Abstract

Introduction

We recently developed a new therapy using effective-mononuclear cells (E-MNCs) and demonstrated its efficacy in treating radiation-damaged salivary glands (SGs). The activity of E-MNCs in part involves constituent immunoregulatory -CD11b/macrophage scavenger receptor 1(Msr1)-positive-M2 macrophages, which exert anti-inflammatory and tissue-regenerating effects via phagocytic clearance of extracellular high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1). Focusing on the phenomena, this study investigated significance of regulating the HMGB1/toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)/receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) signaling pathway in the treatment of SG dysfunction caused by radiation damage.

Methods

E-MNCs were transplanted into radiation-damaged mice SGs, and changes of TLR4/RAGE expression were observed. Furthermore, the activation of downstream signals was investigated in both intact SGs and cultured SG epithelial cells after irradiation. Subsequently, TLR4-knock-out (KO) mice were employed to examine how HMGB1/TLR4/RAGE signaling affected damage progression.

Results

Expression of both TLR4 and RAGE was diminished in ductal cells and macrophages/vascular endothelial cells of damaged SGs with E-MNC transplantation, respectively. Meanwhile, expression of TLR2/4 and RAGE in damaged SGs markedly increased in association with extracellular HMGB1 accumulation. Downstream signals were activated, and intranuclear localization of phospho-nuclear factor-kappa B (p–NF–KB) in ductal cells and production of IL-6, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and interferon-γ (IFN-γ) were observed. Additionally, culture supernatant of irradiated cultured SG epithelial cells contained damaged associated molecular pattern (DAMP)/senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) factors. Treatment of cultured SG epithelial cells with this supernatant activated TLR4 signaling pathway and induced cellular senescence. In TLR4-KO mice, onset of radiogenic SG dysfunction was markedly delayed. However, TLR2/RAGE signalings were alternatively activated, and SG function was impaired.

Conclusions

Clearance of DAMPs such as HMGB1 may attenuate sterile inflammation in damaged SGs via suppression of the TLR4/RAGE signaling pathway. This cellular mechanism may have significant implications for the development of future cell-based regenerative therapies.

1. Introduction

Xerostomia due to radiation-induced salivary gland (SG) dysfunction is a common side effect of radiotherapy in patients with head and neck cancer. Unfortunately, currently available treatments only target symptoms in order to relieve some discomfort experienced by xerostomia patients. Therefore, a variety of regenerative approaches using gene therapy, tissue engineering, and cell-based therapies have been investigated, with the goal of developing effective radical treatments for radiation-induced SG atrophy [[1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9]].

We recently developed a novel cell-based therapy using a primary culture system, termed as ‘5G-culture’, to induce the differentiation of effectively conditioned mononuclear cells (effective-mononuclear cells; E-MNCs) from autologous peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PB-MNCs) using a hematopoietic stem cell culture medium supplemented with five growth factors (Flt-3 ligand, interleukin-6; IL-6, stem cell factor, thrombopoietin, and vascular endothelial growth factor). We then demonstrated the therapeutic potential of E-MNC therapy to induce tissue regeneration and restore saliva secretion in damaged SGs using a mouse model of irradiation (IR) or primary Sjögren syndrome (SS) [[10], [11], [12]].

E-MNCs consist of heterogeneous cell populations, including expanded T helper 2 lymphocytes (Th2) and endothelial progenitor cells. Notably, CD11b/CD206-positive M2-macrophages are specifically induced during 5G-culture. Previous studies reported that treatment with M2 macrophages, which exhibit anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory properties, can alleviate symptoms of certain chronic inflammatory disorders, especially those of autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, glomerulonephritis, multiple sclerosis, and encephalomyelitis [[13], [14], [15]]. It is widely recognized that typical M2 macrophages potently suppress the proliferation of CD4-positive T cells via secretion of IL-10 [16]. Indeed, our previous studies using mouse E-MNCs revealed that PB-MNCs robustly acquired anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory characteristics through our 5G-culture system [10,12]. Local administration of E-MNCs induced the migration of recipient anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages and suppressed the infiltration of CD4-positive lymphocytes into SGs of SS model mice [12]. Therefore, CD11b/CD206-positive M2-macrophages and supporting cells (e.g., Th2 cells) among E-MNCs are likely the principal mediators behind these therapeutic effects.

Through studies to identify the principal E-MNC components that modulate SG atrophy and dysfunction, we found that immunomodulatory (class A scavenger receptor Msr1-and CD11b-positive) M2 macrophages suppress sterile inflammation and play a role in restoring mouse SG tissues damaged by IR [11]. These therapeutic effects of immunomodulatory M2 macrophages were attributed to the suppression of inflammation through phagocytic elimination of extracellular high-mobility-group box 1 (HMGB1), which acts as damaged associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), thereby promoting tissue regeneration via the production of IL-10 and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1) in radiation-damaged SG tissues. Considerable evidence indicates that extracellular HMGB1 derived from damaged tissues can trigger sterile inflammation. Several studies conducted over the past decade using murine models of ischemic stroke, heart failure, epilepsy, and myositis have reported that extracellular HMGB1 accelerates inflammation after tissue injury [[17], [18], [19], [20]]. Furthermore, increased levels of extracellular HMGB1 were observed in salivary glands of patients with SS [21], and downregulation of HMGB1/toll-like receptor (TLR)5 signaling plays a role in protecting SGs from radiation damage [22]. Other studies have shown that DAMP-neutralizing antibodies, including an anti-HMGB1 neutralizing antibody, contribute to the suppression of sterile inflammation in several diseases, such as polymyositis, Parkinson's disease, and respiratory syncytial virus infection [20,23,24]. Another study reported that enhanced DAMP clearance by infiltrating macrophages induces a pro-inflammatory to anti-inflammatory phenotypic shift via induction of macrophage scavenger receptor (Msr1) expression, thereby resolving sterile inflammation and preventing the aggravation of cerebral ischemic stroke effects in the brain [19]. These M2 macrophages were also identified as an important source of IL-10 and IGF1 in immune metabolism and tissue regeneration [25]. However, the understanding of the cellular mechanism by which E-MNC therapy modulates SG atrophy and dysfunction remains incomplete. To address this gap in knowledge, the present study investigates the significance of regulating the HMGB1/TLR4/receptor for advanced glycation end-products (RAGE) signaling pathway in treating radiation-damaged SG dysfunction.

In this study, we found that the accumulation of extracellular HMGB1 released from radiogenic-injured cells induces the expression of TLR4 in duct cells and RAGE in blood vessels and macrophages, and the expression levels of these factors increase over time post-IR. Favoring the clearance of accumulated DAMPs (such as HMGB1) and subsequent suppression of the TLR4/RAGE signaling pathway was identified as a potential therapeutic approach for triggering tissue regeneration and the resolution of sterile inflammation. However, the use of receptor-targeting agents can also lead to the suppression of host defense responses (e.g., innate immunity) and serious adverse effects. In this respect, cell-based therapies utilizing macrophages, which play a role in phagocytic elimination of DAMPs and promoting the development of an anti-inflammatory microenvironment, can be an attractive and promising approach for the treatment of SG atrophy and dysfunction resulting from radiation therapy.

2. Materials & methods

2.1. Animals

C57BL/6JJc mice (CLEA Japan Inc., Tokyo, Japan) were used for E-MNC culture. In transplantation experiments, female C57BL/6JJc mice were used as recipients and male C57BL/6JJc mice as donors. In some experiments, TLR4-KO (C57BL/6) mice (Oriental Bio Service, Inc., Kyoto, Japan) were used to verify the role of TLR4. Starting at 8 weeks of age, the body weight of mice was monitored once per week. All mice were kept under clean conventional conditions at the Nagasaki University Animal Center. All experimental procedures were performed in accordance with guidelines approved by the Nagasaki University Ethics Committee (approval numbers 20010615875 and 22032817822).

2.2. E-MNC culture

Mouse PB-MNCs were cultured using a specific culture method (Cell Axia Inc., Tokyo, Japan) that we established and designated in our previous work [[10], [11], [12]] (Fig. 1A). Briefly, isolated PB-MNCs were plated into wells of 6-well Primaria plates (BD Biosciences, CA, USA) under specific conditions at a density of 2 × 106 cells/well in 2 mL of Stem Line II medium (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) supplemented with five mouse recombinant proteins (Table 1). After 5 days of culture, E-MNCs were harvested for subsequent experiments.

