ± SD). A P-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results and discussion

Preparation and characterization of Min-NPs

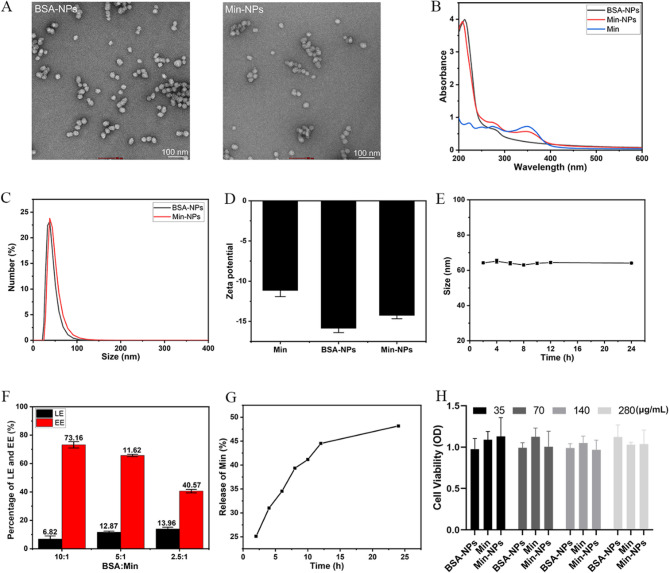

We employed BSA as a carrier system to develop Min-NPs with optimized antifungal properties. The synthesis process began with DTT pretreatment of BSA to break intramolecular disulfide bonds, exposing thiol groups that later enabled BSA molecule oxidation and intermolecular crosslinking. We then synthesized Min-NPs through BSA nano-assembly, utilizing the intermolecular disulfide network formation, adapting established protocols [24] with specific optimizations. Transmission electron microscopy revealed uniform spherical morphology for both BSA-NPs and Min-NPs (Fig. 1A). The size distribution and surface charge of the nanoparticles are depicted in Fig. 1C and D.

Fig. 1.

A TEM images of BSA-NPs and Min-NPs, Scale bar: 100 nm. B UV-Visible spectrophotometer of BSA-NPs, Min, and Min-NPs. C Particle size of BSA-NPs and Min-NPs. D Zeta potential of Min, BSA-NPs, and Min-NPs. E In vitro stability of Min-NPs for 24 h. F The drug-loading efficiency (LE) and encapsulation efficiency (EE) of Min in BSA of different mass ratios. G The cumulative release of Min-NPs in pH 7.4 PBS for 24 h in vitro. H Cell viability with different concentrations of Min-NPs (35, 70, 140 and 280 µg/mL). Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 3)

Successful drug incorporation was verified through UV spectroscopy, with Min-NPs displaying characteristic absorption peaks at 348 nm (Min) and 275 nm (BSA), as shown in Fig. 1B. The nanoparticles demonstrated excellent stability, maintaining consistent size distribution over 24 h at room temperature (25℃), indicating a robust nanostructure (Fig. 1E). Analysis of drug loading parameters revealed an inverse relationship between loading efficiency (LE) and encapsulation efficiency (EE) as Min content increased (Fig. 1F).

Release kinetics studies showed controlled drug delivery characteristics, with Min-NPs achieving 48.16% cumulative release over 24 h (Fig. 1G). We evaluated the biocompatibility of Min-NPs by exposing HEK 293 T cells to concentrations ranging from 35 to 280 µg/mL. Cell viability studies demonstrated excellent safety profiles, with cells maintaining approximately 100% viability even at the highest tested concentration (280 µg/mL), as shown in Fig. 1H.

The Min-NPs exhibited desirable characteristics, including uniform spherical morphology, stable size distribution, and sustained drug release profile. The high encapsulation efficiency and loading capacity demonstrate the potential of BSA as an effective carrier for Min delivery. The short-term colloidal stability over the 24-hour experimental period suggests their suitability for in vivo applications.

