Summary

Chagas disease, caused by the protozoan parasite Trypanosoma cruzi, remains a significant public health challenge with evolving epidemiological patterns due to migration and globalization. While its cardiac complications are well-characterized, stroke represents an underrecognized yet devastating manifestation, occurring in 3%–20% of patients. Traditionally viewed primarily as a cardioembolic pathophysiology, emerging evidence suggests a more complex pathophysiologic mechanism involving inflammatory, prothrombotic, and microvascular processes. This narrative review examines the multifaceted mechanisms underlying stroke in Chagas disease, integrating recent insights into both cardiac and non-cardiac pathways. We analysed current approaches to risk stratification and prevention, including the utility of the IPEC-FIOCRUZ score and limitations in implementing anticoagulation strategies. This review also addresses emerging challenges, such as the aging of affected populations and limited disease recognition in non-endemic regions, while highlighting opportunities for improving care.

Keywords: Chagas cardiomyopathy, Stroke, Cardioembolism, Trypanosoma cruzi, Chagas disease

Chagas disease, caused by infection with the protozoan parasite Trypanosoma cruzi, remains a major public health challenge in Latin America and is increasingly recognized as a global health concern due to migration patterns.1 An estimated 6–7 million people are infected worldwide, mainly in endemic regions. However it is estimated that between 240,000 and 350,000 individuals are living with T. cruzi infection in the United States, with the highest concentrations in the states of California, New York, Washington D.C. and Florida.2 In Europe, Spain is estimated to have between 47,000 and 67,000 individuals infected with T. cruzi, primarily migrants from Bolivia, Ecuador, Argentina, and Paraguay.3 Approximately 20–30% of the patients with Chagas diseasewill develop chronic Chagas cardiomyopathy (CCC)–the most serious long-term sequela.1,4 While cardiac complications including heart failure and both brady–and tachyarrhythmias are well-characterized, the relationship between Chagas diseaseand stroke has garnered increasing attention in recent years.5

Stroke currently represents a leading cause of mortality and long-term disability in patients with Chagas disease, with its reported prevalence ranging from 3% to over 20% in different studies.6, 7, 8, 9, 10 Cardioembolic mechanisms related to Chagas cardiomyopathy, including left ventricular dysfunction, apical aneurysms, and atrial fibrillation, have long been considered the primary etiology.6,10 However, emerging evidence suggests a more complex pathophysiologic mechanism involving inflammatory, prothrombotic, and microvascular processes that may increase stroke risk even in patients without overt cardiac involvement.11,12

Despite its clinical relevance, many aspects of stroke in Chagas diseaseremain poorly understood, while significant challenges in risk stratification, optimal antithrombotic strategies, and management of acute stroke in this population persist.13 This review aims to provide a comprehensive overview of our current understanding of stroke in this neglected disease, highlighting recent advances in epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and management approaches. We also identify key knowledge gaps and future research directions to improve stroke prevention and outcomes in this unique patient population.

Methods

A literature search was conducted using the Medline (Ovid), EMBASE, and LILACS (Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature) databases. No language or date restrictions were applied to the searches to ensure a broad capture of relevant studies. The search strategy is available in Supplementary Text 1.

Additionally, the reference lists of retrieved articles and relevant review papers were manually screened to identify further potentially eligible studies. The selection of articles for inclusion was based on their relevance to the scope of this review, focusing on studies that elucidated the multifaceted aspects of stroke in Chagas disease, from basic pathophysiology to clinical management and future challenges.

Epidemiology of stroke in Chagas disease

The prevalence of stroke in Chagas disease and CCC exhibits considerable variability depending on the population studied and the methods used for detection. On one side, autopsy studies have revealed a strikingly high frequency of cerebral infarction in patients who died with a diagnosis of CCC, with stroke rates ranging from 5% to almost 20%.14, 15, 16, 17 The study of Aras et al., a retrospective autopsy study of 524 Patients with CCC, reported a prevalence of stroke of 17.5% (n = 92), with infarctions located predominantly in the cerebral hemispheres (89.1%), followed by the cerebellum (8.7%) and the hypophysis (2.2%). Interestingly, most of the patients with post-mortem stroke evidence were younger than 50 years (64%), while a clinical stroke diagnosis was only performed in 31% of the individuals, highlighting the significant burden of early subclinical cerebrovascular events.14 However, it is important to note that autopsy studies may overestimate the prevalence of stroke due to selection bias towards more severe cases.

On the other hand, epidemiological studies have consistently reported high incidence rates of stroke in Chagas diseaseand CCC.18, 19, 20, 21 Nunes et al. conducted a prospective study of 213 patients with CCC, finding an incidence rate of ischemic cerebrovascular events of 2.67 events per 100 patient-years.8 Similarly, Cerqueira-Silva et al. reported an incidence of stroke of 2.02 per 100 patient-years in a cohort of patients with Chagas disease and heart failure.21 When comparing these rates with those of patients without Chagas etiology, the meta-analysis by Cardoso et al., which included 4158 patients from eight studies, reported that the diagnosis of Chagas disease represents a factor independently associated with an increased risk of stroke (Odds ratio (OR) 2.10), with significance for patients with CCC (OR 1.74) but not for patients with the indeterminate form of the disease.10 These findings have been confirmed in subsequent studies such as the one of Cerqueira-Silva et al. (Cause specific hazard ratio for Chagas disease 2.54), even after multivariate adjustment.21 The consistency of this heightened risk across multiple studies underscores the complex pathophysiology of stroke in this condition, suggesting that factors beyond overt cardiac dysfunction may significantly contribute to cerebrovascular risk.

The etiology of stroke in Chagas diseaseis predominantly cardioembolic, with around 85–90% having evidence of cardioembolism according to the current evidence (Fig. 1).22, 23, 24 Nonetheless, other mechanisms have been identified, including large-artery atherosclerosis and small-vessel occlusion. Carod-Artal et al., in their comprehensive study of 94 patients with Chagas disease and stroke, reported a significantly higher prevalence of small-vessel disease in asymptomatic Chagas patients compared with those with CCC symptoms (15.6% vs. 3.8%), while cardioembolic sources were more prevalent in symptomatic disease cases (86.8% vs. 21.2%).24 Finally, the prevalence of embolic stroke of unknown source (Embolic stroke of undetermined source) was significantly higher in asymptomatic Chagas diseasecompared to CCC (54.5% vs. 1.9%).24 These findings suggest that stroke can be the initial manifestation of cardiovascular involvement in patients classified as being in the indeterminate form of Chagas disease. The high incidence of embolic stroke of undetermined source among asymptomatic patients underscores the potential for hidden embolic sources. Moreover, from a pathophysiological standpoint, this aligns with the understanding that sudden cardiac death not infrequently is first manifestation of Chagas disease in patients with no prior symptoms or known impaired left ventricular function, further emphasizing the silent yet severe nature of this condition.

Fig. 1.

Ischemic stroke in the territory of the left middle cerebral artery in a 72-year-old patient with atrial fibrillation, a newly diagnosed case of Chagas disease at the time of the stroke, and a preserved left ventricular ejection fraction of 55%.

Moreover, a relevant aspect of stroke epidemiology in Chagas disease is the apparent divergence from traditional vascular risk factors. Carod-Artal et al. reported that conventional risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and smoking were less frequent in patients with stroke and Chagas disease compared to the Control group.24 This observation has also been reported in multiple studies comparing patients with CCC with individuals with other cardiomyopathies,21,25,26 highlighting the Colombian Heart Failure Registry results, which indicated a significantly higher prevalence of arterial hypertension, sedentarism, type 2 diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease, dyslipidemia and valvular disease in patients with other etiologies of heart failurecompared to those with CCC.27 These results support the hypothesis that Chagas disease itself may confer a significant independent risk for stroke, potentially through mechanisms distinct from those in the general population. Box 1 summarizes relevant epidemiological and clinical key points of Chagas disease for clinicians.

Box 1. Chagas disease–key points.

