Abstract

Objectives

Cancer mortality, particularly for gender-specific cancers, has increased in Iran and other developing countries, highlighting notable disparities in regional trends and patterns. This study examines geographical and temporal trends in cancer mortality from 2017 to 2019.

Methods

We analyzed data from Iran's Ministry of Health's death registration system, focusing on populations of 11,807 females and 14,450 males in 2017; 3133 females and 4439 males in 2018; and 4799 females and 6624 males in 2019. We employed spatial statistical methods, including Anselin Local Moran's I and Hot Spot Analysis (Getis-Ord Gi*), alongside techniques such as Mean Center, Standard Distance, and Geographic Information Systems to evaluate cancer mortality at the township level.

Results

Between 2017 and 2019, cancer mortality rates among women declined from 44.9 % to 42.0 %, while rates among men increased from 55.0 % to 57.9 %. The epicenter of mortality shifted from central regions in 2017 to western regions in 2018, then to eastern regions in 2019. The standard deviation ellipse indicated a transition in cancer mortality distribution from a northwest-southeast alignment in 2017 to predominantly western and eastern orientations in subsequent years, with varied hotspot patterns across Iran.

Conclusions

The study highlights rising cancer mortality rates, particularly among men and premenopausal women, underscoring the need for targeted public health interventions and improved medical infrastructure to enhance prevention and treatment efforts.

Keywords: Cancer mortality, Epidemiology, Gender disparities, Health policy, GIS

Highlights

-

•

Geospatial analysis reveals patterns in cancer mortality distribution and trends.

-

•

Detailed data aids policymakers in crafting evidence-based cancer strategies.

-

•

Targeted interventions can be designed for identified high-risk areas.

-

•

Findings lay groundwork for future research on risk factors in high-risk regions.

-

•

Early diagnosis and control can be improved through focused screening programs.

1. Introduction

Cancer caused nearly 10 million deaths in 2020, making up about one in six deaths worldwide. Men are most affected by lung, prostate, and colorectal cancers, while women mainly face breast and cervical cancers (Sato et al., 2021). The rising cancer burden strains individuals and healthcare systems, especially in low- and middle-income countries with limited access to diagnosis and treatment. Conversely, countries with strong healthcare systems achieve better survival rates through early detection and effective therapies. Closing these disparities is essential for equitable cancer care (Prager et al., 2018).

One-third of cancer-related deaths are linked to lifestyle factors, such as tobacco use, high body mass index, excessive alcohol consumption, low fruit and vegetable intake, and insufficient physical activity (Hu et al., 2024). In low-income countries, infections like HPV and hepatitis contribute to about 30 % of cancer cases, emphasizing the need for targeted public health interventions and vaccinations (Canfell et al., 2020). In Iran, cancer is the second leading cause of death and the top cause of mortality for those under 85, underscoring the urgent need for effective prevention, early detection, and treatment (Amini et al., 2022).

Mortality rates are key indicators of a country's development and public health, shaped by social, economic, political, and environmental factors. In developing countries, structural inequalities cause notable spatial disparities in these rates (Murchie et al., 2021). Geographic Information Systems (GIS) technology effectively maps the clustering of mortality-related causes, enabling detailed analysis of disease distribution and mortality trends. GIS highlights the spatial and ecological aspects of diseases, aiding epidemiological studies to identify high-risk areas for targeted interventions. This integration improves understanding of mortality causes and supports strategies to reduce rates across populations (Zanganeh et al., 2023).

Identifying spatial patterns of mortality causes and addressing their contributing factors is essential for policymakers and health planners (Murchie et al., 2021). Analyzing mortality trends and causes of death helps inform strategies to reduce premature deaths. Geographic distribution of mortality data improves public health planning, prioritization, and response (Wang, 2020).

Using maps to display cancer rates can effectively illustrate geographic variations. However, incorporating cluster analysis through modern disease surveillance algorithms adds significant value. These algorithms identify groups of adjacent counties with elevated cancer rates, revealing spatial patterns and highlighting areas where interventions and resources are needed most. Cluster analysis not only identifies high cancer rate clusters but also assesses their statistical significance, filtering out random groupings and emphasizing meaningful patterns. This allows researchers to prioritize geographic areas for further investigation into the causes of unusually high cancer incidence or mortality rates, facilitating targeted intervention strategies. Not all counties in high-rate clusters have elevated cancer rates. GIS software helps identify outbreaks and alerts health departments. Follow-up analyses of larger clusters can uncover smaller hotspots, improving detection and response (Amini et al., 2022).

