Abstract

Light perception is a biological process that facilitates a profound interaction between the external world and the internal functions of living organisms. It begins with the absorption of photons with specialized visual pigments that contain vitamin A-derived chromophores. The light energy triggers the photoisomerization of the visual chromophore, initiating a cascade of signaling events that ultimately convert light into electrical signals interpreted as vision. However, the sustainability of vision relies on the continuous supply of the visual chromophore, which is maintained through light-dependent and light-independent processes. The importance of these processes is underscored by numerous blinding retinal diseases linked to impaired regeneration of the chromophore. Thus, research into the molecular mechanisms of visual chromophore biosynthesis has not only deepened our understanding of the organization of visual systems but also uncovered the etiologies of these debilitating diseases. In this review, we synthesize recent progress in understanding the mechanisms responsible for visual chromophore biosynthesis. We examine biological targets, therapeutic strategies, and drug discovery efforts aimed at restoring or bypassing metabolic blockades in visual chromophore regeneration, and assess the progress of clinical trials evaluating the effectiveness of therapies for degenerative retinal diseases.

Keywords: visual cycle, visual chromophore, retinal degeneration, retinoids, 11-cis-retinal, visual cycle modulators

1. Introduction

The perception of light is a fundamental biological process, especially for organisms equipped with visual systems. This capability allows them to detect, process, and interpret light stimuli, enabling the construction of meaningful representations of their environment (Fain, Hardie, & Laughlin, 2010; Yau & Hardie, 2009). In higher organisms, sophisticated visual systems transform light signals into complex neural codes, ultimately creating detailed images of the world. This intricate process supports behaviors essential for survival, reproduction, and adaptation to changing environments.

The initial step in all photosensitive systems involves converting light signals into specific cellular responses for further processing and interpretation (Luo, Xue, & Yau, 2008; Ridge, Abdulaev, Sousa, & Palczewski, 2003). This process relies on light-sensitive retinoid-based chromophores, whose conjugated double bonds allow for cis or trans isomerization (Palczewski, 2006; Wald, 1968a). The covalent binding of the 11-cis-retinal (11cRAL) or its derivatives (collectively called visual chromophores) to opsins (specialized retinal-binding G-protein-coupled receptors) forms light-sensitive visual pigments. The light-induced cis to trans isomerization of the visual chromophore triggers conformational changes in the opsin’s protein scaffold, activating downstream cellular signaling cascades (Choe, et al., 2011; Ernst, et al., 2014; Ridge, et al., 2003; Salom, et al., 2006) (Fig. 1). However, the activation of visual pigments necessitates the regeneration of the photoisomerized 11-cis chromophore and restoration of the opsins’ ground state, enabling continued responsiveness to light stimuli.

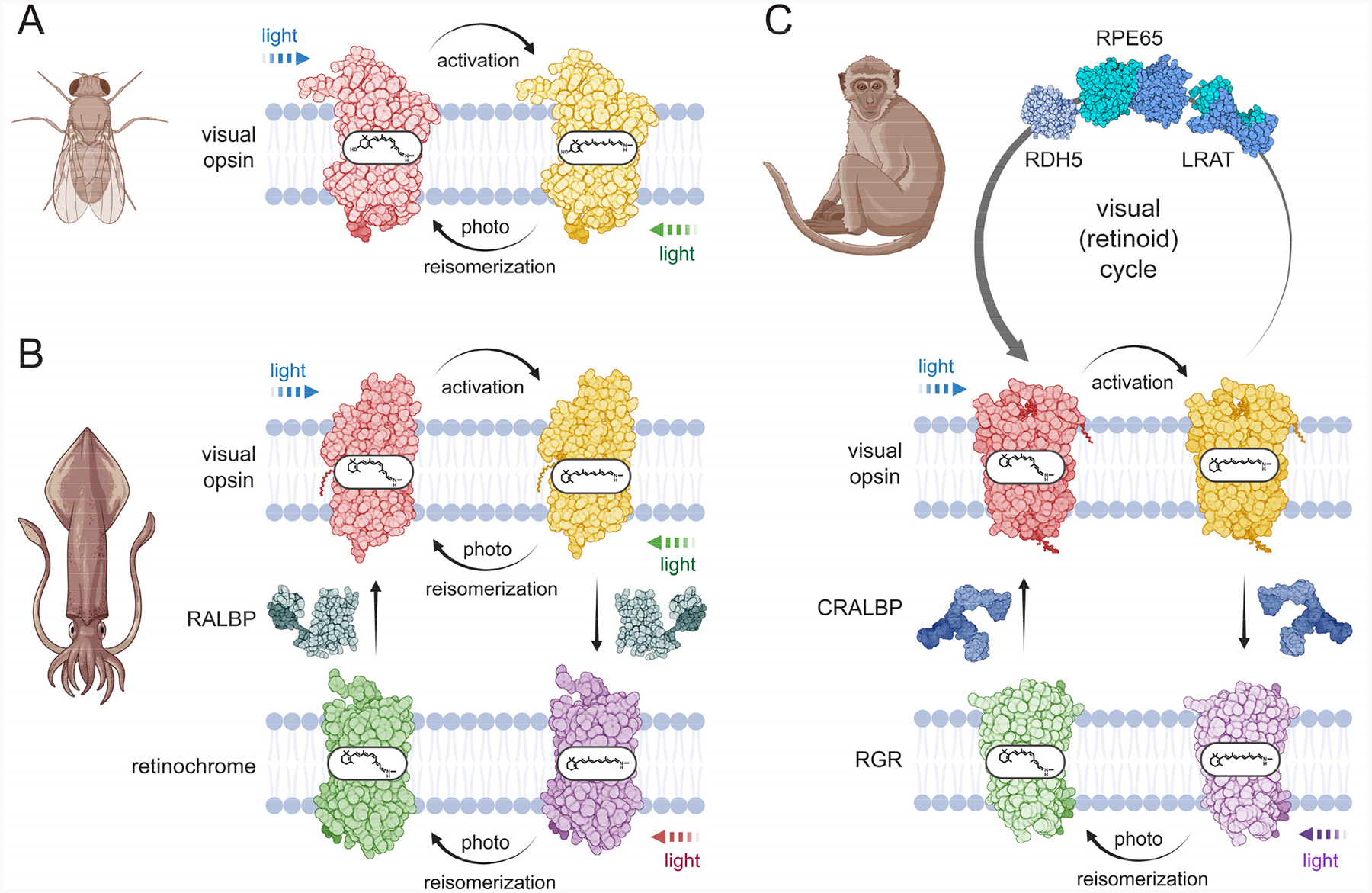

Figure 1 – Evolutionary strategies for the regeneration of visual opsins.

A. Visual pigments of invertebrates exist in two stable forms: a dark state and a light-activated state. When exposed to light, these pigments undergo a transition involving the isomerization of the visual chromophore from the 11-cis to the all-trans configuration. The photoproduct can then revert to the original dark state through subsequent absorption of a photon of light. B. In the squid eye, a bistable visual opsin operates alongside another bistable opsin called retinochrome. Retinochrome catalyzes the light-dependent conversion of atRAL back to the 11-cis configuration but does not play a role in phototransduction. Additionally, the retinal-binding protein RALBP acts as a carrier, transporting retinoids and supporting the regeneration of the visual pigment. C. Two distinct mechanisms for visual chromophore regeneration in vertebrates. Light-driven re-isomerization is catalyzed by RGR, a protein phylogenetically related to the retinochrome found in squid. The alternative mechanism is unique to vertebrates and involves an enzymatic, light-independent pathway. This process is carried out by a series of specialized enzymes, which operate in RPE cells. Visual opsins in the ground state are shown in red, in contrast to their light-activated forms, which are shown in yellow. Non-visual opsins (retinochrome and RGR) are depicted in green and purple to distinguish their 11cRAL- and atRAL-bound states, respectively. Different colors of the light symbol represent various wavelengths of light that contribute to retinoid isomerization processes. Created in BioRender (https://BioRender.com/f3x90bj).

Two fundamentally distinct strategies have evolved to regenerate the thermodynamically unfavorable 11-cis configuration of the retinoid moiety (Kiser, Golczak, & Palczewski, 2014; Koyanagi & Terakita, 2014) (Fig. 1). The evolutionarily older photoreversal mechanism utilizes energy of light to restore 11-cis configuration of the visual chromophore under continuous illumination (Hubbard & St George, 1958; Tsukamoto & Terakita, 2010). In this process, all-trans-retinylidene remains stably bound to the opsin scaffold (Tejero, et al., 2024). Absorption of a second photon of longer wavelength converts the chromophore back to the cis configuration, restoring the photoreceptor photosensitive ground state (Ehrenberg, et al., 2019) (Fig. 1A).

By contrast, visual opsins, such as vertebrate ciliary rhodopsin and cone opsins, lose their chromophore during light activation due to hydrolysis of the photoisomerized all-trans-retinylidene (Terakita, 2005; Wald, 1968a; Yau & Hardie, 2009). Consequently, these opsins depend on the external mechanisms of visual chromophore regeneration. These involve a light-independent biochemical pathway called the visual (retinoid) cycle and photic “back-isomerization”, in which the energy of light is used for direct regeneration of 11cRAL from the all-trans isomer by specialized non-visual retinal G protein-coupled receptor(Palczewski & Kiser, 2020) (Fig. 1B and C). These pathways allow vertebrates to sustain vision under varying and often challenging light conditions, ensuring acute sensitivity and adaptability to changes in light intensity.

