Abstract

In Thailand, stem cell transplantation and horse antithymocyte globulin (ATG) are not accessible for most adult aplastic anemia (AA) patients. Alternative therapies are required. We conducted a cohort study of 110 adult AA patients treated with oxymetholone alone for at least 30 days from 2013 to 2023. Response at month 6 and prognostic factors were evaluated. The mean age was 63.4 years old and 58.2% were female. Severe and very severe AA (SAA/VSAA) comprised 64.5% and 3.6%, respectively. The initial oxymetholone daily dose was 150 mg in 66.4%. The overall response was 56.4% (50.7% for SAA/VSAA), with a median time to transfusion independence of 11.8 weeks. Deaths were regarded as no response. Seventeen (17.9%) patients discontinued the treatment due to side effects, especially hepatitis (15/17). Androgenic side effects (55.5%) mostly occurred within the first month. Multivariate analysis identified that baseline reticulocyte count > 10 × 109/L (adjusted odds ratio [OR] 7.3, 95% confidence interval [CI] (2.55–21.11), oily skin (OR 4.93, 95%CI 1.50–16.26) and acne (OR 9.78, 95%CI 2.11–45.28) occurring within 2 months were predictive for responses. The SKAR scoring system using these three factors showed an area under the ROC curve of 0.87 (95%CI 0.80–0.92). The 5-year overall survival rate was 77.4%. Poor performance status (p < 0.001) and response status (p < 0.001) significantly impacted mortality. Responding patients demonstrated 94.5% 5-year survival. In conclusion, androgen is a useful treatment option for AA in Thailand. The score based on reticulocytes and androgenic effects could predict the response and potentially help decision-making.

Keywords: Aplastic anemia, Anabolic steroids, Oxymetholone, Predictive score, Prognostic factors

Introduction

Aplastic anemia (AA) poses significant challenges in Thailand for the high incidence of 4.6 per million adults. Furthermore, most of them were severe AA (SAA) and commonly diagnosed in the elderly [1]. The current treatment paradigm for adult SAA in Thailand follows a structured approach. Hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) is considered the primary option, but eligible in a small number of patients [1]. This is followed by immunosuppressive therapy (IST) with or without thrombopoietin receptor agonist (TPO-RA) [2–5]. However, a considerable proportion of patients cannot access these treatment modalities due to no stem cell donor, poor patient conditions and/or socioeconomic problems, including the prohibitive cost of treatments and/or lacking caregivers. Therefore, an alternative strategy is needed.

Previous studies demonstrated that androgens conferred poor survival compared with IST using anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG) [6, 7]. Comparing two ATG preparations, the landmark paper reported the superior response rate to horse ATG of 68% compared with 37% of rabbit ATG at 6 months [8]. Unfortunately, the horse ATG is not available in Thailand. A report of 97 severe aplastic anemia (SAA) patients from Asian countries found the response rates to rabbit ATG of 24.3% and 68.6% at 6 and 12 months, respectively [9]. The multicenter registry in Thailand demonstrated the responses of SAA/very severe AA (VSAA) to rabbit ATG with or without cyclosporin, cyclosporin-based treatment, and anabolic steroids alone of 44.4%, 36.4%, and 31.2%, at 6 months, respectively [1]. Although anabolic steroids revealed lower overall efficacy compared to rabbit ATG in this study, they remain an important therapeutic option for specific patient populations who cannot access or are ineligible for standard therapies [4].

The study objectives focus on investigating the response rate and characterizing androgenic side effects associated with oxymetholone and identifying predictive factors for treatment response. A practical scoring system to predict treatment outcomes will be helpful to establish an evidence-based guideline for patient selection. This research represents a step toward optimizing the use of anabolic steroids in adult AA patients who cannot receive HSCT and IST.

Patients and methods

Study design

This cohort study enrolled Thai adult AA patients, aged 15 years or older, who were treated with oxymetholone alone from 2013 to 2023. One hundred and eleven patients (76.6%) were recruited prospectively after informed consent, while 34 cases were retrospectively reviewed. Diagnostic criteria included bone marrow hypocellularity with no abnormal infiltration or fibrosis and at least two of the following: hemoglobin (Hb) < 10 g/dL, platelet count < 50 × 109/L, and neutrophil count < 1.5 × 109/L [2, 3, 10].

