Take Home Message

Neoadjuvant immunotherapy shows promising efficacy and manageable toxicity in muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Recent phase 3 data support its potential to redefine the standard of care, offering new hope, particularly for patients ineligible for cisplatin-based chemotherapy.

Keywords: Bladder cancer, Neoadjuvant, Systematic review, Immunotherapy, Chemotherapy

Abstract

Background and objective

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), alone or with platinum-based chemotherapy, have increasingly been studied as neoadjuvant therapy for muscle-invasive bladder cancer (BC). We sought to evaluate the current evidence about neoadjuvant immunotherapy for BC.

Methods

In this systematic review, conducted in October 2024, only prospective studies on neoadjuvant immunotherapy for BC were included. Extracted variables encompassed study design, clinical-pathological characteristics, perioperative outcomes, pathological complete response (pCR) rates, overall survival (OS), event-free survival, and immune-related (irAEs) and treatment-related (TRAEs) adverse events.

Key findings and limitations

From 726 records, 35 studies met the inclusion criteria. The highest pCR rate observed was 54%, utilizing durvalumab. Perioperative chemoimmunotherapy with durvalumab plus cisplatin/gemcitabine showed greater OS than chemotherapy alone in the NIAGARA trial. The NEMIO trial achieved the highest 12-mo OS rate of 97%, using durvalumab in combination with tremelimumab and dose-dense methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, and cisplatin, followed by the AURA trial (95%) and the LCCC1520 trial (91%). At 24 mo, the NEBULA trial reported a 100% OS rate with three doses of atezolizumab, while PrECOG PrE0807 reached and OS rate of 89% with nivolumab and lirilumab. The highest rates of grade 3 and 4 irAEs were reported for nivolumab combined with ipilimumab (54%) and for durvalumab combined with tremelimumab (64%). The most common grade 3/4 irAEs were hepatitis (2–27%), kidney injury (2–100%), and skin rash (1.1–41%). Grade 3/4 TRAEs were comparable between the ICI and chemotherapy groups.

Conclusions and clinical implications

Neoadjuvant immunotherapy for BC has shown promising efficacy and a manageable adverse event profile. However, financial toxicity, the absence of predictive biomarkers, and the risk of significant irAEs remain challenges.

Patient summary

This study reviewed recent clinical trials that tested immunotherapy before surgery in patients with bladder cancer. The results suggest that a combination of immunotherapy and chemotherapy may improve outcomes and reduce the risk of cancer returning. These findings could help shape future treatment options for patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer.

1. Introduction

Bladder cancer (BC) remains a global public health challenge. In the USA, it ranks as the sixth most common cancer, comprising approximately 4.2% of all newly diagnosed cancer cases. According to the recent surveillance data, the incidence of BC is 18.2 per 100 000 individuals annually, while the mortality rate is 4.1 per 100 000 annually [1,2]. Muscle-invasive BC (MIBC) is defined by tumor invasion into the muscularis propria (stage T2 or higher), and it is detected in approximately 30% of patients at diagnosis [2] with a high risk of progression to metastatic disease, necessitating prompt and aggressive treatment to improve outcomes.

Radical cystectomy with pelvic lymphadenectomy remains the gold standard for the treatment of nonmetastatic MIBC, offering local disease control [3]. The addition of neoadjuvant chemotherapy with cisplatin-based regimens has been shown to significantly improve overall survival (OS) when combined with surgery [4]. However, despite this established benefit, approximately 50% of patients experience disease recurrence within 3 yr [5], and only 25–50% of patients are eligible for cisplatin-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy, underscoring the need for alternative therapeutic approaches [6].

In the last decades, many phase 1/2 and phase 2 clinical trials have studied the safety and efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) as neoadjuvant monotherapy or combined with platinum-based chemotherapy for BC [7]. The recent phase 3 NIAGARA trial reported improved OS with ICI-based neoadjuvant therapy compared with gemcitabine and cisplatin, positioning it as a potential new standard of care for MIBC treatment [8]. This systematic review evaluates the existing evidence on neoadjuvant immunotherapy for MIBC.

2. Methods

2.1. Literature search

This systematic review was conducted in strict compliance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) [9] statement on October 1, 2024, and it was registered in the PROSPERO international database of prospectively registered systematic reviews (CRD 42024591923).

A research question was established based on the Patient-Index test-Comparator-Outcome-Study design (PICOS) criteria, which is as follows [8]: what is the current evidence regarding the use of neoadjuvant immunotherapy in BC?

The search strategy was as follows: (Neoadjuvant Therapies) OR (Therapy, Neoadjuvant) OR (Neoadjuvant Treatment) OR (Neoadjuvant Treatments) OR (Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy) OR (Neoadjuvant Chemotherapies) OR (Neoadjuvant Systemic Therapy) OR (Neoadjuvant Systemic Therapies) OR (Systemic Therapy, Neoadjuvant) OR (Therapy, Neoadjuvant Systemic) OR (Neoadjuvant Systemic Treatment) OR (Neoadjuvant Systemic Treatments) OR (Systemic Treatment, Neoadjuvant) OR (Treatment, Neoadjuvant Systemic) AND (Neoplasm, Urinary Bladder) OR (Urinary Bladder Neoplasm) OR (Bladder Neoplasms) OR (Neoplasm, Bladder) OR (Bladder Tumors) OR (Bladder Tumor) OR (Tumor, Bladder) OR (Tumors, Bladder) OR (Neoplasms, Bladder) OR (Urinary Bladder Cancer) OR (Bladder Cancer) OR (Bladder Cancers) OR (Cancer, Bladder) OR (Cancer of Bladder) OR (Cancer of the Bladder) OR (Malignant Tumor of Urinary Bladder) AND (Immunotherapy).

We searched the following databases up to October 2024: PubMed/MEDLINE, Embase, and ClinicalTrials.gov (http://www.clinicaltrials.gov). We also reviewed the bibliographies of the included studies for further references to relevant trials. We included randomized clinical trials and cohort studies without language restrictions. Reviews, case reports, case series, letters to the editor, and editorials were excluded.

2.2. Study screening and selection criteria

Two independent authors screened all the retrieved records. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion. If relevant to the present review, the full text of the screened papers was selected. We included studies that met the following criteria: prospective studies with completed or partial results that enrolled patients with BC who underwent neoadjuvant treatment with immunotherapy.

2.3. Data extraction

The following variables were extracted from studies with partial or completed results: study initiation date, last update date, study type, mean patient age, number of patients per treatment arm, cisplatin eligibility, clinical and pathological staging, pathological response rates, oncological outcomes, immune-related adverse events (irAEs), and the designs of ongoing studies. All the extracted data were systematically organized into an Excel sheet for a comprehensive analysis.

2.4. Quality assessment and risk of bias

The risk of bias was analyzed in the prospective trials using ROBINS-1 [9], and randomized control trials were appraised with ROB-2 [9]; both these tools are developed by the Cochrane Collaboration for assessing the risk of bias in nonrandomized studies of interventions and in randomized trials, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 1 and 2).

3. Results

3.1. Literature screening

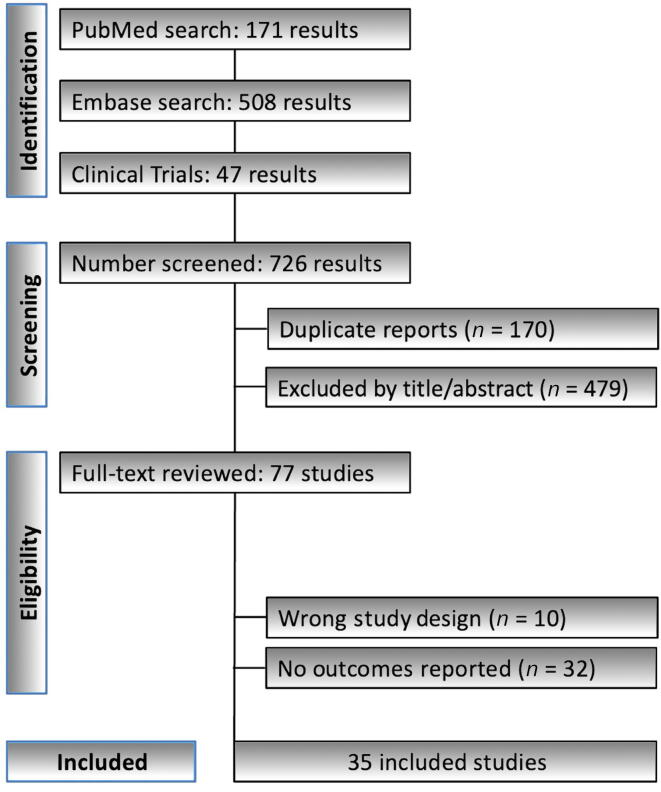

The literature search identified 726 records. After removing 170 duplicates, 556 records underwent screening based on title and abstract. Of these records, 479 were excluded as these did not align with the study's objectives. The full texts of the remaining 77 records were assessed for eligibility, resulting in 35 studies being included in the final analysis. Fig. 1 illustrates the PRISMA flowchart summarizing the search and selection processes.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flowchart summarizing the search and selection processes. PRISMA = Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses.

