Abstract

Background

The ongoing conflicts and natural disasters in Ethiopia have led to a significant increase in the number of Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs), necessitating effective healthcare delivery in IDP camps. This study aims to assess the availability of essential medicines and inventory management practices and to identify common challenges within these camps in Eastern Amhara, Ethiopia.

Methods

An explanatory sequential mixed method was employed, from August to October 2023, in 5 IDP camps in Eastern Amhara, Ethiopia. Structured and semi-structure questionnaires were utilized. Data were collected through face-to-face and telephone interview, document review, and observation. Quantitative data were entered into Epi Data version 4.6 and analyzed by SPSS window version 26, and descriptive statistics were computed and summarized results were presented by using text, tables and graphs, while thematic analysis using open code software was employed for qualitative data analysis.

Results

The average availability of essential medicines in IDP camps was 77.3%. Inventory control cards were available in nearly half of the OPDs clinics in IDP camps. However, the overall updating practice on transaction was 0%. None of the IDP camps met the criteria for acceptable storage conditions. Only 18.2% of OPD clinics are adhered to FEFO inventory control procedure. Common challenges affecting the availability of essential medicines and inventory management practices in IDP include poor inventory management practices, national stock outs, irrational drug use, fraud and theft, insecurity, inadequate infrastructure, uncertainty, reliance on push delivery systems, lack of inter-agency collaboration, and limited resources.

Conclusion

The study found that while the average availability of essential medicines in IDP camps was fairly- high, stockouts were common, and none of the camps met the established criteria for acceptable storage conditions. Inventory management practices were weak, with poor adherence to protocols such as bin card updating, stock level reviews, and the FEFO system. The current study suggest that significant efforts are being made to supply IDP camps with essential medicines, despite the challenges posed by poor inventory management, national-level stock shortages, irrational drug use, fraud and theft, insecurity, inadequate infrastructure, uncertainty, reliance on push delivery systems, lack of inter-agency collaboration, and limited resources.

Keywords: Essential medicines, Inventory management practices, IDP camps, Ethiopia

Background

In humanitarian settings such as Internally Displaced People (IDP) camps, the availability of essential medicines is critical for addressing both acute and chronic health needs [1, 2]. However, ensuring consistent access to these medicines is challenging due to limited infrastructure, disrupted supply chains, and unpredictable demand patterns [3, 4]. In Amhara, Ethiopia, where conflict, displacement, and environmental factors have displaced thousands of people [5], healthcare services within IDP sites often struggle to maintain adequate inventories of essential medicines. This scarcity jeopardizes the ability to provide life-saving treatments and compromises the quality of care for displaced populations [6].

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines essential medicines as those that meet the most important healthcare needs of a population [7]. Their continuous availability is crucial to prevent disease outbreaks, manage chronic conditions, and ensure the well-being of individuals living under precarious conditions. However, inventory management practices including procurement, stock monitoring, storage, and distribution at IDP camps often face several challenges. These challenges arise from logistical constraints, poor forecasting, fragmented coordination, and frequent stock-outs [4]. Additionally, the reliance on donor-driven supply systems and emergency procurement strategies further complicates the sustainability of medicine availability [8, 9].

Poor inventory management can result in overstocking, which leads to wastage due to drug expiration, or understocking, which leaves critical medicines unavailable when they are needed most [10, 11]. At the same time, weak data systems and lack of trained personnel in IDP settings make it difficult to monitor stock levels accurately or respond promptly to shortages [4, 12]. These issues disproportionately affect the most vulnerable populations such as children, the elderly, and individuals with chronic illnesses who are dependent on timely and reliable access to medicines.

While efforts by government agencies, NGOs, and international organizations aim to provide healthcare services within IDP camps [13], limited research exists on the availability of essential medicines and the effectiveness of inventory management practices in these humanitarian settings. Without proper data and analysis, it becomes difficult to identify bottlenecks and implement strategies to improve service delivery. The findings from this study will contribute to a deeper understanding of the systemic issues affecting medicine availability in IDP camps, helping policy-makers, humanitarian organizations, and healthcare providers develop more effective supply chain strategies. Improving inventory management practices will ensure consistent access to essential medicines and ultimately enhance the quality of healthcare services for displaced populations in Amhara and beyond. Therefore, the aim of this study was to assess the availability of essential medicines and inventory management practices, to identifying the common challenges influencing the availability and inventory management practices at Internally Displaced People (IDP) camps in the Eastern Amhara region, Ethiopia. Finally, to provide actionable recommendations for improving medicine availability and inventory management practices.

Methodology

Study design

An explanatory sequential mixed method was used to generate pertinent information on the availability of EM, inventory management practice, and challenges at IDP camps in Eastern Amhara region, Ethiopia from August to October 2023. According to the national reports in April, 2022 Amhara region was the fourth largest IDP hosting region in Ethiopia and the number of IDPs in the region was estimated to be 462, 529 and 22,000 Eritrean refugees [5]. Approximatly more than 11 quasi- permanent and temporary IDP camps were located in Amhara region as used as a home by IDPs of which five IDP sites: namely China IDP camp, Weynshet IDP camp, Bakelo camp, Jara IDP camp, and Jari IDP camp, are the study area of for this study.

Study population

All IDP camps in Eastern Amhara region, outpatient clinic and/ or health service delivery points providing health services within the IDP camp in the selected IDP camps, all bin cards, internal facility reporting and resupply forms (IFRRs), all essential medicines as well as key stakeholders, including healthcare workers, supply chain managers, pharmacists, and humanitarian organization representatives.

Eligibility criteria

IDP camps established and functioned at least for one years and outpatient clinics within the selected IDP camps delivering health services for IDPs at least for six months were included. However, outpatient clinics in IDP camps, which have no separate storeroom from public health facility and outpatient clinics in IDP camps deployed or mobilized less than 6 months before the actual data collection period were excluded.

Sample size and sampling process

Five IDP camps with eleven outpatient clinics, which fulfilled the inclusion criteria were taken for the study. Twelve essential medicines recommended in the UNHCR diagnosis and treatment manual, to treat the common health problems in the study area were selected. The list was prepared based on the Ethiopian essential medicines list and it included all items that the list deemed them essential to be available in all Primary Health Care Units (PHCUs), the lowest level of healthcare provision system in Ethiopia. The sample size of bin cards and IFRR reports were also determined by the UNHCR essential medicines and medical supplies guidance which states that refugee camps should submit reports every month to their corresponding suppliers. Furthermore, the logistics indicators assessment tool (LIAT) revealed that a quantitative logistics health facilities assessment is recommended to review reports for a minimum of six months, which is about six reports (one IFRR every one month is equivalent to six IFRR reports within six months) from each OPD clinics. Thus, 66 IFRR reports (6 IFRR reports from each OPD clinics of the five IDP camps i.e. 11 × 6 = 66) and 132 bin cards (12 bin cards per OPD clinics i.e. 12 × 11 = 132) were reviewed. In-depth interviews were conducted with key informants including healthcare workers, supply chain managers, pharmacists, and humanitarian organization representatives.