Remarkably, these two strategies for 11-cis retinoid regeneration can coexist within a single organism. For instance, in the squid eye, photoreversal visual opsins operate alongside retinochrome, a non-visual opsin (Fig. 1B). Retinochrome catalyzes the conversion of all-trans-retinal (atRAL) back to the 11-cis configuration using light, though it does not contribute to phototransduction (Hara & Hara, 1965). Interestingly, retinochromes share a phylogenetic relationship with vertebrate retinal G-protein-coupled receptor (RGR) (P. Chen, Hao, et al., 2001) (Fig. 1C). While RGR does not promote phototransduction, it preferentially binds atRAL and facilitates its photoisomerization to the 11-cis configuration (P. Chen, Hao, et al., 2001; Hao & Fong, 1999). In recent years, accumulating biochemical, genetic, and physiological evidence suggests that vertebrates employ both photic and non-photic mechanisms to regenerate the visual chromophore efficiently, ensuring sustained vision across broad lighting intensities (Morshedian, et al., 2019; J. Zhang, et al., 2019).

The robust regeneration of the visual chromophore has long been recognized as crucial for maintaining photoreceptor sensitivity and health. Deficiencies in 11cRAL biosynthesis or inadequate clearance of retinoid metabolites are implicated in prevalent retinal degenerative diseases (den Hollander, Roepman, Koenekoop, & Cremers, 2008; Kiser & Palczewski, 2021; Travis, Golczak, Moise, & Palczewski, 2007). Advances in understanding the visual cycle and its dysfunctions have encouraged the development of targeted therapies to treat these blinding conditions. These include small-molecule modulators of ocular retinoid metabolism, agents that bypass metabolic blockage in 11-cis retinoid biosynthesis, and modern targeted genetic approaches like CRISPR/Cas9 for correcting pathogenic mutations in key visual cycle genes.

In this review, we synthesize recent progress in understanding the mechanisms underlying visual chromophore biosynthesis in vertebrates. By correlating biochemical, phenotypic, and pathological data, we provide a comprehensive overview of ocular retinoid metabolism. Finally, we highlight advances in targeting the visual cycle to develop effective therapies for degenerative retinal diseases.

2. Canonical (non-photic) visual cycle

The physiological ability to regenerate visual pigments in darkness was recognized alongside the discovery of retinal pigments themselves. In the late 19th century, German physiologist Willy Kühne demonstrated that a photobleached retina could regain its red color and photosensitivity when placed in contact with the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and kept in the dark (Ripps, 2008). Nearly a century later, George Wald identified 11cRAL, a vitamin A – A-derived molecule, as the light-sensing chromophore of rhodopsin (Wald, 1968b). By the early 2000s, the major protein components and enzymatic steps of the canonical visual cycle responsible for regenerating 11cRAL had been identified (Kiser, et al., 2014; Travis, et al., 2007). Subsequent genetic studies further clarified the non-photic metabolic steps involved in 11cRAL biosynthesis (Kiser, Golczak, Maeda, & Palczewski, 2012). Understanding the intricate ocular metabolism of retinoids has been critical for identifying the causes of pathological conditions linked to retinoid homeostasis and for developing new therapeutic strategies (C. H. Huang, Yang, Yang, Hou, & Chen, 2021; Manley, Meshkat, Jablonski, & Hollingsworth, 2023; Sajovic, et al., 2022; Travis, et al., 2007).

2.1. Ocular uptake of retinoids

Retinoids are classified as vitamins, meaning they cannot be synthesized de novo by humans or other animals and must instead be obtained from dietary sources. These sources include preformed retinoids or plant-derived pro-vitamin A carotenoids, such as β-carotene, α-carotene, and β-cryptoxanthin (Biesalski, Chichili, Frank, von Lintig, & Nohr, 2007; von Lintig, Moon, & Babino, 2021). Once absorbed and distributed to tissues, retinoids are converted into biologically active metabolites, including retinoic acid (RA), a ligand for nuclear retinoic acid receptors, and 11cRAL, the visual chromophore (von Lintig & Bandera, 2024; M. A. K. Widjaja-Adhi & Golczak, 2020).

Maintaining proper retinoid homeostasis is critical, as both an excess and a deficiency of vitamin A can adversely affect cells and tissues reliant on retinoid signaling (M. A. K. Widjaja-Adhi, et al., 2017). This balance is achieved through a complex system of specialized receptors, transporter proteins, and metabolic enzymes (Blaner, et al., 2016; M. A. K. Widjaja-Adhi & Golczak, 2020; Wongsiriroj & Blaner, 2015). In vision, inadequate vitamin A intake leads to night blindness and progressive retinal degeneration, a leading cause of preventable childhood blindness (Chakraborty & Chandra, 2021; Gilbert, 2013). It also contributes to anterior segment pathologies, such as dry eye symptoms, corneal ulceration, and ultimately irreversible sight damage (Chakraborty & Chandra, 2021; Fareed, et al., 2018; Gilbert, 2013). Regrettably, vitamin A deficiency remains a major global health concern, especially in low-income countries where malnutrition can be prevalent (Stevens, et al., 2015). Public health efforts to combat vitamin A deficiency, such as dietary supplementation programs and food fortification, are therefore critical for reducing the burden of vision loss globally.

To support photoreceptor function, the eye acquires retinoids from circulating lipoproteins (chylomicrons) or serum retinol-binding protein (RBP4) (Blaner, et al., 2016; von Lintig & Bandera, 2024). Chylomicrons originate in the small intestine (Dash, Xiao, Morgantini, & Lewis, 2015). These large lipoproteins contain retinyl esters (REs) derived from absorbed dietary vitamin A and its precursors. Chylomicrons deliver retinoids primarily to the liver but also to extrahepatic tissues, including the eye (D'Ambrosio, Clugston, & Blaner, 2011; Harrison, 2005). However, this lipoprotein-mediated transport is unreliable during periods of vitamin A deficiency, as it depends on immediate dietary intake. Also, chylomicrons-dependent transport lacks the cellular specificity required to prioritize vitamin A uptake in ocular tissues and does not represent a regulatory mechanism for intracellular retinoid concentration. To address these limitations, a dedicated retinoid transport mechanism has evolved, enabling the hydrolysis of REs stored in the liver and controlled distribution of the resulting all-trans-retinol (atROL) to extrahepatic tissues (Steinhoff, Lass, & Schupp, 2021). This mechanism is mediated by RBP4, the sole carrier of atROL in the bloodstream, and its specific cell membrane receptor encoded by the stimulated retinoic acid-6 gene (STRA6) (Y. Chen, et al., 2016; Kawaguchi, et al., 2007; Quadro, et al., 1999) (Fig. 2). STRA6 is predominantly expressed in tissues that form blood-organ barriers, including the choroid plexus in the brain, the RPE cells of the eye, and the placenta (Amengual, et al., 2014; Kawaguchi, et al., 2007). The cellular accessibility of atROL bound to RBP4 is tightly regulated by the expression level and activity of STRA6 (Laursen, Kashyap, Scandura, & Gudas, 2015; Zhong, et al., 2020). This receptor facilitates the interaction of holo-RBP4 with the cell surface, catalyzing the release of atROL from the carrier protein and promoting its integration into the plasma membrane (Kawaguchi, et al., 2011). Notably, STRA6 operates via a mechanism distinct from traditional cellular receptors, as its function does not involve endocytosis, energy expenditure, or reliance on cotransport systems or electrochemical gradients. Instead, STRA6 works in conjunction with two essential proteins, retinol-binding protein 1 (RBP1) and lecithin:retinol acyltransferase (LRAT), to ensure efficient atROL uptake (Chelstowska, Widjaja-Adhi, Silvaroli, & Golczak, 2016; Isken, et al., 2008; Kawaguchi, et al., 2011). Apo-RBP1 enhances STRA6 activity by increasing the cytoplasmic capacity to bind atROL and transport it to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). Meanwhile, LRAT catalyzes the phosphatidylcholine-dependent esterification of atROL, generating a mass action effect that prevents early saturation of retinoid uptake and facilitates the accumulation of REs in lipid droplets (retinosomes) in the RPE (Amengual, Golczak, Palczewski, & von Lintig, 2012; Golczak & Palczewski, 2010; Imanishi, Batten, Piston, Baehr, & Palczewski, 2004; Kawaguchi, et al., 2011) (Fig. 2). Importantly, STRA6 exhibits bidirectional functionality (Isken, et al., 2008; Kawaguchi, Zhong, Kassai, Ter-Stepanian, & Sun, 2012). In the presence of apo-RBP4, it facilitates the efflux of atROL by loading the carrier protein with the ligand (Kawaguchi, et al., 2012). Additionally, STRA6 activity is regulated by calmodulin in a Ca2+-dependent manner, which promotes atROL efflux (Kawaguchi, et al., 2012; Zhong, et al., 2020). Increased Ca2+ signaling reduces cellular vitamin A uptake, contributing to the regulation of intracellular retinoid homeostasis.

Figure 2 – Schematic representation of steps involved in the regeneration of the visual chromophore.

Enzymes are colored blue, and transport proteins are green. Abbreviations: atRAL (all-trans-retinal), 11cRAL (11-cis-retinal), atROL (all-trans-retinol), atREs (all-trans-retinyl esters), RPE (retinal pigment epithelium), and OS (photoreceptor outer segment). The canonical visual cycle occurs in RPE cells, which express key enzymes involved in this process, including LRAT, RPE65, and RDH5. RPE cells also facilitate the specific uptake of retinoids from circulation through STRA6, a receptor for RBP4. Following the photobleaching of rhodopsin, atRAL undergoes reduction to atROL, a reaction catalyzed by all-trans-retinol dehydrogenases (atRDHs), primarily RDH8 and RDH12. The resulting atROL is transported via IRBP to RPE cells, where it binds to RBP1. atROL is then esterified by LRAT to form atREs, such as all-trans-retinyl palmitate, which serves as a direct substrate for the retinol isomerase RPE65. RPE65 catalyzes the cleavage and isomerization of atREs, producing free fatty acids and 11cROL. RDH5 subsequently oxidizes 11cROL to 11cRAL, which binds to CRALBP for transport back to the OS via IRBP, completing the visual cycle and enabling rhodopsin regeneration. In addition to the classical visual cycle, the presence of RGR in the RPE and Müller cells facilitates the light-dependent (photic) visual chromophore regeneration pathway. atROL, generated from the reduction of photoisomerized visual chromophore, is shuttled from the OS of cones and rods to adjacent cells. Upon conversion to atRAL, it associates with RGR, enabling photoconversion to the 11-cis isomer. Created in BioRender (https://BioRender.com/8lgbdlk).