3.2. Quality assessment and risk of bias

In domain 1, most studies lacked a control group, presented incomplete study design information, and failed to adjust for confounders in single-arm prospective designs. Factors such as surgical approach, histological subtypes, and institutional variability in multicenter studies were often not accounted for. In domain 2, most studies were well rated, except for MDAACC [10], which modified its study design midway. In domain 3, the randomized controlled trial DUTRENEO [11] had a serious risk of bias, excluding 17% of patients from the primary analysis. In domain 4, one study [12] had a serious risk of bias due to not reporting the number of patients who discontinued treatment because of adverse events. In domain 5, one study excluded 28% of patients from the primary endpoint analysis [13], and another had 24% of patients with missing outcome data [14]. In domain 6, no serious risk of bias was identified. In domain 7, several studies [13,[15], [16], [17], [18], [19]] were at risk due to partial results, failure to reach planned sample size, or not meeting pre-established statistical power (Supplementary Fig. 1 and 2).

3.3. Fundamental concepts about immune checkpoint pathways

The roots of immunotherapy trace back to the 1890s when William Coley first used bacterial toxins to stimulate an immune response against tumors. Coley’s early work demonstrated the potential for harnessing the immune system to target cancer cells, but its widespread adoption faced challenges due to toxic side effects. The development of bone marrow transplantation by Fritz Bach in the 1960s marked an important milestone, leading to the integration of cellular therapies into cancer treatment [20]. By the 1990s, high-dose interleukin-2 (IL-2) therapy was approved for treating metastatic melanoma and metastatic renal cell carcinoma, ushering in a new era of immunotherapy [21,22]. Today, it includes a range of approaches, such as ICIs, T-cell transfer therapies, monoclonal antibodies, therapeutic vaccines, and immune system modulators.

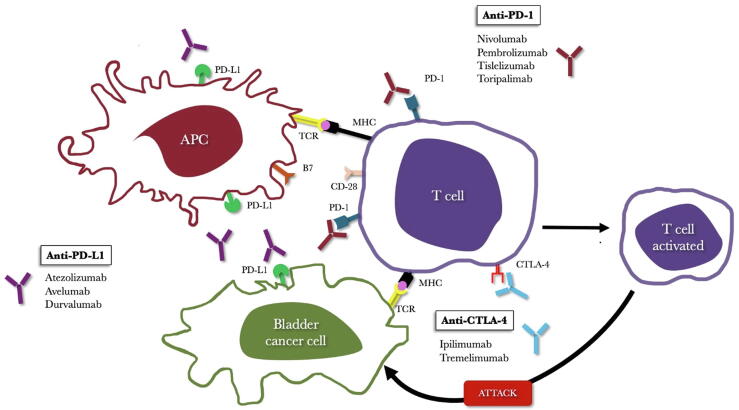

The main ICIs used in cancer therapy reactivate the immune system to better recognize and destroy tumor cells, and target two key cellular interactions. The first involves the programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) and its ligands, programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) and PD-L2; these pathways are important for maintaining immune homeostasis by preventing excessive immune cell activation. PD-1 is expressed on the surface of activated T and B lymphocytes and macrophages, while PD-L1 is predominantly found on antigen-presenting cells. The interaction between PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibits T-cell activation, resulting in reduced production of IL-2 and interferon-gamma, ultimately promoting immune tolerance. While this mechanism prevents autoimmunity, it also enables tumor cells expressing PD-L1 to evade immune surveillance. ICIs targeting the PD-1/PD-L1 axis block this interaction, effectively restoring T-cell activation and enhancing antitumor immunity (Fig. 2) [23].

Fig. 2.

Mechanism of action of checkpoint inhibitors targeting the PD-1/PD-L1 and CTLA-4 pathways. APC = antigen-presenting cell; CTLA-4 = T-lymphocyte–associated protein 4; PD-1 = programmed cell death protein 1; PD-L1 = programmed death ligand 1.

The second main mechanism involves cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated protein 4 (CTLA-4), an immune checkpoint receptor expressed on activated T cells. CTLA-4 acts as a negative regulator of immune responses by competing with CD28 for binding to the B7.1 and B7.2 ligands on antigen-presenting cells. This competition reduces T-cell activation, preventing excessive immune responses and maintaining immune balance. Although the precise molecular pathways through which CTLA-4 exerts its inhibitory effects are still being studied, blocking of this receptor has been shown to enhance immune responses, particularly in cancer [[23], [24], [25]]. Ipilimumab, the first ICI approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2011, exploits this mechanism. While CTLA-4 inhibitors remain among the most studied and widely used ICIs, newer agents targeting other checkpoint receptors are currently under investigation [[26], [27], [28]].

3.4. Clinical trial design and clinical characteristics of patients

Our systematic review of the literature identified 35 published studies on neoadjuvant immunotherapy for BC, with two being phase 3 trials. The first study to evaluate neoadjuvant immunotherapy in patients with BC was a phase 1 trial initiated in 2007 involving 12 cisplatin-ineligible patients treated with ipilimumab. This study demonstrated the safety of using the immunotherapeutic agent in this clinical setting [12]. The second study on neoadjuvant immunotherapy was at phase 1–2, which included, for the first time, a cohort of cisplatin-eligible patients (HCRN GU14-188) [15]; it had two cohorts both of which received five doses of neoadjuvant pembrolizumab (200 mg every 3 wk). The cisplatin-eligible cohort also received gemcitabine with cisplatin, and the cisplatin-ineligible cohort received gemcitabine.

There are only two phase 3 studies with neoadjuvant ICIs in BC, the PIVOT IO 009 study [29], initiated in 2020, included 114 cisplatin-ineligible patients distributed across three cohorts: neoadjuvant nivolumab + bempegaldesleukin followed by adjuvant nivolumab + bempegaldesleukin (C1), neoadjuvant nivolumab followed by adjuvant nivolumab (C2), and radical cystectomy alone (C3) [29]. The second phase 3 study was the NIAGARA [8] trial, which randomized 1063 patients into two arms: the first arm received neoadjuvant durvalumab + cisplatin + gemcitabine followed by adjuvant durvalumab, while the second arm received neoadjuvant cisplatin + gemcitabine alone [8].

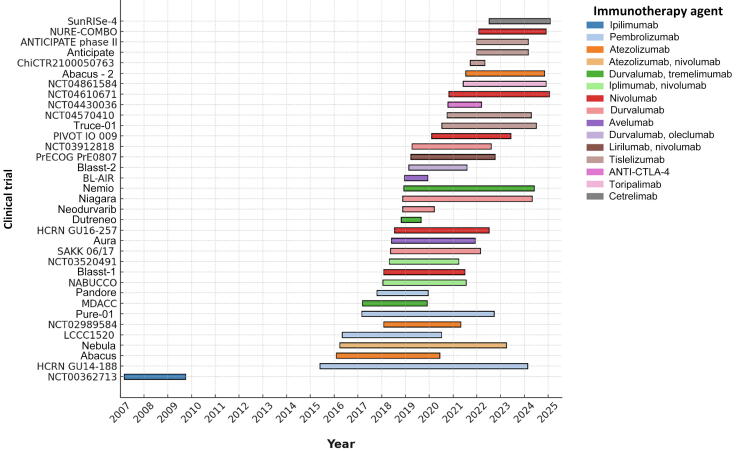

The mean age of patients enrolled in the studies ranged from 58 to 76 yr. A total of 21 studies included cisplatin-eligible patients, while 14 studies focused exclusively on cisplatin-ineligible patients. Only a minority of studies included patients with clinically positive lymph nodes in their cohorts. Interestingly, the three studies with the highest proportion of patients presenting a clinical suspicion of lymph node involvement (100%, 42%, and 26%) reported complete response rates exceeding 36% (50%, 46%, and 36%, respectively) [[30], [31], [32]]. Table 1 presents the design of studies and clinical characteristics of patients, and Fig. 3 presents all the studies.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of studies and patients included

| Trial | NCT | Study start | Last update | Treatment protocol | Phase | Patients (n) | Male/female (%) | Mean age (yr) | Cisplatin eligibility | ≥cT2 stage (%) | cN+ stage (%) | Histology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT00362713 [12] | NCT00362713 | Mar 1, 2007 | 2009 | C1: ipilimumab | 1 | 12 | – | – | No | – | – | 100% pure urothelial carcinoma |

| HCRN GU14-188 [15] | NCT02365766 | May 27, 2015 | 2023 | C1: pembrolizumab + GC C2: pembrolizumab + gemcitabine |

1–2 | 82 total C1: 42 C2: 40 |

– | 64 73 |

Yes | C1: 42.9 C2: 60 |

0 | 100% pure urothelial carcinoma |

| ABACUS [53] | NCT02662309 | Feb 1, 2016 | 2019 | C1: atezolizumab | 2 | 87 | 85/15 | 73 | No | 100 | 0 | Histopathologically confirmed urothelial carcinoma (T2-T4a) of the bladder. Patients with mixed histologies are required to have a dominant urothelial carcinoma pattern |

| NEBULA [37] | NCT02451423 | Mar 29, 2016 | 2024 | C1: atezolizumab (single dose) C2: atezolizumab (2 doses) C3: atezolizumab (3 doses) |

