Abstract

Background

Children of incarcerated substance-abusing mothers represent a profoundly vulnerable yet under-researched population in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). In Sri Lanka, the intersection of maternal addiction, incarceration and poverty poses complex threats to child health and development. This study explores the lived experiences of such mothers and the perceived risks their children face.

Methods

A qualitative, phenomenological study was conducted using 10 focus group discussions (FGDs) with 48 incarcerated mothers in Sri Lanka’s largest female correctional facility. Participants were purposively sampled to ensure diversity in age, drug use history and caregiving experience. Data were collected through structured, audio-recorded FGDs conducted in Sinhala, transcribed, translated and thematically analysed using Braun and Clarke’s framework. A second-order analysis was performed to interpret systemic drivers.

Results

Five major themes emerged: (1) barriers to healthcare access, (2) intergenerational substance use, (3) social stigma and marginalisation, (4) maternal guilt and psychological burden and (5) coping strategies and resilience. Many mothers described how stigma, fear of withdrawal and trauma hindered timely healthcare for themselves and their children. Substance use was often normalised in their families and workplaces, particularly in contexts of poverty, exploitation and domestic violence. Despite adversity, many participants expressed hope for recovery, supported by kinship networks, particularly maternal figures.

Conclusions

Substance use among incarcerated mothers in Sri Lanka is deeply entwined with structural violence, gendered labour exploitation and intergenerational trauma. Child health interventions must be trauma-informed, gender-responsive and family-centred, promoting rehabilitation while safeguarding child development.

Keywords: Qualitative research, Caregivers, Child Health, Developing Countries, Health Policy

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

Children of incarcerated and substance-abusing mothers are at elevated risk of neglect, developmental delays and psychosocial harm.

In low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), support systems for children of imprisoned mothers are often fragmented or non-existent.

Maternal substance abuse is frequently linked to histories of trauma, poverty and gender-based violence.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

Highlights how healthcare access is undermined by stigma, fear of withdrawal and systemic neglect in the Sri Lankan prison and healthcare systems.

Reveals the role of intergenerational addiction and structural vulnerabilities in perpetuating maternal substance use.

Identifies both risk and resilience factors within familial caregiving, particularly the pivotal role of grandmothers.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

Supports the urgent need for trauma-informed, family-centred interventions for incarcerated mothers and their children in LMICs.

Suggests that child protection policies should integrate developmental monitoring and caregiver support into informal care arrangements.

Reinforces the value of prison-based parenting programmes and gender-sensitive rehabilitation services to break cycles of addiction and disadvantage.

Introduction

Children of incarcerated, substance-abusing mothers represent one of the most vulnerable yet overlooked populations in global public health.1 Parental incarceration alone poses profound risks to child development, but when compounded with maternal substance abuse, the effects on children’s physical, emotional and cognitive well-being are often severe and lasting.2 These children are disproportionately affected by disrupted caregiving, inconsistent access to healthcare, increased exposure to trauma and socioeconomic instability.3 In addition to the effects of incarceration, parental substance use—especially during the prenatal period—has been associated with neurodevelopmental delays, behavioural problems and cognitive deficits in children.4 5 Postnatal substance use by caregivers can further impair attachment, emotional regulation and access to essential healthcare services.6

Globally, women comprise an increasing proportion of the prison population, with many incarcerated for drug-related offences.7 In Sri Lanka, this trend is also evident, with a significant number of incarcerated women being primary caregivers of young children.8 Many of these women have a history of drug dependency, often stemming from complex interactions between poverty, trauma, intimate partner violence and lack of economic opportunities.9 Children born into these environments face a high risk of poor nutrition, delayed development, limited schooling and neglect or abuse.10 Their basic rights—to safety, health and nurturing—are frequently compromised even before their mothers are imprisoned.

While much research explores either the developmental impacts of parental incarceration or the consequences of parental substance use, few studies examine the intersection of both risks, particularly in non-Western settings. This gap is not limited to low- and middle-income countries (LMICs); even in high-income settings, children of substance-using incarcerated mothers are poorly studied, falling between two traditionally separate research streams.