The initial dose of oxymetholone was 150 mg/day. Patients with glomerular filtration rate (GFR) below 60 ml/min/m2 or liver diseases received a reduced starting dose of 50–100 mg/day. The dose could be increased if no side effects were observed within one month. If patients showed no response after 6 months, they would be switched to alternative treatments, such as cyclosporin or danazol [2]. Patients were followed up every two weeks until they achieved transfusion independence.

The research proposal and all subsequent amendments were approved by the local Ethics committee, in accordance with ethical standards of the committee on human experimentation and Helsinki Declaration.

Definitions

According to the modified Camitta criteria, severe AA (SAA) was defined by bone marrow cellularity < 25%, or 25–50% with < 30% residual hematopoietic cells, with at least two of the following: (i) neutrophils < 0.5 × 109/L, (ii) platelets < 20 × 109/L, (iii) reticulocyte count < 60 × 109/L. The very severe AA (VSAA) definition was the same as for SAA but with neutrophils < 0.2 × 109/L and non-severe AA (NSAA) was AA which was not fulfilling the criteria for SAA or VSAA [2, 3, 10].

Myelodysplastic syndromes, hemolysis, chromosomal abnormalities and chemotherapy-induced bone marrow suppression were excluded. Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) clone detection by flow cytometry was performed only in cases with evidence of hemolysis because the test was not readily available at the Sakon Nakhon hospital. Transfusion dependence was defined as patients who required regular red blood cell or platelet transfusions to maintain Hb > 7.0 g/dL or platelet counts > 10 × 109/L [10, 11].

Response criteria

The treatment response was evaluated at 6 months. Using the modified intention-to-treat analysis, patients who took at least 30 days of oxymetholone were included. The patients who expired from 30 to 180 days of treatment were regarded as no response. Criteria for responses were based on the RACE study [12]. The complete response (CR) was Hb greater than 10 g/dL with absolute neutrophil counts greater than 1 × 109/L and platelet greater than 100 × 109/L in patients who had not received transfusions, partial response (PR) was transfusion independence and no longer met the criteria for severe disease and no response (NR) was not achieving CR/PR. The response criteria for NSAA were like those of SAA for CR and NR, whereas the criteria for PR were transfusion independence (if previously dependent) or doubling or normalization of at least one lineage or increase of baseline Hb ≥ 3 g/dL, neutrophil ≥ 0.5 × 109/L (if initially < 0.5 × 109/L), and platelet ≥ 20 × 109/L (if initially < 20 × 109/L) [10].

Statistical analysis

Androgenic side effects occurred within 2 months after treatment were assessed as potentially predictive factors. Continuous variables were described using medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) or means and standard deviation (SD) as appropriate. Categorical variables are presented as frequencies and percentages. Chi-square or Fisher exact test and independent samples t-test or Mann-Whitney U test were used to formally compare categorical and continuous variables between two groups, respectively. Risk factors associated with overall response rate (ORR) were determined by logistic regression. Survival was analyzed using Kaplan-Meier survival curves and the log-rank tests. Cox proportional hazards model was applied to determine factors associated with mortality. The multivariable models were developed by adjusting for covariates with p < 0.2 in univariable models and stepwise backward LR to select the final model. The best threshold value of the score was determined using the Youden index J (Sensitivity + Specificity − 1). All statistical analyses utilized STATA version 18.0 (StataCorp LLC, Texas, USA).

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 145 patients were enrolled with the median age of 65 years old. The numbers of VSAA, SAA and NSAA were 9 (6.2%), 96 (66.2%) and 40 (27.6%), respectively. The patients who received androgen treatment for less than 30 days were excluded: 14 losses to follow-up, 10 deaths from aplastic anemia and two deaths from other causes. In addition, nine patients were lost to follow-up during 30–180 days yielding 110 patients for response evaluation at 6 months. The median dose of oxymetholone was 150 mg/day (IQR 100–150).

Oxymetholone response

For 110 evaluable patients, the mean ± standard deviation age was 63.4 ± 12.8 years old. Seventeen patients who prematurely stopped oxymetholone due to side effects were included in the analysis and 14 patients who expired during 30–180 days were regarded as no response.