Cancer is a leading cause of death globally and significantly impacts mortality rates in Iran. Research on cancer can enhance the effectiveness of public health initiatives and inform policymakers. Utilizing GIS for spatial analysis provides valuable insights into the epidemiology of cancer. This study examines the spatial and epidemiological patterns of cancer-related mortality in Iran from 2017 to 2019, identifying geographical variations in mortality rates and associated risk factors. The findings aim to guide targeted interventions and policy strategies to mitigate cancer's impact in Iran.

2. Methods

2.1. Study population

Iran is a country located in West Asia. With a population exceeding 92 million residents, it ranks as the 17th most populous country in the world. Covering an expansive area of approximately 1,648,195 km2 (636,372 mile2). The country is subdivided into 31 provinces and 483 counties.

This study analyzed verified cancer mortality data from Iran's Ministry of Health (2017–2019), covering 11,807 females and 14,450 males in 2017; 3133 females and 4439 males in 2018; and 4799 females and 6624 males in 2019.

2.1.1. Data limitations

Analyses were constrained by county-level mortality records and the lack of annual census updates (2017–2019 data were used). Risk factor assessment was limited due to unavailable data on air pollution, behavioral factors (e.g., tobacco), and socio-economic variables.

While this study utilizes 2017–2019 data, these represent Iran's most recent complete national cancer mortality registry prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, which significantly disrupted healthcare systems and mortality reporting. This pre-pandemic baseline is particularly valuable because:

-

1)

Cancer mortality patterns evolve slowly due to latency periods of environmental/behavioral risk factors and gradual implementation of screening/treatment programs.

-

2)

The 3-year average provides robust smoothing of annual fluctuations.

-

3)

These data establish critical spatial patterns for comparison with future pandemic-era studies.

2.2. Measures

The Ministry of Health in Iran maintains a comprehensive database that includes disease incidence, mortality, health service use, and demographic data. For cancer, it records diagnoses, staging, treatment, and outcomes from hospitals, labs, and death records. The system uses the International Classification of Diseases coding to standardize cancer classification by site, histology, and stage, ensuring consistent data reporting and comparison nationally and internationally (Hong and Zeng, 2023; Barke et al., 2022).

Examining all cancer types together provides valuable public health insights by assessing overall disease burden, identifying spatial patterns, monitoring trends and policy impact, and enhancing data analysis (Barke et al., 2022).

2.3. Data management

2.3.1. GIS mapping and spatial analysis

We integrated county-level outcome and covariate data with Iranian county boundary shapefiles in a GIS, creating thematic maps of key indicators. We also geocoded cancer mortality data at the address level and mapped the points.

Ministry Database & Geocoding Details:

2.3.2. Patient addresses

Residential addresses at time of death are recorded to support geographic analysis and public health interventions.

2.3.3. Validation

Addresses are verified through cross-referencing with official registries to ensure accuracy.

2.3.4. Geocoding challenges

Incomplete or inconsistent formatting may occur, but <4 % of records lack address data, minimizing impact on spatial analysis reliability.

Using Arc/Catalog, we managed data by creating shapefiles, adjusting coordinates, and establishing topological relationships. We utilized Arc/Catalog for a range of data management tasks. First, we created shapefiles to establish new spatial datasets. Next, we imported data to develop additional shapefiles, ensuring accurate integration of various data sources. Finally, we projected the data to align it with the appropriate coordinate systems, enhancing spatial analysis and interoperability.

2.4. Analysis

Through GIS-based analysis, we transformed, classified, and integrated the resulting informational layers to identify significant spatial-temporal patterns in cancer mortality across demographic groups and geographic regions.

2.4.1. Mean center

Mean center calculates the average x- and y-coordinates of features, useful for tracking changes in spatial distributions like cancer mortality. It is calculated using the formula (Unwin, 1996; Chung et al., 2004):

| (1) |

Cancer mortality coordinates were represented by xi and yi, where i is the total mortality count.

2.4.2. Standard distance

Standard distance Standard distance measures the compactness of cancer mortality distribution by providing a single value that indicates how spread out the mortality rates are around the mean. It is calculated using the formula (Unwin, 1996; Chung et al., 2004):

| (2) |

where xi, yi and zi are the coordinates for cancer mortality i, represents the mean center for the mortalities, and n is equal to the total number of mortalities.