Substance abuse among women in Sri Lanka, particularly those from low-income urban settings, is a growing concern.11 The absence of integrated child protection frameworks and supportive caregiving policies exacerbates the health risks to children. Children born to such mothers may start life already disadvantaged: many are exposed to in-utero substance use, receive inadequate prenatal and postnatal care and lack stable caregiving. On maternal incarceration, children are usually cared for by elderly grandparents or extended family, often in poor conditions with minimal institutional oversight. These caregiving arrangements are informal, fragmented and rarely supported by trained professionals. In many cases, there is no structured follow-up to monitor the child’s physical and developmental milestones or to ensure access to vaccinations, nutrition programmes or psychosocial support. The burden placed on caregivers—who may be ill, impoverished or overwhelmed—further undermines the consistency of care. In this background, the current study aimed to explore the lived experiences of incarcerated substance-abusing mothers in Sri Lanka, focusing on their perceptions of the health and developmental challenges faced by their children. The study also sought to identify the barriers these mothers face in accessing healthcare for themselves and their children, both before and during incarceration.

Methods

Study design

This qualitative study employed a phenomenological approach using focus group discussions (FGDs) to explore the lived experiences and perspectives of incarcerated substance-abusing mothers regarding the health and development of their children. The research aimed to elicit in-depth narratives on the socioeconomic, psychological and cultural drivers of maternal substance use and its perceived impact on child well-being. The COREQ (Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research) checklist was used to guide reporting of the study’s design, data collection, analysis and researcher reflexivity.12

Study setting and participants

The study was conducted in a female correctional facility located within the largest prison in Sri Lanka, where a total of 182 incarcerated mothers with a history of substance abuse and having a child under 5 years of age were identified over 2 years. From this population, 48 participants were selected using purposive sampling to ensure heterogeneity across key variables such as age, type of substance used, caregiving history and ease of access within the prison environment. Special consideration was given to selecting mothers residing in the same prison units concurrently to facilitate the safe and logistically feasible organisation of FGDs.

Sampling strategy

Purposive sampling was guided by maximum variation principles to capture a broad spectrum of experiences. The sampling framework ensured representation of participants across differing lengths of substance use history, stages of motherhood and involvement in child-rearing before imprisonment. Selection also considered participant willingness and ability to communicate within the group setting. 10 FGDs were conducted, each consisting of three to six participants, with group composition designed to encourage open dialogue while maintaining logistical feasibility and security within the prison setting. Thematic saturation was reached by the eighth discussion; however, two additional FGDs were conducted to validate and reinforce emerging themes.

Data collection

Data collection was conducted over a 2-year period and facilitated by the principal investigator (a consultant paediatrician and trained qualitative researcher) with the support of a research assistant. A structured interview guide (online supplemental annex 1) was developed and pilot-tested in a separate non-participating group to refine question clarity and flow. Discussions were conducted in Sinhala, the native language of all participants, in a private space provided within the correctional facility to ensure confidentiality and psychological comfort.

Each FGD lasted approximately 45–60 min. Participants were encouraged to share their experiences freely, and open-ended prompts were used to explore the challenges they faced in parenting, navigating substance use, accessing healthcare and coping with incarceration. All sessions were audio-recorded with participant consent and supplemented with field notes documenting group dynamics and contextual observations.

Data management and analysis

All FGDs were transcribed verbatim in Sinhala and later translated into English for analysis. A thematic analysis was undertaken following Braun and Clarke’s six-phase framework: (1) familiarisation with data, (2) initial code generation, (3) searching for themes, (4) reviewing themes, (5) defining and naming themes, and (6) writing up.13

Manual coding was initially conducted independently by two researchers, with discrepancies resolved through discussion to ensure analytical consistency. Themes were developed inductively, grounded in the data and later mapped onto broader socioecological and structural frameworks through second-order analysis. This helped to contextualise maternal substance use within systemic and intergenerational patterns of disadvantage.

Reflexivity and trustworthiness

To minimise bias and enhance reflexivity, the primary researcher maintained a reflective journal throughout data collection and analysis, noting personal assumptions and emotional responses. Regular debriefing sessions ensured critical appraisal of coding decisions and interpretative neutrality. Triangulation was achieved through team-based coding, field observations and thematic cross-checking across different FGDs. Although full transcript review by participants was not feasible due to prison regulations, member checking was performed by presenting emerging themes to a subset of participants (n=6) to verify resonance with their experiences. This feedback was incorporated into the final thematic framework.