2 | 20 total C1: 6 C2: 5 C3: 9 |

74/26 | 70 | No | 100 | 10 | Patients with mixed histology are required to have a dominant urothelial carcinoma pattern |

| LCCC1520 [32] | NCT02690558 | May 1, 2016 | 2022 | C1: pembrolizumab + GC | 2 | 39 | 82/18 | 66 | Yes | 100 | 26 | 100% pure urothelial carcinoma |

| NCT02989584 [54] | NCT02989584 | Dec 20, 2016 | 2022 | C1: atezolizumab + GC | 1–2 | 39 | 85/15 | 65 | Yes | 100 | – | Pure urothelial cell carcinoma: 61.5% UC w/ squamous cell carcinoma: 23.1% UC w/ nested features: 5.1% UC w/ glandular differentiation: 5.1% UC w/ micropapillary features: 2.6% UC w/ focal plasmocytic features: 2.6% |

| PURE-01 [36] |

NCT02736266 |

Feb 27, 2017 | 2022 | C1: pembrolizumab | 2 |

155 |

87.1/12.9 |

68 |

Yes |

100 |

6 |

100% pure urothelial carcinoma |

| MDACC [10] | NCT02812420 | Mar 7, 2017 | 2020 | C1: durvalumab + tremelimumab | 1 | 28 | 71/29 | 71 | No | 97 | 0 | Pure urothelial cell carcinoma: 75% UC w/ squamous cell carcinoma component: 7% UC w/ micropapillary features: 7% UC w/ plasmacytoid features: 7% UC w/ small cell component: 3.5% UC w/sarcomatoid features: 3.5% |

| PANDORE [55] | NCT03212651 | Oct 17, 2017 | 2019 | C1: pembrolizumab | 2 | 39 | – | – | No | 100 | 0 | 100% pure urothelial carcinoma |

| NABUCCO [31] |

NCT03387761 | Jan 15, 2018 | 2024 | C1: ipilimumab + nivolumab | 1 | 24 | 75/25 | 65 | Yes | 100 | 42 | 100% pure urothelial carcinoma |

| BLASST-1 [16] | NCT03294304 | Jan 29, 2018 | 2022 | C1: nivolumab + GC | 2 | 41 | 35/65 | – | Yes | 100 | 3 | 100% pure urothelial carcinoma |

| NCT03520491 [35] | NCT03520491 | Apr 25, 2018 | 2022 | C1: nivolumab C2: nivolumab + ipilimumab |

2 | 30 total C1: 15 C2: 15 |

80/20 | 76 | No | 100 | 0 | Histologically confirmed diagnosis of urothelial carcinoma of the bladder. Variant histology is acceptable, if there is a predominant urothelial component |

| SAKK 06/17 [40] | NCT03406650 | May 15, 2018 | 2023 | C1: durvalumab + GC →durvalumab | 2 | 58 | 79/21 | 68 | Yes | 100 | 17 | Pure urothelial carcinoma: 75% UC w/ squamous cell carcinoma: 11% UC with adenocarcinoma: 7% UC w/ other subtypes (sarcomatoid, pleomorphic, large cell neuroendocrine, micropapillary): 7% |

| AURA [42] | NCT03674424 | Jun 1, 2018 | 2024 | C1: avelumab + ddMVAC C2: avelumab + GC C3: avelumab + paclitaxel + gemcitabine C4: avelumab |

2 |

137 total C1: 39 C2: 40 C3: 29 C4: 29 |

– |

– |

Yes | 100 |

– |

Histologically confirmed urothelial carcinoma or mixed histology with predominant urothelial component (>50%) |

| HCRN GU16-257 [14] | NCT03558087 | Jul 13, 2018 | 2023 | C1: nivolumab + GC | 2 | 76 | 79/21 | 69 | Yes | 100 | 0 | Urothelial carcinoma: 75% UC w/ squamous: 9.2% UC w/ glandular: 2.6% UC w/ micropapillary: 7.9% UC w/ other variant: 5.3% |

| DUTRENEO [11] | NCT03472274 | Oct 25, 2018 | 2023 | C1: cold group —standard cisplatin-based CT (GC or ddMVAC) C2: hot group—standard cisplatin-based CT (GC or ddMVAC) C3: hot group—durvalumab + tremelimumab |

2 | 61 total C1: 16 C2: 22 C3: 23 |

87/13 | 66 | Yes | C1: 100 C2: 100 C3: 100 |

C1: 6.3 C2: 4.5 C3: 8.7 |

Histological documentation of urothelial carcinoma |

| NEODURVARIB [56] | NCT03534492 | Nov 16, 2018 | 2020 | C1: durvalumab + olaparib | 2 | 28 | 89.7/10.3 | 70 | Yes | 100 | 10.6 | Histological confirmation of T2-T4a urothelial carcinoma in the transurethral bladder resection |

| NIAGARA [8] | NCT03732677 | Nov 16, 201 | 2024 | C1: durvalumab + GC →durvalumab C2: cisplatin + gemcitabine |

3 | 1063 total C1: 533 C2: 530 |

82/18 | 65 | Yes | 100 | 5.3 | C1: Urothelial carcinoma: 85.7% UC w/ squamous cell differentiation: 7.1% UC w/ glandular differentiation: 1.9% UC w/ other histological subtype: 5.3% C2: Invasive UC: 83.2% UC w/ squamous cell differentiation: 9.2% UC w/ glandular differentiation: 2.8% UC w/ other histological subtype: 4.7% |

| NEMIO [41] | NCT03549715 | Dec 6, 2018 | 2023 | C1: durvalumab + ddMVAC |

1–2 | 120 total C1: 60 C2: 59 |

78/22 | 64 | Yes | 100 | 5 | Urothelial carcinoma must be >50% |

| BL-AIR [17] | NCT03498196 | Dec 14, 2018 | 2020 | C1: avelumab | 1–2 | 1 | 100/0 | 58 | No | – | – | – |

| BLASST-2 [18] | NCT03773666 | Feb 20, 2019 | 2020 | C1: durvalumab C2: durvalumab + oleclumab |

1 | 20 total C1: 10 C2: 10 |

80/20 | 67 | No | 100 | 0 | Histologically confirmed bladder urothelial cell carcinoma No component of small cell histology |

| PrECOG PrE0807 [38] | NCT03532451 | Mar 22, 2019 | 2024 | C1: nivolumab C2: nivolumab + lirilumab |

1 | 43 | 67/33 | 75 | Yes | 100 | 5 | Predominant urothelial histology, as well as 20% tumor content at the time of transurethral resection of bladder tumor. The study states that it did not collect data about the possible variant histology components (and the percentages) |

| NCT03912818 [57] | NCT03912818 | Apr 10, 2019 | 2023 | C1: durvalumab + ddMVAC C3: durvalumab + carboplatin + gemcitabine |

2 | 6 total C1: 3 C3: 3 |

83/17 | 72 | Yes | 100 | – | Urothelial carcinomas w/ predominant sarcomatoid:16.6% Predominant squamous: 16.6% Predominant plasmacytoid: 16.6% Minority squamous: 33.2% Glandular and sarcomatoid: 16.6% |

| PIVOT IO 009 [29] | NCT04209114 | Feb 5, 2020 | 2022 | C1: nivolumab + B →nivolumab + B C2: nivolumab →nivolumab C3: RC alone |

3 | 114 total C1: 37 C2: 37 C3: 40 |

80.7/19.3 | 74 | No | 100 | – | Urothelial carcinoma of the bladder |

| TRUCE-01 [33] | NCT04730219 | Jul 11, 2020 | 2024 | C1: tislelizumab + nab-paclitaxel | 2 | 47 | 79/21 | 68 | Yes | 100 | 10 | Histopathologically confirmed urothelial carcinoma. Patients with mixed histologies are required to have a dominant (ie, 50% at least) urothelial cell pattern |

| NCT04570410 [30] | NCT04570410 | Oct 1, 2020 | 2024 | C1: tislelizumab + GC | 2 | 14 | – | 67 | Yes | 100 | – | Urothelial carcinoma |

| NCT04430036 [58] | NCT04430036 | Oct 14, 2020 | 2020 | C1: AGEN1884 (anti–CTLA-4 antibody) + AGEN2034 (anti–PD-1) + GC | 2 | 4 | 50/50 | 58.5 | Yes | 100 | – | – |

| NCT04610671 [59] | NCT04610671 | Oct 26, 2020 | 2022 | C1: CG0070 + nivolumab | 1 | 21 | 81/19 | 75 | No | 100 | – | Histopathologically confirmed urothelial carcinoma, pure or mixed histology urothelial carcinoma |

| NCT04861584 [34] | NCT04861584 | Jun 3, 2021 | 2023 | C1: toripalimab + GC | 2 | 16 | 75/25 | 63.5 | Yes | 100 | – | Histopathologically confirmed, locally advanced bladder urothelial carcinoma |

| ABACUS-2 [19] | NCT04624399 | Jul 13, 2021 | 2023 | C1: atezolizumab | 2 | 23 | – | 70 | No | 89 | 0 | Histopathologically confirmed carcinoma of the urothelium in the bladder with mixed or rare histological subtypes such as squamous cell or adenocarcinoma. Patients with mixed histologies are required to have a dominant nontransitional cell pattern |

| ChiCTR2100050763 [13] | ChiCTR2100050763 | Sep 20, 2021 | 2024 | C1: tislelizumab | 2 | 21 | – | – | Yes | 100 | – | – |

| ANTICIPATE [60] | NCT04813107 | Dec 28, 2021 | 2023 | C1: APL-1202 (nitroxoline) + tislelizumab | 1 | 9 | – | – | No | 100 | – | Histopathologically confirmed transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. Patients with mixed histologies are required to have a dominant (ie, >50%) transitional cell pattern |

| ANTICIPATE II [61] | NCT04813107 | Dec 28, 2021 | 2024 | C1: APL-1202 (nitroxoline) + tislelizumab C2: tislelizumab |

2 | 32 total C1:18 C2:14 |

– | – | No | C1: 61 C2: 72 |

– | Histopathologically confirmed transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. Patients with mixed histologies are required to have a dominant (ie, >50%) transitional cell pattern |

| NURE-COMBO [39] | NCT04876313 | Jan 27, 2022 | 2024 | C1: nivolumab + nab-paclitaxel | 2 | 31 | – | – | Yes | 100 | 6.4 | Urothelial carcinoma: 48.4% Variant histology: 51.6% |

| SunRISe-4 [62] | NCT04919512 | Jul 7, 2022 | 2024 | C1: TAR-200 (intravesical gradual release of gemcitabine) + cetrelimab C2: cetrelimab |

2 | 122 total C1: 80 C2: 42 |

85/15 | 73 | No | 100 | 0 | Histologically proven urothelial carcinoma of the bladder. Participants with variant histological subtypes are allowed if tumor(s) demonstrate urothelial predominance. However, the presence of small cell or neuroendocrine variants will make a participant ineligible |

B = bempegaldesleukin; C = cohort; CT = chemotherapy; CTLA-4 = T-lymphocyte–associated protein 4; ddMVAC = dose-dense methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, and cisplatin; GC = gemcitabine + cisplatin; PD-1 = programmed cell death protein 1; RC = radical cystectomy; UC = urothelial carcinoma; w/ = with.

