Abstract

The clustering of tandem mass spectra (MS/MS) is a crucial computational step to de-duplicate repeated acquisitions in data dependent experiments. This technique is essential in untargeted metabolomics, particularly with high-throughput mass spectrometers capable of generating hundreds of MS/MS spectra per second. Despite advancements in MS/MS clustering algorithms in proteomics, their performance in metabolomics has not been extensively evaluated due to the lack of database search tools with false discovery rate control for molecule identification. To bridge this gap, this study introduces the MS1-Retention Time (MS-RT) method to assess MS/MS clustering performance in metabolomics datasets. Here, we validate MS-RT by comparing MS-RT to established proteomics clustering evaluation approaches that utilize database search identifications. Additionally, we evaluate the performance of several MS/MS clustering tools on metabolomics datasets, highlighting their advantages and drawbacks. This MS-RT method and MS/MS clustering tool benchmarking will provide valuable real world practical recommendations for tools and sets the stage for future advancements in metabolomics MS/MS clustering.

Keywords: Tandem Mass Spectrometry, Benchmark Clustering, Metabolomics, Purity, Completeness, MS-RT Method, Clustering Tools

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Modern mass spectrometers are capable of measuring tens of thousands of tandem mass spectra (MS/MS) spectra in an hour. Especially on large cohort samples, data-dependent acquisition creates repeated acquisitions of peptides (in bottom-up proteomics) and small molecules (in metabolomics)1. Despite this immense data generation capability, the development and application of MS/MS clustering algorithms in metabolomics have remained relatively underexplored. MS/MS clustering addresses key challenges in metabolomics workflows, such as reducing data redundancy caused by repeated acquisitions of the same molecule, consolidating spectra into consensus clusters for efficient molecule identification, and improving the handling of large-scale datasets. By simplifying complex spectral data, clustering enhances computational efficiency, facilitates downstream analysis like spectral library matching, and improves visualization and interpretation of metabolomics results2 (See SI Figure 1). Furthermore, improvements and innovations in clustering algorithms can lead to significant differences in clustering performance3.

Thus, the ability to assess the performance of MS/MS clustering approaches is key to determining the appropriate state of the art computational tool. When evaluating clustering approaches, metrics can broadly be categorized into internal (e.g., Silhouette Score4, Davies-Bouldin Index5) and external (e.g., Adjusted Rand Index6, Normalized Mutual Information7). While internal metrics are a useful tool for assessing the performance of MS/MS clustering, they can lead to biased evaluation because clustering algorithms are often specifically designed to optimize certain internal similarity metrics. Using these same metrics for evaluation introduces bias, as the algorithms may appear to perform well than others simply due to alignment with the evaluation criteria. In contrast, external metrics use domain knowledge to assess clustering outcomes against an established ground truth.

Among these external metrics, purity and completeness stand out as critical metrics for assessing clustering performance. Purity quantifies the homogeneity of clusters by determining the fraction of the largest class within a cluster - providing a sense of how accurately the clustering algorithm has grouped similar items together. Completeness, on the other hand, evaluates the extent to which all members of a true class are assigned to the same cluster. Completeness measures an algorithm’s ability to ensure that all elements belonging to a particular group are clustered together, reflecting the clustering method’s capacity to capture the entirety of natural groupings within the data.

These purity and completeness measures have been effectively used to evaluate and compare clustering techniques in proteomics3,8. This evaluation has been made possible because bottom-up proteomics has access to computational techniques for independent and error controlled (via the false discovery rate estimation (FDR) using the target-decoy strategy9) identifications of the original unclustered MS/MS spectra. However, in mass spectrometry-based metabolomics, FDR controlled identifications are not currently practical – limiting the ability of the field to assess MS/MS clustering of metabolomics data using the same techniques as proteomics. To overcome this limitation, we introduce a retention time-based method, called MS-RT, to assess the correctness of MS/MS clustering in metabolomics. To validate the MS-RT method, we have used proteomics datasets where well-established MS/MS evaluation techniques do exist. Specifically, we used database search results of proteomics datasets with FDR estimation to demonstrate that MS-RT clustering evaluations were consistent. Finally, we use MS-RT to evaluate the performance of several MS/MS clustering tools in metabolomics and highlight the differences in the clustering performance of MS/MS datasets across different data sizes.

Methods

Dataset preparation and preprocessing

We used two public ProteomeXchange10,11 datasets, PXD023047 and PXD021518, to evaluate the MS-RT method compared to traditional database benchmarking. PXD023047, acquired from Arabidopsis thaliana, was generated using the Q Exactive HF instrument and consists of 109,333 MS/MS spectra from 18 files. PXD021518, also from Arabidopsis thaliana, was acquired using the Q Exactive HF-X instrument, resulting in 286,410 MS/MS spectra from 32 files. The detailed information about sample acquisition, processing, and instrument parameter settings can be found in the original publications.

Dataset PXD000561 was used to evaluate the consistency of the proposed N10 metric as a proxy for clustering completeness, alongside the commonly used completeness metric in proteomics, which is not available for metabolomics datasets. This dataset was generated using the LTQ Orbitrap instrument and consists of 24,870,542 MS/MS spectra from 2212 files.

For metabolomics, we used three public MassIVE datasets: MSV000081981, MSV000093033, and MSV000080554. MSV000081981, obtained from human stool samples, was generated using the maXis impact HD instrument and consists of 7,838,866 MS/MS spectra from 2307 files. MSV000093033, obtained from algae strains, was generated using the Q Exactive HF instrument and includes 2,010,711 MS/MS spectra from 71 files. MSV000080554, part of the NIH NPAC ACONN Natural Products Standards project, comprises 390,746 MS/MS spectra derived from 2,179 chemical standards. These data were generated using untargeted LC-MS/MS in positive ion mode, with each LC-MS run containing 8 pooled standards.

All the RAW data files from Thermo datasets were converted to MGF and mzML files using the ThermoRawFileParser12 software (version 1.4.2) with default parameter settings. The rest of the public datasets were already provided in the converted formats. A summary of the dataset characteristics is available in Table 1.

Table 1 –

Dataset List Used for Evaluation in this Manuscript

| Datasets | Type | Instrument | No. MS/MS | No. Files |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PXD023047 | Proteomics | Q Exactive HF | 109,333 | 18 |

| PXD021518 | Proteomics | Q Exactive HF-X | 286,410 | 32 |

| PXD000561 | Proteomics | LTQ Orbitrap | 24,870,542 | 2212 |

| MSV000081981 | Metabolomics | maXis impact HD | 7,838,866 | 2307 |

| MSV000093033 | Metabolomics | Q Exactive HF | 1,005,355 | 71 |

| MSV000080554 | Metabolomics | Bruker q-TOF | 390,746 | 275 |

Database Search Method (DB-Search)

We used MS-GF+13 (version 2023.01.12) to perform database searching on all proteomics datasets. For datasets PXD021518 and PXD023047, the precursor tolerance was set to 10 ppm and 20 ppm respectively, maximum 2 modifications (NumMods = 2) per peptide were allowed, including fixed carbamidomethyl cysteine modification and variable methionine oxidation, using trypsin as the enzyme identifier. These settings are consistent with the previous proteomics benchmarking publication by Xiyang et al.14 Both PXD023047 and PXD021518 were searched against the Arabidopsis thaliana database downloaded from https://ftp.uniprot.org/pub/databases/uniprot/current_release/knowledgebase/reference_proteomes/Eukaryota/UP000006548/UP000006548_3702.fasta.gz in a target-decoy manner. PSMs were filtered to 1% FDR at the PSM level.

MS-RT method

MS/MS spectra that fall within a precursor tolerance and retention time window were treated as originating from the same molecule. MS/MS pairs were found using MS-RT with a 0.01 m/z precursor mass tolerance and within 65 seconds in the retention time for proteomics datasets. For metabolomics datasets a 0.01 m/z precursor mass tolerance and 30 seconds retention time window was applied. Cross-file retention time alignment was not allowed in this paper. On one hand, although there are methods in the literature15,16 that can align retention times across different runs to some extent, these methods are often imprecise and challenging in many cases. On the other hand, we aim for our benchmarking pipeline to be general and capable of handling all types of datasets and different instruments. For each cluster, a graph was created based on the matched MS/MS spectra pairs using MS1 and retention time tolerance for benchmarking based on the connected component in the graph. (See Method Benchmark metrics).