2.2. Carotenoids as a source of ocular vitamin A

Pro-vitamin A carotenoids are the primary source of retinoids in a balanced Western diet (Grune, et al., 2010). Unlike retinoids, their intestinal absorption and metabolism are tightly regulated by a transcriptional negative feedback mechanism influenced by vitamin A status (Lobo, et al., 2013; Lobo, et al., 2010). This regulation is achieved by coupling the concentration of RA in enterocytes with the expression of two key proteins: the multi-ligand scavenger receptor class B type 1 (SR-B1), which facilitates cellular uptake of carotenoids, and beta-carotene oxygenase 1 (BCO1), which catalyzes the cleavage of β-carotene into two molecules of atRAL (M. A. Widjaja-Adhi, Lobo, Golczak, & Von Lintig, 2015). When dietary vitamin A is abundant, elevated RA levels induce the intestine-specific homeobox transcription factor ISX. ISX binds to the promoter regions of the Bco1 and Scarb1 genes, suppressing their expression and thereby limiting carotenoid uptake and processing (M. A. Widjaja-Adhi, et al., 2015). This elegant mechanism protects against the acute toxicity of carotenoid-derived retinoids.

A portion of absorbed pro-vitamin A carotenoids remains intact and is secreted from enterocytes as a lipid component of chylomicrons (Bohn, et al., 2019; H. S. Huang & Goodman, 1965). This circulating pool of carotenoids is distributed to various tissues, including the eye. β-carotene has also been found to associate with low-density lipoproteins (LDLs), suggesting lipid exchange and carotenoid repackaging in the liver (Carroll, Corridan, & Morrissey, 2000; Ribaya-Mercado, Ordovas, & Russell, 1995). The β-carotene carried in circulating LDLs is taken up by the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) via LDL receptor–mediated endocytosis (Thomas & Harrison, 2016). Notably, BCO1 is also expressed in the RPE, allowing pro-vitamin A carotenoids to serve as a source of retinoids for visual chromophore production (Kelly, et al., 2018; von Lintig, et al., 2021). Intriguingly, studies on Stra6−/− mice supplemented with atROL or β-carotene revealed that β-carotene enhances the supply of chromophore to cone photoreceptors (Moon, Ramkumar, & von Lintig, 2023). This finding suggests potential compartmentalization of retinoid metabolism based on their source. However, the molecular mechanisms underlying this phenomenon remain to be elucidated.

2.3. RPE65-dependent visual chromophore regeneration

The light-independent biosynthesis of 11cRAL involves three subsequent enzymatic reactions that occur in the ER of the RPE cells (Fig. 2). In the first step, atROL acquired from circulation or recycled from photobleached visual chromophore is esterified by the catalytic activity of LRAT (Batten, et al., 2004; Golczak, Sears, Kiser, & Palczewski, 2015). This integral membrane protein belongs to the NipC/P60 superfamily of enzymes (Golczak, et al., 2012; Mondal, Ruiz, Hu, Bok, & Rando, 2001). It catalyzes the transfer of an acyl chain directly from phosphatidylcholine onto retinol of related substrates utilizing a Cys/His/His catalytic triad (Golczak & Palczewski, 2010; Golczak, et al., 2015; Shi, Hubacek, & Rando, 1993). The functional comparison of LRAT with its closely related paralogs, called HRAS-like tumor suppressors, revealed that LRAT is highly specific, transferring the acyl chain exclusively from the sn-1 fatty acid position in the phospholipid substrate (Golczak, et al., 2008; Golczak, et al., 2015). Moreover, unlike related enzymes, the esterase activity commonly associated with acyl transfer is not detectable for LRAT, making it a highly possessive enzyme (Golczak, et al., 2012; Golczak, et al., 2015).

The significance of LRAT activity is underscored by the fact that it provides the direct substrate for retinoid isomerase (RPE65) (Gollapalli & Rando, 2003). This key enzyme of the visual cycle catalyzes the thermodynamically unfavorable trans-to-cis isomerization of a C=C double bond (Jin, Li, Moghrabi, Sun, & Travis, 2005; Moiseyev, Chen, Takahashi, Wu, & Ma, 2005; Redmond, et al., 2005) (Fig. 2). Structurally, RPE65 belongs to the carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase (CCD) protein superfamily of non-heme iron-binding enzymes (Kiser, Golczak, Lodowski, Chance, & Palczewski, 2009; Kloer, Ruch, Al-Babili, Beyer, & Schulz, 2005). However, unlike CCDs, which catalyze the oxidative cleavage of double bonds in the conjugated carbon chain of carotenoids, RPE65 utilizes a fundamentally different mechanism for the isomerization reaction (Babino, Palczewski, et al., 2015; Kiser, et al., 2015; Sui, et al., 2015). A change in the configuration around a double bond requires destabilization of the bond order, enabling its rotation. For REs, this can be achieved by unconventional alkyl ester cleavage at the C15-O bond, which leads to the intermediate formation of a carbocation with delocalized double bond order (Kiser, et al., 2009; Law & Rando, 1988; Redmond, Poliakov, Kuo, Chander, & Gentleman, 2010). It is stabilized at the C11 position by electrostatic interactions with the side chains of Phe103 and Thr147, allowing rotation of the C11-C12 bond (Kiser, et al., 2015). The resulting cis configuration is reinforced by steric hindrance within the catalytic site, promoting the kinked shape of the retinoid moiety. The subsequent stabilization of the 11-cis isomer is achieved by a water molecule attack on carbon C15, resulting in the formation of the final 11-cis-retinol (11cROL) product (Kiser, et al., 2009; Kiser, et al., 2015).

The final step of the visual chromophore biosynthesis is the oxidation of 11cROL to the corresponding retinaldehyde, catalyzed by microsomal retinol dehydrogenases (RDHs) (A. Simon, Hellman, Wernstedt, & Eriksson, 1995) (Fig. 2). Because the redox reactions facilitated by RDHs are reversible, their net direction is determined by the substrates' availability and the enzymes' specificity for binding the universal redox cofactors, either NAD(H) or NADP(H). In eukaryotic cells, the concentration of NAD+ is one thousand times higher compared to its reduced form (NADH), whereas the NADP+/NADPH ratio is ~1:100 (Canelas, van Gulik, & Heijnen, 2008; Hedeskov, Capito, & Thams, 1987; Hung, Albeck, Tantama, & Yellen, 2011; Zhu, Lu, Lee, Ugurbil, & Chen, 2015). Thus, oxidoreductases that bind NADP(H) contribute significantly only to retinaldehyde reduction. Conversely, enzymes that prefer NAD(H) catalyze the oxidation of retinol. RDHs are also classified based on their preference for all-trans or cis-retinoid substrates. Genetic studies in mice and the phenotypic presentation of patients carrying mutations in RDH genes helped solve the complexity of these enzymes' physiological roles and identify the main contributors to the visual cycle (A. Maeda, Maeda, Imanishi, Sun, et al., 2006; A. Maeda, et al., 2007; Sergouniotis, et al., 2011). In this context, the oxidation of 11cROL in RPE cells is predominantly catalyzed by RDH5, with only minor contributions from other RDHs (RDH10 and RDH11) (Sahu & Maeda, 2016).

Overall, the light-independent biosynthesis of the visual chromophore is accomplished by the sequential action of LRAT, RPE65, and RDH5 enzymes, forming a catalytic triad. These three proteins are co-localized on the ER of RPE cells, ensuring efficient diffusion of substrates between the subsequent reactions. This physical proximity and functional interdependence might suggest the formation of a functional complex between these enzymes. Although initial biochemical data indicated co-purification and efficient lipid membrane-dependent crosslinking between RPE65 and RDH5, the isomerization complex has never been purified or reconstituted in vitro (P. Chen, Lee, & Fong, 2001; Golczak, Kiser, Lodowski, Maeda, & Palczewski, 2010).

The enzymatic machinery of the visual cycle evolved in parallel with the structural and functional adaptations of vertebrate eyes to low-light environments. The loss of the photoreversibility of vertebrate ciliary opsins enhanced the stability of the activated Meta II state and strengthened their interaction with G-proteins, increasing the overall light sensitivity (Terakita, 2005; Terakita, et al., 2004). However, it necessitated the development of an enzymatic pathway for the regeneration of 11cRAL. Comparative genetic studies on the invertebrate chordate amphioxus (Branchiostoma floridae), a representative organism of the most basal subphylum of vertebrates, revealed the absence of a vertebrate-like genetic component enabling retinoid storage, transport, or isomerization (Albalat, Brunet, Laudet, & Schubert, 2011). In fact, the earliest functional LRAT was cloned from sea lamprey (Petromyzon marinus), a jawless vertebrate (Anantharaman & Aravind, 2003; Poliakov, et al., 2012). Similarly, among the RPE65 orthologs, the first retinoid isomerization activity was reported for the enzyme cloned from sea lamprey (Poliakov, et al., 2012). Phylogenetic and structural analyses suggest that the new enzymatic activities of the visual cycle were acquired through the adaptation of duplicates of non-visual proteins into the functional machinery of the vertebrate eye (Albalat, 2012). Thus, the ability to store retinoids inside the cell and catalyze the isomerization reaction emerged following the evolutionary divergence of primitive chordates in the last common ancestor of jawless and jawed craniates.

2.4. Intra- and inter-cellular transport of retinoids

Retinoids are lipophilic molecules with limited aqueous diffusion and susceptibility to oxidative degradation. Specialized retinoid-binding proteins protect these labile molecules and enable their transport between cells and their compartments. Therefore, they are essential for connecting the distant steps of the visual cycle. In addition to RBP4, which transports atROL in the blood, three other distinct retinoid-binding proteins are involved in ocular retinoid metabolism: cellular retinol-binding protein 1 (RBP1), cellular retinaldehyde-binding protein (CRALBP), and interphotoreceptor retinoid-binding protein (IRBP) (Ghyselinck, et al., 1999; Pepperberg, et al., 1993; Saari & Crabb, 2005). These proteins belong to unrelated protein families and perform specialized functions in the visual cycle (M. A. K. Widjaja-Adhi & Golczak, 2020) (Fig. 2).