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram describing 5G-culture and the characteristics of mouse E-MNCs. (A) PB-MNCs were cultured for 5 days in serum-free medium supplemented with five recombinant proteins: TPO, VEGF, SCF, Flt-3 ligand, and IL-6. After cultivation, effective-mononuclear cells (E-MNCs) were obtained. (B) Flow cytometry analysis. Percentages of M1 (CD11b+/CD206−) and M2 (CD11b+/CD206+) macrophages among PB-MNCs and E-MNCs, and CCR2−/galectin 3+ cells among the CD11b+ population.

Table 1.

Growth factors used for culture of mouse E-MNCs.

| Recombinant protein | Company, catalog No. | Final concentration (ng/ml) |

|---|---|---|

| SCF | Prepotech, #250-03 | 100 |

| Flt-3 ligand | Prepotech, #250-31L | 100 |

| TPO | Prepotech, #315-14 | 20 |

| VEGF | Prepotech, #450-32 | 50 |

| IL-6 | Prepotech, #216-16 | 20 |

2.3. Characterization of PB-MNCs and E-MNCs

Flow cytometry analysis was employed to identify macrophage subpopulations (M1 and M0: CD11b+/CD206−, and M2: CD11b+/CD206+) among PB-MNCs and E-MNCs. In addition, the immunomodulatory phenotype of the M2-macrophage fraction was assessed by staining for specific surface antigens (galectin 3+/CCR2−) along with propidium iodide (PI) staining to assess cell viability. The antibodies used in the study are listed in Table 2. Preparation of cell samples and analysis by flow cytometry were conducted as described in our previous study [10].

Table 2.

Antibodies and isotype controls used for flow cytometry.

| Antibody/Isotype | Company, catalog No. |

|---|---|

| APC-Cy7 anti-mouse/human CD11b | Biolegend, #101225 |

| APC-Cy7 rat IgG2b, κ Isotype Ctrl | Biolegend, #400623 |

| APC anti-mouse CD206 (MMR) | Prepotech, #250-31L |

| APC rat IgG2a, κ isotype Ctrl | Biolegend, #400713 |

| APC anti-mouse CCR2 (CD192) | R&D Systems, #FAB5538A |

| APC Rat IgG2b, κ Isotype Ctrl | Biolegend, #400611 |

| PE-Cy7 anti-mouse/human Mac-2 (Galectin-3) | Biolegend, #125417 |

| PE-Cy7 rat IgG2a, κ isotype Ctrl | Biolegend, #400521 |

| FITC anti-mouse CD326 (EpCAM) | Biolegend, #118207 |

| FITC Rat IgG2a, k Isotype Ctrl | Biolegend, #400505 |

2.4. Histological observation of submandibular glands

Submandibular glands were harvested and either embedded in paraffin wax or cryo-embedded. For wax embedding, the tissues were fixed in 4 % paraformaldehyde (PFA) and embedded in paraffin. After deparaffinization and rehydration, the tissue samples were sectioned and stained. Sections (5-μm thick) were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and Masson's trichrome and examined microscopically. Senescence-associated beta-galactosidase (SA-β-Gal) assays were performed according to the manufacturer's protocol (Cell Signaling Technology, MA, USA).

Immunohistological staining was performed as described previously [10]. In brief, immunofluorescence analyses were performed using rabbit anti-mouse TLR4 antibody (1:100; abcam, MA, USA), mouse anti-mouse Aquaporin-5 (AQP5) antibody (1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA, USA), rabbit anti-mouse Cytokeratin-14 (KRT14) antibody (1:100; Proteintech, IL, USA), rabbit anti-mouse TLR2 antibody (1:100; abcam), rabbit anti-mouse RAGE antibody (1:50; abcam), rabbit anti-mouse CD31 antibody (1:100; abcam), rabbit anti-mouse F4/80 antibody (1:50; abcam), and mouse anti-mouse phospho-nuclear factor-kappa B (p–NF–κB) antibody (1:50; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Alexa Fluor 488– or 546–labeled antibodies (1:200; Thermo Fisher Scientific Life Sciences, MA, USA) were used for secondary staining to visualize primary antibodies. Nuclei were stained with 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Vector Laboratories, CA, USA). All antibodies were diluted in blocking solution. SA-β-Gal– and RAGE-positive cells were counted in a blinded manner under × 200 magnification (n = 5 at each time point, and 5 different fields/n = 1).

2.5. IR and time course analysis of E-MNC transplantation

Mouse SGs were irradiated as described previously [10,11]. In brief, 8-week-old female C57BL/6 mice were anesthetized with a mixture of anesthetic agents (domitor, 1 mg/mL; midazolam, 10 mg/2 mL; and butorphanol tartrate, 5 mg/mL) at 0.1 mL/10 g body weight given by intraperitoneal (ip) injection, and the mice were then restrained in a container for IR. The SGs were exposed to a single dose of 12-Gy using gamma rays from a PS-3100SB source (Pony Industry Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan). The IR field was restricted to the head and neck area to guarantee <10 % beam strength in the rest of the body. Next, E-MNCs (2 × 105 cells per gland, a total of 4 × 105 cells) were injected directly into the SGs at 7 days post-IR. At the time of sacrifice (1, 2, 4, 8, and 12 weeks post-IR), the submandibular glands were harvested.

2.6. Salivary flow rate (SFR) determination

To evaluate the secretory function of SGs (salivary flow rate: SFR), whole saliva was collected and measured gravimetrically. SFR was determined at 2, 4, 8, and 12 weeks post-IR (n ≥ 3/group at each time point) in parallel with measurement of body weight.

2.7. Analysis of gene expression in SGs and cultured salivary epithelial cells

mRNA expression was assessed using real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) as described in our previous study [10]. Expression of TLR-2, -3, -4, -7, -8, -9, collagen-1, elastin, RAGE, NF-κB, myeloid differentiation factor 8 (MyD88), TRIF-related adaptor molecule (TRAM), Toll-interleukin-1 receptor-domain-containing adaptor-inducing IFN-beta (TRIF), IL-1β, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, and interferon (INF)-γ mRNA was examined in SGs and cultured salivary epithelial cells. The mouse-specific primer sets used in the analyses are listed in Table 3. As an internal standard, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (gapdh) mRNA was measured.

Table 3.

Sequences of primers used for quantitative PCR analysis.