Data collection tools and procedures

With respect to the information needed; two major sources were used in the study to gather information about the availability of EM, inventory management practice and associated challenges. The data were collected from both primary and secondary data sources. Data for the quantitative parts of the study were collected by using interviewer-administered, document review and observation through structured pretested questionnaires and checklists that are adapted from LIAT, UNHCR essential medicines and medical supplies guidance and a questionnaire developed by a previous study.

Qualitative study

For the qualitative part of the study, after identifying the key informants informed consent was obtained. The principal investigator conducted the face-to-face and telephone interviews by using semi-structured interview guide questions, which lasted an average of 25 min. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Key informants (namely pharmacists, other health professionals, team leaders, storekeepers, and representatives from donor organization) were employed to explore the challenges. Separate questionnaires were used to collect similar information relevant to their positions in the management process.

Data quality assurance

For the quantitative part of the study, the collected data were checked for completeness and accuracy daily. A pre-test was done to make sure whether the questionnaire is appropriate in the study population before the actual data collection time at Turk IDP camp, which is not included in the study. Regular supervision and training was given for 4 data collectors (3 pharmacists and 1 nurse) focused on how to manage the data collection process. For qualitative study, measures to ensure data qualities include a clear description of the methods used to collect and analyses the data. At the discussion section; in order to ensure the credibility of the findings, data collected from different sources were triangulated.

Data processing and analysis

For quantitative part of the study, after data collection, the collected data were cleaned, and checked for completeness. Data were entered into Epi Data version 4.6 and analyzed by Statistical Package of Social Science (SPSS) window version 26. For the analysis part, descriptive statistics were computed and summary results were also presented by using text, tables and graphs. The following standard indicators were used to measure quantifiable variables because it is difficult to measure the overall EMs availability and inventory management practice using a single indicator. Calculations for these indicators were based on the formulas developed by the Management Sciences for health.

From this the average percentage of product available on the day of visit for refugee camp were calculated as follows

Average percentage of IFRR correctly filled column were calculated as

While conducting qualitative analysis, the first step was transcription of the recorded interviews and then translated into English language. Field notes were converted into electronic documents. Qualitative data verification for accuracy and completeness done through closely examined and familiarized ourselves with their responses by taking notes. Translates and notes were analyzed thematically by open code software 4.2. After translation, the investigator based on the original terms that we have used developed codes. Sub-themes were created from the open codes, and subsequently main themes emerged based on the patterns and relationships between the categories. Finally, data collected from more than two sources were triangulated.

Operational definitions and definition of terms

Refugee or IDP camps: Camps are preferred place of containing displaced people, with an attempt to constitute and re-stabilize life [14].

Internal displaced people: “Persons or groups who have been forced to flee their home unexpectedly in large numbers, as a result of armed conflict, internal strife, systematic violations of human rights or natural or man-made disaster, who are within the territory of their own country”[15].

Logistic management information system (LMIS): is the system of records and reports that one uses to collect, analyze, organize and present logistics data suitable for decision.

Inventory management: It is the process of receiving, storing, issuing, recording, reporting and ordering, reordering, and accounting for stocks [16].

Essential medicine: The list was prepared based on the UNHCR and Ethiopian essential medicines list and it included all items that the list deemed them essential to be available in all Primary Health Care Units (PHCUs), the lowest level of healthcare provision system in Ethiopia.

Storage: Facility can be categorized based on the total scores they obtained in the storage condition checklist. Health facility storage condition is said to be acceptable: the facility has fulfilled at least 10 of the 12 criteria (80%) of the criteria for acceptable storage conditions.

Bin cards updated: To consider bin cards up-to-date, they had to be updated within the previous 30 days. In addition, if the bin card was last updated with the balance of zero and the facility has not received any of those products since the date of that entry, it is also considered updated.

Availability of EM: Product is said to be available, if it is available in the health facility during the data collection period. The availability of EM should be 100% [17] unless the following ranges could be used for describing the availability accordingly:

< 30%—very low.

30–49%—low.

50–80%—fairly high.

> 80%—high.

Results

Quantitative results

Availability of essential medicines

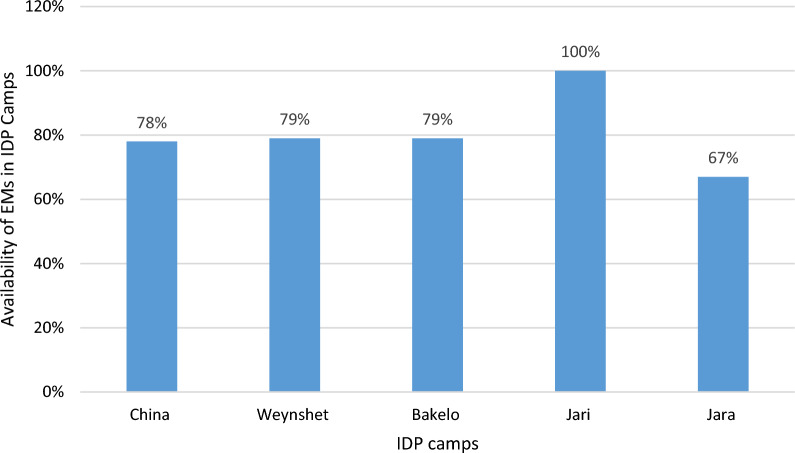

Availability of EMs was assessed by interviewing personnel responsible in managing pharmaceutical products on most frequently stock out medicines and observation with checklist. The overall availability of essential medicines in the studied IDP camps were 77.3%. Particular to each IDP camps the highest percentage (100%) were available at Jari IDP camp followed by 79%, 79%, and 78%, at Bakelo, Weynshet and China IDP camps whereas the lowest (67%) of EM were available in Jara IDP camp (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The availability of essential medicines per IDP camps, in Amhara regional state, Ethiopia, October 2024

From the identified essential medicines, the availability index of paracetamol, Amoxicillin, Albendazole, and Cotrimoxazole 240 mg/5 ml suspension were high. However, the availability index of ampicillin 500 mg injection was found to be low whereas the availability index of Arthemeter/Lumfantrine120 mg/20 mg, Metronidazole 250 mg, Doxycycline 100 mg, ORS, Iron sulfate 325 mg, Chloroquine 250 mg, Magnesium sulphate 50% w/v were fairly high, while at the time of data collection. All 11 (100%) of the SDP in IDP camps were experiencing stock out of certain pharmaceutical products in the 6 months prior to the survey. The survey also assessed the most frequently stock out essential medicines. According to the respondents essential medicines such as anti-malaria drugs, both topical and systemic antifungal medicines, ibuprofen, Cotrimoxazole 240 mg/5 ml suspension, iron sulfate 325 mg, and amoxicillin 250 mg were the most frequently stock out essential medicines in the six months prior to the survey (Table 1).

Table 1.

