Abstract

Thiolutin and 2,2-dioxidothiolutin are sulfur-containing antibiotics discovered through a targeted high-throughput screening strategy designed to identify compounds with antimicrobial activity. The producing strain, JHD1T, is an actinomycete isolated from marine sediment collected in Chonburi Province, Thailand. Chemotaxonomic characteristics and 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis indicated that strain JHD1T belongs to the genus Streptomyces. Taxonomic analysis using a polyphasic approach further supported its placement within the genus Streptomyces. The strain exhibited low similarity to its closest known relatives, Streptomyces alkaliterrae OF1T and Streptomyces chumphonensis KK1-2T, with average nucleotide identity based on MuMmer ultra-rapid aligning tool (ANIm) values of 85.7–86.2%, average amino acid identity (AAI) values of 71.8–78.1%, and digital DNA–DNA hybridization (dDDH) values of 23.4–25.0%, all well below the established thresholds for species delineation. These results reveal that strain JHD1T represents a novel species within the genus Streptomyces, for which the name Streptomyces marinisediminis sp. nov. is proposed. The crude extract obtained from the culture broth of strain JHD1T exhibited strong antimicrobial activity against Gram-positive bacteria and led to the discovery of two promising secondary metabolites, thiolutin and 2,2-dioxidothiolutin, along with 8-amino-2H-benz[e][1,3]oxazine-2,4(3H)-dione, benadrostin, 2,3-dihydroxybenzamide, and 2-hydroxy-3-methoxybenzamide. In this study, 2,2-dioxidothiolutin was structurally confirmed for the first time by X-ray crystallographic analysis. Interestingly, thiolutin demonstrated strong anti-human small cell lung cancer (NCI-H187) activity, with an IC₅₀ value of 0.35 µg/mL, and also showed cytotoxicity against human breast cancer (MCF-7) cells, with an IC₅₀ value of 5.61 µg/mL.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-15081-x.

Keywords: Marine Streptomyces, Polyphasic taxonomic characterization, Whole-genome sequence analysis, Thiolutin

Subject terms: Biotechnology, Microbiology

Introduction

The ocean represents a vast reservoir of microbial diversity, where microorganisms play essential roles in nutrient cycling, primary production, and the overall maintenance of marine ecosystem health. Marine microorganisms have garnered significant attention in the fields of pharmaceuticals, biotechnology, and agriculture due to their capacity to produce structurally diverse and biologically active natural products1. Among these, actinomycetes are recognized as one of the most promising groups, frequently isolated from marine environments. These marine-derived actinomycetes are prolific producers of secondary metabolites, many of which exhibit potent antimicrobial properties and hold potential as leads for novel antibiotic development. In addition to antibiotics, marine actinomycetes have been reported to produce antifungal, anticancer, antiviral, and other therapeutically valuable compounds2. Some notable examples include the discovery of actinomycin and virginiamycin, both of which have been developed into therapeutic agents. The ability of actinomycetes to produce novel secondary metabolites makes them a valuable resource for drug discovery, particularly in the context of rising antibiotic resistance3,4. Marine Streptomyces species represent a significant group of actinomycetes widely recognized for their capacity to produce bioactive compounds, especially antibiotics, and have been extensively studied in biotechnology and pharmaceutical research. To date, ongoing isolation and characterization efforts have led to the discovery of numerous biologically active secondary metabolites from marine-derived Streptomyces species. For example, alpiniamides H and I, isolated from Streptomyces sp. ZS-A65, exhibited antibiofilm activity against Pseudomonas aeruginosa5. Hydroxycapsimycin and brokamycin, polycyclic tetramate macrolactams from marine-derived Streptomyces sp. KKMA-0239, demonstrated antibacterial activity against Mycobacterium intracellulare and drug-resistant Mycobacterium avium6. Deoxyvasicinone, a tricyclic quinazoline alkaloid produced by Streptomyces sp. CNQ-617, showed promising anti-melanogenic effects by downregulating melanogenic enzymes7. These findings underscore the potential of marine-derived Streptomyces species as sources of novel bioactive metabolites with therapeutic relevance. In the course of our ongoing search for bioactive secondary metabolite-producing actinomycetes from natural environments, a Streptomyces-affiliated strain, designated JHD1T, was isolated from marine sediment. The taxonomic classification of this strain was conducted using a polyphasic approach. Additionally, biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) were predicted based on the genome of strain JHD1T. Notably, the crude extract of strainJHD1T exhibited a broad spectrum of biological activities, including antimalarial activity against Plasmodium falciparum strain K1 (IC₅₀ = 62.5 µg/ml), antibacterial activity against Bacillus cereus ATCC 11778 and Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 29213 (MIC = 31.25 and 62.5 µg/ml, respectively), and cytotoxicity against MCF-7 (human breast cancer, ATCC HTB-22) and NCI-H187 (human small-cell lung cancer, ATCC CRL-5804) cell lines (IC₅₀ = 15.6 µg/ml). As a result, chemical investigation of the fermentation broth extract of strain JHD1T was carried out, leading to the identification of two promising compounds, thiolutin and 2,2-dioxidothiolutin, together with four known compounds including 8-amino-2H-benz[e][1,3]oxazine-2,4(3H)-dione, benadrostin, 2,3-dihydroxybenzamide, and 2-hydroxy-3-methoxybenzamide. The biological activities of the purified compounds, including antibacterial, antimalarial, and cytotoxic effects against both cancerous (MCF-7 and NCI-H187) and non-cancerous (Vero) cell lines, were also evaluated.