Disease overview

-

•

Caused by the protozoan parasite Trypanosoma cruzi

-

•

Estimated 6–7 million people infected worldwide

-

•

Previously confined to Latin America; now seen globally due to migration

-

•

20–30% of infected individuals develop chronic cardiomyopathy

-

•

Annual stroke incidence: 2.67 events per 100 patient-years in cardiomyopathy patients

Clinical pearls

-

•

Stroke can be the first manifestation of previously undiagnosed Chagas disease

-

•

Chagas cardiomyopathy carries higher stroke risk vs. other heart failure etiologies

-

•

Cardioembolism accounts for 85–90% of strokes in Chagas disease

-

•Consider Chagas disease in patients from endemic areas with:

-

◦Cardioembolic stroke without traditional risk factors

-

◦Young age at stroke presentation (<50 years)

-

◦Apical aneurysm on cardiac imaging

-

◦Right bundle branch block + left anterior fascicular block on ECG

-

◦

Risk factors for stroke in Chagas disease

Multiple studies have evaluated the potential factors associated with stroke in patients with CCC beyond atrial fibrillation, with heterogeneous results obtained from multivariate analyses. Despite varied results, left ventricular ejection fraction has emerged as the most consistent independent risk factor. Moreira et al. reported that an ejection fraction below 40% was associated with a significantly increased risk of stroke (Hazard ratio (HR) 3.16; 95% CI 1.38–7.25), while Nunes et al. found a similar association with an ejection fraction below 35% (HR 3.22).9,28 Corroborating these findings, systolic dysfunction has been strongly linked to elevated stroke risk in studies by de Melo et al. (OR 9.49; 95% CI 3.08–23.24) and Sousa et al. (HR 13.21).6,29 Additionally, the presence of a left ventricular apical aneurysm has also been identified as a significant independent risk factor for stroke in Patients with CCC. This association has been demonstrated in multiple studies, including those by Nunes et al. (OR 2.19), Echeverría et al. (HR 5.64), and Sousa et al. (HR 2.32).

Furthermore, additional factors have been reported in the literature as potentially associated with this outcome of interest, including age >48 years, the presence of intraventricular thrombus, left atrial indexed volume, atrial fibrillation and the presence of conduction disturbances, among others.6,9

The identification of stroke risk factors in Patients with CCC, while crucial, presents significant challenges in translating this knowledge into actionable clinical recommendations. The complexity of this translation stems from the multifaceted nature of the disease and the variability in study outcomes. In this regard, only the study by Sousa AS et al. has generated a series of estimates of embolic risk based on the results of the risk factors. As a result of this analysis, the Instituto de Pesquisa Evandro Chagas/Fundação Oswaldo Cruz (IPEC/FIOCRUZ) score was created, which was designed to estimate the risk of cardioembolic stroke in patients with Chagas disease.29 The implications and practical application of the IPEC/FIOCRUZ score are explored in depth in the subsequent section, “Primary Prevention of Stroke in Chagas Disease.”

Cardioembolism mechanisms in Chagas disease

The increased risk of stroke in Chagas disease is primarily attributed to multiple cardioembolic mechanisms that develop as a consequence of T. cruzi infection and the subsequent cardiac remodeling. In relation to the previously mentioned factors associated with stroke in patients with Chagas disease, this section will explore in detail the key cardioembolic mechanisms, depicting why this condition, especially CCC, could lead to this high rate of stroke events.

Atrial arrhythmias

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is a well-established risk factor for cardioembolic stroke in Chagas disease, as well as in other settings. The prevalence of atrial fibrillation in Chagas cardiomyopathy patients ranges from 5 to 15%, being significantly higher than in the general population as well as in non-Chagas disease cardiomyopathy populations.30,31 This elevated prevalence can be attributed to several factors related to its pathophysiology.

Initially, chronic T. cruzi infection leads to progressive atrial fibrosis and dilatation, creating a strong arrhythmogenic substrate.12 The low-grade persistent parasitic infection triggers an inflammatory response that persists even after the acute phase, leading to ongoing tissue damage and fibrosis. This remodeling of the atria alters the electrical properties of the cardiac tissue, making it more susceptible to arrhythmias, particularly AF.32,33

Furthermore, Chagas disease often involves autonomic dysfunction with extensive parasympathetic denervation, which can directly promote atrial arrhythmias.34 The autonomic nervous system plays a crucial role in regulating heart rhythm, and its disruption in this setting can lead to the development of electrical instability phenomena.35 The loss of parasympathetic tone can result in unopposed sympathetic activity, well known to be proarrhythmic.36 Moreover, the persistent low-grade inflammation characteristic of chronic Chagas disease may also contribute to atrial electrical and structural remodeling.37,38 Inflammatory mediators can directly affect ion channel function and promote fibrosis, further enhancing the arrhythmogenic potential of the atrial tissue.39, 40, 41, 42

The mechanism by which atrial fibrillationpromotes thromboembolism in Chagas disease is similar to that in non-chagasic AF. Blood stasis in the left atrial appendage, endothelial dysfunction, and a prothrombotic state all contribute to thrombus formation.43 However, some studies suggest that Chagas disease patients with atrial fibrillation may have an even higher stroke risk compared to non-chagasic atrial fibrillation patients, possibly due to the additive effects of other cardiac abnormalities.44,45 For instance, a study by Carod-Artal et al. found that approximately 15% of patients with Chagas disease and stroke admitted to the hospital had atrial fibrillation. This prevalence is notably higher than what is typically observed in non-chagasic stroke patients of similar age.44 Moreover, a population-based cohort study showed that atrial fibrillation predicted the risk of stroke mortality in T. cruzi-infected older adults, underscoring the importance of this arrhythmia in the pathogenesis of stroke in this context.46

Left ventricular dysfunction

Left ventricular systolic dysfunction is a hallmark of CCC and an independent risk factor for stroke as mentioned before. The mechanisms linking left ventricular dysfunction to increased stroke risk are multifaceted and interrelated.

Reduced left ventricle ejection fraction leads to blood stasis, particularly in the apex, promoting thrombus formation. As the myocardium's pumping efficiency decreases, areas of slow blood flow develop, especially in regions of the ventricle that are most affected by the disease process.47,48 The apical region of the left ventricle is particularly susceptible in CCC, due to its structural and vascular characteristics making it more vulnerable to ischemic damage and inflammation caused by T. cruzi, often showing the most severe dysfunction and remodeling.49, 50, 51

Systolic dysfunction is also highly correlated with the activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) and sympathetic nervous system. This neurohormonal activation, while initially compensatory in the course of the disease, has deleterious effects over time. In the setting of stroke, it may enhance platelet activation and promote a procoagulant state, further increasing the risk of thrombus formation.52, 53, 54 The chronic activation of these systems can also lead to endothelial dysfunction, another factor that contributes to a prothrombotic state through various mechanisms.55,56 Endothelial cells play a crucial role in maintaining vascular homeostasis, and their dysfunction leads to increased expression of adhesion molecules, reduced production of nitric oxide, and altered balance of pro- and anti-thrombotic factors.57, 58, 59

Studies have shown that the risk of stroke increases progressively with declining ejection fraction in Chagas disease patients. For instance, Nunes et al. found that ejection fraction was an independent predictor of ischemic cerebrovascular events in Patients with CCC, with a hazard ratio of 0.95 (decrease in the risk of stroke) for each 1% increase in ejection fraction, meaning that a better ejection fraction is associated with a lower risk of this outcome.9 Moreover, the severity of left ventricular dysfunction often correlates with the extent of myocardial fibrosis and remodeling in Chagas disease.60 As the disease progresses, the risk of thromboembolic events increases not only due to the hemodynamic consequences of reduced ejection fraction but also because of the structural changes that create a more thrombogenic cardiac milieu. It's important to note that even patients with mild to moderate left ventricular dysfunction may be at increased risk of stroke in Chagas disease.24 This highlights the need for careful evaluation and risk stratification in all patients with CCC, not just those with moderate to severe heart failure.