Benchmark metrics

The metrics for benchmarking clustering methods can be mainly categorized into two classes: internal and external metrics. Internal metrics, like the Silhouette Score4 and Davies-Bouldin Index5, assess clustering quality based on the data itself, without ground truth. External metrics, such as the Adjusted Rand Index6 and Normalized Mutual Information7, compare clustering results to true labels.

For MS/MS spectra clustering, external evaluation is preferred. For example, MS/MS spectra from two different molecules may appear similar and receive a high score under some internal metrics. In such cases, internal metrics will overestimate the results. Additionally, external metrics can leverage domain knowledge, ensuring that the clustering results correspond to biochemical ground truth. However, because for metabolomics datasets there are no established strategies to annotate the true labels with FDR control, we propose custom metrics for external evaluation which consider both the accuracy and completeness11,17.

To measure the performance of single cluster results we used the purity8,18 metric for DB-Search and adopted the same concept into the MS-RT method. For DB-Search, the purity is defined the same as the commonly used way in the literature, which is the largest fraction of spectra that have the same annotated peptide. Let denote the number of the most frequently annotated peptide in the i-th cluster and be the number of total spectra in that cluster. Then, the purity of the i-th cluster can be expressed mathematically as:

| (1) |

For MS-RT, we lack annotated true peptide labels for each spectrum. Instead, we used the MS1 mass and retention time to identify spectrum pair matches within each experimental LC-MS file. Here, an LC-MS file refers to data generated from a single chromatographic and mass spectrometric analysis. In this case, we define the purity for each single file as the fraction of the largest connected component in the cluster. Let denote the number of spectra in the largest connected component for in the i-th cluster and be the total number of spectra in the i-th cluster from .

| (2) |

Assume in the i-th cluster, the spectra are from a total number of distinct files. Then we define the purity for the i-th cluster as the average purity of each file.

| (3) |

We used the average purity of all the clusters to measure the accuracy of the clustering tools for both DB-Search and MS-RT.

Besides that, there is another important aspect we want to measure for clustering tools. On the one hand we want show the correctness of each cluster, on the other hand we also want to know how complete each clustering tool performed. In other words, we want that spectra belonging to the same peptide or molecule are all in a single cluster in the ideal scenario. However, purity will not capture these aspects, because large clusters can be split into small clusters while still having the same or better purity for each of the small clusters as the large one. Here we get inspiration from the N10 metric from genomics19 and adopt the same concept into our evaluation metrics. The N10 for clustering evaluation is defined as the size of the smallest cluster at 10% of the total dataset size (sort the clusters from the largest to smallest first). Note that a suitable dataset proportion, i.e. 10% in our case, is necessary, as for many datasets a relatively low number of spectra can be successfully clustered.

In addition to purity and the N10 value, we also considered another important aspect of clustering: the number of spectra that are clustered. Here, the number of clustered spectra is defined as the number of spectra that are in clusters with a size equal to or larger than two. This is particularly significant for metabolomics datasets, where some clustering tools may only cluster a small portion of the dataset. Since clustering tools can only cluster high-confidence similar spectra and leave the rest as singletons, resulting in high cluster purity, the number of clustered spectra serves as an additional dimension to supplement purity for a more rigorous evaluation. Under some circumstances, such as in small datasets where different clustering tools may yield the same N10 value, the number of clustered spectra might provide a more intuitive evaluation. In this paper, we used the percentage of clustered spectra to present this metric in a standardized manner. Denote as the number of clustered spectra, as the number of total spectra in the dataset, the percentage of clustered spectra can be mathematically expressed as:

| (4) |

Parameters of Clustering Tools Evaluated

We mainly benchmark on the following three different clustering algorithms: MS-Cluster1, MaRacluster8, and Falcon11. Table 2 lists an overview of the parameters of each algorithm that was iterated during the evaluation. The parameter ranges were based on recommendations from their original publications and pushed to the extreme limit to explore increased clustering sensitivity. Detailed results of the extended parameter ranges are provided in the Supplementary Information.

Table 2 –

Parameter settings for MS-Cluster, MaRaCluster and Falcon.

| Algorithms | Parameter | Values |

|---|---|---|

| MS-Cluster | mixture-prob | 0.00001,0.0001,0.001,0.005,0.01,0.05,0.1 |

| MaRaCluster | p-value | −5, −10, −15, −20, −25, −30 |

| Falcon | eps | 0.1, 0.15, 0.2, 0.25, 0.3 |

MS-Cluster

Different mixture-prob for the MS/MS spectra were used to run MS-Cluster: 0.00001, 0.0001, 0.001, 0.005, 0.01, 0.05, 0.1. The mass tolerance settings for precursor mass and MS2 fragmentation were 20ppm and 0.05 Da respectively. Precursor charges were read from the input files and the minimum cluster size is set to 2. The remaining settings were left at their default values.

MaRacluster

The precursor mass tolerance for MaRaCluster was set to 20 ppm, with a p-value of −5.0. Clustering thresholds of −30.0, −25.0, −20.0, −15.0, −10.0, and −5.0 were used to produce different cluster files. The remaining settings were left at their default values.

Falcon

The precursor mass and MS2 fragmentation for Falcon were set to 20 ppm and 0.05 Da respectively. The maximum cosine distances (eps) between two spectra for them to be considered as neighbors of each other during DBSCAN clustering stage were set to 0.1, 0.15, 0.2, 0.25, and 0.3 for different benchmarking rounds. The remaining settings were left at their default values.

Consistency Verification Method

The same proteomics dataset was clustered based on the same clustering tool and evaluated using both the DB-Search and MS-RT methods under our proposed metrics (average purity and N10 value). Only the clusters containing more than 2 spectra were taken into account and for DB-Search method only the identified spectra were considered in benchmarking.

Corteva Mass Spectrometry Experimental Methods

Corteva actinomycetes were cultured in six different media types in 24-well plates. At the end of culture, an equal volume of EtOH was added, extracts filtered and pooled. Untargeted metabolomics data was acquired on an Exploris 240 mass spectrometry with Thermo Vanquish UPLC system (San Jose, CA). HPLC settings: Waters Cortecs column, 1.6 mm, 2.1 X 50 mm, solvent A = 0.1% formic acid in water, B = 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile, flow rate 0.4 ml/min. Two uL of the pooled extract was injected and eluted with 5% B for 1 min, followed by linear gradient to 100% B in 10 min. DDA settings: MS1 resolution 60000 (profile), MS2 resolution 30000 (centroid); scan range 150 – 2000 m/z, cycle time 0.6 second, dynamic exclusion times 1 and exclusion duration 2.5 second. Normalized collision was conducted in HCD (20, 40 and 60).

Validation of MS-RT Methods with Chemical Standards in Metabolomics

To validate the MS-RT method in the context of metabolomics, we utilized data from the NIH NPAC ACONN Natural Products Standards project (MSV000080554), which contains 390,746 MS/MS scans from 2,179 chemical standards. This dataset was generated using untargeted LC-MS/MS in positive ion mode. We manually annotated the results by matching the precursor m/z values to the known set of 8 pooled chemical standards present in each LC-MS run – searching for M+H, M+Na, M+NH4 adducts with a 50 ppm tolerance on the precursor m/z. We clustered the full dataset with MS-Cluster. We estimated the purity of clusters using manual annotation of the standards in a similar fashion as for proteomics. For MS-RT purity estimation, we adjusted the methodology for the chemical standards by simulating as if all standards were measured in a single LC-MS run. We chose this because in the original construction of the chemical standard pools for LC-MS analysis, 8 standards were present in each LC-MS analysis. This number of molecules within a single run is significantly less complex than normal LC-MS runs of real samples and by design would be unlikely to have any isobaric compounds that MS-RT could use to assess purity.