Fig. 3.

Timeline of all included studies, showing the year of initiation and most recent publication for each. Studies are stratified by the immune checkpoint inhibitor used. CTLA-4 = T-lymphocyte–associated protein 4.

3.5. Pathological response

The concept of a pathological complete response (pCR) is most often defined as pathological pT0N0 and adopted as the primary endpoint in most studies (85.7%). However, one study [14] considered <pT1N0 as the primary endpoint and classified it as a pathological response, while three other studies [16,33,34] used ≤pT1N0 as their pathological response endpoint.

The pCR rates in the immunotherapy arms of studies varied widely, ranging from 0% in the NCT03520491 trial [35], which evaluated durvalumab in combination with carboplatin and gemcitabine, to 54% in the HCRN GU14-188 trial [15], where pembrolizumab was combined with cisplatin and gemcitabine. This significant variability can be attributed to differences in the number of patients in each cohort, the diverse clinical characteristics of patients across studies, and the heterogeneity of treatment regimens employed. These findings highlight the necessity for standardized protocols and larger cohorts to assess the impact of immunotherapy in neoadjuvant settings more accurately.

The NIAGARA study [8], the largest trial involving neoadjuvant immunotherapy, defined pT0N0 as a pCR. In the arm treated with neoadjuvant durvalumab, cisplatin, and gemcitabine followed by adjuvant durvalumab, the pCR rate was 37.3%, compared with 27.5% in the arm receiving neoadjuvant cisplatin and gemcitabine alone. These results underscore the added value of immunotherapy in the neoadjuvant setting compared with chemotherapy alone. When considering patients with a final pathological staging of ≤pT1N0, the immunotherapy group achieved 49.7%, compared with 40.6% in the chemotherapy-only group. Table 2 presents the clinical characteristics and pathological responses.

Table 2.

Pathological responses and oncological outcomes

| Trial | Treatment protocol | pCR meaning | pCR rate (%) | pT≤1N0 rate (%) | Survival Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT00362713 [12] | Ipilimumab | – | – | – | – |

| HCRN GU14-188 [15] | A: Pembrolizumab + GC B: Pembrolizumab + gemcitabine |

pT0N0 | A: 54 B: 53 |

A: 41 B: 41 |

C1: RFS 18 mo, 82%; OS 36 mo, 78.9% C2: RFS 18 mo, 65.1%; OS 36 mo, 65.7% |

| ABACUS [53] | Atezolizumab | pT0N0 | 31 | – | – |

| NEBULA [37] | A: Atezolizumab (single dose) B: Atezolizumab (2 doses) C: Atezolizumab (3 doses) |

pT0N0 | Global: 14 A: 14 B: 14 C: 14 |

Global: 23 A: 23 B: 23 C: 23 |

24 mo: RFS—C1: 67%; C2: 83%; C3: 82%; all groups: 77% OS—C1: 80%; C2: 83%; C3: 100%; all groups: 90% |

| LCCC1520 [32] | Pembrolizumab + GC | pT0N0 | 36 |

56 |

12 mo: EFS: 89% RFS: 75% OS: 91% |

| NCT02989584 [54] | Atezolizumab + GC | pT0N0 | 41 | 69 | – |

| PURE-01 [36] | Pembrolizumab | pT0N0 | 36.8 |

16.8 | 36 mo: RFS: 96.3% for ypT0N0 RFS: 96.1% for ypT1/a/isN0 RFS: 74.9% for ypT2-4N0 RFS: 58.3% for ypTanyN1-3 EFS PD-L1 tertiles (lower tertile: 59.7% vs medium tertile: 76.7% vs higher tertile: 89.8%) |

| MDACC [10] | Durvalumab + tremelimumab | pT0N0 |

37.5 |

58 |

12 mo: RFS: 82.8%, OS: 88.8% |

| PANDORE [55] | Pembrolizumab | pT0N0 | 29.4 | – | – |

| NABUCCO [31] |

Ipilimumab + nivolumab | pT0N0 |

46 | 58 | – |

| BLASST-1 [16] | Nivolumab + GC | ≤T1N0 | 49 |

65.9 |

12 mo: RFS: 85.4% PFS: 83% |

|

NCT03520491 [35] |

A: Nivolumab B: Nivolumab + ipilimumab |

pT0N0 |

A: 13 B: 7 |

A: 26 B: 20 |

12 mo: C1—EFS: 81%; RFS: 77% C2—EFS: 79%; RFS: 68% |

| SAKK 06/17 [40] |

Durvalumab + GC →durvalumab | pT0N0 |

32.7 |

59.6 |

36 mo: EFS: 73%; OS: 81% |

| AURA [42] |

A: Avelumab + ddMVAC B: Avelumab + GC C: Avelumab + paclitaxel + gemcitabine D: Avelumab |

pT0N0 |

– |

– |

C1—DFS 12 mo: 97%; DFS 36 mo: 77%; OS 12 mo: 95%; OS 36 mo: 87% C2—DFS 12 mo: 92%; DFS 36 mo: 72%; OS 12 mo: 89%; OS 36 mo: 73% C3—EFS 12 mo: 52%; OS: 67% C4—EFS 12 mo: 68%; OS: 75% |

| HCRN GU16-257 [14] | Nivolumab + GC | <pT1N0 |

43 |

– |

– |

| DUTRENEO [11] | A: Cold group—standard cisplatin-based CT (GC or ddMVAC) B: Hot group—standard cisplatin-based CT (GC or ddMVAC) C: Hot group—durvalumab + tremelimumab |

pT0N0 | A: 68.8 B: 36.4 C: 34.8 |

– | – |

| NEODURVARIB [56] | Durvalumab + olaparib | pT0N0 | 44.5 | – | – |

| NIAGARA [8] |

A: Durvalumab + GC →durvalumab B: Cisplatin + gemcitabine |

pT0N0 | A: 37.3 B: 27.5 |

A: 49.7 B: 40.6 |

24 mo: C1—EFS: 67.8%; OS: 82.2% C2—EFS: 59.8%; OS: 75.2% |

| NEMIO [41] | A: Durvalumab + ddMVAC B: Durvalumab + tremelimumab+ ddMVAC |

pT0N0 |

Global: 47.8 A: 49 B: 47 |

Global: 66 A: 71 B: 61 |

12 mo: C1: DFS: 80%; OS: 89% C2: DFS: 90%; OS: 97% |

| BL-AIR [17] | Avelumab | – | – | – | – |

| BLASST-2 [18] | A: Durvalumab B: Durvalumab + oleclumab |

pT0N0 | 12.5 | 25 | – |

| PrECOG PrE0807 [38] | A: Nivolumab B: Nivolumab + lirilumab |

pT0N0 |

A: 17 B: 21 |

A: 25 B: 32 |

24 mo: C1—RFS: 73%; OS: 82% C2—RFS: 71%; OS: 89% |

| NCT03912818 [57] | A: Durvalumab + ddMVAC B: Durvalumab + GC C: Durvalumab + carboplatin + gemcitabine |

pT0N0 |

A: 33.3 B: 0 |

A: 0 B: 50 |

– |

| PIVOT IO 009 [29] | A: Nivolumab + B →nivolumab + B B: Nivolumab →nivolumab C: RC alone |

pT0N0 |

A: 10.8 B: 10.8 C: 2.5 |

– | 30 mo: C1: EFS: 22% C2: NA C3: EFS: 15% |

| TRUCE-01 [33] | Tislelizumab + nab-paclitaxel | ≤pT1N0 | 47 | 34 | 12 mo: RFS: 82% |

| NCT04570410 [30] | Tislelizumab + GC | pT0N0 | 50 | 57.1 | – |

| NCT04430036 [58] | AGEN1884 (anti–CTLA-4 antibody) + AGEN2034 (anti–PD-1) + GC | pT0N0 | 50 | 75 | – |

| NCT04610671 [59] | CG0070 + nivolumab | pT0N0 | 53 | – | – |

| NCT04861584 [34] | Toripalimab + GC | ≤pT1N0 | 25 | 85.71 | – |

| ABACUS-2 [19] | Atezolizumab | pT0N0 | 35 | – | – |

| ChiCTR2100050763 [13] | Tislelizumab | pT0N0 | 58.8 | – | – |

| ANTICIPATE [60] | APL-1202(nitroxoline) + tislelizumab | pT0N0 | 12.5 | 62.5 | – |

| ANTICIPATE II [61] | A: APL-1202(nitroxoline) + tislelizumab B: Tislelizumab |

pT0N0 | A: 39 B: 21 |

A: 44 B: 21 |

– |

| NURE-COMBO [39] | Nivolumab + nab-paclitaxel | pT0N0 | 38 | 72 | 12 mo: EFS: 96.4% |

| SunRISe-4 [62] | A: TAR-200 (intravesical gradual release of gemcitabine) + cetrelimab B: Cetrelimab |

pT0N0 | A: 42 B: 23 |

A: 60 B: 36 |

– |

B = bempegaldesleukin; C = cohort; CT = chemotherapy; CTLA-4 = T-lymphocyte–associated protein 4; ddMVAC = dose-dense methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, and cisplatin; DFS = disease-free survival; EFS = event-free survival; GC = cisplatin + gemcitabine; NA = not applicable; OS = overall survival; pCR = pathological complete response; PD-1 = programmed cell death protein 1; PD-L1 = programmed death ligand 1; PFS = progression-free survival; RC = radical cystectomy; RFS = recurrence-free survival.

