SUMMARY

The clearance of damaged or dysfunctional mitochondria by selective autophagy (mitophagy) is important for cellular homeostasis and prevention of disease. Our understanding of the mitochondrial signals that trigger their recognition and targeting by mitophagy is limited. Here, we show that the mitochondrial matrix proteins 4-Nitrophenylphosphatase domain and non-neuronal SNAP25-like protein homolog 1 (NIPSNAP1) and NIPSNAP2 accumulate on the mitochondria surface upon mitochondrial depolarization. There, they recruit proteins involved in selective autophagy, including autophagy receptors and ATG8 proteins, thereby functioning as an “eat me” signal for mitophagy. NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 have a redundant function in mitophagy and are predominantly expressed in different tissues. Zebrafish lacking a functional Nipsnap1 display reduced mitophagy in the brain and parkinsonian phenotypes, including loss of tyrosine hydroxylase (Th1)-positive dopaminergic (DA) neurons, reduced motor activity, and increased oxidative stress.

In Brief

Abudu and coworkers show that the mitochondrial proteins NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 are needed for PARKIN-dependent mitophagy, by facilitating recruitment of the autophagy machinery required for clearance of damaged mitochondria. Nipsnap1-deficient zebrafish larvae have a parkinsonian phenotype including accumulation of reactive oxygen species, reduced dopaminergic neurons, and a locomotion defect.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Macroautophagy (hereafter autophagy) involves sequestration of cytoplasmic cargo into autophagosomes that fuse with lysosomes for degradation (Lamb et al., 2013). Autophagy is needed for survival upon cellular stress and has an important housekeeping function by selective removal of damaged or dysfunctional components. Selective autophagy employs specific autophagy receptors that recognize the cargo to become degraded (Rogov et al., 2014; Stolz et al., 2014). Sequestosome-1 (hereafter referred to as p62), the best studied autophagy receptor, is implicated in clearance of many types of ubiquitinated cargos, including aggregate-prone proteins (Bjørkøy et al., 2005), mitochondria (Geisler et al., 2010; Zhong et al., 2016), bacteria (Zheng et al., 2009), and midbody remnants (Isakson et al., 2013; Pohl and Jentsch, 2009). Autophagy receptors contain a light chain 3 (LC3)-interacting region (LIR) mediating their interaction with microtubule-associated protein 1 LC3 and/or GABA type A receptor-associated protein (GABARAP) family proteins in the autophagy membrane (Birgisdottir et al., 2013; Pankiv et al., 2007). Selective autophagy may also require autophagy adaptor proteins, which possess an LIR but are themselves not degraded by autophagy (Stolz et al., 2014). One such adaptor protein is the large scaffolding protein autophagy-linked FYVE (ALFY), which binds GABARAP and phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate (PtdIns3P) (Lystad et al., 2014; Simonsen et al., 2004), as well as p62 and neighbor of BRCA1 gene 1 (NBR1) (Clausen et al., 2010; Isakson et al., 2013), and is important for selective clearance of protein aggregates (Filimonenko et al., 2010; Lystad et al., 2014), midbody remnants (Isakson et al., 2013), and viral particles (Mandell et al., 2014).

Turnover of mitochondria through autophagy (mitophagy) is important for cellular homeostasis, particularly in post-mitotic and slow dividing cells, such as neurons and cardiomyocytes. Causative mutations in two proteins involved in mitophagy, the E3 ubiquitin ligase PARKIN and PTEN-induced putative kinase 1 (PINK1), are linked to Parkinson’s disease (PD) (Pickrell and Youle, 2015). PINK1 is stabilized on the outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM) after loss of mitochondrial membrane potential, where it phosphorylates ubiquitin (Kane et al., 2014; Kazlauskaite et al., 2014; Koyano et al., 2014) and PARKIN (Kondapalli et al., 2012), leading to PARKIN activation and further K63-linked poly-ubiquitination of mitochondrial substrate(s). This is followed by the recruitment of autophagy receptors, including optineurin (OPTN) and nuclear dot protein 52 (NDP52) (also called CALCOCO2) (Lazarou et al., 2015). While p62 and NBR1 seem dispensable for PARKIN-dependent mitophagy in HeLa cells (Lazarou et al., 2015), p62 is essential for PARKIN-dependent mitophagy in macrophages treated with inflammasome NLRP3 agonists (Zhong et al., 2016), suggesting cell- or context-specific variations in employment of autophagy receptors in mitophagy. Little is known about the mitochondrial signals that trigger recruitment of autophagy receptors and mitophagy. Recently, the inner mitochondrial membrane protein, prohibitin 2 (PHB2) was found to bind LC3 upon OMM rupture and function as a receptor for PARKIN-dependent mitophagy (Wei et al., 2017). In this study, we identify the mitochondrial matrix proteins NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 as “eat me” signals for damaged mitochondria via their recruitment of autophagy receptors and show that NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 have redundant roles in PARKIN-dependent mitophagy and a neuroprotective function in vivo.

RESULTS

NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 Interact with hATG8 Proteins, ALFY, and Autophagy Receptors

To identify new ALFY and/or p62 interactors, cell lysates of ALFY+/+ and ALFY−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) (Dragich et al., 2016) or HEK293 cells stably expressing Enhanced Green Fluorescent Protein (EGFP)-p62 were immunoprecipitated with anti-ALFY antibody or GFP-TRAP, respectively, followed by mass spectrometry analysis of precipitates. The homologous proteins NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 (also called GBAS) were identified as unique interactors of both ALFY and p62 (Figures 1A and 1B).

Figure 1. NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 Bind to Autophagy-Related Proteins.

(A and B) Schematic representation of co-immunoprecipitation experiments. Endogenous ALFY was immunoprecipitated from wild-type (WT) or ALFY−/− MEF lysates (A). Stably transfected EGFP or EGFP-tagged p62 were immunoprecipitated from HEK293 cells (B), followed by mass spectrometry identification of interacting proteins. Only proteins showing specific interaction with ALFY or p62 are shown.

(C) Immunoblotting for NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 in different mouse tissues. BAT, brown adipose tissue; eWAT and sWAT, epididymal and visceral white adipose tissue.

(D) ALFY and p62 both co-immunoprecipitate with NIPSNAP1 independent of each other. EGFP or NIPSNAP1-EGFP was pulled down from U2OS cells transiently transfected with the indicated siRNA and plasmids. Protein levels in cell lysates (input) and immunoprecipitates were visualized by immunoblotting.

(E) NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 interact with selective autophagy receptors. MYC-tagged autophagy receptors were in vitro translated in the presence of [35S]-methionine and binding to GST-tagged NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 immobilized on glutathione-sepharose beads analyzed. Bound proteins were detected by autoradiography (AR) and GST proteins by Coomassie brilliant blue (CBB).

(F) NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 interact with all human ATG8 proteins. GST-tagged hATG8 proteins immobilized on glutathione-sepharose beads were incubated with in-vitro translated full-length MYC-NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2. Bound proteins were detected by autoradiography (AR) and GST-tagged proteins by CBB staining. Densitometry was done using Science Lab. Image gauge (Fujifilm) from three independent experiments.

Values are mean ± SD ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.005 *p < 0.01; one-way ANOVA. See also Figure S1.

In addition to NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2, the highly conserved NIPSNAP-domain protein family contains NIPSNAP3A and NIPSNAP3B (Figure S1A). These proteins contain a putative mitochondrial targeting signal (MTS) in the N terminus, followed by two dimeric alpha-beta-barrel (DABB) domains, the second also referred to as a NIPSNAP domain (Figure S1B). The expression of NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 in mice was limited to a few organs rich in mitochondria and only partially overlapping (Figure 1C). NIPSNAP1 was almost exclusively expressed in brain, kidney, and liver, while NIPSNAP2 was most expressed in heart but also expressed in brain, kidney, liver, muscle, and brown adipose tissue. This is in line with human mRNA levels of NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 (gtexportal.org), suggesting these proteins may have similar functions in different tissues.

ALFY and p62 are known to interact (Clausen et al., 2010), but their interactions with NIPSNAP1 were independent, as endogenous ALFY and p62 both interacted with NIPSNAP1-EGFP in U2OS cells depleted of either transcript (Figure 1D) or in the respective knockout (KO) MEFs (Figure S1C). Several autophagy receptors were found to co-purify with NIPSNAP1- and NIPSNAP2-MYC stably expressed in HeLa cells, including NBR1, NDP52, and Tax1-binding protein 1 (TAX1BP1) (Figure S1D). Direct interactions between p62, NBR1, NDP52, and TAX1BP1 with NIPSNAP1 or NIPSNAP2 were confirmed by glutathione S-transferase (GST) pulldown assays of in-vitro translated proteins (Figures 1E and S1E).

NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 were previously identified as binding partners of LC3 and GABARAP proteins (Behrends et al., 2010; Rigbolt et al., 2014). Hence, both endogenous NIPSNAP1 and in-vitro translated NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 interacted with all human LC3 and GABARAP proteins overexpressed as EGFP-tagged proteins in HeLa cells (Figure S1F) or expressed as recombinant GST-tagged proteins (Figure 1F). Taken together, we have identified NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 as binding partners of proteins involved in selective autophagy, including autophagy receptors p62, NBR1, NDP52 and TAX1BP1, ALFY, and human ATG8 proteins.

NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 Are Mitochondrial Proteins

In line with previous identification of NIPSNAP1 as a mitochondrial protein in rat liver (Nautiyal et al., 2010), human NIPSNAP1- and NIPSNAP2-EGFP co-localized extensively with mitochondrial markers in U2OS and HeLa cells (Figures S2A and S2B). NIPSNAP1 co-purified with mitochondrial matrix protein pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) and translocase of outer mitochondrial membrane 20 (TOMM20) in the mitochondrial fraction (Figure 2A). NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 were protected upon proteinase K (PK) treatment of isolated mitochondria, even upon osmotic shock, similar to PDH but in contrast to TOMM20 and translocase of inner mitochondrial membrane 23 (TIMM23) (Figures 2B and S2C). Similarly, PK treatment in the presence of increasing amounts of digitonin to perforate mitochondrial membranes, showed partial protection of NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 along with mitochondrial matrix protein superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2), while TOMM20 and TIMM23 were degraded at the lowest concentration of digitonin (Figure S2D). The protected NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 bands migrated faster upon SDS-PAGE than full-length proteins, suggesting an exposed part of the protein is efficiently cleaved off by PK. Mitochondrial NIPSNAP1 remained extractable by alkaline sodium carbonate (Na2CO3), indicating that it is not membrane integrated (Figure 2C). We conclude that NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 are mitochondrial matrix proteins.

Figure 2. NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 Are Mitochondrial Matrix Proteins.

(A) NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 co-purify with PDH and TOMM20 in the mitochondrial fraction. Subcellular fractions isolated using QProteome mitochondria isolation kit (Quiagen) from HeLa cells were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting.

(B) NIPSNAP1 is primarily an intra-mitochondrial protein. HeLa cell mitochondria isolated by differential centrifugation were digested with proteinase K (PK) in presence or absence of Triton X-100 and given osmotic shock followed by immunoblotting.

(C) Mitochondrial fractions from HeLa cells were incubated in mitochondrial-buffer alone or mitochondrial-buffer containing Na2CO3 (pH 11.5) and centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 15 min. The pellets (P) and supernatant (S) fractions were immunoblotted.

(D) N-terminal of NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 is necessary and sufficient for mitochondrial localization. HeLa cells were transfected with full-length, EGFP-tagged NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 or indicated deletion constructs. The NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 regions expressed are indicated in green (schematic figures below the images).