The overall response rate (ORR) was observed in 56.4% (95%Confidence interval [CI] 46.6–65.8%) at 6 months. The complete response (CR) and partial response (PR) were found in 12.7% (95%CI 7.1–20.4%) and 43.6% (95%CI 34.2–53.4%), respectively. The median duration from starting oxymetholone to the last transfusion before transfusion-free responses was 11.8 weeks (IQR 4.4–20.3).

One hundred and forty-two patients received oxymetholone as the first line treatment. There were only three patients who received androgen as a second line treatment after rabbit ATG. Two of these cases had PR and the other showed no response.

When analyzing the SAA/VSAA subgroup of 75 patients, the ORR was 50.7% (95%CI 38.9–62.4%) comprising 9.3% (95%CI 3.8–18.3%) CR and 41.3% (95%CI 30.1–53.3%) PR. Eleven patients who discontinued oxymetholone due to adverse events were included in the analysis and 11 patients who expired from 30 to 180 days were regarded as no response.

The statistically significant differences between oxymetholone responders versus non-responders were better performance status (PS), higher corrected reticulocyte count, and higher absolute reticulocyte count as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics for adult aplastic anemia categorized by the response to oxymetholone at 6 months. (N = 110)

| Characteristics | Total (N = 110) |

No response group (N = 48) |

Response group (N = 62) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 63.41 ± 12.81 | 65.27 ± 14.4 | 61.97 ± 11.34 | 0.181a |

| Sex: Female | 64 (58.2%) | 29 (60.4%) | 35 (56.5%) | 0.676c |

| Performance status | ||||

| 0–2 | 94 (85.5%) | 35 (72.9%) | 59 (95.2%) | 0.001c |

| 3–4 | 16 (14.5%) | 13 (27.1%) | 3 (4.8%) | |

| Comorbidity | 70 (63.6%) | 30 (62.5%) | 40 (64.5%) | 0.827c |

| Time to treatment (weeks) | 2.57 (1.57–5.14) | 2.36 (1.21–4.00) | 3.29 (1.86–7.00) | 0.077b |

| Oxymetholone dose (mg/d) | 150 (100–150) | 150 (100–150) | 150 (100–150) | 0.760b |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 7.36 ± 2.21 | 6.88 ± 2.03 | 7.75 ± 2.28 | 0.041a |

| Corrected Reticulocyte Count (%) | 0.62 (0.32–0.88) | 0.39 (0.27–0.64) | 0.77 (0.43–0.97) | 0.001b |

| Reticulocyte Count (x109/L) |

10.40 (3.48–22.20) |

7.55 (3.15–15.00) |

15.55 (4.20–25.20) |

0.020b |

| Neutrophil Count (x109/L) | 1.24 (0.73–2.06) | 1.01 (0.67–1.82) | 1.41 (0.99–2.21) | 0.062b |

| Lymphocyte Count (x109/L) | 1.48 (1.16–1.97) | 1.49 (1.10–2.04) | 1.48 (1.2–1.93) | 0.541b |

| Platelet count (x109/L) |

15.00 (7.00–31.25) |

11.50 (6.00–26.50) |

17.00 (9.00–38.00) |

0.100b |

| Bone marrow cellularity (%) | 5 (1–10) | 1 (1–5) | 5 (1–17.5) | 0.085b |

| Severity | ||||

| Non-severe | 35 (31.8%) | 11 (22.9%) | 24 (38.7%) | 0.191d |

| Severe | 71 (64.5%) | 35 (72.9%) | 36 (58.1%) | |

| Very severe | 4 (3.6%) | 2 (4.2%) | 2 (3.2%) | |

| Drug discontinuation | 17 (15.5%) | 6 (12.5%) | 11 (17.7%) | 0.451c |

| Follow-up duration (year) | 2.08 (0.92–4.83) | 1.08 (0.32–2.06) | 3.71 (1.83–5.66) | < 0.001b |

Data are presented as number (%), mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range)

P-values are determined by (a) Independent samples t-test, (b) Mann-Whitney U test, (c) Chi-square test or (d) Fisher’s exact test

Side effects of oxymetholone

Among 110 patients, edema, hepatitis, and gastrointestinal toxicity, including nausea, vomiting and/or dyspepsia, occurred in 26.4%, 20.9%, and 5.5% of cases respectively (Table 2). Seventeen patients (15.5%) had to discontinue the medication due to severe side effects (14 cases of liver enzyme elevations of over three times of the upper limit of normal, and three cases of severe fluid retention/congestive heart failure). There were no statistical differences in dosage and drug discontinuation between responders and non-responders. No correlation was detectable between drug dosage and the occurrence of side effects.