RBP1 is a lipocalin that selectively binds at-ROL or atRAL, with atROL serving as its physiological ligand (Malpeli, Stoppini, Zapponi, Folli, & Berni, 1995; Saari, Bredberg, & Garwin, 1982). As a small, soluble protein dispersed throughout the cytoplasm, its primary role is to facilitate the intracellular transport of atROL, either taken up from the serum or recycled from photoreceptors, to ER in the RPE cells (Napoli, 2000, 2017; Yost, Harrison, & Ross, 1988). Thus, RBP1 enhances the efficiency of LRAT-dependent atROL esterification. The phenotype of Rbp1−/− mice confirmed this role, as RE storage in the RPE was diminished by half compared to wild-type (WT) mice in the absence of RBP1 (Saari, et al., 2002). Consequently, a delay in atROL transport resulted in a two-fold decrease in the rate of visual chromophore regeneration following exposure to bright light in the Rbp1−/− mice (Saari, et al., 2002).

Unlike RBP1, CRALBP is a specialized retinoid carrier protein expressed only in RPE and Müller glia cells of the retina (Bunt-Milam & Saari, 1983). The presence of CRALBP in these cells reflects its critical function in supporting the biosynthesis of cis-retinoids, specifically by binding and stabilizing 11cROL and 11cRAL during their processing within the visual cycle.(Helbling, et al., 2013; Saari, et al., 1982; Saari & Crabb, 2005; Y. Sato, et al., 1993). CRALBP belongs to the CRAL-TRIO domain-containing protein family, which also includes carrier proteins for other lipophilic ligands such as tocopherol, squalene, or phosphatidylinositol (He, Lobsiger, & Stocker, 2009; Y. Sato, et al., 1993). In RPE cells, CRALBP plays a critical role by sequestering 11cRAL resulting from the enzymatic actions of the LRAT/RPE65/RDH5 triad, thus increasing the overall rate of the isomerization reaction (Bassetto, et al., 2024; Saari, et al., 2001). This binding stabilizes the newly formed chromophore, shielding it from thermal re-isomerization or side reactions involving its reactive aldehyde group. CRALBP also facilitates efficient transport of 11cRAL to the plasma membrane for subsequent delivery to photoreceptors. Evidence from in vivo studies underscores the importance of CRALBP in visual chromophore regeneration. While Rlbp1−/− mice do not exhibit spontaneous retinal degeneration, their ability to regenerate the visual chromophore after light exposure is significantly impaired, with a regeneration rate ten times slower than that of WT mice (Bassetto, et al., 2024; Burstedt, Sandgren, Holmgren, & Forsman-Semb, 1999; Maw, et al., 1997). The impact of CRALBP deficiency on cone photoreceptors is more subtle, highlighting our incomplete understanding of the cone-specific chromophore regeneration process (described in chapter 3) (Ala-Laurila, Cornwall, Crouch, & Kono, 2009; S. Sato & Kefalov, 2016; Xue, et al., 2015).

The process of diffusion of the visual chromophore between RPE and photoreceptor cells, as well as its distribution within the outer segments, is not fully understood. It requires dissociating the 11cRAL molecule from CRALBP and transferring it across two plasma membranes and the intercellular matrix (Fig. 2). The protein that facilitates this process is a relatively large glycoprotein, expressed in photoreceptors and secreted into the interphotoreceptor space, called IRBP (Pepperberg, et al., 1993). This multifunctional lipid carrier exhibits broad specificity toward retinoids and their geometric isomers (Y. Chen & Noy, 1994). It also interacts with non-retinoid molecules, including polyunsaturated fatty acids (Y. Chen, Houghton, Brenna, & Noy, 1996; Lin, et al., 1997). IRBP is believed to contribute to both the transport of 11cRAL to the outer segments and the channeling of photo-isomerized atROL back to RPE cells for enzymatic re-isomerization. Early biochemical and recent electron microscopy data indicate that the protein folds into four distinct modules of significant homology (Gonzalez-Fernandez, Baer, & Ghosh, 2007; Sears, et al., 2020). The polypeptide chain adopts a flexible, elongated shape that undergoes conformational rearrangement upon saturation with atROL. Each module represents a functional unit; as three to four independent binding sites have been postulated within the IRBP molecule. Deactivation of the Irbp gene in mice led to a progressive loss of rod photoreceptors and changes in the organization of their outer segments (Jin, et al., 2009; Palczewski, et al., 1999; Ripps, et al., 2000). However, the absence of IRBP did not cause abnormalities in dark adaptation, as the rate of visual chromophore recovery was faster compared to WT mice. These findings add complexity to the understanding of IRBP's role in ocular retinoid homeostasis.

2.5. Clearance of all-trans-retinal

The decay of photoactivated visual pigments results in the hydrolysis of the retinylidene Schiff base bond and releasing atRAL from the protein scaffold into the outer segment disk membrane (Fig. 2). While atRAL is crucial for conjugation with opsins, its aldehyde group is chemically reactive and associated with cytotoxicity in biological systems. The electrophilic nature of the carbonyl carbon makes atRAL prone to forming adducts with primary amines and thiol groups of phospholipids and proteins, leading to detrimental changes in cellular function.

Under high illumination, the retina experiences a significant flux of retinoids, resulting in elevated concentrations of atRAL. To mitigate its toxic effects, atRAL must be efficiently cleared by reduction to less reactive atROL. This reaction is catalyzed by all-trans-retinol dehydrogenases (all-trans-RDHs), predominantly RDH8 in mice and RDH12 in the human retina (Haeseleer, et al., 2002; Janecke, et al., 2004; A. Maeda, et al., 2005; Palczewski, et al., 1994; Rattner, Smallwood, & Nathans, 2000). These enzymes, localized on the cytoplasmic side of the outer segment disk membrane, can only access atRAL in the cytoplasmic leaflet of the phospholipid bilayer. Consequently, atRAL molecules partitioned into the luminal leaflet of the membrane are not readily reduced. Their clearance is further impeded by forming an adduct between atRAL and phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), producing N-retinylidene-phosphatidylethanolamine (N-ret-PE) (Anderson & Maude, 1970). This adduct cannot freely flip between the inner and outer leaflets of the lipid bilayer. Although the Schiff base bond of N-ret-PE is susceptible to hydrolysis, its transient accumulation allows subsequent reaction with additional atRAL molecules, initiating a cascade of irreversible non-enzymatic conversions that lead to the synthesis of fluorescent bis-retinoids, including pyridinium bis-retinoid (A2E) and retinal dimer (RALdi), characterized by multifaceted cytotoxicity (discussed in more details in paragraph 4.2) (Eldred & Lasky, 1993; H. J. Kim & Sparrow, 2021; S. R. Kim, et al., 2007; Parish, Hashimoto, Nakanishi, Dillon, & Sparrow, 1998).

To prevent the formation of these cytotoxic byproducts, N-ret-PE is transported by the retina-specific ATP-binding cassette transporter 4 (ABCA4) (Quazi, Lenevich, & Molday, 2012; Quazi & Molday, 2014). ABCA4 facilitates the translocation of N-ret-PE from the luminal to the cytoplasmic side of the disk membrane, where it undergoes hydrolysis and subsequent reduction to atROL (Fig. 2). The physiological importance of ABCA4 is highlighted by retinal degenerative diseases caused by loss-of-function mutations in the ABCA4 gene, collectively known as Stargardt disease type 1 (STGD1) (Al-Khuzaei, et al., 2021; Cremers, Lee, Collin, & Allikmets, 2020). This condition is characterized by progressive central vision loss and the presence of fluorescent lipofuscin deposits in the RPE (Burke, et al., 2014; Delori, Dorey, et al., 1995; Fakin, et al., 2016; Schmitz-Valckenberg, et al., 2021). The spectral properties of lipofuscin are attributed to atRAL conjugation products, predominantly A2E, as well as other bis-retinoids (Haralampus-Grynaviski, et al., 2003; L. E. Lamb & Simon, 2004). Therefore, ABCA4 is essential for reducing atRAL concentrations below cytotoxic thresholds, thereby protecting photoreceptor cells. Additionally, ABCA4 minimizes the availability of atRAL for bis-retinoid formation, mitigating the production of harmful byproducts implicated in retinal degeneration.