| gene | forward | reverse |

|---|---|---|

| tlr-2 | 5′-TTTTCATCCGATGCCCGACA-3′ | 5′-CAGCAACACAGGGAACAACG -3′ |

| tlr-3 | 5′-ATATGCGCTTCAATCCGTTC-3′ | 5′-CAGGAGCATACTGGTGCTGA-3′ |

| tlr-4 | 5′-GCTTTCACCTCTGCCTTCAC -3′ | 5′-GAAACTGCCATGTTTGAGCA-3′ |

| tlr-7 | 5′-AGCAGGACCATGGAAAGTGA-3′ | 5′-TAGATTTGGCGGCATACCCT-3′ |

| tlr-8 | 5′-TTTGCCTCAGAGCCTCCAAG-3′ | 5′-AGAGGAAGCCAGAGGGTAGG-3′ |

| tlr-9 | 5′-TTTCAGAACCTAACCCGCCT-3′ | 5′-GCCATCTGAGCGTGTACTTG-3′ |

| collagen-1 | 5′-GCGAGTGCTGTGCTTTCTG-3′ | 5′-AGGACATCTGGGAAGCAAA-3′ |

| elastin | 5′-AGCCCTAACCAGAAACTCCC-3′ | 5′-CCCCACAAAGAAGAAGCACC-3′ |

| rage | 5′-ACCCTGAGACGGGACTCTTT-3′ | 5′-ACCCTGAGACGGGACTCTTT -3′ |

| nf-kb | 5′-GCAGGCTATTGCTCATCACA -3′ | 5′-CTGACCTGAGCCTTCTGGAC-3′ |

| my-d88 | 5′-TCGAGTTTGTGCAGGAGATG-3′ | 5′-AGGCTGAGTGCAAACTTGGT-3′ |

| il-1β | 5′-GCTGAAAGCTCTCCACCTCA-3′ | 5′-AGGCCACAGGTATTTTGTCG-3′ |

| il-6 | 5′-CCACTCCCAACAGACCTGTC-3′ | 5′-GCAAGTGCATCATCGTTGTTC-3′ |

| tnf-α | 5′-CCACCACGCTCTTCTGTCTA-3′ | 5′-AGGGTCTGGGCCATAGAACT-3′ |

| inf-γ | 5′-ACTGGCAAAAGGATGGTGAC-3′ | 5′-TGAGCTCATTGAATGCTTGG-3′ |

| gapdh | 5′-TGTGTCCGTCGTGGATCTGA-3′ | 5′-TTGCTGTTGAAGTCGCAGGAG-3′ |

2.8. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

The concentration of HMGB1 in SG tissue and saliva was measured before IR and at 4, 8, and 12 weeks post-IR (n ≥ 3 at each time point) using an ELISA kit according to the manufacturer's protocol (Shino-Test Corp., Tokyo, Japan). Culture supernatant was also collected at 1, 3, 5, and 7 days post-IR to evaluate the concentration of HMGB1. Additionally, the culture supernatant was collected every 3 days post-IR for ELISA determination of the accumulation of HMGB1, p16ink4a (Bioassay Technology Laboratory, Shanghai, China), Peroxiredoxin-6 (PRDX6) (Reddot Biotech Inc., Kelowna, Canada), and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) (Proteintech) for each period, in accordance with manufacturers' protocols (n = 3 at each period).

2.9. Western blot analysis

SG tissues were homogenized in 1000 μL of RIPA buffer (Wako) containing protease inhibitors (Nacalai Tesque Inc., Kyoto, Japan). To separate proteins, SG cell lysates were centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 20 min at 4 °C. Protein concentration was determined using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific Life Sciences). Proteins were separated using 10 % sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and then transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes. The membranes were blocked with 5 % skim milk for 30 min at room temperature and then incubated overnight with the following primary antibodies: mouse anti-mouse p–NF–kB (1:1000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and mouse anti-TRAM (1:1000; Abcam). Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:2000; Cell Signaling Technology) was used as the secondary antibody. Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; 1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology) was used as a normalization marker for all samples. Images of blots were obtained using a UVP Chem Studio system (Analytik Jena, CA, USA) and normalized to GAPDH using NIH ImageJ software.

2.10. Culture of SG epithelial cells

Excised submandibular glands were cut into pieces of approximately 1 mm in diameter using a scalpel, and cells were isolated by enzymatic treatment with 1 mg/mL collagenase (Wako, Osaka, Japan) for 30 min. The cells were then filtered through a 70-μm cell strainer (BD Bioscience), and viable cells were identified by trypan blue staining and counted. For suspension and floating culture, isolated cells were seeded in wells of a 6-well, ultra-low-attachment-surface plate (Corning, NY, USA) at a density of 2 × 105 cells/2 mL of medium per well and cultured for 7 days in serum-free Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM)/F12 medium (GIBCO, NY, USA) supplemented with 15 mM HEPES (GIBCO), 1 % fungizone amphotericin B (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA), penicillin/streptomycin (Wako, Tokyo, Japan), B27 supplement (GIBCO), 10 ng/mL epidermal growth factor (EGF) (Wako), and 20 ng/mL basic fibroblast growth factor (b-FGF) (Wako). Formed aggregates were then transferred to the wells of an attachment surface plate (Nunc™ Cell-Culture Treated Multidishes; Thermo Fisher Scientific Life Sciences) and cultured in a 5 % CO2 incubator, with changing of the medium twice per week. The culture supernatant was used in place of culture medium to assess the effect on cultured SG epithelial cells in some groups using an HMGB1-neutralizing antibody (chicken anti-HMGB1 polyclonal antibody; Shino-Test Corp.). Post-IR supernatants were collected from cultures of SG epithelial cells 6 days after IR and added to normal SG epithelial cell cultures. Supernatants collected from cultures of non-irradiated SG epithelial cells were examined as controls.

2.11. Characterization of cultured SG epithelial cells

Immunocytochemistry analysis was performed as previously reported [11]. Cultured SG epithelial cells were incubated with the following primary antibodies: fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) anti-mouse CD326 (epithelial cell adhesion molecule: Ep-CAM) (1:100; Biolegend, CA, USA), rabbit anti-mouse HMGB1 (1:100; abcam), rabbit anti-mouse TLR4 (1:100; abcam), and mouse anti-mouse p–NF–κB (1:50; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Alexa Fluor 546–conjugated goat anti-rabbit (1:200; Thermo Fisher Scientific Life Sciences) was used as the secondary antibody for HMGB1, TLR2, and TLR4, and Alexa Fluor 546–conjugated mouse anti-rabbit (1:200; Thermo Fisher Scientific Life Sciences) was used as the secondary antibody for p–NF–κB.

2.12. Statistical analysis

Differences between means were analyzed using the Student's t-test for paired data and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey's post hoc multiple comparisons test for multiple groups. Experimental values are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and p < 0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference. P values were provided when a significant difference was statistically observed.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of mouse E-MNCs

Flow cytometry analysis revealed the emergence of an M2 macrophage–enriched fraction (CD11b+/CD206+) in E-MNCs (from 1.27 % of PB-MNCs to 6.10 % of E-MNCs) after 5 days of culture (Fig. 1B). CD11b-positive cells among E-MNCs appeared to comprise an enriched cellular fraction of highly phagocytic macrophages that were induced to M2 polarization (CCR2−/galectin 3+; from 1.48 % of PB-MNCs to 57.9 % of E-MNCs) (Fig. 1B).

3.2. Transplantation of E-MNCs into a mouse model of radiogenic atrophic SGs

In our previous study, we found the M2 macrophages among E-MNCs internalized extracellular HMGB1 in irradiated SGs via phagocytosis, and the concentration of HMGB1 subsequently decreased after E-MNC transplantation [11] (Fig. 2A). In the present study, changes in HMGB1-related signaling pathways were examined by monitoring the expression of TLR4 and RAGE in E-MNC–transplanted SGs. E-MNC administration led to the down-regulation of TLR4 mRNA expression in SGs at 4 weeks post-IR (Fig. 2B). Histological observations at the same timepoint revealed distinct TLR4 expression in irradiated SGs without E-MNC transplantation but suppression of TLR4 expression in E-MNC–transplanted SGs (Fig. 2C). Slight RAGE expression was detected in irradiated SGs without E-MNC transplantation, but RAGE expression was almost undetectable after E-MNC transplantation (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

Analysis of the therapeutic mechanism of E-MNC transplantation in mouse SGs. (A) Diagram of cellular mechanism of E-MNC treatment. M2 macrophages among E-MNCs might contribute to the conversion of damaged tissues from a pro-inflammatory to anti-inflammatory state by mediating HMGB1 clearance. (B) Relative mRNA expression of the TLR4 gene in SGs at 4 weeks post-IR. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. (C) TLR4 expression (red, TLR4; blue, DAPI; scale bar, 100 μm) ( × 200) at 4 weeks post-IR. (D) RAGE expression (red, RAGE; blue, DAPI; scale bar, 100 μm) ( × 200) at 4 weeks post-IR.

3.3. Pathologic changes in submandibular glands after IR

Saliva secretion in mice gradually decreased over time post-IR (at 2 weeks post-IR, ∗p < 0.05; at weeks 4, 8, and 12 weeks post-IR, ∗∗∗p < 0.001) (Fig. 3A). At 12 weeks post-IR, progression of pathologic changes in irradiated SGs was evident, with vanishing and vacuolar degeneration observed in the acinar cell area (Fig. 3B). SA-β-Gal staining of SG samples showed almost no cellular senescence at 20 weeks in normal mice but marked senescence at 48 weeks, reflecting aging. However, following IR, marked cellular senescence appeared at 20 weeks (Fig. 3C). Furthermore, clear signs of tissue atrophy and fibrosis were observed in SGs at 12 weeks post-IR (Fig. 3D). Consistent with these histological observations, the expression of mRNAs of fibrosis-associated genes (e.g., collagen-1 and elastin) was significantly up-regulated in SGs at 12 weeks post-IR (collagen-1, ∗∗p < 0.01; elastin, ∗∗∗p < 0.001) (Fig. 3E and F). Concomitant with these tissue damages due to radiation exposure, the concentration of extracellular HMGB1 significantly increased over time in both SG tissue and saliva (Fig. 3G and H).

Fig. 3.