Availability of essential medicines in IDP camps, in Amhara regional state, Ethiopia, October 2024, (N = 12)

| Name of essential medicines | Availability at refugee camps | WHO availability index | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency (n) | Percent (%) | ||

| Paracetamol | 11 | 100% | High |

| Arthemeter/lumfantrine | 7 | 63.6 | Fairly high |

| Metronidazole | 8 | 72.7 | Fairly high |

| Doxycycline | 7 | 63.6 | Fairly high |

| Amoxicillin | 10 | 90.9 | High |

| Albendazole | 10 | 90.9 | High |

| ORS | 8 | 72.7 | Fairly high |

| Ampicillin | 4 | 36.4 | Low |

| Iron sulfate | 8 | 72.7 | Fairly high |

| Cotrimoxazole | 10 | 90.9 | High |

| Magnesium sulphate 50%w/v | 8 | 72.7 | Fairly high |

| Chloroquine 250 mg | 6 | 54.5 | Fairly high |

| Stock out commodities before resupply in the previous six months | 11 | 100 | High |

| List the commodities you have stock out of most frequently | Ibuprofen, antifungal (BBL and systemic) | Cotrimoxazole iron sulphate antimalarial | Amoxicillin 250 mg cloxacillin |

Inventory management practices in the IDP camps

Logistics management information system (LMIS)

More than half (54.5%) of OPD clinics in IDP camps have at least copy of bin cards to manage essential pharmaceutical commodities. Additionally, lower than half (45.5%) of OPD clinics in IDP camps have also at least copy of stock cards. However, a discrepancy for availability of bin cards were observed by product type ranging from 100 percent for paracetamol, metronidazole, Cotrimoxazole and amoxicillin to 0 percent for Magnesium sulphate 50% w/v. Although more than half of the SDP in IDP camps had bin cards for the assessed EMs, the overall bin card updating practice on transaction was 0%. In addition to bin card and stock card, all (100%) OPD clinics in IDP camps were using daily registration books to manage EMs (Table 2).

Table 2.

Recording practice in OPD clinics within the IDP camps in Eastern Amhara, Ethiopia October 2024, (N = 11)

| Variable | Category | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Availability of stock cards (updated) | Yes (No) | 5 | 45.5 |

| No | 6 | 55.5 | |

| Availability of daily registers (updated) | Yes (Yes) | 11 | 100 |

| Availability of bin cards | Yes | 6 | 54.5 (0%) |

| No | 5 | 45.5 |

| Variable | Essential medicines | IDP camps | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I11 | I21 | I12 | I22 | I41 | I31 | ||

| Bin card available (updated) | Paracetamol | Yes (no) | Yes (no) | Yes (no) | Yes (no) | Yes (no) | Yes (no) |

| Arthemeter/lumfantrine | No | Yes (no) | No | No | Yes (no) | Yes (no) | |

| Metronidazole | Yes (no) | Yes (no) | Yes (no) | Yes (no) | Yes (no) | Yes (no) | |

| Doxycycline | Yes (no) | Yes (no) | No | Yes (no) | No | Yes (no) | |

| Amoxicillin | Yes (no) | Yes (no) | Yes (no) | Yes (no) | Yes (no) | Yes (no) | |

| Albendazole | Yes (no) | Yes (no) | No | Yes (no) | No | Yes (no) | |

| ORS | No | No | No | Yes (no) | No | No | |

| Ampicillin | Yes (no) | No | No | No | Yes (no) | Yes (no) | |

| Iron sulfate | Yes (no) | Yes (no) | Yes | No | Yes (no) | Yes (no) | |

| Cotrimoxazole | Yes (no) | Yes (no) | Yes (no) | Yes (no) | Yes (no) | Yes (no) | |

| Magnesium sulphate 50% w/v | |||||||

| Yes (no) | No | No | No | Yes (no) | Yes (no) | ||

| Chloroquine 250 mg | No | No | No | No | No | No | |

Availability of internal facility report and resupply form (IFRR)

The availability of IFRR to order and report those EM from/to the cluster health center monthly; were 100%. Of which the percentage of including the three essential logistics data (stock on hand, quantity used, and loss and adjustment) on the reports were 27.3%, 36.4% and 63.6% respectively. In addition to IFRR, list of medications were also used as a mines of reporting and ordering tool in 54.5% of OPD clinics in IDP camps. With regard to frequency of reporting, more than half (54.5%) of OPD clinics in IDP camps were send reports randomly to the donor’s field office, however, nearly 73% of OPD clinics send report monthly to cluster health centers. Of which only four (36.4%) of the OPD clinics have send reports during the one month period prior to the study (Table 3).

Table 3.

Reporting practice and training on the logistics management in IDP camps SDP in Amhara regional state, Ethiopia, October 2024, (N = 11)

| Variables | Category | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Use IFRR | Yes | 11 | 100 |

| No | – | – | |

| IFRR includes stock on hand | Yes | 3 | 27.3 |

| No | 8 | 72.7 | |

| IFRR includes quantity used | Yes | 4 | 36.4 |

| No | 7 | 63.6 | |

| IFRR includes loss and adjustment | Yes | 6 | 54.5 |

| No | 5 | 45.5 | |

| Use list of medications during reporting | Yes | 6 | 54.5 |

| No | 5 | 45.5 | |

| How often drug related reports sent for donors field office | Monthly | 2 | 18.2 |

| Quarterly | 2 | 18.2 | |

| Semi-annually | – | – | |

| Annually | 1 | 9.1 | |

| Randomly | 6 | 54.5 | |

| How often drug related reports sent for cluster health center | Monthly | 8 | 72.7 |

| Quarterly | 2 | 18.2 | |

| Semi-annually | 1 | 9.1 | |

| Annually | – | – | |

| When was the last time you sent a report | Never | – | – |

| Within the last month | 4 | 36.4 | |

| 2 months ago | 2 | 18.2 | |

| 3 months ago | 4 | 36.4 | |

| More than 3 months ago | 1 | 9.1 | |

| Who determines this camps resupply quantities | The camp itself | 2 | 18.2 |

| Higher level official | 9 | 81.8 | |

| Randomly | 3 | 27.3 | |

| Self-learning | 2 | 18.2 |

Training on logistics management

Among the total respondents 5 (45.5%) of professionals in charge of the logistic activities in selected OPD clinics indicated that they learnt logistics forms from on the job training. Three (27.3%) of the respondents learned from formal IPLS training and 2 (18.2%) of the respondents were using the logistics forms by self-learning without any formal or on job training and one (9.1%) of the respondent never learned on how to complete the logistics forms (Table 3).

Inventory control policy

Only two (18.2%) have written guideline for storage and handling of all products. More than one third (36.4%) of the OPD clinics in IDP camps have guidelines or established policies for maximum-minimum stock levels. Of which, only half of them applied the maximum-minimum inventory control policy. Nearly half (45.5%) of OPD clinics in IDP camps were stock EM a maximum for 1 month consumption. Maximum and minimum stock levels for products were reviewed periodically (monthly) only in 18.2% of the OPD clinics, however, a little bit more than half (54.5%) of the OPD clinics review stock level randomly to ensure that they are sufficient. Only 36.4% of the OPD clinics in IDP camps follow first-to-expire, first-out (FEFO) inventory control procedure while storing and dispensing EMs (Table 4).

Table 4.