Ethical considerations

Administrative clearance was provided by the Department of Prisons, Sri Lanka. All participants were informed of the study’s purpose, assured of voluntary participation and provided written informed consent prior to inclusion. Privacy and confidentiality were strictly maintained. Sensitive issues were addressed with empathy, and psychological support was available for any participant who experienced distress during or after the discussions.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Results

Among the 48 incarcerated mothers who participated in the study, the largest age group was 26–30 years (n=18, 37.5%), followed by 31–35 years (n=12, 25.0%). The duration of substance abuse varied, with 23 participants (47.9%) reporting less than 1 year of use, 19 (39.6%) reporting 1–5 years, 4 (8.3%) reporting 5–10 years and 2 (4.2%) reporting more than 10 years. In terms of education, 3 participants (12.5%) had no formal schooling, 7 (14.6%) had education below the primary level, 32 (66.7%) had not completed secondary school and 6 (6.3%) had education below the GCE (General Certificate in Education) Advanced Level. Most participants resided in urban settings (n=34, 70.8%). The majority had one child (n=36, 75.0%), followed by 10 (20.8%) with two children and 2 (4.2%) with three children. Occupationally, 25 mothers (52.1%) identified as housewives, 9 (18.8%) worked in spas, 8 (16.7%) were engaged in drug dealing, 2 (4.2%) were employed in hotels or clubs and 4 (8.3%) reported other jobs. Regarding substance use patterns, 26 (54.2%) used sympathomimetics, 22 (45.8%) used opiates, 18 (37.5%) used prescription drugs and 3 (6.3%) used cannabinoids. Polysubstance use was reported by 17 participants (35.4%), while 1 participant (2.1%) reported using other substances.

The results provided critical insights into the complex realities of substance-abusing mothers and the multifaceted challenges they face in safeguarding the health and development of their children. Data from 10 FGDs involving 48 incarcerated mothers revealed five major themes: (1) barriers to healthcare access, (2) intergenerational substance use, (3) social stigma and marginalisation, (4) maternal guilt and psychological burden and (5) coping strategies and resilience (online supplemental annex 2 – Coding tree).

Barriers to healthcare access

Participants frequently reported delays or avoidance in seeking antenatal, postnatal and paediatric healthcare due to stigma, fear of judgement and withdrawal symptoms. Negative experiences in health facilities discouraged continued engagement with services.

When I went to the clinic, some expectant women whispered behind my back. They treated me differently. So, I stopped going. (Participant 23)

Substance use during pregnancy was often concealed due to fear of legal or social repercussions. This avoidance of care posed direct risks to both maternal and child health, particularly in the early developmental period.

Intergenerational substance abuse

Many participants described being raised in households where substance abuse was normalised. Exposure began in early childhood, often involving family members such as parents or spouses.

I grew up in a house where my father, mother and uncles were always using. It never seemed like something bad until I got addicted myself. (Participant 7)

Both my father and husband are drug users. I wanted to change my husband, but I couldn’t. I got dragged into it instead. (Participant 41)

This pattern reflects an entrenched intergenerational cycle, where drug use is socially learnt and normalised from a young age. In some cases, mothers began using drugs as teenagers, often under the influence of peers or intimate partners.

Social stigma and marginalisation

Social exclusion was a recurrent theme. Participants reported being denied housing, employment or community reintegration due to their identity as drug users.

No one wants to rent a house to someone like me. I can’t get a job, so I do whatever I can to survive. (Participant 19)

I was a prostitute and had many problems on the street. We didn’t have money. My friend introduced me to drugs to help me survive the night life. (Participant 37)

Economic vulnerability often led women to informal or exploitative work, such as sex work or spa-based employment, where drug use was normalised or even encouraged for performance.

Maternal guilt and psychological burden

Participants expressed deep emotional pain over the consequences of their substance use on their children. Feelings of guilt, shame and helplessness were common, particularly in relation to missed developmental milestones and disrupted parenting.

