Abstract

Introduction

This study investigated quality of life (QoL) and its role in treatment decision making among patients with anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK)+ NSCLC.

Methods

Adult patients with self-reported ALK+ NSCLC residing in the United States from the Lung Cancer Registry from GO2 for Lung Cancer were included. Measures included a core patient survey derived from Quality of Life Questionnaire – Core 30 items (QLQ-C30) and QLQ – lung cancer module 29 items domains and an ALK+ NSCLC module (ALK module). Associations were assessed between key domains and module questions using polyserial or Spearman’s correlations and Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel tests.

Results

Seventy-one patients with ALK+ NSCLC completed the ALK module. Most patients (85%) felt their current therapy helped stop cancer growth, helped them live longer, and was worth taking despite side effects; however, 80% reported some cancer scan-related anxiety and only 32% reported having received “quite a bit” or “very much” mental health support information from their care team. Most patients (75%) reported QoL as a top concern in treatment decisions, regardless of responses to other ALK module questions (all associations p ≥ 0.50). Although most patients (87%) perceived their physicians as interested in their QoL, only 51% reported their physicians discussed QoL as a top concern in treatment decisions. QLQ-C30 composite global health status-QoL score had significant moderate to strong correlations with all other QLQ-C30 and lung cancer module 29 items domains (p ≤ 0.004) and some components of communication with care teams, treatment confidence, and impact on daily life.

Conclusions

QoL is important in treatment decision making for patients with ALK+ NSCLC. These findings highlight areas for improvement in mental health support and patient-provider communication.

Keywords: Anaplastic lymphoma kinase, NSCLC, Patient perspective, Quality of life, Treatment decision making

Introduction

Approximately 3% to 7% of patients with NSCLC have a rearrangement of the anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) gene, an oncogenic driver that is an established therapeutic target.1, 2, 3 Recent advances in treatment, including the development and regulatory approval of highly potent ALK tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), have improved survival and other clinical outcomes among patients with ALK+ NSCLC.1,2,4

There has been an increasing emphasis on the importance of preserving quality of life (QoL) among patients with NSCLC, particularly given the longer survival of patients with improved therapeutic options balanced against the incurable nature of metastatic disease.3, 4, 5, 6, 7 Shared decision-making models in NSCLC recommend a discussion between the clinician and patient about how potential treatments may fit into the patient’s overall lifestyle or affect the quality and duration of life and about potential safety concerns.8, 9, 10

Several validated questionnaires are used to assess QoL in patients with lung cancer.6,11 One of the most common is the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality of Life Questionnaire – lung cancer module 29 items (QLQ-LC29), an updated version of the EORTC QLQ-LC13 (13 questions, the first EORTC module developed for lung cancer),11,12 used in conjunction with the core EORTC QLQ – Core 30 items (QLQ-C30) questionnaire.13, 14, 15 In a review of QoL data from randomized controlled trials of patients with advanced NSCLC without targetable oncogenic drivers, QoL impairments and a lack of improvement with available treatments were consistently identified across multiple instruments.6 In a study of patients with NSCLC who had survived for at least one year after diagnosis, QoL detriments were found on almost all EORTC QLQ-C30 domains, with patients experiencing poorer global QoL, greater functional impairments, and more persistent symptoms than an age- and sex-standardized general population cohort.5

Data on QoL and the role of treatment-related changes in QoL on shared decision making are limited for patients with ALK+ NSCLC. The present study investigated QoL in patients with ALK+ NSCLC. The objectives were (1) to describe patient opinions on treatments, impact of symptoms on daily life, the role of QoL in treatment decisions, and interactions with care teams and (2) to explore the associations of the composite global health status (GHS)/QoL (assessed using the EORTC QLQ-C30) domain with other domains of the EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-LC29 and with questions from a patient-reported ALK + NSCLC module. It was hypothesized that the findings from this study would allow a better understanding of the role QoL plays in treatment decisions and the importance of communication between care teams and patients with ALK+ NSCLC.

Methods

Data Source and Study Population

The data source for this study was the Lung Cancer Registry portal from GO2 for Lung Cancer (www.lungcancerregistry.org), a patient advocacy group that provides resources, support, and programs to patients with lung cancer that advance education, advocacy, and research into lung cancer. As of January 2021, the Lung Cancer Registry contained data from more than 2200 patients, survivors, and caregivers who participated in research surveys.16 A module for patients with self-reported ALK+ NSCLC (ALK module) was available on the portal from January 2022 to September 2022.

Patients aged 18 years or older with self-reported ALK+ NSCLC, residing in the United States, who completed the ALK module were included in this study. Data were derived from the Lung Cancer Registry core patient survey and the ALK module. The core patient survey assesses treatment, symptoms, side effects, QoL by means of the EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-LC29, and other attributes on a quarterly basis. The ALK module included questions on the patient’s confidence in their treatment, the impact of their symptoms and other factors on QoL, and treatment discussions with physicians and care teams adapted from the EORTC QLQ-LC29 validated survey and the Cancer Therapy Satisfaction Questionnaire (Supplementary Table 1).

