Abstract

Avian leukosis in China has spread from broiler chickens to the local breeds and commercial laying hens. Studying resistance to avian leukosis is important for disease-resistant breeding programs. Gene expression and different transcripts may affect immune function. In this study, we compared five naturally infected Rhode Island Red (RIR) hens carrying tumor with five uninfected individuals to explore avian leukosis virus subgroup J (ALV-J) induced differences in gene expression and alternative splicing (AS) in the liver, spleen caused. Analyses revealed 847, 80 differentially expressed genes (DEGs), along with 207, 167 differential alternative splicing genes (DASGs) in the liver, spleen respectively. Most differential splicing events involved exon skipping. Although most genes showed no significant expression changes, their protein spatial structures were altered by AS. In the liver, microtubule cytoskeleton-related functions were co-regulated by both gene expression and splicing, with CCSER2 and MAPT exhibiting the highest splicing frequency. In the spleen, splicing predominantly affected RNA-processing genes, where PKLR and SRSF7 functioned as key regulators. Notably, PKLR-interacting genes (THRSP, ADH1C, AQP3) were significantly downregulated in infected groups, potentially promoting viral replication and tumor proliferation. These findings demonstrate that AS contributes to the host response to ALV-J infection through multiple mechanisms, including protein structural remodeling and dysregulation of coordinated interaction networks. This study provides new insights into the genetic basis of ALV-J resistance in laying hens.

Keywords: Avian leukosis virus subgroup J, Laying hen, Gene expression, Alternative splicing

Introduction

Avian leukosis virus subgroup J (ALV -J) has become a widespread infectious disease in poultry farming owing to inadequate farm husbandry management, significantly impacting economic performance. Currently, there is no effective vaccine for ALV-J, and its control primarily relies on poultry flock decontamination. ALV-J was first identified in broiler chickens (Payne et al., 1992) and later became prevalent in laying hens and local chicken breeds (Cheng et al., 2010). Although ALV-J transmission has been controlled in laying hens than in broilers and local chicken breeds in China, achieving genetic resistance to ALV-J in laying hens remains challenging. High-throughput sequencing-based approaches have emerged as common tools for screening candidate ALV-J resistance genes. Several differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were previously identified in the liver (Yan et al., 2021), spleen and other immune tissues (Yang et al., 2022) of ALV-J- infected chickens; these genes participate in host innate immune responses and tumorigenic mechanisms following viral infection. In addition, studies on methylation modifications have demonstrated that hypomethylated genes contribute to regulatory pathways in ALV-J pathogenesis (Zhao et al., 2022). A recent single-cell transcriptome study of ALV-J-infected peripheral blood cells revealed modulatory roles of immune cell subpopulations during infection (Qu et al., 2022). However, post-transcriptional regulation in ALV-J infection has not yet been explored.

Alternative splicing (AS) is a biological process through which a single gene encodes multiple functionally distinct transcripts via selective removal or retention of exons during RNA maturation. This phenomenon is prevalent in animals (Kim et al., 2007), plants (Zhang et al., 2015) and microorganisms (Grutzmann et al., 2014). In humans, defective splicing contributes to cancer development (Venables et al., 2009) and genetic diseases (Xiong et al., 2015). Among domesticated animals, AS has been studied in dairy cows with mastitis (Wang et al., 2016), African swine fever (Sun et al., 2021), chicken Marek’s disease (Wang et al., 2021), and avian influenza (Fang et al., 2020). The relationship between AS and viral pathogenesis is well established, with transcript variants of immune pathway proteins can alter protein activity, thereby modulating viral replication (Marozin et al., 2008). For example, NOD-like receptor (NLR) family members undergo splicing level regulation, which modifies their activity during antiviral responses and promotes host cell death during viral infection (Zhao and Zhao, 2020). Therefore, the biological pathways and key candidate genes associated with AS-mediated anti-ALV-J responses require further exploration.

In this study, we used uninfected and naturally ALV-J-infected RIR hens to investigate the differences in gene expression in immune organs. In addition, we assessed coordinated changes between AS and immune gene expression to elucidate transcriptional and regulatory mechanisms across tissues following ALV-J infection. This approach aims to enhance our understanding of immune response characteristics to ALV-J in laying hens.

Materials and methods

Ethics approval

All samples were collected from chickens on a farm, and the experiment was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the China Agricultural University (issue number: AW11403202-1-31).

Sampling collection

Thirty-three-week-old female RIR with spontaneous ALV-J infections and uninfected chickens were obtained at Hebei Rongde Poultry Breeding Co. Ltd., Hebei, China. The ALV negative and positive groups were confirmed by virus isolation. PCR is employed for identification of infecting ALV subgroups and discrimination of other tumorigenic avian diseases. All ALV-J-positive chickens exhibited clinical symptoms of splenomegaly and hepatomegaly with tumor nodules (humanly euthanasia using physical method; cervical dislocation). From both groups, spleen and liver were collected independently, washed in RNase-free water, transferred to tissue-cryopreservation tubes, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until RNA extraction.

Virus isolation and identification

Plasma samples were aseptically collected and centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 12 min at 4°C to isolate, and leukocytes were isolated by inoculation into DF1 cells. Cell culture supernatants were tested for the ALV group-specific antigen (p27) using an ALV Antigen Test Kit (IDEXX, USA). S/P ratios to determine whether a test result was positive or negative. S/P ratios was greater than 0.2, it was regarded as positive, and S/P ratios was less than 0.2, it was regarded as negative.

Conventional PCR

PCR was performed to test the genomic DNA extracted using a TSINGKE TSP202-50 Trelief Hi-Pure Animal Genomic DNA Kit (Beijing Tsingke Biotech Co., Ltd.) from blood and tissue samples. Specific primers were designed to detect ALV-J according to previous studies (Smith et al., 1998) and were synthesized by the Beijing Genomics Institute (Beijing, China). Each reaction was performed in a total volume mixture of 20 μL consisting of 1 μL DNA as template, 0.5 μL each of primers, 10 μL 2 × EasyTaq PCR SuperMix, and 8 μL RNase-free ddH2O. The amplification protocol was as follows: 94°C for 5 min, followed by 30 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, 72°C for 1 min and a final extension at 72°C for 1 min. MDV, REV, ALV-A, ALV-B (Mo et al., 2021b) and ALV-K (Li et al., 2019) were detected to rule out potential infections with other pathogens. All specific primers can be found in Table S2.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was isolated from samples using the TRIzol extraction method and reverse transcribed into cDNA using a PrimeScript™RT reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (Takara biomedical technology (Beijing) Co., Ltd.). Relative quantitation of transcript and ALV-J was determined using quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) with TB Green Premix Ex Taq™ (Tli RNaseH Plus) (Takara biomedical technology (Beijing) Co., Ltd.). Specific primers were designed to detect ALV-J env relative expression according to previous studies(Qiu et al., 2018). The other primers’ sequence were designed based on mRNA sequences. The primers are descripted in Table S2.