2.4.3. Hot spot analysis (Getis-Ord Gi*)

The Getis-Ord Gi* detects significant hot/cold spots in weighted features:

| (3) |

where xj is the attribute value for cancer mortality j, wi,j is the spatial weight (A mathematical representation of how geographic features (e.g., counties, hospitals) influence each other based on proximity or adjacency.) between mortality i and j, n is equal to the total number of mortalities (Unwin, 1996; Chung et al., 2004; Reshadat et al., 2018).

2.4.4. Anselin Local Moran's I

Local Moran's I identifies clusters (positive I) and outliers (negative I), with p < 0.05 indicating significance. Features are classified as high or low clusters, or outliers differing from surrounding values. Without False Discovery Rate (FDR) (a statistical method to control the proportion of false positives among all significant results.) correction, p-values under 0.05 are significant. FDR adjustment refines this threshold to better control false discoveries and improve confidence in results. (Unwin, 1996; Chung et al., 2004). The Local Moran's I statistic formula is:

| (4) |

where xi is an attribute for cancer mortality (the number of deaths due to cancer within a specific population over a set period) i, is the mean of the corresponding attribute, wi,j is the spatial weight between mortality i and j, and:

| (5) |

n is the total number of mortalities.

The ZIi-score for the statistics is computed as:

| (6) |

where:

| (7) |

| (8) |

All GIS mapping and spatial analyses were performed using ArcGIS 10.8.2 (ESRI, Redlands, CA), following the framework of Spatial and Spatio-Temporal Analysis of Cancer Mortality in Iran.

2.4.5. Ethical considerations

This study was approved by Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences (IR.KUMS.REC.138.520) and followed the Declaration of Helsinki.

3. Results

Cancer mortality rates in Iran from 2017 to 2019 showed higher rates in men than women. In 2017, women's mortality was 44.9 %, while men's was 55.0 %. The trend continued with women at 41.3 % and men at 58.6 % in 2018, and 42.0 % in women and 57.9 % in men in 2019. Mortality was highest among those aged 65 and older, with notable increases observed in women of reproductive age and men of working age. These patterns are depicted in Fig. 1, indicating a concerning rise in mortality within these groups.

Fig. 1.

Trends in cancer mortalities in Iran during 2017–2019.

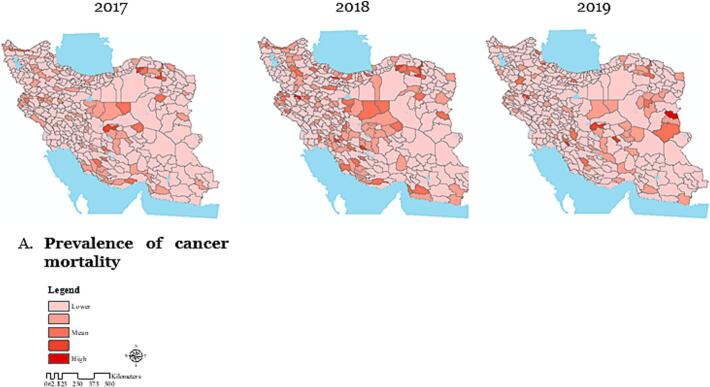

The analysis of cancer-related mortality rates per 100,000 populations at the county level in Iran from 2017 to 2019 revealed distinct trends in mortality patterns across different counties (Fig. 2-A).

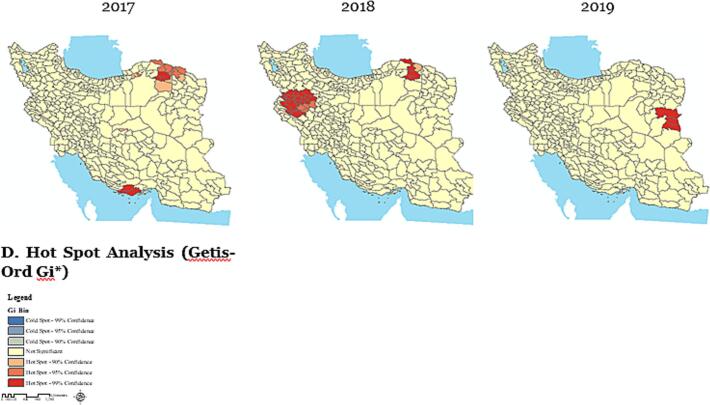

Fig. 2.