(E) The N-terminal 23 aas of NIPSNAP1 facilitate its mitochondrial import. In vitro translated 35S-methionine-labeled full-length or deletion mutant (aa 24–284) of NIPSNAP1 were incubated with isolated mitochondria in mitochondrial import assay buffer for 45 min at 37°C, washed three times, treated with PK, and subjected to SDS-PAGE and autoradiography.

(F) NIPSNAP1 aa 24–64 function as a mitochondrial affinity signal. HeLa cells were transiently transfected with NIPSNAP1-EGFP deletion mutants (aa 24–284 or 24–64) for 24 h before confocal imaging.

(G) Full-length and NIPSNAP1 (24–284) localize to different mitochondrial compartments. HeLa cells transfected with indicated constructs imaged 24 h after. All scale bars are 10 μm. Region of insets are indicated. Results are representative of three independent experiments. See also Figure S2.

NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 Have Two MTSs

Overexpression in HeLa cells (Figure 2D) and an in-vitro mitochondrial import assay (Figure 2E), revealed that NIPSNAP1 is efficiently imported into mitochondria. Fusion of the N-terminal 20 or 19 amino acids (aas) of NIPSNAP1 or NIPSNAP2 to EGFP effectively targeted EGFP inside mitochondria, while deletion of the N-terminal 58 aas abolished mitochondrial localization (Figure 2D). Hence, the N-terminal parts of NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 are both sufficient and essential for intramitochondrial localization. Interestingly, while NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 lacking the first 23 or 21 aas, respectively, were not imported into mitochondria, they were recruited to the mitochondrial surface (Figures 2F and S2F), and remained sensitive to PK (Figure 2E). NIPSNAP1 (aa 24–64)-EGFP localized to the mitochondrial surface (Figure 2F), indicating that this region contains an internal MTS. In line with this, when full-length NIPSNAP1-mCherry was co-expressed with NIPSNAP1(24–284)-EGFP, the two proteins showed distinct mitochondrial localization, showing that accumulation on the mitochondrial surface was not an overexpression artefact (Figures 2G and S2E). Thus, the N termini of NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 contain one signal for import into mitochondria and one for association with the OMM. In contrast, NIPSNAP3A and NIPSNAP3B contain an MTS but no signal for tethering to mitochondria (Figure S2F).

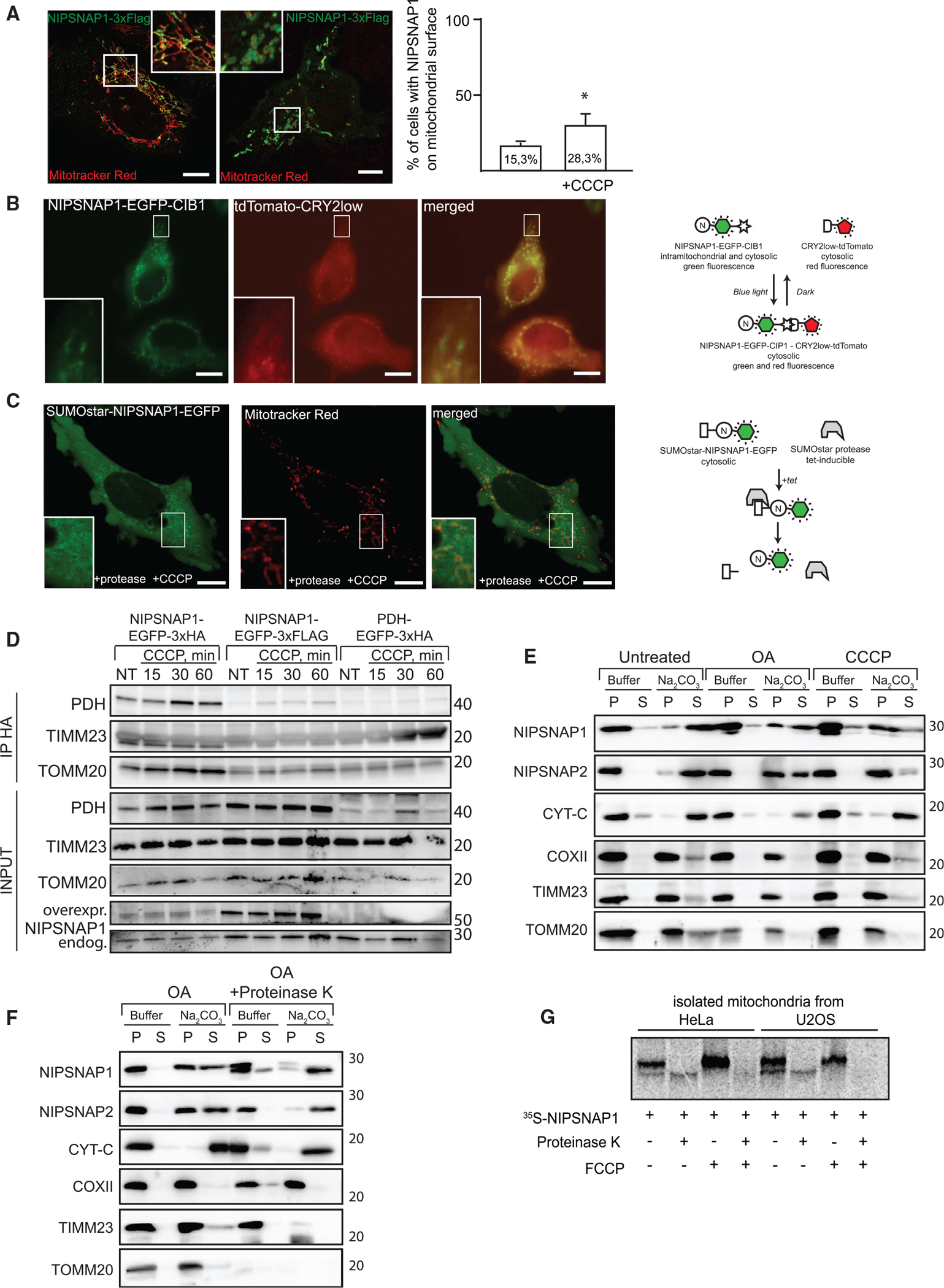

NIPSNAP1 Localizes to the Mitochondrial Surface upon Membrane Depolarization

As NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 bind autophagy proteins and contain signals for mitochondria surface localization, we assumed they might localize on the surface of mitochondria upon induction of mitophagy. Consistent with such a model, NIPSNAP1-EGFP accumulated on the OMM upon disruption of the mitochondrial membrane potential with Carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazine (CCCP) (Figure S3A), which induced mitophagy. As EGFP can be cleaved off from NIPSNAP1 (Figure S3B), making it difficult to distinguish surface-bound from matrix-localized NIPSNAP1 and free EGFP, we employed several imaging and biochemical approaches to investigate if surface localized NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 represent protein re-exported from the mitochondrial matrix and/or newly synthesized protein not yet imported. As expected, NIPSNAP1–3XFLAG expressed in U2OS cells co-localized extensively with Mitotracker Red and TIMM23 (Figures 3A and S3C) and was found to surrounded these mitochondrial markers in approx. 15% of untreated cells (Figures 3A and S3C, lower panel) and approx. 30% of CCCP-treated cells (Figure 3A). As an alternative approach, cells were transfected with NIPSNAP1-EGFP-CIB1 fusion protein and cytosolic CRY2low-tdTomato (Figure 3B), which, upon exposure to blue light, causes formation of transient (minutes) complexes between CIB1 and CRY2low (Duan et al., 2017). tdTomato labeling of NIPSNAP1 at mitochondria was seen, indicating a fraction of NIPSNAP1-EGFP-CIB1 is bound to the surface of mitochondria (Figure 3B). We further exploited the ability of globular proteins to block mitochondrial import, using HeLa cells stably expressing SUMOstar-NIPSNAP1-EGFP and a tet-regulated SUMOstar protease, allowing inducible cleavage of the SUMOstar tag from the fused protein by the SUMOstar protease (Liu et al., 2008) (Figure 3C). As expected, while these cells showed diffuse cytosolic EGFP-staining without tet-induction, mitochondrial EGFP staining and cleavage was observed upon induction of SUMOstar protease (Figures S3D and S3E). When cells were co-treated with tet and CCCP, NIPSNAP1-EGFP accumulated on the mitochondrial surface (Figure 3C).

Figure 3. NIPSNAP1 Is Enriched on the OMM upon Depolarization.

(A) NIPSNAP1–3XFLAG is present both inside (left image) and outside (right image) mitochondria. Representative images of the two phenotypes of subcellular distribution of transiently transfected NIPSNAP1–3xFLAG in U2OS cells and the frequency of both phenotypes, quantified in untreated and CCCP-treated cells. Values are mean ± SD, *p < 0.05 (unpaired Student’s t test).

(B) NIPSNAP1-EGFP-CIB1 can localize to surface of mitochondria. HeLa cells transiently transfected with NIPSNAP1-EGFP-CIB1 and CRY2low-tdTomato. 24 h after transfection CRY2 was activated by 5 sec pulse of blue light (475 nm, 20 mW/cm2) and imaged on Zeiss AxioObserver Z1 fluorescent microscope.

(C) HeLa cells stably transfected with SUMOstar-NIPSNAP1-EGFP under control of a constitutive CMV promoter and SUMOstar protease under control of tet-on regulated CMV promoter were treated for 5 h with 1 μg/ml tetracycline followed by 5 h treatment with 10 μM CCCP and 1μg/mL tetracycline, followed by 15 min incubation with 50 nM Mitotracker Red. Scale bars in (A)–(C) are 10 μm.

(D) NIPSNAP1 as an affinity tag for purification of mitochondria. HeLa cells stably transfected with NIPSNAP1-EGFP-3xHA, NIPSNAP1-EGFP-3xFLAG or another mitochondrial matrix protein, PDH-EGFP-3xHA, were treated with 20 μM of CCCP for indicated periods of time or left untreated (NT), then lysed in KPBS under non-detergent conditions and subjected to immunoprecipitation with magnetic beads, conjugated to anti-HA antibody for 5 min. Immunoprecipitates and input lysates were immunoblotted with indicated antibodies.

(E) The mitochondrial fraction from HeLa mCherry-Parkin cells treated or not with OA or CCCP for 3 h, was incubated in mitochondrial-buffer alone or mitochondrial-buffer containing Na2CO3 (pH 11.5) and centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 15 min. The pellets (P) and supernatant (S) fractions were immunoblotted.

(F) Mitochondria isolated from HeLa mCherry-Parkin cells treated with OA for three hours were subjected to sodium carbonate (Na2CO3, pH 11.5) extraction in presence or absence of 15 μg/mL proteinase K. Indicated mitochondrial proteins were analyzed by immunoblotting.

(G) NIPSNAP1 mitochondrial import, but not mitochondrial binding, is dependent on intact mitochondrial membrane potential. In-vitro translated 35S-methionine-labeled NIPSNAP1 was incubated with untreated or FCCP-treated mitochondria from HeLa or U2OS cells in mitochondrial import buffer for 45 min at 37°C, washed three times, treated with PK, and subjected to SDS-PAGE and autoradiography.

See also Figure S3.

Using anti-HA magnetic beads for rapid immunopurification from cells expressing 3xHA-tagged proteins (Chen et al., 2016), increased amounts of mitochondria were purified from cells expressing 3xHA-tagged NIPSNAP1 than from cells expressing 3xFLAG-tagged NIPSNAP1 or 3xHA-tagged PDH (Figure 3D). Moreover, more mitochondria were immunopurified from NIPSNAP1-EGFP-3xHA cells treated with CCCP (Figure 3D), confirming that the fraction of NIPSNAP1 on the mitochondrial surface increases upon disruption of the membrane potential.