I know I have hurt my child, but every time I try to quit, the stress makes me use again. (Participant 18)

One of the worst things is losing good time with your child. It can affect their development. (Participant 40)

My child is having problems with speech. He didn’t get much time with either of us. (Participant 27)

Some mothers reported missing important child health appointments, including immunisation schedules, due to incarceration or drug dependence.

I missed the vaccination sessions for my child. I think my mother did them all. (Participant 47)

This psychological burden was compounded by the fear that their children, now in the care of elderly grandparents, might face abuse or neglect.

My children live with my mother in line houses. She is old now. I worry that my daughter may be abused by men in the village. (Participant 31) (Line houses are rows of small, attached dwellings originally built to house estate workers, often overcrowded and lacking privacy or adequate facilities.)

Coping strategies and resilience

Despite the adversities, many mothers displayed resilience and a strong motivation to change. Those with family support or who had access to structured rehabilitation or parenting programmes expressed greater optimism about the future.

My mother takes care of my child while I am in prison. When I get out, I want to change and be there for my child. (Participant 26)

I work in a spa and drugs helped me do the job properly. But I want a different life for my kids. (Participant 44)

Some participants identified supportive figures—particularly their mothers—as pivotal to their ability to cope, manage addiction and preserve ties with their children.

Second-order analysis

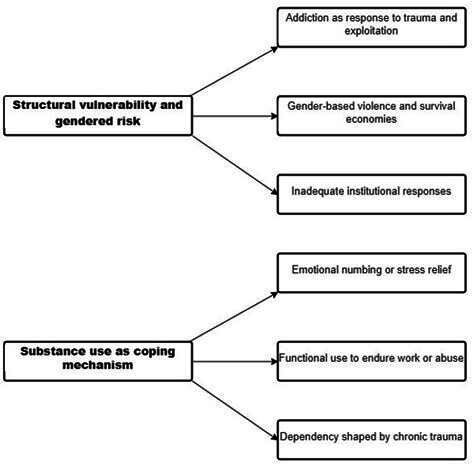

Applying a second-order analysis—interpreting the findings through a socioecological and structural lens—revealed several broader patterns (figure 1):

Figure 1. Structural and psychosocial drivers of maternal substance use and child vulnerability.

Structural vulnerability and gendered pathways to drug use

The narratives reflected how structural determinants such as poverty, gender-based violence, exploitative labour and inadequate housing create gendered pathways into substance use. Most women began using drugs not recreationally, but functionally—to survive, endure trauma or sustain precarious employment. For instance, spa workers and sex workers described drug use as a means to dissociate during work or manage night shifts.

Substance use as symptom and strategy

Rather than viewing substance use merely as deviant behaviour, participants framed it as both a symptom of systemic neglect and a coping strategy. Emotional regulation, escape from violence and increased stamina for night work were commonly cited motivations. This complicates linear narratives of addiction and points toward the need for trauma-informed and gender-responsive intervention models.

The family as both risk and resource

Family dynamics were central to both the risk of addiction and the possibility of recovery. On the one hand, familial substance use-modelled drug behaviour and exposed children to high-risk environments. On the other hand, grandmothers and occasionally mothers-in-law emerged as protective figures, caring for children and enabling temporary continuity of parenting during incarceration. This duality suggests the importance of family-based interventions rather than individual-focused models.

Parenting from the margins

Participants described deep emotional connections to their children, despite prolonged physical separation. Many mothers viewed incarceration as both a rupture and a possible turning point. However, the institutional settings rarely offered parenting support programmes. The lack of developmental monitoring, poor record-keeping and mental health services for mothers contributed to feelings of alienation and helplessness. The findings shed light on the intersecting social, emotional and structural barriers faced by incarcerated substance-abusing mothers. Their narratives pointed to a cycle of trauma, addiction, stigma and marginalisation—compounded by inadequate systemic support. Yet, the resilience displayed by many participants also highlights pathways for recovery and reintegration.