Nanoparticle drug delivery systems can be classified based on carrier properties. Albumin nanoparticles possess high drug loading capacity, enabling encapsulation of substantial drug payloads to enhance therapeutic efficacy [34]. The inherent stability of albumin molecules helps maintain drug integrity, preventing premature release and achieving controlled-release profiles. By modulating degradation rates through chemical modifications or physical crosslinking, precise temporal and dosage regulation of drug release can be realized. This capability lays the foundation for personalized medicine, maximizing therapeutic outcomes while minimizing side effects. As an ideal drug delivery system, albumin nanoparticles hold broad biomedical application potential [35]. Thus, We utilized BSA as a carrier, conjugated it with Min to construct Min-loaded nanoparticles, and ensured that the formulation modification did not compromise the drug’s safety.

Analysis of the antifungal activity in vitro

We employed checkerboard microdilution assays to evaluate the potential enhancement of azole antifungal activity by Min-NPs (Table 3). Synergistic effects were observed when combining Min-NPs with azoles against multiple Candida species (C. albicans, N. glabrata, and C. auris), resulting in reduced effective concentrations of azole drugs. The Min-NP formulation achieved synergistic effects at substantially lower concentrations compared to free Min (data from our previous study) [14], representing a significant improvement in drug efficiency. However, Min-NPs exhibited negligible antifungal activity when used alone, potentially because Min regulates the fungicidal properties of FLC via an unidentified mechanism. Our data is consistent with previous report which highlighted the potential of repurposing tetracyclines, such as Min and doxycycline, as antifungal agents against Candida species, particularly in the context of FLC resistance [36]. But their working concentration for Min and ranging from 4 to 427 µg/mL for Min and 128–512 µg/mL for doxycycline. Which also highlights the importance of improving Min delivery efficiency.

Table 3.

Antifungal activity of Min-NPs with Azoles against Candida species

| Species | No. | MICs (µg/mL)a | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agents alone | Combinationb | |||||||||

| Min-NPs | VOR | FLC | ITC | POS | VOR +Min-NPs |

FLC +Min-NPs |

ITC +Min-NPs |

POS +Min-NPs |

||

| C. albicans | R3 | >32 | 0.25 | 8 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.25/0.06(I) | 4/4(I) | 0.25/0.25(S) | 0.125/0.25(S) |

| R14 | 32 | 4 | 64 | 4 | 4 | 0.25/1(S) | 4/1(S) | 0.125/1(S) | 0.06/2(S) | |

| N175 | >32 | 0.5 | 8 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.25/0.06(I) | 4/0.06(I) | 0.25/0.25(I) | 0.25/0.06(I) | |

| N. glabrata | 05448 | >32 | 0.25 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 0.06/4(S) | 2/4(S) | 0.25/0.5(S) | 0.25/2(S) |

| C. auris | AR383 | >32 | 2 | >64 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5/16(S) | 64/8(I) | 0.125/8(S) | 0.25/4(S) |

aMinimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values are the concentrations that inhibited 50% of fungal growth

bFractional inhibitory concentration index (FICI) results are provided in parentheses. S, synergism (FICI ≤ 0.5); I, indifference (0.5 < FICI ≤ 4)

The synergistic effect observed between Min-NPs and various azoles, particularly FLC, against resistant Candida strains is noteworthy. The reduced effective concentration of azoles in combination with Min-NPs compared to free Min highlights the advantage of the nanoparticle formulation. This synergism could potentially allow for lower azole doses in clinical settings, mitigating side effects and reducing the risk of further resistance development.

Antifungal activity of Min-NPs combined with FLC in vivo

The protocol for establishing the systemic fungal infection mouse model and the administration strategies is schematically illustrated in Fig. 2A. Following C. albicans infection via tail vein injection, mice exhibited variable weight loss compared to uninfected PBS controls. All treatment regimens (FLC, Min, FLC + Min, Min-NPs, and FLC + Min-NPs) provided significant protection against infection-induced weight loss (Fig. 2B). The FLC + Min-NPs combination therapy demonstrated superior efficacy, achieving 66% survival at 12 days post-infection, while untreated controls succumbed to infection within 11 days (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