Consistent with this, alkaline Na2CO3 extraction of isolated mitochondria showed that NIPSNAP1 was extracted into the supernatant in untreated cells, but was partly retained in the pellet in cells treated with a combination of Oligomycin and Antimycin A (OA) or CCCP (Figure 3E). NIPSNAP1 and NIPS-NAP2 found in the pellet upon Na2CO3 extraction of OA treated cells were highly sensitive to PK treatment, demonstrating their OMM association upon loss of membrane potential, in contrast to the inner mitochondrial membrane protein cytochrome c oxidase subunit II (COXII) (Figure 3F). While in vitro-translated NIPSNAP1 was partially protected from PK when added to isolated untreated mitochondria, it was not protected from PK when added to mitochondria treated with Carbonyl cyanide 4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenylhydrazone (FCCP), although there was no difference in NIPSNAP1 binding to isolated mitochondria (Figure 3G). Thus, a functional membrane potential is important for mitochondrial import of NIPSNAP1, but not for its binding to mitochondria.

NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 Act as “Eat Me” Signals for Mitophagy

As NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 localize to the mitochondrial surface upon membrane depolarization, we speculated that they could function as an “eat me” signal for recognition of depolarized mitochondria by autophagy receptors. Indeed, interaction of NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 with p62 and NDP52 increased in CCCP-treated or hypoxic cells compared to untreated cells, as shown by immunoprecipitation (Figures 4A–4E and S3F) and proximity labeling (Figure S3G). Using a split-YFP bimolecular fluorescence complementation assay (Nyfeler et al., 2008), we show that a NIPSNAP1-GABARAP complex accumulates on the mitochondria surface upon CCCP treatment, with little or no mitochondrial YFP signal in untreated or control cells (Figures 4F and S3H). LC3B and ALFY were also recruited to mitochondria in a CCCP-dependent manner and detected on NIPSNAP1-positive structures (Figure 4G). Together, our data show that mitochondrial depolarization tethers NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 to the mitochondrial surface, where they recruit proteins involved in selective autophagy. Hence, NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 may act as “eat me” signals for mitophagy.

Figure 4. Increased Interaction of NIPSNAP1 with LC3B, p62, NDP52, and ALFY after Induction of Mitochondrial Depolarization.

(A) HeLa PARKIN cells transiently transfected with 3xFLAG or 3xFLAG-p62 were treated with 10 μM CCCP or exposed to hypoxia (1% O2) for 6 h. Cells were lysed and immunoprecipitated with FLAG resin. Protein levels in cell lysates (input) and immunoprecipitates were detected by immunoblotting.

(B) Densitometry of results shown in (A) from 3 independent experiments. Values are mean ± SD ***p < 0.001; one-way ANOVA.

(C) HeLa cells stably expressing EGFP or NIPSNAP-EGFP were treated as in (A) followed by GFP-trap immunoprecipitation. Co-immunoprecipitation of p62 and NDP52 was detected by immunoblotting.

(D–E) Quantification of results shown in (C) based on 3 different experiments. Values are mean ± SD ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01; one-way ANOVA.

(F) U2OS cells were transiently transfected with NIPSNAP1 and GABARAP fused to split-YFP1 or split-YFP2, respectively, then treated 24 h after transfection with 10 μM CCCP for 4 h, stained with 50 nM of Mitotracker Red for 20 min, and subjected to confocal microscopy. Scale bars are 10 μm.

(G) U2OS cells were transiently transfected with NIPSNAP1–3xFLAG, treated or not with 10 μM CCCP overnight, stained with anti-FLAG together with anti-LC3B or anti-ALFY antibodies, and subjected to confocal imaging. Scale bars are 10 μm.

See also Figure S3.

NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 Have Redundant Functions in Mitophagy

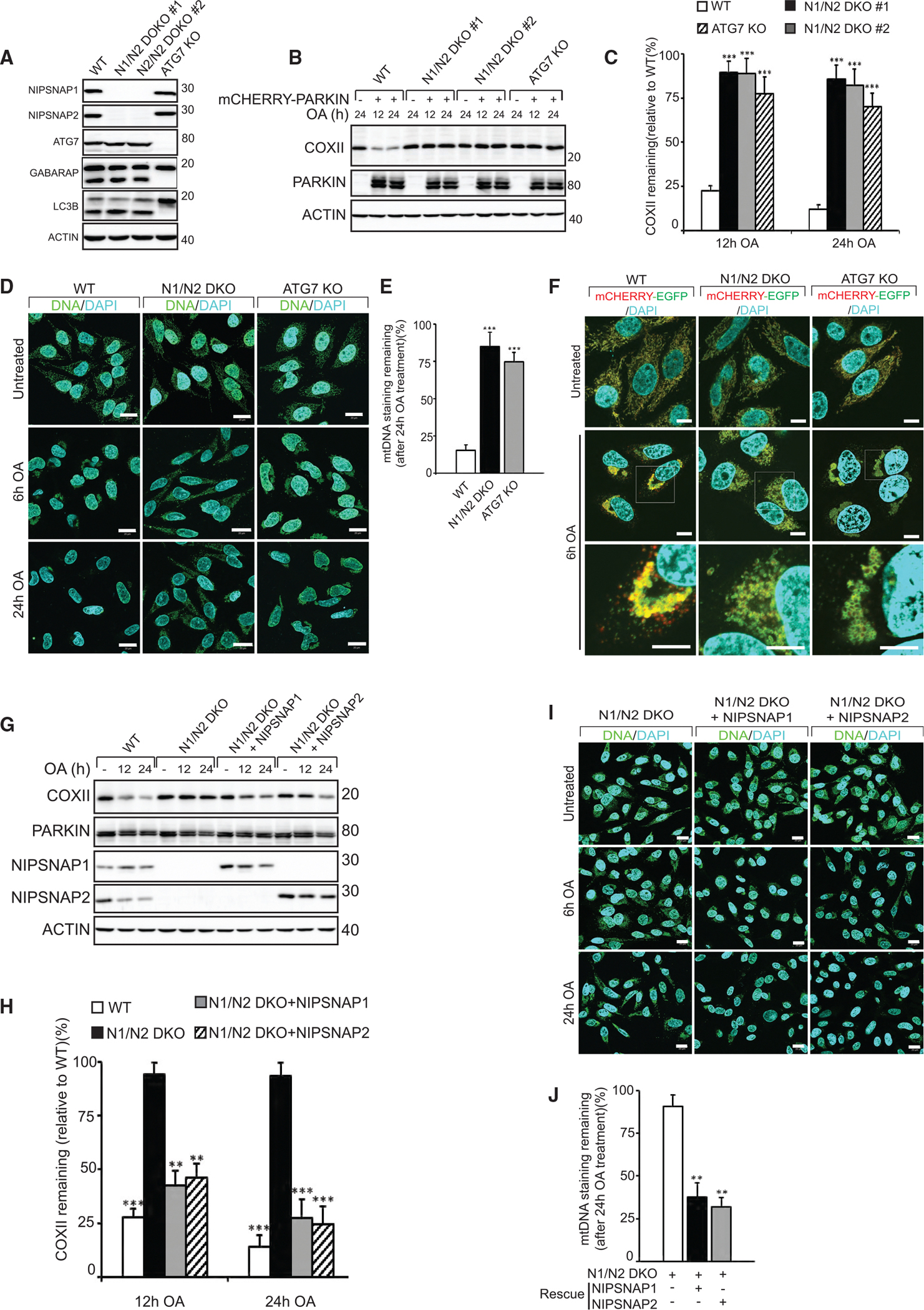

To investigate a possible role of NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 in mitophagy, HeLa cells stably expressing PARKIN were depleted of NIPSNAP1 and/or NIPSNAP2 using siRNA, followed by treatment with CCCP or OA for 12 h or 24 h. Depletion of ATG7 was used as a control (Figure S4A). Depletion of NIPSNAP1, either alone or together with NIPSNAP2, inhibited both CCCP-and OA-induced mitophagy, as analyzed by immunoblotting for COXII and TIMM23 (Figures S4B, S4C, and S4F–S4H) and immunostaining for TIMM23 (Figures S4D and S4E), while depletion of NIPSNAP2 alone had no effect. Using two independent siRNAs against NIPSNAP1, we noticed that its depletion also reduced NIPSNAP2 levels (Figure S4I). To further determine their individual contribution to PARKIN-dependent mitophagy, HeLa cells stably expressing mCherry-PARKIN with KO of NIPSNAP1 and/or NIPSNAP2 were generated, with ATG7 KO as a control (Figures 5A and S4J). As expected, single NIPSNAP1 or NIPSNAP2 KO had no effect on OA-induced PARKIN-dependent mitophagy, as measured by COXII immunoblotting in two different clones of each, although mitophagy was strongly inhibited in ATG7 KO cells (Figures S4J–S4L). Similar to the NIPSNAP1 siRNA acting on both NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2, double KO (DKO) of NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 (N1/N2 DKO) blocked both CCCP- and OA-induced mitophagy, as evident by immunoblotting of COXII (Figures 5B, 5C, and S5A) and immunostaining of mitochondrial DNA nucleoids (Figures 5D and 5E). Moreover, using cells expressing the mCherry-EGFP-OMP25TM tandem tag mitophagy reporter, red only dots (representing mitochondria in lysosomes due to pH-sensitive quenching of GFP) were detected in wild-type (WT) cells, but not in N1/N2 DKO or ATG7 KO cells upon OA or CCCP treatment (Figures 5F and S5B). Importantly, re-expression of either NIPSNAP1 or NIPSNAP2 in DKO cells revealed that they are functionally redundant, as both were able to rescue CCCP- or OA-induced mitophagy (Figures 5G–5J and S5C). Over-expression of either NIPSNAP1 or NIPSNAP2 in HeLa PARKIN cells did not increase CCCP or OA-induced mitophagy (Figures S6A and S6B). Together, our data show that NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 are required for PARKIN-dependent mitophagy and have a redundant function.

Figure 5. NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 Are Required for Mitophagy.

(A) CRISPR-Cas9-mediated double knockout of NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 (N1/N2 DKO) or ATG7 in HeLa cells were confirmed by immunoblotting. The effect of ATG7 KO on autophagy was confirmed by immunoblotting against LC3B and GABARAP.

(B) WT, N1/N2 DKO, and ATG7 KO HeLa cells with or without mCherry-PARKIN expression were treated with OA for 12 or 24 h and extracts immunoblotted as indicated.

(C) Densitometry of COXII protein levels relative to WT in (B). Values are mean ± SD ***p < 0.001, one-way ANOVA.

(D) Representative images of mCherry-Parkin expressing WT, N1/N2 DKO and ATG7 KO cells treated with OA for 6 or 24 h, immunostained for mtDNA nucleoids (green) and DAPI (blue). Scale bars are 20 μm.

(E) Quantification of mtDNA nucleoid staining shown in (D) from three independent experiments. More than 100 cells were quantified per sample. Values are mean ± SD ***p < 0.001, one-way ANOVA.

(F) WT, N1/N2 DKO, and ATG7 KO HeLa cells stably expressing the mCherry-EGFP-OMP25TM mitophagy reporter were left untreated or treated with OA for 6 h and analyzed by confocal microscopy. Scale bars are 10 μm.

(G) mCherry-PARKIN expressing WT, and N1/N2 DKO HeLa cells were rescued or not with untagged NIPSNAP1 or NIPSNAP2, followed by treatment with OA for 12 or 24 h and immunoblotting.

(H) Quantification of COXII levels relative to WT from data shown in (F). Values are mean ± SD ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.005, one-way ANOVA.

(I) Representative images of mCherry-PARKIN expressing N1/N2 DKO cells rescued or not with NIPSNAP1 or NIPSNAP2 treated with OA for 6 or 24 h, then immunostained for mtDNA nucleoids (green) and DAPI (blue). Scale bars are 20 μm.