Results

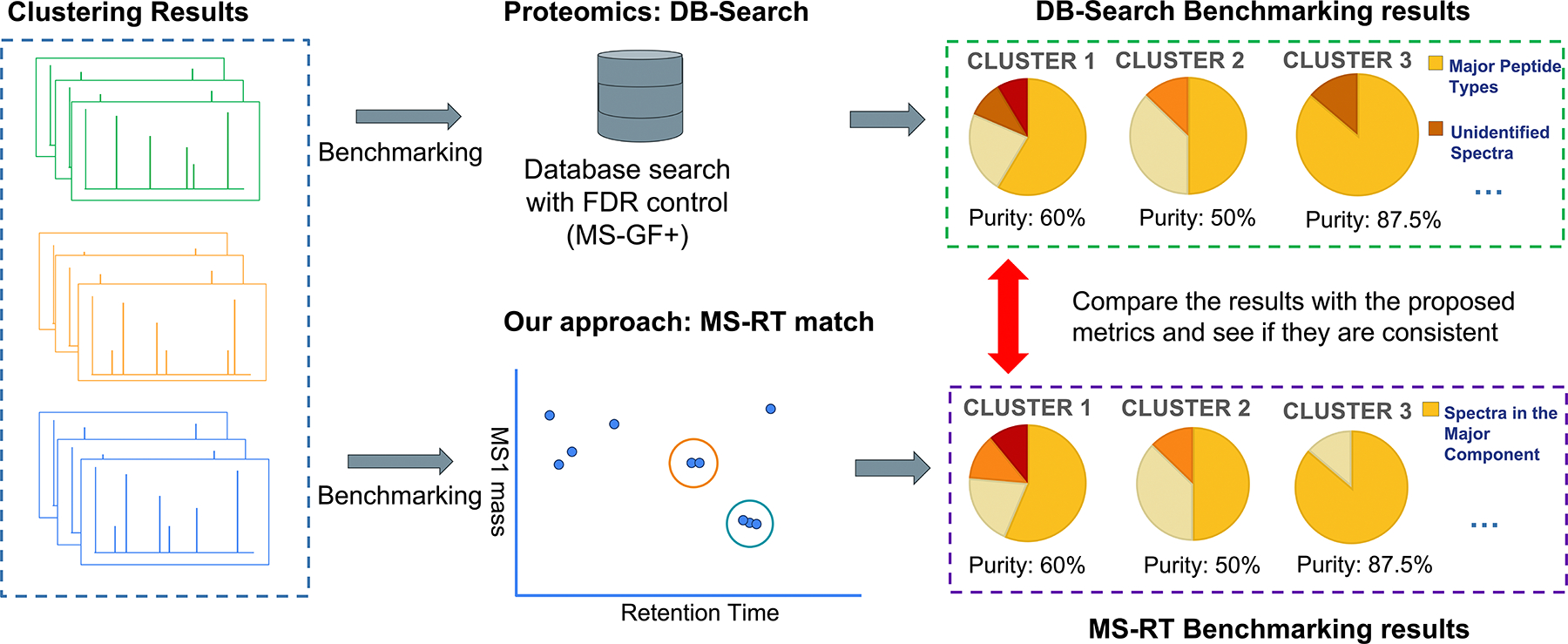

Evaluating Consistency of MS-RT and DB Search for Purity

Here we introduce the MS-RT method to assess the performance of MS/MS clustering. Additionally, we validate the MS-RT approach to estimate clustering purity in proteomics datasets by comparing to current state of the art approaches for evaluating clustering performance (Figure 1). While our overarching goal is to create a metric to evaluate clustering of MS/MS spectra in metabolomics, we validate the MS-RT method in proteomics because there exists a well-established methodology for clustering evaluation. Specifically, we use MS/MS database search tools (DB-Search) with FDR estimation using the target-decoy strategy to assign confident peptide identifications to bottom-up MS/MS spectra13 to measure cluster purity.

Figure 1 – Validation Approach for MS-RT Method –

This is the overarching validation workflow to compare the clustering evaluation results of DB-Search against MS-RT. In this approach, both the DB-Search and MS-RT methods are employed to evaluate clustering results from the same proteomics dataset using the same clustering approach. The goal is to determine if the purity measures for the same cluster are consistent between the DB-Search and MS-RT approaches—that is, the purity assessments for the same cluster should be nearly identical when assessed by both methods. Once evaluated using MS-RT and DB-Search for each cluster, the purity assessments are compared to assess the consistency.

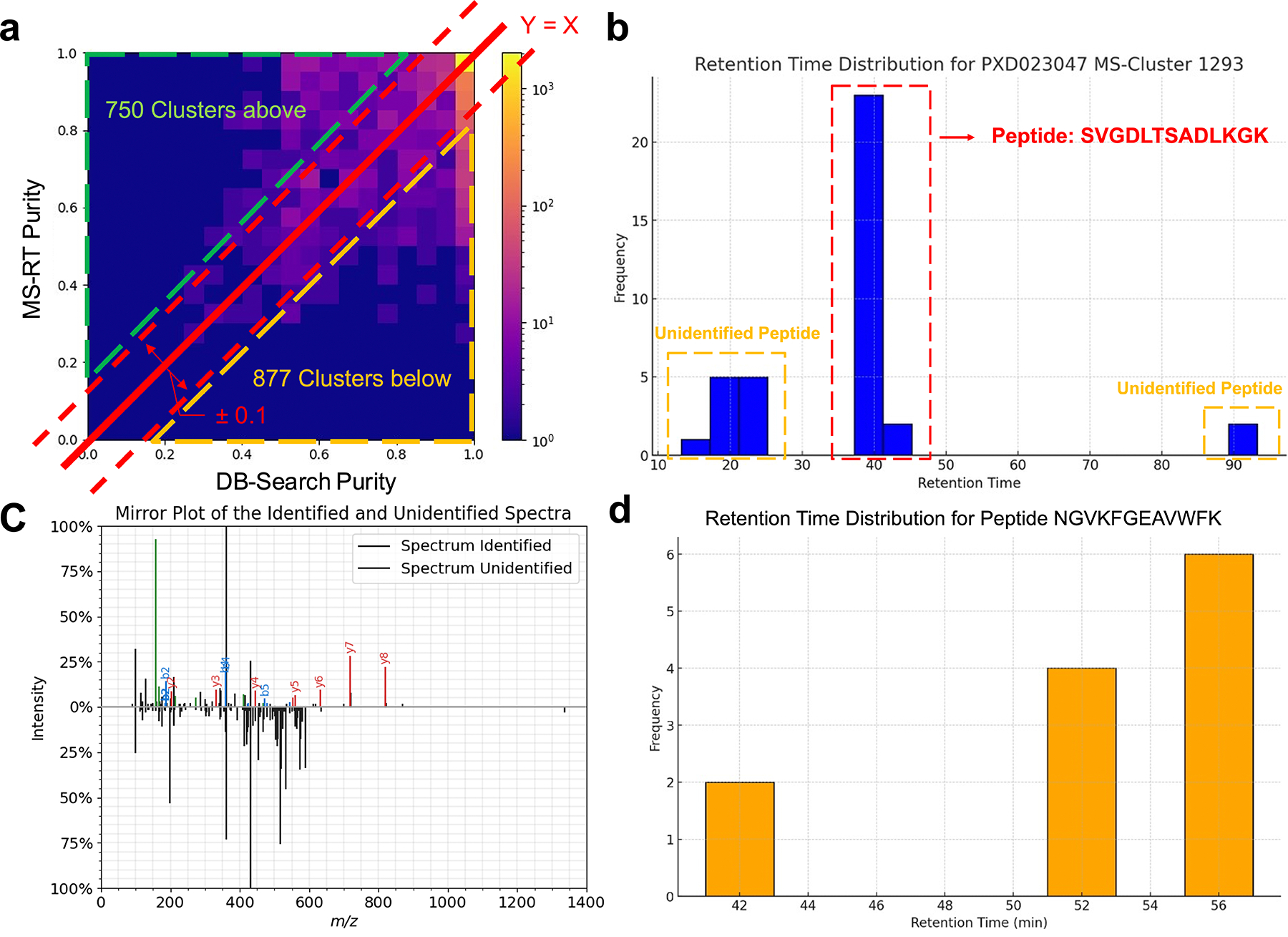

We used two bottom-up proteomics datasets10,20 to evaluate the consistency of MS/MS clustering measurements between MS-RT and traditional database search-based methods (DB-Search). We chose these datasets because they were used previously for the evaluation of MS/MS clustering14. The first dataset (PXD023047) is a bottom-up proteomics dataset which consists of 20 LC-MS/MS runs on a Q-Exactive Mass Spectrometer totaling 109,333 MS/MS spectra. We used MS-Cluster1 to produce a clustering of this data to evaluate the consistency of MS-RT and DB-Search. For each cluster, we calculated the purity (consistency of the same peptide within a cluster) as estimated by DB-Search and MS-RT. Across 85.4% (9,524 out of 11,152 clusters) of clusters (Figure 2.a and Methods Benchmark metrics) – the purity agreed between MS-RT and DB-Search ( value at y=x is 0.783) – that is the purity difference between MS-RT and DB-Search is at most 10%.