Antifungal activity of Min-NPs combined with FLC on the systemic fungal infection model. A The schematic illustration of the systemic fungal infection model and administration strategies, CTX: cyclophosphamide. B The body weight of the normal, model, FLC, Min, FLC + Min, Min-NPs, and FLC + Min-NPs groups (n = 6). C The survival rate of normal, model, FLC, Min, FLC + Min, Min-NPs, and FLC + Min-NPs group (n = 6). D The colony-forming units’ images of infected mice with different treatments (PBS, FLC, Min, FLC + Min, Min-NPs, FLC + Min-NPs). E The statistical analysis of fungal burden in different treatments (PBS, FLC, Min, FLC + Min, Min-NPs, FLC + Min-NPs) (n = 3). F The HE and PAS staining of kidney fungal burden of infected mice with different treatments (PBS, FLC, Min, FLC + Min, Min-NPs, FLC + Min-NPs. Scale bar is 100 μm. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001)

Upon completion of the treatment, the mice were euthanized and their kidneys were homogenized to determine the fungal burden using serial dilution on SDA plates. The CFUs for each group are shown in Fig. 2D, with quantitative analyses in Fig. 2E. Histopathological analysis using PAS staining corroborated the quantitative fungal burden results. Combination therapy with FLC + Min-NPs resulted in the most significant reduction in kidney fungal burden among all treatment groups (Fig. 2F). The fungal cell population, marked by the black rectangle, decreased across different treatment groups compared to the untreated model group. Notably, the kidney tissues of mice in the FLC combined with the Min-NPs group had significantly fewer fungi compared to other groups. This suggests that the addition of Min to NPs enhances the antifungal efficacy of FLC, probably due to the sustained release effect of NPs. Additionally, HE staining confirmed that the drugs were not toxic to the kidneys.

The superior therapeutic efficacy of Min-NPs combined with FLC in the murine model of systemic candidiasis is a significant finding. The improved survival rates, reduced fungal burden in kidneys, and decreased tissue damage observed in the combination therapy group underscore the potential clinical relevance of this approach. The ability of Min-NPs to enhance FLC activity in vivo without apparent toxicity is particularly promising.

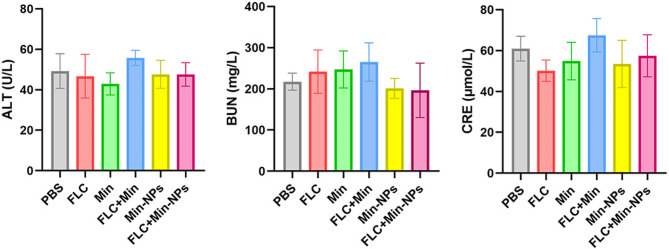

Safety evaluation of Min-NPs combined with FLC in vivo

We conducted comprehensive safety evaluations of all treatment regimens in mice with systemic candidiasis. Blood biochemical analyses were performed on serum samples from all treatment groups to assess potential systemic toxicity. Key biomarkers of organ function were measured, including ALT for liver function, and BUN and CRE for kidney function. While conventional treatments (FLC, Min, and FLC + Min) showed minor elevations in liver and kidney function markers, these changes remained within clinically acceptable ranges. Notably, both Min-NP formulations (alone and in combination with FLC) maintained organ function markers at baseline levels. Statistical analysis revealed no significant differences in biochemical parameters across all treatment groups (p > 0.05) (Fig. 3). The results suggests that BSA-NPs encapsulating Min do not negatively impact the liver and kidney function in mice. The lack of significant cytotoxicity in vitro and the absence of liver or kidney function abnormalities in vivo indicate a favorable safety profile for Min-NPs. This is crucial for potential clinical translation, as it addresses concerns about systemic toxicity often associated with antifungal therapies.

Fig. 3.

The liver and kidney function indices of fungal-infected mice after different administrations. ALT: alanine aminotransferase, BUN: serum urea nitrogen, CRE: creatinine

A previous study developed an albumin-based nanoparticle formulation of Min and conducted in vivo safety evaluation, which showed no significant toxicity in major organs, as evidenced by stable body weight, normal behavior, and absence of histopathological abnormalities [37]. We employed BSA as a carrier to prepare Min-loaded protein nanoparticles and further optimized the formulation conditions to ensure stable nanoparticle properties and absence of additional cytotoxicity. Subsequent in vitro antifungal activity assays demonstrated that the MICs of Min-loaded protein nanoparticles for reversing azole-resistant C. albicans and N. glabrata were below 4 µg/mL, which is achievable within clinical blood concentration ranges. In vivo experiments revealed that combination therapy with Min nanoparticles reduced mortality rates in mice, lowered renal fungal burden, and minimized tissue inflammatory damage, indicating effective in vivo application of the nanoparticles. Liver and kidney function tests in mice suggested safe in vivo application of the Min-loaded protein nanoparticles.