Spatial pattern analysis of cancer-related mortality per 100,000 population using Geographic Information Systems at the county level in Iran during the years 2017–2019.

The Maps were created by ArcGIS (version 10.8.1). (A) Dark areas represent a higher prevalence of cancer mortality, while light areas indicate a lower prevalence; (B) In 2017, the highest cancer mortality was in central Iran. By 2018, it shifted westward, and in 2019, moved eastward, showing a changing pattern over time; (C) Maps showing local autocorrelation analysis of mortality use different colors to represent various clustering patterns. Light grey areas indicate regions where these patterns are not statistically significant; (D) The analysis identifies cancer death clusters, hotspots, and shifting spatial patterns across Iran over time.

In 2017, cancer deaths were concentrated in central Iran, shifting westward in 2018 and eastward in 2019, with over 70 % of deaths in these regions (Fig. 2-B). Standard distance metrics showed the spread of mortality from central Iran to the east and northeast, with the radius increasing over time. The standard deviation ellipse, which was oriented northwest-southeast in 2017, shifted toward the west and east in 2018 and 2019, and its size grew, indicating expanded and changing spatial distribution (Fig. 2-B).

Fig. 2-C shows high-value clusters with high mortality, low-value clusters with low mortality, and high outliers amid low values/ low outliers amid high values clusters indicating regions where high or low mortality areas are surrounded by contrasting values.

Fig. 2-D shows Getis-Ord Gi* clusters of cancer deaths per 100,000 from 2017 to 2019, revealing hotspots and changing spatial patterns of mortality across Iran during this period.

4. Discussion

This study analyzes the spatial and temporal clusters of cancer mortality in Iran, revealing geographic patterns and trends. Using advanced statistics, it identifies key clusters to inform public health strategies aimed at reducing cancer deaths.

Our findings reveal a concerning increase in cancer-related mortality rates in Iran. In stark contrast, a study conducted by Cronin et al., 2022 in the United States demonstrates a significant decline in overall cancer mortality rates. This divergence underscores the critical importance of utilizing current, population-based data to inform prevention strategies, enhance early detection, and improve treatment efforts. Such proactive measures have proven effective in alleviating the cancer burden in the United States, suggesting that similar approaches may be necessary to address the rising cancer mortality rates in other regions, including Iran (Cronin et al., 2022).

These trends indicate significant shifts in cancer risk factors, increased screening, improved diagnostics, and better treatments. Early-stage detection can effectively prevent or treat many cancers. Therefore, current data on cancer incidence and mortality are essential for developing strategies to reduce the cancer burden in the U.S. and monitor progress toward health goals (Henley et al., 2020). To reduce cancer mortality in Iran, it's recommended to implement similar programs focusing on prevention, early detection, and effective treatment, leveraging successful strategies from other regions to enhance health outcomes.

Our study finds higher cancer mortality in men than women, contrasting Cronin et al. (2018), who reported declines for both genders. This highlights the need for further research into factors affecting these trends (Cronin et al., 2018). A key factor in the 50-year decline in cancer mortality is reduced smoking among women, driven by policies like higher taxes and bans (Jemal et al., 2008). Advances in early detection and treatment, especially targeted therapies, have also reduced mortality rates for breast, prostate, and colorectal cancers (Health, U.D.o. and H. Services, 2014). Ongoing declines in breast, prostate, and colorectal cancer mortality are mainly due to early detection and improved treatments, especially targeted therapies (Plevritis et al., 2018). Obesity significantly increases mortality from certain cancers, causing 25 % of endometrial and 68 % of pancreatic cancer deaths in the U.S (Islami et al., 2018). Gender differences in mortality rates are affected by factors like living conditions, healthcare access, and changes in disease prevalence and risk behaviors (Yang and Kozloski, 2012). A multi-faceted approach with targeted interventions for various demographics is essential to address cancer mortality complexities.

Our study shows intermittent childhood cancer mortality Fig. 1. US data indicates rising incidence but declining mortality. Pediatric cancers vary by age; understanding factors influencing outcomes requires further research (Cronin et al., 2018). This age group warrants particular attention, as many young patients endure long-term consequences from both cancer and its treatment, significantly impacting their overall health and quality of life throughout their lives (Siegel et al., 2014).