RNA-Seq library preparation and sequencing

For RNA-Seq, all RNA samples with an RNA integrity number value >5.0 were selected for library construction. Genomic DNA and rRNA were removed, and mRNA was enriched using oligo (dT) magnetic beads and chemically fragmented into short fragments using a Fragmentation Buffer. The fragmented mRNA was used as a template and reverse-transcribed into the first cDNA, followed by the synthesis of the second cDNA. Subsequently, purification, end repair, the addition of the A-tail, and connection of the sequencing connectors were performed. Fragments of the desired length were selected and amplified by PCR. After constructing the library, its concentration and insert size were checked using the Agilent 2100. The effective concentration of the library was accurately quantified by qPCR to ensure the quality of the library, which was subsequently sequenced using an Illumina HiSeq 2500 instrument.

Quality assessment of raw sequences

Raw FASTQ sequences were assessed for quality using FastQC/0.11.9 (Qiu et al., 2018) to identify adaptor contamination and low-quality sequences. Fastp/0.20.1 (Hu et al., 2022) was used for filtering and reads, including adapters (adaptor contamination), reads with an unknown base (N) content greater than 5 %, and low-quality reads were removed. Subsequently, the filtered reads were mapped to the chicken reference genome (NCBI Gallus_gallus.GRCg6a) using HISAT2/2.2.1 (Yan et al., 2021).

Transcript abundance, gene-level estimates, and differential expression analysis

The featureCounts function in Subread/2.0.0 was used to count raw genes counts after mapping. The DESeq2 R package (Love et al., 2014) was used to study DEGs, treating the uninfective group as the reference. Genes with p adjust value < 0.05 and |log2fold change| ≥ 1 (Cheng et al., 2023) was defined to be DEGs.

AS analysis

We used the AS analyzer rMATS (Wang et al., 2024) to investigate differences in the isoforms of the same gene between the two groups. BAM alignment files were extracted to identify AS events and statistically significant differential AS events. Through statistical modeling of junction-spanning reads, rMATS characterizes five canonical AS patterns: SE (exon skipping), MXE (mutually exclusive exons), RI (intron retention), A5SS (alternative 5′ splicing), and A3SS (alternative 3′ splicing).

Functional enrichment of DEGs and DASGs

DAVID (https://david.ncifcrf.gov/) was used to provide further information about the GO annotation which were significantly enriched in the DEGs and DASGs. The functional domains and three-dimensional structural changes of these key genes were predicted using the SWISS-MODEL website (https://swissmodel.expasy.org/interactive), while their protein-protein interactions networks were analyzed via STRING.

Results

Clinical sample analysis by virus isolation and polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

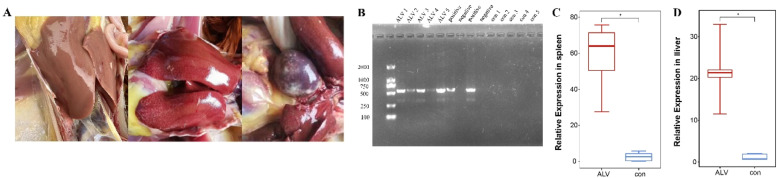

We randomly selected ALV-J-infected and uninfected individuals from a chicken flock. Dissection revealed hepatic and splenic tumor nodules in ALV-J-suspect chickens (Fig. 1A). ALV-J were diagnosed by virus isolation and confirmed by PCR and qRT-PCR (Fig. 1B-D), which was then used for RNA sequencing.

Fig. 1.

Samples PCR result and tissues characterization. (A) ALV-J positive group with tumor tissue (left: control group; middle and right: ALV-J positive group). (B) Samples diagnosis analysis based on the PCR. (C) The relative expression of ALV-J in spleen was measured by qRT-PCR (n = 5). (D) The relative expression of ALV-J in liver was measured by qRT-PCR (n = 5).

Transcriptome analysis and gene expression statistics

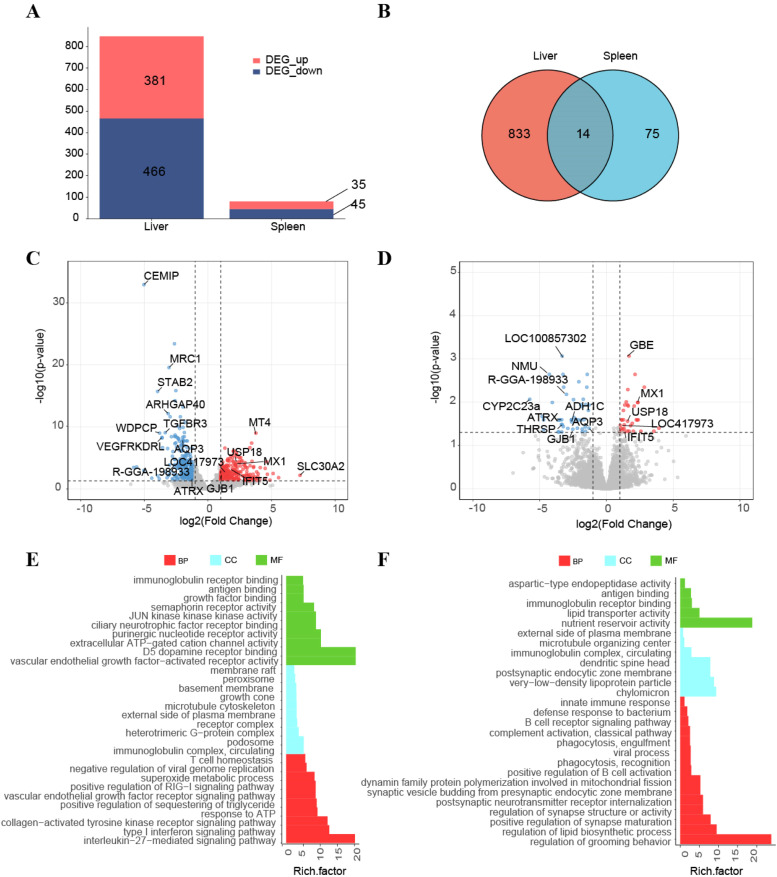

Total RNAs from all samples were used to construct RNA libraries. The positive and control groups yielded 55789053 and 61040018 clean reads with alignment rates of 88.43 % and 87.73 %, respectively (Table S1). Differential expression analysis identified 381 upregulated and 466 downregulated DEGs in liver, versus 35 upregulated and 45 downregulated DEGs in spleen (Fig. 2A). Fourteen co-regulated DEGs were in the two tissues (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

