Abstract

Background

Alertness plays a crucial role in the completion of important tasks. However, application of existing methods for evaluating alertness is limited due to issues such as high subjectivity, practice effect, susceptibility to interference, and complexity in data collection. Currently, there is an urgent need for a rapid, quantifiable, and easily implementable alertness assessment method.

Methods

Twelve optical stimulation frequencies ranged from 4 to 48 Hz were chosen to induce brainwave entrainment (BWE) for 30 s, respectively, in 40 subjects. Electroencephalogram (EEG) were recorded at the prefrontal pole electrodes Fpz, Fp1, and Fp2. Karolinska Sleepiness Scale, psychomotor vigilance test and β band power in resting EEG, were used to evaluate the alertness level before and after optical stimulation-induced BWE. The correlation between nine EEG features during the BWE and different alertness states were analyzed. Next, machine learning models including support vector machine, Naive Bayes and logistic regression were employed to conduct integrated analysis on the EEG features with significant differences.

Results

We found that BWE intensity, β band power, and γ band power exhibit significant differences across different states of alertness. The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) of individual features for classifying alertness states was between 0.62–0.83. To further improve classification efficacy, these three features were used as input parameters in machine learning models. We found that Naive Bayes model showed the best classification efficacy in 30 Hz optical stimulation, with AUC reaching 0.90, an average accuracy of 0.90, an average sensitivity of 0.89, and an average specificity of 0.90. Meanwhile, we observed that the subjects’ alertness levels did not change significantly before and after optical stimulation-induced BWE.

Conclusions

Our study demonstrated that the use of machine learning to integrate EEG features during 30 s optical stimulation-induced BWE showed promising classification capabilities for alertness states. It provided a rapid, quantifiable, and easily implementable alertness assessment option.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12938-025-01422-4.

Keywords: Alertness, Optical stimulation, Brainwave entrainment, Electroencephalogram, Machine learning, Karolinska Sleepiness Scale, Psychomotor vigilance test

Introduction

Alertness refers to a state of being awake, conscious, attentive, and prepared to take action or respond [1]. In this state, an individual is not only awake, but also capable of mounting an adequate response to irregular and occasional stimuli [2]. It describes a level of cortical activation and the ability to react to external stimuli. Maintaining a certain level of alertness is crucial for the smooth completion of important tasks. For instance, doctors performing high-precision surgeries, drivers of special vehicles, dispatchers in transportation sectors such as railways, aviation, and maritime shipping, as well as athletes engaged in speed sports all rely on a high level of alertness.

Existing alertness assessment methods primarily include the following, but they generally have certain limitations. The first is subjective assessment of the wakeful or arousal state, which includes self-reported scales based on subjective descriptions. The most commonly used scales are Karolinska Sleepiness Scale (KSS) [3–6], Epworth Sleepiness Scale [7, 8], and Stanford Sleepiness Scale [9], among others. The advantages of these methods lie in their simplicity and speed. However, they require high compliance from subjects and are strongly subjective. The second approach involves the evaluation of physiological indicators based on the collection of physiological signals, such as electroencephalography (EEG) [10], electrooculography [11], and electromyography [12]. These methods are highly sensitive but can also be susceptible to interference from other physiological processes, such as emotional responses like excitement, agitation, or fear. Another widely applied method is performance-based assessment through responses to objective stimuli, such as Go/No-Go test [13–15], N-back test [16–18], and psychomotor vigilance test (PVT) [19–21]. These tests can directly reflect the level of alertness through reaction time (RT), but they may exhibit practice effects and require high cognitive engagement, which can exert negative pressure on the state of alertness itself. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) [22] and functional near-infrared spectroscopy [23] both indirectly reflect neural activity by detecting hemodynamic changes coupled with neural activity and can also indicate alertness levels to some extent. These methods involve complex equipment and lengthy data collection times, but due to their strong spatial specificity, they are more commonly used in research focusing on the structural aspects of the brain related to alertness.

Current methods for evaluating alertness have not been widely applied in practice due to their inherent limitations. The state of development in alertness assessment falls short of meeting the objective demands of real-world applications, necessitating the development of a new type of alertness evaluation method that is convenient for practical use and high in accuracy. There is a close relationship between flickering light and alertness. At a high state of alertness, the level of cortical arousal is increased, and the visual system becomes more sensitive to flickering light, allowing individuals to perceive a higher frequency of flickering. Conversely, when alertness is reduced, the frequency of flickering that can be perceived by individuals decreases. This change in the frequency that an individual can perceive is known as the critical flicker fusion frequency [24], an important indicator for measuring the visual system’s perception of flickering light. It has been used for a simple assessment of cognitive ability and alertness in diving operations [25]. Flickering light, entering the cerebral cortex through the visual system, can synchronize the firing frequency of neurons, a phenomenon known as brainwave entrainment (BWE) [26, 27]. This can produce a characteristic signal with the same frequency as the stimulus, known as the steady-state visual evoked potential (SSVEP), which has been widely used in brain–computer interface research [28–30]. It has also been applied in studies related to other cognitive functions, such as fatigue [31], cognition [32], attention [33], and working memory [34]. However, to our knowledge, BWE has not been used to assess alertness. In our previous study, we found that during prolonged optical stimulation, the BWE correlates highly with alertness-related EEG parameters α/β [35]. Therefore, optical stimulation-induced BWE holds the potential to become a physiological indicator for evaluating alertness.

In this study, we divided 40 subjects into two different alertness states—high alertness and low alertness—using KSS scale and validated the grouping with PVT and β band power in resting EEG. High refresh rate monitors were used to generate flickering videos at different frequencies to induce BWE. We extracted EEG features that exhibited significant differences under varying states of alertness and further applied machine learning classification to integrate the analysis of these features. Subsequently, we conducted KSS, PVT, and EEG evaluations on the subjects after the entrainment measurement to analyze whether BWE had an impact on their alertness states. Our aim is to establish a method for evaluating alertness based on the classification of optical stimulation-induced BWE features using machine learning models.