(J) Quantification of mtDNA staining of data shown in (I). More than 100 cells were quantified per sample. Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments. Values are mean ± SD **p < 0.005, one-way ANOVA.

See also Figures S4 and S5.

Depletion of NIPSNAP1 and/or NIPSNAP2 did not inhibit PARKIN-independent mitophagy induced by the iron-chelator deferiprone (DFP) in U2OS cells expressing another tandem-tag mitophagy reporter (NIPSNAP (1–53)-GFP-mCherry), although siRNA-mediated depletion of ULK1 or addition of the lysosomal proton pump inhibitor Bafilomycin A1 (BafA1) efficiently blocked DFP-induced mitophagy (Figures S5D–S5F). Depletion of NIPSNAP1 or NIPSNAP2 had no effect on oxygen consumption rate of the mitochondria (Figure S5G) or on basal autophagy as measured by degradation of long-lived proteins upon starvation (Figure S5H) or mitochondria membrane depolarization (Figure S5I). Similarly, KO of both NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 did not affect degradation of p62 and NDP52 under basal or starved conditions (Figures S6C and S6D). This suggests a specific role for NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 in PARKIN-dependent mitophagy, supported by our finding of an interaction between NIPSNAP1 and PARKIN in U2OS cells (Figure S5J).

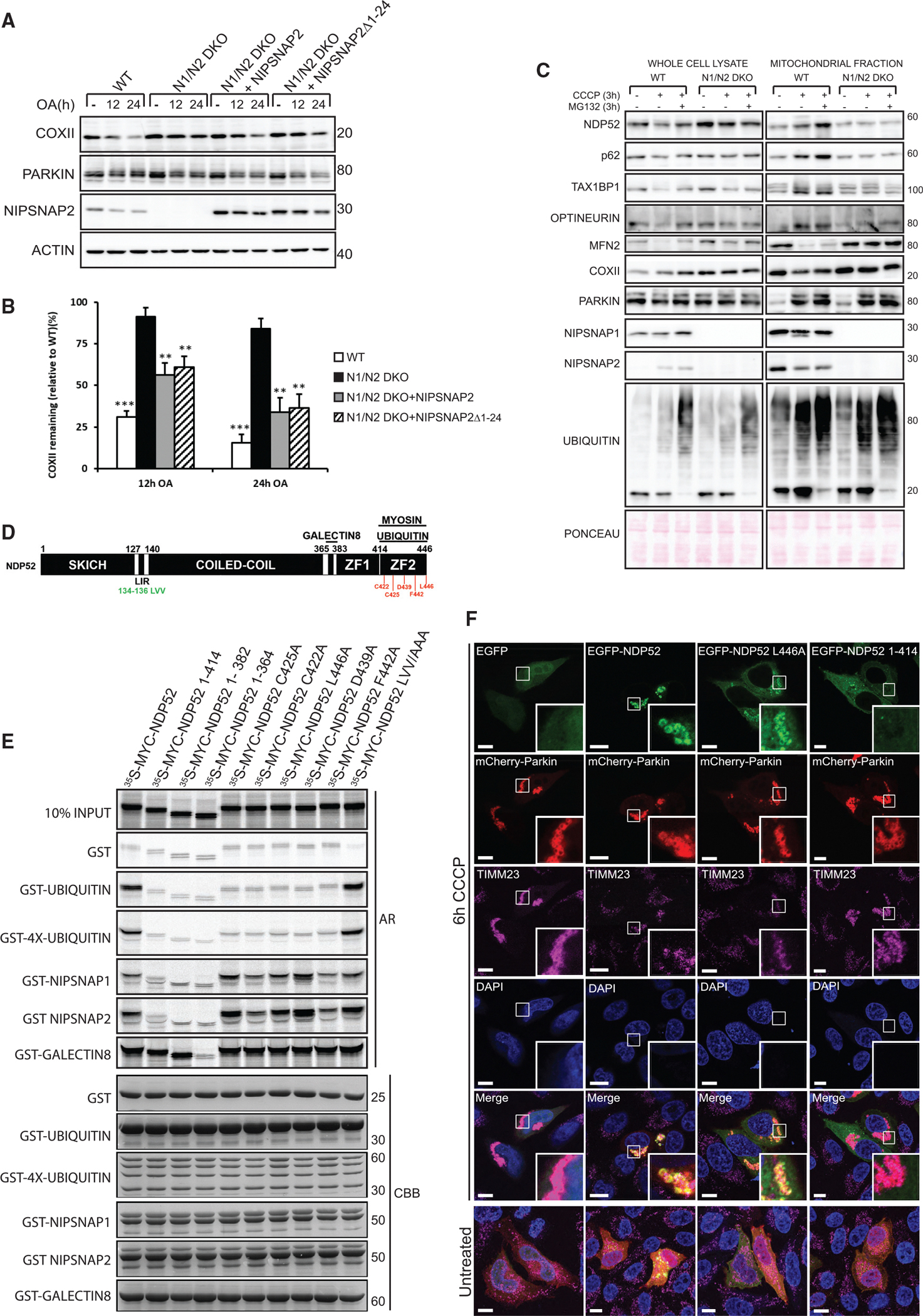

NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 Recruit Autophagy Receptors to Mediate Mitophagy

To determine if localization of NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 on the surface of mitochondria is responsible for their function in mitophagy, NIPSNAP2 Δ1–24, which binds to the mitochondrial surface but is not imported, was stably expressed in N1/N2 DKO cells. Indeed, both OA- and CCCP-induced PARKIN-dependent mitophagy was rescued comparably to the full-length protein (Figures 6A, 6B, and S6E), suggesting an important function of NIPSNAPs on the mitochondria surface in mitophagy.

Figure 6. NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 Have Redundant Functions in Mitophagy.

(A) WT cells, N1/N2 DKO cells, and N1/N2 DKO cells rescued with untagged NIPSNAP2 or NIPSNAP2 Δ1–24 and stably expressing mCherry-PARKIN were treated with OA for 12 or 24 h and immunoblotted as indicated.

(B) Densitometry of COXII protein levels relative to WT from data shown in (A). Values are mean ± SD ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.005, one-way ANOVA.

(C) Whole cell lysate and mitochondria fraction from WT and N1/N2 DKO cells stably expressing mCherry-PARKIN were treated with CCCP with or without MG132, subjected to immunoblotting and Ponceau S staining of proteins used as loading control.

(D) Domain structure of NDP52 indicating binding sites for myosin VI, galectin 8, and ubiquitin. aa indicated in red are point mutations (mutated to alanines) that affect ubiquitin binding to the zinc finger (ZF2) domain. The LIR required for interaction with hATG8 proteins is annotated in green.

(E) MYC-tagged NDP52 wild-type and indicated mutants were in vitro translated and used in GST-pulldown assay with GST-tagged NIPSNAP1, NIPSNAP2, ubiquitin, 4x-ubiquitin, or galectin 8.

(F) HeLa NDP52 KO cells were co-transfected with mCherry-Parkin and EGFP or EGFP- NDP52 WT or mutants (indicated in D) and treated with CCCP for 6 h. Recruitment of EGFP-tagged proteins to mitochondria was analyzed by staining with an antibody against TIMM23. Regions of insert are indicated. Scale bars are 10 μm.

See also Figure S6.

After treatment with OA or CCCP, no mtDNA nucleoid aggregation or clustering occurred in N1/N2 DKO cells compared to WT or ATG7 KO cells (Figures 5D, 5F, and 5I), a role attributed to p62 (Okatsu et al., 2010). Thus, NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 may be required for recruitment of autophagy receptors to mitochondria following depolarization. To test this, WT and N1/N2 DKO HeLa mCherry-PARKIN cells were treated with CCCP in absence or presence of the proteasome inhibitor MG132, followed by fractionation of mitochondria and immunoblotting. While PARKIN recruitment and ubiquitination of mitochondria were similar in WT and N1/N2 DKO cells (Figure 6C), recruitment of NDP52, p62, OPTN, and TAX1BP1 to mitochondria in N1/N2 DKO cells was dramatically reduced compared to WT cells (Figure 6C), indicating that NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 are required for recruitment of autophagy receptors during mitophagy.

To test if PINK1 and/or PARKIN contribute to accumulation of NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 on the OMM upon depolarization, we first examined if NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 are phosphorylated upon depolarization. Using Phos-tag SDS-PAGE, we observed similar phosphorylation levels of NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 with and without CCCP treatment (Figure S6F). Consistently, no phosphorylation of NIPSNAP1 or NIPSNAP2 by PINK1 was detected, whereas PARKIN and ubiquitin were both phosphorylated by PINK1 in vitro (Figure S6G). Secondly, while Mitofusin-2 (MFN2) was ubiquitinated by PARKIN upon CCCP treatment, in agreement with Sarraf et al. (2013), no ubiquitination of endogenous or over-expressed NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 was observed (Figures S6H and S6I).

We found both p62 and NDP52 to bind the region encompassing aas 65–100 of NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 (Figures S6J and S6K). The C-terminal zinc-finger domain (aas 343–446) of NDP52, required for binding to ubiquitin, myosin VI, and galectin 8 (Thurston et al., 2012; Tumbarello et al., 2012) was sufficient for binding to both NIPSNAPs (Figure S6L). Of the two NDP52 zinc finger domains (ZF1 and ZF2), only the most C terminal domain is required for ubiquitin binding (Xie et al., 2015). We therefore asked whether interaction of NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 with NDP52 was ubiquitin dependent. Although binding of NDP52 to both NIPSNAP1, NIPSNAP2, and ubiquitin required the ZF2 domain, several mutations that abolished binding to ubiquitin did not affect binding to NIPSNAP1 or NIPSNAP2 (Figures 6D and 6E), suggesting that binding of NDP52 to NIPSNAP1 or NIPSNAP2 and ubiquitin can occur simultaneously. To examine how NDP52 is recruited to mitochondria, NDP52 KO cells were transfected with mCherry-PARKIN together with NDP52 WT, a ZF2 point mutant (L446A) that cannot bind ubiquitin but interacts with NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2, or a deletion mutant (1–414) lacking the ZF2 domain and neither interacts with NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 nor ubiquitin. Both WT NDP52 and the L446A mutant were recruited to mitochondria, while NDP52 1–414 remained cytosolic after treatment with CCCP for 6 h (Figures 6F and S6M). The NDP52 L446A mutant was mostly recruited to fragmented mitochondria and not to perinuclear mitochondrial clusters. These results suggest that initial recruitment of NDP52 to damaged mitochondria is mediated by ubiquitination of OMM proteins. However, subsequent and sustained mitophagy-dependent recruitment of NDP52 is dependent on NIPSNAP1 and/or NIPSNAP2 (Figure 6C).

NIPSNAPs Are Evolutionary Conserved and Expressed during Zebrafish Embryogenesis

To elucidate a function for NIPSNAPs in vivo we used zebrafish as a model organism. Zebrafish Nipsnap1 and Nipsnap2 display high aa identity (≥75%) to the human and mouse proteins, indicating evolutionary conservation (Figures S7A and S7B). The temporal expression pattern of nipsnap1 and nipsnap2 during zebrafish embryogenesis, determined by quantitative PCR (qPCR), showed maternal expression from the 2 cell stage to 2 h post fertilization (hpf), which, for nipsnap1, gradually increased throughout gastrulation, peaking at 9 hpf, followed by a decrease down to 3 days post fertilization (dpf) and thereafter remained low. In contrast, nipsnap2 expression was lower than nipsnap1 during gastrulation and increased from 3 dpf (Figure S7C).