Inventory control procedure in IDP camps in Amhara regional state, Ethiopia, October 2024, (N = 11)

| Variable | Category | Frequency (n) | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Guidelines and established policies for max–min stock levels | Yes | 4 | 36.4 |

| No | 7 | 63.6 | |

| Inventory control guidelines for products applied and stock levels generally fall between max-mini | Yes | 2 | 18.2 |

| No | 9 | 81.8 | |

| Roughly how much stock of specific medicine do you keep | < one month of stock | 5 | 45.5 |

| One month of stock | 3 | 27.3 | |

| Two months of stock | 3 | 27.3 | |

| Four months of stock | – | – | |

| FEFO, policy during storing and issuing stock | Yes | 4 | 36.4 |

| No | 7 | 63.6 | |

| Maximum and minimum stock level for products reviewed periodically | Yes | 2 | 18.2 |

| No | 9 | 81.8 | |

| How often do you review the stock levels to ensure that they are sufficient | Monthly | 2 | 18.2 |

| Quarterly | 1 | 9.1 | |

| Semi-annually | 2 | 18.2 | |

| Annually | – | – | |

| Randomly | 6 | 54.5 | |

| Have written guidelines for the storage and handling of all products | Yes | 2 | 18.2 |

| No | 9 | 81.8 |

Storage condition

There are no OPD clinics in IDP camps, which fulfill appropriate storage conditions by fulfilling at least ten of the twelve criteria set for acceptable storage condition. Nearly half (45.5%) of OPD clinics in IDP camps fulfilled six and above (50% and above) of the twelve criteria set for acceptable storage conditions. The condition met most often by SDP was the facility separates damaged and expired products from usable products and removes them from the inventory (81.8%); while the least satisfied criteria were products are organized according to FEFO and products are stacked at least 10 cm off the floor (18.2%) (Table 5 and 6).

Table 5.

Storage condition obtained through observation in IDP camps SDP in Amhara regional state, Ethiopia October 2024, (N = 11)

| Variable | Frequency(N) | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Products ready to dispensing are arranged so that identification labels and expiry dates and/or manufacturing dates are visible | 5 | 45.5 |

| Products are stored and organized in a manner that facilitate first-to-expire, first-out (FEFO), counting and general management | 2 | 18.2 |

| Cartons and products are in good condition, not crushed due to mishandling | 7 | 63.6 |

| The facility separates damaged and/or expired products from usable products and removes them from the inventory | 9 | 81.8 |

| Products are protected from direct sunlight, water, and humidity at all times of the day and during all seasons | 3 | 27.3 |

| Insects and rodents not present. (Check the storage area for traces of rodents [droppings or insects].) | 7 | 63.6 |

| The storage area is secured with a lock and key, but is accessible during normal working hours; access is limited to authorized personnel | 6 | 54.5 |

| Storeroom is maintained in good condition (clean, all trash removed, shelves are sturdy, and boxes are organized) | 3 | 27.3 |

| The current space and organization is sufficient for existing products and reasonable expansion (i.e., receipt of expected product deliveries for foreseeable future) | 3 | 27.3 |

| Products are stacked at least 10 cm (4 inches) off the floor | 2 | 18.2 |

| Products are stacked at least 30 cm (1 foot) away from the walls and other stacks | 4 | 36.4 |

| Products are stacked no more than 2.5 m (8 feet) high | 4 | 36.4 |

Table 6.

Summary number of storage condition criteria fulfilled by selected IDP camps Amhara regional state, Ethiopia, October 2024

| Number of criteria | No of service delivery point | % of criteria fulfilled | WHO storage index |

|---|---|---|---|

| Six of the criteria | 2 | 50% | Poor |

| Seven of the criteria | 1 | 58.3% | Poor |

| Eight of the criteria | – | – | – |

| Nine of the criteria | 2 | 75% | Poor |

| Ten of the criteria | – | – | – |

| Eleven of the criteria | – | – | – |

| All of the criteria | – | – | – |

Qualitative findings

Overview of the study

The investigator conducted interviews with 14 key informants, including nine pharmacy professionals and five public health officers. The thematic analysis resulted to have 41 codes in 10 sub-themes, which were grouped into one key themes. The theme was about challenges on availability and inventory management practices.

Theme one: challenges of essential medicines availability and inventory management practices

Common challenges affecting the availability of essential medicines and inventory management practices in IDP camps in Eastern Amhara, Ethiopia, include poor inventory management practices, national-level stock shortages, irrational drug use, fraud and theft, insecurity, inadequate infrastructure, reliance on push delivery systems, uncertainty, lack of inter-agency collaboration, and limited resources.

Sub-theme 1: irrational drug use

Experts have cited irrational drug use among displaced populations as a major challenge, particularly in camps with multiple outpatient (OPD) clinics. One key issue is the lack of patient identification cards, making it difficult to track who is receiving treatment and who is not. Additionally, since medical services are provided free of charge, there is no financial accountability, which means patients have no duty to pay any payment for the treatment of themselves. Experts emphasize that these factors contribute significantly to inappropriate medication use from the perspective of displaced individuals. Here is what experts have to explain concerning drug misuse from refugee perspective: “Indeed, a key issue contributing to medication shortages in our IDP camp is that patients frequently seek treatment from multiple outpatient clinics, often disregarding previously prescribed medications” (Female, 4 years of experience, dispensary in refugee camps).

Sub-theme 2: fraud and theft

Fraud and theft were not major concerns for some experts, and several organizations reported that they had not encountered such issues since the beginning of their operations. However, other experts noted that misconduct related to fraud and theft within the supply chains remains a challenge. Key informants indicated that UN agencies are actively working to identify these issues in collaboration with third parties. If such problems are confirmed, the agencies may impose bans on donations, similar to actions taken previously in the northern part of Ethiopia. The following are some excerpts from the KI: “Occasionally, medications like family planning are taken by professionals for themselves, try to use these medications for their beloved family, or sold those medications for private pharmacy” (Male, 2 years of experience, dispensary in IDP sites).

Sub- theme 3: infrastructure

More than half of the experts raised concerns related to infrastructure. Almost all respondents echoed worries about inadequate storage areas and excessively small storerooms. Key informants noted that medications are often stored in arbitrary locations, lacking appropriate spaces for managing pharmaceutical products according to established guidelines. Consequently, disorganized storerooms hinder operational efficiency, as staff spend excessive time searching for necessary pharmaceuticals.

Additionally, several respondents pointed out that inadequate storage areas are a root cause of many problems affecting the availability of essential pharmaceuticals, emphasizing the urgent need for intervention in this area. The following are some excerpts of what the experts say on challenges related to infrastructure: “Drugs are often stored in arbitrary locations, lacking proper rooms to ensure their safety. Moreover, when medications are moved from storage to the working area, they are exposed to adverse weather conditions. The private house we utilize has been adapted to the investor’s preferences, resulting in unsuitable spaces for our daily operations” (Female, 4 years of experience, dispensary in refugee camps).