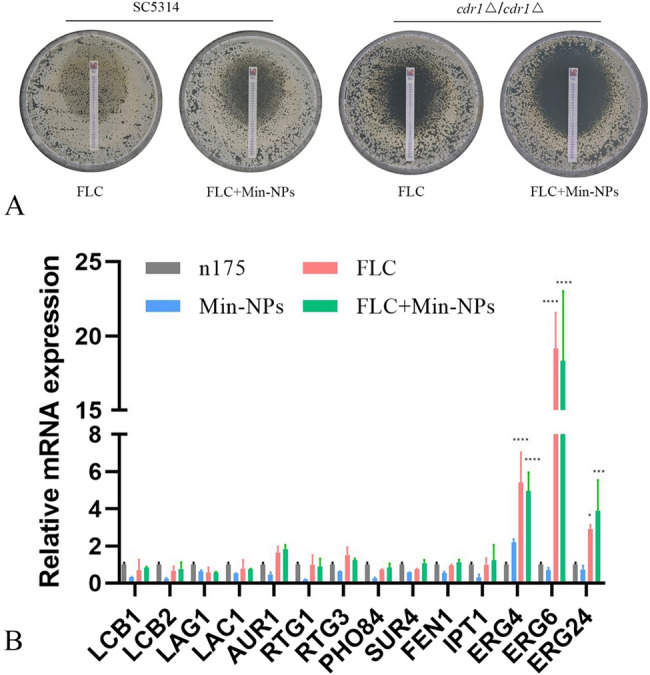

Synergistic mechanism of Min-NPs and FLC

The multidrug resistance protein CDR1, a lipid raft-associated transporter containing sphingolipids and ergosterol, plays a crucial role in C. albicans drug resistance. We initially hypothesized that Min-NPs might enhance FLC sensitivity through modulation of CDR1 expression. To investigate this mechanism, we generated and analyzed a CDR1-deficient strain (cdr1△/cdr1△) for Min-FLC synergy. As expected, CDR1 deletion enhanced FLC susceptibility, evidenced by larger inhibition zones in susceptibility testing (Fig. 4A). The FLC and Min-NP combination maintained synergistic activity against wild-type C. albicans (Fig. 4A). Unexpectedly, this synergistic effect was preserved in the CDR1-deficient strain, indicating that Min-NP-mediated FLC sensitization operates through CDR1-independent mechanisms.

Fig. 4.

Synergistic mechanism of Min-NPs and FLC against C. albicans. A The deletion of CDR1 did not influence the effect of FLC with Min-NPs. The sensitivities of C. albicans wild-type strain (SN152) and mutant (cdr1△/cdr1△) to FLC test strip and FLC test strip with Min-NPs. The concentration of Min-NPs was 16 µg/mL. B Gene expression in C. albicans after Min-NPs and FLC treatment. C. albicans isolates were treated with 32 µg/ml Min-NPs, 8 µg/ml FLC alone, or 1 µg/ml Min-NPs and 8 µg/ml FLC; the control group was not treated. Three independent experiments were performed, with 8 replicates in each group. Min-NPs suppressed the expression of RTG1, FEN1, and IPT1, whereas FLC did not affect these genes

The mechanism by which Min-NPs influence FLC activity remains unclear. Among the various factors, lipids are crucial contributors to drug resistance in human pathogenic Candida. Further investigation focused on expression profiling of key sphingolipid biosynthesis genes, including LCB1/LCB2 (serine palmitoyl transferase), LAG1/LAC1 (ceramide synthase), and AUR1 (inositol phosphoceramide synthetase 1) [38, 39]. Additionally, sphingolipid biosynthesis related genes include SUR4, FEN1, and IPT1; ergosterol biosynthesis related genes include ERG4, ERG6, ERG24; and TOR signaling pathway transcription factors including RTG1, RTG3, PHO84 [40, 41] were analyzed. Gene expression analysis revealed that Min-NPs specifically downregulated RTG1, FEN1, and IPT1, while FLC treatment showed no effect on these targets (Fig. 4B). These findings suggest that Min-NPs may exert their effects through dual inhibition of TOR signaling and sphingolipid biosynthesis pathways.