Apical aneurysms and intracardiac thrombi

Left ventricular aneurysms, especially those located in the apex, are a characteristic feature of CCC, occurring in 30–50% of patients with severe left ventricular systolic dysfunction.50,51 These aneurysms significantly increase the risk of cardioembolic events through several mechanisms, making them a crucial factor in the elevated stroke risk observed in this context.61,62

The formation of aneurysms in CCC is thought to be related to anatomical particularities of the apex and the basal inferolateral segment, combined with the effects of chronic inflammation and myocardial fibrosis.63 As the disease progresses, the affected segments become increasingly dysfunctional, leading to thinning of the myocardium and eventual aneurysm formation.64,65

Similar to the left ventricular dysfunction mechanism, one of the primary ways in which apical aneurysms contribute to embolic risk is by creating regions of blood stasis. The dyskinetic or akinetic aneurysm essentially forms a pocket where blood flow is significantly reduced.66 This stagnant blood is highly prone to thrombus formation, as per Virchow's triad of thrombogenesis (blood stasis, hypercoagulability, and endothelial injury). The longer blood remains static, the higher the likelihood of clot formation.67 Furthermore, the endocardium lining the aneurysm is often affected due to the extensive, transmural remodeling of the segment. This stretched and thinned endocardium may be more susceptible to injury, potentially exposing prothrombotic subendocardial layers, which can trigger the coagulation cascade and promote platelet adhesion, further increasing the risk of thrombus formation.68

The importance of apical aneurysms in stroke risk is underscored by several studies. Carod-Artal et al. found that 37% of Chagas disease patients with stroke had apical aneurysms, compared to only 0.7% in non-chagasic stroke patients, while another study revealed no differences in the prevalence of apical aneurysms between symptomatic and asymptomatic patients, highlighting the relevance of multimodal cardiovascular assessment even in this patient population.9,24,44 These striking results highlight the significant role that apical aneurysms play in the pathogenesis of stroke in Chagas disease.29

It's worth noting that the risk associated with apical aneurysms may be further modulated by factors such as aneurysm size, the presence of a thrombus within the aneurysm, and the overall left ventricular function.62,67 Larger aneurysms and those containing visible thrombus on imaging studies are generally associated with a higher risk of embolic events.69,70 Regarding these last, the prevalence of mural thrombi in Chagas cardiomyopathy varies widely in different studies, ranging from 11 to 44%.9,15,28,71 This variability likely reflects differences in patient populations, disease severity, and imaging techniques used for detection. Importantly, the presence of a mural thrombus is a powerful predictor of stroke risk. In a study by Nunes et al., the detection of left ventricular thrombus on echocardiography was associated with a 2.4-fold increased risk of stroke in Chagas disease patients.9

The risk of embolization from mural thrombi depends on several factors, including thrombus size, mobility, and location.72,73 Larger, more mobile thrombi are generally considered to pose a higher embolic risk.72,74 The composition of the thrombus may also play a role, with fresher, less organized thrombi potentially being more prone to fragmentation and embolization.67,73 Detection of intracardiac thrombi can be challenging and often requires multimodality imaging (Fig. 2). While transthoracic echocardiography is the first-line imaging modality, it may miss smaller thrombi or those in difficult-to-image locations even with the use of ultrasound-enhancing-agents.67,75 Transesophageal echocardiography does not improve visualization of the apex of the left ventricle, being disregarded as a secondary imaging modality in this setting.73 In recent years, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMRI), especially using late gadolinium enhancement imaging, has emerged as a valuable tool for thrombus detection, offering high sensitivity and specificity, especially for left ventricular thrombi.76 CMRI has proven superior to echocardiography in detecting left ventricular thrombus, as reported by a meta-analysis of three studies.77 Furthermore, detection of thrombi by CMRI has been associated with increased short- and long-term embolic events, highlighting its prognostic utility.70,78 In the setting of Chagas disease and CCC, the study of Neri et al. highlighted that, in patients with embolic stroke of undetermined source, positive serology for T. cruzi was associated with the presence and burden of abnormalities in CMRI, including the finding of an embolic source (OR = 4.96) and number of embolic sources (OR = 7.02).

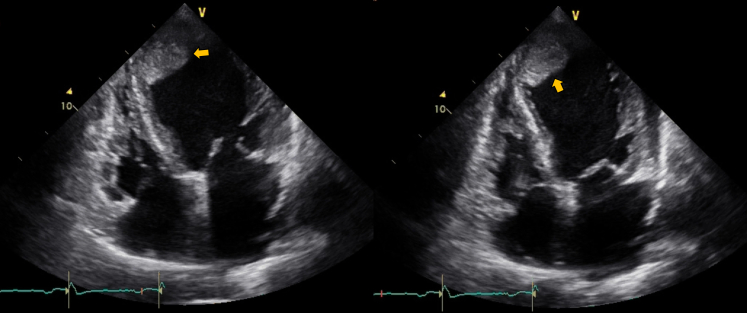

Fig. 2.

Apical intraventricular thrombus with digitating extension towards the mid-segment parallel to the septum in a 65-year-old patient with chronic Chagas cardiomyopathy, left ventricular ejection fraction of 16% and an ICD. A large thrombus (axis greater than 12 cm2) with a firm base but mobile edges of emboligenic risk is observed in 2D transthoracic echocardiography (arrows).

Endothelial dysfunction and prothrombotic state

Beyond the structural cardiac abnormalities, Chagas disease is associated with a more generalized prothrombotic state that may contribute to cardioembolic events.11 This prothrombotic milieu is characterized by endothelial dysfunction, platelet activation, alterations in coagulation factors, and the effects of inflammatory mediators.79,80

Chronic T. cruzi infection and the associated inflammatory response can directly damage the endothelium.80,81 Additionally, the hemodynamic changes associated with cardiac dysfunction can lead to altered shear stress, further compromising endothelial function.80 Dysfunctional endothelium exhibits reduced production of nitric oxide and increased expression of adhesion molecules, promoting platelet adhesion and activation of the coagulation cascade.82,83

Studies have shown increased platelet activation and aggregation in Chagas disease patients.84, 85, 86 This heightened platelet reactivity is likely due to a combination of factors, including endothelial damage, increased shear stress in areas of altered blood flow, and the effects of inflammatory mediators. Activated platelets not only contribute directly to thrombus formation but also release proinflammatory and procoagulant factors, further exacerbating the prothrombotic state.79,87,88 Moreover, Chagas disease has also been associated with alterations in the balance of pro- and anticoagulant factors.79 Some studies have reported increases in procoagulant factors such as fibrinogen and factor VIII, while others have found decreases in anticoagulant factors like protein C and protein S.11 However, the exact nature and clinical significance of these alterations remain areas of ongoing investigation.

Autonomic dysfunction

Chagas disease and CCC frequently involve damage to the cardiac autonomic nervous system, particularly parasympathetic denervation.89, 90, 91 This autonomic dysfunction, while not a direct cause of cardioembolism, may contribute to the overall risk through several mechanisms.92

Parasympathetic denervation in Chagas disease is thought to result from direct damage to autonomic ganglia and nerve fibers by T. cruzi, as well as from inflammatory processes and autoimmune responses.89,93, 94, 95 The resulting autonomic imbalance, characterized by relative sympathetic predominance, can have several consequences that potentially increase stroke risk. One of the primary ways in which autonomic dysfunction may contribute to cardioembolic risk is through the promotion of atrial arrhythmias, particularly atrial fibrillation.96 The imbalance of sympathetic to parasympathetic tone can lead to electrical instability in the atria, enhancing the susceptibility to atrial arrhythmias (Fig. 3).97 This mechanism may partly explain the high prevalence of atrial fibrillation observed in Chagas disease and patients with CCC.

Fig. 3.

Pathophysiological mechanisms contributing to the elevated stroke risk in Chronic Chagas Cardiomyopathy. PAI-1, Plasminogen Activator Inhibitor-1; F1 + 2, Prothrombin Fragment 1 + 2; ETP, Endogenous Thrombin Potential; LV, Left Ventricular.