Sub-theme 4: uncertainty

Another challenge mentioned by respondents is uncertainty, which adversely impacts relief operations and the availability of pharmaceutical products. The lack of effective forecasting methods, such as placing orders based on updated refugee numbers, has led to frequent medicine stock outs. This issue is largely linked to the rising influx of new refugees. The following are a project manager’s remark made related to uncertainty: “(…) Because of the ongoing attack there is large influx of new IDPs; in one movement everything looks fine, within days everything is changed” (Male, 7 years of experience, UNICEF representative).

Sub-theme 5: security issues

Security issues were another challenges constantly rose by many respondents and its impact on operation in relief organization. “When there is conflict, there is usually tension for health professional themselves that disrupt our normal activities. Last month there is a conflict between Amhara defense force Fano and Ethiopian defense force; still there are team members who are unable to back to their work. Because during conflict no one can safeguard staff members, as a result there is job absenteeism for weeks and months” (Male, 2 years of experience, dispensary in IDP sites).

Sub-theme 6: reliance on push system

Another issue frequently raised by half of the experts was the push delivery system used in IDP camps. Experts noted problems associated with the presence of unnecessary items in the supply kits, as well as expired or soon-to-expire products. Some also indicated that the push system is linked to delays in fulfilling orders and the inability to deliver the complete requested medications. “Sometimes we encounter delivery of unnecessary medicines, including near-expired or even expired products and drugs that are not suitable for our setup” (Male, 3 years of experience, team leader in IDP sites)..

Sub-theme 7: limited resources

Furthermore, IDP camps are struggling with limited resources, in terms of financial, human and material related resource, which are constantly lamented by more than half of the respondents. Experts noted that a lack of funding hampers their ability to secure dedicated storerooms and proper shelving. Additionally, some experts mentioned that budget constraints limit the scope of service delivery. Below are some excerpts from the key informants. “There is sever financial hardship in the region as conflict has affected the healthcare system as a result supply from the government particularly from cluster health center is reduced not only this but also supplies from donors might be used by the cluster health centers” (Male, 7 years of experience, UNICEF representative).

Sub-theme 8: poor inventory management practices

Inventory management practice receives less attention at IDP camps because stakeholders are more focused on providing emergency response. The lack of credible information poses a significant challenge for humanitarian organizations. This concern is well articulated by one expert who stated “Yes, this is one of the most pressing issues, yet it is often overlooked: negligently produced reports that are entirely untrue and at odds with both reality and their own previous reports” (Male, 7 years of experience, UNICEF representative).

Key informant from the IDP camps also thought, “We are expected to send monthly reports but our staff has to sustain heavy workload and sometimes one member is required to work as store manager, a clinical pharmacist and dispenser in a single IDP site. In addition, different stakeholders are required to send different reports as an urgent case outside the programmed schedule. Therefore, we do not have time to compile reports” (Male, 2.5 years of experience, dispensary in IDP sites).

Sub-theme 9: lack of inter-agency collaboration

Conflict of interest another mentioned challenges shared by some of the experts. As mentioned by experts conflicts of interest are not only between different organizations but also there are intra team conflicts. Best described by the following excerpts: “(…) there is intense rivalry among partners for greater achievement, and the only linkage that is permissible is through stock out (…)” (Male, 2.5 years of experience, dispensary in IDP sites).

Sub-theme 10: national-level stock shortages

Frequent stock outs are cited by two thirds of the key informants as one of the main problems in IDP camps. Experts tend to repeat issue more than others. The main source of these concerns is national level stock shortages, but they were also raised alarms on stock out at the cluster health center levels are more complicated due to the inability of IDP camps to maintain adequate supplies of pharmaceuticals. The following remarks had better describe the situation related to stock out: “products provided by the government frequently run out of stock, particularly program medications like anti-malarial drugs. This is a result of both the high disease prevalence in the area and the nationwide shortage of medications (Female, 3 years of experience, dispensary in IDP site).

Discussion

Availability of essential medicines

Availability of essential medicines has massive impact on the quality of health care and patient satisfactions. Unavailability of EM may poses patients loss confidence on the health care facility as a result; in order to make sure that their treatment is uninterrupted, patients may also have to pay extra costs [18]. The finding of this study showed that the average availability of essential medicines (n = 12) in IDP camps were found to be 77.3%. The finding of the current study is inline with a study conducted at a national level in Ethiopia, Malawi, and Seri Lanka, 70%, 56%, and 71% of essential medicines were available at the day of visit respectively in public health facilities [19]. This may be due to; both IDP camps and public health facilities in these regions may face limited budgets, affecting their ability to procure and maintain adequate stocks of essential medicines. Furthermore, In many low-resource settings, IDP camps and public health systems depend heavily on international aid and donations for medical supplies. Fluctuations in donor funding and external support can impact the availability and consistency of medicine supplies in these settings. Data obtained from the key informants revealed that the implementation of adaptive management system such as shifting system, and establishing an immediate warning system to detect the shortages may also contribute to this agreement. While the availability of essential medicines in the current study aligns with findings from national and international studies, this alone does not ensure the medicines are appropriate for the health needs of IDP populations. Identifying local disease threats is crucial to guide the selection and quantity of medicines. In dynamic and high-risk settings like IDP camps, aligning supply with disease patterns is vital for preparedness and effective response. Future efforts should integrate disease surveillance to improve medicine relevance and impact.

This finding is considerably below the World Health Organization (WHO) recommendation that EMs should be available at a rate of 100%. It also fails to meet the minimum threshold of 80% availability stipulated by the WHO for public facilities [17]. The finding of the current study was also lower than a study conducted in public health facilities in Gondar Ethiopia, which was 91% [20]. This may be due to the fact that, IDP camps are often located in areas affected by conflict or displacement crises, where supply chains are frequently disrupted. Transportation challenges, security risks, and infrastructure issues can make it harder to deliver medicines reliably to camps compared to established public health facilities in more stable locations. Furthermore, Public health facilities may receive more consistent funding and resources from the government or non-governmental organizations. IDP camps, on the other hand, often rely on temporary or emergency aid, which may not be as stable or adequate to maintain a regular supply of essential medicines. Humanitarian organizations often have also to prioritize among numerous needs, leading to limited budgets for medicine. In addition to this, proper storage facilities for medicines may be lacking in IDP camps, leading to rapid depletion of supplies or spoilage of medications. Public health facilities in places are more likely to have dedicated infrastructure to store and manage medicines effectively. Even when medicines are delivered to IDP camps, distribution to all individuals in need can be challenging due to overcrowding, safety concerns, and logistical barriers within the camp [21]. According to experts from the key informants limited resources, poor infrastructure, and arbitrary store rooms are among the major challenges impacting availability of EM at the level of IDP camps.

However, the availability of essential medicines (EMs) in IDP camps is higher than that reported in a systematic review examining the availability of EMs for children in Ethiopia and Guatemala, which found that availability in both public and private facilities was below 50% [19, 22]. This discrepancy may be attributed to several factors, targeted interventions aimed at enhancing access to EMs in humanitarian settings, and increased funding and support for health services in IDP camps. Additionally, the focused nature of health interventions in these camps may prioritize essential medicines more effectively than in broader public health systems.