After the original analyses were completed in March 2023, an additional 12 patients were recruited between September 2023 and December 2023 to complete both a baseline core survey and an ALK module either on the same day or no more than eight days apart. All analyses reported herein were conducted using a combined cohort of patients recruited during both time periods.

Measures

Demographic information was obtained from GO2 baseline surveys completed a mean of 1.1 years (SE 0.2) before the ALK module. QoL was assessed using the EORTC QLQ-C30 and EORTC QLQ-LC29.

The EORTC QLQ-C30 is a 30-item questionnaire that assesses QoL in patients with any cancer type and includes five functional scales (physical, role, cognitive, emotional, and social), three symptom scales (fatigue, pain, and nausea and vomiting), a composite GHS-QoL scale, and several single-item scales assessing additional symptoms (dyspnea, loss of appetite, insomnia, constipation, and diarrhea) and perceived financial impact of the disease.17 All items are completed on a four-item Likert scale (1 = not at all, 2 = a little, 3 = quite a bit, 4 = very much) except for two GHS-QoL items, which are completed on a seven-item Likert scale (1 = very bad to 7 = very good).13,17 For each domain, the average of items is calculated and then standardized by linearly transforming to a scale ranging from 0 to 100.13 On the functional scales, a score of 0 represents the lowest functioning and 100 represents the highest functioning, whereas, on the symptom scales, a score of 0 represents the lowest symptom burden and 100 represents the highest symptom burden.13

The EORTC QLQ-LC29 was updated from EORTC QLQ-LC13, the first EORTC module developed to assess QoL in patients with lung cancer.12, 13, 14, 15,17 The EORTC QLQ-LC29 is used in conjunction with the core EORTC QLQ-C30 questionnaire to assess QoL in patients with lung cancer.15 The EORTC QLQ-LC29 module includes five multi-item scales (coughing, shortness of breath, fear of progression, hair problems, and operation-related symptoms) and 15 single-item scales (e.g., tingling in hands or feet and dizziness).15 The updated module retained 12 of the original 13 items and added new items on relevant and common side effects and a surgical subscale.15

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were reported for demographic characteristics and ALK module questions. Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel tests were used to analyze whether patients’ responses to ALK module questions on their QoL (impact of physical symptoms on daily life, impact of difficulty with concentration on daily life, scan-related anxiety, impact of patient opinion on treatment decisions, and whether the patient is provided information on mental health) differed between patients who reported their physicians did or did not discuss QoL and patients who reported their QoL is or is not important in treatment decisions. Polyserial correlations or Spearman’s correlations were used to assess associations of composite GHS-QoL with other domains of the EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-LC29 and with questions from the ALK module, depending on whether the domain was ordinal or continuous, respectively. Polyserial correlation coefficients were generated for analyses that contained one ordinal domain and one continuous domain, whereas Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients were generated for continuous domains. Although the definitions vary with research areas and specialties, a conventional approach to interpreting Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient and polyserial correlation coefficient includes weak correlation (0.10–0.29), moderate correlation (0.30–0.49), and strong correlation (0.50–1.00).18 Analyses based on the ALK module were only assessed in patients who responded to the ALK module less than or equal to 90 days before or after the QoL data were collected. Multiplicity adjustments were not performed because analyses were considered exploratory.

Results

Patients

This study included 71 adult patients with self-reported diagnosis of ALK+ NSCLC who completed the ALK module. Of these, 63 patients (86.3%) had composite GHS-QoL scores, 39 patients of whom (61.9%) completed the ALK module within 90 days of QoL data collection.

Patient Opinions on Treatments, Impact of Symptoms on Daily Life, the Role of QoL in Treatment Decisions, and Interactions With Care Teams

All patients who completed the ALK module (N = 71) were included in the analysis of patient opinions on treatments, impact of symptoms on daily life, the role of QoL in treatment decisions, and interactions with care teams. These patients had a median age at the time of the survey of 57.0 years (interquartile range [IQR], 48.5–66.0), 70.4% of participants were female, and 90.1% identified as white (Table 1). Most patients had nonsquamous NSCLC (90.1%), 83.1% had stage IIIB-IV disease at baseline, and 69.0% were currently on treatment with an ALK TKI. Data for the line of therapy at baseline were not available for 25.4% of patients, 32.4% were on first-line treatment, 23.9% were on second-line treatment, and 16.9% were on third- or greater-line treatment.

Table 1.