Whole-mount mRNA in situ hybridization (WISH) revealed nipsnap1 as ubiquitously expressed from early stages of embryogenesis, present in the endoderm by the 6-somites stage (11.5 hpf) with even stronger staining at 1 dpf (Figure 7A). nipsnap1 mRNA was detected in endoderm-derived organs such as liver, intestine, and pectoral fins and was predominantly expressed in the head from 1 to 4 dpf. Consistent with qPCR results, expression of nipsnap1 decreased considerably at 5 dpf. nipsnap2 was also expressed in the brain during development but was contrary to nipsnap1 expressed in the myotome at 1 dpf (Figure S7D). Western blot of different zebrafish adult tissues showed Nipsnap1 to be the predominant form expressed in brain, heart, muscle, liver, intestine, testis, and ovary and in low amounts in kidney, whereas Nipsnap2 was found in brain, heart, and testis and highly expressed in the ovary (Figure S7E). As these proteins have a redundant function in mitophagy, we focused our further investigation on Nipsnap1.

Figure 7. Nipsnap1-Deficient Zebrafish Larvae Display Parkinsonism.

(A) Spatial expression pattern of nipsnap1 across different development stages of zebrafish as demonstrated by whole-mount in situ hybridizations. All embryos are in lateral view. Scale bar is 200 μm.

(B) Representative images of control (WT), nipsnap1 mutant, and rescue (nipsnap1 mutant + zebrafish nipsnap1 mRNA) transgenic tandem-tagged mitofish larvae at 3 dpf. Images are from head region of zebrafish larvae. Scale bars are 20 μm.

(C) Quantification of ratio of red puncta to yellow puncta (representative of mitophagy) per cell. Average of 15 cells from each of 25 larvae for control (WT), nipsnap1 mutant, and nipsnap1 mutant + rescue; tandem-tagged mitofish larvae from three independent experiments were used for quantification.

(D) Control (WT), nipsnap1−/− and nipsnap1 mutant embryos at 3 dpf incubated with CellROX and ROS levels quantified from six different experiments. Error bars represent ± SEM.

(E) Spatial expression pattern of tyrosine hydroxylase 1 (th1) gene in control (WT), nipsnap1−/− and nipsnap1 mutant embryos at 3 dpf determined by whole-mount in situ hybridization. Orientation dorsal. Scale bar is 200 μm.

(F) Quantification of the number of Th1 positive neurons from images in (D). 10 control (WT), 20 mutant and 20 knockout larvae were used for quantification. Values were normalized to control (WT) values.

(G) Representative immunoblots of Nipsnap1, Th1, and β-tubulin on whole embryo lysates of WT, nipsnap1−/− and nipsnap1 mutant embryos at 3 dpf. β-tubulin served as loading control.

(H) Representative images of TUNEL assay on control (WT), nipsnap1 mutant and DNase-treated WT larvae (positive control) at 3dpf. Orientation lateral. Scale bar is 200 μm.

(I) Quantification of mean fluorescent intensity from demarcated region from images in (H). 10 control (WT), 15 nipsnap1 mutant, and 10 positive control larvae were used for quantification, respectively. Values were normalized to control (WT) values.

(J) Motility analysis of WT and nipsnap1 mutant embryos at 7 dpf using the “Zebrabox” automated videotracker (Viewpoint, Lyon). Assay was carried out during daytime, one cycle of 20 min exposure to light (white horizontal bar) followed by 20 min of darkness (black horizontal bar). Vertical bars indicate average distance moved during 5 min intervals. Controls and nipsnap1 mutants were treated or not with 5 mM of L-DOPA for 1 h, after which they were analyzed for motility. Each group consisted of 20–24 larvae.

All error bars indicate SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.005, ***p < 0.0005, **** p < 0.00005, unpaired Student’s t test. See also Figure S7.

Mitophagy Is Reduced in Nipsnap1-Deficient Zebrafish Larvae

CRISPR-mediated genome editing of nipsnap1 in zebrafish embryos achieved near complete depletion of Nipsnap1 protein (Figures 7G and S7F). Nipsnap1 KO larvae (nipsnap1−/−) did not survive beyond day five and we also used a zebrafish line with the heterozygous nipsnap1sa14357 mutant allele (Kettleborough et al., 2013), having a single T > A base pair change in exon 6 (Figure S7F) resulting in a premature stop codon. Lysates from Nipsnapsa14357 embryos (nipsnap mutant) at 72 hpf had a significant reduction of the Nipsnap1 protein compared to WT, with no smaller molecular weight bands appearing, suggesting that the shorter transcripts undergo nonsense-mediated decay (Figure 7G).

To investigate if Nipsnap1-deficient larvae display reduced mitophagy, we generated stable transgenic zebrafish lines expressing a tandem-tagged mitochondria marker (cytochrome c oxidase subunit 8A (Cox8A)-GFP-mCherry) (Figure 7B) in the control (WT) or nipsnap1 mutant background. The ratio of red to yellow puncta was significantly reduced in the head region of Nipsnap1-deficient larvae at 3 dpf (Figures 7B and 7C), although large variation between different cell types could be detected. There was no difference in red dot formation in the muscle of WT and Nipsnap1-deficient larvae (data not shown). The reduced level of mitophagy in the head of nipsnap1 mutants could be partially rescued by injection of zebrafish WT nipsnap1 mRNA into one-cell nipsnap1 mutant embryos (Figures 7B, 7C, and S7G). Thus, Nipsnap1 is required for efficient mitophagy in the head but not in muscles of zebrafish larvae. As Nipsnap2 is abundantly expressed in muscles (Figure S7D), we speculate it could facilitate mitophagy in this tissue.

Nipsnap1-Deficient Zebrafish Larvae Display Parkinsonism

PD is characterized by death of dopaminergic (DA) neurons in the substantia nigra, which can be linked to dysfunctional mitophagy and increased level of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Pickrell and Youle, 2015). As Nipsnap1 was mainly detected in the brain of zebrafish larvae (Figure 7A) and mouse (Figure 1C), consistent with its reported high expression in DA neurons in the midbrain and noradrenergic neurons in the brainstem of mice (Nautiyal et al., 2010), we asked if Nipsnap1-deficient larvae displayed parkinsonian phenotypes. Indeed, a significant increased level of ROS was seen in the nipsnap1 mutant and nipsnap1−/− embryos compared to WT controls (Figures 7D and S7H). Zebrafish have two orthologs of tyrosine hydroxylase (Th1 and Th2), catalyzing conversion of L-tyrosine to L-DOPA, the precursor for dopamine, where the level of Th1 can be used to infer DA neuron health (Holzschuh et al., 2001). Interestingly, both nipsnap1 mutant and nipsnap1−/− embryos showed a dramatic reduction in th1 staining compared to controls as analyzed by WISH (Figures 7E and 7F) and immunoblotting for Th1 (Figures 7G and S7I). TUNEL staining showed increased cell death in the nipsnap1 mutants relative to WT controls (Figures 7H and 7I). Interestingly, the locomotor activity of nipsnap1 mutant larvae at 7 dpf was dramatically reduced compared to WT larvae, as analyzed by quantification of swimming activity in the light and dark over a time course using the Zebrabox (Figure 7J). The swimming defect of nipsnap1 mutants was rescued with exogenous addition of 5 mM L-DOPA (Figures 7J and S7J), indicating that the locomotion defect of nipsnap1 mutants is due to a reduced number of DA neurons and possibly lower levels of dopamine in the mutants (Figures 7E–7G).

DISCUSSION

The Mitochondrial Matrix Proteins NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 Have a Redundant Function as “Eat Me” Signals in PARKIN-Mediated Mitophagy

Much effort has been put into deciphering mechanisms of recognition of damaged mitochondria. Here we identified NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 as binding partners of p62 and ALFY, both involved in selective autophagy (Rogov et al., 2014; Stolz et al., 2014). NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 are predominantly mitochondrial matrix proteins. However, they also localize to the OMM upon CCCP- or OA-induced mitochondrial depolarization to recruit autophagy receptors and ATG8 homologs and effectively act as “eat me” signals for PARKIN-dependent mitophagy.

A mitochondrial membrane potential is required for the import of most mitochondrial proteins (Kulawiak et al., 2013; Truscott et al., 2003). The imported proteins generally do not decorate the OMM upon treatment with CCCP. In contrast, cytosolic NIPSNAP1 was readily detected on the surface of depolarized mitochondria and on the mitochondrial surface in non-treated cells. The possibility that intra-mitochondrial NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 become stabilized at the surface cannot be completely excluded.

Mitophagy depends on autophagy receptors, but it is not clear why only some autophagy receptors are crucial for mitophagy in certain cell lines. Only NDP52, TAX1BP1, and OPTN are required for PARKIN-dependent mitophagy in HeLa cells (Lazarou et al., 2015), while p62 is sufficient for PARKIN-dependent mitophagy in macrophages (Zhong et al., 2016). NDP52, NBR1, OPTN, p62, and TAX1BP1 all have ubiquitin-binding domains (Birgisdottir et al., 2013). p62 and OPTN bind to damaged mitochondria in a PARKIN- and ubiquitin-dependent manner (Okatsu et al., 2010). PARKIN-mediated ubiquitination of OMM proteins can however not fully account for these differences. Recently, the inner mitochondrial membrane protein prohibitin 2 (PHB2) was found to bind LC3 upon mitochondrial depolarization and function as a receptor for PARKIN-dependent mitophagy (Wei et al., 2017). Here, we show that recruitment of autophagy receptors to depolarized mitochondrial is mediated by NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2, which both interact with NDP52, p62, NBR1, TAX1BP1, and the autophagy adaptor ALFY. ALFY interacts with p62 and facilitates recruitment of the phagophore for selective autophagy by binding to PtdIns3P and GABARAP (Clausen et al., 2010; Filimonenko et al., 2010; Lystad et al., 2014). We find that the NDP52 L446A mutant, which binds NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 but not ubiquitin, is recruited to mitochondria after 6 h of CCCP treatment. Thus, PARKIN-dependent ubiquitination of OMM proteins leading to their proteasomal degradation upon mitochondrial damage may “prime” mitochondria for lysosomal degradation (Chan et al., 2011; Geisler et al., 2010; Glauser et al., 2011; Shlevkov et al., 2016; Tanaka et al., 2010; Yoshii et al., 2011), while OMM-localized NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 are required to sustain recruitment of autophagy receptors required for mitophagy. We confirmed the interaction of NIPS-NAP1 and NIPSNAP2 with ATG8 proteins (Behrends et al., 2010) and showed GABARAPs as preferred interacting partners. Thus, efficient targeting of dysfunctional mitochondria for mitophagy involves several layers of specific interactions between mitochondrial proteins and the autophagy machinery.

The function of NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 in mitophagy is likely specific to PARKIN-dependent mitophagy. NIPSNAP1 was immunoprecipitated by PARKIN, and we did not see a difference between control and NIPSNAP1- and NIPSNAP2-depleted cells when inducing mitophagy by iron depletion, shown to be PARKIN independent (Allen et al., 2013). Depletion of NIPSNAPs also did not affect starvation-induced autophagy.

Ablation of Nipsnap1 in Zebrafish Causes Parkinsonism

PD is characterized by death of DA neurons in the substantia nigra, linked to dysfunctional turnover of mitochondria (Pickrell and Youle, 2015). NIPSNAP1 was most significantly downregulated in a study of genome-wide gene expression data of PD samples compared to controls (Fu and Fu, 2015). Nipsnap1 was also downregulated in a proteomics study of neural SH-SY5Y cells responding to 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) treatment, known to lead to degeneration of DA neurons (Choi et al., 2014). Mouse NIPSNAP1 is highly expressed in midbrain DA neurons and brainstem noradrenergic neurons (Nautiyal et al., 2010). Consistently, zebrafish depleted of Nipsnap1 had reduced mitophagy in the brain. Because of their post-mitotic state and metabolic requirements, neurons are particularly vulnerable to mitochondrial dysfunction. Zebrafish lacking Nipsnap1 showed significant loss of Th1-positive DA neurons in the diencephalospinal tract, and the aberrant locomotion phenotype of nipsnap1 mutants was rescued completely by exogenous addition of L-DOPA. Nipsnap1-deficient larvae also displayed increased ROS production compared to WT larvae. Hence, we propose that reduced mitophagy in Nipsnap1-deficient larvae leads to increased ROS, resulting in death of DA neurons and a locomotion defect.