3. Photic regeneration of 11-cis-retinal

The RPE65-dependent regeneration of 11cRAL supports the function of both rod and cone photoreceptors (Feathers, et al., 2008; Jacobson, et al., 2007; Seeliger, et al., 2001). However, several lines of evidence indicate the presence of alternative pathways for visual chromophore acquisition. The first is the biphasic recovery of light sensitivity observed in humans and other animals, where cone visual pigments regenerate several times faster than rhodopsin (T. D. Lamb & Pugh, 2004, 2006). Additionally, cone signaling does not saturate under normal conditions and continues to respond to changes in light intensity even under very bright light (T. D. Lamb, 2016). This phenomenon arises from the adaptation of phototransduction signaling and a potential faster than the enzymatic light-independent mechanism for visual chromophore regeneration (Matthews, Murphy, Fain, & Lamb, 1988; Nakatani & Yau, 1988; Vinberg & Kefalov, 2018; Vinberg, Peshenko, Chen, Dizhoor, & Kefalov, 2018). An alternative explanation for the kinetics of cone pigment regeneration is the existence of a readily available reservoir of 11-cis retinoids or a cone-specific re-isomerization reaction. Supporting this hypothesis is the presence of 11-cis-retinyl esters (11cREs) in the eyes of diurnal species such as zebrafish, chickens, ground squirrels, primates, and humans (Babino, Perkins, Kindermann, Oberhauser, & von Lintig, 2015; Blaner, Das, Gouras, & Flood, 1987; Das, Bhardwaj, Kjeldbye, & Gouras, 1992; Mata, Radu, Clemmons, & Travis, 2002; Mustafi, et al., 2016; Rodriguez & Tsin, 1989). In contrast, 11cREs are undetectable in rod-dominated nocturnal rodents (Mustafi, et al., 2016; Palczewski, et al., 1999; Saari, et al., 2002). Moreover, retinas separated from RPE cells retain their ability to synthesize 11cRAL (Goldstein, 1970). In the absence of RPE65 expression in the retina, this observation suggests an independent mechanism for retinoid isomerization with Müller glia cells playing a central role in this process. These specialized retinal cells express cis isomer-specific CRALBP (Bassetto, et al., 2024; Bunt-Milam & Saari, 1983). Additionally, cones and Müller glia cells contain oxidoreductases that catalyze the conversion of 11cROL into their corresponding aldehydes, an essential step in chromophore biosynthesis (Ala-Laurila, et al., 2009; Das, et al., 1992; Kaylor, et al., 2014; Morshedian, et al., 2019; S. Sato, Frederiksen, Cornwall, & Kefalov, 2017). Another enzymatic activity detected in Müller glia cells is the esterification of 11cROL which is independent of LRAT activity (Kaylor, et al., 2014). This reaction was proposed to create a reservoir of 11cREs, which can be rapidly mobilized to meet the high demand for chromophore regeneration in cone photoreceptors. Collectively, these molecular components establish a biochemical framework for an alternative, cone-specific visual cycle that operates independently of the RPE65-driven classical pathway.

This retina-based visual cycle was suggested to sustain vision under high light conditions by ensuring rapid regeneration of cone visual pigments, thereby supporting the distinct functional demands of cone photoreceptors. Based on these findings, several evolving models for the cone-specific visual cycle have been proposed. Subsequent biochemical and genetic validation of these models over the last decades has advanced our understanding of the retina-based production of 11cRAL (S. Sato & Kefalov, 2024).

3.1. Photochemical isomerization of retinoid

The spectroscopic properties of retinoids are intrinsically linked to their conjugated double-bond system. The delocalization of π-electrons across the polyene chain provides resonance stabilization, imparting partial double-bond character to single bonds and favoring a planar conformation (Rowan, Warshel, Sykes, & Karplus, 1974). As a result, the all-trans configuration represents the most stable conformation due to its minimal steric hindrance. In contrast, alternative geometric isomers introduce steric clashes between specific hydrogen atoms, leading to increased conformational energy (Hubbard, 1966; Mertz, Lu, Brown, & Feller, 2011). For example, isomers such as 11-cis and 7-cis experience significant steric strain, disrupting the planar structure of the polyene chain (López-Castillo & Borin, 2010).

Thermal or photonic energy can induce the isomerization of retinoids, resulting in an equilibrium between various geometric isomers (Kiser, et al., 2014; Rando & Chang, 1983). Notably, the composition of isomers at photoequilibrium is influenced by the reaction conditions. While non-polar solvents like hexane favor a limited range of isomers, polar solvents such as ethanol or acetonitrile promote the formation of physiologically relevant 9-cis and 11-cis isomers, with these isomers comprising up to ~25% of the total (Arne, et al., 2017; Deval & Singh, 1988). Although the mixture of isomers produced through photochemical methods does not fully replicate the equilibrium observed in ocular tissues, photochemical regeneration has been proposed as a potential mechanism for generating the visual chromophore via a phospholipid intermediate. In this pathway, atRAL released from bleached visual pigments forms a reversible Schiff base adduct with PE, yielding N-ret-PE. When protonated, all-trans-N-ret-PE absorbs blue light (~450 nm) and is converted with high specificity to 11-cis-N-ret-PE (Groenendijk, Jacobs, Bonting, & Daemen, 1980; Shichi & Somers, 1974). Remarkably, the calculated quantum yield of this photoisomerization is comparable to that of rhodopsin, suggesting that this reaction may serve as a significant alternative source of 11cRAL under photic conditions (Suzuki & Callender, 1981). Supporting this hypothesis, mice exposed to 450 nm light prior to photobleaching exhibited accelerated rhodopsin regeneration compared to mice kept in darkness (Kaylor, et al., 2017). However, the overall physiological relevance of this process remains contentious, as non-enzymatic production of the visual chromophore cannot compensate for the loss of RPE65 or other critical enzymes in the canonical visual cycle, underscoring the importance of enzymatic pathways in sustaining vision.

3.2. RGR-mediated light isomerization

Early hypotheses about the mechanisms of visual cycle biosynthesis in vertebrates proposed an evolutionarily conserved, light-dependent retinoid isomerization process, facilitated by proteins related to invertebrate photoreversal opsins (Hara & Hara, 1967; Hubbard & Wald, 1952). The first evidence supporting this hypothesis came from the identification of retinal G protein-coupled receptor (RGR) as an opsin capable of catalyzing photoisomerization (Hao, Chen, & Fong, 2000). Although RGR does not signal through G-proteins, it shares a conserved feature with visual opsins, enabling formation of a Schiff base bond with retinaldehydes (P. Chen, Hao, et al., 2001). RGR preferentially binds atRAL in the dark. Upon exposure to visible light, photon absorption generates an excited state of the retinylidene adduct, facilitating C11-C12 double bond rotation (P. Chen, Hao, et al., 2001; Morshedian, et al., 2019). The action spectrum, with a broad maximum between 503 and 535 nm, suggests that isomerization occurs in the protonated state of the retinylidene Schiff base (Morshedian, et al., 2019). The resulting 11-cis-retinylidene is unstable within RGR’s binding pocket and undergoes hydrolysis, liberating 11cRAL. The binding of the newly formed chromophore by CRALBP significantly accelerates RGR-catalyzed photoisomerization (J. Zhang, et al., 2019) (Fig. 2).

RGR is expressed in both RPE and a subset of Müller glia cells (Jiang, Pandey, & Fong, 1993; Pandey, Blanks, Spee, Jiang, & Fong, 1994; Tworak, et al., 2023). Its localization in these cell types suggests distinct roles in retinal physiology for rods and cones, respectively. Recent studies in conditional knockout mice with selective deletion of the Rgr gene revealed that RGR in the RPE supports both rod and cone pigment regeneration under bright light conditions (Tworak, et al., 2023). Conversely, the absence of RGR in Müller cells only partially suppresses cone function under bright light and moderately reduces the rate of cone dark adaptation. Similar conclusions were drawn from cell-specific knockout studies of the Rblp1 gene encoding CRALBP (Bassetto, et al., 2024). RPE-specific deletion of CRALBP slowed 11cRAL regeneration by 15-fold, significantly affecting cone pigment regeneration, while its absence in Müller cells had only mild effects. These findings underscore the dominant role of RPE in supplying rods and cones with visual chromophore (Fig. 2).

Photic regeneration by RGR contributes measurably to chromophore regeneration, enabling continuous light sensitivity under bright light conditions. However, its overall significance remains controversial. Since RGR is not present in photoreceptors, it remains unclear how it acquires a sufficient amount of atRAL substrate. After dissociating from opsins, atRAL is reduced to atROL by all-trans RDHs (RDH12 and RDH8). Excess atRAL, which cannot be readily metabolized, forms N-ret-PE, a non-diffusible intermediate, while atROL is released extracellularly for uptake by RPE and Müller cells. Oxidation back to atRAL is required for RGR-dependent photoisomerization. In RPE cells, LRAT readily esterifies atROL to provide substrates for RPE65. Furthermore, RDH5 in the RPE mainly processes cis-retinoids, whereas RDH11 exhibits dual specificity but favors reduction reactions. These processes diminish the concentration of atRAL in the RPE cells to undetectable levels. In Müller cells, it has been proposed that RDH10 and RGR form a catalytic tandem, wherein RDH10 re-oxidizes atROL to supply substrate for RGR and subsequently reduces newly formed 11cRAL to 11cROL for transfer back to cone photoreceptors (Kaylor, et al., 2024; Morshedian, et al., 2019). However, this scenario conflicts with the homeostatic ~100-fold abundance of NADPH over NADP+ in eukaryotic cells, which strongly favors the reduction reaction. Moreover, unlike deficiencies in the canonical visual cycle, which are associated with well-characterized and prevalent retinal degenerative diseases (Table 1), the significance of RGR-mediated photic regeneration lacks strong genetic confirmation in humans. Initial reports linking RGR mutations to retinal dystrophy were confounded by coexisting mutations in the CDHR1 gene, known to independently cause retinal degeneration (Arno, et al., 2016; Morimura, Saindelle-Ribeaudeau, Berson, & Dryja, 1999). Genetic screening of retinitis pigmentosa (RP) patients of Spanish origin revealed no disease-causing mutations in RGR (Bernal, et al., 2003). Isolated cases of slowly progressing, familial retinopathy were reported in heterozygous carriers of frameshift mutations, but their clinical manifestations ranged from asymptomatic to moderate rod-cone dystrophies, suggesting incomplete penetrance (Ba-Abbad, et al., 2018).