Post-IR functional and pathologic changes in SGs. (A) Change in salivary flow rate (SFR) at 0, 2, 4, 8, and 12 weeks post-IR. (B) Hematoxylin and eosin staining (scale bar, 100 μm) ( × 200). (C) SA-β-Gal staining of SGs of 20- and 48-week-old mice (IR-20w; 20-week-old mice at 8 weeks post-IR) compared with non-irradiated mice (Ctrl) (scale bar, 100 μm) ( × 200). (D) Masson's trichrome staining (scale bar, 200 μm) ( × 100). Fibrotic areas are stained blue. (E, F) Relative expression of collagen-1 and elastin mRNAs in SGs of mice at 12 weeks post-IR (IR-12w) compared with non-irradiated mice (Ctrl) (∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001). (G, H) Concentration of extracellular HMGB1 in SG tissues and saliva at 0, 2, 4, 8, and 12 weeks post-IR (∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001). Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation.

3.4. Expression of genes related to pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs) for HMGB1 from 4 to 12 weeks post-IR

With regard to receptor expression in HMGB1 signaling, TLR2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 9, and RAGE were up-regulated at 12 weeks post-IR (TLR2, 3, 4, and RAGE, ∗∗∗p < 0.001; TLR7 and TLR8, ∗∗p < 0.01; TLR9, ∗p < 0.05) (Fig. 4A–G). Among these HMGB1 receptors, the up-regulation of TLR4 expression at 12 weeks post-IR (approximately 2.69-fold increase) was particularly prominent (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

Expression of genes related to PRRs for HMGB1. (A–G) Relative expression of HMGB1 receptor mRNAs (TLR2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 9, and RAGE) in SGs from 4 to 12 weeks post-IR compared with non-irradiated mice (∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001). Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation.

3.5. Histological observations of TLR4 and RAGE at 12 weeks post-IR

Histological observations showed marked TLR4 expression in SGs at 12 weeks post-IR (Fig. 5A). Interestingly, TLR4 expression co-localized with cells positive for KRT14 (a marker of ductal cells) but not AQP5 (a marker of acinar cells) (Fig. 5B and C). Furthermore, notable RAGE expression was also observed at 12 weeks post-IR (Fig. 5D), and RAGE was co-expressed by cells positive for expression of CD31 (a marker of blood vessels) and F4/80 (a marker of macrophages) (Fig. 5E and F). Protein expression of TLR2, an HMGB1 receptor similar to TLR4, was barely detectable in SGs after IR (Supplemental Fig. 1), even though expression of TLR2 mRNA was elevated (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 5.

Histological observations of TLR4 and RAGE expression in SGs at 12 weeks post-IR. (A) Expression of TLR4 (red, TLR4; blue, DAPI; scale bar, 100 μm) ( × 200). (B) Expression of TLR4 and AQP5 (red, TLR4; green, AQP5; blue, DAPI; scale bar, 100 μm) (upper, × 200; lower, × 400). (C) Expression of TLR4 and KRT14 (red, TLR4; green, KRT14; blue, DAPI; scale bar, 100 μm) (upper, × 200; lower, × 400). (D) Expression of RAGE (red, RAGE; blue, DAPI; scale bar, 100 μm) (upper, × 200; lower, × 400). (E) Expression of RAGE and CD31 (red, CD31; green, RAGE; blue, DAPI; scale bar, 20 μm) ( × 1000). (F) Expression of RAGE and F4/80 (red, RAGE; green, F4/80; blue, DAPI; scale bar, 20 μm) ( × 1000).

3.6. Molecular signaling of the TLR4/RAGE/NF-κB axis contributes to post-IR inflammatory cytokine production

To assess the expression level of p–NF–κB in SG tissues post-IR, Western blotting and immunohistochemical staining were performed. The expression of p–NF–κB protein in SGs was increased at 1 week post-IR (Fig. 6A), and notable expression in the nuclear fraction was observed in the ductal portion at 4 weeks post-IR (Fig. 6B and C). Expression of the genes encoding NF-κB and its adaptor molecules, including myeloid differentiation factor 8 (MyD88), TRIF-related adaptor molecule (TRAM), and Toll-interleukin-1 receptor domain-containing adaptor inducing IFN-beta (TRIF), was significantly up-regulated by 12 weeks post-IR (∗∗∗p < 0.001) (Fig. 6D, E, 6F), suggesting that the TLR4/RAGE/NF-κB signaling pathway was activated. Indeed, the expression of genes encoding various pro-inflammatory cytokines in SGs, including IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and Interferon-γ (INF-γ), was up-regulated at 8 weeks post-IR (∗∗∗p < 0.001). The expression of IL-1β and INF-γ mRNAs was already elevated at 4 weeks post-IR (IL-1β, ∗∗∗p < 0.001; INF-γ, ∗∗p < 0.01) (Fig. 6G).

Fig. 6.

Analysis of NF-κB pathway activity in SGs post-IR. (A) Protein expression of p–NF–κB (p65) in SGs of non-irradiated mice (Ctrl) and irradiated mice (IR) at 1 week post-IR. (B, C) p–NF–κB expression at 4 weeks post-IR compared with non-irradiated mice (Ctrl) (red, p–NF–κB; blue, DAPI; scale bar, 100 μm) ( × 200). (D) NF-κB gene expression in SGs from 4 to 12 weeks post-IR compared with non-irradiated mice (∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001). (E) MyD88 gene expression in SGs from 4 to 12 weeks post-IR compared with non-irradiated mice (∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001). (F) Relative expression of TRAM and TRIF mRNAs post-IR compared with non-irradiated mice (∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001). (G) Relative expression of IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and INF-γ mRNAs (∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001). Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation.

3.7. Pathologic changes in cultured SG epithelial cells post-IR

To obtain better induction of SG epithelial cells, excluding non-epithelial cells as much as possible, isolated cells from SGs tissues were first maintained in floating aggregation culture. After 7 days of floating culture, these isolated cells formed aggregates, which then formed colonies after transfer to adherent culture plates (Fig. 7A and B). The colonies consisted primarily of CD326 (Ep-CAM)-positive cells (approximately 92.1 %) (Fig. 7C and D). Immunocytostaining of HMGB1 to investigate the effect of radiation exposure on cultured SG epithelial cells showed that HMGB1 leaked from the nucleus and was scattered within the cytoplasm in a few cultured cells at 3 days post-IR, and by 5 days post-IR, most of the HMGB1 was extracellular (Fig. 7E). Consistent with this observation, the concentration of HMGB1 in the culture supernatant of SG epithelial cells increased over time post-IR (1 day, 1.95-fold; 3 days, 3.62-fold; 5 days, 4.58-fold; 7 days, 5.09-fold) (Fig. 7F). After addition of HMGB1-containing supernatant from 7 days post-IR to cultured SG epithelial cells, marked TLR4 expression was detected in Ep-CAM–positive cells after 3 and 7 days of culture (Fig. 7G).

Fig. 7.

Cultivation of SG epithelial cells and cellular changes in cultured SG cells post-IR. (A) Schematic diagram of the cultivation of SG epithelial cells and phase-contrast imaging (scale bar, 100 μm) ( × 400). (B) Phase-contrast image of cultured SG epithelial cells at 14 days after transfer to coating plate (scale bar, 50 μm) ( × 400). (C) Ep-CAM expression in cultured SG epithelial cells at 14 days after transfer to coating plate (green, Ep-CAM; blue, DAPI; scale bar, 50 μm) ( × 400). (D) Flow cytometry analysis of cultured SG epithelial cells. Percentages of Ep-CAM–positive cells among living cells are shown. (E) Immunocytochemistry analysis of HMGB1 in cultured SG epithelial cells post-IR (red, HMGB1; blue, DAPI; scale bar, 100 μm) ( × 200). (F) Change in concentration of HMGB1 in supernatant of cultured SG epithelial cells post-IR (∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001). (G) Change in TLR4 expression in Ep-CAM–positive SG epithelial cells cultured in collected supernatant (red, TLR4; green, Ep-CAM; blue, DAPI; scale bar, 100 μm) ( × 400).