3.6. Perioperative outcomes

Regarding perioperative outcomes, the lowest completion rate for neoadjuvant therapy was 35% with nivolumab, with the primary adverse event leading to therapy discontinuation being kidney injury, reported in up to 5.7% of cases. The no-surgery rate ranged from 0% to 40%, with the main reasons for not proceeding to surgery being refusal of the procedure (up to 7%) and disease progression (up to 12.5%). Among the studies, only PURE-01 [36] reported the average surgery duration (361 min). The length of hospital stay ranged from 6.1 to 14 d. Intraoperative complications were reported in only two studies: one case of obturator nerve damage [10] and one case of aortic injury [37]. The estimated blood loss ranged from 428 to 444 ml, and the major perioperative complications were reported in 1.8–19% of cases. It is worth noting that most studies did not report perioperative outcomes, highlighting an important area for improvement in future research.

Perioperative surgical outcomes—including intraoperative complications, operative time, need for conversion, surgical approach, and postoperative complications—remain largely under-reported in trials evaluating ICIs in MIBC. Given the increasing integration of ICIs in the neoadjuvant setting, dedicated prospective studies are needed to assess its impact on surgical feasibility and safety. This includes potential changes in tissue characteristics, inflammation, fibrosis, and perioperative morbidity that may influence surgical complexity and patient recovery. Improved understanding of these factors is critical to guide multidisciplinary decision-making and optimize the timing of cystectomy following ICI therapy.

3.7. Oncological outcomes

A minority of the studies reported oncological outcomes, with only 15 out of the 35 studies analyzing such data. Nivolumab was the most frequently studied drug for oncological outcomes [16,29,35,38,39], followed by durvalumab [8,10,40,41]. The studies reporting the highest OS at 12 mo included the following: NEMIO [41], which achieved an OS rate of 97% in patients treated with durvalumab combined with tremelimumab and dose-dense methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, and cisplatin (MVAC); AURA [42], which presented an OS rate of 95% in patients receiving avelumab plus dose-dense MVAC,; and LCCC1520 [32], which reported an OS rate of 91% in patients treated with pembrolizumab, cisplatin, and gemcitabine. For studies reporting OS at 24 mo, the highest OS was observed in the NEBULA [37] study, with a 100% rate of OS in patients who received three doses of atezolizumab, and the PrECOG PrE0807 [38] study, which used nivolumab combined with lirilumab, achieving an OS rate of 89%.

The study with the most robust evidence to date, the NIAGARA [8] trial, adopted event-free survival (EFS) as its primary oncological endpoint, defined as the time from randomization to progressive disease precluding radical cystectomy, the first recurrence of disease after radical cystectomy, the expected date of surgery, or death from any cause. At 24 mo, an EFS rate of 67.8% and an OS rate of 82.2% were reported in patients treated with neoadjuvant durvalumab associated with cisplatin and gemcitabine followed by adjuvant durvalumab. In contrast, the cohort treated with cisplatin and gemcitabine only presented 59.8% EFS rate and 75.2% OS rate.

3.8. Immune- and treatment-related adverse events

The safety and tolerability of treatment are critical factors in determining the success of neoadjuvant regimens for patients undergoing curative-intent therapies. For neoadjuvant approaches incorporating ICIs to become a standard of care, they must demonstrate a safety profile that is comparable to, or better than, the neoadjuvant chemotherapy while also achieving similar or superior efficacy. ICIs, while promising, can lead to irAEs, which are off-target inflammatory effects that may impact multiple organ systems. The characteristics, frequency, and timing of these irAEs vary depending on the specific ICI utilized. While most irAEs tend to be mild to moderate and respond effectively to corticosteroid treatment, severe and clinically significant cases can occur, necessitating careful monitoring and management [43].

The regimens associated with the highest incidence of irAEs were avelumab in the BL-AIR [17] study (100%), durvalumab combined with tremelimumab in the MDACC [10] study (100%), and nivolumab combined with ipilimumab in the NABUCCO [31] study (100%). The lowest rates of irAEs were observed with durvalumab and tremelimumab in the NEMIO [41] study (0%) and with pembrolizumab in the LCCC1520 [32] study (2.5%). For grade 3 and 4 irAEs, the highest rates were reported with nivolumab combined with ipilimumab in the NABUCCO [31] study (54%) and with durvalumab combined with tremelimumab [64%]. Hepatitis was the most frequently reported irAE, cited in 16 studies, with incidences ranging from 2% to 27%. Kidney injury was reported in 11 studies, with rates ranging from 2% to 100%. Skin rash was reported in 15 studies, with incidence ranging from 1.1% to 41%. The regimen most associated with delays in radical cystectomy was durvalumab combined with tremelimumab, with a 13% delay rate in the DUTRENEO [11] study. The irAEs are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Immune-related adverse events

| Trial | Treatment | Number of patients | Any irAE, n (%) | G3/G4 irAE, n (%) | Most common (G3/G4) | RC withheld because of TRAEs | Treatment discontinuation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABACUS [53] | Atezolizumab | 87 | 6 (6.8) | 6 (6.8) | Hepatitis (4.5%)/skin rash (1.1%)/myocarditis (1.1%) | 3 (3.5%) | Yes (3%) |

| ABACUS-2 [19] | Atezolizumab | 23 | 3 (13) | 1 (4.3) | Hepatitis (9%)/kidney injury (4%) | No | No |

| ANTICIPATE [60] | Tislelizumab and APL-1202 (nitroxoline) | 9 | – | – | Hepatitis (11.1%) | – | No |

| ANTICIPATE II [61] | A: Tislelizumab and APL-1202 (nitroxoline) B: Tislelizumab |

32 total A: 18 B: 14 |

2 (11) 2 (14.3) |

– – |

Kidney injury (5.5%)/hepatitis (5.5%) Immune hyperthyroidism (14.3%) |

Yes Yes |

Yes (11.1%) Yes (7.2%) |

| AURA [42] | A: Avelumab + ddMVAC B: Avelumab + GC C: Avelumab + paclitaxel + gemcitabine D: Avelumab |

137 total A: 39 B: 40 C: 29 D: 29 |

– – – – |

– – – – |

– | 2 (1.4%) | – |

| BL-AIR [17] | Avelumab | 1 | 1 (100) | 0 | Kidney injury (100%) | – | Yes (100%) |

| BLASST-1 [16] | Nivolumab + GC | 41 | 28 (68) | 0 | Skin rash (30%)/hepatitis (27%)/kidney injury (7%) | No | No |

| BLASST-2 [18] | A: Durvalumab B: Durvalumab + oleclumab |

20 total A: 10 B: 10 |

– – |

– – |

– – |

– – |

No |

| ChiCTR2100050763 [13] | A: Cisplatin + gemcitabine + tislelizumab B: Carboplatin + gemcitabine + tislelizumab |

21 total | – – |

– – |

– | No No |

– |

| DUTRENEO [11] | A: Cold group—standard cisplatin-based CT (GC or ddMVAC) B: Hot group—standard cisplatin-based CT (GC or ddMVAC) C: Hot group—durvalumab + tremelimumab |