Demographics and Baseline Clinical Characteristics of the Study Population

| Characteristica | All Patients (N = 71) | Composite GHS-QoL Scoresb (n = 63) | Composite GHS-QoL Scores and Complete ALK Module in ≤90 db (n = 39) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at survey | |||

| Patients with data, n | 68 | 63 | 39 |

| Median (IQR), y | 57.0 (48.5–66.0) | 58.0 (50.0–66.0) | 61.0 (50.0–66.0) |

| Age at diagnosis | |||

| Patients with data, n | 67 | 62 | 38 |

| Median (IQR), y | 52.0 (44.0–62.0) | 52.0 (45.0–62.0) | 54.0 (46.0–60.0) |

| Female, n (%) | 50 (70.4) | 47 (74.6) | 25 (64.1) |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| White | 64 (90.1) | 57 (90.5) | 35 (89.7) |

| Asian | 4 (5.6) | 3 (4.8) | 2 (5.1) |

| Unknown/missing | 3 (4.2) | 3 (4.8) | 2 (5.1) |

| Highest level of education achieved, n (%) | |||

| College | 36 (50.7) | 33 (52.4) | 16 (41.0) |

| Master’s/graduate professional training | 19 (26.8) | 17 (27.0) | 12 (30.8) |

| Doctoral | 6 (8.5) | 5 (7.9) | 3 (7.7) |

| Not reported/missing | 10 (14.1) | 8 (12.7) | 8 (20.5) |

| Current treatment with ALK TKI, n (%) | 49 (69.0) | 42 (66.7) | 30 (76.9) |

| Histology, n (%) | |||

| Nonsquamous | 64 (90.1) | 57 (90.5) | 34 (87.2) |

| Squamous | 1 (1.4) | 1 (1.6) | 1 (2.6) |

| Other/not reported | 6 (8.5) | 5 (7.9) | 4 (10.3) |

| Stage at baseline, n (%) | |||

| I to IIIA | 7 (9.9) | 7 (11.1) | 4 (10.3) |

| IIIB to IV | 59 (83.1) | 52 (82.5) | 32 (82.1) |

| Other/not reported | 5 (7.0) | 4 (6.3) | 3 (7.7) |

| Line of therapy, n (%) | |||

| 1 | 23 (32.4) | 19 (30.2) | 9 (23.1) |

| 2 | 17 (23.9) | 16 (25.4) | 8 (20.5) |

| ≥3 | 12 (16.9) | 11 (17.5) | 6 (15.4) |

| Not currently on treatment | 1 (1.4) | 1 (1.6) | 0 |

| Not reported/other/missing | 18 (25.4) | 16 (25.4) | 16 (41.0) |

ALK, anaplastic lymphoma kinase; GHS, global health status; IQR, interquartile range; QoL, quality of life; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

Taken from GO2 baseline surveys, completed on average 1.1 years before the completion of the ALK module.

All data are based on patients who have nonmissing composite GHS-QoL data.

Treatments

Most patients reported they “most of the time” or “always” felt that their current therapy helped stop the cancer from growing (85%), would help them live longer (93%), and was worth taking even if they experienced side effects (95%) (Fig. 1; Supplementary Fig. 1). The responses to these questions were similar among patients who reported current ALK TKI use (n = 28), with 86%, 93%, and 100%, respectively, responding “most of the time” or “always” (data not reported).

Figure 1.

Distribution of response to select ALK module questions in all patients (N = 71)a. aValues presented represent the percentage of responses and may not add up to 100% owing to rounding. ALK, anaplastic lymphoma kinase.

Most patients (80%) reported experiencing scan-related anxiety “1 week prior to a scan” (42%), “1 month prior to a scan” (11%), or “always” (27%). Only 32% of patients reported that they had received “quite a bit” (15%) or “very much” information (17%) on mental health support from their care teams. Being offered information about mental health was not associated with scan-related anxiety (p = 0.548; data not reported).

Impact of Symptoms on Daily Life

Approximately one-quarter of patients reported that physical symptoms affected their life “never” or “rarely” (27%), with most indicating that their life was affected by their physical symptoms at least “sometimes” (73%). Similarly, less than half of patients reported that difficulty concentrating or remembering things affected their daily life “never” or “rarely” (44%), whereas most patients indicated that their life was affected by difficulty concentrating or remembering things at least “sometimes” (56%) (Fig. 1).