Results

Comparison of existing alertness assessment methods

In this study, we categorized 40 participants into different alertness states based on their KSS scores [36]. Participants with scores ranging from 1 to 4 were classified as the high alertness group, while those with scores between 5 and 9 were classified as the low alertness group. Meanwhile, PVT was used as a performance measure of alertness, with results shown in Table 1. The average RT in the high alertness group was significantly shorter, at 210.74 ± 16.67 ms, compared to 221.79 ± 12.14 ms in the low alertness group (p = 0.023). The slowest 10% RTs in the high alertness group was also significantly shorter, at 290.57 ± 29.62 ms, compared to 315.17 ± 33.52 ms in the low alertness group (p = 0.023). The median RTs in the high alertness group was significantly shorter, at 199.42 ± 15.84 ms, compared to 209.77 ± 12.08 ms in the low alertness group (p = 0.028). We extracted the resting β band power as a physiological evaluation metric, and the resting β band power in the high alertness group was significantly higher, at 23.03 ± 16.58 μV2, compared to 13.67 ± 11.22 μV2 in the low alertness group (p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Comparison of PVT and resting-state EEG results between high alertness and low alertness groups before optical stimulation-induced BWE measurement

| High alertness | Low alertness | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| KSS | |||

| Score | 1–4 (n = 18) | 5–9 (n = 22) | |

| PVT | |||

| Mean RT (ms) | 210.74 ± 16.67 | 221.79 ± 12.14 | 0.023* |

| Slowest 10% RT (ms) | 290.57 ± 29.62 | 315.17 ± 33.52 | 0.023* |

| Median RT (ms) | 199.42 ± 15.84 | 209.77 ± 12.08 | 0.028* |

| EEG | |||

| β power (μV2) | 23.03 ± 16.58 | 13.67 ± 11.22 | < 0.001*** |

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. n represents the number of the subjects

Analysis of correlation between individual EEG features and alertness states

We extracted nine features from the subjects during each 30 s optical stimulation at different frequencies for analysis, including BWE intensity, θ band power, α band power, β band power, γ band power, β band center frequency, γ band center frequency, range entropy, and sample entropy. These features were compared between high and low alertness states using Mann–Whitney U-test, and P-values are calculated and shown in appendix Table. S1-3. Three features that showed significant differences across alertness states were identified, which were BWE intensity, β band power, and γ band power, as shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Comparison of three optical-induced stimulation entrainment features in different alertness states at twelve frequencies, respectively. a BWE. b β band power. C γ band power. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01

To evaluate the discriminative ability of individual feature parameters for different alertness states, we analyzed the classification capability of the three different features using AUC. As shown in Fig. 2, the discriminative ability of individual features based on a single electrode for different alertness states is suboptimal. The AUC for classifying different states of alertness, based on BWE intensity, β band power, and γ band power, ranges from 0.62 to 0.83.

Fig. 2.

Area under the ROC curve for the classification of different alertness states using individual EEG features as characteristic parameters. a BWE. b β band power. C γ band power

Feature fusion analysis of individual features through machine learning models

To further increase the classification efficiency, we used three features that demonstrated significant differences across alertness states, which are BWE intensity, β band power, and γ band power, as input parameters in machine learning models. We chose three machine learning models, including SVM, Naive Bayes, and logistic regression, to classify the alertness states. The selected evaluation metrics for the model included accuracy by Eq. 2, sensitivity by Eq. 3, specificity by Eq. 4, and AUC.

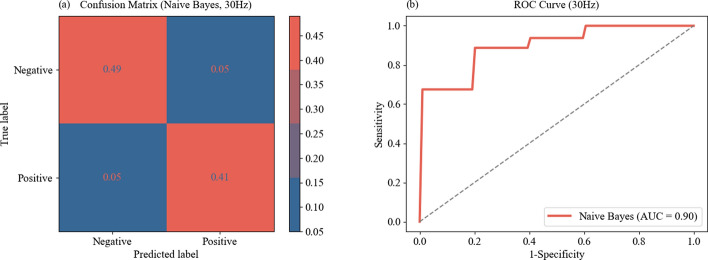

As shown in Fig. 3, the results indicated that with 30 Hz optical stimulation, the Naive Bayes model demonstrated the optimal classification performance with the highest AUC, reaching 0.90, which surpasses the highest AUC of 0.87 for the SVM model at 15 Hz optical stimulation and the highest AUC of 0.88 for the logistic regression model at 30 Hz optical stimulation. Concurrently, with 30 Hz optical stimulation, the Naive Bayes model achieved an average accuracy of 0.90, an average sensitivity of 0.89, and an average specificity of 0.90.

Fig. 3.

Classification of different alertness states using machine learning models that integrated three individual features, displaying a accuracy rate, b sensitivity, C specificity, d area under the ROC curve. SVM: support vector machine. NB Naive Bayes. LR logistic regression

The confusion matrix and ROC curve for classifying high alertness versus low alertness at 30 Hz optical stimulation are presented in Fig. 4. Figure 4a shows the confusion matrix for the classification of high and low alertness states using Naive Bayes model under 30 Hz optical stimulation. The x-axis represented the predicted labels by the Naive Bayes model, categorized as negative class and positive class. The y-axis represented the true labels, also divided into negative class and positive class. In the top-left corner (predicted low alertness, actual low alertness): 0.49, indicating that 90.7% (0.49 / (0.49 + 0.05) ≈ 0.907) of participants with actual low alertness were correctly predicted as such. In the top-right corner (predicted high alertness, actual low alertness): 0.05, indicating that 9.3% (0.05 / (0.49 + 0.05) ≈ 0.093) of participants with actual low alertness were incorrectly predicted as having high alertness. In the bottom-left corner (predicted low alertness, actual high alertness): 0.05, indicating that 10.9% (0.05 / (0.05 + 0.41) ≈ 0.109) of participants with actual high alertness were incorrectly predicted as having low alertness. In the bottom-right corner (predicted high alertness, actual high alertness): 0.41, indicating that 89.1% (0.41 / (0.05 + 0.41) ≈ 0.891) of participants with actual high alertness were correctly predicted as such.

Fig. 4.

Analysis of the model fusion difference characteristics for different states of alertness under 30 Hz optical stimulation: a confusion matrix. b ROC curve

Figure 4b presents the ROC curve for the classification of high and low alertness states using the Naive Bayes model under 30 Hz optical stimulation. The x-axis denoted 1 minus specificity, which corresponds to the false positive rate. The y-axis represented sensitivity, which was the true positive rate. The AUC value was 0.90, indicating that the Naive Bayes model demonstrates a good discriminative ability between different alertness states. These results suggested that at the frequency of 30 Hz optical stimulation, the Naive Bayes model was able to accurately distinguish between high alertness and low alertness states.