Table 2.

Frequencies of oxymetholone side effects in AA patients. (N = 110)

| Side effects | Total (N = 110) |

No response group (N = 48) |

Response group (N = 62) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oily skin | 44 (40.0%) | 7 (14.6%) | 37 (59.7%) | < 0.001c |

| Acne | 32 (29.1%) | 3 (6.3%) | 29 (46.8%) | < 0.001c |

| Deepening voice | 30 (27.3%) | 4 (8.3%) | 26 (41.9%) | < 0.001c |

| Edema | 29 (26.4%) | 11 (22.9%) | 18 (29%) | 0.470c |

| Hepatitis | 23 (20.9%) | 8 (16.7%) | 15 (24.2%) | 0.336c |

| Hirsutism | 10 (9.1%) | 2 (4.2%) | 8 (12.9%) | 0.181d |

| Gastrointestinal toxicity | 6 (5.5%) | 2 (4.2%) | 4 (6.5%) | 0.695d |

| Fluid retention | 2 (1.8%) | 2 (4.2%) | 0 (0%) | 0.188d |

Data are presented as number (%)

P-values are determined by (c) Chi-square test or (d) Fisher’s exact test

Androgenic side effects were observed in 61 out of 110 patients (55.5%), comprising 44 females (72.1%). The observed skin changes included oily skin with enlarged skin pores, acne, and hirsutism. Most patients experiencing these side effects were female, and all cases occurred within two months of drug initiation. Three androgenic side effects showed significant differences between responders and non-responders. They were deepening voice, oily skin and acne as shown in Table 2.

Predictive factors for oxymetholone response

A multivariate analysis of predictive factors for the response revealed three significant factors, which were absolute reticulocyte count >10 × 109/L, oily skin, and acne as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Predictive factors associated with oxymetholone response in adult aplastic anemia. (N = 110)

| Predictors | Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude OR (95%CI) |

p-value | Adjusted OR (95%CI) |

p-value | |||

| Age < 60 years | 2.03 | (0.89–4.64) | 0.094 | |||

| Sex: Male | 1.18 | (0.55–2.53) | 0.676 | |||

| Performance status 0–2 | 7.31 | (1.95–27.43) | 0.003 | |||

| Comorbidity | 1.09 | (0.50–2.39) | 0.827 | |||

| Time to treatment (weeks) | 1.01 | (0.99–1.04) | 0.328 | |||

| Oxymetholone dose (mg/d) | 1.00 | (0.99–1.01) | 0.961 | |||

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 1.21 | (1.00–1.45) | 0.045 | |||

| Corrected Reticulocyte Count (%) | 3.01 | (1.11–8.16) | 0.031 | |||

| Reticulocyte Count (x109/L) | 1.03 | (1.00–1.06) | 0.036 | |||

| Reticulocyte Count > 10 × 109/L | 3.56 | (1.61–7.86) | 0.002 | 7.33 | (2.55–21.11) | < 0.001 |