DEGs analysis of two tissues in ALV -J infected chicken. (A) The number of DEGs in the liver and spleen (n = 5). (B) Venn diagrams of DEGs in liver, spleen (n = 5). (C) Volcano plots presenting all DEGs between control and infection group in liver. FDR ≤ 0.05 and log2FoldChange ≥ 1 or ≤ −1. (D) Volcano plots presenting all DEGs between control and infection group in spleen. (E). Functional enrichment analyses GO terms of DESs in the liver. (F) Functional enrichment analyses GO terms of DESs in the spleen.

Transcriptomic profiling revealed distinct ALV-J infection-associated expression patterns in liver and spleen. Among the upregulated genes in liver, MT4, USP18 were infection-associated, while CEMIP, MRC1, AQP3 and STAB2 were significantly downregulated (Fig. 2C). In the spleen, GBE and MX1 were significantly induced, functionally diverse genes (NMU, LOC100857302, ATRX) exhibited suppression (Fig. 2D).

The Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analyses were conducted to explore the function of DEGs, revealing coordinated regulation of immune responses, cellular motility, and energy metabolism. In the liver, 87 GO terms (47 biological process (BP), 21 cellular component (CC), and 19 molecular function (MF)) were enriched in the immunoglobulin complex, circulating, microtubule cytoskeleton, type I interferon signaling pathway, JUN kinase kinase kinase activity (Fig. 2E). In the spleen, 27 GO terms (15 BP, seven CC, and five MF) were enriched for immunoglobulin receptor binding, antigen binding, positive regulation of B-cell activation, and phagocytic recognition (Fig. 2F).

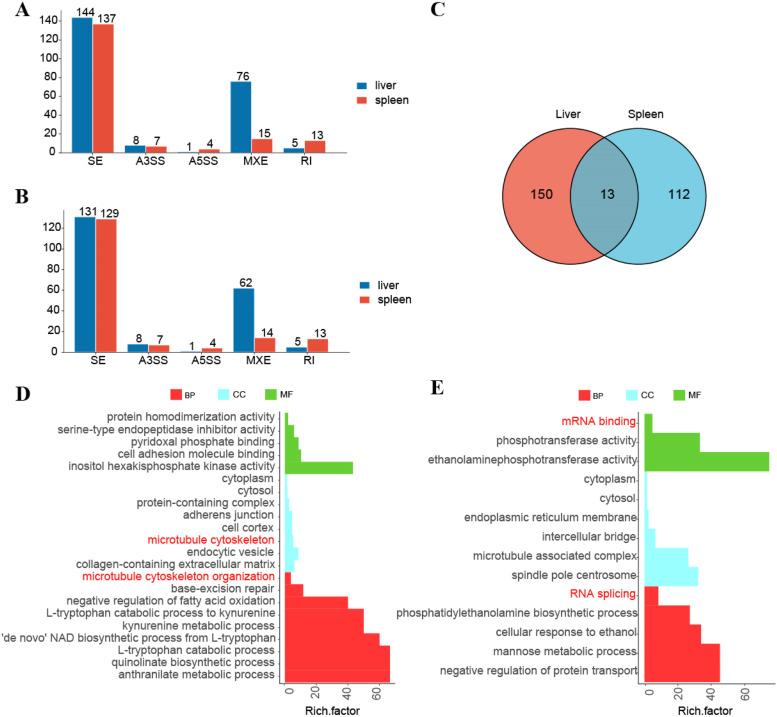

Identification of the AS events between control and infection samples

We identified 16322 AS events across 6612 genes in the liver, including 234 DAS events in 207 genes (adjusted p-value < 0.05) between ALV-J-negative and ALV-J-positive chickens(Fig. 3A). In the spleen, 23542 AS events occurred in 8034 genes, with 176 DAS events involving 167 genes (adjusted p-value < 0.05) (Fig. 3B). Thirteen genes exhibited conserved DASGs across both tissues, including MBNL1, MSRA, SRA1, PLBD2, USP48, ANKRD13D and others (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

DASGs analysis in liver and spleen. (A) The number of DAS events in the liver and spleen (n = 5). (B) The number of DASGs in the liver and spleen (n = 5). (C) Venn diagrams of DASGs in liver, spleen (n = 5). (D) Functional enrichment analyses GO terms of DASGs in the liver. (E) Functional enrichment analyses GO terms of DASGs in the spleen.

Functional annotation of tissue-specific AS genes revealed distinct regulatory programs (Fig. 3D-E). In liver, GO analysis revealed the significant regulation of 'de novo' NAD biosynthetic process from L-tryptophan, cytosol, cytoplasm, pyridoxal phosphate binding, L-tryptophan catabolic process to kynurenine, microtubule cytoskeleton, inositol hexakisphosphate kinase activity in the liver.

Spleen-specific AS events contribute to multifaceted regulatory programs encompassing RNA processing (splicing and mRNA binding), subcellular localization (endoplasmic reticulum membrane and cytosol), and metabolic functions (ethanolaminephosphotransferase activity).