Table 1 –

Phenotypic and pathological effect of mutation in genes involved in regeneration of visual chromophore

| Strain | Phenotypes in Mice | Pathologies in Humans |

|---|---|---|

| Retinol dehydrogenases | ||

| Rdh5 −/− | Thin inner and outer nuclear layer (Y. Xie, et al., 2020) Accumulation of 13-cis-retinyl esters (A. Maeda, Maeda, Imanishi, Golczak, et al., 2006) |

Fundus albipunctatus (Skorczyk-Werner, et al., 2015) Reduced RPE cell size, night blindness, flecked retina (Sergouniotis, et al., 2011) |

| Rdh8 −/− | Accumulation of atRAL after bleaching, delayed rod response recovery after bleaching, accelerated accumulation of A2E (A. Maeda, et al., 2005) (A. Maeda, Golczak, Maeda, & Palczewski, 2009) | Perifoveal and peripheral flecks as well subretinal deposits in the foveal region with thinning of the outer nuclear layer (Zampatti, et al., 2023) |

| RDH10 −/− | Embryonic lethality (Sandell, et al., 2007) | No known phenotypes |

| Rdh10−/− (cKO in Muller cells, cones, or entire retina) | Normal cone ERG responses and dark adaptation kinetics (Xue, et al., 2017) | N/A |

| Rdh10−/− (cKO in RPE cells) | Delayed 11cRAL regeneration, delayed post-bleach rod ERG recovery (Sahu, et al., 2015) | N/A |

| Rdh11 −/− | Delayed post-bleach rod ERG recovery (Kasus-Jacobi, et al., 2005) Normal post-bleach retinoid recovery in eye and dark-adapted retinoid content in the eye (T. S. Kim, et al., 2005) |

Retinitis pigmentosa, ERG dysfunction of rods and cones, “salt and pepper” retinopathy, and mottled macula at young age (Y. A. Xie, et al., 2014) |

| Rdh12 −/− | Delayed clearance of atRAL, increased accumulation of A2E, delayed dark rod adaptation, light-induced photoreceptor apoptosis (A. Maeda, Maeda, Imanishi, Sun, et al., 2006) | Early-onset severe retinal dystrophy, reduced rod and cone ERG responses, coloboma-like macular atrophy (Varela & Michaelides, 2022) |

| Acyltransferases | ||

| Lrat −/− | Absence of retinoids in RPE and retina, severely attenuated rod and cone responses and progressive retinal degeneration (Batten, et al., 2004) | Leber Congenital Amaurosis (Dev Borman, et al., 2012) (Senechal, et al., 2006) Retinitis Pigmentosa (Y. Chen, et al., 2018) |

| Awat2 −/− | Suppressed cone dark adaptation, normal rod dark adaptation (M. A. K. Widjaja-Adhi, et al., 2022) | No known phenotypes |

| Isomerases | ||

| Rpe65 −/− | Lack biosynthesis of 11cRAL, accumulation of REs, severe attenuation of rod and cone function, disorganized rod outer segment discs (Redmond, et al., 1998) | Leber Congenital Amaurosis, severe attenuation of ERG responses, RPE atrophy (Gu, et al., 1997; Marlhens, et al., 1997) Rod-cone dystrophy (Lorenz, et al., 2000) |

| Rgr −/− | Diminished fast phase of cone regeneration loss under continuous light illumination (Morshedian, et al., 2019; Tworak, et al., 2023) | Needs determination |

| Retinoid-binding proteins | ||

| Rlbp−/− (Cralbp−/−) | Lower 11cRAL and 11cROL levels and slower 11cRAL regeneration, post-bleach accumulation of atREs, less A2E accumulation (Lima de Carvalho, et al., 2020) Over 10-fold delay in post-bleach dark adaptation (Saari, et al., 2001) Lower cone ERG sensitivity, M-opsin mislocalization, and lower density of M-cones (Kolesnikov, Kiser, Palczewski, & Kefalov, 2021; Xue, et al., 2015) |

Delayed dark adaptation, RPE atrophy, reduced ERG signal, retinitis punctate albescens (Morimura, Berson, et al., 1999) Bothnia dystrophy (Burstedt, et al., 1999) |

| Irbp −/− | Slower rate of retinoid transport between the retina and RPE (Jin, et al., 2009) Reduced cone ERG responses (Parker, Fan, Nickerson, Liou, & Crouch, 2009) Photoreceptor degeneration (Liou, et al., 1998) |

Autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa (den Hollander, et al., 2009) Retinal dystrophy and myopia, thinning of the central macula, loss of inner segment ellipsoid band, delayed cone ERG response (Arno, et al., 2015) |

| Rbp1 −/− | Reduced concentration of REs in the RPE, delayed rods dark adaptation (Saari, et al., 2001) | No known phenotypes |

| Rbp4 −/− | Impaired retinal function and visual acuity on vitamin A deficient diet (Quadro, et al., 1999) | Anophthalmia, iris or chorioretinal colobomas, reduced atROL levels (Chou, et al., 2015) |

| Receptors and transporters | ||

| Stra6 −/− | Reduced levels of ocular retinoids, attenuated ERG responses, reduced lengths of rod outer segments (Amengual, et al., 2014) Decreased number of cone photoreceptors, densely vascularized vitreous (Ruiz, et al., 2012) |

Matthew-Wood Syndrome, microphthalmia or anophthalmia (Golzio, et al., 2007) |

| Abca4 −/− | Decreased clearance of atRAL, accumulation of A2E, progressive photoreceptor degeneration, delayed dark adaptation post-photobleach (Mata, Weng, & Travis, 2000; Weng, et al., 1999) | Stargardt Disease, degeneration of photoreceptor and RPE, delayed dark adaptation (Allikmets, et al., 1997; Nasonkin, et al., 1998) Accumulation of lipofuscin (Cideciyan, et al., 2004) |

| Rho −/− | Failure to form rod outer segments, no rod ERG signal, progressive degeneration of cones (Humphries, et al., 1997; Lem, et al., 1999) | Retinitis Pigmentosa, (Farrar, et al., 1990) Rod photoreceptor degeneration, secondary cone photoreceptor degeneration, night blindness (Cideciyan, et al., 1998; Gal, ApfelstedtSylla, Janecke, & Zrenner, 1997) |

4. Retinal diseases related to the impaired regeneration of the visual cycle

The critical role of adequate visual chromophore regeneration in light perception and retinal health is highlighted by the occurrence of blinding diseases associated with abnormalities in the visual cycle (Table 1). Mutations in many genes encoding proteins involved in the 11cRAL regeneration pathway have been identified as a major cause of various spontaneous and inherited retinal dystrophies, including Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA), rod-cone dystrophies, RP, and STGD1 (Fig. 3). In numerous cases, the genetic basis of these retinal diseases has facilitated the discovery and functional characterization of key proteins involved in retinoid metabolism in the eye. Retinal diseases stemming from visual cycle defects can generally be categorized into two groups: i) retinopathies associated with metabolic blockages in the biosynthesis of the visual chromophore and ii) retinopathies caused by inadequate clearance of atRAL and its toxic byproducts.

Figure 3 – Pathogenic mutations in proteins involved in the visual cycle.

The complexity of the retinoid isomerization metabolic pathway contributes to the diversity of inherited retinal diseases caused by inactivating mutations in its molecular components. Specific diseases associated with particular proteins are abbreviated and highlighted in red, including Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA), retinitis pigmentosa (RP), age-related macular degeneration (AMD), Stargardt disease type 1 (STGD1), FA, rod dystrophy (RD), congenital stationary night blindness (CSNB), Matthew-Wood syndrome (MWS), and Bothnia dystrophy (BD). Molecules that can be pharmacologically targeted to treat some of these diseases are highlighted in green. Created in part with BioRender (https://BioRender.com/6m2flsr).

4.1. Deficiencies in the biosynthesis of the visual chromophore

Loss-of-function mutations in the RPE65 gene severely impair the biosynthesis of 11cRAL. This deficiency results in the absence of functional visual pigment, leading to a spectrum of retinal dystrophies (Gu, et al., 1997; Marlhens, et al., 1997; Morimura, et al., 1998) (Table 1). Depending on the age of onset and the methods used for diagnosis, these conditions are classified as LCA, early-onset severe retinal dystrophy, or early-onset RP (Fig. 3). To date, over 200 specific mutations of varying types have been linked to RPE65-related retinal dystrophies (The Human Gene Mutation Database). These mutations are distributed relatively evenly across the amino acid sequence of the protein (Kiser, 2022). In addition to large truncations and mutations within the catalytic site, the β-propeller structure of RPE65 is intrinsically sensitive to mutation-induced misfolding or conformational instability. This structural vulnerability exacerbates the pathogenic impact of many mutations. Interestingly, phenotypic analysis of patients with biallelic RPE65 mutations shows a relatively uniform clinical presentation, regardless of mutation type, indicating that most missense mutations result in complete loss of function. However, a subset of patients carrying specific RPE65 variants exhibit near-normal visual acuity during early childhood. In these cases, visual function remains stable throughout the first decade of life but shows a clinically significant decline in the second decade, with rapid deterioration occurring after the age of 20 (Chung, et al., 2019). Thus, certain RPE65 mutations retain partial isomerization activity, which may delay disease progression.

The majority of pathogenic RPE65 mutations are inherited in an autosomal recessive manner. An exception to this rule is the Asp477Gly substitution, which causes deleterious protein aggregation (Bowne, et al., 2011; Choi, et al., 2018; Hull, Mukherjee, Holder, Moore, & Webster, 2016). This aggregation disrupts the function of the WT enzyme, resulting in a dominant-negative effect and autosomal dominant inheritance. RPE65-related retinopathies account for approximately 8% of all LCA cases and 2% of RP, classifying them as rare diseases (Testa, et al., 2024).

Mutations in the LRAT gene also cause severe disruptions in retinoid metabolism, particularly the visual cycle (Batten, et al., 2004; O'Byrne, et al., 2005). Loss-of-function LRAT mutations hinder REs formation, leading to chronic retinoid deficiency and the prolonged absence of the visual chromophore (Batten, et al., 2004; Koster, et al., 2021) (Table 1). This dysfunction also limits the accessibility of RPE65 to its substrate, further compounding the metabolic blockade of the visual cycle (Fig. 3).

Vision-related symptoms of LRAT deficiency typically become apparent between two months and three years of age in otherwise healthy patients. Key features include severe impairment in low-light vision, progressive deterioration of color vision, and constriction of the visual field (Y. Chen, et al., 2018; Dev Borman, et al., 2012; Senechal, et al., 2006; Thompson, et al., 2001). The functional deficits are accompanied by advancing morphological changes, such as bilateral atrophy of the RPE, attenuation of retinal arterioles, and foveal and optic nerve atrophy. These anatomical changes usually become evident by the second decade of life, correlating with the progression of visual impairment. The inheritance pattern of LRAT-related retinal dystrophies is autosomal recessive. Unlike RPE65, there are no known dominant mutations in LRAT. The lack of functional LRAT activity disrupts both retinoid storage and recycling, underscoring its critical role in sustaining normal visual function and retinoid homeostasis.