Comparison of the alertness states before and after entrainment

We used the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for paired comparisons of the KSS scores and resting-state EEG power before and after optical stimulation, and the paired sample t-test for comparing PVT results before and after optical stimulation. As shown in Table 2, the P-values for KSS scores and resting-state EEG power tests were both greater than 0.05, indicating that the optical stimulation did not significantly affect the subjects’ alertness state. However, PVT results showed a decrease in reaction time after optical stimulation compared to before, suggesting an improvement in response speed. This may be attributed to the practice effects [37] observed in short-term repeated testing (lasting minutes to hours) with cognitive tests based on reaction time, compared to long-term repeated testing with traditional neuropsychological assessments, which lead to improved test performance. This practice effect was also presented in other types of cognitive tests, such as those assessing verbal ability, quantitative ability, and analytical ability [38]. This was one of the reasons why we aimed to develop a more objective method for evaluating alertness.

Table 2.

Comparison of subjective KSS, PVT, and resting-state EEG results before and after optical stimulation-induced BWE measurement

| Before BWE | After BWE | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| KSS | |||

| Score | 4.93 ± 1.70 | 4.65 ± 1.78 | 0.383 |

| PVT | |||

| Mean RT (ms) | 216.83 ± 15.56 | 202.83 ± 17.42 | < 0.001*** |

| Slowest 10% RT (ms) | 304.09 ± 34.53 | 287.93 ± 40.13 | 0.028* |

| Median RT (ms) | 205.11 ± 15.01 | 192.03 ± 15.87 | < 0.001*** |

| EEG | |||

| β power (μV2) | 15.58 ± 8.85 | 13.07 ± 5.85 | 0.101 |

Discussion

In this study, we used the widely applied KSS scale to divide 40 subjects into high and low alertness groups, and verified the grouping using the proportion of resting EEG β band power and PVT performance. We employed 12 optical stimulations with different frequencies to induce BWE and simultaneously collected EEG data from the Fp1, Fpz, and Fp2 electrodes. We analyzed the EEG characteristics during the optical stimulation-induced BWE process and extracted three significantly different features under different alertness states, which are BWE intensity, β band power, and γ band power. We further plotted ROC curves and found that the classification efficiency of individual features for alertness states was not satisfied. Therefore, we further used the three features as input parameters and applied machine learning classification for integrated analysis. We found that under 30 Hz optical stimulation, the Naive Bayes model had the best classification efficiency, with the maximum area under the ROC curve reaching 0.90. It had an average accuracy of 0.90, an average sensitivity of 0.89, and an average specificity of 0.90. We also conducted KSS test of alertness levels, resting EEG collection, and PVT tests before and after optical stimulation, and found that optical stimulation did not change the subjects’ alertness levels significantly.

The KSS scale is commonly used to assess participants’ subjective alertness levels. PVT is a widely used alertness assessment tool designed to measure reaction time and attention, while EEG provides a non-invasive method for monitoring brain electrical activity. In our work, we used the KSS scale to group alertness levels, and then employed the PVT and EEG β wave power to validate these groupings. The purpose was to evaluate and validate the alertness state from multiple dimensions, including subjective and objective perspectives. We aimed for a more comprehensive understanding of the participants’ alertness state. The results of this study indicate that the measurements from KSS, PVT, and EEG β wave power were consistent across different alertness states. Previous studies have shown that, when evaluating alertness, there is consistency between KSS scores and PVT performance [39–42], as well as between KSS scores and EEG β wave power [43, 44], which aligns with the findings of this study. This supports the validity and reliability of using the KSS scale as a grouping tool in alertness research in this study.

This study aims to preliminarily explore the relationship between optical stimulation-induced BWE and alertness levels. Alertness state itself is influenced by various demographic factors, such as age, gender, and occupational background. Among different populations, there are significant variations in the data measured by existing alertness assessment methods. Research has found that during sleep disorders, subjects of different genders exhibit notable differences in the PVT [45]. Additionally, there are gender differences in light sensitivity, with males showing a stronger response to light stimuli, demonstrating higher brightness perception and faster reaction times [46]. Age is also a critical factor affecting alertness, as alertness tends to decline with increasing age [47]. Furthermore, occupation influences alertness levels. Studies indicate that sleep duration and the number of consecutive night shifts are associated with changes in alertness among physicians. This suggests that occupation-related night shift schedules and working hours may impact the alertness of doctors [48].

Therefore, to preliminarily investigate whether optical stimulation-induced BWE can evaluate different alertness states, it is essential to ensure that the baseline data of the study population are as consistent as possible. Consequently, the participant group in this study is relatively homogeneous. However, in the future, its applicability and stability under diverse populations and environmental conditions require further validation. It is necessary to include participants of different ages, genders, and occupational backgrounds, as well as conduct experiments under varying cultural and environmental conditions, to test the model’s generalizability.

We chose to study the electroencephalography signals from the frontal lobe, as neural activity within the frontal lobe was closely associated with cognitive processes such as attention and alertness. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies have identified the frontoparietal network (FPN) as playing a crucial role in maintaining alertness [49]. Lesions to white matter tracts such as the superior longitudinal fasciculus (SLF) and the frontal aslant tract (FAT) within the frontal lobe can lead to impairments in alertness [50]. Additionally, in PVT, increased functional connectivity between the superior prefrontal gyrus and middle frontal gyrus was positively correlated with prolonged response time [51]. EEG studies have also shown that recording the spectral dynamics of δ and α activity from four anterior frontal electrodes (AF8, FP2, FP1, and AF7) can be used to assess the driver’s level of alertness [52]. Therefore, we recorded EEG signals from three electrodes (Fp1, Fpz, Fp2) for analysis. Furthermore, the lack of hair on the forehead facilitated the use of patch-type EEG electrodes for testing, reducing the complexity and preparation time of measurements.

We found that BWE in the frontal lobe showed significant differences in different alertness states. It is partly because the frontal lobe was a crucial center for alertness-related functions; on the other hand, entrainment was considered to have high temporal resolution and cognitive assessment capabilities [53]. This technique had already been used to mark targets and is widely applied in visual attention research [54–56]. Moreover, it had been confirmed that changes in the amplitude of frontal lobe SSVEP were highly correlated with the maintenance time of working memory tasks, reflecting changes in the brain’s information processing patterns [57], as well as variations in emotional arousal [58], anxiety [59], and other factors [60, 61]. In our previous study, we found that the BWE intensity at 40 Hz in frontal lobe was inverse proportionally to the α/β ratio during a one-hour optical stimulation, which indicated fatigue level of the subjects [35]. In this study, we observed significant differences in BWE under different alertness states. This finding indicated that the brain’s capacity to regulate its oscillatory activities may be a crucial element in maintaining an optimal state of alertness. These results contributed to our understanding of the neural mechanisms of attention control and alertness, emphasizing the role of brainwave entrainment as a potential biomarker for cognitive states, although its specific mechanisms required further exploration.