3.8. Pathologic changes in SG epithelial cells cultured with post-IR supernatant

Phase-contrast images showed that after 7 days of culture in post-IR supernatant, many cultured SG epithelial cells had detached from the dish and were floating (Fig. 8A). Additionally, SA-β-Gal assay indicated that culture in post-IR supernatant induced senescence of SG epithelial cells within 3 days (Fig. 8B). To assess the accumulation of DAMPs and senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) factors, including HMGB1, p16ink4a, PRDX6, and TNF-α, their concentrations in the supernatant after cultivation in post-IR supernatant were analyzed after 3, 6, 9, and 12 days of culture. The results showed that overall, these proteins accumulated in significant amounts when cells were cultured in post-IR supernatant. The concentration of HMGB1 was particularly high in the supernatant after cells were cultured in post-IR supernatant (Fig. 8C).

Fig. 8.

Pathologic changes in SG epithelial cells cultured in collected supernatant. (A) Phase-contrast image of SG epithelial cells cultured in the supernatant at 7 days (scale bar, 400 μm) ( × 100). (B) SA-β-Gal assay of SG epithelial cells cultured in supernatant; cells were assayed at 3-day intervals post-IR (scale bar, 100 μm) ( × 200). (C) Concentrations of HMGB1, p16ink4a, PRDX6, and TNF-α in supernatants collected at 3-day intervals post-IR (∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001). (D) Expression of TLR genes in SG epithelial cells cultured in supernatant with/without HMGB1-neutralizing antibody at 7 days (Ctrl, cultured with supernatant [Ctrl]; Supernatant, cultured with supernatant [IR]; Anti, cultured with supernatant [IR] and HMGB1-neutralizing antibody) (∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001). (E) Expression of NF-κB, MyD88, and inflammation-related cytokine genes in SG epithelial cells cultured in supernatant with/without HMGB1-neutralizing antibody at 7 days (Ctrl, cultured with supernatant [Ctrl]; Supernatant, cultured with supernatant [IR]; Anti, cultured with supernatant [IR] and HMGB1-neutralizing antibody) (∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001). Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. (F) p–NF–κB expression in SG epithelial cells cultured in supernatant (IR) at 1 day (red, p–NF–κB; blue, DAPI; scale bar, 100 μm) ( × 400). (G) Protein expression of TRAM in SG epithelial cells cultured in supernatant (IR) at 7 days.

Analysis of gene expression in SG epithelial cells cultured under the abovementioned conditions for 7 days revealed that TLR4 mRNA expression was significantly increased compared with that of cells not exposed to post-IR supernatant (TLR4, ∗∗∗p < 0.001). Similar increases in the expression of TLR3 and TRL7 mRNAs were detected in cells exposed to post-IR supernatant (TLR3, ∗∗p < 0.01; TLR7, ∗p < 0.05), whereas no obvious changes were seen in the mRNA expression of TLR2 and TLR9 (Fig. 8D).

Concomitant with increased TLR expression, especially TLR4 in SG epithelial cells exposed to post-IR supernatant, the NF-κB and MyD88 genes were also up-regulated (NF-κB, ∗p < 0.05; MyD88, ∗∗∗p < 0.001), and mRNA expression of their downstream pro-inflammatory cytokines was also significantly up-regulated (IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and INF-γ, ∗∗∗p < 0.001) (Fig. 8E). Interestingly, when HMGB1-neutralizing antibody was added to the post-IR supernatant, down-regulation of TLR4 gene expression was observed in cultured cells (∗∗p < 0.01), followed by down-regulation of the mRNA expression of NF-κB, MyD88, and their downstream cytokines, including IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and INF-γ (NF-kB, ∗p < 0.05; MyD88, ∗∗p < 0.01; IL-1β, ∗∗∗p < 0.001; IL-6, TNF-α, ∗∗p < 0.01; INF-γ, ∗p < 0.05) (Fig. 8D and E). Further analysis of protein expression in SG epithelial cells exposed to post-IR supernatant showed increased nuclear translocation of p–NF–κB for 1 day of culture, and then the expression of TRAM, a specific adaptor protein in the TLR4/NF-κB pathway, increased for 7 days (Fig. 8F and G).

3.9. Pathologic changes in TLR4-KO mice at 4 and 8 weeks post-IR

TLR4-KO mice were employed to verify the significance of TLR4 signaling in the progression of radiation injury in SGs. At 4 and 8 weeks post-IR, TLR4-KO mice showed milder functional impairment but no significant changes in saliva secretion, whereas wild-type mice showed an obvious decrease in saliva secretion (∗∗p < 0.01) (Fig. 9A). However, the HMGB1 concentration in damaged SGs of both wild-type and TLR4-KO mice increased over time up to 8 weeks post-IR (∗∗∗p < 0.001) (Fig. 9B). In the absence of increased TLR4 expression, expression of the TLR2 and RAGE genes increased in TLR4-KO mice over time, similar to wild-type mice (∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001) (Fig. 9C, D, 9E). Interestingly, analysis of the mRNA expression of the TLR4 downstream signaling molecules NF-κB and MyD88 revealed that NF-κB expression was significantly up-regulated in wild-type mice at 8 weeks pos-IR (∗∗∗p < 0.001), whereas no obvious changes in NF-κB or MyD88 expression were observed in SGs of TLR4-KO mice (Fig. 9F and G). However, mRNA expression of downstream pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-β, IL-6, TNF-α, and INF-γ, increased over time up to 8 weeks post-IR, although down-regulation of NF-κB expression consequently suppressed the expression of these cytokines compared with wild-type mice, except for TNF-α (∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001) (Fig. 9H). These findings suggest that in TLR4-KO mice, both TLR2 and RAGE signaling are activated on behalf of TLR4. Indeed, when SG epithelial cells from TLR4-KO mice were cultured in post-IR supernatant for 1 day, p–NF–κB nuclear translocation was diminished compared with wild-type mice (Fig. 9I). Additionally, the number of RAGE-positive macrophages and blood vessel cells in SGs of TLR4-KO mice increased steadily post-IR until reaching a level similar to that of wild-type mice (∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001) (Fig. 9J).

Fig. 9.

Analysis of functional and pathologic changes in SGs of TLR4-KO mice at 4 and 8 weeks post-IR. (A) Saliva production (salivary flow rate; SFR) in non-irradiated wild-type (WT) mice (Ctrl), irradiated WT mice (WT), and irradiated TLR4-KO mice (KO) (∗∗p < 0.01). (B) Concentration of HMGB1 in SGs (∗∗∗p < 0.001). (C) Relative expression of TLR2 mRNA post-IR compared with non-irradiated WT mice (∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001). (D) Relative expression of TLR4 mRNA post-IR compared with non-irradiated WT mice (∗∗∗p < 0.001). (E) Relative expression of RAGE mRNA post-IR compared with non-irradiated WT mice (∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001). (F) Relative expression of NF-κB mRNA post-IR compared with non-irradiated WT mice (∗∗∗p < 0.001). (G) Relative expression of MyD88 mRNA post-IR compared with non-irradiated WT mice (∗p < 0.05). (H) Relative expression of IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and INF-γ mRNAs post-IR compared with non-irradiated WT mice (∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001). (I) p–NF–κB expression in SG epithelial cells derived from WT or KO mice cultured in supernatant (IR) at 7 days (red, p–NF–κB; blue, DAPI; scale bar, 100 μm) ( × 200). (J) Number of RAGE-positive cells in SGs post-IR compared with non-irradiated WT mice (∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001). Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation.