Results and discussion

Polyphasic taxonomic characterization of strain JHD1T

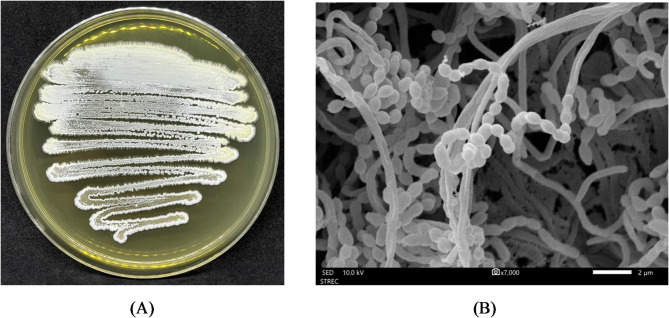

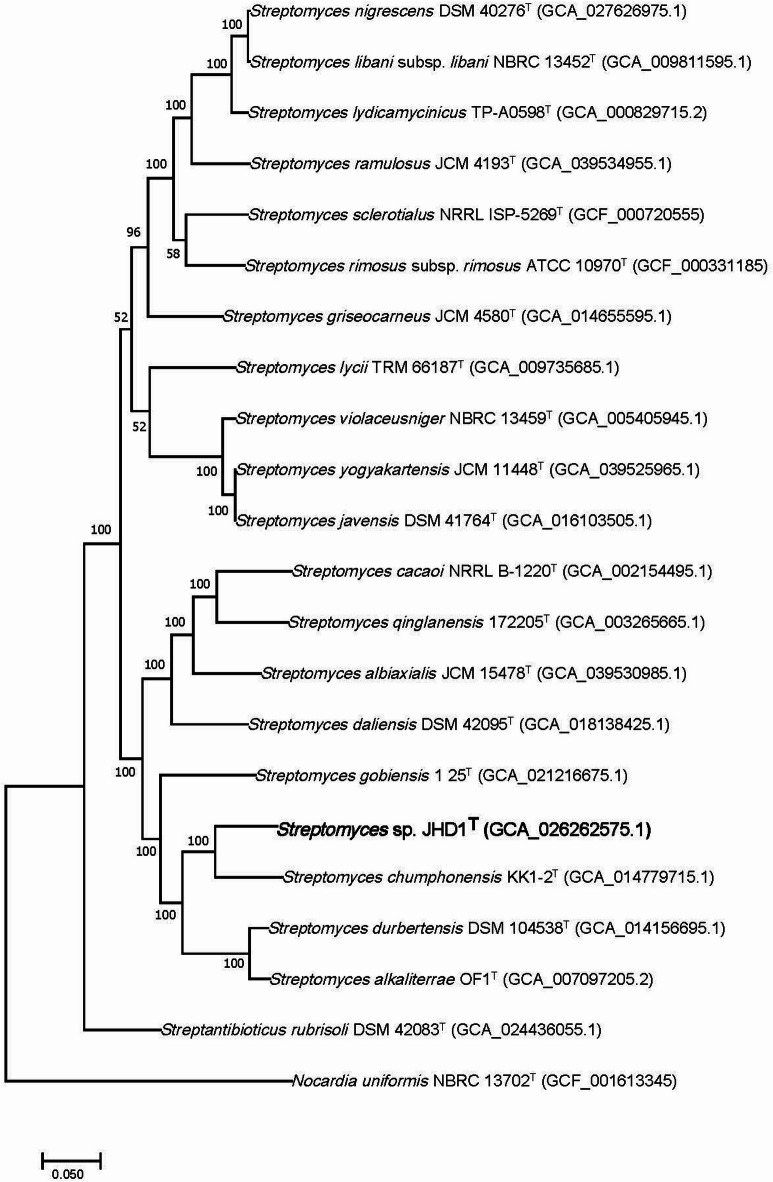

The marine environment undeniably acts as a prolific reservoir for the identification of novel bioactive secondary metabolite-producing actinomycetes. Marine ecosystems harbor a diverse array of microorganisms, including actinomycetes, which thrive under unique and often extreme conditions. These organisms are well-known for their capacity to synthesize a wide variety of bioactive secondary metabolites, many of which demonstrate promising antibacterial, antifungal, anticancer, and antiviral properties. The relatively underexplored nature of marine environments renders them an invaluable and largely untapped source of novel bioactive compounds with substantial therapeutic potential8,9. Hence, actinomycetes residing in marine ecosystems are anticipated to exhibit distinct characteristics compared to those found in other environments. Strain JHD1T was isolated from marine sediment collected in Chonburi Province, Thailand (12°52′54.3″N, 100°52′54.0″E). The marine sediment sample was initially air-dried at ambient temperature (30 °C) and subsequently subjected to heat treatment at 100 °C for 45 min. Following this, the sample was serially diluted to a 10⁻³ dilution (1,000-fold) using 0.01% sterile sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) in seawater. Aliquots of the diluted suspension were then spread onto modified starch-casein nitrate seawater agar supplemented with 50 mg/l nalidixic acid and 200 mg/l nystatin. The strain grew well on International Streptomyces Project number 2 (ISP 2), ISP 4, and ISP 6 media. Moderate growth was observed on ISP 5, ISP 7, and nutrient agar (NA), while poor growth occurred on Czapek’s sucrose and ISP 3. The substrate mycelium was light yellowish-brown on ISP 2, ISP 4, and ISP 6. Greyish white to yellowish white aerial mycelium was clearly visible on ISP 2, ISP 4, ISP 6, and NA after 14 days of incubation at 30 °C. Greenish yellow diffusible pigments were detected on ISP 2, ISP 4, ISP 5, ISP 7, and NA media (Table S1). Strain JHD1T produced spiral chains of ovoid-shaped spores (0.4–0.5 × 0.8–1.0 μm) with smooth surfaces, borne directly on the aerial mycelium (Fig. 1). Whole-cell hydrolysates of strain JHD1T contained LL-diaminopimelic acid, and ribose, galactose, and glucose were detected as cell wall sugars. This chemotaxonomic profile is commonly observed in Streptomyces species10. The polar lipid profile included diphosphatidylglycerol (DPG), phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), phosphatidylglycerol (PG), phosphatidylinositol (PI), phosphatidylinositol mannoside (PIM), two unidentified phospholipids (PLs), and two unidentified lipids (Ls) (Fig. S1). The major menaquinones (MK) were MK-9(H₈) (44.4%), MK-9(H₆) (30.9%), and MK-9(H₄) (16.3%), while MK-9(H₂) (8.4%) was a minor component. Cellular fatty acid analysis revealed that the major fatty acids (> 10%) were anteiso-C₁₅:₀ (21.3%), iso-C₁₆:₀ (33.3%), and anteiso-C₁₇:₀ (14.9%). Minor components included iso-C₁₄:₀, iso-C₁₅:₀, C₁₆:₀, iso-C₁₇:₀, C₁₈:₁ ω9c, iso-C₁₈:₀, anteiso-C₁₉:₀, and anteiso-C₁₇:₁ ω9c (Table S2). The fatty acid profile was similar to those of closely related Streptomyces type strains, Streptomyces alkaliterrae OF1T and Streptomyces chumphonensis KK1-2T. The morphological and chemotaxonomic characteristics of strain JHD1T are consistent with those of the genus Streptomyces10. The 16S rRNA gene sequence comparison is a foundational method for the identification and classification of novel actinomycete and bacterial species. A sequence similarity of ≤ 98.65% with any validly published species indicates the potential discovery of a previously unidentified taxon11. The 16S rRNA gene sequence of strain JHD1T (1,503 bp) showed that it belongs to the genus Streptomyces. It shared the highest sequence similarity with S. alkaliterrae OF1T (98.48%), which is below the species delineation threshold of 98.65%. The next closest relatives were Streptomyces lycii TRM 66187T (98.35%) and Streptomyces qinglanensis 172205T (98.34%), further supporting the novelty of the strain. Phylogenetic analysis using neighbor-joining (NJ) and maximum-likelihood (ML) methods placed strain JHD1T in a clade with Streptomyces gobiensis 1–25, although the bootstrap support was weak (< 50%) (Figs. S2 and S3). In contrast, the maximum-parsimony (MP) tree showed that JHD1T formed a distinct clade with S. alkaliterrae OF1T and S. chumphonensis KK1-2T (Fig. S4), suggesting phylogenetic separation from these close relatives. While 16S rRNA gene analysis provides initial insights, genome-based metrics such as average nucleotide identity based on MuMmer ultra-rapid aligning tool (ANIm) and digital DNA–DNA hybridization (dDDH) offer greater resolution and are now considered gold standards for species delineation in actinomycetes and other bacteria. Thus, the genome of strain JHD1T was analyzed in comparison with its closest Streptomyces type strains. The draft genome sequence of strain JHD1T, deposited in GenBank under accession number JAPKFL000000000, comprises 5.6 Mbp across 141 contigs, with an N50 of 170.8 kbp and a G + C content of 74.7%. A total of 4,888 predicted genes were identified, including 4,689 protein-coding genes (Table S3). Phylogenomic analysis using Automated Multi-Locus Species Tree (autoMLST) and the Type (Strain) Genome Server (TYGS) revealed that strain JHD1T clustered closely with S. chumphonensis KK1-2T with strong bootstrap support (100%) (Fig. 2; Fig. S5), but was clearly separated from the clade containing S. gobiensis 1–25T. According to current taxonomic standards, species-level boundaries are defined by ANIm values below 95%12 and dDDH values below 70%13. Strain JHD1T exhibited ANIm values of 85.7–86.2% and dDDH values of 23.4–25.0% compared to S. alkaliterrae OF1T and S. chumphonensis KK1-2T (Table 1), supporting its classification as a distinct species. In addition to genomic data, comparative phenotypic characterization further distinguished strain JHD1T from its closest type strains. Notable differences included tolerance to a maximum growth temperature of 40 °C, nitrate reduction capability, oxidase production, and the utilization of dextran, D-lactose, and xylitol. Unlike S. alkaliterrae OF1T, strain JHD1T was unable to assimilate inulin, D-mannitol, D-melibiose, D-raffinose, L-rhamnose, or sucrose, and did not produce melanin. Compared to S. chumphonensis KK1-2T, strain JHD1T could hydrolyze urea and gelatin and utilize D-cellobiose, D-fructose, glycerol, 4-hydroxyproline, L-methionine, L-proline, L-serine, L-valine, DL-2-aminobutyric acid, L-arginine, and L-phenylalanine, whereas S. chumphonensis KK1-2T could not (Table 2). Taken together, the genotypic and phenotypic data clearly support the conclusion that strain JHD1T represents a novel species of the genus Streptomyces, for which the name Streptomyces marinisediminis sp. nov. is proposed. The type strain is JHD1T (= TBRC 15653T = NBRC 115639T).

Fig. 1.

A, Colonial appearance of Streptomyces sp. JHD1T; B, Scanning electron micrograph of strain JHD1T grown on ISP 2 seawater agar for 21 days at 30 °C. Bar, 2 μm.

Fig. 2.

Phylogenomic analysis of Streptomyces sp. JHD1T and type strains affiliated to the genus Streptomyces based on 100 bacterial conserved single copied gene sets of the members. The bootstrap values on the nodes are displayed by > 50.

Table 1.

ANIm, AAI, and digital DNA-DNA (dDDH) hybridization relatedness values of Streptomyces sp. JHD1T and the closest type strains.

| Query genome | Reference genome | ANIm (%) | AAI (%) | Digital DNA-DNA hybridization relatedness | G + C difference | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formula 2* | ||||||||

| % dDDH | Model C.I. (%) | Distance | Prob. DDH ≥ 70 (same species) | |||||

| Strain JHD1T | S. chumphonensis KK1-2T | 86.2 | 78.1 | 25.0 | 22.7 – 27.5 | 0.1235 | 0.44 | 1.4 |

| S. alkaliterrae OF1T | 85.7 | 71.8 | 23.4 | 21.1 – 25.9 | 0.1447 | 0.09 | 2.74 | |

*Formula 2: a formula (identities/HSP length) that is liberated of genome length and is thus prosperous against the use of incomplete draft genomes.

Table 2.

Phenotypic features of Streptomyces sp. JHD1T compared to its related type strains.

| Characteristics | Streptomyces sp. JHD1T | Streptomyces alkaliterrae OF1T | Streptomyces chumphonensis KK1-2T |

|---|---|---|---|

| NaCl % w/v tolerance | 0–10 | 0–8 | 0–10 |

| pH range for growth | 6–8 | 6–12 | 6–8 |

| Temperature range for growth (°C) | 20–37 | 12–40 | 12–40 |

| Starch hydrolysis | + | − | + |

| Hydrolysis of urea | + | + | − |

| Gelatin liquefaction | + | + | − |

| Melanin production | − | + | − |

| Nitrate reduction | − | − | + |

| Oxidase activity | + | − | − |

| Carbon utilization | |||

| d-Cellobiose | + | + | − |

| Dextran | + | − | − |

| d-Fructose | + | + | − |

| Glycerol | + | + | − |

| Myo-inositol | − | + | − |

| Inulin | − | w | − |

| d-Lactose | + | − | − |

| d-Mannitol | − | + | − |

| d-Mannose | + | + | w |

| d-Melibiose | − | + | − |

| d-Raffinose | − | + | − |

| l-Rhamnose | − | + | − |

| Salicin | + | − | + |

| Sucrose | − | + | − |

| Xylitol | + | − | − |

| Nitrogen utilization | |||

| 2-Aminobutyric acid | − | w | − |

| l-arginine | w | + | + |

| l-histidine | w | + | + |

| 4-Hydroxyproline | + | w | − |

| l-Methionine | + | w | − |

| l-Proline | + | + | − |

| l-Serine | + | w | − |

| l-Valine | + | w | − |

| Enzymatic activity | |||

| Alkaline phosphatase | w | + | + |

| Esterase (C 4) | w | + | + |

| Esterase Lipase (C 8) | w | + | + |

| Trypsin | − | w | − |

| Acid phosphatase | − | + | − |

| α-Glucosidase | − | + | + |

| β-Glucosidase | − | − | w |

All other phenotypic data were determined in this study. +, Positive; −, Negative; w, Weakly positive.

The prediction for secondary metabolite production in the genome of strain JHD1T

The biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) in the genome of strain JHD1T and its closely related type strains were identified using antiSMASH version 7.0. Comparative analysis with S. chumphonensis KK1-2T and S. alkaliterrae OF1T revealed that strain JHD1T possesses a diverse array of BGCs, including those predicted to encode butyrolactone, cyclodipeptide synthase (CDPS), ectoine, type III polyketide synthase (type III PKS), hydrogen cyanide, lanthipeptide classes I–III, lassopeptide, lipolanthine, non-ribosomal peptide synthetase-independent siderophore (NI-siderophore), heterocyst glycolipid synthase-like ketide synthase (hgIE-KS), NRP-metallophore, phosphonate, and trans-acyltransferase polyketide synthase (trans-AT PKS) gene clusters. Notably, strain JHD1T was particularly rich in clusters associated with type I polyketide synthase (type I PKS), non-ribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS), and terpene biosynthesis. The hgIE-KS and phosphonate gene clusters were uniquely detected in the genome of strain JHD1T and were absent in its closely related strains (Fig. 3). The genome of strain JHD1T, unlike those of S. chumphonensis KK1-2T and S. alkaliterrae OF1T, contained BGCs with high similarity confidence associated with the synthesis of several notable bioactive compounds: 2-Methoxy-5-methyl-6-(13-methyltetradecyl)-1,4-benzoquinone, a derivative of 1,4-benzoquinone, is known for its antimicrobial activity14. SapB, a lantibiotic-like peptide, is important for aerial mycelium formation in the filamentous bacterium Streptomyces coelicolor. It also plays a critical role in sphingolipid metabolism by acting as an activator protein for specific lysosomal hydrolases involved in glycosphingolipid degradation15. Isorenieratene, a carotenoid pigment belonging to the aryl carotenoid class, is primarily found in green sulfur bacteria (Chlorobiaceae). This compound exhibits strong radical scavenging activity, often greater than that of β-carotene, and can neutralize reactive oxygen species (ROS), thereby reducing oxidative damage to DNA, proteins, and lipids16. Naringenin, a typical plant secondary metabolite, is produced by Streptomyces clavuligerus. This flavonoid, commonly found in citrus fruits such as grapefruits and oranges, is well known for its diverse bioactivities, including antioxidant, anticancer, antimicrobial, and neuroprotective effects17. Sibiromycin is an antitumor antibiotic belonging to the pyrrolobenzodiazepine (PBD) family. It is recognized for its ability to bind to DNA and inhibit essential cellular processes. This compound is naturally produced by Streptosporangium sibiricum and is structurally related to other DNA-alkylating agents with potent antitumor potential18. These findings underscore the biosynthetic potential of strain JHD1T for producing medically relevant secondary metabolites (Table S4). Similarly, there are numerous documented examples where novel Streptomyces strains produce only known compounds despite having distinct BGCs. For example, S. coelicolor A3 possesses over 20 BGCs but produces only a few known compounds under normal cultivation19. Marine Streptomyces collections show that phylogenetically distinct strains with different BGC profiles often produce overlapping sets of known metabolites like actinomycin and streptomycin derivatives20.