Our results are similar to other studies that have modeled PD-related genes in zebrafish. parkin, pink1, and lrrk2 knockdown using antisense morpholinos resulted in decreased levels of DA neurons. pink1 morphants had elevated ROS level and lrrk2 morphants displayed motor defects (Anichtchik et al., 2008; Flinn et al., 2009; Sheng et al., 2010). A pink1 TALEN-mediated KO zebrafish line showed 30–40% DA neuronal loss (Zhang et al., 2017). Autophagy was found to protect DA neurons in an MPTP-induced PD model in zebrafish (Hu et al., 2017). atg5 downregulation caused a pathological locomotor behavior, DA neuron loss, and accumulation of α-Synuclein aggregates, which was reversed by Atg5 overexpression.

We show that zebrafish lacking a functional Nipsnap1 display parkinsonism, including reduced Th1-positive DA neurons and dysfunctional neuronal motor activity rescued by exogenous addition of L-DOPA. Zebrafish Nipsnap1 and Nipsnap2 show 75% aa identity with the corresponding human and mouse orthologs. The expression pattern of nipsnap1 and nipsnap2 in zebrafish, as in mouse and humans, is largely tissue specific. It is clearly conceivable that our data in zebrafish are characteristic for the function of mouse and human NIPSNAPs.

STAR★METHODS

CONTACT FOR REAGENT AND RESOURCE SHARING

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to the Lead Contact, Anne Simonsen (anne.simonsen@medisin.uio.no).

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Cell Culture

Human cells (U2OS, HeLa and HEK293) were all from ATCC. Mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were kindly provided by Masaaki Komatsu (p62 KO MEFs) and Ai Yamamoto (ALFY KO MEFs) (Dragich et al., 2016; Komatsu et al., 2007). All cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 1X L-glutamine, 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin.

Mouse and Zebrafish Husbandry

Male C57BL/6J wild-type (WT) mice were housed in a temperature-controlled (22°C) facility with a strict 12 h light/dark cycle and free access to water and food at all times. The mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation and tissues were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. Proteins were extracted from mouse tissues with a precipitation buffer (50 mM Tris/HCl pH 7.4, 150 mM sodium chloride, 1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 2 mM EDTA). Equal amount of protein was resolved by SDS/PAGE and immunoblotted with indicated antibodies. Fish (WT strains and the nipsnap1 mutant lines) were held at the zebrafish facility at the Centre for Molecular Medicine Norway (AVD.172) using standard practices. Embryos were incubated in egg water (0.06 g/L salt (Red Sea)) or E3 medium (5 mM NaCl, 0.17 mM KCl, 0.33 mM CaCl2, 0.33 mM MgSO4, equilibrated to pH 7.0). From 12 hpf, 0.003% (w/v) 1-phenyl-2-thiourea (Sigma-Aldrich) was used to inhibit pigmentation. Embryos were held at 28 °C in an incubator following collection. All use of animals was approved and registered by the Norwegian Animal Research authority. Experimental procedures followed the recommendations of the Norwegian Regulation on Animal Experimentation (“Forskrift om forsøk med dyr” fra 15.jan.1996). All experiments conducted on larvae at 7 dpf were approved by Mattilsynet (FDF Saksnr. 16/153907).

METHODS DETAILS

Antibodies and Reagents

The following antibodies were used for human cells: rabbit monoclonal anti-NIPSNAP1 antibody (Cell Signaling, #D1Y6S), rabbit polyclonal anti-NIPSNAP1 antibody (Abcam, #ab67302 and #ab133840), mouse monoclonal anti-NIPSNAP2 antibody (LSBio, #LS-B13280), rabbit polyclonal anti-NIPSNAP2 antibody (ABGENT, #AP6752c), rabbit polyclonal anti-NIPSNAP2 antibody (Abcam, #ab153833), rabbit polyclonal anti-ALFY antibody (Simonsen et al., 2004), rabbit polyclonal anti-GFP antibody (Abcam, #ab290) and (Santa-Cruz; #sc-8334), mouse monoclonal anti-GFP antibody (Clontech, #632381), mouse monoclonal anti-MYC tag antibody (Cell Signaling, #2276), mouse monoclonal anti-HA tag antibody (Roche, #11583816001), anti-p62 mouse monoclonal (BD Biosciences, #610833) and guinea pig polyclonal (Progen, #GP62-C) antibodies, rabbit polyclonal anti-CALCOCO2 Antibody (Sigma, #HPA023195), mouse monoclonal anti-NBR1 antibody (Santa Cruz, #sc-130380), rabbit polyclonal Anti-TAX1BP1 antibody (Sigma, #HPA024432), rabbit polyclonal Anti-Optineurin antibody (Sigma, #HPA003360), mouse monoclonal anti-MTCO2 antibody (Abcam, #ab110258), mouse monoclonal anti-DNA antibody (Progen, #61014), rabbit polyclonal anti-SOD-2 antibody (Santa Cruz, #sc-30080), mouse monoclonal anti-MFN2 antibody (Santa Cruz, #sc-100560), mouse monoclonal anti-Ubiquitin (FK2) antibody (Enzo, #BML-PW8810), rabbit monoclonal anti-ATG7 antibody (Cell Signaling, #D12B11), rabbit polyclonal anti-Actin antibody (Sigma, #A2066), rabbit polyclonal anti-PDH antibody (Cell Signaling, #2784S), mouse monoclonal anti-Cytochrome-C antibody (Abcam, #ab110325), rabbit polyclonal anti-Parkin antibody (Cell Signaling, #2132), rabbit polyclonal anti-LC3B antibody (Novusbio, #NB100–2220), mouse monoclonal anti-GABARAP antibody (MBL, #M135–3), rabbit polyclonal anti-LC3B antibody (Sigma, #L7543), mouse monoclonal anti-TOMM20 antibody (Santa Cruz, #sc-17764), rabbit polyclonal anti-TOMM20 antibody (Santa Cruz, #sc-11415), mouse monoclonal anti-TOMM40 antibody (Santa Cruz, #sc-365467), rabbit polyclonal anti-IKKα antibody (Cell Signaling, #2682), rabbit polyclonal anti-histone H3 antibody (Abcam, #ab1791), mouse monoclonal anti-TIMM23 antibody (BD Biosciences, #611223), mouse monoclonal anti-FLAG epitope M2 antibody (Sigma, #F1804), rabbit monoclonal anti-DYKDDDDK-tag (FLAG-tag) antibody (Cell Signaling, #14793S). The following antibodies were used for zebrafish: rabbit polyclonal anti-Nipsnap1 (Abcam, #ab133840) and Nipsnap2 (Abcam, #ab153833), mouse monoclonal anti-tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) (ImmunoStar, #22941) and mouse monoclonal anti-α-Tubulin (Sigma, #T5168). The following kits and reagents were used: KAPA SYBR® FAST qPCR Kits (KAPA Biosystems #KK4601), DIG RNA Labelling Mix (Roche #11277073910), Anti-Digoxigenin AP fragments (Roche #11093274910), Proteinase K (PK) (Roche #3115828001), QProteome mitochondria isolation kit (Qiagen, #37612), TnT T7 coupled reticulocyte lysate system (Promega, #L4610), CellRox (ThermoFisher, #C10422), Propidium Iodide (ThermoFisher, #P1304MP), FCCP, L-Dopa (Sigma, #333786), Formamide (Sigma, #S4117), Torula Yeast RNA (Sigma, #R6625), Heparin Sodium Salt (Sigma, #H4784), Collagenase P (Sigma, #11249002001), SP6/T7 mMessage mMachine (Ambion #AM1340M/#AM1344), 10 μM Oligomycin (Sigma, #495455 or #04876) and 4 μM Antimycin A (Sigma, #A8674), 10 μM Carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazine CCCP (Sigma, #C2759), Hanks Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) (Sigma, #H8264), Bafilomycin A1 (Sigma, #B1793), MG132 (Z-Leu-Leu-Leu-al) (Sigma, #C2211) and Ponceau S (Sigma, #P3504). All siRNAs were purchased from Dharmacon Inc. The target sequences include NIPSNAP1 (CCAGGAACCAUGAUCGAGU, CGUAACAGGAACUCGGAAG), NIPSNAP2 (GCCAAAGAUUCAC GAAGAU) and ATG7 (CAGUGGAUCUAAAUCUCAAACUGAU) (Høyer-Hansen et al., 2007).

Generation of Human Knockout Cell Lines Using CRISPR-Cas9 System

Human NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 knockout cell lines were generated with the CRISPR-Cas9 system as described previously (Ran et al., 2013). Two guide RNAs designed for both NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 where annealed and ligated into a BbsI linearized vector (Addgene #62988 or #48138) carrying both the Cas9 and puromycin-resistance or EGFP gene, respectively. HeLa cells were transfected with the gRNA-containing Cas9 vector using Mectafectene Pro (Biontex #T020). For vector with the puromycin resistance gene, HeLa cells were treated with 1 μg/mL of puromycin 24 h post transfection for 36 h. Single cells were then sorted and plated into 96-well plates. For vector with EGFP gene, EGFP-positive cells were sorted by FACS and plated into 96-well plates 48 h post transfection. Single colonies were then expanded and screened by immunoblotting. Once knockout were confirmed by immunoblotting, genomic DNA were extracted using the GenElute mammalian genomic DNA miniprep kit (Sigma #G1N350) and the area of interest amplified by PCR. The amplified region was ligated into the PGEM vector (Promega #A3600) and sequenced to identify indels. To generate double knockouts, the parental cell lines were transfected sequentially with gRNAs for each protein at a time. Guide RNAs include NIPSNAP1 (GCGGCTCCAACATGGCTCCG, GCAGCATCTCTGTGACGGCG), NIPSNAP2 (CGAGGCGCCGAGCAAGATGG, GTCTTCTCGAGATCTGTTGC), NDP52 (CCTCGTCGAAAGGATTGGAT) and ATG7 (AGAAGAAGCTGAACGAGTAT).

Generation of Stable Cell Lines and Reconstitution of KO Cell Lines

Stable cell lines and reconstituted KO cell lines were generated using the pMXs vector with Puromycin or Neomycin (G418) resistance gene. NIPSNAP1, NIPSNAP2, NIPSNAP1del1–24, NIPSNAP1-MYC, NIPSNAP2-MYC, NIPSNAP1-EGFP, NIPSNAP2-EGFPi and mCherry-EGFP-OMP25TM were PCR amplified and ligated into the pMXs vector using BamH1 and Not1 sites. These retroviral vectors were packaged in HEK293 cells and resulting viral particles were used to transduce both HeLa WT and N1/N2 DKO cells three times for 24h each in combination with 8 μg/ml Hexadimethrine bromide (Sigma, #H9268). Protein expression was optimized by selection in appropriate antibiotics.