Beyond embolism: T. cruzi infection and the brain

While cardioembolism has long been considered the primary mechanism for stroke in Chagas disease, emerging evidence suggests that T. cruzi infection may have direct and indirect effects on the central nervous system (CNS) that could increase stroke risk independently of cardiac involvement.98 In this regard, recent studies have elucidated complex interactions between the parasite, host immune responses, and the CNS, providing new insights into the pathogenesis of cerebrovascular complications in Chagas disease.99, 100, 101

T. cruzi has been shown to directly invade the CNS during both acute and chronic phases of the infection.99,102,103 In experimental models, parasites have been detected in various cell types and brain regions, including glial cells, neuronal somas, and capillary endothelial cells of the cerebral and cerebellar cortices, as well as in the thalamic subcortical nucleus.104, 105, 106 CNS parasitemia can lead to local inflammatory responses and structural changes that may increase stroke risk.107,108 Notably, parasites and inflammatory changes have been observed in the basal ganglia even when parasitemia is no longer detectable, suggesting persistent CNS involvement throughout the course of infection.102

Moreover, the blood–brain barrier and the blood-cerebrospinal fluid barrier play a crucial role in Chagas disease neuropathogenesis, as T. cruzi infection can disrupt its integrity through multiple mechanisms. This hypothesis is derived from the observation of parasites in the choroid plexus, hippocampus, and below the pia mater in ependymal cells forming the glia limitans.109, 110, 111 These findings indicate that T. cruzi exhibits the ability to penetrate the endothelial lining of venules located in the leptomeninges. Subsequently, it can migrate through the pia mater, and ultimately gain access to the brain parenchyma.102,105

At the molecular level, T. cruzi infection triggers a robust immune response characterized by the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), interleukin 1β, and interferon-γ.12,112 These cytokines can also have significant effects on the CNS, even in the absence of direct parasitic invasion.113, 114, 115 Systemic inflammation can lead to activation of brain endothelial cells, increasing the expression of adhesion molecules and facilitating the recruitment of inflammatory cells into the CNS.116,117 This process can result in chronic neuroinflammation, which has been associated with increased stroke risk through various mechanisms, including endothelial dysfunction and glial activation.118, 119, 120

Oxidative stress is another critical factor in Chagas disease-related cerebrovascular risk. T. cruzi infection is associated with increased oxidative stress, both systemically and within the CNS.121,122 The parasite itself and the host's immune response generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS).123,124 Elevated levels of these reactive species can lead to lipid peroxidation of cell membranes, oxidative damage to DNA and proteins, and activation of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs). These oxidative stress-related processes can contribute to vascular damage and increase susceptibility to ischemic events in the brain.125,126

Primary prevention of stroke in Chagas disease

Primary prevention of stroke in patients with CCC involves periodic cardiac evaluation to identify both those patients with undetermined stage T. cruzi infection who may benefit from trypanocidal therapy (infection control) and those with early cardiomyopathy and risk factors for cerebrovascular events even before the onset of symptoms (early detection). This includes annual or biannual electrocardiograms and periodic echocardiographic evaluations to detect structural abnormalities such as left ventricular dysfunction, apical aneurysms, and intracavitary thrombus.4,127 Furthermore, atrial fibrillation should be actively screened for during follow-up, with recommended annual electrocardiogram (ECG) assessments including a 30-s recording to facilitate the detection of atrial fibrillation. In cases of suspected paroxysmal arrhythmias, 24-h Holter monitoring and potentially longer term recordings should be performed.4,127

Regarding available risk stratification tools, the IPEC-FIOCRUZ score represents the only available scoring system, being developed to assess the risk of cardioembolic ischemic stroke in patients with Chagas disease and guide preventive strategies.29 The score incorporates four independent variables (Box 2). Based on the total score (0–5 points), patients are stratified into risk categories. The score recommends warfarin anticoagulation for high-risk patients (4–5 points) where the annual incidence of stroke (4.4%) outweighs the risk of major bleeding (approximately 2%). For moderate-risk patients (3 points), either warfarin or aspirin is suggested based on individual assessment. Low-risk patients (2 points) may receive aspirin or no prophylaxis, while very low-risk patients (0–1 points) do not require prophylaxis. This scoring system allows for targeted prevention strategies, potentially preventing about 45% of cardioembolic strokes by anticoagulating only 7.3% of the Chagas disease population.29,128 However, the IPEC-FIOCRUZ score is limited by the lack of clarity on variables including ‘primary alteration of ventricular repolarization’ and limited sample size, with current guidelines acknowledging the need for review and external validation of this score, particularly for its specific application in patients with CCC (excluding those with the indeterminate form of Chagas disease).127,128

Box 2. Stroke risk stratification and management in Chagas disease.

Risk stratification

IPEC-FIOCRUZ score components:

-

•

Systolic dysfunction–(e.g. LVEF <40%) (2 points)

-

•

Apical aneurysm (1 point)

-

•

Primary alteration of ventricular repolarization (1 point)

-

•

Age >48 years (1 point)

High risk (4–5 points): Consider anticoagulation.

Moderate risk (3 points): Individualize decision.

Low risk (0–2 points): No prophylaxis needed.

Key risk factors for stroke

-

•

Left ventricular ejection fraction <40%

-

•

Presence of apical aneurysm

-

•

Atrial fibrillation

-

•

Mural thrombus

Practice recommendations

-

•

Screen for Chagas disease in at-risk populations with stroke

-

•

Consider multimodality cardiac imaging for thorough evaluation

-

•

Regular monitoring of cardiac function and rhythm

-

•

Coordinate care with infectious disease and cardiology specialists

-

•

Consider specialized rehabilitation programs

For patients with atrial fibrillation, the guidelines recommend using the CHA2DS2-VASc score to guide anticoagulation decisions, similar to other cardiopathies. Oral anticoagulation is strongly recommended (level of evidence B) for patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc score ≥2 for women or ≥1 for men. In patients with mural thrombi detected on echocardiography, oral anticoagulation is recommended with a strong recommendation grade, albeit with a level of evidence C, reflecting the limited specific data in Chagas disease patients.127

Secondary prevention of Stroke in Chagas Disease patients

Based on the Brazilian guideline on the diagnosis and treatment of patients with CCC, oral anticoagulation in patients with atrial fibrillation and a CHA2DS2-VASc score ≥2 (or ≥1 for men) is strongly recommended. The presence of mural thrombi or a previous ischemic stroke also warrants anticoagulation. Warfarin, with a target international normalized ratio of 2–3, remains the most widely used option, though direct oral anticoagulants may be considered in select cases. However, these medications are not yet recommended for cases of ventricular thrombi or mechanical valves due to the limited available evidence.129,130 Supporting these recommendations, a recent meta-analysis demonstrated that anticoagulation therapy was associated with a significantly reduced likelihood of stroke in Chagas disease patients (OR 0.28). The initiation of anticoagulation post-stroke requires careful timing. For transient ischemic attacks, anticoagulation may commence 24 h after onset. In cases of established ischemic stroke, initiation is typically delayed for 3–14 days, depending on infarct size and severity, always contingent upon exclusion of hemorrhagic transformation.127

Furthermore, regular cardiac assessment with transthoracic echocardiography and 24-h Holter monitoring is advised to detect potential sources of embolism.4 For patients with implantable cardiac devices, interrogation of event recordings is crucial to identify arrhythmias. Additionally, current guidelines stress the importance of managing modifiable cardiovascular risk factors, including hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia, as well as lifestyle modifications such as smoking cessation and regular physical activity in this population.131 Interestingly, there is mixed evidence regarding the relationship between Chagas disease and these traditional cardiovascular risk factors. Some studies have suggested a potential association between Chagas disease and hypertension, with reported prevalence rates varying from 16.8% to 34% depending on disease stage, though the clinical significance of this relationship requires further investigation.132, 133, 134, 135 Similarly, while experimental studies have proposed theoretical mechanisms linking T. cruzi infection to metabolic abnormalities through effects on pancreatic and adipose tissue,136,137 large clinical studies have not demonstrated significant associations between Chagas disease and diabetes mellitus, insulin resistance, or metabolic syndrome.138 These findings suggest that any metabolic effects of chronic T. cruzi infection may not translate into clinically relevant glucose abnormalities in most patients. Optimal management of these patients necessitates a multidisciplinary approach, integrating expertise from neurology, cardiology, and infectious disease specialties. Comprehensive rehabilitation programs play a crucial role in functional recovery and should be initiated early in the course of treatment.127

The role of trypanocidal therapy in secondary stroke prevention remains a highly debated question. While the potential for a prothrombotic state resulting from chronic T. cruzi infection is acknowledged, the evidence on whether antiparasitic treatment reduces stroke risk in the absence of overt cardiac involvement is scarce and inconclusive.139, 140, 141 The BENEFIT Trial (Evaluation of the Use of Antiparasital Drug (Benznidazole) in the Treatment of Chronic Chagas’ Disease) did not observe a significant effect of benznidazole on stroke or other thromboembolic events in patients with CCC, and the potential benefit in patients with established cardiomyopathy remains unproven. Given that the vast majority of patients with Chagas disease and stroke have already developed CCC, which may limit the efficacy of trypanocidal therapy in reducing thrombotic risk, the role of infection control with anthelmintics in secondary stroke prevention requires further investigation.