Figure 2 – Consistency Analysis of DB-Search and MS-RT.

On proteomics dataset a) PXD023047 – MS-Cluster – Here we use the clustering of MS-Cluster to evaluate the concordance of our MS-RT Purity measurement – and we find that in 85.4% of clusters, it is within +/− 10% of the DB-Search result. We identify 7.8% of clusters that have higher purity in DB-Search vs MS-RT. b) Here is an example cluster where DB-Search reports a higher purity than MS-RT. This discrepancy arises because the cluster contains MS/MS spectra with distinct retention times that fall into three separate modes, each corresponding to different charge states. DB-Search only identifies a subset of spectra (those from the middle mode), treating the cluster as homogeneous. This illustrates a limitation of DB-Search, which can fail to recognize heterogeneity in clusters when unidentified spectra are present, leading to an overestimation of purity. c) The spectra mirror plot for the identified (from 40 min retention time) from (b) with ion annotation21 SVGDLTSADLKGK and unidentified spectra (from 20 min retention time). The cosine similarity of these two spectra is 0.53, suggesting that that these two spectra come from different peptides. The lack of database search identifications for the unidentified MS/MS spectra blinds traditional purity calculations from these clustering failures. d) We demonstrate an example where MS-RT reports a lower purity than DB-Search (found lower than the Y=X line). This is demonstrated in cases where a peptide appears multiple times at different retention times, leading MS-RT to potentially underestimate the purity value.

For clusters where the purity estimate from DB-Search and MS-RT are inconsistent (>10% difference in purity), we observed that in most cases (877 clusters, 7.8% of all clusters), MS-RT determined the cluster to be low purity and DB-Search determined high purity (below diagonal line in Figure 2.a). These discrepancies were caused by two reasons: the first (867 clusters) was caused by DB-Search only identifying a subset of MS/MS spectra within a cluster – where DB-Search could not use the unidentified MS/MS spectra to evaluate the purity of a cluster. For clusters where DB-Search estimated a higher purity compared to MS-RT, the average database identification rate of the constituent MS/MS spectra was 53%. This contrasts with the average identification rate of all MS/MS spectra across all clusters being 69%. One specific example, highlighted in Figure 2.b, includes a cluster that DB-Search determined to be pure. However, the underlying MS/MS spectra come from three different retention time modes, the first at around 20 min, the second at 40 min, and the third at 90 min (See SI Figure 2). Only the MS/MS spectra at the 40 min mode can be identified using MS-GF+13. A mirror plot of the MS/MS spectra coming from 20 min and 40 min is shown in Figure 2.c, demonstrating different fragmentation for two MS/MS spectra within the same cluster. We also find that the MS/MS spectra from these other modes could not effectively be explained by the dominant peptide in the cluster. Because the 20 min and 90 min MS/MS spectra were not identified, the traditional DB-Search was blind to these clustering errors. This class of clusters with multiple retention time modes, where not all modes are identified, can cause DB-Search to potentially report a purity that is too high (too pure). The second class of errors (10 clusters) involved clusters with a single nominal peptide mass spread across a large retention time range. In these instances, MS-RT reported a low purity, whereas DB-Search reported a high purity (Figure 2.d, SI Figure 3). In these cases, it appears the DB-Search derived purity values to be more accurate, but this occurred with low frequency.

On the other hand, in 750 clusters (6.7%), the MS-RT method estimated purity that were higher than DB-Search (above y=x line). We found that these errors are because MS-RT does not utilize cross-file retention time alignment to evaluate purity. That is, if two different peptides end up in the same cluster but never appear in the same sample MS-RT will incorrectly overestimate the purity (SI Table 1). Finally, we also conducted this same purity consistency experiment on another proteomics dataset, PXD021518, which resulted in a consistent concordance between MS-RT and DB-Search as above (see SI Figure 4).

Evaluating Consistency of MS-RT and DB Search for Completeness

To balance the measures of purity (assessing the accuracy of clustering), state of the art literature also introduces the concept of completeness (assessing sensitivity of clustering). The goal of completeness is to determine how much clustering was accomplished – to avoid the trivial computational solution of not clustering anything yet achieving perfect purity. In the existing literature, the measures for completeness use database search results to evaluate how many different clusters a peptide appeared, with higher fragmentation of the same peptide across many clusters yielding lower completeness scores. Similar to purity, because this is measured by using true labels from database search to evaluate how many distinct clusters the same peptide appears in, where lower is better, such external identification evaluation is not possible yet in metabolomics due to the lack of FDR controlled database search procedures.

Instead, we introduce an N10 value as a proxy for completeness. We borrow the N10 concept from genome assembly that a single number can measure the completeness of a short read assembly19. In the MS/MS clustering context, we define N10 as the size of the smallest cluster at 10% of the total MS/MS dataset size. Using previously published completeness results11 (Dataset PXD000561 Methods Benchmark metrics), we evaluated how consistent this N10 number is compared to the completeness measure in proteomics data and found a 0.984 Pearson correlation (SI Figure 5). This gives us confidence that we can utilize the N10 to capture the essence of clustering completeness, enabling N10 as a proxy measure for completeness in metabolomics studies where completeness cannot be calculated.

Another important aspect in the evaluation of clustering tools is the percentage of the clustered spectra (percentage of the spectra in clusters that have size greater or equal to 2). While N10 focuses on the completeness of the clustering, reflecting how well a tool can group similar spectra together to form clusters, we want to complement the N10 metric with the percentage of clustered spectra. The percentage of clustered spectra indicates the proportion of spectra that have been successfully assigned to clusters out of the total spectra available. This total spectra clustered metric is essential because a higher percentage of clustered spectra suggests that the tool is effective in minimizing unclustered or noise spectra, thereby maximizing the utilization of the data. Especially in small datasets, the overall cluster size may be small, causing the N10 metric to lack resolution for comparing clustering performance. However, in general, we have found that N10 and percentage of clustered spectra have a high correlation (SI Figure 6).