Fig. 3.

Biosynthetic gene clusters (BCGs) presented in Streptomyces sp. JHD1T and the closest type strains. Cluster type designations provided by antiSMASH 7.1 analysis.

The high number of BGCs identified in the genome of strain JHD1T suggests that it was a promising actinomycete capable of producing a wide variety of valuable secondary metabolites. Notably, some of these gene clusters exhibited low sequence similarity to those associated with known bioactive compounds, indicating the potential for novel metabolite discovery. For example, echoside A–E, a group of structurally diverse natural products produced by Streptomyces sp. LZ35, exhibit various biological activities, including antimicrobial, anticancer, and neuroprotective effects, as well as inhibitory activity against DNA topoisomerase I and IIα21. Phthoxazolin, an oxazole-containing polyketide produced by Streptomyces species such as Streptomyces avermitilis, displays broad-spectrum anti-oomycete and herbicidal activities. Its biosynthesis involves a trans-acyltransferase (trans-AT) type I polyketide synthase (PKS) system. Phthoxazolin A’s unique mode of action as a cellulose biosynthesis inhibitor makes it a promising candidate for developing new herbicides, particularly for combating herbicide-resistant weeds22. Lavendiol, a bisabolane-type sesquiterpenoid diol, has been isolated from both Lavandula species and S. lavendulae FRI-5. It demonstrates antimicrobial, anticancer, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory properties23. Terpenomycin, a rare polyketide-terpenoid hybrid antibiotic isolated from Streptomyces sp. DSM 4137 and Nocardia terpenica AUSMDU00012715, contains both terpenoid and polyketide moieties. It has attracted attention for its potent antimicrobial and antitumor activities24. Lasalocid, a polyether ionophore antibiotic produced by several Streptomyces species including S. lasaliensis, is widely studied for its ion-transporting capabilities and broad biological activities, such as antibacterial, anticoccidial, antiviral, and anticancer effects25. Pyrroloformamide A–D, members of the dithiolopyrrolone family of natural products, were isolated from Streptomyces sp. CB02980. These compounds are distinguished by a unique bicyclic core featuring a disulfide or thiosulfonate bridge, which is essential for their biological activity, including strong antibacterial and cytotoxic effects. Their biosynthesis involves the pyf gene cluster, including pyfE, a nonribosomal peptide synthetase that assembles the core Cys–Cys dipeptide precursor for the dithiolopyrrolone scaffold, as well as pyfC and pyfN, which are standalone type II thioesterases involved in pathway optimization. Notably, overexpression of pyfN has been shown to increase production of pyrroloformamides A and B by more than twofold26. Overall, the genomic data suggest that strain JHD1T harbored significant biosynthetic potential for the production of diverse and novel secondary metabolites, especially those originating from PKS and NRPS pathways, which are major sources of bioactive compounds (Table S5).

The analysis of the Streptomyces sp. JHD1T genome sequence revealed a biosynthetic gene cluster responsible for producing thiolutin, a member of the dithiolopyrrolone family that has promising clinical applications as an antitumor agent27. At the heart of this molecular assembly line lies an architecturally NRPS containing the cyclization (Cy), adenylation (A), and thiolation (T) domain triad (Table S6). We identified this specialized Cy-A-T arrangement within the homE gene, which produces a remarkably large protein (1,077 amino acids, HomE) sharing significant family resemblance (69.15% sequence identity) with its relative EntF from Streptomyces sp. CAI 127 (Table 3). The cluster encompasses nine functionally distinct genes (Table 3) that orchestrate the assembly of the characteristic pyrrolinonodithiole scaffold of thiolutin. As illustrated in Table 3, this gene cluster encodes a sophisticated enzymatic consortium: HomA (acylation), HomD (redox chemistry), HomF (decarboxylation), and HomC (chain release), collectively orchestrating the precise molecular assembly of thiolutin28. The Cy-A-T domain arrangement plays a pivotal role in catalyzing heterocyclization reactions that generate distinctive ring structures in the peptide backbone, a structural feature responsible for the broad-spectrum antimicrobial and potential anticancer properties that characterize dithiolopyrrolones28,29. The notable sequence conservation observed across diverse Streptomyces species (with identity values ranging from 69.15 to 100%, Table 3) underscores the evolutionary significance of this biosynthetic pathway, aligning with previously characterized dithiolopyrrolone clusters in other organisms, such as S. clavuligerus and various marine bacteria30,31. Our chemical analysis provided definitive confirmation that Streptomyces sp. JHD1T actively synthesizes thiolutin and its derivative (2,2-dioxidothiolutin), establishing a clear functional connection between the identified genetic elements and the resultant bioactive metabolite.

Table 3.

Functional annotation and homology analysis of the putative thiolutin biosynthetic gene cluster of Streptomyces sp. JHD1T.

| Gene | Sizea | Protein homologb and origins | Identity/similarity (%) | Proposed function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| homA | 254 | WDH52_12815 (MGD9484121) Streptomyces sp. TRM70308 | 99.21/99.60 | N-acyltransferase |

| homB | 417 | CaiA (WP_282537759), S. luteolus | 93.51/96.39 | Acyl-CoA dehydrogenase |

| homC | 257 | GrsT (WP_405508461), S. cyaneofuscatus | 70.33/78.46 | Thioesterase |

| homD | 487 | BetA (WP_336923583), Streptomyces sp. JWR5-1 | 100.00/100.00 | Oxidoreductase |

| homE | 1,077 | EntF (WP_175514800), Streptomyces sp. CAI 127 | 69.15/78.82 | NRPS |

| homF | 222 | WDH52_19060 (WP_427154818), Streptomyces sp. TRM70308 | 99.55/100.00 | Decarboxylase |

| homG | 126 | TrHb2_Mt-trHbO-like_O (WP_308294658) Streptomyces sp. JJ66 | 92.86/97.62 | Globin |

| homH | 447 | AraJ (WP_265946363), Streptomyces sp. JWR5-1 | 99.76/100.00 | Transmembrane efflux protein |

| homI | 497 | TrxB (WP_279951745), S. chitinivorans | 90.71/92.52 | Thioredoxin reductase |

aNumbers are in amino acids.

bNCBI accession numbers are in parentheses.