Meanwhile, we conducted an analysis of various parameters during optical stimulation across different states of alertness, including the power of each EEG frequency band, centroid frequency, relative centroid frequency, range entropy, and sample entropy. We observed significant differences in β band power and γ band power between different states of alertness. This finding provides a new perspective for understanding the functional regulatory mechanisms of the brain under varying levels of wakefulness. In the low alertness state, we noted that during optical stimulation, both β band power and γ band power were relatively low, indicating that the brain’s information processing capacity was limited, and cognitive functions may be impaired. β waves were typically associated with attentional focus and cognitive control, and their decreased power reflects a weakening of these brain functions [62]. Concurrently, the reduced activity of γ waves also reflected a limitation in the level of attentional control and the ability to temporarily store and manipulate information in working memory [63], further illustrating the decline in cognitive functions in the low alertness state. In contrast, during the high alertness state, β band power significantly increased, and γ band power also rose during photic stimulation, suggesting that the brain is in an ideal cognitive activation state. The enhancement of β waves indicated that the individual is cognitively active, with greater capacity for information processing and integration [64], while the increase in γ waves contributed to improved attention, memory, and other cognitive functions [65]. This change in brain wave power revealed that the brain is able to perform cognitive tasks more effectively in the high alertness state. The differences in β band power and γ band power during optical stimulation across different alertness states suggested their potential to serve as biomarkers for alertness states.

Upon calculating the AUC for the classification of different alertness states based on individual features, the AUC values for these features ranged from 0.62 to 0.83, suggesting moderate in distinguishing between alertness states. This may be due to the limitation of a single feature in evaluating alertness, as individual EEG features might not adequately reflect the complexity and multidimensional nature of alertness. In contrast, a strategy of multi-feature fusion can integrate information across multiple dimensions, thereby enhancing the predictive power and robustness of the alertness assessment model. Therefore, we selected three EEG parameters that showed statistically significant differences in different alertness states during optical stimulation: BWE intensity, β band power, and γ band power. We then used three traditional machine learning models—SVM, Naive Bayes, and logistic regression—to perform integrated analysis and classification of different alertness states, achieving better classification efficiency. The results showed that at the 30 Hz frequency, the Naive Bayes model had the largest AUC at 0.90, with an average accuracy of 0.90, average sensitivity of 0.89, and average specificity of 0.90. This indicates that under 30 Hz frequency stimulation, the model is able to accurately distinguish between high alertness and low alertness.

The Naive Bayes model is a classification algorithm based on Bayes’ theorem, characterized by its ease of learning and understanding, high efficiency, good robustness, and high accuracy in handling classification problems [66]. It has been widely applied in various fields, particularly in text classification [67], medical diagnosis [68], and recommendation systems [69]. Through Bayes’ theorem, the model can weigh the probability distribution of each feature, making full use of the information from other features even if some features have limited information, thus improving the model’s generalization ability. Therefore, in our study, we used the BWE intensity, β band power, and γ band power as input parameters and obtained good classification performance through the Naive Bayes model. Our research shows that using machine learning-based classification of BWE feature parameters induced by optical stimulation to evaluate alertness is highly feasible. In the future, it is necessary to explore more diverse parameters and construct more reasonable classification models to achieve better classification results.

The alertness assessment method based on BWE has promising applications. It is possible to use a wireless Bluetooth three-lead EEG device for EEG data collection. In scenarios where people work in front of displays, optical stimulation of specific frequency can be achieved through the screen background or via LED strips around the screen, enabling real-time measurement of alertness in job positions. This allows us to promptly identify changes in alertness in positions requiring high alertness, such as air and railway traffic controllers, security video monitoring, and other tasks, thus preventing work errors caused by human factors. Wearable display devices can also be used for pre-task alertness evaluation in activities like special driving, high-altitude work, and sports competitions. Compared to existing alertness assessment methods, the optical stimulation-induced BWE alertness assessment is more objective and provides a more comprehensive reflection of the intrinsic components of alertness. It is a highly promising method for alertness assessment. Certainly, future research should delve into the relationship between alertness states and optical-induced brainwave entrainment related electroencephalographic parameters under various demographic variables such as gender, age, occupation, and educational level. This will facilitate the development of a more widely applicable alertness assessment protocol.

Conclusion

In this study, we analyzed the EEG features during 30 s optical stimulation at 12 frequencies and found three features that exhibited significant differences across high and low alertness, which are BWE intensity, β band power, and γ band power. However, AUC for classifying alertness states using these individual features was between 0.62–0.83. To further improve classification efficacy, we employed machine learning classification method to integrate these three features as input parameters. We found that during 30 Hz optical stimulation, the Naive Bayes model showed the best classification efficacy, with a maximum AUC reaching 0.90. The average accuracy of the Naive Bayes model was 0.90, the average sensitivity was 0.89, and the average specificity was 0.90. We also evaluated the alertness states before and after the optical stimulation via KSS, PVT and EEG β band power during resting state. We found that the optical stimulation did not change the subjects’ alertness states significantly. Our result indicated that optical stimulation-induced BWE is a promising and innovative method for assessing alertness, overcoming the limitations of existing methods such as subjectivity, susceptibility to interference, and practice effects. It offered advantages such as short data collection time and portability, and holds strong potential for future applications.

Materials and methods

Subjects

Our study enrolled a total of 40 male subjects, aged between 20 and 30 years, with a mean age of 24.37 ± 0.36 years. All subjects had no history of psychiatric or neurological disorders, drug or alcohol addiction, or traumatic brain injury. Additionally, all subjects had normal vision or vision corrected to normal and reported no sleep disturbances in the three days preceding the experiment and no caffeine intake during that period. Informed written consent was obtained from all subjects. The research was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hainan Hospital of the People’s Liberation Army General Hospital and was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration.

Karolinska Sleepiness Scale

KSS employs a 9-point rating system for questionnaire, where 1 indicates extreme alertness, 2 very alert, 3 alert, 4 quite alert, 5 neither alert nor sleepy, 6 slightly sleepy, 7 sleepy (but no effort to fall asleep), 8 very sleepy (some effort to fall asleep), and 9 extremely sleepy, with an inability to remain awake. This scale is employed to subjectively assess the alertness of subjects. On this scale subjects indicate which level best reflects the psycho-physical sate. Due to its convenience and speed, the KSS has been widely applied by researchers both domestically and internationally in experimental research related to alertness [70–72].