CRISPR/Cas9 Genome Editing in Zebrafish

Zebrafish nipsnap1 KO embryos were generated using CRISPR/Cas9 technology as described (Jao et al., 2013). Briefly, the web tool “CHOPCHOP” was used to design a set of three sgRNA molecules (designated G1-G3), targeting exon 1, 4 and 7 of the zebrafish nipsnap1 gene, respectively. A plasmid encoding zebrafish codon-optimized Cas9 (pCS2-nls-zCas9-nls) was procured from Addgene (Plasmid ID 47929). sgRNA and Cas9 mRNA were generated essentially as described (Jao et al., 2013). (Guide#1-Exon1attaatacgactcactataGGAAATGCTGCTGTGTGTTGgttttagagctagaaatagc, Guide#2-Exon4aattaatacgactcactataGG AAGCTGGAACACATGGTAgttttagagctagaaatagc, Guide#3-Exon7aattaatacgactcactataGGCGGATTCTTCACACAGATgttttagagcta gaaatagc). Synthesized sgRNA integrity was checked on 1% TBE gel. Individual sgRNAs (50–200 ng/μL) were mixed with capped and poly-adenylated Cas9 mRNA (300 pg/μL) before microinjection into the 1 cell stage. Nipsnap1 depletion was validated by immunoblotting.

Genotyping of nipsnap1 Mutants

The zebrafish line carrying the heterozygous nipsnap1sa14357 mutant allele (Zebrafish Mutation Project (ZMP)) (Kettleborough et al., 2013) was verified by PCR and sequencing of genomic DNA from adult fish fin-clips. DNA was extracted from single embryos or fin clips from adult fish using the HotSHOT protocol (Meeker et al., 2007). Purified PCR or gel extracted PCR products (Zymoclean Gel DNA Recovery Kit, Zymo Research) were then cloned into Blunt End TOPO Vector. Colonies were picked and grown in liquid broth with the appropriate antibiotics. Plasmid DNA was isolated, purified and sent for sequencing. 25 μL PCR reactions consisted of 0.5 μL Phusion High Fidelity DNA Polymerase (Thermo scientific), 5 μL 5X Phusion HF Buffer, 2 μL dNTP (2.5 mM), 0.5 μL forward primer (10 μM) (5′TGCATCTGTGGAGATACTCTGGAGG3′), 0.5 μL reverse primer (10 μM) (5′ CCCATAAATGATGCACTACATAC3′), 5 μL genomic DNA and 11.5 μL of nuclease free water. The Bio-Rad S1000 thermal cycler with the following program was used for amplification: 90 sec at 95 °C, 30 cycles of: 30 sec at 95 °C, 30 sec at 63.1 °C and 30 sec at 72 °C, followed by 72 °C for 5 min. Sequencing was performed using the reverse M13 primer. Sequencing traces were analyzed using DNASTAR (Version 14) and ApE (A Plasmid Editor v.2.0.47). Mutations were identified manually by comparing mutant and WT traces.

RT-PCR/qPCR Analysis

Total RNA was extracted from approximately 50 zebrafish embryos at the indicated developmental stages with Trizol (Invitrogen, Inc., USA). The RNA quality was checked by 260/280 nm absorption using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., USA) and gel analysis. First-strand cDNA was prepared using the SuperScript First-Strand Synthesis System according to manufacturer’s instructions (Thermo Fisher). Amplification was performed with KAPA SYBR FAST qPCR Kit and the CFx96 real-time PCR system (Bio-Rad). In brief, reactions were done in 10 μL volumes containing 400 nM of each primer, 2.5 μL cDNA (3 ng), 5 μL2 × KAPA SYBR Green Master Mix Reagent and the rest nuclease free water. Reactions were run using the manufacturer’s recommended cycling parameters of 50°C for 2 min, 95°C for 5 min, 40 cycles of 94°C for 15 s, and 60°C for 30 s. All reactions were performed in triplicate. Relative expression levels were calculated after correction for the expression of β-actin as an endogenous reference using the 2−ΔΔC(t) method. Amplification specificity/quality was assessed by analyzing the melting curve. The primer sequences used for Nipsnap1 were forward primer (5’TCCCTGTGAAGTTGTTGGAAGCTG3’) and reverse primer (5’TGCACTGCCTGATCCTGTTCAC3’); for NIPSNAP2 were forward primer (5’TGCACTTGTGGAGGTACAGAGG3’) and reverse primer (5’TGCGGTACTCCAGAAA CTCCTTG3’) and for β-actin were forward primer (5’ CGAACGACCAACCTAAACCTCTCG3’) and reverse primer (5’ ATGCGC CATACAGAGCAGAAGC3’).

Whole-Mount In Situ Hybridization

Whole-mount in situ hybridizations for nipsnap1 and tyrosine hydroxylase 1 (TH1) were performed as previously described (Thisse and Thisse, 2008) using digoxigenin-labelled riboprobes. Primer sequences for nipsnap1 sense and antisense probes were; 5’UTR probe: forward primer (5’CGGAATCAACAGACAAGGCC3’), reverse primer (5’TACTCAGGCTTGACATTGTG3’), internal probe: forward primer (5’ACTCCAATCTGCTCTCCAAG3’), reverse primer (5’TCTCTTCTCTGGACTGCAGG3’), 3’UTR probe: forward primer (5’CAGATCATATCAGCTACTGC3’), reverse primer (5’ACATGCTGTATAGCTCAAGC3’). The TH1 plasmid was a kind gift from Wolfgang Driever (Department of Biology I, University of Freiburg).

Tandem-Tag Transgenic Mitofish Generation and Imaging

The pME-EGFP no stop vector from the Tol2 kit was cut with NCoI restriction enzyme and then dephosphorylated with calf intestinal phosphatase. This was later phosphorylated with T4 polynucleotide kinase and annealed with mitochondrial localization signal (MLS) of zebrafish COXVIII (Kim et al., 2008). The oligo sequences used for annealing were forward primer (5’cATGTCTGGACTTCTGAGGGGACTAGCTCGCGTCCGCGCCGCTCCGGTTCTGCGGGGATCCACGATCACCCAGCGAGCCAACCTCGTTACGCGAgc3’) and reverse primer (5’catggcTCGCGTAACGAGGTTGGCTCGCTGGGTGATCGTGGATCCCCGCAGAACCGGAGCGGCGCGGACGCGAGCTAGTCCCCTCAGAAGTCCAGA3’). Gibson assembly was used to generate pTol2-CMV-MLS-EGFP-Cherry with linearized pTol2mini and PCR products from the following primers: CMVFw (5’ctgatgcccagtttaatttaaatagatctggccatCGATGTACGGGCCAGATATAC3’), CMVRev (5’cctcagaagtccagacatCCTATAGTGAGTCGTATTAATTTCG3’), MLSGFPFw (5’aatacgactcactataggATGTCTGGACTTCTGAGGG3’), MLSGFPRev (5’ctcctcgcccttgctcacCCTTGAATTCCCAGATCTTC3’), mCherryFw (5’agatctgggaattcaaggGTGAGCAAGGGCGAGGAG3’) and mCherryRev (5’aactagagattcttgtttaagcttgatatccatggACGCCTTAAGATACATTGATGAGTTTG3’). Templates for PCR were used from Tol2 Kit. The MLS-EGFP-mCherry was subcloned into iTol2 vector using XhoI and AgeI. 35 pg (final concentration) of iTol2 MLS-EGFP-mCherry vector and 50 pg (final concentration) of in-vitro transcribed transposase mRNA (in-vitro transcribed from linearized pCS2FA-transposase vector from the Tol2 kit) was injected into the 1 cell stage of control (WT) and Nipsnap1 mutants. Injected embryos were raised to adulthood (F0) and out-crossed to wild-type fish to identify transgenic founders. Control (WT) tandem-tagged mitofish transgenic founders and Nipsnap1 mutant tandem-tagged mitofish transgenic founders were incrossed respectively. Resulting respective larvae (F1) were fixed in 4% PFA (pH 7.2) overnight at 3dpf and co-stained with 50ug Hoechst reagent for 3–4 h at room temperature. Each larva was mounted on depression slides using low melting point agarose. Confocal images were obtained using an Apochromat 40x/1.2 WC or 60x/1.2 oil DIC objective on an LSM 780 microscope (Zeiss). Red and yellow dots were counted manually for each cell and the ratio of red to yellow dots (per cell) were interpreted as mitophagy.

Zebrafish Rescue Experiments

Full length wildtype zebrafish nipsnap1 was amplified using the oligos: FP – ATGATGGCTACCGCACGACCTCTGC and RP – TTA CTGCAGAGGTGAATGTACCATG. Amplified product was cloned into zero-blunt end TOPO vector (ThermoFisher). Capped full-length zebrafish wildtype nipsnap1 mRNA was transcribed from linearized zero-blunt TOPO vector using mMessage mMachine (Ambion) and later poly(A) tailed using the poly(A) tailing kit (ThermoFisher). 75pg of the transcribed mRNA was injected into 1 cell stage of Nipsnap1 mutant tandem-tagged transgenic larvae. Larvae at 3dpf were fixed in 4% PFA (pH 7.2) overnight at 3dpf and co-stained with 50ug Hoechst reagent for 3–4 h at room temperature. Each larva was mounted on depression slides using low melting point agarose. Confocal images were obtained using an Apochromat 40x/1.2 WC or 60x/1.2 oil DIC objective on an LSM 780 microscope (Zeiss). Red and yellow dots were counted manually for each cell and the ratio of red to yellow dots (per cell) were interpreted as mitophagy.