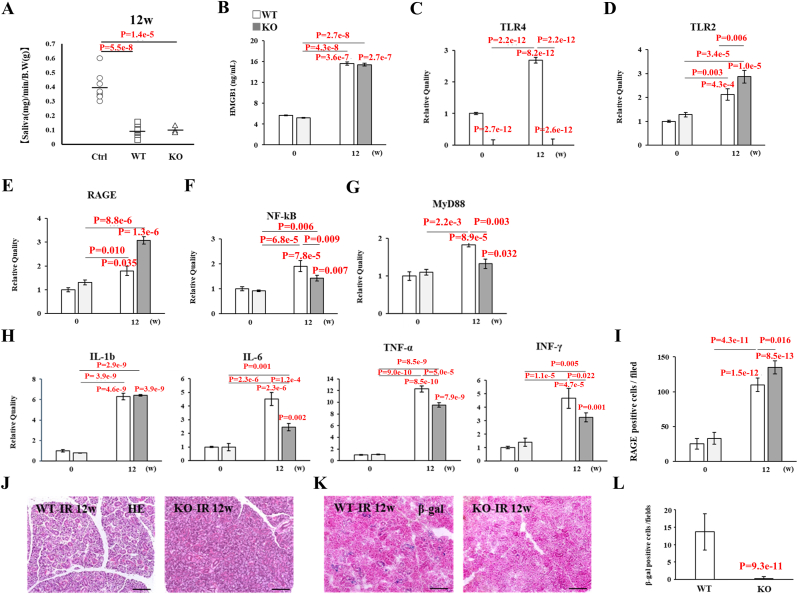

3.10. Pathologic changes in TLR4-KO mice at 12 weeks post-IR

Despite showing milder functional impairment and maintenance of saliva volume production up to 8 weeks post-IR, TLR4-KO mice showed severe saliva secretory dysfunction compared with wild-type mice at 12 weeks post-IR (∗∗p < 0.01) (Fig. 10A). The HMGB1 concentration in damaged SGs of both wild-type and TLR4-KO mice was significantly increased (approximately 3-fold) at 12 weeks post-IR (∗∗∗p < 0.001) (Fig. 10B). Higher expression of the TLR2 and RAGE genes was observed in TLR4-KO mice, in which expression of TLR4 mRNA is lacking compared with wild-type mice (∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001) (Fig. 10C, D, 10E). Expression of NF-κB and MyD88 mRNAs was increased in both wild-type and TLR4-KO mice, but their expression levels in TLR4-KO mice were relatively low compared with wild-type mice (∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001) (Fig. 10F and G). Overall, the expression of NF-κB downstream pro-inflammatory genes (IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and INF-γ) was up-regulated in TLR4-KO mice, but the expression levels of IL-6, TNF-α, and INF-γ mRNAs were low compared with wild-type mice (∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001) (Fig. 10H). These data also appear to support alternative activation of both TLR2 and RAGE signaling to TLR4 in KO mice, because a number of RAGE-positive cells were observed in SGs of both TLR4-KO and wild-type mice at 12 weeks post-IR, and the number was significantly higher in TLR4-KO mice than wild-type mice (∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001) (Fig. 10I). By contrast, histological observations revealed diminishment of the acinar cell area and vacuolar degeneration in SGs of wild-type mice, whereas these pathologic changes were notably absent in TLR4-KO mice (Fig. 10J). Additionally, SA-β-Gal staining revealed very low levels of cellular senescence in SGs of TLR4-KO mice compared with wild-type mice (Fig. 10K, L).

Fig. 10.

Analysis of functional and pathologic changes in SGs of TLR4-KO mice at 12 weeks post-IR. (A) Saliva production (salivary flow rate; SFR) in non-irradiated wild-type (WT) mice (Ctrl), irradiated WT mice (WT), and irradiated TLR4-KO mice (KO) (∗∗p < 0.01). (B) Concentration of HMGB1 in SGs (∗∗∗p < 0.001). (C) Relative expression of TLR4 mRNA post-IR compared with non-irradiated WT mice (∗∗∗p < 0.001). (D) Relative expression of TLR2 mRNA post-IR compared with non-irradiated WT mice (∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001). (E) Relative expression of RAGE mRNA post-IR compared with non-irradiated WT mice (∗∗∗p < 0.001). (F) Relative expression of NF-κB mRNA post-IR compared with non-irradiated WT mice (∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001). (G) Relative expression of MyD88 mRNA post-IR compared with non-irradiated WT mice (∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001). (H) Relative expression of IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and INF-γ mRNAs post-IR compared with non-irradiated WT mice (∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001). (I) Number of RAGE-positive cells in SGs post-IR compared with non-irradiated WT mice (∗p < 0.05, ∗∗∗p < 0.001). (J) Hematoxylin and eosin staining of SGs of 20-week-old mice (IR 20w; 20-week-old mice at 8 weeks post-IR) (scale bar, 100 μm) ( × 200). (K) SA-β-Gal staining of SGs of 20-week-old mice (IR 20w; 20-week-old mice at 8 weeks post-IR) (scale bar, 100 μm) ( × 200). (L) Number of SA-β-Gal–positive cells in SGs of 20-week-old mice. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation.

4. Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that HMGB1/RAGE/TLR4 signaling contributes to the progression of SG hypofunction after radiation therapy and thus could be a potential target for E-MNC therapy. The positive outcomes of this study were as follows: (1) after exposure of SGs to radiation, extracellular HMGB1 accumulates in SG tissue, and expression of RAGE in blood vessels and macrophages, and of TLR4 in ductal cells increases over time; expression of pro-inflammatory cytokine genes is upregulated in damaged SG tissues via the NF-κB pathway; (2) culture supernatant containing extracellular HMGB1, derived from SG cells damaged by IR, induces TLR4 expression in cultured SG epithelial cells, leading to the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines; (3) the onset of radiogenic SG hypofunction is substantially delayed in TLR4-KO mice, but RAGE-positive cells alternatively emerge; (4) E-MNCs appear to act as a trigger that induces formation of an anti-inflammatory and tissue-regenerative environment in response to radiogenic SG hypofunction via phagocytic elimination of extracellular HMGB1 and inhibition of the TLR4/RAGE pathway.

Regarding the characteristics of E-MNCs, an M2 macrophage–enriched fraction (CD11b+/CD206+) was induced by 5G-culture (from 1.27 % in PB-MNCs to 6.10 % in E-MNCs). Macrophages are generally categorized as either inflammatory M1 macrophages or anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages. M1 macrophages produce high levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNFα, IL-6, and IL-1β, whereas CD206-positive M2 macrophages generate high levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10 [26,27]. The notable increase in galectin 3+/CCR2− cells (from 1.48 % in PB-MNCs to 57.9 % in E-MNCs) among CD11b-positive cells suggests an increase in the population of cells exhibiting phagocytic and immunomodulatory capabilities. In macrophages, galectin 3 plays a role in the resolution of inflammation-related pathology via phagocytic clearance [[28], [29], [30]]. CCR2-positive macrophages migrate toward the CCR2 ligand, CC-chemokine ligand 2, and recruit other monocytes to inflammatory lesions. Therefore, CCR2-positive macrophages are known as the pro-inflammatory subset (M0/M1 macrophages). By contrast, macrophages exhibiting anti-inflammatory functions (M2 macrophages) are identified by a CCR2− phenotype in mice [[31], [32], [33], [34]]. Indeed, our previous studies showed that IL-10 mRNA expression is up-regulated in E-MNCs, whereas the expression of Th1-associated genes (e.g., IFN-γ and IL-1) is down-regulated. Additionally, M2-macrophages among transplanted E-MNCs internalize extracellular HMGB1, resulting in lower post-IR concentrations of HMGB1 in SG tissues [11]. In association with a decrease in HMGB1 concentration following E-MNC transplantation, the present study found that the expression of TLR4 and RAGE, which function as PRRs for HMGB1, was suppressed, and this suppression was more notable for TLR4.

With regard to the progression of pathologic changes in SG tissue after IR, a single dose of 12 Gy of gamma radiation caused irreversible degeneration, including cellular senescence, fibrosis, and significant atrophy of the SGs, with decreasing saliva secretion over time. In accordance with these observations, several reports have indicated that radiation exposure induces the DNA damage response, apoptosis, cellular senescence, and fibrosis, resulting in tissue atrophy [[35], [36], [37], [38]]. Furthermore, higher concentrations of extracellular HMGB1 were observed in SG tissues and saliva. Despite continuous secretion of HMGB1 into the saliva, HMGB1 accumulated, which could suggest a disruption of SG homeostasis. HMGB1 is a non-histone chromatin protein located in the cell nucleus that plays a variety of key roles, such as in stabilizing the chromatin structure and gene transcription [39,40]. By contrast, extracellular HMGB1 released by necrotic cells binds to PRRs and functions as a DAMP molecule. Structurally, HMGB1 is composed of three domains (A box, B box, and an acidic C-terminal tail), which contain regions that bind to TLR2/4 and RAGE. These PRRs recognize alarm signals and activate innate immune responses against infection and injury [[40], [41], [42]]. Our analyses revealed that the gene expression levels of representative PRRs in SGs increased markedly over time post-IR, and this up-regulation was particularly prominent for TLR2/4 and RAGE. Up-regulated expression of other PRRs may be substantially due to other DAMPs and SASP factors. Interestingly, enhanced TLR4 expression post-IR was localized to surviving ductal cells. TLR4 is expressed not only on immune cells such as dendritic cells (DCs), macrophages, T cells, and B cells but also on non-immune cells such as fibroblasts and epithelial cells. Previous studies have demonstrated that accumulation of extracellular HMGB1 in epithelial cells plays a role in the pathogenesis of several inflammatory diseases, such as asthma, diabetes mellitus, ulcerative colitis, and SS [[43], [44], [45], [46]]. For instance, expressions of TLR4 on ductal cells of the minor SGs of patients with SS were shown to increase with increasing disease severity, and release of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-17 and IL-23 by ductal epithelial cells has been reported [46]. As far as we are aware, this is the first study to reveal that MyD88-dependent and -independent (TRIF-dependent) NF-κB signaling mediates sterile inflammation in radiation-induced SG dysfunction. The TLR and RAGE signaling pathways in vessels and macrophages also contribute to the progression of chronic inflammation.