From the identified EM the availability index of ampicillin, was low. The low availability index of ampicillin in IDP camp could be due to high demand for antibiotics: IDP camps often have crowded living conditions that increase the risk of infections. This can lead to a higher-than-anticipated demand for antibiotics like ampicillin, resulting in faster depletion of stocks. The present study also found that all (100%) OPD clinics in IDP camps faced stock out for certain EMs in the six months prior to the survey. This finding is supported by a study conducted in Dessie public health facilities, which revealed that 88.9% of health facility was faced stock out [23]. The 100% stock-out rate of certain essential medicines (EMs) in OPD clinics within IDP camps over the six months prior to the survey could be due: IDP camps often experience sudden population increases due to new displacements, leading to unexpectedly high demand for medicines. Such surges are difficult to forecast and can rapidly exhaust existing supplies. Moreover, OPD clinics in IDP camps may operate separately from the public health supply chain. Without strong integration or coordination with local health systems, it becomes challenging to ensure regular and reliable access to essential medicines.

The finding from the current study suggest that significant efforts are being made to supply IDP camps with essential medicines, despite the challenges posed by displacement, logistical issues, and resource constraints. It reflects a positive outcome of targeted interventions by humanitarian organizations, local authorities, and international donors to support the health needs of displaced populations. In addition to this, the fairly high availability of essential medicines in IDP camps can help reduce health disparities between displaced populations and local communities. Maintaining sustainable availability could promote health equity, ensuring that vulnerable populations in camps have access to similar standards of care as those in stable communities. Although the availability rate is fairly high, there is still a gap from the WHO recommendation of 100% of essential medicines should be available. This gap suggests a need for continuous improvement in supply chain management, particularly for medicines with more frequent stock-outs and interventions might emphasize on sustainable availability of EMs at these levels because provision of healthcare service for IDPs primarily relies on OPD clinics located in IDP camps.

Inventory management practices

The availability and application of various logistic forms varies among the various OPD clinics within the IDP camps. The availability of IFRR report formats are 100% in OPD clinics. However, the availability of blank IFRRs is high. This finding is in line with previous conducted study at national level in Ethiopia [24]. Only 27.3% and 54.5% of the SDPs report stock on hand and loss and adjustment data respectively. The low utilization of IFRRs in IDP camps could be attributed to: healthcare workers in IDP camps often face high patient loads and limited resources, which can lead to prioritizing immediate patient care over administrative tasks like completing IFRRs. This pressure may result in forms being neglected or underutilized. Furthermore, if resupply processes are unpredictable and there is a lack of follow-through on reported needs, and feedback on the data submitted via IFRRs, staff may feel that filling out IFRRs is futile. This can create a sense of disillusionment with the system and lead to lower utilization. According to the KI, humanitarian settings, particularly in IDP camps, inventory management practices often receive less emphasis due to various challenges and competing priorities.

Only four (36.4%) of the SDPs have send reports during the one month period prior to the study. The finding of the current study is lower than similar study conducted in public health facilities of Dessie in which, 67% of health facilities includes stock on hand and loss and adjustment data in the report and 56% of the health facilities sent the report in the last month [23]. The low reporting rate among OPD clinics in IDP camps over the one month prior to the study could be due to overburdened healthcare staff, insufficient feedback on previously submitted reports, and resupply processes are erratic and there is no follow-up based on reports submitted. Furthermore, in conflict-affected regions, ongoing insecurity may disrupt the ability to collect and send reports, as healthcare workers might be focused on immediate survival and care rather than administrative tasks.

Inventory control cards were available in nearly half of the OPDs in IDP camps. However, the overall bin card updating practice on transaction was 0%, which is far less than studies conducted in Dessie (86%), Adama (66.67%), Jimma (83.33%), and Uganda public health facilities [25–27]. This huge variation could be attributed to: the inherently unstable environment in IDP camps can lead to disruptions in daily operations. Frequent changes in staffing or challenges due to the humanitarian context may impede the consistent updating of records. Besides, in crises, there tends to be a focus on immediate health needs rather than long-term logistical practices. Staff may prioritize patient care over administrative duties, resulting in zero updates to bin cards. Lack of accountability and standard operating procedures in IDP camps may contribute to a complete absence of practices around inventory management.

In the present study, none of the IDP camps met the criteria for acceptable storage conditions. This contrasts sharply with findings from previous studies conducted at the national level in Ethiopia, as well as in the West Wollega and Jimma zones, where 55%, 73.91%, and 83.33% of health facilities, respectively, complied with the established criteria for acceptable storage conditions [24, 26, 28]. The absence of any IDP camps meeting the criteria for acceptable storage conditions in the present study, could be attributed to many IDP camps are set up in emergency situations, often in makeshift facilities that lack proper infrastructure. IDP camps frequently operate with limited financial and material resources; and priority may be given to immediate healthcare delivery, food, and shelter rather than long-term investments in logistics and storage infrastructure, which can affect the quality of storage facilities. Furthermore, budget constraints along with lack of coordination between humanitarian organizations and local health authorities may lead to inadequate oversight of storage conditions, and may prevent the implementation of necessary upgrades to meet acceptable storage standards. The qualitative finding that mentioned in sub-theme three also supported the results. The KI mention that: “Drugs are often stored in arbitrary locations, lacking proper rooms to ensure their safety”.

The low adherence to protocols such as periodic review of stock levels and the FEFO inventory control procedure for storing and dispensing medicines in IDP camps can be attributed to. This finding is also much lower than a study conducted at national level in Ethiopia and Adama, which revealed that more than 60% and 80% of the health facilities follow the principles of FEFO respectively [24, 26]. Low adherence to such protocols can be attributed to the high patient load and demands placed on healthcare workers in IDP camps can lead to burnout and stress. As a result, they may focus on patient care rather than on the review of stock levels or inventory management procedures. Furthermore, lack of accountability and supervision, perceived complexity of procedures, absence of standard operating procedures, and the nature of IDP camps may result in low adherence for such protocols.

The higher-level officials determined the OPD clinics resupply quantities. These findings are in contrary to previous study conducted in Adama town in which, all health centers determine their own resupply quantity using formula based on annual consumption [26]. The determination of resupply quantities OPD clinics within the IDP camps may be due to In the context of IDP camps, where situations can rapidly change due to new influxes of people or outbreaks of disease, higher-level officials may need to quickly adjust resupply strategies to respond to emerging needs effectively. Additionally, higher-level officials often coordinate with various stakeholders, including NGOs and international organizations, to ensure that resupply quantities align with broader humanitarian response strategies. While centralized determination of resupply quantities by higher-level officials can enhance consistency and efficiency, it is important to ensure that local healthcare providers are engaged in the process. Their insights and knowledge about specific needs at the IDP camps level are crucial for accurate assessments and effective resource allocation. This finding were also in agreement with the qualitative finding stated in sub-theme six: “IDP camps heavily reliance on push system”.