The persistence of synergistic effects in CDR1-deficient mutants indicates that the sensitization of Candida to FLC by Min-NPs likely involves mechanisms beyond the CDR1 efflux pump. The observed changes in gene expression related to sphingolipid synthesis, and TOR signaling pathways suggest a complex, multifaceted mechanism of action. This complexity could potentially contribute to a higher barrier against the development of resistance to the combination therapy.

Conclusion

We have developed and characterized an innovative BSA-based nanoparticle delivery system that significantly enhances FLC efficacy against drug-resistant Candida species. The demonstrated synergistic activity of Min-NPs with FLC, both in laboratory studies and animal models, combined with excellent safety characteristics, positions this formulation as a promising therapeutic strategy for clinical development. Despite these encouraging findings, several critical areas require additional research to fully validate this approach for clinical application. Long-term stability studies of Min-NPs, evaluation of their efficacy against a broader range of fungal species and clinical isolates, and more detailed pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic analyses would strengthen the findings. Additionally, exploring the potential for developing resistance to this combination therapy and investigating its efficacy in immunocompromised animal models would provide valuable insights for clinical application.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

JT Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Validation, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition, Resources, Project administration. MZ Visualization, Writing – review & editing. JW Investigation, Validation. ML Validation, Visualization. LG Data curation, Visualization. YL Data curation, Visualization. XW Resources, Conceptualization. LY Funding acquisition, Resources. LA Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Funding acquisition. XH Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Project administration. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 82102418 to Jingwen Tan, Grant No. 82173429 to Lianjuan Yang), Shanghai Municipal Health Commission (Grant No. 20224Y0372 to Lulu An).

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article. Access to raw data can be acquired by connecting to the corresponding author via email.

Declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

All experimental protocols related to animals have obtained approval from the Animal Ethics Committee of Shanghai Skin Disease Hospital, Tongji University School of Medicine, and were accomplished under the international rules for animal research.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Arastehfar A, Gabaldón T, Garcia-Rubio R, Jenks JD, Hoenigl M, Salzer HJF, Ilkit M, Lass-Flörl C, Perlin DS. Drug-resistant fungi: an emerging challenge threatening our limited antifungal armamentarium. Antibiot (Basel). 2020;9:877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li D, Li T, Bai C, Zhang Q, Li Z, Li X. A predictive nomogram for mortality of cancer patients with invasive candidiasis: a 10-year study in a cancer center of North China. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21:76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen M, Hu D, Li T, Zheng D, Liao W, Xia X, Cao C. The epidemiology and clinical characteristics of fungemia in a tertiary hospital in Southern china: a 6-year retrospective study. Mycopathologia. 2023;188:353–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arita GS, Faria DR, Sakita KM, Rodrigues-Vendramini FA, Capoci IR, Kioshima ES, Bonfim-Mendonça PS, Svidzinski TI. Impact of serial systemic infection on Candida albicans virulence factors. Future Microbiol. 2020;15:1249–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maiolo EM, Oliva A, Furustrand Tafin U, Perrotet N, Borens O, Trampuz A. Antifungal activity against planktonic and biofilm Candida albicans in an experimental model of foreign-body infection. J Infect. 2016;72:386–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Budani MC, Fensore S, Di Marzio M, Tiboni GM. Maternal use of fluconazole and congenital malformations in the progeny: a meta-analysis of the literature. Reprod Toxicol. 2021;100:42–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feng Y, Lu H, Whiteway M, Jiang Y. Understanding fluconazole tolerance in Candida albicans: implications for effective treatment of candidiasis and combating invasive fungal infections. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2023;35:314–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lu H, Shrivastava M, Whiteway M, Jiang Y. Candida albicans targets that potentially synergize with fluconazole. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2021;47:323–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li Z, Huang Y, Tu J, Yang W, Liu N, Wang W, Sheng C. Discovery of BRD4-HDAC dual inhibitors with improved fungal selectivity and potent synergistic antifungal activity against fluconazole-resistant Candida albicans. J Med Chem. 2023;66:5950–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pappas PG, Kauffman CA, Andes D, Benjamin DK Jr, Calandra TF, Edwards JE Jr, Filler SG, Fisher JF, Kullberg BJ, Ostrosky-Zeichner L, Reboli AC, Rex JH, Walsh TJ, Sobel JD. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of candidiasis: 2009 update by the infectious diseases society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:503–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Su LY, Ni GH, Liao YC, Su LQ, Li J, Li JS, Rao GX, Wang RR. Antifungal activity and potential mechanism of 6,7,4’-O-triacetylscutellarein combined with fluconazole against drug-resistant C. albicans. Front Microbiol. 2021;12:692693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.An L, Tan J, Wang Y, Liu S, Li Y, Yang L. Synergistic effect of the combination of deferoxamine and fluconazole in vitro and in vivo against fluconazole-resistant Candida spp. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2022;66:e0072522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khan MS, Ahmad I. Antibiofilm activity of certain phytocompounds and their synergy with fluconazole against Candida albicans biofilms. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67:618–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tan J, Jiang S, Tan L, Shi H, Yang L, Sun Y, Wang X. Antifungal activity of Minocycline and Azoles against fluconazole-resistant Candida species. Front Microbiol. 2021;12:649026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gao L, Sun Y, Yuan M, Li M, Zeng T. In vitro and in vivo Study on the synergistic effect of minocycline and azoles against pathogenic fungi. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2020;64:e00290-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shi W, Chen Z, Chen X, Cao L, Liu P, Sun S. The combination of Minocycline and fluconazole causes synergistic growth Inhibition against Candida albicans: an in vitro interaction of antifungal and antibacterial agents. FEMS Yeast Res. 2010;10:885–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Agwuh KN, MacGowan A. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the tetracyclines including glycylcyclines. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2006;58:256–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kashi TS, Eskandarion S, Esfandyari-Manesh M, Marashi SM, Samadi N, Fatemi SM, Atyabi F, Eshraghi S, Dinarvand R. Improved drug loading and antibacterial activity of minocycline-loaded PLGA nanoparticles prepared by solid/oil/water ion pairing method. Int J Nanomed. 2012;7:221–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaiser JM, Imai H, Haakenson JK, Brucklacher RM, Fox TE, Shanmugavelandy SS, Unrath KA, Pedersen MM, Dai P, Freeman WM, Bronson SK, Gardner TW, Kester M. Nanoliposomal Minocycline for ocular drug delivery. Nanomedicine. 2013;9:130–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin T, Zhao P, Jiang Y, Tang Y, Jin H, Pan Z, He H, Yang VC, Huang Y. Blood-brain-barrier-penetrating albumin nanoparticles for biomimetic drug delivery via albumin-binding protein pathways for antiglioma therapy. ACS Nano. 2016;10:9999–10012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Jesús Valle MJ, Maderuelo Martín C, Zarzuelo Castañeda A, Sánchez Navarro A. Albumin micro/nanoparticles entrapping liposomes for Itraconazole green formulation. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2017;106:159–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang L, Liu Y, Wang N, Wang H, Wang K, Luo XL, Dai RX, Tao RJ, Wang HJ, Yang JW, Tao GQ, Qu JM, Ge BX, Li YY, Xu JF. Albumin-based LL37 peptide nanoparticles as a sustained release system against Pseudomonas aeruginosa lung infection. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2021;7:1817–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hao L, Zhou Q, Piao Y, Zhou Z, Tang J, Shen Y. Albumin-binding prodrugs via reversible Iminoboronate forming nanoparticles for cancer drug delivery. J Control Release. 2021;330:362–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Han Y, Liu Y, Ma X, Shen A, Liu Y, Weeranoppanant N, Dong H, Li Y, Ren T, Kuai L, Li B, An M, Li Y. Antibiotics armed neutrophils as a potential therapy for brain fungal infection caused by chemotherapy-induced neutropenia. Biomaterials. 2021;274:120849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang H, Ji Z, Feng Y, Yan T, Cao Y, Lu H, Jiang Y. Myriocin enhances the antifungal activity of fluconazole by blocking the membrane localization of the efflux pump Cdr1. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:1101553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim SH, Iyer KR, Pardeshi L, Muñoz JF, Robbins N, Cuomo CA, Wong KH, Cowen LE. Genetic analysis of Candida auris implicates Hsp90 in morphogenesis and Azole tolerance and Cdr1 in Azole resistance. mBio. 2019;10:e02529–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pasrija R, Panwar SL, Prasad R. Multidrug transporters CaCdr1p and CaMdr1p of Candida albicans display different lipid specificities: both ergosterol and sphingolipids are essential for targeting of CaCdr1p to membrane rafts. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:694–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Niimi M, Niimi K, Tanabe K, Cannon RD, Lamping E. Inhibitor-resistant mutants give important insights into Candida albicans ABC transporter Cdr1 substrate specificity and help elucidate efflux pump Inhibition. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2022;66:e0174821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shah AH, Banerjee A, Rawal MK, Saxena AK, Mondal AK, Prasad R. ABC transporter Cdr1p harbors charged residues in the intracellular loop and nucleotide-binding domain critical for protein trafficking and drug resistance. FEMS Yeast Res. 2015;15:fov036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iyer KR, Robbins N, Cowen LE. The role of Candida albicans stress response pathways in antifungal tolerance and resistance. iScience. 2022;25:103953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.He L, Wang H, Han Y, Wang K, Dong H, Li Y, Shi D, Li Y. Remodeling of cellular surfaces via fast disulfide-thiol exchange to regulate cell behaviors. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2019;11:47750–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts. 4th ed. CLSI standard M27. Wayne: CLSI; 2017.