Although RDH5 gene inactivation does not stop visual chromophore regeneration, it significantly impairs and slows the process (Cideciyan, et al., 2000). Consequently, mutations that result in the loss of RDH5 function are associated with autosomal recessive fundus albipunctatus (FA), a rare form of night blindness in humans characterized by numerous small, white, or yellowish deposits scattered across the RPE and a relatively well-preserved retinal structure in early stages of the disease (Yamamoto, et al., 1999) (Fig. 3). The delayed recovery of rod function after exposure to bright light reflects the impaired recycling of 11cRAL and the role of RDH5 in the putative retinoid isomerization complex (A. Simon, et al., 1995) (Table 1). While typically less severe than the effects of LRAT or RPE65 deficiencies, the ocular symptoms in some patients with RDH5 inactivation progress beyond night blindness to include cone dystrophy, characterized by a gradual loss of central vision, impaired color discrimination, and photophobia (Nakamura, Hotta, Tanikawa, Terasaki, & Miyake, 2000). The phenotypic variability of the disease may be influenced by environmental factors, such as light exposure, and by specific genetic variants of RDH5.

A diminished rate of visual chromophore regeneration is also observed in patients with pathological mutations in the RLBP1 gene, which encodes CRALBP. The clinical manifestations of rod-cone disorders associated with the loss-of-function of this 11cRAL-binding protein include conditions such as RP, retinitis punctata albescens, FA, and Bothnia dystrophy (Burstedt, et al., 1999; Morimura, Berson, & Dryja, 1999) (Fig. 3). Despite this variability, a common phenotypic hallmark is severe night blindness caused by prolonged dark adaptation (Table 1). This is often accompanied by peripheral visual field defects and significantly reduced electrophysiological responses (Burstedt, et al., 1999; Hipp, et al., 2015; Lima de Carvalho, et al., 2020). Notably, macular function, responsible for central vision, varies considerably among affected patients. While some exhibit relatively preserved central vision, a subset experiences markedly reduced visual acuity and color blindness (Hipp, et al., 2015).

The analysis of clinical outcomes stemming from mutations in proteins involved in the biosynthesis of 11cRAL not only provides genetic confirmation of their physiological roles but also offers valuable insights into the molecular mechanisms of retinoid metabolism in the eye. However, the observation that mutations in the same gene can lead to diverse retinal disorders underscores a more complex interplay of molecular and cellular adaptations to factors such as light exposure, aging, and underlying genetic background. This complexity highlights the need for further research to unravel the environmental and physiological contributors to these phenotypic variations.

4.2. Retinopathies related to altered clearance of all-trans-retinal

Robust regeneration of the visual chromophore alone does not ensure retinal health and function. Equally essential is the proper maintenance of retinoid homeostasis along metabolic pathways to support the health of photoreceptors and RPE cells. A clinical example of this importance is found in retinopathies associated with the insufficient clearance of atRAL, a byproduct of the photobleaching of visual pigments.

As discussed in section 2.5, the low steady-state concentration of atRAL is maintained through the tandem activity of the photoreceptor-specific ABCA4 transporter and all-trans-RDHs. ABCA4, a large (~260 kDa) transmembrane protein, consists of two non-identical halves arranged in a multi-domain architecture (Bungert, Molday, & Molday, 2001; Scortecci, et al., 2021; T. Xie, Zhang, Fang, Du, & Gong, 2021). Using energy from ATP hydrolysis, ABCA4 transports its preferred substrate, N-ret-PE, across disc lipid membrane leaflets of the outer segments (Molday, 2015). This activity enhances the access of RHDs to atRAL, ensuring its efficient reduction to atROL. Unlike many RDHs, ABCA4’s activity is not redundant. Moreover, the size and structural complexity make this transporter particularly susceptible to activity-altering mutations, with clinical manifestations diagnosed as STGD1 (Allikmets, 1997; Hanany, Rivolta, & Sharon, 2020) (Fig. 3).

The estimated prevalence of STGD1 is approximately 1 in 6,500 to 1 in 10,000 individuals globally, making it the most common inherited macular dystrophy in children and adults (Hanany, et al., 2020; Michaelides, Hunt, & Moore, 2003). The etiology of STGD1 includes delayed clearance of atRAL and the subsequent formation and accumulation of cytotoxic bis-retinoids, within photoreceptors and the RPE. Thus, a hallmark feature of the disease includes fluorescent flecks observed in fundus imaging, indicative of A2E over accumulation (Burke, et al., 2014; Delori, Staurenghi, et al., 1995). STGD1 typically manifests during childhood or adolescence, although late-onset forms have been reported (Lambertus, et al., 2015). Patients commonly present with progressive central vision loss, difficulty seeing in dim light, and sometimes color vision deficits (Fakin, et al., 2016). Peripheral vision is usually preserved in the early stages (Abalem, et al., 2017).

Bis-retinoids like A2E serve as biomarkers for elevated atRAL levels in photoreceptor cells but also exert significant cytotoxic effects. Once formed, A2E is remarkably stable and accumulates progressively in the RPE cells (Ben-Shabat, et al., 2002; J. Liu, Itagaki, Ben-Shabat, Nakanishi, & Sparrow, 2000). Its deposition disrupts lysosomal protein degradation and phagocytic functions in the RPE (Finnemann, Leung, & Rodriguez-Boulan, 2002; Holz, et al., 1999; Pan, et al., 2021). Additionally, A2E impairs mitochondrial function, reducing cell viability (Schutt, et al., 2007). Oxidation products of A2E can activate the complement system, triggering chronic inflammation (Zhou, Kim, Westlund, & Sparrow, 2009). Another atRAL condensation product, RALdi, exhibits high chemical and photo reactivity. Consequently, sensitization of the RPE to blue light is primarily attributed to RALdi (S. R. Kim, et al., 2007; J. Zhao, et al., 2017). Its reactive aldehyde group and photocleavage products, such as methylglyoxal and glyoxal, crosslink proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids, exacerbating cytotoxic damage (Yoon, Yamamoto, Ueda, Zhou, & Sparrow, 2012). Notably, a similar accumulation of aberrant retinoid metabolites is characteristic of inactivating mutations in the RDH12 gene, which also results in delayed clearance of atRAL (Aleman, et al., 2018; Muthiah, et al., 2022). However, the prevalence of RDH12 mutations is much lower than that of ABCA4 mutations.

Importantly, even in the presence of a fully functional retinoid cycle, atRAL condensation products accumulate with age (Guan, et al., 2020; Sparrow, et al., 2012). Although these byproducts may not be the primary cause of age-related macular degeneration (AMD), their accumulation is hypothesized to be a contributing risk factor for AMD progression. This is supported by observations of atrophic lesions in areas of increased fundus fluorescence (Holz, Bellman, Staudt, Schutt, & Volcker, 2001).

These examples underscore the significance of retinoid homeostasis for photoreceptor and RPE health. They suggest that imbalances in retinoid metabolism play a key etiological role in retinal degenerative diseases, highlighting the need for further research into therapeutic strategies targeting these pathways.

5. Therapeutic strategies for the treatment of retinopathies involving visual cycle

Efficient treatments for retinal blinding diseases remain an unmet medical need. Over the past two decades, significant efforts have been dedicated to developing, testing, and implementing therapeutic strategies aimed at curing or slowing the progression of these debilitating conditions. These strategies encompass a diverse array of approaches, including traditional small-molecule drugs and innovative genetic therapies, all designed to preserve or restore vision.

5.1. Small molecule drug candidates targeting the visual cycle

Traditional pharmacological interventions usually offer safe and cost-effective treatment options that are globally accessible to address the needs of large and diverse groups of patients. Moreover, small-molecule drugs can be used in combination with other treatments to enhance efficacy or address multiple disease mechanisms simultaneously. Thus, while traditional pharmacological treatments may not always offer a cure, they provide effective management options for many retinal diseases. Thus, their accessibility, affordability, and versatility make them an essential component of the therapeutic landscape.

5.1.1. Visual chromophore replacement therapy

The loss of LRAT or RPE65 protein function results in the absence of visual pigments and light sensitivity, ultimately leading to progressive retinal degeneration (Fan, Rohrer, Frederick, Baehr, & Crouch, 2008). This degeneration is exacerbated by the partial but constitutive activity of unligated opsins and their mistrafficking (Woodruff, et al., 2003). Although the absence of the visual chromophore becomes apparent shortly after birth, the degenerative process of the retina progresses relatively slowly, often over several years, providing a critical window for therapeutic intervention.

To compensate for the absence of 11cRAL, pharmacological strategies aim to bypass the visual cycle blockage by supplementing artificial visual chromophores (Fig. 4A). Both 11-cis and 9-cis-retinal (9cRAL) can bind to visual opsins; however, the latter isomer was chosen for therapeutic use due to its higher thermal stability (Fan, Rohrer, Moiseyev, Ma, & Crouch, 2003; Fukada, et al., 1990; Wald, Brown, Hubbard, & Oroshnik, 1955). Initial experiments with 9cRAL supplementation in Rpe65-deficient mice demonstrated remarkable results. Oral gavage with 9cRAL led to the formation of rod photopigments (iso-rhodopsin) and substantial improvement in rod function within 48 hours (Van Hooser, et al., 2000). To mitigate potential toxicity associated with the aldehyde form of the chromophore, 9-cis retinoids can be delivered as inactive prodrugs, such as 9-cis-retinyl acetate (9cRAc). These esterified prodrugs leverage pre-existing dietary retinoid absorption and distribution mechanisms. In the small intestine, 9cRAc undergoes hydrolysis and re-esterification with fatty acyl-coenzyme A (primarily palmitate) before being transported via chylomicrons to the liver and other tissues. In the eye, 9-cis-retinyl esters are hydrolyzed again as they pass from the choroid capillaries into the RPE. Importantly, in the presence of active LRAT, 9-cis-retinol is preferentially stored in lipid droplets known as retinosomes within RPE cells (Imanishi, Gerke, & Palczewski, 2004). These droplets provide a long-lasting reservoir of 9-cis retinoids that can be mobilized and oxidized to 9c-RAL, which binds to opsins in photoreceptors to regenerate light-sensitive visual pigments.