Role of QoL in Treatment Decisions

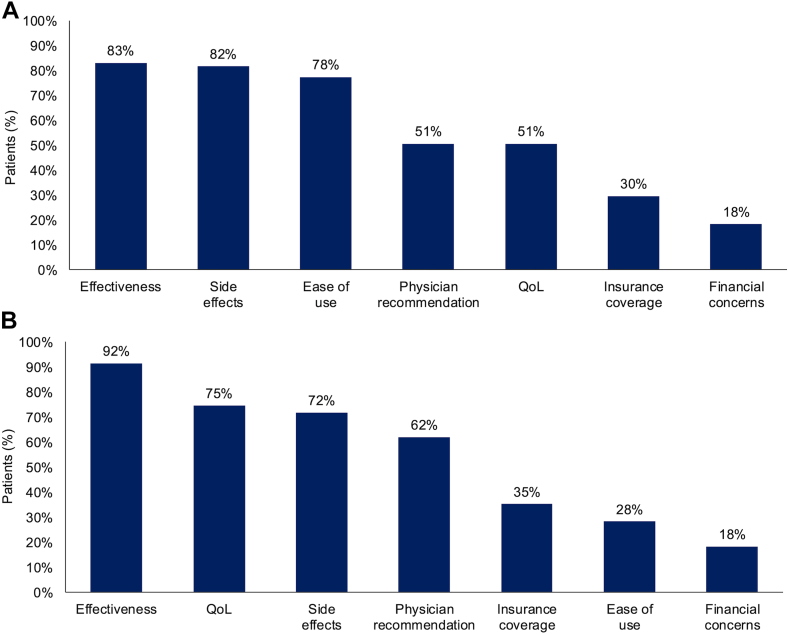

Most patients reported that their physicians discussed effectiveness (83%), side effects (82%), and ease of use (78%) as the top three topics when making treatment decisions, whereas 51% of patients reported that their physicians discussed QoL as a top three topic (Fig. 2A). Based on patient responses, physicians were significantly more likely to focus on QoL as a topic for discussion among patients who were offered or given “quite a bit” or “very much” information on mental health support from their care teams than among patients who were offered or given “not at all” or “a little” information (74% versus 40%; p = 0.007) (Supplementary Fig. 2). Physicians were significantly more likely to focus on QoL as a topic for discussion during treatment decision making among patients who “always” (68%) or “never” (64%) felt scan-related anxiety than among those who reported anxiety in the week or month leading up to a scan (37%; p = 0.044) (Supplementary Fig. 2). The patient-reported likelihood of physicians discussing QoL did not significantly differ by response to any other ALK module questions (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Patient-reported topics for treatment decisions in all patients (N = 71). (A) The most important topics discussed by physicians. (B) The most important topics for patients. QoL, quality of life.

Most patients (75%) reported QoL as one of their top concerns when making treatment decisions (Fig. 2B). This finding was consistent regardless of how patients responded to other ALK module questions regarding their experiences with other aspects of care, such as offers of information on mental health support, their influence on treatment decisions, scan-related anxiety, cognitive difficulties, and physical symptoms (64%–79% across responses; all associations p ≥ 0.50). The other top concerns patients reported when making treatment decisions were effectiveness (92%) and side effects (72%) (Fig. 2B). There was no association between QoL as one of the top three concerns for patients and QoL being one of the top three topics the physician discussed when making treatment decisions (p = 0.945; data not reported), but most patients reported that their physician showed an interest in their QoL (87%) (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Interactions With Care Teams

Most patients (80%) felt their opinion affected their care team’s decision for their current treatment “a little” (15%), “quite a bit” (30%), or “very much” (35%), with 13% of patients reporting that they “do not have any opinion” (Fig. 1). Although most patients (88%) reported feeling they could speak honestly with their cancer care team about their health status “always” (65%) or “most of the time” (23%), 13% reported they felt this way “rarely” or “never” (Supplementary Fig. 1). Similarly, most patients (88%) reported they felt the care team showed interest in how their symptoms affected their day-to-day life “always” (61%) or “most of the time” (27%); however, 12% of patients reported they felt this way “rarely” or “never.”

Associations of Composite GHS-QoL With Daily Functioning and Symptom Severity

Data for patients with composite GHS-QoL scores (n = 63) were included in the analyses investigating the associations of composite GHS-QoL with EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-LC29 domains. Baseline characteristics for this subpopulation closely resembled those of the overall study population (Table 1). The median composite GHS-QoL score was 75.0 (IQR, 58.3–83.3) (Table 2).

Table 2.

EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-LC29 Key Domain Scores

| EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-LC29 item | Composite GHS-QoL Scoresa (n = 63) |

Composite GHS-QoL Scores and Complete ALK Module in ≤90 da (n = 39) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Median (IQR) | n | Median (IQR) | |

| GHS-QoL | 63 | 75.0 (58.3–83.3) | 39 | 75.0 (66.7–83.3) |

| Physical functioning | 59 | 93.3 (80.0–100.0) | 36 | 90.0 (80.0–96.7) |

| Role functioning | 63 | 83.3 (66.7–100.0) | 39 | 83.3 (66.7–100.0) |

| Emotional functioning | 53 | 75.0 (58.3–91.7) | 32 | 83.3 (66.7–95.8) |

| Cognitive functioning | 53 | 83.3 (66.7–83.3) | 32 | 83.3 (66.7–91.7) |

| Social functioning | 53 | 83.3 (66.7–100.0) | 32 | 75.0 (66.7–100.0) |

| Fatigue | 53 | 33.3 (22.2–44.4) | 32 | 33.3 (22.2–33.3) |

| Pain | 57 | 16.7 (0.0–33.3) | 34 | 16.7 (0.0–33.3) |

| Cough | 63 | 33.3 (0.0–33.3) | 39 | 16.7 (0.0–33.3) |

| Shortness of breath | 59 | 22.2 (0.0–33.3) | 37 | 16.7 (0.0–22.2) |

| Experience with adverse events | 54 | 9.7 (5.6–19.4) | 34 | 12.5 (2.8–19.4) |

| Chest pain | 54 | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 34 | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) |

| Weight loss | 54 | 0.0 (0.0–33.3) | 34 | 0.0 (0.0–33.3) |

ALK, anaplastic lymphoma kinase; EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-LC29, European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire – Core 30 items and lung cancer module 29 items; GHS, global health status; IQR, interquartile range; QoL, quality of life.

All data are based on patients who have nonmissing composite GHS-QoL data.