61 total A: 16 B: 22 C: 23 |

0 2 (12.5) 5 (21) |

0 1 (4.5) 1 (4.3) |

Absent Skin rash (4%) Skin rash (8%)/hepatitis (2%) |

1 (6%) 2 (9%) 3 (13%) |

No |

| HCRN GU14-188 [15] | A: GC + pembrolizumab B: Gemcitabine + pembrolizumab |

82 total A: 42 B: 40 |

– – |

10 (11.2) – – |

Hepatitis (3.7%)/skin rash (2.5%)/pneumonitis (2.5%)/colitis (2.5%) | – – |

– |

| HCRN GU16-257 | GC + nivolumab | 76 | 70 (92) | 1 (1.3) | Kidney injury (50%)/hepatitis (25%)/skin rash (17%) | – | – |

| LCCC1520 [32] | Pembrolizumab + GC | 39 | 1 (2.5) | 1 (2.5) | Diabetes mellitus (2.5%) | No | Yes (2%) |

| MDACC [10] | Durvalumab + tremelimumab | 28 | 30 (100) | 18 (64) | Skin rash (29%)/amylase increased (29%)/hepatitis (21%)/lipase increased (18%)/colitis (11%) | 2 (7%) | Yes (7%) |

| NABUCCO [31] | Nivolumab + ipilimumab | 24 | 24 (100) | 13 (54) | Lipase increased (33%)/diarrhea (21%)/hepatitis (21%)/skin rash (21%)/colitis (12%) | 1 (4%) | Yes (25%) |

| NCT00362713 [12] | Ipilimumab | 6 | – | – | – | – | – |

| NCT02989584 [54] | Atezolizumab + GC | 39 | 47 (100) | 7 (18) | Pancreatitis (9%)/hepatitis (2%)/kidney injury (2%)/skin rash (2%) | No | No |

| NCT03520491 [35] | A: Nivolumab B: Nivolumab + ipilimumab |

30 total A: 15 B: 15 |

– – |

– – |

Myocardites (1.7%) Lipase increase (20%)/hepatitis (33%) |

1 (6.6%) 2(13%) |

Yes (6.6%) Yes (13%) |

| NCT03912818 [57] | A: Durvalumab + ddMVAC B: Durvalumab + GC C: Durvalumab, carboplatin, and gemcitabine |

6 total A: 3 B: 0 C: 3 |

0 – 1 (33) |

0 – 0 |

Absent – Kidney injury (33%) |

No – No |

No – No |

| NCT04430036 [58] | AGEN1884 (anti–CTLA-4 antibody) + AGEN2034 (anti–PD-1) + GC | 4 | 2 (50) | 0 | Hepatitis (25%)/skin rash (25%) | No | No |

| NCT04610671 [59] | Nivolumab + CG0070 | 21 | 1(5) | 0 | Thyroiditis (5%) | No | No |

| NCT04861584 [34] | Toripalimab + GC | 16 | 5 (30) | 0 | Thyroiditis (18.75%)/skin rash (12.5%) | – | No |

| NEBULA [37] | A: Atezolizumab (single dose) B: Atezolizumab (2 doses) C: Atezolizumab (3 doses) |

20 total A: 6 B: 5 C: 9 |

2 (33) 1 (20) 6 (66) |

0 0 0 |

Kidney injury (33%) Skin rash (20%) Kidney injury (27%)/skin rash (18%)/hepatitis (9%) |

No No No |

No No No |

| NEMIO [41] | A: Durvalumab + ddMVAC B: Durvalumab, tremelimumab + ddMVAC |

120 total A: 60 B: 59 |

0 0 |

0 0 |

Absent Absent |

– – |

No No |

| NEODURVARIB [56] | Durvalumab + olaparib | 28 | – | – | – | – | – |

| NIAGARA [8] | A: Durvalumab + GC →durvalumab B: GC |

1063 total A: 533 B: 530 |

98 (18.5) 77 (14.6) |

11 (2) 4 (0.75) |

Kidney injury (18.5%) Kidney injury (14.6%) |

9 (1.7%) 6 (1.1%) |

Yes (21.1%) Yes (15.1%) |

| NURE-COMBO [39] | Nivolumab + nab-paclitaxel | 31 | 7 (22.6) | 1 (3.2) | Hepatitis (22.6%) | – | Yes (16.1%) |

| PANDORE [55] | Pembrolizumab | 39 | – | – | – | – | – |

| PIVOT IO 009 [29] |

A: Nivolumab + B B: Nivolumab C: Radical cystectomy |

114 total A: 37 B: 37 C: 40 |

10 (27) 10 (27) 0 |

– – 0 |

Kidney Injury (13.5%)/skin rash (10.81%)/amylase increased (5.4%) Kidney injury (10.81%)/skin rash (10.81%)/arthritis (5.4%)/0 |

– – – |

Yes (21.6%) Yes (21.6%) No |

| PrECOG PrE0807 [38] | A: Nivolumab B: Nivolumab and lirilumab |

43 total A: 13 B: 30 |

1 (8) 3 (10) |

0 0 |

Skin rash (8%) Skin rash (10%) |

No No |

No No |

| PURE-01 [36] | Pembrolizumab | 155 | 11 (7.1) | 2 (1.2) | Hepatitis (3.9%)/skin rash (3.2%) | No | No |

| SAKK 06/17 [40] | Durvalumab + cisplatin-gemcitabine | 58 | 29 (50) | 7 (12) | Hepatitis (14%)/diarrhea (12%)/lipase or amylase increased (11%) | No | No |

| SunRise-4 [62] | A: TAR-200 (intravesical gradual release of gemcitabine) and cetrelimab B: Cetrelimab |

122 total A: 80 B: 42 |

– – |

– – |

– – |

No No |

Yes (8.9%) Yes (7.6%) |

| TRUCE-01 [33] | Tislelizumab + nab-paclitaxel | 47 | 26 (55) | 4 (8.4) | Skin rash (41%)/kidney injury (14%) | – | Yes (6.3%) |

B = bempegaldesleukin; CT = chemotherapy; CTLA-4 = T-lymphocyte–associated protein 4; ddMVAC = dose-dense methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, and cisplatin; G = grade; GC = cisplatin + gemcitabine; irAE = immune-related adverse event; PD-1 = programmed cell death protein 1; RC = radical cystectomy; TRAE = treatment-related adverse event.

The irAEs are related to immunotherapeutic agents, particularly the ICIs. In contrast, treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) refer to the side effects or complications that arise directly from any medical treatments, including both chemotherapy and immunotherapy [43]. Among the clinical trials comparing neoadjuvant immunotherapy and chemotherapy, the NIAGARA [8] and DUTRENEO [11] studies provided a comparative analysis of TRAE incidences. The NIAGARA [8] trial reported a similar frequency of grade 3–4 TRAEs in both the ICI group (40.6%) and the chemotherapy group (40.9%), showing no significant difference. However, the DUTRENEO [11] trial highlighted a higher incidence of grade 3–4 TRAEs—including neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, asthenia, and mucosal inflammation—among patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

3.9. Biomarkers

The identification of reliable predictive biomarkers for an ICI response is crucial to minimize treatment-associated toxicities and reduce the financial strain on health care systems caused by ineffective therapies. Among the most extensively studied biomarkers are PD-L1 expression (evaluated through immunohistochemistry), tumor mutational burden (reflecting the median number of mutations per megabase), and microsatellite instability [[44], [45], [46]]. The FDA has approved tumor mutational burden testing for patients with unresectable or metastatic solid tumors as a criterion for pembrolizumab treatment following progression after prior therapies [44]. PD-L1 expression by immunohistochemistry is a widely adopted predictive tool for assessing the response to anti–PD-1 and anti–PD-L1 therapies across various tumor types [45]. PD-L1 expression can be quantified through methods such as the tumor proportion score, which measures PD-L1 in tumor cells, or the combined positive score, which includes staining in tumor cells as well as immune cells [46]. However, significant limitations exist in the predictive power of PD-L1 expression. Some patients with low or undetectable PD-L1 expression have experienced durable responses to ICI treatment, raising concerns about the assay's sensitivity [47]. On the contrary, cases of PD-L1–positive patients who fail to respond to ICI therapy further highlight the need for improved predictive methods [48]. This underlines the necessity for the development of more robust and accurate biomarkers to predict ICI responses.

4. Discussion

4.1. The future of neoadjuvant immunotherapy: ongoing trials and biomarkers

The three largest ongoing phases 3 studies, with awaited results, involve patients with clinical staging T2-T4aN0M0 and predominant (>50%) urothelial histology. The KEYNOTE-866 [49] trial, initiated in 2019, includes two arms: one with neoadjuvant pembrolizumab and the other with platinum-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy. The trial has an actual enrollment of 907 patients, and the primary endpoints are pCR and EFS. The CA017-078 [50] trial launched in 2018 includes two arms: one with neoadjuvant gemcitabine and cisplatin, and another with the same chemotherapy agents combined with neoadjuvant nivolumab, followed by adjuvant nivolumab postoperatively. The trial has recruited 861 patients so far, with a target enrollment of 1200 patients. Its primary endpoints are pCR and EFS. Lastly, the KEYNOTE-905 [51] trial, which began in 2019, has three arms: one arm receiving neoadjuvant and adjuvant pembrolizumab, a second arm receiving only radical cystectomy, and a third arm involving neoadjuvant enfortumab vedotin combined with pembrolizumab, followed by adjuvant enfortumab vedotin and pembrolizumab. The study has currently enrolled 595 patients, with a target of 610 patients, and its primary endpoint is EFS.

The integration of magnetic resonance imaging with radiomics and circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) to detect residual disease after neoadjuvant therapy cycles may further refine treatment strategies, and in the future, new trials exploring less invasive strategies, including bladder preservation approaches, could benefit from immunotherapy advancements [52].

Histological variants of urothelial carcinoma, including micropapillary, plasmacytoid, and sarcomatoid subtypes, exhibit aggressive clinical behavior, early dissemination, and limited responsiveness to conventional neoadjuvant chemotherapy. The NIAGARA trial [8] included patients with variant histologies: squamous differentiation was present in 7.1% of patients in the durvalumab arm and 9.2% in the control arm; glandular variants were present in 1.9% and 2.8%, respectively; and other variants were present in 5.3% and 4.7%, respectively. In a prespecified subgroup analysis, patients with variant histologies demonstrated a favorable response to perioperative immunotherapy, with a hazard ratio for EFS of 0.52 (95% confidence interval, 0.32–0.84), exceeding that of patients with pure urothelial carcinoma. These findings may signal a paradigm shift, positioning ICI therapy as a neoadjuvant option not only for cisplatin-ineligible patients, but also for those harboring aggressive variant subtypes. However, further analyses with larger cohorts and trials specifically designed to evaluate histological variants are warranted to substantiate this potential change in clinical practice.