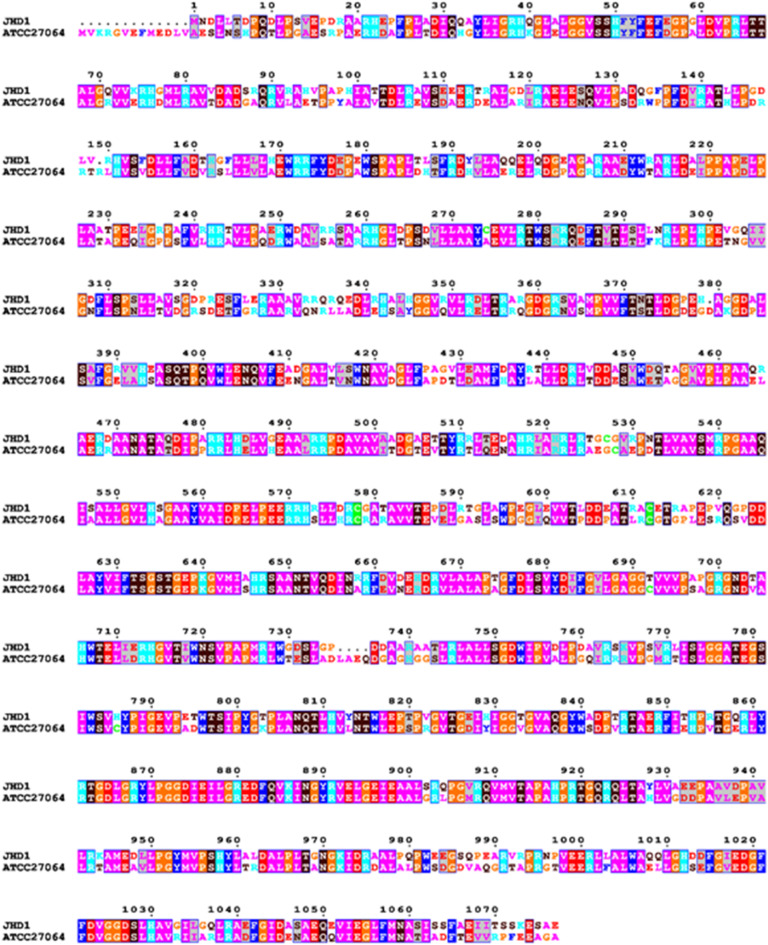

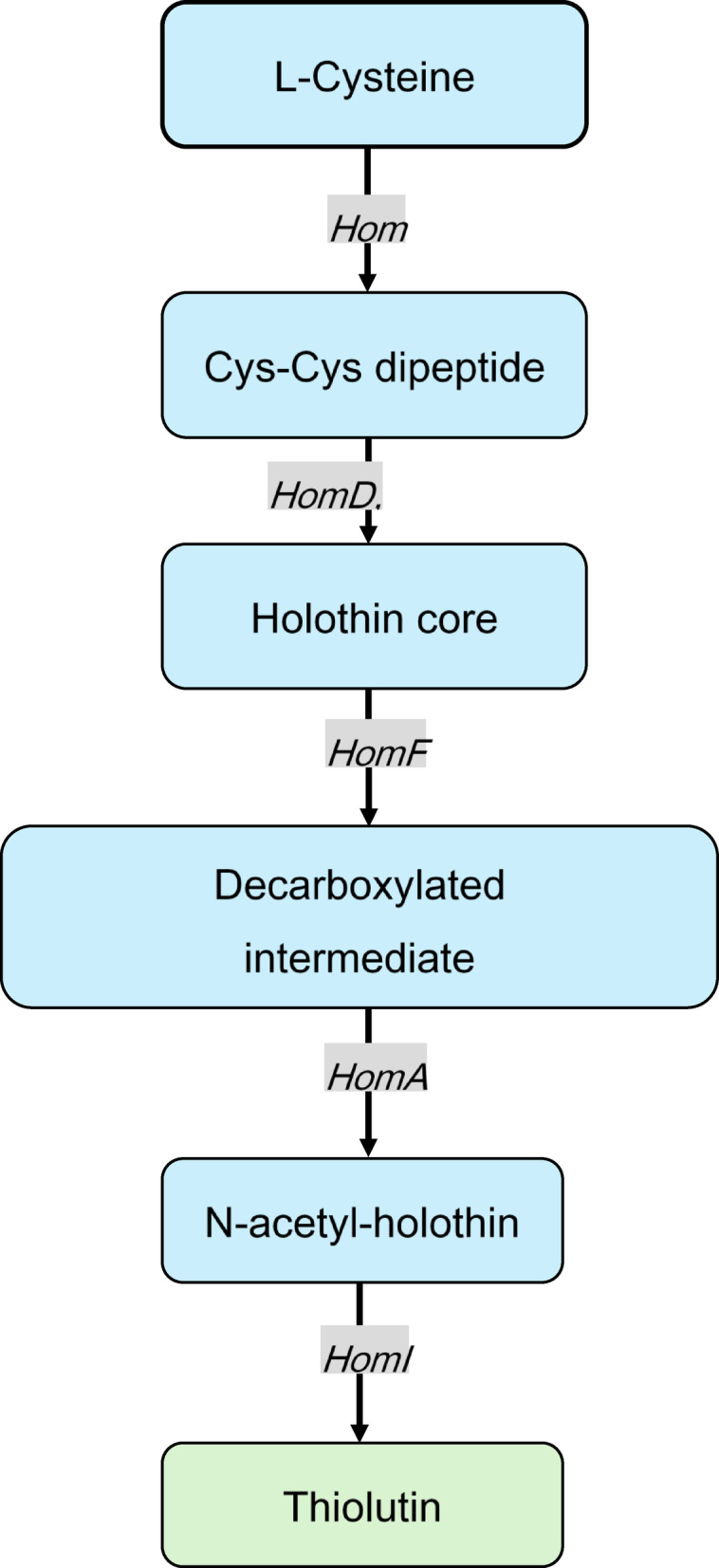

Pairwise amino acid sequence alignment revealed 68.46% sequence identity and 78.87% similarity between the two proteins (Fig. 4), demonstrating significant conservation of this essential biosynthetic enzyme across different Streptomyces species. The alignment showed particularly high conservation throughout the protein sequence, with extensive stretches of identical and similar residues spanning the entire length of the 1,077 amino acid protein. This level of sequence conservation supports the functional assignment of HomE in strain JHD1T and confirms the close evolutionary relationship between thiolutin and holomycin biosynthetic pathways. The high similarity is consistent with their shared dithiolopyrrolone scaffold, where both compounds contain the characteristic pyrrolinonodithiole core structure. The observed conservation suggests that the NRPS machinery for dithiolopyrrolone biosynthesis has been well-preserved across marine and terrestrial Streptomyces species, reflecting the fundamental importance of this enzymatic system in secondary metabolite production. Based on the identified gene cluster and existing literature on dithiolopyrrolone biosynthesis28we propose the following thiolutin biosynthetic pathway for strain JHD1T: The pathway begins with L-cysteine activation and dimerization catalyzed by HomE (NRPS), which utilizes its Cy-A-T domain architecture to form a Cys–Cys dipeptide. Core scaffold formation proceeds through oxidative cyclization mediated by HomD (oxidoreductase) and HomB (acyl-CoA dehydrogenase), generating the characteristic pyrrolinonodithiole structure, followed by decarboxylation by HomF to remove carboxyl groups. N-acetylation is then performed by HomA (N-acyltransferase), using acetyl-CoA as a cofactor, to produce the acetylated intermediate. The final disulfide bond formation is catalyzed by HomI (thioredoxin reductase), yielding mature thiolutin. Product release and transport involve HomC (thioesterase) for enzyme complex release and HomH (efflux protein) for cellular export, with HomG (globin) potentially providing oxygen for oxidative steps. This proposed pathway (L-cysteine → Cys–Cys dipeptide → holothin core → N-acetyl-holothin → thiolutin) is consistent with established dithiolopyrrolone biosynthetic mechanisms and is supported by the functional annotation of all identified genes within the cluster (Fig. 5). These findings provide valuable insights into the evolutionary relationship of strain JHD1T’s thiolutin pathway with those of other characterized dithiolopyrrolone producers, supporting both the taxonomic and biosynthetic characterization of this novel marine-derived Streptomyces species.

Fig. 4.

Pairwise sequence alignment of HomE proteins from Streptomyces sp. JHD1T and S. clavuligerus ATCC 27064. High conservation is observed in the central catalytic domains essential for dithiolopyrrolone biosynthesis.

Fig. 5.

Proposed thiolutin biosynthetic pathway in Streptomyces sp. JHD1T. The pathway proceeds through sequential enzymatic steps starting from L-cysteine substrate and culminating in thiolutin production. Gene names indicate the predicted enzymes catalyzing each biosynthetic step based on functional annotation and homology to characterized dithiolopyrrolone pathways.

Structure Elucidation of secondary metabolites isolated from the marine-derived Streptomyces sp. JHD1T

The detection of numerous biosynthetic gene clusters within the genome of strain JHD1T highlights its considerable potential for the production of novel secondary metabolites. This genetic richness suggests that strain JHD1T may serve as a valuable resource in the ongoing search for promising biologically active compounds. Accordingly, the crude extract obtained from the culture broth of strain JHD1T grown in ISP 2 seawater medium was initially evaluated for antimicrobial activity and demonstrated strong inhibitory effects against Bacillus cereus ATCC 11778 and Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 29213. This prompted further fractionation and purification of the extract using various chromatographic methods. Subsequently, the isolated compounds were structurally characterized through spectroscopic analyses.

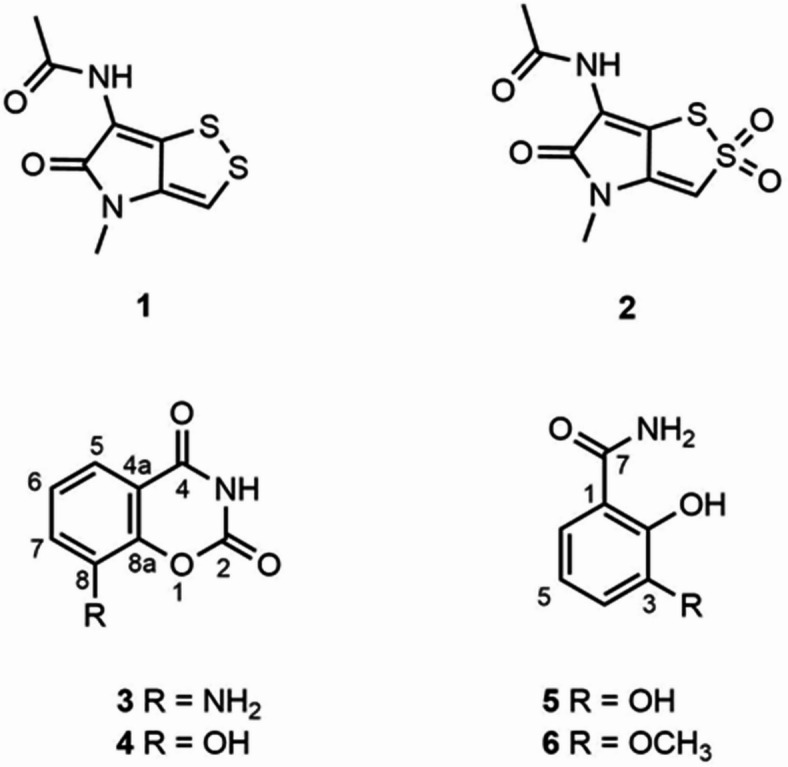

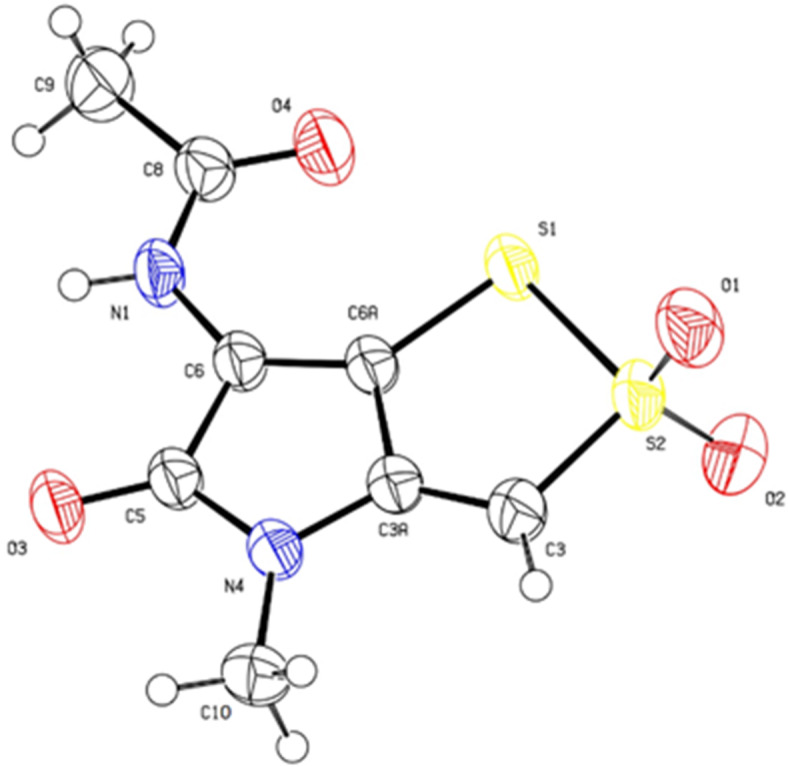

Six compounds (1–6) were isolated from the marine-derived Streptomyces sp. JHD1T. Chemical structures (Fig. 6) were determined by using NMR spectroscopy and identified as thiolutin (1), 2,2-dioxidothiolutin (2), 8-amino-2 H-benz[e][1,3]oxazine-2,4(3 H)-dione (3), benadrostin (4), 2,3-dihydroxybenzamide (5), and 2-hydroxy-3-methoxybenzamide (6). The1H and13C NMR spectral data of compounds 1, 2, 4, and 5 were identical to those reported in the literature32–34 (Tables S7 and S8, Figs. S6, S7, S10, S11, S21, S22, S25, and S26 ). Compound 2 was structurally confirmed for the first time by X-ray crystallographic analysis (Fig. 7). Compounds 3 and 6 were naturally isolated for the first time from Streptomyces sp. and up to date, their1H and13C NMR spectral data have not yet been documented. Herein1, H and13C NMR data together with their physico-chemical data are recorded and the chemical structures were confirmed by HRESIMS data (Figs. S6-S35).

Fig. 6.

Chemical structures of compounds 1–6 isolated from the marine Streptomyces sp. JHD1T.

Fig. 7.

ORTEP Drawing of compound 2 (2,2-dioxidothiolutin) with atomic numbering and 50% displacement ellipsoids.

Compound 3 was obtained as a colorless solid and in HRESIMS data showed a pseudo-molecular ion peak at m/z 177.0303 [M−H]−. The1H and13C NMR spectra were comparable to those of benadrostin (4)35 but the mass spectrum showed even number, suggesting the presence of two nitrogen atoms in the molecule. The evidence pointed out that a hydroxyl group in compound 4 was replaced with an amine group. Moreover, the HMBC correlations from H-5 (δH 7.28) to C-4 (δC 166.3), C-7 (δC 119.6) and C-8a (δC 142.6) indicated an amine group at C-8. Thus, compound 3 is 8-amino-2 H-benz[e][1,3]oxazine-2,4(3 H)dione (Fig. 6).