Psychomotor vigilance test

PVT is a computer-based measure of an individual's reaction to specified small changes in a labile environment. Subjects are instructed to respond to a digital signal on a computer terminal by pressing a key. PVT is currently one of widely used methods for evaluating alertness performance and is extensively applied in laboratory research related to alertness [19, 73, 74]. PVT employs a simple visual reaction time (RT) paradigm. In this study, to minimize the impact of the test itself on the subjects’ alertness, we administered a 3-min version of the PVT [75] with stimulus intervals ranging from 1 to 4 s. Mean RTs, fastest 10% of RTs, slowest 10% of RTs, and median RTs were used as performance metrics for alertness assessment. RTs less than 100 ms and greater than 500 ms were considered as error responses.

EEG recording

The EEG signal acquisition equipment used in this study was developed by the Ubiquitous Sensing and Intelligent Systems Laboratory at Lanzhou University [76]. This device is capable of recording up to 8 channels with an EEG sampling rate of 250 Hz. The monitoring electrodes consist of patch-type Ag/AgCl electrodes. Following the international 10–20 System for EEG Electrode Placement, the prefrontal region of the subjects was targeted for EEG signal monitoring. Specifically, the electrode positions included the prefrontal midpoint (Fpz), left prefrontal (Fp1), and right prefrontal (Fp2). Reference electrodes were placed at the bilateral mastoids, which serve as the zero electrical potential point.

Optical stimulation-induced BWE

The optical stimulation protocol was implemented through the inversion of two images, one black and one white. The illuminance of the white image was 400 lx, while the illuminance of the black image was less than 10 lx. The stimulation frequencies chosen were 4 Hz, 5 Hz, 6 Hz, 8 Hz, 10 Hz, 12 Hz, 15 Hz, 20 Hz, 24 Hz, 30 Hz, 40 Hz, and 48 Hz, comprising a total of 12 frequencies. Each frequency was stimulated for 30 s, with a 30-s rest interval in between. The order of frequencies was chosen randomly.

Procedure

The experiment was conducted during two time periods: from 9:00 to 11:00 a.m. and from 1:00 to 3:00 p.m., with all participants volunteering to participate in the study. All experiments were conducted in the same dark room, where the illuminance was less than 5 lx. At the beginning of the experiment, subjects were given a 15-min rest period to get used to the environment. The procedure was as follows: (a) A 3-min PVT. (b) A 1-min subjective alertness measurement was conducted using the KSS questionnaire. (c) The forehead electrode position of the participant was cleaned by physiological saline, then the EEG monitoring equipment was properly fitted to collect 5 min of EEG signal while resting. (d) A 12-min optical stimulation-induced entrainment measurement was conducted. (e) Another 5 min of EEG during resting state was collected. (f) A 1-min KSS questionnaire was then performed. (g) A 3-min PVT was completed. The experimental procedure is shown in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Experimental protocol for alertness assessment by optical stimulation-induced brainwave entrainment through machine learning classification. PVT Psychomotor Vigilance Test. KSS Karolinska Sleepiness Scale. EEG electroencephalogram. BWE brainwave entrainment. SVM support vector machine. NB naive Bayes. LR logistic regression

EEG data analysis

EEG signal preprocessing

Before extracting EEG features, we applied median filtering to remove baseline drift. A bandpass filter with a range of 1 to 125 Hz was used to suppress low-frequency and high-frequency interference, and a notch filter was employed to remove 50 Hz power line noise. To eliminate ocular artifacts from electrooculography (EOG) signals, we employed wavelet decomposition and Kalman filtering techniques [77, 78]. Following the preprocessing of the EEG data, the 30-s raw EEG data were initially segmented into three non-overlapping 10-s windows to mitigate signal fluctuations [79]. Within each 10-s window, the Welch method was further applied to calculate the PSD. In the Welch method, each 10-s segment was divided into 2-s smaller windows, with a 50% overlap for analysis. Finally, the PSDs obtained from the three 10-s windows were averaged to derive a final average PSD. The power within a specified frequency band was calculated by integrating the PSD over that band. We adopted a BWE calculation formula based on power spectral integration, as reported in the literature [35], for subsequent analysis of BWE in this study:

| 1 |

In the formula, and represent the values of EEG power at Hz and Hz, respectively.

Statistical analysis

To ensure the stability of data and enhance the accuracy of subsequent statistical analyses, the median absolute deviation (MAD) method was employed to identify and remove outliers prior to testing. The maximum removal rate was set at 10%, and the detection threshold was 3 times the MAD.

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 26.0 and Python software. Parameters were statistically described using mean ± standard deviation. For parameters that followed a normal distribution, an independent-samples t-test was used to analyze the deviation between two measurement values. For parameters that did not conform to a normal distribution, the Mann–Whitney U-test was employed to assess the differences between the two groups. This test is not dependent on the assumption of data normality, rendering it appropriate for analyzing non-normally distributed data.

Model construction

In practical applications, there is a need for rapid and efficient identification of high and low alertness states. Due to the high computational time cost of complex models and the tendency to overfit on small datasets, this study employs three machine learning models: support vector machine (SVM), Naive Bayes, and logistic regression for the recognition of alertness states. SVM utilized kernel functions to map data into a high-dimensional space, effectively capturing complex patterns and structures; Naive Bayes and logistic regression offered rapid convergence and efficient training, making them suitable for handling binary classification problems on small datasets. These three models exhibited low time complexity on small datasets. This study employs fourfold cross-validation to assess model performance. Given the limited sample size of the small dataset, the use of traditional hold-out methods or single-fold cross-validation could lead to significant random influence on the evaluation results, making it difficult to accurately reflect the model’s generalization ability. In contrast, fourfold cross-validation, by dividing the dataset into four parts, ensured that the model was trained and evaluated on different subsets of data in each training and testing process, thereby effectively reducing the impact of randomness on the evaluation results.

Model evaluation metrics

The selected evaluation metrics for the model include accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and the area under the curve (AUC) of the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Accuracy represents the proportion of the total number of samples correctly predicted by the model to the total number of samples, and it serves as a fundamental indicator for assessing the overall performance of the model. The calculation formula for accuracy is as follows:

| 2 |

where TP refers to the number of positive samples correctly predicted as positive by the model, TN refers to the number of negative samples correctly predicted as negative by the model, FP refers to the number of negative samples incorrectly predicted as positive by the model, and FN refers to the number of positive samples incorrectly predicted as negative by the model.