| Neutrophil Count (x109/L) | 1.17 | (0.88–1.55) | 0.277 | |||

| Lymphocyte Count (x109/L) | 1.18 | (0.77–1.81) | 0.453 | |||

| Platelet count (x109/L) | 1.00 | (1.00–1.01) | 0.516 | |||

| Bone marrow cellularity (%) | 1.03 | (0.99–1.07) | 0.121 | |||

| Severity | ||||||

| Non-severe | 1.00 | Reference | ||||

| Severe | 0.47 | (0.20–1.11) | 0.084 | |||

| Very severe | 0.46 | (0.06–3.69) | 0.464 | |||

| Drug discontinuation | 1.51 | (0.52–4.43) | 0.453 | |||

| Side effects | ||||||

| Oily skin | 8.67 | (3.36–22.38) | < 0.001 | 4.93 | (1.50–16.26) | 0.009 |

| Acne | 13.18 | (3.70–46.97) | < 0.001 | 9.78 | (2.11–45.28) | 0.004 |

| Deepening voice | 7.94 | (2.54–24.87) | < 0.001 | |||

| Edema | 1.38 | (0.58–3.28) | 0.471 | |||

| Hepatitis | 1.60 | (0.61–4.15) | 0.338 | |||

| Hirsutism | 3.41 | (0.69–16.85) | 0.133 | |||

Abbreviations: OR Odds Ratio, CI confident interval

Variable was included in the multivariable model due to p-value < 0.2 in univariable analysis

†Crude odds ratio estimated by Logistic regression model

‡Adjusted odds ratio estimated by Logistic regression model

Model summary: −2 Log likelihood = 102.061, Pseudo R Square = 0.3228

Hosmer and Lemeshow Test: Chi-square = 2.78, df = 4, p-value = 0.595

Constant = −1.854

Subsequently, the Sakon Nakhon Anabolic Response (SKAR) score was formulated to predict anabolic steroid response using these three significant factors. On the logistic regression model, the coefficients of reticulocyte count > 10 × 109/L at baseline, oily skin and acne (within 2 months after starting treatment) were 1.99 (95% confidence interval [CI] 2.55–21.11), 1.59 (95%CI 1.50–16.26) and 2.28 (95%CI 2.11–45.28), respectively. Therefore, three points were assigned for acne, and two points each were given for reticulocyte count > 10 × 109/L/and oily skin.

Using this predictive score yielded an area under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (AUROC) of 0.87 (95% CI 0.80–0.92). The AA patients who had SKAR scores of three or higher had a high response rate of 90.7%. The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) for each cutoff point were as shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Prediction score performance probabilities of oxymetholone response in adult aplastic anemia at different cut-off points.

| Cut-off Points |

Androgen response N (%) |

Sensitivity % | Specificity % | PPV % | NPV % | Youden Index (J) |

Predicted probability (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≥ 2 | 58 (71.6%) | 93.5 | 52.1 | 71.6 | 86.2 | 0.46 | 48.98 |

| ≥ 3* | 39 (90.7%) | 62.9 | 91.7 | 90.7 | 65.7 | 0.55 | 68.46 |

| ≥ 4 | 37 (90.2%) | 59.7 | 91.7 | 90.2 | 63.8 | 0.51 | 83.09 |

| ≥ 5 | 27 (90%) | 43.5 | 93.8 | 90.0 | 56.3 | 0.37 | 91.74 |

| ≥ 7 | 12 (100%) | 19.4 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 49.0 | 0.19 | 98.27 |

| Abbreviations: PPV positive predictive value, NPV negative predictive value, + | |||||||

| * The best threshold value of the score was determined using the Youden index | |||||||