Fear of withdrawal, influences of the family and friends and psychological stress were perceived to be driving forces for substance abuse in mothers. Qualitative data further revealed that maternal fear of withdrawal symptoms and social stigma were major barriers to seeking timely healthcare. The intergenerational effects of substance abuse were evident, with a subset of children identified as being at risk of neglect or abuse, further compounding their vulnerabilities.

Driving forces behind substance abuse by incarcerated mothers

The driving forces behind substance abuse among incarcerated mothers were multifactorial. Family influence played a key role, with many women exposed to drug use through substance-abusing partners or relatives. Physiological dependence, particularly the fear of withdrawal symptoms, was a strong motivator for continued use. Work-related pressures, especially in exploitative or physically demanding jobs like spa work or manual labour, prompted substance use to maintain energy or endurance. Social influences such as peer pressure and emotional or intimacy-related factors, including using drugs to initiate or sustain relationships, also contributed. Psychological distress—including depression, anxiety and trauma—led some women to self-medicate with drugs. Finally, relational dynamics, such as co-dependency and an inability to stop a partner’s drug use, further entrenched substance abuse behaviours.

Discussion

This qualitative study revealed the profound challenges faced by incarcerated, substance-abusing mothers in safeguarding the physical and developmental well-being of their children. The narratives captured through FGDs offer critical insights into how systemic neglect, stigma, poverty and gendered vulnerabilities intersect to compromise both maternal and child health. One of the central findings of this study was the recurring theme of barriers to healthcare access. Mothers described avoiding antenatal and postnatal care due to fear of judgement, stigma and inadequate support within health institutions. In the Sri Lankan context, where substance use among women is harshly stigmatised and often criminalised, care settings may serve more as sites of social exclusion than support. Participants described being shamed by health workers or fellow patients, leading to disengagement from essential services. This underscores the urgent need for training frontline healthcare providers in stigma reduction and the development of non-punitive, trauma-informed models of maternal care.14 In addition, the establishment of integrated programmes that simultaneously address maternal substance use and child development has shown promise in improving health outcomes for both mothers and their children.15 16 Such programmes offer comprehensive, family-centred interventions that promote recovery, parenting skills and child safety, and may be especially relevant in LMIC settings like Sri Lanka where formal support systems are limited.

Many engaged in survival sex work, spa-based employment or informal labour markets that expose them to unsafe environments and normalise drug use. For some, drugs had become a coping mechanism to deal with trauma, domestic violence or the demands of exploitative labour. Others were introduced to substances by partners or family members, reflecting deeply entrenched cycles of intergenerational addiction. Once addicted, the incarcerated mothers faced multiple barriers to seeking help—including stigma, fear of child separation, limited access to rehabilitation services and legal repercussions. Our findings align with reported findings from other studies.17,19

The theme of intergenerational substance abuse reflected deeply entrenched patterns of familial drug use. Many participants reported growing up in homes where drug use was normalised by fathers, husbands or uncles. For some, early exposure began during adolescence through peer pressure or intimate partners. These findings align with previous literature highlighting the familial transmission of substance abuse, not merely through genetics but through social modelling and normalisation.20 This pattern suggests that interventions must extend beyond the individual to target family dynamics and community-level risk factors.21

Social stigma and marginalisation emerged as a significant structural barrier. Participants recounted being denied housing, employment or support due to their identity as drug users and former sex workers. In many cases, survival strategies—such as spa work or transactional sex—were closely tied to drug use, either as a means of coping with exploitation or as a requirement for performance. These experiences highlight the gendered nature of addiction in low-resource settings, where poverty and violence push women into high-risk, low-agency environments.22 Rehabilitation efforts must therefore be gender-sensitive and address the socioeconomic drivers of addiction, not merely its symptoms.23

Maternal guilt and psychological burden were expressed with remarkable emotional clarity. Participants mourned lost time with their children, developmental setbacks and broken maternal bonds. The psychological weight of knowing their children may suffer neglect or abuse in their absence created feelings of helplessness and despair. Yet, despite these burdens, many mothers expressed a desire to change—demonstrating that incarceration, while punitive, could also serve as a potential turning point. This reinforces the value of prison-based parenting and mental health programmes that can facilitate emotional healing and promote child-focused rehabilitation.24