The current study suggests that adopting standardized inventory management practices and improving storage conditions could significantly enhance operations in IDP camps and help close existing gaps. Organizations are increasingly encouraged to implement innovative inventory management strategies that accelerate value creation, in response to growing competition and stakeholder pressures. In this demanding environment, the sustainability of organizations that do not embrace these best practices and strategies may be at risk. In the face of intense competition, proactively and innovatively investing in an effective inventory management practices should be a top priority for organizational leadership aiming for growth. Successful implementation requires active engagement and commitment from stakeholders at all levels. Therefore, a collaborative approach involving donors, national governments, and IDP camps is essential for establishing sustainable inventory management practice.

Challenges of essential medicines availability and inventory management practices

Consistent with previous research in Nigeria, South Africa, Mozambique, Kenya, Ethiopia, and other sub-Saharan African regions, the present study identified persistent challenges affecting healthcare delivery IDP camps. Key issues mirrored across studies include the lack of credible information and capacity in terms of human resource, infrastructural issue, poor inventory control practices, reliance on push system and budgetary limitations [11, 25, 29–34]. The consistency in these findings likely stems from several interrelated factors. Many countries in sub-Saharan Africa face systemic limitations in public health infrastructure and funding, which are often amplified in high-need settings like IDP camps. Additionally, similar socioeconomic and political contexts marked by limited resources, high population mobility, and frequent crises may contribute to persistent weaknesses in healthcare systems across the region. Furthermore, the widespread use of centralized, top-down approaches to supply chain and resource allocation can lead to mismatched local needs, perpetuating inefficiencies across different contexts [12]. Addressing these challenges will require coordinated, region-specific strategies that prioritize flexibility, sustainability, and community-based solutions.

Unlike previous studies on public health facilities, experts identify irrational drug use, uncertainty, lack of inter-agency collaboration, inadequate storage facilities, and insecurity as some of the foremost challenges in IDP camps. According to previous study; this may be due to the nature of humanitarian relief operation and the critical challenges stem from a mix of logistical, structural, and social factors unique to the IDP environment [4]. Addressing these issues requires a comprehensive approach that includes both short-term measures such as securing resources and long-term solutions, such as improved funding, regulatory oversight, and collaboration with security forces.

Limitation of the study

Firstly, the lack of specific studies on the availability of essential medicines and inventory management practices in IDP camps presents a significant challenge for this study. As we pointed out, much of the existing literature focuses on public and private health facilities, which are fundamentally different from the volatile and resource-constrained environments of IDP camps. However, in the absence of direct studies, drawing comparisons with public and private health facilities can still offer useful insights, even though the context differs. Secondly, qualitative data collection was hindered by participant refusal and organizational restrictions, particularly among donor agencies, limiting a fuller understanding of system-level barriers. These challenges are not uncommon in such environments, and they highlight the complex nature of conducting research in sensitive settings where confidentiality and privacy are major concerns. Lastly, the presence of unfilled and incomplete logistics record forms in the IDP camps posed a significant challenge for accurately assessing essential medicine availability, inventory management practices, and their alignment with the actual disease burden. These data gaps hindered the ability to conduct a comprehensive analysis. Consequently, the study primarily focused on point availability: the availability of medicines at a specific point in time rather than more dynamic indicators such as availability trends over time or detailed evaluations of inventory management performance.

Suggestion for future researches

To expand the generalizability of findings and deepen the understanding of essential medicine availability and inventory management practices in IDP camps, future studies should incorporate disease surveillance data to evaluate whether essential medicine supply aligns with the specific health needs of IDP populations. This will support more targeted and effective inventory management. Furthermore, future research should also consider alternative study designs and broader variables. A longitudinal study would provide valuable insights into how these challenges evolve over time, while the exploration of additional factors like the regulatory environment and technology usage could offer a more comprehensive view of the systemic and operational barriers to efficient inventory management. By investigating these broader challenges, future research can inform more targeted interventions, helping to improve the delivery of essential medical supplies in humanitarian settings.

Recommendations

Improve supply chain coordination

Establishing clear coordination frameworks between government bodies, humanitarian organizations, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and local healthcare providers is essential to improve the procurement and distribution of essential medicines. This can be supported through the use of integrated information systems to monitor stock levels in real time, enabling timely replenishment and reducing the risk of stockouts. Furthermore, humanitarian actors operating in IDP camps should be encouraged to explore opportunities for shared logistics and storage spaces to minimize duplication, enhance efficiency, and optimize the use of limited resources. Designating lead agencies with proven expertise in supply chain and inventory management can also enhance accountability and promote consistent practices in medicine handling, storage, and rotation. Such collaborative and coordinated approaches can significantly strengthen overall system performance and improve the reliability of essential medicine availability in resource-constrained and high-need settings.

Strengthen forecasting and procurement

Develop demand forecasting models based on population health needs to avoid stock-outs and overstocking and implement pre-positioning strategies to stock essential medicines before anticipated disruptions.

Enhance storage and distribution capacity

Improve storage facilities at IDP camps to meet WHO and UNHCR guidelines for medicine storage and use mobile warehouses and distribution hubs to overcome geographical and infrastructure challenges.

Capacity building for healthcare workers

Provide training on inventory management for healthcare workers and pharmacists, focusing on stock management, and record keeping. Assign dedicated pharmacists or inventory officers at OPD clinics within the IDP camps to manage stock more efficiently.

Strengthen monitoring and evaluation (M&E)

Implement regular monitoring and evaluation mechanisms to track medicine availability and identify gaps in supply. Use stock-out reporting tools to quickly address shortages and mobilize emergency supplies.

Leverage the implementation of integrated pharmaceutical logistics system (IPLS)

Adopt Integrated Pharmaceutical Logistics System for tracking stock levels reporting, recording, integrated logistics management system and generating alerts for low inventory. Explore the use of mobile apps for real-time reporting of stock-outs and supply delays.

Conclusion

The average availability of essential medicines in IDP camps was fairly high. However, all outpatient department (OPD) clinics within these camps experienced stockouts of certain essential medicines at some point during the six months prior to the survey. Additionally, none of the IDP camps met the established criteria for acceptable storage conditions. While blank IFRR forms were generally available at the IDP camps’ service delivery points, the overall practice of updating bin cards and stock cards was found to be significantly low. Adherence to inventory management protocols, including periodic stock level reviews and the FEFO system for storing and dispensing medicines, was also limited. Key challenges contributing to these gaps included poor inventory management, national-level stock shortages, irrational drug use, fraud and theft, insecurity, inadequate infrastructure, uncertainty, reliance on push delivery systems, lack of inter-agency collaboration, and limited resources. These findings highlight critical areas for improvement to ensure reliable medicine availability and effective inventory management in IDP settings.

Acknowledgements

Finally, I would like to express my special thanks to study participants for their great contributions for the success of this study. Their assistance and positive cooperation were invaluable throughout the data collection process. We are grateful to every study members for their technical support in data analysis and publication preparation.