Despite these general recommendations, there is a notable paucity of high-quality evidence specifically addressing secondary stroke prevention strategies in Chagas disease and Patients with CCC. The guidelines largely extrapolate from studies on other cardioembolic conditions, particularly those related to non-valvular atrial fibrillation.4,127 This approach, while pragmatic, may not fully account for the unique pathophysiology of this cardiomyopathy, including its propensity for ventricular arrhythmias and apical aneurysms.128 Moreover, there is a lack of randomized controlled trials evaluating the efficacy and safety of direct oral anticoagulants compared to warfarin in this population. Additionally, RCT data comparing warfarin with aspirin or no antithrombotic therapy for stroke prevention in Chagas disease patients is also lacking. Finally, the optimal management of patients with preserved ejection fraction but regional wall motion abnormalities remains unclear. These gaps highlight the urgent need for targeted research to develop tailored secondary prevention strategies for stroke in this special population.

Stroke rehabilitation in Chagas disease patients

Comprehensive exercise-based training rehabilitation programs have shown to significantly improve clinical parameters and patient self-reported outcomes in patients with CCC.131 Nevertheless, there is scarce evidence of stroke rehabilitation programs in this population. In this setting, the study of Montanaro VVA et al. assessed 279 patients with Chagas disease and ischemic stroke admitted to a stroke rehabilitation network in Brazil between January 2009 and December 2013.132 It reported that 75% did not have a previous Chagas disease diagnosis before being admitted to the programs, highlighting the high rates of underdiagnosis in this setting. In this cohort, they reported a mortality of 10% and a recurrence of 25%, with the clinical characteristics of the patients being similar to what has been reported in other stroke rehabilitation settings.133, 134, 135 Despite the limited evidence in this context, patients with Chagas disease may be exposed to lower odds of being referred to a stroke rehabilitation program in multiple contexts, mainly due to the disease affecting mainly poor populations in countryside areas of developing countries and also carrying a significant socioeconomic burden. On the other hand, if referred to a specialized program, patients with CCC could have a potentially worse prognosis compared to patients with other etiologies of heart failure, as Patients with CCC have exhibited reduced peripheral blood flow and more severe impairment in muscle strength, a predictor of stroke rehabilitation outcomes.136, 137, 138 Therefore, it is crucial to perform studies to assess the access of Chagas disease patients to specialized stroke rehabilitation programs, as well as the efficacy of these interventions in this special population.

Challenges and opportunities in stroke prevention and management in Chagas disease

The prevention and management of stroke in Chagas disease presents distinct challenges while offering opportunities for improved care. A significant demographic shift is occurring in endemic regions, with an aging Chagas disease population facing elevated stroke risk due to the convergence of age-related cardiovascular factors with chronic Chagas disease manifestations.142, 143, 144 The combination of increasing life expectancy with the natural progression of cardiac complications decades after initial infection creates a growing high-risk population requiring adapted prevention strategies.145

The globalization of Chagas disease through migration has created challenges in non-endemic regions, where healthcare providers often have limited experience with the disease. This lack of recognition may result in delayed diagnosis and inadequate risk stratification, particularly important since stroke may be the first manifestation of previously undiagnosed Chagas disease.146, 147, 148 In this context, educational initiatives aimed at increasing awareness among healthcare personnel have shown promise in improving outcomes.146,149 On the other hand, implementation challenges include limited access to specialized healthcare in endemic regions and the cost of newer anticoagulants.

Despite these challenges, several opportunities exist for improvement. Telemedicine can extend specialized care to remote areas and improve monitoring of at-risk patients, while research into novel biomarkers may enable more precise risk stratification and personalized prevention strategies.150,151 The growing recognition of Chagas disease in non-endemic regions provides opportunities for developing integrated care pathways that combine infectious disease, cardiac, and neurological expertise. Furthermore, international collaboration in Chagas disease research offers the potential for larger, more definitive trials to address critical evidence gaps in stroke prevention and management (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Summary of key aspects of stroke in Chagas disease. CCC, Chronic Chagas Cardiomyopathy; NCC, Non-Chagas Cardiomyopathy; Heart Failure, Heart Failure; LV, Left Ventricular.

Contributors

Conceptualization: LEE, AYS, LZR, FS, MN, LA, SAG, CAM; Data curation: AYS, MN; Funding acquisition: LEE, SAG; Investigation: LEE, AYS, LZR, MN, LA, SAG, CAM; Methodology: AYS, LZR, MN, SAG, CAM; Project administration: LEE, SAG; Resources: LA, SAG; Supervision: LEE, FS, LA, CAM; Validation: LEE, AYS, LZR, FS, SAG; Visualization: AYS, SAG; Writing—original draft: AYS, LZR, SAG; Writing—review & editing: LEE, AYS, LZR, FS, MN, LA, SAG, CAM; Decision to submit the manuscript: LEE.

Declaration of interests

Drs. Echeverría, Rojas, and Gómez-Ochoa report grants from the Ministry of Science and Technology of Colombia (Minciencias), Pfizer Pharmaceuticals, Novartis Pharma, and Boehringer Ingelheim. Drs. Echeverría, Serrano-García, Rojas, Silva-Sieger, and Gómez-Ochoa report employment by Fundación Cardiovascular de Colombia, Floridablanca, Colombia. Dr. Aguilera reports employment by Instituto Cardiovascular de Mínima Invasión, Jalisco, Mexico. Dr. Gómez-Ochoa reports employment by Uniklinikum Heidelberg. Dr. Morillo reports grants from Novartis, Medtronic, Abbott.

Acknowledgements

The present study was funded through the EMRISTA (Emerging Markets Thrombosis Investigator-Initiated Research Program) call by Pfizer, Inc. Independent research initiative agreement number 2019-024 (The Clot-Chagas Study). The funder had no role in the study design, data collection, and analysis, decision publishing, or manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

Disclaimer: This summary is available in Spanish in the Supplementary Material.

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lana.2025.101203.

Contributor Information

Luis E. Echeverría, Email: luisecheverria@fcv.org.