The theme of coping strategies and resilience was particularly powerful. Mothers who had strong family support—especially from their own mothers—were more optimistic about rebuilding their lives and reconnecting with their children. Others cited the desire to ‘be there’ for their children as a motivation to pursue recovery. These findings suggest that even in the context of trauma, incarceration and addiction, there exists a potential for change and reintegration. This reinforces the argument for post-release support programmes that enable parenting continuity, family reunification and structured rehabilitation.25

The second-order analysis of the data revealed how addiction, parenting and incarceration must be viewed through a structural lens. Substance use among these women was rarely about recreation; rather, it was a survival mechanism in response to violence, emotional pain and exploitative labour. Addiction was both a symptom and a strategy—offering temporary relief while compounding long-term harm. Interventions must therefore be trauma-informed, grounded in harm reduction and situated within broader social protection policies that address housing, employment and intimate partner violence.26 Additionally, the study highlights the dual role of the family as both risk and resource. While many participants were introduced to drugs by family members, others relied on those same family systems—particularly grandmothers—to care for their children during incarceration. This duality underscores the importance of family-based interventions, where recovery and child protection are pursued in tandem.27 Strengthening kinship care systems, training caregivers and monitoring child development within these informal arrangements could enhance outcomes for affected children.28

Several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the study was conducted within a single female correctional facility in Sri Lanka, and the findings may not be generalisable to other prisons or cultural settings. The sample, though purposively diverse, may not reflect the full spectrum of experiences among incarcerated substance-using mothers nationally. Second, while efforts were made to ensure openness during FGDs, the prison setting may have constrained participants’ willingness to share deeply personal or traumatic experiences. Some participants may have under-reported experiences of violence, abuse or illegal activity due to fear of reprisal or judgement. Individual in-depth interviews might have elicited more nuanced narratives, particularly around themes of trauma and abuse. Lastly, this study did not systematically assess developmental outcomes or health records of the children. Therefore, while the maternal narratives provide valuable insights, they cannot substitute for objective developmental assessments. Future research should consider a mixed-methods approach, integrating qualitative insights with clinical data on child health and development.

Conclusion

This study highlights the intersecting challenges faced by substance-abusing incarcerated mothers in Sri Lanka and the consequential risks to child health and development. The findings point to urgent gaps in maternal healthcare, child protection and rehabilitation services, shaped by stigma, poverty and systemic neglect. Yet, within these narratives of trauma are also stories of resilience and hope. Addressing these issues requires trauma-informed, gender-responsive and family-centred interventions that extend beyond incarceration. Policymakers must prioritise holistic care models that support both mothers and children, breaking intergenerational cycles of addiction and disadvantage while promoting recovery, dignity and child well-being.

Supplementary material

Footnotes

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Consent obtained directly from patient(s).

Ethics approval: Permission to carry out the study was obtained from the Ethics Review Committee, Postgraduate Institute of Medicine, University of Colombo (ERC/PGIM/2024/007).