Another important topic that remains under investigation is the optimal timing of systemic immunotherapy in MIBC. Neoadjuvant immunotherapy offers theoretical advantages, such as the preservation of tumor architecture and microenvironment, which may enhance antigen presentation and immune priming. Furthermore, preoperative assessment of a pathological response to immunotherapy may assist in stratifying patients who could benefit from postoperative treatment intensification.

Conversely, adjuvant immunotherapy has yielded mixed results. The IMvigor010 trial failed to demonstrate benefit with atezolizumab, while CheckMate-274 showed improved disease-free survival with adjuvant nivolumab, particularly among patients with PD-L1–positive tumors. These trials enrolled heterogeneous populations, and patient selection may have influenced the outcomes. Additionally, the JAVELIN Bladder 100 trial, although conducted in the metastatic setting, supports the concept of postplatinum immunotherapy and indirectly informs adjuvant strategies in high-risk localized disease.

In the absence of validated predictive biomarkers—such as ctDNA dynamics or immune gene expression signatures—treatment intensification cannot be personalized yet. Therefore, clinical decisions should integrate individual risk profiles, pathological response, and tumor characteristics. Future risk-adapted strategies incorporating molecular profiling, including PD-L1 expression and postoperative ctDNA status, may help optimize therapeutic benefit while avoiding unnecessary systemic exposure.

New studies on neoadjuvant therapy in patients with bladder tumors are numerous, and their results are expected to be published in the coming years, which will allow for a better understanding of immunotherapy in this clinical setting.

5. Conclusions

The phase 3 results of the NIAGARA trial shed light on the survival advantages of perioperative chemoimmunotherapy over traditional neoadjuvant chemotherapy, positioning ICIs as a potential emerging standard for neoadjuvant therapy for MIBC in the coming years. This is particularly relevant for patients who cannot undergo chemotherapy due to comorbidities or poor performance status.

Nevertheless, irAEs pose a significant obstacle, impacting a substantial proportion of patients and, in some cases, leading to treatment discontinuation. Additionally, the financial burden of ICI therapy may limit its accessibility. To address these challenges, future research should prioritize the development of ICIs with reduced adverse effects and explore optimized dosing protocols to enhance treatment safety and efficacy. The outcomes of ongoing studies are anticipated to confirm the role of ICIs as the new gold standard in neoadjuvant therapy for MIBC.

Author contributions: Caio Vinicius Suartz had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Suartz, Fradet.

Acquisition of data: Suartz, de Lima, de almeida, Liebl, Lopes, Sant’Anna, Reis, de Campos.

Analysis and interpretation of data: Suartz.

Drafting of the manuscript: Suartz, de Lima, de almeida, Liebl, Lopes, Sant’Anna, Reis, de Campos, Mota, Melão, Nahas, Shahrour, Shabana, Ribeiro-Filho, Toren, Fradet.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Suartz, de Lima, de almeida, Liebl, Lopes, Sant’Anna, Reis, de Campos, Mota, Melão, Nahas, Shahrour, Shabana, Ribeiro-Filho, Toren, Fradet.

Statistical analysis: Suartz.

Obtaining funding: Fradet.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Suartz, de Lima, de almeida, Liebl, Lopes, Sant’Anna, Reis, de Campos, Mota, Melão, Nahas, Shahrour, Shabana, Ribeiro-Filho, Toren, Fradet.

Supervision: Fradet.

Other: None.

Financial disclosures: Caio Vinicius Suartz certifies that all conflicts of interest, including specific financial interests and relationships and affiliations relevant to the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript (eg, employment/affiliation, grants or funding, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, royalties, or patents filed, received, or pending), are the following: None.

Funding/Support and role of the sponsor: None.

Associate Editor: M. Carmen Mir

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euros.2025.07.010.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.National Cancer Institute. SEER Cancer Stat facts: bladder cancer. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/urinb.html.

- 2.Sung H., Ferlay J., Siegel R.L., et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gontero P., Birtle A., Capoun O., et al. European Association of Urology guidelines on non–muscle-invasive bladder cancer (TaT1 and carcinoma in situ)—a summary of the 2024 guidelines update. Eur Urol. 2024;86:531–549. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2024.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grossman H.B., Natale R.B., Tangen C.M., et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus cystectomy compared with cystectomy alone for locally advanced bladder cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:859–866. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee Y., Kim Y.S., Hong B., Cho Y.M., Lee J.L. Comparison of clinical outcomes in patients with localized or locally advanced urothelial carcinoma treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy involving gemcitabine-cisplatin and high dose-intensity MVAC. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2021;147:3421–3429. doi: 10.1007/s00432-021-03582-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cowan N.G., Chen Y., Downs T.M., et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy use in bladder cancer: a survey of current practice and opinions. Adv Urol. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/746298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Esteban-Villarrubia J., Torres-Jiménez J., Bueno-Bravo C., García-Mondaray R., Subiela J.D., Gajate P. Current and future landscape of perioperative treatment for muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Cancers. 2023;15:566. doi: 10.3390/cancers15030566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Powles T., Catto J.W., Galsky M.D., et al. Perioperative durvalumab with neoadjuvant chemotherapy in operable bladder cancer. N Engl J Med. 2024;391:1773–1786. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2408154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shamseer L., Moher D., Clarke M., et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ. 2015;350 doi: 10.1136/bmj.g7647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gao J., Navai N., Alhalabi O., et al. Neoadjuvant PD-L1 plus CTLA-4 blockade in patients with cisplatin-ineligible operable high-risk urothelial carcinoma. Nat Med. 2020;26:1845–1851. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-1086-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grande E., Guerrero F., Puente J., et al. DUTRENEO trial: a randomized phase II trial of durvalumab and tremelimumab versus chemotherapy as a neoadjuvant approach to muscle-invasive urothelial bladder cancer (MIBC) patients (pts) prospectively selected by an interferon (INF)-gamma immune signature. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(15 Suppl):5012. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bristol-Myers Squibb. Study of neoadjuvant ipilimumab in patients with urothelial carcinoma undergoing surgical resection [Clinical trial NCT00362713]. ClinicalTrials.gov. 2006. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT00362713.

- 13.Zeng Y., Li C., Lv C., et al. Bladder-sparing treatment for muscle-invasive bladder carcinoma: a single-center, single-arm clinical study of sequential neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by tislelizumab neoadjuvant immunotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2024;42(4 Suppl):596. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Galsky M.D., Daneshmand S., Lewis S.C., et al. Co-primary endpoint analysis of HCRN GU 16–257: Phase 2 trial of gemcitabine, cisplatin, plus nivolumab with selective bladder sparing in patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(6 Suppl):447. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown J., Kaimakliotis H.Z., Kelly W.K., et al. HCRN GU14-188: Phase Ib/II study of neoadjuvant pembrolizumab and chemotherapy for T2–4aN0M0 urothelial cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(6 Suppl):448. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gupta S., Sonpavde G., Weight C.J., et al. Results from BLASST-1 (Bladder Cancer Signal Seeking Trial) of nivolumab, gemcitabine, and cisplatin in muscle invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) undergoing cystectomy. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(6 Suppl):439. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taylor J. A window of opportunity trial: avelumab in non-metastatic muscle invasive bladder cancer. Identifier NCT03498196. 2018. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT03498196.