Immunoblotting, Immunoprecipitation and Mass Spectrometry

HeLa cells seeded in either 6-well plates or 6 cm plates were treated as indicated. Cells were lysed in 1xSDS (50 mM Tris pH 7.4, 2% SDS, 10% Glycerol) supplemented with 200 mM dithiothreitol (DTT, Sigma, #D0632) and heated to 99°C for 8–10 min. Protein concentration was determined by Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermofischer Scientific, #23227). 10–40 μg protein per sample were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membrane, stained with Ponceau S (Sigma, #P3504) and immunoblotted by the indicated antibodies. For immunoprecipitation, HeLa cells stably expressing EGFP or EGFP tagged proteins were immunoprecipitated by GFP-TRAP (Chromotek, # gta-20) while those expressing MYC-tagged proteins were immunoprecipitated using MYC-TRAP (Chromotek, # yta-20). HeLa cells transiently transfected with 3xFLAG-tagged proteins were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG M2 affinity gel (Sigma, #A2220). Cells were lyses in modified RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl pH 7.4, 120 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA pH 8.0, 1% NP-40, 0,25% Triton X-100) supplemented with cOmplete Mini EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail tablets (Roche AppliedScience, #11836170001) on ice for 30 min, followed by centrifugation at 10.000 × g for 10 min. Supernatants were then incubated with either GFP-TRAP or anti-FLAG M2 affinity gel for 2 h and washed five times with RIPA buffer. FLAG-tagged protein were eluted by flag-peptide in RIPA buffer before boiling in 2x SDS gel loading buffer, while GFP-tagged protein were eluted by boiling in 2X SDS gel loading buffer. GFP-tagged proteins were also immunoprecipitated using the μMACS GFP Isolation Kit (Miltenyi Biotec) according to the instruction manual. For immunoprecipitation of endogenous ALFY, ALFY+/+ or ALFY−/− MEFs were incubated with lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 20 mM Hepes pH 7.4, 1% NP40, protease inhibitors and phosphatase inhibitors cocktail (Roche)) for 20 min, 4°C, then centrifuged for 10 min, 18.000 × g, and supernatant containing 5 mg of protein was incubated with 20 μL of anti-ALFY antibody for 2 h, 4°C, followed by 1 h incubation with 20 μL of protein G Dynabeads (ThermoFisher). After incubation, beads were washed four times in washing buffer (150 mM NaCl, 20 mM Hepes pH 7.5, 0,1% NP40) and bound proteins were eluted by boiling with 0.25% SDS in washing buffer. For immunoblotting of proteins from zebrafish, embryos were de-yolked and homogenized in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8), 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 1% NP-40, 0.5% Sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, protease inhibitor cocktail and (Roche)) 3 d post injections. Protein lysates were separated on Criterion TGX Gels (Bio-Rad), transferred to PVDF membrane (Millipore), and incubated overnight at 4°C with the indicated primary antibodies, followed by 1 h incubation with far-red/green fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies (LI-COR) and analysis on a LI-COR Odyssey Imaging Systems Application. Approximately 107 HeLa cells stably transfected with NIPSNA1-EGFP-3xHA, NIPSNAP1-EGFP-3xFLAG or PDHA1-EGFP-3xHA were washed 2 times with ice-cold PBS, then scraped in 1ml of ice-cold KPBS (136mM KCl, 10mM KH2PO4, pH 7.25) and centrifuged at 1000g, 4°C for 2 min. The pellet was resuspended in 1ml of KPBS and lysed by 25 plunger strokes in homogenizer vessel (VWR, cat. no. 89026–386/89026–398). Lysate was centrifuged at 1000g, 4°C for 2 min and supernatant was incubated for 5min at 4°C with 100μl of anti-HA magnetic beads (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #88837), then washed 3 times with 1ml KPBS and subjected to SDS PAGE and immunoblotting. For protein analysis by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS), the SDS-PAGE was cut in 12 bands, each band digested with 0.1 μg trypsin (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) for 16 h at 37°C, the generated peptides were purified using a ZipTip μ-C18 (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA), and dried using a Speed Vac concentrator (Concentrator Plus, Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). The tryptic peptides were dissolved in 10 μL 0.1% formic acid/2% acetonitrile and 5 μL analyzed using an Ultimate 3000 nano-HPLC system connected to a LTQ-Orbitrap XL mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany) equipped with a nano electrospray ion source. For liquid chromatography separation, an Acclaim PepMap 100 column (C18, 3 μm beads, 100 Å, 75 μm inner diameter, 50 cm length) (Dionex, Sunnyvale CA, USA) was used with a flow rate of 300 nL/min and a solvent gradient of 4–35% B in 47 min, to 50% B in 10 min and then to 80% B in 1 min. Solvent A was 0.1% formic acid and solvent B was 0.1% formic acid/90% acetonitrile. The mass spectrometer was operated in the data-dependent mode to automatically switch between MS and MS/MS acquisition. Survey full scan MS spectra (from m/z 300 to 2,000) were acquired with the resolution R = 60,000 at m/z 400 after accumulation to a target of 1e6. The maximum allowed ion accumulation times were 60 ms. The method used allowed sequential isolation of up to the seven most intense ions, depending on signal intensity (intensity threshold 1.7e4), for fragmentation using collision induced dissociation (CID) at a target value of 10,000 charges and NCE 35 in the linear ion trap. Target ions already selected for MS/MS were dynamically excluded for 60 sec. For accurate mass measurements, the lock mass option was enabled in MS mode. Data were acquired using Xcalibur v2.5.5 and raw files were processed to generate peak list in Mascot generic format (*.mgf) using ProteoWizard release version 3.0.331. Database searches were performed using Mascot in-house version 2.4.0 to search the SwissProt database (Mouse, 16,460 proteins) assuming the digestion enzyme trypsin, at maximum one missed cleavage site, fragment ion mass tolerance of 0.6 Da, parent ion tolerance of 10 ppm, propionamidylation of cysteines, oxidation of methionines, and acetylation of the protein N-terminus as variable modifications. Scaffold (version Scaffold_4.3.4, Proteome Software Inc., Portland, OR) was used to validate MS/MS based peptide and protein identification. Peptide identifications were accepted if they could be established at greater than 95.0% probability by the Peptide Prophet with Scaffold delta-mass correction. Protein identifications were accepted if they could be established at greater than 99.0% probability and contained at least two identified peptides. Protein probabilities were assigned by the Protein Prophet algorithm.

Proximity Biotinylation Assay

Approximately 5×106 HeLa cells stably transfected with NIPSNAP1-APEX2 were incubated for 30 min with 500μM of biothin tyramide in complete medium, followed by treatment for 1min with 1mM H2O2 and washing 3 times with 5 ml of quenching solution (10mM sodium azide, 10mM sodium ascorbate, 5mM trolox in PBS). Cells then were scraped in 1ml of quenching solution, centrifuged at 3000g for 10min. 4°C, and pellet was lysed in 2xSDS gel loading buffer and subjected to SDS PAGE and immunoblotting with indicated antibodies.

Phos-tag SDS-PAGE Analysis

WT or NIPSNAP1/2 KO cells were plated in 6-well plate and treated 24h after transfection with 20μM CCCP for 0.5, 1, 2 and 4h. After treatment cells were lysed in 20mM Tris, pH7,5, 150mM NaCl, 1% Triton and either left untreated or were treated with lambda protein phosphatase (400U phosphatase, 1xPMP buffer, 1mM MnCl2, 30°C, 30min). Samples were resolved on 8% SDS PAGE containing 50μM Phos-tag and 100μM MnCl2, transferred to nitrocellulose membrane after washing gel 3×10min in 10mM EDTA and immunostained with NIPSNAP1/2 or actin antibodies.

Live Cell and Confocal Immunofluorescence Microscopy

HeLa cells were seeded in 8-well Lab-tek chamber coverglasses (Thermofischer Scientific, # 155409 &155411) or on coverslips (VWR, #631–0150) and treated as indicated. Cells were either examined directly or fixed. Cells were fixed for 10 min at 37 °C in preheated (37 °C) 4% PFA, followed by permeabilization in 0.1% Triton X-100 for 5 min and blocking with 3% goat serum for 30 min. Cells were incubated with primary antibodies diluted in PBS for 1 h at room temperature and washed five times with PBS, followed by incubation in Alexa Fluor 488-, Fluor 555-, or Fluor 647-conjugated secondary antibodies diluted in PBS for 30 min at room temperature and washed five times with PBS. During this final wash step, cells were incubated with 10 μg/mL DAPI diluted in PBS for 10 min. Confocal images were obtained using an Apochromat 40x/1.2 WC or 60x/1.2 oil DIC objective on an LSM 780 microscope (Zeiss) or Leica TCS SP5 confocal microscope, 63×1.2W-objective.

Long-Lived Protein Degradation

To measure the degradation of long-lived proteins by autophagy, cellular proteins were first labelled with 0.25 mCi/m L-14C-valine (Perkin Elmer) for 24 h in GIBCO-RPMI 1640 medium (Invitrogen) containing 10% FBS. The cells were washed and then chased for 16 h in nonradioactive Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Invitrogen) containing 10% FBS and 10 mM valine (Sigma), to allow degradation of short-lived proteins. The cells were washed twice with EBSS (Invitrogen), and starved or not for 4 h in the presence or absence of 10 mM 3-methyladenine (Sigma). The medium was then collected and added to 50% Trichloroacetic acid, followed by 2 h incubation at 4 °C and centrifugation to pellet any contaminants. 0.2 M potassium hydroxide solution was added to the cells for 2 h before the lysate was collected. Ultima Gold LSC cocktail (Perkin Elmer) was added to the medium and cell samples and protein degradation was determined by measuring the ratio of radioactivity in the medium relative to the total radioactivity detected by a liquid scintillation analyser (Tri-Carb 3100TR, Perkin Elmer), counting 3 min per sample.

Recombinant Protein Expression, In-Vitro Translation and GST-Pulldown Assay

GST and GST-fusion proteins were expressed in SoluBL21 Competent Escherichia coli (Genlantis, #C700200) and purified by immobilization on Glutathione Sepharose 4 Fast Flow beads (GE Healthcare, #17–5132-01). MYC-tagged proteins were in-vitro translated in the presence of radioactive 35S-methionine using the TNT T7 Reticulocyte Lysate System (Promega, #l4610). For GST-pulldown assay, 10 μL of in-vitro translated protein was pre-cleared with 10 μL of empty Glutathione sepharose beads in 100 μL of NETN buffer (50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% NP-40) supplemented with cOmplete Mini EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail tablets for 30 min at 4 °C to remove unspecific binding. The precleared mixture was then incubated with the immobilized GST-fusion protein and incubated for 1–2 h at 4 °C. The beads were washed five times with NETN buffer (500 μL NETN buffer followed by centrifugation at 2500 × g for 1 min). After the last wash, 2xSDS gel-loading buffer (100 mM Tris pH 7.4, 4% SDS, 20% Glycerol, 0.2% Bromophenol blue and 200 mM dithiothreitol DTT (Sigma, # D0632) was added and boiled for 10 min followed by SDS-PAGE. Gels were stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250 Dye (ThermoFisher Scientific, #20278) for 30 min to visualized the fusion proteins, vacuumed-dried (in Saskia HochVakuum combined with BIO-RAD Gel dryer model 583, #1651746) for 30 min. Radioactive signals were detected by Fujifilm bioimaging analyzer BAS-5000 (Fujifilm) and quantified with ScienceLab ImageGuage software (Fujifilm).

Subcellular Fractionation, Proteinase K/trypsin Treatment and Sodium Carbonate Extraction

Subcellular fractionation was performed with a QProteome mitochondria isolation kit (Quiagen) according to the instruction manual. In brief, 107 HeLa cells were resuspended in 1 mL of lysis buffer, incubated for 10 min at 4°C and centrifuged at 1000 × g for 10 min. The supernatant was transferred into a separate tube as cytosolic fraction, while the pellet was resuspended in 1.5 mL of ice-cold disruption buffer, rapidly passed through 21 g needle 10 times to disrupt cells and centrifuged at 1000 × g for 10 min, 4°C. The pellet was saved as nuclear fraction, while the supernatant was re-centrifuged at 6000 × g for 10 min, 4°C. The pellet obtained after centrifugation comprised the mitochondrial fraction, while the supernatant contained the microsomal fraction. For PK digestion, mitochondria were resuspended in Mitochondrial buffer (MB) (210 mM mannitol, 70 mM sucrose, 10 mM HEPES, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.5) with 50 or 100 μg/mL of PK and incubated 30 min at RT. For trypsin digestion, mitochondria were re-suspended in trypsin digestion buffer (10 mM sucrose, 0.1 mM EGTA/Tris and 10 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.4) with 200 μg/mL of trypsin. Both reactions were stopped by addition of 5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. For the analysis of integral membrane proteins, the mitochondrial fraction was resuspended in MB buffer or MB buffer containing freshly prepared 0.1 M Na2CO3 (pH 11.5) and incubated on ice for 30 min. The insoluble membrane fraction was centrifuged at 16.000 × g for 15 min.

Mitophagy Assay

Hela cells seeded in 6 cm dishes (or 24 well plates for confocal microscopy) were either treated with 10 μM Carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazine (CCCP) or a combination of 10 μM Oligomycin and 4 μM Antimycin A for indicated times. Mitophagy was analyzed by measuring the degradation of cytochrome C oxidase subunit II (COXII), a mtDNA encoded inner membrane protein, and TIMM23, a nuclear encoded mitochondria inner membrane protein. For confocal miscroscopic analyses of mitophagy, we immunostained for mtDNA nucleoids and TIMM23. In addition, we also used a tandem tagged mCherry-EGFP-OMP25TM mitophagy reporter for visualizing acidified mCherry dots in the lysosome.

In Vivo Ubiquitination Assay

HeLa WT cells stably expressing mCherry-PARKIN were transfected with NIPSNAP1-MYC, NIPSNAP2-MYC, MFN2-MYC and HA-UBIQUITIN. 24h after transfection cells were treated with CCCP and MG132 for 3h before harvesting. Cells were collected in lysis buffer (2% SDS, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0) supplemented with cOmplete Mini EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail tablets (Roche Applied Science, #11836170001) and N-ethylmaleimide (Sigma,#E1271)) and heated at 90 °C for 10 min to denature proteins. Lysates were diluted 1:10 in dilution buffer (1% TritonX-100, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0) and myc-tagged proteins immunoprecipitated with MYC-TRAP. Ubiquitination was detected by immunoblotting with HA antibody.

In Vitro Kinase Assay