Carlos A. Morillo, Email: carlos.morillo@ucalgary.ca.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Gómez-Ochoa S.A., Rojas L.Z., Echeverría L.E., Muka T., Franco O.H. Global, regional, and national trends of chagas disease from 1990 to 2019: comprehensive analysis of the global burden of disease study. Glob Heart. 2022;17:59. doi: 10.5334/gh.1150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Irish A., Whitman J.D., Clark E.H., Marcus R., Bern C. Updated estimates and mapping for prevalence of chagas disease among adults, United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2022;28:1313–1320. doi: 10.3201/eid2807.212221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Velasco M., Gimeno-Feliú L.A., Molina I., et al. Screening for trypanosoma cruzi infection in immigrants and refugees: systematic review and recommendations from the Spanish society of infectious diseases and clinical microbiology. Euro Surveill. 2020;25 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.8.1900393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nunes M.C.P., Beaton A., Acquatella H., et al. Chagas cardiomyopathy: an update of current clinical knowledge and management: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018;138:e169–e209. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martínez-Salio A., Calleja-Castaño P., Valle-Arcos M.D., Sánchez-Sánchez C., Díaz-Guzmán J., Salto-Fernández E. [Chagas disease and stroke code: an imported case] Rev Neurol. 2011;53:60–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Melo E.S., de Paiva Bezerra R., de Holanda A.C., et al. Chagas disease stroke and associated risk factors: a case-control study. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2024;33 doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2023.107463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Henao-Martínez A.F., Olivo-Freites C., Higuita N.I.A., et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of chagas disease in the United States: a multicenter retrospective analysis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2023;109:1006–1011. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.23-0361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nunes M.C.P., Barbosa M.M., Ribeiro A.L.P., Barbosa F.B.L., Rocha M.O.C. Ischemic cerebrovascular events in patients with Chagas cardiomyopathy: a prospective follow-up study. J Neurol Sci. 2009;278:96–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2008.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nunes M.C.P., Kreuser L.J., Ribeiro A.L., et al. Prevalence and risk factors of embolic cerebrovascular events associated with Chagas heart disease. Glob Heart. 2015;10:151–157. doi: 10.1016/j.gheart.2015.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cardoso R.N., Macedo F.Y.B., Garcia M.N., et al. Chagas cardiomyopathy is associated with higher incidence of stroke: a meta-analysis of observational studies. J Card Fail. 2014;20:931–938. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2014.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Echeverría L.E., Rojas L.Z., Gómez-Ochoa S.A. Coagulation disorders in Chagas disease: a pathophysiological systematic review and meta-analysis. Thromb Res. 2021;201:73–83. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2021.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bonney K.M., Luthringer D.J., Kim S.A., Garg N.J., Engman D.M. Pathology and pathogenesis of chagas heart disease. Annu Rev Pathol. 2019;14:421–447. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-020117-043711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carod-Artal F.J. Policy implications of the changing epidemiology of Chagas disease and stroke. Stroke. 2013;44:2356–2360. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.000738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aras R., da Matta J.A.M., Mota G., Gomes I., Melo A. Cerebral infarction in autopsies of chagasic patients with heart failure. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2003;81(414–416):411–413. doi: 10.1590/s0066-782x2003001200008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oliveira J.S.M., Correa De Araujo R.R., Navarro M.A., Muccillo G. Cardiac thrombosis and thromboembolism in chronic chagas' heart disease. Am J Cardiol. 1983;52:147–151. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(83)90085-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arteaga-Fernández E., Barretto A.C., Ianni B.M., et al. [Cardiac thrombosis and embolism in patients having died of chronic Chagas cardiopathy] Arq Bras Cardiol. 1989;52:189–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Albanesi Filho F.M., Gomes Filho J.B. [Thromboembolism in patients with apical lesion caused by chronic chagasic cardiopathy] Rev Port Cardiol. 1991;10:35–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pereira Nunes M. do C., Barbosa M.M., Ribeiro A.L.P., Amorim Fenelon L.M., Rocha M.O.C. Predictors of mortality in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy: relevance of chagas disease as an etiological factor. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2010;63:788–797. doi: 10.1016/s1885-5857(10)70163-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paixão L.C., Ribeiro A.L., Valacio R.A., Teixeira A.L. Chagas disease: independent risk factor for stroke. Stroke. 2009;40:3691–3694. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.560854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.da Matta J.A.M., Aras R., de Macedo C.R.B., da Cruz C.G., Netto E.M. Stroke correlates in chagasic and non-chagasic cardiomyopathies. PLoS One. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cerqueira-Silva T., Gonçalves B.M., Pereira C.B., et al. Chagas disease is an independent predictor of stroke and death in a cohort of heart failure patients. Int J Stroke. 2022;17:180–188. doi: 10.1177/17474930211006284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Paiva Bezerra R., de Miranda Alves M.A., Conforto A.B., Rodrigues D.L.G., Silva G.S. Etiological classification of stroke in patients with chagas disease using TOAST, causative classification system TOAST, and ASCOD phenotyping. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2017;26:2864–2869. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2017.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dias Junior J.O., da Costa Rocha M.O., de Souza A.C., et al. Assessment of the source of ischemic cerebrovascular events in patients with Chagas disease. Int J Cardiol. 2014;176:1352–1354. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.07.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carod-Artal F.J., Vargas A.P., Falcao T. Stroke in asymptomatic Trypanosoma cruzi-infected patients. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2011;31:24–28. doi: 10.1159/000320248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shen L., Ramires F., Martinez F., et al. Contemporary characteristics and outcomes in chagasic heart failure compared with other nonischemic and ischemic cardiomyopathy. Circ Heart Fail. 2017;10 doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.117.004361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Braga J.C.V., Reis F., Aras R., et al. Is Chagas cardiomyopathy an independent risk factor for patients with heart failure? Int J Cardiol. 2008;126:276–278. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.01.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Echeverría L.E., Saldarriaga C., Rivera-Toquica A.A., et al. Characterization of patients with heart failure of chagas etiology in Colombia: an analysis based on the Colombian registry of heart failure (RECOLFACA) Curr Probl Cardiol. 2023;48 doi: 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2023.101964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moreira H.T., Volpe G.J., Mesquita G.M., et al. Association of left ventricular abnormalities with incident cerebrovascular events and sources of thromboembolism in patients with chronic Chagas cardiomyopathy. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2022;24:52. doi: 10.1186/s12968-022-00885-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sousa AS de, Xavier S.S., Freitas GR de, Hasslocher-Moreno A. Prevention strategies of cardioembolic ischemic stroke in Chagas' disease. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2008;91:306–310. doi: 10.1590/s0066-782x2008001700004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rojas L.Z., Glisic M., Pletsch-Borba L., et al. Electrocardiographic abnormalities in Chagas disease in the general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cardoso R., Garcia D., Fernandes G., et al. The prevalence of atrial fibrillation and conduction abnormalities in chagas' disease: a meta-analysis: ECG findings in chagas' disease. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2016;27:161–169. doi: 10.1111/jce.12845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Benchimol-Barbosa P.R., Barbosa-Filho J. Atrial mechanical remodeling and new onset atrial fibrillation in chronic Chagas' heart disease. Int J Cardiol. 2008;127:e113–e115. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.04.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saraiva R.M., Pacheco N.P., Pereira T.O.J.S., et al. Left atrial structure and function predictors of new-onset atrial fibrillation in patients with chagas disease. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2020;33:1363–1374.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2020.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Brito A.S.X., Moll-Bernardes R.J., Pinheiro M.V.T., et al. Autonomic denervation, myocardial hypoperfusion and fibrosis may predict ventricular arrhythmia in the early stages of Chagas cardiomyopathy. J Nucl Cardiol. 2023;30:2379–2388. doi: 10.1007/s12350-023-03281-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Linz D., Elliott A.D., Hohl M., et al. Role of autonomic nervous system in atrial fibrillation. Int J Cardiol. 2019;287:181–188. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.11.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vandenberk B., Haemers P., Morillo C. The autonomic nervous system in atrial fibrillation—pathophysiology and non-invasive assessment. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2024;10 doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2023.1327387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ihara K., Sasano T. Role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of atrial fibrillation. Front Physiol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fphys.2022.862164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nso N., Bookani K.R., Metzl M., Radparvar F. Role of inflammation in atrial fibrillation: a comprehensive review of current knowledge. J Arrhythm. 2020;37:1–10. doi: 10.1002/joa3.12473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lazzerini P.E., Laghi-Pasini F., Acampa M., et al. Systemic inflammation rapidly induces reversible atrial electrical remodeling: the role of interleukin-6-mediated changes in connexin expression. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.118.011006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Villegas S., Villarreal F.J., Dillmann W.H. Leukemia Inhibitory Factor and Interleukin-6 downregulate sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase (SERCA2) in cardiac myocytes. Basic Res Cardiol. 2000;95:47–54. doi: 10.1007/s003950050007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tanaka T., Kanda T., Takahashi T., Saegusa S., Moriya J., Kurabayashi M. Interleukin-6-induced reciprocal expression of SERCA and natriuretic peptides mRNA in cultured rat ventricular myocytes. J Int Med Res. 2004;32:57–61. doi: 10.1177/147323000403200109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hagiwara Y., Miyoshi S., Fukuda K., et al. SHP2-mediated signaling cascade through gp130 is essential for LIF-dependent I CaL, [Ca2+]i transient, and APD increase in cardiomyocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007;43:710–716. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kamel H., Okin P.M., Elkind M.S.V., Iadecola C. Atrial fibrillation and mechanisms of stroke: time for a new model. Stroke. 2016;47:895–900. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.012004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Carod-Artal F.J., Vargas A.P., Horan T.A., Nunes L.G.N. Chagasic cardiomyopathy is independently associated with ischemic stroke in Chagas disease. Stroke. 2005;36:965–970. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000163104.92943.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Echeverría L.E., Sánchez R., Mantilla A.F., et al. Riesgo de eventos embólicos en pacientes con miocardiopatía chagásica y fibrilación auricular a pesar de terapia antitrombótica: ¿es la anticoagulación suficiente? Rev Argent Cardiol. 2024;92:284–291. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lima-Costa M.F., Matos D.L., Ribeiro A.L.P. Chagas disease predicts 10-year stroke mortality in community-dwelling elderly. Stroke. 2010;41:2477–2482. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.588061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kondo T., Abdul-Rahim A.H., Talebi A., et al. Predicting stroke in heart failure and reduced ejection fraction without atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J. 2022;43:4469–4479. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehac487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang M., Kondo T., Butt J.H., et al. Stroke in patients with heart failure and reduced or preserved ejection fraction. Eur Heart J. 2023;44:2998–3013. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehad338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Simões M.V., Oliveira LF de, Hiss F.C., et al. Characterization of the apical aneurysm of chronic chagas' heart disease by scintigraphic image co-registration. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2007;89:131–134. doi: 10.1590/s0066-782x2007001400010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Oliveira J.S., Mello De Oliveira J.A., Frederigue U., Lima Filho E.C. Apical aneurysm of Chagas's heart disease. Br Heart J. 1981;46:432–437. doi: 10.1136/hrt.46.4.432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Beuther J., Silva Rigaud de Amorim F., Reyes Barrenechea M.W., Kaiser Ururahy Nunes Fonseca E. Apical aneurysm in chagas heart disease. Radiol Cardiothorac Imaging. 2021;3 doi: 10.1148/ryct.2021210135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Burger D., Montezano A.C., Nishigaki N., He Y., Carter A., Touyz R.M. Endothelial microparticle formation by angiotensin II is mediated via Ang II receptor type I/NADPH oxidase/Rho kinase pathways targeted to lipid rafts. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:1898–1907. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.222703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cordazzo C., Neri T., Petrini S., et al. Angiotensin II induces the generation of procoagulant microparticles by human mononuclear cells via an angiotensin type 2 receptor-mediated pathway. Thromb Res. 2013;131:e168–e174. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2013.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Remková A., Remko M. The role of renin-angiotensin system in prothrombotic state in essential hypertension. Physiol Res. 2010;59:13–23. doi: 10.33549/physiolres.931525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhou Q., Zhang Y., Shi W., et al. Angiotensin II induces vascular endothelial dysfunction by promoting lipid peroxidation-mediated ferroptosis via CD36. Biomolecules. 2024;14:1456. doi: 10.3390/biom14111456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gomolak J.R., Didion S.P. Angiotensin II-induced endothelial dysfunction is temporally linked with increases in interleukin-6 and vascular macrophage accumulation. Front Physiol. 2014;5:396. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2014.00396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Numazaki H., Nasu T., Satoh M., et al. Association between vascular endothelial dysfunction and stroke incidence in the general Japanese population: results from the tohoku medical megabank community-based cohort study. Int J Cardiol Cardiovasc Risk Prev. 2023;19 doi: 10.1016/j.ijcrp.2023.200216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Martinez-Majander N., Gordin D., Joutsi-Korhonen L., et al. Endothelial dysfunction is associated with early-onset cryptogenic ischemic stroke in men and with increasing age. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.121.020838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kleeberg A., Luft T., Golkowski D., Purrucker J.C. Endothelial dysfunction in acute ischemic stroke: a review. J Neurol. 2025;272:143. doi: 10.1007/s00415-025-12888-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gómez-Ochoa S.A., Rojas L.Z., Hernández-Vargas J.A., et al. Myocardial fibrosis by magnetic resonance and outcomes in chagas disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2023 doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2023.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Colangelo T., Peters P., Sadler M., Safi L.M. Membranous ventricular septal aneurysm leading to embolic stroke. CASE (Phila) 2022;6:142–145. doi: 10.1016/j.case.2022.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Doehner W., Böhm M., Boriani G., et al. Interaction of heart failure and stroke: a clinical consensus statement of the ESC council on stroke, the heart failure association (HFA) and the ESC Working Group on thrombosis. Eur J Heart Fail. 2023;25:2107–2129. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.3071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Prado C.M., Jelicks L.A., Weiss L.M., Factor S.M., Tanowitz H.B., Rossi M.A. The vasculature in chagas disease. Adv Parasitol. 2011;76:83–99. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385895-5.00004-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sambiase N.V., Higuchi M.L., Benvenuti L.A. Narrowed lumen of the right coronary artery in chronic Chagasic patients is associated with ischemic lesions of segmental thinnings of ventricles. Invest Clin. 2010;51:531–539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Torres F.W., Acquatella H., Condado J.A., Dinsmore R., Palacios I.F. Coronary vascular reactivity is abnormal in patients with Chagas' heart disease. Am Heart J. 1995;129:995–1001. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(95)90122-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Garg P., van der Geest R.J., Swoboda P.P., et al. Left ventricular thrombus formation in myocardial infarction is associated with altered left ventricular blood flow energetics. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;20:108–117. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jey121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Levine G.N., McEvoy J.W., Fang J.C., et al. Management of patients at risk for and with left ventricular thrombus: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2022;146:e205–e223. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hochman J.S., Platia E.B., Bulkley B.H. Endocardial abnormalities in left ventricular aneurysms. A clinicopathologic study. Ann Intern Med. 1984;100:29–35. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-100-1-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Weinsaft J.W., Kim J., Medicherla C.B., et al. Echocardiographic algorithm for post-myocardial infarction LV thrombus: a gatekeeper for thrombus evaluation by delayed enhancement CMR. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;9:505–515. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2015.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Merkler A.E., Alakbarli J., Gialdini G., et al. Short-term risk of ischemic stroke after detection of left ventricular thrombus on cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2019;28:1027–1031. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2018.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nunes M. do CP., Barbosa M.M., Rocha M.O.C. Peculiar aspects of cardiogenic embolism in patients with Chagas' cardiomyopathy: a transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiographic study. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2005;18:761–767. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2005.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Oh J.K., Park J.-H., Lee J.-H., Kim J., Seong I.-W. Shape and mobility of a left ventricular thrombus are predictors of thrombus resolution. Korean Circ J. 2019;49:829–837. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2018.0346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Camaj A., Fuster V., Giustino G., et al. Left ventricular thrombus following acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79:1010–1022. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2022.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Leow A.S.-T., Sia C.-H., Tan B.Y.-Q., et al. Characterisation of acute ischemic stroke in patients with left ventricular thrombi after myocardial infarction. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2019;48:158–166. doi: 10.1007/s11239-019-01829-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Weinsaft J.W., Kim R.J., Ross M., et al. Contrast-enhanced anatomic imaging as compared to contrast-enhanced tissue characterization for detection of left ventricular thrombus. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2009;2:969–979. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2009.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Weinsaft J.W., Kim H.W., Shah D.J., et al. Detection of left ventricular thrombus by delayed-enhancement cardiovascular magnetic resonance prevalence and markers in patients with systolic dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:148–157. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bulluck H., Chan M.H.H., Paradies V., et al. Incidence and predictors of left ventricular thrombus by cardiovascular magnetic resonance in acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction treated by primary percutaneous coronary intervention: a meta-analysis. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2018;20:72. doi: 10.1186/s12968-018-0494-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Velangi P.S., Choo C., Chen K.-H.A., et al. Long-term embolic outcomes after detection of left ventricular thrombus by late gadolinium enhancement cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging: a matched cohort study. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;12 doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.119.009723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Choudhuri S., Garg N.J. Platelets, macrophages, and thromboinflammation in chagas disease. J Inflamm Res. 2022;15:5689–5706. doi: 10.2147/JIR.S380896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Barata Kasal D.A., Britto A., Verri V., De Lorenzo A., Tibirica E. Systemic microvascular endothelial dysfunction is associated with left ventricular ejection fraction reduction in chronic Chagas disease patients. Microcirculation. 2021;28 doi: 10.1111/micc.12664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ashton A.W., Mukherjee S., Nagajyothi F.N.U., et al. Thromboxane A2 is a key regulator of pathogenesis during Trypanosoma cruzi infection. J Exp Med. 2007;204:929–940. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.García-Álvarez A., Sitges M., Heras M., et al. [Endothelial function and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein levels in patients with Chagas disease living in a nonendemic area] Rev Esp Cardiol. 2011;64:891–896. doi: 10.1016/j.recesp.2011.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cyr A.R., Huckaby L.V., Shiva S.S., Zuckerbraun B.S. Nitric oxide and endothelial dysfunction. Crit Care Clin. 2020;36:307–321. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2019.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Pengue C., Cesar G., Alvarez M.G., et al. Impaired frequencies and function of platelets and tissue remodeling in chronic Chagas disease. PLoS One. 2019;14 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0218260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gazos-Lopes F., Oliveira M.M., Hoelz L.V.B., et al. Structural and functional analysis of a platelet-activating lysophosphatidylcholine of trypanosoma cruzi. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tanowitz H.B., Burns E.R., Sinha A.K., et al. Enhanced platelet adherence and aggregation in Chagas' disease: a potential pathogenic mechanism for cardiomyopathy. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1990;43:274–281. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1990.43.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hawwari I., Rossnagel L., Rosero N., et al. Platelet transcription factors license the pro-inflammatory cytokine response of human monocytes. EMBO Mol Med. 2024;16:1901–1929. doi: 10.1038/s44321-024-00093-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Müller F., Mutch N.J., Schenk W.A., et al. Platelet polyphosphates are proinflammatory and procoagulant mediators in vivo. Cell. 2009;139:1143–1156. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Barbosa-Ferreira J.M., Mady C., Ianni B.M., et al. Dysregulation of autonomic nervous system in chagas' heart disease is associated with altered adipocytokines levels. PLoS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0131447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Cunha A.B., Cunha D.M., Pedrosa R.C., et al. Norepinephrine and heart rate variability: a marker of dysautonomia in chronic Chagas cardiopathy. Rev Port Cardiol. 2003;22:29–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Thiers C.A., Barbosa J.L., Pereira B. de B., et al. Autonomic dysfunction and anti-M2 and anti-β1 receptor antibodies in Chagas disease patients. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2012;99:732–739. doi: 10.1590/s0066-782x2012005000067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kaze A.D., Yuyun M.F., Fonarow G.C., Echouffo-Tcheugui J.B. Cardiac autonomic dysfunction and risk of incident stroke among adults with type 2 diabetes. Eur Stroke J. 2023;8:275–282. doi: 10.1177/23969873221127108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Dávila D.F., Donis J.H., Arata de Bellabarba G., et al. Cardiac autonomic control mechanisms in the pathogenesis of chagas' heart disease. Interdiscip Perspect Infect Dis. 2012;2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/980739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ribeiro A.L., Moraes R.S., Ribeiro J.P., et al. Parasympathetic dysautonomia precedes left ventricular systolic dysfunction in Chagas disease. Am Heart J. 2001;141:260–265. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2001.111406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Machado C.R., Camargos E.R., Guerra L.B., Moreira M.C. Cardiac autonomic denervation in congestive heart failure: comparison of Chagas' heart disease with other dilated cardiomyopathy. Hum Pathol. 2000;31:3–10. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(00)80191-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Agarwal S.K., Norby F.L., Whitsel E.A., et al. Cardiac autonomic dysfunction and incidence of atrial fibrillation in a large population-based cohort. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69:291–299. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.10.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Qin M., Zeng C., Liu X. The cardiac autonomic nervous system: a target for modulation of atrial fibrillation. Clin Cardiol. 2019;42:644–652. doi: 10.1002/clc.23190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Carod-Artal F.J. Trypanosomiasis, cardiomyopathy and the risk of ischemic stroke. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2010;8:717–728. doi: 10.1586/erc.10.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Useche Y., Pérez A.R., de Meis J., Bonomo A., Savino W. Central nervous system commitment in Chagas disease. Front Immunol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.975106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lannes-Vieira J., Vilar-Pereira G., Barrios L.C., Silva A.A. Anxiety, depression, and memory loss in Chagas disease: a puzzle far beyond neuroinflammation to be unpicked and solved. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2023;118 doi: 10.1590/0074-02760220287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Shelton W.J., Gonzalez J.M. Outcomes of patients in Chagas disease of the central nervous system: a systematic review. Parasitology. 2024;151:15–23. doi: 10.1017/S0031182023001117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Caradonna K., Pereiraperrin M. Preferential brain homing following intranasal administration of Trypanosoma cruzi. Infect Immun. 2009;77:1349–1356. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01434-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.de Melo-Jorge M., PereiraPerrin M. The Chagas' disease parasite Trypanosoma cruzi exploits nerve growth factor receptor TrkA to infect mammalian hosts. Cell Host Microbe. 2007;1:251–261. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Jardim E. [Experimental acute Chagas' disease: parasitism of the hypothalamus] Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 1971;29:190–197. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x1971000200007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Da Mata J.R., Camargos M.R., Chiari E., Machado C.R. Trypanosoma cruzi infection and the rat central nervous system: proliferation of parasites in astrocytes and the brain reaction to parasitism. Brain Res Bull. 2000;53:153–162. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(00)00326-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Vilar-Pereira G., Silva AA da, Pereira I.R., et al. Trypanosoma cruzi-induced depressive-like behavior is independent of meningoencephalitis but responsive to parasiticide and TNF-targeted therapeutic interventions. Brain Behav Immun. 2012;26:1136–1149. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2012.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Drake C., Boutin H., Jones M.S., et al. Brain inflammation is induced by co-morbidities and risk factors for stroke. Brain Behav Immun. 2011;25:1113–1122. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2011.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Deigner H.P., Haberkorn U., Kinscherf R. Apoptosis modulators in the therapy of neurodegenerative diseases. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2000;9:747–764. doi: 10.1517/13543784.9.4.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Baldissera M.D., Souza C.F., Carmo G.M., et al. Relation between acetylcholinesterase and Na+, K+-ATPase activities with impaired memory of mice experimentally infected by Trypanosoma cruzi. Microb Pathog. 2017;111:75–80. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2017.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Silva A.A., Roffe E., Marino A.P., et al. Chagas' disease encephalitis: intense CD8+ lymphocytic infiltrate is restricted to the acute phase, but is not related to the presence of Trypanosoma cruzi antigens. Clin Immunol. 1999;92:56–66. doi: 10.1006/clim.1999.4716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Roffê E., Silva A.A., Marino A.P.M.P., dos Santos P.V.A., Lannes-Vieira J. Essential role of VLA-4/VCAM-1 pathway in the establishment of CD8+ T-cell-mediated Trypanosoma cruzi-elicited meningoencephalitis. J Neuroimmunol. 2003;142:17–30. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(03)00254-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Koh C.C., Neves E.G.A., de Souza-Silva T.G., et al. Cytokine networks as targets for preventing and controlling chagas heart disease. Pathogens. 2023;12:171. doi: 10.3390/pathogens12020171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Silva R.R., Mariante R.M., Silva A.A., et al. Interferon-gamma promotes infection of astrocytes by Trypanosoma cruzi. PLoS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Silva A.A., Silva R.R., Gibaldi D., et al. Priming astrocytes with TNF enhances their susceptibility to Trypanosoma cruzi infection and creates a self-sustaining inflammatory milieu. J Neuroinflammation. 2017;14:182. doi: 10.1186/s12974-017-0952-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Barreto-de-Albuquerque J., Silva-dos-Santos D., Pérez A.R., et al. Trypanosoma cruzi infection through the oral route promotes a severe infection in mice: new disease form from an old infection? PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Wu F., Liu L., Zhou H. Endothelial cell activation in central nervous system inflammation. J Leukoc Biol. 2017;101:1119–1132. doi: 10.1189/jlb.3RU0816-352RR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Galea I. The blood–brain barrier in systemic infection and inflammation. Cell Mol Immunol. 2021;18:2489–2501. doi: 10.1038/s41423-021-00757-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Kelly P.J., Lemmens R., Tsivgoulis G. Inflammation and stroke risk: a new target for prevention. Stroke. 2021;52:2697–2706. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.121.034388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Furlan J.C., Vergouwen M.D.I., Fang J., Silver F.L. White blood cell count is an independent predictor of outcomes after acute ischaemic stroke. Eur J Neurol. 2014;21:215–222. doi: 10.1111/ene.12233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Mun K.T., Hinman J.D. Inflammation and the link to vascular brain health: timing is brain. Stroke. 2022;53:427–436. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.121.032613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Maldonado E., Rojas D.A., Urbina F., Solari A. The oxidative stress and chronic inflammatory process in chagas disease: role of exosomes and contributing genetic factors. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2021;2021 doi: 10.1155/2021/4993452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.de Carvalho F.C.T., de Oliveira L.R.C., Gatto M., et al. Oxidative stress evaluation in patients with chronic Chagas disease. Parasitol Int. 2023;96 doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2023.102770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Maldonado E., Rojas D.A., Morales S., Miralles V., Solari A. Dual and opposite roles of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in chagas disease: beneficial on the pathogen and harmful on the host. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2020;2020 doi: 10.1155/2020/8867701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Machado-Silva A., Cerqueira P.G., Grazielle-Silva V., et al. How Trypanosoma cruzi deals with oxidative stress: antioxidant defence and DNA repair pathways. Mutat Res Rev Mutat Res. 2016;767:8–22. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2015.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Abdul-Muneer P.M., Chandra N., Haorah J. Interactions of oxidative stress and neurovascular inflammation in the pathogenesis of traumatic brain injury. Mol Neurobiol. 2015;51:966–979. doi: 10.1007/s12035-014-8752-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]