- 18.Wei X.X., McGregor B.A., Lee R.J., et al. Durvalumab as neoadjuvant therapy for muscle-invasive bladder cancer: preliminary results from the Bladder Cancer Signal Seeking Trial (BLASST)-2. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(6 Suppl):507. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Szabados B.E., Nogueron Martinez E., Alvarez Marquez F.J., et al. A phase II study investigating the safety and efficacy of neoadjuvant atezolizumab in non-urothelial, muscle invasive bladder cancer (ABACUS-2) Ann Oncol. 2023;34(Suppl. 2):S1201. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jagodinsky J.C., Harari P.M., Morris Z.S. The promise of combining radiation therapy with immunotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2020;108:6–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2020.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fyfe G.A., Fisher R.I., Rosenberg S.A., Sznol M., Parkinson D.R., Louie A.C. Long-term response data for 255 patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with high-dose recombinant interleukin-2 therapy. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:2410–2411. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.8.2410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Atkins M.B., Lotze M.T., Dutcher J.P., et al. High-dose recombinant interleukin 2 therapy for patients with metastatic melanoma: analysis of 270 patients treated between 1985 and 1993. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2105–2116. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.7.2105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alsaab H.O., Sau S., Alzhrani R., et al. PD-1 and PD-L1 checkpoint signaling inhibition for cancer immunotherapy: mechanism, combinations, and clinical outcome. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:561. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2017.00561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Farina M.S., Lundgren K.T., Bellmunt J. Immunotherapy in urothelial cancer: recent results and future perspectives. Drugs. 2017;77:1077–1089. doi: 10.1007/s40265-017-0748-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peggs K.S., Quezada S.A., Chambers C.A., Korman A.J., Allison J.P. Blockade of CTLA-4 on both effector and regulatory T cell compartments contributes to the antitumor activity of anti-CTLA-4 antibodies. J Exp Med. 2009;206:1717–1725. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chocarro L., Bocanegra A., Blanco E., et al. Cutting-edge: preclinical and clinical development of the first approved lag-3 inhibitor. Cells. 2022;11:2351. doi: 10.3390/cells11152351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rotte A., Sahasranaman S., Budha N. Targeting TIGIT for immunotherapy of cancer: update on clinical development. Biomedicines. 2021;9:1277. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines9091277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin C.C., Curigliano G., Santoro A., et al. Sabatolimab in combination with spartalizumab in patients with non-small cell lung cancer or melanoma who received prior treatment with anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy: a phase 2 multicentre study. BMJ Open. 2024;14 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2023-079132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grivas P., Van Der Heijden M.S., Necchi A., et al. PIVOT IO 009: A phase 3, randomized study of neoadjuvant and adjuvant nivolumab (NIVO) plus bempegaldesleukin (BEMPEG; NKTR-214) versus NIVO alone versus standard of care (SOC) in patients (pts) with muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) who are cisplatin (cis)-ineligible. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(6 Suppl) [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhuang J., Cao Q., Cai L., Wu Q., Lu Q. Tislelizumab in combination with gemcitabine plus cisplatin as neoadjuvant therapy for lymph node‐positive bladder cancer: results of a prospective study. J Clin Oncol. 2024;42(4 Suppl):619. [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Dijk N., Gil-Jimenez A., Silina K., et al. Preoperative ipilimumab plus nivolumab in locoregionally advanced urothelial cancer: the NABUCCO trial. Nat Med. 2020;26:1839–1844. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-1085-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rose T.L., Harrison M.R., Deal A.M., et al. Phase II study of gemcitabine and split-dose cisplatin plus pembrolizumab as neoadjuvant therapy prior to radical cystectomy (RC) in patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(6 Suppl):396. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.01003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Niu Y., Hu H., Wang H., et al. Phase II clinical study of tislelizumab combined with nab-paclitaxel (TRUCE-01) for muscle-invasive urothelial bladder carcinoma: bladder preservation subgroup analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(16 Suppl):4589. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu A., Xu P., Chen C., et al. A phase II study of toripalimab combined with gemcitabine-cisplatin as neoadjuvant therapy for patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(16 Suppl) [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guercio B.J., Pietzak E.J., Brown S., et al. Neoadjuvant nivolumab (N) +/- ipilimumab (I) in cisplatin-ineligible patients (pts) with muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(6 Suppl):498. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Basile G., Bandini M., Gibb E.A., et al. Neoadjuvant pembrolizumab and radical cystectomy in patients with muscle-invasive urothelial bladder cancer: 3-year median follow-up update of PURE-01 trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2022;28:5107–5114. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-22-2158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Natesan D.V., Zhang L., Oh D.Y., et al. Updated results of phase II trial using escalating doses of neoadjuvant atezolizumab for cisplatin-ineligible patients with nonmetastatic urothelial cancer ( NCT02451423) J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(15 Suppl) [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grivas P., Koshkin V.S., Chu X., et al. PrECOG PrE0807: a phase 1b feasibility trial of neoadjuvant nivolumab without and with lirilumab in patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer ineligible for or refusing cisplatin-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Eur Urol Oncol. 2024;7:914–922. doi: 10.1016/j.euo.2023.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Basile G., Mercinelli C., Raggi D., et al. First results of NURE-Combo: A phase 2 study of neoadjuvant nivolumab (NIVO) and nab-paclitaxel (ABX) followed by postsurgical adjuvant NIVO in patients (pts) with muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) J Clin Oncol. 2024;42(4 Suppl):610. doi: 10.1200/JCO.24.00576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cathomas R., Rothschild S., Hayoz S., et al. Perioperative chemoimmunotherapy with durvalumab for operable muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma (MIUC): Primary analysis of the single arm phase II trial SAKK 06/17. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(16 Suppl):4515. doi: 10.1200/JCO.23.00363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thibault C., Bennamoun M., Flechon A., et al. Durvalumab (D) +/- tremelimumab (T) in combination with dose-dense MVAC (ddMVAC) as neoadjuvant treatment in patients with muscle-invasive bladder carcinoma (MIBC): results of NEMIO, a randomized phase I-II trial. Ann Oncol. 2023;34(Suppl. 2):S1202. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Martinez Chanza N., Soukane L., Barthelemy P., et al. Avelumab as neoadjuvant therapy in patients with urothelial non-metastatic muscle invasive bladder cancer: a multicenter, randomized, non-comparative, phase II study (Oncodistinct 004 - AURA trial) BMC Cancer. 2021;21:1292. doi: 10.1186/s12885-021-08990-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Postow M.A., Sidlow R., Hellmann M.D. Immune-related adverse events associated with immune checkpoint blockade. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:158–168. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1703481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marcus L., Fashoyin-Aje L.A., Donoghue M., et al. FDA approval summary: pembrolizumab for the treatment of tumor mutational burden-high solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2021;27:4685–4689. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-21-0327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Havel J.J., Chowell D., Chan T.A. The evolving landscape of biomarkers for checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2019;19:133–150. doi: 10.1038/s41568-019-0116-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Akhtar M., Rashid S., Al-Bozom I.A. PD-L1 immunostaining: what pathologists need to know. Diagn Pathol. 2021;16:94. doi: 10.1186/s13000-021-01151-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sunshine J., Taube J.M. PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2015;23:32–38. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2015.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang F., Wang J.F., Wang Y., Liu B., Molina J.R. Comparative analysis of predictive biomarkers for PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors in cancers: developments and challenges. Cancers. 2021;14:109. doi: 10.3390/cancers14010109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Siefker-Radtke A.O., Steinberg G.D., Bedke J., et al. Phase III study of perioperative pembrolizumab (pembro) plus neoadjuvant chemotherapy (chemo) versus placebo plus neoadjuvant chemo in cisplatin-eligible patients (pts) with muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC): KEYNOTE-866. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38 6_suppl [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bristol-Myers Squibb. A phase 3, randomized, study of neoadjuvant chemotherapy alone versus neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus nivolumab or nivolumab and BMS-986205, followed by continued post-surgery therapy with nivolumab or nivolumab and BMS-986205 in participants with muscle-invasive bladder cancer (clinical trial NCT03661320). ClinicalTrials.gov. 2018. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT03661320.

- 51.Necchi A., Bedke J., Galsky M.D., et al. Phase 3 KEYNOTE-905/EV-303: perioperative pembrolizumab (pembro) or pembro + enfortumab vedotin (EV) for muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) J Clin Oncol. 2023;41 6_suppl [Google Scholar]

- 52.Suartz C.V., Martinez L.M., Cordeiro M.D., et al. Artificial intelligence for predicting response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy for bladder cancer A comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. Can Urol Assoc J. 2024;18:E276–E284. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.8681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Szabados B., Kockx M., Assaf Z.J., et al. Final results of neoadjuvant atezolizumab in cisplatin-ineligible patients with muscle-invasive urothelial cancer of the bladder. Eur Urol. 2022;82:212–222. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2022.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Funt S.A., Lattanzi M., Whiting K., et al. Neoadjuvant atezolizumab with gemcitabine and cisplatin in patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer: a multicenter, single-arm, phase II trial. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40:1312–1322. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.01485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Goubet A.-G., Alves Costa Silva C., Lordello De Melo L., et al. Bacteria-specific CXCL13-producing follicular helper T cells are putative prognostic markers to neoadjuvant PD-1 blockade in muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma [Poster presentation]. 2022 ASCO genitourinary cancers symposium, poster session B: urothelial carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(Suppl 6):535. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rodriguez-Moreno J.F., de Velasco G., Bravo Fernandez I., et al. Impact of the combination of durvalumab (MEDI4736) plus olaparib (AZD2281) administered prior to surgery in the molecular profile of resectable urothelial bladder cancer: NEODURVARIB trial. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(6 Suppl):542. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Khaki A.R., Fan A.C., Shah S., et al. Phase 2 open label study of durvalumab with neoadjuvant chemotherapy in variant histology bladder cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(6 Suppl):524. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ramamurthy C., Wheeler K.M., Trecarten S., et al. Perioperative immune checkpoint blockade for muscle-invasive and metastatic bladder cancer. J Cancer Immunol. 2024;6:29–39. doi: 10.33696/cancerimmunol.6.081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li R., Spiess P.E., Sexton W.J., et al. Phase Ib neoadjuvant CG0070 and nivolumab (N) for cisplatin (C)-ineligible muscle invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(16 Suppl) [Google Scholar]

- 60.Galsky M.D., Sfakianos J.P., Ye D.-W., et al. ANTICIPATE phase I: oral APL-1202 in combination with tislelizumab as neoadjuvant therapy in patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(16 Suppl) [Google Scholar]

- 61.Galsky M.D., Sfakianos J.P., Ye D., et al. Oral APL-1202 in combination with tislelizumab as neoadjuvant therapy in patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC): interim analysis of ANTICIPATE phase II trial. J Clin Oncol. 2024;42(4 Suppl):632. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Necchi A., Powles T., Balar A.V., et al. TAR-200 plus cetrelimab or cetrelimab alone as neoadjuvant therapy in patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer who are ineligible for or refuse neoadjuvant cisplatin-based chemotherapy: Interim analysis of SunRISe-4. Ann Oncol. 2024;35(Suppl. 2):S2. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.