Figure 4 – Pharmacological strategies to mitigate retinopathies associated with inadequate atRAL clearance.

A. Chromophore replacement therapy using 9cRAL, delivered as a prodrug (9-cis-retinyl acetate). The structure of 9-cis-retinylidene (orange) bound to bovine rod opsin is shown (PDB #2PED). Systemic administration of 9-cis retinoids restores light sensitivity in photoreceptors deprived of visual chromophore due to metabolic blockage in the biosynthesis of 11cRAL. B. Inhibition of retinoid isomerization as a strategy to regulate retinoid flux through the visual cycle. Emixustat represents the evolution of specific and potent RPE65 inhibitors. The crystal structure of bovine RPE65 in complex with emixustat (orange) (PDB #4RYX) with the palmitate moiety colored blue. A schematic representation illustrates RPE65 inhibition in the context of 11-cis retinoid production. C. Inhibition of ocular retinoid uptake by targeting RBP4. The chemical structures of selected RBP4 inhibitors are presented, along with the crystal structure of human RBP4 bound to the competitive inhibitor A1120 (PDB #6QBA). Replacement of atROL with an inhibitor leads to the dissociation of the RBP4/TTR complex, promoting the excretion of monomeric RBP4 by the kidney. This lowers RBP4 concentration in the blood, limiting atROL availability for RPE cells. D. Inhibition of intracellular atROL transport by targeting RBP1. Non-retinoid inhibitors of RBP1 are shown, including the crystal structure of human RBP1 in complex with abn-CBD (PDB #6E6K). The absence of functional RBP1 slows the recycling of retinoids from photobleached visual pigments, reducing the flow of retinoids through the visual cycle. E. Deuterated retinoids at the C20 position as agents to reduce bisretinoid accumulation. The principles of the kinetic isotope effect in the formation of A2E and RALdi are illustrated. Replacing endogenous vitamin A with its deuterated form slows the rate of bisretinoid formation. Created in part with BioRender (https://BioRender.com/jkpaopx).

The efficacy of visual chromophore supplementation has been validated in rodent and canine models of LCA with RPE65 mutations (Gearhart, Gearhart, Thompson, & Petersen-Jones, 2010; T. Maeda, et al., 2013; Van Hooser, et al., 2002). These preclinical successes paved the way for clinical trials involving patients with loss-of-function variants in LRAT and RPE65 (ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT01014052) (Table 2). Clinical results demonstrated that oral 9cRAc treatment was well tolerated, with no serious adverse effects (Koenekoop, et al., 2014). Most patients experienced rapid improvement in visual function, with approximately 50% showing long-term preservation of the visual field and sustained visual acuity (Koenekoop, et al., 2014). A particularly striking outcome was observed in patients with the Asp477/Gly RPE65 substitution, where a single one-week course of 9cRAc provided efficacy lasting up to six months (Kenna, et al., 2020).

Table 2 –

Clinical trials (beyond phase 1) evaluating small molecule-based therapeutic strategies targeting the visual cycle.

| Biological target/mechanism | Compound | Phase | ClinicalTrial.gov ID/sponsor | Purpose | Results (summary) | Publication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visual chromophore replacement | 9-cis-retinyl acetate (QLT1001) | 2a | NCT01999764 QLT, Inc. | To evaluate the effects on adults with impaired dark adaptation. | Completed, no results posted | (Koenekoop, et al., 2014) |

| RPE65 inhibition | Emixustat hydrochloride | 2a | NCT03033108 Kubota Vision, Inc. | To study the pharmacodynamics of emixustat in subjects with macular atrophy secondary to STGD1. | Dose-dependent suppression of rod recovery, confirming emixustat's biological activity in patients with STGD1. | (Kubota, et al., 2022) |

| RPE65 inhibition | Emixustat hydrochloride | 2a | NCT02753400 Kubota Vision, Inc. | To evaluate the effects of emixustat on aqueous humor biomarkers associated with proliferative diabetic retinopathy. | No significant differences in aqueous humor cytokine levels between the emixustat and placebo groups. VEGF levels were slightly reduced in the emixustat but not in the placebo group. | (Kubota, et al., 2021) |

| RPE65 inhibition | Emixustat hydrochloride | 3 | NCT03772665 Kubota Vision, Inc. | To determine if emixustat reduces the rate of progression of macular atrophy compared to placebo in subjects with STGD1. | No significant differences in the rate of change in the area of macular atrophy. | |

| RPE65 inhibition | ACU-4429 (Emixustat hydrochloride) | 2 | NCT001002950 Kubota Vision, Inc. | To evaluate the safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of ACU-4429 in subjects with geographic atrophy.. | Completed, no results posted. | |

| RPE65 inhibition | Emixustat hydrochloride | 2b/3 | NCT01802866 Kubota Vision, Inc. | To determine if emixustat reduces the rate of progression of geographic atrophy compared to placebo in subjects with AMD. | No reduction in the growth rate of geographic atrophy in AMD. | (Rosenfeld, et al., 2018) |

| RBP4 inhibition | Tinlarebant | 1/2 | NCT05266014 RBP4 Pty, Inc. | To evaluate the safety and efficacy of a single daily dose of tinlarebant over a 24-month treatment period. | Completed, no results posted. | |

| RBP4 inhibition | Tinlarebant | 2/3 | NCT06388083 Belite Bio, Inc. | To evaluate the safety, tolerability, and efficacy of daily doses of 5 mg tinlarebant, administered for 24 months, in subjects with STGD1. | Active (recruiting) | |

| RBP4 inhibition | Tinlarebant | 3 | NCT05949593 Belite Bio, Inc. | To evaluate the efficacy and safety of tinlarebant (LBS-008) in subjects diagnosed with GA… | Active (recruiting) | |

| RBP4 inhibition | Tinlarebant | 3 | NCT05244304 Belite Bio, Inc. | To assess the efficacy of tinlarebant in slowing the rate of growth of atrophic lesions in adolescent subjects with STGD1… | Active (not recruiting) | |

| RBP4 inhibition | STG-001 | 2 | NCT04489511 Stargazer Pharmaceuticals, Inc. | To assess the efficacy of pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of STG-001 in Subjects with STGD1.. | Completed, no results posted | |

| Inhibition of bis-retinoids formation by an isotopic effect | C20-d3-retinyl acetate (ALK-001) | 2 | NCT02402660 Alkeus Pharmaceuticals, Inc. | To determine the long-term safety and tolerability of ALK-001 and to explore the effects of ALK-001 on the progression of STGD1. | Active (recruiting) | |

| Inhibition of bis-retinoids formation by an isotopic effect | C20-d3-retinyl acetate (ALK-001) | 2 | NCT04239625 Alkeus Pharmaceuticals, Inc. | To determine the long-term safety and tolerability of ALK-001 and to explore the effects of ALK-001 on the progression of STGD1. | Active (recruiting) Extension of NCT02402660 trial. | |

| Inhibition of bis-retinoids formation by an isotopic effect | C20-d3-retinyl acetate (ALK-001) | 3 | NCT03845582 Alkeus Pharmaceuticals, Inc. | To evaluate the efficacy and safety of ALK-001 in participants with GA secondary to AMD. | Completed, no results posted. | |

| Inhibition of H+/K+ ATPase Removal of lipofuscin from RPE cell deposits | Soraprazan (remofuscin) | 2 | EudraCT Number: 2018-001496-20 Katairo, GmbH | To determine the efficacy and safety of soraprazan in STGD1 vs. placebo. | No significant difference in retinal autofluorescence but less retinal thinning compared to placebo |

Despite the promising results, the systemic effects of cis-retinoid supplementation on retinoid homeostasis remain unclear. A specific concern is the potential for long-term toxicity, especially during pregnancy, due to metabolic conversion of 9cRAc to bioactive corresponding RA isomer (Heyman, et al., 1992). In the absence of LRAT, excess retinol cannot be effectively sequestered in the form of REs, potentially leading to elevated RA levels which represents the main mechanism of retinoid systemic toxicity (Chelstowska, Widjaja-Adhi, Silvaroli, & Golczak, 2017; Isken, et al., 2007; L. Liu, Tang, & Gudas, 2008).

Visual chromophore supplementation represents a promising therapeutic strategy for retinal degenerative diseases caused by LRAT or RPE65 deficiencies. However, further investigation is needed to understand and mitigate systemic side effects, ensuring the safety and efficacy of long-term treatment.

5.1.2. Visual cycle modulators

Prevalent retinal diseases are associated with impaired retinoid homeostasis in the retina, stemming from a decreased rate of atRAL clearance and the consequent formation of aberrant retinal metabolites, collectively referred to as bis-retinoids. A widely accepted strategy to prevent damage to the RPE and retina in diseases associated with the overaccumulation of bis-retinoids is to reduce the steady-state concentration of atRAL. This can be achieved by modulating the flow of retinoids through the visual cycle to slow their turnover. This concept is supported by robust empirical evidence pioneered by Wenzel et al., who first demonstrated that mice expressing the RPE65 Leu450/Met variant are protected against light-induced retinal damage (Wenzel, Reme, Williams, Hafezi, & Grimm, 2001). This protective effect was attributed to the slower regeneration of the visual chromophore. Building on this finding, Sieving et al. showed that pharmacological inhibition of the visual cycle with 13-cis-retinoic acid protected against light-induced retinal damage (Sieving, et al., 2001). Finally, mouse RPE65 Leu450/Met variant prevented the overaccumulation of A2E, a major bis-retinoid condensation product (S. R. Kim, et al., 2004).