Likewise1, H and13C NMR spectra of compound 6 were closely related to those of compound 5. HRESIMS spectrum showed 14 mass unit higher than that of compound 5, suggesting the extra methyl group in the molecule. Also, the1H NMR spectrum of compound 6 displayed an additional methoxy group in the molecule. According to the evidence from HMBC correlations, the hydroxyl group at C-3 in compound 5 was replaced with the methoxy group in compound 6. Thus, compound 6 is 2-hydroxy-3-methoxybenzamide (Fig. 6).

Compounds 3 and 6 are initially reported from the marine-derived actinomycetes, Streptomyces sp. JHD1T, while compounds 1, 2, and 4 were previously isolated from Streptomyces spp. 33,35.

Biological activity of the isolated compounds

The isolated compounds were evaluated for a range of biological activities, including antiplasmodial activity against multidrug-resistant Plasmodium falciparum K-1, antitubercular efficacy against Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Ra, antibacterial effects against Bacillus cereus ATCC 11778, Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 29213, and Acinetobacter baumannii, antifungal effect against Candida albicans ATCC 90028, as well as cytotoxicity toward both cancerous cell lines (MCF-7 and NCI–H187) and a non-cancerous cell line (Vero). Thiolutin (1) and 2,3-dihydroxybenzamide (5) showed antimalarial activity with IC50 value of 5.92 and 40.1 µM, respectively. Compound 1 exhibited strong cytotoxicity against both malignant (MCF-7 and NCI-H187) and non-malignant (Vero) cell lines, with IC₅₀ values ranging from 0.35 to 5.61 µM, whereas the other compounds showed only weak cytotoxic effects (Table 4). In addition, compound 1 displayed antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 29213 and Bacillus cereus ATCC 11778, with minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values of 3.13 and 1.56 µg/ml, respectively. In addition, all tested compounds were inactive at the maximum tested concentration (50 µg/ml) in antibacterial and antifungal assays against the Gram-negative bacterium Acinetobacter baumannii and the fungus Candida albicans ATCC 90028. Thiolutin, originally isolated from the culture broth of Streptomyces species, has demonstrated broad-spectrum antibacterial activity against both Gram-positive (S. aureus, MIC 3.125 µg/ml and Mycobacterium bovis, MIC 0.313 µg/ml) and Gram-negative bacteria (Escherichia coli, MIC 6.25 µg/ml), while 2,2-dioxidothiolutin exhibited weak anti-bacterial activity against S. aureus (MIC 50 µg/ml)34. Benadrostin (4) inhibited poly(ADP-ribose)synthetase with IC50 35 mM32 and 2,3-dihydroxybenzamide (5) had antioxidant property34. Numerous Streptomyces strains, including the marine-derived Streptomyces sp. BTBU20218885, S. albus, and S. luteosporeus, have been identified as prolific producers of thiolutin29,33,36,37. Moreover, thiolutin production has also been reported in Saccharothrix algeriensis38. In our study, thiolutin (1) and its oxidized derivative, 2,2-dioxidothiolutin (2), were successfully isolated from the marine-derived Streptomyces sp. JHD1T, consistent with previous reported by Song et al.33. Streptomyces species isolated from marine environments are increasingly recognized as valuable microbial sources for the discovery of novel secondary metabolites, and their importance in natural product research continues to grow. Numerous compounds derived from these marine strains have demonstrated potent antimicrobial activity against a broad range of pathogenic microorganisms. For instance, marinomycins A–D, a unique class of polyene macrolide antibiotics, were originally isolated from marine-derived Streptomyces species. These compounds are notable for their unusual dimeric macrodiolide structures and potent antimicrobial and anticancer activities39. In 2011, Wei et al. reported lobophorins C and D, complex spirotetronate antibiotics, produced by a marine sponge-associated actinomycete strain AZS17. These compounds exhibited a wide range of biological activities, including antibacterial, antifungal, anti-inflammatory, and cytotoxic effects40. Cyclomarins A–C, a distinctive group of cyclic heptapeptides, were isolated from the culture broth of marine-derived Streptomyces sp. CNB-982 and showed anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, and antimalarial activities41. Notably, cyclomarins are biosynthesized by NRPS, which are frequently enriched in marine actinomycete genomes. Surugamides A–E, cyclic octapeptides containing four D-amino acid residues, were isolated from the broth of marine-derived Streptomyces sp. Surugamide A exhibited antibacterial and cytotoxic properties and inhibited autophagy, a promising therapeutic strategy in cancer treatment42,43. Collectively, these findings highlight marine-derived Streptomyces species, including Streptomyces sp. JHD1T, as promising microbial reservoirs for the discovery of novel bioactive compounds with significant potential for biotechnological and pharmaceutical applications.

Table 4.

Biological activity of the isolated compounds from Streptomyces sp. JHD1T.

| Compound | Antimalariala | Anti-Bacillus cereusb | Anti-Staphylococcus aureusb | Cytotoxicityb (IC50, µM) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (IC50, µM) | (MIC, µg/ml) | (MIC, µg/ml) | MCF-7 | NCI-H187 | Vero | |

| 1 | 5.92 | 1.56 | 3.13 | 5.61 | 0.35 | 2.86 |

| 3 | Inactive | Inactive | Inactive | Inactive | Inactive | Inactive |

| 4 | Inactive | Inactive | Inactive | 100.0 | 38.7 | Inactive |

| 5 | 40.06 | Inactive | Inactive | Inactive | 33.8 | Inactive |

| 6 | Inactive | Inactive | Inactive | Inactive | Inactive | Inactive |

| Dihydroartemisinin | 0.0036 | |||||

| Mefloquine | 0.27 | |||||

| Rifampicin | 0.16–0.63 | 0.04–0.56 | ||||

| Ellipticine | 11.8 | 5.93 | ||||

| Doxorubicin | 29.4 | 0.23 | ||||

| Tamoxifen | 43.4 | |||||

| Vancomycin | 1.0–2.0 | 4.0 | ||||

Inactive = % cells inhibition below expected value at the maximum tested concentration.

aMaximum tested concentration was done at 10 µg/ml.

bMaximum tested concentration was done at 50 µg/ml.

Description of Streptomyces marinisediminis sp. nov.

Streptomyces marinisediminis (ma.ri.ni.se.di’mi.nis. L. masc. adj. marinus of or belonging to the sea, marine; L. neut. n. sedimen, -imins sediment; N.L. gen. n. marinisediminis of marine sediment).

Cells are Gram-stain-positive and aerobic. It grows well on ISP 2, ISP 4, and ISP 6. Grows moderately on ISP 5, ISP 7, and nutrient agar. The poorly growth is observed on ISP 3, ISP 6, and Czapek’s sucrose. Light yellowish brown substrate mycelium is observed on ISP 2, ISP 4, and ISP 6 agar. Aerial spore masses is produced on ISP 2, ISP 4, ISP 5, ISP 6, ISP 7, and nutrient agar for 14 days of cultivation. The spiral chain of ovoid-shaped spores with smooth surfaces are detected. Greenish yellow diffusible pigments are found on ISP 2, ISP 4, ISP 5, ISP 6, ISP 7, and nutrient agar. The liquefaction of gelatin, hydrolysis of starch, the production of urease, catalase, oxidase, and milk peptonization are positive. Negative results are observed for the reduction of nitrate, and melanin production. Decomposes hypoxanthine, but not adenine, cellulose, L-tyrosine and xanthine. Utilizes D-cellobiose, dextran, D-fructose, D-glucose, glycerol, D-lactose, D-mannose, D-ribose, salicin, and xylitol; but does not utilize L-arabinose, D-galactose, myo-inositol, inulin, D-mannitol, D-melibiose, D–melezitose, D-raffinose, L-rhamnose, sucrose, D-trehalose, and D-xylose as sole carbon sources. Utilizes L-asparagine, 4-hydroxyproline, L-methionine, L-proline, L-serine, and L-valine; weally utilizes L-arginine, L-histidine, L-threonine, but does not utilize DL-2-aminobutyric acid, L-phenylalanine, and L-cysteine as sole nitrogen sources. The growth temperature is between 20 and 37 °C. Maximum NaCl for growth is 10% (w/v). The pH range for growth is 6–8. Cell wall peptidoglycan contains LL-diaminopimelic acid. The major menaquinones are MK-9(H8), MK-9(H6), and MK-9(H4), while MK-9(H2) is minor component. Glucose, galactose, and ribose, are detected as whole-cell sugars. The phospholipid profile contains diphosphatidylglycerol, phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylglycerol, phosphatidylinositol, phosphatidylinositol mannoside, two unidentified phospholipids. The major fatty acids (> 10%) are anteiso-C15:0, iso-C16:0, and anteiso-C17:0. The DNA G + C content of the type strain is 74.7%. The type strain, JHD1T (= TBRC 15653T = NBRC 115639T), is an actinomycete isolated from marine sediment collected from Chonburi province, Thailand. The GenBank accession number for the 16S rRNA gene sequence of strain JHD1T is OM755759. The whole-genome shotgun project has been deposited at GenBank under the accession JAPKFL000000000.

Conclusions

This study reports the identification of a novel species within the genus Streptomyces and its associated bioactive secondary metabolites. Streptomyces sp. JHD1T was taxonomically characterized using a polyphasic approach, including genome-based analyses, leading to its designation as a new species for which the name Streptomyces marinisediminis sp. nov. is proposed.

This strain, JHD1T, was found to encode a rich biosynthetic repertoire for synthesizing diverse secondary metabolites, mainly through PKS and NRPS pathways, well-known engines for generating bioactive natural products. The crude extract obtained from the culture broth of S. marinisediminis sp. nov. exhibited notable biological activity, enabling the isolation of several secondary metabolites: thiolutin (1), 2,2-dioxidothiolutin (2), 8-amino-2 H-benz[e][1,3]oxazine-2,4(3 H)-dione (3), benadrostin (4), 2,3-dihydroxybenzamide (5), and 2-hydroxy-3-methoxybenzamide (6). X-ray crystallography was employed in this study to confirm, for the first time, the structure of 2,2-dioxidothiolutin (2). Among these, thiolutin, benadrostin, and 2,3-dihydroxybenzamide exhibited a broad spectrum of biological activities, including antimalarial effects, antimicrobial activity against Gram-positive pathogens, and cytotoxicity against human cancer cell lines. These findings highlight Streptomyces marinisediminis sp. nov. as a promising microbial resource, and its metabolites as candidates for further development in biotechnological and pharmaceutical applications.