Based on our results, it is reasonable to assume that various factors (e.g., DAMPs and SASP) and their receptors are involved in the pathogenesis of radiation-induced SG atrophy via a complex mechanism. This hypothesis is supported by our results indicating that several DAMPs and SASP factors released from cultured SG epithelial cells post-IR induce cellular senescence/necrosis of healthy SG epithelial cells in vitro. However, it should be noted that an anti-HMGB1 antibody suppressed the expression of various PRRs, leading to significant inhibition of the expression of MyD88/NF-κB pathway and pro-inflammatory cytokine genes, despite the continued effects of other DAMPs and SASP factors. Considering the effect of the anti-HMGB1 antibody, among the many DAMPs and SASP factors, HMGB1 clearly contributes significantly to the pathogenesis of radiogenic salivary hypofunction.

To better understand the involvement of TLR4-positive cells in the pathogenesis of radiation damage in SGs, this study explored the roles of other PRRs in the context of radiogenic salivary hypofunction in TLR4-KO mice. Our initial hypothesis was that IR-induced SG hypofunction would be suppressed in TLR4-KO mice due to TLR4 deficiency. However, we found that the onset of salivary hypofunction was merely delayed in TLR4-KO mice and that alternatively, the number of RAGE-positive cells increased. Consequently, SG hypofunction also developed post-IR in TLR4-KO mice. These results indicate that the use of specific antibodies and receptor-blocking agents provides limited therapeutic efficacy because several released factors, such as DAMPs/SASP factors and their PRRs, interact via a complex mechanism to mediate the progression of pathologic changes in SG tissue after IR. Care should be exercised in the use of PRR inhibitors in particular due to the risk of suppressing innate immunity. Therefore, eliminating DAMPs/SASP factors is important for the resolution of sterile inflammation. In this regard, cell therapies using phagocytic cells such as macrophages, which comprehensively eliminate DAMPs/SASP factors, appear to hold promise as therapeutic approaches. Indeed, Msr1/macrophage receptor with collagenous structure (Marco) (type A scavenger)-positive macrophages reportedly help resolve excessive inflammation after ischemic stroke by promoting the clearance of DAMPs such as peroxiredoxin and HMGB1 [19].

5. Conclusions

To our knowledge, it is the first report to reveal that HMGB1/RAGE/TLR4 signaling contributes to the progression of SG hypofunction after radiation therapy. Therefore, HMGB1/RAGE/TLR4 signaling pathway could be a potential target, and E-MNCs contributed to the removal of HMGB1 and the resolution of excessive inflammation. These findings may impact on the development of future cell-based regenerative therapy utilization immunomodulatory and/or phagocytic cells.

Funding

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI grant numbers 23K24534 and 23K27793.

Declaration of competing interest

Author MS is the CEO of CellAxia Inc.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

- E-MNCs

effective-mononuclear cells

- SG

salivary glands

- SS

Sjögren syndrome

- Th2

T helper 2 lymphocytes

- IL-6

Interleukin-6

- HMGB1

high mobility group box 1

- DAMPs

damaged associated molecular patterns

- IGF1

insulin-like growth factor 1

- TLR5

toll-like receptor 5

- Msr1

Macrophage scavenger receptor 1

- PI

propidium iodide

- PFA

paraformaldehyde

- H&E

hematoxylin and eosin

- SA-beta-gal

Senescence-associated beta-galactosidase

- AQP5

Aquaporin-5

- KRT14

Cytokeratin-14

- DAPI

4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- ip

intraperitoneal

- IR

irradiation

- SFR

salivary flow rate

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- gapdh

glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- ELISA

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

- PRDX6

Peroxiredoxin-6

- BCA

bicinchoninic acid

- PVDF

polyvinylidene fluoride

- SDS-PAGE

sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- HRP

horseradish peroxidase

- DMEM

Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium

- EGF

epidermal growth factor

- b-FGF

basic fibroblast growth factor

- FITC

fluorescein isothiocyanate

- Ep-CAM

epithelial cell adhesion molecule

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- SD

standard deviation

- p–NF–kB

phospho-nuclear factor-kappa B

- MyD88

myeloid differentiation factor 88

- TRAM

TRIF-related adaptor molecule

- TRIF

Toll-interleukin-1 receptor-domain-containing adaptor-inducing IFN-beta

- SASP

senescence-associated secretory phenotype

- PRRs

pattern recognition receptors

- DCs

dendritic cells

- MARCO

macrophage receptor with collagenous structure

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of the Japanese Society for Regenerative Medicine.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reth.2025.07.004.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is/are the supplementary data to this article:

figs1.