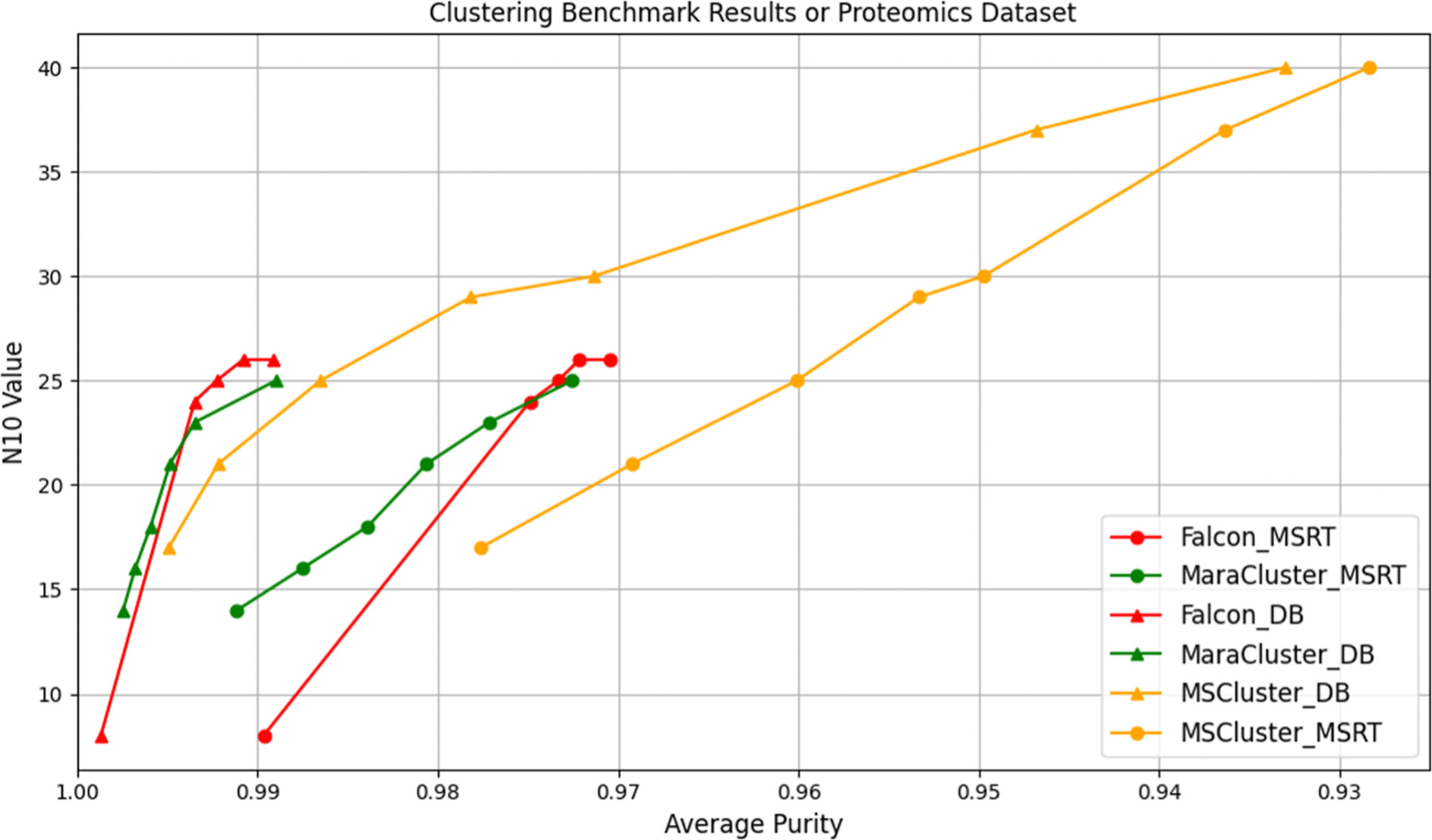

Benchmarking the Performance of Clustering Tools in Proteomics

While above we measured the consistency of completeness and purity between MS-RT and DB-Search, we here aim to measure whether the relative performance between several MS/MS clustering tools is also maintained. We benchmarked the MS/MS clustering tools MS-Cluster22, MaRaCluster8, and Falcon11. The benchmarking results for these clustering methods show a consistent performance ordering when using either DB-Search and MS-RT. In Figure 3, we show the results for these three clustering tools iterated through different parameter settings for both the DB-Search and MS-RT method on the data set PXD023047. While MS-RT and DB-Search purity measures may slightly differ due to situations described above (See Results Evaluating Consistency of MS-RT and DB Search for Purity), the key finding in Figure 3 is that the relative performance between Falcon, MaRaCluster, and MS-Cluster remains consistent when using either DB-Search and MS-RT. Similarly, the benchmarking results for the PXD021518 dataset, shown in SI Figure 7, also validate this consistency. Specifically, we find that Falcon and MaRaCluster consistently achieve higher N10 values than MS-Cluster at any given purity level. We also note that the overall estimation of purity by MS-RT is slightly lower than DB-Search, which is consistent with our previous analysis. Figure 3 demonstrates that there is a trade-off between accuracy (purity) and completeness (measured as N10) among the clustering algorithms.

Figure 3 – Benchmarking results of MS-RT and DB-Search on proteomics dataset PXD023047.

The x-axis represents the average purity, and the y-axis represents the N10 value. The triangle lines correspond to DB-Search, and the circle lines correspond to MS-RT. The red lines indicate Falcon, green indicates MaraCluster, and orange indicates MS-Cluster. The results clearly show that DB-Search overestimates purity on this dataset. This divergence is thoroughly analyzed and attributed to different modes. However, the relative performance of the different tools is consistent between DB-Search and MS-RT. We also extended the parameters of the three clustering tools beyond their commonly used or recommended ranges. As shown in SI Figure 8, these extensions reveal that the relative performance ordering of the clustering tools remains consistent under both MS-RT and DB-Search evaluation, despite the parameter range changes.

Further analysis indicates that the clustering inaccuracies in MS-Cluster are partially due to the inclusion of MS/MS spectra from different charge states within the same cluster1. MS-Cluster appears to rely solely on precursor m/z rather than incorporating charge state information. Consequently, DB-Search fails to detect this type of error, as one of the charge states remains unidentified. In contrast, tools such as Falcon, which consider charge state, do not display this form of clustering error.

Multi-Dataset Proteomics Benchmarking

One of the key weaknesses of the MS-RT method is the inability to align retention times across different runs, raising concerns about its efficacy in evaluating clustering results derived from multiple datasets together. Here, we demonstrate that MS-RT is also adept at benchmarking clustering of multiple joint datasets. Figure 4 illustrates the comparison of clustering algorithm performance on joint proteomics datasets (PXD023047 and PXD021518) using MS-RT and DB-Search. The key observation is that our proposed MS-RT results are consistent with the DB-Search results even on combined proteomics datasets. In the DB-Search results, Falcon and MaRacluster maintain high average purity close to 1.0 across all cluster size ranges, while MS-Cluster shows a decrease in purity as the cluster size increases. Similarly, in the MS-RT results, Falcon and MaRacluster consistently achieve high purity, demonstrating their robustness across different cluster sizes. MS-Cluster, however, experiences a significant drop in purity with increasing cluster sizes. These results also demonstrate that the MS-RT method can handle joint dataset evaluation cases.

Figure 4 –

Clustering results of two joint proteomics datasets (PXD02047 and PXD021518, only shows the range from 1 to 0.925, full range figure sees SI Figure 9). The relative performance between the tools is preserved, with Falcon achieving the most comprehensive performance (highest N10 and maintaining a high average purity score), followed by MaraCluster and MS-Cluster, respectively. We also evaluated the clustering tools on joint proteomics datasets using extended parameter ranges. SI Figure 10 illustrates that the relative performance between Falcon, MaRaCluster, and MS-Cluster is preserved across both MS-RT and DB-Search evaluations, with Falcon consistently demonstrating the highest effectiveness.

Furthermore, we sampled the two datasets to ensure that the contribution from each was balanced with the same number of files. We subsampled the PXD021518 dataset by randomly selecting 50% of the files from the original dataset, resulting in 16 files (~140k MS/MS), which matches the number of the PXD023047 dataset. We then conducted the same purity and completeness evaluation (Figure 5), revealing a similar trend to before where the relative performance between Falcon, MaRaCluster, and MS-Cluster was consistent with DB-Search and MS-RT. Overall, Falcon continues to be the most effective clustering algorithm for this test case, achieving both high N10 values and maintaining high purity. MaRaCluster follows, performing well but slightly less effectively than Falcon. MS-Cluster is behind, showing lower N10 values and a lower purity.

Figure 5 -. Joint clustering results of two proteomics datasets.

In this benchmarking dataset, we merged the original PXD023047 dataset with a randomly sampled 50% of the PXD021518 dataset. The relative performance between the tools is preserved, with Falcon achieving the most comprehensive performance (highest completeness and maintaining a high average purity score), followed by MaRacluster and MS-Cluster, respectively.

Benchmarking the Performance of Clustering Tools in Metabolomics

We evaluated the relative performance of Falcon, MaRaCluster, and MS-Cluster on untargeted metabolomics datasets from both Orbitrap and qTof instruments. First, we benchmarked an Orbitrap dataset (MSV000093033) from algae strains, containing 2,010,711 MS/MS spectra from 71 files. The results show that MaRacluster achieves the highest purity (0.99) but has the lowest N10 value indicating high purity but poor completeness (Figure 6.a). Falcon attains the highest N10 value (300) and a relatively high purity (0.93). Additionally, the results indicate that MaRaCluster, while achieving high purity, clusters a smaller fraction of spectra compared to Falcon and MS-Cluster (Figure 6.b). As an alternative view of completeness that has been used in literature3,8, we analyzed the distribution of cluster sizes and corresponding average purity for each algorithm across various size ranges. In small to medium cluster sizes (2–4 and 65–128), all algorithms maintain high purity, with Falcon leading. As cluster sizes increase (129–256 and 1025–2048), Falcon retains high purity, MS-Cluster exhibits variability, and MaRaCluster’s purity declines. In the largest sizes (2049–4096 and above), MaRaCluster forms few to no clusters (Figure 6.c). This explains that MaRaCluster’s poor completeness is due to its tendency to split larger clusters into smaller ones. These results suggest that Falcon strikes a balance between high purity and more complete clustering with larger clusters.

Figure 6 – Benchmarking results for Metabolomics dataset MSV000093033 (Orbitrap).