Experimental procedures

Isolation, cultivation, and preservation of Streptomyces sp. JHD1T

Streptomyces sp. JHD1T was isolated from marine sediment collected from Chonburi province, Thailand (12°52’54.3”N100°52’54.0”E). The marine sediment sample was air-dried at 30 ˚C for 3 days and heated at 100 ˚C for 45 min. The sample was serial diluted (1000-fold) to 10− 3 with 0.01% sterile SDS in seawater and spread onto modified starch-casein nitrate seawater agar containing 10 g soluble starch, 1 g sodium caseinate, 0.5 g KH2PO4, 0.5 g MgSO4 and 18 g agar in 1 L seawater, pH 8.3, supplemented with antibiotics suggested by Thawai et al.44. After 21 days of incubation at 30 ˚C, a yellowish-brown colony of Streptomyces sp. JHD1T was picked and purified on yeast extract-malt extract seawater agar. The pure culture was maintained in glycerol solution (20%, v/v) at − 80 ˚C for short-term preservation or lyophilized for long-term preservation.

Polyphasic taxonomic characterizations

Morphological, cultural, physiological, and biochemical characteristics

To analyze the morphological characteristics, 21-day-old cultures of Streptomyces sp. JHD1T were examined using scanning electron microscopy (JSM-6610 LV; JEOL). Cultural traits were assessed by cultivating the strain on International Streptomyces Project (ISP) media 2–747 (from Difco) for 14 days at 30 °C. The coloration of aerial and substrate mycelia, along with diffusible pigments, was recorded using the ISCC-NBS color charts46. Growth range tests were conducted in ISP 2 broth over 14 days, evaluating temperature tolerance (10–50 °C), NaCl concentration tolerance (0–10% w/v), and pH range (4–12, in increments of 1 unit). Various phenotypic characteristics were examined following established procedures, including tests for the utilization of individual nitrogen sources, decomposition of insoluble compounds (adenine, hypoxanthine, xanthine, tyrosine, and cellulose), starch hydrolysis, nitrate reduction, milk peptonization, and gelatin liquefaction, based on methods by Arai47Williams and Cross48and Gordon et al.49. Carbon source utilization (1% w/v) was determined using the protocol described by Supong et al.50. For comparative purposes, reference strains S. alkaliterrae OF1T and S. chumphonensis KK1-2T were cultivated under identical conditions. All media used for testing phenotypic characteristics were prepared with seawater instead of distilled water.

Chemotaxonomic analyses

Chemotaxonomic characterization was performed using freeze-dried cells harvested from cultures grown in ISP 2 seawater broth on a rotary shaker at 200 r.p.m. and 30 °C for 7 days. The diaminopimelic acid isomer, presence of reducing sugars in cell hydrolysates, and the type of menaquinones were identified following established protocols by Hasegawa et al.51Komagata and Suzuki52Minnikin et al.53and Collins et al.54respectively. To examine the polar lipid profile of Streptomyces sp. JHD1T, lipids were extracted from dried cells and analyzed according to the method of Minnikin et al.55 The cellular fatty acid composition was determined using gas chromatography (Agilent model 6890), following the guidelines provided by the Microbial Identification System (MIDI)56,57.

Genome-based taxonomy and genomic analysis for secondary metabolite production

Genomic DNA for PCR amplification and whole-genome sequencing was extracted following the method of Tamaoka58. Amplification of the 16S rRNA gene was performed using primers 9 F and 1541R59 under conditions described by Kittiwongwattana et al.60. Sequence similarity of the 16S rRNA gene from Streptomyces sp. JHD1T was assessed using the EzBioCloud server61. For phylogenetic analysis, the 16S rRNA gene sequence of Streptomyces sp. JHD1T and those of closely related Streptomyces type strains retrieved from the EzBioCloud database were used to construct phylogenetic trees in MEGA X62. Three tree-building methods, neighbor-joining63maximum-parsimony64and maximum-likelihood65were employed. The confidence of tree topology was evaluated through bootstrap analysis with 1000 replicates66. Whole-genome sequencing was conducted at Chulalongkorn University, Thailand, using the Illumina MiSeq platform (2 × 200 bp paired-end reads). Genome annotation was performed using the NCBI Prokaryotic Genome Annotation Pipeline (PGAP). Genomic similarity metrics, ANIm, AAI, and dDDH, were calculated using JSpecies67the AAI calculator from the Kostas Lab68and the Genome-to-Genome Distance Calculator (GGDC 2.1; BLAST + method)69, respectively. A high-resolution species tree was generated using the autoMLST pipeline (https://automlst.ziemertlab.com)70. The resulting tree was reconstructed using the maximum-likelihood algorithm in MEGA X, with Nocardia uniformis NBRC 13702T (GCF_001613345) serving as an outgroup. To further confirm the taxonomic placement of Streptomyces sp. JHD1T, phylogenomic analysis was performed using TYGS (https://tygs.dsmz.de)71. Secondary metabolite biosynthetic potential was explored using antiSMASH version 7.072. Analyses included KnownClusterBlast, ActiveSiteFinder, ClusterBlast, ClusterPfam, and SubClusterBlast modules. Additionally, BGCs were manually examined in relation to the chemical structure of the compound isolated from Streptomyces sp. JHD1T.

Gene prediction and in Silico NRPS domain analysis

The draft genome sequence of Streptomyces sp. JHD1T was annotated using Bakta v1.10.473 with default parameters to identify protein-coding regions essential for downstream functional characterization. The protein sequences were analyzed for nonribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS) domains with a focus on cyclization (Cy), adenylation (A), and thiolation (T) domain architectures using InterPro74.

Comparative analysis of HomE protein sequences

HomE protein sequences from Streptomyces sp. JHD1T and S. clavuligerus ATCC 27064 were aligned using Clustal omega75 with default parameters, and the alignment was visualized using ESPript 3.076. For quantitative comparison, pairwise global alignment was performed using EMBOSS Needle77 with default parameters to calculate sequence identity and similarity percentages. This analysis assessed the evolutionary relationship between the thiolutin biosynthetic machinery of our marine-derived strain and the characterized dithiolopyrrolone pathway from S. clavuligerus.

General chemical experimental procedures

FT-IR spectra were measured on a Bruker ALPHA spectrometer. UV spectra were performed in MeOH (HPLC-grade from Duksan) on a V-730 UV-Visible spectrophotometer, JASCO. Optical rotations were measured on a JASCO P-2000 digital polarimeter. NMR spectra were recorded either on a Bruker Avance III™ HD 500 MHz spectrometer or Bruker Avance III™ HD 400 MHz NMR spectrometer using a deuterated solvent as an internal standard, such as CD3OD, CDCl3, DMSO-d6 (from Cambridge Isotope Laboratiories, Inc.). HRESIMS data were obtained from Bruker MicrOTOF spectrometer. Column chromatography was performed on Sephadex LH-20 (from GE Healthcare) column using 100% MeOH as an eluent. HPLC was performed on a Dionex-Ultimate 3000 series equipped with a binary pump, an autosampler, and diode array detector. Preparative HPLC was performed on either a Sunfire C18 OBD column from Waters (particle size 10 µm, diam. 19 mm × 250 mm) or a Sunfire C18 OBD column from Waters (particle size 5 µm, diam. 19 mm × 150 mm) at a flow rate of 10 mL/min and at the detection wavelength of 210 nm.

Large scale culture and isolation of secondary metabolites

Streptomyces sp. JHD1T was grown on ISP 2 seawater agar at 30 °C for 4 days. The stock culture was inoculated into 250 ml Erlenmeyer flasks, containing 150 ml of seed medium (ISP 2 seawater broth, comprising (w/v) 0.4% dextrose, 1.0% malt extract, and 0.4% yeast extract in distilled water, pH 6.5). The seed culture of Streptomyces sp. JHD1T was cultivated on a rotary shaker (200 rpm) at 30 °C for 4 days. Then, the seed culture (20 flasks) was transferred into 80 × 1 L Erlenmeyer flasks, which each contained 250 ml of ISP 2 seawater broth, pH 6.5. The production culture (20 L) was cultivated for 14 days at 30 °C on rotary shakers (160 rpm). Then the whole culture was extracted with an equal volume of EtOAc (from Duksan) three times and EtOAc was dried over anhydrous Na2SO4 (from Fisher Chemical). EtOAc was then evaporated to dryness to yield brown gum (2.3 g), which was triturated with MeOH (from Duksan) to give a solid (1.4 g) and filtrate (0.91 g). The filtrate was passed through a Sephadex LH20 column (4.5 cm × 40 cm), eluted with 100% MeOH, and 40–50 mL fractions were collected. Fractions were analyzed by HPLC and then combined based on HPLC analyses to give four main fractions (F1-F4). F1 and F4 were discarded due to no compound of interest. The second fraction (F2, 0.13 g) was purified by a preparative HPLC, using a SunFire C18 column (diam 19 mm × 150 mm), eluted with a linear gradient system of 5% − 30% CH3CN in water over 20 min to yield compounds 5 (tR 11.3 min, 18.1 mg), 4 (tR 13.4 min, 93.7 mg), 6 (tR 15.5 min, 99.2 mg), and 1 (tR 16.8 min, 8.6 mg). The third fraction (F3, 0.46 g) was purified by a preparative HPLC, using a SunFire C18 column (diam 19 mm × 250 mm), eluted with the same linear gradient system as for F2 to afford compound 5 (tR 21.8 min, 24.0 mg).

The solid (1.4 g) was purified by a preparative HPLC, using a SunFire C18 column (diam 19 mm × 250 mm), eluted with a step gradient system of 5% − 35% CH3CN in water over 20 min, 35% CH3CN in water 2 min, 55% − 100% CH3CN in water over 3 min, and 100% CH3CN for 10 min, to furnish 3 (tR 14.7 min, 30.7 mg), 4 (tR 18.4 min, 13.1 mg), 6 (tR 20.6 min, 10.7 mg), 1 (tR 21.8 min, 0.13 g), and 2 (tR 24.9 min, 10.9 mg).

2,2-Dioxidothiolutin (2)

Orange prisms (from MeOH / H2O); HRESIMS m/z 282.9813 [M + Na]+ (calcd for C8H8 N2NaO4S2, 282.9818).

Single X-ray diffraction measurement was performed on a Bruker D8 venture equipped with Cu Ka as the radiation source at 273 K, mounted on Cu in Parabar 10,312. The data was reduced and refined by using SAINT (V8 40B). The structure was solved by using Olex2 program. All non-hydrogen atoms were refined anisotropically. All hydrogen atoms were included in calculated positions with isotropic thermal parameters which were 1.2 and 1.5 times the equivalent isotropic thermal parameters of their parent atoms. All hydrogen atoms attached to N atom were located in the different fourier map.

X-ray data of 2 : C8H8O3.454S2⋅ C8H8O3.748S2, Mr = 507.77, Triclinic, dimensions: 0.05 × 0.05 × 0.05 mm3space group P1; a = 8.3690(5) Å; b = 10.8542(7) Å; c = 12.1457(7) Å; α = 82.214(2)°; β = 73.847(2)°; γ = 75.547(2)°; V = 1019.19(11) Å3; Z = 2; T = 273 K; λ(Cu-Kα) = 1.54178 Å; µ(Cu-Kα) = 4.75 mm− 1; ρcalc = 1.655 g.cm− 3; reflections collected/independent : 35,528/3883 (Rint = 0.033); final R indices [I > 2σ (I)]: R1 = 0.0371, wR2 = 0.1051; final R indices for all data : R1 = 0.0379, wR2 = 0.1056. Crystallographic data have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC) under the reference number CCDC2296168. The data can be obtained free of charge at www.ccdc.cam.ac.ul/conts/retrieving.html [or from CCDC, 12 Union Road, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, UK; fax: +44(0)1223-336033; email: deposit@ccdc.cam.ac.uk]. The cif file is given as supplementary information.