Sensitivity, also known as the true positive rate (TPR), measures the model’s ability to correctly identify positive samples. The calculation formula is:

| 3 |

Specificity, also known as the true negative rate (TNR), refers to the model’s ability to correctly identify negative samples. The calculation formula is:

| 4 |

The AUC value typically refers to the area under the ROC curve, which is a chart used to assess the performance of classification models. It demonstrates the model’s performance by plotting the true positive rate (TPR) (Eq. 3) against the false positive rate (FPR) at various threshold settings. The calculation formula for FPR is:

| 5 |

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We express our sincere appreciation to all subjects for their valuable contribution to this research.

Abbreviations

- AUC

Area under the curve

- BWE

Brainwave entrainment

- EEG

Electroencephalography

- KSS

Karolinska Sleepiness Scale

- LED

Light emitting diode

- PSD

Power spectral density

- PVT

Psychomotor vigilance test

- RT

Reaction time

- ROC

Receiver operating characteristic

- SPSS

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences

- SSVEP

Steady-state visual evoked potential

- SVM

Support vector machine

Author contributions

Authors YG and YT contributed to the conception and design of the study. YZ conducted the data collection, while SW and HC performed the data analysis. YZ wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. YT refined the structure of the draft. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the Major Science and Technology Project in Hainan Province of China (No. ZDKJ2019012), CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (CIFMS) (2019-I2M-5–061), in part by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2019YFA0706200), in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 62076113).

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study has received approval from the Ethics Committee of the Hainan Hospital of the General Hospital of the People’s Liberation Army (NO. S2024-01–01). Written informed consent was obtained from the subjects.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Yong Zhou, Yizhou Tan have contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Hanshu Cai, Email: hcai@lzu.edu.cn.

Ying Gu, Email: guyinglaser@sina.com, Email: guyinglaser301@163.com.

References

- 1.Gary R, VandenBos. APA dictionary of psychology. 2nd ed. Washington: American Psychological Association; 2007. 10.1037/14646-000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Souman JL, Tinga AM, Te Pas SF, et al. Acute alerting effects of light: a systematic literature review. Behav Brain Res. 2018;337:228–39. 10.1016/j.bbr.2017.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liang J, Wang X, Li S, et al. Study on cognitive behavior and subjective evaluation index of seafarer’s alertness. Int Conf Human-Comput Interact. 2022. 10.1007/978-3-031-06388-6_22. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yan S, Ahmed W, Saeed HA. Alert and on task: decoding how mental alertness and workload influence maritime operators task performance using task network modeling. Cogn Technol Work. 2024;26:1–19. 10.1007/s10111-024-00769-3. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang M, Liu D, Wang Q, et al. Detection of alertness-related EEG signals based on decision fused BP neural network. Biomed Signal Process Control. 2022;74: 103479. 10.1016/j.bspc.2022.103479. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liang J, Yu Y, Zhang L, et al. Feasibility verification of ergonomic design based on alert indicators. Int Conf Human-Comput Interact. 2024. 10.1007/978-3-031-60731-8_4. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tankéré P, Taillard J, Stauffer E, et al. Phenotyping patients treated for obstructive sleep apnea with persistent objective impaired alertness or subjective sleepiness. Sleep Med. 2024;122:221–9. 10.1016/j.sleep.2024.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Philip P. Excessive daytime sleepiness versus sleepiness at the wheel, the need to differentiate global from situational sleepiness to better predict sleep-related accidents. Sleep. 2023;46(11):1–2. 10.1093/sleep/zsad231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smaczny S, Bauder D, Sperber C, et al. Reducing alertness does not affect line bisection bias in neurotypical participants. Exp Brain Res. 2024;242(1):195–204. 10.1007/s00221-023-06738-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bajaj V, Taran S, Khare SK, et al. Feature extraction method for classification of alertness and drowsiness states EEG signals. Appl Acoust. 2020;163: 107224. 10.1016/j.apacoust.2020.107224. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murugan S, Sivakumar PK, Kavitha C, et al. An electro-oculogram (EOG) sensor’s ability to detect driver hypovigilance using machine learning. Sensors. 2023;23(6):2944. 10.3390/s23062944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arjunan S P, Kumar D K. Fractal features based technique to identify subtle forearm movements and to measure alertness using physiological signals (sEMG, EEG). TENCON 2008–2008 IEEE Region 10 Conference. 2008: 10.1109/TENCON.2008.4766797.