(a) N10 value versus average purity: MaRaCluster achieves the highest purity but has a low N10 value. Falcon demonstrates the highest N10 value with substantial average purity, making it the most comprehensive. MS-Cluster performs moderately. (b) Percentage of clustered spectra versus average purity: similar to (a), MaRaCluster, despite its high purity, clusters a smaller fraction of spectra compared to Falcon and MS-Cluster. (c) Distribution of cluster sizes and their corresponding average purity across various size ranges. The x-axis represents different cluster size bins, ranging from the smallest to the largest clusters. The left y-axis, plotted on a logarithmic scale, shows the total number of clusters within each size bin. The right y-axis indicates the average purity of clusters within each size bin. All algorithms maintain high purity in small to medium cluster sizes, with Falcon leading. As cluster sizes increase, Falcon retains high purity, MS-Cluster shows variability, and MaRaCluster’s purity declines. In the largest sizes, MaRaCluster forms few to no clusters.

We also benchmarked a qTof dataset (MSV000081981) from human stool samples, generated using the maXis impact HD instrument, containing 7,838,866 MS/MS spectra from 2307 LC/MS samples. For this dataset, all clustering tools exhibit relatively high purity performance (with a narrow range from 0.992 to 1), but the N10 measure varies among different methods (Figure 7.ab). Falcon achieves the highest N10 value (ranging from 3000 to 5000), indicating more completeness while maintaining high purity. MaRaCluster, on the other hand, achieves the highest purity but poor completeness, resulting in a very low N10 value. MS-Cluster lies in-between in terms of performance, with better completeness than MaRaCluster, but the worst purity among them. Note that while MaraCluster does have a higher purity than both MS-Cluster and Falcon, this gain at such high purity values is nearly negligible and does not overcome the large difference in N10 and the number of spectra clustered (Figure 7.b). Falcon clusters a significant portion of the spectra (ranging from 70% to over 80%) while maintaining high average purity. MaRaCluster, though achieving high purity, clusters only a small fraction of the spectra (ranging from less than 5% to 18%). Similar to the above Orbitrap dataset, when examining the distribution of cluster sizes and corresponding average purity for each algorithm across various size ranges (Figure 7.c), all methods show high purity in small to relatively large clusters (2 to 2049–4096), with MaRaCluster leading. As above, MaRaCluster produces very few large clusters. In the largest sizes (4097–8192 and above), Falcon produces larger clusters (82 compared to 57 from MS-Cluster in the 4097 bin) with slightly higher purity (0.936 vs. 0.934). We hypothesize that MaraCluster might be ill-suited for metabolomics clustering, though it has no fault of its own as it was meant for proteomics, with potentially proteomics specific algorithmic optimizations.

Figure 7 –

Benchmarking results for Metabolomics MSV000081981(qTof) (a) N10 value versus average purity: MaRaCluster achieves the highest purity but has a low N10 value. Falcon demonstrates the highest N10 value with substantial average purity, making it the most comprehensive. MS-Cluster performs moderately. (b) Percentage of clustered spectra versus average purity: similar to (a), MaRaCluster, despite its high purity, clusters a smaller fraction of spectra compared to Falcon and MS-Cluster. (c) Distribution of cluster sizes and their corresponding average purity across various size ranges. The x-axis represents different cluster size bins, ranging from the smallest to the largest clusters. The left y-axis, plotted on a logarithmic scale, shows the total number of clusters within each size bin. The right y-axis indicates the average purity of clusters within each size bin. All algorithms maintain high purity in small to medium cluster sizes, with Maracluster leading. For the largest sizes, MaRaCluster forms few to no clusters, while Falcon has the most significant number of the largest clusters.

Sampling the Metabolomics Dataset Effects on Clustering Performance

We aimed to determine if dataset size affects the performance of various clustering tools and to evaluate the relative gain of these tools as the dataset size increases. We conducted a sampling approach by randomly selecting different percentages of files from the largest dataset, MSV000081981, which contains 2307 files. The sampling ranged from 10% (230 files) up to 100% (2307 files). We found that as the sampling rate increases (i.e., more files are included), the performance of all three clustering tools improves (SI Figure 11, 12), evidenced by higher average purity and larger percentage of clustered spectra. This is expected because the number of replicates increases as the number of files increases, leaving fewer potential singletons (single MS/MS observations). Notably, the relative performance gain among the different clustering methods varies significantly as the sampling rate changes. At a 10% sampling rate, MS-Cluster achieves an average purity of approximately 0.998 and an N10 value in the range of 300 to 400, while Falcon exhibits an average purity of around 0.992 and an N10 value of about 400. However, at a 70% sampling rate, the average purity of MS-Cluster and Falcon are very close (0.9986 Purity), but Falcon shows a significantly larger N10 value of approximately 2500, compared to MS-Cluster’s N10 value of about 1000. We additionally conducted the same experiment on another Orbitrap metabolomics dataset, MSV000093033, which exhibited a similar pattern (See SI Figure 13). Together, these results suggest that Falcon strikes the best balance between purity and completeness across small and especially large datasets.

Benchmarking the Performance of Clustering Tools in Real-world Natural Products Metabolomics from Actinobacteria Samples

We further evaluated MS-RT on a real-world natural products metabolomics dataset derived from 570 actinobacteria samples (See Methods Corteva Mass Spectrometry Experimental Methods). The results, as shown in Figure 8, demonstrate that Falcon remains the most comprehensive clustering tool among the three, achieving the highest N10 value (approximately 1800 across different parameter settings) and the highest average purity (approximately 0.98 across different parameter settings). MS-Cluster performed moderately, with N10 values ranging from 1100 to 1200 and average purity values between 0.96 and 0.98 across different parameter settings. MaRaCluster showed the poorest performance on this dataset, with the lowest N10 and average purity values.

Figure 8 -.

Benchmarking results of real-world natural products metabolomics from actinoyctes fermentation extract samples. The plot compares the performance of three clustering tools: Falcon, MaRaCluster, and MS-Cluster. Falcon consistently achieves the highest N10 values (around 1,800) and maintains the highest average purity (close to 1.0) across various parameter settings. MS-Cluster performs with slightly lower purity (average purity ranging from 0.96 to 0.98) with N10 values between 1,000 and 1,250. MaRaCluster demonstrates the lowest performance, with N10 values under 500 and average purity around 0.5 across its parameter settings.

Validating MS-RT in Metabolomics Using Chemical Standards

We validated the MS-RT method using a set of small molecule chemical standards analyzed in LC-MS/MS (See Method Validation of MS-RT Methods with Chemical Standards in Metabolomics). Specifically, we used the NIH NPAC ACONN Natural Products dataset that included 2,179 unique standards across 275 LC-MS runs. Each LC-MS run included 8 pooled standards with identifications made by matching the precursor m/z within the appropriate run.

We used the annotated chemical standards to evaluate, in a similar fashion to DB-Search, the clustering purity and compared that to the MS-RT approach. The results (See SI Figure 14) show that MS-RT results were consistent with manual annotations in over 95% of cases (2,309 out of 2,414 clusters fell within the Y = X ± 0.1 line). Notably, when evaluating the clustering results using the MS-RT method, it achieved an average cluster purity of 0.919, which is very close to the 0.928 obtained with manual annotations.

Computational Performance of Clustering Algorithms

We evaluated the computational performance of Falcon, MaRaCluster, and MS-Cluster on datasets of varying data scales (from 104 to over 106 MS/MS spectra) by measuring CPU time (total processor usage across threads) and wall time (actual elapsed time). Notably, during our benchmarking we did not use multi-threading for MS-Cluster, whereas both MaRaCluster and Falcon out of the box can exploit multiple CPU cores. We found that MS-Cluster had the lowest CPU-time (See SI Figure 15.a), but Falcon had the fastest wall time at large dataset sizes (>106 spectra) due to high levels of multi-threading (See SI Figure 15.b).