References

- 1.Alajbeg I., Falcão D.P., Tran S.D., Martín-Granizo R., Lafaurie G.I., Matranga D., et al. Intraoral electrostimulator for xerostomia relief: a long-term, multicenter, open-label, uncontrolled, clinical trial. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2012;113(6):773–781. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2012.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baum B.J., Kok M., Tran S.D., Yamano S. The impact of gene therapy on dentistry: a revisiting after six years. J Am Dent Assoc. 2002;133(1):35–44. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2002.0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baum B.J., Tran S.D. Synergy between genetic and tissue engineering: creating an artificial salivary gland. Periodontol. 2000. 2006;41:218–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2006.00160.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kagami H. The potential use of cell-based therapies in the treatment of oral diseases. Oral Dis. 2015;21(5):545–549. doi: 10.1111/odi.12320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patel V.N., Hoffman M.P. Salivary gland development: a template for regeneration. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2014;25–26:52–60. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tran S.D., Sumita Y., Khalili S. Bone marrow-derived cells: a potential approach for the treatment of xerostomia. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2011;43(1):5–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2010.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sumita Y., Liu Y., Khalili S., Maria O.M., Xia D., Key S., et al. Bone marrow-derived cells rescue salivary gland function in mice with head and neck irradiation. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2011;43(1):80–87. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2010.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tanaka J., Ogawa M., Hojo H., Kawashima Y., Mabuchi Y., Hata K., et al. Generation of orthotopically functional salivary gland from embryonic stem cells. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):4216. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06469-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tanaka J., Mishima K. Generation of salivary gland organoids from mouse embryonic stem cells. Methods Mol Biol. 2022;2429:247–255. doi: 10.1007/978-1-0716-1979-7_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.I T., Sumita Y., Yoshida T., Honma R., Iwatake M., Raudales J.L.M., et al. Anti-inflammatory and vasculogenic conditioning of peripheral blood mononuclear cells reinforces their therapeutic potential for radiation-injured salivary glands. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2019;10(1):304. doi: 10.1186/s13287-019-1414-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Honma R., I T., Seki M., Iwatake M., Ogaeri T., Hasegawa K., et al. Immunomodulatory macrophages enable E-MNC therapy for radiation-induced salivary gland hypofunction. Cells. 2023;12(10) doi: 10.3390/cells12101417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hasegawa K., Raudales J.L.M., I T., Yoshida T., Honma R., Iwatake M., et al. Effective-mononuclear cell (E-MNC) therapy alleviates salivary gland damage by suppressing lymphocyte infiltration in Sjögren-like disease. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2023;11 doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2023.1144624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Du Q., Tsuboi N., Shi Y., Ito S., Sugiyama Y., Furuhashi K., et al. Transfusion of CD206(+) M2 macrophages ameliorates antibody-mediated glomerulonephritis in mice. Am J Pathol. 2016;186(12):3176–3188. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2016.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chu F., Shi M., Lang Y., Chao Z., Jin T., Cui L., et al. Adoptive transfer of immunomodulatory M2 macrophages suppresses experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in C57BL/6 mice via blockading NF-κB pathway. Clin Exp Immunol. 2021;204(2):199–211. doi: 10.1111/cei.13572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wen Y., Zhang S., Meng X., Zhao C., Hou B., Zhu X., et al. Water extracts of Tibetan medicine Wuweiganlu attenuates experimental arthritis via inducing macrophage polarization towards the M2 type. J Ethnopharmacol. 2024;318(Pt A) doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2023.116934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salminen A. Immunosuppressive network promotes immunosenescence associated with aging and chronic inflammatory conditions. J Mol Med (Berl) 2021;99(11):1553–1569. doi: 10.1007/s00109-021-02123-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maroso M., Balosso S., Ravizza T., Liu J., Aronica E., Iyer A.M., et al. Toll-like receptor 4 and high-mobility group box-1 are involved in ictogenesis and can be targeted to reduce seizures. Nat Med. 2010;16(4):413–419. doi: 10.1038/nm.2127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sato A., Suzuki S., Watanabe S., Shimizu T., Nakamura Y., Misaka T., et al. DPP4 inhibition ameliorates cardiac function by blocking the cleavage of HMGB1 in diabetic mice after myocardial infarction. Int Heart J. 2017;58(5):778–786. doi: 10.1536/ihj.16-547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shichita T., Ito M., Morita R., Komai K., Noguchi Y., Ooboshi H., et al. MAFB prevents excess inflammation after ischemic stroke by accelerating clearance of damage signals through MSR1. Nat Med. 2017;23(6):723–732. doi: 10.1038/nm.4312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kamiya M., Mizoguchi F., Kawahata K., Wang D., Nishibori M., Day J., et al. Targeting necroptosis in muscle fibers ameliorates inflammatory myopathies. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):166. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-27875-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ek M., Popovic K., Harris H.E., Nauclér C.S., Wahren-Herlenius M. Increased extracellular levels of the novel proinflammatory cytokine high mobility group box chromosomal protein 1 in minor salivary glands of patients with Sjögren's syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(7):2289–2294. doi: 10.1002/art.21969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou X.R., Wang X.Y., Sun Y.M., Zhang C., Liu K.J., Zhang F.Y., et al. Glycyrrhizin protects submandibular gland against radiation damage by enhancing antioxidant defense and preserving mitochondrial homeostasis. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 2024;41(10–12):723–743. doi: 10.1089/ars.2022.0183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen S., Tang W., Yu G., Tang Z., Liu E. CXCL12/CXCR4 axis is involved in the recruitment of NK cells by HMGB1 contributing to persistent airway inflammation and AHR during the late stage of RSV infection. J Microbiol. 2023;61(4):461–469. doi: 10.1007/s12275-023-00018-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liang T., Yang S.X., Qian C., Du L.D., Qian Z.M., Yung W.H., et al. HMGB1 mediates inflammation-induced DMT1 increase and dopaminergic neurodegeneration in the early stage of parkinsonism. Mol Neurobiol. 2024;61(4):2006–2020. doi: 10.1007/s12035-023-03668-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spadaro O., Camell C.D., Bosurgi L., Nguyen K.Y., Youm Y.H., Rothlin C.V., et al. IGF1 shapes macrophage activation in response to immunometabolic challenge. Cell Rep. 2017;19(2):225–234. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.03.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fujisaka S., Usui I., Ikutani M., Aminuddin A., Takikawa A., Tsuneyama K., et al. Adipose tissue hypoxia induces inflammatory M1 polarity of macrophages in an HIF-1α-dependent and HIF-1α-independent manner in obese mice. Diabetologia. 2013;56(6):1403–1412. doi: 10.1007/s00125-013-2885-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murray P.J. Macrophage polarization. Annu Rev Physiol. 2017;79:541–566. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-022516-034339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Quenum Zangbede F.O., Chauhan A., Sharma J., Mishra B.B. Galectin-3 in M2 macrophages plays a protective role in resolution of neuropathology in brain parasitic infection by regulating neutrophil turnover. J Neurosci. 2018;38(30):6737–6750. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3575-17.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsuyama J., Nakamura A., Ooboshi H., Yoshimura A., Shichita T. Pivotal role of innate myeloid cells in cerebral post-ischemic sterile inflammation. Semin Immunopathol. 2018;40(6):523–538. doi: 10.1007/s00281-018-0707-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shirakawa K., Endo J., Kataoka M., Katsumata Y., Yoshida N., Yamamoto T., et al. IL (Interleukin)-10-STAT3-Galectin-3 axis is essential for osteopontin-producing reparative macrophage polarization after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2018;138(18):2021–2035. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.035047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mukai K., Matsuoka K., Taya C., Suzuki H., Yokozeki H., Nishioka K., et al. Basophils play a critical role in the development of IgE-mediated chronic allergic inflammation independently of T cells and mast cells. Immunity. 2005;23(2):191–202. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gordon S., Taylor P.R. Monocyte and macrophage heterogeneity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5(12):953–964. doi: 10.1038/nri1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Auffray C., Fogg D., Garfa M., Elain G., Join-Lambert O., Kayal S., et al. Monitoring of blood vessels and tissues by a population of monocytes with patrolling behavior. Science. 2007;317(5838):666–670. doi: 10.1126/science.1142883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Biswas S.K., Mantovani A. Macrophage plasticity and interaction with lymphocyte subsets: cancer as a paradigm. Nat Immunol. 2010;11(10):889–896. doi: 10.1038/ni.1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aratani S., Tagawa M., Nagasaka S., Sakai Y., Shimizu A., Tsuruoka S. Radiation-induced premature cellular senescence involved in glomerular diseases in rats. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1) doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-34893-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.I T., Ueda Y., Wörsdörfer P., Sumita Y., Asahina I., Ergün S. Resident CD34-positive cells contribute to peri-endothelial cells and vascular morphogenesis in salivary gland after irradiation. J Neural Transm. 2020;127(11):1467–1479. doi: 10.1007/s00702-020-02256-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thandar M., Yang X., Zhu Y., Huang Y., Zhang X., Huang S., et al. Mesenchymal stem cells derived from adipose tissue and umbilical cord reveal comparable efficacy upon radiation-induced colorectal fibrosis in rats. Am J Cancer Res. 2024;14(4):1594–1608. doi: 10.62347/DRAE5818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Qin L., Tang G., Gui R., Yang Y., Wang L., Xu W., et al. ATRX loss inhibits DDR to strengthen radio-sensitization in p53-deficent HCT116 cells. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):793. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-85085-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang Q., Yang D., Han X., Ren Y., Fan Y., Zhang C., et al. Alarmins and their pivotal role in the pathogenesis of spontaneous abortion: insights for therapeutic intervention. Eur J Med Res. 2024;29(1):640. doi: 10.1186/s40001-024-02236-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Datta S., Rahman M.A., Koka S., Boini K.M. High mobility group box 1 (HMGB1): molecular signaling and potential therapeutic strategies. Cells. 2024;13(23) doi: 10.3390/cells13231946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.He S.J., Cheng J., Feng X., Yu Y., Tian L., Huang Q. The dual role and therapeutic potential of high-mobility group box 1 in cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8(38):64534–64550. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.17885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kwak M.S., Kim H.S., Lee B., Kim Y.H., Son M., Shin J.S. Immunological significance of HMGB1 post-translational modification and redox biology. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1189. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hammad H., Chieppa M., Perros F., Willart M.A., Germain R.N., Lambrecht B.N. House dust mite allergen induces asthma via toll-like receptor 4 triggering of airway structural cells. Nat Med. 2009;15(4):410–416. doi: 10.1038/nm.1946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li M., Song L., Gao X., Chang W., Qin X. Toll-like receptor 4 on islet β cells senses expression changes in high-mobility group box 1 and contributes to the initiation of type 1 diabetes. Exp Mol Med. 2012;44(4):260–267. doi: 10.3858/emm.2012.44.4.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fan Y., Liu B. Expression of toll-like receptors in the mucosa of patients with ulcerative colitis. Exp Ther Med. 2015;9(4):1455–1459. doi: 10.3892/etm.2015.2258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kwok S.K., Cho M.L., Her Y.M., Oh H.J., Park M.K., Lee S.Y., et al. TLR2 ligation induces the production of IL-23/IL-17 via IL-6, STAT3 and NF-kB pathway in patients with primary Sjogren's syndrome. Arthritis Res Ther. 2012;14(2) doi: 10.1186/ar3780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]