Cancer mortality is increasing among premenopausal women, while postmenopausal women show lower incidence due to biological factors. Enhancing healthcare infrastructure, ensuring universal coverage, and fostering global collaborations are crucial to addressing these urgent challenges (Bizuayehu et al., 2024). Factors such as advanced maternal age, declining fertility, shorter breastfeeding periods, hormonal contraception, shift work, and chemical exposure contribute to rising cancer rates in reproductive-age women. Addressing these issues is crucial to reducing cancer mortality in premenopausal women (Andersen et al., 2017).

The study shows a shift in cancer mortality from 2017 to 2019: elderly women had higher death rates in 2017, but men surpassed them in 2018 and 2019. This aligns with Cronin et al. (2018), which reported high breast cancer deaths among elderly women and that prostate cancer mainly affects men aged 50 and older (Cronin et al., 2018). Additionally, stomach cancer mortality rates in men are about twice as high as in women (Weir et al., 2015; Weir et al., 2016). This disparity is concerning given the aging U.S. population, which sees 60 % of new cancer diagnoses and 73 % of cancer deaths in individuals aged 65 and older (Dyba et al., 2021). Gender differences in mortality may result from varying cancer prevalence; future research should investigate the underlying causes of these disparities.

Spatio-temporal cluster analysis of cancer mortality rates in Iran shows a shifting geographic distribution over time. It's crucial to examine the variations in cancer mortality clusters across different regions. Research by Faramarzi et al. (2024) indicates that certain areas in Iran are high-risk zones for specific cancers, influenced by detection and diagnosis rates (Faramarzi et al., 2024). Effective screening increases reported cancer incidence. Promoting prevention and equitable healthcare access can further reduce deaths (Hassanipour et al., 2018). High-risk areas require further investigation to understand the factors behind these disparities.

Study limitations included uncategorized cancer types, reliance on 2017–2019 census data, and restricted risk factor analysis (e.g., pollution, socio-economic status). County-level data also limited granular insights, highlighting the need for more detailed mortality and risk factor data. While this study uses pre-pandemic data, the slow progression of cancer mortality trends and the lack of comparable post-2019 datasets justify its relevance. Future studies should replicate these analyses when complete post-2022 data become available.

5. Conclusions

This study highlights concerning cancer mortality rates in Iran, contrasting with declines elsewhere like the U.S. Spatial and demographic analysis shows higher rates among men and premenopausal women, indicating diverse contributing factors. Ongoing research is essential, especially for vulnerable populations such as children and reproductive-age women. Addressing cancer mortality requires improving healthcare infrastructure, expanding universal coverage, and raising public awareness of lifestyle risk factors. By enhancing screening and treatment programs, Iran can reduce cancer-related deaths and improve health outcomes. Continued monitoring and research are vital to adapt strategies to the evolving challenges of cancer control in the region.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Alireza Zangeneh: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Project administration, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Arash Ziapour: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Software, Resources, Conceptualization. Seyede Negin Hoseini: Visualization, Validation, Resources. Babak Nazari: Resources, Investigation. Homa Molavi: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Formal analysis. Farid Najafi: Project administration, Data curation. Ardeshir Khosravi: Validation, Software, Project administration. Reza Heidari Moghadam: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Resources, Project administration.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Contributor Information

Alireza Zangeneh, Email: ali.zangeneh88@gmail.com.

Arash Ziapour, Email: arashziapoor@gmail.com.

Seyede Negin Hoseini, Email: Neginhosainiii@gmail.com.

Babak Nazari, Email: babnazari@yahoo.com.

Homa Molavi, Email: homa.molavi@manchester.ac.uk.

Farid Najafi, Email: faridn302@yahoo.com.

Ardeshir Khosravi, Email: ardeshir340@yahoo.com.