Composite GHS-QoL score revealed strong positive correlations with the physical functioning (Spearman, 0.730; p < 0.0001), role functioning (polyserial, 0.641; p < 0.0001), and social functioning scales (polyserial, 0.536; p < 0.0001) and moderate positive correlations with the emotional functioning (Spearman, 0.384; p = 0.004) and cognitive functioning scales (polyserial, 0.409; p < 0.001) (Table 3). In terms of associations with symptoms, composite GHS-QoL score had strong negative correlations with fatigue (Spearman, –0.560; p < 0.0001), shortness of breath (Spearman, –0.651; p < 0.0001), experience with adverse events (polyserial, –0.591; p < 0.0001), chest pain (polyserial, –0.625; p < 0.0001), and weight loss (polyserial, –0.517; p < 0.0001) and moderate negative correlations with pain (polyserial, –0.453; p < 0.001) and cough (polyserial, –0.383; p = 0.004) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Association of Composite GHS-QoL With EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-LC29 Function and Symptom Domains and ALK Module Questions

| EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-LC29 Itema | n | Polyserial or Spearman’s Correlationb | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical functioningc | 59 | 0.730 | < 0.0001 |

| Role functioningd | 63 | 0.641 | < 0.0001 |

| Emotional functioningc | 53 | 0.384 | 0.004 |

| Cognitive functioningd | 53 | 0.409 | < 0.001 |

| Social functioningd | 53 | 0.536 | < 0.0001 |

| Fatiguec | 53 | -0.560 | < 0.0001 |

| Paind | 57 | -0.453 | < 0.001 |

| Coughd | 63 | -0.383 | 0.004 |

| Shortness of breathc | 59 | -0.651 | < 0.0001 |

| Experience with adverse eventsd | 54 | -0.591 | < 0.0001 |

| Chest paind | 54 | -0.625 | < 0.0001 |

| Weight lossd | 54 | -0.517 | < 0.0001 |

| ALK module question | n | Polyserial or Spearman’s correlationb | p value |

| Treatment confidence | |||

| Feeling the treatment will stop the cancer from growingd | 39 | 0.217 | 0.227 |

| Feeling the treatment will help you live longerd | 39 | 0.438 | 0.006 |

| Feeling the treatment is worth takingd | 39 | 0.636 | < 0.0001 |

| Feeling the good things outweigh the bad things in taking treatmentd | 39 | 0.399 | 0.016 |

| Communication with care team | |||

| Comfort level speaking honestly with care teamd | 39 | 0.539 | < 0.001 |

| Feeling that care team shows interest in QoLd | 39 | 0.490 | 0.002 |

| Feeling your opinion impacts treatment decisionsd | 33 | 0.278 | 0.112 |

| Feel comfortable asking care team for a second opiniond | 33 | -0.289 | 0.318 |

| Given information on mental health supportd | 39 | 0.079 | 0.641 |

| Impact on daily life | |||

| Impact of physical symptoms on daily lifed | 39 | –0.604 | < 0.0001 |

| Impact of difficulty with concentration on daily lifed | 39 | –0.361 | 0.017 |

| Scan-related anxiety (how often)d | 39 | –0.051 | 0.767 |

Note: All data are based on patients who have nonmissing composite GHS-QoL data. Bolded p-values represent p ≤ 0.05.

ALK, anaplastic lymphoma kinase; EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-LC29, European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire – Core 30 items and lung cancer module 29 items; GHS, global health status; QoL, quality of life.

Other symptoms evaluated included nausea-vomiting, insomnia, appetite, constipation, diarrhea, financial, fear of progression, operation problems, coughing blood, pain in chest, pain in arm, and pain in other parts.

Polyserial correlation coefficients were generated on ordinal domains; otherwise, Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients were generated.

Analyzed using Spearman’s correlation, interpreted as follows: weak correlation (0.10–0.29), moderate correlation (0.30–0.49), and strong correlation (0.50–1.00).

Analyzed using polyserial correlation, interpreted as follows: weak correlation (0.10–0.29), moderate correlation (0.30–0.49), and strong correlation (0.50–1.00).

Associations of Composite GHS-QoL With Treatment Confidence, Communication With Care Teams, and Impact on Daily Life

Data for patients with composite GHS-QoL scores who completed the ALK module within 90 days (n = 39) were included in the analyses investigating the associations of composite GHS-QoL score with communication with care teams. Baseline characteristics for this subpopulation closely resembled those of the overall study population (Table 1). The median composite GHS-QoL score was 75.0 (IQR, 66.7–83.3) (Table 2).

The composite GHS-QoL score revealed significant associations with most of the ALK module questions related to the patients’ confidence in their treatment, including a strong positive correlation with feeling the treatment is worth taking (polyserial, 0.636; p < 0.0001) and moderate positive correlations with feeling the treatment will help them live longer (polyserial, 0.438; p = 0.006) and feeling the good things outweigh the bad things in taking their treatment (polyserial, 0.399; p = 0.016) (Table 3). There was no significant correlation between composite GHS-QoL score and feeling the treatment will stop the cancer from growing (polyserial, 0.217; p = 0.227).