- 13.Sánchez-Lacambra M, Sánchez-Cano A, Arcas-Carbonell M. Effects of light on visual function, alertness, and cognitive performance: a computerized test assessment. Appl Sci. 2024;14:6424. 10.3390/app14156424. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li Y, Fang W, Qiu H, et al. The non-visual effects of correlated color temperature on the alertness, cognition, and mood of fatigued individuals during the afternoon. Int J Ind Ergon. 2024;101: 103589. 10.1016/j.ergon.2024.103589. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Popovova J, Mazloum R, Macauda G, et al. Enhanced attention-related alertness following right anterior insular cortex neurofeedback training. IScience. 2024;27(2): 108915. 10.1016/j.isci.2024.108915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steinberg SN, Malins JG, Liu J, et al. Within-individual BOLD signal variability in the N-back task and its associations with vigilance and working memory. Neuropsychologia. 2022;173: 108280. 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2022.108280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Siraji MA, Grant LK, Schaefer A, et al. Effects of daytime exposure to short-wavelength-enriched white light on alertness and cognitive function among moderately sleep-restricted university students. Build Environ. 2024;252: 111245. 10.1016/j.buildenv.2024.111245. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Y, Fang W, Guo B, et al. Morning boost on alertness, cognitive performance and mood with dynamic lighting. Ergon Des. 2022;47:601–8. 10.5494/ahfe1001988. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trotti LM, Saini P, Bremer E, et al. The Psychomotor vigilance Test as a measure of alertness and sleep inertia in people with central disorders of hypersomnolence. J Clin Sleep Med. 2022;8(5):1395–403. 10.5664/jcsm.9884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Plante DT, Hagen EW, Ravelo LA, et al. Impaired neurobehavioral alertness quantified by the psychomotor vigilance task is associated with depression in the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort study. Sleep Med. 2020;67:66–70. 10.1016/j.sleep.2019.11.1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hao C, Li M, Luo W, et al. Dissociation of subjective and objective alertness during prolonged wakefulness. Nat Sci Sleep. 2021;13:923–32. 10.2147/NSS.S312808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jagannathan SR, Bareham CA, Bekinschtein TA. Decreasing alertness modulates perceptual decision-making. J Neurosci. 2022;42(3):454–73. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0182-21.2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Herrmann MJ, Woidich E, Schreppel T, et al. Brain activation for alertness measured with functional near infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS). Psychophysiology. 2008;45(3):480–6. 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2007.00633.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mankowska ND, Marcinkowska AB, Waskow M, et al. Critical flicker fusion frequency: a narrative review. Medicina. 2021;57(10):1096. 10.3390/medicina57101096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Piispanen WW, Lundell RV, Tuominen LJ, et al. Assessment of alertness and cognitive performance of closed circuit rebreather divers with the critical flicker fusion frequency test in arctic diving conditions. Front Physiol. 2021;12: 722915. 10.3389/fphys.2021.722915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Basu S, Banerjee B. Prospect of brainwave entrainment to promote well-being in individuals: a brief review. Psychol Stud. 2020;65(3):296–306. 10.1007/s12646-020-00555-x. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yadav GS, Cidral-Filho FJ, Iyer RB. Using heartfulness meditation and brainwave entrainment to improve teenage mental wellbeing. Front Psychol. 2021;12: 742892. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.742892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu D, Tang F, Li Y, et al. An analysis of deep learning models in SSVEP-based BCI: a survey. Brain Sci. 2023;13(3):483. 10.3390/brainsci13030483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ming G, Pei W, Gao X, et al. A high-performance SSVEP-based BCI using imperceptible flickers. J Neur Eng. 2023;20(1): 016042. 10.1088/1741-2552/acb50e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hong J, Qin X. Signal processing algorithms for SSVEP-based brain computer interface: state-of-the-art and recent developments. J Intell Fuzzy Syst. 2021;40(6):10559–73. 10.3233/JIFS-201280. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Azadi Moghadam M, Maleki A. Fatigue factors and fatigue indices in SSVEP-based brain-computer interfaces: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Human Neurosci. 2023;17:1248474. 10.3389/fnhum.2023.1248474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Khachatryan E, Wittevrongel B, Reinartz M, et al. Cognitive tasks propagate the neural entrainment in response to a visual 40 Hz stimulation in humans. Front Aging Neurosci. 2022;14:1010765. 10.3389/fnagi.2022.1010765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Whitmore N W, Chan S, Zhang J, et al. Improving attention using wearables via haptic and multimodal rhythmic stimuli. Proceedings of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. 2024: 1–14. 10.1145/3613904.3642256

- 34.Reinhart RMG, Nguyen JA. Working memory revived in older adults by synchronizing rhythmic brain circuits. Nat Neurosci. 2019;22(5):820–7. 10.1038/s41593-019-0371-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yizhou T, Zhe L, Yong Z, et al. Study of brainwave entrainment induced by 1-h-long 40-Hz flickering stimulation. IEEE Trans Comput Soc Syst. 2024;99:1–7. 10.1109/TCSS.2024.3374455. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rahman A N M T, Chowdhury M E H, Mahbub Z B, et al. Driver drowsiness detection by heart rate variability (HRV) analysis using machine-learning algorithm[J]. International Conference on Physics in Medicine (ICPM-2020). 2020. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/341510506.

- 37.Alexander C, Paul M, Michael M. The effects of practice on the cognitive test performance of neurologically normal individuals assessed at brief test–retest intervals. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2003;9(3):419–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hausknecht JP, Halpert JA, Di Paolo NT, et al. Retesting in selection: a meta-analysis of coaching and practice effects for tests of cognitive ability. J Appl Psychol. 2007;92(2):373–85. 10.1037/0021-9010.92.2.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Monteiro TG, Skourup C, Zhang H. A task agnostic mental fatigue assessment approach based on EEG frequency bands for demanding maritime operation. IEEE Instrum Meas Mag. 2021;24(4):82–8. 10.1109/MIM.2021.9448258. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hu F, Zhang L, Yang X, et al. EEG-based driver fatigue detection using spatio-temporal fusion network with brain region partitioning strategy. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2024;25(8):9618–30. 10.1109/TITS.2023.3348517. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pelou M, Abi-Saab P, Monseigne T, et al. Neurofeedback to improve wakefulness maintenance ability[C].NEC 2024–5th International Neuroergonomics Conference. 2024. https://inria.hal.science/hal-04721899v1.