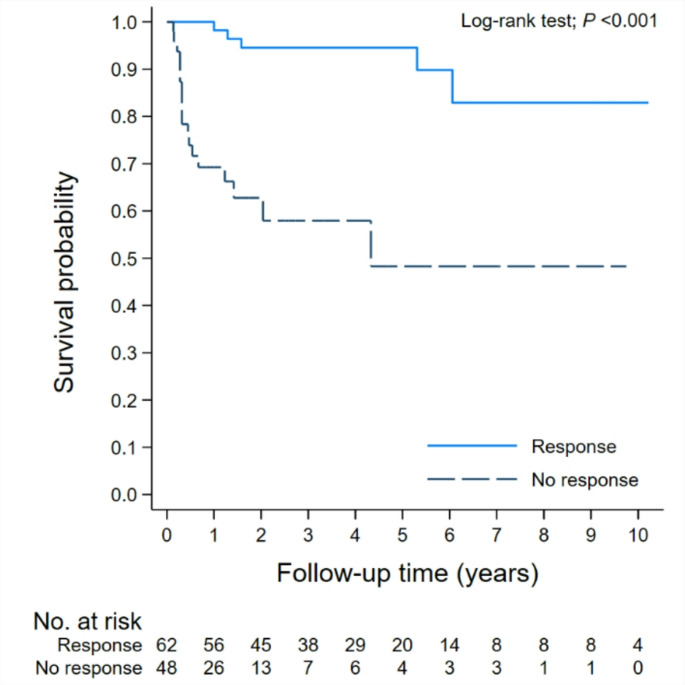

Survival outcomes

Among the total cohort of 110 patients, the 5-year and 10-year overall survival (OS) was 77.4% (95%CI: 66.72–85.06) and 69.6% (95%CI: 54.04–80.73), respectively (Fig. 1). The responders had higher OS over non-responders at 5 and 10 years, 94.5 vs. 48.3% and 82.9 vs. 48.3%, respectively (p < 0.001) as shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 1.

Overall survival of aplastic anemia patients (N = 110)

Fig. 2.

Overall survival of aplastic anemia patients (N = 110). Stratification by responses

The median follow-up times of responders and non-responders were 3.71 years (IQR 1.83–5.66) and 1.08 (IQR 0.32–2.06), respectively. There were six (9.7%) responders who lost the responses at the median time of 17 months (range 4–71 months). Four of them had stopped oxymetholone before relapses. There was no transformation to myeloid malignancy in our cohort. The median survival of both groups was not reachedNSAA showed a higher survival rate compared with SAA/VSAA but there was no statistical difference (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Overall survival of aplastic anemia patients (N = 110). Stratification by disease severities: nSAA, Non-severe aplastic anemia; SAA, Severe aplastic anemia; VSAA, Very severe aplastic anemia

A total of 24 patients expired. The causes of death were infections (9 cases), central nervous system bleeding (5 cases), gastrointestinal bleeding (2 cases), unknown causes (3 cases), and other causes unrelated to AA (5 cases). In a multivariate analysis, factors significantly associated with mortality were poor performance status and no response to oxymetholone as shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Oxymetholone response and performance status predicted mortality in adult aplastic anemia. (N = 110)

| Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted HR† (95%CI) |

p-value | Adjusted HR‡ (95%CI) |

p-value | |||

| Performance status 0–2 vs. 3–4 | 5.78 | (2.4–13.9) | < 0.001 | 6.27 | (2.34–16.79) | < 0.001 |

| Corrected Reticulocyte Count < 0.25% | 2.41 | (0.91–6.34) | 0.75 | 1.51 | (0.54–4.18) | 0.430 |

| Oxymetholone response | ||||||

| Response | 0.11 | (0.04–0.29) | < 0.001 | 0.11 | (0.04–0.32) | < 0.001 |

| Non-response | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | ||

| SKAR Score | ||||||

| < 3 | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | ||

| ≥ 3 | 0.30 | (0.11–0.82) | 0.019 | 0.39 | (0.14–1.11) | 0.077 |

Abbreviations: CI confidence interval, HR Hazard ratio

†Unadjusted hazard ratio estimated by Parametric survival models

‡Adjusted hazard ratio estimated by Parametric survival models adjusting for age, sex, performance status, comorbidity, oxymetholone dose, severity, and drug discontinuation.

Discussion

In this study, the oxymetholone response rate at 6 months was 56.4%, comprising 12.7% CR and 43.6% PR. This exceeds the rates in previous studies from the Thai aplastic anemia study group, European countries, and Mexico of 18.3%, 35.0%, and 45.9% respectively [1, 13, 14]. The response in SAA/VSAA was 50.7%, which appeared to be greater than the responses to rabbit ATG in Asian (24.3%) [9] and general Thai (44.4%) [1] patients. These data suggest that oxymetholone is a reasonable first-line alternative therapy for AA in Northeastern Thailand, particularly when transplantation and IST are not feasible. In this part of Thailand, the AA incidence (5.6 per 100,000) is higher than the other regions [1] and the disease is possibly mediated by different pathogenesis which is androgen responsive. Further mechanistic investigations, such as telomere lengths, in this region should be conducted in the future.