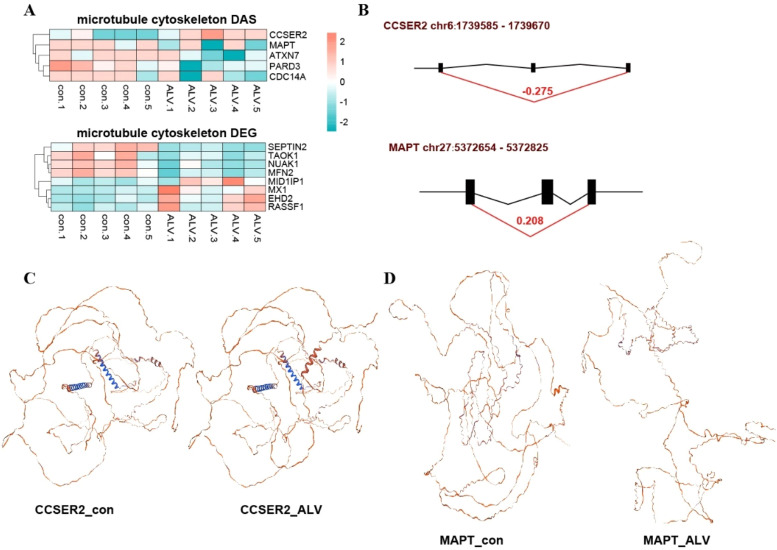

AS involving microtubule cytoskeleton in liver

Functional enrichment analysis of DEGs and DASGs revealed significant associations with microtubule cytoskeleton-related pathways. The heatmap analysis (Fig. 4A) clearly demonstrated distinct patterns between control and infected groups, showing DEGs including SEPTIN2, MX1, and TAOK1, along with AS events in CCSER2, MAPT, ATXN7, PARD3, and CDC14A (|ΔPSI| > 0.2). Notably, CCSER2 exhibited increased exon inclusion (chr6: 1739585-1739670) in infected samples compared to exon skipping in controls (Fig. 4B), resulting in full-length functional proteins with distinct structural conformations (Fig. 4C) contrasted with truncated isoforms containing premature termination codons in controls. Similarly, MAPT showed enhanced exon skipping (chr27: 5372654-5372825) under infection (Fig. 4B), generating shortened protein variants (Fig. 4D). These coordinated changes in microtubule cytoskeleton gene expression and splicing during ALV-J infection, suggesting that splicing modulation of key structural components like CCSER2 and MAPT may change isoform-specific functional.

Fig. 4.

Liver-specific alternative splicing events associated with microtubule cytoskeleton regulation. (A) DASGs and DEGs functionally enriched in microtubule cytoskeleton-related pathways. (B) Exon skipping patterns of CCSER2 and MAPT, showing infection-induced alternative splicing events. (C) Predicted three-dimensional protein structures of CCSER2 isoforms generated through AS. (D) Predicted three-dimensional protein structures of MAPT isoforms generated through AS.

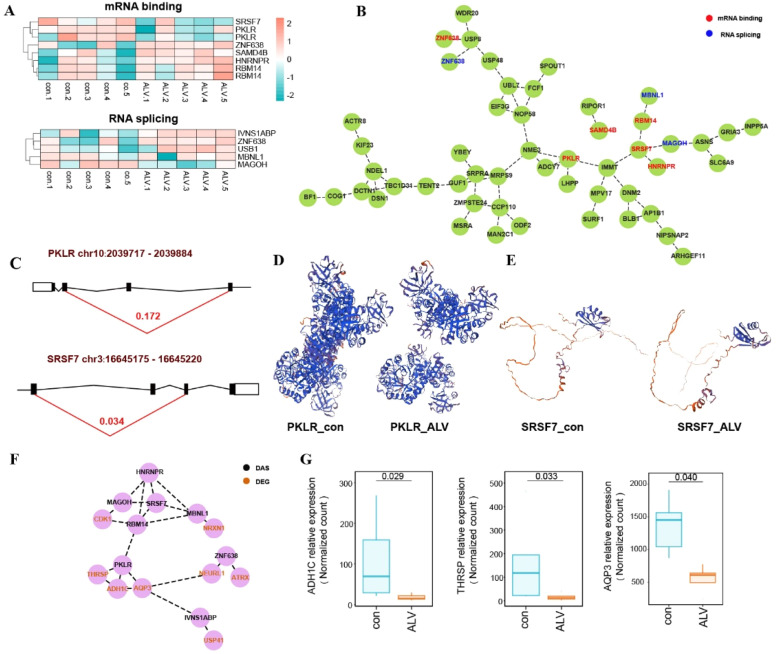

AS involving RNA regulatory proteins in spleen

Functional enrichment analysis of DASGs revealed significant associations with RNA splicing and mRNA binding pathways, suggesting that RNA regulatory genes themselves undergo AS events that may modulate downstream targets. Heatmap visualization of ΔPSI values (Fig. 5A) showed AS patterns between control and infected groups for key regulators, including splicing-related genes (IVNS1ABP, MBNL1, ZNF638, MAGOH, USB1) and mRNA-binding factors (RBM14, PKLR, SAMD4B, HNRNPR, SRSF7), with ZNF638 participating in both regulatory networks. Protein interaction analysis identified SRSF7 emerging as the central hub gene (Fig. 5B). Representative analyses in PKLR (chr10: 2039717-2039884) and SRSF7 (chr3: 16645175-16645220) revealed infection-specific exon skipping (Fig. 5C), resulting in PKLR isoform lacking critical functional domains (Fig. 5D) and SRSF7 variants potentially deficient in regulatory motifs (Fig. 5E). The protein-protein interaction network of DEGs and DASGs (Fig. 5F) suggests potential functional coordination, where transcriptional and splicing changes may jointly influence protein complexes. AQP3, THRSP, ADH1C were significantly downregulated in infected groups (Fig. 5G).

Fig. 5.

Spleen-specific AS events associated with RNA regulatory proteins. (A) Heatmap of DASGs involved in mRNA binding and RNA splicing. (B) Protein-protein interaction network of DASGs related to mRNA binding and RNA splicing. (C) Exon skipping patterns of PKLR and SRSF7. (D) Predicted three-dimensional structures of PKLR isoforms. (E) Predicted three-dimensional structures of SRSF7 isoforms. (F) Protein-protein interaction network of DASGs and DEGs. (G) The relative expression of interaction genes of PKLR.

Discussion

The high-laying period is the peak period for the onset and appearance of avian leukosis, it is more likely to be vertically transmitted. We chose RIR hens with organized lesion and unorganized lesion during peak laying period to investigate immune regulation of resistance to avian leukosis. In addition, our test population originated from the same batch, was raised in the same house, and exhibited 75 % ALV-J seropositivity prior to artificial insemination, indicating efficient viral transmission within this environment.