- 42.Wang F, Wang H, Fu R, et al. Study on unsafe behavior detection of tower crane drivers in prefabricated building construction. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2025;26(4):4406–17. 10.1109/TITS.2025.3546232. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kaida K, Takahashi M, Åkerstedt T, et al. Validation of the Karolinska sleepiness scale against performance and EEG variables. Clin Neurophysiol. 2006;117(7):1574–81. 10.1016/j.clinph.2006.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Manousakis JE, Mann N, Jeppe KJ, et al. Awareness of sleepiness: temporal dynamics of subjective and objective sleepiness. Psychophysiology. 2021;58(8): e13839. 10.1111/psyp.13839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.de Souza ML, Santos FH, Almeida AP, et al. Sex differences in the cognitive performance in adults: role of impaired sleep. Sleep Sci. 2022;15(01):17–25. 10.5935/1984-0063.20210022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chellappa SL, Steiner R, Oelhafen P, et al. Sex differences in light sensitivity impact on brightness perception, vigilant attention and sleep in humans. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):14215. 10.1038/s41598-017-13973-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Baethge A, Rigotti T. Three-way interactions among interruptions/multitasking demands, occupational age, and alertness: a diary study. Work, Aging Retire. 2015;1(4):393–410. 10.1093/workar/wav014. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Debets MPM, Tummers FHMP, Silkens MEWM, et al. Doctors’ alertness, contentedness and calmness before and after night shifts: a latent profile analysis. Hum Resour Health. 2023;21(1):68. 10.1186/s12960-023-00855-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen X, Hsu CF, Xu D, et al. Loss of frontal regulator of vigilance during sleep inertia: a simultaneous EEG-fMRI study. Hum Brain Mapp. 2020;41(15):4288–98. 10.1002/hbm.25125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kaufmann BC, Cazzoli D, Pastore-Wapp M, et al. Joint impact on attention, alertness and inhibition of lesions at a frontal white matter crossroad. Brain. 2023;146(4):1467–82. 10.1093/brain/awac359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Qi J, Li BZ, Zhang Y, et al. Altered insula-prefrontal functional connectivity correlates to decreased vigilant attention after total sleep deprivation. Sleep Med. 2021;84:187–94. 10.1016/j.sleep.2021.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lin CT, Chuang CH, Huang CS, et al. Real-time assessment of vigilance level using an innovative Mindo4 wireless EEG system 2013. IEEE international symposium on circuits and systems (ISCAS). IEEE. 2013. 10.1109/ISCAS.2013.6572149. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chota S, Bruat A, Van der Stigchel S, et al. SSVEPs reveal dynamic (re-) allocation of spatial attention during maintenance and utilization of visual working memory. J Cogn Neurosci. 2023;36(5):800–14. 10.1101/2023.08.29.555110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.De Lissa P, Caldara R, Nicholls V, et al. In pursuit of visual attention: SSVEP frequency-tagging moving targets. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(8): e0236967. 10.1371/journal.pone.0236967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Reuter EM, Bednark J, Cunnington R. Reliance on visual attention during visuomotor adaptation: an SSVEP study. Exp Brain Res. 2015;233:2041–51. 10.1007/s00221-015-4275-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lee YC, Lin WC, Cherng FY, et al. A visual attention monitor based on steady-state visual evoked potential. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng. 2015;24(3):399–408. 10.1109/TNSRE.2015.2501378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Silberstein RB, Nunez PL, Pipingas A, et al. Steady state visually evoked potential (SSVEP) topography in a graded working memory task. Int J Psychophysiol. 2001;42(2):219–32. 10.1016/s0167-8760(01)00167-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Park S, Kim DW, Han CH, et al. Estimation of emotional arousal changes of a group of individuals during movie screening using steady-state visual-evoked potential. Front Neuroinform. 2021;15: 731236. 10.3389/fninf.2021.731236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gray M, Kemp AH, Silberstein RB, et al. Cortical neurophysiology of anticipatory anxiety: an investigation utilizing steady state probe topography (SSPT). Neuroimage. 2003;20(2):975–86. 10.1016/S1053-8119(03)00401-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Norcia AM, Appelbaum LG, Ales JM, et al. The steady-state visual evoked potential in vision research: a review. J Vision. 2015;15(6):4. 10.1167/15.6.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vialatte FB, Maurice M, Dauwels J, et al. Steady-state visually evoked potentials: focus on essential paradigms and future perspectives. Progress Neurobiol. 2010;90(4):418–38. 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Taheri Gorji H, Wilson N, VanBree J, et al. Using machine learning methods and EEG to discriminate aircraft pilot cognitive workload during flight. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):2507. 10.1038/s41598-023-29647-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Griškova-Bulanova I, Živanović M, Voicikas A, et al. Responses at individual gamma frequencies are related to the processing speed but not the inhibitory control. J Pers Med. 2022;13(1):26. 10.3390/jpm13010026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ibrahim MS, Kamat SR, Shamsuddin S. The role of brain wave activity by electroencephalogram (EEG) in assessing cognitive skills as an indicator for driving fatigue: a review. Malays J Compos Sci Manuf. 2023;11(1):19–31. 10.3793/mjcsm.11.1.1931. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liu C, Han T, Xu Z, et al. Modulating gamma oscillations promotes brain connectivity to improve cognitive impairment. Cereb Cortex. 2022;32(12):2644–56. 10.1093/cercor/bhab371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Martinez-Arroyo M, Sucar L E. Learning an optimal naive Bayes classifier. 18th international conference on pattern recognition (ICPR'06). IEEE. 2006;3: 1236–1239. 10.1109/ICPR.2006.748.

- 67.Dhingra M, Dhabliya D, Dubey M K, et al. A Review on Comparison of Machine Learning Algorithms for Text Classification. 2022 5th International Conference on Contemporary Computing and Informatics (IC3I). IEEE. 2022;1818–1823. 10.1109/IC3I56241.2022.10072502.

- 68.Rismayanti N, Naswin A, Zaky U, et al. Evaluating thresholding-based segmentation and Humoment feature extraction in acute lymphoblastic leukemia classification using Gaussian naive Bayes. Int J Artificial Intell Med Issues. 2023;1(2):74–83. 10.56705/ijaimi.v1i2.99. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rrmoku K, Selimi B, Ahmedi L. Application of trust in recommender systems—utilizing naive Bayes classifier. Computation. 2022;10(1):6. 10.3390/computation10010006. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vanttola P, Härmä M, Viitasalo K, et al. Sleep and alertness in shift work disorder: findings of a field study. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2019;92:523–33. 10.1007/s00420-018-1386-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mahachandra M, Prastawa H, Mufid A. Effect of passenger presence towards driving performance level using kss and cnc indicator. IOP Conf Ser. 2020. 10.1088/1757-899X/909/1/012056. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Putilov AA, Donskaya OG. Calibration of an objective alertness scale. Int J Psychophysiol. 2014;94(1):69–75. 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2014.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bermudez EB, Klerman EB, Czeisler CA, et al. Prediction of vigilant attention and cognitive performance using self-reported alertness, circadian phase, hours since awakening, and accumulated sleep loss. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(3): e0151770. 10.1371/journal.pone.0151770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Thomann J, Baumann CR, Landolt HP, et al. Psychomotor vigilance task demonstrates impaired vigilance in disorders with excessive daytime sleepiness. J Clin Sleep Med. 2014;10(9):1019–24. 10.5664/jcsm.4042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Basner M, Mollicone D, Dinges DF. Validity and sensitivity of a brief psychomotor vigilance test (PVT-B) to total and partial sleep deprivation. Acta Astronaut. 2011;69(11–12):949–59. 10.1016/j.actaastro.2011.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tian F, Zhu L, Shi Q, et al. The three-lead EEG sensor: Introducing an EEG-assisted depression diagnosis system based on ant lion optimization. IEEE Trans Biomed Circ Syst. 2023;17(6):1035–318. 10.1109/TBCAS.2023.3292237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.In MH, Lee SY, Park TS, et al. Ballistocardiogram artifact removal from EEG signals using adaptive filtering of EOG signals. Physiol Meas. 2006;27(11):1227. 10.1088/0967-3334/27/11/014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chen Y, Zhao Q, Hu B, et al. A method of removing ocular artifacts from EEG using discrete wavelet transform and Kalman filtering[C]. 2016 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM). IEEE, 2016: 1485–1492. 10.1109/BIBM.2016.7822742

- 79.Núñez P, Poza J, Gómez C, et al. Characterization of the dynamic behavior of neural activity in Alzheimer’s disease: Exploring the non-stationarity and recurrence structure of EEG resting-state activity. J Neural Eng. 2020;17(1): 016071. 10.1088/1741-2552/ab71e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.