8-Amino-2 H-benz[e][1,3]oxazine-2,4(3 H)dione (3)

Colorless solid; IR (νmax, cm− 1) 3430, 1705, 1644, 1631, 1587, 1544, 1489, 1417, 1391, 1357, 1301, 1194, 1018, and 749;1H (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) 7.13 (1 H, t, J = 7.7 Hz, 6-H), 7.15 (1 H, d, J = 7.9 Hz, 7-H), 7.28 (1 H, dd, J = 6.6, 2.7 Hz, 5-H), 8.06 (2 H, NH), 10.38 (1 H, NH);13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) 116.0 (5-C), 118.3 (4a-C), 119.6 (7-C), 124.5 (6-C), 142.6 (8a-C), 144.8 (8-C), 159.7 (2-C), 166.3 (4-C); HRESIMS m/z 177.0303 [M − H]− (calcd. for C8H5N2O3, 177.0306).

2-Hydroxy-3-methoxybenzamide (6)

Colorless solid; IR (νmax, cm− 1) 3420, 3213, 1665, 1463, 1452, 1439, 1420, 1377, 1245, 1059, 746, and 715;1H (400 MHz, CD3OD) 3.87 (3 H, s, 3-OCH3), 6.84 (1 H, t, J = 8.1 Hz, 5-H), 7.11 (1 H, dd, J = 8.0, 1.3 Hz, 4-H), 7.39 (1 H, dd, J = 8.2, 1.4 Hz, 6-H);13C NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD) 56.7 (3-OCH3), 116.0 (4-C), 116.6 (1-C), 119.6 (5-CH), 121.1 (6-C), 142.6 (6-CH), 149.9 (3-C), 151.5 (2-C), 173.5 (7-C); HRESIMS m/z 166.0508 [M − H]− (calcd. for C8H8NO3, 166.0510).

Biological activity tests

Antimalarial assay against Plasmodium falciparum (K-1, multi-drug resistant strain) was performed by using the microculture radioisotope technique78. Dihydroartemisinin and mefloquine were used as positive controls. Antibacterial activity against Bacillus cereus ATCC 11778, Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 29213 and Acinetobacter baumannii was determined by the optical density microplate assay79,80. Vancomycin and rifampicin were used as positive controls for Gram-positive bacteria and rifampicin and erythronmycin were used as positive controls for Gram-negative bacteria. Cytotoxicity against Vero cells was done by using the green fluorescent protein microplate assay (GFPMA)81. Ellipticine was used as a positive control. Cytotoxicity against MCF-7 (human breast cancer, ATCC HTC-22) and NCI-H187 (human small-cell lung cancer, ATCC CRL-5804) cell lines and antifungal activity against C. albicans ATCC 90028 were evaluated by using the resazurin microplate assay (REMA)82. Amphotericin B was used as the positive control for anti-C. albicans. Tamoxifen and doxorubicin were used as the positive controls for anti-MCF-7 activity. Doxorubicin and ellipticine were used as positive controls for anti-NCI-H187 activity. IC50 value was reported for the concentration that inhibits 50% of tested cells in accordance with dose-response curve, which is plotting between compound concentrations and % inhibition. Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) showed the concentration that could inhibit 90% growth of bacteria. Maximum concentration of all samples is done at 50 µg/ml for all tests, except for antimalarial activity (at 10 µg/ml). 0.5% DMSO was used as negative control.

Accession number of Streptomyces sp. JHD1T

The GenBank accession number for the complete 16S rRNA gene sequence of Streptomyces sp. JHD1T is OM755759. The Whole Genome Shotgun projects for Streptomyces sp. JHD1T has been deposited at GenBank under the accession JAPKFL000000000. The strain is deposited in the Thailand Bioresource Research Center (TBRC) and NITE Biological Resource Center (NBRC) for code numbers TBRC 15653T and NBRC 115639T, respectively (Figs. S36, S37).

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by King Mongkut’s Institute of Technology Ladkrabang (KMITL) [2566-02-05-010]. We thank the Actinobacterial Research Unit (ARU), School of Science, King Mongkut’s Institute of Technology Ladkrabang, for laboratory support. PP also thanks the NSTDA Characterization and Testing Service Center (NCTC) for X-ray analysis. The authors gratefully acknowledge Prof. (Emeritus) Aharon Oren (The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Jerusalem, Israel) for his valuable help on nomenclature aspects.

Abbreviations

- ANI

Average nucleotide identity

- AAI

Average amino-acid identity

- dDDH

Digital DNA-DNA hybridization

- DAP

Diaminopimelic acid

- DSM

German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures GmnH

- EtOAc

Ethyl acetate

- FT-IR

Fourier transformation infrared spectroscopy

- GC

Gas chromatography

- ISP

International Streptomyces Project

- GFPMA

Green fluorescent protein microplate assay

- MeOH

Methanol

- MS

Mass spectrometry

- REMA

Resazurin-based microplate assay

- NMR

Nuclear magnetic resonance

- NRPS

Non-ribosomal peptide synthetase

- BGCs

Biosynthetic gene clusters

- T1PKS

Type I polyketide synthase

- T2PKS

Type II polyketide synthase

- T3PKS

Type III polyketide synthase

- TBRC

Thailand Bioresource Research Center

- NBRC

NITE Biological Resource Center

Author contributions

R. P., P. F., P. P., C. I., M. Y., C. S.: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft. Y-W. H., Y. Q., and S. T.: Writing – review & editing. C. T.: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available on the NCBI website and with the following accession codes at the NCBI database: Streptomyces sp. JHD1T: OM755759 and JAPKFL000000000.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Koblížek, M. & Komárek, J. Microalgae as a source of novel industrial products: bioactive compounds and biocatalysts. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol.33, 93–101. 10.1016/j.copbio.2015.01.007 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bull, A. T., Stach, J. E. & Ward, A. C. Marine actinomycetes: A new frontier for natural products discovery. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 87, 67–81. 10.1007/s10482-004-5351-3 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dinos, G., Pappas, P. & Actinomycin, D. A historical overview of its discovery, mechanism of action, and therapeutic use. Pharmacol. Ther.174, 69–81. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2017.01.007 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sarker, S. D., Nahar, L. & Virginiamycin An antibiotic and its therapeutic applications. Antibiotics: Methods Protocols. 1, 139–150. 10.1007/978-1-59745-102-7_9 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pan, C., Hassan, S., Su., Ishaq, M., Yan, S. & Jin, H. Marine actinomycetes: a hidden treasure trove for antibacterial discovery. Front. Mar. Sci.12, 1558320. 10.3389/fmars.2025.1558320 (2025). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shigeno, S. et al. New polycyclic tetramate macrolactams with antimycobacterial activity produced by marine-derived Streptomyces sp. KKMA-0239. J. Antibiot.77, 265–271. 10.1038/s41429-024-00710-w (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee, S. et al. Deoxyvasicinone with Anti-Melanogenic activity from Marine-derived Streptomyces sp. CNQ-617. Mar. Drugs. 20, 155. 10.3390/md20020155 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ibrahim, W. M. et al. Exploring the antimicrobial, antiviral, antioxidant, and antitumor potentials of marine Streptomyces tunisiensis W4MT573222 pigment isolated from Abu-Qir sediments, Egypt. Microb. Cell. Fact.22, 94. 10.1186/s12934-023-02106-1 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ngamcharungchit, C., Chaimusik, N., Panbangred, W., Euanorasetr, J. & Intra, B. Bioactive metabolites from terrestrial and marine actinomycetes. Molecules28, 5915. 10.3390/molecules28155915 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pridham, T. G., Hesseltine, C. W. & Benedict, R. G. A guide for the classification of streptomycetes according to selected groups; placement of strains in morphological sections. Appl. Microbiol.6, 52–79 (1958). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim, M., Oh, H. S., Park, S. C. & Chun, J. Towards a taxonomic coherence between average nucleotide identity and 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity for species demarcation of prokaryotes. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol.64, 346–351 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Richter, M. & Rosselló-Móra, R. Shifting the genomic gold standard for the prokaryotic species definition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 106, 19126–19131 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goris, J. et al. DNA-DNA hybridization values and their relationship to whole-genome sequence similarities. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol.57, 81–91 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Funabashi, M., Funa, N. & Horinouchi, S. Phenolic lipids synthesized by type III polyketide synthase confer penicillin resistance on Streptomyces griseus. J. Biol. Chem.283, 13983–13991. 10.1074/jbc.M710461200 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kodani, S. et al. The SapB morphogen is a lantibiotic-like peptide derived from the product of the developmental gene ramS in Streptomyces coelicolor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 101, 11448-53 (2004). 10.1073/pnas.0404220101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Becerril, A. et al. Uncovering production of specialized metabolites by Streptomyces argillaceus: activation of cryptic biosynthesis gene clusters using nutritional and genetic approaches. PLoS One. 13, e0198145. 10.1371/journal.pone.0198145 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Álvarez-Álvarez, R. et al. Molecular genetics of naringenin biosynthesis, a typical plant secondary metabolite produced by Streptomyces clavuligerus. Microb. Cell. Fact.14, 178. 10.1186/s12934-015-0373-7 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li, W., Khullar, A., Chou, S., Sacramo, A. & Gerratana, B. Biosynthesis of sibiromycin, a potent antitumor antibiotic. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.75, 2869–2878. 10.1128/AEM.02326-08 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bentley, S. D. et al. Complete genome sequence of the model actinomycete Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Nature417, 141–147. 10.1038/417141a (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ziemert, N. et al. Diversity and evolution of secondary metabolism in the marine actinomycete genus salinispora. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 111, E1130–E1139. 10.1073/pnas.1324161111 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhu, J. et al. Identification and catalytic characterization of a nonribosomal peptide synthetase-like (NRPS-like) enzyme involved in the biosynthesis of echosides from streptomyces sp. LZ35. Gene546, 352–358. 10.1016/j.gene.2014.05.053 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suroto, D. A., Kitani, S., Arai, M., Ikeda, H. & Nihira, T. Characterization of the biosynthetic gene cluster for cryptic Phthoxazolin A in Streptomyces avermitilis. PLoS One. 13, e0190973. 10.1371/journal.pone.0190973 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pait, I. G. U. et al. Discovery of a new diol-containing polyketide by heterologous expression of a silent biosynthetic gene cluster from Streptomyces lavendulae FRI-5. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol.45, 77–87. 10.1007/s10295-017-1997-x (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herisse, M. et al. Discovery and biosynthesis of the cytotoxic polyene terpenomycin in human pathogenic Nocardia. ACS Chem. Biol.18, 1872–1879. 10.1021/acschembio.3c00311 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Erwin, G. S., Heikkinen, J., Halimaa, P. & Haber, C. L. Streptomyces Lasalocidi sp. Nov. (formerly ‘Streptomyces lasaliensis’), an actinomycete isolated from soil which produces the polyether antibiotic lasalocid. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol.70, 3076–3083 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou, W. et al. The isolation of pyrroloformamide congeners and characterization of their biosynthetic gene cluster. J. Nat. Prod.83, 202–209. 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.9b00321 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saker, S. et al. Identification and characterization of the biosynthetic gene cluster of thiolutin, a tumor angiogenesis inhibitor, in Saccharothrix algeriensis NRRL B-24137. PLoS One. 9, e109920. 10.1371/journal.pone.0109920 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang, S. et al. Identification and heterologous expression of the biosynthetic gene cluster for holomycin produced by Streptomyces clavuligerus. Process. Biochem.46, 811–816. 10.1016/j.procbio.2010.11.024 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li, B., Wever, W. J., Walsh, C. T. & Bowers, A. A. Dithiolopyrrolones: biosynthesis, synthesis, and activity of a unique class of disulfide-containing antibiotics. Nat. Prod. Rep.31, 905–923. 10.1039/c3np70106a (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li, B. & Walsh, C. T. Identification of the gene cluster for the dithiolopyrrolone antibiotic holomycin in Streptomyces clavuligerus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 107, 19731-5 (2010). 10.1073/pnas.1014140107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Qin, Z., Huang, S., Yu, Y. & Deng, H. Dithiolopyrrolone natural products: isolation, synthesis and biosynthesis. Mar. Drugs. 11, 3970–3997. 10.3390/md11103970 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aoyagi, T. et al. Benadrostin, new inhibitor of poly(ADP-ribose) synthetase, produced by actinomycetes. I. Taxonomy, production, isolation, physico-chemical properties and biological activities. J. Antibiot.41, 1009–1014. 10.7164/antibiotics.41.1009 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Song, F. et al. Unique cyclized Thiolopyrrolones from the marine-derived Streptomyces sp. BTBU20218885. Mar. Drugs. 20, 20030214. 10.3390/md20030214 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sugiyama, Y. & Hirota, A. New potent DPPH radical scavengers from a marine-derived actinomycete strain USF-TC31. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem.73, 2731–2734. 10.1271/bbb.90636 (2009). PubMed PMID: 19966460; eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yoshida, S., Naganawa, H., Aoyagi, T., Takeuchi, T. & Umezawa, H. Benadrostin, new inhibitor of Poly (ADP-ribose) synthetase, produced by actinomycetes. II. Structure determination. J. Antibiot.41, 1015–1018 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tanner, F. W., Means, J. A., Davisson, J. W. & English, A. R. Thiolutin, an antibiotic produced by certain strains of Streptomyces albus. Proceedings of the 118th Meeting of the American Chemical Society; Chicago, IL, USA. (1950).