- 33.Vyas VK, Bushkin GG, Bernstein DA, Getz MA, Sewastianik M, Barrasa MI, Bartel DP, Fink GR. New CRISPR mutagenesis strategies reveal variation in repair mechanisms among fungi. mSphere. 2018;3:e00154–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chali SP, Westmeier J, Krebs F, Jiang S, Neesen FP, Uncuer D, Schelhaas M, Grabbe S, Becker C, Landfester K, Steinbrink K. Albumin nanocapsules and nanocrystals for efficient intracellular drug release. Nanoscale Horiz. 2024;9(11):1978–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Qu N, Song K, Ji Y, Liu M, Chen L, Lee RJ, Teng L. Albumin Nanoparticle-Based drug delivery systems. Int J Nanomed. 2024;19:6945–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.da Silva CR, Silveira MJCB, Soares GC, de Andrade CR, Cabral VPF, Sá LGDAV, Rodrigues DS, Moreira LEA, Barbosa AD, da Silva LJ, da Silva AR, Gomes AOCV, Cavalcanti BC, de Moraes MO. Nobre júnior HV, de Andrade Neto JB. Analysis of possible pathways on the mechanism of action of Minocycline and Doxycycline against strains of Candida spp. Resistant to fluconazole. J Med Microbiol. 2023;72(10). 10.1099/jmm.0.001759. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Perumal V, Ravula AR, Agas A, Gosain A, Aravind A, Sivakumar PM, I SS, Sambath K, Vijayaraghavalu S, Chandra N. Enhanced targeted delivery of Minocycline via transferrin conjugated albumin nanoparticle improves neuroprotection in a blast traumatic brain injury model. Brain Sci. 2023;13(3):402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McEvoy K, Normile TG, Del Poeta M. Antifungal drug development: targeting the f Ungal sphingolipid pathway. J Fungi (Basel). 2020;6:142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Song J, Liu X, Li R. Sphingolipids: regulators of Azole drug resistance and fungal pathogenicity. Mol Microbiol. 2020;114:891–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Prasad R, Singh A. Lipids of Candida albicans and their role in multidrug resistance. Curr Genet. 2013;59:243–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moreno-Velásquez SD, Tint SH, Del Olmo Toledo V, Torsin S, De S, Pérez JC. The regulatory proteins Rtg1/3 govern sphingolipid homeostasis in the human-associated yeast Candida albicans. Cell Rep. 2020;30:620-29.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article. Access to raw data can be acquired by connecting to the corresponding author via email.