The DEGs common to the liver, spleen, included USP18, MX1, IFIT5. USP18 is a deISGylation gene that negatively regulates Type I IFN response by inhibiting JAK-STAT signaling (Malakhov et al., 2002), and its role in the immune response against viral infections is complex. Studies on viral infection by USP18 showed that knockdown of USP18 increased susceptibility to RNA viruses (Hou et al., 2021) and anti-cellular lesion effects, suggesting critical innate immune functions (Ritchie et al., 2004). However, the suppression of IFN by enhanced USP18 expression is a double-edged sword. Our experiments show elevated USP18 expression, the regulatory relationship with ALV-J viral replication remains undetermined. Furthermore, USP18 overexpression through inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α and LPS), impairing the IFN-I response and increasing infection risk (Honke et al., 2016). MX1 is an antiviral gene currently being studied in avian influenza (Alqazlan et al., 2021) and Newcastle virus (Schilling et al., 2018). In studies related to avian leukemia, the replication of ALV-J was found to be accompanied by MX1 gene expression (Mo et al., 2021a) and upregulated in infected lymphocytes (Dai et al., 2020), consistent with our findings of blocking viral RNA transcription. IFIT5 mediates innate immune response (Li et al., 2020), which can promote NF-κB activation by increasing the phosphorylation and activation of IKK (Zheng et al., 2015), and binding viral RNA (Ban et al., 2015). ALV-J suppresses IFIT5 to evade IFN-I responses (Ruan et al., 2021), yet breed-specific variations in local and commercial breeds (Li et al., 2017) support its candidacy for antiviral ability. PRLH which is enriched in this pathway showed significant hepatic upregulation in infected groups.

Significantly expressed genes with large fold changes in the liver and spleen are mostly associated with tumor growth and cell proliferation. We have identified two gene regulatory mechanisms associated with tumor growth: 1. Activation of oncogenes, which promote normal cells invasion and tumor growth. In normal conditions, oncogenes remain dormant. CCR10 signaling triggers tumor-promoting signaling such as PI3K/AKT and mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase, resulting in tumor cell growth (Korbecki et al., 2020; Mergia Terefe et al., 2022). 2. Inactivation of tumor suppressor genes accelerates malignant transformation of cells leading to tumorigenesis. AngII production levels are mediated by angiotensinogen (AGT), and they can be used as reliable biomarkers of increased cancer risk (Yapijakis et al., 2023). Angiogenesis is a key early step in tumor progression.

In this study, AS in the liver and spleen regulates ALV-J infection through distinct mechanisms. At the metabolic level in the liver, viruses such as HIV specifically activate the tryptophan-kynurenine pathway to suppress T-cell proliferation (Byakwaga et al., 2014), facilitating immune evasion. Structurally, viruses must traverse cytoplasmic barriers to reach specific compartments (e.g., the nucleus or viral replication factories). The microtubule network serves as a "cellular highway" for directed transport, while viral proteins can also bind microtubule-associated proteins to promote virion trafficking toward the cell membrane(Klingler et al., 2020), enhancing viral entry and intracellular replication. Our findings suggest that the microtubule cytoskeleton is co-regulated by DASGs and DEGs disrupts cytoskeletal stability and normal function.

CCSER2 is a microtubule plus-end-tracking protein localized at microtubule plus-ends; its deficiency disrupts centrosome positioning, impairs microtubule network polarization, and significantly reduces directional cell migration. In neuroblastoma, elevated CCSER2 expression correlates with improved patient survival, suggesting tumor-suppressive role (Ognibene et al., 2023). In this study, ALV-J infection induced structural alterations in CCSER2, including the addition of a coiled-coil domain and serine/proline-rich regions. These modifications may facilitate viral exploitation of cytoskeletal remodeling for viral transport and replication (Zang et al., 2025a) . The newly acquired domains could enhance CCSER2-viral protein interactions (e.g., viral kinases), positioning it as a critical host target for viral manipulation (Boudreault et al., 2019).

MAPT encodes microtubule-associated protein tau (Tau), a critical regulator of microtubule assembly, stabilization, and dynamics. Structurally, Tau comprises four domains: the N-terminal projection region (NTR), proline-rich region (PRR), microtubule-binding domain (MTBD), and C-terminal region. The MTBD of Tau consists of three or four repeat sequences that interact with the E-hook of microtubules, regulating microtubule stabilization and polymerization-depolymerization dynamics (Brandt et al., 2020). AS of exons 2, 3, and 10 generates six major isoforms with differential microtubule-binding affinities (Corsi et al., 2022). In this study, exon 10 skipping in MAPT, a region encoding the MTBD which translates into the second repeat sequence (R2 fragment) (Corsi et al., 2022) . Notably, the MTBD containing the R2 fragment exhibits enhanced microtubule-binding affinity (Andreadis et al., 1993), which may impair antigen presentation and dampening immune responses (Everts et al., 2014).

In the spleen, viruses achieve efficient replication through coordinately modulating host RNA processing, membrane systems, and metabolic networks. ALV-J infection alters host splicing machinery to generate functionally distinct splice variants, potentially facilitating viral mRNA processing while suppressing host mRNA splicing (De Maio et al., 2016). Concurrently, viral RNAs form ribonucleoprotein (RBP) complexes with mRNA-binding proteins to stabilize viral transcripts (Huang et al., 2017).

The PKLR gene encodes pyruvate kinase L/R, a key enzyme that not only participates in glycolysis and lipid metabolism (Chella Krishnan et al., 2021), but also indirectly modulates host immune responses through regulation of pyruvate metabolism. Additionally, PKLR plays a significant role in tumor metastasis. In this study, exon 9 skipping in PKLR may lead to the loss of catalytic domains or functional regions in PKL protein (Bianchi and Fermo, 2020), resulting in the absence of critical ATP-binding residues and reduced glycolytic efficiency. This metabolic disruption compromises energy homeostasis in immune cells (Liu et al., 2021). Downregulation of THRSP promotes tumor cell proliferation, migration, and invasion, whereas its overexpression suppresses tumor progression (Hu et al., 2021). Similarly, AQP3 knockdown significantly increases viral copy number and viral titer, while AQP3 overexpression inhibits viral replication, suggesting its role as a viral restriction factor (Wang et al., 2022). In contrast, high expression of ADH1C exerts tumor-promoting effects by enhancing the PHGDH/PSAT1/serine metabolic pathway, thereby increasing cancer cell proliferation, migration, and invasiveness (Li et al., 2022). This suggests that PKLR exon skipping-induced protein structural alterations may synergize with differential expression of other protein-interacting genes to influence disease outcomes.

SRSF7, a key member of the Serine/Arginine-rich (SR) protein family, regulates RNA splicing and gene expression through RNA-binding domains to modulate post-transcriptional processes (Haroon et al., 2022). Previous studies have linked SRSF7 AS to cancer progression, macrophage functional diversity, and tumor cell proliferation (Saijo et al., 2016) . Here, ALV-J infection induced exon 7 skipping in SRSF7, leading to partial deletion of the C-terminal RS-like domain. This structural alteration may disrupt splicing and translational regulation (Escudero-Paunetto et al., 2010), potentially enhancing viral protein synthesis while impairing host recognition of viral RNA and reducing pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion (Königs et al., 2020), collectively fostering a favorable environment for viral replication.