In terms of ALK module questions regarding communication with care teams, a significant, strong positive correlation was detected between composite GHS-QoL score and comfort level speaking honestly with their care team (polyserial, 0.539; p < 0.001) (Table 3). GHS-QoL had a significant moderate correlation with feeling that the care team shows interest in QoL (polyserial, 0.490; p = 0.002). There were no significant correlations between composite GHS-QoL score and the patient feeling their opinion affects treatment decisions (polyserial, 0.278; p = 0.112), feeling comfortable asking the care team for a second opinion (polyserial, –0.289; p = 0.318), and being given information on mental health support (polyserial, –0.079; p = 0.641).

Composite GHS-QoL score had a strong negative correlation with impact of physical symptoms on daily life (polyserial, –0.604; p < 0.0001), a moderate negative correlation with impact of difficulty with concentration on daily life (polyserial, –0.361; p = 0.017), and no significant correlation with how often the patient experiences scan-related anxiety (polyserial, 10.051; p = 0.767) (Table 3).

Discussion

This study highlights the importance of QoL in treatment decision making and communication with care teams among patients with ALK+ NSCLC and provides valuable context regarding priorities and perceptions of treatment in this patient population. Findings revealed that most patients reported that their physical and cognitive symptoms affected their daily life to some extent, and the composite GHS-QoL score was positively correlated with all functioning domains and negatively correlated with all symptom scales of the QLQ-C30 or QLQ-LC29 reported herein. Notably, QoL was one of the top three concerns for patients when making treatment decisions with their care teams, regardless of the associations between QoL and the impact of their condition on their daily life, scan-related anxiety, their own involvement in treatment decisions, or being given/offered information on mental health support. Despite most patients feeling their care team showed interest in their QoL, approximately half indicated that QoL was one of the top three topics discussed by their physicians during treatment decision making. Based on patient reports, physicians were more likely to discuss QoL with patients who received at least some information on mental health support than with patients who received little or none, although the findings do not allow for elucidation of cause and effect for associations. Collectively, these results suggest a discrepancy between patient and physician prioritization of QoL and highlight an area for improvement in the care of patients with ALK+ NSCLC. This gap could potentially be addressed by increasing physician education on the importance of QoL in treatment considerations and improving dialogue between patient advocates and care teams.

Findings from the present study are consistent with previous reports, which revealed that patients with lung cancer, including those with ALK+ NSCLC, find symptomology, treatment effectiveness, and QoL top concerns when making treatment decisions.3,19,20 Semistructured qualitative interviews found that 87.5% of patients with ALK+ NSCLC experienced negative impacts of lung cancer symptoms on daily activities and 50% or more reported impaired social, emotional, and physical functioning.20 In a real-world study that used data from the ALKConnect Patient Insight Network, a patient-focused registry of individuals with ALK+ NSCLC in the United States, patients reported that symptoms interfered with several daily living activities, and most patients reported that symptom relief and manageable side effects were “very important” treatment attributes.3 Notably, 92% of patients reported that preventing disease progression and treatment response were among their top three “very important” treatment preferences, along with health-related QoL (88%).3 Importantly, both lung cancer and its therapy influence patient QoL; therefore, clinical decision making should be multidimensional, considering benefits such as increased survival and risks of reduced QoL.21,22

Thorough and open communication between patients and their care team is essential to support QoL throughout the different stages of NSCLC. In the present study, most patients felt confident in their current treatment, felt they were involved in treatment decision making, and were comfortable speaking honestly with their care teams; however, at a more granular level, only approximately two-thirds of patients “always” felt they could speak honestly with their care team about their health status or felt the care team showed interest in how their symptoms affected their day-to-day life. These findings highlight an important gap to address, given that care teams should strive to make sure all patients feel comfortable with such facets of the care experience at all times. In other studies, high-quality patient-clinician communication supported better QoL in patients with lung cancer.23,24 In a study of patients with early-stage NSCLC in the United States, patients’ trust in their physician was associated with better communication and the opportunity to openly express their concerns.23 In a French Delphi consensus study, a panel of 60 physicians involved in the management of patients with lung cancer agreed that QoL discussions are important for treatment decisions at all time points along the course of the disease and are key to successful patient-physician interactions.24

An improved understanding of the importance of QoL may be particularly relevant for patients with ALK+ NSCLC. In many patients with NSCLC, smoking-related comorbidities may contribute to reduced physical QoL,7 and increased age has been associated with higher baseline comorbidity status.25 However, on average, patients with ALK+ NSCLC are less likely to have a smoking history and are younger than patients with non-ALK+ NSCLC overall.26 Importantly, the increasing availability of effective and well-tolerated targeted treatments1 may allow for extended periods of good physical function and enhanced QoL for patients after diagnosis with ALK+ NSCLC. Given that patients with ALK+ NSCLC live longer with these effective treatment options, continued studies to help enhance their QoL and comfort are pivotal.