- 37.Zhai, Y. et al. Identification of an unusual type II thioesterase in the dithiolopyrrolone antibiotics biosynthetic pathway. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun.473, 329–335. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.03.105 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bouras, N., Mathieu, F., Sabaou, N. & Lebrihi, A. Effect of amino acids containing sulfur on dithiolopyrrolone antibiotic productions by Saccharothrix algeriensis NRRL B-24137. J. Appl. Microbiol.100, 390–397. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2005.02762.x (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kwon, H. C., Kauffman, C. A., Jensen, P. R. & Fenical, W. Marinomycins A–D, antitumor-antibiotics of a new structure class from a marine actinomycete of the genus Streptomyces. JACS128, 1622–1632 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wei, R. B., Xi, T., Li, J., Wang, P. & Zhang, Y. Lobophorins C and D, new Kijanimicin derivatives from a marine sponge-associated actinomycetal strain AZS17. Mar. Drugs. 9, 359–368 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Renner, M. K. et al. Cyclomarins A–C, new anti-inflammatory Cyclic peptides produced by a marine bacterium (Actinomycetales). JACS121, 11273–11276 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Matsuda, K. et al. The revised structure of the Cyclic octapeptide Surugamide A. Chem Pharm. Bull. (Tokyo). 67, 476–480. 10.1248/cpb.c19-00002 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Takada, K. et al. Surugamides A-E, Cyclic octapeptides with four D-amino acid residues, from a marine Streptomyces sp.: LC-MS-aided inspection of partial hydrolysates for the distinction of D- and L-amino acid residues in the sequence. J. Org. Chem.78, 6746–6750. 10.1021/jo400708u (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thawai, C., Rungjindamai, N., Klanbut, K. & Tanasupawat, S. Nocardia xestospongiae sp. nov., isolated from a marine sponge in the Andaman sea. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol.67, 1451–1456 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shirling, E. B. & Gottlieb, D. Methods for characterization of Streptomyces species. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol.16, 313–340 (1966). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kelly, K. L. Inter-Society Color Council – National Bureau of Standard Color Name Charts Illustrated with Centroid Colors (US Government Printing Office, 1964).

- 47.Arai, T. Culture media for actinomycetes. Tokyo: the society for actinomycetes.Japan. 1–20 (1975).

- 48.Williams, S. T. & Cross, T. Actinomycetes. In: (ed Booth, C.) Methods in Microbiology, vol. 4. Academic, London, 295–334 (1971). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gordon, R. E., Barnett, D. A., Handerhan, J. E. & Pang, C. H. N. Nocardia coeliaca, Nocardia autotrophica, and the nocardia strain. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol.24, 54–63 (1974). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Supong, K., Suriyachadkun, C., Pittayakhajonwut, P., Suwanborirux, K. & Thawai, C. Micromonospora spongicola sp. nov., an actinomycete isolated from a marine sponge in the Gulf of Thailand. J. Antibiot.66, 505–509 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hasegawa, T., Takizawa, M. & Tanida, S. A rapid analysis for chemical grouping of aerobic actinomycetes. J. Gen. Appl. Microbiol.29, 319–322 (1983). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Komagata, K. & Suzuki, K. I. Lipid and cell-wall analysis in bacterial systematics. Methods Microbiol.19, 161–207 (1987). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Minnikin, D. E. et al. An integrated procedure for the extraction of bacterial isoprenoid Quinones and Polar lipids. J. Microbiol. Methods. 2, 233–241 (1984). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Collins, M. D., Pirouz, T., Goodfellow, M. & Minnikin, D. E. Distribution of menaquinones in actinomycetes and corynebacteria. J. Gen. Microbiol.100, 221–230 (1977). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Minnikin, D. E., Patel, P. V., Alshamaony, L. & Goodfellow, M. Polar lipid composition in the classification of Nocardia and related bacteria. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol.27, 104–117 (1977). [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sasser, M. Identification of Bacteria by Gas Chromatography of Cellular Fatty Acids. MIDI Technical Note 101 (Newark, 1990).

- 57.Kämpfer, P. & Kroppenstedt, R. M. Numerical analysis of fatty acid patterns of Coryneform bacteria and related taxa. Can. J. Microbiol.42, 989–1005 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tamaoka, J. Determination of DNA base composition. In: (eds Goodfellow, M. & O’Donnell, A. G.) Chemical Methods in Prokaryotic Systematics. Chichester, Wiley, 463–470 (1994).

- 59.Weisburg, W. G., Barns, S. M., Pelletier, D. A. & Lane, D. J. 16S ribosomal DNA amplification for phylogenetic study. J. Bacteriol.173, 697–703 (1992). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kittiwongwattana, C. et al. Micromonospora oryzae sp. nov., isolated from roots of upland rice. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol.65, 3818–3823 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yoon, S. H. et al. Introducing ezbiocloud: A taxonomically united database of 16S rRNA and whole genome assemblies. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol.67, 1613–1617 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kumar, S., Stecher, G., Li, M., Knyaz, C. & Tamura, K. MEGA X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol.35, 1547–1549 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Saitou, N. & Nei, M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol.4, 406–425 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fitch, W. M. Toward defining the course of evolution: minimum change for a species tree topology. Sys Zoo. 20, 406–416 (1971). [Google Scholar]

- 65.Felsenstein, J. Evolutionary trees from DNA sequences: a maximum likelihood approach. J. Mol. Evol.17, 368–376 (1981). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Felsenstein, J. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution39, 783–791 (1985). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Richter, M., Rosselló-Móra, R., Glöckner, F. O. & Peplies, J. JSpeciesWS: a web server for prokaryotic species circumscription based on pairwise genome comparison. Bioinformatics32, 929–931 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rodriguez-R, L. M. & Konstantinidis, K. T. Bypassing cultivation to identify bacterial species. Microbe Mag. 9, 111–118 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 69.Meier-Kolthoff, J. P., Auch, A. F., Klenk, H. P. & Göker, M. Genome sequence-based species delimitation with confidence intervals and improved distance functions. BMC Bioinform.14, 60–73 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Alanjary, M., Steinke, K. & Ziemert, N. AutoMLST: an automated web server for generating multi-locus species trees highlighting natural product potential. Nucleic Acids Res.47, 276–282 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Meier-Kolthoff, J. P. & Göker, M. TYGS is an automated high throughput platform for state-of-the-art genome-based taxonomy. Nat. Commun.10, 2182 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Blin, K. et al. AntiSMASH bacterial version 7 beta (2023). https://antismash.secondarymetabolites.org

- 73.Schwengers, O. et al. Bakta: rapid and standardized annotation of bacterial genomes via alignment-free sequence identification. Microb. Genom. 7, 000685. 10.1099/mgen.0.000685 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Blum, M. et al. InterPro: the protein sequence classification resource in 2025. Nucleic Acids Res.53, D444–D456. 10.1093/nar/gkae1082 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sievers, F. & G Higgins, D. Clustal Omega. Curr. Protoc. Bioinf.48, 3131–31316. 10.1002/0471250953.bi0313s48 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Robert, X. & Gouet, P. Deciphering key features in protein structures with the new endscript server. Nucleic Acids Res.42, W320–W324. 10.1093/nar/gku316 (2014). (Web Server issue). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sarachu, M. & Colet, M. wEMBOSS: a web interface for EMBOSS. Bioinformatics21, 540–541. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti031 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Desjardins, R. E., Canfield, C. J., Haynes, J. D. & Chulay, J. D. Quantitative assessment of antimalarial activity in vitro by a semiautomated microdilution technique. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.16, 710–718 (1979). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wayne, P. A. M07-A7, Methods for Dilution Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria that Grow Aerobically; Approved Standard 7th edn (Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, 2006a).

- 80.Wayne, P. A. M100-S16, Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; 16th informational supplement, Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. (2006).

- 81.Changsen, C., Franzblau, S. G. & Palittapongarnpim, P. Improved green fluorescent protein reporter gene-based microplate screening for antituberculosis compounds by utilizing an acetamidase promoter. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.47, 3682–3687 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.O’Brien, J., Wilson, I., Orton, T. & Pognan, F. Investigation of the Alamar blue (resazurin) fluorescent dye for the assessment of mammalian cell cytotoxicity. Eur. J. Biochem.267, 5421–5426 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available on the NCBI website and with the following accession codes at the NCBI database: Streptomyces sp. JHD1T: OM755759 and JAPKFL000000000.