Discussion

In this manuscript, we demonstrate the capability of the MS-RT method for benchmarking the performance of clustering metabolomics MS/MS spectra. By comparing MS-RT with the established DB-Search method on single and merged proteomics datasets, we have validated the consistency and reliability of MS-RT. MS-RT shows a high degree of consistency with DB-Search. Moreover, MS-RT also offers a complementary view of MS/MS clustering that can be missed by DB-Search for unidentified spectra. Further, MS-RT addresses the shortcomings of evaluating MS/MS clustering for metabolomics data. The metabolomics clustering benchmarking results highlight the strengths and limitations of different clustering algorithms, with Falcon emerging as the higher-performing choice for applications requiring high completeness. Interestingly, while MaRaCluster performs comparably to Falcon on proteomics data, MaRaCluster’s performance declines significantly on metabolomics datasets. This disparity may be due to the fact that MaRaCluster was initially designed for proteomics MS/MS data and may not well adapted for metabolomics MS/MS clustering.

It should be noted that there are two main limitations of MS-RT. The first is when the number of repeated acquisitions of an MS/MS within one file is very limited. This situation arises with more advanced DDA acquisition strategies, such as apex triggering23. In this situation, MS-RT lacks repeated MS/MS spectra within one run to evaluate the purity of clusters – potentially overestimating the purity. The second is when there may be disjoint MS/MS spectra between files, especially when we consider clustering from different datasets with a significantly different matrix background. Further, iterative MS/MS acquisition strategies that specifically enforce MS/MS disjointedness across files will not be amenable to MS-RT analysis24. This situation will cause MS-RT to potentially overestimate clustering purity because MS-RT does not assess the clustering of MS/MS across samples. However, in practical terms, when comparing to DB-Search, even though MS-RT may overestimate the clustering purity (e.g. multiple dataset clustering), the relative performance order is maintained across different MS/MS clustering methods. Although this may hinder an accurate assessment of purity, MS-RT still allows for the determination and comparative evaluation of MS/MS clustering tools for metabolomics.

While our study focuses on evaluating clustering methods based on MS/MS similarity, feature finding approaches are a popular alternative strategy for merging MS/MS spectra by utilizing aligned features across datasets. For these feature finding/alignment approaches, it is also important to assess the purity and completeness of MS/MS merging. Existing evaluation methods, e.g. mzRapp25, aim to assess the performance of feature finding/alignment approaches and are complementary to MS-RT because they measure the performance of a different computational category of tool. We also note that the MS-RT is likely unsuited to assess the performance of feature finding/alignment approaches because these approaches exploit retention time through feature finding directly – leading to MS-RT to be blind to clustering errors.

Conclusion

This study validates the MS-RT method as a reliable approach for benchmarking MS/MS clustering, offering complementary insights to the DB-Search method. Despite MS-RT’s limitations, particularly with advanced mass spectrometry data acquisition strategies and disjoint MS/MS spectra across datasets, we demonstrate MS-RT to be a valuable tool for comparing MS/MS clustering methods in metabolomics, a capability that has not been available before. Future work may focus on improving MS-RT’s performance in challenging scenarios to enhance MS-RT’s overall accuracy and reliability. As MS-RT continues to evolve, it holds the potential to push the community to improve MS/MS clustering methods and improve the overall efficiency of metabolomics data analysis.

Supplementary Material

SI Figure 1: Impact of MS/MS clustering on downstream data analysis applications in Metabolomics; SI Figure 2: XIC Plot for File EK_Q_07.mzML at MS-Cluster 1293 of PXD023047; SI Figure 3: XIC Plot for MS-Cluster 14855 of PXD023047; SI Figure 4: Consistency heatmap of MS-RT against DB-Search for the proteomics dataset PXD021518; SI Figure 5: Correlation between Completeness and N10 measure; SI Figure 6: Relationship between N10 and percentage of clustered spectra; SI Figure 7: Benchmarking results of PXD021518 dataset for different clustering tools using MS-RT and DB-Search; SI Figure 8: Parameter extension benchmarking results of PXD023047; SI Figure 9: Benchmarking results of two joint proteomics datasets (PXD02047 and PXD021518) for different clustering tools using MS-RT and DB-Search; SI Figure 10: Parameter extension benchmarking results of the joint proteomics dataset (PXD023047 and PXD021518); SI Figure 11: Benchmarking results (N10 and purity) for different sampling rates of the MSV000081981 dataset (qToF); SI Figure 12: Benchmarking results (N10 and percentage of clustered spectra) for different sampling rates of MSV000081981 (qToF); SI Figure 13: Benchmarking results for different sampling rates of the MSV000093033 dataset (Orbitrap); SI Figure 14: Validate MS-RT cluster purity with metabolomics chemical standards; SI Figure 15: Computational Time Consumption for Different Clustering Tools; SI Table 1: Database identification results for MS-Cluster 87 from PXD023047; SI Table 2: Files counts and MS/MS counts under different sample rates for the MSV000081981 dataset. (DOC)

Acknowledgments

XW is supported by a sponsored research agreement with Corteva Agriscience. MW is supported by NIH 5U24DK133658–02. MW WAS PARTIALLY SUPPORTED by the U.S. Department of Energy Joint Genome Institute (https://ror.org/04xm1d337), a DOE Office of Science User Facility, is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy operated under Contract No. DE-AC02–05CH11231.

Footnotes

Competing interest statement

MW is a co-founder of Ometa Labs LLC

Data Availability

The mass spectrometry datasets analyzed in this study are publicly available. Proteomics datasets (PXD023047, PXD021518, and PXD000561) can be accessed through the ProteomeXchange Consortium, and metabolomics datasets (MSV000081981, MSV000093033, and MSV000080554) are available in the MassIVE repository. The GitHub repository for this project (https://github.com/XianghuWang-287/Metabolomics_Clustering_Benchmark) contains the code, scripts, and detailed documentation for clustering evaluation and benchmarking. Preprocessing steps, parameter configurations, and analysis workflows are also provided to ensure reproducibility.