Limitations

There are several limitations in the current study. The surveys performed were based on relatively small and self-selected samples, and participation in the Lung Cancer Registry was voluntary; therefore, the results may be susceptible to selection bias and the group of patients included may not be representative of the general U.S. population. For example, all patients with data available for level of education reported a college education or higher, suggesting that individuals with a higher level of education may have been more likely to participate than those with a lower level of education. The self-reporting nature of the survey may have increased susceptibility to recall bias. Although the ALK module questions were adapted from existing scales, they were not themselves validated in their current form. In addition, the ALK module and core survey for EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-LC29 questions were completed at different times for some patients. Although ALK modules were completed within 90 days of QoL data collection, the results may have been affected by the comparison of time-sensitive questions between the two surveys. As with any survey, some questions may have been interpreted differently among participants, which could have increased variability in the results. Multiple statistical tests were performed in the present study, and multiplicity adjustments were not used; therefore, there is a risk of type I errors in the findings. The results should be considered exploratory and interpreted cautiously.

Conclusion

The findings from this study reveal that treatment effectiveness, impact of symptoms on daily life, and QoL are top priorities for patients with ALK+ NSCLC in treatment decision making. They also emphasize the importance of communication between patients and their care teams to ensure that these patients’ needs are recognized and incorporated into management planning. Although the results reveal that most patients with ALK+ NSCLC are satisfied with their care and feel involved in treatment decision making, they do highlight room for improvement in the consistent consideration of mental health and QoL by care teams during treatment discussions. Initiatives aimed at improving patient-physician communication, such as educational programs involving advocacy groups and other stakeholders to capture the patient voice, may help reduce gaps in treatment decision-making priorities between patients with ALK+ NSCLC and their care teams.

CRediT Authorship Contribution Statement

Heather Law: Conceptualization, Investigation, Project administration, Supervision, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing.

Huamao M. Lin: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources [Software], Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing.

Eileen Curran: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources [Software], Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing.

Annette Szumski: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology [Software], Visualization, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing.

Jacinta Wiens: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources [Software], Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing.

Jennifer Blender: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing.

Emily S. Venanzi: Investigation, Methodology, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing.

Erin L. Schenk: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing.

Jessica J. Lin: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing.

Jennifer C. King: Conceptualization, Investigation, Supervision, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing.

Disclosure

A. Law reports receipt of institutional funding from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb, Genentech (a member of the Roche Group), Mirati Therapeutics, Novartis, Pfizer, Thermo Fisher Scientific, and Takeda. Dr. H. Lin reports employment and stock ownership with Takeda. Dr. Curran reports employment and stock ownership with Takeda at the time of the study. A. Szumski reports provision of statistical services to Takeda as a contractor and employment with Cytel. Dr. Schenk has performed advisory board and consulting work for Takeda, Boehringer Ingelheim, Jansen, Guidepoint Global, Regeneron, Bionest Partners, Actinium Pharmaceuticals, Prescient Healthcare Group, G1Therapeutics, ClearView Healthcare Partners, BioAtla, The Scienomics Group, AstraZeneca, Thirdbridge, Harpoon Therapeutics, CDR-Life, and Expert Connect; performed scientific advisory role work for Thetis Pharmaceuticals; and has received honoraria from Takeda, Ideology Health, Horizon CME, OncLive, Regeneron, MH Life Sciences, MECC Global Meetings, Jansen, BeiGeneius, Harpoon Therapeutics, and Medscape. Dr. J. Lin reports personal fees from C4 Therapeutics, Blueprint Medicines, Mirati Therapeutics, AnHeart Therapeutics, CLaiM Therapeutics, Yuhan, Ellipses Pharma, Daiichi Sankyo, Eli Lilly, AstraZeneca, Regeneron, Janssen, Nuvation Bio, Roche, and Hyku Biosciences; grants and personal fees from Genentech, Nuvalent, Bayer, Elevation Oncology, Novartis, Turning Point Therapeutics, and Bristol Myers Squibb; grants, personal fees, and other support from Pfizer; grants from Relay Therapeutics, Roche, and Linnaeus Therapeutics; and personal fees and other support from Merus and Takeda outside the submitted work. Dr. King reports consultant or advisor role work for Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, and Foundation Medicine, with all funds paid to GO2 for Lung Cancer. The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Medical writing support provided bySNELL Medical Communication Inc. This study and medical writing support were sponsored by Takeda Development Center Americas, Inc.

Footnotes

All Registry research surveys are IRB approved and all consent required are collected within the registry.

Cite this article as: Law H, Lin HM, Curran E, et al. Role of quality of life in daily functioning, communication with care teams, and treatment decisions in patients with ALK+ NSCLC. JTO Clin Res Rep 2025;6:100863

Note: To access the supplementary material accompanying this article, visit the online version of the JTO Clinical and Research Reports at www.jtocrr.org and at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtocrr.2025.100863.