Conclusion

Transcriptome sequencing analysis revealed that the immune functions in the liver, spleen of laying hens infected with ALV-J were regulated through both gene expression and AS. Furthermore, we found that the different transcript isoforms in control and infected groups that may possess potential functions against ALV-J infection. Functional validation is required to determine the role of these genes in ALV-J infection. Overall, this study provided new insights into developing novel molecular targets for ALV-J resistance.

Data availability

All the pertinent data is presented in the manuscript and associated supplementary files. Raw Illumina sequences are submitted in NCBI’s Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database with bioproject ID PRJNA953514.

Disclosures

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

We are deeply grateful to all the participants involved in the study and all the research staff and students working on the project. This research was funded by the Biological Breeding-National Science and Technology Major Project (2023ZD04064), China Agriculture Research System (CARS-40), National Key R & D Program of China (2024YFD2000300), S&T Program of Hebei (21326303D), and Guizhou Provincial Key Technology R&D Program ([2023]004). This research is supported by High-performance Computing Platform of China Agricultural University.

Footnotes

The appropriate scientific section for the paper: Genetics and Genomics.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.psj.2025.105554.

Table S1. Statistical summary analysis of RNA-seq data.xlsx; Table S2. Primer used in study.xlsx; Figure S3. Viremia detection of ALV-A, ALV-B, MDV, REV, and ALV-K.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- Alqazlan N., Emam M., Nagy É., Bridle B., Sargolzaei M., Sharif S. Transcriptomics of chicken cecal tonsils and intestine after infection with low pathogenic avian influenza virus H9N2. Sci. Rep. 2021;11 doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-99182-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreadis A., Nisson P.E., Kosik K.S., Watkins P.C. The exon trapping assay partly discriminates against alternatively spliced exons. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:2217–2221. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.9.2217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ban T., Zhu J.-K., Melcher K., Xu H.E. Structural mechanisms of RNA recognition: sequence-specific and non-specific RNA-binding proteins and the Cas9-RNA-DNA complex. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2015;72:1045–1058. doi: 10.1007/s00018-014-1779-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi P., Fermo E. Molecular heterogeneity of pyruvate kinase deficiency. Haematologica. 2020;105:2218–2228. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2019.241141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudreault S., Roy P., Lemay G., Bisaillon M. Viral modulation of cellular RNA alternative splicing: a new key player in virus–host interactions? WIREs. RNA. 2019;10:e1543. doi: 10.1002/wrna.1543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt R., Trushina N.I., Bakota L. Much more than a cytoskeletal protein: physiological and pathological functions of the non-microtubule binding region of tau. Front. Neurol. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.590059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byakwaga H., Boum Y., Huang Y., Muzoora C., Kembabazi A., Weiser S.D., Bennett J., Cao H., Haberer J.E., Deeks S.G., Bangsberg D.R., McCune J.M., Martin J.N., Hunt P.W. The kynurenine pathway of tryptophan catabolism, CD4+ T-cell recovery, and mortality among HIV-infected Ugandans initiating antiretroviral therapy. J. Infect. Dis. 2014;210:383–391. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chella Krishnan K., Floyd R.R., Sabir S., Jayasekera D.W., Leon-Mimila P.V., Jones A.E., Cortez A.A., Shravah V., Péterfy M., Stiles L., Canizales-Quinteros S., Divakaruni A.S., Huertas-Vazquez A., Lusis A.J. Liver pyruvate kinase promotes NAFLD/NASH in both mice and humans in a sex-specific manner. Cell Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021;11:389–406. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2020.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng X., Li X., Liu Y., Ma Y., Zhang R., Zhang Y., Fan C., Qu L., Ning Z. DNA methylome and transcriptome identified key genes and pathways involved in speckled eggshell formation in aged laying hens. BMC. Genomics. 2023;24:31. doi: 10.1186/s12864-022-09100-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Z., Liu J., Cui Z., Zhang L. Tumors associated with Avian Leukosis Virus subgroup J in layer hens during 2007 to 2009 in China. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2010;72:1027–1033. doi: 10.1292/jvms.09-0564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corsi A., Bombieri C., Valenti M.T., Romanelli M.G. Tau Isoforms: gaining insight into MAPT alternative splicing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022;23 doi: 10.3390/ijms232315383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai M., Li S., Shi K., Liao J., Sun H., Liao M. Systematic identification of host immune key factors influencing viral infection in PBL of ALV-J infected SPF chicken. Viruses. 2020;12:114. doi: 10.3390/v12010114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Maio F.A., Risso G.., Iglesias N.G., Shah P., Pozzi B., Gebhard L.G., Mammi P., Mancini E., Yanovsky M.J., Andino R., Krogan N., Srebrow A., Gamarnik A.V. The Dengue Virus NS5 protein intrudes in the cellular spliceosome and modulates splicing. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escudero-Paunetto L., Li L., Hernandez F.P., Sandri-Goldin R.M. SR proteins SRp20 and 9G8 contribute to efficient export of herpes simplex virus 1 mRNAs. Virology. 2010;401:155–164. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everts B., Amiel E., Huang S.C.-C., Smith A.M., Chang C.-H., Lam W.Y., Redmann V., Freitas T.C., Blagih J., van der Windt G.J.W., Artyomov M.N., Jones R.G., Pearce E.L., Pearce E.J. TLR-driven early glycolytic reprogramming via the kinases TBK1-ikkɛ supports the anabolic demands of dendritic cell activation. Nat. Immunol. 2014;15:323–332. doi: 10.1038/ni.2833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang A., Bi Z., Ye H., Yan L. SRSF10 inhibits the polymerase activity and replication of avian influenza virus by regulating the alternative splicing of chicken ANP32A. Virus. Res. 2020;286 doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2020.198063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grutzmann K., Szafranski K., Pohl M., Voigt K., Petzold A., Schuster S. Fungal alternative splicing is associated with multicellular complexity and virulence: a genome-wide multi-species study. DNA Res. 2014;21:27–39. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dst038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haroon M., Afzal R., Zafar M.M., Zhang H., Li L. Ribonomics approaches to identify RBPome in plants and other eukaryotes: current progress and future prospects. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022;23:5923. doi: 10.3390/ijms23115923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honke N., Shaabani N., Zhang D.-E., Hardt C., Lang K.S. Multiple functions of USP18. Cell Death Dis. 2016;7:e2444. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2016.326. –e2444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou J., Han L., Zhao Z., Liu H., Zhang L., Ma C., Yi F., Liu B., Zheng Y., Gao C. USP18 positively regulates innate antiviral immunity by promoting K63-linked polyubiquitination of MAVS. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:2970. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-23219-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Q., Ma X., Li C., Zhou C., Chen J., Gu X. Downregulation of THRSP promotes hepatocellular carcinoma progression by triggering ZEB1 transcription in an ERK-dependent manner. J. Cancer. 2021;12:4247–4256. doi: 10.7150/jca.51657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L., Sammad A., Zhang C., Brito L.F., Xu Q., Wang Y. Transcriptome analyses reveal essential roles of alternative splicing regulation in heat-stressed holstein cows. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022;23 doi: 10.3390/ijms231810664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X., Zheng M., Wang P., Mok B.W.-Y., Liu S., Lau S.-Y., Chen P., Liu Y.-C., Liu H., Chen Y., Song W., Yuen K.-Y., Chen H. An NS-segment exonic splicing enhancer regulates influenza A virus replication in mammalian cells. Nat. Commun. 2017;8 doi: 10.1038/ncomms14751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim N., Alekseyenko A.V., Roy M., Lee C. The ASAP II database: analysis and comparative genomics of alternative splicing in 15 animal species. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D93–D98. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klingler J., Anton H., Réal E., Zeiger M., Moog C., Mély Y., Boutant E. How HIV-1 gag manipulates its host cell proteins: a focus on interactors of the nucleocapsid domain. Viruses. 2020;12:888. doi: 10.3390/v12080888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Königs V., de Oliveira Freitas Machado C., Arnold B., Blümel N., Solovyeva A., Löbbert S., Schafranek M., Ruiz De Los Mozos I., Wittig I., McNicoll F., Schulz M.H., Müller-McNicoll M. SRSF7 maintains its homeostasis through the expression of split-ORFs and nuclear body assembly. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2020;27:260–273. doi: 10.1038/s41594-020-0385-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korbecki J., Grochans S., Gutowska I., Barczak K., Baranowska-Bosiacka I. CC chemokines in a tumor: a review of pro-cancer and anti-cancer properties of receptors CCR8, CCR9, and CCR10 ligands. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21:7619. doi: 10.3390/ijms21207619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.-J., Wang Y., Yang C.-W., Ran J.-S., Jiang X.-S., Du H.-R., Hu Y.-D., Liu Y.-P. Genotypes of IFIH1 and IFIT5 in seven chicken breeds indicated artificial selection for commercial traits influenced antiviral genes. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2017;56:54–61. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2017.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T., Xie J., Liang G., Ren D., Sun S., Lv L., Xie Q., Shao H., Gao W., Qin A., Ye J. Co-infection of vvMDV with multiple subgroups of avian leukosis viruses in indigenous chicken flocks in China. BMC. Vet. Res. 2019;15:288. doi: 10.1186/s12917-019-2041-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S., Yang H., Li W., Liu J.-Y., Ren L.-W., Yang Y.-H., Ge B.-B., Zhang Y.-Z., Fu W.-Q., Zheng X.-J., Du G.-H., Wang J.-H. ADH1C inhibits progression of colorectal cancer through the ADH1C/PHGDH /PSAT1/serine metabolic pathway. Acta. Pharmacol. Sin. 2022;43:2709–2722. doi: 10.1038/s41401-022-00894-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.-J., Yin Y., Yang H.-L., Yang C.-W., Yu C.-L., Wang Y., Yin H.-D., Lian T., Peng H., Zhu Q., Liu Y.-P. mRNA expression and functional analysis of chicken IFIT5 after infected with Newcastle disease virus. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2020;86 doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2020.104585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z., Zhao J., Wang W., Zhu H., Qian J., Wang S., Que S., Zhang F., Yin S., Zhou L., Geng L., Zheng S. Integrative network analysis revealed genetic impact of pyruvate kinase L/R on hepatocyte proliferation and graft survival after liver transplantation. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2021;2021 doi: 10.1155/2021/7182914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love M.I., Huber W.., Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome. Biol. 2014;15:550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malakhov M.P., Malakhova O..A., Kim K.I., Ritchie K.J., Zhang D.-E. UBP43 (USP18) Specifically removes ISG15 from conjugated proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:9976–9981. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109078200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marozin S., Altomonte J., Stadler F., Thasler W.E., Schmid R.M., Ebert O. Inhibition of the IFN-β response in hepatocellular carcinoma by alternative spliced isoform of IFN regulatory factor-3. Mol. Ther. 2008;16:1789–1797. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mergia Terefe E., Catalan Opulencia M.J., Rakhshani A., Ansari M.J., Sergeevna S.E., Awadh S.A., Polatova D.S., Abdulkadhim A.H., Mustafa Y.F., Kzar H.H., Al-Gazally M.E., Kadhim M.M., Taherian G. Roles of CCR10/CCL27-CCL28 axis in tumour development: mechanisms, diagnostic and therapeutic approaches, and perspectives. Expert Rev. Mol. Med. 2022;24:e37. doi: 10.1017/erm.2022.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mo G., Fu H., Hu B., Zhang Q., Xian M., Zhang Z., Lin L., Shi M., Nie Q., Zhang X. SOCS3 Promotes ALV-J virus replication via inhibiting JAK2/STAT3 phosphorylation during infection. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021;11 doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2021.748795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mo G., Hu B., Wang G., Xie T., Fu H., Zhang Q., Fu R., Feng M., Luo W., Li H., Nie Q., Zhang X. Prolactin affects the disappearance of ALV-J viremia in vivo and inhibits viral infection. Vet. Microbiol. 2021;261 doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2021.109205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ognibene M., De Marco P., Amoroso L., Cangelosi D., Zara F., Parodi S., Pezzolo A. Multiple genes with potential tumor suppressive activity are present on chromosome 10q loss in neuroblastoma and are associated with poor prognosis. Cancers (Basel) 2023;15:2035. doi: 10.3390/cancers15072035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne L.N., Howes K.., Gillespie A.M., Smith L.M. Host range of Rous sarcoma virus pseudotype RSV(HPRS-103) in 12 avian species: support for a new avian retrovirus envelope subgroup, designated J. J. Gen Virol. 1992;73:2995–2997. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-73-11-2995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu L., Chang G., Li Z., Bi Y., Liu X., Chen G. Comprehensive transcriptome analysis reveals competing endogenous RNA networks during Avian Leukosis Virus, subgroup J-induced tumorigenesis in chickens. Front. Physiol. 2018;9:996. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.00996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu X., Li X., Li Z., Liao M., Dai M. Chicken peripheral blood mononuclear cells response to Avian Leukosis virus subgroup J infection assessed by single-cell RNA sequencing. Front. Microbiol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.800618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie K.J., Hahn C..S., Kim K.I., Yan M., Rosario D., Li L., de la Torre J.C., Zhang D.-E. Role of ISG15 protease UBP43 (USP18) in innate immunity to viral infection. Nat. Med. 2004;10:1374–1378. doi: 10.1038/nm1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruan Z., Chen G., Xie T., Mo G., Wang G., Luo W., Li H., Shi M., Liu W., Zhang X. Cytokine inducible SH2-containing protein potentiate J subgroup avian leukosis virus replication and suppress antiviral responses in DF-1 chicken fibroblast cells. Virus. Res. 2021;296 doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2021.198344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saijo S., Kuwano Y., Masuda K., Nishikawa T., Rokutan K., Nishida K. Serine/arginine-rich splicing factor 7 regulates p21-dependent growth arrest in colon cancer cells. J. Med. Invest. 2016;63:219–226. doi: 10.2152/jmi.63.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schilling M.A., Katani R.., Memari S., Cavanaugh M., Buza J., Radzio-Basu J., Mpenda F.N., Deist M.S., Lamont S.J., Kapur V. Transcriptional innate immune response of the developing chicken embryo to Newcastle disease virus infection. Front. Genet. 2018;9:61. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2018.00061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith L.M., Brown S..R., Howes K., McLeod S., Arshad S.S., Barron G.S., Venugopal K., McKay J.C., Payne L.N. Development and application of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests for the detection of subgroup J avian leukosis virus. Virus. Res. 1998;54:87–98. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1702(98)00022-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun H., Niu Q., Yang J., Zhao Y., Tian Z., Fan J., Zhang Z., Wang Y., Geng S., Zhang Y., Guan G., Williams D.T., Luo J., Yin H., Liu Z. Transcriptome profiling reveals features of immune response and metabolism of acutely infected, dead and asymptomatic infection of African Swine Fever virus in pigs. Front. Immunol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.808545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venables J.P., Klinck R.., Koh C., Gervais-Bird J., Bramard A., Inkel L., Durand M., Couture S., Froehlich U., Lapointe E., Lucier J.-F., Thibault P., Rancourt C., Tremblay K., Prinos P., Chabot B., Elela S.A. Cancer-associated regulation of alternative splicing. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2009;16:670–676. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Bi Z., Dai K., Li P., Huang R., Wu S., Bao W. A functional variant in the aquaporin-3 promoter modulates its expression and correlates with resistance to Porcine epidemic virus infection in Porcine intestinal epithelial cells. Front. Microbiol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.877644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.G., Ju Z..H., Hou M.H., Jiang Q., Yang C.H., Zhang Y., Sun Y., Li R.L., Wang C.F., Zhong J.F., Huang J.M. Deciphering transcriptome and complex alternative splicing transcripts in mammary gland tissues from cows naturally infected with Staphylococcus aureus mastitis (MFW te Pas, Ed.) PLoS. ONE. 2016;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Xie Z., Kutschera E., Adams J.I., Kadash-Edmondson K.E., Xing Y. rMATS-turbo: an efficient and flexible computational tool for alternative splicing analysis of large-scale RNA-seq data. Nat. Protoc. 2024;19:1083–1104. doi: 10.1038/s41596-023-00944-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Zheng G., Yuan Y., Wang Z., Liu C., Zhang H., Lian L. Exploration of alternative splicing (AS) events in MDV-infected chicken spleens. Genes. 2021;12:1857. doi: 10.3390/genes12121857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong H.Y., Alipanahi B.., Lee L.J., Bretschneider H., Merico D., Yuen R.K.C., Hua Y., Gueroussov S., Najafabadi H.S., Hughes T.R., Morris Q., Barash Y., Krainer A.R., Jojic N., Scherer S.W., Blencowe B.J., Frey B.J. RNA splicing. The human splicing code reveals new insights into the genetic determinants of disease. Science. 2015;347 doi: 10.1126/science.1254806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Y., Zhang H., Gao S., Zhang H., Zhang X., Chen W., Lin W., Xie Q. Differential DNA methylation and gene expression between ALV-J-positive and ALV-J-negative chickens. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021;8 doi: 10.3389/fvets.2021.659840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang T., Qiu L., Bai M., Wang L., Hu X., Huang L., Chen G., Chang G. Identification, biogenesis and function prediction of novel circRNA during the chicken ALV-J infection. Anim. Biotechnol. 2022;33:981–991. doi: 10.1080/10495398.2020.1856125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yapijakis C., Gintoni I., Charalampidou S., Angelopoulou A., Papakosta V., Vassiliou S., Chrousos G.P. Angiotensinogen, angiotensin-converting enzyme, and chymase gene polymorphisms as biomarkers for basal cell carcinoma susceptibility. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2023;1423:175–180. doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-31978-5_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zang J.L., Gibson D.., Zheng A.-M., Shi W., Gillies J.P., Stein C., Drerup C.M., DeSantis M.E. CCSer2 gates dynein activity at the cell periphery. J. Cell. Biol. 2025;224 doi: 10.1083/jcb.202406153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C., Yang H., Yang H. Evolutionary character of alternative splicing in plants. Bioinform. Biol. Insights. 2015;9s1 doi: 10.4137/BBI.S33716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Q., Yao Z., Chen L., He Y., Xie Z., Zhang H., Lin W., Chen F., Xie Q., Zhang X. Transcriptome-wide dynamics of m6A methylation in tumor livers induced by ALV-J infection in chickens. Front. Immunol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.868892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao C., Zhao W. NLRP3 Inflammasome—A key player in antiviral responses. Front. Immunol. 2020;11:211. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng C., Zheng Z., Zhang Z., Meng J., Liu Y., Ke X., Hu Q., Wang H. IFIT5 positively regulates NF-κb signaling through synergizing the recruitment of iκb kinase (IKK) to TGF-β-activated kinase 1 (TAK1) Cell. Signal. 2015;27:2343–2354. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2015.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All the pertinent data is presented in the manuscript and associated supplementary files. Raw Illumina sequences are submitted in NCBI’s Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database with bioproject ID PRJNA953514.