Data availability free text: All data were de-identified for this research report. The datasets used or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Lee RD, Fang X, Luo F. The impact of parental incarceration on the physical and mental health of young adults. Pediatrics. 2013;131:e1188–95. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herreros-Fraile A, Carcedo RJ, Viedma A, et al. Parental Incarceration, Development, and Well-Being: A Developmental Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20:3143. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20043143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beresford S, Loucks N, Raikes B. The health impact on children affected by parental imprisonment. BMJ Paediatr Open . 2020;4:e000275. doi: 10.1136/bmjpo-2018-000275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith VC, Wilson CR, USE COS, et al. Families Affected by Parental Substance Use. Pediatrics. 2016;138:e20161575. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yeoh SL, Eastwood J, Wright IM, et al. Cognitive and Motor Outcomes of Children With Prenatal Opioid Exposure: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open . 2019;2:e197025. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.7025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saran A, Albright K, Adona J, et al. PROTOCOL: Megamap of systematic reviews and evidence and gap maps on the effectiveness of interventions to improve child well‐being in low‐ and middle‐income countries [Update in: Campbell Syst Rev. 2020 Oct 28;16(4):e1116. doi: 10.1002/cl2.1116] Campbell Systematic Reviews. 2019;15:e1057. doi: 10.1002/cl2.1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Staton M, Tillson M, Levi MM, et al. Identifying and Treating Incarcerated Women Experiencing Substance Use Disorders: A Review. Subst Abuse Rehabil. 2023;14:131–45. doi: 10.2147/SAR.S409944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khan R. Women’s vulnerability for drug related offences in Sri Lanka: with special reference low-income area in Colombo. Sljsd. 2021;1:35–53. doi: 10.4038/sljsd.v1i1.19. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mehr JB, Bennett ER, Price JL, et al. Intimate partner violence, substance use, and health comorbidities among women: A narrative review. Front Psychol. 2022;13:1028375. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1028375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dallaire DH, Zeman JL, Thrash TM. Children’s experiences of maternal incarceration-specific risks: predictions to psychological maladaptation. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2015;44:109–22. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2014.913248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hapangama A, Dasanyake DGBMS, Kuruppuarachchi KALA, et al. Substance use disorders and their correlates among inmates in a Sri Lankan prison. J Postgrad Inst Med. 2021;8:157. doi: 10.4038/jpgim.8334. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19:349–57. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weber A, Miskle B, Lynch A, et al. Substance Use in Pregnancy: Identifying Stigma and Improving Care. Subst Abuse Rehabil. 2021;12:105–21. doi: 10.2147/SAR.S319180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deutsch SA, Donahue J, Parker T, et al. Supporting mother-infant dyads impacted by prenatal substance exposure. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2021;129:106191. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2021.106191. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Niccols A, Milligan K, Smith A, et al. Integrated programs for mothers with substance abuse issues and their children: a systematic review of studies reporting on child outcomes. Child Abuse Negl. 2012;36:308–22. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hossain M, Zimmerman C, Abas M, et al. The relationship of trauma to mental disorders among trafficked and sexually exploited girls and women. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:2442–9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.173229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ullman SE, Lorenz K, Kirkner A, et al. Postassault Substance Use and Coping: A Qualitative Study of Sexual Assault Survivors and Informal Support Providers. Alcohol Treat Q. 2018;36:330–53. doi: 10.1080/07347324.2018.1465807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kramer C, Bradley D, Shlafer RJ, et al. Maternal health and incarceration: advancing pregnancy justice through research. Health Justice. 2025;13:36. doi: 10.1186/s40352-025-00343-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neppl TK, Diggs ON, Cleveland MJ. The intergenerational transmission of harsh parenting, substance use, and emotional distress: Impact on the third-generation child. Psychol Addict Behav. 2020;34:852–63. doi: 10.1037/adb0000551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kumpfer KL. Family-based interventions for the prevention of substance abuse and other impulse control disorders in girls. ISRN Addict. 2014;2014:308789. doi: 10.1155/2014/308789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fonseca F, Robles-Martínez M, Tirado-Muñoz J, et al. A Gender Perspective of Addictive Disorders. Curr Addict Rep. 2021;8:89–99. doi: 10.1007/s40429-021-00357-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Green CA. Gender and use of substance abuse treatment services. Alcohol Res Health. 2006;29:55–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Milavetz Z, Pritzl K, Muentner L, et al. Unmet Mental Health Needs of Jailed Parents with Young Children. Fam Relat. 2021;70:130–45. doi: 10.1111/fare.12525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Breuer E, Remond M, Lighton S, et al. The needs and experiences of mothers while in prison and post-release: a rapid review and thematic synthesis. Health Justice. 2021;9:31. doi: 10.1186/s40352-021-00153-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wolfson L, Schmidt RA, Stinson J, et al. Examining barriers to harm reduction and child welfare services for pregnant women and mothers who use substances using a stigma action framework. Health Soc Care Community. 2021;29:589–601. doi: 10.1111/hsc.13335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Slesnick N, Zhang J. Family systems therapy for substance-using mothers and their 8- to 16-year-old children. Psychol Addict Behav. 2016;30:619–29. doi: 10.1037/adb0000199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu Q, Zhu Y, Ogbonnaya I, et al. Parenting intervention outcomes for kinship caregivers and child: A systematic review. Child Abuse Negl. 2020;106:104524. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]