Analysis of predictive markers for androgen response revealed three significant factors: absolute reticulocyte count > 10 × 109/L, oily skin, and acne. These prognostic factors have not been previously reported and were different for other treatments. For example, earlier studies identified lymphocyte count > 1.5 × 109/L, body mass index, and blood transfusion volume as predictive factors for IST responses [15, 16]. The stronger androgenic effects may correlate with greater stimulation of hematopoietic cells, while higher reticulocyte counts might indicate more residual hematopoietic progenitor cells [17, 18]. For AA patients who received low doses of oxymetholone with no such side effects and showed no response, the dose may be raised to a maximum of 150 mg/day.

This study developed the SKAR score representing a novel approach to predict anabolic steroid response in AA patients with a high area under the ROC curve suggesting that it is a useful clinical tool. The score is simple, containing only three factors, and practical for routine use for early identification of likely responders and optimizing treatment selection. A patient who has a baseline absolute reticulocyte count > 10 × 109/L, which equals two points of SKAR score, will have an androgen response probability of 72%. After oxymetholone treatment for 2 months, the score could be re-evaluated by adding two androgenic adverse effects resulting in a higher predictive value. The response rate is over 90% when the score is three or over.

Regarding adverse effects, hepatitis occurred in 20.9% of cases, compared to 11–41% in previous studies. This variation may be due to higher doses (2–3 mg/kg/d) or diverse types of anabolic steroids, or patient characteristics, e.g., age and ethnicity. Gastrointestinal side effects (5.5%) and edema (26.4%) were comparable to previous studies [13, 14, 19, 20]. Androgenic side effects including skin changes were reported in 55.5% of cases, especially in females, comparable to international studies [20]. However, sex itself was not significantly related to the response (Table 3). Skin changes included increased oiliness, acne, increased hair growth, and hoarseness in 30 patients. All changes typically occurred within 1–2 months of starting treatment.

The superior survival rate compared to a previous Thai study (77.4% at 5 years vs. 37.6% at 2 years [1]) requires further investigations. This may suggest the different clinical course of AA from Northeastern compared with the other regions of Thailand. Despite the severe cytopenia from SAA/VSAA, fatal infection or bleeding were not common in our series. The poor performance and non-response status were significantly associated with shorter survival possibly due to prolonged disease progression and/or severity.

The limitation of this study is the single center at the specific region that may reduce generalizability. Future multi-center prospective studies are warranted to validate the SKAR score and confirm these findings in diverse populations. Additionally, we might have included some patients with inherited bone marrow failure as PNH clone detection and genetic examination were not routinely performed.

In conclusion, this study suggests that anabolic steroids remain a viable treatment option for SAA. We identified three key predictive factors for anabolic steroid response formulating the SKAR scoring system, which demonstrated good accuracy. This score could potentially guide clinician decision-making to continue or modify AA therapy

Author contributions

J.C. designed the study, obtained informed consent, collected and analyzed the data and draft the manuscript, P.R. supervised the study, interpreted the data, and revise the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Funding

There is no funding for this study.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Human ethics and consent to participate

The protocol was approved by the Sakon Nakhon Hospital Ethical Committee. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration.

After ethical committee approval, 111 patients were recruited after informed consent. No informed consent was required in 34 retrospectively reviewed cases according to our Institutional Review Board.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Norasetthada L, Wongkhantee S, Chaipokam J, Charoenprasert K, Chuncharunee S, Rojnuckarin P et al (2021) Adult aplastic anemia in thailand: incidence and treatment outcome from a prospective nationwide population-based study. Ann Hematol 100:2443–2452. 10.1007/s00277-021-04566-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Uerprasert N, Chanthorn-Soong K, Pongthanadul B, Leowahussiriwong S, Sirichainun N, Visuthisakchai S et al (2020) Guidelines for diagnosis and management of aplastic anemia in Thailand 2020. J Hematol Transfus Med 30:405–413. https://he01.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/JHematolTransfusMed/article/view/245537 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bacigalupo A (2017) How I treat acquired aplastic anemia. Blood 129:1428–1436. 10.1182/blood-2016-08-693481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Townsley DM, Winkler T (2016) Nontransplant therapy for bone marrow failure. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program 2016:83–89. 10.1182/asheducation-2016.1.83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Young NS (2013) Current concepts in the pathophysiology and treatment of aplastic anemia. Hematol Am Soc Hematol Educ Program 2013:76–81. 10.1182/asheducation-2013.1.76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Camitta BM, Thomas ED, Nathan DG, Gale RP, Kopecky KJ, Rappeport JM et al (1967) A prospective study of androgens and bone marrow transplantation for treatment of severe aplastic anemia. Blood 53: 504–514. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0006-4971(20)74742-7 [PubMed]