Abbreviations

- EMs

Essential medicines

- FEFO

First expire first out

- IDP

Internal displaced people

- IFRR

Internal facility report and requisition

- LIAT

Logistics indicator assessment tool

- OPD

Out patients department

- SPSS

Statistical package for social sciences

- UNHCR

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees

- WHO

World Health Organization

Author contributions

TTA, GWG, YAW, EDG, AE, and KS: Reviewing the literature, drafting proposals, gathering information, and obtaining ethical approval. TTA, GWG, YAW, TBA, MD, and TM: Developing the idea, obtaining funds, gathering information, conducting formal analysis, and creating tables and figures. When it comes to creating the first draft and the manuscript’s review and editing, each author contributes equally.

Funding

The authors did not receive any financial or material support.

Data availability

The dataset used and analyzed during this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The School of Pharmacy Research Review Committee on behalf of the University of Gondar Research and Ethics Review Board (SOPS/165/2023) granted ethical approval for the study. Informed written consent was obtained from all participants prior to their involvement in the study. To maintain confidentiality, no participant names or personal identifiers were collected; instead, unique codes were used to identify participants. All information was strictly used for research purposes only.

Consent to publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Sanders D. The struggle for health: medicine and the politics of underdevelopment. Oxford University Press; 2023.

- 2.Nouri S. Effects of conflict, displacement, and migration on the health of refugee and conflict-stricken populations in the Middle East. Institute of Advanced Engineering and Science; 2019.

- 3.Kovács G, Spens KM. Humanitarian logistics in disaster relief operations. Int J Phys Distrib Logist Manag. 2007;37(2):99–114. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patil A, Shardeo V, Dwivedi A, Madaan J, Varma N. Barriers to sustainability in humanitarian medical supply chains. Sustain Prod Consum. 2021;27:1794–807. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsegay B, Gezahegne K. Internal displacement in Ethiopia: towards a new policy and legal framework for durable solutions. Nairobi, Kenya: Heinrich Böll Foundation. Available at https://hoa.boell; 2023.

- 6.Al-Rousan T, Schwabkey Z, Jirmanus L, Nelson BD. Health needs and priorities of Syrian refugees in camps and urban settings in Jordan: perspectives of refugees and health care providers. Eastern Mediterr Health J. 2018;24(3):243–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bigdeli M, Peters DH, Wagner AK, Organization WH. Medicines in health systems: advancing access, affordability and appropriate use. 2014.

- 8.Moore T, Lee D, Konduri N, Kasonde L. Assuring the quality of essential medicines procured with donor funds: Washington, DC: World Bank; 2012.

- 9.Marten MG. The sustainability doctrine in donor-driven maternal health programs in Tanzania. In: Anthropologies of global maternal and reproductive health from policy spaces to sites of practice. Cham: Springer; 2022. pp.73–91.

- 10.Yenet A, Nibret G, Tegegne BA. Challenges to the availability and affordability of essential medicines in African countries: a scoping review. ClinicoEcon Outcomes Res. 2023;15:443–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Woodburn PA. Analysis of challenges of medical supply chains in sub-Saharan Africa regarding inventory management and transport and distribution. London: Westminster Business School; 2013.

- 12.Akuri L. Logistical challenges to supporting IDPs and best practices by humanitarian organizations in cameroon´s anglophone armed conflict: a case study of South West Region of Cameroon. Hanken School of Economics; 2020.

- 13.Onwughalu OO, Sylva W. Logistics in humanitarian supply chain processes for internally displaced persons (IDPs): a working model. IAR J Bus Manag. 2021;2(4).

- 14.Phuong C. Internally displaced persons and refugees: conceptual differences and similarities. Neth quart human rights. 2000;18(2):215–29. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deng F. Internally displaced persons: report of the representative of the UN secretary-general. Int’l J Refugee L. 1994;6:291. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deliver USAID. The logistics handbook: a practical guide for the supply chain management of health commodities. USAID deliver project, task order. 2011;1:174.

- 17.USAID. Key performance indicators. 2018.

- 18.Pasquet A, Messou E, Gabillard D, Minga A, Depoulosky A, Deuffic-Burban S, et al. Impact of drug stock-outs on death and retention to care among HIV-infected patients on combination antiretroviral therapy in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(10): e13414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tewuhibo D, Asmamaw G, Ayenew W. Availability of essential medicines in Ethiopia: a systematic review. J Community Med Health Care. 2021;6(1):1049. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fentie M, Fenta A, Moges F, Oumer H, Belay S, Sebhat Y, et al. Availability of essential medicines and inventory management practice in primary public health facilities of Gondar town, North West Ethiopia. J PharmaSciTech. 2015;4(2):54–6. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patil A, Shardeo V, Dwivedi A, Madaan J, Varma NJSP. Consumption. Barriers Sustain Humanitarian Med Supply Chains. 2021;27:1794–807. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anson A, Ramay B, de Esparza AR, Bero L. Availability, prices and affordability of the World Health Organization’s essential medicines for children in Guatemala. Glob Health. 2012;8:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Demessie MB, Workneh BD, Mohammed SA, Hailu AD. Availability of tracer drugs and implementation of their logistic management information system in public health facilities of Dessie, North-East Ethiopia. Integr Pharm Res Pract. 2020;9:83–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shewarega A, Dowling P, Necho W, Tewfik S, Yiegezu Y. Ethiopia: national survey of the integrated pharmaceutical logistics system. USAID/deliver project, task order. Arlington: 2015;4.

- 25.Bekele A, Kumsa W, Ayalew M. Assessment of inventory management practice and associated challenges of maternal, newborn, and child health life-saving drugs in public hospitals of southwest Ethiopia: a mixed-method approach. Integr Pharm Res Pract. 2022;11:139–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kefale AT, Shebo HH. Availability of essential medicines and pharmaceutical inventory management practice at health centers of Adama town. Ethiopia BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Health Mo. Assessment of the essential medicines kit-based supply system in Uganda. Ministry of Health Kampala; 2011.

- 28.Kebede O, Tilahun G, Feyissa D. Storage management and wastage of reproductive health medicines and associated challenges in west Wollega zone of Ethiopia: a mixed cross-sectional descriptive study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Munedzimwe FE. Medicine stock management at primary health care facilities in one South African province. University of Cape Town; 2018.

- 30.Munga M, Gitau T, Kimani L, Kariuki P, Ng’etich E. Factors influencing availability of tracer essential medicines in selected health facilities in Nyeri County, Kenya. Int J Community Med Public Health. 2021;8(3):1013–21. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Olutuase VO, Iwu-Jaja CJ, Akuoko CP, Adewuyi EO, Khanal V. Medicines and vaccines supply chains challenges in Nigeria: a scoping review. BMC Public Health. 2022;22:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beale J, Mashiri M, Chakwizira J, editors. Prospects for leveraging private sector logistics firms to support rural access to healthcare: some insights from Mozambique. In: Southern African Transport Conference. 2015.

- 33.Zuma SM, Modiba LM. Challenges associated with provision of essential medicines in the Republic of South Africa and other selected African countries. World J Pharm Res. 2019;8:1532–47. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mohammed S, Mengesha H, Hailu A. Integrated pharmaceutical logistic system in Ethiopia: systematic review of challenges and prospects. J Bio Med Open Access. 2020;1(2):113. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset used and analyzed during this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.