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Cooper A.J., Sequist L.V., Lin J.J. Third-generation EGFR and ALK inhibitors: mechanisms of resistance and management. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2022;19:499–514. doi: 10.1038/s41571-022-00639-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duma N., Santana-Davila R., Molina J.R. Non-small cell lung cancer: epidemiology, screening, diagnosis, and treatment. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;94:1623–1640. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2019.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lin H.M., Pan X., Biller A., et al. Humanistic burden of living with anaplastic lymphoma kinase-positive non-small-cell lung cancer: findings from the ALKConnect patient insight network and research platform. Lung Cancer Manag. 2020;10 doi: 10.2217/lmt-2020-0018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ramirez R.A., Lu J., Thomas K.E.H. Quality of life for non-small cell lung cancer patients in the age of immunotherapy. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2018;7:S149–S152. doi: 10.21037/tlcr.2018.03.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hechtner M., Eichler M., Wehler B., et al. Quality of life in NSCLC survivors - a multicenter cross-sectional study. J Thorac Oncol. 2019;14:420–435. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2018.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heigener D., Küchler T. Measurement of quality of life in second-line patients with advanced NSCLC without targetable mutations: a review. Lung Cancer Manag. 2016;5:105–116. doi: 10.2217/lmt-2016-0010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jovanoski N., Bowes K., Brown A., et al. Survival and quality-of-life outcomes in early-stage NSCLC patients: a literature review of real-world evidence. Lung Cancer Manag. 2023;12 doi: 10.2217/lmt-2023-0003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dalmia S., Boele F., Absolom K., et al. Shared decision making in early-stage non-small cell lung cancer: a systematic review. Ann Thorac Surg. 2022;114:581–590. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2021.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garcia Campelo M.R., Lin H.M., Zhu Y., et al. Health-related quality of life in the randomized phase III trial of brigatinib vs crizotinib in advanced ALK inhibitor-naive ALK + non-small cell lung cancer (ALTA-1L) Lung Cancer. 2021;155:68–77. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2021.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Samson P., Waters E.A., Meyers B., Politi M.C. Shared decision making and effective risk communication in the high-risk patient with operable stage I non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2016;101:2049–2052. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2016.02.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hircock C., Wang A.J., Goonaratne E., et al. Comparing the EORTC QLQ-LC13, EORTC QLQ-LC29, and the FACT-L for assessment of quality of life in patients with lung cancer - an updated systematic review. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2024;18:260–268. doi: 10.1097/SPC.0000000000000725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bergman B., Aaronson N.K., Ahmedzai S., Kaasa S., Sullivan M. The EORTC QLQ-LC13: a modular supplement to the EORTC Core Quality of Life Questionnaire (QLQ-C30) for use in lung cancer clinical trials. EORTC Study Group on Quality of Life. Eur J Cancer. 1994;30A:635–642. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(94)90535-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koch M., Gräfenstein L., Karnosky J., Schulz C., Koller M. Psychosocial burden and quality of life of lung cancer patients: results of the EORTC QLQ-C30/QLQ-LC29 questionnaire and Hornheide Screening Instrument. Cancer Manag Res. 2021;13:6191–6197. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S314310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koller M., Hjermstad M.J., Tomaszewski K.A., et al. An international study to revise the EORTC questionnaire for assessing quality of life in lung cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:2874–2881. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koller M., Shamieh O., Hjermstad M.J., et al. Psychometric properties of the updated EORTC module for assessing quality of life in patients with lung cancer (QLQ-LC29): an international, observational field study. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:723–732. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30093-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lung Cancer Registry About the lung cancer registry. https://lungcancerregistry.org/about/

- 17.Aaronson N.K., Ahmedzai S., Bergman B., et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:365–376. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.5.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cohen J. 2nd ed. Routledge; Abingdon, UK: 1988. (Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Science). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wheatley-Price P., Ferris A.S., Barros L.H.D.C., et al. Insights into the advanced non-small cell lung cancer patient journey: treatment decision-making, preferences, and quality of life considerations. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhu Y., Lenderking W., Jean-Baptiste M., et al. Importance of capturing the patient experience of overall symptoms and HRQoL impact in patients with ALK+ NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol. 2021;16:S323–S324. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Polanski J., Jankowska-Polanska B., Rosinczuk J., Chabowski M., Szymanska-Chabowska A. Quality of life of patients with lung cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 2016;9:1023–1028. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S100685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shrestha A., Martin C., Burton M., Walters S., Collins K., Wyld L. Quality of life versus length of life considerations in cancer patients: a systematic literature review. Psychooncology. 2019;28:1367–1380. doi: 10.1002/pon.5054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dalton A.F., Bunton A.J., Cykert S., et al. Patient characteristics associated with favorable perceptions of patient–provider communication in early-stage lung cancer treatment. J Health Commun. 2014;19:532–544. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2013.821550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Westeel V., Bourdon M., Cortot A.B., et al. Management of lung cancer patients’ quality of life in clinical practice: a Delphi study. ESMO Open. 2021;6 doi: 10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Asmis T.R., Ding K., Seymour L., et al. Age and comorbidity as independent prognostic factors in the treatment of non small-cell lung cancer: a review of National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group trials. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:54–59. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.8322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shaw A.T., Yeap B.Y., Mino-Kenudson M., et al. Clinical features and outcome of patients with non-small-cell lung cancer who harbor EML4-ALK. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4247–4253. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.6993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.