- 7.Camitta B, O’Reilly RJ, Sensenbrenner L, Rappeport J, Champlin R, Doney K (1983) Antithoracic duct lymphocyte Globulin therapy of severe aplastic anemia. Blood 62:883–888. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0006-4971(20)85092-7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scheinberg P, Nunez O, Weinstein B, Scheinberg P, Biancotto A, Wu CO et al (2011) Horse versus rabbit antithymocyte Globulin in acquired aplastic anemia. N Engl J Med 365:430–438. 10.1056/nejmoa1103975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chuncharunee S, Wong R, Rojnuckarin P, Chang CS, Chang KM, Lu MY et al (2016) Efficacy of rabbit antithymocyte Globulin as first-line treatment of severe aplastic anemia: an Asian multicenter retrospective study. Int J Hematol 104:454–461. 10.1007/s12185-016-2053-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Killick SB, Bown N, Cavenagh J, Dokal I, Foukaneli T, Hill A et al (2016) Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of adult aplastic anemia. Br J Haematol 172:187–207. 10.1111/bjh.13853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Höchsmann B, Moicean A, Risitano A, Ljungman P, Schrezenmeier H, for the EBMT Working Party on Aplastic Anemia (2013) Supportive care in severe and very severe aplastic anemia. Bone Marrow Transpl 48:168–173. 10.1038/bmt.2012.220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peffault de Latour R, Kulasekararaj A, Iacobelli S, Terwel SR, Cook R, Griffin M et al (2022) Eltrombopag added to immunosuppression in severe aplastic anemia. N Engl J Med 386(1):11–23. 10.1056/NEJMoa2109965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bosi A, Barcellini W, Passamonti F, Fattizzo B (2023) Androgen use in bone marrow failures and myeloid neoplasms: mechanisms of action and a systematic review of clinical data. Blood Rev 62:101132. 10.1016/j.blre.2023.101132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shahani S, Braga-Basaria M, Maggio M, Basaria S (2009) Androgens and erythropoiesis: past and present. J Endocrinol Invest 32:704–716. 10.3275/6149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khemaphiphat P, Thedsawad A, Jianthanakanon J, Taka O, Wanachiwanawin W (2017) Therapeutic response to immunosuppressive agents among Thai patients with Transplant-Ineligible aplastic anemia: possible predictive factors. J Hematol Transfus Med 27:251–260. https://he01.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/JHematolTransfusMed/article/view/71619/78151 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Somprasertkul T, Trirattanapikul W, Khamsai S, Chotmongkol V, Sawanyawisuth K (2024) Treatment response and its predictors of immunosuppressive therapy in patients with severe or very severe aplastic anemia. Med Drug Discov 22:100181. 10.1016/j.medidd.2024.100181 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pagliuca S, Kulasekararaj AG, Eikema DJ, Piepenbroek B, Iftikhar R, Satti TM et al (2024) Current use of androgens in bone marrow failure disorders: a report from the severe aplastic Anemia working party of the European society for blood and marrow transplantation. Haematologica 109:765–776. 10.3324/haematol.2023.282935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jaime-Pérez JC, Colunga-Pedraza PR, Gómez-Ramírez CD, Gutiérrez-Aguirre CH, Cantú-Rodríguez OG, Tarín-Arzaga LC et al (2011) Danazol as first-line therapy for aplastic anemia. Ann Hematol 90:523–527. 10.1007/s00277-011-1163-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nassani M, El Fakih R, Passweg J, Cesaro S, Alzahrani H, Alahmari A et al (2023) The role of androgen therapy in acquired aplastic anemia and other bone marrow failure syndromes. Front Oncol 13:1135160. 10.3389/fonc.2023.1135160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Calado RT (2024) Bone marrow failure on steroids: when to use androgens? Haematologica 109:695–697. 10.3324/haematol.2023.283564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.