References

- (1).Frank AM; Bandeira N; Shen Z; Tanner S; Briggs SP; Smith RD; Pevzner PA Clustering Millions of Tandem Mass Spectra. J. Proteome Res. 2008, 7 (1), 113–122. 10.1021/pr070361e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Wang M; Carver JJ; Phelan VV; Sanchez LM; Garg N; Peng Y; Nguyen DD; Watrous J; Kapono CA; Luzzatto-Knaan T; Porto C; Bouslimani A; Melnik AV; Meehan MJ; Liu W-T; Crüsemann M; Boudreau PD; Esquenazi E; Sandoval-Calderón M; Kersten RD; Pace LA; Quinn RA; Duncan KR; Hsu C-C; Floros DJ; Gavilan RG; Kleigrewe K; Northen T; Dutton RJ; Parrot D; Carlson EE; Aigle B; Michelsen CF; Jelsbak L; Sohlenkamp C; Pevzner P; Edlund A; McLean J; Piel J; Murphy BT; Gerwick L; Liaw C-C; Yang Y-L; Humpf H-U; Maansson M; Keyzers RA; Sims AC; Johnson AR; Sidebottom AM; Sedio BE; Klitgaard A; Larson CB; P CAB; Torres-Mendoza D; Gonzalez DJ; Silva DB; Marques LM; Demarque DP; Pociute E; O’Neill EC; Briand E; Helfrich EJN; Granatosky EA; Glukhov E; Ryffel F; Houson H; Mohimani H; Kharbush JJ; Zeng Y; Vorholt JA; Kurita KL; Charusanti P; McPhail KL; Nielsen KF; Vuong L; Elfeki M; Traxler MF; Engene N; Koyama N; Vining OB; Baric R; Silva RR; Mascuch SJ; Tomasi S; Jenkins S; Macherla V; Hoffman T; Agarwal V; Williams PG; Dai J; Neupane R; Gurr J; Rodríguez AMC; Lamsa A; Zhang C; Dorrestein K; Duggan BM; Almaliti J; Allard P-M; Phapale P; Nothias L-F; Alexandrov T; Litaudon M; Wolfender J-L; Kyle JE; Metz TO; Peryea T; Nguyen D-T; VanLeer D; Shinn P; Jadhav A; Müller R; Waters KM; Shi W; Liu X; Zhang L; Knight R; Jensen PR; Palsson BO; Pogliano K; Linington RG; Gutiérrez M; Lopes NP; Gerwick WH; Moore BS; Dorrestein PC; Bandeira N Sharing and Community Curation of Mass Spectrometry Data with Global Natural Products Social Molecular Networking. Nat. Biotechnol. 2016, 34 (8), 828–837. 10.1038/nbt.3597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Rieder V; Schork KU; Kerschke L; Blank-Landeshammer B; Sickmann A; Rahnenführer J Comparison and Evaluation of Clustering Algorithms for Tandem Mass Spectra. J. Proteome Res. 2017, 16 (11), 4035–4044. 10.1021/acs.jproteome.7b00427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Rousseeuw PJ Silhouettes: A Graphical Aid to the Interpretation and Validation of Cluster Analysis. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 1987, 20, 53–65. 10.1016/0377-0427(87)90125-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Davies DL; Bouldin DW A Cluster Separation Measure. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 1979, PAMI-1 (2), 224–227. 10.1109/TPAMI.1979.4766909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Hubert L; Arabie P Comparing Partitions. J. Classif. 1985, 2 (1), 193–218. 10.1007/BF01908075. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Kvålseth T On Normalized Mutual Information: Measure Derivations and Properties. Entropy 2017, 19 (11), 631. 10.3390/e19110631. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (8).The M; Käll L MaRaCluster: A Fragment Rarity Metric for Clustering Fragment Spectra in Shotgun Proteomics. J. Proteome Res. 2016, 15 (3), 713–720. 10.1021/acs.jproteome.5b00749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Elias JE; Gygi SP Target-Decoy Search Strategy for Increased Confidence in Large-Scale Protein Identifications by Mass Spectrometry. Nat. Methods 2007, 4 (3), 207–214. 10.1038/nmeth1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Pipitone R; Eicke S; Pfister B; Glauser G; Falconet D; Uwizeye C; Pralon T; Zeeman SC; Kessler F; Demarsy E A Multifaceted Analysis Reveals Two Distinct Phases of Chloroplast Biogenesis during De-Etiolation in Arabidopsis. eLife 2021, 10, e62709. 10.7554/eLife.62709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Bittremieux W; Laukens K; Noble WS; Dorrestein PC Large‐scale Tandem Mass Spectrum Clustering Using Fast Nearest Neighbor Searching. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2021, e9153. 10.1002/rcm.9153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Hulstaert N; Shofstahl J; Sachsenberg T; Walzer M; Barsnes H; Martens L; Perez-Riverol Y ThermoRawFileParser: Modular, Scalable, and Cross-Platform RAW File Conversion. J. Proteome Res. 2020, 19 (1), 537–542. 10.1021/acs.jproteome.9b00328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Kim S; Pevzner PA MS-GF+ Makes Progress towards a Universal Database Search Tool for Proteomics. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5 (1), 5277. 10.1038/ncomms6277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Luo X; Bittremieux W; Griss J; Deutsch EW; Sachsenberg T; Levitsky LI; Ivanov MV; Bubis JA; Gabriels R; Webel H; Sanchez A; Bai M; Käll L; Perez-Riverol Y A Comprehensive Evaluation of Consensus Spectrum Generation Methods in Proteomics. J. Proteome Res. 2022, 21 (6), 1566–1574. 10.1021/acs.jproteome.2c00069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Skoraczyński G; Gambin A; Miasojedow B Alignstein: Optimal Transport for Improved LC-MS Retention Time Alignment. GigaScience 2022, 11, giac101. 10.1093/gigascience/giac101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Liu Y; Yang Y; Chen W; Shen F; Xie L; Zhang Y; Zhai Y; He F; Zhu Y; Chang C DeepRTAlign: Toward Accurate Retention Time Alignment for Large Cohort Mass Spectrometry Data Analysis. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14 (1), 8188. 10.1038/s41467-023-43909-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Rosenberg A; Hirschberg J V-Measure: A Conditional Entropy-Based External Cluster Evaluation Measure. Proc. 2007 Jt. Conf. Empir. Methods Nat. Lang. Process. Comput. Nat. Lang. Learn. EMNLP-CoNLL 2007, 410–420. [Google Scholar]

- (18).Guthals A; Watrous JD; Dorrestein PC; Bandeira N The Spectral Networks Paradigm in High Throughput Mass Spectrometry. Mol. Biosyst. 2012, 8 (10), 2535–2544. 10.1039/c2mb25085c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium. Correction: Initial Sequencing and Analysis of the Human Genome. Nature 2001, 412 (6846), 565–566. 10.1038/35087627. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Doner NM; Seay D; Mehling M; Sun S; Gidda SK; Schmitt K; Braus GH; Ischebeck T; Chapman KD; Dyer JM; Mullen RT Arabidopsis Thaliana EARLY RESPONSIVE TO DEHYDRATION 7 Localizes to Lipid Droplets via Its Senescence Domain. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 658961. 10.3389/fpls.2021.658961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Bittremieux W; Levitsky L; Pilz M; Sachsenberg T; Huber F; Wang M; Dorrestein PC Unified and Standardized Mass Spectrometry Data Processing in Python Using Spectrum_utils. J. Proteome Res. 2023, 22 (2), 625–631. 10.1021/acs.jproteome.2c00632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Frank AM; Monroe ME; Shah AR; Carver JJ; Bandeira N; Moore RJ; Anderson GA; Smith RD; Pevzner PA Spectral Archives: Extending Spectral Libraries to Analyze Both Identified and Unidentified Spectra. Nat. Methods 2011, 8 (7), 587–591. 10.1038/nmeth.1609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Stincone P; Pakkir Shah AK; Schmid R; Graves LG; Lambidis SP; Torres RR; Xia S-N; Minda V; Aron AT; Wang M; Hughes CC; Petras D Evaluation of Data-Dependent MS/MS Acquisition Parameters for Non-Targeted Metabolomics and Molecular Networking of Environmental Samples: Focus on the Q Exactive Platform. Anal. Chem. 2023, 95 (34), 12673–12682. 10.1021/acs.analchem.3c01202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Broeckling CD; Hoyes E; Richardson K; Brown JM; Prenni JE Comprehensive Tandem-Mass-Spectrometry Coverage of Complex Samples Enabled by Data-Set-Dependent Acquisition. Anal. Chem. 2018, 90 (13), 8020–8027. 10.1021/acs.analchem.8b00929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).El Abiead Y; Milford M; Salek RM; Koellensperger G mzRAPP: A Tool for Reliability Assessment of Data Pre-Processing in Non-Targeted Metabolomics. Bioinformatics 2021, 37 (20), 3678–3680. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btab231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

SI Figure 1: Impact of MS/MS clustering on downstream data analysis applications in Metabolomics; SI Figure 2: XIC Plot for File EK_Q_07.mzML at MS-Cluster 1293 of PXD023047; SI Figure 3: XIC Plot for MS-Cluster 14855 of PXD023047; SI Figure 4: Consistency heatmap of MS-RT against DB-Search for the proteomics dataset PXD021518; SI Figure 5: Correlation between Completeness and N10 measure; SI Figure 6: Relationship between N10 and percentage of clustered spectra; SI Figure 7: Benchmarking results of PXD021518 dataset for different clustering tools using MS-RT and DB-Search; SI Figure 8: Parameter extension benchmarking results of PXD023047; SI Figure 9: Benchmarking results of two joint proteomics datasets (PXD02047 and PXD021518) for different clustering tools using MS-RT and DB-Search; SI Figure 10: Parameter extension benchmarking results of the joint proteomics dataset (PXD023047 and PXD021518); SI Figure 11: Benchmarking results (N10 and purity) for different sampling rates of the MSV000081981 dataset (qToF); SI Figure 12: Benchmarking results (N10 and percentage of clustered spectra) for different sampling rates of MSV000081981 (qToF); SI Figure 13: Benchmarking results for different sampling rates of the MSV000093033 dataset (Orbitrap); SI Figure 14: Validate MS-RT cluster purity with metabolomics chemical standards; SI Figure 15: Computational Time Consumption for Different Clustering Tools; SI Table 1: Database identification results for MS-Cluster 87 from PXD023047; SI Table 2: Files counts and MS/MS counts under different sample rates for the MSV000081981 dataset. (DOC)

Data Availability Statement

The mass spectrometry datasets analyzed in this study are publicly available. Proteomics datasets (PXD023047, PXD021518, and PXD000561) can be accessed through the ProteomeXchange Consortium, and metabolomics datasets (MSV000081981, MSV000093033, and MSV000080554) are available in the MassIVE repository. The GitHub repository for this project (https://github.com/XianghuWang-287/Metabolomics_Clustering_Benchmark) contains the code, scripts, and detailed documentation for clustering evaluation and benchmarking. Preprocessing steps, parameter configurations, and analysis workflows are also provided to ensure reproducibility.