Reza Heidari Moghadam, Email: heidarymoghadam@yahoo.com.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Amini M., et al. Global pattern of trends in incidence, mortality, and mortality-to-incidence ratio rates related to liver cancer, 1990–2019: a longitudinal analysis based on the global burden of disease study. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):604. doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-12867-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen Z.J., et al. Long-term exposure to ambient air pollution and incidence of postmenopausal breast cancer in 15 European cohorts within the ESCAPE project. Environ. Health Perspect. 2017;125(10) doi: 10.1289/EHP1742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barke A., et al. Classification of chronic pain for the international classification of diseases (ICD-11): results of the 2017 International World Health Organization field testing. Pain. 2022;163(2):e310–e318. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bizuayehu H.M., et al. Global burden of 34 cancers among women in 2020 and projections to 2040: population-based data from 185 countries/territories. Int. J. Cancer. 2024;154(8):1377–1393. doi: 10.1002/ijc.34809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canfell K., et al. Mortality impact of achieving WHO cervical cancer elimination targets: a comparative modelling analysis in 78 low-income and lower-middle-income countries. Lancet. 2020;395(10224):591–603. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30157-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung K., Yang D.-H., Bell R. Health and GIS: toward spatial statistical analyses. J. Med. Syst. 2004;28:349–360. doi: 10.1023/b:joms.0000032850.04124.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronin K.A., et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of Cancer, part I: national cancer statistics. Cancer. 2018;124(13):2785–2800. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronin K.A., et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, part 1: national cancer statistics. Cancer. 2022;128(24):4251–4284. doi: 10.1002/cncr.34479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyba T., et al. The European cancer burden in 2020: incidence and mortality estimates for 40 countries and 25 major cancers. Eur. J. Cancer. 2021;157:308–347. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2021.07.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faramarzi S., et al. Cancer patterns in Iran: a gender-specific spatial modelling of cancer incidence during 2014–2017. BMC Cancer. 2024;24(1):191. doi: 10.1186/s12885-024-11940-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassanipour S., Fathalipour M., Salehiniya H. The incidence of prostate cancer in Iran: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prostate Int. 2018;6(2):41–45. doi: 10.1016/j.prnil.2017.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health, U.D.o. and H. Services . US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease …; Atlanta, GA: 2014. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. [Google Scholar]

- Henley S.J., et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, part I: national cancer statistics. Cancer. 2020;126(10):2225–2249. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong Y., Zeng M.L. International classification of diseases (ICD) KO Knowl. Organiz. 2023;49(7):496–528. [Google Scholar]

- Hu J., et al. Cancer burden attributable to risk factors, 1990–2019: a comparative risk assessment. Iscience. 2024;27(4) doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2024.109430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islami F., et al. Proportion and number of cancer cases and deaths attributable to potentially modifiable risk factors in the United States. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018;68(1):31–54. doi: 10.3322/caac.21440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jemal A., et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2005, featuring trends in lung cancer, tobacco use, and tobacco control. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2008;100(23):1672–1694. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murchie P., et al. Is place or person more important in determining higher rural cancer mortality? A data-linkage study to compare individual versus area-based measures of deprivation. International journal of population data. Science. 2021;6(1) doi: 10.23889/ijpds.v6i1.1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plevritis S.K., et al. Association of screening and treatment with breast cancer mortality by molecular subtype in US women, 2000-2012. Jama. 2018;319(2):154–164. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.19130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prager G.W., et al. Global cancer control: responding to the growing burden, rising costs and inequalities in access. ESMO open. 2018;3(2) doi: 10.1136/esmoopen-2017-000285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reshadat S., et al. A feasibility study of implementing the policies on increasing birth rate with an emphasis on socio-economic status: a case study of Kermanshah Metropolis, western Iran. Soc. Indic. Res. 2018;140:619–636. [Google Scholar]

- Sato A., et al. Increasing trends in the prevalence of prior cancer in newly diagnosed lung, stomach, colorectal, breast, cervical, and corpus uterine cancer patients: a population-based study. BMC Cancer. 2021;21:1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12885-021-08011-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel D.A., et al. Cancer incidence rates and trends among children and adolescents in the United States, 2001–2009. Pediatrics. 2014;134(4):e945–e955. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-3926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unwin D.J. GIS, spatial analysis and spatial statistics. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 1996;20(4):540–551. [Google Scholar]

- Wang F. Why public health needs GIS: a methodological overview. Ann. GIS. 2020;26(1):1–12. doi: 10.1080/19475683.2019.1702099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weir H.K., et al. The past, present, and future of cancer incidence in the United States: 1975 through 2020. Cancer. 2015;121(11):1827–1837. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weir H.K., et al. Peer reviewed: heart disease and cancer deaths—trends and projections in the United States, 1969–2020. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2016;13 doi: 10.5888/pcd13.160211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Kozloski M. Change of sex gaps in total and cause-specific mortality over the life span in the United States. Ann. Epidemiol. 2012;22(2):94–103. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2011.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanganeh A., et al. Evaluating the access of slum residents to healthcare centers in Kermanshah Metropolis, Iran (1996–2016): a spatial justice analysis. Heliyon. 2023;9(1) doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e12731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.